James v. Beaufort County Board of Education Joint Supplemental Brief for All Plaintiffs

Public Court Documents

August 28, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. James v. Beaufort County Board of Education Joint Supplemental Brief for All Plaintiffs, 1972. b7cbb410-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e38d3441-9dd6-4941-bf90-bf6abcab503c/james-v-beaufort-county-board-of-education-joint-supplemental-brief-for-all-plaintiffs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

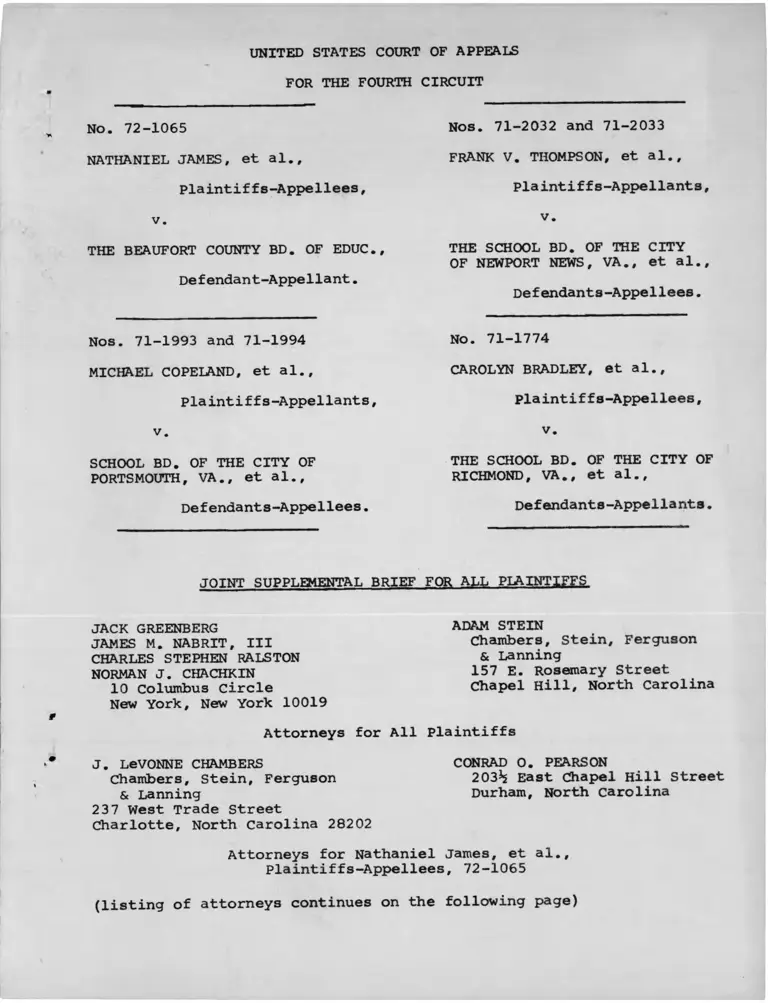

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-1065 Nos. 71-2032 and 71-2033

NATHANIEL JAMES, et al., FRANK V. THOMPSON, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellees, Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V. V.

THE BEAUFORT COUNTY BD. OF EDUC.,

Defendant-Appellant.

THE SCHOOL BD. OF THE CITY

OF NEWPORT NEWS, VA., et al..

Defendants-Appellees.

Nos. 71-1993 and 71-1994 No. 71-1774

MICHAEL COPELAND, et al.. CAROLYN BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants, Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v. V.

SCHOOL BD. OF THE CITY OF

PORTSMOUTH, VA., et al..

THE SCHOOL BD. OF THE CITY OF

RICHMOND, VA., et al.,

Defendants-Appellees. Defendants-Appellants.

JOINT SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR ALL PLAINTIFFS

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ADAM STEIN

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson

& Lanning

157 E. Rosemary Street

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Attorneys for All plaintiffs

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson

& Lanning

237 West Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

CONRAD 0. PEARSON

203*5 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Nathaniel James, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees, 72-1065

(listing of attorneys continues on the following page)

S. W. TUCKER JAMES A. OVERTON

HENRY L. MARSH, III 623 Effingham Street

JAMES W. BENTON, JR. Portsmouth, Virginia 23704Hill, Tucker & Marsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Michael Copeland, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants, Nos. 71-1993, 71-1994

S.W. TUCKER PHILIP S. WALKER

HENRY L. MARSH, III 1715 25th Street

JAMES W. BENTON, JR. Newport News, Va. 23607

Hill, Tucker & Marsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Frank V. Thompson, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants, Nos. 71-2032, 71-2033

LOUIS R. LUCAS JAMES R. OLPHIN

525 Commerce Title Bldg. 214 East Clay Street

Memphis, Tennessee 38103 Richmond, Virginia 23219

M. RALPH PAGE

420 North First St.

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Carolyn Bradley, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees, No. 71-1774

Page

ISSUES--------------------------------------------------------- ±

STATEMENT ----------------------------------------------------- 2

ARGUMENT------------------------------------------------------ --

I. LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF § 7 1 8 --------------------------H

II. SECTION 718 MUST BE APPLIED TO PENDING

SCHOOL DESEGREGATION CASES -------------------------- 14

H I . SECTION 718 REQUIRES THE APPLICATION OF THE

"PRIVATE ATTORNEY-GENERAL" STANDARD OF

NEWMAN V. PIGGIE PARK ENTERPRISES TO THESE

c a s e s ----~---------------- ______ 21

IV. THESE PRINCIPLES REQUIRE HOLDINGS THAT COUNSEL

FEES BE ASSESSED IN EACH OF THE PRESENT CASES----- 25

CONCLUSION---------------------------------------------------- - -

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE --------------------------------------- 28

TABLE OF CASES

Boomer v. Beaufort County Bd. of Ed., 294 F. Supp.

179 (E.D.N.C. 1968) ---------------------------------------- 3

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 345 F.2d 310

(4th Cir. 1965) ------------------------------------------- 4# 9

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 53 F.R.D. 28

(D.C. Va. 1971) ------------------------------------------ 4f 9

Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943

(4th Cir. 1972) -------------------------------------- 4 , 7, 10

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d

1377 (4th Cir. 1972) ------------------------------------- 3# 5

Buckner v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 339 F. Supp.

1108 (D.C. Ala. 1972 ) ------------------------------------- 5

Carpenter v. Wabash Railway Co., 309 U.S. 23 (1940) -------- 16

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S.402 (1971) ----------------------------------------------- i6, 17

Clark v. American Marine Corp., 320 F. Supp. 709 (E.D.

La. 1970) aff'd, 437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1971) ------------ 22

INDEX

11

Page

Glove v. Housing Authority of City of Bessemer, 444 F.2d

158 (5th Cir. 1971) ------------------------------------

Green v. County School Board of New Kent, 391 U.S. 430

(1968) ------------------------------------------------------

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 (1959) ----------------------

Greene v. United States, 376 U.S. 149 (1964)------------- 19,

Hall v. Beals, 396 U.S. 45, 48 (1969) -----------------------

Hall v. St. Helena parish School Board, 424 F.2d 320, 322

(5th Cir. 1970) ---------------------------------------------

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964) -------------

Johnson v. United States, 434 F.2d 340 (8th Cir. 1970)------

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 86

(4th Cir. 1971) ---------------------------------- 5, 22, 23,

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d 143

(5th Cir. 1971) -------------------------------------------5,

6

19

20

16

16

17

16

24

22

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 244 F. Supp. 353

(W.D. Tenn. 1965) ------------------------------------------- 4

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400

(1968)---------------------------------------- 4, 21, 22, 24, 25

Robinson v. Lorillard corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971)--- 5

Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank, 307 U.S. 161 (1939)--------20

Swann v. charlotte-Mecklenberg Bd. of Ed., 402 U.S. 1

(1971) ----------------------------------------------------- - 7

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham, 393 U.S. 268

(1969) -------------------------------------------15, 16, 18, 19

United States v. Board of Ed. of Baldwin Co., Ga.,

423 F.2d 1013 (5th Cir. 1970) ------------------------------ 16

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch 103

(1801) ----------------------------------------- 15, 16, 18, 19

Vandenbark v. Owens-Illinois Glass Co., 311 U.S. 538

(1941) ------------------------------------------------------ 16

Ziffrin v. united States, 318 U.S. 73 (1943) ---------------- 16

STATUTES

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 8 1 ------------------------------------------------5

42 U.S.C. § 1982 ------------------------------------------------5

Title II, Civil Rights Act of 1964 --------------------------- 17

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964 ----------------------- 5, 18

§ 204(b), Civil Rights Act of 1964 ----------------------- 21, 22

§ 706, Civil Rights Act of 1964 ---------------------- 5, 21, 22

S.659, Education Amendments of 1 9 7 1 -------------------------- 13

§ 718, Education Amendments of 1972 ---------------------- passim

S.1557, Emergency School Aid and Quality Integrated

Education Act of 1971, § 1 1 ----------------------- 11, 12, 18

§ 812, Fair Housing Act of 1968 ----------------------- 5, 21, 22

Fed. Rules Civ. Proc., 54(d) ---------------------------------- 20

OTHER AUTHORITIES

House and Senate Conference Report No. 798, 92d Cong.

2nd Sess. ------------------------------------------------- 13

117 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. April 21, 1971) ------------------ 12

117 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. April 22, 1971) ------ 13, 17, 23, 24

117 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. April 23, 1971) ----------- 13, 17, 23

117 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. April 26, 1971) -------------------- 13

Senate Rep. No. 92-61, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. ------------- 11, 12

Senate Rep. No. 92-604, 92d Cong., 2nd Sess. ----------------13

U.S. Code Congressional & Administrative News, 1972,

vol. 6 ----------------------------------------------13, 14, 17

Ill

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-1065

NATHANIEL JAMES, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

THE BEAUFORT COUNTY BD. OF EDUC.,

Defendant-Appellant.

Nos. 71-1993 and 71-1994

MICHAEL COPELAND, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

SCHOOL BD. OF THE CITY OF

PORTSMOUTH, VA., et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Nos. 71-2032 and 71-2033

FRANK V. THOMPSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

THE SCHOOL BD. OF THE CITY

OF NEWPORT NEWS, VA., et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

No. 71-1774

CAROLYN BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

THE SCHOOL BD. OF THE CITY OF

RICHMOND, VA., et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

BRIEF FOR ALL PLAINTIFFS

ISSUES

On August 1, 1972, this Court entered an order requesting

further briefing in the above cases. The order said, in pertinent

part:

On June 23, 1972, the President signed

into law the Emergency School Aid Act.

Section 718 of this Act is directed to the

problem of attorneys1 fees in school

desegregation cases, a question involved in

each of the above cases. Since these cases

were all briefed and argued before the

enactment of § 718, the parties have not

had an opportunity to present fully their

views regarding the possible application

of this provision to their cases. Accord

ingly, the Court has decided to convene

en banc for the consideration of this issue

in’ each of these cases. The parties are

directed to file briefs, addressing this

question, giving specific consideration to

the legislative history of § 718, including

whether retroactive application was intended

by the congress and if so, to what extent.

This joint brief filed in behalf of the black plaintiffs in each

of these cases addresses the questions posed by the Court.

STATEMENT

These four cases arose out of claims by black persons that

school authorities were engaging in racial discrimination in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. In each case the plain

tiffs established constitutional violations and requested that

their recoverable costs include an award of reasonable counsel fees.

In James and Bradley the district court awarded fees and the

school officials appealed. The district court in Thompson also

awarded fees from which the defendants appealed. The plaintiffs

1/ The parties filing this brief are: Nathaniel James, et al.,

tlie plaintiffs-appellees in 72-1065? Michael Copeland, et al.,

the plaintiffs-appellants in 71-1993 and the plaintiffs-appellees

in 71-1994; Frank V. Thompson, et al., the plaintiffs-appellants

in 71-2032 and plaintiffs-appellees in 71-2033; and Carolyn Bradley,

et al., the plaintiffs-appellees in No. 71-1774.

2

inadequate

appealed also, challenging the /coverage of the award. in Copeland

the trial court declined to include fees as a part of costs and

the plaintiffs appealed.

A brief summary of the four cases follows.

James - No. 72-1065.

Suit was filed on April 18, 1969 by Nathaniel James, Roy

Simpson and the North Carolina Teachers Association against the

2/Beaufort County, North Carolina Board of Education. James,

a principal, and Simpson, a teacher, claimed that they had been

dismissed from their positions because of their race. The

North Carolina Teachers Association (NCTA) supported their claims

and further asserted that the Board had systematically decimated

the ranks of black educators following an order fully to desegregate

its school system for the 1968-69 school year.

The district court found in favor of James and the NCTA;

it found against Simpson. The court ordered that James be

reinstated with back pay and directed that remedial action be

2/ Plaintiffs brought suit under Title 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and

§ 1981. See Brown v. Gaston County Dyeinq Machine Co.. 457 F.2d

1377 (4th Cir. 1972). --- ------------

3/ Boomer v. Beaufort County Board of Education. 294 F. Supp.

179 (E.D.N.C. 1968); stay denied, F. Supp. (al55); stay

granted, ____ F.2d ____ (4th Cir. August 27, 1968") (al60) ; stay

vacated, ____ u.S. _____ (August 30, 1968) (per Mr. Justice Black)(al61); appeal withdrawn.

3

taken to counteract the discriminatory employment practices which

had resulted in the drastic reduction of black teachers and principals

immediately prior to the 1968-69 school year. The court also

directed that counsel fees be taxed as part of the costs to be

recovered by plaintiffs Simpson and the NCTA. The School Board

appealed from all portions of the orders of the district court.

The plaintiffs have previously urged affirmance of the

counsel fee award on the following grounds. First, fees should

be awarded to prevailing plaintiffs in cases involving racial

discrimination in public education because they act as private

attorneys general vindicating important national policy. Newman

v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968); Bradley v.

School Board of the City of Richmond, 53 F.R.D. 28 (D.C. Va. 1971).

Second, the record supports the court's award because of

"the School Board's unreasonable obdurate obstinacy." Bradley v.

The School Board of the City of Richmond. 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir.

1965).

Third, fees were appropriately awarded because the trial

court found that the discrimination complained of was done in

violation of a previous court order. Monroe v. Board of

Commissioners, 244 F. Supp. 353 (W.D. Tenn. 1965).

Fourth, it was proper for the court to award fees because

plaintiffs had secured relief in the form of a "pecuniary benefit"

for themselves and other black educators. Brewer v. School Board of

the City of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943 (4th Cir. 1972).

4

Finally, fees are required because plaintiffs were successful

in asserting claims of employment discrimination under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981. Counsel fee standards for cases brought under Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 706, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5k,

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971), Robinson v.

Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971), apply fully to

employment discrimination cases brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.. 457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir.

1972)* Buckner v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.. 339 F. Supp. 1108

(D.C. Ala. 1972). Fee awards in employment discrimination cases

under § 1981 has resulted from a process of construing the old

statute, under which the courts are to fashion appropriate remedies

±/"interstitially" with the new (Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964) which contains fairly detailed remedial provisions.

Indeed, including counsel fees as a part of the remedy in teacher

discrimination cases, as was done by the court below, merely

anticipated congressional action because the 1972 amendments to

Title VII repealed provisions which had previously exempted

educational institutions and public employers from coverage.

Therefore, the fee award in this case must be affirmed on the

basis of the amendments to Title VII adopted during the pendency

of this appeal for all of the reasons we show that § 718 is now

fully applicable.

4/ The Fifth circuit has construed 42 U.S.C. § 1982 "intersti-

tially" with the counsel fee provision of the Fair Housing Act of

1968, § 812, 42 U.S.C. § 3612(c) requiring an award for prevailing

plaintiffs absent special circumstances. Lee v. Southern Home Sites

Corp. . 444 F.2d 143 (5th Cir. 1971). — -------------'-----

5

Copeland - Nos. 71-1993, 71-1994

Black children and their parents commenced this action in

April, 1965, seeking the elimination of racial discrimination in

the public schools of the city of Portsmouth, Virginia.

Ihe school authorities responded to the suit by adopting

a freedom of choice plan. Thereafter the plaintiffs objected to

freedom of choice as being inadequate to eliminate segregation.

Following Green v. The County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968), the district court agreed that free choice

was insufficient and required a new plan. A zoning plan was then

approved by the court and again plaintiffs objected. During the

summer of 1971, after the Supreme Court's decision in Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971),

further hearings were held which resulted in a rejection of the

neighborhood zoning plan then in effect and a new plan. These

appeals followed.

On August 2, 1972, this Court decided the issues relating

to the desegregation plan which had been approved by the court.

The court reserved decision of plaintiffs' claim that they should

have been awarded counsel fees. The court has decided that the

failure of the plan to provide for free transportation was improper;

that the plan should be amended to include a "majority to minority"

transfer provision; that further inquiry should be made by the

district court to determine whether tests used to assign children

to two formerly black schools which are used as special schools

are "relevant, reliable and free of discrimination"; that the failure

6

to allow plaintiffs' expert a fee was not clearly erroneous; and

that the basic provisions of the desegregation plan required by

the district court, to which the defendants objected, were clearly

warranted.

Ibe plaintiffs have previously urged that the district court

should have awarded fees because they had acted as "private

attorneys general," because of the School Board's obstinacy and

because they had sought and were entitled to a ruling that the

schoolchildren must be provided free transportation.

Since the August 2 decision holds that the plaintiffs were

entitled to an order requiring free transportation for pupils

assigned outside of their neighborhoods, plaintiffs are therefore

entitled to counsel fees. Brewer v. The School Board of the city

of Norfolk, supra .

Thompson - Nos. 71-2032, 71-2033

Suit was commenced in this school desegregation case on

July 23, 1970 seeking elimination of segregation in the public

schools operated by the School Board of the City of Newport News,

Virginia. The Board was then assigning students under a freedom

of choice plan. Proceedings in the case were stayed during the

pendency of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education in

the Supreme Court. After that decision, hearings were held in

August, 1971, and a desegregation order was entered. The court

also awarded counsel fees to plaintiffs in the amount of $750.00,

limiting the award to cover counsel's services in connection with

a hearing on August 12, 1971.

7

The School Board appealed from the desegregation order and

the counsel fee award. Plaintiffs also appealed, objecting to the

plan because it left all first and second graders in segregated

neighborhood schools and contending that the fee award should have

covered plaintiffs' attorneys services for the entire case.

This Court decided all issues except for counsel fees in

an opinion filed on August 2, 1972. Defendants' appeals were

disallowed. With respect to the first and second grades, the

case was "remanded to the District Court to consider any

alternate plans that may be presented by the plaintiffs and

others and to determine whether, on the basis of specific

findings of fact, there is any practical or feasible alternative,

promising greater racial balance in these two grades, to the

neighborhood plan proposed by the school district, and, if there

is, to amend the desegregation plan accordingly."

As to plaintiffs' attorneys' fee claim, the Court said:

It would seem inappropriate, however, to

consider this claim until the District Court

has resolved the issues, which on remand, it

is hereby mandated to consider. In connection

with its final order on those issues, it may

make such allowances of attorney's fees as

it finds proper under the terms of Section

718, Higher Education Act of 1972.

Plaintiffs have urged that they are entitled to counsel fees

for all of the proceedings below because they acted as private

attorneys general and because the Board was obstinate in its

refusal to adopt a constitutional desegregation plan.

8

This is an appeal by the School Board of the City of Richmond,

Virginia, from an order entered by the district court on May 26,

1971 awarding the black plaintiffs counsel fees for the period of

school desegregation litigation from March, 1970 until February,

1971. The litigation for which fees were awarded involved the

Richmond, Virginia public schools; it did not involve any of the

litigation leading to the "metropolitan desegregation" order

which was reversed by this Court on June 5, 1972. (Nos. 72-1058,

1059, 1060, 1150.) The protracted and complex proceedings for which

fees were awarded are described in plaintiffs-appellees1 main brief.

Plaintiffs had renewed their request that counsel fees be

taxed as a part of their recoverable costs following the entry

of the order on April 5, 1971 directing the implementation of a

specific plan. Counsel fees were then separately considered by

the district court. The propriety of the award is the only matter

at issue in this appeal.

The court below held that fees should be awarded on two

grounds. It held that in school desegregation cases complete

relief requires such an award to prevailing private plaintiffs.

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 53 F.R.D. 28, 41 (E.D. Va.

1971). It also awarded fees in its traditional equitable discretion

because of the defendants1 resistance to constitutional mandates

during the course of the litigation. In January, 1972 plaintiffs

Bradley - No. 71-1774

9

filed a detailed brief in this Court urging affirmance of the order

on both grounds.

Following the initial argument, they filed a supplemental brief

referring to certain matters mentioned in argument but not pre

viously briefed and discussing the applicability of Brewer v.

School Board of the City of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943 (4th Cir. 1972),

6/

which had been decided on the day of argument.

ARGUMENT

In summary, the position of the plaintiffs in these four

actions is: (1) § 718 of the Education Amendments of 1972, which

provides for the award of counsel fees to prevailing plaintiffs

1/

in school desegregation cases, must be applied to claims

for counsel fees at the appellate as well as the trial level; and

(2) § 718 enacts the "private attorney-general" standard applicable

in cases brought under Titles II and VII of the Civil Rights Act

6/ Brewer is also discussed in the plaintiffs' main briefs in

Copeland and Thompson.

7/ Section 718 states:

SEC. 718. Upon the entry of a final order by

a court of the United States against a local educa

tional agency, a State (or any agency thereof), or the

United States (or any agency thereof), for failure to

comply with any provision of this title or for

discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national

origin in violation of title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, or the fourteenth amendment to the Constitution

of the United States as they pertain to elementary and

secondary education, the court, in its discretion, upon

a finding that the proceedings were necessary to bring

about compliance, may allow the prevailing party, other

than the United States, a reasonable attorney's fee as

part of the costs.

10

of 1964 and Title VIII of the Housing Act of 1968. Therefore, this

Court should decide the issue of counsel fees in these cases by

reference to § 718, and affirm the awards in Nos. 72-1065 and 71-

1774, and reverse the denial in Nos. 71-1993 and 71-1994. In Nos.

71-2032, 71-2033, the partial award should be affirmed and the

case remanded for award of the full counsel fees requested.

Before discussing the reasons why § 718 is applicable to

the present cases, however, we will first set out in some detail

the history of the enactment of the section.

I

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF § 718

The provision for attorneys' fees in school desegregation

cases was first introduced in the Senate as § 11 of the Emergency

School Aid and Quality Integrated Education Act of 1971, S. 1557.

The bill was reported to the Senate floor in April of 1971, and

§ 11 was described in the report of the Senate Committee on Labor

and Public Welfare. Sen. Rep. No. 92-61, 92d Cong., 1st Sess.

The report, while not setting out the precise text of § 11, describes

it fully. Its provisions were substantially the same as those of

§ 718 as it finally passed, with two important exceptions.

First, payment of attorneys' fees in school cases was to be

made by the United States from a special fund established by the

Act. Second, the section provided that "reasonable counsel fees,

and costs not otherwise reimbursed for services rendered, and

costs incurred, after the date of enactment of the Act" were to be

11

awarded to a prevailing plaintiff. It should be noted that the

quoted language was omitted from § 718.

On April 21, 1971 Senator Dominick of Colorado introduced

an amendment to delete § 11 in its entirety from the bill. The

basis for the deletion was that it was not proper that the United

States should bear the costs of attorneys1 fees but rather that

such costs should be imposed on the school boards responsible for

the maintenance of unconstitutionally segregated school systems.

Senator Dominick's amendment passed. 117 Cong. Rec. S.5324-31

(daily ed. April 21, 1971).

On the next day. Senator Cook of Kentucky, who was also

opposed to § 11, introduced a new amendment identical to the

8/

8/ The description of § 11 in the Senate report is as follows:

This section states that upon the entry of a

final order by a court of the United States against

a local educational agency, a State (or any agency

thereof), or the Department of Health, Education,

and Welfare, for failure to comply with any provision

of the Act or of title I of the Elementary and

Secondary Education Act of 1965, or for discrimination

on the basis of race, color, or national origin in

violation of title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

or of the Fourteenth Article of amendment to the

Constitution of the United States as they pertain to

elementary and secondary education, such court shall,

upon a finding that the proceedings were necessary to

bring about compliance, award, from funds reserved

pursuant to section 3(b)(3), reasonable counsel fees,

and costs not otherwise reimbursed for services

rendered, and costs incurred, after the date of

enactment of the Act to the party obtaining such

order. In any case in which a party asserts a right

to be awarded fees and costs under section 11, the

United States shall be a party with respect to the

appropriateness of such award and the reasonableness

of counsel fees. The Commissioner is directed to

transfer all funds reserved pursuant to section 3 (b)

(3) to the Administration Office of the United States

Courts for the purpose of making payments of fees

awarded pursuant to section 11.

Senate Report No. 92-61, 92d Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 55-56.

12

present § 718, and after two days of debate that amendment was

passed. 117 Cong. Rec. S.5483-92 (daily ed. April 22, 1971) and

S.5534-39 (daily ed. April 23, 1971). The section as passed

became § 16 of S.1557, and S.1557 as a whole was passed on April 26,

1971, without any further debate of the attorneys' fees provision.

117 Cong. Rec. S.5742-47 (daily ed. April 26, 1971).

Subsequently, on August 6, 1971, the Senate passed a related

statute, S.659, the Education Amendments of 1971. See, U.S. Code2/Congressional and Administrative News, 1972, vol. 6, p. 2333.

Both Senate bills were then sent to the House. On November 5, 1971,

the House, in considering a parallel measure, H.R.7248, amended S.659.

The House struck everything after the enactment clause of the

Senate bill and substituted a new text based substantially on the

House bill and in effect combining provisions of S.1557 and S.659.

Ibid. In so amending the Senate bill the House omitted the attorneys1

10/

fees provision (Id., at 2406) without debate.

The amended Senate bill was then returned to the Senate with

request for a conference, which request was referred to the Senate

Committee on Labor and Public Welfare. However, the Committee,

instead of acceding to the request for a conference, reported

S.659 back to the Senate floor with amendments to the House

substitute. Those amendments re-included the counsel fee provision

of S.1557 in exactly the same form as it had originally passed the

9/ Sen. Rep. No. 92-604, 92d Cong., 2nd Sess., Report of the

Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare on the Message of the

House on S.659.

10/ Conference Report No. 798, 92d Cong., 2nd Sess.

13

Senate in April. Id. at 2333 and 2406. On March 1, 1972, the

Senate passed S.659 as reported to it by the Committee, and this

amended bill was then sent to conference. The Senate-House conference

made further amendments and reported the bill to both houses with

the continued inclusion of the attorneys' fees provision exactly

as passed by the Senate. Id. at 2406. The provision was now

§ 718 of the Education Amendments of 1972. The conference bill

was passed with no further debate on § 718 by the Senate on May 24,

1972 and by the House on June 8, 1972 (Id. at 2200), and was signed

into law by the President on June 23.

Thus, the only debate concerning § 718 that our research

has disclosed occurred in connection with its original passage

by the Senate in April of 1971. As noted above, there was no

debate in the House concerning its deletion when the House amended

S.659 and there was no further debate in the Senate or the House

with regard to the passage of the conference bill.

II

SECTION 718 MUST BE APPLIED TO

PENDING SCHOOL DESEGREGATION

CASES.

In its order of August 1, 1972, this Court refers at one

point to possible "retroactive application" of § 718. We will

discuss, infra, the extent to which the legislative history of

§ 718 casts light on the intention of Congress as to this matter.

Initially, however, we respectfully urge that in these cases, at

least, the issue posed by § 718 is not retroactivity in the technical

sense.

14

That is, the issue in these cases is whether, in deciding what

is the governing legal standard with regard to the award of attorneys'

fees in school desegregation cases, this Court should apply § 718

to orders that were entered by district courts prior to the enactment

of the section and which are presently on appeal. Plaintiffs'

contention is that these cases are clearly controlled by "the

general rule . . . that an appellate court must apply the law in

effect at the time it renders its decision." Thorpe v. Housing

Authority of Durham. 393 U.S. 268, 281 (1969). That is, where an

issue is before an appellate court concerning the propriety of a

lower court's decision, and there has been an intervening modi

fication of the substantive rule of law relating to the issue,

that modification is to govern whether "the change was constitutional,

10a/

statutory, or judicial." 393 U.S. at 282.

This rule has been applied in cases where the change in law

modifies the substantive rights of the parties so as either to

create or to destroy rights of recovery. Thus, in the leading case

in the area, United States v. Schooner Peggy. 5 U.S. (1 Cranch)

103 (1801), the question was who was entitled to possession of

a French merchant vessel seized as a prize. At the time of seizure

and the decision of the lower court the law was in favor of the

captor of the vessel. While a writ of error was pending in the

Supreme Court, however, a treaty was entered into which established

10a/ Retroactivity, as such, would only be an issue in a school case

that had been finally disposed of with a prior disposition of a claim

for attorneys' fees. Whether § 718 would apply in such a case is a

question that need not be reached in these cases.

15

the contrary result. The Court held, in language quoted in Thorpe:

[I]f subsequent to the judgment and before

the decision of the appellate court, a law

intervenes and positively changes the rule

which governs, the law must be obeyed. . . .

If the law be constitutional . . . I know of

no court which can contest its obligation.

5 U.S. (1 Cranch) at 110.

Similarly, in carpenter v. Wabash Railway Co., 309 U.S. 23

(1940) (also cited in Thorpe), pending disposition of a petition

for writ of certiorari, Congress modified the bankruptcy laws to

give equity receiverships in railroad corporations a preferred

status not theretofore enjoyed. The Court applied the statute, even

though it substantially modified the legal rights of creditors,

and reversed the lower court. See also, vandenbark v. Owens-Illinois

Glass Co., 311 U.S. 538 (1941) (intervening decision of state

court in diversity case creating new cause of action applied on

appeal from dismissal of case); ziffrin v. United States, 318 U.S.

73, 78 (1943); Hall v. Beals, 396 U.S. 45, 48 (1969) ("we review

the judgment below in light of the Colorado statute as it now stands,

11/not as it once did").

Thorpe further establishes that a stated intent by Congress

that § 718 apply to pending cases is not necessary. In Thorpe,

no such intent was expressed in the administrative regulation

11/ And see, united States v. Board of Education of Baldwin Co., Ga.,

423 F .2d 1013,1014 (5tVTcTr. 1970); Hall v. St. Helena parTsTTSchool

Board, 424 F.2d 320, 322 (5th Cir. 1970); Citizens To Preserve

Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402, 418-4T5 (1971); Johnson v.

United States, 434 F.2d 340, 343 (8th Cir. 1970); and Glove v.

Housing Authority of City of Bessemer, Ala., 444 F.2d T5§ [5th Cir.

1971).

16

involved, and the Court in no way intimated that such an expression

12/

was required. Indeed, its description of its holding as "the

general rule," strongly indicates that the contrary is required;

that is, if a new statute is not to apply to pending cases it must

affirmatively appear that such was the intent of Congress. And it

is clear that that is the rule in the case of legislation that

alters the law as to the criminality of conduct. Thus, in Hamm v.

City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964), the Court held that the

passage of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made non

criminal acts that were trespass under state law in the absence of

an expression of Congressional intent to the contrary.

Turning to the legislative history of § 718, the conclusion

is inescapable that not only is there no evidence of Congressional

intent that it not apply to pending cases, but that the contrary

inference must be drawn. Neither the text of § 718 itself nor the

explanatory note of the conference committee report (U.S. Code and

Adm. News, 1972, vol. 6, p. 2406) contains any language dealing

with the issue. As noted above in part I, the section was debated

only in the Senate in April, 1971; similarly, in that debate, there

was no discussion at all of § 718’s application to pending cases,

let alone any indicating an intention that it not be so applied.

117 Cong. Rec. S.5483-92 (daily ed. April 22, 1971) and S.5534-39

(daily ed. April 23, 1971).

12/ See, Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402,

418-20 (1971), where the Court accepts petitioners' contention that

a new regulation applies to pending cases even in the absence of any

intention of a retrospective effect.

17

Indeed, the only indication as to Congress' intent in this

matter arises from the fact that § 11, the original attorneys' fee

provision as reported to the Senate as part of S.1557, did expressly

provide that it would apply only to "services rendered" after the

date of enactment of the Act (see n. 8, supra, and accompanying

13/

text). Section 11 was rejected by the Senate, however, and

what is now § 718 was enacted two days later with the language of

limitation deleted. it is clear from this that the Senate was aware

of the applicability question and chose not to include language

demonstrating an intent that § 718 should not apply with regard to

14/legal services performed prior to the Act's passage. Thus, the

only possible inference that may be drawn from the legislative

history is that the provision was meant to govern in all non-final

attorneys' fee cases in accordance with the general rule stated

in Thorpe.

We recognize, of course, that Thorpe indicates that there are

certain exceptions to the rule. None of these exceptions are

applicable in these cases, however. First, the Schooner Peggy case

states:

It is true that in mere private cases between

individuals, a court will and ought to struggle

hard against a construction which will, by a

retrospective operation, affect the rights of

parties. . . . 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) at 110, quoted

at 393 U.S. 268, 282.

13/ The language of § 11, it may be noted, indicates that it was to

apply in cases filed before the Act's passage, but only to work done

after that date.

14/ in contrast, see Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. §§ 2000e-l, 2000e-16, where Congress made it clear as to the

prospective effective dates of a statute. Section 2(c)(1) and (3)

18

These cases, of course, are not "private," but on the contrary

are, in the language of Chief Justice Marshall, "great national

concerns," and therefore:

[T]he court must decide according to existing

laws, and if it be necessary to set aside a

judgment, rightful when rendered, but which

cannot be affirmed but in violation of law,

the judgment must be set aside. Ibid.

Indeed, the present cases are precisely the same as Thorpe.

That is, they are between individuals and governmental agencies,

and their purpose is to vindicate important constitutional rights.

Therefore, "the general rule is particularly applicable here."

393 U.S. at 282.

The second class of exceptions to the general rule mentioned

15/

in Thorpe is where it is necessary to prevent "manifest injustice."

The Court referred specifically to Greene v. United States, 376 U.S.

149 (1964), which was relied upon by the North Carolina Supreme

Court in holding that the administrative regulation did not apply

to the eviction of Mrs. Thorpe (271 N.C. 468, 157 S.E.2d 147

(1967)).

14/ (cont.)

of the Education Amendments of 1972 merely specifies that the Act

shall be effective as of June 30, 1972 or July 1, 1972, the end of

the fiscal year 1972, rather than on the date the President signed

the bill. It in no way speaks to the application of the Act's

provisions to litigation pending on that effective date.

15/ If anything, in these cases, the application cf § 718 will

serve the cause of justice by reimbursing the private black plaintiffs

for taking on the task of correcting deprivations of constitutional

rights to the benefit of all society.

19

Greene, as explained in Thorpe, is clearly not applicable to

these cases. There, the Supreme Court had handed down, in a prior

case (Greene v. McElroy. 360 U.S. 474 (1959)), an order finally

disposing of the substantive issues. in 1959 Greene filed a claim

for damages with the government, and when it was denied, filed

suit. The government argued that the right to recover should be

governed by a 1960 regulation that set up a new bar to his recovery.

The Supreme Court rejected this argument, holding that this would

indeed be the retroactive overruling of a case finally disposed of,

and hence not permissible.

None of the present cases, of course, present such a situation

since, as pointed out above, they all involve appeals from lower

court orders in cases which have not as yet been finally disposed

16/of.

15/ In a school desegregation case that has been finally terminated,

whether attorneys' fees may still be obtained could be decided by

reference to the ordinary rules as to the time limitations as to

when costs must be applied for. Thus, although F.R.C.P. 54(d)

does not contain specific time limitations, many district courts

have rules requiring that costs be requested within a reasonable

time or "as soon as possible" after judgment. See, e_.£., Rule 11(c),

E.D. North Carolina. For a discussion of when it is appropriate

to seek attorneys' fees, see, Spraque v. Ticonic National Bank,

307 U.S. 161 (1939). ----------------------

20

Therefor©, for ell of the above reasons, the general rule enunciated

in Thorpe applies and these cases should be decided on the basis of

the legal standard established by § 718.

Ill

SECTION 718 REQUIRES THE APPLICATION OF

THE "PRIVATE ATTORNEY-GENERAL" STANDARD

OF NEWMAN v. PIGGIE PARK ENTERPRISES TO

THESE CASES. ~~

Once it has been decided that § 718 applies to these cases,

there can be no question but that it imposes the same standard

with regard to the award of attorneys' fees as do § 204(b) of

Title II and § 706 (k) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

and § 812(c) of Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968. That

is, the standard is that established by the Supreme Court in Newman

v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (1968).

In Newman the Court held that Title II mandated the award of

attorneys' fees to a prevailing plaintiff "unless special circum

stances would render such an award unjust." 390 U.S. at 402. Thus,

ordinarily a fee must be awarded, and the burden is on the losing

defendant to show why one should not be. The reason is that

plaintiffs seeking the desegregation of public accommodations

cannot recover damages, and:

If he obtains an injunction, he does so not for

himself alone but also as a "private attorney

general," vindicating a policy that Congress

considered of the highest priority. ibid.

Otherwise, private parties would be discouraged from advancing the

public interest by going to court. Therefore, the Court specifically

21

rejected any requirement that the defendants acted in bad faith

or were obdurate or obstinate. Subsequently, lower courts have

applied the same standard in cases arising under the attorneys'

fee provision of Title VII. See, e_.c[_., Lea v. Cone Mills Corp.,

438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971); Clark v. American Marine Corp., 320

F. Supp. 709 (E.D. La. 1970), aff'd, 437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1971).

And see, Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d 143 (5th Cir.

1971).

We urge that § 718 enacts the Newman standard for school

desegregation cases for the following reasons;

1. The relevant language, with two exceptions that will be

discussed below, of § 718 is the same as that of Title II, Title VII,

and Title VIII. Thus:

Title II, § 204(b). In any action. . .

the court, in its discretion, may allow the

prevailing party . . . a reasonable attorney's

fee as part of the costs. . . .

Title VII, § 706(k). In any action . . .

the court, in its discretion, may allow the

prevailing party, . . . a reasonable attorney's

fee as part of the costs . . . .

Title VIII, § 812(c). The court may . . .

award . . . court costs and reasonable attorneys

fees in the case of a prevailing plaintiff . . .

Section 718. Upon the entry of a final

order by a court . . . the Court, in its

discretion, upon a finding that the pro

ceedings were necessary to bring about

compliance, may allow the prevailing party

. . . a reasonable attorney's fee as part of

the costs.

Thus, these cases are governed by the general rule that legislative

use of language previously construed by the courts implies an

adoption of that judicial construction unless a contrary intention

22

overwhelmingly appears. See, e_.c£., Armstrong Paint & Varnish Works

v. Nu-Enamel Corp., 305 U.S. 315, 332 (1938).

2 . It is absolutely clear from the legislative history that

Congress intended that § 718 mean exactly the same as Titles II,

VII, and VIII. Thus, Senator Cook, who introduced the provision

and was its main sponsor, on no fewer than three occasions so

stated, and even read into the record the texts of those sections

to underscore his point. 117 Cong. Record, S.5484, 5490 (daily ed.

17/

April 22, 1971), 117 Cong. Record S.5537 (daily ed. April 23,

1971).

3. Finally, it is clear that § 718 fulfills the same purpose

as do the counsel fee provisions in the earlier acts. Just as in

Newman, plaintiffs act as "private attorneys-general" to vindicate

and advance broad public policy. And, just as this Court held as

to the Title VII attorneys' fee provision in Lea v. cone Mills,

supra, there is no reason not to conclude that precisely the

18/

same standard now applies in school cases.

17/ Thus:

This amendment is very simple. This amendment

conforms with the language of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, it complies with Title VII of the

Equal Employment Opportunities Act, and it

complies with the civil Rights Act of 1968.

Id. at 5490.

18/ It may be noted, in reference to No. 72-1065, the James case,

that this conclusion is further buttressed by the fact that teacher

dismissal cases now may be brought under Title VII as amended in

1972. Such an action would be governed by the Title VII attorneys'

fee provision and hence by Newman and Lea.

23

As noted above, however, there are two differences of signi

ficance in the text of § 718 as compared to the earlier statutes.

First, it refers to the entry of a "final order" as the time at

which attorneys' fees and costs may be taxed. It is clear that

this does not mean the final termination of the litigation, but

19/

upon the entry of a realistic, appealable order and the expiration

of appeal time or the exhaustion of appeals (see, the Remarks

of Sen. Cook at 117 Cong. Rec. S.5490 (daily ed. April 22, 1971).

Second, and more significant, is the language that an award

may be made "upon a finding that the proceedings were necessary

to bring about compliance" [with the Fourteenth Amendment]. A

considerable portion of the debate in the Senate deals with this

language, and it is clear that it is intended to protect against

two abuses, the champertous filing of unnecessary lawsuits simply

to get a fee when a school board is in fact going to comply with

the law, and the unnecessary protraction of litigation to trial

and judgment when a school board has made a bona fide and adequate

offer of settlement. See, 117 Cong. Rec. S.5485 (daily ed. April 22,

1971) (colloquy between Senators Javits and Cook), Id. at S.5490-91).

Thus, the language was in no way intended to modify the substantive

rule of Newman; i_.e_., if a plaintiff does prevail and a court

enters an order requiring compliance with the Constitution, he

must be awarded attorneys' fees except in unusual circumstances.

To summarize, we urge that the result in these cases should

be the same as in Lea v. cone Mills, supra, viz., just as in the

19/ Totally or substantially achieving "compliance ... with the

fourteenth amendment." See Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, supra. See also, Thompson as quoted page 8, supra. Of course,

the litigation would not be terminated until a reasonable period for

monitoring had expired.

24

case of the counsel fee provision of Title VII, § 718 must be

20/

given the interpretation and effect mandated by Newman.

IV

THESE PRINCIPLES REQUIRE HOLDINGS THAT

COUNSEL FEES BE ASSESSED IN EACH OF THE

PRESENT CASES.

Only a brief discussion is required to show that in each of

the cases before the Court § 718 requires the award of counsel fees.

As to all of them, the general Newman standard was met. Plaintiffs

prevailed in each, either at trial or on appeal, and the lower

court entered appropriate orders. Thus, the "private attorneys-

general" role was fulfilled, and attorneys' fees are mandated.

On the other hand, there is nothing in the record of any of these

cases to support the conclusion that there are any special circum

stances present that would militate against the award.

With regard to the specific requirement of § 718, that the

order was necessary for compliance, a case-by-case analysis also

demonstrates that awards are required.

1. James - No. 72-1065

Plaintiff James was demoted by the defendant school

board in violation, as the lower court found, of a previous court

order. Such a demotion and refusal to reappoint clearly necessitated

20/ Thus, it is clear from both the language and legislative

hTstory of § 718, together with the extension of Title VII to public

employment, that Congress has rejected any notion that there is

somehow an impropriety in assessing attorneys' fees against public

agencies.

25

a court proceeding. That the order reinstating James was necessary

is conclusively demonstrated by the board's appeal of it; obviously

the defendant has no intention of complying with the Fourteenth

Amendment unless so ordered by a court.

2. Copeland - Nos. 71-1993, 71-1994

In this case, this Court, by its order of August 2, has already

held that plaintiffs are entitled to certain orders by the district

court. Thus, it affirmed the entry of the order appealed from by

the appellant school board as "clearly warranted" and sent the case

back down with instructions to enter a further order. From this,

it is clear that not only the proceeding but the entry of the orders

involved were necessary to achieve compliance.

3. Thompson - Nos. 71-2032, 71-2033

Again, the school board defendant has appealed and urged that

the order of the district court was unwarranted. This Court, in

its order of August 2, however, rejected that argument and held

that the "objections of the school district are without merit."

This affirmance of the district court's action clearly establishes

here also that both the proceeding and the court's order were

necessary.

4. Bradley - No. 71-1774

Here, the only issue on appeal is a counsel fee award. In

essence, the court below has already made the finding required by

§ 718 by its holding that the school board resisted constitutional

mandates, hence necessitating both the proceeding and the order of

April 5, 1971, that resulted therefrom.

26

In conclusion, two observations can be made about the appli

cation of the "necessary proceeding" clause in these cases.

Clearly, the first concern of Congress is met in all of them;

since at the time the proceedings were commenced there was no

clear entitlement to counsel fees, they could not have been brought

for the purpose of obtaining them. As to the second concern, there

is no basis for concluding that the school boards involved were

ever willing voluntarily to comply with constitutional mandates.

No offers of adequate settlement were made, and the relief sought

was resisted in the court below in every instance.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the awards of counsel fees in

Nos. 71-1774, 71-1065, and 71-2032, 71-2033, should be affirmed,

and the denials of fees in Nos. 71-2032, 71-2033 and 71-1993,

71-1994 should be reversed and the cases remanded.

Respectfully submitted,

■ / *■

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ADAM STEIN

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson &

Lanning

157 E. Rosemary Street

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Attorneys for All Plaintiffs

27

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS CONRAD O. PEARSON

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson 203^ East Chapel Hill St.

& Lanning Durham, North Carolina237 West Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Attorneys for Nathaniel James, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees, 72-1065

S.W. TUCKER JAMES A. OVERTON

HENRY L. MARSH, III 623 Effingham Street

JAMES W. BENTON, JR. Portsmouth, Virginia 23704

Hill, Tucker & Marsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Michael Copeland, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants, Nos. 71-1993, 71-1994

S.W. TUCKER

HENRY L. MARSH, III

JAMES W. BENTON, JR.

Hill, Tucker & Marsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

PHILIP S. WALKER

1715 25th Street

Newport News, Va. 23607

Attorneys for Frank V. Thompson, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants, Nos. 71-2032, 71-2033

LOUIS R. LUCAS JAMES R. OLPHIN

525 Commerce Title Bldg. 214 East Clay Street

Memphis, Tennessee 38103 Richmond, Virginia 23219

W. RALPH PAIGE

420 North First St.

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Carolyn Bradley, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees, No. 71-1774

28

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that on this 26th day of August, 1972,

I served a copy of the foregoing Joint Supplemental Brief for All

Plaintiffs on counsel for defendants by depositing the same in

the United States mail, air mail postage prepaid, addressed as

follows:

Mssrs. McMullan, Knott and Carter

Beaufort County Bd. of Education

P.0. Box 1148

Washington, North Carolina 27889

Attorneys for Defendant-Appellant in No. 72-1065

Mr. Michael A. Korb, Jr.

224 Pembroke One Building

281 Independence Boulevard

Virginia Beach, va. 23462

Counsel for Defendants-Appellees in Nos.

71-1993, 71-1994

Mr. Robert V. Beale

Bateman, West & Beale

11048 Warwick Boulevard

Newport News, Va. 23601

Mr. P. A. Yeapanis

118 Main Street

Newport News, Va. 23601

Counsel for Defendants-Appellees in

Nos. 71-2032, 71-2033

Mr. George B . Little

Browder, Russell, Little & Morris

1510 Ross Building

Richmond, Va. 23219

Counsel for Defendants-Appellants in No. 71-1774.

29