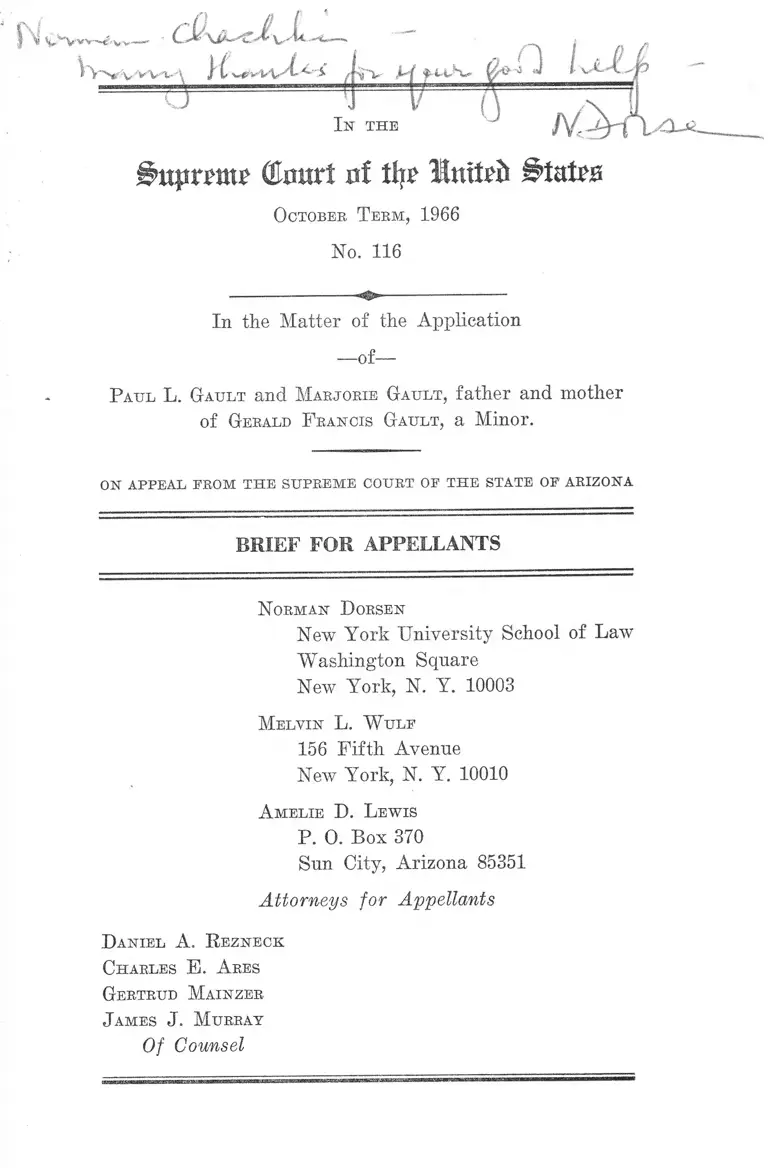

In Re: Paul L. Gault Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. In Re: Paul L. Gault Brief for Appellants, 1966. 2c2ce4eb-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e48341f5-27d2-4f5e-bb53-82714ed0c11c/in-re-paul-l-gault-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

' V ' W ^ V V - ----- . W * " - '

K v

-

f44>V» n / v i i .

I n t h e IV- — ____

.#H|inmtT CÊ nrt nf tin' Inttefr Btvdt&

O ctober T erm , 1966

No. 116

In the Matter of the Application

—of—

P aul L. Gault and M arjorie Ga u lt , father and mother

of Gerald F rancis G ault, a Minor.

ON APPEAL PROM T H E SU PR EM E COURT OE T H E STATE OF ARIZONA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

N orman D orsen

New York University School of Law

Washington Square

New York, N. Y. 10003

M elvin L . W u l f

156 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10010

A m elie D. L ew is

P. O. Box 370

Sun City, Arizona 85351

Attorneys for Appellants

D a n iel A . R ezneck

C harles E. A res

Gertrud M ainzer

J ames J . M urray

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Opinions Below ............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 1

Statutes Involved ........................................................... 2

Question Presented ....................................................... 3

Statement of the Case .......................... 4

Summary of Argument.................................................. 9

A rgum ent

I. The historical background of procedural de

ficiencies in Juvenile Courts............................ 13

II. The Arizona juvenile proceedings failed to

provide Gerald Gault with fundamental pro

cedural protections that are required by the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment .................................................................. 18

A. Notice of Charges and Hearing................. 29

B. The Bight to Counsel ................................ 34

C. Confrontation and Cross-examination ...... 43

D. The Privilege Against Self-Incrimination 50

E. Right to Appellate Review and to a Tran

script of the Proceedings ......................... 58

PAGE

C onclusion 63

11

PAGE

A ppen dix :

Arizona Constitution, Article 6, Section 15 .......... la

Arizona Criminal Code § 13-377 ............................ la

Juvenile Code of Arizona, §§ 8-201 to 8-239 .......... la

T able of A utho rities

Cases:

Akers v. State, 114 Ind. App. 195, 51 N. E. 2d 91 (1943) 16

Application of Gault, 99 Ariz. 181, 407 P. 2d 760 (1965)

passim

Application of Johnson, 178 F. Supp. 155 (D. N. J.

1957) ......................................................................... 24,33

Application of Vigileos, 84 Ariz. 404, 300 P. 2d 116

(1958) ................................................................... 53

Ballard v. State, 192 S. W. 2d 329 (Tex. Civ. App.

1946) ........................................................................... 46

Benson v. U. S., 332 F. 2d 288 (5th Cir. 1964) .............. 22

Black v. U. S., 355 F. 2d 104 (D. C. Cir. 1965) .......... 35, 39

Brewer v. Commonwealth, 283 S. W. 2d 702 (Ky. 1955) 24

Briggs v. U. S., 96 U. S. App. D. C. 392, 226 F. 2d 350

(1955) ......................................................................... 53

Burrows v. State, 38 Ariz. 99, 297 Pac. 1029 (1931) .... 53

Carnley v. Cochran, 369 U. S. 506 (1962) ..................... 43

Caruso v. Superior Court, 100 Ariz. 167, 412 P. 2d 463

(1966)........................................................................... 54

Chewning v. Cunningham, 368 U. S. 443 (1962) ........37-38

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196 (1948) ..................... 29,30

Counselman v. Hitchcock, 142 U. S. 547 (1892) ............ 55

I l l

Dandy v. Wilson, 179 S. W. 2d 269 (Tex. Sup. Ct.

PAGE

1944) ......................................................................... 56,57

Draper v. Washington, 372 U. S. 487 (1963) ................. 62

Ex parte Tahbel, 46 Cal. App. 755, 189 Pac. 804 (1920)

56, 57

Fay y . Noia, 372 IT. S. 391 (1963) ................................ 43

Florence v. Meyers, 9 Race Eel. L. R. 44 (M. D. Fla.

1964) ............................................................... 29

Flynn v. Superior Court, 414 P. 2d 438 (Ariz. Ct. App.

1966) ........................................................................... 53

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S. 335 (1963) ...... 11,34,35,

36, 37

Green v. State, 123 Ind. App. 81, 108 N. E. 2d 647

(1952) .......................................................................... 46

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U. S. 474 (1959) ..................... 45,46

Griffin v. Hay, 10 Race Rel. L. R. I l l (E. D. Ya. 1965) 29

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U. S. 12 (1956) ...... ..................58, 62

Griffin v. State, 380 U. S. 609 (1965) ............................ 51

Hamilton v. Alabama, 368 II. S. 52 (1961) ................. 36

Harris v. Norris, 188 Ga. 610, 4 S. E. 2d 840 (1939) .... 60

Hovey v. Elliot, 167 H. S. 409 (1897) ........................... 29

In Interest of T. W. P., 184 So. 2d 507 (Fla. Ct. of

App. 1966) .................................................................. 16

In re Alexander, 152 Cal. App. 2d 458, 313 P. 2d 182

(1957) ......................................................................... 24

In re Bentley (Harry v. State), 246 Wis. 69, 16 N. W.

2d 390 (1944) 16

In re Contreras, 109 Cal. App. 2d 787, 241 P. 2d 631

(1952) ..........................................................................

In re Coyle, 122 Ind. App. 217, 101 N. E. 2d 192

(1951) ......................................................................... 33-

In re Creely, 70 Cal. App. 2d 186, 160 P. 2d 870 (1945)

In re Davis, 83 A. 2d 590 (Mun. Ct. Apps. D. C.

1951) ...........................................................................

In re Duncan, 107 N. E. 2d 256 (1951) .........................

In re Florance, 47 Cal. 2d 25, 300 P. 2d 825 (1956) ......

In re Holmes, 379 Pa. 599, 109 A. 2d 523 (1954), cert.

denied, 348 U. S. 973 (1955) .....................16,17, 22, 23,

In re Mantell, 157 Neb. 900, 62 N. W. 2d 308, 43 A. L. R.

2d 1122 (1954) .........................................................

In re Murchison, 349 U. S. 133 (1955) ................. 29,60,

In re Oliver, 333 U. S. 257 (1948) ................................

In re Poff, 135 F. Supp. 224 (D. D. C. 1955) .......... 13, 25,

In re Poulin, 100 N. H. 458, 125 A. 2d 672 (1957) ......

In re Ronny, 40 Misc. 2d 194, 242 N. Y. S. 2d 844 (Fam

ily Ct. 1963) ................................................................

In re Roth, 158 Neb. 789, 64 N. W. 2d 799 (1954) ......

In re Sadleir, 97 Utah 291, 85 P. 2d 810 (1938) ..........

In re Santillanes, 47 N. M. 140, 138 P. 2d 503 (1943) .17,

In re Wright, 251 F. Supp. 880 (M. D. Ala. 1965) ......

In the Matter of Gonzalez, 328 S. W. 2d 475 (Tex. Ct.

App. 1959) ..................................................................

Interest of Long, 184 So. 2d 861 (1966) .........................

24

■34

33

57

16

33

57

46

62

29

39

34

26

34

57

,57

29

16

39

43Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 IJ. S. 458 (1938)

Kent v. U. S., 383 H. S. 541 (1966) ....... .9,12,17,19, 25,

35, 36, 54, 59

V

Malloy y . Hogan, 378 U. S. 1 (1964) ............................ 51

Matter of McDonald, 153 A. 2d 651 (D. C. Mnnic. Ct.

App. 1959) .................................................................. 16

Matter of Solberg, 52 N. D. 518, 203 N. W. 898 (1925) 34

McCarthy v. Arndstein, 266 U. S. 34 (1924) .............. 51

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S. 436 (1966) ................. 36

Murphy v. Waterfront Commission, 378 U. S. 52

(1964) ........................................................................12,51

People ex rel. Solemon v. Slattery, 39 N. Y. S. 2d 43

(Sup. Ct. 1942) ........................................................... 60

People v. Dotson, 46 Cal. 2d 891, 299 P. 2d 875 (1956) .. 16

People v. James, 9 N. Y. 2d 82, 211 N. Y. S. 2d 170, 172

N. E. 2d 552 (1961) .............................................. 46,47

People v. Lewis, 260 N. Y. 171, 183 N. E. 353 (1932)

15,17, 58, 59

People v. Silverstein, 121 Cal. App. 2d 140, 262 P. 2d

656 (1953) .................................................................... 17

Petition of O’Leary, 325 Mass. 179, 89 N. E. 2d 769

(1950) ............................................. 34

Pettit v. Engelking, 260 S. W. 2d 613 (Tex. Civ. App.

1953) ........................................................................... 34

Pointer v. Texas, 380 U. S. 400 (1965) .....................43,48

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45 (1932) ..............11,29,34,

35, 37, 38

Eeynolds v. Cochran, 365 U. S. 525 (1961) ................. 37

Shioutakon v. District of Columbia, 236 F. 2d 666 (D. C.

Cir. 1956) .... 35,39

State ex rel. Cave v. Tincher, 258 Mo. 1, 166 S. W. 1028

(1914) ..

PAGE

34

V I

State ex rel. Christensen v. Christensen, 119 Utah 361,

227 P. 2d 760 (1951) ................................ .................. 16

State ex rel. Raddue v. Superior Court, 106 Wash. 619,

180 P. 875 (1919) ....................................................... 16

State v. Andersen, 159 Neb. 601, 68 N. W. 2d 146

(1955) ......................................................................... 34

State v. Chitwood, 73 Ariz. 161, 239 P. 2d 353 (1951),

on rehearing, 73 Ariz. 314, 240 P. 2d 1202 (1952) .... 56

State v. Logan, 87 Fla. 348, 100 So. 173 (1924) .......... 60

State v. Naylor, 207 A. 2d 1 (Del. 1965) ......................... 24

State v. Shardell, 107 Ohio App. 338, 153 N. E. 2d 510

(1958) .......................................................................... 57

Sylvester v. Commonwealth, 253 Mass. 244, 148 N. E.

449 (1925) .................................................................. 16

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 (1960) .... 61

Trimble v. Stone, 187 F. Supp. 483 (D. D. €. 1960) ...... 24

U. S. v. Dickerson, 168 F. Supp. 899 (D. C. 1958), rev’d

on other grounds, 106 U. S. App. D. C. 221, 271 F. 2d

487 (1959) .................................................................. 57

U. S. v. Morales, 233 F. Supp. 160 (D. C. Mont. 1964) .... 24

Von Moltke v. Gillies, 332 U. S. 708 (1948) ................. 43

White v. Maryland, 373 U. S. 59 (1963) ..................... 36

Williams v. Kaiser, 323 U. S. 471 (1945) ......................... 38

Williams v. New York, 337 U. S. 241 (1949) ..............22, 29

Williams v. Zuekert, 371 U. S. 531 (1963) .................... 45

Willner v. Committee on Character & Fitness, 373 U. S.

96 (1963) .................................................................... 45

PAGE

Constitutional Provisions:

United States Constitution

Fifth Amendment ........................................... 36

Fourteenth Amendment ...... 3,13,18, 35,44, 51, 60

Arizona Constitution

Article 2, Section 19 ....................................... 54

Article 6, Section 15 ....................................... 52

Statutes and Rules:

28 U. S. C. §1257(2) ...................................................... 2

Criminal Code of Arizona, Ch. 8, §§13-2001 to 2027,

Arizona Revised Statutes (1956) ................................ 1

Juvenile Code of Arizona, §§8-201 to 8-239, Arizona

Revised Statutes ....................................................passim

Title 4, §245 ................................................ -.................. 56

Title 13, §101, Arizona Revised Statutes ..................... 50

Title 13, §377, Arizona Revised Statutes ..............2, 23, 30,

31, 38, 50, 52

Title 44, §1660 .............................................................. 55-56

California Welfare and Institutions Code (1961)

§§500-914 .................................................................. 27

§§653, 656 ................................................................ 31

§679 ......................................................................... 39

Illinois Laws, 1899, at 131 ........................................... 14

VII

PAGE

V l l l

New York Family Court Act (1962)

§241 .............................................

§711 .............................................

§731 ............................................ .

§741 .............................................

PAGE

... 39

.. 27

.. 31

39, 58

Other Authorities'.

Allen, Criminal Justice, Legal Values and the Re

habilitative Ideal, 50 J. Crim. L. C. and P. S. 226

(1959) ......................................................................... 22

Antieau, Constitutional Rights in Juvenile Courts, 46

Cornell L. Q. 387 (1961) ............... 13,16, 25, 33, 39, 49, 57

Beemsterboer, The Juvenile Court—Benevolence in the

Star Chamber, 50 J. Crim. L. C. and P. S. 464 (1960) 25

Biographical Data Survey of Juvenile Court Judges,

George Washington Univ., Center of Behavioral

Sciences (1964) .................... ..................................... 38

Children’s Bureau, U. S. Dept, of Health, Education &

Welfare, Standards for Juvenile and Family Courts

(1966) ....................................... 14, 27, 33, 41-42, 47, 57, 60

Dembitz, Ferment and Experiment in New York:

Juvenile Cases in the New York Family Court, 48

Cornell L. Q. 499 (1963) .......................................... 25

Glueck, Some “Unfinished Business” in the Manage

ment of Juvenile Delinquency, 15 Syracuse L. Rev.

628 (1964) ....................................... ...........................15,16

IX

Guidebook for Judges, prepared by the Advisory Coun

cil of Judges of the National Council on Crime and

Delinquency ................................................................

Horwitz, The Problem of the Quid pro Quo, 12 Buffalo

L. Rev. 528 (1963) ......................................................

Illinois Legislative Council, Juvenile Court Proceed

ings in Delinquency Cases (1958) ............................

Institute of Judicial Administration, Juvenile Courts—

Jurisdiction (1961) .................................................... 14

Ketcham, Legal Renaissance in the Juvenile Court, 60

Nw. U. L. Rev. 585 (1965) ...... ....................-........25, 27, 39

Mack, The Juvenile Court, 23 Harv. L. Rev. 104

(1909)........................................................................... 15

McCune and Skoler, Juvenile Court Judges in the

United States, 11 Crime & Delinquency 121 (1965) ..-38

McKay, The Right of Confrontation, 1959 Wash.

U. L. R. 122 .............................................................44,46

Meltsner, “Southern Appellate Courts: A Dead End”

in Friedman (ed.), “Southern Justice” 152 (1965) .... 29

Molloy, Juvenile Court—A Labyrinth of Confusion for

the Lawyer, 4 Ariz. L. Rev. 1 (1962) .....................50, 54

National Probation and Parole Association (NPPA)

(now the National Council on Crime and Delin

quency, NCCD), Standard Juvenile Court Act (Rev.

1959), 5 NPPAJ 323 (1959) .......................... 14,27,31,39

NCCD, Standard Family Court Act (1959) .......... 14, 47, 60

Note, Juvenile Courts: Applicability of Constitutional

Safeguards and Rules of Evidence Proceedings, 41

Cornell L. Q. 147 (1955)............................................... 16

PAGE

33

17

X

Note, Juvenile Delinquents: The Police, State Courts

and Individualized Justice, 79 Harv. L. Rev. 775

(1966) .......................................................................... 14

NPPA, Guides for Juvenile Court Judges (1957) ...... 14

Paulsen, Fairness to the Juvenile Offender, 41 Minn.

L. Rev. 547 (1957) ................................... 16, 25, 33, 39, 56

Quick, Constitutional Rights in the Juvenile Court, 12

How. L. J. 76 (1966) .................................................. 25

Radzinowicz and Turner, A Study of Punishment I:

Introductory Essay, 21 Canadian Bar Rev. 91-97

(1943) ......................................................................... 22

Rubin, Protecting the Child in the Juvenile Court, 43

J. Crim. L. C. and P. S. 425 (1952) ......................... 25

Schinitsky, The Role of the Lawyer in Children’s

Court, The Record (The Assn, of the Bar of the City

of New York), Vol. 17, No. 1, Jan., 1962 ................. 39,41

Skoler, Juvenile Courts and Young Lawyers, 10 The

Student Law J. 5 (Dec. 1964) ................................... 25

Starrs, A Sense of Irony in Juvenile Courts, 1 Harv.

Civil Rights—Civil Liberties L. Rev. 129 (1966) ....... 29

Sussman, Juvenile Delinquency (1955) ......... 17

Sussman, Law of Juvenile Delinquency (Rev. ed. 1959) 14

The Interstate Compact on Juveniles: Development

and Operation, 8 J. of Pub. Law 24 (1959) .......... 14

Tompkins, In the Interest of a Child (1959) ................. 14

U. S. Commission on Civil Rights Report, Law En

forcement, 1965 ....................................................... 28

PAGE

X I

Watson, The Child and the Magistrate (England 1965) 57

Welch, Delinquency Proceedings—Fundamental Fair

ness for the Accused in a Quasi-Criminal Forum, 50

PAGE

Minn. L. Rev. 653 (1966) ...........................................13, 25

5 Wigmore, Evidence §1400 (3rd ed., 1940) ............... 44

5 Wigmore, Evidence §1367 (3rd ed., 1940) ................. 45

I n t h e

^uprem? Court of % luttrb ^tatro

October T erm , 1966

No. 116

In the Matter of the Application

—of—

P aul L. Gault and M arjorie Gault, father and mother

of Gerald F rancis Gault, a Minor.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Arizona (R. 83-97)

is reported at 99 Ariz. 181, 407 P. 2d 760. The Superior

Court of Maricopa County, Arizona, from which appeal was

taken, wrote no opinion. The Juvenile Court of Gila County

wrote no opinion; its decision is found in the order of

commitment, dated June 15, 1964, contained in the Record

as Exhibit 4 (R. 81-82).

Jurisdiction

Appellants filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus

in the Supreme Court of Arizona on August 3, 1964, pursu

ant to the provisions of Chapter 8 of the Criminal Code

of the Arizona Revised Statutes (1956), Sections 13-2001-

2027. The same day, the Supreme Court of Arizona

2

ordered a hearing of the application in the Superior Court

of Maricopa County. The hearing was held on August 17,

1964. The Superior Court dismissed the petition, dis

charged the writ, and remanded the juvenile to the State

Industrial School.

The order of the Superior Court was affirmed on appeal

by the Supreme Court of Arizona on November 10, 1965,

and a timely application for rehearing was denied by that

Court on December 16, 1965 (R. 99). Notice of Appeal to

the Supreme Court of the United States was filed with the

Supreme Court of Arizona on February 4, 1966 (R. 100).

On March 21, 1966, Hon. Fred C. Struckmeyer, Chief

Justice of the Supreme Court of Arizona, enlarged appel

lants’ time to file the Jurisdictional Statement and to

docket the appeal to May 5, 1966. The Jurisdictional State

ment was filed on May 2, 1966 and probable jurisdiction

was noted on June 20, 1966. Jurisdiction on appeal is

conferred by 28 U.S.C. §1257(2).

Statutes Involved

Article 6, Section 15 of the Arizona Constitution, the

Juvenile Code of Arizona, Sections 8-201 to 8-239, Arizona

Revised Statutes, and Title 13, Sec. 377, Arizona Revised

Statutes, are set forth in full in the Appendix to this brief.

3

Question Presented

Whether the Juvenile Code of Arizona, Sections 8-201

to 8-239, Arizona Revised Statutes, on its face or as con

strued and applied, is invalid under the Due Process Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution because it authorizes a juvenile to be taken from

the custody of his parents and to be committed to a state

institution by a judicial proceeding which confers unlimited

discretion upon the Juvenile Court and dispenses with the

following procedural safeguards required by due process

of law:

1. right to notice of the charges of delinquency;

2. right to counsel;

3. right to confrontation and cross-examination of ad

verse witnesses;

4. privilege against self-incrimination;

5. right to a transcript of the proceedings; and

6. right to appellate review of the juvenile court’s

decision.

4

Statem ent o f th e Case1

Appellants are the parents of fifteen year old Gerald

Francis Gault who was committed as a juvenile delinquent

to the State Industrial School in Arizona after a juvenile

proceeding in the Superior Court of Gila County, Globe,

Arizona, on June 15,1964. No transcript exists of the hear

ing before the juvenile court.2

On June 8, 1964, Gerald Francis Gault and a friend,

Eonald Lewis, were taken into custody by the Sheriff of

Gila County as the result of a complaint by one Mrs. Cook,

a neighbor of the boys, about lewd telephone calls made

to her. Gerald was at this time on six months’ probation

following an incident in February, 1964 (R. 13). Proba

tion officers Flagg and Henderson decided to detain the

children (R. 48). Mr. Flagg interrogated Gerald at some

length during the evening of June 8th and the morning of

June 9th (R. 48).

No notice of the detention or charges was left at the

Gault home. Mrs. Gault, who returned from work at 6 :Q0

P.M., was informed by neighbors about the detention and

went to the detention home. There she was told by proba

tion officer Flagg why Gerald was detained and that a hear

ing would be held at 3 o’clock the following day, June 9th.

1 The statement of facts is based on the habeas corpus hearing

held on August 17, 1964 in the Superior Court of Maricopa County

after a petition for a writ of habeas corpus had been filed by ap

pellants on August 3, 1964 in the Supreme Court of Arizona to

secure the release of the child. The record of that hearing is part

of the record on appeal.

2 The Arizona statute does not require a record to be made of

juvenile hearings but only of the age, place of birth and name of

the child and his parents (§8-229).

No written notice of the hearing or of the charges was

given to Mrs. Gault (R. 29-30).

A petition charging Gerald with juvenile delinquency was

filed by probation officer Flagg with the Court on June 9,

1964, but Mrs. Gault had not received notice of it and did

not see it until August 17, when the habeas corpus hearing

was held (R. 33). A referral report charging Gerald with

making “lewd phone calls” made by the Probation Depart

ment, filed on June 15, 1964, was also not brought to appel

lants’ notice until August 17th, when introduced by appel

lants’ attorney together with the above mentioned petition

(R. 34).

On June 9th a hearing took place in the Juvenile Judge’s

chambers in the presence of Gerald, his mother, Ms older

brother Louis, and Mr. Flagg and Mr. Henderson, the pro

bation officers. Mr. Gault, Gerald’s father, was in Grand

Canyon at work (R. 20). No one was sworn at this hearing

(R. 30). No transcript was made (R. 54).

Gerald testified at the June 9th hearing about the tele

phone call. There was a conflict at the habeas corpus hear

ing about this testimony. Mrs. Gault testified that Gerald

said he only dialed Mrs. Cook’s number and his friend talked

to Mrs. Cook (R. 30), while Judge McGhee, the Juvenile

Judge (R. 59), and Probation Officer Flagg testified

that Gerald admitted having said some of the lewd words

but not the more serious ones (R. 59). At the conclusion of

the hearing, in answer to a question by Gerald or his mother

if Gerald would be sent to Fort Grant,3 Judge McGhee said:

3 The State Industrial School.

6

“No, I will think it over” (E. 31, 39). Gerald stayed in the

detention home until June 12th when he was released to

his parents. At 5 o’clock that day, Mrs. Gault received a

written note4 signed by Officer Flagg which said: “Mrs.

Gault, Judge McGhee has set Monday, June 15th,

1964 at 11:00 A.M. as the day and time for further hearings

on Gerald’s delinquency.” (Exhibit 1, E. 8.)

At the hearing on June 15th, both appellants were pres

ent, Mr. Gault having returned home on June 12th (E. 21).

Others present at this hearing before Judge McGhee were

Eonald Lewis with his father, and probation officer Flagg.

Mrs. Cook, the person who had complained about the

phone call, was not present or called as a witness. Proba

tion officer Flagg had only talked to her over the phone

on June 9th (E. 48) and Judge McGhee had not spoken

to her at all (E. 76). When Mrs. Gault asked the judge

during this hearing why Mrs. Cook was not present, and

said that “she wanted Mrs. Cook present so she could see

which boy had done the talking, the dirty talking over the

phone” (E. 36), Judge McGhee answered, “she didn’t have

to be present at that hearing” (E. 36).

Conflict also exists about Gerald’s testimony at this sec

ond hearing. Appellants (E. 35) and Mr. Flagg (E. 45)

stated that Gerald did not admit having made any lewd

remarks and only dialed the number. Judge McGhee tes

tified that Gerald again admitted having made some of the

obscene remarks but not the more serious ones (E. 61).

4 There was a conflict in the testimony as to when Gerald was

released and when Mrs. Gault received this note. Probation officer

Flagg, without having made a record about these events, testified

that both occurred on Thursday, June 11th.

7

There was no other evidence about Gerald’s use of lewd

language. Probation officer Flagg testified that Gerald

had never admitted to him that he used any indecent lan

guage over the telephone (E. 57). Nevertheless, in the re

ferral report by the probation department (Exhibit 2,

E. 79) the charge against Gerald on June 8, 1964 was

“lewd phone calls.”

The June 9th petition filed by Mr. Flagg with the Su

perior Court, Gila County (Exhibit 3, E. 80) alleged

that Gerald Gault was “a delinquent minor.” Probation

officer Flagg based this charge on the fact that “the phone

calls were made, and when they were traced, they went to

his home. And the fact that when I asked him to recite

Mrs. Cook’s phone number, he recited it like it was his own”

(E, 50). Asked by appellants’ attorney under which part

of Section 8-201 Gerald had been charged with, Officer Flagg

answered “we set no specific charge in it, other than de

linquency” (E. 52).

There was no conflict in the testimony with regard to the

following facts at both the June 9th and June 15th hear

ings : that the parents were not given a copy of the petition

or written notice of the hearing date except Mr. Flagg’s

note concerning the hearing on June 15th; that the parents

were not informed of the right to subpoena witnesses, to

cross-examine witnesses, of the right to confrontation, or

of the right to counsel (E. 35, 46-47, 59, 71) ;5 that at no

time during the juvenile proceeding was an investigation

5 Though appellants testified that they knew of their right to

call witnesses and to retain an attorney (R. 19, 40), both Mr.

Flagg and the Juvenile Judge acknowledged that they never ad

vised the Gaults of their right to counsel, their right to subpoena

witnesses or their right to cross-examine (R. 46, 59, 71).

conducted to examine Gerald’s home conditions or his be

havior (E. 20, 34, 53). The only investigation claimed to

have been made was apparently conducted in February,

1964, when Gerald had been put on probation on a previous

delinquency charge (E. 53). No record exists of this pre

vious charge or hearing other than a referral report made

by the Probation Department (E. 13).

It is difficult, based on the Juvenile Judge’s testimony,

to know with certainty what the basis was for the finding

of delinquency. The Juvenile Court Judge thought that

the phone calls “amount[ed] to disturbing the peace” 6 7

(E. 61) but he also considered that Gerald was “habitu

ally involved in immoral matters” (I b i d He testified

that there was “Probably another ground, too” (E. 73).

As stated by Judge McGhee, the finding of juvenile de

linquency was based on “the boy’s statements” (E. 76) and

upon the admission of Gerald Gault (E. 65) as to the use of

lewd language and on facts not contained in the juvenile

file, i.e., a referral report in the probation file dated July 2,

1962, that Gerald had stolen a baseball glove. On this report

Judge McGhee had based his finding that the boy was delin

quent because “habitually involved in immoral matters”

even though the report was never followed up, no accusation

was made, and no hearing held “because of lack of material

foundation” (E. 61, 62). The report, and the fact that the

judge relied on it, was not brought to appellants’ knowledge

until August 17, 1964 at the habeas corpus hearing (E.

71-72).

6 Thereby bringing the boy within §8-201(6) (a ) .

7 Thereby bringing the boy within §8-201(6) (d).

9

No warning about the possible consequences of the

charges were given to appellants by the probation officer

(R. 17, 35, 54). Judge McGhee stated that he gave the

usual warning in February and “reminded” the parents of

the February admonition on June 9th (R. 66).

Summary of Argument

I.

Juvenile courts developed out of a desire to treat way

ward youths as a prudent parent treats his child—with

concern for the individuality of each person, the causes

of his acts, and the means to rehabilitate him to be a useful

citizen. This concept of the “parens patriae” led, however,

to a court system in which traditional legal safeguards were

dispensed with in determining whether a child was delin

quent. The barter of due process for individualized treat

ment has cost juveniles dearly, leading this Court recently

to state that “there is evidence . . . that the child receives

the worst of both worlds: that he gets neither the protec

tions accorded to adults nor the solicitous care and regen

erative treatment postulated for children.” Kent v. United

States, 383 TT.S. 541, 555-56 (1966).

II.

The Arizona Juvenile Code, and the proceedings taken

under it in this case, lacked the fundamental procedural

protections that comprise due process of law. This depri

vation of rights cannot be justified. First, the “parens

patriae” notion is no substitute for the fairness that the

juvenile is entitled to when his vital interests are at stake.

Further, there is no substance to any contention to the

10

effect that a juvenile proceeding is “civil” and not “crim

inal” and dispenses “treatment” rather than “punishment”.

Apart from the fact that the rehabilitative ideal is equally

present in the conventional criminal law, the accused juve

nile delinquent stands to lose as much of his liberty, and

sometimes more, than the adult charged with a comparable

offense and prosecuted in the criminal courts. The inter

relationship between Arizona juvenile court actions and

criminal prosecutions further points up the weakness of the

suggestion that juvenile proceedings need not provide due

process of law. Impressed by these considerations, state

and federal courts, draftsmen of modern juvenile court acts,

and scholarly commentators all evince a growing recogni

tion that there are compelling reasons of fairness to pro

vide young people with basic procedural protections in

juvenile court.

A.

The first essential of due process, where an individual’s

liberty is in jeopardy, is that he be clearly informed of the

nature of the charge against him so that he can decide on a

course of action and prepare his defense. Here Gerald

Gault was not properly advised of his acts complained of,

the statute or applicable rule of law such acts were alleged

to violate, or the possible consequences of a finding against

him. In these circumstances, the juvenile court’s decision

to deprive him of six years of liberty violated his consti

tutional rights.

B.

The denial of the right to counsel in this case also vitiated

the proceedings. The decision below on this point flies in

the face of principles painstakingly elaborated by this Court

11

over many years. A juvenile proceeding involving a deter

mination of delinquency carries with it sufficient social

stigma and danger of deprivation of liberty so that there

is no less need for the assistance of counsel there than in

criminal cases, where it has been recognized as a funda

mental constitutional right. Poiuell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45

(1932); Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963). Legal

counsel is particularly vital in juvenile proceedings because

of the immaturity of the accused delinquent, the uncertainty

of the rights possessed b)̂ the accused, the fact that many

juvenile judges are laymen or part-time, and the wide dis

cretion of juvenile courts in dealing with young persons

adjudged delinquent.

C.

This court has unanimously held that the Sixth Amend

ment guarantee of confrontation and cross-examination is

an integral part of due process because without them there

can be no fair or reliable determination of truth. Begard-

less of whether juvenile proceedings are denominated crim

inal or civil, these rights must be available. Surely a ju

venile proceeding in which the loss of liberty is at stake

involves interests as great as those involved in adjudicatory

administrative proceedings, where confrontation and cross-

examination have been held to be constitutionally mandated.

Here Gerald Gault was adjudged a delinquent without any

consideration of the testimony of the woman alleged to have

received the obscene telephone call. The confusing testi

mony of others concerning what actually happened and

whether Gerald Gault was involved accentuates the error

of the notion that an individual can be deprived of liberty

without the trier of fact hearing the testimony of the

alleged victim.

12

D.

Gerald Gault was found to have committed a crime under

the law of Arizona and his commitment by the court rested

in part on that finding. There is no dispute that decisive

admissions of elements of this offense were elicited from

him by the juvenile court, which gave him no advice that

he did not have to testify. Under familiar principles, the

privilege against self-incrimination can be claimed “in any

proceeding, be it criminal or civil, administrative or judi

cial, investigative or adjudicatory.” Murpliy v. Waterfront

Commission, 378 U.S. 52, 94 (1964). The relevant inquiry

is whether the witness may in any way incriminate himself

by testifying or making a statement. Under the law of

Arizona, Gerald Gault ran the risk when he testified of

furnishing evidence which could be used against him in a

criminal prosecution. In these circumstances, the State

was required either to afford him the privilege against

self-incrimination or grant him immunity commensurate

with the risk. It did neither, in plain violation of the

Constitution.

E.

The State’s failure to provide a right of appellate review

of the juvenile court decision or a right to a transcript of

the proceedings in the juvenile court constitutes a departure

from the requirements of due process of law. Although

it has been said that a state is not required to provide

appellate review of criminal actions, there can be no “li

cense for arbitrary procedure.” Kent v. United States,

383 U.S. 541, 553 (1966). The Arizona statutory scheme

grants to the juvenile judge practically unlimited discretion

in the conduct of a hearing at which individual liberty is

13

at stake. Such a proceeding cannot be squared with con

stitutional requirements of fundamental fairness unless

there is opportunity for direct review, or at least collateral

review on the basis of an official transcript.

A R G U M E N T

I.

The historical background of procedural deficiencies

in Juvenile Courts.

This case presents the important constitutional question

of the extent to which certain fundamental requirements of

procedural fairness guaranteed by the Due Process Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment are applicable to juvenile

court proceedings. The history of juvenile courts in this

country is valuable in appreciating the background and

dimensions of this question. It reveals both the high pur

poses of the movement that led to juvenile courts and how

these purposes came to be perverted in the form of pro

ceedings—as exemplified by this case from Arizona—that

lack the most elemental protections of due process.

Before the enactment of juvenile court acts, criminal

prosecutions against juveniles and adults were handled

identically and included the same procedural safeguards.8

At the turn of the century, insights acquired through the

development of the behavioral sciences—penology, psy

chiatry, psychology and social work—led to popular and

8 See Welch, Delinquency Proceedings—Fundamental Fairness

for the Accused in a Quasi-Criminal Forum, 50 Minn. L. Rev. 653,

654-55 (1966) ; In Be Poff, 135 F. Supp. 224, 225 (D. D. C. 1955).

See generally Antieau, Constitutional Rights in Juvenile Courts,

46 Cornell L. Q. 387 (1961).

14

professional dissatisfaction with prosecutions against chil

dren. This led to the establishment of the first juvenile

court in 1899 in Cook County, Illinois (111. Laws, 1899, at

131). Since then, all states have provided by statute that

children who are accused of acts which would violate the

criminal law or who are alleged to be beyond the control

of their parents—“incorrigible”, “wayward”, or “ungovern

able”—are subject to proceedings in a juvenile or family

court.9

Underlying all juvenile law is the concept of the state

as the guardian of the child or “parens patriae”. The princi

ple is that the child who has acted wrongly should be treated

by a court as a prudent parent treats his erring child, not

as a criminal. In the words of an early study:

“ [T]he state must step in and exercise guardianship over

a child found under such adverse social or individual

conditions as develop crime. . . . It proposes a plan

9 State code provisions are compiled and compared in : Institute

of Judicial Administration, Juvenile Courts-Jurisdiction (1961);

Sussman, Law of Juvenile Delinquency (Rev. ed. 1959) ; Tomp

kins, In the Interest of a Child (1959) (prepared for the California

Special Study Commission on Juvenile Justice) ; Illinois Legisla

tive Council, Juvenile Court Proceedings in Delinquency Cases

(1958) (12 selected states).

Model and Uniform legislation and standards appear in: Na

tional Probation and Parole Association (NPPA) (now the National

Council on Crime and Delinquency, NCCD), Standard Ju

venile Court Act (Rev. 1959), 5 NPPAJ 323 (1959); NCCD Stand

ard Family Court Act (1959) ; Children’s Bureau, U. S. Dept, of

Health, Education and Welfare, Standards for Juvenile and

Family Courts (1966); NPPA, Guides for Juvenile Court Judges

(1957); see also The Interstate Compact on Juveniles: Develop

ment and Operation, 8 J. of Pub. Law 524 (1959). A recent study

of the operation of these courts is contained in Note, Juvenile

Delinquents: The Police, State Courts, and Individualized Justice,

79 Harv. L. Rev. 775 (1966).

15

whereby he may be treated, not as a criminal, or legally

charged with a crime, but as a ward of the state, to

receive practically the care, custody and discipline that

are accorded the neglected and dependent child, and

which . . . shall approximate as nearly as may be that

which should be given by its parents.” 10

In brief, the early juvenile courts emphasized the indi

viduality of the child, the causes of his act, and the means

to help him to become a useful citizen. “The problem for

determination by the judge is not, Has this boy or girl

committed a specific wrong, but What is he, how has he be

come what he is, and what had best be done in his interest

and in the interest of the state to save him from a down

ward career.” Mack, The Juvenile Court, 23 Harv. L. Rev.

104, 119 (1909), quoted in People v. Lewis, 260 N. Y. 171,

177, 183 N. E. 353, 355 (1932).

It was a short step from the concept of individualized

justice in the treatment or rehabilitative phase of a pro

ceeding to a greater informality in the trial itself. It was

feared that the fact-finding procedures of our accusatory,

adversary system of criminal trials were inimical to the

establishment of the relationship between court and child

which was thought necessary to his proper treatment and

rehabilitation.

The consequence of this “swapping” of due process for

parens patriae was that many traditional legal safeguards

of criminal proceedings were dispensed with, to the in

10 Report of the Committee of the Chicago Bar, 1899, quoted in

Glueck, Some “Unfinished Business” in the Management of Ju

venile Delinquency, 15 Syracuse L. Rev. 628, n. 2 (1964).

16

evitable detriment of individual rights.11 Some courts even

went so far as to insist flatly that constitutional safeguards

of criminal procedure were not applicable to juvenile pro

ceedings. In re Holmes, 379 Pa. 599, 603, 109 A. 2d 523,

525 (1954), cert, denied, 348 U. S. 973 (1955). In other

courts the result was a host of questionable decisions.

Vague allegations of anti-social behavior were sufficient to

bring a child before some juvenile courts,12 and the infor

mality of the juvenile procedure was often used to accept

uncorroborated admissions, hearsay testimony and the un

tested reports of social investigations.13 The right to coun

sel and the right to notice of charges were sometimes dis

pensed with.14 The protections against self-incrimination

and double jeopardy also were rejected in some courts on

11 Glueck, Some “Unfinished Business” in the Management of

Juvenile Delinquency, 15 Syracuse L. Rev. 628, 629 (1964). See

also Antieau, Constitutional Rights in Juvenile Courts, 46 Cornell

L. Q. 387 (1961); Note, Juvenile Courts: Applicability of Consti

tutional Safeguards and Rules of Evidence to Proceedings, 41

Cornell L. Q. 147 (1955); Paulsen, Fairness to the Juvenile

Offender, 41 Minn. 547 (1957).

12 In re Bentley (Harry v. State), 246 Wise. 69, 16 N. W. 2d 390

(1944); State ex rel. Baddue v. Superior Court, 106 Wash 619

180 P. 875 (1919).

13 Uncorroborated Admissions: In the Matter of Gonzalez, 328

S. W. 2d 475 (Tex. Ct. App. 1959); Matter of McDonald, 153 A. 2d

651 (D. C. Munic. Ct. App. 1959). Hearsay: In re Holmes, 379

Pa. 599, 109 A. 2d 523 (1954), cert, denied, 348 U. S. 973 (1955) ;

State ex rel. Christensen v. Christensen, 119 Utah 361, 227 P. 2d

760 (1951); Sylvester v. Commonwealth, 253 Mass. 244 148 N E

449 (1925). ' ‘

14Notice of charges: In re Duncan, 107 N. E. 2d 256 (1951) •

In re Bentley, 246 Wis. 69, 16 N. W. 2d 390 (1944). Right to

counsel: People v. Dotson, 46 Cal. 2d 891, 299 P. 2d 875 (1956);

Akers v. State, 114 Ind. App. 195, 51 N. E. 2d 91 (1943) • In

Interest of T. W. P., 184 So. 2d 507 (Fla. Ct. of App. 1966).’

17

the ground that the juvenile proceeding is a civil rehabilita

tive procedure and not a criminal proceeding.15

This is not to say that the juvenile court movement

did not lead to advances in the treatment of juveniles.

It is rather to emphasize that the net effect of developments

over the past half century was that juvenile court proceed

ings, which were instituted to protect the young, led in

many jurisdictions to findings of delinquency in proceed

ings that conspicuously failed to protect the child. See

Horwitz, The Problem of the Quid pro Quo, 12 Buffalo

L. Rev. 528 (1963). As stated by the dissenting Judge in

In re Holmes, supra, 379 Pa. at 615, 109 A. 2d at 530.

The concept that the State acts as parens patriae is

being somewhat overdone. Even if the state assumes

the parental role, this assumption does not prove that,

by divine omniscience, it cannot be other than just. It is

not impossible for a father, or even a mother, to be

unreasonable with offspring. What a child charged

with crime is entitled to, is justice, not a parens patriae

which in time may become a little calloused, partially

cynical and somewhat over-condescending. (Emphasis

in original.)

The disturbing state of affairs regarding the quality of

justice meted out to young people recently received the

attention of this Court in Kent v. United States, 383 U. S.

541 (1966). There, with specific reference to the gap be

tween ideal and reality, Mr. Justice Fortas said:

15 Self-incrimination: In re Holmes, supra; People v. Lewis,

260 N. Y. 171, 183 N. E. 353 (1932) ; In re SantiUanes, 47 N. M.

140,138 P. 2d 503 (1943). Double Jeopardy: People v. Silverstein,

121 Cal. App. 2d 140, 262 P. 2d 656 (1953). In re Santillanes,

supra. See generally Sussman, Juvenile Delinquency, pp. 11-16

(1955).

18

“While there can be no doubt of the original laudable

purpose of juvenile courts, studies and critiques in

recent years raise serious questions as to whether

actual performance measures well enough against

theoretical purpose to make tolerable the immunity of

the process from the reach of constitutional guaranties

applicable to adults. . . . There is evidence, in fact,

that there may be grounds for concern that the child

receives the worst of both worlds: that he gets neither

the protections accorded to adults nor the solicitous

care and regenerative treatment postulated for chil

dren.” 383 U. S. at 555-56.

The remainder of this brief will try to demonstrate that

the petitioner in this case, like countless other juveniles in

Arizona and other jurisdictions, has in fact been receiving

the “worst of both worlds” in plain derogation of the

requirements of the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

II.

The Arizona juvenile proceedings failed to provide

Gerald Gault with fundamental procedural protections

that are required by the flue process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment.

As the history summarized under Point I indicates,

young persons appearing before juvenile courts throughout

the country are frequently denied many of the protections

accorded adults who are accused of crime. In the instant

case Gerald Gault was “tried” and committed to the State

Industrial School in a proceeding conducted under the

Arizona Code that sharply illustrates the “procedural arbi

19

trariness” (Kent v. United States, supra 383 U. 8. at 555)

that often characterizes juvenile courts.

The Arizona Code does not contain standards for the

arrest of a child charged with a violation of law (§8-221)

and, as interpreted by the Arizona Supreme Court, does

not incorporate the general law of arrest (R. 96); the

statute provides merely for an informal hearing in the

judge’s chambers (§8-229). No written transcript of the

heai’ing is required, regardless whether the proceeding

leads to a commitment or not; only a record of the name,

age, place of birth of the child and names of his parents

must be made. The statute does not impose an}7 limitations

on the judge with respect to the nature of evidence to be

used; it does not contain a requirement for sworn testi

mony or cross examination of witnesses; it does not confer

the privilege against self-incrimination upon the juvenile;

it does not require that a transcript of the proceedings be

made and makes no provision for appellate review. It also

gives the judge authority to make any order for the com

mitment, custody or care of the child “as the child’s welfare

and the interest of the state require” (§8-231). No stand

ards limit this wide discretion of the judge. He may

commit a child until his majority, as in this case. He is not

required to establish a relationship between the specific act

of juvenile delinquency and the period of commitment; he

does not have to show that the juvenile’s parents are unfit

to handle the child when taking a child from the custody

of his parents (407 P. 2d at 769; R. 96).

The boundless discretion conferred upon the juvenile

court by the Arizona Code was exercised in this case to de

prive appellants of due process. This becomes clear by

tracing the events that occurred prior to and during the

hearing.

20

Gerald Gault was arrested by the sheriff, detained by

probation officers without an order of court, and interro

gated at length. His parents were neither notified of the

arrest nor informed of its grounds. The only written

notice they ever received was contained in a note Mrs. Gault

received from officer Flagg on Friday, June 12th, about

the continuance of Gerald’s hearing “on his delinquency.”

The time allowed appellants to prepare their case was

extremely short. The hearing itself consisted mainly of

hearsay statements. No witnesses were sworn. The com

plainant was not called as a witness, even though appel

lants had requested her presence, because the judge de

cided that she was not necessary (E. 36). As conceded by

Judge McGhee, his finding of delinquency was derived not

only from the “boy’s statements” as to the use of lewd

language, but on his “habitual involvement in immoral

matters,” based on a referral report in the probation file

which had never led to an accusation or hearing (R. 61).

Appellants had no notice of this report and no opportunity

to deny or defend against the charges.

In both juvenile hearings appellants appeared without

counsel. They were neither informed of a right to counsel

nor told that they would be furnished counsel in case of

need (R. 35, 46-47, 59). The order of commitment taking

the child from his parents for up to six years was made

without investigation of the conditions in his home and

without any warning that such a draconian remedy might

follow. Finally, there was no transcript kept of the pro

ceeding and no provision for appellate review of possible

procedural errors or the evidentiary basis for the decision.

21

It is plain that in this case Arizona largely if not wholly

dispensed with the basic procedural protections that are

understood to comprise “due process of law.” In attempt

ing to justify this handling of Gerald Gault, the Supreme

Court of Arizona adhered closely to the usual formulation

(407 P. 2d at 765; R. 88-89):

“ . . . [JJuvenile courts do not exist to punish children for

their transgressions against society. The juvenile court

stands in the position of a protecting parent rather

than a prosecutor. It is an effort to substitute protec

tion and guidance for punishment, to withdraw the

child from criminal jurisdiction and use social sciences

regarding the study of human behaviour which permit

flexibilities within the procedures. The aim of the court

is to provide individualized justice for children. What

ever the formulation, the purpose is to provide authori

tative treatment for those who are no longer respond

ing to the normal restraints the child should receive at

the hands of his parents. The delinquent is the child

of, rather than the enemy of society and their interests

coincide. . .

This statement reduces to two overlapping theories. The

first is the “parens patriae” notion, already alluded to under

Point I. The second is that the child is not involved in a

criminal proceeding and is not receiving “punishment” but

“treatment.” Neither of these arguments, nor any other

possible theory, can justify the refusal to accord Gerald

Gault and other juveniles the protection of the Bill of

Rights.

It has already been pointed out that although the parens

patriae has roots in a genuine attempt to rehabilitate juve-

2 2

idle delinquents, what “a child charged with crime is en

titled to, is justice, not a parens patriae.” In re Holmes,

supra, 379 Pa. at 615, 109 A. 2d at 530 (dissenting opinion).

The failure to provide appellants with due process—i.e.,

“justice”—is the basis for the claim in this case, and it is

submitted that the theoretical comforts of a surrogate

parent are barren in the face of the hard realities of a

proceeding in which the vital interests of a child are en

gaged.

These interests of the child are equally compelling in re

jecting the mischievous notion that what is being meted out

in juvenile proceedings is “treatment” and not “punish

ment.” In the first place, modern criminology accords a

high place to “rehabilitation” of criminals, thereby invali

dating any purported distinction between juvenile and adult

proceedings on this score. This Court has said

“Retribution is no longer the dominant objective of the

criminal law. Reformation and rehabilitation of of

fenders have become important goals of criminal juris

prudence.” Williams v. New York, 337 U. S. 241, 248

(1949).

See also Benson v. United States, 332 F. 2d 288, 292 (5th

Cir. 1964); Radzinowicz and Turner, A Study of Punish

ment I : Introductory Essay, 21 Canadian Bar Rev. 91-97

(1943); and Allen, Criminal Justice, Legal Values and the

Rehabilitative Ideal, 50 J. Crim. L. C. and P. S. 226 (1959).

Even apart from the failure of the “rehabilitation” theory

to justify a failure to provide juveniles with procedural

protection, the plain fact is that in this case and in countless

others the juvenile is forcibly removed from his home and

family through the force of the state. He is confined, per

haps until his majority, “to a building with whitewashed

walls, regimented routine and institutional hours”. In re

Holmes, supra, 379 Pa. at 616, 109 A. 2d at 530 (dissenting

opinion). That he is sent to a “home” or a “training school”

rather than a prison does not in the least detract from the

coerced loss of freedom. The child stands to lose every bit

as much as an adult in a comparable situation. In fact, the

child’s situation may be drastically worse, as this very case

demonstrates. While an adult accused of the “crime” of

using obscene language over the telephone could be con

victed in Arizona of a misdemeanor and sentenced to a

maximum of two months imprisonment (Arizona Stats.

§13-377), Gerald Gault was deprived of his liberty for

up to six years (R. 82) for the very same act, even though

he was not convicted of a “crime” and technically was not

“punished.”

The lack of substance to any purported distinction be

tween the usual criminal prosecution and a juvenile pro

ceeding is emphasized by the interrelationship between ju

venile court actions and criminal prosecutions under the

law of Arizona. As developed more fully below (pp. 51-54),

the Arizona constitutional and statutory scheme for han

dling juveniles does not divest the criminal courts of juris

diction. The Arizona system merely charges juvenile judges

to decide in the first instance whether to “suspend criminal

prosecution” or to allow such prosecutions to proceed. Not

until there is an actual adjudication in the juvenile court

is the young person suspected of action constituting a crime

free from the possibility of prosecution.

In these circumstances, it is idle to suggest that the

lax Arizona juvenile procedures relating to notice of

charges, right to counsel, confrontation of witnesses, and

24

the rest, can be justified on the ground that juvenile court

actions are not “criminal.” As stated by a California court,

the fact that delinquency involves the possible deprivation

of liberty makes the differentiation between adult crim

inal proceedings and juvenile civil proceedings “for all

practical purposes . . . a legal fiction presenting a chal

lenge to credulity and doing violence to reason.” In re

Contreras, 109 Cal. App. 2d 787, 789, 241 P. 2d 631, 633

(1952).

As the Contreras case suggests, there is growing recog

nition that “there shall be no greater diminution of the

rights of a child, as safeguarded by the Constitution, than

should be suffered by an adult charged with an offense

equivalent to the alleged act of delinquency of the child.”

Application of Johnson, 178 F. Supp. 155, 160 (D. N. J.

1957). An increasing number of cases have held that “a

juvenile is entitled to fundamental due process of law”.

State v. Naylor, 207 A. 2d 1, 10 (Del. 1965). See In re

Alexander, 152 Cal. App. 2d 458, 461, 313 P. 2d 182, 184

(1957); Brewer v. Commonwealth, 283 S. W. 2d 702, 703

(Ky. 1955); United States v. Morales, 233 F. Supp. 160, 167

(D. C., Mont., 1964); In re Contreras, supra. The underly

ing basis for these holdings has been set forth in Trimble

v. Stone, 187 F. Supp. 483, 485-86 (D. D. C. 1960):

“The fact that the proceedings are to be classified as

civil instead of criminal, does not, however, necessarily

lead to the conclusion that constitutional safeguards

do not apply. It is often dangerous to carry any propo

sition to its logical extreme. These proceedings have

many ramifications which cannot be disposed of by de

nominating the proceedings as civil. Basic human

25

rights do not depend on nomenclature. What if the

jurisdiction of the Juvenile Court were to be extended

by an Act of Congress to the age of twenty-one or even

twenty-five, or what if it were to be reduced to sixteen ?

Could it be properly said that the constitutional safe

guards would be increased or diminished accordingly?

“Manifestly the Bill of Rights applies to every indi

vidual within the territorial jurisdiction of the United

States, irrespective of age. The Constitution contains

no age limits.”

In short, there is growing recognition of the importance

of providing juveniles with the protection of the Consti

tution.16 As stated in In re Poff, 135 F. Supp. 224, 225,

227 (D. D. C. 1955), the original purpose of the juvenile

court movement was “to afford the juvenile protections in

addition to those he already possessed . . . to enlarge, not

to dimmish those protections.” (Emphasis in original.)

This Court in effect recognized the constitutional dimen

sions of the problem in Kent v. United States, 383 U. S.

16 Dembitz, Ferment and Experiment in New York: Juvenile

Cases in The New Family Court, 48 Cornell L. Q. 499 (1963);

Keteham, Legal Renaissance in the Juvenile Court, 60 Nw. U. L.

Rev. 585 (1965); Antieau, Constitutional Rights in Juvenile Courts,

46 Cornell L. Q., 387 (1961) ; Paulsen, Fairness to the Juvenile

Offender, 41 Minn. L. Rev. 547 (1957) ; Rubin, Protecting the Child

in the Juvenile Court, 43 J. Crim. L. C. and P. S. 425 (1952) •

Welch, Delinquency Proceedings—Fundamental Fairness for the

Accused in a Quasi-Criminal Forum, 50 Minn. L. Rev. 653 (1966) ;

Beemsterboer, The Juvenile Court—Benevolence in the Star Cham

ber, 50 J. Crim. L. C. and P. S. 464 (1960) ; Skoler, Juvenile Courts

and Young Lawyers, 10 The Student Law. J. 5 (Dee. 1964) ; Quick,

Constitutional Rights in the Juvenile Court, 12 How. L. J. 76

(1966).

26

541 (1966). Although the Court did not reach petitioner’s

specific constitutional claims, it stated with respect to the

determination of waiver of juvenile court jurisdiction:

“ [T]here is no place in our system of law for reaching

a result of such tremendous consequences without cere

mony—without hearing, without effective assistance of

counsel, without a statement of reasons.” 383 U. S. at

554.

Due process for juveniles is particularly necessary in a

time of an increasing juvenile population. With full ap

preciation of the high stakes in these proceedings both from

the standpoint of the child himself and from that of society

in preventing the permanent loss of a law abiding citizen,

Judge Midonick of the New York Family Court said in

In re Ronny, 40 Misc. 2d 194, 210; 242 N. Y. S. 2d 844,

860-61 (Family Ct. 1963):

“I can think of few worse examples to set for our

children than to visit upon children what would be,

if they were older, unreasonable and unconstitutional

invasions of their all-too-limited privacy and rights,

merely because they are young. . . . We would do

well to stand solidly in behalf of children before us

to avoid contamination of the fact sources and to

see to it that we brook no shabby practices in fact

finding which do not comport with fair play. We

must not only be fa ir; we must convince the child . . .

that the judge, a parent image, is careful to ensure

those civilized standards of conduct toward the child

which we expect of the child toward organized society.17

17 This view has been supported by other judges with long ex

perience in juvenile courts. “The example of a juvenile court that

27

Modern juvenile and family court acts have also been

responsive to the fundamental unfairness of subjecting

young people to proceedings in which their liberty is at

stake without the procedural protections accorded adults

in criminal trials. The Standard Juvenile Court Act, as

well as the California Juvenile Court Law and the New

York Family Court Act, incorporate basic due process

requirements, such as the rights to counsel, a record of

the proceeding and appeal.18 The new 1966 Standards

for Juvenile and Family Courts published by the Children’s

Bureau of the Department of Health, Education, and Wel

fare contain express minimum requirements “as an es

sential part of individualized justice” (p. 7) in juvenile

courts with regard to the right to notice of charges, con

frontation and cross-examination of witnesses, written

findings of fact, to a record of the hearing, right to counsel

and appeal. The HEW Standards state (p. 8):

“Certain procedural safeguards must be established for

the protection of the rights of parents and children.

Although parties in these proceedings may seldom make

use of such safeguards, their availability is none the

less important. They are required by due process

operates under the restraint of due process of law . . . may renew

in our children the respect for law courts and the judicial process

which is said to be on the decline.” Ketcham, Legal Renaissance in

the Juvenile Court, 60 Nw. U. L. Rev. 585, 595 (1965).

13 NPPA, Standard Juvenile Court Act (Rev. 1959); Cal. Wel

fare and Institutions Code §§500-914, 1961; N. Y. Family Court

Act, 1962. §711 of the N. Y. Family Court Act provides:

“The purpose of this article is to provide a due process of law

(a) for considering a claim that a person is a juvenile de

linquent or a person in need of supervision and (b) for devis

ing an appropriate order of disposition for any person ad

judged a juvenile delinquent or in need of supervision.”

2 8

of law and are important not only for the protection

of rights bnt also to help insure that the decisions

affecting the social planning for children are based

on sound legal procedure and will not be disturbed

at a later date on the basis that rights were denied.”

There are, in sum, compelling reasons of fairness and

authority to provide young people with fundamental pro

cedural protections in juvenile court. Accordingly, this

Court should rule that appellants were denied due process

of law by the failure of Arizona to provide the basic ele

ments of procedural fairness in this juvenile proceeding.19

19 Absence of procedural safeguards affects not only the relia

bility of juvenile proceedings but permits arbitrary disposition

of young people who will not “cooperate” or who are involved in

unpopular social movements. Juveniles, for example, have com

prised a large proportion of those who in the past decade have

peacefully demonstrated for their civil rights and have been un

lawfully arrested for asserting constitutionally protected rights.

The treatment accorded these minor Negroes in juvenile courts

demonstrates the capacity of juvenile courts to punish for reasons

totally unrelated to their individual welfare. In one of the few

studies of the subject, the United States Civil Rights Commission

concluded that “ . . . local authorities used the broad definition

afforded them by the absence of safeguards [in juvenile pro

ceedings] to impose excessively harsh treatment on juveniles.”

U. S. Comm’n on Civil Rights Report, Law Enforcement, 1965,

pp. 80-83.

The place the Commission studied was Americus, Georgia where:

“Approximately 125 juveniles were arrested during the

Americus demonstrations, and their eases disposed of in a

unique manner. Some of them were released from jail upon

payment of a jail fee of $23.50, plus $2 per day for food.

These fees were paid by parents who agreed to send their

children to relatives living in the country. No court hearing

was held in these cases; of those juveniles who appeared in

court (approximately 75% of those arrested) about 50 were

sentenced to the State Juvenile Detention Home and placed

on probation on the condition that they would not associate

with certain leaders of civil rights organizations in Americus.

“Many juveniles arrested in Americus were detained for

long periods of time without bail or hearing. The juvenile

29

The specific guarantees of the Bill of Bights denied appel

lants will now be considered with particularity.

A. Notice of Charges and Hearing.

The first essential of due process, where an individual’s

liberty is in jeojoardy, is that he be clearly informed of

the nature of the charge against him so that he can prepare

his defense. Further, he must be given adequate time and

opportunity after notice of charges to decide on his course

of action and to prepare that defense. Cole v. Arkansas,

333 IT. S. 196 (1948). See also Ilove-y v. Elliott, 167 U. S.

409 (1897); Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45 (1932); In re

Oliver, 333 IT. S. 257 (1948); In re Murchison, 349 IT. S.

133 (1955); Williams v. New York, 337 U. S. 241 (1949).

court judge explained the reason for this in Federal court:

“If one is bad enough to keep locked up, they’re not entitled

to bail; and if they’re not bad enough, there’s no use to make

them make bond.” Id. at pp. 81-82.

See also Meltsner, “Southern Appellate Courts: A Dead End” in

Friedman (ed.), Southern Justice 152 (1965).

Although the reported decisions are few, petitions to adjudge

minors delinquent because of peaceful and lawful civil rights ac

tivity has been a common response in southern states. Ten minor

Negroes were arrested in Montgomery, Alabama on April 15, 1965,

as they were peacefully picketing a store in downtown Montgomery

and objecting to its discriminatory hiring practices. They were

prosecuted under an ordinance which stated that “not more than

six persons shall demonstrate at any one time before the same

place of business or public facility.” Although their conduct was

orderly in every respect attempts were made to declare the chil

dren delinquents. A federal district judge found that they were

merely exercising a constitutionally protected right of free speech

and assembly and dismissed the charges. In re Wright, 251

F. Supp. 880 (M. D. Ala. 1965). See also Florence v. Meyers, 9

Eace Eel. L. E. 44 (M. D. Fla. 1964) (order to arrest juveniles

on sight unlawful; injunction granted) ; Griffin v. Hay, 10 Eace

Eel. L. Ee. I l l (E. D. Ya. 1965) (order that juveniles refrain

from protected activity unlawful; injunction granted). See gen

erally Starrs, A Sense of Irony in Juvenile Courts, 1 Harv. Civil

Bights—Civil Liberties L. Eev. 129 (1966).

30

In Cole, this Court spelled out the vital nature of notice:

“No principle of procedural due process is more clearly

established than that notice of the specific charge, and

a chance to be heard in a trial of the issues raised by

that charge . . . are among the constitutional rights

of every accused in a criminal proceeding in all courts,

state or federal.” 333 U. S. at 201.

Notice, to be fully effective, must contain at least three

ingredients: (1) it must state what acts are complained

of; (2) it must state what statute or applicable rule of law

such acts violate; and (3) it must give some indication of

the consequences of a finding against the accused. All of

these were absent in the proceedings below.

No official notice of the nature of the imminent hearings

was given to appellants. In the most casual fashion, and

only after she requested the information, was Mrs. Gault

orally informed by officer Flagg on the night of June 8th

that Gerald had been detained that afternoon and that a

hearing would be held the very next day (R. 29). The only

written notice of any kind appellants ever received was con

tained in a handwritten note on blank paper addressed to

Mrs. Gault and received from probation officer Flagg on

Friday, June 12th. It merely stated that Judge McGhee

had set Monday, June 15th, as the time “for further hear

ings on Gerald’s delinquency” (R. 78).

No effective notice of the underlying basis for the charge

of delinquency was given to appellants. This worked se

verely to appellants’ prejudice. Judge McGhee testified

that he based his adjudication of delinquency in part on a

finding that Gerald had violated Ariz. Rev. Stats. §13-377,

the obscene language provision of the Arizona Criminal

31

Code20 (R. 61-63). Yet this statute was never cited to ap

pellants.

Indeed, the petition filed with the court on June 9th by

probation officer Flagg recited only that he was informed

and believed that “said minor is a delinquent minor and

that it is necessary that some order be made by the Honor

able Court for said minor’s welfare” (R. 80).21 But even

this totally inadequate notice of the basis of the proceedings

was not given to appellants. They never even saw the

petition on which the adjudication of the delinquency of

their son was based until after the decision had been made.22

Thus appellants’ attention was never called to any stat

ute or statutory language which might have given them

20 Section 13-377 provides : “A person who, in the presence or

hearing of any woman or child, or in a public place, uses vulgar,

abusive or obscene language, is guilty of a misdemeanor punishable

by a fine of not less than five nor more than fifty dollars, or by im

prisonment in the county ja.il for not more than two months.”

21 The petition gave no indication that an adjudication of de

linquency was sought under Section 8-201-6 (a) of the Arizona

Statutes, which defines “delinquent child” as a “child who has

violated a law of the state or an ordinance or regulation of a

political subdivision thereof.” Nevertheless, Judge McGhee testi

fied that this provision formed part of the bases for his decision.

The Arizona statute (§8-222) provides that such a petition, con

taining a igeneral allegation of delinquency (without stating the

facts supporting the allegations), is sufficient, but the clear trend

of current legislation is to require specificity in such pleadings

which are jurisdictional prerequisites to juvenile court action. Cf.

N. Y, Family Ct. Act, Sec. 731; Cal. Welfare and Institutions

Code, Secs. 653, 656; Natl. Probation and Parole Assoc., Standard

Juvenile Court Act, Sec. 12.

22 The Arizona court appears to have held that in the future, a

copy of this petition must be given to the infant and his parents

(407 P. 2d at 767; R. 92). The failure even to serve the con-

clusory petition in this ease on appellants points up the procedural

unfairness to which they were subjected.

32

some guidance as to what the charge of delinquency was

based on, or how to prepare a legal defense to it, or even

how to decide intelligently whether to contest it at all.

Nothing brought home to them the advisability of consult

ing with or retaining counsel, or impressed on them the

potential seriousness of the proceedings for their son as

evidenced by the drastic sanction later imposed by the court.

Even the minimal standards required by the Arizona stat

ute with regard to notice of delinquency charges as inter

preted by the Arizona Court, i.e., that it is sufficient if

the court advises the parents no later than the hearing

itself about “the facts involved in the case” (407 P. 2d at

767; R. 92), were not satisfied in this case. As stated by

Judge McG-hee, his finding of juvenile delinquency was

based not only on the boy’s use of lewd language (R. 61),

but also on the boy’s “habitual involvement in immoral

matters,” based on a referral report in the probation file

which had never led to an accusation or hearing (Ibid.).

The parents never had notice of this report, even at the

hearings held in this case, and had no opportunity to deny

those charges or defend against them. As to this basis for

the adjudication of delinquency, there was simply no notice

and no opportunity to be heard at all.

Finally, the time allowed to appellants to prepare their

case was extremely short. For the first hearing from