Cooke v. North Carolina Statement as to Jurisdiction

Public Court Documents

October 20, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cooke v. North Carolina Statement as to Jurisdiction, 1958. 63c26636-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e3266f77-5166-420c-8795-da61fe02cd55/cooke-v-north-carolina-statement-as-to-jurisdiction. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

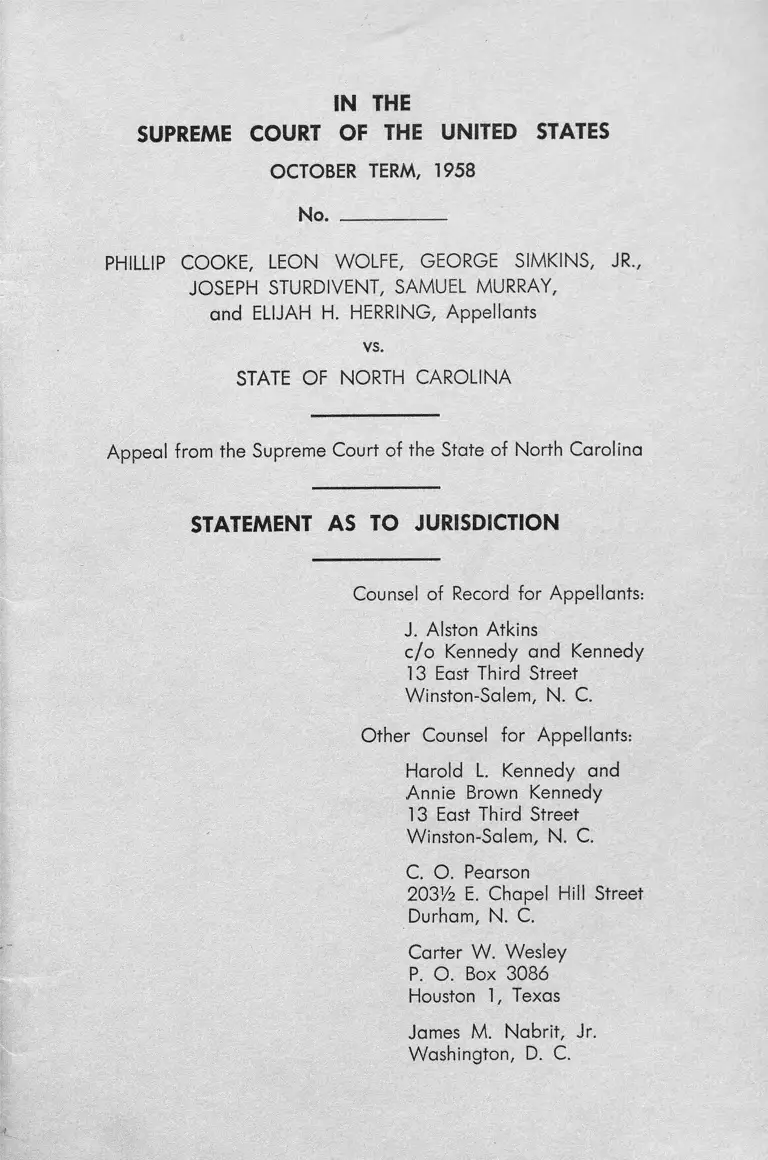

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM , 1958

No. _____________

PHILLIP COOKE, LEON W OLFE, GEORGE S IM KIN S, JR.,

JOSEPH STURD IVEN T, SAMUEL MURRAY,

and ELIJAH H. HERRING, Appellants

vs.

STA TE OF NORTH CAROLINA

Appeal from the Supreme Court of the State of North Carolina

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

Counsel of Record for Appellants:

J. Alston Atkins

c/o Kennedy and Kennedy

13 East Third Street

Winston-Salem, N. C.

Other Counsel for Appellants:

Harold L. Kennedy and

Annie Brown Kennedy

13 East Third Street

Winston-Salem, N. C.

C. O. Pearson

203’/2 E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, N. C.

Carter W . Wesley

P. O. Box 3086

Houston 1, Texas

James M. Nabrit, Jr.

Washington, D. C.

INDEX

Pages

Opinions in Court below:

Cited .........-............... -............................. -........—........—- 1

Reproduced ...................................................................... 42-53

55-59

Jurisdictional Grounds:

Nature of Proceeding ................. — ...... -........... . 2

Judgment Appealed from:

Date of Entry .............. ........-...................... -.......... 2

Reproduced ...............................-..........—............. 54

Petition for Rehearing not Permitted ........... .......... . 2

Notice of Appeal:

Date Filed .......................... ............. ...................... 2

Reproduced .................... .................................-..... 60-66

Statute Conferring Jurisdiction — ............ - ................ 2

Cases Sustaining Jurisdiction ............. ......... ............ - 2-4

Questions Presented ............. ............................... -................ 4-8

Statement of the Case:

Facts Material to Questions Presented .................. . 8-16

Raising of Federal Questions:

Motion to Quash _____ _____ ___________ _____ 16-19

Excluding Federal Court Records .................... 19-20

Motion to Set Aside Verdict................................ 20-28

Substantiality of Federal Questions:

Generally ............. ........... ....................................... 28-30

Supremacy Clause and Judicial Notice ........ 30-32

Federal Records Reproduced

for Judicial Notice ..................... .........— 67-79

Pleadings Setting up Federal R ig hts.................. 33-34

Discrimination against Federal Rights ............. 34-35

Due Process and Equal Protection

aside from Racial Exclusion ....................... 35-36

Changing Meaning of Criminal Statute ......... 37

Evidence of Racial Discrimination --------- ----- 37-38

Double Jeopardy under 14th Amendment .... 38-39

i

Reasons for Plenary Consideration ...... .............................. 39-40

Conclusion ..... ................ ................ ................. ................40-41

Tables of Cases Cited

Aaron v Cooper and Cooper v Aaron,_____US_____

(Decided September 29, 1958) ......................... . 3, 32

Aycock v Richardson, 247 NC 234, 100 SE 2d 379 .. 3, 35

Brock v North Carolina, 344 US 424, 429, 97 L ed

456, 460, 73 S Ct 349 ......................................... 3, 39

Brown v Board of Education, 344 US 1, 97 L ed 3, 73

S Ct 1 ...................................... ................ .......... ......... 3, 31-32

City of Greensboro v Simkins, 246 Fed 2d 425 ......... 4

Eubanks v Louisiana, 356 US 584, 2 L ed 2d 991,

994, 78 S Ct 970 ...... ................ ............................ 3, 37

Franklin National Bank v New York, 347 US 373, 98

L ed 767, 74 S Ct 550 ............................................... 3, 30

Hoag v New Jersey, 356 US 464, 2 L ed 2d 913,

917, 78 S Ct 829 ........................... ............................. 3, 38

Lambert v California, 355 US 225, 2 L ed 2d 228,

231, 78 S Ct 240 ................................................. 3, 37

L illy v Grand Trunk Western Ry Co., 317 US 481,

488, 87 L ed 411, 417, 63 S Ct 347 .............. ).. 3, 31

Marsh v Alabama, 326 US 501, 509, 90 L ed 265,

270, 66 S Ct 276, 280 .......................................... 2, 28-29

Mason v Commissioners of Moore, 229 NC 626, 627,

51 SE 2d 6 ................ ................................................. 3, 35

NAACP v Alabama, 357 US 449, 2 L ed 2d 1488,

1495, 78 S Ct 1163 ................. ............................. 3, 35

Niemotko v Maryland, 340 US 268, 271, 95 L ed

267, 270, 71 S Ct 325, 327 ................................ 2, 30

Pennsylvania v Board of Directors etc., 353 US 230,

1 L ed 2d 792, 77 S Ct 806 ................................ 4, 41

Public Utilities Commission of California v United

States, 355 US 534, 2 L ed 2d 470, 478, 78

S Ct 446 .................. .......................... .......... .............. 3, 30

Railway Employees Department etc. v Hanson, 351

US 225, 232, 100 Led 1112, 1130, 76 S Ct 714 2, 30

Simkins v City of Greensboro, 149 Fed Supp 562 .... 4, 10-16

Pages

ii

Pages

Smith v O'Grady, Warden, 312 US 329, 331, 85

L ed 859, 61 S Ct 572 .......................................... 3, 31

State v Clyburn, 247 NC 455, 458, 101 SE 2d 295 3, 6, 37

State v Cooke et al„ 248 NC 485, 103 SE 2d 846 .. 1, 42-53

State v Cooke et al„ 246 NC 518, 98 SE 2d 885 .... 1, 55-60

State v Council, 129 NC 371 (511), 39 SE 814 ____ 2

State v Jones, 69 NC 14 (16) ....... ............................. 2

State v Perry, 248 NC 334, 103 SE 2d 404 ............. 3, 6, 34

Staub v City of Baxley, 355 US 313, 2 L ed 2d 302,

309, 78 S Ct 277 ................................................. . 3, 33

Sweezy v New Hampshire, 354 US 234, 1 L ed 2d

1311, 77 S Ct 1203 .........- .................................- 3, 41

Tomkins v Missouri, 323 US 485, 89 L ed 407, 65

S Ct 370 ....... ............................. ................................. 3, 33

W illiam s v Georgia, 349 US 375, 99 L ed 1161,

75 S Ct 814 ................................ ............................ 3, 34

Rules of Court

Rules 13 and 15 of Revised Rules of Supreme

Court of United States ................................... 1

Constitution of North Carolina

Article IV, Sec. 8 ................................ ........................... 35

Constitution of United States

Article VI, Cl. 2 ......................... .............................. 4, 5, 20,

30-32

Fourteenth Amendment ................ ................ .............. 4, 5, 7, 8,

17, 19, 21,

22, 25, 27,

29, 30, 35,

37, 38

Federal Statutes

28 USC Sec. 1257 (2) ............................................... 2, 41

28 USC Sec. 2103 ................................................... 41

General Statutes of North Carolina (1953)

Sec. 14-134 ................................................................ 2, 4, 6, 8,

17, 27,

29, 30, 37

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UN ITED STA TES

October Term, 1958

No__________________

Phillip Cooke, Leon Wolfe, George Simkins, Jr,,

Joseph Sturdivent, Samuel Murray, and Elijah H. Herring,

Appellants

v

State of North Carolina

Appeal from the Supreme Court of the State of North Carolina

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

1. The above named appellants respectfully file this

Statement as to Jurisdiction pursuant to Rule 13 and Rule 15

of the Revised Rules of the Supreme Court of the United States.

(a) O PINIO NS IN THE COURT BELOW

The Opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

delivered upon rendering the judgment from which this appeal

is taken is reported in State v Cooke et al., 248 NC 485,

103 SE 2d 846. Said Opinion is attached hereto as

Appendix "A " and said Judgment is hereto attached as Ap

pendix "B " . The Opinion of the Supreme Court of North

Carolina upon a former trial upon another set of warrants

charging the identical trespass upon Gillespie Park Municipal

Golf Course is reported in State v Cooke et al., 246 NC 518,

98 SE 2d 885. That Opinion is hereto attached as Appendix

"C".

1

(b) G ROUNDS ON WHICH JURISDICTION IS INVOKED

(i) Th is is a criminal prosecution commenced in the Muni

cipal-County Court of Greensboro, Guilford County, North

Carolina, alleging a trespass by the above named appellants

upon the Municipal Gillespie Park Golf Course. The warrants

charging simple trespass were issued under Section 14-134

of the General Statutes of North Carolina (1953).

(ii) The Judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

appealed from in this case was entered and dated as of June

4, 1958, at the same time of the filing of the Opinion men

tioned as Appendix "A " above. Said Judgment affirmed and

found no error in the judgment of conviction and sentence

by the Superior Court of Guilford County, North Carolina,

entered on February 10, 1958, upon a trial de novo on appeal

from a judgment of conviction and sentence in the Municipal-

County Court of Greensboro. The sentence appealed from

is 15 days in jail for each of the above named appellants.

No Petition for Rehearing in a criminal case is permitted

in the Supreme Court of North Carolina. State v Jones, 69

NC 14 (16), State v Council, 129 NC 371 (511), 39 SE 814.

The Notice of Appeal to the Supreme Court of the United

States was filed in the Supreme Court of North Carolina on

August 27, 1958, and a copy is hereto attached as Appendix

"D ".

(iii) The statutory provision believed to confer jurisdiction

of this appeal on the Supreme Court of the United States is

28 USC 1257 (2).

(iv) It is believed by appellants that the following cases

sustain the jurisdiction of this Court in this case:

Marsh v Alabama, 326 US 501, 509. 90 L ed 265,

270, 66 S Ct 276, 280.

Niemotko v Maryland, 340 US 268, 271, 95 L ed 267

270, 71 S Ct 325, 327.

Railway Employees' Department etc. v Hanson, 351 US

225, 232, 100 L ed 1112, 1130, 76 S Ct 714.

2

Franklin National Bank v New York, 347 US 373, 98

L ed 767, 74 S Ct 550.

Public Utilities Commission of California v United

States, 355 US 534, 2 L ed 2d 470, 478, 78 S Ct

446.

Smith v O'Grady, Warden, 312 US 329, 331, 85 L ed

859, 61 S Ct 572.

L illy v Grand Trunk Western Ry Co., 317 US 481, 488,

87 L ed 411, 417, 63 S Ct 347.

Brown v Board of Education, 344 US 1, 97 L ed 3,

73 S Ct 1.

Aaron v Cooper and Cooper v Aaron,_____US______

(Decided September 29, 1958)

Tomkins v Missouri, 323 US 485, 89 L ed 407, 65 S Ct

370.

Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 US 313, 2 L ed 2d 302,

309, 78 S Ct 277.

State v Perry, 248 NC 334, 103 SE 2d 404.

W illiam s v Georgia, 349 US 375, 99 L ed 1161 ,75 S Ct

814.

Aycock v Richardson, 247 NC 234, 100 SE 2d 379.

Mason v Commissioners of Moore, 229 NC 626, 627,

51 SE 2d 6.

NAACP v Alabama, 357 US 449, 2 L ed 2d 1488,

1495, 78 S Ct 1163.

State v Clyburn, 247 NC 455, 458, 101 SE 2d 295.

Lambert v California, 355 US 225, 2 L ed 2d 228, 231,

78 S Ct 240.

Eubanks v Louisiana, 356 US 584, 2 L ed 2d 991, 994,

78 S Ct 970.

Hoag v New Jersey, 356 US 464, 2 L ed 2d 913, 917,

78 S Ct 829.

Brock v North Carolina, 344 US 424, 429, 97 L ed 456,

460, 73 S Ct 349.

Sweezy v New Hampshire, 354 US 234, 1 L ed 2d

1311, 77 S Ct 1203.

3

Pennsylvania v Board of Directors etc., 353 US 230

1 L ed 2d 792, 77 S Ct 806.

(v) The validity under the Constitution of the United States

of Section 14-134 of the General Statutes of North Carolina

(1953), as construed and applied by the State Courts in this

case, is drawn in question upon this appeal, and said Section

14-134, which was read to the jury by the Tria l Judge (Page

78 of printed Record below*), reads as follows:

" If any person, after being forbidden to do so, shall

go or enter upon the lands of another without a license

therefor, he shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and on

conviction shall be fined not exceeding fifty dollars or

imprisoned not more than thirty days."

The acts of appellants held by the State Courts to be a crime

under this statute were held by Declaratory Judgment of

the United States District Court for the Middle District of

North Carolina, affirmed by the Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit, to be the "constitutional rights" of the appel

lants.

(c) Q UESTIO N S PRESENTED BY TH IS APPEAL

The following questions are presented by this Appeal:

1. Is Section 14-134 of the General Statutes of

North Carolina (1953), as construed and applied by

the State Courts in this case, unconstitutional under the

Constitution of the United States, including the Su

premacy Clause (Art. 6, Cl. 2), and also including the

Fourteenth Amendment as interpreted by the United

States District Court for the Middle District of North

Carolina in George Simkins et al. v City of Greensboro

et al., 149 Fed. Supp. 562, and by the Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit affirming in City of Greens

boro et al. v. George Simkins et al. 246 Fed. 2d 425?

2. Could the State agencies in this case, namely,

City of Greensboro, Greensboro City Board of Educa

tion, and Gillespie Park Golf Club, Inc., consistent

with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

*See note on page 41.

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States,

promulgate written regulations converting the public

municipal Gillespie Park Golf Course, originally con

structed with the Federal Government providing 65 per

cent of the cost, into a private-club membership-only

golf course, excluding all citizens who did not meet the

membership rules? and do the membership rules as set

out in the record thus limiting the use and enjoyment of

this public municipal golf course, having been promul

gated by State agencies, violate the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment? and, said State

agencies having adopted a written rule making eligible

to play on said public municipal golf course "members

in good standing of other golf clubs," could the State

agencies operating the golf course, consistent with the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

arb itrarily in practice limit use and enjoyment of the

golf course to those "members in good standing of

other golf clubs" whose golf clubs were members of the

Carolina Golf Association?

3. Was it the duty of the State Courts in this case

to accept as true the allegations asserting appellants'

Federal rights in their motion to quash the warrants

and in their motion to set aside the verdict and for

judgment notwithstanding the verdict, in view of the

fact that the State did not answer to deny or con

trovert any of said allegations?

4. In its opinion in this case the Supreme Court of

North Carolina having said, with reference to the Fed

eral case cited in Question No. 1 above, that "O ur

knowledge of the facts in that case is limited to what

appears in the published opinion," and having also

said that " It would appear from the opinion that the

entry involved in this case was one incident on which

plaintiffs there relied to support their assertion of un

lawful discrimination," was it the duty of the State

Courts in this case, under the Supremacy Clause (Art.

6, Cl. 2) of the Constitution of the United States, to

consider and give effect to all of the facts set forth in

5

said opinion of the Federal Court, and having taken

judicial notice of said opinion, was it also the duty of

the State Courts under the Supremacy Clause to take

judicial notice of the Federal Court's Findings of Fact,

Conclusions of Law, and Declaratory Judgment, in

order to determine the extent to which the acts and

conduct held by the State Courts to be a crime in this

case were held by the Federal Courts to be protected

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States?

5. The Supreme Court of North Carolina having

held on May 7, 1958 in State v. Perry, 248 N. C. 334,

that the unconstitutionality of a jury panel under the

Constitution of the United States could be shown by

evidence upon a motion to quash the indictment, was it

a discrimination against the Federal rights asserted by

appellants in this case for the State Courts to deny the

request made by the appellants in their motion to

quash the warrants and again in their motion to set

aside the verdict, for an opportunity to present the

record in the Federal case cited in Question No. 1

above upon the hearing of said motions?

6 . Was it a d iscrimination against and an infringe

ment upon the Federal rights asserted by appellants in

this case for the State Courts to refuse to give effect to

Finding of Fact No. 30 and Finding of Fact No. 33 in

the Federal case cited in Question No. 1 above, both

of which Findings of Fact were quoted verbatim in

appellants motion to set aside the verdict, and the

State not having answered to deny or controvert the

allegations of said motion in any way?

7. The Supreme Court of North Carolina having

held consistently prior to this case that said Section

14-134 of the General Statutes of North Carolina did

not apply to public lands but only to "the possession

or right of possession of real estate privately held,"

(State v. Clyburn, 247 N. C. 455), was it a discrimina

tion against the Federal rights asserted by appellants

6

for the North Carolina Supreme Court to depart from

this rule and hold that the statute did apply to the al

leged trespass upon the public municipal golf course

involved in this case?

8. The Supreme Court of North Carolina having

approved in its opinion in this case the charge to the

jury that " i f a party entering upon the land has a legal

right to do so, of course he may not be convicted of a

trespass," and the Declaratory Judgment in the Federal

case cited in Question No. 1 above having declared

that the interference with and causing appellants to be

arrested for playing on the golf course "was done

solely because of the race and color of the" appellants

"and constitutes a denial of their constitutional rights,"

(said Declaratory Judgment being quoted verbatim in

appellants' motion to set aside the verdict, and the State

having not answered to deny or controvert said mo

tion), was it a violation of the duty of the State Courts

under the Supremacy Clause and of the rights of ap

pellants under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States for the Supreme Court

of North Carolina to hold in this case that the State

Courts were not concluded by the Federal Court's

determination of the "constitutional rights" of the ap

pellants, and to submit to the State's jury the determi

nation of this Federal "legal right" of appellants under

the Constitution of the United States to play on this

public municipal golf course?

9. The Supreme Court of North Carolina having

gone outside the record before it to find in its opinion

in this case the true fact concerning the Federal case

cited in Question No. 1 above that "defendants had

the record in that case identified," did the Equal Pro

tection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment require

the Court to note the further true fact that the records

in said Federal case were in fact identified as "De

fendants' Exhibits 6 and 7 ," in order that the Court

might see the further true fact that said Exhibits 6 and

7 were in fact offered in evidence and their admission

7

refused by the Tria l Judge, as shown on Page 77 of

the printed record before the Supreme Court of North

Carolina?

10. Appellants having been tried twice upon two

separate and different sets of warrants for the same

alleged offense in the Municipal-County Court of

Greensboro, Guilford County, North Carolina, and the

first set of warrants and the conviction and sentence

thereunder being still outstanding and undisposed of

at the time of the issuance of the second set of war

rants and the trial and conviction thereunder, does the

second tria l and conviction and sentence amount to

the kind of double jeopardy which the 14th Amend

ment forbids as a denial of due process?

(d) STA TEM EN T OF TH E CASE

Appellants have been tried twice upon two separate and

successive sets of warrants in the Municipal-County Court of

Greensboro, Guilford County, North Carolina, for the same

identical acts of playing golf on the public Municipal Gillespie

Park Golf Course. In between these two tria ls appellants

were compelled to defend bills of indictment in the Superior

Court of Guilford County, North Carolina, for the same iden

tical acts of playing golf on said golf course. A ll of said

warrants and indictments charged that said same identical

acts of playing golf were a crime under Section 14-134 of the

General Statutes of North Carolina (1953), which statute is

quoted above in (v).

After said first trial upon said first set of warrants and

while the case was pending on appeal in the Supreme Court

of North Carolina, the United States District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina, in Civil Case No. 1058,

George Simkins et al. v City of Greensboro et al., entered

its Declaratory Judgment covering said same identical acts

of playing golf on the public Municipal Gillespie Park Golf

Course. Said Declaratory Judgment appears verbatim on

Page 92 of the printed Record below and reads as follows:

" It is now ordered, adjudged and decreed that

defendants have unlawfully denied the plaintiffs as

residents of the City of Greensboro, North Carolina,

the privileges of using the Gillespie Park Golf Course,

and that this was done solely because of the race and

color of the plaintiffs, and constitutes a denial of their

constitutional rights, and unless restrained will con

tinue to deny plaintiffs and others sim ilarly situated."

The Supreme Court of North Carolina arrested judgment

on the judgment of conviction and sentence coming from the

de novo trial in the Superior Court of Guilford County,

North Carolina, under said first said of warrants, not upon

any ground of appeal set up by appellants, but because the

Court found that the Superior Court lost jurisdiction and its

actions became a nullity when it permitted the warrants to be

amended to change the name of the prosecuting witness from

Gillespie Park Golf Course to Gillespie Park Golf Club, Inc.

No further action was taken either by the Supreme Court or

the Superior Court of Guilford County with reference to said

first set of warrants, but the Supreme Court did say that the

appellants could "now be tried under the original warrant

since the court was without authority to allow the amend

ment." (246 NC 521).

After the United States District Court for the Middle

District of North Carolina had entered its said Declaratory

Judgment and after it had been affirmed by the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit and had become final, at the

October 21st, 1957, Term of the Superior Court of Guilford

County, North Carolina, appellants were indicted and com

pelled to defend against indictments charging the identical

trespass for the identical acts covered by said first set of

warrants and also covered by said Declaratory Judgment of

the said Federal Court. Said indictments appear on Pages

33 to 39 of the printed Record below. When said indictments

were called for trial on December 2, 1957, the State took

"a Nol Pros with leave" in all of said indictments. (Page 39 of

printed Record below).

Appellants were then immediately arrested on December

2, 1957, on a new set of warrants in said Municipal-County

9

Court charging the identical trespass for the identical acts

covered by said first set of warrants and also by said indict

ments and also by said Declaratory Judgment of said Federal

Court.

Appellants were tried and convicted and sentenced in

said Municipal-County Court upon said second set of warrants,

and upon appeal were tried, convicted and sentenced to 15

days in jail in a de novo trial in Superior Court of Guilford

County, North Carolina. The Supreme Court of North Caro

lina affirmed and found no error and this appeal is from the

final judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina men

tioned above as Appendix "B ".

The effect of the proceedings in the Federal case of George

Simkins et al. v City of Greensboro et al., 149 Fed Supp 562,

affirmed in City of Greensboro et al. v George Simkins et al.,

246 Fed 2d 425, is one of the crucial issues in this case. The

Supreme Court of North Carolina in its Opinion in this case said

that the United States District Court's Opinion in said Simkins

case was before the State Courts and that "O ur knowledge

of the facts in that case is limited to what appears in the

published opinion." (See Appendix "A ", Page 50.)

Appellants, therefore, insert said Opinion of said United

States District Court, as follows:

OPIN ION

Hayes, District Judge:

The City of Greensboro and the Greensboro City

Board of Education concede that they cannot own and

operate the Gillespie Park Golf Course for the public

and exclude the plaintiffs and other Negro citizens of

Greensboro from these privileges on account of their

color.

Although the golf course has been available to the

public for many years, whether by design or other

wise, Negroes have been denied the enjoyment of the

privilege.

10

The City of Greensboro, before Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U.S. 483, in an effort to comply

with Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, erected in the

City of Greensboro a nine-hole golf course for Ne

groes, known as Nocho Park Golf Course, but it can

not be deemed the equivalent of an 18-hole golf course

like Gillespie Park course which was restricted to white

people.

The Board of Education leased the land it did not

need for school purposes at the time to the City of

Greensboro. Through W orks Progress Administration,

which furnished 6 5 % of the cost, the City of Greens

boro built the last nine holes and agreed not to sell or

lease for private use this public property during its

life or usefulness.

Some of the Negro citizens applied to the City

authorities for permission to play on the Gillespie Park

course in 1949 and, because of opposition on the part

of local citizens against Negroes playing on the course,

after some negotiation, the City of Greensboro and

City Board of Education entered into a lease contract

whereby the entire golf course was leased to Gillespie

Park Golf Club, a non-profit corporation which was

organized solely for the purpose of taking the lease

and maintaining and operating the course as a public

golf course. G.S. 55-11

It is true the directors met with a quorum at first

and fixed $60.00 for annual membership which per

mitted them to play without paying additional fees;

also authorized $ 1.00 membership who would pay

$1.25 greens fees on holidays and weekends, and 75

cents on other days.

The records of the corporation do not disclose suf

ficient data to show if rules were really established and

enforced in respect to membership. The evidence does

clearly show that white people were allowed to play

by paying the greens fees without any questions and

without being members. When Negroes asked to play,

11

they were told they would have to be members be

fore they could play and it clearly appears that there

was no intention of permitting a Negro to be a mem

ber or to allow him to play, solely because of his be

ing a Negro.

The six plaintiffs presented themselves at the desk

of the man in charge of the golf course and laid

down 75 cents each and asked to play, the first named

plaintiff being a dentist and practicing his profession

in Greensboro. But they were not given permission to

play. They insisted on their right to play and played

three holes. W hile playing the third hole, the manager

came and ordered them to leave, and they refused to

go unless an officer arrested them. Whereupon the

manager swore out a warrant charging each with tres

pass upon which they were tried, convicted and sen

tenced to 30 days in jail, the Statutory limit, from

which an appeal is pending in the Supreme Court of

North Carolina.

The Negroes have not only been denied the privi

lege of the golf course, but there is no intention on the

part of the defendants to permit them to do so unless

they are compelled by order of court.

Th is case presents two questions for determination.

First are plaintiffs, being citizens and taxpayers of the

City of Greensboro, entitled to the privilege of play

ing on the defendant's golf course as long as it is

owned and used for the convenience of the citizens of

Greensboro? Second. Can the defendants avoid giv

ing equal treatment to the plaintiffs in the use of the

facility by leasing it to a private corporation or can

the lessee deny plaintiffs the right to play solely on ac

count of color and thereby accomplish a result which

is denied to the owner.

It is conceded that the defendants ordinarily are

not required to furnish a golf course for its citizens. If,

however, it undertakes to do it out of the public treas

ury, it cannot constitutionally furnish the facility to a

12

part of its citizens and deny it to others sim ilarly sit

uated.

The plaintiffs as citizens of the City of Greensboro

are entitled to the equal protection of the law and can

not be deprived of their rights solely on account of

color. The doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, of

equal but separate facility has been over-ruled in

Brown v. Board of Education, supra.

Before Brown v. Board of Education, supra, the

Supreme Court held that the election laws of the State

could not be delegated to a political organization and

empower it to deny Negroes the right to participate

in the primary, and the action of such an agency was

State action within the meaning of the Fourteenth

Amendment and that the discrimination against the

Negroes violated the Amendment. Nixon v. Condon,

286 U.S. 73. The members of the Supreme Court who

declared that law were Chief Justice Hughes, and As

sociate Justices Brandeis, Stone, Roberts and Cardozo.

It is appropriate to quote from Justice Cardozo's

opinion:

"The test is whether they are to be classified as

representatives of the State to such an extent and in

such a sense that the great restraints of the Constitu

tion set limits to their action.

"W ith the problem thus laid bare and its essentials

exposed to view, the case is seen to be ruled by Nixon

v. Herndon, supra, Delegates of the States's power,

have discharged their official functions in such a way

as to discriminate invidiously between white citizens

and black. Ex parte Virginia, supra,- Buchanan v. War-

ley, 245 U.S. 60, 77. The Fourteenth Amendment,

adopted as it was with special solicitude for the equal

protection of members of the Negro race, lays a duty

upon the court to level by its judgment these barriers

of color."

To the same effect is Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387

(4CCA).

13

The Fourth Circuit Court has ruled that public parks

are controlled by the same principles of constitutional

law as are controlling in public education. Dawson v.

Baltimore, 220 Fed. 2d 386, affirmed 350 U.S. 877.

Again that court held in Department of Conservation

v. Tate, 231 Fed. 2d 615, that citizens of the State

have right to use parks thereof without discrimination

on ground of race; that these rights cannot be abridg

ed by leasing parks with ownership being retained by

the State. Derrington v. Plummer 5CCA-240 F. 2d, 922.

Judge Moore in Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp.

1004, in a sim ilar situation said:

" it is not conceivable that a city can provide the

ways and means for a private individual or corpora

tion to discriminate against its own citizens. Having

set up the swimming pool by the authority of the legis

lature, the city, if the pool is operated, must operate

it itself, or, if leased, must see that it is operated with

out any such discrimination."

The brief filed by the City of Greensboro contains

this significant statement in its statement of facts:

"In December, 1955, s ix of ten plaintiffs in this ac

tion were denied the use of Gillespie Park Golf Course

by employees of Gillespie Park Golf Club, Inc. That

same month the City Council instructed the City Man

ager to proceed forthwith to receive bids for the sale

of Gillespie Park Course and upon such sale to dose

the Nocho Park course. The land upon which the latter

is situated is to be used for governmental purposes

and is not to be sold."

The facts show that the City is still "in the saddle"

so far as real control of the park is concerned and that

the so-called lease can be disregarded, if and when,

the City decides to do it. It also lends powerful weight

to the inference that the lease was resorted to in the

first instance to evade the City's duty not to discrim

inate against any of its citizens in the enjoyment in the

14

use of the park. The threatened sale is the procedure

pursued in Clark v. Flory, 141 F. Supp. 248; affirmed

in 237 Fed. 2d. 597.

The City of Greensboro contends that Holmes v.

Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879; Hayes v. Crutcher, 137 F. Supp.

853; Augustus v. Pensacola, Fed. Supp. , N. D.

Fla., and Holley v. Portsmouth, Fed. Supp.

(E.D. Va.) are inapplicable because they dealt with

anticipated leases while in the instant case the lease

existed before this suit was brought. It further contends

that the lease is valid under the North Carolina law

and therefore the valid existing lease "freezes" the

status quo and leaves the court without power to do

anything. If this logic is sound constitutional rights are

a delusion and a snare. Such hitherto sacred rights

can not be abridged by a mere lease between the city

and a third party and the courts are not made impo

tent to afford relief. To hold otherwise would open a

Pandora's box by which governmental agencies could

deprive citizens of their constitutional rights by the arti

fice of a lease. If the lessee desires to continue to op

erate the golf course, it must do so without discrimina

tion against the citizens of Greensboro. Th is public

right can not be abridged by the lessee so long as the

course is available to some of the citizens as a public

park, it can not be lawfully denied to others solely

on account of race.

The private corporation challenges the right of

plaintiffs here because it contends they have not ex

hausted their administrative remedies, relying on Car-

son v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d. 724, and other cases deal

ing with enrollment in educational institutions. These

cases are not in point. Th is golf dub permits white peo

ple to play without being members, or otherwise, ex

cept it requires the prepayment of green fees. The

plaintiffs here paid their fees, were forced off the

course by being arrested for trespass. Everybody knows

this was done because the plaintiffs were Negroes and

for no other reason. Th is court can not ignore it. More-

15

over, there existed no known and uniform procedure of

an administrative nature to be exhausted by plaintiffs.

Admittance to a park or golf course is unlike enrolling

in an educational institution.

A decree w ill be entered declaring that these plain-

iffs have been denied on account of their color, equal

privileges to use the golf course owned by the City

Board of Education and the City of Greensboro and

operated by the Gillespie Park Golf Club, and perma

nently restraining the defendants from discriminating

against plaintiffs and other members of their race on

account of color, so long as the golf course is owned

by these agencies and operated for the pleasure and

health of the public, their agents, lessees, servants and

employees.

The court invited counsel for the respective par

ties to confer and to suggest to the court the best prac

tical way to make effective the decree, in the event

the plaintiffs prevailed. The final decree w ill be de

ferred a short time to get the result of this conference.

Citizenship in the United States imposes uniform

burdens, such as paying taxes and bearing arms for

the preservation and operation of our government.

In like manner whatever advantages or privileges one

citizen in the United States may enjoy through his lib

erty becomes the constitutional right of each citizen

and without regard to race, color or creed. These prin

ciples of law have been fully and elaborately estab

lished in the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals and by

the Supreme Court of the United States and must be

adhered to in this case.

This the 18th day of March, 1957.

/s/ Johnson J. Hayes

United States District Judge

Raising of Federal Questions Below

Appellants first raised Federal questions sought to be re

viewed by this appeal by a written motion to quash the war

16

rants in Municipal-County Court. The State did not answer

the allegations of the motion. The Supreme Court of North

Carolina said in its Opinion in this case: "Defendants moved

in the Municipal-County Court to quash the warrants. Their

motions were overruled. They then entered pleas of not guil

ty ." (Appendix "A " attached hereto, Page 42.)

Appellants renewed these written motions to quash in the

Superior Court and the State did not answer the allegations

of the motion. The Supreme Court of North Carolina said in

its Opinion in this case: "Before pleading to the merits in the

Superior Court, defendants renewed their motions to quash

as originally made in the Municipal-County Court. The mo

tions made in apt time were overruled by the court." (Ap

pendix "A " attached hereto, Page 43.)

The written motion to quash is at Pages 28 to 32 of the

printed Record below. The following is quoted from Pages

28 to 30:

Motion to Quash

Now come the defendants, and each of them all

being Negro citizens of Greensboro, North Carolina,

through counsel, and make the following Motion:

That the warrants in the above-titled cause charg

ing these defendants, and each of them with simple

trespass based on GS 14-134 be quashed for the rea

son that GS 14-134 is hereby being unconstitutionally

applied to these defendants, on the following grounds:

1. The State of North Carolina in this prosecution

is, contrary to the Supremacy Clause of the United

States Constitution, attempting to make a crime out

of specific acts and conduct which both the United

States District Court for the Middle District of North

Carolina and the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit have specifically held to be protect

ed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States. In support of this assertion the

defendants show to the Court the following:

17

(a) Based upon the specific facts and conduct al

leged by the State to be a crime in this case, these de

fendants brought Civil Action No. 1058 in the United

States District Court for the Middle District of North

Carolina, praying for a declaratory judgment and a

decree enjoining the prosecution witnesses and the

City of Greensboro and the Greensboro City Board of

of Education from interfering with the defendants and

all other Negroes sim ilarly situated from playing golf

on the Gillespie Park Golf Course.

(b) A full hearing was held before United States

District Judge Johnson J. Hayes, who on April 24,

1957, found specifically that the prosecuting witnesses

and the City of Greensboro had refused to permit these

defendants to play golf "p rim arily because of their

color" (Finding of Fact No. 33), and concluded as a

matter of law that these defendants "and other Ne

groes sim ilarly situated cannot be denied on account

of race, the equal privileges to the park, notwithstand

ing the lease." In addition to his Findings of Fact and

Conclusion of Law, Judge Hayes filed an opinion in

the case and entered a "decree and injunction" enjoin

ing the prosecuting witnesses and the City of Greens

boro and the Greensboro City Board of Education from

interfering with these defendants in playing golf on

the Gillespie Park Golf Course. The prosecuting wit

nesses and the City of Greensboro appealed and this

decree was subsequently affirmed by the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

(c) These defendants have subpoenaed the Clerk of

the United States District Court for the Middle District

of North Carolina to bring to this trial the full record

and judgment roll in said case and respectfully request

an opportunity to offer this evidence upon the hear

ing of this motion.

(d) Defendants respectfully urge the Court to re

ceive and consider the record and judgment roll in the

Federal case and after such consideration to estop the

State and the prosecuting witnesses from proceeding

18

further with this prosecution. To permit this prosecu

tion to proceed would be in effect to nullify and ren

der ineffectual the judgment and decree of the United

States Courts contrary to the Supremacy Clause of the

United States Constitution and such prosecution would

violate the rights of these defendants and laws of the

United States, including the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Supreme Court of North Carolina in its Opinion in

this case held that the proceedings in the Federal Court case

of Simkins v Greensboro, supra, with the exception of the

Opinion, could not be shown on the motion to quash for the

reason that the record of such proceedings, except the Opin

ion, was "evidence aliunde the record." But, with reference to

the allegations in the written motion to quash, the Supreme

Court of North Carolina did say: "Since none of the reasons

nor all combined sufficed to sustain the motion to quash, the

court correctly overruled the motion and put the defendants

on trial for the offense with which they were charged." (Ap

pendix "A ", hereto attached, Page 45.)

Tria l Court Refused to Admit Federal Records

On Page 14 of appellants' brief before the Supreme

Court of North Carolina in this case is the following assign

ment of error: "The Court erred in refusing to admit defend

ants' Exhibits 6 and 7, as set out in Exception No. 22. These

exhibits were the decrees, the findings of fact, conclusions of

law and opinion of the Federal District Court in the Simkins

case and the opinion of the Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit,

in the same case." (See Transcript of Record, Page 121.) The

offer of these Exhibits 6 and 7 and the refusal of the Tria l

Court to admit them and the Exception No. 22 all appear

on Page 77 of the printed Record below.

The Record is silent as to the identification of these Fed

eral Court records as Exhibits 6 and 7, but the Supreme Court

of North Carolina says in its Opinion in this case the follow

ing with reference to said Federal Court records: "Although

the defendants had the record in that case identified, they

did not offer it in evidence." (Appendix "A " hereto attached,

19

Page 50). The only document other than appellants' brief

mentioned above, which shows the identification of the Fed

eral Court records, so far as appellants know, is the Official

Court Reporter's Transcript of the Testimony, which shows on

Page 59 that "the documents referred to were marked for

identification Defendants' Exhibits 6 and 7 ". The Supreme

Court of North Carolina having gone outside the printed rec

ord to find the true fact that the Federal Court records were

identified, appellants believe that it is proper for them to

include this material in the statement of the case, showing how

the Federal records were identified, in order to show the fur

ther true fact, which does appear in the record that the Tria l

Court refused to admit said Exhibits 6 and 7 into evidence.

Motion to Set Aside the Verdict

Appellants filed in the case in the Superior Court a w rit

ten motion to set aside the verdict and for judgment notwith

standing the verdict. The State did not answer the allegations

of this motion. The allegations of the motion to quash were

repeated by reference and in addition the following allega

tions were included in the motion to set aside the verdict (said

motion appearing on Pages 9] to 97 of the printed Record

below):

II. That the Supremacy Clause (Article VI) of the

Constitution of the United States requires this Court to

give effect to and to enforce the judgments of the

United States Courts covering the subject matter of this

prosecution, particularly the "Decree and Injunction"

of the United States District Court for the Middle Dis

trict of North Carolina, in Civil Case No. 1058, in

which these defendants were plaintiffs and Gillespie

Park Golf Club, Inc., was one of the defendants, cov

ering the identical acts and conduct charged by the

State to be a crime of trespass in this case, said "De

cree and Injunction" reading in part as follows:

" It is now ordered, adjudged and decreed that de

fendants have unlawfully denied the plaintiffs as res

idents of the City of Greensboro, North Carolina, the

privileges of using the Gillespie Park Golf Course, and

20

that this was done solely because of the race and color

of the plaintiffs, and constitutes a denial of their con

stitutional rights, and unless restrained w ill continue to

deny plaintiffs and others sim ilarly situated."

That the State of North Carolina and its Jury in

this case undertake to find to be criminal the identical

acts and conduct which said "Decree and Injunction"

holds to be protected by the Constitution of the United

States, and further undertake to find to have been law

fully done, that which said "Decree and Injunction"

holds was "unlawfully done," and that to permit said

verdict to stand and to punish these defendants on

the basis of said verdict would nullify and render in

effectual the rights of these defendants which said "de

cree and injunction" holds to be guaranteed and pro

tected by the Constitution and laws of the United

States, including the due process and equal proctec-

tion clauses of the 14th Amendment.

III. That a written opinion was handed down in the

said case in the United States District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina by United States Dis

trict Judge Johnson J. Hayes, which opinion is reported

in 149 Fed. Supp. 562, and in which Judge Hayes said

of the identical acts and conduct which the verdict finds

to be criminal in this case, the following:

"Th is golf club permits white people to play with

out being members, or otherwise, except it requires the

payment of greens fees. The plaintiffs here paid their

fees, were forced off the course by being arrested for

trespass. Everybody knows this was done because the

plaintiffs were Negroes and for no other reason. This

Court cannot ignore it."

Defendants respectfully request this Court to take ju

dicial notice of this matter of common knowledge per

taining to this public golf course owned and operated

by their agency by the City of Greensboro and the

Greensboro City Board of Education. That this matter of

common knowledge about the Gillespie Park Golf

21

Course was spoken truly and not idly by Judge Hayes

when he wrote that "everybody knows" it was shown by

Jurors in this case in their answers to questions touching

their qualifications. Those who had played on Gillespie

Park Golf Course stated very frankly and freely in

open court that they had played on this course without

any requirements except the payment of greens fees.

Defendants respectfully suggest that, if any confirma

tion of Judge Hayes' statement that this was common

knowledge which "everybody knows" is necessary it

is found in these statements of the Jurors in this case.

Defendants respectfully suggest to the Court that

to permit this verdict to stand under these circumstances

would violate the rights of these defendants under

the Constitution and laws of the United States, in

cluding the due process and equal protection clauses

of the 14th Amendment.

IV. That said "Decree and Injunction" of the United

States District Court for the Middle District of North

Carolina begins as follows:

"Th is cause coming on for hearing and the Court

having heard the evidence and argument of counsel

and carefully considered the same and the briefs filed,

and having made the findings of fact and conclusions

of law which appear of record."

Defendants respectfully suggest to the Court that

this reference in said "Decree and Injunction" to the

findings of fact and conclusions of law which appear of

record makes them a part of the "Decree and Injunc

tion" just as if written out therein in fu ll; and for this

reason and also because said findings of fact and

conclusions of law are a part of the record and judg

ment roll in said case in the United States District

Court for the Middle District of North Carolina cover

ing the identical acts and conduct which said verdict

seeks to make a crime, the Supremacy Clause of the

Constitution of the United States lays a duty upon

this Court to respect and give effect to said findings of

22

fact and conclusions of law, and especially to Finding

of Fact 33, which reads as follows:

"W hite citizens of Greensboro are given the priv i

lege of becoming permanent members by p a y i n g

$60.00 per year without greens fees and others not

permanent members by paying $ 1.00 per year and

greens fees of $.75, except on holidays and weekends,

when it is more. On days other than holidays and

weekends when greens fees are $1.25 white citizens

are permitted to play without being members by pay

ing the fees above set forth and without paying the

extra $ 1.00 and without any questions being put to

them. When the plaintiffs applied to be given the

same privilege they were refused on the ground that

they were not members but primarily because of their

color. Plaintiffs laid the greens fees on the table in the

club house, went out to play and after they had gotten

to the 3rd hole the 'pro' in charge of the golf course or

dered them off and they insisted they had a right to

play and would not get off unless they were arrested by

an officer, whereupon the 'pro' had them arrested

and they were tried and convicted and sentenced to

imprisonment for a period of 30 days, which is the

maximum under the law for the State of North Caro

lina for trespassing."

Defendants further respectfully show to the Court

that on these facts Judge Hayes said in his opinion the

following:

"Citizenship in the United States imposes uniform

burdens, such as paying taxes and bearing arms for

the preservation and operation of our government.

In like manner, whatever advantages or privileges one

citizen in the United States may enjoy through his

liberty becomes the constitutional right of each citizen

and without regard to race, color or creed. These prin

ciples of law have been fu lly and elaborately estab

lished in the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals and by

the Supreme Court of the United States and must be

adhered to in this case."

23

Defendants respectfully suggest to the Court that

the verdict in this case not only does not adhere to

these principles, but if permitted to stand would seek

to thwart and nullify these principles; and that said

verdict should be set aside to permit said principles to

be adhered to and vindicated.

V. That the evidence in this case and the instruc

tions of the Court to the Jury show that the land on

which Gillespie Park Golf Course is situated is public

and not private property, whereas G S 14-134, which

is the North Carolina statute under which the warrants

were drawn in this case, is meant to cover private

property and not public property. Said statute reads:

" I f any person after being forbidden to do so

shall go or enter upon the lands of another without

a license therefor, he shall be guilty of a misde

meanor, . . . "

Defendants respectfully suggest to the Court that

this statute was never intended to apply to public

lands or public property, but was and is intended to

apply solely and only to private property, and that

the lands and property and the possession alleged

to have been invaded in this case was public lands

and property and the possession of an agency of the

City of Greensboro and the Greensboro City Board

of Education, which held the title to said lands and

property. In this connection defendants respectfully

call the Court's attention to Finding of Fact No. 30 in

said case in the United States District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina:

"That the leases in this case undertook to turn over

to a corporation having no assets or income highly

valuable income-producing property belonging to the

City and the school board, the chief officer and pro

moter of said corporation being an official of the city,

and the city having no prospect of getting anything

from said leases except out of the income which the

leased property was already bringing in, and with the

24

City reserving the right to put into the property further

investments from other sources than said income and

that under these circumstances said corporation was

in fact an agency of the City and the school board for

the continued maintenance and operation of the golf

course for the convenience of the citizens of Greens

boro."

The Superior Court denied the motion to set aside the

verdict without requiring the State to answer its allegations.

Appellants excepted and assigned the denial of the motion

as error on appeal. (Page 97 of printed Record below.) The

Supreme Court of North Carolina discusses this motion at

length in its Opinion in this case and concludes: "Defendants

were not, as a matter of right, entitled to have the verdict set

aside." (Appendix "A " herto attached, starting at Page 50.)

In its discussion of the motion to set aside the verdict the

Supreme Court of North Carolina said with reference to

the acts of playing golf in this case as having been before

the Federal Courts: " It would appear from the opinion that

the entry involved in this case was one incident on which

plaintiffs there relied to support their assertion of unlawful

discrimination, but it is manifest from the opinion that that

was not all of the evidence which Judge Hayes had." (Em

phasis added.)

Equal Protection Question Besides Racial Exclusion

In their motion to set aside the verdict appellants said

(Page 93 of printed Record below): "Defendants respectfully

suggest to the Court that to permit this verdict to stand under

these circumstances would violate the rights of these defend

ants under the Constitution and laws of the United States,

including the due process and equal protection clauses of the

14th Amendment."

Clyde Bass, assistant pro at the golf course when appel

lants sought to play, testified as to what he told appellants

(Page 40 of printed Record below): " I told them it was a

private club for members and invited guests only." He also

testified (Page 41 of printed Record below): "To my knowledge,

no Negroes have ever played at Gillesipe Park Golf Course

25

before this date. Some Negroes have presented themselves

before this date to play, but none have played to my knowl

edge."

Appellants alleged in their motion to set aside the verdict,

and the State did not answer to deny the allegations, that

the Jurors in this case, "in their answers to questions touching

their qualifications," in the cases of those who had played on

Gillespie Park Golf Course, "stated very frankly and freely

in open court that they had played on this course without

any requirements except the payment of greens fees."

The by-laws of the golf corporation said the following of

membership in the corporation (Page 70 of printed Record

below): "Membership in this corporation is restricted to mem

bers who are approved by the Board of Directors for member

ship in this Club."

Said by-laws said the following as to who was eligible to

play on this golf course (Page 70 of printed Record below):

"The golf course and its facilities shall be used oniy by mem

bers, their invited guests, members in good standing of other

golf clubs, members of the Carolina Golf Association, pupils

of the Professional and his invited guests."

John R. Hughes, president of the golf corporation, testified

(Pages 74, 75 of the printed Record below): "W e operated

completely on our own. The City had nothing to do with it."

"Those persons allowed to play were members of Gillespie

Park Golf Club, Inc., and their invited guests and members

in good standing with other clubs that were members of the

Carolina Golf Association."

One or more of appellants were members of a golf club

which was not a member of the Carolina Golf Association.

(Page 50 of printed Record below).

The Superior Court denied the motion to set aside the

verdict and appellants took exception. (Page 97 of printed

Record below). The Supreme Court of North Carolina affirmed

and found no error. (Appendix "A " attached hereto, Page

53.)

26

Judicial Notice of 14th Amendment as Construed by

Federal Decisions

Appellants contended in their motions to quash and to

set aside the verdict and by proper assignments on appeal

that it was the duty of the State Courts under the Supremacy

Clause (Art. 6, CL 2) of the Constitution of the United States

to notice and to enforce the Federal Court decisions declaring

the rights of appellants with respect to the identical acts

charged to be a criminal trespass in this case. (Pages 28, 91

of printed Record below). Appellants also alleged verbatim in

the motion to set aside the verdict the Declaratory Judgment

of the United States District Court covering said identical acts.

(Page 92 of printed Record below).

The Supreme Court of North Carolina held that the State

Courts would take judicial notice of the Federal Court's pub

lished Opinion, but that "Since the court was not required to

take judicial notice of the judgment" in the Federal Court,

"we are not called upon to determine the effect which should

have been given if offered in evidence." (Appendix "A "

attached hereto, Page 52.)

Raising Question of Double Jeopardy

In their motions to quash and to set aside the verdict

appellants alleged that they had been subjected to double

jeopardy in violation of the 14th Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States. The motions were overruled and

the Supreme Court of North Carolina said in its Opinion:

" It is manifest that there is here no double jeopardy." (Appen

dix "A " attached hereto, Page 44.)

The successive criminal proceedings covering the identical

acts charged to violate Section 14-134 of the General Statutes

of North Carolina (1953) are set forth above under this State

ment of the Case on Pages 8-10.

In the belief that this Court w ill take judicial notice of

the proceedings in the Federal Court to aid in determining

whether or not this Court has jurisdiction in this case, ap

pellants have attached hereto as Appendix "E " , Appendix

"F ", and Appendix "G ", the Findings of Fact, the Conclu

27

sions of Law, and the Decree and Injunction of the United

States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina.

(e) SUBSTA N TIA LTY OF TH E FEDERAL Q UESTIO N S

Th is is the first time since the desegregation decisions of

this Court that any state, so far as known to appellants, has

undertaken to make a crime out of the exercise of "constitu

tional rights" which have been duly declared to exist by

the Federal Courts. Months before the warrants were drawn

in this case, charging to be a criminal trespass the acts

of appellants in playing golf on the Municipal Gillespie Park

Golf Course, the United States District Court for the Middle

District of North Carolina had issued its Declaratory Judgment

declaring that those identical acts of playing golf constituted

the "constitutional rights" of appellants and further declaring

that interference with those "constitutional rights" by the

prosecuting witnesses in this case was "un law fully" done;

and also before said warrants were drawn said Declaratory

Judgment had been duly affirmed by the Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit and had become final. The State

agencies, namely, City of Greensboro, Greensboro City Board

of Education, and Gillespie Park Golf Club, Inc., were the de

fendants against whom said Declaratory Judgment was issued,

the Federal District Court having found in Finding of Fact No.

30, quoted verbatim by appellants in their motion to set aside

the verdict and not denied by the State, that the said golf

"corporation v/as in fact an agency of the City and the

school board for the continued maintenance and operation

of the golf course for the convenience of the citizens of

Greensboro." (See Page 25 above.)

The State in this case seeks to reverse what the Federal

Court has declared under the Constitution of the United States

to be the "constitutional rights" of appellants, and to make

unlawful under state law what the Federal Courts have held

to be lawful under the Federal Constitution.

Cases on All-Fours on Question of Jurisdiction

On the question of jurisdiction, appellants believe that

Marsh v Alabama, supra, is as near a case like the instant

case as it is ordinarily possible for two cases to be.

28

In Marsh the defendants were arrested, tried and con

victed for an alleged trespass under Sec. 426, Title 14, Ala

bama Code 1940, which statute is entitled "Trespass after

warning," and which is in substance practically identical with

Sec. 14-134 of the General Statutes of North Carolina (1953)

as construed in the instant case.

The land involved in Marsh was a company-owned town,

and the alleged trespass was remaining on a street in that

town and distributing literature after being ordered to leave.

Defendant having claimed rights under the First and Four

teenth Amendments of the Constitution of the United States,

this Court entertained an appeal from the Supreme Court of

Alabama, which sustained the conviction and sentence of de

fendant.

In this case the golf course involved was owned by the

City of Greensboro and the Greensboro City Board of Edu

cation, but was operated by Gillespie Park Golf Club, Inc.,

a North Carolina corporation which the Federal Courts de

termined to be "an agency of the City and the school board."

(See Page 25 above.) Appellants were arrested, tried and

convicted under said North Carolina trespass statute for play

ing golf on this golf course, where they claimed they had a

Federal constitutional right to be, this right having been estab

lished by Declaratory Judgment of the Federal Courts at the

time the warrants in this case were drawn. (See Pages 10-12

and 20 above.)

The Supreme Court of North Carolina having sustained

the judgment of conviction and sentence of appellants, it

would seem that the jurisdiction of this Court on appeal would

be clearly established by Marsh v Alabama. In that case, Mr.

Justice Black said this for the Court:

"In our view the circumstance that the property

rights to the premises where the deprivation of liberty,

here involved, took place, were held by others than

the public, is not sufficient to justify the State's permit

ting a corporation to govern a community of citizens

so as to restrict their fundamental liberties and the

29

enforcement of such restraint by the application of a

state statute." (326 US at Page 509)

Mr. Justice Frankfurter concurring said:

"And sim ilarly the technical distinctions on which a

finding of 'trespass' so often depends are too tenuous

to control decision regarding the scope of vital liber

ties guaranteed by the Constitution." (326 US at Page

511)

In the same vein of the principles of Marsh v Alabama, so

far as the question of jurisdiction is concerned, is the case of

Niemotko v Maryland, supra, which involved use of a state

park without a permit, and the arrest, tria l, conviction and

sentence of defendants for such use under a Maryland dis

orderly conduct statute. From a final judgment sustaining the

conviction and sentence, this Court entertained an appeal from

the highest Maryland court.

Effect of Supremacy Clause on Section 14-134

In Railway Employees' Department etc. v Flanson, supra,

this Court said: "A union agreement made pursuant to the

Railway Labor Act has, therefore, the imprimatur of the

federal law upon it and by force of the Supremacy Clause

of Article VI of the Constitution, could not be made illegal nor

vitiated by any provisions of the laws of a state."

Likewise, appellants contend that, at the time the warrants

issued upon which appellants were arrested and tried and

sentenced in this case, the identical acts of playing golf on

the Municipal Gillespie Park Golf Course, which the State

charges to be a crime, bore "the imprimatur" of the 14th

Amendment as interpreted by the Federal Courts, and there

fore "could not be made illegal" by Section 14-134 of the

General Statutes of North Carolina, and that said statute

must give way as unconstitutional, as it thus collides with

the Federal Constitution.

Other cases sustaining the jurisdiction of this Court, where

state law collides with Federal law, are: Franklin National

Bank v New York and Public Utilities Commission of California

v United States, both supra.

30

Judicial Notice.—Appellants take the view that Federal

Court proceedings and judgments construing the Con-

stution and laws of the United States are not just ordinary

judgments, but that they become an integral part of the

Federal Constitution and laws which they construe. Appellants

believe that when the Supremacy Clause says that "the Judges

in every State shall be bound" by the Constitution and laws

of the United States, it means to include the interpretation

placed upon them by the Federal Courts.

In Smith v O'Grady, Warden, supra, this Court said of

the Federal Constitution: "That Constitution is the supreme

law of the land, and 'upon the state courts, equally with

the courts of the Union, rests the obligation to guard and

enforce every right secured by that Constitution.'" The State

Court in this case could not know its duty without looking

at all parts of the Federal decisions which appellants called

to their attention as establishing "constitutional rights" in

appellants to perform the acts of golf playing which the

State charges to be a crime in this case.

In L illy v Grand Trunk Western Ry Co, supra, the Supreme

Court of Illinois declined to take judicial notice of a rule of

the Interstate Commerce Commission under an Act of Congress.

This Court reversed, saying: "Adopted in the exercise of the

Commission's authority, Rule 153 acquires the force of law

and becomes an integral part of the Act . . . , to be judicially

noticed."

Likewise, in this case appellants believe that the decisions

of the Federal Courts declaring to be the "constitutional rights"

of appellants the identical acts of playing golf which the

State charges to be a crime, became an integral part of the

14th Amendment in this case, "to be judicially noticed."

In Brown v Board of Education, supra, this Court said:

"Th is Court takes judicial notice of a fourth case, which

is pending in the United States Court of Appeals for the

District of Columbia Circuit, Bolling et al. v. Sharpe et al.,

No. 11,018 on that court's docket. In that case, the appellants

challenge the appellees' refusal to admit certain Negro ap

pellants to a segregated white school in the District of Colum-

31

bid; they allege that appellees have taken such action pur

suant to certain Acts of Congress; they allege that such action

is a violation of the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution."

Appellants believe that the principles upon which this

Court took judicial notice even of allegations in the pleadings

in said Brown case would, when supplemented by the Supre-

mancy Clause of the Constitution of the United States, require

the State Courts in this case not only to take judicial notice

of but also to give effect to the proceedings and decisions of

the Federal Courts, determining Federal "constitutional rights"

and involving the identical acts of playing golf on the public

Municipal Gillespie Park Golf Course which are involved in

this criminal trespass prosecution; and that all of these matters

raise most substantial Federal questions which give this Court

jurisdiction to entertain this appeal, and which only this Court

can finally resolve.

Little Rock Case (Aaron v Cooper, _____US_____ , Decided

September 29, 1958). In this latest decision of this Court

touching the reach of the judgments and decisions of the

Federal Courts when intepreting or establishing "constitutional

rights" under the Constitution of the United States, it was

stated by Mr. Chief Justice Warren for a unanimous Court:

"Article VI of the Constitution makes the Constitution the

'supreme law of the land.' In 1803, Chief Justice Marshall,

speaking for a unanimous court, referring to the Constitution

as 'the fundamental and paramount law of the nation,' de

clared in the notable case of Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch

137, 177, that 'it is emphatically the province and duty of

the judicial department to say what the law is.' Th is decision

declared the basic principle that the Federal judiciary is

supreme in the exposition of the law of the Constitution, and

that principle has ever since been respected by this court

and the country as a permanent and indispensable feature

of our constitutional system."

"Chief Justice Marshal! spoke for a unanimous court in

saying that: 'If the Legislatures of the several states may, at

w ill, annul the judgments of the courts of the United States,

and destroy the rights acquired under those judgments, the

Constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery . . .' United States

v. Peters, 5 Cranch 1 15, 136." (Emphasis Added.)

32

Pleadings Which Assert Federal Rights

Appellants state above verbatim (Pages 17-19, 20-25) alle

gations in their motions to quash and to set aside the verdict,

asserting the Federal rights which they claim have been de

nied or infringed in this case. Since the State did not in any

way deny these allegations, they must be accepted as true.

Tomkins v Missouri, supra.

As to the jurisdiction and province of this Court on appeal

from a state court where Federal constitutional rights have

been set forth in a pleading, this Court said in Staub v City

of Baxley, supra:

"A t the threshold, appellee urges that this appeal

be dismissed because, it argues, the decision of the

Court of Appeals was based upon state procedural

grounds and thus rests upon an adequate nonfederai

basis, and that we are therefore without jurisdiction to

entertain it. Hence, the question is whether that basis

was an adequate one in the circumstances of this case.

'Whether a pleading sets up a sufficient right of action

or defense, grounded on the Constitution or a law of

the United States, is necessarily a question of federal

law; and where a case coming from a state court pre

sents that question, this Court must determine for itself

the sufficiency of the allegations displaying the right

or defense, and is not concluded by the view taken of

them by the state court/ First Nat. Bank v Anderson

269 US 341, 346, 70 L ed 295, 302, 46 S Ct 135, and

cases cited. See also Schuylkill Trust Co. v Pennsyl

vania, 296 US 113, 122, 123, 80 L ed 9 1 ,9 8 , 56 S Ct

31, and Lovell v G riffin, 303 US 444, 450, 82 L ed 949,

952, 58 S Ct 666. As Mr. Justice Holmes said in Davis

v Wechsler, 263 US 22, 24, 68 L ed 143, 145, 44 S Ct

13, 'Whatever springes the State may set for those

who are endeavoring to assert rights that the State

confers, the assertion of federal rights, when plainly

and reasonably made, is not to be defeated under the

name of local practice.' Whether the constitutional

rights asserted by the appellant were '. . . given due

recognition by the [Court of Appeals] is a question as

33

to which the [appellant is] entitled to invoke our judg

ment, and this [she has] done in the appropriate way.