Low Income Housing Project Eviction Procedures Taken to High Court for Review

Press Release

October 21, 1966

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 4. Low Income Housing Project Eviction Procedures Taken to High Court for Review, 1966. 84e7f844-b792-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e35df688-8872-4975-960d-efc54b96d684/low-income-housing-project-eviction-procedures-taken-to-high-court-for-review. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

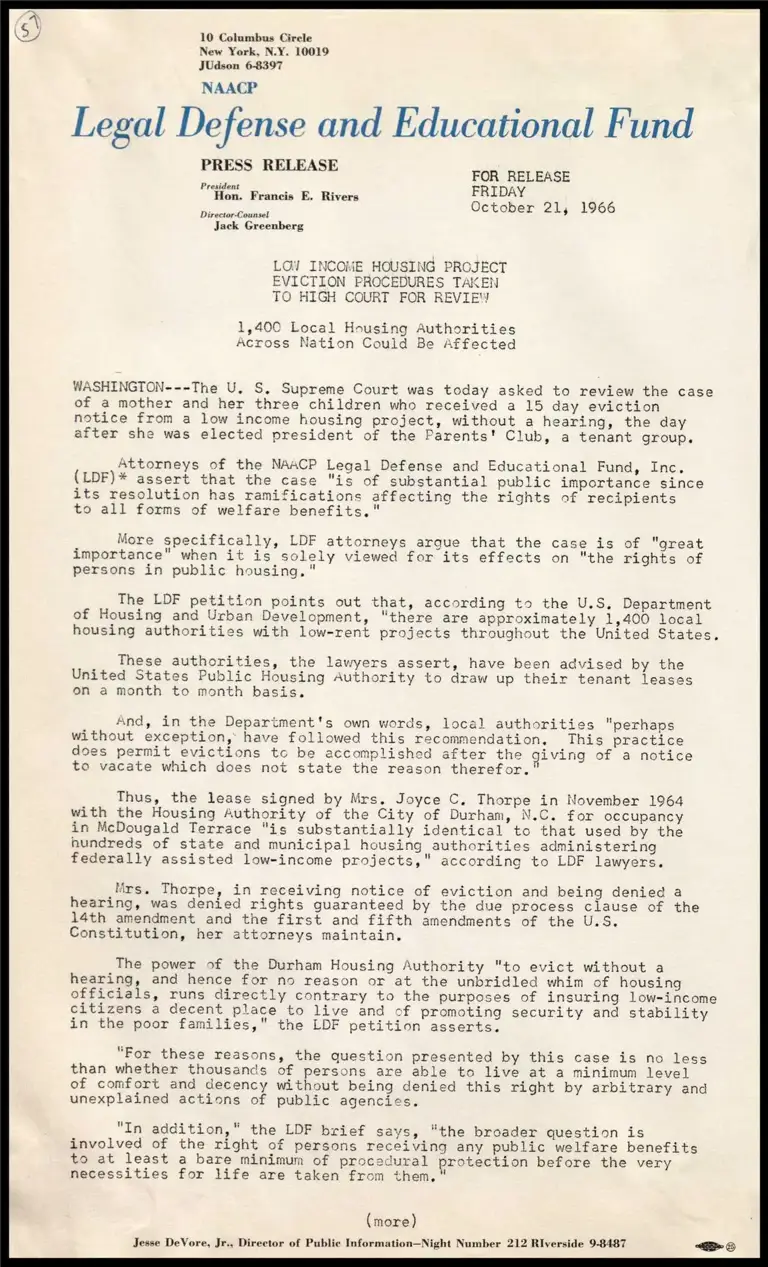

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

JUdson 6-8397

NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund

PRESS RELEASE FOR RELEASE

President " x 2 FRIDAY

ae 3 E. Ri

ao October 21, 1966

Jack Greenberg

LOW INCOME HOUSING PROJECT

EVICTION PROCEDURES TAKEN

TO HIGH COURT FOR REVIEW

1,400 Local Housing Authorities

Across Nation Could Be Affected

WASHINGTON---The U, S. Supreme Court was today asked to review the case

of a mother and her three children who received a 15 day eviction

notice from a low income housing project, without a hearing, the day

after she was elected president of the Parents! Club, a tenant group.

Attorneys of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

* assert that the case “is of substantial public importance since

its resolution has ramifications affecting the rights of recipients

to all forms of welfare benefits."

More specifically, LDF attorneys argue that the case is of "great

importance" when it is solely viewed for its effects on "the rights of

persons in public housing."

The LDF petition points out that, according to the U.S. Department

of Housing and Urban Development, "there are approximately 1,400 local

housing authorities with low-rent projects throughout the United States.

These authorities, the lawyers assert, have been advised by the

United States Public Housing Authority to draw up their tenant leases

on a month to month basis.

And, in the Department's own words, local authorities "perhaps

without exception, have followed this recommendation, This practice

does permit evictions to be accomplished after the giving of a notice

to vacate which does not state the reason therefor."

Thus, the lease signed by Mrs, Joyce C. Thorpe in November 1964

with the Housing Authority of the City of Durham, N.C. for occupancy

in McDougald Terrace “is substantially identical to that used by the

hundreds of state and municipal housing authorities administering

federally assisted low-income projects, according to LDF lawyers.

Mrs. Thorpe, in receiving notice of eviction and being denied a

hearing, was denied rights guaranteed by the due process clause of the

14th amendment and the first and fifth amendments of the U.S.

Constitution, her attorneys maintain.

The power of the Durham Housing Authority "to evict without a

hearing, and hence for no reason or at the unbridled whim of housing

officials, runs directly contrary to the purposes of insuring low-income

citizens a decent place to live and of promoting security and stability

in the poor families," the LDF petition asserts.

“For these reasons, the question presented by this case is no less

than whether thousands of persons are able to live at a minimum level

of comfort and decency without being denied this right by arbitrary and

unexplained actions of public agencies.

"In addition," the LDF brief says, “the broader question is

involved of the right of persons receiving any public welfare benefits

to at least a bare minimum of procedural protection before the very

necessities for life are taken from them."

(more)

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Public Information—Night Number 212 Riverside 9-8487 es

LOW INCOME HOUSING PROJECT -2- October 21, 1966

EVICTION PROCEDURES TAKEN

TO HIGH CQURT FOR REVIEVW!

Mrs, Thorpe and her children are still tenants in the Durham

housing project, under order of the North Carolina Supreme Court pre-

venting their eviction until the U.S. Supreme Court passes on their

petition for writ of certiorari.

This is one of the first cases in the LDF's new program of liti-

gation to protect and establish the rights of poor people. The LDF

is acting, in this case, in cooperation with Center for Social Welfare

Policy and Law of Columbia University.

LDF attorneys filing the petition include Director-Counsel Jack

Greenberg, James M, Nabrit,III, Charles Stephen Ralston, Michael

Meltsner, Charles H. Jones, Jr., and Sheila Rush Jones of the New York

office, and M, C, Burt of Durham,

They are joined by attorneys Edward V, Sparer, Martin Garbus, and

Howard Thorkelson of the Center for Social Welfare Policy and Law of

Columbia University.

=30-

* This is a separate, independent organization from the NAACP, The

names are similar because the Legal Defense Fund was established as a

different organization by the NAACP and through the years has gained

complete autonomy.