Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, MD Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, MD Brief for Appellants, 1954. 22fb206b-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e484ad38-513b-4fac-b238-b629e7d0a893/dawson-v-mayor-and-city-council-of-baltimore-md-brief-for-appellants. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

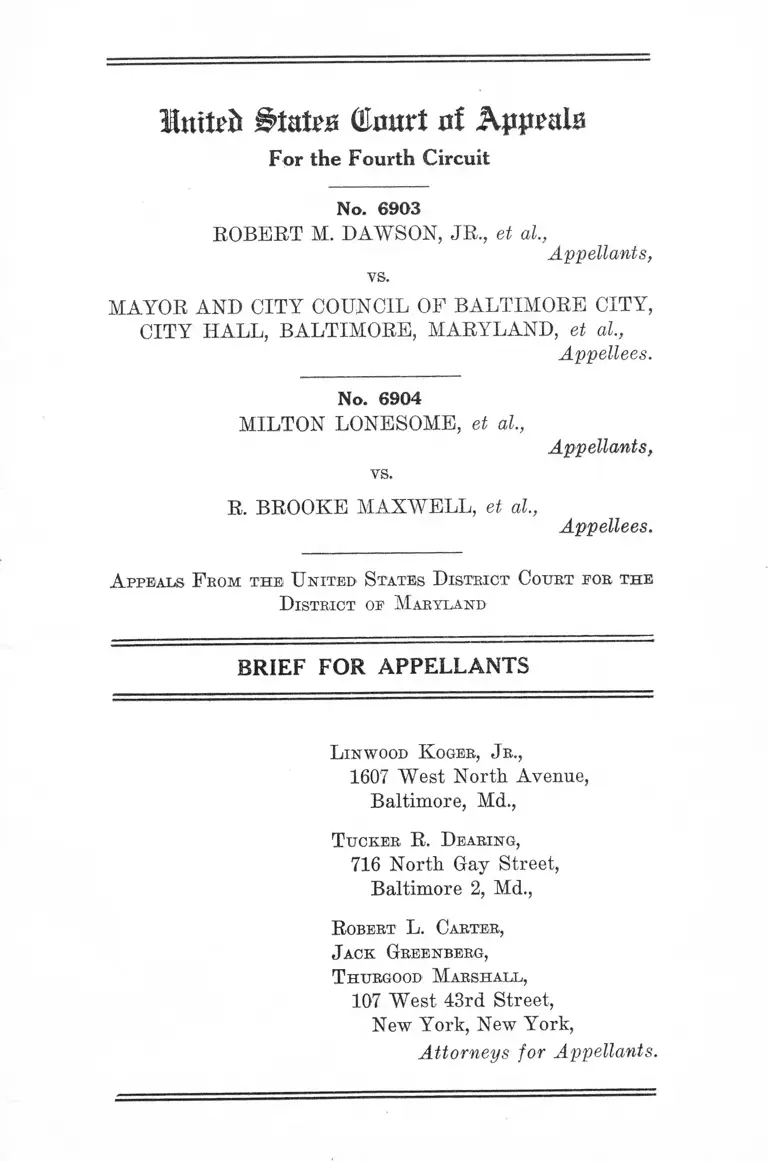

luitrfc (ilimrt at Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

No. 6903

ROBERT M. DAWSON, JR., et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL OF BALTIMORE CITY,

CITY HALL, BALTIMORE, MARYLAND, et al,

Appellees.

No. 6904

MILTON LONESOME, et al.,

vs.

Appellants,

R. BROOKE MAXWELL, et al,

Appellees.

A ppeals F rom the U nited States D istrict Court for the

D istrict of Maryland

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

L inwood K oger, J r.,

1607 West North Avenue,

Baltimore, Md.,

T ucker R. Dearing,

716 North Gay Street,

Baltimore 2, Md.,

R obert L. Carter,

Jack Greenberg,

T hurgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Appellants.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE:

Statement of the C ase ................................................. 1

The Dawson C ase ................................................. 1

The Lonesome Case ............................................. 3

Question Presented ..................................................... 4

Statement of F a cts ....................................................... 4

The Dawson C ase................................................. 4

The Lonesome Case ............................................. 5

Argument ...................................................................... 6

State Imposed Racial Restrictions With Respect

to the Use and Enjoyment of Publicly Owned

and Operated Recreational Facilities Are For

bidden by the Fourteenth Amendment............. 6

Conclusion...................................................................... 16

Table of Cases

Barbier v. Connelly, 113 U. S. 2 7 ................................ 11

Beal v. Holcombe, 193 F. 2d 384 (C. A. 5th 1951),

cert, denied, 347 U. S. 974 .................................... 13,14

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (School Segregation

Cases) ...............................................................2,7,9,12,15

Boyer v. Garrett, 182 F. 2d 582 (1950), cert, denied,

340 U. S. 912 ...........................................................7,13,14

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (School

Segregation Cases) ........................................ 2,7,9,10,15

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 .............................. 8, 9,12

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (1951), cert, denied,

341 U. S. 941 9

11

PAGE!

Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry., 218 U. S. 71 . . . . 9

Gumming v. County Board of Education, 175 U. S.

528 ............................................................................. 10

Durkee v. Murphy, 181 Md. 259, 29 A. 2d 253 (1942) 6

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 7 8 .................................. 8,10

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 8 1 6 ............. 9

McKissick v. Carmichael, 181 F. 2d 949 (C. A. 4th

1951) ....................................................................... 13

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S.

637 ..............................................................................9,13,14

Maryland v. Baltimore Radio Show, Inc., 338 U. S.

912............................................................................... 14

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 . . . . 9,10

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 337 .............................. 9,12

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 ..................................... 11

Ovama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 ............................ 11

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ............................ 8,10

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 U. S. 389 11

Rice v. Arnold, 45 So. 2d 195 (Fla. 1950), judg.

vacated and remanded, 340 U. S. 848, judg. aff’d,

54 So. 2d 114 (1951), cert denied, 342 U. S. 946 14

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ................................ 9

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 ............. 9,10,13

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 ........................ 11

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ............................ 9,13,14

Sweeney v. Louisville, 102 F. Supp. 525 (W. D. Ky.

1951), aff’d, per curiam sub nom. Muir v. Louis

ville Park Theatrical Assn., 202 F. 2d 275 (C. A.

6th 1953), judg. vacated and remanded, 347 U. S.

971............................................................................. 14

Ill

Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission, 334 U. S. 410

Williams v. Kansas City, 104 F. Supp. 848 (W. D.

Mo. 1952) aff’d, 205 F. 2d 47 (C. A. 8th 1953), cert,

denied, 346 U. S. 826 ...............................................

Other Authority

Robertson and Kirkham, Jurisdiction of the Supreme

Court of the United States, §314 (1951) .............

PAGE

11

13,14

14

•Untteii Stall's (Court of Apprab

For the Fourth Circuit

o-

No. 6903

B obert M. Dawson, Jr., et ah,

vs.

Appellants,

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City, City H all,

Baltimore, Maryland, et al.

Appellants,

------------------ o------------------

No. 6904

Milton L onesome, et ah,

vs.

Appellants,

B. B rooke Maxwell, et ah,

Appellees.

-----------------------------o-----------------------------

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

The Dawson Case.

Appellants filed their complaint in the instant case on

May 16, 1952, on behalf of themselves and other Negroes

similarly situated seeking injunctive relief and a declara

tory judgment against appellees, the Mayor and City Coun

cil of Baltimore, the City Director of the Department of

Becreation and Parks, the Board of Becreation and Parks

2

and Sun and Sand, Inc., a corporation which operates a

concession at Fort Smallwood Park under the control and

supervision of the Board of Becreation and Parks. As the

grounds for relief it was alleged that the maintenance of

racially segregated public beach and bathing facilities in

Fort Smallwood Park constituted a denial of the rights of

appellants and other Negroes to equality under the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States (la).

In their answer appellees admitted that racial segrega

tion was enforced with respect to the use of beach and

bathing facilities at Fort Smallwood Park and alleged

that such segregation was consistent with their obligations

imposed by the Fourteenth Amendment in that the physical

facilities in question were equal in all respects (10a).

On May 27, 1954, subsequent to the decision by the

United States Supreme Court in the School Segregation

Cases (Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483;

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497), appellants filed a motion

for judgment on the pleadings on the ground that the seg

regation complained of in and of itself, without more, vio

lated the Fourteenth Amendment (15a).

On June 18, 1954, all parties entered into stipulations

(16a) in which it was agreed that the beach and bathing

facilities at Fort Smallwood Park were physically equal

so that there was no question of physical inequality in

volved in the case at the time of decision by the trial court,

nor is such question present in this appeal.

On June 22,1954 (41a) a consolidated hearing on appel

lants’ motion for judgment in this and in its companion

case, infra, was held in the court below. On July 27, 1954,

the court filed its opinion denying appellants’ motion on

the ground that the United States Supreme Court deci

sions in the School Segregation Cases did not bar any and

all state-imposed segregation, and that segregation im

3

posed with respect to recreational facilities had not been

outlawed by those decisions (44a). The lower court’s

opinion is reported at 123 F. Supp. 193.

On August 25, appellants filed a motion for final judg

ment (69a), and on the same date such final order was

issued and appellants’ complaint was dismissed with costs

(69a). Whereupon, appellants brought the cause here and

their notice of appeal was filed on September 17, 1954.

The Lonesome Case.

Appellants filed their complaint here on August 8, 1952

(18a). This is also a class suit filed pursuant to Rule 23a

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure on behalf of

appellants and all other Negroes similarly situated.

In this case, as in the companion case, supra, appel

lants seek injunctive relief and a declaratory judgment

against appellees, the State Commissioners of Forest and

Parks and the Superintendent of Sandy Point State Park

and Beach, on the ground that the maintenance of segre

gated beach and bathing facilities at Sandy Point State

Park and Beach constitute a violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

On September 30, 1952, appellees filed their answer in

which they maintained that East Beach, the beach main

tained and operated by the State at Sandy Point State

Park for the exclusive use of Negroes, was equal in all

respects to the South Beach maintained in said State Park

for the exclusive use of white persons (25a). A preliminary

injunction was issued on June 2, 1953, on the grounds that

such facilities were not physically equal and was vacated

on July 9, 1953, on the ground that improvements at East

Beach, operated for Negroes, undertaken by the State had

made it equal to the South Beach maintained for white

persons (29a).

On. May 29, 1954, appellants filed a motion for judg

ment on the pleadings (38a) and on June 18 all parties

stipulated that as between East Beach and South Beach

there was equality with respect to physical facilities (40a).

On July 27th, after hearing (41a), appellants’ motion for

judgment was denied (44a). The opinion of the trial court

is reported at 123 F. Supp. 193. On August 25th appel

lants filed a motion for final judgment (70a) and final judg

ment was entered the same day dismissing appellants’ com

plaint (70a) with costs. Whereupon, appellants filed a

notice of appeal on September 17, 1954 and brought the

cause here.

The two cases were consolidated for argument in this

Court as in the court below, and this consolidated brief is

being filed for both appeals.

Question Presented

The two appeals raise the same question, namely, may

a state, consistent with the requirements of the Fourteenth

Amendment, enforce a policy of racial segregation in the

use and enjoyment of public beach and bathing facilities?

Or to put it another way, does the Fourteenth Amendment

deprive the state of power to maintain a policy of racial

segregation with respect to public recreational facilities,

even though separate facilities are provided for Negroes

which are physically equal to those provided for white

persons?

Statement of Facts

This case has a long history, but the essential facts are

not in dispute. Beach and bathing facilities were provided

at Fort Smallwood Park, a municipally-owned and oper

ated park for the recreation of the citizens of the City of

5

Baltimore. These facilities were for the exclusive use of

white persons, and no similar facilities were provided in

said park or in any other place for Negroes. Appellants

sought to use the beach and bathing facilities at said park

in the summer of 1950 and were denied such use solely

because they were Negroes (5a-6a). Whereupon, appel

lants instituted proceedings in the court below. On March

2, 1951, the trial court entered judgment for the plaintiffs

and enjoined the defendants from discriminating against

appellants in respect to the public bathing and beach facili

ties maintained at Fort Smallwood Park (6a). The spe

cific order is cited in the defendants’ answer (10a). There

after, during the summer of 1951, Negroes and white

persons used the beach and bathing facilities at Fort Small

wood Park on alternate days in accordance with the sched

ule and policies adopted and enforced by appellees

(6a, 11a).

In 1952 appellees authorized the construction of separate

beach and bathing facilities for Negroes (6a). Appellants

on April 1,1952, demanded of appellees that all of the facili

ties at Fort Smallwood Park be open to all persons without

regard to race or color (7a). Appellees acknowledged this

demand, but the construction of segregated beach and bath

ing facilities for the exclusive use of Negroes continued

and was completed (7a). Appellees have maintained such

segregated facilities for Negroes ever since and have

refused to permit Negroes to use the beach and bathing

facilities which they maintain for white persons (7a, 13a).

The Lonesome Case.

Here, as in the preceding case, there is no controversy

concerning the basic facts.

Sandy Point State Park and Beach is a public recrea

tional center owned and operated by the State of Mary

land. All the facilities in said park are open to all persons

6

without segregation or discrimination with the exception

of the beach and bathing facilities. The state maintains

and operates segregated beach and bathing facilities for

Negro and white persons. It maintains and operates South

Beach for the exclusive use of white persons, and it main

tains and operates East Beach for the exclusive use of

Negroes (21a, 25a-26a).

On July 4, 1952, appellants sought to use the facilities

at South Beach and were denied the use of such facilities

solely because they were Negroes, and they were escorted

to the East Beach by appellees’ employee and agent but

refused to use the East Beach facilities on the grounds that

the segregated facilities would not afford complete and

wholesome recreation (21a-22a).

ARGUMENT

State Imposed Racial Restrictions With Respect to the

Use and Enjoyment of Publicly Owned and Operated

Recreational Facilities Are Forbidden by the Four

teenth Amendment.

1. While there are no state statutes or city ordinances

requiring or specifically authorizing the practices and poli

cies here complained of, implied authority on the part of

these public officials to separate the races exists pursuant

to the delegation to them of the power to control and regu

late the public facilities in question. Durkee v. Murphy,

181 Md. 259, 29 A. 2d 253 (1942). Hence these cases are

unencumbered by problems concerning the local source of

appellees’ power to enforce a policy of racial segregation

with respect to the facilities which are involved in these

appeals.

In both cases bathing facilities—bathhouses and beaches

—are maintained and operated under the supervision and

7

control of state officials for the recreational pleasure of the

general public. At Fort Smallwood Park and at Sandy

Point State Park and Beach public officials seek to enforce

a policy and practice of racial segregation in the use and

enjoyment of bathing facilities under their supervision and

control. The segregated bathing facilities provided for

the exclusive use of Negroes at both resorts are admittedly

physically equal to those available for white persons, so

that the sole issue raised in the trial court and here is

whether such racial segregation is per se a violation of

appellants’ constitutional rights.

Appellants assert here the position which they took in

the court below—that the application of the ratio decedendi

in the School Segregation Cases compels the conclusion

that the racial segregation here complained of constitutes

an unconstitutional deviation from appellees’ obligations

under the Fourteenth Amendment. The trial court took

the position that the “ separate but equal’ ’ doctrine was an

appropriate constitutional yardstick in the field of public

recreation and that the School Segregation Cases had repu

diated the doctrine only as it applied to public schools.

The court below concluded that the decision of this Court

in Boyer v. Garrett, 182 F. 2d 582 (1950), was still con

trolling.

2. We submit that the trial court fell into fatal error

and that its decision should be reversed. In the first place

the court approached decision from a false premise. It

approached decision as if the “ separate but equal’ ’ doc

trine had been adopted by the United States Supreme Court

as an appropriate constitutional yardstick of general appli

cation. If this were true, it would be appropriate to

regard the School Segregation Cases as merely a special

departure from that doctrine in the field of public educa

tion—the view the lower court took. It is unquestionably

true that the lower federal and state courts have assumed

8

at least since 1896 that the “ separate but equal’ ’ had been

approved by the Supreme Court as a doctrine of general

application. Certainly these courts have used it as the

measure of the constitutionality of state-imposed segrega

tion of Negroes in every area of American life. But to

attribute to the United States Supreme Court such all

inclusive approval of the doctrine is to misread the deci

sions of that Court.

On the contrary, the “ separate but equal” doctrine,

which made its first appearance in decisions of the United

States Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537,

and was there used to sustain a state statute requiring

racial segregation in intrastate railroad coaches, has been

utilized by that Court in only a very restricted fashion.

In Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 81, the Court

rejected the doctrine’s application to housing in these

terms:

“ As we have seen, this court has held laws valid

which separated the races on the basis of equal ac

commodations in public conveyances, and courts of

high authority have held enactments lawful which

provide for separation in the public schools of white

and colored pupils where equal privileges are given.

But, in view of the rights secured by the 14th Amend

ment to the Federal Constitution, such legislation

must have its limitations, and cannot be sustained

where the exercise of authority exceeds the restraints

of the Constitution. We think these limitations are

exceeded in laws and ordinances of the character now

before us.”

Despite the lack of intervening developments, sweeping

language in Gong Lum, v. Rice, 275 U. 8. 78, 85, gives the

erroneous impression that the Supreme Court in some pre

vious decision had accepted and applied the “ separate but

9

equal” doctrine as an appropriate guide in the field of

public education. This erroneous impression reappears in

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. 8. 337. But the

facts are as was pointed out in Buchanan v. Warley, supra

—the separate hut equal doctrine has never been extended

by the United States Supreme Court beyond the field of

transportation in any case where such extension has been

contested.

While the doctrine was not specifically repudiated in

the field of public education, where the Supreme Court has

had to determine whether the state has performed its con

stitutional obligations of providing equal educational op

portunities, the “ separate but equal” doctrine has never

been used to sustain the validity of the state’s separate

school law. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada-, supra;

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631; Sweatt v.

Painter, 339 U. S. 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Re

gents, 339 U. S. 637. And, of course, as to public education

the doctrine has now been specifically repudiated. School

Segregation Cases, supra.

Even in the field of transportation, the “ separate but

equal” doctrine has been sapped of vitality. Henderson

v. United States, 339 U. S. 816, in outlawing segregation

of Negroes in railroad dining cars on interstate trains con

stituted in effect a repudiation of Chiles v. Chesapeake &

Ohio Ry., 218 U. S. 71. Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 337,

places persons traveling in interstate commerce beyond the

thrust of state segregation statutes. This Court’s decision

in Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (1951), cert, denied 341

U. S. 941, extended the burden on commerce concept of

the Morgan Case to include burdens incident to enforce

ment of the carriers’ rules and regulations regarding the

seating of white and Negro interstate passengers. Indeed,

Buchanan v. Warley, supra; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IJ. S.

1; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, supra; Sweatt v.

Painter, supra, and the School Segregation .Cases clearly

10

reveal that the ‘ 4 separate but equal” doctrine is a departure

from the main stream of constitutional development as evi

denced by the decisions of the United States Supreme

Court. A reading of Brown v. Board of Education, supra,

makes clear that the Supreme Court views the question in

this light. There it said:

“ In the first cases in this Court construing the

Fourteenth Amendment, decided shortly after its

adoption, the Court interpreted it as proscribing all

state-imposed discriminations ag-ainst, the Negro

race. The doctrine of ‘ separate but equal’ did not

make its appearance in this Court until 1896 in the

case of Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, involving not

education but transportation. American courts

have since labored with the doctrine for over half

a century. In this Court, there have been six cases

involving the ‘ separate but equal’ doctrine in the

field of public education. In Cumming v. County

Board of Education, 175 U. S. 528, and Gong Bum

v. Rice, 275 U. S .78, the validity of the doctrine

itself was not challenged. In more recent cases, all

on the graduate school level, inequality was found

in that specific benefits enjoyed by white students

were denied to Negro students of the same educa

tional qualifications. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v.

Canada, 305 U. S. 337; Sipuel v. Oklahoma, 332

U. S. 631; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629; McLaurin

v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637. In none

of these cases was it necessary to reexamine the

doctrine to grant relief to the Negro plaintiff. And

in Sweatt v. Painter, supra, the Court expressly

reserved decision on the question whether Plessy v.

Ferguson should be held inapplicable to public edu

cation.”

And, we repeat, as to education the doctrine has now

been specifically repudiated. In general governmental

11

restrictions based upon rase are considered irrelevant and

irrational and hence arbitrary exercises of state power

forbidden under the Fourteenth Amendment. See Taka-

hashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 334 U. S. 410 ; Oyama

v. California, 332 U. S. 633.

In determining whether a racially restrictive policy is

permitted under the Fourteenth Amendment, it is sub

mitted that courts should now take the position that except

where the Supreme Court has specifically ruled that the

“ separate but equal” doctrine is applicable, the state policy

in question must be tested by other yardsticks.

3. One such yardstick is the general classification test.

Early in the history of the Fourteenth Amendment, the

Supreme Court held that it was intended to provide equal

protection and security “ to all under like circumstances

in the enjoyment of their personal and civil rights” Bar-

bier v. Connelly, 113 U. S. 27, 31. In effectuating this pur

pose, American courts require that all governmental classi

fications or distinctions must be based upon some real or

substantial difference pertinent to a valid legislative objec

tive. See Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 227 U. S.

389; Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535. This test has

merely restricted state action which was obviously unrea

sonable and patently discriminatory. Indeed, one would

assume, as did Justice Holmes in Nixon v. Herndon, 273

U. S. 536, 541, that the constitutional prohibition against

unreasonable legislative classifications are less rigidly pro

scriptive of state action than the Fourteenth Amendment

prohibitions against color differentiations. There he con

cluded :

“ States may do a good deal of classifying that

it is difficult to believe rational, but there are limits,

and it is too clear for extended argument that color

cannot be made the basis of a statutory classifica

tion affecting the right set up in this case. ’ ’

12

Certainly in view of the uncontroverted historical fact

that the Fourteenth Amendment was intended primarily to

protect Negroes in their rights as citizens, this should have

been the case. The “ separate but equal” doctrine, how

ever, substitutes race for reasonableness as the constitu

tional test of a classification, and the constitutional pro

hibition against racial differentiations become in fact much

less restrictive of governmental action than the constitu

tional prohibition against unreasonable classifications.

In Bolling v. Sharpe, supra, this anomaly seems to have

been removed, and racial classifications are at least sub

jected to the same test of reasonableness as are other legis

lative classifications. There the Court said:

“ Classifications based solely upon race must be

scrutinized with particular care since they are con

trary to our traditions and hence constitutionally

suspect * # *

“ Although the Court has not assumed to define

‘ liberty’ with any great precision, that term is not

confined to mere freedom from bodily restraint.

Liberty under law extends to the full range of conduct

which the individual is free to pursue, and it cannot

be restricted except for a proper governmental objec

tive. Segregation in public education is not reason

ably related to any proper governmental objective,

and thus it imposes on Negro children of the District

of Columbia a burden that constitutes an arbitrary

deprivation of their liberty in violation of the Due

Process Clause.”

Measured by this yardstick, we submit, these regula

tions must fall.

The need to preserve the public peace cannot be used

to justify deprivation of an individual’s constitutional

rights. Buchanan v. Warley, supra; Morgan v. Virginia,

supra. Moreover, argument that racial segregation here is

13

necessary to the preservation of the public peace is seri

ously weakened in the light of the fact that no segregation

whatsoever is practiced with respect to the facilities in

state parks except as to the facilities involved in this appeal.

It should further be remembered, as pointed out in the

opinion below, the patterns of rigid segregation are fast

disappearing throughout the State of Maryland and that

such diverse institutions as the University of Maryland,

Public Housing, The Junior Bar Association, Baltimore’s

Public Schools, and the City’s Public Parks have been

affected by this process. These factors bring into sharp

focus the arbitrary and unreasonable character of the re

strictions of which appellants complain.

Nor should it be forgotten that the rights secured under

the 14th Amendment are personal and present. Sipuel

v. Board of Regents, supra,. And see McKissick v. Car

michael, 181 P. 2d 949 (C. A. 4th 1951). Thus these regu

lations cannot be sustained or any notion concerning what

may or may not be good for the greatest number of Negroes.

Tested by the rules applicable to governmental classifica

tions in general, the regulations which appellees seek to

enforce with respect to the use and enjoyment of bathing

facilities at Fort Smallwood Park and Sandy Point State

Park are unconstitutional.

4. There are no decisions by the United States Supreme

Court specifically approving or repudiating the “ separate

but equal” doctrine in the field of public recreation. Five

cases involving this question have reached the Supreme

Court. In three of these—Boyer v. Garrett, supra; Wil

liams v. Kansas City, 104 F. Supp. 848 (W. D. Mo. 1952),

aff’d 205 F. 2d 47 (C. A. 8th, 1953); and Beal v. Holcombe,

193 F. 2d 384 (C. A. 5th 1951—certiorari was denied. In

Garrett and Beal the state power to impose racial segre

gation pursuant to the “ separate but equal” doctrine was

sustained in the lower court. In the Williams Case injunc

tive relief had been granted which in effect barred racial

14

segregation. In Garrett certiorari was denied, because the

petition was filed too late. 340 U. S. 912. In Beal cer

tiorari was denied, 347 U. S. 947, but petitioner was the

state not the original plaintiff. In Williams certiorari

sought by the city from a lower court judgment required

plaintiff be treated like all other persons was denied. 346

U. S. 826.

A recital of these facts merely serves to underscore the

admonition that such denial means no more than that less

than four justices favored granting of the writ and carries

with it no implications regarding the Supreme Court’s

views on the merits of the case involved. See Mr. Justice

Frankfurter’s separate opinion in Maryland v. Baltimore

Radio Show, Inc., 338 U. S. 912, 919. See also Robertson

and Kirkham, J urisdiction of the Supreme Court of the

U nited States, §314 (1951).

In the other two cases—the only action by the Supreme

Court touching this question—there is some indication of

the Court’s belief that its decisions with respect to the

scope and breadth of “ equal protection” and “ due process”

in the field of education are appropriate guides to deci

sion in the field of public recreation. Rice v. Arnold, 45

So. 2d 195 (Fla. 1950), judg. vacated and remanded, 340

U. S. 848, judg. aff’d, 54 So. 2d 114 (1951), cert, denied,

342 U. S. 946; Sweeney v. Louisville, 102 F. Supp. 525 (W.

D. Ky. 1951), aff’d, per curiam sub nom. Muir v. Louisville

Park Theatrical Assn., 202 F. 2d 275 (C. A. 6th 1953),

judg. vacated and remanded, 347 U. S. 971.

Rice v. Arnold raised the question of the right of

Negroes to use city owned and operated golf links under

the same rules and conditions applicable to all other per

sons. The Supreme Court, after decisions in the Sweatt

and McLaurin cases in 1950, granted certiorari, vacated

the judgment below and remanded the cause for reconsid

eration in the light of the Sweatt and McLaurin decisions.

15

On remand the Florida Supreme Court reaffirmed its prior

judgment and stated that in any event petitioner had mis

conceived his remedy, and that if he sought to challenge

the reasonableness of the judgment, the proper procedure

would have been a bill for declaratory judgment. It was

on this state procedural ground that the Supreme Court

based its refusal to grant certiorari when the ease again

reached the Supreme Court. Justices Black and Douglas

were of the opinion that certiorari should be granted.

In the Muir Case a private theatrical organization oper

ating in a public amphitheater was held both by the trial

court and the Court of Appeals to be outside the reach

of the Fourteenth Amendment when question was raised

concerning its policy of racial discrimination. The Supreme

Court, however, granted certiorari, vacated the judgment

and remanded the cause for “ consideration in the light of

the Segregation Cases * * * and conditions that now pre

vail.” These instances are certainly evidence that the

Court deems the School Segregation Cases have applica

tion in the field of public recreation. Moreover, whatever

the present status of the “ separate but equal” doctrine,

it seems clear that public recreation is far closer to public

education than it is to intrastate commerce. Therefore, it

would seem that the field of public recreation is more likely

to be governed by doctrines applicable to education than

those applicable to intrastate transportation. Under these

circumstances, we submit, it was error for the trial court

to apply the “ separate but equal” doctrine here. Rather

it should have adopted the ratio decedendi in the School

Segregation Cases and struck down appellees’ action as

contrary to the mandate of the Fourteenth Amendment.

16

Conclusion

For the reasons hereinabove stated, we respectfully

submit that the judgment of the court below should be

reversed.

L inwood K oger, Jr.,

1607 West North Avenue,

Baltimore, Md.,

T ucker R. Dearing,

716 North Gay Street,

Baltimore 2, Md.,

R obert L. Carter,

J ack Greenberg,

T hurgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Appellants.

S upreme Printing Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3-2320