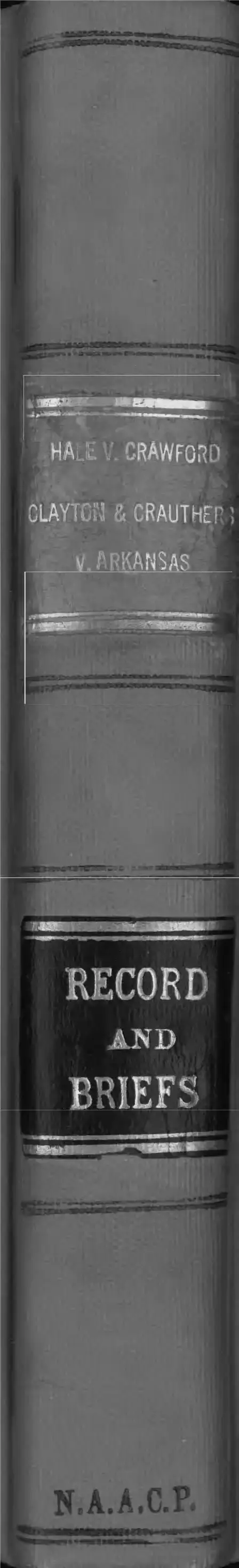

Hale v. Crawford Record and Briefs

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1932 - January 1, 1935

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hale v. Crawford Record and Briefs, 1932. 7f943d4d-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e398aac2-900e-460c-8e6b-c0261e02ca80/hale-v-crawford-record-and-briefs. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

C

O

HA i CRAWFORD

LAYTOt'3 & CRAUTHEP;

V. KANSAS

a— W

RECORD

AND

BRIEF?

O C T O B E R T E R M , 1 9 3 2 .

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT.

No. 2824.

FRANK G. HALE, Lieutenant Detective,

Massachusetts State Police,

RESPONDENT, APPELLANT,

V.

GEORGE CRAWFORD,

PETITIONER, a p p e l l e e .

APPEAL FROM THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS,

FROM DECREE (LOWELL, J.), MAY 2, 1933.

T R A N SC R IP T OF RECORD.

JOSEPH E. WARNER,

Attorney General, Massachusetts,

S. D. BACIGALUPO,

Assistant Attorney General, Massachusetts,

GEORGE B. LOURIE,

Assistant Attorney General, Massachusetts,

JOHN GALLEHER,

District Attorney, Loudoun County, V irginia,

for Appellant.

J. WESTON ALLEN,

BUTLER R. WILSON,

for Appellee.

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT.

O C T O B E R T E R M , 1 9 3 2 .

No. 2824.

FRANK G. HALE, Lieutenant Detective,

M assachusetts State Police,

RESPONDENT, APPELLANT,

V.

GEORGE CRAWFORD,

PETITIONER, APPELLEE.

APPEAL FROM THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS,

FROM DECREE (LOWELL, J.), MAY 2, 1933.

T R A N SC R IPT OF RECORD.

JOSEPH E. WARNER.

Attorney General, Massachusetts,

S. D. BACIGALUPO,

Assistant Attorney General, Massachusetts,

GEORGE B. LOURIE,

Assistant Attorney General, Massachusetts,

JOHN GALLEHER,

D istrict Attorney, Loudoun County, V irginia,

for Appellant.

J. WESTON ALLEN,

BUTLER R. WILSON,

for Appellee.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

I’AOK

Court (Circuit Court of Appeals) and Title of C a s e ............................................... 1

T ra n sc r ip t of R ecord of D is t r ic t C o u r t :

Title of Case in District C o u r t .............................................. 1

Motion to Amend and Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus . 1

Warrant to A r r e s t ............................................................................................. 7

Marshal’s Return on Summons 8

Writ of Habeas Corpus issued . . . . . . . . 9

Answer and Return of R e s p o n d e n t ................................................................. 9

Return on Warrant issued Feb. 17, 1933 10

Writ of Habeas Corpus and Officer’s Return of Service . . . 11

Agreement of C o u n s e l ........................................................................................... 12

Population Statistics, e t c . ......................................................................... 18

Lists of qualified Taxpayers, e tc...................................................................... 24

H e a r i n g .......................................................................................................................25

Finding of the District C o u r t ..................................................................................25

Order of C o u r t ............................................................................................................. 26

Petition for Appeal and Allowance t h e r e o f .......................................................26

Exhibit A,—Requisition ............................................................................................ 27

B,—W a r r a n t ....................................................................................... 7,33

Petition for A p p e a l .................................................................................................... 34

Assignment of E r r o r s ........................................................................................... 34

P r a e c i p e .......................................................................................................................35

Citation i s s u e d ............................................................................................................. 36

Certificate of Clerk of District Court . . . . . . 36

IJNilED STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT.

O C T O B E R T E R M , 1 9 3 2 .

No. 2824.

FRANK G. HALE, Lieutenant Detective, Massachusetts

State Police,

RESPONDENT, APPELLANT,

V.

GEORGE CRAWFORD,

PETITIONER, APPELLEE.

TRANSCRIPT OF RECORD OF DISTRICT COURT.

No. 4962, C iv il D o c k e t ,

GEORGE CRAAVFORD, P e t it io n e e fo b W r it of H abeas C o r p u s ,

v.

FRANK G. HALE, L ie u t . D e t e c t iv e , M a ssa c h u se tts S t a t e P o l ic e ,

R e s p o n d e n t .

A petition for writ of habeas corpus was filed in the clerk’s office

on the eighteenth day of February, A. D. 1933, and was duly entered

at the December Term of this court, A. D. 1932.

Said petition for writ of habeas corpus was subsequently amended

by a motion to amend filed and allowed by the court, and as amended

is as follows:

MOTION OF PETITIONER TO AMEND PETITION

A N D

AMENDED PETITION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS.

[Filed and Allowed April 5, 1933.]

To the Honorable Judges of the District Court of the United Stales

within and for the District of Massachusetts :

And now comes George Crawford, in his own proper person, and

2 Transcript of Record of District Court.

moves to amend his petition by inserting after the second para

graph the following matter, viz.:

The petitioner says that he was born twenty-eight years ago in

Augusta, Georgia, lived in Virginia from 1918 to September 1931,

since which latter time he has resided continuously in Boston, Mass

achusetts ; that he is not the person alleged to have committed the

crime set forth in the demand for his rendition; that since January

12, 1933, he has been confined in the Suffolk County jail under

bail of $25,000 which it is impossible for him to furnish; that he

is wholly without means to prosecute his petition or make his

defense and has had no opportunity to object to the method of

the denial to him of due process of law.

And the petitioner further says that he cannot lawfully be held

by virtue of said warrant or order, and his detention or restraint

thereunder is in violation of the Constitution of the United States

and laws of the United States in that:

1. The said warrant is based upon an alleged indictment pur

porting to have been found against him by the grand jury of

Loudoun County in the State of Virginia, which alleged indictment

is null and void, and was procured in a manner which denies to

your petitioner rights guaranteed to him by the Constitution of

the United States and the laws of the United States.

2. The said grand jury which is alleged to have found said

alleged indictment was impaneled in a manner which denied to

your petitioner rights guaranteed to him by the Constitution of the

United States, by reason of which said indictment is null and void,

denies to your petitioner rights secured to him by the Constitu

tion of the United States and its laws and cannot be made the

foundation of any detention of your petitioner.

3. Your petitioner is a member of the colored race, a Negro,

and a citizen of the United States; that the population of said

Loudoun County in the State of Virginia contains great numbers

of persons of the colored race who are citizens of Virginia and of

the United States, registered voters, owners of property, taxpayers

and in all respects proper and suitable persons to serve upon grand

and petit juries in said Loudoun County; that, although colored

persons, members of the Negro race, are 650,000 or 21.8 percent

of the population of the State of Virginia, for many years it has

been the practice and custom, throughout the State of Virginia

and throughout said Loudoun County, to exclude from service upon

all grand and petit juries all persons of the colored or Negro race

by reason of their race, color or previous condition of servitude and

without consideration as to whether said colored persons were

proper and suitable persons to serve upon said juries, which prac

tice and custom has the force and effect of a State Statute and was

and is contrary to the Constitution of the United States; that pur

suant to said illegal and unconstitutional practice and custom all

colored persons of the Negro race were by reason of their color,

race or previous condition of servitude excluded from the grand

jury which purported to return the indictment by reason of which

your petitioner is unlawfully detained, whereby your petitioner

was and is denied rights secured to him by the Constitution of the

United States and its laws.

4. Because there exists in Loudoun County and the State of

Virginia against colored people, members of the Negro race, gen

erally, and against the petitioner particularly, an unreasonable

race or color prejudice, which will make it impossible for him to

obtain that fair and impartial jury of the vicinage, guaranteed to

him by the Constitution of the United States and its laws and that

will deny to him the due process of law and the fair and impartial

trial which are of right his under the fourteenth amendment to

the United States Constitution and its laws.

5. In divers other respects the detention or restraint of your

petitioner denies to him rights secured to him by the Constitution

of the United States and its laws.

So that his petition as amended will appear as follows, viz.:

Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus.

To the Honorable Judges of the District Court of the United States

within and for the District of Massachusetts:

Respectfully represents George Crawford of Boston, in the Com

monwealth of Massachusetts, and District of Massachusetts afore

Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus. 3

4 Transcript of Record of District Court.

said, that he is unlawfully restrained of his liberty in Boston, in

the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and District of Massachu

setts aforesaid, by the said Frank G. Hale; that the pretense of

such restraint according to the belief of your complainant is a

certain warrant or order, whereof a copy is hereto annexed, pur

porting to have been issued by the Governor of the Commonwealth

of Massachusetts; that the said warrant or order has been issued

without authority of law, improvidently and in violation of the

Constitution and of the laws of the United States and of said Com

monwealth.

And your complainant further says that he cannot lawfully be

held by virtue of said warrant or order, and his detention and

restraint thereunder are in violation of the Constitution and of the

laws of the United States and of said Commonwealth, in that he

is not the person by name designated in said warrant or order or

so to be taken or held under the terms of the authority thereof;

that said warrant or order does not upon its face or by its recital

purport to authorize the taking or detention of said petitioner,

George Crawford, thereunder; that said petitioner, George Craw

ford, is not the oerson alleged to have committed the crime or

offense purporting to be set forth or exhibited in the demand for

extradition upon which the said warrant or order of the Governor

of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has issued.

The petitioner says that he was born twenty-eight years ago in

Augusta, Georgia, lived in Virginia from 1918 to September 1931,

since which latter time he has resided continuously in Boston,

Massachusetts; that he is not the person alleged to have com

mitted the crime set forth in the demand for his rendition; that

since January 12, 1933, he has been confined in the Suffolk County

jail under bail of $25,000 which it is impossible for him to furnish ;

that he is wholly without means to prosecute his petition or make

his defense and has had no opportunity to object to the method of

the denial to him of due process of law.

And the petitioner further says that he cannot lawfully be held

by virtue of said warrant or order, and his detention or restraint

thereunder is in violation of the Constitution of the United States

and laws of the United States in that:

1. The said warrant is based upon an alleged indictment pur

porting to have been found against him by the grand jury of Lou

doun County in the State of Virginia, which alleged indictment is

null and void, and was procured in a manner which denies to

your petitioner rights guaranteed to him by the Constitution of

the United States and laws of the United States.

2. The said grand jury which is alleged to have found said

alleged indictment was impaneled in a manner which denied to

your petitioner rights guaranteed to him by the Constitution of

the United States, by reason of which said indictment is null and

void, denies to your petitioner rights secured to him by the Con

stitution of the United States and its laws and cannot be made the

foundation of any detention of your petitioner.

3. Your petitioner is a member of the colored race, a Negro,

and a citizen of the United States; that the population of said

Loudoun County in the State of Virginia contains great numbers

of persons of the colored race who are citizens of Virginia and of

the United States, registered voters, owners of property, taxpay

ers and in all respects proper and suitable persons to serve upon

grand and petit juries in said Loudoun County; that, although

colored persons, members of the Negro race, are 650,000 or

21.8% of the population of the State of Virginia, for many years

it was been the practice and custom, throughout the State of

Virginia and throughout said Loudoun County, to exclude from

service upon all grand and petit juries all persons of the colored

or Negro race by reason of their race, color or previous condition

of servitude and without consideration as to whether said colored

persons were proper and suitable persons to serve upon said

juries, which practice and custom has the force and effect of a

State Statute and was and is contrary to the Constitution of the

United States, that pursuant to said illegal and unconstitutional

practice and custom all colored persons of the Negro race were

by reason of their color, race or previous condition of servitude

.excluded from the grand jury which purported to return the

Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus. 5

6 Transcript of Record of District Court.

indictment by reason of which your petitioner is unlawfully de

tained, whereby your petitioner was and is denied rights secured

to him by the Constitution of the United States and its laws.

4. Because there exists in Loudoun County and the State of

Virginia against colored people, members of the Negro race, gen

erally, and against the petitioner particularly, an unreasonable

race or color prejudice, which will make it impossible for him

to obtain that fair and impartial jury of the vicinage, guaranteed

to him by the Constitution of the United States and that will deny

to him the due process of law and the fair and impartial trial

which are of right his under the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution and the laws of the United States.

5. In divers other respects the detention or restraint of your

petitioner denies to him rights secured to him by the Constitution

of the United States and its laws.

Wherefore, your petitioner prays that a writ of habeas corpus

may issue, and for such other and further relief as to this Honor

able Court may seem meet to the end that said petitioner, George

Crawford, may obtain his liberty.

GEORGE CRAWFORD.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Suffolk, ss. Boston, March 29, 1933.

Then personally appeared the above-named George Crawford

and made oath that the statements of fact set forth in the fore

going petition are true, to the best of his knowledge and belief,

and that he believes that all inferences of fact set forth are true.

Before me,

Butler R. W ilson,

[seal] Notary Public.

Allowed April 5, 1933.

James A. Lowell,

District Judge.

7

Warrant to Arrest.

T he Commonwealth of Massachusetts

His Excellency Joseph B. Ely,

Governor of the Commonwealth.

To Any Sheriff, Deputy Sheriff, Officer of the

(L.s.) Division of State Police of the Department of

Public Safety, and to Any Officer authorized to

(signed) serve warrants in criminal cases within this

Joseph B. Ely Commonwealth.

Whereas, it has been represented to me by the Governor of the

State of Virginia that George Crawford stands charged in said

State with the crime of Murder which the Governor of the State

of Virginia certifies to be a crime under the Laws of said State,

committed in the county of Loudoun in said State, and that said

George Crawford is a fugitive from the justice of said State and

has taken refuge in this Commonwealth, and the Governor of the

State of Virginia having, pursuant to the Constitution and Laws

of the United States, demanded of me that I shall cause the said

George Crawford to be arrested and delivered to E. S. Adrain and

D. H. Cooley, who are the agents of the Governor of the State of

Virginia and are duly authorized to receive the said George Craw

ford into their custody and convey him back to the State of Vir

ginia :

And whereas, the said representation and demand are accom

panied by certain documents whereby the said George Crawford

is shown to have been duly charged with the said crime and to

be a fugitive from the justice of the State of Virginia, and to have

taken refuge in this Commonwealth, which documents are duly

certified by the Governor of the State of Virginia to be authentic

and duly authenticated:

Wherefore, you are required to arrest and secure the said George

Crawford wherever he may be found within this Commonwealth,

and afford him such opportunity to sue out a writ of Habeas

Corpus as is prescribed by the laws of this Commonwealth, and

8 Transcript of Record of District Court.

thereafter deliver him into the custody of the said E. S. Adrain

and D. H. Cooley to be taken back to the State of Virginia from

which he fled, pursuant to the said requisition; all of which shall

be without charge to this Commonwealth; and also to return this

warrant and make return to the Secretary of the Commonwealth

of all your proceedings had thereunder and of all facts and circum

stances relating thereto.

And all officers authorized to serve warrants in criminal cases

within this Commonwealth are hereby required to afford all need

ful assistance in the execution hereof.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto signed my name and caused

the Great Seal of the Commonwealth to be affixed, this seventeenth

day of February, in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hun

dred and thirty-three.

By His Excellency the Governor:

F. W. Cook

Secretary of the Commonwealth.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts

Boston, February 18, 1933.

A True Copy.

Witness the Great Seal of the Commonwealth, this eighteenth

day of February in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hun

dred and thirty-three.

F. W. Cook

[seal] Secretary of the Commonwealth.

On the twenty-fifth day of February, 1933, a summons to show

cause was issued, being made returnable into court on Monday,

February 27, 1933, at two o’clock P. M.

Due return on said summons was made by the marshal into

court on February 25, 1933, and is as follows:

V

MARSHAL’S RETURN ON SUMMONS.

United States of America,

Massachusetts District, ss. Boston, February 20, 1933.

Pursuant hereunto, I have this day summoned the within-named

Answer and Return of Respondent. 9

Frank G. Hale, Lieutenant Detective, Massachusetts State Police,

to appear before the District Court of the United States, as within

directed, by giving to him in hand at State House, Boston, Mass.,

a true and attested copy of the within summons to show cause.

WILLIAM J. KEVILLE, United States Marshal,

by Joseph M. W inston , Deputy.

At the same term, to wit, February 27, 1933, it was ordered by

the court, the Honorable Hugh D. McLellan, District Judge, sit

ting, that writ of habeas corpus issue.

Also at the same term, to wit, March 18, 1933, the following

Answer and Return of Frank G. Hale, Respondent, was filed:

ANSWER AND RETURN OF FRANK G. HALE, RESPONDENT.

[Filed March 18, 1933.]

Now comes Frank G. Hale, the respondent named in the within

petition, and makes and files his return with the writ in said cause.

Said respondent says that he is an officer of the Division of

State Police of the Department of Public Safety of the Common

wealth of Massachusetts, and as such is authorized to serve war

rants in criminal cases within said Commonwealth; that the peti

tioner is in his lawful custody and keeping, as such officer, under

and by virtue of and pursuant to the lawful warrant under the

seal of His Excellency Joseph B. Ely, Governor of the Common

wealth of Massachusetts, as a fugitive from justice of the State

of Virginia, to be delivered to the agent appointed by the governor

of said state to receive him, a copy of which said warrant, together

with the return thereon, is annexed hereto and expressly made a

part of this answer; that said warrant has been duly and law

fully served upon said petitioner, and that he has heretofore and

thereby been lawfully arrested thereon, as appears from the

return made upon said warrant; that by virtue of said service

and arrest the petitioner is now lawfully held and detained in the

custody of the respondent to await full execution of said warrant,

pursuant to its terms and authority; and that the petitioner so

held under said warrant is the identical person named therein as

the alleged fugitive.

10 Transcript of Record of District Court.

And the respondent further denies each and every allegation in

the petition set forth except such as are specifically admitted

herein.

FRANK G. HALE.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Suffolk, ss. Boston, March 17, 1933.

Then personally appeared the above-named Frank G. Hale and

made oath that all statements of fact made of his personal knowl

edge are true, and that all statements herein made he verily be

lieves to be true. James J. Kelleher,

Notary Public.

[Memorandum. Copy of warrant, referred to in the original

answer and return as annexed, is here omitted, as it is printed as

part of the amended petition for writ of habeas corpus on page 7,

of this transcript of record. James S. Allen, Clerk]

Return on Warrant Issued February 17, 1933.

Suffolk ss. Feb. 18,1933.

By virtue of the within precept I have this day arrested the

within named George Crawford at the Charles St. Jail, the de

fendant Crawford, stated that he wished to avail himself of Ha

beas Corpus rights of intentions through his attorney Butler R.

Wilson to apply for a petition for a writ of Habeas Corpus in the

Federal District Court at Boston. In view of this fact I left him

in charge of the Sheriff and Keeper of the Suffolk County Jail,

Charles St., Boston, Mass, with a copy of this warrant for safe

keeping. Frank G. Hale

State Police Officer.

Suffolk ss. Feb. 18, 1933.

At IT. 45 A. M. this day I was summoned by Deputy U. S. Mar

shal Joseph M. Winston to appear before the District Court of the

United States, to be holden at Boston, within and for the Massa

chusetts District on Monday, the 27th day of February, current at

2 o’clock p. M., then and there to show cause, if any I have, why

Writ of Habeas Corpus. 11

a writ of Habeas Corpus should not issue for the body of George

Crawford, as prayed for in his petition.

Frank G. Hale

State Police Officer.

This cause was thence continued to the present March Term

of this court, A. D. 1933, when, to wit, April 5, 1933, a motion of

the petitioner to amend his petition for writ of habeas corpus is

filed and allowed by the court, the Honorable James A. Lowell,

District Judge, sitting.

On the said fifth day of April, A. D. 1933, the amended peti

tion was filed, which is hereinbefore set forth.

On the twenty-fourth day of said April, 1933, the following Writ

of Habeas Corpus issues, returnable forthwith:

WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS.

United States of America,

Massachusetts District.

[seal] The President of the United States of America

To Frank G. Hale, Lieutenant Detective, Massachu

setts State Police, Greeting :

We command you that the body of George Crawford by you

restrained of his liberty, as it is said, you take and have before

our Judge of our District Court of the United States at the United

States Court House in Boston, in said District, forthwith to do

and receive what our said court shall then and there consider

concerning him in this behalf, and then and there show cause (if

any you have), of the taking and detaining of the said George

Crawford.

And have you there this writ with your doings therein.

Witness, the Honorable James A. Lowell at Boston aforesaid,

the twenty-fourth day of April, in the year of our Lord one thou

sand nine hundred and thirty-three.

JAMES S. ALLEN, Cleric,

by John E. Gilman, Jr., Deputy Clerk.

12 Transcript of Record of District Court.

Officer’s Return on Writ.

United States of America.

District of Massachusetts, ss. Boston, Mass., April 24,1933.

I hereby certify that I have this day served the within Habeas

Corpus by giving in hand to Frank G. Hale, Lieutenant Detective,

Massachusetts State Police, a true and attested copy thereof.

William J. Keville, United States Marshal,

by Joseph M. W inston, Deputy.

Service, $2, travel, .06—$2.06.

Also, on said twenty-fourth day of April, A. D. 1933, the fol

lowing Agreement is filed:

AGREEMENT.

[Filed April 24, 1933.]

Now come the parties to the above-entitled cause and agree as

follows:

1. That the indictments in question in this cause were returned

in the Circuit Court of Loudoun County, in the State of Virginia,

by the grand jury of said county, on or about February 8, 1932,

and charge the crime of murder committed on or about January

13, 1932, at Middleburg, in Mercer district, in said Loudoun

County, Virginia.

2. That the law of Virginia, in force long prior to both dates

and still in force, places jurisdiction over crimes committed within

a county of said State in the Circuit Court of such county.

3. That the law with reference to grand jurors, in force in the

State of Virginia at the time the grand jury list was prepared and

of the return of the indictments in this case, is as follows:

“ Code of Virginia, Chapter 193.

Grand Juries.

Section 4852. When and how grand jurors to be selected

by judges of circuit courts of counties and corporation or

hustings courts of cities; lists to be delivered to clerk; when

and how jurors summoned.—The judges of the said courts

Agreement. 13

shall annually, in the month of June, July, or August, select

from the male citizens of each county of their respective

circuits and in their several cities forty-eight persons twenty-

one years of age and upwards, of honesty, intelligence, and

good demeanor, and suitable in all respects to serve as grand

jurors, who shall be the grand jurors for the county or city

from which they are selected for twelve months next there

after. Such jurors shall be selected in each county from the

several magisterial districts of the county, and in each city

from the several wards of the cities in proportion to the

population thereof, and the judge making the selection shall

at once furnish to the clerk of his court in each county of his

circuit or in his city a list of those selected for that county

or city. The clerk, not more than twenty days before the

commencement of each term of his court at which a regular

grand jury is required, shall issue a venire facias to the

sheriff of his county or sergeant of his city, commanding him

to summon not less than twelve nor more than sixteen of the

persons selected as aforesaid (the number to be designated

by the judge of the court by an order entered of record) to

be named in the writ, to appear on the first day of the court

to serve as grand jurors. No such person shall be required

to appear more than once until all the others have been

summoned once, nor more than twice until the others have

been twice summoned, and so on: provided, that no male

citizen over sixty years of age shall be compelled to serve as

a grand juror. The clerk, in issuing the venire facias, shall

apportion the grand jurors, as nearly as may be, ratably

among the magisterial districts or wards; but the Circuit

Court of James City county, or the judge thereof in vacation,

shall select the grand jurors for such court from said county

and the city of Williamsburg in such proportion from each as

he may think proper.

Section 4853. Who are qualified; number of grand jurors,

regular and special.—A regular grand jury shall consist of

not less than eleven nor more than sixteen persons, and a

14 Transcript of Record of District Court.

special grand jury of not less than six nor more than nine

persons. Each grand juror shall be a citizen of this State,

twenty-one years of age, and shall have been a resident of

this State two years, and of the county or corporation in

which the court is to be held one year, and in other respects

a qualified juror, and not a constable, or overseer of a road,

and, when the grand juror is for a circuit court of a county,

not an inhabitant of a city, except in those cases where the

circuit court of the county has jurisdiction in the city, in

which case the city shall be considered as a magisterial dis

trict, or the equivalent of a magisterial district, of the county

for the purpose of the jury lists.”

4. It is further agreed that the following facts may be consid

ered by the court as if testified to by the persons mentioned and

as true, being first subject, however, to a ruling by the court as

to their admissibility as evidence bearing upon the issues which

may properly be raised in these proceedings, saving the rights of

the party aggrieved by such ruling.

5. That the Honorable John R. H. Alexander is the Circuit

Judge presiding over the Twenty-sixth Judicial Circuit of Virginia,

which is comprised of the counties of Rappahannock, Fauquier

and Loudoun and their respective circuit courts ; that the Honor

able Edward O. Russell is clerk of the Circuit Court of said Lou

doun County; that the Honorable Eugene S. Andrian is sheriff of

said Loudoun County; and that each of said persons held said

office prior to January 13, 1932, and still holds the same.

6. That said Honorable John R. H. Alexander, Circuit Judge as

aforesaid, would, if called to the stand, testify as follows: That

he has been a member of the bar of Loudoun County since 1906,

and has been Circuit Judge since 1929, presiding over the Twenty-

sixth Judicial Circuit as aforesaid; that prior to 1929 he had

served as Commonwealth Attorney in Loudoun County; that he

has never known of any Negro to be called for jury duty or to

serve on any jury in Loudoun County or the other two counties

in his circuit; that he makes up the grand jury lists for Loudoun

Agreement. 15

County from the lists of qualified taxpayers, and tries to select

representative persons from that list because of the serious nature

and importance of the work a grand jury has to do; that he

knows there are Negroes in Loudoun County who meet the com

mon law and statutory requirements of grand jurors, and has no

doubt there are Negroes in the county who further measure up

to the standards which he himself in his discretion has estab

lished for grand jurors of the county, but he has never investi

gated the qualifications of any Negro with the purpose of deter

mining his fitness for jury duty ; that no question has ever been

raised about Negroes serving on any jury in Loudoun County ;

that the Negroes of Loudoun County appear satisfied with existing

conditions and he does not know whether Negroes of the county

would want to serve on a jury; and that no suggestion that they

be placed on the jury list has ever been made to him by any

person ; that he has nothing to do with drawing the felony juries,

but his functions are limited to selecting the lists from which the

grand juries are drawn, and he has never considered Negroes for

grand jury service, the subject never having been considered by

him or brought to his attention ; that it is a custom in Loudoun

County and the other two counties in his circuit, and, so far as

he knows, in the other counties of the State to use white men

exclusively for jury service in the State courts, and he has just

followed the custom.

7. That the grand jurors composing the grand jury which

returned said two indictments were—

(1) C. H. Arnold. (7) T. M. Derflinger.

(6) George Laycock.

8. That said Honorable Edward O. Russell, clerk of the Circuit

Court of Loudoun County, as aforesaid, would, if called to the

stand, testify as follows: That he has been clerk of the Circuit

Court of Loudoun County since 1929; that he has lived in Lou

12) M. E. Ball.

(3) Frank Saunders.

(4) George Ankers.

(5) Alfred Dulin.

(8) R. Carroll Chinn.

(9) James M. Cole.

(10) Walter Leith.

(11) Fred S. Warren.

16 Transcript of Record of District Court.

doun County practically all his life; that he has never known of

a Negro to serve as a grand juror or petit juror; that the names

of jurors are taken from the lists of qualified taxpayers; that

there has never been a Negro on any grand, petit or felony jury

since he took office in 1929 nor at any time prior to that in his

recollection; that he, said Russell, selected the aforesaid grand

jurors from the list furnished to him by said Judge Alexander;

that it was a regular grand jury ; that he personally knew every

member of said grand jury to be a white man; that he has per

sonally checked the names of said grand jurors against the quali

fied taxpayers list of Loudoun County for 1931 and found that

the name of every said grand juror listed there was the name of a

white man.

9. That both said Honorable John R. H. Alexander, Circuit

Judge, and said Honorable Edward O. Russell, clerk of said court,

as aforesaid, would further testify that each knew that every name

on the grand jury list prepared by said Honorable John R. H.

Alexander for Loudoun County for 1931-1932, from which said

Honorable Edward 0. Russell selected the grand jury aforesaid,

to be the name of a white man.

10. That the lists of qualified taxpayers for Loudoun County for

the years 1928, 1929 and 1930 were furnished to attorneys for

petitioner by said Honorable Edward O. Russell, clerk of the Cir

cuit Court of Loudoun County as aforesaid; that said attorneys

were unable to procure from said Russell a copy of the qualified

taxpayers list for 1931 by reason of the fact that said Russell had

only one copy; but that said attorneys and said Honorable Ed

ward 0. Russell, clerk of the Circuit Court as aforesaid, then and

there checked said lists of qualified taxpayers for the years 1928,

1929 and 1930 with said 1931 list to ensure that said three lists

and said 1931 list were exactly the same in style and manner of

composition and grouping of taxpayers listed; that all four of

said lists were identical in these respects; and that in each list

the qualified Negro taxpayers listed were set apart from the white

taxpayers listed and labelled “ colored ”.

11. That Honorable Eugene S. Adrian, sheriff of said Loudoun

Agreement. 17

County, would, if placed upon the stand, testify as follows: That

he had been sheriff of Loudoun County for ten years and deputy

sheriff during the seven years immediately preceding; that the

sheriff or his deputy serves the writ summoning persons to jury

duty in the county; that he has never served such a writ on a

Negro or known of such a writ to be served on a Negro; that he

has lived in Loudoun County all his life; that he has never seen

a Negro serving on any jury; that it was the existing custom not

to put Negroes on any jury in Loudoun County; that this is a

matter of common knowledge in said county.

12. The lists of qualified taxpayers of Loudoun County for the

years 1928, 1929 and 1930, set out in paragraph 10 of this state

ment of agreed facts, as officially printed by the county, and cer

tain population statistics from the United States census, to be

considered by the court so far as material and subject to the rul

ing as referred to in paragraph 4 herein, attached hereto and

made a part hereof.

J. WESTON ALLEN,

BUTLER R. WILSON,

Attorneys for the Petitioner.

S. D. BACIGALUPO,

Assistant Attorney General of Massachusetts,

for the Respondent.

Department of Commerce

Bureau of the Census

Office of the Director

Washington April 18, 1933.

I hereby certify that the attached compilations consisting of six

sheets giving population statistics for the State of Virginia, and

for Fauquier, Loudoun and Rappahannock counties, have been

prepared from the original records on file in the Bureau of the

Census., W. F. Austin

[SEAL] Director of the Census.

18 Transcript of Record of District Court.

Six pages Page 1

Composition of the Population of Virginia and of Fauquier,

Loudoun, and Rappahannock Counties: 1910

Virginia

County

Fauquier Loudoun

Rappa

hannock

Total population . 2,061,612 22,526 21,167 8,044

White . . . . 1,389,809 15,037 15,946 5,896

Negro . . . . 671,096 7,486 5,221 2,148

Males 21 years old and over:

White . . . . 363,659 3,858 4,423 1,453

Negro . . . . 159,593 1,659 1,269 443

Illiterates, 10 years of age and

over:

Total . . . . 232,911 2,148 1,690 1,332

Per cent 15.2 12.7 10.3 22.5

White . . . . 83,825 556 444 858

Per cent 8.1 4.9 3.5 19.6

Negro . . . . 148,950 1,591 1,246 474

Per cent 30.0 29.2 32.2 30.5

School attendance, 6-20 years

of age :

Total . . . . 392,499 4,427 3,980 1,640

White . . . . 278,091 3,070 3,073 1,149

Negro . . . . 114,346 1,357 907 491

Rural population . 1,585,083 22,526 21,167 8,044

Number of families:

White . . . . 281,489 3,069 3,459 1,184

Negro . . . . 137,963 1,420 977 389

Number of homes owned:

White . . . . 154,325 1,850 2,004 715

Negro . . . . 56,997 754 431 206

Agreement. 19

Six pages Page 2

Composition of the Population of Virginia and of Fauquier,

Loudoun, and Rappahannock Counties: 1920

Virginia

County

Fauquier Loudoun

Rappa

hannock

Total population . 2,309,187 21,869 20,577 8,070

White . . . . 1,617,909 14,934 15,765 5,916

Negro . . . . 690,017 6,932 4,810 2,154

Males 21 years old and over:

White . . . . 437,083 3,933 4,357 1,496

Negro . . . . 176,036 1,686 1,182 513

Illiterates, 10 years of age and

over:

Total . . . . 195,159 1,612 959 1,320

Per cent 11.2 9.8 6.0 22.1

White . . . . 72,625 517 271 872

Per cent 5.9 4.5 2.2 19.7

Negro . . . . 122,322 1,095 688 448

Per cent 23.5 21.6 19.3 29.1

School attendance, 6-20 years

of age:

Total . . . . 483,978 4,045 4,361 1,550

White . . . . 346,287 2,980 3,317 1,098

Negro . . . . 137,560 1,064 1,044 452

Rural population . 1,635,203 21,869 20,577 8,070

Number of families:

White . . . . 334,708 3,171 3,518 1,232

Negro . . . . 148,362 1,352 933 398

Number of homes owned:

White . . . . 180,755 1,906 2,031 649

Negro . . . . 61,227 721 459 175

20 Transcript of Record of District Court.

6 pages Page 3

Composition of the Population of Virginia and of Fauquier,

Loudoun, and Rappahannock Counties: 1930

Virginia

County

Fauquier Loudoun

Rappa

hannock

Total population 2,421,851 21,071 19,852 7,717

White . . . . 1,770,405 14,797 15,502 5,839

Negro . . . . 650,165 6,272 4,347 1,878

Males 21 years old and over:

White . . . . 487,525 4,054 4,414 1,546

Negro . . . . 162,285 1,582 1,151 482

Illiterates, 10 years of age and

over:

Total . . . . 162,588 1,473 987 1,033

Per cent 8.7 9.1 6.3 17.9

W h ite .................................. 67,220 580 383 657

Per cent 4.9 5.0 3.1 15.1

N ergo .................................. 95,148 893 604 376

Per cent 19.2 19.1 18.4 26.5

School attendance, 6-20 years

of age:

Total . . . . 537,801 4,580 4,054 1,623

White . . . . 390,846 3,265 3,173 1,181

Negro . . . . 146,760 1,315 881 442

Rural population . 1,636,314 21,071 19,852 7,717

Rural-farm 948,746 12,473 10,223 6,047

White . . . . 689,141 9,270 8,898 4,711

Males 21 years old and

over . . . . 176,828 2,483 2,556 1,203

Negro . . . . 258,967 3,203 1,322 1,336

Males 21 years old and

over . . . . 56,813 757 362 307

Rural-nonfarm . 687,568 8,598 9,629 1,670

White '. 509,608 5,527 6,604 1,128

Agreement. 21

Males 21 years old and

over . . . . 139,461 1,571 1,858 343

Negro . . . . 177,797 3,069 3,025 542

Males 21 years old and

over . . . . 45,837 825 789 175

Number of families:

White . . . . 388,049 3,282 3,721 1,252

Negro . . . . 140,726 1,245 894 346

Number of homes owned :

White . . . . 210,835 1,883 2,142 691

Negro . . . . 61,294 648 454 192

Six pages Page 4

White and Negro Males 10 years old and over Engaged in Gainful

Occupations, by Industry Groups, for Fauquier, Loudoun,

and Rappahannock Counties, Virginia : 1930

Fauquier

County

Loudoun Rappahannock

White Negro White Negro White Negro

All industries . 4,246 1,769 4,543 1,307 1,681 556

Agriculture 2,468 1,124 2,835 797 1,243 383

Farmers (owners and

tenants) 1,127 214 1,230 59 516 110

Farm managers and

foremen 78 8 93 2 15 __

Farm laborers 1,260 902 1,502 735 712 273

Wage workers 1,069 853 1,373 724 620 257

Unpaid family

workers 191 49 129 11 92 16

Forestry and fishing 20 10 1 2 _ _ _

Coal mines — 1 __ _

Other extraction of min-

erals 9 3 20 22 5 5

Building industry 360 58 329 91 60 12

Chemical and allied in-

dustries 1 - 2 _ 1 _ _

Cigar and tobacco facto

ries

Clothing industries

Food and allied indus

tries

Automobile factories and

repair shops

Iron and steel industries

Saw and planing mills .

Other woodworking and

furniture industries .

Paper printing and allied

industries

Cotton mills

Silk mills

Other textile industries

Independent hand trades

Other manufacturing in

dustries

Construction and main

tenance of streets, etc.

Garages, greasing sta

tions, etc.

Postal service

Steam and street rail

roads

Telegraph and telephone

Other transportation and

communication

Banking and brokerage

Insurance and real estate

Automobile agencies and

filling stations .

Wholesale and retail

trade, except automo

biles

22 Transcript of of District Court.

- - - 2 -

1 4 1 - -

- 39 4 8 -

9 23 2 4 _

5 24 6 3 1

21 48 6 41 3

1 10 3 12 -

-

12

-

1

o

-

9 28 9

Z

l

6 6

1 65 13 32 4

123 93 43 77 101

9 56 10 4 2

2 53 1 8 -

25 104 5 1 _

- 5 1 2 -

47 75 44 13 5

4 43 1 2

3 29 7 6 ..

1 19 1 8 _

24 286 13 50

Record

5

24

34

10

59

12

10

18

33

221

26

48

81

6

58

33

30

49

342 2

Agreement. 23

Other trade industries 2 - 5 — i —

Public service (not

elsewhere classified) 36 1 37 5 24 1

Six pages Page 5

White and Negro Males 10 Years Old and Over Engaged in Gainful

Occupations, by Industry Groups, for Fauquier, Loudoun,

and Rappahannock Counties, Virginia: 1930

County

Fauquier Loudoun Rappahannock

Recreation and amuse

W h ite N egro W hite N egro W h ite N egro

ment

Other professional and

semiprofessional ser

27 20 21 8 6

vice . . . .

Hotels, restaurants, board

101 18 110 16 21 6

ing houses, etc.

Laundries and cleaning

15 26 10 20 6 2

and pressing shops .

Other domestic and per

2 — 6 3 - -

sonal service 28 139 57 93 2 17

Industry not specified . 78 84 94 80 29 6

Six pages Page 6

Population of Fauquier, Loudoun, and Rappahannock Counties,

Virginia, by Magisterial Districts : 1930

Fauquier County

Cedar Run district

Center district

Lee district .

Marshall district .

Scott district

White Negro

14,797 6,272

1,828 796

3 ,6 6 0 2,053

3 ,079 830

2,798 1,390

3 ,432 1,203

24 Transcript of Record of District Court.

Loudoun County 15,502 4,347

Broad Run district 2,274 549

Jefferson district . . . . 2,329 543

Leesburg district 3,140 866

Lovettsville district 2,375 106

Mercer district . . . . 2,253 1,415

Mount Gilead district . 3,131 868

Rappahannock County 5,839 1,878

Hampton district 1,248 567

Hawthorne district 667 107

Jackson district . . . . 938 426

Piedmont district 1,256 162

Stonewall district 716 264

Wakefield district • 1,014 352

A List of Persons in Loudoun County, Virginia, who have paid

their State Poll Tax for the years 1928, 1929 and 1930

in accordance with the law.

Broad Run District

Adrian Robert E

Adrian W T

Albright D F

Allen Isaiah

Ball Fred Lee

Ball Lester H

Ball W J

Beans Charles E

A

Anderson Frank T

Anderson Joseph E

Ankers George

Armel Lawrence S

* * *

Colored

Allen Lucien

B

Beard Ernest G

Beavers David A

Beavers Jessie M

Benjamin L L

Bond Hattie E

Ankers, Laura B

Ankers Lenora F

Ankers Mahlon A

* *

Arthur James

Benjamin Raymond

Bodine Henry C

Bodine J F

Bodmer T E

Finding of the Court. 25

Capps W R

Colored

Basil Crave

C

Caylor M E Cooksey H S

Caldwell Mary B Caylor Marion F Cornett John W

Carter Robert J Coleman P J Corselius Edward

Carson J Graham Cooksey Cora J Costello W T

* * * * * #

Corum Nat

Colored

Corum Solomon Corum Tennie

[Memorandum . By agreement of parties, the remainder of list

is here omitted, as above indicates the makeup of the entire list

to the letter “ Z ” inclusive. James S. Allen, Clerk.]

Thereupon, to wit, April 24, 1933, said cause comes on to be

heard and is fully heard by the court on the return and answer to

the petition for writ of habeas corpus and the agreement, the

Honorable James A. Lowell, District Judge, sitting, and it is

ordered that the writ of habeas corpus be allowed, the court rul

ing evidence set forth in the agreement to be admissible and

respondent’s exception thereto saved.

On the second day of May, A. D. 1933, the following Finding of

the Court is filed :

FINDING OF THE COURT.

May ‘2, 1933.

On the twenty-fourth day of April, 1933, this cause comes on

to be heard by the court. The respondent offers in evidence the

requisition papers of the Governor of Virginia and the original

warrant of his Excellency Joseph B. Ely, Governor of Massachu

setts, a copy of the latter being attached to the respondent’s

answer and return. These are received and marked, respectively,

“ Exhibits A” and “ B ”. The counsel for the petitioner agrees that

such showing makes a prima facie case and offers an agreement

of the parties, which is made a part of the record. According to

26 Transcript of Record of District Court.

this agreement I rule that the evidence therein mentioned is

admissible and competent in these proceedings, and thereupon

rule that the indictments are void and the requisition of the Gov

ernor of Virginia is not in form. Therefore I direct the entry of

the following order:

Ordered, that the petitioner be discharged; but it being repre

sented to me that the respondent intends to enter his appeal, it is

ordered that the petitioner be remanded to the custody of the

respondent pending final determination on said appeal.

JAMES A. LOWELL.

May 2, 1933. ___________

Thereupon, to wit, May 2, 1933, the following final Order of

Court is entered:

ORDER OF COURT.

May 2, 1933.

Lowell, J. The above-entitled cause having come on for hear

ing on the twenty-fourth day of April 1933, it is now, to wit, May

2, 1933, ordered that the writ of habeas corpus be sustained, and

that the petitioner George Crawford be discharged from custody;

but it being represented to the court that the respondent intends

to take an appeal from this order, it is therefore further ordered

that the petitioner said George Crawford be remanded to the

custody of the respondent pending final decision on said appeal.

By the Court,

JOHN E. GILMAN, Jr.,

j a l , Deputy Clerk.

D .’j. ________

From the foregoing order, a petition for appeal to the United

States Circuit Court of Appeals for the First Circuit is filed by the

respondent on May 2, 1933, and allowed by the court on the

same day.

27

EXHIBIT A—REQUISITION.

Commonwealth of V irginia.

Executive Department.

The Governor of the State of Virginia,

To the Governor of the State of Massachusetts

Whereas, It appears by application, copy of indictment, etc.,

which are hereunto annexed and which I certify to be authentic

and duly authenticated in accordance with the Laws of this State,

that George Crawford stands charged with the crime of murder

which I certify to be a crime under the Laws of this State com

mitted in the County of Loudoun in this State, and it having been

represented to me that he has fled from the justice of this State

and may have taken refuge in the State of Massachusetts

Now Therefore, pursuant to the provisions of the Constitution

and the Laws of the United States in such case made and provided,

I do hereby require that the said George Crawford be apprehended

and delivered to E. S. Adrain and D. H. Cooley who are hereby

authorized to receive and convey him to the State of Virginia, there

to be dealt with according to Law.

In Witness Whereof, I have hereunto signed my name and affixed

the Great Seal of the Commonwealth, at the Capitol in the City of

Richmond, this 18th day of January in the year of our Lord one

thousand nine hundred and thirty-three and in the 157th year of

the Commonwealth.

[seal] Jno . Garland Pollard

By the Governor,

Peter Saunders, Secretary of the Commonwealth.

State of Virginia,

County of Loudoun:

To His Excellency, the Governor of Virginia.

Your petitioner respectfully represents unto your Excellency

that George Crawford charged with the murder in the first degree,

of Agnes B. Ilsley, and Mina Buchner, in the County of Loudoun,

against the County of Loudoun and State of Virgina, against whom

28 Transcript of Record of District Court.

an indictment has been found, a duly attested copy of which indict

ment is hereto annexed; and sworn evidence that the aforesaid

George Crawford is a fugitive from justice is also hereto annexed;

is now in the state of Massachusetts, and his whereabouts are

known.

Your petitioner further respectfully represents that in his opinion

the ends of public justice require that the aforesaid George Craw

ford be brought to this state for trial, at the public expense; that

your petitioner has sufficient evidence to secure the conviction of

the aforesaid George Crawford; and that this petition is not made

for the purpose of collecting a debt or pecuniary mulct, or of remov

ing the alleged fugitive to a foreign jurisdiction with a view there to

serve him with civil process, or for any probate purpose whatever;

that if the requisition applied for be granted the criminal proceed

ings shall not be used for any of said objects; that E. S. Adrain,

Sheriff of Loudoun County, Virginia, and D. H. Cooley, Deputy

Sheriff of Loudoun County, the agents hereinafter requested to be

authorized as agents, are proper persons and have no private

interest in the arrest of George Crawford, and that there is an

affidavit hereto annexed showing that the petition is made in good

faith, the aforesaid George Crawford was in the State at the time

of the commission of the aforesaid crime; and facts concerning

the commission of the crime; and that the officer taking the

affidavits was duly authorized.

Wherefore, your petitioner prays that Your Excellency will issue

immediately, a requisition upon the Governor of said State of

Massachusetts for the apprehension and delivery of the said

George Crawford to E. S. Adrain, Sheriff of Loudoun County, and

D. H. Cooley, Deputy Sheriff of Loudoun County, and that you em

power the said Adrain and Cooley in due form, as the authorized

agent to receive and convey the said George Crawford to the State

of Virginia. John Galleher

Commonwealth Attorney for Loudoun County.

Clerks Office of the Circuit Court of Loudoun County to wit:

I, E. O. Russell, Clerk of the Circuit Court of Loudoun County,

Exhibit A — Requisition. 29

in the State of Virginia, do hereby certify that John Galleher,

whose name is signed to the foregoing petition, states that the

above facts are true to his knowledge and belief, and I do further

certify that John Galleher, whose name is signed to the above

petition, is the Commonwealth’s attorney for the County of Lou

doun, State of Virginia.

Given under my hand and seal of the said Court this 17th day

of January, 1933. E. O. Russell

[seal] Clerk of the Circuit Court of

Loudoun County, Virginia.

State of Virginia, to w it:

I, J. R. H. Alexander, the sole Judge of the Circuit Court of Lou

doun County, in the State aforesaid, certify that E. O. Russell, who

hath given the foregoing certificate, (executed simultaneously here

with) is the Clerk of the said court, qualified according to law,

that his said attestation is in due form, and by the proper officer,

and that the said court is a court with general jurisdiction.

Given under my hand this 17 day of January 1933.

J. R. H. Alexander, Judge.

Commonwealth of Virginia, County of Loudoun, to wit:

In the Circuit Court of Loudoun County at its February Term

in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and

thirty-two:

The grand jurors in and for the body of the County of Loudoun,

State of Virginia, and now attending the Circuit Court of said

County at its February Term in the year nineteen hundred and

thirty-two, upon their oaths do present: That George Crawford,

on the 13th day of January, 1932, in the said County of Loudoun,

in and upon one Agnes B. Ilsley, then and there, feloniously, wil

fully, deliberately and premeditatedly and of his malice afore

thought, did, make an assault; and that the said George Craw

ford, then and there, feloniously, wilfully, deliberately, premedi

tatedly and of his malice aforethought, did strike, hit and beat the

said Agnes B. Ilsley, with a certain blunt instrument, with great

force and violence, in and upon the head, arms, hands, and other

30 Transcript of Record of District Court.

parts of the body of her, the said Agnes B. Ilsley, and then and

there feloniously, wilfully, deliberately, premeditatedly, and of his

malice aforethought, did then and there, in the manner and form

aforesaid, give to the said Agnes B. Ilsley, several mortal strokes,

wounds and bruises in and upon the head, the arms, the hands,

and other parts of the body of her, the said Agnes B. Ilsley, of

which said mortal strokes, wounds and bruises, she, the said Agnes

B. Ilsley, in the County aforesaid, on the 13th day of January,

1932, of the said mortal strokes and bruises aforesaid, instantly

died.

And so the jurors aforesaid, upon their oaths aforesaid, do say

that the said Agnes B. Ilsley, the said George Crawford in manner

and form aforesaid and by the means aforesaid, feloniously, wil

fully, deliberately and premeditatedly, and of his malice afore

thought did kill and murder, against the peace and dignity of the

Commonwealth. John Galleher

Attorney for the Commonwealth

A copy—Teste: E. O. Russell, c. c.

State of Virginia, to w it:

I, E. O. Russell, Clerk of the Circuit Court of Loudoun County, in

the State aforesaid, certify that the foregoing is a true transcript of

the record, in the matter of the indictment of George Crawford

for Felony No. 1 as fully and truly as they now exist among the

records of said Court, and I further certify that J. R. H. Alexander,

whose genuine signature appears to the following certificate, exe

cuted simultaneously herewith, is the sole Judge of the said court,

which is a court with general jurisdiction.

In testimony whereof I hereto set my hand and affix the seal of

said court, this 17th day January 1933.

E. O. Russell Clerk

State of Virginia, to wit:

I, J. R. H. Alexander, the sole Judge of the Circuit Court of Lou

doun County, in the State aforesaid, certify that E. 0. Russell, who

hath given the foregoing certificate, (executed simultaneously here

with) is the Clerk of the said court, qualified according to law, that

Exhibit A — Requisition. 31

his said attestation is in due form, and by the proper officer, and

that the said court is a court with general jurisdiction.

Given under my hand this 17 day of January 1933.

J. R. H. A lexander Judge

Commonwealth of Virginia, County of Loudoun, to w it:

In the Circuit Court of Loudoun County at its February Term

in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and

thirty two.

The grand jurors in and for the body of the County of Lou

doun, State of Virginia, and now attending the Circuit Court of

said County at its February Term in the year nineteen hundred

and thirty-two, upon their oaths do present: That George Craw

ford, on the 13th day of January, 1932, in the said County of Lou

doun, in and upon one Mina Buckner, then and there feloniously,

wilfully, deliberately and premeditatedly and of his malice afore

thought, did, make an assault; and that the said George Craw

ford, then and there, feloniously, wilfully, deliberately, premedi

tatedly and of his malice aforethought, did strike, hit and beat

the said Miss Mina Buckner, with a certain blunt instrument,

with great force and violence, in and upon the head, arms, hands

and other parts of the body of her, the said Mina Buckner, and

then and there feloniously, wilfully, deliberately, premeditatedly

and of his malice aforethought, did then and there, in the man

ner and form aforesaid, give to the said Mina Buckner, several

mortal strokes, wounds, and bruises in and upon the head, the

arms, the hands and other parts of the body of her, the said Mina

Buckner, of which said mortal strokes, wounds and bruises, she

the said Mina Buckner, in the County aforesaid, on the 13th

day of January, 1932, of the said mortal strokes and bruises afore

said, instantly died.

And so the jurors aforesaid, upon the oaths aforesaid, do say

that the said Mina Buckner, the said George Crawford in manner

and form aforesaid and by the means aforesaid, feloniously, wil

fully, deliberately and premeditatedly, and of his malice afore

thought, did kill and murder, against the peace and dignity of the

Commonwealth of Virginia.

John Galleher

Attorney for the Commonwealth

A copy—Teste: E. O. Russell c. c.

At a Circuit Court held for Loundoun County,

February Term, 1932.

C. H. Arnold, M. E. Ball, Frank Saunders, George Ankers, Alfred

Dulin, George W. Laycock, T. M. Derflinger, R. Carroll Chinn,

James M. Cole, Walter Leith and Fred S. Warren, having been

sworn a Grand Jury of Inquest for the body of this County and

having received their charge retired to their room and after some

time returned to the County and presented

An indictment against George Crawford for a Felony # 1, a true

bill, Geo. W. Laycock, Foreman.

An indictment against George Crawford for a Felony # 2, a true

bill, Geo. W. Laycock, Foreman.

A copy—teste: E. O. Russell c . c .

State of Virginia, to w it:

I, E. O. Russell, Clerk of the Circuit Court of Loudoun County,

in the State aforesaid, certify that the foregoing is a true tran

script of the record, in the matter of the indictment of George

Crawford for Felony No. 2 as fully and truly as they now exist

among the records of said Court, and I further certify that J. R.

H. Alexander, whose genuine signature appears to the following

certificate, executed simultaneously herewith, is the sole Judge of

the said court, which is a court with general jurisdiction.

In testimony whereof I hereto set my hand and affix the seal of

said court, this 17 day January 1933.

E. O. Russell Clerk

State of Virginia, to w it:

I, J. R. H. Alexander, the sole Judge of the Circuit Court of

Loudoun County, in the State aforesaid, certify that E. O. Russell,

who hath given the foregoing certificate, (executed simultaneously

herewith) is the Clerk of the said court, qualified according to

32 Transcript of Record of District Court.

Exhibit B — Warrant. 33

law, that his said attestation is in due form, and by the proper

officer, and that the said court is a court with general jurisdiction.

Given under my hand this 17 day of January 1933

J. R. H. A lexander Judge

The Commonwealth of Virginia,

To the Sheriff of the County of Loudoun, Greeting :

We command you, That you do not omit for any liberty in

your bailiwick, but that you take George Crawford if he be found

within the same, and him safely keep, so that you have his body

before the Judge of our Circuit Court for Loudoun County, at the

Court-house, on the 13 day of February, 1933, to answer us of a

certain felony made against him in the said Court, on the 8th day

of February, 1932 by the Grand Jury for Loudoun County and

have then there this writ.

Witness, E. 0. Russell, Clerk of our said Court, the 17 day of

February, 1933, in the 157 year of the Commonwealth.

E. O. Russell Clerk

EXHIBIT B-WARRANT.

[Memorandum . Copy of warrant is here omitted, as it already

appears printed on page 7 and returns on same on page 10 of

this transcript of record. James S. A llen, Clerk.]

An additional return on warrant—Exhibit B—is as follows :

Suffolk ss Feb. 27, 1933

At 2 o’clock p. M. this day I appeared before the District Court

of the United States holden at Boston, within and for the Massa

chusetts District, Justice McClellan presiding, to show cause, if

any, I have, why a writ of habeas corpus should not issue for the

body of George Crawford, as prayed for in his petition. The mat

ter was continued until Monday, March 13, 1933 for a hearing.

Frank G. Hale ,

State Police Officer.

34 Transcript of Record of District Court.

RESPONDENT’S PETITION FOR APPEAL

A N D

ASSIGNMENT OF ERRORS.

[Filed May 2, 1933.]

To the Honorable the Judge of the District Court of the United States

for the District of Massachusetts:

Now comes Frank G. Hale, the respondent in the above-entitled

cause, and claims his appeal, to the United States Court of Appeals

for this circuit, from the decision and order in said cause made by

this court, (Lowell, J.), ordering the discharge of the petitioner.

By his Attorneys,

JOSEPH E. WARNER,

Attorney General,

S. D. BACIGALUPO,

Assistant Attorney General of Massachusetts.

May 2, 1933. Appeal allowed.

James A. Lowell,

United States District Judge.

ASSIGNMENT OF ERRORS.

As errors committed in said decision, the respondent alleges

the following, to w it:

1. That the court erred in ruling that the evidence contained in

the agreement of the parties was admissible in these proceedings.

2. That the court erred in admitting the facts stated in the

agreement of the parties in evidence in these proceedings.

3. That the court erred in ruling that the statements contained

in the agreement of the parties were competent evidence in these

proceedings.

4. That the court erred in finding that the indictments in Ex

hibit A were void.

5. That the court erred in ruling that the indictments in Ex

hibit A were void.

6. That the court erred in ruling that the requisition of the

governor of Virginia (Exhibit A) was not in form.

Praecipe. 35

7. That the court erred in ruling that the petitioner was unlaw

fully restrained of his liberty by the respondent.

8. That the court erred in making judicial inquiry into the

manner in which the administrative functions were performed in

the selection of the grand jurors who returned the indictments in

question.

9. That the court erred in ruling as a matter of law that the

indictments were not in sufficient form for the purposes of the

requisition.

10. That the court erred in ruling that the warrant of the

executive of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts was issued in

violation of the provisions of the Constitution of the United States

in such case made and provided.

11. That the court erred in ruling, in substance, that the peti

tioner is unlawfully restrained of his liberty and ordering his

discharge.

FRANK G. HALF, Petitioner,

by his Attorneys,

Joseph E. Warner , Attorney General,

S. D. Bacigalupo,

Assistant Attorney General of Massachusetts.

On the fourth day of May, 1933, a waiver of bond on appeal

was filed by the petitioner.___________

PRAECIPE.

[Filed May 11, 1933.]

To the Clerk of the United States District Court.

Sir: Please prepare a transcript of the record, pleadings, pro

ceedings and papers in the above-entitled cause, to be transmitted

to the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the First Circuit,

in the matter of the appeal of the respondent heretofore allowed

herein, and include in such transcript copies of the following

papers and proceedings, to w it:

1. Motion of petitioner to amend petition and amended petition

for writ of habeas corpus with the warrant for arrest attached.

2. Marshal’s return on summons.

36 Transcript of Record of District Court.

3. Answer and return of Frank G. Hale, respondent.

4. Writ of habeas corpus and officer’s return thereon.

5. Agreement filed April 24,1933, with papers annexed—certain

parts of list of poll taxpayers being omitted.

6. Finding of the court, May 2, 1933.

7. Order of court, dated May 2, 1933.

8. Exhibit A—Requisition.

9. Exhibit B—Warrant (note as to omission, as made part of

item 1).

9a. Additional return dated February 27, 1933, on Exhibit B.

10. Respondent’s petition for appeal and assignment of errors.

11. Recital as to waiver of appeal bond.

12. Recital as to issuance of citation and acknowledgement of

service thereon.

13. Necessary recitals.

14. Praecipe.

J. WESTON ALLEN,

BUTLER R. WILSON,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

JOSEPH E. WARNER,

Attorney General of Massachusetts.

STEPHEN D. BACIGALUPO,

Assistant Attorney General.

A citation on appeal was issued on the eighth day of May, A. D.

1933, being made returnable in the United States Circuit Court of

Appeals on the twenty-third day of May, 1933. Service of said

citation on appeal was duly acknowledged by the attorney for the

petitioner. _____ ____

CLERK’S CERTIFICATE.

U nited States of A merica,

District of Massachusetts, ss .

I, James S. Allen, clerk of the District Court of the United States

for the District of Massachusetts, do hereby certify that the fore

going is the transcript of the record on the appeal of Frank G.

Hale, Lieut. Detective Massachusetts State Police, respondent,

Clerk’s Certificate. 37

including true copies of such proofs, entries and papers on file as

have been designated by praecipe in the cause entitled,

No. 4962, C i v i l D o c k e t ,

GEORGE CRAWFORD, P e t i t i o n e r for W r it of H abeas C o r p u s ,

v.

FRANK G. HALE, L i e u t . D e t e c t i v e M a ssa ch usetts S t a t e P olice ,

R e s p o n d e n t ,

in said District Court determined.

And I further certify that transmitted herewith are the originals

of the petition for appeal and the citation on appeal with the

acknowledgment of service thereon.

In testimony whereof, I have hereto set my hand and affixed

the seal of said District Court, at Boston, in said District, this

seventeenth day of May, A. D. 1933.

[ s e a l ] JAMES S. ALLEN, Clerk

/

United States Circuit Court of Appeals

for the First Circuit.

October Term, 1932.

No. 2824.

Frank G. Hale, Lieutenant Detective,

Massachusetts State Police,

Respondent, Appellant,

V .

George Crawford,

Petitioner, Appellee.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE.

J. WESTON ALLEN,

BUTLER R. WILSON.

B O S T O N :

A D D I S O N C . G E T C H E L L & S O N , L A W P R I N T E R S ,

1933.

il

l

INDEX.

Statement of the case

Brief of argument

I. Exclusion of Negroes from a grand jury by

reason of race or color denies to a Negro defen

dant due process of law and the equal protection

of the laws

II. A. The indictments returned by such unconsti

tutional grand jury must be held void on the

application for writ of habeas corpus

B. The petitioner was not charged with crime

within the meaning of the Constitution and

laws of the United States governing extra

dition, and the requisition of the Governor

of Virginia was not in form

III. The petitioner being in custody in violation of

the Constitution and laws of the United States,

the District Court had jurisdiction to grant its

writ of habeas corpus

A. The history of the writ of habeas corpus,

both in England and in this country, shows

that the application of the writ has been con

stantly broadened and the jurisdiction of the

courts in granting the writ constantly ex

tended to conserve and maintain the original

purpose that a man shall not be deprived of

his liberty except upon a lawful charge or

conviction

B. The District Court has jurisdiction to issue

the writ of habeas corpus, to inquire into and

determine whether a person in jail under

color of authority derived from the Federal

Constitution is in custody in violation of the

Constitution, and, if so unlawfully held, to

discharge him

Page

1

9

9

12

13

15

15

2 0

11 IN D EX

C. The allegations of the petition required the

District Court to exercise its jurisdiction to

inquire into the cause of the petitioner’s re

straint, and upon the facts admitted in the

record, to discharge the petitioner

D. If it is contended that the District Court

had discretion as to the time and mode in

which it would determine the issue raised by

the petitioner, Judge Lowell, having exer

cised that discretion to proceed under R.S.

sec. 761, to receive the evidence and deter

mine the issue before him, and having

allowed the petition and discharged Craw

ford, the only question before this Court

upon appeal is whether his decision to pro

ceed and determine the issue before him,

which he had the power to do, was an abuse

of judicial discretion which constitutes re

versible error

IV. The court properly admitted the facts con

tained in the agreement of the parties as compe

tent and material evidence on the issue presented

by the petition for the writ of habeas corpus

V. The cases relied upon by the appellant are dis

tinguishable from the case at bar and cannot

avail the appellant upon the issue before this

Court upon appeal

A. The cases which hold that illegalities in

empaneling the grand jury cannot be con

sidered on habeas corpus

VI. Conclusion

P a g e

24

31

35

41

41

43

IN D EX 111

TABLE OF CASES CITED.

Andrews v. Swartz, 156 U.S. 272

Carter v. Texas, 177 U.S. 442

Cohens v. Virginia, 6 Wheat. 264

Commonwealth v. Dennison, 24 How. (U.S.) 66

Covell v. Heyman, 111 U.S. 176

Frank v. Mangum, 237 U.S. 309

Harkrader v. Wadley, 172 U.S. 148

Harlan v. McGourin, 218 U.S. 442

Henry v. Henkel, 235 U.S. 219

Hyatt v. Corkran, 188 U.S. 691

Iowa-Des Moines Bank v. Bennett, 284 U.S. 239

Kaizo v. Henry, 211 U.S. 146

Lee Gim Bor v. Ferrari, 55 F. (2d) 86

Loney, In re, 134 U.S. 372

Moran, Matter of, 203 U.S. 96

Neagle, Ex parte, 135 U.S. 1

Neagle, In re, 135 U.S. 1 17, 18, 21

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370

New York v. Eno, 155 U.S. 89 21

Pearce v. Texas, 155 U.S. 311

People v. Brady, 56 N.Y. 182

People, ex rel. Whitfield, v. Enright, 191 N.Y. S. 491

Bickey Land & Cattle Co. v. Miller et al., 218 U.S. 258

Page

13, 41

10, 13, 40