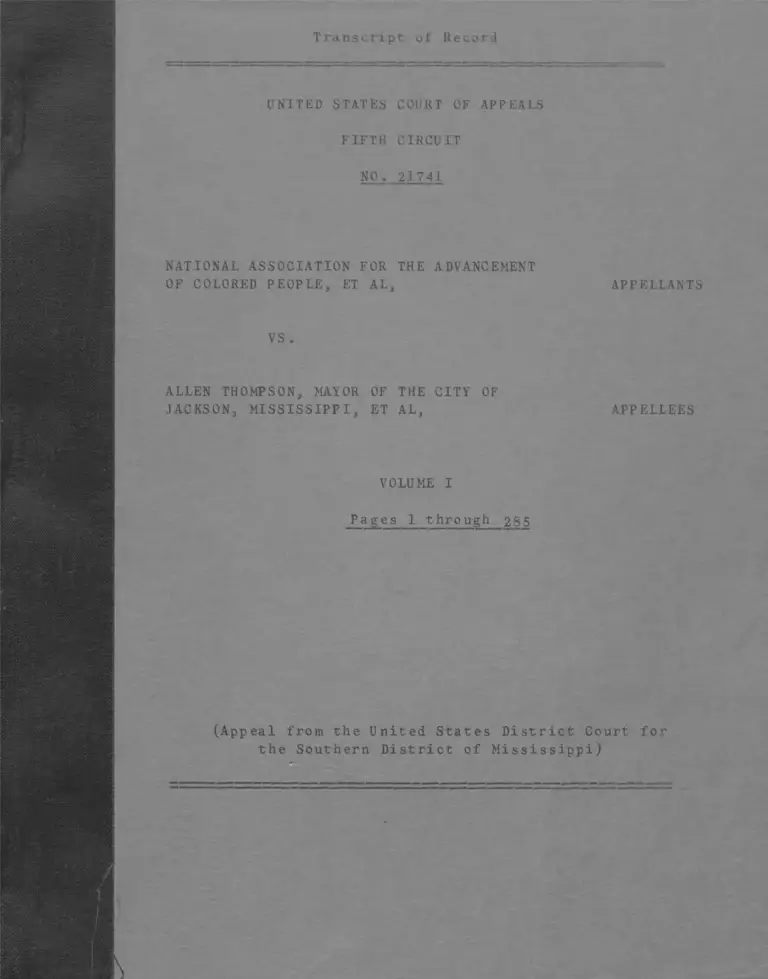

NAACP v. Thompson Transcript of Record Vol. I

Public Court Documents

September 24, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Thompson Transcript of Record Vol. I, 1964. e6bbbe0f-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e54cd323-52a7-4ec5-826f-0fe5607a7551/naacp-v-thompson-transcript-of-record-vol-i. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

T r a n s c r i p t o f R e c o r d

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 2 1 7 41

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE, ET AL,

VS .

ALLEN THOMPSON, MAYOR OF THE CITY OF

JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI , ET AL,

VOLUME I

Pa g e s 1 t h r o u g h 285

( A p p e a l f r o m t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s D i s t r

t h e S o u t h e r n D i s t r i c t o f M i s s i s

-

APPELLANTS

APPELLEES

i c t Court f o r

s i p p i )

VOLUME I

CAPTION

I N D E X

1

Page

1

COMPLAINT 2

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND PRELIMINARY

INJUNCTION WITH ATTACHED AFFIDAVITS AND OTHER

EXHIBITS, JUNE 7, 1 963 , AND ADDITIONAL EXHIBITS A

TO E, FILED JUNE 1 0 , 1963 23

DEFENDANTS' (CITY OF JACKSON) MOTION TO DISMISS vITH

AFFIDAVITS 45

ORDER TAKING CASE UNDER ADVISEMENT FOR LATER DECISION

JUNE 1 1 , 1963 57

PLAINTIFFS’ NOTICE OF APPEAL 59

JUDGMENT OF UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS DISMISSING

APPEAL JULY 2 4, 1963 62

DEFENDANTS' REQUESTS FOR ADMISSIONS, JUNE 1 2 , 1963 65

PLAINTIFFS RESPONSE TO REQUEST FOR ADMISSIONS,

JUNE 2 1 , 1 9 6 3 , JULY 26 , 1963 67 & 70

ANSWER OF ROSS R. BARNETT, JOE T . PATTERSON

AND HEBER LADNER, JUNE 2 7, 1963 76

ANSvvER OF CITY OF JACKSON, AUGUST 3 , 1963 85

ANSwER OF T. B. BIRDSONG, OCTOBER 1 8 , 1963 88

PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR FURTHER HEARING AT EARLY DATE,

AUGUST 5, 1963 91

ORDER OVERRULING MOTION FOR FURTHER HEARING, AU G .17, ’ 63 94

PLAINTIFFS' AFFIDAVITS, JACK YOUNG, SHIRLEY CATCHINGS,

MERCEDES wRIGHT, AUGUST 2 l , 1963 95

DEFENDANTS' OPPOSING AFFIDAVITS, J . L. RAY, S . B.

BARNES, JOHN OSBORNE, R. G. NICHOLS, J R . ,

BEAVERS ARMSTRONG, C. J . HUSBANDS, E. E. SMITH,

D. A . NICHOLS, J . M. wILLIAMS, G. H. BLACKwELL 105

OPINION OF JUDGE COX ON COUNT 1 , JANUARY 1 0 , 1964 117

VOLUME I ( C o n t i n u e d ) I N D E X ( C o n t i n u e d )

IX

P a g e

OPINION OF JUDGE MIZE ON COUNT TnO OF THE

COMPLAINT, JANUARY 1 7 , 1964 125

ORDER DENYING TEMPORARY INJUNCTIONS IN COUNTS I AND

I I , JANUARY 2 3 , 1964

FIRST PRETRIAL ORDER, FEBRUARY 3, 1964 129

ORDER MAKING RESPONSE TO REQUESTS FOR ADMISSIONS

PART OF PROCEEDING, FEBRUARY 3, 1964 131

ORDER SUBSTITUTING DEFENDANT SHERIFF OF HINDS

COUNTY, FEBRUARY 6 , 1964 132

PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION TO AMEND PRAYER OF COUNT 1 OF THE

COMPLAINT, FEBRUARY 2 8 , 1964 132

ORDER GRANTING PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION TO AMEND, FE B. 2 8 , ’ 64 134

OPINION OF COURT DISMISSING COMPLAINT, JUNE 3 , 1964 135

FINAL JUDGMENT, JUNE 5, 1964 164

NOTICE OF APPEAL, JUNE 20 , 1964 164

DESIGNATION OF CONTENTS OF RECORD ON APPEAL,

FILED JUNE 6 , 1964 166

TRANSCRIPT OF HEARING ON JUNE 8, 1963 170

C h i e f w. C. R a y f i e l d ( c a l l e d as a d v e r s e w i t n e s s ) 176

Mayor A l l e n Thompson ( c a l l e d as a d v e r s e w i t n e s s ) 183

d i r e c t t e s t i m o n y 236

r e c r o s s e x a m i n a t i o n 249

r e d i r e c t e x a m i n a t i o n 269

S h e r i f f J . R. G i l f o y ( c a l l e d as a d v e r s e w i t n e s s ) 270

HEARING CONCLUDED 285

I N D E X ( C o n t i n u e d )

1 1 1

TRANSCRIPT OF TESTIMONY OF JAMES BROWN AND LUCIAN

Page

VOLUME I I

RICHARDS IN CIVIL ACTIONS NO . 3430 AND 3431 ON

JUNE 1 2, 1963 286

Dir . Cr . R e d i r . R e c r .

Lu c ia n R i c h a r d s 288 291 297 298

James Brown 299 301 311 311

TRANSCRIPT OF HEARING ON COUNT TWO OF COMPLAINT 312

Dir . Cr . R e d i r . R ecr .

Heber A. Ladner 318

J o e T. P a t t e r s o n 325

M a rt i n R. McLendon 345

P l a i n t i f f s R e st 349

EXHIBIT D- l 350

H e a r i n g C o n c l u d e d 369

ANSWERS

ON ORAL

OF PLAINTIFF

EXAMINATION,

RALPH EDwIN

JANUARY 30,

KING

1964

TO QUESTIONS

370

TRANSCRIPT OF TRIAL, FEBRUARY 3, 4 , 5, 6 , 2 7 , 28 , 1964 392

Dir . Cr . R e d i r . R e c r .

Ruby H u r l e y 2

P l a i n t i f f Ex. 1 396

P l a i n t i f f Ex. 2 3 96

P l a i n t i f f Ex. 3 398

PI s Ex. 4 398

Def enda nt ’ s E x . 1 f o r I d e n . 404

Def enda nt ’ s E x . 2 f o r i d e n . 408

Char l e s E ver s 418 432,4® 457 461

Def enda n t ’ s E x . 3 and 4 f o r i d e n . 438

Def enda n t ’ s Ex . 5 f o r i d e n . 439

D e f e n d a n t T s Ex . 6 f o r i d en 441

Mr s . D o r i s A l l i s o n 475 484 501

497

Rev . R . L . T . Smith 505 529

Verna Anne B a i l e y 546 555 572

I N D_ E X _ ( C o n t i n u e d )

VOLUME I I I

TRANSCRIPT CONTINUED OF TRIAL, FEBRUARY 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ,

2 7 , 2 8 , 1964

Dir . Cr . R e d i r .

Miss Sh i r l e y C a t c h i n g s 574 581

S h i r l e y D o l o r e s B a i l y 597 603 623

B enni e L. C a t c h i n g s 629 637

TUESDAY, FEB. 4 , 1964

Jimmy Lee B e l l 648 652 656

Do r o t hy Ruth B r a c e y 656 670 684

Eddie J ean Thomas 684 695 716

H a t t i e Palmer 721 732 739

M a t t i e B i v i n s Dennis 743 748 757

Theresa Ea s i e y 758 762

A l f o n s o Lewis 771 778 795

D o r i s A n n e t t e E r s k i n e 797 804 817

H e z ekia h Wa tkins 824 835 852

A rv ene Lee Adams 856

i v .

Page

574

648

V

VOLUME IV I N D E X ( C o n t i n u e d ) Page

TRANSCRIPT CONTINUED o f TRIAL OF FEBRUARY 3, 4, 5,

6 , 27 and 28 , 1964 872

Arvene Lee Adams c o n t i n u e d 872

Dir . Cr . R e d i r . R e c r .

Helen O’ Neal 879 886 893

F r a n k i e Adams 894 900 929 935

W i l l Palmer 940 946

B e t t e Anne P o o l e 952 960 980

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 1960 983

John Bromley Garner 985

Memphis Norman 1004 1015 1030

C l e v e l a n d Donald 1030 1033

McHenry Adams 1036 1046

W i l l i e Ludden 1051 1060 1100

D e f ’ s E x s . 8 , 9 , i d e n 1096

R e v . Edwin King 1101 1118

D e f ’ s Ex. 1 0 , i d e n 1126

A l b e r t L a s s i t e r 1162

Dr. A. D. B e i t t e l 1165

I N D E X ( C o n t i n u e d )

v i

Page

VOLUME V.

TRANSCRIPT OF TRIAL OF FEBRUARY 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 2 7 , 2 8 ,

1964 CONTINUED 1171

D i r . C r . R e d i r . R e c r .

A. D. B e i t t e l ( c o n t i n u e d ) 1171 1185 1195

P I . Ex. 6 f o r i d e n 1182

Wade H. Koons 1198

James M. Ward 1205

P I . Ex. 7 f o r i d e n 1206

P i . Ex. 8 f o r i d e n . 1210

P I . Ex. 9 t h r o u g h 17 f o r i d e n 1213

Thomas T . E t h r i d g e 1216

P I . Ex. 18 f o r i d e n . 1217

C h a r l e s M. H i l l s 1217

P I . Ex. 19 f o r i d e n . 1218

Fred A . Ro s s 1220

Ex. 20 f o r i d e n . 1223

Garner M. L e s t e r 1223

James W a l t e r S ch i mp f 1227

P I . Ex. 21 f o r i d e n . 1230

P i . Ex. 22 f o r i d e n . 1232

B o s w e l l S t e v e n s 1232

P I . E x . 2 3 , 2 4 f o r i d e n . 1235

Gene A u s t i n T r i g g s , S r . 1235

P I . Ex. 25 f o r i d e n . 1236

Mrs . K a t h e r i n e Gr ay s on K e n d a l l

1237

P i . Ex. 26 f o r i d e n . 1239

THURSDAY MORNING, FEBRU ARY 6 , 1964 1241

P I . Ex. 27 f o r i d e n . 1244

C h i e f M. B . P i e r c e 1248

C h a r l e s Noland F o r t e n b e r r y 1253

Le ona rd H. J o r d a n , J r . 1272

Mayor A l l e n C. Thompson 1280

Cha s . Noland F o r t e n b e r r y 1292

J u l i e n R u n d e l l Tatum 1298

Gordon H end erson 1316

J a c k Young 1332 1342 1351 1358

PLAINTIFFS REST 1368

D e f . Ex. 8 , 9 i n e v i d e n c e 1371

James L. B l a c k 1380 1458

D e f . Ex. 11 t h r u 15 f o r i d e n • 1380

D e f . Ex. 16 1394

D e f . E x . 17 1406

D e f . E x . 18 1421

Def . E x . 19 1430

VOLUME VI I N D_E X _ ( C o n t i n u e d )

V l l

Pape

TRANSCRIPT OF TRIAL CONTINUED OF FEBRUARY 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ,

2 7 , 2 8 , 1964-

D i r . C r . R e d i r . R e c r .

J . L. 1Bla cl< ( c o n t i n u e d ) 1469 1472 1479

THURSDAY , FEBRUARY 27 , 1964 1484

E x . ( Def . ) D-20 1484

Def . Exs . D - 2 1 , D - 2 2 , D- 2 3 1485

Def . Exs . D- 24 , D-25, D-26 1487

Def . Ex. 27 1488

Def , E x . 28 1489

Def . E x . 29 1490

Def . Ex . 3 1 , Ex. 32 1491

Def . E x . 33 , Ex. 34 1492

Def . E x . 3 5 , Ex. 36 1493

Def . Ex . 3 7 , Ex. 38 1494

Def . Exs . 39 , 40 , 41 1495

Def . Exs 4 2 , 43 1496

Def . Exs . 4 4 , 45 1497

Def . Exs . 4 6 , 47 1498

Def . Exs . 4 8 , 49 1499

Def . E x . 50 1500

Def . E x . 4 marked i n e v i d en<; e 1500

Def . Exs . 5 , 6 , 7, 10 , 3 i n e v i d enc e 1501

Def . Exs . 5 1 , 52 1504

Mr . Jo hn L . Ray 1505 1560

Mr . C l i f f Bingham 1604 1616 1628

Mr . W. C . Sho emak er 1630 1643

Mr. Be av er s A rmst ro ng 1652 1665

J udg e C a r l Gu ernsey 1673 1684

Mr . S . B . Barnes 1687 1697

Def . e x . 54 1689

Mr . C h a r i e s Evers 1701

Def . E x . 55 1691

Def . E x . 56 1692

Def . Ex . 57 1693

Def . E x . 58 1708

Def . 1 1 , 1 2 , 1 3 , 1 4 wi t hd r awn 1710

Mayo r A l l e n Thompson 1711

P l a i n t i f f Ex. 28 1739

P l a i n t i f f Ex. 29 1741

Mr . Ja ck Yo ung 1743

TRIAL ENDED ! 7 6 2

CERTIFICATE OF PRINTER PREPARING RECORD 1763

1

MEMORANDUM FOR CLERK, UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

APPEAL FROM THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI ,

JACKSON DIVISION

NO. 2 1 7 4 1

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE, ET AL, APPELLANTS

VS .

ALLEN THOMPSON, MAYOR OF THE CITY OF

JACKSON, MI SSISSIPPI , ET AL, APPELLEES

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANTS:

J a c k H. Y oung , C a r s i e A. H a l l , 115^ North F a r i s h S t . ,

J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i

R. J e s s Brown, 125^ North F a r i s h S t . , J a c k s o n , M i s s .

R o b e r t C a r t e r and Barbara M o r r i s , 20 West 4 0t h S t . ,

New Y o r k , New York

D e r r i c k A. B e l l , 10 Columbus C i r c l e , New Y o r k , N.Y.

^Jack G r e e n b e r g , L e r o y D. C l a r k , 10 Columbus C i r c l e ,

New Y o r k , New York

W i l l i a m R. Ming, J r . , 123 West Madison S t r e e t , C h i c a g o ,

I l l i n o i s

Frank D. R e e v e s , 508 F i f t h S t r e e t , N. W. , W a s h i n g t o n ,

D. C .

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEES:

< / Thomas H. W a t k i n s , P. 0 . Box 6 5 0 , J a c k s o n , M i s s .

E. W. S t e n n e t t , C i t y A t t o r n e y , J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i

J . A. T r a v i s , J r . , E l e c t r i c B u i l d i n g , J a c k s o n , M i s s .

R o b e / t G. N i c h o l s , J r . , Lamar L i f e B u i l d i n g ,

I _ Jac /kson, M i s s i s s i p p i

Jk. ^

M a r t i n .JL.—McLendon, A s s i s t a n t A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l o f

t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i , J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i

2 .

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

JACKSON DIVISION

(FILED JUN 7 1963)

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE, A New York C o r p o r a t i o n ;

ROY WILKINS; MEDGAR EVERS; WILLIE B . LUDDEN;

REV. RALPH EDWIN KING; DORIS ERSKINE and

DORIS ALLISON,

P l a i n t i f f s ,

v .

ALLEN THOMPSON, Mayor o f t h e C i t y o f J a c k s o n ,

M i s s i s s i p p i ; D. L. LUCKEY, TOM MARSHALL,

C i t y C o m m i s s i o n e r s ; W. D, RAYFIELD, C h i e f

o f P o l i c e , C i t y o f J a c k s o n ; J . L . RAY,

Deputy C h i e f o f P o l i c e , J a c k s o n ; M. B.

PIERCE, A s s i s t a n t C h i e f o f P o l i c e , J a c k s o n ;

J . A. TRAVIS, C i t y P r o s e c u t i n g A t t o r n e y ,

J a c k s o n ; R. G. NICHOLS, S p e c i a l C i t y P r o s e

c u t o r ; T. B . BIRDSONG, C om mi s s i o n e r o f S t a t e

Highway P a t r o l m e n ; J . R. GILFOY, S h e r i f f o f

Hinds C o u n t y ; PAUL G. ALEXANDER, County

A t t o r n e y , Hinds C o u n t y , M i s s i s s i p p i ;

HON. ROSS R . BARNETT, G o v e r n o r o f t h e S t a t e

o f M i s s i s s i p p i ; JOE T. PATTERSON, A t t o r n e y

G e n e r a l o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i ; and

HEBER LADNER, S e c r e t a r y o f S t a t e ,

CIVIL ACTION

3432

D e f e n d a n t s .

COMPLAINT

COUNT I

Now come t h e p l a i n t i f f s by t h e i r a t t o r n e y s and com

p l a i n i n g o f t h e d e f e n d a n t s s a y ;

1 . The j u r i s d i c t i o n o f t h i s Court i s i n v o k e d p ursu an t

t o t h e p r o v i s i o n s o f T i t l e 2 8 , U n i t e d S t a t e s C ode , S e c t i o n

1 3 4 3 ( 3 ) . T h i s a c t i o n i s a u t h o r i z e d under T i t l e 4 2 , U n i t e d

S t a t e s C ode , S e c t i o n 1 9 83 , t o be b r ou gh t t o r e d r e s s t h e d e

p r i v a t i o n , under c o l o r o f s t a t e l a w , s t a t u t e , o r d i n a n c e ,

r e g u l a t i o n , c u s to m o f u s a g e , o f r i g h t s , p r i v i l e g e s , and im

m u n i t i e s s e c u r e d by t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n and l aws o f t h e U n i t e d

S t a t e s , t o - w i t , r i g h t s , p r i v i l e g e s , and i m m u n i t i e s mandated

by t h e due p r o c e s s and eq ua l p r o t e c t i o n c l a u s e s o f t h e F o u r

t e e n t h Amendment t o t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s .

2 . The p l a i n t i f f s s p e c i f i c a l l y g o v e r n e d by Count I

h e r e i n a r e :

( 1 ) The N a t i o n a l A s s o c i a t i o n f o r t h e Advancement

o f C o l o r e d P e o p l e , a New York c o r p o r a t i o n ;

( 2 ) Roy W i l k i n s , a r e s i d e n t and c i t i z e n o f the

S t a t e o f New York and o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s ;

( 3 ) Medgar E v e r s , a r e s i d e n t and c i t i z e n o f t h e

S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i and o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s ;

( 4 ) W i l l i e B. Ludden, a r e s i d e n t and c i t i z e n o f

t h e S t a t e o f G e o r g i a and o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s ;

( 5 ) R e v . R al ph Edwin Ki ng , a r e s i d e n t and c i t i z e n

o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i and o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s ;

( 6 ) D o r i s E r s k i n e , a r e s i d e n t and c i t i z e n o f t h e

S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i and o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s ;

3 .

( 7 ) D o r i s A l l i s o n , a r e s i d e n t and c i t i z e n o f t h e

S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i and o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s .

The i n d i v i d u a l p l a i n t i f f s a r e Negro and w h i t e c i t i - ^

zens o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s who b r i n g t h i s a c t i o n t o e n f o r c e

r i g h t s g u a r a n t e e d by t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n and laws o f t h e U n i t e d

S t a t e s on b e h a l f o f t h e m s e l v e s as i n d i v i d u a l s , and a l l o t h e r

p e r s o n s s i m i l a r l y s i t u a t e d , wh ich group o f p e r s o n s i s t o o

numerous t o be b ro u g h t i n d i v i d u a l l y b e f o r e t h i s C o u r t . The

c o r p o r a t e p l a i n t i f f i s a n o n - p r o f i t membership o r g a n i z a t i o n

t h a t b r i n g s t h i s a c t i o n on b e h a l f o f i t s e l f and i t s members

and c o n t r i b u t o r s , b o t h Negro and w h i t e and r e s i d e n t s and non

r e s i d e n t s o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i , t o v i n d i c a t e r i g h t s

p r o t e c t e d under t h e F o u r t e e n t h Amendment t o t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n

o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s . Thus , t h i s i s a c l a s s a c t i o n i n a c c o r d

a nc e w i t h t h e p r o v i s i o n s o f R ul e 2 3 ( a ) ( 3 ) o f t h e F e d e r a l R u l e s

o f C i v i l P r o c e d u r e .

3 . The d e f e n d a n t s under Count I a r e a l l o f f i c e r s ,

a g e n t s o r e m p l oy e es o f t h e C i t y o f J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i , Hinds

C o u n t y , M i s s i s s i p p i , or o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i . A l l e n

Thompson i s t h e Mayor o f t h e C i t y o f J a c k s o n ; D. L. Luckey

and Tom M a r s h a l l a r e C i t y C o m m i s s i o n e r s ; W. D. R a y f i e l d i s

C h i e f o f P o l i c e o f t h e C i t y o f J a c k s o n ; J . L. Ray and M. B,

P i e r c e a r e Deputy C h i e f o f P o l i c e and A s s i s t a n t C h i e f o f

P o l i c e , r e s p e c t i v e l y ; J . A. T r a v i s , i s t h e C i t y P r o s e c u r i n g

4 .

A t t o r n e y ; R. G . N i c h o l s i s t h e S p e c i a l C i t y P r o s e c u t o r ; T. B.

B i r d s o n g i s Co mm is s io ne r o f S t a t e Highway P a t r o l m e n ; J . R.

G i l f o y i s S h e r i f f o f Hinds C o u n t y ; and Paul G. A l e x a n d e r i s

County A t t o r n e y o f s a i d C ount y .

4 . The d e f e n d a n t s , i n d i v i d u a l l y and c o l l e c t i v e l y ,

t o g e t h e r w i t h o t h e r p e r s o n s p u r p o r t i n g t o e x e r c i s e t h e power

and a u t h o r i t y o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i , and a c t i n g under

c o l o r o f s t a t e l a w , s t a t u t e , o r d i n a n c e , r e g u l a t i o n , cus tom and

usage have f o r many y e a r s e x e r c i s e d , and now e x e r c i s e , t h a t

power and a u t h o r i t y t o e f f e c t u a t e and m a i n t a i n t h r o u g h o u t t h e

C i t y o f J a c k s o n t h e most r i g o r o u s and v i r u l e n t f o rm o f r a c i a l

s e g r e g a t i o n now e x i s t i n g in t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s . To e n f o r c e and

m a i n t a i n t h i s p r a c t i c e o f r a c i a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n t h e d e f e n d a n t s

and t h e o t h e r p e r s o n s h e r e i n a b o v e m e n t i on ed deny p l a i n t i f f s

and a l l o t h e r p e r s o n s s i m i l a r l y s i t u a t e d a c c e s s t o p u b l i c

f a c i l i t i e s s o l e l y on t h e b a s i s o f r a c e , and d e t e r m i n e what

p l a c e s o f p u b l i c a c c o m m o d a t i o n s may be used by t h e p l a i n t i f f s

and o t h e r members o f t h e c l a s s t h e y r e p r e s e n t , l i k e w i s e s o l e l y

on t h e b a s i s o f r a c e . D e f e n d a n t s a r e a u t h o r i z e d and r e q u i r e d

t o e f f e c t u a t e and implement t h i s r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n by v a r i o u s

s t a t e c o n s t i t u t i o n a l p r o v i s i o n s and s t a t u t e s , i n c l u d i n g but

n o t l i m i t e d t o , t h e f o l l o w i n g : M i s s . C o n s t i t u t i o n , S e c . 2 2 5 ;

Code o f M i s s i s s i p p i : S e c . 7786 ( s e g r e g a t i o n o f r a c e s on s t r e e t

c a r s and b u s e s ) ; S e c s . 6 8 82 , 6883 ( s e p a r a t e ment al w a r d s ) ; Sec

5 .

6

2 3 5 1 . 5 ( s e p a r a t e r e s t rooms i n r a i l r o a d and bus s t a t i o n

w a i t i n g rooms f o r i n t e r s t a t e p a s s e n g e r s ) ; S e c . 2 0 5 6 ( 7 )

( p u n i s h e s any c o n s p i r a c y t o v i o l a t e t h e s e g r e g a t i o n laws o f

t h e s t a t e ) ; S e c . 3499 ( u n l a w f u l f o r t a x i c a b s t o t r a n s p o r t

w h i t e s and N e g ro es t o g e t h e r ) ; S e c . 7 7 8 7 . 5 ( r e q u i r e s c o n s t r u c

t i o n o f s e p a r a t e w a i t i n g room's by a l l common c a r r i e r s f o r

i n t r a s t a t e p a s s e n g e r s ) ; S e c . 2339 ( misdemeanor t o p u b l i s h or

a d v o c a t e t h e s o c i a l e q u a l i t y o f t h e r a c e s ) ; S e c . 4 0 6 5 . 3

( r e q u i r e s a l l s t a t e o f f i c e r s t o u t i l i z e t h e i r o f f i c e t o main

t a i n s e g r e g a t i o n o f t h e r a c e s ) . In a d d i t i o n , t h e d e f e n d a n t s

make use o f and r e l y upon any and e v e r y s t a t u t e o f t h e S t a t e

o f M i s s i s s i p p i and e v e r y o r d i n a n c e , r u l e or r e g u l a t i o n o f t h e

C i t y o f J a c k s o n which can be t w i s t e d or d i s t o r t e d t o i n t e r f e r e

w i t h , h a r a s s , i n t i m i d a t e or p u n i s h any p e r s o n who r e s i s t s or

o b j e c t s t o t h e p o l i c y o f r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n which d e f e n d a n t s

a r e c o m m i t t ed t o m a i n t a i n . S i m i l a r l y , t h e d e f e n d a n t s a b u se

and s u b v e r t t h e j u d i c i a l p r o c e s s e s o f t h e c o u r t s o f t h e S t a t e

t o t h e same end.

5 . The C o n s t i t u t i o n and laws o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s p r o

h i b i t t h e use o f s t a t e power t o a c h i e v e r a c i a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n

and s e g r e g a t i o n . The c o u r t s o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s , and o f t h e

s e v e r a l s t a t e s , have c o n s i s t e n t l y i n v a l i d a t e d t h e r a c i a l d i s

c r i m i n a t i o n , e n f o r c e d or s u p p o r t e d by s t a t e a u t h o r i t y wh ich

i s p r e c i s e l y t h e use w h i c h t h e d e f e n d a n t s a r e making o f t h e

power o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p o i , w h i c h t h e y a r e a u t h o r i z e d

to e x e r c i s e . The F o u r t e e n t h Amendment t o t he C o n s t i t u t i o n o f

t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s d e n i e s t o e v e r y s t a t e , i n c l u d i n g t h e S t a t e

o f M i s s i s s i p p i , t h e power t o d e p r i v e any p e r s o n o f l i f e ,

l i b e r t y or p r o p e r t y w i t h o u t due p r o c e s s o f law and r e q u i r e s

each s t a t e t o a f f o r d t o e v e r y p e r s o n t h e eq ua l p r o t e c t i o n o f

t h e l a w s . The C o n s t i t u t i o n o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s , t h e C o n g r e s s

o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s and t h e P r e s i d e n t o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s by

e x e c u t i v e o r d e r , have u n an i mo u s l y condemned t h e e x e r c i s e o f

g o v e r n m e n t a l power t o e f f e c t u a t e , m a i n t a i n and a c h i e v e r a c i a l

s e g r e g a t i o n and d i s c r i m i n a t i o n . N o t w i t h s t a n d i n g , t h e d e f e n d

a n t s have c o n t i n u e d and t h r e a t e n t o c o n t i n u e i n t h e f u t u r e a

p o l i c y and p r a c t i c e o f r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n and d i s c r i m i n a t i o n

i n t h e C i t y o f J a c k s o n and i n t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i .

6 . S i n c e on or a b o ut May 27 , 1 9 6 3 , t h e p l a i n t i f f s , or

some o f them, and o t h e r p e r s o n s h a v e , f r o m t i m e t o t i m e ,

p e a c e a b l y a s s e m b l e d i n t h e C i t y o f J a c k s o n t o seek r e d r e s s o f

t h e i r g r i e v a n c e s a r i s i n g f rom t h e i l l e g a l m a i n t e n a n c e and

e n f o r c e m e n t o f r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n by t h e d e f e n d a n t s . P l a i n

t i f f s have e q u a l l y p e a c e f u l l y so ug ht p u b l i c l y t o s t a t e t h e i r

g r i e v a n c e s a r i s i n g f r o m the i l l e g a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n a g a i n s t

N e g r o e s . More s p e c i f i c a l l y , p l a i n t i f f s , or some o f them,

have done t h e f o l l o w i n g :

a . P i c k e t e d p l a c e s o f p u b l i c a c c o m m o d a t i o n s , e . g . ,

7 .

8

s t o r e s and r e s t a u r a n t s , i n J a c k s o n , by w a l k i n g in an o r d e r l y

manner i n sma l l g r o u p s , s i n g l e f i l e , in f r o n t o f such p l a c e s

c a r r y i n g p l a c a r d s r e q u e s t i n g t h e end o f e x c l u s i o n o f Neg ro es

f r om such p l a c e s o f p u b l i c a c c o m m o d a t i o n .

b . E n t e r e d d a c e s o f p u b l i c a cc om m o d a t i o n in

J a c k s o n , and r e q u e s t e d s e r v i c e on a r a c i a l l y i n t e g r a t e d b a s i s

at l u n c h c o u n t e r s . When r e f u s e d s e r v i c e p u rs u an t t o t h e r e

q u i r e m e n t s o f t h e s t a t e s t a t u t e s and t h e o r d e r s and d i r e c t i v e s

o f t h e d e f e n d a n t s , p l a i n t i f f s , or some o f them, have remained

on t h e p r e m i s e s . P l a i n t i f f s ’ r e q u e s t s wer e o r d e r l y and at no

t i m e d i d p l a i n t i f f s b l o c k i n g r e s s o r e g r e s s t o such p l a c e s o f

p u b l i c a c c o m m o d a t i o n .

c . A f t e r a mass m e e t i n g i n a c h u r c h , p l a i n t i f f s ,

o r some o f them, have wa lk ed a l o n g a p u b l i c s t r e e t i n J a c k s o n ,

two a b r e a s t , c a r r y i n g s i g n s a d v o c a t i n g t h e end o f r a c i a l

s e g r e g a t i o n . P l a i n t i f f s o be ye d a l l t r a f f i c s i g n a l s and at no

t i m e b l o c k e d t h e p u b l i c s i d e w a l k i n any manner w h i ch p r e v e n t e d

i t s use by o t h e r p e r s o n s .

d . In s m a l l g ro u p s p l a i n t i f f s , o r some o f them,

have p e a c e f u l l y p r a y e d t o God f o r t h e end o f r a c i a l s e g r e g a

t i o n and p o l i c e b r u t a l i t y i n t h e C i t y o f J a c k s o n on t h e s t e p s

and i n f r o n t o f f e d e r a l and m u n i c i p a l b u i l d i n g s . At no t ime

were t h e e x i t s o r e n t r a n c e s t o such b u i l d i n g s b l o c k e d t o p r e

v e n t p e r s o n s f r o m l e a v i n g or e n t e r i n g .

9 .

7 . D e f e n d a n t s , and each o f them, w e l l know t h a t t h e

p u r p o s e and i n t e n t i o n o f t h e p l a i n t i f f s a r e s o l e l y t o e x e r c i s e

r i g h t s o f p e a c e f u l a s s e m b l y , f r e e d o m o f s p e e c h , and p e t i t i o n

f o r r e d r e s s o f g r i e v a n c e s , a l l o f w h i ch a r e p r o t e c t e d f rom

i n t e r f e r e n c e by f e d e r a l , s t a t e o r l o c a l g o v e r n m e n t a l o f f i c i a l s

by t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n and laws o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s . I n d e e d , on

o r a bout May 2 9 , 1 9 63 , one o f t h e p l a i n t i f f s , Medgar E v e r s ,

o r a l l y r e q u e s t e d a p a r a d i n g p e r m i t f r om t h e d e f e n d a n t , M. D.

P i e r c e , A s s i s t a n t C h i e f o f P o l i c e , who s a i d t h a t d e f e n d a n t

p r o m i s e d t o l o o k i n t o t h e m a t t e r but t o d a t e t h e p l a i n t i f f

Ever s has r e c e i v e d no r e p l y t o h i s r e q u e s t . In f a c t , t h e

g r a n t i n g o f such a pe rmi t would a p p e a r t o be p r o h i b i t e d by

S e c t i o n 2339 o f t h e Code o f M i s s i s s i p p i wh ich makes a d v o c a c y

o f s o c i a l e q u a l i t y o f t h e Negro and w h i t e r a c e s a misdemeanor

and S e c t i o n 4 0 6 5 . 3 , Code o f M i s s i s s i p p i , w h i c h i m p o s es on

d e f e n d a n t s a dut y t o s u p p r e s s and p r o h i b i t any a c t i v i t y which

might b r i n g a b o ut r a c i a l d e s e g r e g a t i o n .

8 . N o t w i t h s t a n d i n g t h e f a c t t h a t t h e d e f e n d a n t s , and

each o f them, w e l l knew, and s t i l l know, t h a t t he s o l e p u r

p o s e o f t h e p l a i n t i f f s i s t o a s s e r t and e x e r c i s e t h e i r r i g h t s

g u a r a n t e e d and p r o t e c t e d by t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n and laws o f t h e

U n i t e d S t a t e s , t h e d e f e n d a n t s , p u r s u a n t t o t h e i r commitment

t o use t h e power o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i t o m a i n t a i n

r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n , have i l l e g a l l y , u n w a r r a n t e d l y and w i t h o u t

10.

j u s t c a u s e i n t e r f e r e d w i t h t h e p l a i n t i f f s , and each o f them,

i n t h e i r e f f o r t s t o e x e r c i s e t h e i r r i g h t s o f f r e e d o m o f

s p e e c h , p e a c e f u l a s s e m b l y and p e t i t i o n f o r r e d r e s s o f t h e i r

g r i e v a n c e s by a s s a u l t i n g p l a i n t i f f s , or some o f them, w i t h

g r e a t v i o l e n c e , d o i n g s e r i o u s b o d i l y harm t o p l a i n t i f f s , or

some o f them; by f o r c i b l y b r e a k i n g up p e a c e f u l g a t h e r i n g s o f

p l a i n t i f f s , o r some o f them, and by f o l l o w i n g a p o l i c y o f

" i n s t a n t a r r e s t " o f p l a i n t i f f s on d i v e r s e c h a r g e s , t o - w i t s

Code o f M i s s i s s i p p i , S e c t i o n 2 0 8 7 . 5 ( B r e a c h o f P e a c e ) ; S e c t i o n

1088 ( R e s t r a i n t o f T r a d e ) ; S e c t i o n 2 4 0 9 . 7 ( T r e s p a s s ) ; O r d i

na nc es o f C i t y o f J a c k s o n , S e c t i o n 594 ( P a r a d i n g w i t h o u t a

L i c e n s e ) ; U n i f o r m T r a f f i c R e g u l a t i o n C ode , S e c t i o n 134

( O b s t r u c t i n g T r a f f i c and P a r a d i n g w i t h o u t a L i c e n s e ) . Such

a r r e s t s have been made by d e f e n d a n t s s o l e l y f o r t h e p u r p o s e

o f h a r a s s i n g and i n t i m i d a t i n g p l a i n t i f f s and even t h o u g h

d e f e n d a n t s w e l l know t h a t under a l l t h e s e c i r c u m s t a n c e s p l a i n

t i f f s ca nn ot be v a l i d l y c o n v i c t e d o f t h e o f f e n s e s c h a r g e d .

9 . More tha n s i x hundred p e r s o n s have been so a r r e s t e d

s i n c e May 2 7 , 1 9 6 3 . In o r d e r t o o b t a i n t h e i r r e l e a s e f rom

c u s t o d y p e r s o n s so a r r e s t e d have been o b l i g e d t o p o s t bonds

i n t h e amount o f $ 1 00 , $500 and $ 1 , 0 0 0 , e a c h , e x c e p t t h a t

c e r t a i n mi no rs have be en r e l e a s e d w i t h o u t b a i l i n t h e c u s t o d y

o f t h e i r p a r e n t s . S t i l l o t h e r m i n o r s , h o w e v e r , d e f e n d a n t s have

r e f u s e d t o r e l e a s e a t a l l . Most o f t h e p e r s o n s so a r r e s t e d have

11.

been t r i e d , f ou nd g u i l t y as c h a r g e d , and have been s e n t e n c e d

to t h e maximum p r o v i d e d under t h e p a r t i c u l a r o r d i n a n c e or

s t a t u t e a l l e g e d l y v i o l a t e d . Though many o f t h e s e p e r s o n s were

a r r e s t e d under i d e n t i c a l c i r c u m s t a n c e s , and t ho ug h t h e r e was

no c o n t r o v e r s y c o n c e r n i n g t h e f a c t s , and t h ou gh c o n v i c t i o n o f

t h e s e p e r s o n s was i n d e r o g a t i o n o f r i g h t s g u a r a n t e e d by t h e

C o n s t i t u t i o n and laws o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s , t h e d e f e n d a n t s have

p e r s i s t e d , and s t i l l p e r s i s t i n r e q u i r i n g t h a t each i n d i v i d u a l

be t r i e d s e p a r a t e l y , and t h a t i f an a p p e a l i s t a k e n , each i n d i

v i d u a l t a k e a s e p a r a t e a p p e a l . Thus , f i n a l a d j u d i c a t i o n o f

p l a i n t i f f s ’ a s s e r t e d c o n s t i t u t i o n a l c l a i m s a r e l o n g d e l a y e d .

Huge e x p e n d i t u r e s o f monies i n c o u r t c o s t s , b a i l and a p p e a l

bonds a r e r e q u i r e d . As a re s u i t , d e f e n d a n t s t h r e a t e n t o d e p r i v e

t h e s e p e r s o n s , or some o f them, o f any p o s s i b i l i t y o f p r e s e r v

i n g and p r o t e c t i n g t h r o u g h t h e j u d i c i a l p r o c e s s t h e i r r i g h t s as

g u a r a n t e e d by t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n and l a w s o f t h e Un i te d S t a t e s .

1 0 . P l a i n t i f f s d e s i r e , and i n t e n d , t o c o n t i n u e t o p r o

t e s t a g a i n s t t h e i l l e g a l use o f s t a t e power by t h e d e f e n d a n t s .

I n so d o i n g , t h e y a r e m e r e l y e x e r c i s i n g r i g h t s g u a r a n t e e d by

t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n and t h e laws o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s . The

d e f e n d a n t s t h r e a t e n t o c o n t i n u e t o h a r a s s , i n t i m i d a t e ,

t h r e a t e n , and o t h e r w i s e deny t o t h e p l a i n t i f f s t h e r i g h t o f

p e a c e f u l a s s e m b l y , t h e r i g h t o f f r e e d o m o f s p e e c h and o f a s s o

c i a t i o n and t h e r i g h t t o a d v o c a t e and t o engage i n l a w f u l

a c t i v i t i e s t o e l i m i n a t e r a c i a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n i n c o n c e r t w i t h

12 .

o t h e r p e r s o n s as g u a r a n t e e d by t h e F o u r t e e n t h Amendment t o

t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s . P l a i n t i f f s have no

a d e q u a t e remedy at law i n t h e c o u r t s o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s

s i p p i or i n t h e c o u r t s o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s save by t h i s s u i t

f o r i n j u n c t i v e and d e c l a r a t o r y r e l i e f .

WHEREFORE, p l a i n t i f f s p r a y on t h e i r b e h a l f and on b e

h a l f o f members o f t h e c l a s s t h a t t h i s Court w i l l :

1 . I m m e d i a t e l y i s s u e a t e m p o r a r y r e s t r a i n i n g o r d e r ,

w i t h o u t n o t i c e , r e s t r a i n i n g d e f e n d a n t s h e r e i n f rom c o n t i n u i n g

t h e c o n d u c t se t f o r t h b e l o w i n p a r a g r a p h s 3a t h r o u g h h;

2 . Advance t h i s c a u s e on t h e d o c k e t and g ra nt a

s p ee dy h e a r i n g a c c o r d i n g t o law and upon such h e a r i n g d e

c l a r e t h e r i g h t s and l e g a l r e l a t i o n s o f t h e p a r t i e s h e r e i n t o

t h e s u b j e c t m a t t e r o f t h i s s u i t in o r d e r t h a t such a c t i o n may

have t h e f o r c e and e f f e c t o f a f i n a l j u d g m e n t ;

3 . Grant a p r e l i m i n a r y and permanent i n j u n c t i o n , a f t e r

a p p r o p r i a t e h e a r i n g , e n j o i n i n g t h e d e f e n d a n t s and each o f

t h e i r a g e n t s , e m p l o y e e s , s u c c e s s o r s , and a l l p e r s o n s i n a c t i v e

c o n c e r t and p a r t i c i p a t i o n w i t h them f r o m :

a . P u r s u i n g a p o l i c y under c o l o r o f s t a t e l a w ,

s t a t u t e , r e g u l a t i o n , c i t y o r d i n a n c e , c us t o m or u sa g e o f d eny

i n g t o t h e i n d i v i d u a l p l a i n t i f f s , t h e c o r p o r a t e p l a i n t i f f ,

i t s o f f i c e r s , members and a l l p e r s o n s a c t i n g i n c o n c e r t w i t h

them f r om p e a c e f u l l y and p u b l i c l y p r o t e s t i n g r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n

1 3 .

as such r i g h t o f p e a c e f u l and p u b l i c p r o t e s t i s p r o t e c t e d by

t h e F o u r t e e n t h Amendment t o t h e U ni t e d S t a t e s C o n s t i t u t i o n .

b . P u r s u i n g a p o l i c y under c o l o r o f s t a t e law and

c i t y o r d i n a n c e o f d e n y i n g t o t h e i n d i v i d u a l p l a i n t i f f s , t h e

c o r p o r a t e p l a i n t i f f , i t s o f f i c e r s and members, and a l l p e r s o n s

a c t i n g i n c o n c e r t w i t h them, t h e r i g h t t o p r o t e s t a g a i n s t

r a c i a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n by p e a c e f u l l y w a l k i n g upon t h e p u b l i c

s i d e w a l k s i n c o n f o r m i t y w i t h a l l l a w f u l r u l e s and r e g u l a t i o n s

w i t h i n t he p o l i c e c ow er o f the S t a t e and not i n c o n s i s t e n t w i t h

r i g h t s s e c u r e d by t h e F i r s t and F o u r t e e n t h Amendments t o t h e

U n i t e d S t a t e s C o n s t i t u t i o n .

c . A r r e s t i n g , under c o l o r o f s t a t e law and c i t y

o r d i n a n c e , t h e i n d i v i d u a l p l a i n t i f f s , t h e members o f t h e

c o r p o r a t e p l a i n t i f f , and a l l o t h e r p e r s o n s a c t i n g in c o n c e r t

w i t h them, t h u s d e n y i n g t h e i r r i g h t p e a c e f u l l y t o p i c k e t in

p r o t e s t a g a i n s t r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n i n p u b l i c and p r i v a t e l y -

owned f a c i l i t i e s and e n t e r p r i s e s by p e a c e f u l l y w a l k i n g upon

t h e s i d e w a l k a d j a c e n t t o such p u b l i c f a c i l i t i e s and p r i v a t e

b u s i n e s s e n t e r p r i s e s .

d . A r r e s t i n g , under c o l o r o f s t a t e l a w , t h e i n d i

v i d u a l p l a i n t i f f s , members o f t h e c o r p o r a t e p l a i n t i f f , and

a l l o t h e r p e r s o n s a c t i n g i n c o n c e r t w i t h them, when such p e r

sons e n t e r p r i v a t e l y - o w n e d b u s i n e s s e s t a b l i s h m e n t s , r e q u e s t

s e r v i c e on a r a c i a l l y d e s e g r e g a t e d b a s i s , and remain on t h e

14 .

p r e m i s e s when d e n i e d s e r v i c e p u rs u an t t o t h e p o l i c y o f t he

C i t y o f J a c k s o n and t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i and o r d e r e d t o

1 e a v e .

e . A r r e s t i n g the i n d i v i d u a l p l a i n t i f f s , members

o f t h e c o r p o r a t e p l a i n t i f f , and p e r s o n s i n a c t i v e c o n c e r t w i t h

them, f o r p e a c e f u l l y p r o t e s t i n g r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n in t h e C i t y

o f J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i .

f . T h r e a t e n i n g , i n t i m i d a t i n g , c o m m i t t i n g or c o n

d o n i n g a c t s o f v i o l e n c e by members o f t h e J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i

P o l i c e F o r c e upon p e r s o n s a r r e s t e d i n p e a c e f u l d e m o n s t r a t i o n s

a g a i n s t r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n .

g . A t t e m p t i n g t o i n t e r f e r e w i t h , e n j o i n , or p r o

h i b i t p e a c e f u l and o r d e r l y d e m o n s t r a t i o n s c o n d u c t e d by t h e

i n d i v i d u a l p l a i n t i f f s , members o f t he c o r p o r a t e p l a i n t i f f and

p e r s o n s a c t i n g i n c o n c e r t w i t h them, which d e m o n s t r a t i o n s a r e

p r o t e c t e d by t h e F o u r t e e n t h Amendment t o t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s Con

st i t u t i o n .

h . P r o c e e d i n g w i t h t h e p r o s e c u t i o n s o f a l l p l a i n

t i f f s who have b e e n a r r e s t e d but no t t r i e d or c o n v i c t e d f o r

p a r t i c i p a t i n g i n t h e p e a c e f u l d e m o n s t r a t i o n s a g a i n s t r a c i a l

s e g r e g a t i o n i n v o l v e d h e r e i n .

COUNT I I

Now come t h e p l a i n t i f f s , t h e N a t i o n a l A s s o c i a t i o n f o r

t h e Advancement o f C o l o r e d P e o p l e , a New York c o r p o r a t i o n ;

1 5.

Roy W i l k i n s , i t s E x e c u t i v e S e c r e t a r y , a r e s i d e n t o f t he S t a t e

o f New Y o r k ; Medgar E v e r s , i t s F i e l d S e c r e t a r y f o r t h e S t a t e

o f M i s s i s s i p p i , a r e s i d e n t o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i ; and

t h e members o f s a i d p l a i n t i f f o r g a n i z a t i o n who a r e r e s i d e n t s

and c i t i z e n s o f t h e v a r i o u s s t a t e s o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s ,

i n c l u d i n g t he S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i , by t h e i r a t t o r n e y s , and

s t a t e as f o l l o w s :

1 . A l l o f t h e a l l e g a t i o n s o f Count I a r e r e a l l e g e d ,

a d o p t e d and a r e made a p a r t o f Count I I as i f t h e s e a l l e g a t i o n s

were s e t out v e r b a t i m h e r e i n .

2 . The above - named p l a i n t i f f s have r i g h t s and i n t e r

e s t s i n common, and t h e y c o n s t i t u t e a number t o o l a r g e t o be

b r o u g h t b e f o r e t h i s C o u r t . They a r e a l l s e e k i n g t o e n f o r c e

c o n s t i t u t i o n a l r i g h t s g u a r a n t e e d under t h e F o u r t e e n t h Amend

ment t o t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s . These p l a i n

t i f f s c o n s t i t u t e a c l a s s under t h e p r o v i s i o n s o f R u le 2 3 ( a ) ( 3 )

o f t h e F e d e r a l R u l e s o f C i v i l P r o c e d u r e and b r i n g t h i s a c t i o n

f o r t h e m s e l v e s and on b e h a l f o f a l l members o f t h e c l a s s

s i m i l a r l y s i t u a t e d .

3 . The d e f e n d a n t s a r e a l l t h o s e s p e c i f i e d in Count

I a b o v e . In a d d i t i o n , p l a i n t i f f s c o m p l a i n o f R o ss R. B a r n e t t ,

G o v e r n o r and C h i e f E x e c u t i v e o f f i c e r o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s

s i p p i ; J o e T. P a t t e r s o n , A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l o f t h e S t a t e o f

M i s s i s s i p p i , who i s c h a r g e d w i t h t h e d ut y o f p r o s e c u t i n g

f o r e i g n c o r p o r a t i o n s , p r e s e n t l y d o i n g b u s i n e s s i n t h e S t a t e

o f M i s s i s s i p p i , t h a t have f a i l e d t o comply w i t h laws a p p l i c a b l e

t o such f o r e i g n c o r p o r a t i o n s ; and Heber L a d n e r , t h e S e c r e t a r y

o f S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i , c h a r g e d w i t h t h e r e s p o n s i b i l i t y o f

r e g i s t e r i n g f o r e i g n c o r p o r a t i o n s t h a t meet t h e r e q u i r e m e n t s o f

M i s s i s s i p p i l a w .

4 . The p l a i n t i f f , t h e N a t i o n a l A s s o c i a t i o n f o r the

Advancement o f C o l o r e d P e o p l e , has d u l y c o m p l i e d w i t h a l l t h e

laws o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i a p p l i c a b l e t o f o r e i g n n o n p r o

f i t c o r p o r a t i o n s . I t f i l e d i t s A r t i c l e s o f I n c o r p o r a t i o n w i t h

d e f e n d a n t , Heber L a d n e r , S e c r e t a r y o f S t a t e i n December , 1 9 62 ;

t e n d e r e d t o him t h e r e q u i s i t e f i l i n g f e e s , and f u r n i s h e d him

w i t h a l l t h e data r e q u i r e d by l a w . I t a l s o d e s i g n a t e d an

a g e n t f o r t h e s e r v i c e o f p r o c e s s , t o w i t , Medgar E v e r s , a

p l a i n t i f f h e r e i n . However , n o t w i t h s t a n d i n g i t s c o m p l i a n c e a l l

t h e l e g a l p r e r e q u i s i t e s f o r d u l y q u a l i f y i n g t o do b u s i n e s s i n

t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i , t h e c o r p o r a t e p l a i n t i f f has r e c e i v e d

no c o m m u n i c a t i o n f r om t h e S e c r e t a r y o f S t a t e or any o t h e r

r e s p o n s i b l e s t a t e o f f i c i a l s c o n c e r n i n g i t s r e g i s t r a t i o n . I t

has made v a r i o u s i n q u i r i e s t o d e t e r m i n e what a c t i o n has been

t a k e n , but t o no a v a i l .

5. The b a s i c p u r p o s e s and o b j e c t i v e s o f t h e p l a i n t i f f

o r g a n i z a t i o n , i t s o f f i c e r s and members, a r e t o i m p r o v e t h e

s t a t u s o f N e g r o e s i n Amer i can l i f e . A c h i e f o b j e c t i v e ,

16 .

1 7 .

t h e r e f o r e , i s t h e e l i m i n a t i o n o f a l l f orms o f r a c i a l s e g r e

g a t i o n and d i s c r i m i n a t i o n e x t a n t i n t h e U ni t e d S t a t e s ,

i n c l u d i n g the S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i . The p l a i n t i f f c o r p o r a

t i o n i s a n o n - p r o f i t membership o r g a n i z a t i o n composed o f a

l a r g e number o f members, o p e r a t i n g t h r o u g h c h a r t e r e d a f f i l i

a t e s i n 45 o f t h e 50 s t a t e s o f t h e U ni o n . I t f u n c t i o n s in

t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i t h r o u g h v a r i o u s c h a r t e r e d a f f i l i a t e s ,

d e s i g n a t e d as b r a n c h e s , y o u t h c o u n c i l s and c o l l e g e c h a p t e r s

l o c a t e d i n t h e v a r i o u s c i t i e s and towns o f t h e S t a t e o f Mis

s i s s i p p i . These l o c a l a f f i l i a t e s have come t o g e t h e r i n a

s t a t e w i d e o r g a n i z a t i o n known as t h e M i s s i s s i p p i S t a t e C o n f e r

ence o f Branches whose p u r p o s e and f u n c t i o n i s t o e f f e c t u a t e

on a s t a t e w i d e b a s i s t h e b a s i c p u r p o s e s and o b j e c t i v e s o f t h e

p l a i n t i f f o r g a n i z a t i o n . A l l o f t h e a f f i l i a t e s named h e r e i n

a r e u n i n c o r p o r a t e d a s s o c i a t i o n s . In a d d i t i o n , t h e p l a i n t i f f

c o r p o r a t i o n m a i n t a i n s an o f f i c e i n J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i , headed

by t h e p l a i n t i f f , Medgar E v e r s , F i e l d S e c r e t a r y , whose f u n c t i o n s

and d u t i e s a r e t o a s s i s t t h e l o c a l a f f i l i a t e s i n d e v i s i n g and

i m p l e m e n t i n g a l o c a l and s t a t e w i d e prog ra m t o a d v a n c e t h e

o b j e c t i v e s o f t h e p l a i n t i f f c o r p o r a t i o n , t o e l i m i n a t e a l l

f orms o f r a c i a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n and t o s e c u r e f o r Negro r e s i

d e n t s o f M i s s i s s i p p i a l l t h e r i g h t s g u a r a n t e e d under t h e Con

s t i t u t i o n o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s .

) 6 . The p l a i n t i f f c o r p o r a t i o n , o p e r a t i n g t h r o u g h i t s

19 .

t he r i g h t s o f Negro c i t i z e n s under t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n , and t o

t h a t end a r e e n g a g i n g and have engaged i n l a w f u l group a c t i v i t y ,

i n c l u d i n g t he a d v o c a c y o f equal t r e a t m e n t , p u b l i c p r o t e s t

a g a i n s t r a c i a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n , a t t e m p t s t o s e c u r e t h e removal

o f b a r r i e r s t o t h e r e g i s t e r i n g and v o t i n g by N e g r o e s , p e a c e f u l

p i c k e t i n g and o t h e r l a w f u l means t o s e c u r e t h e e l i m i n a t i o n o f

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n i n t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i .

P l a i n t i f f , Roy W i l k i n s , t h e E x e c u t i v e S e c r e t a r y o f

t h e p l a i n t i f f c o r p o r a t i o n , and Medgar E v e r s , F i e l d S e c r e t a r y

o f t h e p l a i n t i f f c o r p o r a t i o n , a r e w e l l known t o d e f e n d a n t s as

o f f i c e r s o f t h e p l a i n t i f f c o r p o r a t i o n . A l t h o u g h t h e y c l e a r l y

were engaged i n p e a c e f u l p i c k e t i n g and t h e d i s s e m i n a t i o n o f

i d e a s g u a r a n t e e d under t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n o f t h e U ni t e d S t a t e s ,

p l a i n t i f f s W i l k i n s and E ver s wer e a r r e s t e d and c h a r g e d w i t h a

v i o l a t i o n o f t h e M i s s i s s i p p i s t a t u t e , S e c t i o n 1 0 8 8 , Code o f

M i s s i s s i p p i , s o l e l y b e c a u s e t h e y a r e o f f i c e r s o f t h e p l a i n t i f f

c o r p o r a t i o n and b e c a u s e , as s u c h , t h e y wer e a t t e m p t i n g t o

e f f e c t u a t e t h e aims and p u r p o s e s o f t h e p l a i n t i f f c o r p o r a t i o n

t o a c h i e v e e q u a l c i t i z e n s h i p r i g h t s f o r N e g r o e s i n t h e S t a t e

o f M i s s i s s i p p i .

8 . The d e f e n d a n t s e x p r e s s l y a r e o p p o s e d t o p l a i n t i f f s ’

a ims and p u r p o s e s . D e f e n d a n t s a r e c o mm it te d t o a c o u r s e o f

c o n d u c t d e s i g n e d t o i mpe de , f r u s t r a t e and d e f e a t t h e impl emen

t a t i o n o f t h e o b j e c t i v e s o f r a c i a l e q u a l i t y a d v o c a t e d by t h e

p l a i n t i f f s as se t f o r t h i n Count I , and m o r e o v e r , a r e s p e c i f i

c a l l y r e q u i r e d by s t a t e law ( S e c . 4 0 6 5 . 3 , Code o f M i s s . ) t o use

t h e i r o f f i c e s t o p e r p e t u a t e r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n , s up r a , i n d e r o

g a t i o n o f t h e i r c o n s t i t u t i o n a l o b l i g a t i o n s mandated under t h e

F o u r t e e n t h Amendment t o t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n o f t he U n i t e d S t a t e s .

De f en da nt s have f a i l e d t o r e g i s t e r t h e p l a i n t i f f as a f o r e i g n

c o r p o r a t i o n , and by t h e a r r e s t and f i l i n g o f c h a r g e s a g a i n s t

t h e p l a i n t i f f s W i l k i n s and Ever s and by s e c u r i n g an ex p a r t e

i n j u n c t i o n o f b r oa d and va gu e d i m e n s i o n s i n a p p a r e n t r e s t r a i n t

o f p l a i n t i f f s ’ l a w f u l a c t i v i t i e s , a r e o p e n l y i n t e r f e r i n g w i t h

t h e l a w f u l a c t i v i t i e s o f t h e p l a i n t i f f o r g a n i z a t i o n , i t s mem

b e r s and o f f i c e r s , and a r e t h r e a t e n i n g t o p r o s e c u t e p l a i n t i f f s

under t h e a f o r e s a i d law and i n j u n c t i o n .

WHEREFORE, p l a i n t i f f s p r a y on t h e i r own b e h a l f and on

b e h a l f o f members o f t h e c l a s s t h e y r e p r e s e n t , t h a t t h i s

Court w i l l :

1 . Advance t h i s c a u s e on t h e d o c k e t and g ra nt a

s p ee dy h e a r i n g a c c o r d i n g t o law and upon such h e a r i n g d e c l a r e

t h e r i g h t s and l e g a l r e l a t i o n s o f the p a r t i e s h e r e i n t o t h e

s u b j e c t m a t t e r o f t h i s s u i t i n o r d e r t h a t such a c t i o n may

have t h e f o r c e and e f f e c t o f a f i n a l j u d g m e n t ;

2 . I m m e d i a t e l y i s s u e a t e m p o r a r y r e s t r a i n i n g o r d e r ,

w i t h o u t n o t i c e and a p r e l i m i n a r y and p ermanent i n j u n c t i o n t o

r e s t r a i n t h e d e f e n d a n t s , t h e i r a g e n t s , s e r v a n t s , e m p l o y e e s ,

20 .

21.

s u c c e s s o r s , a t t o r n e y s , o r any p e r s o n or p e r s o n s in a c t i v e c o n

c e r t w i t h them, i n d i v i d u a l l y and c o l l e c t i v e l y f r o m :

a . r e f u s i n g to r e g i s t e r t h e p l a i n t i f f c o r p o r a t i o n as

d u l y q u a l i f i e d t o do b u s i n e s s i n t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i ;

b . t a k i n g any a c t i o n in t h e c o u r t s o f t h e Un i te d

S t a t e s or t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i t o e n j o i n or bar t h e p l a i n

t i f f c o r p o r a t i o n , o r i t s members f r om c o n d u c t i n g i t s b u s i n e s s

o r f r o m p u r s u i n g t h e i r l a w f u l o b j e c t i v e s w i t h i n t h e S t a t e o f

M i s s i s s i p p i , i n c l u d i n g t h e e n c o u r a g e m e n t , o r g a n i z a t i o n and

p a r t i c i p a t i o n i n d e m o n s t r a t i o n s and a c t i v i t i e s d e s i g n e d t o end

r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n i n J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i ;

c . p r o c u r i n g an i n d i c t m e n t or f u r t h e r p r o s e c u t i n g

p l a i n t i f f s Roy W i l k i n s and Medgar Ever s f o r t h e i r a l l e g e d

v i o l a t i o n , on or a b o ut June 1 , 1 9 6 3 , at J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i ,

o f T i t l e 8 , S e c t i o n 1 0 8 8 , Code o f M i s s i s s i p p i ;

d . p r o c e e d i n g to p r o s e c u t e f u r t h e r t h e B i l l f o r

I n j u n c t i o n f i l e d by t h e C i t y o f J a c k s o n June 6 , 1 9 6 3 , i n t he

Cha nce ry Court o f t h e F i r s t J u d i c i a l D i s t r i c t o f Hinds C o u nt y ,

M i s s i s s i p p i a g a i n s t p l a i n t i f f s and o t h e r s (No. 6 3 , 4 2 9 ) and

f r om e n f o r c i n g t h e Temporary W r i t o f I n j u n c t i o n e n t e r e d in

s a i d c a u s e ex p a r t e and w i t h o u t n o t i c e , June 6 , 1 9 6 3 , by

C h a n c e l l o r J . L. S t e n n e t ;

e . and f o r such o t h e r and f u r t h e r r e l i e f as t h e Court

may deem p r o p e r .

22

JACK H . YOUNG

CARSIE A. HALL

115^ North F a r i s h S t r e e t

J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i

ROBERT L. CARTER

BARBARA A. MORRIS

20 West 4 0t h S t r e e t

New York 1 8 , New York

R. JESS BROWN

1252: North F a r i s h S t r e e t

J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i

JACK GREENBERG

LEROY D. CLARK

DERRICK A. BELL

10 Columbus C i r c l e

New York 1 9 , New York

FRANK D. REEVES

508 F i f t h S t r e e t , N .W .

W a s hi n gt o n 1 , D. C.

WILLIAM R . MING, J R .

123 West Madison S t r e e t

C h i c a g o , I l l i n o i s

A t t o r n e y s f o r P l a i n t i f f s

BY : / s ( C a r s i e A. H a l l_____

VERIFICATION

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI )

) SS.

COUNTY OF HINDS )

Medgar E v e r s , b e i n g f i r s t d u l y sworn, says t h a t he i s

one o f t h e p l a i n t i f f s i n t h i s c a u s e , and t h a t he has r e a d t h e

a b o v e and f o r e g o i n g c o m p l a i n t , and t h a t a l l of t h e a l l e g a t i o n s

c o n t a i n e d t h e r e i n a r e t r u e t o t h e b e s t o f h i s i n f o r m a t i o n ,

kn o wl ed g e and b e l i e f

(R30)

BY__ / s / Medgar W. Evers__________

Sworn and s u b s c r i b e d t o b e f o r e

me t h i s 6t h day o f June 1 9 63 .

/ s / H. C. Latham_____________

Not ary P u b l i c

My Commiss ion e x p i r e s May 2 7 , 1 9 6 7 .

■ a - * # * * * # * * * * * * - *

( T i t l e Omit ted - FILED JUN 7 1963)

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

Now come t h e p l a i n t i f f s , by t h e i r a t t o r n e y s , and

r e s p e c t f u l l y p r a y t h e c o u r t t o i s s u e a t e m p o r a r y r e s t r a i n i n g

o r d e r and a f t e r a p p r o p r i a t e h e a r i n g , a p r e l i m i n a r y i n j u n c

t i o n a g a i n s t t h e d e f e n d a n t s i n a c c o r d a n c e w i t h t h e p r a y e r s

o f Count s I and I I o f t h e v e r i f i e d c o m o l a i n t f i l e d h e r e i n

and i n s u p p o r t o f t h e s e m o t i o n s say as f o l l o w s :

1 . A l l o f t h e a l l e g a t i o n s o f Counts I and I I o f t h e

v e r i f i e d c o m p l a i n t a r e r e a l l e g e d h e r e i n as t h ou gh f u l l y se t

f o r t h , and t h e r e a r e a t t a c h e d h e r e t o , marked, r e s p e c t i v e l y ,

E x h i b i t s A t h r o u g h E, a f f i d a v i t s o f s e v e r a l o f t h e p l a i n t i f f s

i n s u p p o r t o f t h e a l l e g a t i o n s c o n t a i n e d i n t h e v e r i f i e d com

p l a i n t , i n a c c o r d a n c e w i t h t h e r u l e s and p r a c t i c e o f t h i s

Court .

2 . The c o n d u c t o f t h e d e f e n d a n t s c o m p l a i n e d o f i n

23 .

t h i s c a s e i s c o n t i n u o u s , v i o l e n t , t h r e a t e n i n g , i n t i m i d a t i n g

24 .

(R31) h a r a s s i n g and t h e d e f e n d a n t s have used and a r e u s i n g e f f e c

t i v e l y t h e f o r c e and power o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i i n

v i o l a t i o n o f t he c o n s t i t u t i o n o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s , and more

p a r t i c u l a r l y , t h e F o u r t e e n t h Amendment t h e r e t o , t o v i o l a t e ,

impair and f r u s t r a t e t h e e x e r c i s e o f p r e s e n t and immediate

r i g h t s g u a r a n t e e d t o t h e p l a i n t i f f s by t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n o f t he

Uni ted S t a t e s .

3 . Not o n l y a r e t h e d e f e n d a n t s making use o f t h e

p o l i c e power in t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i f o r t h i s i l l e g a l

p u r p o s e , but on June 6 , 1 9 63 , w i t h o u t n o t i c e o r o p p o r t u n i t y

t o be h e a r d , t h e C ha nc er y Court o f Hinds C o u nt y , l i k e w i s e

a c t i n g p ur su an t t o or i n c o n d o n a t i o n o f t h e p o l i c y o f misuse

o f s t a t e power c o m p l a i n e d o f h e r e i n , e n t e r e d a b ro a d and

sweeping t e m p o r a r y i n j u n c t i o n a g a i n s t some o f t h e p l a i n t i f f s

and o t h e r p e r s o n s , seme o f whom a t l e a s t , have no c o n n e c t i o n ,

d i r e c t o r i n d i r e c t w i t h t h e p l a i n t i f f s . That i n j u n c t i o n p r o

h i b i t s c e r t a i n named p e r s o n s and a group v a g u e l y d e s c r i b e d

f rom an i n d e f i n i t e , v a g u e , c o u r s e o f c o n d u c t , g e n e r a l l y

c h a r a c t e r i z e d by t h e d e f e n d a n t s a s i l l e g a l and u n l a w f u l . A

copy o f t h a t i n j u n c t i o n i s a t t a c h e d h e r e t o marked E x h i b i t F .

4 . In t r u t h and i n f a c t , i t i s t h e i n t e n t i o n o f the

d e f e n d a n t s and t h e Chance ry Court o f Hinds County t o f u r t h e r

i n t i m i d a t e and h a r a s s p l a i n t i f f s and t o p r e v e n t them from

e x e r c i s i n g r i g h t s g u a r a n t e e d by t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n and laws o f

the U n i t e d S t a t e s by u s e o f t h e ex p a r t e i n j u n c t i v e d e v i c e .

5 . With t h e c o u r t s o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s s i p p i

i g n o r i n g t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n and laws o f t h e U ni t e d S t a t e s i n t h e

p r o s e c u t i o n s o f p l a i n t i f f s , and t h e members o f t h e c l a s s which

they r e p r e s e n t , and t h e Chancery Court o f Hinds County a b u s i n g

the e q u i t y p r o c e s s o f t h e c o u r t s o f M i s s i s s i p p i , i t i s a p p a r e n t

that t h e r e i s no remedy a v a i l a b l e t o p l a i n t i f f s , and t h e c l a s s

they r e p r e s e n t , i n t h e c o u r t s o f M i s s i s s i p p i .

6 . Any d e l a y i n r e s t r a i n i n g t h e c o n d u c t o f t h e d e f e n d

ants c o m p l a i n e d o f w i l l i t s e l f amount t o a d e n i a l t o p l a i n t i f f s

o f r i g h t s p r o t e c t e d by t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n and Laws o f t h e U n i t e d

S t a t e s , as a p p e a r s f r om t h e f a c t t h a t t h e B i l l o f I n j u n c t i o n

f i l e d by d e f e n d a n t s i s not r e t u r n a b l e i n t h e C h an ce ry Court

o f Hinds C ount y , M i s s i s s i p p i , u n t i l t h e Sept ember Term, 1 9 63 ,

which d o e s not b e g i n u n t i l t h e s e c o n d Monday i n S e p t e m b e r ,

1963 .

7. No i n j u r y t o t h e p u b l i c o r t h e d e f e n d a n t s w i l l be

s u s t a i n e d by t h e i s s u a n c e o f t h e t e m p o r a r y r e s t r a i n i n g o r d e r

or p r e l i m i n a r y i n j u n c t i o n as p r a y e d f o r h e r e i n . I n d e e d t he

i n t e r e s t o f t h e p u b l i c w i l l be f o s t e r e d and f u r t h e r e d as a

breakdown i n p r o t e c t i o n o f c o n s t i t u t i o n a l r i g h t s a v a i l a b l e t o

a l l w i l l be a v e r t e d . The d e f e n d a n t s w i l l m e r e l y be r e q u i r e d

to comply w i t h t h e d u t y incumbent upon a l l s t a t e o f f i c e r s , a

duty t h e y have sworn t o be bound b y - - n a m e l y t o e x e r c i s e s t a t e

26

power i n c o n f o r m i t y w i t h t h e d i c t a t e s o f t h e F o u r t e e n t h

Amendment t o t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s C o n s t i t u t i o n .

WHEREFORE p l a i n t i f f s r e s p e c t f u l l y p ra y t h i s Court f o r

a t emp ora ry r e s t r a i n i n g o r d e r and p r e l i m i n a r y i n j u n c t i o n in

a c c o r d a n c e w i t h t h e r u l e s and s t a t u t e s p r o v i d e d and i n a c c o r d

ance w i t h t h e p r a y e r s o f t h e c o m p l a i n t h e r e i n .

R e s p e c t f u l l y s u b m i t t e d ,

/ s / C a r s i e A . H a l l ___________

JACK H. YOUNG

CARSIE A. HALL

l l 5 j N. F a r i s h S t r e e t

J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i

ROBERT L. CARTER

BARBARA A. MORRIS

20 West 4 0t h S t r e e t

New York 1 8 , New York

JACK GREENBERG

LEROY D. CLARK

DERRICK A . BELL

10 Columbus C i r c l e

New York 1 9 , New York

WILLIAM R . MING, J R .

123 West Madison S t r e e t

Chi ca go 2 , I l l i n o i s

FRANK D. REEVES

508 F i f t h S t r e e t , N.W.

W a s h i n g t o n 1 , D. C.

R. JESS BROWN

125^ Nort h F a r i s h S t r e e t

J a c k s o n , 1 , M i s s i s s i p p i

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

(R 3 3)

(R 3 4)

2 7 .

VERIFICATION

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI )

)

COUNTY OF HINDS )

Medgar E v e r s , b e i n g f i r s t d u l y sworn, says t h a t he i s

one o f t h e p l a i n t i f f s i n t h i s c a u s e , and t h a t he has rea d t he

above and f o r e g o i n g m o t i o n , and t h a t a l l o f t h e a l l e g a t i o n s

c o n t a i n e d t h e r e i n a r e t r u e t o t he b e s t o f h i s i n f o r m a t i o n ,

knowledge and b e l i e f .

BY_____ / s / Medgar W. E v e r s _______

Sworn t o and s u b s c r i b e d t o b e f o r e

me t h i s 6t h day o f J u n e , 1 9 63 .

/ s / H. C. Latham______ ______

Not ary P u b l i c

My c o mm is s i on e x p i r e s May 27 , 1 9 6 7 .

NOTICE OF MOTION

PLEASE TAKE NOTICE t ha t t h e u n d e r s i g n e d a t t o r n e y s f o r

p l a i n t i f f s w i l l b r i n g on t h e a t t a c h e d m o t i o n f o r p r e l i m i n a r y

i n j u n c t i o n b e f o r e t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s D i s t r i c t Court i n t h e

Southern D i s t r i c t o f M i s s i s s i p p i , J a c k s o n D i v i s i o n on t h e

7th day o f J un e 1 9 6 3 . a t 2 : P.M. o r as soon t h e r e a f t e r as

c o u n s e l can be h e a r d .

R e s p e c t f u l l y s u b m i t t e d

/ s / C a r s i e A. H a l l

JACK YOUNG

CARSIE A. HALL

115^ N. F a r i s h S t r e e t

J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i

R. JESS BROWN

1252 N. F a r i s h S t r e e t

J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i

ROBERT CARTER

BARBARA MORRIS

20 West 4 0t h S t r e e t

New Y o r k , New York

JACK GREENBERG

LEROY D. CLARK

10 Columbus C i r c l e

New Y o r k , New York

WILLIAM R . MING J r .

123 West Madison S t r e e t

C h i c a g o , I l l i n o i s

FRANK D. REEVES

508 F i f t h S t r e e t , N.W.

W a s h i n g t o n , D. C.

A t t o r n e y s f o r P l a i n t i f f s

* * * * * * * * * * * *

EXHIBIT A

AFFIDAVIT OF WILLIE B. LUDDEN

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI )

HINDS COUNTY

CITY OF JACKSON

) SS :

)

B e f o r e me p e r s o n a l l y a p p e a r e d W i l l i e B. Ludden who

a f t e r f i r s t b e i n g d u l y sworn d e p o s e s and says t h a t :

1 . He i s a Negro c i t i z e n o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s p e r

manent ly r e s i d i n g a t 859^ Hunter S t r e e t , A t l a n t a , G e o r g i a

(N.W.) .

2 . He i s employ ed as a Y out h F i e l d S e c r e t a r y by th(

N a t i o na l A s s o c i a t i o n f o r t h e Advancement o f C o l o r e d P e o p l e

2 9 .

3 . On Wednesday , May 2 9 , 1 9 63 , he and f i v e o t h e r

p e r so ns were w a l k i n g s i n g l e f i l e , f o u r y a r d s a p a r t on C a p i t o l

S t r e e t i n J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i i n f r o n t o f t h e Woo lwor th

Department S t o r e . The group was c a r r y i n g p l a c a r d s which r ea d

” We d o n ’ t buy on C a p i t o l S t r e e t - NAACP . ” The group o f s i x

p e r s o n s i n no way o b s t r u c t e d t he s t r e e t and were w a l k i n g in

an o r d e r l y manner near t h e c u r b .

4 . About f o u r mi nut es a f t e r t he group began t o p i c k e t ,

20 J a c k s o n p o l i c e m e n i n u n i f o r m came up t o t h e group and put

them under a r r e s t and c h a r g e d them w i t h o b s t r u c t i n g t r a f f i c .

To o b t a i n h i s r e l e a s e d e p o n e n t , and each o f t h e o t h e r s , was

o b l i g e d t o make a c a sh bond i n t h e amount o f $ 1 0 0 . 0 0 . That

charge i s p r e s e n t l y p e nd i n g i n t he C i t y Court o f J a c k s o n .

5 . On F r i d a y , May 3 1 , 1 963 , d eponen t l e f t a mass

meeting at F a r i s h S t r e e t B a p t i s t Church i n J a c k s o n at a p p r o x i

mately 4 : 3 0 P .M. and p r o c e e d e d w i t h a group o f o t h e r p e r s o n s

down F a r i s h S t r e e t . The g r o u p , which i n c l u d e d a bo ut 350 p e r

so ns , was ma rc hi ng two a b r e a s t , w i t h each rank a p p r o x i m a t e l y

f i v e y a r d s a p a r t , i n an o r d e r l y p e a c e f u l f a s h i o n , l e a v i n g

I

room f o r o t h e r p e r s o n s t o use t h e p u b l i c way which t h e group

was t r a v e r s i n g . Each member o f t h e group c a r r i e d an Amer i can

f l a g and a s i g n w h i c h s t a t e d " L e t ’ s wi pe out d i s c r i m i n a t i o n

in J a c k s o n " o r " Fre ed om and j u s t i c e f o r a l l " o r " Freedom i n

J a c k s o n " o r s i m i l a r s l o g a n s . The s o l e p u r p o s e o f deponen t

and t he o t h e r members o f t h e group was t o v o i c e p u b l i c l y

(R17) t h e i r p r o t e s t a g a i n s t t h e use o f t h e power o f t h e S t a t e o f

M i s s i s s i p p i t o e s t a b l i s h and m ai n t a i n r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n and

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n i n p l a c e s o f p u b l i c a c c o m mo da t i on and i n t h e

use o f p u b l i c f a c i l i t i e s i n J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i . B e f o r e the

group had t r a v e r s e d one c i t y b l o c k f r o m t h e c h u r c h , d eponen t

who was a t t h e head o f t h e group was c o n f r o n t e d by more than

100 J a c k s o n , c o u n t y and s t a t e p o l i c e o f f i c e r s in u n i f o r m .

One o f t h o s e p o l i c e o f f i c e r s , whose name i s not known t o

d e po ne n t , i n q u i r e d o f d e po ne n t wh e t h e r t h e group had a pe rm it

to p a r a d e . Deponent i n f o r m e d him t h a t an e f f o r t t o s e c u r e

such a p e r m i t had not b e e n a n s w e r e d . The J a c k s o n p o l i c e

° f f ^ c e r s d i r e c t e d d e po n e n t and o t h e r s i n t h e group t o r e t u r n

in t he d i r e c t i o n f ro m wh ich t h e y had come. Deponent i n f o r m e d

the p o l i c e o f f i c e r s t h a t i t was h i s i n t e n t i o n t o p r o c e e d in

the d i r e c t i o n he was headed and deponen t resumed w a l k i n g down

the s t r e e t . The J a c k s o n p o l i c e o f f i c e r s i n t h e f i r s t rank o f

p o l i c e o f f i c e r s who had c o n f r o n t e d d e p o n e n t s e p a r a t e d t o

permit d e po ne n t t o p a s s t h r o u g h t h e i r l i n e s . When d e po ne n t

had done s o , he was s u r r o u n d e d by J a c k s o n p o l i c e o f f i c e r s ,

some o f whom, whose names a r e not known t o d e p o n e n t , b e a t

deponent a b o u t t h e arms and s h o u l d e r s w i t h c l u b s and f i s t s

and a t t e m p t e d t o r e s t f r om h i s hands t h e Ame r i ca n f l a g w h ic h

deponent c a r r i e d . One p o l i c e o f f i c e r , whose name i s not

3 0 .

31 .

(R18)

known to d e p o n e n t , put h i s n i g h t s t i c k a c r o s s d e p o n e n t ’ s

neck and p u l l e d d epo ne nt t o t h e g r o u n d . Two o t h e r o f f i c e r s ,

n e i t h e r o f whose names a r e known t o d e p o n e n t , k i c k e d d epo ne nt

and h i t him a bout t h e arms , l e g s and stomach w i t h f i s t s and

c l u b s .

6 . A f t e r h i s a r r e s t and w h i l e i n c a r c e r a t e d , d e po ne n t

was r e f u s e d a c c e s s t o a d o c t o r when he r e q u e s t e d i t . Deponent

was o b l i g e d t o make bond o f $ 1 0 0 . 0 0 t o o b t a i n h i s r e l e a s e . On

the same day d epo ne nt was examined by Dr. A. B. B r i t t o n and

found t o have numerous b r u i s e s a bout t h e b o d y .

7 . On t h e o c c a s i o n o f b o t h a r r e s t s , on May 2 8 , 1 963 ,

and May 3 1 , 1 9 63 , t h e d e po n e n t and h i s group were a t t e m p t i n g

o n l y t o p r o t e s t r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n i n t h e C i t y o f J a c k s o n ,

M i s s i s s i p p i , and were a t t e m p t i n g t o a d d r e s s t h e p u b l i c and

p e t i t i o n t h e c i t y government i n p e a c e f u l and o r d e r l y f a s h i o n

f o r r e d r e s s o f t h e i r g r i e v a n c e s and were p r e v e n t e d f r om d o i n g

so by t h e i r a r r e s t s by p o l i c e o f f i c e r s o f t h e C i t y o f J a c k s o n ,

M i s s i s s i p p i as d e s c r i b e d a b o v e .

8 . Deponent d e s i r e s t o engage i n p e a c e f u l and o r d e r l y

d e m o n s t r a t i o n s i n p r o t e s t a g a i n s t r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n i n t h e

future.

SIGNED ; / s / W i l l i e B 0 Ludden_______

Sworn t o and s u b s c r i b e d t o b e f o r e

me t h i s 6 t h day- o f June 1 9 6 3 .

(R19)

/ s / H. C. Latham____

No ta ry P u b l i c

My commi ss i on e x p i r e s May 27, 1 9 6 7 .

* * * * * * * * * * * *

EXHIBIT B

AFFIDAVIT OF REV. RALPH EDWIN KING

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI )

HINDS COUNTY ) S S :

CITY OF JACKSON )

B e f o r e me p e r s o n a l l y a p p e a r e d R ever end R al ph Edwin

King who a f t e r f i r s t b e i n g d u l y sworn d e p o s e s and says t h a t :

1 . He i s a w h i t e c i t i z e n o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s , and

i s t he C h a p l a i n and permanent r e s i d e n t a t T o u g a l o o C o l l e g e ,

T o u g a l o o , M i s s i s s i p p i .

2 . On T h u r s d a y , May 3 0 , 1 9 63 , at a p p r o x i m a t e l y 4 : 1 5

P.M. d epo nen t and 13 o t h e r p e r s o n s , b o t h Negro and w h i t e , and

i n c l u d i n g b o t h r e s i d e n t s and c i t i z e n s o f t h e S t a t e o f M i s s i s

s i p p i , and r e s i d e n t s and c i t i z e n s o f o t h e r s t a t e s i n t h e

Uni ted S t a t e s , a s s e m b l e d i n t h e F e d e r a l P o s t O f f i c e B u i l d i n g

in J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i f o r t h e p u r p o s e o f c o n d u c t i n g a p r a y e r

s e r v i c e on t h e s t e p s o f t h a t b u i l d i n g t o p r a y f o r the end o f

r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n i n J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i and t h e c e s s a t i o n

o f p o l i c e b r u t a l i t y at L a n i e r High S c h o o l i n t h e same c i t y .

3 . When t h e group had a s s e m b l e d d e p o n e n t and t he

o the r members o f t h e group s t e p p e d t h r o u g h t h e d o o r o f t h e

b u i l d i n g and wer e c o n f r o n t e d by a crowd o f s e v e r a l t h o u s a n d

32 .

33 .

pe rso ns on and around t h e s t e p s o f t h e b u i l d i n g . A l a r g e

number o f o t h e r p e r s o n s had s i m i l a r l y g a t h e r e d i n s i d e t he

b u i l d i n g and b e h i n d t h e d eponent and h i s a s s o c i a t e s .

4 . When t h e de po ne nt and o t h e r members o f t h e group

stopped on t h e p l a z a o f t h e b u i l d i n g and began t o p r a y f rom

10 t o 15 u n i f o r m e d J a c k s o n p o l i c e o f f i c e r s demanded t h a t the

group l e a v e t h e a r e a . When t h e group d i d not do so and c o n

t i n ue d p r a y i n g t h e s e p o l i c e o f f i c e r s a r r e s t e d a l l o f t h e mem

bers o f t h e g r o u p .

5 . Deponent and t h e o t h e r members o f t h e group were

charged w i t h b r e a c h o f t h e p e a c e and w i t h o b s t r u c t i n g t h e

e n t ra nc e t o a p u b l i c b u i l d i n g . Whi l e d e po ne n t was p r e s e n t t h e

(R20) p o l i c e o f f i c e r s t o o k no a c t i o n w i t h r e s p e c t t o t h e crowd

which had g a t h e r e d .

6 . The s o l e i n t e n t i o n o f d e p o n e n t and t h e group was

t o e x e r c i s e t h e i r r i g h t s o f r e l i g i o u s w o r s h i p and f r e e sp e ec h

g uarant eed by t h e F o u r t e e n t h Amendment t o t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n o f

the U n i t e d S t a t e s and t h e s e r i g h t s wer e e f f e c t i v e l y d e s t r o y e d

by t h e i r a r r e s t s on May 28 , 1 9 6 3 .

7 . In o r d e r t o o b t a i n h i s r e l e a s e d ep one nt and each

of the o t h e r members o f t h e group was o b l i g e d t o p o s t a cash

bond o f $ 5 0 0 . 0 0 e a c h . Only t h r e e o f t h e group we r e r e l e a s e d

on t he day o f t h e i r a r r e s t . The r e m a i n d e r were o b l i g e d t o

remain i n c u s t o d y u n t i l t h e next d a y . On June 5, 1 9 6 3 ,

3 4 .

(R21)

deponent and each o f t h e o t h e r members o f t h e group was c o n

v i c t e d i n t h e C i t y Court o f J a c k s o n and f i n e d $ 2 0 0 . 0 0 and

s ent enc ed t o f o u r months i n t h e County J a i l . In o r d e r t o

remain a t l i b e r t y p e n d i n g a p p e a l , d e po n e n t and each o f t h e

o ther members o f t he group has been o b l i g e d t o p o s t a cash

bond o f $ 5 0 0 . 0 0 . . ;

8 . Deponent d e s i r e s p e a c e f u l l y and p u b l i c l y i n t h e

f u t u r e t o p r a y f o r t h e end o f r a c i a l s e g r e g a t i o n and t h e abuse

o f p o l i c e p r o c e s s e s .

SIGNED: / s / R e v . R al ph Edwin King

Sworn t o and s u b s c r i b e d t o b e f o r e

me t h i s 6t h day o f June 1 9 6 3 .

/ s / H. C. Latham_____________

Not ary P u b l i c

My Commission e x p i r e s May 27 , 1 9 6 7 .

t t - f r * * * * * * * * * *

EXHIBIT C

AFFIDAVIT OF DORIS ALLISON

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI )

HINDS COUNTY ) SS:

CITY OF JACKSON )

B e f o r e me p e r s o n a l l y a p p e a r e d D o r i s A l l i s o n who a f t e r

f i r s t b e i n g d u l y sworn d e p o s e s and says t h a t :

1 . Deponent i s an a d u l t Negro c i t i z e n o f t h e U n i t e d

S t a t es p e r m a n e n t l y r e s i d i n g a t 2927 B ooker W a sh in gt o n S t r e e t ,

J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i .

35.

2 . On May 2 9 , 1 9 63 , at 1 2 : 1 5 P . M . , t h e d e po ne n t and

f i v e o t h e r p e r s o n s a t t e m p t e d t o p i c k e t t h e Woo l wor th s t o r e on

C a p i t o l S t r e e t i n J a c k s o n , M i s s i s s i p p i . The d eponent and t h e

group wa lk ed i n s i n g l e f i l e on t h e s i d e w a l k i n f r o n t o f t h e

Woolworth s t o r e c a r r y i n g s i g n s p r o t e s t i n g a g a i n s t r a c i a l d i s

c r i m i n a t i o n p r a c t i c e d by t h e Woo lwor th s t o r e . The s i g n which

deponent c a r r i e d b o r e t h e l e g e n d , " D o n ’ t Shop On C a p i t o l

S t r e e t . "

3 . At no t i m e d i d deponent and h e r group b l o c k t h e

s idewalk so as t o p r e v e n t i t s normal u s e .

4 . Deponent and her a s s o c i a t e s had been p i c k e t i n g

f o r about two or t h r e e mi nu te s when e i g h t or t e n u n i f o r m e d

p o l i c e o f f i c e r s , i n c l u d i n g C a p t a i n Ray , Deputy C h i e f o f t h e