Morrow v. Dillard Supplemental Brief for Appellants on Rehearing En Banc

Public Court Documents

August 24, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Morrow v. Dillard Supplemental Brief for Appellants on Rehearing En Banc, 1973. 0e3dddcc-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e55d6944-b3f0-46b9-91d2-581335f6474f/morrow-v-dillard-supplemental-brief-for-appellants-on-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

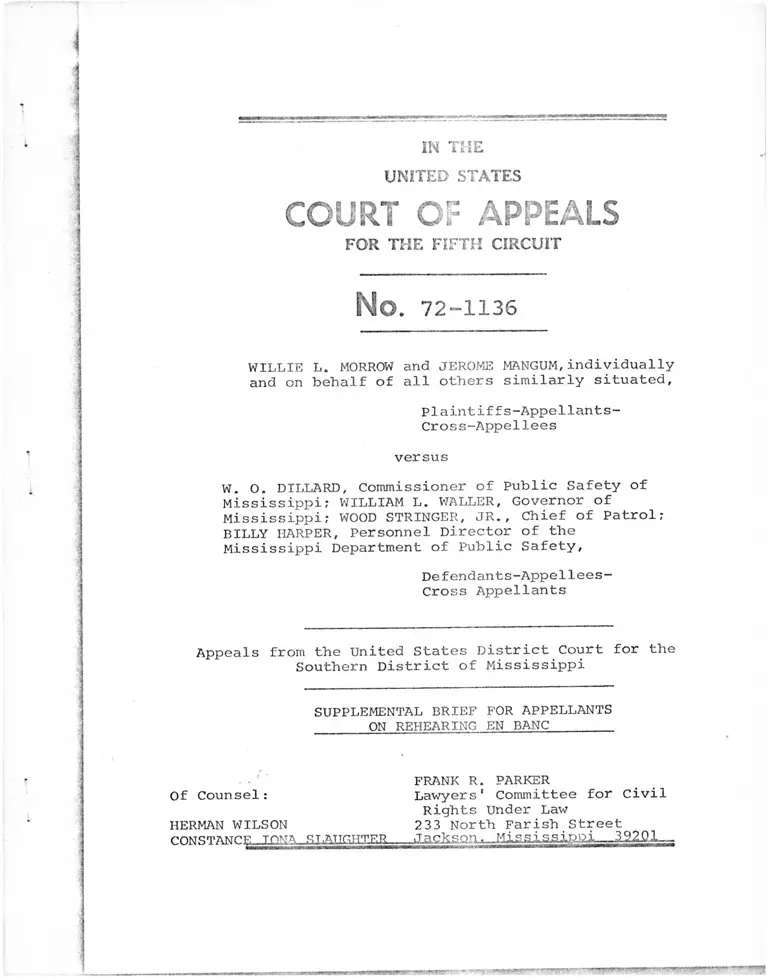

IN THE

UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-1136

WILLIE L. MORROW and JEROME MANGUM,individually

and on behalf of all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-

Cross-Appellees

versus

W. O. DILLARD, Commissioner of Public Safety of

Mississippi; WILLIAM L. WALLER, Governor of

Mississippi; WOOD STRINGER, JR., Chief of Patrol;

BILLY HARPER, Personnel Director of the

Mississippi Department of Public Safety,

Defendants-Appellees-

Cross Appellants

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

ON REHEARING EN BANC_______

Of Counsel:

HERMAN WILSON

CONS T A N C ^ i^^ jS LA IIG m E R

RANK R. PARKER ,awyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

33 North Farish Streetackson. MississiPt ‘

TABLE OF CONTENTS

OPINIONS BELOW

BRIEF STATEMENT OF THE CASE

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN

FAILING TO ORDER AFFIRMATIVE

HIRING RELIEF TO REMEDY THE PRESENT

EFFECTS OF PAST DISCRIMINATION IN

HIRING.

A. The Findings of the District

Court Compel Affirmative

Minority Hiring Goals

B. Affirmative Hiring Relief to

Remedy the Present Effectsof Past Discriminatory Hiring

Practices is Constitutionally

Required.

C. Plaintiffs' Request for

Affirmative Minority Hiring

Goals is Supported by the

Overwhelming Weight of Authority;

Every Court of Appeals Has

Required or Approved Affirmative

Hiring Ratios in Cases of Public

Employment Discrimination

Raising the Issue.

D. Affirmative Minority Hiring Goals Are Feasible and

Constitutional.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO REQUIRE THE DEFENDANTS TO ADHERE

TO STRICT STANDARDS OF TEST VALIDATION.

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO REQUIRE DEFENDANTS TO OFFER

PLAINTIFFS EMPLOYMENT AND TRAINING

WITH BACK PAY.

CONCLUSION

1

2

7

7

7

9

13

16

21

25

29

-l-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE

Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc., 444 F.2d 687

C5th Cir. 1971)..............................

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v. Bridgeport Civil

Service Comm'n, 5 FEP Cases 1344 (2d Cir.

1973), aff'g in relevant part, 354 F. Supp.

778 (D. Conn. 1973) ........................

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 19 71)

(en banc), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950

(1972) ....................................

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972).

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167

(2d Cir. 1972)..............................

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. 0 Neill, 473

F.2d 1029 (3d Cir. 1973) ....................

Contractors Ass'n of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Sec'v of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3d Cir.

1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971). • •

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424,91 S.Ct. 849, 28 L.Ed.2d 158 (1971) . . . .

Harkless v. Sweeny Indep. School Dist., 427

F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1970) ..................

Interstate Circuit Inc^, v. Un ite d St ates,

306 U.S. 208, 59 S.Ct. 467, 83 L.Ed.610

(1939) ....................................

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 453 F.2d

1104 (5th Cir. 1971) ......................

Local 53. Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d

1047 (5th Cir. 1969)......................

Local 189, United Papermakers v. United States,

416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied,

379 U.S. 919 (1970) ........................

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145,

85 S.Ct. 817, 13 L.Ed.2d 709 (1965) ........

17

10,15,16,22,25

10,14,18,20

10 ,14,25

22

10,15,25

20

8

11,29

27

26

10,20

18

10

-li-

Morrow v. Cris ler, 5 EPD 11859 0 , p. 7 72 8 (S.D.

Miss. May 25, 1972) .................... 21

NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703 (M.D. Ala.1972) 6,16 ,29

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Tel. Co., 433

F. 2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970) ...................... 26

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp.

505 (E.D. Va. 1968).............................. 11

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., No. 28959

(5th Cir. Mar. 2, 19 7 3 ) ....................... 26

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097

(5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401 U.S.

948 (1971) .................................... 11

Southern Illinois Builders Ass'n v. Ogilvie,

471 F. 2d 680 (7th Cir. 1972)................... 20

Sparks v. Griffin, 460 F.2d 433 (5th Cir.

1972).......................................... 29

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554

(1971)...........................................11

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346, 90 S.Ct.

532, 24 L. Ed . 2 d 567 (1970)...................... 18

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d

906 (5th Cir. 1973)...............................8

United States v. Haves Internat'l Corp., 415

F. 2d 1038 (5th Cir. 1969)........................H

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied,

406 U.S. 906 (1971) 12 ,25

United States v. Local 46, Lathers, 471 F.2d

408 (2d Cir. 1973)...............................10

United States v. Local 86 Ironworkers, 443

F. 2d 544 (9th Cir. 1971), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 984 (1971), aff'g, 315 F. Supp.

1202 (W.D. Wash. 1970).......................... 10

United States v. Local 212, IBEW, 472 F.2d 634

(6th Cir. 1973).......... 1°

-iii-

_____ _____________________________ ______ _____- , u ■ ,W H ' till ■ I M l I. I ......... W M M

*• '. >.<« . ■ UMHP."1 r*'- '— ■' i -»-V II.

united States v. N. L. Industries, 5 EPD 118529 ,

- reh'g deiTI^d, 5~EP^T862 8 (8th Cir. 19 73) . •

United States v. Texas Education Agency, 459

---F.2d GOO (5th Cir. 19 72) . ................

Vogler v- McCarty, Inc., 451 F.2d 1236 (5th

— Cir. 1971)................................

29

20

10

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

on Employee Selection Procedures

sion1s Guidelines

, 29 CFR 1607 . • 25

Science Research Associates, Inc

Report for the First Civilian

the AGCT, p. 6 (19 6ul • • •

, Technical

Edition~of 24

-iv-

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-1136

WILLIE L. MORROW and JEROME MANGUM,

individually and on behalf of all

others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-

Cross-Appellees,

versus

W.o. DILLARD, Commissioner of Public Safety

of Mississippi; WILLIAM L. WALLER, Governor

of Mississippi; WOOD STRINGER, JR., Chief of

Patrol; BILLY HARPER, Personnel Director of

the Mississippi Department of Public Safety,

Defendants-Appellees-

Cross Appellants.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS ON REHEARING EN BANC

OPINIONS BELOW

The memorandum opinion of the District Court granting

plaintiffs passive relief but denying affirmative hiring relief

is unreported in the official reports but may be found at

4 CCH Employment Practices Decisions [hereinafter EPD]

' 11̂7563, and is reprinted in the Appendix at 432-74. The

Judgment and Order for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief

is found at 4 EPD 1(7541 and in the Appendix at 475-84. A

I prior opinion denying defendants' motion to dismiss is found

at 3 EPD 1(8119. A subsequent order reassessing the amount

of attorney's fees awarded counsel for the plaintiffs may be

found at 4 EPD 1(7584 , and is reprinted in the Appendix ati

4 9 8 -9 9 . A further opinion modifying the judgment and denying

plaintiffs further relief on the testing issue may be found

I

at 5 EPD 1| 8 5 9 0 .

BRIEF STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The two plaintiffs, Willie L. Morrow, a black

veteran with more than three years of police training and ;

experience in the Air Force (App. 48-55), and Jerome Mangum, j:j a black college student at Jackson State College (App. 138),

requested and were denied application forms for employment

with the all-white Mississippi Highway Patrol in June, 1970, j

even though they were objectively qualified for Patrol employ j

ment (App. 350-51) and white applicants at the same time were

given application forms (testimony of Gary E. Brown, App. 199-

201) and were permitted to apply for employment (testimony of

Charles E. Snodgrass, Personnel Director, App. 336-38, 358-64).

Plaintiffs filed this class action on July 30, 1970

on behalf of a class defined by the District Court as including

I ]

-2-

— —

"dii qualified Negroes who have applied or will apply in

the future for employment with the Mississippi Department

of Public Safety and/or the Mississippi Highway Safety

Patrol, all the present Negro employees of the Department

and the Patrol, and all future employees of the Department

and the Patrol" (App. 462), and sought comprehensive

declaratory and injunctive relief against racial discrimina

tion in hiring and employment conditions in the Mississippi

Department of Public Safety and the Mississippi Highway Patrol

pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment, Title VI of the Civil

Rights of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d, and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981

and 1983 (App. 1-13). The District Court on September 29,

1971 held that the statistical evidence showing that since

1938 the Patrol had never hired a black person as a sworn

officer in a state which currently is 36.79 percent black

(1970 Census), and that of the 743 employees of the Mississ

ippi Department of Public Safety, only 17— the cooks and

janitors— were black, showed "a pattern and practice of

racial discrimination in hiring and employment practices"

by the Department of Public Safety and Highway Patrol, and

entered a passive decree on October 18, 1971 prohibiting future

racial discrimination in employment practices. However, the

District Court refused to (1) grant specific relief to plain

tiffs, including offers of employment and back pay; (2) order

affirmative hiring relief to the plaintiff class of qualified

blacks interested in employment with the Patrol; (3) enjoin

categorically the use of pre-employment tests which were

-3-

racially discriminatory and not validated for business

necessity; and (4) award plaintiffs their attorneys fees

at the generally prevailing rate for Federal litigation.

After this appeal was filed, the District Court on the

motion of defendants modified its injunctive order to

relieve the defendants of the duty of compliance in filling

five top positions in the Department, eight Governor's

bodyguard positions, and two secretarial positions (order

included in the Brief for Appellants as Exhibit C in the

Addendum). Defendants also filed a cross-appeal challenging

the findings made and relief ordered by the District Court.

On April 18, 1973, a panel of this Court in a

2—1 decision (Judge Goldberg dissenting) affirmed the injunc

tion issued by the District Court finding principally that

although the District Court articulated no reasons for its

failure to grant affirmative hiring relief for the plaintiff

class, the refusal to order affirmative hiring relief never

theless was within the discretion of the District Judge.

Plaintiffs' petition for rehearing en banc was granted August

6, 1973.

Since the District Court's decree was entered,

relatively little actual integration of the work force of the

Department of Public Safety and Highway Patrol has been

accomplished. As of May 3, 1973, eighteen months after the

decree, only 13 black persons (excluding cooks and janitors)

had been employed by the Department of Public Safety (which

-4-

has more than 700 employees), and only 4 black sworn patrol

men had been hired in the Highway Patrol of the 363 sworn

officers employed.

The current hiring statistics as of May 3, 1973,

contained in plaintiffs' motion to supplement the record filed

May 7, 1973, based on statistics required by the decree to be

kept by defendants, and admitted as accurate by the defendants

in their response to plaintiffs' motion filed May 21, 1973,

show that since the decree the Department has employed (new-

hires) 186 persons, and of these 173 have been white (93.0

percent) and only 13 have been black (7.0 percent), which

includes one black in recruit training who subsequently has been

discharged. Of the 51 Highway Patrolmen hired since the

decree, 47 have been white (92.2 percent), and only 4 have

been black (7.8 percent). Of the 99 support personnel hired

since the decree, 91 have been white (91.9 percent) and only

8 have been black (8.1 percent) (excluding cooks and janitors).

The rate of hiring of blacks as Highway Patrolmen

has steadily decreased since the decree, as shown by the May 3

statistics on graduation and enrollment (April 22, 1973 class)

in the Patrol's recruit training classes:

Date of Recruit

Training Class

June 18, 1972 (graduates)

January 7, 1973 (graduates)

April 22, 1973 (class in

session as of May 3, 19 73)

1/ The 1 black person Tn the recruit training class which

commenced April 22 , 1973 subsequently was d i s c h .

the last completed Patrol recruit training Rnnpllants'Affidavit of Edwin Milford Buckley, attached to Appellant

Reply Brief on petition for rehearing.

Total White Black % Black

31 28 3 9.7%

20 19 1 5.0%

36 35 l V 2.8%

-5

In contrast, in a shorter period of time (February

10 , 1972 to April 27, 1973) the Alabama Department of Public

Safety, placed under a one-for-one alternating white and

black hiring ratio in NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703 (M.D.

Ala. 1972), on appeal No. 72-1796 , has hired four times as

many black employees as Mississippi, including three times as

many black patrolmen, and five times as many black support

personnel in a state with a smaller percentage of blacks in the

total population (26.2 percent black) than Mississippi (36.8

percent black). See Report Concerning Compliance With Order,

NAACP v. Allen, filed April 27, 1973, attached to plaintiffs'

motion to supplement record. A comparision of racial hiring

since the date of the respective decrees is shown in the

following table, with Mississippi figures taken from defendants'

records as of May 3, 1973, and the Alabama figures taken from

the April 27, 1973 compliance report:

NEW HIRING

Mississippi

(From Oct. 18, 1971;

state is 36.8% black)

Alabama

(From Feb. 10 , 19 72; state is 26.2% black)

Total White Black Total White Black

New hires 186 173 13 (7.0%) 96 44 52 (54.2%)

Patrolmen 51 47 4 (7.8%) 25 13 12 (48.0%)

Support 2/ (56.3%)personnel 99 91 8 (8.1%) 71 31 40

Currently in recruit

training as

of May 3 36 35 1 (2.8%)

2/ Includes 1 part-time toxicologist, 1 temporary clerk, and

T clerk hired but not yet working as of May 3, 1973, excludes

cooks and janitors. _c_

Defendants' statistics show that Mississippi s

tokenism and continued discrimination in hiring is not the

result of lack of interest among Mississippi black persons in

joining the Patrol, but rather in substantial part is the

result of racial discrimination in testing. Since the decree,

149 blacks have applied for patrolmen positions and were

considered sufficiently qualified to be notified to appear for

testing, according to defendants' most recent reports. Of

the 108 black applicants who appeared for testing during this

period and took the defendants' Army General Classification

Test, a test instituted since the decree and not yet validated

for successful job performance with the Patrol, only 9 have

passed (pass rate of 8.3 percent for blacks). In contrast,

of the 317 whites who appeared for testing during this period

and took the test, 209 have passed (pass rate of 65.9 percent

for whites).

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING TO

ORDER AFFIRMATIVE HIRING RELIEF TO

REMEDY THE PRESENT EFFECTS OF PAST

DISCRIMINATION IN HIRING.____________

A. The Findings of the District

Court Compel Affirmative

Minority Hiring Goals.______

The District Court found, and the panel unanimously

sustained its findings, that the defendants have engaged in a

firmly entrenched, systematic, and pervasive pattern and

practice of discrimination against blacks in hiring and other

-7-

I

conditions of employment in the Mississippi Department of

| Public Safety and the Mississippi Highway Patrol. This { j

finding is supported by statistical evidence of complete

i

exclusion of blacks from patrolmen and support positions,

except as menial labor, as well as by undisputed evidence of

.■jidentifiable discriminatory practices, including (1) informal

word-of-mouth and "friends and relatives" recruiting and

hiring (App. 454, 457) which perpetuates the all-white nature

of the work force, see United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474

F.2d 906, 925 (5th Cir. 1973); (2) recruiting efforts

predominantly among whites, and the use of recruiting aids

portraying an all-white Patrol (App. 455-56); (3) the use of

qualifying examinations which have not been validated for

successful job performance (App. 453), see Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 91 S.Ct. 849, 28 L.Ed.2d 158 (1971);

and (4) the lack of any written rules or regulations prohibiting

the use of derogatory racial epithets, which have been used by

patrolmen in addressing blacks (App. 456).

Further, the District Court found, and the panel

sustained its findings, that the Department and the Highway

Patrol "have had a reputation throughout the State of Mississippi,

and particularly among the Black communities, as being an all-

white Department and Patrol, which has discouraged Blacks . . .

from applying for membership, particularly as sworn officers

of the Patrol . . . " (App. 457). These findings are under-

lined by the 1970 study made by the International Association

I

-8-

of Chiefs of Police and approved by the Mississippi state

law enforcement planning agency which found: "A synthesis

of the opinion of the Negro community about the Mississippi

Highway Patrol seems to suggest that it, too, represents

in the Negro mind another repressive force of the white

community" (App. 287-88).

The findings of the District Court clearly indicate,

as Judge Goldberg notes in his dissenting opinion, that "the

barriers to black entry into the Highway Patrol that defendants

erected and tolerated have been formidable" (slip opinion at

19). On these facts, the deterrent to substantial numbers of

qualified blacks applying, and being accepted, for employment

with the Department of Public Safety and the Highway Patrol

is so great that the imposition of affirmative minority

hiring goals is compelled if substantial integration is to

be achieved.

B. Affirmative Hiring Relief to Remedythe Present Effects of Past Discrimina

tory Hiring Practices is Constitutionally

Required.________________ ____________

The Constitution not only prohibits states from

discriminating in employment on the basis of race, but also

requires that effective steps must be taken to remedy the

present effects of past discrimination. In the face of

constitutionally prohibited racial discrimination, the Supreme

Court has held that District Courts have "not merely the power

but the duty to render a decree which so far as possible

eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past as well as

-9

bar like discrimination in the future." Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145, 154, 85 S.Ct. 817, 13 L.Ed.2d 709 (1905).

Mindful of this constitutional requirement and

uniformly applying it to cases of employment discrimination,

on the basis of facts far less compelling than are present

here, this Court and seven other courts of appeals, including

the First, Second, Third, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth

Circuits, have both in Title VII and public employment hiring

discrimination cases, required or approved district court decrees

which include affirmative minority hiring goals. Local .53,

Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969);

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972); United

States v. Local 46, Lathers, 471 F.2d 408 (2d Cir. 1973) ,

cert, denied, 41 U.S.L.W. 3645 (U.S. June 11, 1973); Bridge;

port Guardians, Inc, v. Bridgeport Civil Service Common, 5

PEP Cases 1344 (2d Cir. 1973), aff'9 in relevant part, 354

F. Supp. 778 (D. Conn. 1973); Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v.

O.Neill, 473 F.2d 1029 (3rd Cir. 1973); United States v.

Local 212, IBEW, 472 F.2d 634 (6th Cir. 1973); United States

v. Local 169. Carpenters, 457 F.2d 210 (7th Cir. 1972), cert,

denied, 93 S.Ct. 63 (1972); Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d

315, 327 (8th Cir. 1972) (en banc), cert, denied, 406 U.S.

950 (1972); United States v. N. L. Industries, 5 EPD 118529 ,

reh’g denied, 5 EPD 118628 (8th Cir. 1973); United States v.

Local 86 ironworkers, 443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir. 1971), cert,

denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971), aff’9, 315 F. Supp. 1202

(W.D. Wash. 19 70) .

- 10-

------' >. — M B—

Constitutional rights won upon trial are never

fully realized unless adequate relief is prescribed, and a

court of equity has wide-ranging authority, including the

use of mathematical ratios, to decree whatever relief is

necessary to remedy constitutional violations. Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 25, 91 S.Ct.

1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554 (1971). A remedy is not sufficient if

it merely forbids future discrimination. The statutes invoked

here have been held by this Court to provide "a comprehensive

remedy" for relief from employment discrimination, Harkless v.

Sweeny Indep. School Dist., 427 F.2d 319, 324 (5th Cir. 1970)

(42 U.S.C. § 1983), and to contain "general remedial language."

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097, 1101 (5th Cir.

1970) (42 U.S.C. § 1981), cert, denied, 401 U.S. 948 (1971).

Congressional anti-discrimination legislation was "not

intended to freeze an entire generation of Negro[es] . . . into

discriminatory patterns that existed before the act[s]."

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505, 516 (E.D.

Va. 1968), quoted with approval, United States v. Hayes

Intemat11 Corp. , 415 F.2d 1038, 1045 (5th Cir. 1969).

Hence, to the extent possible, the relief granted

in employment discrimination cases must place the victims of

discrimination in the positions they would have occupied but

for the discriminatory practices of the defendants. "When the

current effects of past— and sometimes present— racial discri

mination have come to our attention, this Court has unhesi

tatingly required affirmative remedial relief." United States

-11-

v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418, 455 (5th Cir. 1971),

cert, denied, 406 U.S. 906 (1971).

Because of racial discrimination in hiring, quali

fied blacks have been completely excluded from the work force

of the Mississippi Department of Public Safety and the

Mississippi Highway Patrol, except in the most menial positions.

Since this racial exclusion is directly attributable to the

Constitutional violation found by the District Court to exist,

and unanimously affirmed by the panel, an effective remedy

for this violation must deal directly with the issue of

wholesale exclusion. A swift, effective means, which excludes

the possibility of "covert subversion of the purpose of the

injunction," Vogler, supra, 407 F.2d at 1055, must be devised

affirmatively to include qualified blacks in the defendants'

work force, and they must be affirmatively included in sufficient

numbers to overcome the present effects of the past discrimi

nation, that is, to place the plaintiff class of qualified

blacks in the position they would have attained but for the

violation. "Affirmative action is necessary to remove these

lingering effects." United States v. Hayes Internat'l Corp.,

456 F.2d 112, 117 (5th Cir. 1972). This is not to say that

a permanent system of quota hiring, or the like is required.

Once the Constitutional violation has been remedied, and the

rights of the plaintiff class have been vindicated by the

affirmative employment of blacks in sufficient numbers to

overcome the decades of exclusion, the defendants can be

-12-

relieved of these constraints and blacks and whites can

compete for positions on an equal basis.

The findings of the District Court show a firmly

entrenched and pervasive pattern and practice of racial

exclusion from employment which has existed for decades.

These findings also show that the barriers to black entry

into positions in the Department and Patrol have been

formidable. The most recent statistics show that eighteen

months after the District Court's decree, the barriers have

not been eliminated and blacks continue to be virtually

excluded from these positions. The burden must be placed

on the defendants to recruit qualified blacks and to hire

them in positions in significant numbers as vacancies arise.

C. Plaintiffs' Request for Affirmative

Minority Hiring Goals Is Supported

by the Overwhelming Weight of Authority;

Every Court of Appeals Has Required or

Approved Affirmative Hiring Ratios in Cases

of Public Employment Discrimination

Raising the I s s u e . _________________

Because the Constitution requires affirmative steps

to eradicate the present effects of past discrimination, the

failure of the District Court to provide appropriate

affirmative remedies constitutes an abuse of discretion and

requires modification of the decree. Every court of appeals

faced with the question of ordering affirmative hiring goals

has required or approved their use as a means of remedying

the effects of past discrimination. Four circuits have

-13-

required or upheld their use in public employment diocrimina

t-ion cases, three involving police departments.

In Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972),

involving non-purposeful racial discrimination in recruiting

and hiring of policemen for the Boston Police Department and

other police agencies, the district court held that the

qualifying examinations were discriminatory but declined to

order affirmative hiring relief to correct racial under

representation on the police agencies involved, primarily

because of its definition of the breadth of the aggrieved

class. The First Circuit held that because of the court's

duty to remedy past discrimination, "some form of compensa

tory relief is mandated" (459 F.2d at 736). Affirmative

hiring relief was held to be required: "if relief in the near

future is to be more than token, further provision is

necessary" (id. at 737). The district court was directed to

establish hiring pools, one for whites and one for minority

group members, qualified under non-discriminatory standards

and that applicants be hired from those pools according to a

fixed ratio, one-for-one, one-for-two, or one-for-three.

The Eighth Circuit in Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d

315, 327 (1972) (en banc), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972),

upon a district court finding of racial discrimination in

hiring for the Minneapolis, Minnesota Fire Department,

provided for a one-to-two alternating minority and white

hiring ratio, although it recognized that a one-to-one ratio

had been approved for "areas with a more substantial minority

-14-

population than the Minneapolis area,-' (452 F.2d at 331),

which was only 6.44 percent minority. Recognizing "the

legitimacy of erasing the effects of past racially

discriminatory practices," (452 F.2d at 330) the court held

tli at

"in making meaningful in the immediate

future the constitutional guarantees

against racial discrimination, more than

a token representation should be afforded.* * * Given the past discriminatory hiring

policies of the Minneapolis Fire Department,

which were well known in the minority

community, it is not unreasonable to assume

that minority persons will still be

reluctant to apply for employment, absent

some positive assurance that if qualified

they will in fact be hired on a more than

token basis." 452 F.2d at 331.

Very recently, the Second Circuit in Bridgeport

Guardians, Inc, v. Bridgeport Civil Service Comm'n, 5 FEP

Cases 1344 (1973) (No. 73-1356 , June 28, 1973), holding that

the relief was appropriate to cure past discrimination, sustained

a district court injunction granting relief from non-purpose-

ful racial discrimination in hiring by the Bridgeport,

Connecticut Police Department which required that minorities

be hired to fill (1) half of the current 10 patrolman vacancies,

(2) three-fourths of the next 20 patrolmen vacancies, and

(3) half of all subsequent vacancies until the goal of 50

minority patrolmen— 15 percent of the force— had been reached.

354 F. Supp. 778, 79 8-99 (D. Conn. 1973).

Similarly, in Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. 0 1 Neill,

473 F.2d 1029 (3d Cir. 19 73) (en banc) the Third Circuit

-15-

sustained a preliminary injunction entered by the district

court requiring a one-for-two black-white hiring ratio to

cure racial discrimination in hiring by the Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, Police Department. 348 F. Supp. 1084, 1105

(E.D. Pa. 1972).

D. Affirmative Minority Hiring Goals Are

Feasible and Constitutional._________

Minority hiring goals, whether in the form of one-

for-one hiring, the creation of priority hiring pools, or a

minority preference such as ordered in the Bridgeport

Guardians case, provide the most effective and efficient

means of overcoming past discrimination in hiring practices.

They are the one remedy that will insure results and are not

susceptible of evasion.

On almost identical facts as exist in this case,

Judge Johnson in NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703 (M.D.

Ala. 1972), on appeal No. 72-1796, consistent with his

recognized duty "to correct and eliminate the present effects

of past discrimination" (340 F. Supp. at 705) ordered (1) one-

for-one alternating white and black hiring until the racial

composition of the Alabama State Troopers approximated the

racial composition of the state population (approximately 25

percent), (2) further recruit training classes enjoined until

they were 25 percent black, and (3) one-for-one alternating

white and black hiring of support personnel in the Department

of Public Safety until the racial composition of support person

nel was approximately 25 percent black (340 F. Supp. at 706).

-16-

The order properly places on the defendants, the

perpetrators of unlawful discrimination, the burden of

recruiting qualified personnel: "It shall be the responsibility

of the Department of Public Safety and the Personnel Depart

ment to find and hire the necessary qualified black troopers"

(id.). These minority hiring goals also provide a powerful

incentive to the defendants to abolish their discriminatory

tests and entrance requirements, and to develop reasonable,

job-related, and non-discriminatory entrance requirements and

employment standards. The hiring statistics show that since

the date of the decree, the relief ordered has gone far to

remedy the effects of past discrimination and shows how little

has been accomplished toward that end by the Mississippi decree.

Mississippi's population according to the 1970

Census (which has been questioned for unde renumerating blacks)

was 36.79 percent black, and it is valid to assume, as

courts have done in other cases, that but for discrimination

in employment the racial composition of the Mississippi Highway

Patrol and Department of Public Safety would approximate this

figure. Indeed, the District Court itself, and the cases upon

which it relied, utilized this population criterion in reaching

its finding of a "prima facie case of racial discrimination in

hiring personnel for the Department and the Patrol." Opinion,

Conclusions of Law, par. 4 (App. 464); Bing v. Roadway Express,

Inc. , 444 F. 2d 687 (5th Cir. 1971).

It logically follows that, any relief which falls

short of approximating the racial composition of the Mississippi

population in the Department and Patrol also fails to over

come the prima facie case of racial discrimination found by

the District Judge, and serves to perpetuate the racially

discriminatory hiring practices of the past- Cf. Turner v.

Fouche, 396 U.S. 346, 359, 90 S.Ct. 532, 24 L.Ed.2d 567

(1970). In Carter v. Gallagher, supra, the Eighth Circuit

(en banc) expressly recognized this reasoning when it held that

"some reasonable ratio for hiring minority

persons who can qualify under the revised

qualification standard is in order for a

limited period of time or until there is a fair approximation of minority representation

consistent with the population mix in the area-

452 F.2d at 330 (emphasis added).

In opposing plaintiffs' request for affirmative

hiring relief, the defendants have argued (1) that if required

to follow a hiring ratio, they would be unable to find a

sufficiently large number of qualified blacks interested in

Patrol employment to meet the ratio, and (2) that such a ratio

would constitute an unconstitutional preference for blacks and

discrimination against qualified white applicants.

1. Finding the Qualified Black Applicants

The argument frequently has been made to this Court

by defendants found guilty of racially discriminatory employ

ment practices that they cannot remedy the present results of

their discrimination because of a lack of qualified blacks to

fill positions formerly reserved for whites, and the argument

uniformly has been rejected. United States v. Hayes Internat 1

Corp. , 456 F. 2d 112, 120 (5th Cir. 19 72); Local 189, United

-18-

Pace rmake rs v. United States , 416 F.2d 9 80 , 988 (5th Cir.

1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970). The burden of

proving the unavailability of qualified black applicants

is on the defendants, id., and there is nothing in the Record

which proves this allegation. In face the District Court

specifically found that the defendants had failed to rebut

the statistical prima facie case by showing that the all-

white composition of the Highway Patrol was the result of

factors other than racially discriminatory hiring and

employment practices (App. 465-66).

The supplemented Record shows that since the date

of the decree 149 black applicants met the statutory

requirements for Patrol employment and were invited by the

defendants to take the qualifying examination. The fact

that only 9 passed the examination does not prove that they

were unqualified, but on the contrary clearly establishes

the racially discriminatory impact of the examination itself.

Certainly the defendants should not be permitted to rely on

racially discriminatory hiring criteria as a defense to

enable them to maintain a virtually all-white Patrol.

2. The Constitutionality of a Minority

Hiring Remedy_______ ___________

Experience has shown, and the court decisions

discussed herein have uniformly upheld the notion, that to

eradicate past discrimination in hiring, particularly when

it has been so pervasive as in this case, some temporary

hiring guarantees must be given to qualified minority group

-19-

applicants. When such programs are designed to overcome

past discrimination, they are not preferential to the

disadvantage of whites, but provide only a temporary remedy

toward achieving the goal which would have been obtained

but for the illegal discrimination. In Local 53, Asbestos

Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969), this Court

affirmed a district court decree requiring that four minority

group members be admitted to union membership, that nine others

be referred for work, and that future work referrals alternate

between white and black persons until objective membership

criteria had been developed, and in affirming the injunction

the Court held that such effective remedies for past discrimi

nation do not constitute an unlawful preference in violation

of the rights of whites under Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964. 407 F.2d at 1053. The holding was reaffirmed

in the sequel to that case, Vogler v. McCarty, Inc., 451 F.2d

1236 (5th Cir. 1971).

Such an argument as defendants make has uniformly

been rejected, both in cases challenging the constitutionality

of court-imposed affirmative minority hiring goals in public

employment discrimination cases, see, e.g., Carter v. Gallagher,

supra, and in cases challenging the constitutionality of

affirmative minority hiring plans mandated by Federal

administrative agencies pursuant to Executive Order 11246,

Southern Illinois Builders Ass'n v. Ogilvie, 471 F.2d 680

(7th Cir. 1972); Contractors Ass'n of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

-20-

„.v of Labor. 442 F.2d 159 (3d Clr. 1971), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 854 (19 71).

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING TO

REQUIRE THE DEFENDANTS TO ADHERE TO

STRICT STANDARDS OF TEST VALIDATION.

After the District Court's decree was entered, the

defendants discontinued use of the Otis Quick Scoring Mental

Ability Test and the oral spelling which they had been using

and replaced them with the Army General Classification Test

(AGCT) published by Science Research Associates, Inc. The

evidence produced at the hearing on plaintiffs' subsequent

motion to discontinue use of the AGCT showed that the test

had a dramatic racially discriminatory impact: of the 56 black

applicants who took the test, only 3 passed (pass rate of 5.4

percent), but of the 171 whites who took the test, 105 passed

(pass rate of 61.4 percent). Morrow v. Crisler, 5 EPD 118590 ,

p. 7728 (S.D. Miss. May 25, 1972). Persons who "fail" this

test, or who do not receive "passing scores," are disqualified

from Patrol employment.

Defendants' records of test results from the date

of the decree to May 3, 1973, attached to plaintiffs' motion

to supplement the record filed May 7, 1973, show that during

this 18-month period, of the 108 black applicants who took

the test, only 9 have passed (pass rate of 8.3 percent for

blacks), while of the 317 whites who took the test, 209

have passed (pass rate of 65.9 percent for whites). The

passing rate for whites has thus been more than 8 times the

-21-

passing rate for blacks over this period. Courts in other

public employment cases have enjoined the use of written

qualifying examinations on the basis of racial disparities

far less striking than these Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v.

Bridgeport Civil Service Comm'n, 354 F. Supp. 770, 784 (D.

Conn. 19 73) (passing rate for whites 3-1/2 times rate for

minorities), aff'd in relevant part, 5 FEP Cases 1344 (2d

Cir. 1973); Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167,

1170 (2d Cir. 1972) (passing rate for whites 1-1/2 and 2

times the rate for minorities).

There is no evidence in the Record indicating that

the AGCT has been properly validated to show a high

correlation between test scores and successful job performance

on the Patrol. At the hearing on plaintiffs' motion for

interlocutory relief pending appeal the Department of Public

Safety's Personnel Director testified that he had no evidence

that the test had been validated for successful job performance

with the Patrol (May 19, 1972 Hearing Transcript, pp. 17-18,

23, 35, Supp. R.). After the May 19, 1972 hearing, at which

the defendants presented no proof of validation in the face

of evidence showing a severe racially discriminatory impact,

the classification and test supervisor of the Mississippi

Classification Commission filed with the District Court an

affidavit, completely depriving plaintiffs of the opportunity

of cross-examination, indicating that studies in other parts

of the country showed a high correlation between test scores

»•

-22-

-----------~—

on the AGCT and grades in recruit training, but omitting

reference to actual job performance, and that the same

test was given recruits for the North Carolina Highway

Patrol, but without reference to whether that agency's

hiring practices are discriminatory. A subsequent

affidavit (filed after the District Court's decision) by

Philip Ash, a noted authority on the discriminatory

impact of testing, rebuts the defendants' affidavit and shows

that the use of the AGCT by the defendants is racially

discriminatory and indefensible according to professionally

acceptable standards (Supp. R.) .

While refering to the defendants' affidavit, the

District Court in its decision on plaintiffs' motion did not

hold that the AGCT would serve to eliminate the discriminatory

hiring practices of defendants, but rather held only that it

lacked the power to enforce its own decree while this case

was on appeal to this Court:

"Under the circumstances of this case, this Court is of the opinion that it cannot and

should not exercise any jurisdiction pursuant

to Rule 62(c), F.R.C.P., or under its general

equity powers to completely reopen this case

while on appeal to consider whether the test

administered by the Mississippi Classification Commission was racially discriminatory or

administered in a racially discriminatory manner."5 EPD 1(8590 , p. 7729.

The Army General Classification Test is a psychological

test administered to Army recruits during World War II. As

described by its publisher,

-23-

test r a t h e ^ Gsigned as. a classification

tests servo to di?tinSui-b"h ^eSt* Screening ,n,i , ° distinguish between acceptableand unaceeptabie applicants for a given job

is « l a n? r ™ lmplies' 3 edification ?es?^ * tof measure the different levels ofability, for the purpose of assignment amona those previously select-^ « amon9Aqqnmnfoe T Y faexected. Science Research ates, fno. , Technical Report for t-ho

Trff^ Cxvilaan Edition of the' AGCT. n. fi--

TiS,,l,, ‘«»wn5a-E5-a»-5oSrFaroiai argument) .

Thus, the use to which defendants are putting this test is

wholly inconsistent with the function for which it was intended

by its publisher.

The AGCT consists of three parts— vocabulary,

arithmetic, and block counting. Its publisher admits that

studies conducted on test performance for whites, blacks,

Mexican-Americans, and Indians shows that test scores are

lower for minority groups, and therefore that the test is

culturally and racially biased:

n?i?c\thS AGCT ^ t i t a t i v e and verbal ?vaLtS haYe ltems that are informational in type, and since speed is a factor, it may

be somewhat- ^hat Scores for these items would

g?oups?"haitd?ePr29?d f°r cultu«lW-deprived

The test publisher also cites studies of the St.

Louis Police Department (not indicating whether any blacks

were tested) showing that although scores on the AGCT correlated

highly with "academic scores" in the "police officer training

program," there was a low correlation between test scores and

actual job performance: "The correlations with these service

ratings [used as the measure of job performance) were low

for . . . the AGCT , . ... Ifl. at 21> 22_

-24-

The Supreme Court (Griggs v. Duke Power Co. supra)

and the courts of appeals frequently have found racially

discriminatory and unvalidated qualifying examinations to be

a prime source of racial discrimination in hiring, particularly

in hiring procedures for police departments. Castro v. Beecher,

supra; Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v. Bridgeport Civil Service

Comm'n , supra; Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. 0'Neill, supra.

The Supreme Court has approved, Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

supra, 401 U.S. at 433-34, and this Court has adopted the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's Guidelines on

Employee Selection Procedures, 29 CFR 1607, as "the safest

validation method," United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

supra, 451 F.2d at 456, for insuring that employment tests are

not racially discriminatory and that they are properly validated

to show a high correlation between test scores and successful

job performance. The injunction issued by the District Court

therefore should be modified to prohibit the defendants from

using any employment tests as a condition for employment with

the Department of Public Safety and Highway Patrol which

have not been properly validated for a high correlation of job

relatedness according to the EEOC Guidelines.

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING TO

REQUIRE DEFENDANTS TO OFFER PLAINTIFFS

EMPLOYMENT AND TRAINING WITH BACK PAY.

Since the individual named plaintiffs were refused

applications for employment at a time when, according to

-25-

that the plaintiffs were refused application forms (testimony

of Charles Snodgrass, App. 336-38, 358-64; Opinion, Conclusions

of Law, par. 3, App. 463). Peden subsequently was enrolled

in the September, 1970, all-white Patrol recruit training

class (App. 448). Another white Mississippian, Gary E. Brown,

was able to obtain an application form in the Personnel Office

at this time (App. 199-201), and a white newspaper reporter

was told by an officer in the Public Relations Bureau that

he could go to Patrol headquarters and obtain an application

(App. 211-23). These facts are uncontradicted in the Record.

Further, this employment embargo was supposed to

have lasted from late February to July, and the exhibits

show six application forms from white applicants bearing

dates during this period (App. 500-505). If those applicants

did not receive or submit their application forms on the

dates placed on their forms, the burden was on the defendants

to produce those applicants, who were the employees of the

defendants, to rebut the presumption that they had been given

preferred treatment during this period. Interstate Circuit,

Inc, v. United States, 306 U.S. 208, 59 S.Ct. 467, 83 L.Ed.

610 (1939).

After the plaintiffs finally obtained application

forms, in June, 1971, and applied for the next recruit

training class, both of them continued to be excluded on

discriminatory grounds. Plaintiff Willie L. Morrow, who had

more than three years police training and experience in the

-27-

tOL

Air Force, passed the AGCT test was rejected because he was

under the statutory minimum weight restriction of 165 lbs.

(May 19 , 19 72 Hearing Tr. , p. 39, Supp. R. ) , although the

District Court had found in its opinion that prior to the

filing of this suit "members of the Patrol [white] have been

permitted to apply for patrol training even though they did

not meet the statutory weight . . . requirements at the time

of their application" (Opinion, Findings of Fact, par. 18,

App. 452).

Plaintiff Jerome Mangum, a Jackson State College

student at the time of his application, was rejected for

receiving a failing grade on the AGCT (May 19, 1972 Hearing

Tr., p. 17, Supp. R.) which whites applying prior to the

decree had not been required to take. All of the 53 black

applicants recorded as "failed" had a high school diploma or

its equivalent, 10 had B .A. or B.S. degrees according to

their application forms, and an additional 22 had one or more

years of college training (id., Pis. Ex. P-1, Ex. B). At

the trial of this action, the defendant Personnel Director had

admitted that from their testimony and applications both of

the named plaintiffs were objectively qualified for Patrol

employment (App. 350-51).

On these facts, this Court should hold that the

finding of the District Court that the plaintiffs were

refused employment with the Highway Patrol for non-racial

reasons is clearly erroneous, and that the plaintiffs are

-28-

qualified for Patrol employment by objective and non-

discriminatory standards, and direct the District Court to

the defendants to extend offers of employment and

training to the plaintiffs, and grant them the back pay

which they would have earned had they been accepted for

and enrolled in the September, 1970 recruit training class

and subsequently appointed to positions as patrolmen,

diminished by interim earnings. Sparks v. Griffin, 460

F"2d 433 (5th Cir. 1972); United States v. Texas Education

A^enc^, 459 F.2d 600, 609 (5th Cir. 1972); Harkless v. Sweeney

indep. School Dist. , 427 F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1970), cert,

denied, 400 U.S. 991 (1971).

CONCLUSION

For the above-stated reasons, and on the basis of

the authorities cited, this Court should order that the District

Court modify its decree in accordance with the relief requested

by plaintiffs, and fully stated in the conclusion of the Brief

for Appellants. In order to overcome the present effects of

past discrimination in hiring, this Court should order the

District Court to modify its decree in accordance with Judge

Johnson's order in NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703 (M.D. Ala.

1972), except that the goal should be a Department and Patrol

that is approximately 37 percent black, and recruit training

classes should be 50 percent black to enable the defendants

to hire new patrolmen on a one-to-one alternating white and

/

l

-29-

black basis until the hiring goal has been reached.

Respectfully submitted,

FRANK R. PARKER " ~

Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

233 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

Of Counsel:

Herman Wilson, Esquire

Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

233 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

Constance Iona Slaughter, Esquire Post Office Box 334

Forest, Mississippi 39074

-30-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have this day mailed, postage

prepaid, a copy of the foregoing Supplemental Brief for

Appellants on Rehearing En Banc to the following counsel

William A. Allain, Esquire P. 0. Box 220

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

Charles A. Marx, Esquire P. 0. Box 958

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

Heber A. Ladner, Jr. , Esquire P. 0. Box 220

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

William B. Fenton, Esquire Civil Rights Division

United States Department of Justice Washington, D. C. 20530

This day of August, 1973.

Frank r . Par k er —

Printed copies mailed this

28th day of August, 1973