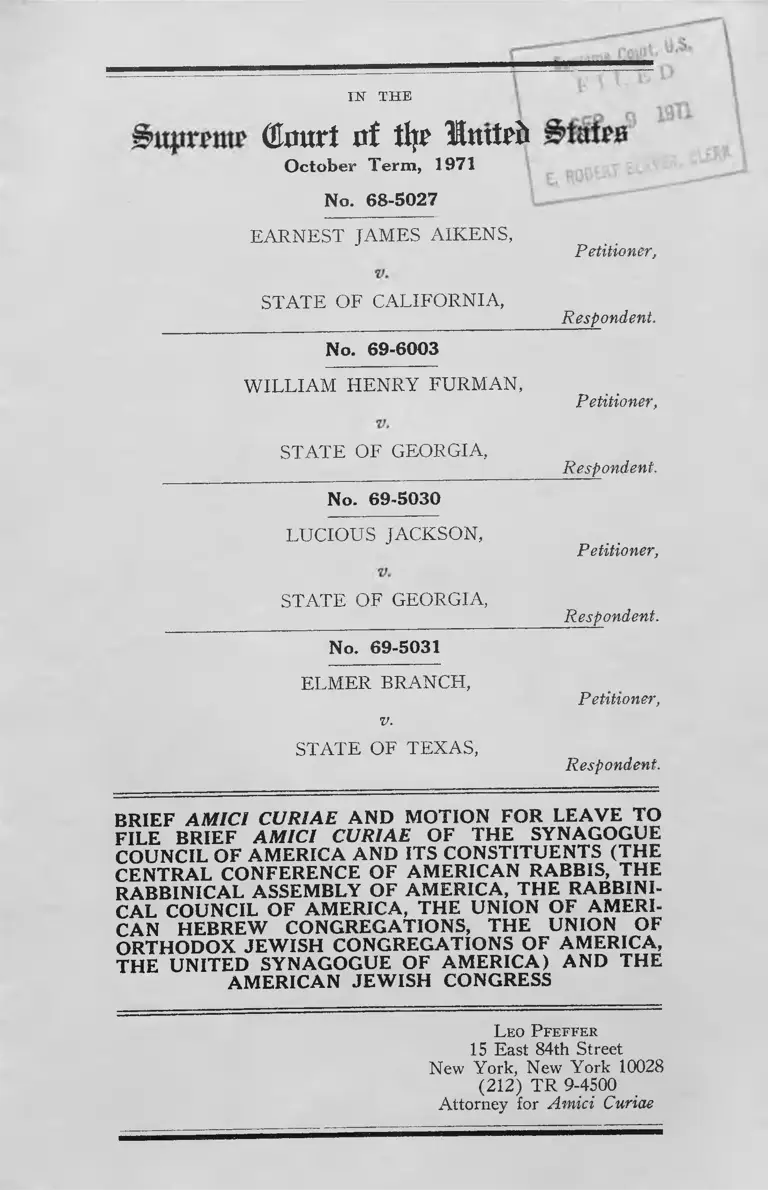

Furman v. Georgia Brief Amici Curiae and Motion for Leave to File Brief of the Synagogue Council of Americans and Its Constituents, et.al

Public Court Documents

September 9, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Furman v. Georgia Brief Amici Curiae and Motion for Leave to File Brief of the Synagogue Council of Americans and Its Constituents, et.al, 1971. 4e19521a-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e3a562a4-4632-4f22-8f82-0d43394b6455/furman-v-georgia-brief-amici-curiae-and-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-of-the-synagogue-council-of-americans-and-its-constituents-etal. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN' THE

(totrt of % Inttrii

October Term, 1971

No. 68-5027

EARNEST JAMES AIKENS,

STATE OF CALIFORNIA,

No. 69-6003

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN,

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Petitioner,

Respondent,

Petitioner,

Respondent,

No. 69-5030

LUCIOUS JACKSON,

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

No. 69-5031

ELMER BRANCH,

v.

STATE OF TEXAS,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE AND MOTION FOR LEAVE TO

FILE BRIEF AM ICI CURIAE OF THE SYNAGOGUE

COUNCIL OF AMERICA AND ITS CONSTITUENTS (THE

CENTRAL CONFERENCE OF AMERICAN RABBIS, THE

RABBINICAL ASSEMBLY OF AMERICA, THE RABBINI

CAL COUNCIL OF AMERICA, THE UNION OF AMERI

CAN HEBREW CONGREGATIONS, THE UNION OF

ORTHODOX JEWISH CONGREGATIONS OF AMERICA,

THE UNITED SYNAGOGUE OF AMERICA) AND THE

AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS

L eo P feffer

15 East 84th Street

New York, New York 10028

(212) TR 9-4500

Attorney for Amici Curiae

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

PAGE

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae............. 1

Brief Amici Curiae....................................................... 3

Interest of the A m ici................................................... 4

Summary of Argument ................................................ 7

Argument

Imposition of the death penalty constitutes

cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the

Eighth Amendment as made applicable to the

states by the Fourteenth, and especially so in

cases of non-homieidal rape ................................. 8

A. The Constitutionality of the Death Penalty

in General ..................................................... 8

B. Applicability of the Eighth Amendment to

the States ..................................................... 10

C. Judicial Responsibility ................................. 11

D. Excessive Punishment as Cruelty ............... 12

E. Inapplicable Standards of Cruelty............... 15

F. Applicable Standards of Cruelty ................. 22

1. The cruelty of deterrent punishment...... 23

2. The cruelty of non-deterrent punishment 25

3. The death penalty as a badge of slavery 29

4. The death penalty and the national con

science ....................................................... 35

5. International standards .......................... 38

Conclusion 40

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Cases:

Adamson v. California, 332 U.8. 46 (1947) ................. 18

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19 (1969) ........... ........................................... 41

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) ............................. 19

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S. 250' (1952) ............. 18

Boykin y. Alabama, 395 U.S. 238 (1969) .................... 9

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 341 (1963) ............... 11, 37

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925) ............. 11,18, 21

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) .......................... 37

Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S.

663 (1966) ............................................................ 41

Jackson v. Bisbop, 404 F. 2d 571 (1968) .................... 12,14

Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184 (1964) ...................... 19, 20

Kemmler, In re, 136 U.S. 436 (1890) ..........................13, 25

Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459

(1947) .........................................................10,16,22,25

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) .......................... 19

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 430 (1961) ............... 37

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262 (1970) ...................... 2, 4

Mar bury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1803) .................11, 22

O’Neil v. Vermont, 144 U.S. 323 (1892) ...................... 13

People v. Oliver, 1 N.Y. 2d 152 (1956) ...................... 10

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) .................... 29

Poe v. Ullman, 367 U.S. 497 (1961) ........................... 37

I l l

PAGE

Ralph v. Warden, 438 F. 2d 786 (C.A. 4, 1971, petition

for certiorari filed, 40 LW 3058 (1971)) ............. 11,13

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962) ........10,11,13,

27, 34

Rocliin v. California, 342 U.S. 165 (1952) ................. 22

Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957) .................18,19

Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 889 (1963) ................... 10

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) ........... 11,13, 22, 23, 26,

29, 35, 38, 42

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910) ......11,12,13,

14,15,16

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1878) .................13,14, 25

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) ............. 9

Sta tu tes:

Bill of Rights (1 W. & M. s. 2, c. 2 (1688) .................11, 21

Federal Crimes Act, 1 Stat. 112 .................................16,17

Nev. Rev. Stat. Sec. 200.363 (1967) ............................ 18

Other Authorities:

Allen, Capital P u n is h m e n t : Y our P rotection and

M in e , in Bedau, 138 .............................................. 30

Ancel^Capital Punishment in the Second Half of the

Twentieth Century, T h e R eview (International

Commission of Jurists, June 1969, 33 ................. 39

Bedau, T h e D eath P enalty in A merica 124 (1967).... 5,15,

28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 36, 39

Bedau, Death Sentences in New Jersey 1907-1960, 19

R utgers L. R ev. 1 (1964) ................................... 30

2 Blackstone, Commentaries 2620 (Jones’ ed. 1916) ....14,17

1 V

PAGE

Calvert, Capital Punishment in the Twentieth Cen

tury, 51 (1928) ............................................... 28

Campion, Does the Death Penalty Protect State Po

lice?, in Sedan, 301 .............................................. 28

Clark, Statement to Subcommittee on Criminal Laws

and Procedures of the United States Senate on

S. 1760, “ To Abolish the Death Penalty,” July 2,

1968 ..................................................... 7,8,28,30,31,36

DiSalle, Capital Punishment and Clemency, 25 Oh io

S tate L.J. 71 (1964) ............................................ 30

Duffy and Hirshberg, 88 M en and W omen 256 (1962) 30

Ehrmann, T h e H um an S ide of Capital P u n is h m e n t ,

in Bedau, p. 510 ..............................................30, 33, 36

Garfinkel, Research Note on Inter- and Intra-Racial

Homicides, 26 S ocial F oeces 369 (1949) ............. 31

Goldberg and Dershowitz, Declaring the Death Pen

alty Unconstitutional, 83 H ae. L. R ev. 1773 (1970) 8

Gottlieb, Capital Punishment, 15 Ceim b and D e l in

quency 1 (1969) ..............................................14, 25, 28

Gottlieb, Testing the Death Penalty, 34 S. Ca lif . L.

R ev. 268 (1961) ..................................................... 8, 10

Graves, The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment

in California, in Bedau, 322 ................................. 28

Holmes, T h e Common L aw (Howe, ed.) 36 (1963) .... 10

Hoover, S tatem ent in F avob of t h e D eath P enalty ,

in Bedau, 130................................................. 5} 28

3 J e w ish E ncyclopedia 554 (1912) ............................ 7

Johnson, The Negro and Crime, 271 Annals 93 (1941) 31

Johnson, Selective Factors in Capital Punishment, 36

S ocial F oeces 165 (1967) 30

V

PAGE

K o en in g e r, Capital Punishment in Texas, 1924-1928,

15 Chim e and D elinquency 141 (1969 ) ... 28, 30, 31, 33

M cC afferty , Major Trends in the TJse of Capital Pun

ishment, F ederal P robation, S ep t. 1961, p p . 15-21 28

M aen am ara , S tatem ent A gainst Capital P u n is h

m e n t , in B ed au , 188 .......................................................... 30, 31

M aim onides, H ilk o th S a n h e d r in .......................................... 6

M arcu s a n d W e isb ro d t, The Death Penalty Cases,

56 Ca lif . L . R ev. 1268 (1968) ........................................ 8 ,1 0

M assach u se tts , Report on the Death Penalty 27 (1958) 28

M attick , The Unexamined Death, 8 (1966) ...................... 28

M endelsohn , Crim in al J urisprudence of th e , A n c ien t

H ebrews 116 ........................................................................ 7

2 M oore, J udaism 186 (1927) ................................................. 6

M ulligan , Death, The Poor Man’s Penalty, T h e A mer

ican W eekly , M ay 15 (1960), p. 9 ............................... 30

M u rra y , S tates L aws on R ace and C olor, S upp .

(1955), p. 6 ............................................................................. 32

M u rto n , Treatment of Condemned Prisoners, 15 Crim e

and D elinquency 96 (1969) ........................................... 31

Ohio, Report on Capital Punishment 49 (1961) ............ 28

Packer ̂ Making the Punishment Fit the Crime, 77

H arv. L . R ev. 1071 (1964) ...............................................12, 24

R eckless, The Use of the Death Penally, 15 Crim e and

D elinquency 43 (1969) ................................................. 8 ,2 8

R oche, “ A P s y c h ia tr is t L ooks a t th e D e a th P e n a l ty ,”

T h e P rison J ournal (Oct. 1958), p . 47 ................. 28

R o y a l C om m ission on C ap ita l P u n ish m e n t, Report

(1953), Secs. 65 et seq......................................................... 28

R ub in , The Supreme Court, Cruel and Unusual Pun

ishment, and the Death Penalty, 15 Crim e and D e

linquency 121 (1969) ...................................................... 8 ,9

VI

PAGE

Savitz, The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment

in Philadelphia, in Bedau, 315 ............................. 28

Scott, A History of Capital Punishment 246' (1950) .... 28

Selim, Does the Death Penalty Protect Municipal

Police?, in Bedau, 284 .......................................... 28

Sellin, Capital Punishment, 135 (1967) ...................... 28

Sellin, The Death Penalty 69 (1959) ..........................10, 28

Talmud, Makkot .......................................................... 6

Talmud, Sanhedrin ................................................. 5, 26, 42

Thomas, Attitudes of Wardens Towards the Death

Penalty, in Bedau, 242 .......................................... 28

United Nations Report, “ Capital Punishment,” (ST/

SOA/SD/9-10) 40 ............................................17, 39, 40

U. S. Department of Justice, “ National Prisoner Sta

tistics, No. 42” (1968, p. 32) ............... 18, 33, 35, 37, 38

Yallenga, Ch bistia nity and t h e D eath P e n a l t y ...... 5

Wolfgang, Kelly and Nolde, E xecutions and Com m u

tations in P ennsylvania , in Bedau, 482 ............. 30, 31

IN' THE

Uupranr (tart at % Imtrti Btntw

O ctober Term , 1971

No. 69-5031

-------------= a s e ^ -B » — ------------

ELMER BRANCH,

v.

STATE OF TEXAS,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF A M IC I CU RIAE

OF THE SYNAGOGUE COUNCIL OF AM ERICA AND ITS

CONSTITUENTS (TH E CENTRAL CONFERENCE OF

AM ERICAN RABBIS, THE RABBINICAL ASSEMBLY OF

AM ERICA, TH E RABBINICAL COUNCIL OF AMERICA,

TH E UNION OF AM ERICAN HEBREW CONGREGA

TIONS, TH E UNION OF ORTHODOX JEW ISH CONGRE

GATIONS OF AMERICA, TH E UNITED SYNAGOGUE OF

AM ERICA) AND THE AM ERICAN JEW ISH CONGRESS

The undersigned as attorney for the amici curiae

herein respectfully moves this Court for leave to file the

attached brief amici curiae in the case of Branch v. State

of Texas, No. 69-5031.

Consent to file this brief amici has been received from

counsel on both sides in Aikens v. California, No. 68-5027,

Jackson v. Georgia, No. 69-5030, and Furman v. Georgia,

No. 69-5003. The Attorney General of Texas, however, has

refused to consent to onr filing this brief in Branch. Ac

cordingly, this motion is made for that purpose.

2

The interest of the amici curiae and the reason for their

making this motion are set forth on pages 4-7 of the an

nexed brief. We respectfully refer the Court thereto.

We note, further, that the amici herein have previously

filed a brief in Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 U. 8. 262 (1970).

However, the issue of the validity of capital punishment

under the Eighth Amendment was not reached in that case

and accordingly we respectfully pray for leave to file the

attached brief.

This brief seeks to introduce a factor which it is believed

is not fully presented in the parties’ briefs. It seeks to

stress that the unacceptability of the death penalty, which

establishes its invalidity under the Eighth Amendment, is

not merely an American phenomenon but one expressing

universal values. This is manifested by the expressions

ranging from the de facto abolition of the death penalty

by the Babbis in Talmudic times two thousand years ago

to the current studies and reports of the United Nations.

We argue that a decent respect for the opinions of mankind

impels a constitutional declaration by this Court that the

law of the land is consistent with the universal unaccepta

bility of the death penalty.

September, 1971

Bespectfully submitted,

LeO' P feffee

15 East 84th Street

New York, New York 10028

(212) TR 9-4500

Attorney for Amici Curiae

IN THE

tour! xti % Inttefc

O ctober Term , 1971

No. 68-5027

EARNEST JAMES AIKENS,

v.

STATE OF CALIFORNIA,

No. 69-6003

Petitioner,

Respondent.

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN,

v.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

No. 69-5030

Petitioner,

Respondent.

LUCIOUS JACKSON,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

__________________________ Respondent.

No. 69-5031

ELMER BRANCH,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF TEXAS,

Respondent.

------------------- — « » -S - B®>— -------------------

BRIEF A M IC I CU RIAE OF THE SYNAGOGUE COUNCIL

OF AM ERICA AND ITS CONSTITUENTS (TH E CENTRAL

CONFERENCE OF AMERICAN RABBIS, THE RABBINI

CAL ASSEMBLY OF AMERICA, THE RABBINICAL

COUNCIL OF AMERICA, THE UNION OF AMERICAN

HEBREW CONGREGATIONS, THE UNION OF ORTHO

DOX JEW ISH CONGREGATIONS OF AMERICA, THE

UNITED SYNAGOGUE OF AM ERICA) AND THE AM ERI

CAN JEW ISH CONGRESS

[3 ]

4

In terest of the Am ici

Four cases bring to this Court for the first time the

direct question of the constitutionality of capital punish

ment. Two of the cases, Aikens v. California, No. 68-5027,

and Furman v. Georgia, No. 69-5003, involve imposition of

the death penalty for murder; in the other two, Jackson v.

Georgia, No. 69-5030, and Branch v. Texas, No. 69-5031,

the death penalty was imposed for non-homicidal rape.

Because the amici, as Jewish religious and civic organiza

tions, have a special interest in the subject of capital pun

ishment and a deep concern regarding the sanctity of hu

man life, they submit this brief amici curiae.* In doing so,

however, they note that this brief is not addressed to the

question of capital punishment for international crimes

such as genocide.

The Synagogue Council of America is the coordinating

body of American Judaism. Its six constituents are the

recognized rabbinic and congregational representatives of

the three branches of American Judaism—Orthodox, Con

servative and Reform.

The American Jewish Congress is an association of

American Jews organized to oppose racial and religious

discrimination and to help preserve democratic values,

principles and practices.

All of the amici are opposed as a matter of principle

to the imposition of the death penalty and support its abo

lition. Their position is based on their judgment as to the

demands of contemporary American democratic standards,

but also has its roots in ancient Jewish tradition. This

statement may seem surprising in view of the many refer-

* The amici filed a brief in Maxwell v. Bishop, 298 U.S. 262

(1970), but the issue was not reached in that case.

5

ences in the Hebrew Bible to the death penalty for such

transgressions as adultery (Lev. 20:21), bestiality (Ex.

22:18), murder (Ex. 21:12) and rape of a betrothed woman

(Deut. 22:15). Indeed, these Scriptural provisions are

often invoked by defenders of capital punishment.1

These statements, however, reflect an unfamiliarity with

the full Jewish tradition, and specifically with the fact that

Rabbinic Judaism during the Talmudic period, some two

thousand years ago, represents the interpretation and im

plementation of the Scriptural command. We can fully un

derstand the Scriptures only through their presentation by

the Oral Law, of which Talmud is the prime exponent.

The definition and the application of the laws of evi

dence and criminal procedure in the Talmud made convic

tion in a capital case practically impossible. Thus, for ex

ample, it is noted that if an accused were to be convicted

in a capital case the verdict could not be unanimous, the

reasoning of the Rabbis being that if not a single one of

the twenty-three judges constituting the court (Sanhedrin)

could find some reason for acquittal there was something

fundamentally wrong with the court. Circumstantial evi

dence was not sufficient to sustain a verdict in a capital

case; two eyewitnesses, subjected to rigorous cross-exami

nation by the court, were required. Moreover, to assure

that the act had been committed with full premeditation,

both witnesses had to testify that they warned the accused

before the crime that the act was prohibited and what its

penal consequences were. (Talmud, Sanhedrin, 40b, et seq.)

1. See e.g., Vellenga, C h r is t ia n it y a nd t h e D e a th P e n a lty ;

in Bedau, T h e D ea th P en a lty in A m erica , 124-125 (1967) (here

inafter referred to as Bedau) ; Hoover, S ta tem en ts in F avor of

t h e D e a th P en a lty , in ibid., 1933.

6

In view of these procedural requirements it is evident

that conviction in a capital case was virtually impossible.2

But perhaps most indicative of the Rabbinic view of cap

ital punishment is the following from the Talmud (Makkot,

Chap. 1, Mishnah 7):

A sanhedrin which executes a criminal once in seven

years is called a “ court of destroyers.” Rabbi Elie-

zer ben Azariah states that this is so even if it exe

cutes one every seventy years. Rabbi Tarphon and

Rabbi Akiba stated that if they had been members of

the sanhedrin no one would ever have been executed.

One Rabbi, Simeon ben Gamliel, expressed a contrary

view, reflecting the most common justification for capital

punishment, namely its deterrent effect. If the views of

Rabbi Tarphon and Akiba were to prevail, he said, “ they

would increase murders in Israel.” However, later com

mentaries note that Rabbi Simeon’s was a minority view

and that the others expressed the normative opinions of

the Rabbis. (Maimonides, Hilkoth Sanhedrin, xiv, xv.)

To take a human life, the Rabbis said, is matter of the

gravest seriousness. Execution is not reversible. If a mis

take is made what has been done cannot be undone. One

who takes a human life, they pointed out, diminishes the

Divine Image. On occasions, this extreme means may be

necessary to protect society. But it may be carried out

only when there can be absolutely no doubt concerning the

guilt of the accused and of his freely chosen, deliberate

and knowing act. In view of human fallibility which is

so pervasive a factor in all judgments, a drastic step such

2. “It is clear that with such a procedure conviction in capital

cases was next to impossible, and that this was the intention of the

framers of the rule is equally plain.” 2 Moore, J uda ism , 186 (1927).

7

as terminating a human life was as a practical matter not

defensible. (See, 3 J ew ish E ncyclopedia 554-558 (1912);

Mendelsohn, Crim inal J urisprudence of t h e A n c ien t

H ebrews, 116-133.)3

Sum m ary of A rgum ent

Under the Eighth Amendment to the Federal Constitu

tion, made applicable to the states by the Fourteenth, a

state may not impose punishment which is cruel or un

usual. The ultimate responsibility of determining whether

punishment is cruel or unusual rests not with the legisla

ture but with the courts, and ultimately of course this

Court. In discharging this responsibility the Court is not

restricted to standards prevailing in 1789 when the Amend

ment was framed but should apply contemporary stand

ards. Nor should these standards be limited by consid

erations of geographic regionalism, but should give weight

to national and even international judgments. Moreover,

it should consider the efficacy or inefficacy of the death

penalty as a deterrent and should give weight to the usual

if not inevitable concomitants of imposition of the death

penalty, such as unequal and racially discriminatory im

position. Measured by these standards the death penalty

constitutes cruel and unusual punishment within the mean

ing of the Eighth Amendment, and certainly so in cases

of non-homicidal rape.

3. It is for this reason that Lafayette vowed to oppose capital

punishment until “the infallibility of human judgment” was demon

strated to him. Quoted in statement by Attorney General Ramsey

Clark before Subcommittee on Criminal Laws and Procedures of the

United States Senate on S. 1760, To Abolish the Death Penalty, July

2, 1968 (hereinafter referred to as Statement on S. 1760).

8

A R G U M E N T

Im position of the death penalty constitutes cruel

and unusual punishm ent in v iolation of the E ighth

A m endm ent as m ade applicable to the states by the

F ourteenth , and especially so in cases of non-hom icidal

rape,

A. T he Constitutionality of th e D eath Penalty in G eneral

The unconstitutionality of the death sentence in all cases

is being increasingly suggested among legal writers,4 not

merely under the Eighth Amendment hut as a denial of

due pi’ocess. Under the former it has been suggested that

contemporary scientific knowledge, not available in 1791

but requiring judicial recognition,5 establishes that all

methods of execution of humans in use in the world today

(hanging, shooting, beheading, stoning, electrocution and

gas asphyxiation)6 are physically and psychologically pain

ful to the extent of being cruel and inhumane. Marcus and

Weisbrodt, The Death Penalty Cases, 56 Ca lif . L. E ev.

1268, 1326-1343 (1968). It has been urged too that, as the

then Attorney General of the United States stated in 1968,

“ Surely the abolition of the death penalty is a major mile

stone in the long road from barbarism,”7 and that accord-

4. Rubin, The Supreme Court, Cruel and Unusual Punishment,

and the Death Penalty, 15 Cr im e and D e l in q u e n c y 121 (1969) ;

Marcus and Weisbrodt, The Death Penalty Cases, 56 Ca l if . L. R ev .

1268 (1968) ; Gottlieb, Testing the Death Penalty, 34 S. Ca l if . L.R.

268 (1961) ; Goldberg and Dershowitz, Declaring The Death Penalty

Unconstitutional, 83 H ar. L. R ev. 1773 (1970).

5. Cf. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

6. Reckless, The Use of the Death Penalty, 15 Cr im e and D e

l in q u e n c y 43, 46 (1969).

7. Statement on S. 1760.

9

ingly by contemporary standards this Court can and should

declare capital punishment to be unconstitutionally cruel

and inhumane in all cases. (See Point II of Brief Amicus

Curiae of the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and the National Office for the Rights of the

Indigent in Boykin v. Alabama, 395 U.S. 238 (1969).)

It may also be suggested that, as will be indicated be

low (pp. 37-38), actual consummation of the death pen

alty even when it is imposed has become so rare that

de facto if not de jure it has become “ unusual” within the

context of the Eighth Amendment and that the Court

should declare it so.

The due process argument has been predicated on the

claim that execution of the death penalty renders due proc

ess of law inoperable. “ When the condemned man is exe

cuted, errors in the proceedings are placed beyond the reach

of later decisions that would provide new grounds for ex

amining whether the proceedings leading to the execution

contained error.” Rubin, The Supreme Court, Cruel and

Unusual Punishment and the Death Penalty, 15 Crim e and

D elinquency 121, 130 (1969). Thus, for example, in

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) the Court held

that a jury from which persons not believing in the death

penalty were excluded was not representative of the com

munity and therefore constitutionally impermissible. The

Court held this principle to be retroactive and hence ap

plicable to all persons in death rows all over the country.

But as to those who have already been executed reopen

ing and retrial is of course impossible and therefore the

inevitable result is that they have been deprived of their

lives without due process of law.

10

Finally, an argument has been made which encompasses

both due process and the Eighth Amendment, an argument

suggested by Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962),

that the death penalty is not rationally related to any pur

pose that an American government may constitutionally

seek to achieve. The traditional purposes of punishment

have been retribution, deterrence, reform, and isolation for

the protection of the community. Rudolph v. Alabama, 375

U.S. 889 (1963), dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Gold

berg; Holmes, T h e C ommon L aw (Howe, ed.) 36 (1963).

Retribution, it is asserted, is today no longer a valid gov

ernmental interest.8 Capital punishment, as will be indi

cated more fully below, is overwhelmingly adjudged by

competent students not to be demonstrably more effectual

as a deterrent than life or long-term imprisonment. Ref

ormation is of course impossible, and isolation can be ef

fectively achieved by confinement. Gottlieb, Testing the

Death Penalty, 34 S. Ca lif . L . R ev. 268 (1961); Sellin, The

Death Penalty 69-79 (1959).9

B. A pplicability of the E ighth A m endm ent to the States

Whatever doubts may have previously existed,10 it is

now clear that the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of

cruel and unusual punishment is applicable to the states

8. “There is no place * * * for punishment for its own sake, the

product of vengeance or retribution.” People v. Oliver, 1 N.Y. 2d

152, 160 (1956). See also Holmes, T h e Com m on L aw (Howe,

ed.) 37 (1963) ; Marcus and Weisbrodt, The Death Penalty Cases,

56 Ca l if . L. R ev. 1268, 1348-1354 (1968).

9. Of course, execution is more economical than life confinement,

but in view of the sanctity of human life it can hardly be contended

that this fact should be determinative.

10. See Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459,

462 (1947).

11

by virtue of the Fourteenth Amendment. Robinson v. Cali

fornia, 370 U.S. 660, 666 (1962); Gideon v. Wainwright, 372

U.S. 341-342 (1963); Ralph v. Warden, 438 F. 2d 786 (C.A.

4, 1971), petition for certiorari filed, 40 LW 3058 (1971).

C. Jud ic ia l Responsibility

Although, as will be indicated more fully below, there

is a steady legislative trend toward the abolition of the

death penalty either altogether or with a few exceptions

(infra, p. 36), a trend which reflects the mandate of the

public conscience, the ultimate responsibility of determin

ing what constitutes cruel and unusual punishment within

the meaning of the Eighth Amendment rests not with the

legislature but with the courts, and particularly this Court.

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 103 (1958); Robinson v. Cali

fornia, supra. Representative Livermore stated this clearly

and succinctly in arguing against the Amendment in Con

gress : “ It lays with the court to determine.” (Cong. Reg

ister 225, quoted in Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. at

369). As we indicate below (p. 18), Gitlow v. New York,

268 U.S. 652 (1925) and the innumerable cases following

it, hold that the effect of the Fourteenth Amendment is to

universalize the Bill of Rights and to require all states and

localities to adhere to national standards of freedom, jus

tice and equality. Whether or not the fifth section of that

Amendment empowers the Congress to forbid capital pun

ishment by the states, its failure to act cannot, unless Mar

burg v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1803) no longer has any

meaning, affect the ultimate responsibility of this Court

to interpret and apply the Bill of Rights nationally.

12

D. Excessive Punishm ent as C ruelty11

Rather surprisingly it has been urged that the intent

of the Eighth Amendment is solely to forbid cruel and in

humane methods of punishment such as torture or burn

ing at the stake, but not to forbid punishments which are

wholly disproportionate to the offense committed. Weems

v. United States, 217 U.8. 349, 382 (1910) (dissenting opin

ion) ; Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Crime, 77

H abv. L. R ev. 1071, 1074-1075 (1964). This is surprising

because it would forbid flogging a person who committed

petty larceny12 or even fining him excessively (since the

Amendment specifically prohibits excessive fines),13 but not

imprisoning him for life or even hanging him for it.14

It is difficult to believe that the framers and adopters

of the Amendment were concerned only about dispropor

tionate monetary punishment but not other and more seri

ous forms of disproportionate punishment.

In any event, the issue is no longer open to question;

it is clear today that punishments which are excessively

disproportionate to the crimes for which they are imposed

11. This Section of our Brief pertains only to Jackson v. Georgia

and Branch v. Texas.

12. Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F.2d 571 (1968).

13. The Eighth Amendment was taken bodily from the English

Bill of Rights of 1688 (1 W. & M. s. 2, c. 2). The earliest applica

tion of the provisions in England appears to have been in 1689, just

a year after its adoption, in a case in which the King’s Bench fined

Lord Devonshire thirty thousand pounds for an assault and battery

upon Colonel Culpepper. The House of Lords, in reviewing the case,

took the opinion of the law Lords, and decided that the fine “was

excessive and exorbitant, against Magna Charta, the common right

of the subject and the law of the land.” Weems v. United States,

supra, 217 U.S. at 376.

14. See below footnote 23.

13

are cruel and unusual within the meaning of the Amend

ment. Weems v. United States, supra-, Robinson v. Cali

fornia, supra-, Ralph v. Warden, supra, I t follows from

this that even if the Court cannot find that there is no un-

cruel or humane method of execution of the death pen

alty15 and is not prepared at present to hold that the death

penalty is in all cases disproportionate to all crimes even

those resulting in death, it can, and we submit should hold

that it is unconstitutionally disproportionate to the crime

of rape which does not result in death.

In discharging its responsibility of interpreting and ap

plying the Eighth Amendment the Court is not confined

to the standards prevailing in 1789 when the Amendment

was framed. “ [T]he words of the Amendment are not

precise * # * their scope is not static.” Trop v. Dulles, 356

U.S. at 100-101. Even when the Amendment was debated

in Congress on its introduction it was recognized that fu

ture courts would give different meanings to the term

“ cruel.” Representative Livermore opposed the Amend

ment for exactly that reason, stating:

^ The clause seems to express a great deal of hu

manity, on which account I have no objection to it;

but as it seems to have no meaning in it, I do not think

it necessary. What is meant by the terms excessive

bail? Who are to be the judges? What is understood

by excessive fines? It lays with the court to deter

mine ; it is sometimes necessary to hang a man, villains

often deserve whipping, and perhaps having their ears

cut off; but are we, in future, to be prevented from

inflicting these punishments because they are cruel?

15. Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1878) (statute authorized

trial judge option of sentencing death by shooting, hanging or be

heading; Court held shooting is not cruel and unusual) ; In re

Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436 (1890) (death by electrocution not cruel

and unusual). See also O’Neil v. Vermont, 144 U.S. 323 (1892).

14

If a more lenient mode of correcting vice and deter

ring others from the commission of it could be in

vented, it would be very prudent in the legislature to

adopt it, but until we have some security that this will

be done, we ought not to be restrained from, making

necessary laws by any declaration of this kind. (Cong.

Register 225, quoted in Weems v. United States, 217

XJ.S. at 369).16

Livermore spoke of cutting off the ears of criminals,

but lest it be assumed that this was merely the product of

his imagination, it should be noted that the Constitution

itself, or more specifically the Fifth Amendment, appears

to contemplate the acceptability of dismemberment as a

method of punishment. The Amendment provides that no

person shall “ be subject for the same offense to be twice

put in jeopardy of life or limb,” thus implying the pro

priety of being once put in jeopardy of limb.17 Blackstone

refers to drawing and quartering, disemboweling, behead

ing and branding as forms of punishment practiced in Eng

land, notwithstanding the Bill of Rights of 1688, up to a

time contemporary with the framing of the Eighth Amend

ment.18 Can it be doubted that no American court would

today sanction these methods of punishment in the face

of the Eighth Amendment?19

16. It is interesting to note that Livermore apparently anticipated

a time when hanging, and presumably all other methods of executing

the death penalty, would be adjudged unconstitutionally cruel.

17. Gottlieb, Capital Punishment, 15 Cr im e and D e lin q u en c y

1, 20 1969).

18. 2 Blackstone, Co m m en ta r ies , 2620-23 (Jones’ ed. 1916).

Whipping, held violative of the Eighth Amendment in Jackson v.

Bishop, 404 F. 2d 571 (1968), was specifically prescribed as punish

ment for a variety of offenses in the first Federal Crimes Act, 1 Stat.

112-117.

19. See, Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130, 135-136 (1878).

15

E. Inapplicable Standards of Cruelty20

As we have indicated, the Amendment addresses itself

not only to the method of punishment bat to its propor

tionateness as well It no more immunizes from future

judicial review punishment deemed in 1789 not to be dis

proportionate or excessive by the standards then prevail

ing than it immunizes punishments then acceptable in

method or mode of execution. As late as 1837, more than

twenty-five offenses, including stealing bank notes, forgery

and bigamy were punishable by death in North Carolina..21

In England, it was not until 1810 that the law making pick

ing pockets a capital offense was repealed.22 The Crimes

Act of 1790 (1 Stat. 112-117), the first Federal penal code,

made forging or passing forged public securities punish

able by death.

It is inconceivable that this Court would today allow

the death penalty to be imposed for these crimes although

they were apparently acceptable to the generation that

framed and adopted the Eighth Amendment. That Amend

ment did not fossilize forever the standards of humane

conduct prevailing in the 18th century. The matter has

been"well put by the Court in Weems v. United States (217

U.S. at 373):

Legislation, both statutory and constitutional, is

enacted, it is true, from an experience of evils, but its

general language should not, therefore, be necessarily

20. This Section of our Brief pertains particularly to Jackson v.

Georgia and Branch v. Texas.

21. Bedau, 7. This harsh code persisted so long in North Caro

lina partly because the state had no penitentiary and thus had no

suitable alternative to the death penalty. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

16

confined to the form that evil had theretofore taken.

Time works changes, brings into existence new condi

tions and purposes. Therefore a principle to be vital

must be capable of wider application than the mischief

which gave it birth. This is peculiarly true of consti

tutions. They are not ephemeral enactments, designed

to meet passing occasions. They are, to use the words

of Chief Justice Marshall, “ designed to approach im

mortality as nearly as human institutions can approach

it. ’ ’ The future is their ease and provision for events

of good and bad tendencies of which no prophecy can

be made. In the application of a constitution, there

fore, our contemplation cannot be only of what has

been but of what may be. Under any other rule a con

stitution would indeed be as easy of application as it

would be deficient in efficacy and power. Its general

principles would have little value and be converted by

precedent into impotent and lifeless formulas. Eights

declared in words might be lost in reality. And this

has been recognized. The meaning and vitality of the

Constitution have developed against narrow and re

strictive construction. * * *

The conclusion to be drawn from this is that the fact

that death was deemed a constitutionally acceptable pen

alty for rape in 1789 when the Eighth Amendment was

framed, or 1868 when the Fourteenth Amendment was

adopted or even in 1947 when Louisiana ex rel. Francis v.

Resweber was decided by this Court, does not require the

Court to hold today that it is constitutionally acceptable

and not violative of the Eighth Amendment. As the Court

said in Weems (217 U.S. at 378), “ The clause of the Con

stitution * # * may therefore be progressive, and is not

fastened to the obsolete, but may acquire meaning as pub

lic opinion becomes enlightened by a humane justice.”

17

Nor is the Court precluded from adjudging the death

penalty to he unconstitutionally inappropriate or excessive

by reason of the fact that the legislature has expressly or

implicitly found it to be efficacious as a deterrent. As we

will show below (p. 27), the scientific evidence is almost

unanimously to the contrary; but even if that were not so,

the Eighth Amendment does not except from its prohibi

tion such cruel and inhumane punishment as effectively

deters others from committing the same crime. If it did,

there would be nothing left of the Amendment, for the

more cruel the punishment the more effective it would be

as a deterrent. Concecledly, the state has an interest in

deterring murder and rape. But so too does it have an

interest in deterring forgery, embezzlement, petty larceny

and even traffic violations, and that interest would hardly

constitutionally justify imposition of the death penalty for

those offenses.23

Today, 17 states and the District of Columbia maintain

in their statutes the death penalty for rape.24 All but one

23. “But, indeed, were capital punishments proved by experience

to be a sure and effectual remedy, that would not prove the necessity

* * * of inflicting them upon all occasions when other expedients fail.

I fear this reasoning would extend a great deal too far. For instance,

the damage done to our public road by loaded wagons is universally

allowed, and many laws have been made to prevent i t ; none of which

have hitherto proved effectual. But it does not therefore follow that

it would be just for the legislature to inflict death upon every obsti

nate carrier who defeats or eludes the provisions of former statutes

* * *” 2 Blacktone’s Commentaries, 2164-65. (It should be noted,

incidentally, that this quotation effectively disposes of the claim that

the term “cruel and unusual” as used in the Bill of Rights of 1688

contemplated only the method of punishment and not its appropriate

ness or excessiveness.)

24. The states are Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Geor

gia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada,

North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and

Virginia. Bedau, p. 43; United Nations Report, Capital Punishment

18

(Nevada) are southern states.25 The death penalty for rape

can therefore truly be said to be a regional or geographic

phenomenon. But, we submit, a geographic or regional

variation cannot restrict the Court’s exercise of judgment

in construing and applying the Eighth Amendment any

more than the First or Fourteenth. Indeed, whether or

not it was the intent of the framers of the latter amend

ment to incorporate the first ten,28 the practical effectuation

of the same result through the steady process of selective

incorporation initiated in Gitlow v. New York, supra, mani

fests a strong judicial policy towards nationalizing the Bill

of Bights. During the almost half-century since Gitlow, the

personnel of the Court has undergone many changes; it has

included such staunch defenders of federalism as Mr. Jus

tice Frankfurter. Yet, during the entire period the prog

ress towards nationalization has not been stayed and cer

tainly not been reversed; not a single decision holding

applicable to the states by virtue of the Fourteenth Amend

ment a right secured in the first ten has been overruled by

the Court or even modified to the extent of according

greater liberality to the states in interpreting the scope of

the right.27

(ST/SOA/SD/9-10), p. 40 (hereinafter referred to as UN Report).

The latter includes West Virginia but in 196S, after the UN compi

lation, that state abolished capital punishment in all cases. United

States Department of Justice, National Prisoner Statistics, No. 42,

June, 1968, p. 32 (hereinafter referred to as N PS). In Nevada, rape

is punishable by death only where committed with substantial bodily

harm to the victim. Nev. Rev. Stat. Sec. 200.363 (1967).

25. So classified by the Department of Justice. NPS, p. 9.

26. See Adamson v. California, 332 U.S. 46 (1947) (opinion by

Mr. Justice Reed, concurring opinion by Mr. Justice Frankfurter and

dissenting opinion by Mr. Justice Black).

27. As suggested by Mr. Justice Jackson in Beauharnais v. Illi

nois, 343 U.S. 250, 288-295 (1952) and Mr. Justice Harlan in Roth

v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957).

19

The principle underlying Gitlow and its successors is

that we are one indivisible nation with liberty and justice

for all, and not merely for those fortunate enough to re

side in some rather than other regions of the country. It

is the principle that where the fundamental freedoms of the

Bill of Bights are concerned (one of which Is the freedom

from cruelly excessive punishments) accidents of geog

raphy are irrelevant. So long as we are one nation, it is

unacceptable that the right of a man, even a rapist, to live

should depend on whether he committed the offense five

feet north or five feet south of the Mason-Dixon line.

It is not merely in the many incorporation cases that

the judicial policy negating geographical factors in apply

ing constitutional freedoms is manifest. In Brown v.

Board of Education, supra, the Court held that a Negro

child attending public school in Topeka, Kansas, has as

much right not to be segregated as his cousin attending

school in Denver or Minneapolis. In Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1 (1967), it held that the right of a Negro and

white to marry each other is not dependent on whether

they live in Richmond or in New York.

The thrust of Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) and

its manifold progeny is that not only the right to vote but

the value of one’s vote may not be made dependent upon

the geographical accident of whether he lives on a farm,

or in a city.

Perhaps most germane is Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S.

184 (1964). In Both v. United States, 354 U.S. 476, 489

(1957), this Court had held that the test for constitutionally

unprotected obscenity is “ whether to the average person,

20

applying contemporary community standards, the dominant

theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to prurient

interests.” In Jacobellis, the Court held that the term

“ community standards” does not imply a determination

of the constitutional question of obscenity in each case by

the standards of the particular community from which the

case arises, but that it refers to national rather than local

standards. What the Court said in Jacobellis is, we submit,

particularly relevant here (378 IT.S. at 194-5):

It is true that local communities throughout the

land are in fact diverse, and that in cases such as this

one the Court is confronted with the task of reconciling

the rights of such communities with the rights of in

dividuals. Communities vary, however, in many re

spects other than their toleration of alleged obscenity,

and such variances have never been considered to re

quire or justify a varying standard for application of

the Federal Constitution. The Court has regularly

been compelled, in reviewing criminal convictions chal

lenged under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, to reconcile the conflicting rights of the

local community which brought the prosecution and of

the individual defendant. Such a task is admittedly

difficult and delicate, but it is inherent in the Court’s

duty of determining whether a particular conviction

worked a deprivation of rights guaranteed by the Fed

eral Constitution. The Court has not shrunk from dis

charging that duty in other areas, and we see no reason

why it should do so here. The Court has explicitly re

fused to tolerate a result whereby “ the constitutional

limits of free expression in the Nation would vary with

state lines,” Pennekamp v. Florida, supra, 323 U.S., at

335, we see even less justification for allowing such

limits to vary with town or county lines. We thus re

affirm the position taken in Both to the effect that the

21

constitutional status of an allegedly obscene work

must be determined on the basis of a national standard.

It is, after all, a national Constitution we are expound

ing. (Emphasis added.)

If a community may not determine for itself what is

obscene, it may not determine what is cruel and unusual.

If restrictive local or regional standards may not determine

the right of an American to speak, it certainly may not,

we submit, determine his right to live.

It may be conceded that these decisions as well as one

that forbids a state to impose the death penalty impinge

somewhat upon federalism strictly construed. But feder

alism, like government, is not an end but a means. We

declared our independence of England because we believed

that governments are instituted among men to secure their

inalienable rights, of which first and foremost is the right

to live, and that when a particular form of government

fails to secure these rights, it is the form of government

and not the rights which must yield.

It is no answer to say that application to particular

geographic regions of national concepts of the meaning of

freedoms secured by the Bill of Rights should be effected

by constitutional amendment rather than court decision, for

it is the teaching of all the post-Gitlow decisions that this

indeed is what was done in 1868. If the Fourteenth Amend

ment means anything, it means that a man’s right to life or

liberty cannot be made dependent upon local or regional

standards but must be judged according to the standards

of the entire nation. It is, after all, a national Constitution

which secures this right.

22

F. A pplicable S tandards of C ruelty

As we have indicated, the ultimate authority to deter

mine what constitutes constitutionally impermissible pun

ishment rests with the courts. This is so because in a

Federal system based upon a written constitution there

must be some single agency which has the final responsi

bility of determining for the whole nation the meaning of

that constitution. Ever since Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch

137 (1803), it has been established that this responsibility

has been delegated to the judiciary. It is therefore the

responsibility of this Court to adjudicate the appropriate

ness of the death penalty today as punishment which is not

cruel and unusual.

In discharging this responsibility, members of the Court

are not left without guides other than their own subjective

predispositions. We do not urge the Court to reverse in the

present cases merely because its members may not like the

idea of a human being deliberately being put to death by

a democratic government. We do not even urge that the

penalty be adjudged unconstitutional because the Court

deems it shocking to their own conscience, although there

is ample authority for this.28 We believe that there are

standards or criteria available to the Court as reasonably

objective as can be expected of a constitutional provision

whose words necessarily “ are not precise.”29

We have heretofore urged rejection of such criteria as

acceptability in 1789 or 1868, effectiveness as a deterrent,

28. See, e.g., Rochin v. California, 342 U.S. 165 (1952); Loui

siana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459, 471 (1947) (con

curring opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter).

29. Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. at 100.

23

and contemporary acceptability in a particular geographic

region. There are, however, other standards or criteria

which are appropriate and it is to these that we now address

ourselves.

Preliminarily, we note that the over-all principle was

expressed by Mr. Chief Justice Warren in his plurality

opinion in Trap v. Dulles (356 U.S. at 101). “ The Amend

ment, ’’ he said, “ must draw its meaning from the evolving

standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing

society.” The criteria we now propose will, we submit,

aid the Court in determining whether the death penalty is

consistent with these “ evolving standards of decency.”

1. The cruelty of deterrent punishment

We have pointed out above (p. 17) that punishment

may be excessive and hence constitutionally cruel even if it

is effective as a deterrent; indeed, we noted, if punishment

is a deterrent the more excessive the punishment the more

likely it is to be effective as a deterrent. The gas chamber

for litterers may be the most effective way of keeping the

streets clean, but that is a price for clean streets the Eighth

Amendment does not permit government in the United

States to pay.

Excessiveness, however, is not limited to non-homieidal

crimes. Certainly, the death penalty for negligently caused

homicide would not be adjudged acceptable today under the

Eighth Amendment. But even in cases of deliberately and

premeditatedly committed murder the Eighth Amendment

is operative. Even Professor Packer30 would not hold that

30. Op. cit. p. 12.

24

in every respect “Making the Punishment Fit the Crime”

accords with Eighth Amendment limitations, else it would

he constitutional to burn homicidal arsonists at the stake.

Those who wrote and those who adopted the Eighth

Amendment undoubtedly shared the common assumption

that punishment was an effective deterrent of crime and

that the more severe the punishment the more effective it

was likely to be as a deterrent. They were aware that

punishments such as torture, burning, disembowelment and

dismemberment had long been deemed acceptable and effi

cacious means of deterring crime. In adopting the Eighth

Amendment they made a deliberate judgment that even

deterrence of homicidal crimes may not be purchased at a

price which violated what they judged to be America’s

standards of civilization and humaneness. Just as they

made the decision that domestic tranquility should not be

purchased at the cost of suppressing dissent, so too they

decided that it should not be purchased at the cost of

humaneness and respect for the sacredness and integrity

of the individual, even if he himself were a cruel and

inhumane murderer.

But, as our quotation from Livermore31 shows, they did

not intend to freeze for all times their own standards of

civilization and humaneness, any more than they were will

ing to accept for themselves the standards of preceding

generations that allowed execution of the death penalty by

means of torture and disembowelment. And, as the same

quotation indicates, they assumed that it would be the

judges in each generation who in the final analysis would

31. Supra, p. 13.

25

determine the limits allowed by contemporary standards of

civilization and humaneness.

This Court has accepted the responsibility of determin

ing whether a particular form of executing the death pen

alty does violence to such standards. WilJcerson v. Utah,

99 U.S. 130; In re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436 (1890); Louisiana

ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 (1947). We sub

mit that it can and should determine whether any form of

executing the death penalty is consistent with our present

standards of civilization and humaneness. If it finds, as we

believe it should, that it is not, it should declare the death

penalty unconstitutionally cruel and unusual in all cases,

even though it also believes that it is an effective deterrent

to homicidal crimes.

2. The cruelty of non-deterrent punishment

The fact that punishment may be unconstitutionally

cruel even if it is effective as a deterrent does not mean that

conversely its noneffectiveness as a deterrent is constitu

tionally irrelevant. We suggest, rather, that punishment

which does not deter and does not serve any valid purpose

at all (such as reformation) or any valid purpose which

cannot effectively be served by less harsh means (such as

isolation) is cruel and inhumane. This is so because its

only purpose is vengeance,32 and vengeance is forbidden by

the Constitution.

32. There is considerable empiric evidence to support the belief

that vengeance is the purpose of the death penalty. Prison authori

ties uniformly search and guard condemned prisoners closely to pre

vent suicide. Should a prisoner in attempting suicide injure himself,

no medical effort is spared to keep him alive for the scheduled execu

tion. Gottlieb, Capital Punishment, 15 Cr im e and D elin q u e n c y 8

(1969). It is apparently not the prisoner’s death but the putting him

26

Mr. Justice Brennan did not join in the Chief Justice’s

plurality opinion in Trop v. Dulles, but he expressed this

principle well in his own concurring opinion. After con

cluding that denationalization for desertion during war

time is ineffective as a deterrent, he stated (356 U.S. at

112):

* * # It cannot be denied that there is implicit in this

a certain rough justice. He who refuses to act as an

American should no longer be an American—what

could be fairer? But I cannot see that this is any-

to death that the state demands. Moreover, the prisoner must be

conscious and sane at the time of the execution. Dr. William F.

Graves, for many years medical officer at San Quentin, made some

fifty visits on death row, examining each condemned inmate to de

termine his physical and mental status and to recommend any treat

ment that might be needed to keep him alive and sane for execution.

Dr. Graves reports as follows regarding one condemned prisoner:

“During his stay in Death Row, McCracken became no more than a

vegetable. On one occasion, I found him wallowing on the floor of

his cell in his own excreta babbling incoherently. I arranged to have

him transferred to the prison hospital where he was given electric

shock therapy—this to bring him to a point of sanity at which he

might be considered able to understand that he was being punished

at the time of his execution.” Ibid.

That this practice is not limited to the United States is shown

by the following from the UN report cited above (at p. 101) : “There

are provisions in the laws of many countries which allow the post

ponement of an execution in the event of either serious physical ill

ness or insanity which appears after sentencing; the execution then

takes place when the condemned man is in good health. Ironically,

this practice sometimes results in the fact that the state expends con

siderable effort and funds to save the life of the man it will then pro

ceed to kill. * * *” All this makes sense only in terms of vengeance;

the culprit must be sane and conscious when the state puts him to

death, else the state’s vengeance would not be full.

The practice in ancient Israel, during the time when capital pun

ishment was still effected, was the reverse. The condemned prisoner

was given wine spiced with frankincense to drink in order to benumb

his senses. Talmud, Sanhedrin 43a.

27

thing other than forcing retribution from the offender

—naked vengeance. * * *

Mr. Justice Brennan did not join in the plurality opin

ion based on the Eighth Amendment presumably because

the Government had ‘ ‘ understandabl [y] * * * not pressed

its case on the basis of expatriation of the deserter as pun

ishment for his crime.” {Ibid.) Had it done so, the tenor

of his opinion and his joinder in the Court’s opinion in

Robinson v. California, supra, indicate quite clearly that

he would likewise have held that non-deterrent, vengeful

punishment is violative of the Eighth Amendment’s pro

hibition of cruel and unusual punishment.

Mr. Justice Brennan pointed out in Trop that because of

the novelty of expatriation as punishment no one can judge

its precise consequences and he accordingly could not rely

on any studies to establish its inefficacy as a deterrent.38

Nevertheless, he concluded that since its efficacy had not

been established, so grave a penalty could not constitu

tionally be imposed by Congress.

In respect to capital punishment, however, substantial

studiesshave been made by competent scholars and their

conclusion is overwhelming that statistical research does

not support the assumption that the death penalty is more

effective as a deterrent than life or long-term imprison

ment and that it is the certainty rather than the gravity

33. He did, however, note that, from the fact that in two-thirds

of the cases of the 21,000 soldiers convicted of desertion during World

War II and sentenced to be dishonorably discharged reviewing au

thorities remitted the dishonorable discharges, “it is possible to infer

that the military itself had no firm belief in the deterrent effects of

expatriation.” 356 U.S. at 112, n. 8.

28

of the punishment that is critical in deterrence.84 (Indeed,

the only contrary assertions are unsupported, impression

istic statements mainly from law enforcement officials.)35

Some of the scholars assert flatly that the death penalty, as

distinguished from imprisonment, is not a deterrent-;36 or

may even have a contrary effect and actually incite com

mission of the very crime it seeks to deter.37 More cautious

scholars say only that there is no evidence to support the

theory that the death penalty is a deterrent superior to

34. Sellin, The Death Penalty, 19-63 (1959) ; Sellin, Capital

Punishment, 135-186 (1967) ; Calvert, Capital Punishment in the

Twentieth Century, 51-90 (1928) ; Mattick, The Unexamined Death,

8-28 (1966) ; Koeninger, Capital Punishment in Texas, 1924-1928,

15 Cr im e and D e l in q u e n c y 131, 141 (1969); Sellin, Does the Death

Penalty Protect Municipal Police? in Bedau, 284; Campion, Does

the Death Penalty Protect State Police? in ibid, 301; Savitz, The

Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment in Philadelphia, in ibid., p.

315; Graves, The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment in Cali

fornia, ibid., p. 322; Royal Commission on Capital Punishment, Re

port (1953), sections 65, 67-68; Reckless, The Use of the Death

Penalty, 15 Cr im e and D e l in q u e n c y 52-56 (1969); McCafferty,

Major Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment, F ederal P roba

t io n , Sept. 1961, pp. 15-21.

35. Hoover, Statements in Favor of the Death Penalty, in Bedau,

130; Allen, Capital Punishment: Your Protection and Mine, id., 135.

But not all law enforcement officials agree. See, e.g., Statement of

Attorney General Ramsey Clark on S. 1760, Dept, of Justice Release,

July 2, 1968. Correction officials, moreover, appear very predomi

nantly to be of the opinion that capital punishment has no significant

deterrent effect; Thomas, Attitudes of Wardens Towards the Death

Penalty, in Bedau, 242; Gottlieb, Capital Punishment, 15 Cr im e and

D e l in q u e n c y 13 (1969).

36. Professor Sellin, for example, has asserted positively that

there is evidence for the view that imprisonment is as good a deter

rent as the death penalty. Bedau, 264. So too has Koeninger,

Capital Punishment in Texas, 15 Cr im e and D elin q u e n c y 132, 141

(1969) ( “The death penalty for murder in Texas has not been a

deterrent.”).

37. Sellin, The Death Penalty (1959), 65-69; Scott, A History

of Capital Punishment (1950), p. 246; Massachusetts, Report on the

Death Penalty (1958), 27-28; Ohio, Report on Capital Punishment

(1961) 49; Roche, “A Psychiatrist Looks at the Death Penalty,”

T h e P rison J ournal (Oct. 1958), p. 47.

29

imprisonment.38 But even accepting the latter view, we

submit, in harmony with Mr. Justice Brennan’s position

in Prop v. Dulles, that where the consequences of a choice

of penalties is so grave, the Constitution requires some evi

dence to support the choice made and does not sanction the

staking of a man’s life on a guess.

In Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), the Court

upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation in the

public schools. In Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 (1954) it reached a contrary conclusion on the basis of

knowledge regarding the harmful effects of segregation not

available when Plessy was decided, and certainly not when

the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted. Today, the Court

has the benefit of knowledge on the inefficacy of the death

penalty as a deterrent not available when the former deci

sions of this Court implicitly (though not directly) held

the penalty to be constitutional. The Court, we submit,

should no more be bound by these decisions today than it

was bound by Plessy in 1954.

In sum, we submit that in the absence of at least some

convincing evidence that the death penalty does actually

deter other crimes to an extent greater than life or long

term imprisonment, the death penalty constitutes cruel and

unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment.

3. The death penalty as a badge of slavery

Every relevant study indicates a strong relation between

the death penalty and poverty; for the crime that sends the

poor man to the death chamber, the well-to-do, if convicted

38. See authorities cited in footnote 34. Bedau sums it up as

follows: “What do all these studies, taken together, seem to show ?

The results are negative; there is no evidence to support the theory

that the death penalty is a deterrent superior to imprisonment for

the crime of murder” (p. 264).

30

at all, is most likely to go to prison. Dean Macnamara of

the New York Institute of Criminology was perhaps over-

dramatic in stating that “ It may be exceedingly difficult

for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven, but case

after case bears witness that it is virtually impossible for

him to enter the execution chamber, ’,S9 but the substantial

truth of the statement is supported by all the authorities,'10

and is conceded even by those favoring retention of capital

punishment.41

The death penalty is not only a function of poverty, it

is also a function of race. There is substantial evidence

and agreement among the authorities that recial discrimina

tion is a significant factor in the imposition and execution

39. Macnamara, S t a tem en t A g a in st Ca pita l P u n is h m e n t ,

in Bedau, 188. See also Ehrmann, T h e H u m a n S id e of Ca pita l

P u n is h m e n t , in Bedau, p. 510. “It is difficult to find cases where

persons of means or social position have been executed. Defendants

indicted for capital offenses who are able to employ expert legal

counsel throughout their trials are almost certain to avoid death

penalties. In the famous Finch-Tregofj case in California, there were

three trials, two hung juries, and finally verdicts of guilty but with

out the death penalty. It is estimated that the cost of these trials

was over $1 million. But in the trial of some defendants without

funds, juries have deliberated for as little as nineteen minutes, or an

hour more or less, and then returned verdicts of guilty and death.”

40. Duffy and Hirshberg, 88 M e n and W o m en (1962), p. 256;

DiSalle, Capital Punishment and Clemency, 25 O h io S tate L.J. 71,

72 (1964) ; Bedau, Death Sentences in New Jersey 1907-1960, 19

R utgers L. R ev . 1 (1964); Johnson, Selective Factors in Capital

Punishment, 36 S ocial F orces 165 (1967); Koeninger, Capital Pun

ishment in Texas, 1924-1968, 15 Cr im e and D e l in q u e n c y 141

(1969) ; Statement of Attorney General Ramsey Clark on S. 1760,

July 2, 1968; Wolfgang, Kelly and Nolde, E x ec u tio n s and Co m

m u ta tio n s in P en n sy lv a n ia , in Bedau, 482-483; Ehrmann, T h e

H u m a n S ide of Ca pita l P u n is h m e n t , in Bedau, 510-511; Mul

ligan, Death, The Poor Man’s Penalty, T h e A m erica n W eek ly ,

May 15, 1960, p. 9.

41. E.g., Allen, Ca pita l P u n is h m e n t : Y our P rotection and

M in e , in Bedau, 138.

31

of the death sentence.42 Attorney General Ramsey Clark

stated quite categorically in testifying' before the Senate

Subcommittee of the Judiciary on S. 1760 (July 2, 1968)

that ‘ ‘ racial discrimination occurs in the administration of

capital punishment. ’ ’ By no means untypical is the follow

ing finding in a study of capital punishment in Texas:

“ In several instances where a white and a Negro were co-

defendants, the white was sentenced to life imprisonment

or a term of years, and the Negro was given the death

penalty. ’,4S

The positive relationship between the death penalty and

race is strong, but where the crime involved is rape and

more particularly, as in two of the present cases, the rape

of white women by Negroes, the relationship is almost un

controvertible. The statistics of the Department of Justice

show that in the United States in the period from 1930 to

1967 although Negroes are only 11 percent of the popula

tion, the percentage of whites and Negroes among those

executed was, respectively, for murder, 49.9 and 48.9; for

crimes other than murder and rape, 55.7 and 44.3; for rape,

10.6 and 8 9.0.44

In 1954, the Court in Brown v. Board of Education,

supra, declared racial segregation in the public schools to

42. Wolfgang, Kelly and Nolde, E x ec u tio n s and Co m m u ta

tio n s in P en n sy lv a n ia , in Bedau, 473-477; Macnamara, State

m en ts A g a in st Ca pita l P u n is h m e n t , in ibid 188; Murton, Treat

ment of Condemned Prisoners, 15 Cr im e and D elin q u en c y 96-97

(1969) • Garfinkel, Research Note on Inter- and Intra-Racial Homi

cides, 26 S ocial F orces 369 (1949) ; Johnson, The Negro and

Crime, 271 Annals 93 (1941). See also authorities cited in footnote

34, supra.

43. Koeninger, Capital Punishment in Texas, 1924-1968, 15

Cr im e and D elin q u e n c y 141 (1969).

44. N.P.S., p. 7. An independent study made of Texas for the

years 1924 to 1965 shows for murder the relative percentages of

whites and Negroes were respectively 36 and 55, while for rape,

they were 14 and 83. Koeninger, Capital Punishment in Texas,

1924-1968, 15 Cr im e and D e l in q u e n c y 140 (1969).

32

be unconstitutional. In 1968 and 1969, the petitioners Jack-

son and Branch were condemned to death for the rape of

white women. A comparison of the states whose statutes

in 1954 required or authorized racial segregation in the

schools and those which in 1969 authorized45 the death pen

alty (and with the exception of West Virginia still do) for

rape is, we believe, of great significance:

Segregation States46 Death Penalty States47

Alabama Alabama

Arizona

Arkansas Arkansas

Delaware Delaware

District of Columbia District of Columbia

Florida Florida

Georgia Georgia

Kansas

Kentucky Kentucky

Louisiana Louisiana

Maryland Maryland

Mississippi Mississippi

Missouri Missouri

Nevada

New Mexico

North Carolina North Carolina

Oklahoma Oklahoma

South Carolina South Carolina

Tennessee Tennessee48

Texas Texas

Virginia Virginia

West Virginia West Virginia

Wyoming

45. In no state is the death sentence for rape mandatory; other

wise a white charged with rape would have to be either acquitted

or, as rarely happens, be sentenced to death. See Bedau, p. 413.

46. Murray, S tates L aw s on R ace and Color, Supp. (1955),

p. 6.

47. Supra, note 24.

48. In 1915, Tennessee abolished capital punishment for all crimes

except rape. Bedau, p. 413.

33

With the exception of Nevada (where the death penalty

is permissible only if the rape is accompanied by substan

tial bodily harm to the victim49 and where in any event the

statute is a dead letter, no person having been executed

under it at least since 1930)50 every state (including the

District of Columbia) which authorises the death penalty

for rape required or authorized racial segregation in the

public schools until it was declared unconstitutional. Con

versely, of the 22 states which required or authorized racial

segregation in the public schools, all but three (Arizona,

Kansas and Wyoming) authorized the death penalty for

rape.

This almost one for one relationship between racial

segregation and death penalty statutes for rape as well as

other statistical and empiric evidence, can be explained in

no other way than in terms of racial discrimination. This

is the practically unanimous conclusion of the competent

scholars who have studied the problem.51 Thus, Koeninger,

reporting on a Texas study, asserts: “ The Negro con

victed of rape is far more likely to get the death penalty

than a term sentence, whereas the whites and Latins are

far more-likely to get a term sentence than the death pen

alty.”52 Bedau states (at p. 413) that

* * * as the National Prison Statistics shows of the

nineteen jurisdictions that have executed men for

rape since 1930, a third of them have executed only

49. Supra, note 24.

50. NPS, p. 11.

51. Bedau, p. 6 0 ; Ehrmann, T h e H u m a n S ide of P u n is h

m e n t , in Bedau, p. 511. See also authorities cited in note 24, supra.

52. 15 Cr im e and D e lin q u en c y 141 (1969).

34

Negroes. In these six states, the very existence of

rape as a crime with optional death penalty is, in the

light of the way it has been used, a strong evidence of

an original intent to discriminate against non-whites.

We recognize that the orders granting certiorari in

these cases limit the issue to the constitutionality of the

death penalty under the Eighth Amendment and do not

extend to any claim under the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth. We suggest, however, that if a white man

found guilty of rape is rarely sentenced to death, or if

sentenced is rarely executed, then the death sentence for

a Negro convicted of the same crime may truly be said to

be an “ unusual” punishment, and hence violative of the

Eighth Amendment. We suggest too another approach.

In Robinson v. California, supra, the Court held that to

punish a person for a status (drug addiction) which he

cannot control violates the Eighth Amendment. The same

reasoning makes violative of the Amendment the imposition

on a person of a penalty harsher than ordinarily imposed

simply because of a status (the color of his skin) which

he cannot control.

While the evidence we have presented herein is most

obvious and dramatic in cases of imposition of the death

penalty for rape, there is, as we have shown, substantial

evidence that by effect if not by purpose the death penalty

falls most heavily on the poor and nonwhite in all cases.

(The petitioners in the two non-rape cases herein are like

wise Negroes.)

Unjust punishment is cruel punishment,53 and unequal

punishment is unjust punishment. It should be so declared

by this Court.

S3. Robinson v. California, supra.

35

4. The death penalty and the national conscience

We have suggested (supra, pp. 18-21) that local or

regional standards are not the appropriate measure to de

termine whether the death penalty constitutes cruel and