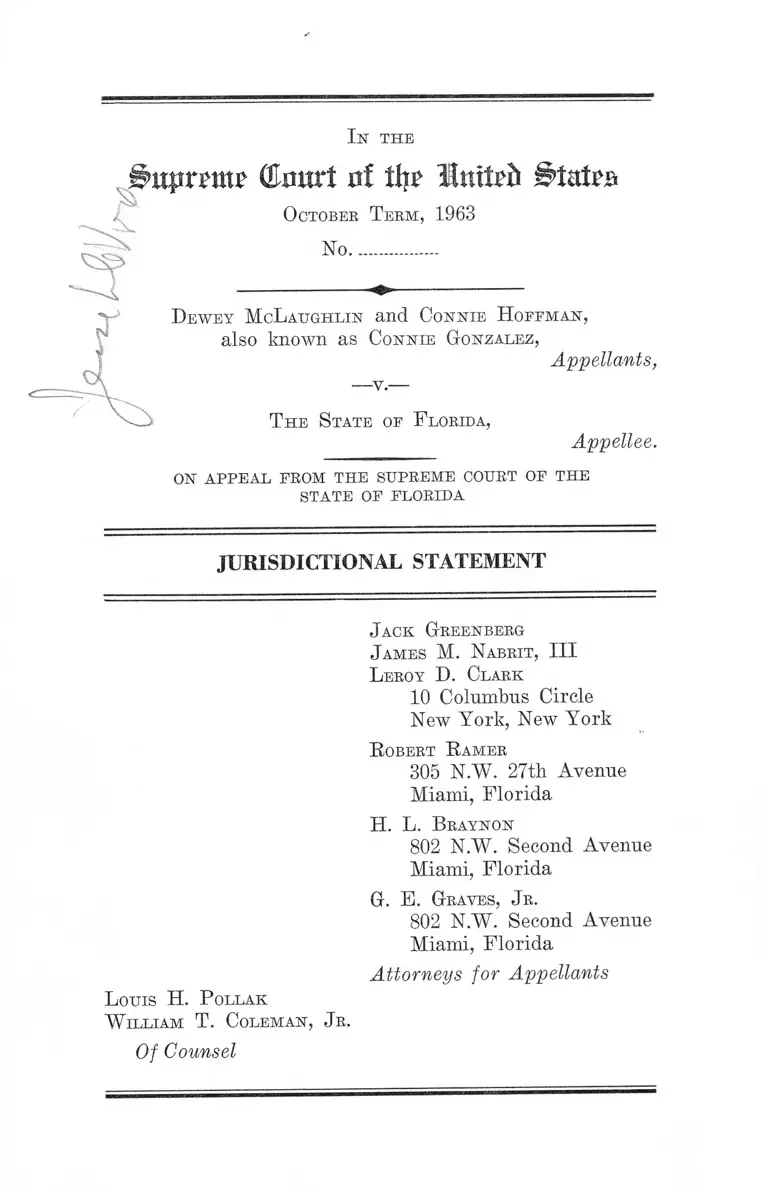

McLaughlin v. Florida Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McLaughlin v. Florida Jurisdictional Statement, 1963. 59287a69-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e56ed7c8-f393-42d3-988b-eb4cda09f5b9/mclaughlin-v-florida-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

Isr THE

#nprattT (to r t xs! tlî litltpit

October Term, 1963

No.................

Dewey M cL aughlin and Connie H offman,

also known as Connie Gonzalez,

Appellants,

T he State of F lorida,

Appellee.

ON appeal prom the supreme court of the

STATE OF FLORIDA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

R obert R amer

305 N.W. 27th Avenue

Miami, Florida

H. L. Braynon

802 N.W. Second Avenue

Miami, Florida

G. E. Graves, Jr.

802 N.W. Second Avenue

Miami, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

Louis H. P ollak

W illiam T. Coleman, Jr.

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinion Below ............................................... 2

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved .... 2

Questions Presented........~.................................................. 4

Statement ................- ...... ............. ........... ........................... 4

How The Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided 6

The Questions Presented Are Substantial ................... 9

I. The Court Below Affirmed Racially Discrimina

tory Criminal Convictions Under an Expressly

Racial Statute in Mistaken Reliance Upon Pace

v. Alabama, 106 U. S. 583. However, if Pace

Is Deemed Controlling, It Should No Longer

Be Followed Because It Is Inconsistent With

Many Subsequent Decisions of This Court .... 9

II. Appellants’ Conviction Denied Them Due Proc

ess and Equal Protection of the Laws Under

the Fourteenth Amendment in That a Com

mon Law Marriage Was Held to Be Unavail

able as a Defense to the Crime Because of a

Florida Law Declaring Interracial Marriages

Null and V o id .................................................... — 13

III. Appellants Were Denied Due Process of Law

Under the Fourteenth Amendment Because

the Statute Under Which They Were Convicted

Was Vague and Indefinite .................................. 16

Conclusion 19

A ppendix ..................................................................................... la

Opinion Below ................................................ —■ la

Final Judgment Denying Rehearing ..................... 5a

T able of Cases

Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U. S. 203 .... 11

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ....................................... 15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ................... 11

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ...........................10,12,14

Chaachow v. Chaachow, 73 So. 2d 830 (1954) ............... 13

Dorsey v. State Athletic Commission, 168 F. Supp.

149 (E. D. La. 1958) ...................................................... 11

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160............................... 11

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903, aff’g 142 F. Supp.

707 (M. D. Ala. 1956) ................................................... 11

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565 ................................. 10

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683 ................... 11

Hill v. U. S. ex rel. Weiner, 300 U. S. 105 ................... 12

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879, rev’g 223 F. 2d 93

(5th Cir. 1955) ................................................................ 11

Jackson v. Alabama, 348 U. S. 888 ................................. 14

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451..... ....................... 18

Largent v. Texas, 318 U. S. 418 ...................................... 2

Louisiana v. NAACP, 366 IT. S. 293 ............................... 17

ii

PAGE

I l l

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643 ........................................... 15

Maynard v. Hill, 125 TJ. S. 190 ....................................... 15

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 IT. S. 390 .................... .............. 15

Moore v. Missouri, 159 IT. S. 673 ..................................... 12

N A A OP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 ................................... 16

Naim v. Naim, 350 U. S. 891 (1955), app. dism. 350

U. S. 985 ........... ........ ...................... -........ -.................... 14

Navarro v. Baker, 54 So. 2d 59 (1951) ........................... 13

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U. S. 583 (1883) .......7, 8, 9,11,12,14

Perez v. Lippold, 32 Cal. 2d 711, 198 P. 2d 17 (1948) 14

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 TJ. S. 244 ............................ 10

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 IJ. S. 537 — ................ ................U

Poe v. Ullman, 367 O. S. 497 ..................... -.................... 15

Public Utilities Commission v. Poliak, 343 TJ. S. 451 .... 15

Reynolds v. United States, 98 U. S. 145 ......................— 15

Robinson v. California, 370 U. S. 660 ..... ......................... 10

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 .............. ...... ................. 12

Williams v. Bruffy, 96 U. S. 176 ..................................... 2

Statutes Involved:

Ala. Code, tit. 14, §360 ......... .................................... 12

Ark. Stats. Ann. §41-806 ......................................... - 12

Fla. Stat. Ann. §1.01(6) ..................................3,4,16,18

Fla. Stat. Ann. §741.11 ..... .........................................3,13

Fla. Stat. Ann. §798.03 ....................................-....... - 12

PAGE

IV

Fla. Stat. Ann. §798.04 ............................................... 11

Fla. Stat. Ann. §798.05 ...................2, 4, 5, 7, 9,10,13,16

La. Eev. Stats. §14:79 ............................................... 12

Nev. Eev. Stats, eh. 201.240 ....................................... 12

N. Dak. Eev. Code eh. 12-2213 ................................. 12

S. C. Code 1952, §5377 ............................................... 11

Tenn. Code Ann. §36-402 (1955) ............................... 12

Other Authorities:

PAGE

Greenberg, Eace Eelations and American Law (1959) 14

Hager, “ Some Observations on the Eelationship Be

tween Genetics and Social Science,” 13 Psychiatry

371 (1950) ....................................................................... 17

Weinberger, A Eeappraisal of the Constitutionality of

Miscegenation Statutes, 42 Cornell L. Q. 208

(1957) ............................................................................. 14,17

In the

(Hmtrt of tip Intteb

October T erm, 1963

No.................

Dewey McL aughlin and Connie Ho reman,

also known as Connie Gonzalez,

Appellants,

■—v.-

T he State of F lorida,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT OP THE

STATE OP FLORIDA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants appeal from the judgment of the Supreme

Court of Florida which affirmed, on May 1, 1963, the judg

ments of conviction entered by the criminal court of record

of Dade County, Florida. The final order of the Supreme

Court of Florida was entered May 30, 1963 with denial of

appellants’ petition for rehearing (R. 213). Appellants

submit this statement to show that this Court has juris

diction of the appeal and that a substantial question is

presented. In the alternative, should the Court regard

this appeal as having been improvidently taken, appel

lants pray that this statement be regarded and acted upon

as a petition for a writ of certiorari in accordance with

28 U. S. C. §2103.

2

Citation to Opinion Below

The criminal court of record of Dade County, Florida

did not render an opinion. The opinion of the Supreme

Court of Florida is reported in 153 So. 2d 1 (1963) and is

printed in the appendix hereto, infra, pp.

Jurisdiction

Appellants were convicted in the criminal court of

record of Dade County, Florida on June 24, 1962 of violat

ing Fla. Stat. Anno. §798.05. They appealed to the Su

preme Court of Florida contending that the convictions

violated the equal protection and due process clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment. On May 1, 1963, the Supreme

Court of Florida affirmed the convictions and decided in

favor of the validity of §798.05 under the Constitution of the

United States (R. 202). Petition for rehearing in the

Supreme Court of Florida was denied May 30, 1963

(R. 213).

Appellants filed Notice of Appeal in the Supreme Court

of Florida on August 29, 1963 (R. 215). Jurisdiction of

this Court on appeal rests upon 28 U. S. C. §1257 (2).

Williams v. Bruffy, 96 U. S. 176; Largent v. Texas, 318

U. S. 418.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. Petitioners were convicted of violating Fla. Stat.

Anno. §798.05 (Volume 22, Title 44, p. 227), which provides:

§798.05—Negro man and white woman or white man

and negro woman occupying same room.

“Any negro man and white woman, or any white man

and negro woman, who are not married to each other,

3

who shall habitually live in and occupy in the night

time the same room shall be punished by imprison

ment not exceeding twelve months, or by fine not

exceeding five hundred dollars.”

2. The case also involves Fla. Stat. Anno. §741.I I1

(Vol. 21, Title 42, p. 330) which provides:

§741.11—Marriages between white and negro persons

prohibited.

It is unlawful for any white male person residing or

being in this state to intermarry with any negro

female person; and it is in like manner unlawful for

any white female person residing or being in this

state to intermarry with any negro male person;

and every marriage formed or solemnized in contra

vention of the provisions of this section shall be

utterly null and void, and the issue, if any, of such

surreptitious marriage shall be regarded as bastard

and incapable of having or receiving an estate, real,

personal or mixed, by inheritance.

3. The case also involves Fla. Stat. Anno. §1.01 (Vol. 1,

Title 1, p. 124) providing:

§1.01—Definitions.

. . . (6) The words “negro” , “ colored” , “ colored per

sons” , “ mulatto” or “ persons of color” , when applied

to persons, include every person having one-eighth

or more of African or negro blood.

4. This case also involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

1 Petitioners were not charged under this law.

4

Questions Presented

Do these convictions violate the equal protection and due

process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution where: t

J

(1) The State has

created a crime expressly defined in terms of race which

punishes Negroes and whites who engag’e in certain con

duct together, but does not forbid such conduct engaged in

by Negroes only or whites only?

(2) Common law marriage is a defense for a couple

charged under Fla. but was unavail

able to appellants because K!;h pro

hibits marriage between Negroes and whites?

(3) Florida’s purported definition of “ Negro” and

“ white” persons ..Statr~A&BO,-~^LQl— an essential

element of the crime, oroatod-for Fla Sfcat. Annoi —

is so vague and indefinite as applied as to afford no fair

warning to appellants or standard of criminality for the

court or the jury?

Statement

Appellants were arrested in February 1962 and charged

with having violated Fla. Stat. Anno. §798.05 in that “ the

said Dewey McLaughlin, being a Negro man, and the said

Connie Hoffman, also known as Connie Gonzalez, being

1a white woman, who were not married to each other, did

habitually live in and occupy in the nighttime the same

room” (R. 10). Mr. McLaughlin, a Spanish-speaking man

born in Honduras (but apparently a U. S. citizen) was

employed in a Miami Beach hotel (R. 140). Appellant

Connie Hoffman began residing in a one room apartment

5

at 732 Second Street, Miami Beach, Florida in April 1961

(R. 37). The owner of the premises, Mrs. Dora Goodnick,

testified that she saw McLaughlin at various times in

December 1961 and February 1962 enter the apartment

house at night and leave in the morning (R. 38-40). Mrs.

Goodnick also claimed to have seen him showering in the

bathroom and heard him talking to appellant Hoffman

in her apartment at night (R. 50-52). Appellant Hoffman

told Mrs. Goodnick that McLaughlin was her husband

(R. 38). Mrs. Goodnick stated that she was disturbed

that a colored man was living in her house and conse

quently reported the situation to the police (R. 39).

Detectives Stanley Marcus and Nicolas Valeriana of

the Miami Beach Police Department went to appellant

Hoffman’s apartment at 7:15 P.M. February 23, 1962,

to investigate a charge that she was contributing to the

delinquency of her minor son (R. 60, 75). They knocked

at the door and a man’s voice answered, “ Connie, come

in,” but the door was not opened (R. 61-62). Valeriana

went to the back of the apartment and found McLaughlin

exiting from the rear door (R. 70). In the questioning

which followed, McLaughlin admitted that he had been

living there with Hoffman (R. 73) and that on at least one

occasion he had had sexual relations with her (R. 80L

But, there was no charge or conviction of fornication

or adultery. The detectives also observed pieces of

McLaughlin’s wearing apparel draped across furniture in

the room (R. 77). Appellant Hoffman came to the police |

station where McLaughlin was being held and while there

stated that she was living with him but thought that this

was not unlawful (R, 82). At trial Detective Valeriana

identified her as a white woman and Dewey McLaughlin

as a Negro from their appearances (R. 100-101, 103).

Josephine De Cesare, a secretary in the City Manager’s

Office, testified that in the process of securing a civilian

6

registration card, McLaughlin stated in January 1961,

that he “was separated and that his wife’s name was

Willie McLaughlin” (R. 125, 127). Dorothy Kaabe, a child

welfare worker in the Florida State Department of Public

Welfare testified that in an interview on March 5, 1962,

appellant Hoffman stated that she began living with

McLaughlin as her common law husband in September or

October 1961 but had never had a formal marriage to

him (R. 143).

Each defendant was convicted by a jury and each was

sentenced to thirty days in the County Jail at hard labor

and fined $150.00, plus costs, and in default of such pay

ment to an additional 30 day term (R. 14-17).

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

On March 1, 1963, an information was filed against ap

pellants charging them with violation of Fla. Stat. Anno.

§798.05 (R. 10). They filed a motion to quash the infor

mation alleging that §798.05 was contrary to the Four

teenth Amendment of the United States Constitution in

that it was vague, denied due process and equal protec

tion of the laws, and was an invasion of the right to

privacy (R. 12-13). The Motion to Quash was denied

(R. 14). During trial, appellants moved for directed ver

dict on the grounds that criteria for identifying a “ Negro”

under §798.05 must be established by reference to Fla.

Stat. Anno. §1.01 and that the standard of proof of this

element was vague, in terms of evidence introduced by

the state and as set forth in §1.01 (R. 104-108, 152). Appel

lants specifically related the motion for directed verdict

to the unconstitutional vagueness of §798.05 (R. 104-105),

asserting that no one could be apprised that his behavior

was prohibited given the unclear definition of the term

7

“ Negro” (R. 104-105). The motion for directed verdict

was denied (R. 108, 152).

Upon submitting the case to the jury, the judge gave

instructions that in Florida a Negro and a white person

could not have lawfully married, either by common law

or formal ceremony (R. 161). No exception was taken to

this instruction at the trial.

On July 3, 1962, defendants filed a motion for new trial

on the grounds that the court erred in overruling the mo

tion to quash the information which had alleged that

§798.05 was contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment. Error

was also claimed in that the trial court had permitted the

testimony of Detective Valeriana, based on his observation

of the appearance of appellant McLaughlin, to satisfy the

statutory criteria defining the term “ Negro” (R. 17-18).

The motion for new trial was denied (R. 19).

On appeal the assignment of errors again alleged that

Fla. Stat. Anno. §798.05 violated the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the United States Constitution in that it was

vague and indefinite, operated to deny equal protection

and due process of law, and authorized an undue invasion

of the right of privacy (R. 21-22). Error was also as

signed to the overruling of the motion for new trial and

to the overruling of the objection to the standard of proof

accepted for the identification of appellant McLaughlin

as a Negro (R. 22).

In affirming the conviction, the Supreme Court of Florida

discussed only whether the special crime of interracial

cohabitation was valid under the Fourteenth Amendment,

and sustained the law relying on Pace v. Alabama, 106

U. S. 583. The court stated:

This cause is here on appeal from the Criminal

Court of Record of Dade County. The trial court di

8

rectly passed upon the validity of a State statute and

we, therefore, have jurisdiction . . . (R. 202).

# # *

The appellants seek adjudication of their right to

engage in integrated illicit cohabitation upon the same

terms as are imposed upon the segregated lapse. But,

as was admitted by counsel in argument, this appeal

is a mere way station on the route to the United

States Supreme Court where defendants hope that,

in the light of supposed social and political advances,

they may find legal endorsement of their ambitions.

This Court is obligated by the sound rule of stare

decisis and the precedent of the well written decision

in Pace, supra. The Federal Constitution, as it was

when construed by the United States Supreme Court

in that case, Pace v. Alabama is quite adequate but

if the new-found concept of “ social justice” has out

dated “ the law of the land” as therein announced and,

by way of consequence, some new law is necessary,

it must be enacted by legislative process or some other

court must write it (R. 204-205).

Appellants’ brief in the Florida Supreme Court argued

that the instruction of the jury in accordance with the

miscegenation law violated their rights (R. 180-183). The

state countered by arguing that the law was valid under the

Fourteenth Amendment and that the instruction could

only be a harmless error (R. 195-199). Appellants sought

rehearing attempting to secure the Florida Supreme

Court’s discussion of this issue (R. 207), but rehearing

was denied without opinion (R. 213).

9

The Questions Presented Are Substantial

I

The Court Below Affirmed Racially Discriminatory

Criminal Convictions Under an Expressly Racial Statute

in Mistaken Reliance Upon Pace v. Alabama, 106 U. S.

583. However, if Pace Is Deemed Controlling, It Should

No Longer Be Followed Because It Is Inconsistent With

Many Subsequent Decisions o f This Court.

This case presents a substantial question deserving ple

nary hearing before this Court on appeal. The conviction

of appellants represents a manifest discrimination, erro

neously sought to be justified by the court below as com

pelled by Pace v. Alabama, 106 IT. S. 583 (1883), a case

involving a discrete issue. Tony Pace and his co-defendant

would have been guilty of a crime in Alabama even if they

had both been white—though, to be sure, their punishment

would have been less.

However, if Dewey McLaughlin and Connie Hoffman had

been found by the jury to be both white or both Negroes

they would have been set free. But for their race (as de

termined by the jury) no crime would have been committed

under §798.05. This law makes it a crime punishable by

12 months in jail and a $500 fine for an unmarried man and

woman habitually to live in and occupy the same room in

the nighttime, if (and only if) one is a Negro and the other

is white. Unlike the Alabama situation in Pace v. Alabama,

106 U. S. 583, Florida has not made it a crime at all for a

man and woman of the same race to engage in the identical

conduct charged. There is no general nonracial (or single-

racial) counterpart of §798.05 in the Florida statutes. Flor

ida recognizes common law marriages (see infra p. 13).

1 0

Thus, the conduct with which appellants were charged is

licit under Florida law for persons of the same race.

Conviction under this law involves so gross a denial of

equal protection as to command the attention of the Court.

/^Stripped of emotional overtones, the case is simple indeed.

J (jVho would doubt that the equal protection clause would

y invalidate a scheme of laws providing that it was a crime

for automobiles occupied by Negroes and whites to exceed

25 m.p.h. but providing no speed limit for any other auto-

Ljmobiles. |Snch a legal scheme—and innumerable hypotheti

cal parallels—would probably be laughed out of court with

dispatch. But our hypothesized speeding law shares the

same infirmity as-f?98ifi5-doos—it punishes an activity only

if and because it is interracial.

Florida has not advanced (and cannot advance) any con

stitutionally acceptable basis for making the conduct de

scribed by §798.05 a crime only when persons of different

races are involved.2

As early as 1896, this Court said that criminal justice

must be administered “without reference to considerations

based on race,” Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565, 591.

From Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 to Peterson v.

Greenville, 373 U. S. 244, the Court has repeatedly struck

down laws attempting to require separation of the races

by imposing criminal penalties. Such a law was involved in

2 Of course, the power to regulate sexual immorality

is not challenged.^Tmt tins law does not require any proof of

sexual, or other misconduct; it merely regulates who occupies a

room. (There is some reason to doubt whether, aside from the racial

dimensions of the law, Florida can justify punishing this conduct]

O^-BeUnson^rPaiifm'Ma,hTTnjrS-66th In numerous situations

such a nonracial statute would not seem justified; its coverage

would include such cases as unmarried members of the same family

occupying a room, nurses and patients, the physically handicapped,

etc.

1 1

Dorsey v. State Athletic Commission, 168 F. Supp. 149

(E. D. La. 1958), affirmed 359 U. S. 533, where Louisiana

made it a crime punishable by a year in jail for a Negro and

a white person to engage in boxing matches and other

athletic contests. No one contested Louisiana’s power to

prohibit boxing; that. State was denied the power to allow

it generally but prohibit interracial contests. Many com

parable laws have been invalidated. For example, desegre

gated golf matches were criminally punishable by the law

struck down in Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879, reversing

223 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir. 1955), and South Carolina’s school

segregation law (S. C. Code 1952, §5377) merely made it a

crime for any person to attend a school established for per

sons of another race. Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U. S. 483. See also Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903, aff’g

142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956).

In short, “ race is constitutionally an irrelevance” (Ed

wards v. California, 314 U. S. 160, 185), and “ racial differ

ences cannot provide a valid basis for governmental action”

(Ahington School District v. Schempp, 374 U. S. 203, 10 L.

ed. 2d 844, 912, Justice Stewart dissenting). See also, Goss

v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683, 10 L. ed. 2d 632, 635,

and cases cited. In the words of the first Justice Harlan,

the Constitution is “ color blind,” Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

U. S. 537, 558. The decision below is in the teeth of this

Court’s repeated holdings that racial segregation laws are

invalid.

As noted above, this case is different from Pace v. Ala

bama, supra, where the conduct alleged was criminal irre

spective of the race of the parties. Appellants were not

charged with violating Fla. Stat. Anno. §798.04, prohibiting

interracial fornication; if they had been the case would be

like Pace, for the non-racial law covering the same conduct

1 2

(Fla. Stat. §798.03) carries a lesser penalty.3 But appel

lants have no hesitancy in urging that Pace should be over

ruled if its reasoning—that interracial illicit conduct is a

“ different crime” from that punished by the general law—

is thought to extend to this case. Pace stands as an isolated

vestige of the “ separate but equal” era inconsistent with the

entire development of the law at least since Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U. S. 60. It is notable that this Court has cited

Pace only two times in the eighty years since it was decided;

race discrimination was not an issue in either case.4 It ought

to be overruled. No segregation law would ever be invali

dated under the reasoning of Pace that equality is assured

where a Negro and white co-defendant are liable to the same

punishment. Cf. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22.

The issue involved here is not confined to Florida; at

least six other states have laws similar to §798.05.5

3 If this case is viewed as presenting the Pace issue, the follow

ing facts would be pertinent. Appellants were fined $150 and given

a 30 day jail term. (They were liable under §798.05 to a $500 fine

and a 12 month term.). The .maximum sentence under the general

fornication law (§798.03) is a $30 fine and a 3 months term. The

interracial fornication and adultery law (§798.04) carries a possi

ble $1,000 fine and 12 months in jail.

4 See e.g. Moore v. Missouri, 159 U. S. 673, 678 (1895) ■ Hill v.

United States ex rel. Weiner, 300 U. S. 105, 109 (1937).

5 Ala. Code tit. 14, §360 (adultery, marriage, or fornication

between white and Negro, 2 to 7 years) ; Ark. Stats. Ann. §41-806

(concubinage between white and Negro, 1 month to 1 year) ; La.

Rev. Stats. §14:79 (miscegenation statute includes habitual cohabi

tation of racially mixed couple; up to 5 years) ; Nev. Rev. Stats, eh.

201.240 (white and colored persons living and cohabiting in state

of fornication, $100 to $500, 6 months to 1 year, or both); N. Dak.

Rev. Code ch. 12-2213 (unmarried racially mixed couple occupying

same room; up to 1 year, $500 fine, or both) ; Tenn. Code Ann.

§36-402 (1955) (marriage or living together as man and wife of

racially mixed couple prohibited; 1 to 5 years or fine and imprison

ment in county jail).

13

II

Appellants’ Conviction Denied Them Due Process and

Equal Protection o f the Laws Under the Fourteenth

Amendment in That a Common Law Marriage Was Held

to Be Unavailable as a Defense to the Crime Because o f a

Florida Law Declaring Interracial Marriages Null and

Void.

In charging the jury the judge stated (B. 161) :

“ I further instruct you that in the State of Florida it is

unlawful for any white female person residing or being in

this state to intermarry with any Negro male person and

every marriage performed or solemnized in contravention

of the above provision shall he utterly null and void.”

This charge was in accord with Fla. Stat. Anno. §741.11.

The statute under which appellants were prosecuted

(§798.05) makes marriage a defense to the charge, and Flor

ida gives full recognition to common law marriage, accord

ing it the same legal incidents available in a formal

marriage. (See, e.g., Chaachow v. Chaachow, 73 So. 2d 830

(1954); Navarro v. Balter, 54 So. 2d 59 (1951).) Of course,

one of the ways of proving common law marriage is by

“ repute” and there was evidence of representations by ap

pellant that McLaughlin was her husband (B. 38, 143). But

the sufficiency of the evidence is not in issue because the

judge’s charge, based on Fla. Stat. Anno. §741.11, removed

from the jury’s consideration any evidence tending to estab

lish the defense of marriage if they found that one appellant

was Negro and that the other was white.

The constitutionality of the anti-miscegenation statute

(§741.11) is relevant because the crime requires appel

lants to be “ unmarried” and the indictment so charged.

14

The question is whether a state can forbid parties by

statute from contracting a lawful marriage within the

state because of their race, and then convict the same

parties for entering into “unlawful” cohabitation?

This Court has not determined the validity of a mis

cegenation law. Pace v. Alabama, supra, did not involve

a marriage; although the statute in Pace forbids inter

marriage as well as adultery and fornication, no charge

of intermarriage was made. No decision on the merits of

this issue was reached by this Court in either Naim v.

Naim, 350 U. S. 891 (1955), app. dismissed 350 U. S. 985,

or Jackson v. Alabama, 348 U. S. 888, a denial of certiorari.

Miscegenation laws have been recently on the books in

over 20 states and many others have been repealed, some

in recent years.6 These laws have been upheld by at least

twelve states’ highest courts.7 But the California Supreme

Court has held its law unconstitutional under the Four

teenth Amendment in Peres v. Lippold, 32 Cal. 2d 711,

198 P. 2d 17 (1948).

It seems quite clear in view of subsequent decisions that

Perez v. Lippold reached the proper result under the

Fourteenth Amendment. This Court’s many decisions hold

ing racial segregation laws invalid, from Buchanan v.

Warley, in 1917, to date, destroy any possible argument

in favor of the validity of §741.11. The racists’ “ pure

races” theory and other similar notions offered in at

tempted justification for such a law have all been rejected

in connection with other segregation laws. (See generally

Weinberger, op. cit.)

6 Lists of the laws appear in Weinberger, A Reappraisal of the

Constitutionality of Miscegenation Statutes, 42 Cornell L. Q. 208

(1957), and Greenberg, Race Relations and American Law, Appen

dix A. 28, pp. 397-398 (1959).

7 Weinberger, op. cit. 209.

15

The states have traditionally exercised control over

the marital institution. Maynard v. Hill, 125 IJ. S. 190;

Reynolds v. United States, 98 U. S. 145. But the liberty

protected by the due process clause “ is not confined to

mere freedom from bodily restraint” ; rather, it “ extends

to the full range of conduct which the individual is free to

pursue, and it cannot be restricted except for a proper

governmental objective.” Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S.

497, 499. The right to marry is a protected liberty under

the Fourteenth Amendment. In Meyer v. Nebraska, 262

U. S. 390, 399, the Court said:

While this Court has not attempted to define with

exactness the liberty thus guaranteed (by the Four

teenth Amendment), the term has received much con

sideration, and some of the included things have been

definitely stated. Without doubt, it denotes not merely

freedom from bodily restraint, but also the right of

the individual to . . . marry, establish a home and bring

up children. . . .

The essence of the right to marry is a freedom to join in

marriage with the person of one’s own choice.

Another incident of the right to marry is the right of

privacy. Under the circumstances of these convictions,

not only may a private relationship be subjected to crimi

nal prohibition but a private place'—the home—is unjustifi

ably subjected to governmental regulation, and the types

of invasion of privacy attendant upon investigation of

crime, e.g., surveillance, searches, etc. The due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protects the right

of privacy (Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643; see also Poe v.

Ullman, 367 U. 8. 497, 517-522 (dissenting opinion); cf.

Public Utilities Commission v. Poliak., 343 U. S. 451, 467,

469 (dissenting opinion)), and privacy of association

1 6

(NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449) from unwarranted

state interference. The state cannot show that any valid

governmental purpose is furthered by the deprivation of

liberty occasioned by the miscegenation law.

Ill

Appellants Were Denied Due Process of Law Under

the Fourteenth Amendment Because the Statute Under

Which They Were Convicted Was Vague and Indefinite.

In order to convict under §798.05 the state must prove

that one party is a “ Negro.” The purported definition of

“ Negro” occurs in §1.01 of the Florida statutes, which

holds any person with “ one eighth or more of African or

Negro blood” to be a “ Negro.” Section 1.01, on its face,

and as applied at the trial, is so ambiguous and suscep

tible of such diversified interpretation that the standard

of clarity required by the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment is lacking.

No reasonably unvarying definition can be given to the

terms “ African or Negro blood.” First, one deficiency of

the definition is readily apparent, i.e., that “ Negro” is

defined by using the word sought to be defined—in the

phrase “ Negro blood.” This is no help at all. “ African”

might seem at first to be a finite concept. But does Florida

really mean to refer to all citizens of African countries—

to the citizens of North Africa and the Afrikaners of

South Africa for example! When it is considered that the

population of the vast African continent is diverse and

constantly changing, the definition is exposed as mean

ingless. But of course there is a great deal more. There

is no such thing as African or Negro “blood” in any genetic

or biological sense, and there is no known method by which

17

proportions of such “ blood” (such as %th) can be deter

mined. One scholar remarked:

Laws prohibiting marriage between “whites and

persons having one-eighth or more of Negro blood”

are compounded of legal fiction and genetic nonsense.

Hager, “ Some Observations on the Relationship Be

tween Genetics and Social Science,” 13 Psychiatry

371, 375 (1950).8

Florida’s definition, employing fractions of blood, rests

on the assumption that somewhere it is possible to find,

and to ascertain that one has found, a racially pure per

son— e.g., a man with 100% Negro “blood.” But neither

the statute nor science tells us how this fine calculation

and determination possibly can be made. Unless one can

locate such purity somewhere the whole system of frac

tions breaks down and becomes unserviceable. It is, of

course, even more remarkable to make a man legally bound

to know and act on the basis of the racial “blood” of his

great-grandparents or even more remote ancestors. This

is comparable to the Louisiana statute invalidated by this

Court which required “ the impossible,” namely, that one

give an affidavit that none of the officers in his organization

were Communists or subversives. Louisiana v. NAACP,

366 U. S. 293.

In this case the trial court sought to avoid all these

problems by ignoring the statutory framework (the %th

rule) and simply allowing a jury to determine race on a

policeman’s testimony as to appellants’ appearance (R.

100-101, 103). When this standard is made an “ appear

ance” standard—the average man’s or indeed juror’s

8 And see generally the authorities collected in Weinberger,

op. cit. 217-221.

18

opinion as to what race appearance indicates—then the

last pretense of statutory clarity is gone. The appearance

standard is obviously a varying and easily shifting method

in which a man’s race is not an objective thing at all, but

rather springs from the mind and eye of each beholder.

That such a standard should not be used in sending people

to jail is so obvious that it need not be labored. Differ

ences of opinion, perception, etc., as to race based on

appearance are a commonplace of life. To make a man

conduct his affairs on the basis of a preliminary guess as

to what his race will be in the opinion of some future un

known witnesses and jurors using an appearance rule

places liberty on a slippery surface unworthy of the crimi

nal law of a civilized society. It is easily as vague as the

term “ gangster” in the New Jersey law invalidated in

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451. The vice is com

pounded by the fact that §1.01(6) never gave a hint that

some rough rule of thumb was involved; on its face it

pretends mathematical precision.

19

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that for the foregoing rea

sons the questions presented are substantial and the Court

should herein determine this appeal, and upon consideration

thereof reverse the judgments below.

.Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greekberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

R obert R amer

305 N.W. 27th Avenue

Miami, Florida

H. L. Braykos

802 N.W. Second Avenue

Miami, Florida

G. E. Graves, Jr.

802 N.W. Second Avenue

Miami, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

Louis H. P ollak

W illiam T. Colemak, Jr.

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Opinion Below

Not F inal Until T ime E xpires to F ile R ehearing P etition

and, ie F iled, Determined

In the

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

January Term, A.D. 1963

Case No. 31,906

Dewey McL aughlin and

Connie H oeeman also

known as Connie Gonzalez,

-v -

Appellants,

State oe F lorida,

Appellees.

Opinion filed May 1,1963

An Appeal from the Criminal Court of Record for Dade

County, Gene W illiam s , Judge

R obert R amer, H. L. Braynon and G. E. Graves, for

Appellants

R ichard W. E rvin, Attorney General, and James G.

Mahorner, Assistant Attorney General, for Appellees

Caldwell, J.

This cause is here on appeal from the Criminal Court of

Record of Dade County. The trial court directly passed

2a

upon the validity of a State statute and we, therefore, have

jurisdiction.

Defendants are charged with having violated Fla. Stat.

§798.051 in that “ the said Dewey McLaughlin, being a negro

man, and the said Connie Hoffman, being a white woman,

who were not married to each other did habitually live in

and occupy in the nighttime the same room.” The defen

dants moved to quash the information on the ground that

the aforesaid statute was in violation of the Federal and

State Constitutions. The motions were denied. Defendants

were then arraigned and entered pleas of not guilty. The

jury trial terminated in a verdict of guilty, a sentence of

thirty days in the county jail and a fine of $150 for each

defendant.

The defendants contend they were denied equal protec

tion of the laws because “ Firstly, the law provides a special

criminal prohibition on cohabitation solely for persons who

are of different races; or, secondly, if this special statute is

equated with the general fornication statute, the higher

penalties are imposed on the person whose races differ than

would be applicable to persons of the same race who commit

the same acts.”

In Pace vs. Alabama,2 the Supreme Court of the United

States upheld an Alabama Statute3 prohibiting interracial

marriage, adultery or fornication, against the contention

1 Fla. Stat. §798.05

“Any negro man and white woman, or any white man and

negro woman, who are not married to each other, who

shall habitually live in and occupy in the nighttime the

same room shall be punished by imprisonment not exceed

ing twelve months, or by fine not exceeding five hundred

dollars.”

2 106 U. S. 207 (1883).

3 Ala. Code of 1876, §4189 (now Ala. Code, Title 14, §360

[1958]).

3a

that it denied equal protection of the law. Another Alabama

Statute4 prohibited adultery or fornication between mem

bers of the same race but provided a less severe maximum

penalty. The Supreme Court speaking through Mr. Justice

Field held:

“ Equality of protection under the laws implies not only

accessibility by each one, whatever his race, on the same

terms with others, to the courts of the country for the

security of his person and property, but that in the

administration of criminal justice he shall not be sub

jected, for the same offense, to any greater or different

punishment . . .

“ The defect in the argument of counsel, consists in his

assumption that any discrimination is made by the laws

of Alabama in the punishment (sic) provided for the

offense for which the plaintiff in error was indicted,

when committed by a person of the African race and

when committed by a white person. The two sections of

the Code cited are entirely consistent. The one pre

scribes, generally, a punishment for an offense com

mitted between persons of different sexes; the other

prescribes punishment for an offense which can only

be committed where the two sexes are of different races.

There is in neither section any discrimination against

either race. Section 4184 equally includes the offense

when the persons of the two sexes are both white and

when they are both black. Section 4189 applies the

same punishment to both offenders, the white and the

black. Indeed, the offense against which this latter sec

tion is aimed cannot be committed without involving

the persons of both races in the same punishment.

4 Ala. Code of 1876, §4184 (now Ala. Code, Title 14, §16

[1958]).

4a

Whatever discrimination is made in the punishment

prescribed in the two sections is directed against the

offense designated and not against the person of any

particular color or race. The punishment of each

offending person, whether white or black, is the same.”

The appellants seek adjudication of their right to engage

in integrated illicit cohabitation upon the same terms as are

imposed upon the segregated lapse. But, as was admitted

by counsel in argument, this appeal is a mere way station

on the route to the United States Supreme Court where

defendants hope that, in the light of supposed social and

political advances, they may find legal endorsement of their

ambitions.

This Court is obligated by the sound rule of stare decisis

and the precedent of the well written decision in Pace,

supra. The Federal Constitution, as it was when construed

by the United States Supreme Court in that case, is quite

adequate but if the new-found concept of “ social justice”

has out-dated “ the law of the land” as therein announced

and, by way of consequence, some new law is necessary, it

must be enacted by legislative process or some other court

must write it.

Affirmed.

R oberts, C.J., T errell, T homas, T hornal and O’Cownell,

JJ. , concurring. Drew, J agrees to judgment.

5a

Final Judgment Denying Rehearing

In the

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

January Term, A.D. 1963

Thursday, May 30, A.D. 1963

Case No. 31,906

Dewey McL aughlin and

Connie H offman also

known as Connie Gonzalez,

Appellants,

State of F lorida,

Appellee.

On consideration of the Petition for Rehearing filed by

Attorneys for Appellants,

It is ordered by the Court that the said petition be, and

the same is hereby, denied.

A True Copy,

Test:

Guyte P. M cCord

Clerk Supreme Court

(The Mandate From This Court Has Today Been Issued and

Mailed to the Clerk of the Criminal Court of Record for

Dade County)

'