Memorandum Opinion and Dissent

Public Court Documents

April 14, 1998

41 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Memorandum Opinion and Dissent, 1998. 469bba9e-e10e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e31a26f5-16fd-4b69-b979-cf46172bd5ee/memorandum-opinion-and-dissent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

15:21 7 99

FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION ® 85.27.1998

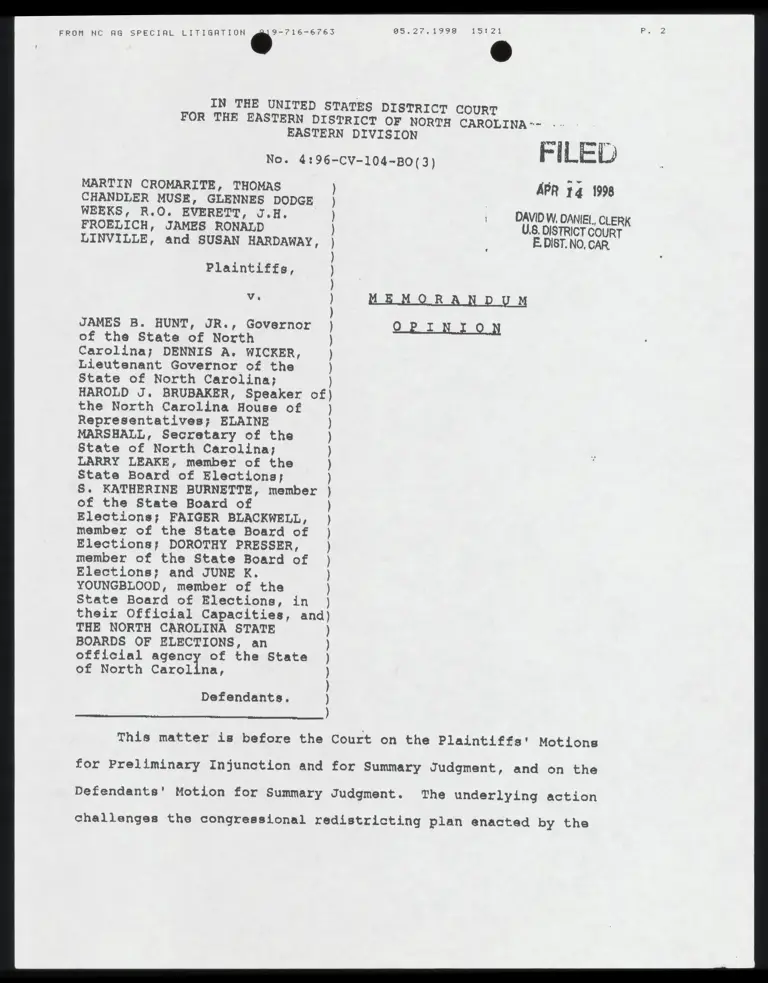

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA -- EASTERN DIVISION

No. 4:96-CV-104-BO(3) FILED

MARTIN CROMARITE, THOMAS

CHANDLER MUSE, GLENNES DODGE

WEEKS, R.O, EVERETT, J.H. |

FROELICH, JAMES RONALD

LINVILLE, and SUSAN HARDAWAY,

APR 14 1998

DAVID W. DANIEL, CLERK

U.8. DISTRICT COURT

E. DIST. NO, CAR

Plaintiffs,

Vo MEMORANDUM

QR I NI ON

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., Governor

of the State of North

Carolina; DENNIS A. WICKER,

Lieutenant Governor of the

State of North Carolina;

HAROLD J. BRUBAKER, Speaker of

the North Carolina House of

Representatives; ELAINE

MARSHALL, Secretary of the

State of North Carolina;

LARRY LEAKE, member of the

State Board of Elections;

8. KATHERINE BURNETTE, member

of the State Board of

Elections; FAIGER BLACKWELL,

member of the State Board of

Elections; DOROTHY PRESSER,

member of the State Board of

Elections; and JUNE K.

YOUNGBLOOD, member of the

State Board of Elections, in

their Official Capacities, and

THE NORTH CAROLINA STATE

BOARDS OF ELECTIONS, an

official agency of the State

of North Carolina,

Defendants,

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

S

u

a

r

S

t

e

r

e

n

e

e

t

i

r

S

r

v

n

at

t

S

i

e

e

t

S

c

S

r

n

m

ni

a

a

This matter is before the Court on the Plaintiffs' Motions

for Preliminary Injunction and for Summary Judgment, and on the

Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment. The underlying action

challenges the congressional redistricting plan enacted by the

98.27.1998" 115821 FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION “

General Assembly of the State of North Carolina on March-31,

1997, contending that it violates the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment, and relying on the line of cases

represented by Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. B99, 116 §. Ct. 1894, 135

L.Ed.2d 207 (1996) ("Shaw II"), and Miller v, Johnson, 515 U.s.

900, 904, 115 8. Ct. 2475, 2482, 132 L.Ed.2d 762 (1995),

Following a hearing in this matter on March 31, 1998, the

Court took the parties’ motions under advisement and thereafter

issued an Order and Permanent Injunction (1) finding that the

Twelfth Congressional District under the 1997 North Carolina

Congressional Redistricting Plan is unconstitutional, and

granting Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment as to the

Twelfth Congressional District; (2) granting Plaintiffs' Motion

for Preliminary Injunction and granting Plaintiffs’ request, as

contained in its Complaint, for a Permanent Injunction, thereby

‘enjoining Defendants from conducting any primary or general

election for congreesional offices under ths redistricting plan

enacted as 1997 N.C. Session Laws, Chapter 11) and (3) ordering

that the parties file a written submission addressing an

appropriate time period within which the North Carolina General

Assembly may be allowed the opportunity to correct the

constitutional defects in the 1997 Congressional Redistricting

Plan, and to present a proposed election schedule to follow

redistricting which provides for a primary election process

culminating in a general congressional election to be held on

Tuesday, November 3, 1998, the date of the previously scheduled

85.27.1998 15122 FROM NC RAG SPECIAL LITIGATION @

general election.

That Order was issued on April 3, 1998, by a majority of the

three-judge panel. Circuit Judge Sam J. Ervin, III, dissented.

Defendants filed a Motion for a Stay of the April 3 Order, which

was denied by this Court by Order dated April 6, 1998.

Defendants also appealed the April 3 Order to the Supreme Court,

and the appeal is still pending in that Court. This Memorandum

and Opinion refers to that Order, and shall be the opinion of the

Court.

BACKGROUND

In Shaw JI the United States Supreme Court held that the

Twelfth Congreseional District created by the 1992 Congressional

Redistricting Plan (hereinafter, the "1992 plan") had been race-

based and could not survive the required "strict scrutiny." 517

U.s. 899, 116 S. Ct. 1894. The five plaintiffs in Shaw lacked

standing to attack the other majority-minority district (the

First Congressional District under the 1992 plan) because they

were not registered voters in the district.- id.

Soon after the Supreme Court ruled in Shaw II, three

residents of Tarboro, North Carolina, filed the original

Complaint in this action on July 3, 1996. These original

Plaintiffs resided in the First Congressional District

(alternatively, "District 1") as it existed under North

Carolina's 1992 plan. The Plaintiffs charged that the First

Congressional District violated their rights to equal protection

under the United States Constitution because race predominated in

919-716-6763 85.27.1998 15:22 FROM NC RG SPECIAL LITIGRTION

the drawing of the District. The action was stayed pending

resolution of remand proceedings in Shaw v, Hunt, and on July 9,

1996, the same three Tarboro residents joined the Plaintiffs in

Shaw in filing an Amended Complaint in that case, similarly

challenging District 1.

By Order dated September 12, 1997, the three-judge panel in

Shaw approved a congressional redistricting plan enacted on March

31, 1997, by the General Assembly as a remedy for the

constitutional violation found by the Supreme Court to exist in

the Twelfth Congressional District (alternatively, "District

12"). The Shaw three-judge panel also dismissed without

prejudice, as moot, the plaintiffs' claim that the First

Congressional District in the 1992 plan was unconstitutional.

Although it was a final order, the September 12, 1997, decision

of the Shaw three-judge panel was not preclusive of the instant

cause of action, as the panel was not presented with a continuing

challenge to the redistricting plan.’

' In its final Memorandum Opinion, the three-judge panel in Shaw, noted that there was "no substantive challenge to the (1997) plan by any party to this action," and closed by explicitly "noting the limited basis of the approval of the plan that we are empowered to give in the context of thie litigation. It is limited by the dimensions of this civil action as that is defined by the parties and the claims properly before us. Here, that means that we only approve the plan as an adequate remedy for the specific violation of the individual equal protection rights of those plaintiffs who successfully challenged the legislature's creation of former District 12. Our approval thus does not—cannot~run beyond the plan's remedial adequacy with respect to those parties and the equal protection violation found as to former District 12." shaw v, Hunt, No. 92-202-CIV-5-BR, at 8 (E.D.N.C. Sept. 12, 1997).

85.27.1998 15:22 FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION 9

On October 17, 1997, this Gone dissolved the stay

previously entered in this matter. On the same day, two of the

original three Plaintiffs, along with four residents of District

12, filed an amended Complaint challenging the 1997 remedial

congressional redistricting plan (the "1997 plan"), and seeking a

declaration that the First and Twelfth Congressional Districts in

the 1997 plan are unconstitutional racial gerrymanders. The

three-judge panel was designated by order of Chief Judge

Wilkinsion of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, dated January

23, 1998. The Plaintiffs moved for a preliminary injunction on

January 30, 1998, and for summary judgment on February 5, 1998.

The Defendants filed their instant summary judgment motion on

March 2, 1998, and a hearing on these motions wag held on March

31, 1998.

FACTS

The North Carolina General Assembly convened in regular

session on January 29, 1997, and formed redistricting committees

to address the defects found in the 1992 plan. These newly

formed House and Senate Committees aimed to identify a plan which

would cure the constitutional defects and receive the support of

a majority of the members of the General Assembly. Affidavit of

Senator Roy A. Cooper, III ("Cooper Aff.") %3. In forming a

workable plan, the committees were guided by two avowed goals:

(1) curing the constitutional defects of the 1992 plan by

assuring that race was not the predominant factor in the new

plan, and (2) drawing the plan to maintain the existing partisan

5

XY 9-716-6763 AS5.27.1998 1523 FROM NC RAG SPECIAL Te

balance in the State's congressional delegation. Cooper Aff,

593, 8, 10, 14; Affidavit of Gary 0, Bartlett, Executivs

Secretary-Director of the State Board of Elections ("Bartlett

Aff."), Vol, I Commentary at 9-10.

To achieve the second goal, the redistricting committees

drew the new plan (1) to avoid placing two incumbents in the same

district and (2) to preserve the partisan core of the existing

districts to the extent consistent with the goal of curing the

defects in the old plan. Cooper Aff, 14. The plan as enacted

reflects these directives: no two incumbent Congressmen reside

in the same district, and each district retains at least 60% of

the population of the old district. Cooper aff. 18, Affidavit of

Representative W. Edwin McMahan ("McMahan Aff.") q7.

i. The Twelfth congresgional District

District 12 is one of the six predominantly Democratic

districts established by the 1997 plan to maintain the 6-6

partisan division in North Carolina's congressional delegation.

District 12 is not a majority-minority district,? but 46.67

percent of its total population is African-American. Bartlett

Aff,, Vol. I Commentary at 10 and 11. District 12 is composed of

six counties, all of them split in the 1997 plan. The racial

composition of the parts of the six sub-divided counties assigned

? The Twelfth is not a majority-minority district as measured by any of three possible criteria. African-Americans constitute 47 percent of the total population of District 12, 43

at 8.

American, and three in which the African-American Percentage ig under 50 percent. Declaration of Ronald E. Webber ("Webber

Dec,") 918. However, almost 75 percent of the total Population

in District 12 comes from the three county parts which are

majority African-American in population: Mecklenburg, Forsyth,

and Guilford counties. 14. The other three county parts

(Davidson, Iredell, and Rowan) have narrow corridors which pick

up as many African-Americans a8 are needed for the district to

reach its ideal size.! 1d,

Where Forsyth County was split, 72.9 percent of the total

population of Forsyth County allocated to District 12 is African~

American, while only 11.1 percent of its total population :

assigned to neighboring District 5 is African-American. Id. 720.

Similarly, Mecklenburg County is split so 51.9 percent of its

total population allocated to District 12 is African-American,

while only 7.2 percent of the total population assigned to

adjoining District 9 is African-American.

A similar pattern emerges when analyzing the cities and

towns split between District 12 and its surrounding districts:

the four largest cities assigned to District 12 are split along

racial lines. 11d. 23. For example, where the City of Charlotte

is split between District 12 and adjacent District 8, 59.47

' An equitably populated congressional district in North Carolina needs a total population of about 552,386 persons using 1990 Census data. Weber Dec. 139.

7

945.,27.1998 15:23 . ip -6763 FROM NC RAG SPECIAL LITIGRTION 19=-7156-6

percent of the population assigned to District 12 ig African- American, while only 8.12 percent of the Charlotte population agsigned to District 9 is African-American. Affidavit of Martin B. McGee ("McGee Aff."), Bx. 1. And where the City of Greensboro is split, 55.58 percent of the population assigned to District 12 is African-American, while only 10.70 percent of the population

assigned to District § is African-American. Id.

An analysis of the voting precincts immediately surrounding

District 12 reveals that the legislature did not simply create a

majority Democratic district amidst surrounding Republican

precincts. For example, around the Southwest edge of District 12

(in Mecklenburg County), the legislature included within the

district's borders several precincts with racial compositions of

40 to 100 percent African-American; while excluding from the |

district voting precincts with less than 35 percent African-

American population, but heavily Democratic voting registrations.

Among Mecklenburg County precincts which are immediately adjacent

to District 12, but not inside it, are precincts with 58.818

percent of voters registered as Democrats, and precincts that are

56.464 percent Democratic, 54.213 percent Democratic, 59.135

percent Democratic, 59.225 percent Democratic, 54.498 percent

Democratic, 59.098 percent Democratic, 55.72 percent Democratic,

54.595 percent Democratic, 54.271 percent Democratic, 63.452

percent Democratic, and 59,453 percent Democratic, 1Id., Ex. Dp.

Similarly, Forsyth County precincts that are immediately adjacent

to, but not inside, District 12 include precincts with 57.371

8

85.27.1998 15+23 FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION “emis

Percent Democratic registration, 65.253 Percent Democratic

registration, 65.74% percent Democratic registration, 65.747

percent Democratic regietration, 76 percent Democratic

registration, 55.057 percent Democratic registration, 55.907

~ percent Democratic registration, 56.782 percent Democratic

registration, 55.836 percent Democratic registration, and 60.113

percent Democratic registration. vIld., Ex. 0, Finally, District

12 was drawn to exclude precincts with 59.679 percent Democratic

registration, 61.86 percent Democratic registration, 58.145

percent Democratic registration, 62,324 percent Democratic

registration, 60.209 percent Democratic registration, 56.739

percent Democratic registration, 66.22 percent Democratic

registration, 57.273 percent Democratic registration, 55.172

percent Democratic registration, and 63.287 percent Democratic

registration, all in Guilford County. 1I1d., Ex. N.

On the North Carolina map, District 12 has an irregular

shape and is barely contiguous in parts. Its Southwest corner

lies in Mecklenburg County, very close to the South Carolina

border, and includes parts of Charlotte. The District moves

North through Rowan County and into Iredell County. There it

juts West to pick Up parts of the City of Statesvilla, More than

75 percent of the Statesville population that is included in

District 12 is African-American, while only 18.88 percent of the

population of Statesville excluded from District 12 is African-

American. McGee Aff., Ex. L. From Statesville, the District

moves East into Rowan County. There it dips to the South to

85.27.1998 15:24 -716-6763 FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION ® 716-67

include Salisbury, before turning to the Northeast and entering

Davidson County and the City of Thomasville. Over 41 percent of

the populations of Salisbury and Thomasville that are included in

District 12 are African-American, while only 15.39 and 9.55

percent, respectively, of those that are excluded from the

District are African American. Id, The District makes a

northwesterly incursion into Forsyth County to include parts of

Winston-Salem, where 77.39 percent of the population within

District 12 is African-American, and only 16.06 percent of the

population left out is African-American. Id. The District moves

to the East and narrows dramatically before opening up again to

include the predominantly African-American parts of Greensboro,

where the District ends.

Objective, numerical studies of the compactness of

congressional districts are also available. Ih his report, "An

Evaluation of North Carolina's 1998 Congressional Districts,"

Professor Gerald R. Webster, one of the Defendants’ expert

witnesses, presents statistical analyses of "comparator

compactness indicators" for North Carolina's congressional

districts under the 1997 Plan. In measuring the districts’

10

wr 5)

compactness indicators, Webster, at 13 (citing Pildes & Niemi, Expressive Harms, "Bizarre Districts," and Voting Rights:

Evaluating Election~District Appearances After Shaw V. Reno, 92 Mich,L.Rev. 483, 571-573, table § (1993) (hereinafter, "Pildes & Niemi"); and see Bush v, vera, 517 U.S. 952, —, 116 §. ct. 1941, 1952, 135 L.Bd.2d 248 (1996) (citing Pildes § Niemi compactness factors as supporting evidence for holding three Texas

congressional districts unconstitutional).

In discussing the relative normalcy of various compactness

measures, Pildes and Niemi suggest that a "low" dispersion

compactness measure would be equal to or less than 0.15. Pildes

& Niemi, at 564, They suggest that a "low" perimeter compactness

measure is equal to or less than 0.05. Id. North Carolina's

Twelfth Congressional District under the 1997 plan has a

dispersion compactness indicator of 0.109 and a perimeter

compactness indicator of 0.041. Webster, at table 3. These

‘ "pispersion compactness” measures the geographic "dispersion of a district. To calculate this a circle is circumscribed around a district, The reported coefficient is the proportion of the area of the circumscribed circle which is also included in the district, This measure ranges from 1.0 (most compact) to 0.0 (least compact). Webster, at 14.

’ "Perimeter compactness" is based upon the calculation of the district's perimeter. The reported coefficient is the proportion of the area in the district relative to a circle with the same perimeter. This measure ranges from 1.0 (most compact) to 0.0 (least compact). Webster, at i4. The equation used here is (((4 x II) x Area of district) + (District's Perimeter2)). Webster, at table 3.

11

«12

is 0.354, and the average perimeter compactness indicator is

0.192. Id, The next lowest dispersion compactness indicator

after District 12 is the 0.206 in the Fifth Congressional

District, and the next lowest perimeter compactness indicator is

the First Congressional District's 0.107. 14.

Zl. The fF Co 8 1 Eric

District 1 is another predominantly Democratic district

‘established by the 1997 plan. Unlike Dlstriot 12, {it ig. m

majority-minority district, based on percentages of the total

population of the District,’ as 50.27 percent of its total ;

population is African-American. Id., Vol. I Commentary at 10.

District 1 is composed of ten of the 22 counties split in drawing

the statewide 12 district 1997 plan. Weber Dac. M16. Half of

the twenty counties represented in District 1 are split. Id. of

the ten sub-divided counties assigned to District 1, four have

parts with over 50 percent African-American population, four

others have parts with over 40 percent African-American

population, and two others have parts with over 30 percent

African-American population. i1d., 917.

In each of the ten counties that are split between District

° While 50,27 percent of the total population of District 1 is African-American, only 46.54 percent of the voting age population is African-American, based on the 1990 census data. Bartlett Aff., Vol. I Commentary at 10.

12

85.27.1998 15:25 FROM HC AG SPECIAL pe

1 and an adjacent district, the percent of the population that ig African-American is higher inside the district than it is outgide the district, but within the same county. 1Id., 919 and Table 2. The disparities are less significant than in the county splits

involving District 12. Id., Table 2. For example, where

Beaufort County is 8plit between Districts land 3, 37.7 percent

of the total population of Beaufort County allocated to District

l is African-American, while 22.9 percent of the total population

of Beaufort County assigned to District 3 ig African~American,

Similarly, nine of the 13 cities and towns split between

District 1 and its neighboring districts are split along racial

lines. 1d., %22. For example, where the City of New Bern is

split between District 1 and adjacent District 3, 48.27 percent

of the population assigned to District 1 ig African-American,

while 24.49 percent of the New Bern population assigned to

District 3 is African-American. McGee Aff., Ex. 1,

Viewed on the North Carolina map, District 1 is not as

irregular as District 12. In the North, it spans 151.2 miles

across, from Roxboro, Person County, in the West, to Sunbury,

Gates County, in the East. Affidavit of Dr. Alfred w. Stuart

("Stuart Aff."), table 1. 1t ig shaped roughly like the state of

Florida, although the protrusion to the South from its

"panhandle" is only approximately 150 miles long (to Goldsboro,

Wayne County, with two irregularities jutting into Jones, Craven,

and Beaufort Counties. Cooper Aff., attachment. These

irregularities surround the Peninsular extension of the Third

13

«14

85.27.1998 15:25 FROM NLC AG SPECIAL ne.

Congressional District from the Zest, allowing the incumbent from

the previous Third Congressional District to retain his residence

within the boundaries of the same district, and avoiding placing

two incumbents in District i

The "comparator compactness indicators" from District 1 are

much closer to the North Carolina mean compactness indicators

than are those from District 12. ror example, District 1 has a

dispersion compactness indicator of 0,317 and a perimeter

compactness indicator of 0.107, Webster, at table 3, This

dispersion compactness indicator is not eignificantly lower than

the State's mean indicator of 0.354, and is higher than the

dispersion compactness indicators of Districts 12 (0.109), 9

(0.292), and 5 (0.206). 1d. It may be noted that Districts 5

and 9 are next to, and necessarily shaped by, District 12.

District 1 has a perimeter compactness indicator of 0.107, which

is lower than North Carolina‘'e mean perimeter compactness

indicator (0.192), but much higher than Pildes and Niemi's

suggested "low" perimeter compactness indicator (0.05). District

1's perimeter compactness indicator is also much higher than that

of District 12 (0.041). 1d.

S SION

The Equal Protection Clause of the United States

Constitution provides that no State "shall deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." U.s,.

Const. amend. 14, § 1. The United States Supreme Court explained

in Miller v Johnson, 515 U.8., at 904, 115 s, Ct., at 2482, that

14

«15

85.27.1998 15:25 FROM HC AG. SPECIAL Ghipaie une

the central mandate of the Equal PEdtection Clause "is racial

heutrality in governmental decisionmaking. * Application of this

mandate clearly prohibits purposeful discrimination between

individuals on the basis of race, Shaw. v, Reng, 509 u.s. 630,

642, 113 s. ct. 281s, 2824, 125 n.Bd.2d 51] (1993) ("Shaw I")

(citing Was shingtop v, Davis, 426 U.s. 229, 239, 96 8. Ct. 2040,

2047, 48 L.Ed.2d 597 (1976)).

As the Supreme Court recognized, however, the use of this

principle in "electoral districting is a most delicate task."

Miller, 515 U.S., at 805, 115 =. Ct., at 2483, Analysis of

suspect districts must begin from the premise that "[l]aws that

explicitly distinguish between individuals on racial grounds fall

within the core of (the Equal Protection Clause 8] prohibitien,

Shaw I, 509 U.s., at 642, 113 8. Ct., at 2824. Beyond that,

however, the Fourteenth Amendment's prohibition "extends not just

to explicit racial classifications," Miller, 515 U.S., at 905,

115. 8, Ct., at 2483, but also to laws, neutral on their face, but

"unexplainable on grounds other than race," Arlington Heights v,

0 a [o) eva lopme + 429 U.S. 252, 286, 81 8,

Ct. 555, 564, 50 L.Ed.2d 450 (1977).

In challenging the constitutionality of a State's

districting plan, the "plaintiff bears the burden of proving the

race-based motive and may do so either through 'ecircumstantial

evidence of a district's shape and demographics' or through 'more

direct evidence going to legislative purpose. '" Shaw II, 517

U.S., at —, 116 S. Ct., at 1900 (quoting Miller, 515 v.s., at

15

85.27.1998 15:26 FROM NC AG SPECIAL nL “ay

916,. 115 8, Ch., at 2488). In the final analysis, the plaintiff

must show "that race was the predominant factor motivating the

legislature's decision to place a significant number of voters

within or without a particular district." Id. (quoting Miller,

515 U.S., at 916, 115 8, ct., at 2483).

Once a plaintiff demonstrates that race was the predominant

factor in redistricting, the applicable standard of rsview of the

new plan is "strict scrutiny." Thus, in Miller the Supreme Court

held that strict scrutiny applies when race is the "predominant"

consideration in drawing the district lines such that "the

legislature subordinate(s] race~neutral districting principles

« «+ « to racial considerations." 515 Uu.s., at 916, 115 s. ct.,

at 2488, Under this standard of review, a State may escape .

censure while drawing racial distinctions only if it is pursuing

a "compelling state interest." Shaw IX, 517 U.8., at -, 116. 8.

Ct., at 1902.

However, "the means chosen to accomplish the State's

asserted purpose must be specifically and narrowly framed to

accomplish that purpose.” Wygant v. Jackson Bd. of Ed., 476 u.s.

267, 280, 106 S. Ct. 1842, 1850, 90 L.Ed.2d 260 (1986) (opinion

of Powell, J.). As the Supreme Court required in Shaw II, where

a State's plan has been found to be a racial gerrymander, that

State must now "show not only that its redistricting plan was in

pursuit of a compelling state interest, but also that its

districting legislation is narrowly tailored to achieve that

compelling interest." §17 U.S., at —, 116 S. Ct., at 1902.

16

17

a5.27.19%8 15:28 FROM NHC RAG SPECIAL ple.

We are cognizant of the principle that "redistricting and

reapportioning legislative bodies is a legislative task which the

federal courte should make every effort not to preempt." Wige v,

Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535, 539, 98 S. Ct. 2493, 2497, 57 L.Ed.2d 411

(1978) (citations omitted). "A State should be given the

opportunity to make its own redistricting decisions so long as

that is practically possible and the State chooses to take the

opportunity. When it does take the opportunity, the discretion

of the federal court is limited except to the extent that the

plan itself runs afoul of federal law." a . :

Justice, — U.S. —, —, 117 §. Ct. 2186, 2193, 138 L.Ed.2d €69

(1997) (internal citations omitted). Thus, when the federal

courts declare an apportionment scheme unconstitutional-as the

Supreme Court did in ghay 11-it is appropriate, "whenever :

practicable, to afford a reasonable opportunity for the

legislature to meet constitutional requirements by adopting a

substitute measure rather than for the federal court to devise

and order into effect its own plan. The new legislative plan, if

forthcoming, will then be the governing law unless it, too, is

challenged and found to violate the Constitution." RE 437

U.S., at 540, 98 8. Ct., at 2497.

i. Ihe Twelfth Congressional District

As noted above, the final decision of the three-judge panel

in Shaw only approved the 1997 Congressional Redistricting Plan

"as an adequate remedy for the specific violation of the

individual equal protection rights of those plaintiffs who

17

«18

FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION Q 85.27.1998 15:26

successfully challenged the legislature's creation of former

District 12." Shaw v. Hupt, No. 92-202~CIV-5-BR, at 8 (E.D.N.C.

Sept. 12, 1997). In the instant case, we are faced with a ripe

controversy as to the newly-configured Twelfth Congressicnal

District. This panel must thus decide whether, as a matter of

law, District 12 violates the equal protection rights of the

Plaintiffs who live within the district and challenge its

constitutionality.

In holding that District 12 under the 1992 plan was an

unconstitutional racial gerrymander, the Supreme Court in Shaw IX

noted, "[n]o one looking at District 12 could reasonably suggest

that the district contains a ‘geographically compact’ population

of any race." 517 U.S., at —, 116 S. Ct., at 1906. The Shaw II

Court thus struck the old District 12 as unconstitutional as a

matter of law. In redrawing North Carolina's congressional

districts in 1997 the General Assembly was, of course, aware that

District 12 under the 1992 plan had been declared

unconstitutional; curing the constitutional deficiencies was one

of the legislature's declared goals for the redistricting

process. Cooper Aff. 115, 8, 10, 14.

Defendants now argue that the changes in District 12 between

the 1992 and 1997 plans are dramatic enough to cure it of its

constitutional defects. They point to the fact that the new

District 12 has lost nearly one-third (31.6 parcent) of the

population from the 1992 district and nearly three-fifths (58.4

percent) of the land. These numbers do not advance the

18

7% 3 «19 15227 FROM NC RAG SPECIAL wali “te 85.27.1998

Defendants’ argument or end the Court's inquiry. As Defendants

themselves note, the Court's role is limited to determining

"whether the proffered remedial plan is legally unacceptable

because it violates anew constitutional or statutory voting

rights-that is, whether it fails to meet the same standards

applicable to an original challenge of a legislative plan in

place." McGhee v. Granville County, 860 F.2d 110, 115 (4* Cir.

1988) (citing Upham v. Seamon, 456 U.S. 37, 42, 102 8. ct. 1518,

1521, 71 L.Ed.2d 725 (1982)). A comparison of the 1992 Distriet

12 and the present District is of limited value here, The issue

in this case is whether District 12 in the present plan violates

the equal protection rights of the voters residing within it.

In Shaw I, the Supreme Court described old District 12 as

"unusually shaped. It is approximately 160 miles long and, for

much of its length, no wider than the [Interstate]~85 corridor.

It winds in snake-like fashion through tobacco country, financial

centers, and manufacturing areas until it gobbles in enough

enclaves of black neighborhoods." 509 U.S., at 635~636, 113 8.

Ct., at 2820-2821 (internal quotations omitted). Viewed without

reference to District 12 under the 1992 plan, the new District 12

is also "unusually shaped.” While its length has been shortened

to approximately 95 miles, it still winds ite way from Charlotte

to Greensboro along the Interstate-85 corridor, making detours to

pick up heavily African-American parts of cities such as

Statesville, Salisbury, and Winston-Salem. It algo connects

communities not joined in a congressional district, other than in

19

25.27.1998 15427 FROM NC RG SPECIAL jE aay

the unconstitutional 1992 plan, since the whole of Western North

Carolina was one district, nearly two hundred years ago. Pl.'s

Brief Opp. Def.'s Mot. s.3.. at 12.

As noted above, where cities and counties are split between

District 12 and neighboring districts, the splits are exclusively

along racial lines, and the parts of the divided cities and

counties having a higher proportion of African-Americans are

always included in District 12. Defendants argue that the

Twelfth has been designed with politics and partisanship, not

race, in mind. They describe the District as a "Democratic

island in a Republican sea," and present expert evidence that

political identification was the predominant factor determining

the border of District 12. Affidavit of David W. ("Peterson

Aff."), at 2. As the uncontroverted material facts demonstrate,

however, the legislators excluded many heavily-~Democratic

precincts from District 12, even though those precincts

immediately border the District. The commen thread woven

throughout the districting process is that the border of District

12 meanders to include nearly all of the precincts with African-

American population proportions of over forty percent which lie

between Charlotte and Greensboro, inclusive.

As noted above, objective measures of the compactness of

District 12 under the 1997 plan reveal that it is still the most

geographically scattered of North Carolina's congressional

districts. When compared to other previously challenged and

reconstituted congressional districts in North Carolina, Florida,

20

85.27.1998 15:27 FROM NLC. AG SPECIAL Hs

Georgia, Illinois, and Texas, District 12 does not fare well.

The District's dispersion and perimeter compactness indicators

(0.109 and 0.041, respectively) are lower than those values for

North Carolina's District 1 (0,317 and 0.107 under the 1997

plan). Similarly, the District suffers in comparison to

Florida's District 3 (0.136 and 0.05), Georgia's District 2

(0.541 and 0.411) and District 11 (0.444 and 0.259), Illinois’

District 4 (0.193 and 0.026), and Texas Digtrict 18 (0.335 and

0.151), District 29 (0.384 and 0.178), and District 30 (0.383 and

0.180).

Rule 56(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides

that summary judgment shall be granted if there is no genuine

issue as to any material fact and the moving party is entitled, to

judgment as a matter of law. The moving party must demonstrate

the lack of. a genuine issue of fact for trial, and if that burden

is met, the party opposing the motion must show evidence of a

genuine factual dispute. Ce v r- 417 U.8, 317,

324, 106 s. Ct. 2548, 2553, 91 L.Ed.2d 265 (1986).

Based on the uncontroverted material facts before it, the

Court concludes that the General Assembly, in redistricting, used

criteria with respect to District 12 that are facially race

driven. District 12 was drawn to collect precincts with high

racial ldentification rather than political identification.

Further, the uncontroverted material fasts demonstrata that

precincts with higher partisan representation (that is, more

heavily Democratic precincts) were bypassed in the drawing of

21

919-716-6763 85.27.1998 15422 FROM HC AG SPECIAL lal

District 12 and included in the surrounding congressional

districts. The legislature disregarded traditional districting

criteria such as contiguity, geographical integrity, community of

interest, and compactness in drawing District 12 in North

Carolina's 1997 plan. Instead, the General Assembly utilized

race as the predominant factor in drawing the District, thus

violating the rights to equal protection guaranteed in the

Constitution to the citizens of District 12.’

To remedy these constitutional deficiencies, the North

Carolina legislature must redraw the 1997 plan in such a way that

it avoids the deprivation of the voters' equal protection rights

not to be classified on the basis of race. This mandate of the

Court leaves the General Assembly free, within its authority, to

use other, proper factors in redrawing the 1997 plan. Among

these factors, the legislature may consider traditional

districting criteria, including incumbency considerations, to the

extent consistent with curing the constitutional defects. See

Shaw II, 517 U.S., at —, 116 §. Ct., at 1901 (describing "race-

neutral, traditional districting criteria").

II. FEixst Congressional District

Based on the record before us, the Plaintiff has failed to

establish that there are no contested material issues of fact

that would entitle Plaintiff to judgment as a matter of law as to

' The Supreme Court has indicated that, when drawing

congressional districts, race may not be used as a proxy for

political characteristics. Vera v. Bush, 517 U.S. 952, —, 116

8. Ct. 1941, 1956, 135 L.Ed.2d 248 (1996).

22

FROM HC NB SPECIAL LITIGATION 15:28 919-716-6765 85.27.1998

District 1. The Court thus denies Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary

Judgment as to that District. Conversely, neither has the

Defendant established the absence of any contested material issue

of fact with respect to the use of race as the predominant factor

in the districting of District 1 such as would entitle Defendant

to judgment as a matter of law.

CONCLUSION

Based on the Order of this Court entered on April 3, 1998,

and the foregoing analysis, Defendants will be allowed the

opportunity to correct the constitutional defects in the 1997

Congressional Redistricting Plan, in default of which the Court

would undertake the task.

This Memorandum Opinion, like the Order to which it refers,

is entered by a majority of the three-judge panel. Circuit Judge

Sam J. Ervin, IYI, dissents.

nd

This, the 14 ay of April, 1998.

TERRENCE W. BOYLE

Chief United States District Judge

RICHARD L. VOORHEES

United States District Judge

W/

BOYLE

CHIEF UNITED STATES DISTR

By:

JUDGE

23

FROM NC RG SPECIRL LITIGRTION

wu no Lv. ol D70¢ @ ou SAM J ERVIN IJ1 » 2002/0190 var

D}9-716-6763 85.27.1998 15:28

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

EASTERN DIVISION

No. 4:96-CV~-104~BO (3)

MARTIN CROMARTIE, THOMAS

CHANDLER MUSE, GLENNES DODGE

WEEKS, R.O. EVRRETT, J.H.

ROELICH, JAMES RONALD

LINVILLE, and SUSAN HARDAWAY,

Plaintiffs,

- Ye

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., Governor

of the State of North carolina;

et al.,

Defendants.

C

t

l

B

i

l

Ca

e

cl

C

e

l

Ca

l

N

e

l

o

n

N

t

V

t

:

C

a

”

F

n

“n

t”

N

g

“

a

“

i

?

~

~

“o

t”

ERVIN, Circuit Judge, dissenting:

In Shaw v. Reng, tha Supremes Court recognized a new cause of

action in voting rights law ~- that state legizslaturas could not

subordinate traditional districting principles to racial

considerations in drawing legislative districts without triggering

strict scrutiny under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. 50 U.S. 630 (1993) (" _I'Y. Becausa the districting

plan before us is fundamentally diffsrent from the plans struck

down by the Court in ghaw I and its progeny, gae Millar v. Johnson,

515 U.5. 900 (1995); shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899, 135 L, Ed, 2d 207

(1996) ("Shaw XX"), Bush _v, Vers, 517 U,S. 952, 135 L. Ed. 2d 248

(1996), I do not believe that the Plaintiffs have proven any

P. 25

FROM NC RAG SPECIRL LITIGATION Q19-716-6763 85.27.1998 15128 P.26

wertama 1e:m wrod doar SAM J ERVIN [i] wm 203/019

violation of their right toc the equal protection of the laws.

North cCarclina's twelfth congressional district is not a

majority=minority district, it was not created as a result of

gtrong-arming by the U.S. Departmant of Justice, and, contrary to

the majority's assertions, it is not so bizarre or unusual in shape

that it cannot be explained by factors othar than raca. The

Plaintiffs' evidence is not sc convincing as te undarmine the

State's contention that the 1997 Plan was motivated by a desire to

revady the constitutional violations from the 1992 Plan, to

sraserve the aven split betwasn Republicans and Democrats in the

North Carolina congressional delegation, and to protect incumbents

by drawing tha districts so that each incumbent resides in a

separate dAlptrict, Our accosptance of the Stata's proffared

justifications, absent more rigorous proof by tha Plaintiffs, ig

especially appropriate in this context, considering the deferance

that we are bound to accord state legislative decisions in

questions of redistricting. Finally, I find it i(nconsistent to

decide, ag the majority has dona today, that the General Assembly,

while engaging in a state-wide redistricting process, was

impermissibly influenced by predominantly racial considerations {(n

the drawing of one district (the twelfth) while evidencing no such

unconstitutional predilection in the other district under challenge

(the first), or for that matser, any of North Carelina's other ten

congressional districts. For these reascns, I must respectfully

dissant.

FROM NC RG SPECIAL LITIGRTION 919-716-6763 85.27.1998 154129 Pe27

0815/88 18:52 S704 ar SAM J ERVIN (11 a 2004/0180

I.

In order to prevail en a race-predominance claim, the

Plaintiffs must show "that race was the predominant factor

motivating the legislature's decision to placa a significant number

of voters within er without a particular district.” Miller, 518

U,8, at 916, The principle that race cannot be tha predominant

factor in a legislature's redistricting caloulus ie simple.

Applying that principle, on the other hand, is quita complex,

hacause numerous factors influence a legislatuyxe's districting

choices and no one factor may readily be {dentifisd as predominant,

In undertaking this analysis, it is crucial to note that in

the matter of redistricting, courts owe substantial deference to

tha legislature, which is fulfilling "the most vital of local

tunctiong” and is entrusted with the “discretion to axarcise the

political Judgment nacsssary to balance conpeting interests.’

Miller, 515 U.,S5. at 915, We presume the legislature acted in good

faith absent a sufficisnt showing to the contrary. Id. A state's

redistricting responsibility “should be accorded primacy to the

axtent possible when a federal court axserciees remedial power.’

Lawysr. Vv. Department of Juatica, 138 L. Ed. 24 669, 680 (1997).

While the majority and I appear to be in agreemant on these

general principled, the majority doss not discuss the extent of tha

Plaintiffs' burden in proving a claim of racial gerrymandaring.

concurring in Millar v, Johnson, Justice O'Connor emphasized that

the plaintiff's burden in cases of this kind must be especially

rigorous:

FROM NC RG SPECIAL LITIGATION &19-716-6763 A5.27.1998 15129 P.28

09/13/88 16:51 TP704 pe SAM J ERVIN [Il » 4008/0189

I understand the threshold standard the Court adopts . .

. tO be a demanding ona. To invoke strict scrutiny, a

plaintifr must show that the State has relied on raca in

aukstantial disregard of customary and traditional

Ajetricting practices. . . . [A)pplication of the Court's

standard helps achieve Shaw's basic objsctive of making

axtrama instances of gerrymandering subject to meaningrul

judicial review.

Millax, S515 U.8, at 928-29 (O'Connor, J., concurring) (emphasis

added). This principie was racently devaloped by a three=~judge

panel that upheld Ohio's 1992 redistricting plan for its state

legislature:

AB We apply the threshold analysis developed by the

Supreme Court in Shaw cases, we are mindful of the

dangers that a low threshold (easily invoking strict

scrutiny) poses for states. We therefore follow Justice

O'Connor's lead in applying a demanding threshold that

allows states soma dagrea of latitude to consider race in

drawing districts.

auilter wv. vVeinavich, 981 F. Supp. 1032, 1044 (N.D., Ohio 1597),

afe'd, 66 U.S.L.W. 3639 (U.S. Mar. 30, 1998) (No. 97-988). )

The Court has recognized that legislaturas often hava "mixed

motives” == they may intend to draw majority-minority districte as

well as to protact incumbents ox to accommodate other traditional

interests. Bugh.v, Vera, 135 L. Ed. 2d at 257, In such a cass,

courts must review extremely carsfully the avidance presented in

order to determina whather an impermissible raciel motive

predominated. A determination that a state has relied on race in

substantial disregard of customary and traditional districting

practiced will trigger strict scrutiny, though strict scrutiny does

net apply mneraly beacause redistricting is performed with

consciousness of race. 14. Plaintiffs wmay show that race

FROM NC RG SPECIAL LITIGATION 219-716-6763 85.27.1998 15:29 P.29

09/13/98 18:83 TFT04 @ SAM J BRYIN [11 a 4008/0189

predominated either through direct svidence of legislative intent

or through circumstantial evidence, such 23 the extremely contorted

nature of a district's shape and its racial demographics. Shaw. Ill,

135 L. EQ. 24 at 218-219; Miller, 515 U.S. at 91€.

The Plaintiffs have presented no direct evidence that the

Genaral Assembly's intent was to draw district lines based on race.

In contrast to the redistricting plana at issue in North Carolina

in Shaw II, in Texas in Buah Ww. Vara, and in Gesergia in Miller v,

Johnaon, the 1997 Plan was not drawn with an articulated desire to

maximize minority voting participation. In order to succeed on

summary judgment, the Plaintiffs must therefore present

circumetantial evidence that the state not only showed substantial

disregard for traditional districting prineiples, but that the

predominant factor in the legislatura's daciajon to act as it did

was races.

IX.

The State has asserted that several criteria were more

important than race in the Genaral Assembly's creation of the 1997

Redistricting Plan. The General Assembly drew tha 1957 Plan %o

remedy the constitutional violations in the 1992 Plan, to presarve

North Carolina's partisan balance of six Republicans and aix

Democrats, and to aveld placing two incumbants in the mame

district. Sas Refendants' Br, in Suppart. of Summary Judgment at 4

7 (“Refandants' Bx.”). In order to grant Plaintiffs the relief thay

seek, they must prove that the State has substantially disregarded

FROM NC RG SPECIAL LITIGATION 919-716-6763 285,27.1998 15:38 P.308

00-13-88 18:34 S704 ‘@ SAM J ERVIN [I] Bs 2007/018

these proffered redistricting criteria, as well as other

traditional districting critaria, in favor of race. I believe that

the Plaintiffs have failed to meet this burden.

First and foremost, the districts at issue here are not

majority-minority districts.’ I find {t of utmost importance that

only 43,36% of the voting-age population in District 12 is African-

American. This fact immediately distinguishes this case from the

line of Supreme Court cases that have struck down racial

gerrymandering in North Carolina, Fleride, Georgia, Louisiana, and

Taxas ~-- cases that define the equal protaction inquiry in this

area. The Court itself racognized this diatinction whan |{t

recently upheld a Flcrida state senate district that was not a

majority-minority digtriet, See lawyer, 138 L. Ed. 24 at 580

(upholding state gsenats district with 36.2% black voting-ags

population); see algo Quilter v, Voinoviah, 66 U.8.L.W. 3639 (V,S.

May. 30, ,1998) (No. 97-988) (affirming decision of three-judge

panel that rejected a racial gerrymandering challenge to Ohie

! The Supreme Court has not articulated whether a district ia

designated majority-minority by reference to voting=-age population,

by reference to ovarall population, or by reference tc voter

registration. Voting~age population would seem to be the

appropriate benchmark. All pecple of voting age have the capacity

to influence elections, whereas those under voting age obviously

cannot, Counting only registered voters would potentially

undercount those with the potential to influence elections.

In District 12, 43.36% of the voting=age population is black,

while 46.67% of the total population is black. In District 1,

46.87% of the voting=-age population is black, while 50.27% of the

total population is black. Under none of the possible criteria,

then, can District 12 be considered a majority-minority district.

District 1 can only be considered a majority~minority district with

refarance to total population. Jaa Defendants! Br, at 6.

6

FROM NC RG SPECIRL LITIGATION 919-716-6763 15.27.1998 15:30

09-13r98 1:00 FIV “@ AM UY LAYENY Las » EE

legislative districts that were hot majority-minority).

In its racial composition, District 12 is no different from

avery one of North Carolina's cther eleven congressional Aaistricte:

the majority of the veting-age population in the district ls white.

While thie may not be dispositive of the question wheather race was

the predominant factor in the legislature's redistricting plan, the

fact that all of North Carolina's congressional districts are

najority-white at the very Yoast nakes the Flaintiffs' burden,

which is already quite high, even more onerous. Had the

legielature been predominantly influenced by a desire to draw

Dietriet 12 according to race, I suspect Lt would have created a

Aigtrict where more than 43% of the veting-age population was

black, In part because District 12 is not a majority=-minerity

district, I find no reason to credit the Plaintilfs' contention

that race was the predominant factor in the Legisinturaly

decisions, This is especially true considering that the

legislature has proffered several compelling, noneracial factors

for ite decision.

second, this case is readily distinguishable from pravious

vacial gerrymandering casas bacauss tha plan at issue is not the

result of North Carolina's acquiescence to pressure from the U.S.

Justice Department, acting under {ts Voting Rights Act preclearance

authority. In previous cases in which the Court struck down

challenged districts, the legislatures drew the challenged plans

after their initial plans had been denied preclearance by the

Department of Justice under its "‘mlack=-maximization" policy. 3Saa

”

FROM NC RAG SPECIAL LITIGATION 919-716-6763 85,27. 1998 15:30

19-13/88 16:38 EPT0$ a SAM J EMVIN 117 » ooo iy

Millar, 515 U.S. at $21. For example, in Miller, the Court found

that the creation of the unconstitutional digtrict wag in direct

response to having had two previous plans denled preclearance by

the Justice Dapartment., gga id. (‘There is little doubt that the

state's trues interest in designing the Eleventh District was

creating a third majority-minerity district to satisfy the Justice

Department's preclearance demands.”), In Shaw II, the Court

recognized that North Carolina dacided to draw two majority=-

minority districts in response to the Justice Dapartment's danial

of preclearanca to a previous plan. Shaw II, 135 L, Ed. 24 at 219

(noting that the ‘averriding purpcse (of the redistricting plan]

was to comply with the dictates of the Attorney General's Dec, 18,

1591 letter [denying preclearance to previous plan) and to create

two congressional districts with effective black voting

majorities’) (quotaticn omitted),

In contrast, while the Department of Justice granted

preclearance to the plan at issue in this czsae, the Department did

not engage in the kind of browbeating that the Supreme Court nas

found offensive in previous racial gerrymandering cases, In the

cages I hava cited, the Court ralied on thie direct evidence, that

the legislature wae primarily motivated by race, te invoke atrict

sorutiny of the challenged districts. tInlike thosa cames,

Plaintiffs have proffered neither direct nor circumstantial

avidence that the General Assembly was pressured by the Department

of Justice tc maximiza minority participation when it redrew the

congressional districts in 1997. In the absence of such svidence,

FROM NC RG SPECIAL LITIGRTION 919-716-6763 95.27.1998 15:20 P

08/13/05 18:88 704 sof SAM J ERVIN [11 a WILLY

-T

CIES JES

1 have littla reason to believe that the State is lass than candid

{n its avermentas to this court that race was not the predominant

factor usad by the legislature when crafting tha 1997 redistricting

plan.

In reaching its decision, the majority has relied heavily on

avidence that District 12 could have been drawn to include more

pracincts where a majority of registered votars are Democrats, but

that it was not so drawn, presumably for reasons that can be

predominantly explained on no other basis but race. I cannot agree

with the majority's interpretation of the evidence. The

Plaintiffs, and the aajority opinion, provide anecdotal avidanca

that certain precincts that border District 12, but were not

included in that district, have a high number of voters that are

registered Democrats, See gupra at 8-5. This evidance does not

take inte account, however, that voters often do not vote in

accordance with their registered party affiliation. The State has

argued, and I see no reason to disoradit their unecontrovaerted

agsertions, that the district lines were drawn based on votes for

Democratic candidates in agtual salegtiqne, rather than the number

of registered voters. gag Affidavit of Senator Roy A. Cooper, III

("Cooper Aff.") 48 (‘election results were the principal factor

which determined the location and configuration of all districts’).

The majority's avidenca algo ignores the simple fact that tha

redistricting plan must comply with the equal protaction principle

of "one person, ona vote.” Every voter nust go somewhsera, yet all

districts must remain relatively equal in population. Plaintiffs’

FROM MC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION 919-716-6763 95.27.1998 15131

09.11/48 18:68 704 8 I SAM J ERVIN I11 » gull vie

anecdotal evidence suggests that Democratic precincts could have

peen included in District 12 in certain areas, had the district

only been enlarged to include those places. BY necessity, however,

rhea district would need to have been reduced in size in other

places in order to accommodate the increasa in the overall

population in tha district. Had the State drawn thas linas in the

manner that Plaintiffs’ evidence implies it should have, it appears

that the State aimply would have traded a Democratic precinct in

one part of the district for a Democratic precinct in another part,

perhaps such line-drawing would have satisfied the Plaintiffs’

desire that District 12 contain more than a 87% white majority, but

I do not agree with the majority that the Constitution requires it.

tn contract to Plaintiffs' anecdotal evidence (which |{s

presented in an affidavit by plaintiffa’ counsel), the Btate has

presented far nore convincing evidence that race was not he

pradominant factor in the General Assembly's decision to draw

oigtrict 12 as it has been drawn. Saf Affidavit of Dr. David W.

peterson ("Peterson Aff£."). In his statistical analysis, Professor

Peterson traveled the antire circumfarance of District 12, looking

at both the party afrilliation and racial composition of the

precincts on either side of the district line. Based on an

analysis of the entire district, Professor Peterson concluded that

“the path taken hy the boundary of the Twelfth Diatrict can be

attributed to political considerations with at leaat aa much

atatigstical certainty as it oan be attributed to racial

considerations.” Paterson Aff. %3. In other words, examining the

19

FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION 919-716-6763 85.27.1998 15:31

00/13/88 18:57 704 @... SAM J ERVIN [I] » @o12/n18

antire circumference of District 12, rather than relying on

Plaintiffs' “pick and chooses" examples, thers is no statistical

avidence to support the conclusion that race was the General

Assembly's primary motive in drawing District 12.

Furthermore, tha majority sees fit to ignore evidence

demonstrating that not only did the legislature utilize traditional

race-neutral districting principles in drawing the Twelfth

District's lines, but that these principles predominated over any

racial considerations. According to the Suprema Court, these

“raca=-nautral' principles include, hut are not limited <o:

compactness, contiguity, respact for political subdivisions or

communities of interest, and incumbancy protection. &ea Bush Vv.

Vara, 135 L. Ed. 2d at 260; Millex, %15 U.S. at 916. The wajority

would apparently add "geographical integrity” wo this list,

although I am not clear what exactly they hean by that.’ Sea supra

at 22. Regardless of what {8 included on ths list, however, the

fact remains that the legislature relied more heavily on these

nautral principles than on race when it chose the boundaries of

District 12.

The compactness of District 12 is, admittedly, substantially

less than what has been deemed to be "ideal" and is the least

compact of all of North Carolina's twelve congressional districts.

‘The term "geographical integrity" does not appear in any of

the Supreme Court's voting rights cases, and the only lower court

case that expressly uses the term, DeWitt v, Wilson, 856 F. Supp.

1409, 1411 (E.D. Cal, 1994), did so only bscause it was a standard

met out in the state's constitution.

11

FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION 919-716-6763 85.27.1998 15:31 P.36

00/13/98 18:88 ©1704 Mos 8AM J ERVIN [11 rr 013/019

Sse supxa at 11 (citing Pildes & Niemi '"compuctness factors"),

Some district, however, must inevitably be the least compact; that

fact alone therafore if not dispositive. And because Digtrict 12

reflacts the paths of major interstate highway corridors which make

travel within the district extremely easy, it has a type of

“functional compactness" that is not necessarily reflected by tha

Pildes & Niemi factors. In addition, District 12 as it currently

stands is contiguous, Contrary to the majority's allusions to

"narrow corridors,” gaa supra at 7, the width of the district is

roughly equal throughout its length, zag Affidavit of Dr. Gerald R.

Wabster tbl. 1.

District 12 also was dasigned to join a clearly defined

"community of {ntaregt" that has sprung up among the inner-cities

and along the mors urban areas abutting the interatate highways

that are the backbone of the district. I do not sea how anyone can

argue that the citizens of, for example, the inner-city of

Charlette do not have mora in common with citizens of the inner-

cities of Statesville and Winaston-Salam than with their fellow

Mecklenburg county citizens who happen to reside in suburban or

rural areas.

The tricky business of drawing borders to protect incumbents

alae required the legislature to draw Dietrict 12 in the way it

did. District 12 had to be drawn in a manner that avoided placing

both Congressman Burz's and Cokle's residences inside ths district,

excluded Cabarrus County, where Congressman Hefner resides, and

still provided enough Democratic votes to protect incumbent

12

FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION 919-716-6763 B85.27+199%8 15:32

09/19./93 18:88 704 or ¥ SAM J ERVIN I11 » 204.019

P.37

Congressman Watt's ssat. Ame Cooper Aff. %10.

what I find to ba the predominating factors in drawing the

1997 Plan, however, wera the legislature's desira to maintain the

6-6 partisan balance in the House and to protact incumbents. S3aa

Cooper AZf. 8 (stating maintaining partisan balance was the

principal factor driving redistricting). Thesa ara legitimate

interests which have been upheld by the Suprsme Court in previcus

voting rights cases, mss, a.g., Bush v, Vera, 125 L. Ed. 2d at 260-

61, and wars proper concerns for the legislaturs here. As I noted

pafore, the majority's decision to look only at tha percentage of

registered Democrats in analyzing the district's borders ignores

the fact that registered Democrata are not compalled to vote for

Democratic candidates and often do not. In drawing District ig,

therefore, the lsgislature aid not consider meraly the numbar of

registered Democrats, rather it looked also to the history of

recent voting patterns in an attempt to design the districts to

ensure that the partisan balance would remain stable. Saas Cooper

Aff. 48; Feteraon Aff. §21.

Finally, I 2ind it highly unlikely, as the majority has found

today, that the General Assembly acted with predominantly racial

metives in its drawing of District 12, but did not act with the

same motive in its drawing of District 1. The General Assembly

considered the 1997 Redistricting Plan as 2 single, statewide

proposal, and it makes little sense to ne that the Ganeral Assembly

would have been animatad by pradominantly racial motives with

respect to the Twelfth District and not the First. This

13

FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGRTION 919-718-6763 85.27.1998 15:32 P

09/13/88 id:B9 704 pu SAM J ERVIN 1I1 i» 015/040

«38

inconsiatency is even more apparent when one considers that the

legislature placed more African-Americans in District 1 (46.34% of

the voting~age population) than in District 12. since va all agree

that the Plaintiffs have failed toc prove mny equal protection

violation with respect to the legislature's decision in drawing

District 1, I find it unlikely that Plaintiffs’ proof would

demonstrate otherwise with regard to other aspects of the sane

redistricting plan.

I1X.

Not only de I disagres with the majority in their holding the

Twelfth District unconstitutional, I believe that =-=- even if the

Twelfth District is unconstitutional -- they are in error in

enjoining the current election procees, which {is already

substantially underway, The rationale for allowing elections to

procesd after a court has declared them to ba constitutionally

infirm has been clearly articulated by the Supreme Court in

Raynolds v, Sime, 377 U.S. $533, 585 (19€4):

(O)nce a State's legislative appertionmant scheme has

been found to be unconstitutional, it would be the

unusual case in which a court would be justified in not

taking appropriate action to insure that no further

elections are conducted under the invalid plan. However,

under certain circumstances, such as where an impending

election is imminent and a State's electicn machinery is

alraady in progress, equitable considerations might

justify a court in withholding the granting of

immediately affective relief in a lagislative

apportionment case, evan though tha exlating

apportionment scheme was found invalid. In awarding or

withholding immediate relief, a court 1a entitled to and

should consider the proximity of a forthcoming eleetion

and the mechanics and complexities of state election

14

FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION 919-716-6763 85.27.1998

06/13/88 17:00 ®704 ef SAM J ERVIN 111) ® Rp a FL

lawa, and should act and rely upon gensral eguitable

principles. With respect to the timing of relief, a

court can reasonably endsavor to avoid a disruption of

the election process which might result from reguiring

precipitate changes that could make unreasonable Or

embarrassing demands on a State in adjusting to the

requirements of the court's decrees,

waighing the equities here, it is clear that this is cne of the

"ynusual" cases contamplated by Reynolds v, Sims and therafors an

injunction should not be issued at this peint in the election

cycles,

on January 30, 1998, when the plaintiffs filed their motion

ror a preliminary injunction tc these elections, the deadline for

candidates to fila for the primary elections was only four days

away. voters had already contributed over $3 nillion to the

congressional candidates of their choice, and the ocandidates

themselves had spent approximataly $1.5 million on their campaigns.

gaa Second Affidavit of Gary ©. Bartlett ("Bartlett Second ALE.)

114 (giving figures for the period from July 1 to Dscamber 31,

1997). Ballots have already been prepared, printed, and

distributed. Absentee balloting for the primary elactions began on

March 16, 1998 and undcubtedly some voters have already cast their

votes. The primary elections themselves are scheduled for May 6,

only a few short weeks avay. This court's injunction therefore

wreaks havec on an electoral process that is in full swing.

An injunction puts the North carolina legislature on the horns

of a dilemma. It may chooses te run the May 1998 elections as

scheduled for averything but the congressional primaries, and then

spend millions of dollars scheduling a separate slaction for the

15

FROM NC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION 919-716-6763 85.27.1998 15433

08/13/88 17:00 @704 v1 SAN J ERVIN 111 »

congressional primaries’ ~-- an election for which few people are

likely to make a special trip to the election booth. Or the State

may decide to spend nillions of dollars to reschedule tha entire

May election and affect hundreds of races for offices throughout

the State. Forcing the State to choose batwesn theses two equally

unpalatable choicas is unreasonabla.

In addition, the injunctien will disrupt candidates’

campaigning and votex contributions to those campaigns, Redrawing

the Twelfth Diutrict's boundaries will inevitably change the

boundaries of the surrounding districts, and the ripple effects of

this redrawing may well affect many other districts in the State,

as happened when the 1997 Plan supplanted the 1992 Plan.

congressional candidates cannot be certain whom thay will represent

or who their opponents will be until the districts ara redrawn.

voters likawise will be unsure whether the candidates of their

choice will end up in their district. Not only will contributions

to candidates and campaigning by candidates be slowed, Lf not

haltad, while the redistricting takes place, but once the

redistricting ls completed, candidates and voters will have scant

time to become acquainted with each other before elections take

place. Sees McKas v. Jamas, CV=97«C~2078-W (N.D., Ala, March 24,

1998) (refusing to enjoin elections even though qualifying date for

primary had not yet passed kecause "[@]ome energy is already

invested; some persone hava daclared their candidacy to represent

he cost of a single, statewide alection, primary or general,

is said to ba $4,300,000. Sga Bartlett Sacond Aff. §13.

16

FROM NC RG SPECIAL LITIGATION 919-716-6763 85:27.199%8 15133

09/14/94 12:40 704 434 3 saM J ERVIN [11 » PARLE RR VARY)

a certain diatrict...Even if redistricting were carviad out today,

it would diaturk the axpectacions of candidates and their

supporters, and it would disrupt the atate's conduct of the

primaries.”); smith vv. Beaslay, p46 F. Supp. 1174, 1212 (L.8.C.

1996) (refusing to issue injunction pix weeke Dbafore ganaeral

alection when "(candidates have already spent signirican< time and

money campaigning, and vetars have begun to familiarize themselves

with the candidates" Ekncause delay would disrupt alactions

unnecassarily and confuse voters). Accerd Vara v. Richards, 861 7.

Supp. 1304, 1351 (S.D. Tex, 1934), affirmed sub nam. Bush vv, Yara,

135 L. Xd. 24 245 (1996) (finding congressional districts

unconstitutional eleven weeks before general elections but allowing

them to proceed under unconetitutional apportionment plan). Thia

will negatively affect the quality of the representation that

~{tizens of North Carolina recaive in Congress, and counsels

against upsetting the current selections.

IV.

In its opinion, the majority concludes that neither tha

Plaintiffs nor the state has astablished the apsence >t a genuine

imgue of material fact that would entitle either party to judgment

as a matter of law, 34a SUPKa at 22-23. I believa that all

material fasts concerning the First District are unccntroverted «=

this panel received the same evidence concerning District 1 as it

did for District 12. 1f summary Judgment is appropriate for

pistrict 22, I see no reason why District 1's constitutionality

pi

FROM HC AG SPECIAL LITIGATION 919-716-6763 85.27.1998 15133 P.42

00-1498 12:30 ®T04 or I SAM J ERVIN 111 » RY

\J

cannot be decided on summary judgment as wall. The majority is

simply wrong to require the State to establish the abasence of an

isaue of material fact. 3as celotax Corp. vy. Catrett, 477 U.S.

117, 325 (1986) {("(W]ea do not think ... that the burden is on the

party moving for summary judgwmant. to produce evidence showing the

absence »f a genuine issue of material fact...."). Because I

waliava that the Plaintiffs have fajlad to demonstrate that tha

First Congressional Dietriot under the 1997 Congressional

Restricting Plan is an uneenstitutional clagaiflication hased on

race, I would grant ths state's motion for summary Judgmant,

Vv.

1 agree with the majorizy that plaintiffs hava failed to meet

their burden or summary judgmant as to District 1, although I would

yo further and grant she State's motion fox summary 4udgment as %

this district, I dissent from the majority's decision granting the

plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment on District 12, and

enjoining alactions under the 1997 Plan. Tor the reasons stated

apova, I would grant the state's motion for summary judgnent,

finding that Plaintiffs have not proven a violation of their right

to equal protection of the laws.

18

* kk END * % %