Fax from Smiley RE: Congressional primary information

Correspondence

September 29, 1999

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Fax from Smiley RE: Congressional primary information, 1999. 7c39c9ff-fa0e-f011-9989-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e3e39366-73ab-4e58-bf66-bb2c42e002d4/fax-from-smiley-re-congressional-primary-information. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

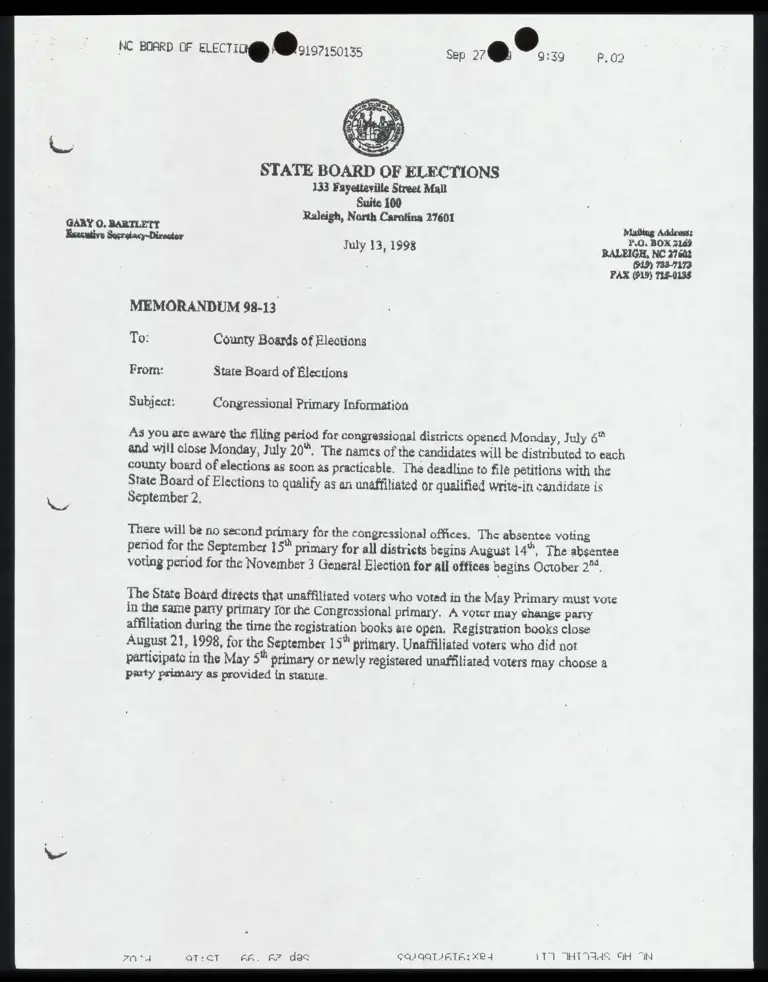

NC BOARD OF acriog) @orsrisosss Sep 7 9:39 P.O2

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

133 Fayetteville Street Mall

Suite 100

Raleigh, North Caralina 27601 GARY O. BARTLETT

Ving sia :

P.0. BOX 3

Haviudben

July 13, 1998 RALEIGH, NC 3742

(519) 7837173

FAX (915) 715.0138

MEMORANDUM 98-13

To: County Boards of Elections

From: State Board of Electjons

Subject: Congressional Primary Information

As you are awars the filing period for congressional districts opened Monday, July 6

and will close Monday, July 20%. The names of the candidates will be distributed to each

county board of elections as zoon as practicable. The deadline to file petitions with the

State Board of Elections to qualify as an unaffiliated or qualified write-in candidate is

a September 2,

There will be no second primary for the congressional offices. The absentee voting

period far the September 15% pnmary for all districts begins August 14%, The absentee

voting period for the November 3 General Election for all offices begins October 2.

The State Board directs that unaffiliated voters who voted in the May Primary must vote

in the same party primary Tor the Congrossional primary. A voter may change party

affiliation during the time the registration books are open. Registration books close

August 21, 1998, for the September 15™ primary. Unaffiliated voters who did not

participats in the May 5% ptimary or newly registered unaffiliated voters may choose a

pacty primary as provided in stature.

5

IN iw pa at:CT EL RZ dat COJAATJRTR: Xe {171 HINAAS oH

State of North Carolina

Department of Justice

P. O. Box 629 MICHAEL F EASLEY

RALEIGH ATTORNEY GENERAL

27602-0629

FAX TRANSMISSION

tdi. Cox

10: lel rac re

2602-62-73 12 FAX NUMBER: _$p¥/-.240- 3235 NO. OF PAGES: &.

FROM: TL ies Stele

TELEPHONE NUMBER: (919) 716-6900 FAX NUMBER: (919) 716-6763

RBIECT: 7 tvicsornte

COMMENTS: __J= &/ 7

CONFIDENTIALITY NOTE

THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS FACSIMILE MESSAGE IS LEGALLY PRIVILEGED AND CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION INTENDED ONLY FOR THE USE OF THE INDIVIDUAL OR ENTITY NAMED ABOVE. IF THE READER OF THIS MESSAGE IS NOT THE INTENDED RECIPIENT, YOU ARE

NOTIFY US BY TELEPHONE AN

VIA THE UNITED STATES POS

\WPGU\SPLIT\FORM\FAX SHT

10°d GI:GT 66. 62 das £94991.616: xe 4 417 TWI3348 94 Oy