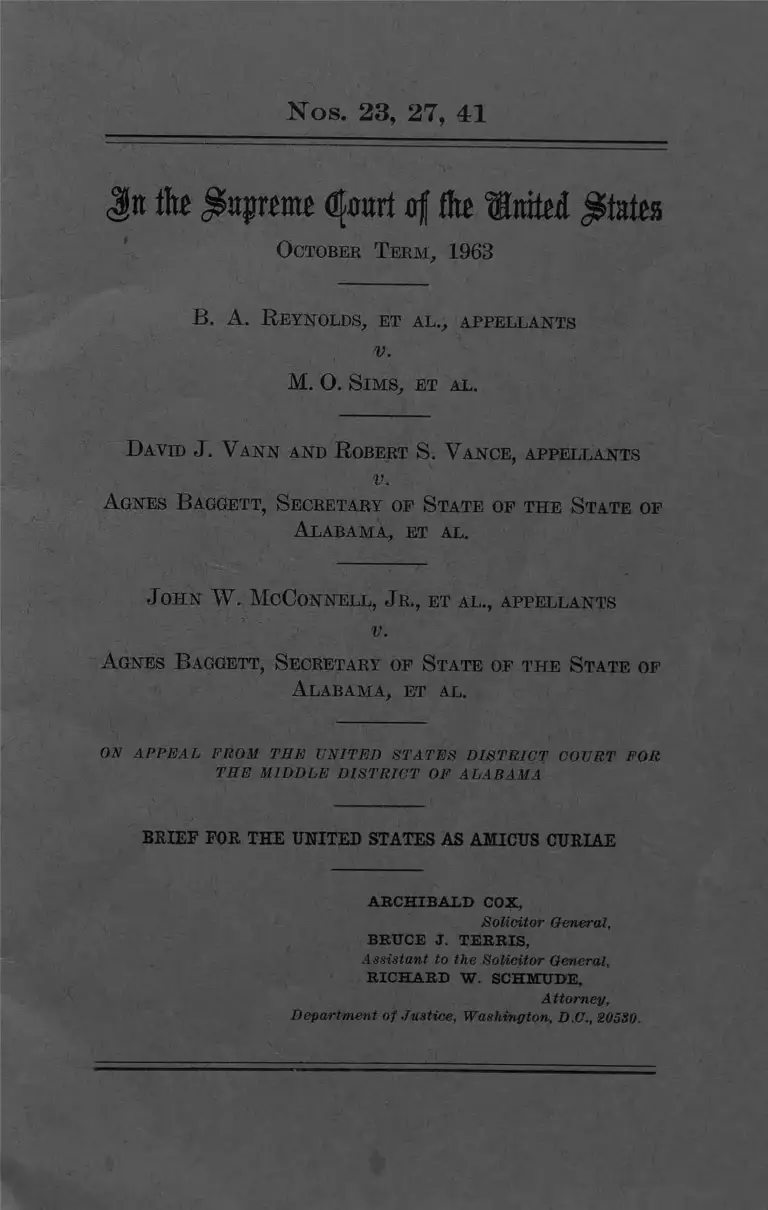

Reynolds v Sims Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1963

62 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Reynolds v Sims Brief Amicus Curiae, 1963. 04cc3e13-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e57ce868-32c5-4064-9787-c71060b7f15d/reynolds-v-sims-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 23, 27, 41

Jn to Jsstprtme Gfourt of to ® nM States

O ctobee T erm , 1963

B. A . R eynolds, et al ., appellants

v.

M. O. S im s , et al.

D avid J. V ann and R obert S. V ance, appellants

v,

A gnes B aggett, Seceetaey op S tate op the State op

A labama , et al.

J ohn W . M cConnell, J e., et al., appellants

v.

A gnes B aggett, Seceetaey op S tate of the S tate of

A labama, et al.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE M ID D LE DISTRICT OF ALABAM A

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

A R C H IB A L D COX,

Solicitor General,

BRUCE J. T E R R IS ,

Assistant to the Solicitor General,

R IC H A R D W . SCHMXTDE,

Attorney,

Departm ent o f Justice, Washington, D.C., 20530.

I N D E X

Opinions below____________________________________________ 2

Jurisdiction__ .____________________________________________ 2

Questions presented__________________________ 2

Constitutional provisions, statutes, and proposed constitu

tional amendments involved_____________________________ 3

Interest o f the United States_______________________________ 3

Statement_________________________________________________ 4

Argument:

Introduction and summary_____________________ 17

I. The pre-existing apportionment of the Alabama

legislature violated the equal protection clause

because it created gross inequalities in per capita

representation without rhyme or reason_______ 22

II. The apportionment provided by the proposed con

stitutional amendment would violate the equal

protection clause by subordinating popular rep

resentation to the representation of political

subdivisions to such a degree as to create gross

inequalities among voters and give control of

both houses o f the legislature to small minorities

o f the people________________________________ 30

III. The apportionment provided by the Crawford-

Webb Act would violate the equal protection

clause, first, by preserving the crazy-quilt upon

equal representation in the Senate and, second,

by subordinating popular representation in the

legislature as a whole to the representation of

political subdivisions to such a degree as to

create gross inequalities among voter’s and give

control to small minorities of the people_______ 37

IV . The temporary apportionment ordered by the dis

trict court as interim relief is not an abuse of

discretion____________________________________ 43

Conclusion________________________________________________ 43

Appendix_________________________________________________ 49

709- 522— 63------ 1 . . .

II

CITATIONS

Cases:

Anbury Park Press, Inc. v. Wooley. 33 N.J. 1, 161 A. Pag0

2d 705__________ 1_________________________________ 45

Askew v. jHale County, 54 Ala. 639______ :_____________ 35

Baker v. Carr, 206 F. Supp. 341_____________________29,45

Baker v. Cart', 369 U.S. 186_________________________ 8,

9,10,13,18,20,22,28

Borden's Farm Products Co. v. Baldwin, 293 U.S. 194_ 29

Butcher v. Trimarchi, 28 Pa. Dist. & County Rep.

2d 537____________________________________________ 45

Fortner v. Barnett, No. 59,965, Chancery Court, First

Judicial District, Hinds County, Mississippi______44,46

Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U.S. 464______________________ 23

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368__ ___________________ 34

Harris v. Shanahan, District Court, Shawnee County,

Kansas, decided July 26, 1962_____________________ 45

Hartford Steam Boiler Ins. Co. v. Harrison, 301 U.S.

459_______________________ ______ 1_______________ 29

International Boxing Club v. United States, 358 U.S.

242_______________________ 44

International Salt Co. v. United States, 332 U.S. 392_ 44

League of Nebraska Municipalities v. Marsh, 209 F.

Supp. 189_________________________________________ 45,46

Legislative Reapportionment, In re, 374 P. 2d 66_____ 45

Lein v. Sathre, 205 F. Supp. 536_____________________ 45

Magraw v. Donovan, 163 F. Supp. 184______________ 45

Mann v. Davis, 213 F. Supp. 577, pending on appeal,

No. 69, this Term_________________________________ 29,45

Maryland Committee for Fair Representation v. Tawes,

No. 29, this Term________________________ 3, 30, 31, 33, 35

Maryland Committee for Fair Representation v. Tawes,

228 Md. 412______________________________________ 45

Maryland Committee for Fair Representation v. T awes,

Circuit Court, Anne Arundel County, Maryland, de

cided May 24, 1962______________________________ 45

Mercoid Corp. v. Mid-Continent Investment Co., 320

U.S. 661_____________ ____________ - _________ __1 44

Mikell v. Rousseau, 183 A. 2d 817---------------------------- 45

Moore v. Walker County, 236 Ala. 688,185 So. 175____ 35

Moss v. Burkhart, 207 F. Supp. 885------------------------ 45

Moss v. Burkhart, U.S.D.C., W.D. Okla., decided July

17, 1963______ 19,30,44

Opinion of the Justices, 263 Ala. 158, 81 So. 2d 881------ 7,15

xn

Cases—Continued PagB

Opinion of the Justices, 254 Ala. 185, 47 So. 2d 714__ 7,15

: Rice, E x parte, 143 So. 2d 848______________________ 7

Sincock v. Duffy, 215 F. Supp. 169, pending on appeal

sub. nom. Roman v. Sincock, No. 307, this Term___ 29, 45

Sincock v. Terry, 207 F. Supp. 205___________ _______ 45

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535__ ____ ___________ 34

Sobel v. Adams, 208 F. Supp. 316_____________ 19, 29, 44,45

State v. Butler, 225 Ala. 191, 142 So. 531____________ 35

Stevens v. Faubus, 354 S.W. 2d 707__ ________________ 44

.Sweeney v. Notte, 183 A. 2d 296_____________________ 30

Thigpen v. Meyers, 211 F. Supp. 826, pending on

appeal, No. 381, this Term________________________29,45

Toombs v. Fortson, U.S.D.C., N.D. Ga., decided Sep

tember 5, 1962__________________________________19,44,45

Toombs v. Fortson, 205 F. Supp. 248 ____________ 29, 45, 46

United States v. Oarolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144_ 35

Virginian Ry. Go. v. System Federation No. Ifi, 300

U.S. 545_________________________________________ 43

Waid v. Pool, 255 Ala. 441__________________________ 7

Wesberry v. Sanders, No. 22, this Term_____________ 36

Tick Wo. v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356__________________ 34

Constitution and statutes:

U.S. Constitution:

Fourteenth Amendment_____________________________ 4,

6, 7,12,14,17,19, 20,21, 26,29,31,33, 40,48

Civil Eights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1983 and 1988__________ 4

28 U.S.C.:

Sec. 1343_______________________________________ 4

Sec. 2281_______________________________________ 7

Alabama Constitution of 1901:

Article IV ; Sec. 50____________________________ 3, 4,49

Article I X _____________________________________ 5

Secs. 197-201______________________________ 3; 49

Secs. 198, 200______________________________ 16, 22

Sec. 200____________________________________ 0

Secs. 202, 203______________________________ 5,7

Article X V I I I ; Sec. 284___________________ 3 ,9, 15, 50

Alabama Keapportionment Act of 1962, Alabama

House Bill No. 59, Special Session, 1962 (Crawford-

Webb A ct)_______________________________________ 3

6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 30, 37, 38, 40, 42,’

46, 48, 54.

IV

U.S. Constitution—Continued

32 Alabama Code (1958) : Page

Secs. 1 and 2--------------- i --------------------------- 3,5,7,9,51

Miscellaneous:

House Bill No. 130, Special Session, 1962------------------- 17

Proposed Constitutional Amendment No. 1,1962, Ala

bama Senate Bill No. 29, Special Session, 1962 (“ 6 7 -

Senator Amendment” ) _ 3,11,12,16,17,18,19,20,30,31,52

J n the S u p rem e (jjtotrt rrf the ® n M jS taies

October T erm , 1963

No. 23

B. A . R eynolds, et al ., appellants

v.

M. 0 . S im s , et al .

No. 27

D avid J. V ann and R obert S, V ance, appellants

v.

A gnes B aggett, Secretary op S tate of the State of

A labama , et al .

No. 41

J ohn W . M cConnell, J r., et al., appellants

v.

A gnes B aggett, Secretary of S tate of th e S tate of

A labam a , et al .

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES D ISTRICT COURT FOR

THE M IDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAM A

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

(1)

2

O PIN ION S BELOW

The opinion of the three-judge district court (R.

137-167) is not yet reported. A prior opinion of the

three-judge district court (R. 62-65) is reported at

205 F. Supp. 245.

JU R ISD IC T IO N

The judgment of the three-judge district court was

entered on July 25, 1962 (R. 173). Notices of appeal

and cross-appeal to this Court were filed on August 17

and August 23, 1962, and probable jurisdiction was

noted on June 10,1963 (R. 197-200, 201-203, 204-205,.

206). The jurisdiction of this Court rests upon 28

U.S.C. 1253.

QUESTIONS PRE SEN TED

1. Whether the preexisting apportionment of both

houses of the Alabama legislature violates the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by

creating gross inequalities in per capita representation

without rhyme or reason.

2. Whether the district court properly held that the

plaintiffs’ constitutional rights would also be violated

by the apportionments provided by a proposed con

stitutional amendment, and by standby legislation

which was to take effect upon failure of the amend

ment.

3. Whether the district court abused its discretion

in ordering a temporary apportionment combining the

most equitable provisions of the proposed amendment

and the standby legislation, in order to allow the legis

lature to reapportion itself.

3

C O N STITU TION AL PROVISION S, STATU TES, AN D PROPOSED

C O N STITU TION AL A M E N D M E N T IN V O LV E D

Article IV, Section 50, of the 1901 Alabama Con

stitution is set forth in the Appendix, p. 49. Article

IX , Sections 197-201, of the 1901 Alabama Constitu

tion is set forth in the Appendix, pp. 49-50. Article

X V III, Section 284, of the 1901 Alabama Constitution

is set forth in the Appendix, pp. 50-51. Sections 1

and 2 of 32 Alabama Code (1958) are set forth in the

Appendix, pp. 51-52.

Proposed Constitutional Amendment Xo. 1 of 1962,

Alabama Senate Bill No. 29, Special Session, 1962

(the so-called “ 67-Senator Amendment” ), is set forth

in the Appendix, pp. 52-54. The Alabama Reappor

tionment Act of 1962, Alabam House Bill No. 59, Special

Session, 1962 (the “ Crawford-Webb Act” ) is set forth

in the Appendix, pp. 54-56.

IN T E R E ST OE T H E U N IT E D STATES

This is one of four cases pending argument on the

merits in which the Court will be called upon to

formulate under the Fourteenth Amendment the con

stitutional principles applicable to challenges to mal

apportionment of a State legislature. The United

States has filed its principal brief in Maryland Com

mittee for Fair Representation v. Tawes, No. 29, be

cause of an earlier due date. There we attempted to

present a compendious analysis applicable to all four

cases showing their relation to each other. The in

stant case raises specific problems in the application

of those principles.

4

ST A TE M E N T

1. The Complaint.—On August 26, 1961, the plain

tiffs (the appellees in No. 23)1—fourteen citizens and

taxpayers of the United States and of the State of

Alabama, who are residents and registered voters of

Jefferson County, Alabama—filed a complaint in the

United States District Court for the Middle District

of Alabama, in their own behalf and on behalf of all

voters of Alabama who are similarly situated, chal

lenging the apportionment of the Alabama legislature

(R. 1-39). The defendants (the appellants in No. 23),

who were sued in their representative capacities as

officials charged with the performance of duties in

connection with State elections, included the Secretary

of State and the Attorney General of Alabama ; the

Chairmen and Secretaries of the Alabama State Dem

ocratic Executive Committee and the Republican Exec

utive Committee; and three Judges of Probate of three

counties as representatives of all the probate judges

of Alabama (R, 1, 3-8). The complaint alleged depri

vation of rights under the Alabama Constitution and

under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, and asserted that the district court had

jurisdiction under the Civil Rights Act. 42 U.S.C. 1983

and 1988, as well as 28 U.S.C. 1343 (R. 2, 8-14).

The complaint stated that the Alabama legislature

consisted of a House of Representatives of 106 mem

bers and a Senate of 35 members.2 It set out (R. 13-

1 Two groups o f intervenor-plaintiffs (see p. 8 below) are

cross-appellants in Nos. 27 and 41.

2 Article IY , Section 50, of the Alabama Constitution (Appen

dix, p. 49) provides that the Legislature shall consist o f not

5

14; Appendix, pp. 49-50) relevant portions of Article

IX of the Alabama Constitution of 1901 which provide

that “ [t]he members of the House of Representatives

shall be apportioned by the legislature among the sev

eral counties of the state, according to the number of

inhabitants in them, respectively, as ascertained by

the decennial census of the United States * * *” ;

that the Senate districts “ shall be as nearly equal to

each other in the number of inhabitants as may be

* * that “ [representation in the Legislature shall

be based upon population, and such basis of represen

tation shall not be changed by constitutional amend

ments” ; that it is the duty of the legislature to reap

portion after each census; that each county (there are

now 67) is entitled to at least one member of the House

of Representatives; and that each Senate district shall

have only one member and no county may be divided

between two Senate districts (thereby placing a limit

of one Senator for any county).3

more than 35 senators and 105 representatives, except that, in

addition to the 105 members, each county thereafter created

shall be entitled to one representative. The House increased

by one member in 1903 when Houston County was created out

of Dale, Geneva and Henry Counties (E. 166). Houston

County was joined to Henry County to form the thirty-fifth

senatorial district, which up to 1903 consisted only of Henry

County (E. 17).

Article IX , Sections 202 and 203, of the Constitution, which

was based on the 1900 census, established the precise senatorial

and representative districts of the State until a new reappor-

tionment, was made by the legislature. Sections 202 and 203,

as modified by the creation of Houston County in 1903, were

enacted into the Alabama Code of 1907 and 1923, and were

re-enacted as 32 Alabama Code (1958) 1,2.

3 The cross-appellants in Xo. 27 (Br. 15—16) say that the

Alabama Constitution forbids the division o f a county only

709 - 522— 63 2

6

The complaint alleged that the last apportionment

of the Alabama Legislature was based on the 1900

federal census despite the requirement of the Alabama

Constitution that the legislature be reapportioned

every ten years; and that, since the population growth

of the various counties in the State from 1900 to 1960

had been uneven, Jefferson and other counties were

now victims of serious discrimination (R. 18-20, 35-

39). As a result of the failure of the legislature to

reapportion itself, plaintiffs asserted that they were

denied “ equal suffrage in free and equal elections

* * * and the equal protection of the laws” in viola

tion of the Alabama Constitution and the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution (R. 8-9).

Plaintiffs also claimed that they had no adequate

remedy at law, and that they had exhausted all forms

of relief other than that which might be available to

them through the federal courts. They asserted that

the legislature had established a pattern of conduct

from 1911 to the present time which “ clearly demon

strates that no reapportionment * * * shall be ef-

when one or both pieces will be joined with another county

to form a multi-county district, i.e., counties entitled by popu

lation to two or more senators can be split into the appropriate

number of districts. The argument is based on the fact that

prior to the Constitution of 1901, the Alabama Constitution so

provided. Appellants say that there is no reason to believe

that the 1901 Constitution was intended to effect any change.

However, this view seems contrary to the words of Article IX ,

Section 200, of the Alabama Constitution and to the practice

under it. The only apportionments under the 1901 Constitu

tion, the 1901 apportionment and the Crawford-Webb Act (see

pp. 11-12, 54—56 below), gave no more than one seat to a comity

even though by population several would have been entitled to

more.

7

fected” ; that representation at any future constitu

tional convention would be established by the legisla

ture, a fact which would make it “ extremely unlikely”

that the membership of any such constitutional con

vention would differ from that of the legislature; and

that, while the Alabama Supreme Court had ruled that

the legislature had not complied with the Alabama

Constitution, the court nevertheless held that it would

not interfere with the question of reapportionment4 (R.

.20- 21) .

Plaintiffs requested the convocation of a three-judge

district court under 28 U.S.C. 2281. They sought:

(1) a declaratory judgment that Article IX , Sections

202 and 203 of the Alabama Constitution and 32

Alabama Code 1, 2, which establish the present appor

tionment of the legislature, are unconstitutional under

the Alabama Constitution and the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment; (2) an injunction enjoining the defendants

from executing their duties in connection with elec

tions of the legislature until such time as the legisla

ture reapportions itself in accordance with the Ala

bama Constitution; (3) a mandatory injunction (until

such time as the legislature properly reapportions)

requiring the defendants to conduct the 1962 general

election at large over the whole State; and (4) any

.other relief which “may seem just, equitable and

proper” (R. 25-33).

4 Waid v. Pool, 255 Ala. 441, 51 So. 2d 869; E x parte Rice,

143 So. 2d 848 (Ala. Sup. C t.) ; Opinion of the Justices, 254

Ala. 185, 47 So. 2d 714; Opinion of the Justices, 263 Ala. 158,

81 So. 2d 881.

8

2. The Pre-decision Proceedings in the District

Court.—A three-judge district court was convened to

hear and determine the cause. Three groups of citi

zens, taxpayers and qualified voters of Alabama and

the Counties of Jefferson, Mobile, and Etowah, were

granted leave to intervene in the action as intervenor-

plaintiffs; two of the groups are cross-appellants in

Nos. 27 and 41 (R. 47, 65-66, 76-77). With minor

exceptions, all the intervenors adopted the allegations

and prayers of the plaintiffs’ amended complaint

(R. 46, 60-61, 69).

On March 29, 1962 (three days after this Court had

decided Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186), the plaintiffs

moved for a preliminary injunction requiring the

defendants to conduct at large the May 1962 Demo

cratic primary elections and the November 1962

general elections of the legislature (R. 47-50). The

motion was set for hearing by the three-judge court

in an order which stated the court’s tentative view

upon two points: (1) that an injunction was not

required before the primary elections of May 1962

to protect plaintiffs’ constitutional rights; and (2)

that no action should be taken by the court, which is

not “ absolutely essential” for the protection of as

serted constitutional rights, before the Alabama Legis

lature has had “ further reasonable but prompt oppor

tunity to comply with its duty” under the Alabama

Constitution (R. 57-59).

On April 14, 1962, the court, after reiterating the

views expressed in the order of March 30, 1962, re-set

the case for hearing on July 16 (R. 62-63). The

9

court noted that the importance of the case, together

with the necessity for effective action within a limited

period of time, required an early announcement of

its views. The court then indicated (1) that, under

Baker v. Carr, 369 TJ.S. 186, it had jurisdiction of

the cause, the complaint stated a justiciable cause

o f action, and the plaintiffs had standing to bring the

suit; (2) that it was taking judicial notice of facts

which were “well known” to the Justices of the

Supreme Court of Alabama and the people of Ala

bama—that there had been population changes in the

counties of Alabama since 1901, that the present

representation of the Alabama Legislature as pro

vided for in 32 Alabama Code 1 and 2 is not on a

population basis, and that the legislature had never

reapportioned its membership as required by the

Alabama Constitution; (3) that if the legislature

complied with the provision of the Alabama Consti

tution (Art, X V III, Sec. 284) that “Representation

in the legislature shall be based upon population,”

there could be no valid objection on federal constitu

tional grounds to any such apportionment and the

complaint in the instant case would be dismissed;

(4) that if the legislature failed to act, or its actions

did not meet constitutional standards, the court would

be under a “ clear duty” to take some action on the

matter before the general elections of November 1962

(action which it said should be kept to the minimum

necessary for the guaranteeing of constitutional rights

to Alabama citizens) ; (5) that, to such an end, the

“ present thinking” of the court was for adherence to

10

the plan suggested by Mr. Justice Clark in his con

curring opinion in Baker v. Carr—that is, awarding-

seats released by the consolidation or revamping of

existing districts to counties suffering the most

“ egregious discrimination,” thereby releasing the

stranglehold on the legislature sufficient to permit it

to reapportion itself; and (6) that, while retaining

jurisdiction, the court would defer further action in

the case until the newly elected legislature had “ full

opportunity” to reapportion itself, which would permit

the dismissal of the case (R. 62-65).

On July 2, 1962, Judge Johnson permitted the

plaintiffs to amend their complaint to add a further

prayer for relief (R. 76). The plaintiffs requested

that, since the legislature (-which was assembled in

special session) “ appears to be giving no serious con

sideration to any act reapportioning the House o f

Representatives and redistricting the Senate * * *“

on a population basis prior to the November, 1962,

general election” in accordance with the court’s opin

ion of April 14, 1962, the court provisionally reap

portion the House of Representatives and the Senate.,

The plaintiffs asked that the court consolidate exist

ing election districts and distribute the seats thus re

leased to those counties suffering the most “ egregious;

discrimination” so that the stranglehold on the legis

lature would be relaxed enough to permit it to reap

portion its membership. The plaintiffs then sug

gested that the court defer further action until the-

newly elected legislature had full opportunity to reap

portion its membership in accordance with the Ala

11

bama Constitution; and that the court enjoin the de

fendants from performing their election duties except

in accordance with the provisional plan of reappor

tionment (ft. 69-70).5 6

On July 12, 1962, an extraordinary session of the

Alabama Legislature advanced two reapportionment

plans to take effect in 1966. One was a proposed

constitutional amendment, called the “ 67-Senator

Amendment” (see Appendix, pp. 52-54). It provided

for a House of Representatives consisting of 106 mem

bers apportioned by giving one seat to each of the 67

counties and distributing the others according to popu

lation by the “ equal proportions” method. Using this

formula, the constitutional amendment specified the

number of representatives for each county until a new

apportionment could be made on the basis of the 1970

census. The Senate would be composed of 67 mem

bers, one from each county. The act provided that

the proposed amendment should be submitted to the

voters for ratification at the general election of No

vember 1962.

The “ Crawford-Webb Act” (see Appendix, pp. 54-

56), was enacted as standby legislation to take effect

in 1966 if the proposed constitutional amendment

should fail." The act provides that the Senate should

0 Interveners Vann and Vance (cross-appellants in No. 27)

had previously asked for similar relief (E. 60-61).

6 The Act itself merely says that it will take effect in 1966.

However, the proposed constitutional amendment also provides

that it will take effect in 1966. The amendment would take

precedence if it was adopted by the voters and not held uncon

stitutional. As the district court stated, the Act is a stand-by

12

consist of 35 members representing 35 senatorial dis

tricts, established along county lines. The act altered

10 out of the former 35 districts (compare R. 35-36

with Appendix, pp. 54—55). As for the House of

Representatives, the statute apportions the represent

atives among the counties as follows: Jefferson, 12 mem

bers ; Mobile, 6 members; Montgomery, 4 members; Cal

houn, Etowah, Madison, and Tuscaloosa, 3 member's

each; Baldwin, Colbert, Cullman, Dallas, Houston,

Lauderdale, Lee, Marshall, Morgan, Russell, Talla

dega, and Walker, 2 members each; and all the re

maining counties, 1 member each (R. 113, 161).7 The

Crawford-Webb Act also provides that it shall be

effective “ until the legislature is reapportioned ac

cording to law,” but it provides no standard for such

a reapportionment.8 * * * 12

measure designed to take effect in the event that the voters

rejected the “ 67-Senator Amendment" or the federal courts re

fused to accept the proposed amendment as effective action com

plying with the Fourteenth Amendment (see E. 143-144).

7 While no formula for this apportionment is stated, one can

be extrapolated (see the Brief for Appellants, B. A. Eeynolds,

et al., p. 39) : each county with less than 45,000 people

receives one representative; counties with 45,000 to 90,000 peo

ple, 2 seats; counties with 90,000 to 150,000 people, 3 seats;

counties 150,000 to 300,000 people, 4 seats; counties with 300,-

000 to 600,000 people, 6 seats; counties with over 600,000 people,

12 seats.

s Presumably, future apportionments would be based on the

existing provisions of the Alabama Constitution which the

statute, unlike the proposed constitutional amendment, would

not effect. The State constitutional provisions are plainly in

consistent with the statute’s apportionment of both houses.

13

3. The Evidence.—The basic facts consist of two sets

of incontrovertible figures: (1) the population for

each county in Alabama and for each senatorial dis

trict according to the 1960 census; (2) the number

of representatives apportioned to each county under

each of the plans at issue—the apportionment under

the 1901 statute, the proposed constitutional amend

ment, and the Crawford-Webb Act. Under all three

plans, each senate district would be represented by one

senator. Convenient compilations of these figures are

found at R. 35-39 and are also attached as appendices

to the opinion of the district court (R. 163-167).

4. The Decision and Decree of the District Court.—

On July 21, 1962, the district court, relying on Baker

v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, held that it had jurisdiction over

the cause; that the complaint alleged a justiciable

cause of action; and that the plaintiffs had standing

to challenge the Alabama apportionment statutes (R.

140-141). The court then ruled that the existing in

equality in representation in Alabama was the result

of “ invidious discrimination” in violation of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, a

finding which the court noted had been “ generally

conceded” by the parties to the litigation (R. 144).

. “ Jefferson (634,864), Mobile (314,301), Montgomery (169,-

210), Etowah and St. Clair (122,368), Madison, (117,348), Tus

caloosa (109,047), Baldwin,' Escambia, and Monroe (104,971),

and Lauderdale and Limestone (98,135) (R. 35-36, 166).

709 - 522— 63— — 3

14

In support of this conclusion, the court referred to

appendices to its opinion (R. 163-165) which showed

that the growth and shifts in population between

1901 and 1960 had converted the preexisting popula

tion into a crazy-quilt utterly lacking rhyme or reason.

The court then considered the proposed constitu

tional amendment and the Crawford-Webb Act to

ascertain whether the legislature had taken “ effective

action” to remedy the unconstitutionality of the exist

ing apportionment (R. 146). The apportionment of

one Senator to each county under the proposed con

stitutional amendment, the court held, would be “ even

more invidious than at present” because (1) the

present control of the Senate by 25.1 percent of the

people of Alabama would be reduced to 19.4 percent;

(2) the 34 smallest counties, whose total population

is less than that of Jefferson County, would have a

majority of the total membership of the Senate; and

(3) senators elected by 14 percent of the population of

Alabama could prevent the submission of any future

proposal to amend the State constitution (R. 148).

The court noted that the “ only conceivable rationali

zation” of the senatorial provisions is that it is based

on political units within the State and is analogous to

the United States Senate, but it rejected the analogy

on the ground that the Alabama counties are merely

involuntary political divisions of the State created by

15

statute to aid in the administration of government

(R. 148-149).10 The court also concluded that the

proposed apportionment of the House of Representa

tives—one representative for each of the 67 counties

with the remaining 39 distributed according to popu

lation—was “ based upon reason, with a rational re

gard for known and accepted standards of apportion

ment” (R. 153).

Turning next to the Crawford-Webb Act, the district

court held that an apportionment of the House of

-Representatives giving additional seats to the popu

lous counties in diminishing ratio to their population

(i.e., 3 for 90,000 to 150,000 people and 4 for 150,000

to 300,000) was “ totally unacceptable” (R. 152).

Each representative from Jefferson and Mobile Coun

ties would represent over 52,000 citizens while repre

sentatives from eight “ Black Belt” counties would

each represent less than 20,000 citizens (R. 153).

The court regarded the apportionment of the Senate

provided in the Crawford-Webb Act as but a “ slight

10 The court also noted that the proposal “ may not have complied

with the State Constitution” since not only does Article X V III ,

Section 284, of the Alabama Constitution provide that the popula

tion basis of the Legislature “ shall not be changed by constitutional

amendments” but the Alabama Supreme Court had earlier indi

cated that Section 284 could be altered only by constitutional

convention (R. 147-148). See Opinion o f the Justices, 254 Ala.

185, 47 So. 2d 714; Opinion o f the Justices, 263 Ala. 158, 81

So. 2d 881.

16

improvement over the present system of representa

tion” since the net effect of switching a few seats

from the less populous - to more populous counties

would merely increase the minority electing a ma

jority of the Senate from 25.1 percent to 27.6 percent

of the population (R. 152). The court pointed out

that the vote of a citizen in the senatorial district

consisting of Bibb and Perry Counties would be worth

twenty times that of a eitizen in Jefferson County;

that the vote of a citizen in the six smallest districts

would be worth fifteen or more times that of a citizen

in Jefferson County; and that, in twenty-two districts,

a citizen would have eight or more times the voting

strength of a citizen in Jefferson County (R. 152).

The court then held that the Crawford-Webb Act was

“ totally unacceptable” as a “ piece of permanent leg

islation” which, under the Alabama Constitution (Art.

IX , Sec. 198, 200), would remain in effect without

alteration until the next decennial census (R. 154).

The district court then adopted as a provisional re

apportionment the provisions relating to the House

contained in the “ 67-Senator Amendment”—one seat

for each county with the other 39 distributed accord

ing to population—and the provisions of the Craw-

ford-Webb Act relating to the Senate (R. 154). The

court retained jurisdiction and deferred any hearing

on the plaintiffs’ motion for a permanent injunction

“ until the Legislature, as provisionally reappor

tioned * * *, has an opportunity to provide for a true

reapportionment of both Houses of the Alabama

Legislature” (R. 155-156). The court emphasized

17

that its “ moderate” action was designed to break the

stranglehold on the legislature and would not suffice

as permanent reapportionment (R. 156).

On July 25, 1962, a decree was entered in accord

ance with the foregoing rulings (R. 173-191).

After the district court’s decision, new primary

elections were held pursuant to House Bill No. 130,

Special Session, 1962, which was passed at the same

session as the proposed constitutional amendment and

the Crawford-Webb Act, to be effective in case the

district court itself ordered reapportionment. The

general elections in November 1962 were likewise

held on the basis of the court’s apportionment. Con

sequently, the present Alabama legislature is appor

tioned according to the district court’s decree.

Appeals to this Court were noted by the defendants

(appellants in No. 23) and by two groups of plain

tiff-intervenors (cross-appellants in Nos. 27 and 41)

(R. 197-205).

AR G U M E N T

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

The initial question is whether the apportionment

existing in Alabama prior to the district court’s de

cision—the apportionment provided by the 1901 legis

lation-violated the plaintiff’s rights under the Four

teenth Amendment. That was not only the

apportionment in effect when the bill was filed but

even on the date of the district court’s decision the

election officials were obliged to follow it unless pre

vented by the court. Furthermore, it is far from

clear that either the “ 67-Senator Amendment” or

18

the Crawford-Webb Act has become effective as a

matter of State law. The amendment has not been

submitted to the voters. The Crawford-Webb Act

was apparently intended to take effect in 1966 only if the

proposed amendment was rejected by the people

or held unconstitutional in a final adjudication.

We submit, for reasons stated below in more detail,

that the preexisting apportionment is plainly uncon

stitutional as applied today whatever its validity

when enacted in 1901. During the 60-year interval

the passage of time and shifts in the distribution of

population made the apportionment into a crazy-

quilt. The resulting gross inequalities violate the

equal protection clause. That proposition is plainly

implied in the opinions of the prevailing Justices in

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, and is supported by a host

of subsequent decisions in the lower courts.

It is unnecessary to decide whether either the

“ 67-Senator Amendment” or the Crawford-Webb

Act was properly before the district court on the

merits. The proposed amendment, not having been

ratified, has never become effective, and whether the

Crawford-Webb Act actually came into force may be

debatable as a matter of Alabama law. The question

need not be decided because both measures had to be

considered in formulating a remedy for the vindica

tion of the constitutional rights which defendants

were threatening to violate by adhering to the 1901

apportionment in the November election.

19

Having found tlie preexisting apportionment un

constitutional, the district court was required to pro

vide an effective remedy. Legislative apportionment,

however, is primarily a matter for the State legis

latures, both because it is a State problem, within the

confines of the Fourteenth Amendment, and because

it involves the exercise of a wide range of legislative

choice. I f the legislature has plainly set forth its

preference as to a substitute apportionment that satis

fies the requirements of due process and equal pro

tection, it would be an error of law to disregard the

legislature’s action in favor of a judicial apportion

ment framed by the court. Compare Sob el v. Adams,

208 F. Supp. 316, 319-322 (S.D. Fla.) ; Toombs v.

Fortson, U.S.D.C., N.D. Ga., decided September 5,

1962 (passing on both proposed constitutional amend

ment and proposed statutes); Moss v. Burkhart,

U.S.H.C., W.D. Okla., decided July 17, 1963 (passing

on proposed statute, but declining, because it was

unlikely to be adopted, to pass on proposed con

stitutional amendment except to say that it was of

doubtful constitutionality) d1

The “ 67-Senator Amendment” set forth the Ala

bama legislature’s preference with respect to future 11

11 There was considerably less warrant to consider the con

stitutionality o f the constitutional amendments and statutes in

the cases cited above than in this case. In those cases, the

constitutional amendment might be rejected by the people or

the statutes not passed by the legislature. Here, unless a new

constitutional amendment or statute is adoped in the meantime,

either the “ 67-Senator Amendment” or the Crawford-Webb Act

would, according to their terms, be effective in 1966.

20

apportionment, even though it had not yet been

ratified. The Crawford-Webb Act was adopted by

the legislature as an alternative. Only if both were

unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment

could the district court properly proceed to frame

an interim judicial apportionment to be effective pend

ing further legislative action.

In the second part of our Argument, therefore, we

address ourselves to the apportionment proposed in

the “67-—Senator Amendment” and show that although

it is not a crazy-quilt, being based upon intelligible

principles, it is nonetheless unconstitutional because

the principle of popular representation has been sub

ordinated to the representation of political subdivi

sions to such an extent as to create very gross in

equalities in per capita representation and give con

trol of both branches of the legislature to small

minorities of the people. The controlling legal prin

ciple is stated as the fourth proposition in our Mary

land brief in the general analysis of the standards to

be applied in implementing Baker v. Carr (pp. 46-50)

and is elaborated there as applied to the Maryland

apportionment (pp. 57-90). In our view, the instant

case is indistinguishable. Not only are the populous

counties grossly underrepresented in the Alabama

legislature in comparison with other comities but

senators representing as few as 19.4 percent of the

people would constitute a majority of the Senate while

representatives chosen by no more than 42.4 percent can

control the House of Representatives.

In Point III, we take up the Crawford-Webb Act

and show that it violates the same principle for essen-

21

tially the same reasons: the inequalities in per capita

representation are no less gross; 27.6 percent of

the people could control the Senate and 37 percent,

the House. In addition, the inequalities in the pro

posed representation in the Senate defy rational

explanation.

Finally, we turn to the issue raised by the cross

appellants—whether the district court erred in not

requiring both houses of the Alabama legislature to

be apportioned strictly on the basis of population.

It is essential, in this field, for the courts to give the

legislatures as much opportunity as possible, con

sistent with protecting basic constitutional rights, to

make their own apportionments since this is primarily

a State and legislative responsibility. In our view

the district court properly gave the Alabama legisla

ture time to act. When the legislature took inadequate

action, it was proper to adhere as closely as prac

ticable to the apportionments approved by the repre

sentatives of the people of Alabama, provided that this

course offered reasonable hope that minority control

would be broken sufficiently to result in an early

legislative apportionment recognizing plaintiffs’ con

stitutional rights. I f the hope proves vain, the dis

trict court can provide a more complete remedy, for

it recognized that its decree was only an interim

measure and retained jurisdiction to grant further

relief if necessarj ̂ to secure the plaintiffs their full

constitutional rights.12

12 For the above reasons, we find it no more appropriate here

than in the companion cases to consider whether substantially

equal representation per capita is required by the Fourteentla

Amendment in both branches of a State legislature.

7 0 9 —5 2 2 — 6 3 - ■4

22

I

THE PRE-EXISTING APPORTIONMENT OE THE ALABAMA

LEGISLATURE VIOLATED THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE

BECAUSE IT CREATED GROSS INEQUALITIES IN PER CAPITA

REPRESENTATION WITHOUT RHYME OR REASON

The legislative apportionment in effect in Alabama

prior to the institution of the present action illus

trates the causes of the kind of gross malapportion

ment that prevailed in a number of States prior to the

decision in Baker v. Carr. The apportionment act

was enacted in 1901. It was based on the Alabama

Constitution which provides that the Senate shall be

apportioned according to population, except that no

county may have more than one senator,13 and that

the House of Representatives shall be apportioned by

giving one seat to each county with the remaining 39

distributed according to population. Article IX , See.

198, 200 (Appendix, pp. 49, 50). While these rules

allowed 41 percent of the people to elect a majority of

the Senate and 44 percent to elect a majority of the

House even in 1901, the inequalities were at least the

result of an intelligible system, whether or not it

might be unconstitutional upon some other ground.

13 The limitation to one senator for a county results from

provisions that no county may be divided in forming senatorial

districts and no district may have more than one senator.

Art. IX , Sec. 200 (App., p. 50). It would seem that the pro

hibition against dividing a county between districts might

well have been read to prohibit splitting off parts of a county

for combination with another county without preventing divi

sion of a county into two or more whole districts; but the

State s own interpretation is to the contrary and is plainly

controlling.

23

Since 1901, Alabama, like most States, has experi

enced both growth and change in the distribution of

population. Instead of 1,828,697 people, there are

now 3,266,740, an increase of 78 percent (R. 39).

Twenty-four of the 67 counties have lost population

(R. 37-39) and others have grown at different rates.

Mobile County has grown over five times from 62,740

to 314,301 (R. 38). Meanwhile the legislature failed

to comply with the mandate of the State constitu

tion requiring decennial reapportionment. The re

sult is that the apportionment became a crazy-quilt and

25.1 percent, instead of 41 percent of the people be

came able to elect a majority of the Senate (R. 148),

and 25.7 percent, instead of 44 percent, could elect a

majority of the House of Representatives.

The gross discrimination that exists today in per

capita representation is not simply the result of

the limitation of one senator to any one county or

the minimum of one representative for each county.

Those inequalities have at least an intelligible basis.

In contrast, the discrimination resulting from shifts

in population has no justification. Such discrimina

tion is plainly unconstitutional under familiar princi

ples. “ The Constitution in enjoining the equal pro

tection of the laws upon States precludes irrational

discrimination as between persons or groups of per

sons in the incidence of a law.” Goesaert v. Cleary,

335 U.S. 464, 466.

In the House of Representatives, Barbour County

had 35,142 people in 1901, over twice the average pop

ulation per representative in the State, and therefore

24

was assigned two representatives. Bullock County

had 31,944 people and likewise had two representa

tives. Baldwin County then had only 13,194 people

and therefore only one representative. Today Bar

bour has only 24,700 people, an average of 12,350 per

representative,14 and Bullock County has only 13,462

people, or 6,731 per representative, but the popula

tion of Baldwin County has grown to 49,088. Thus,

Barbour has half the population of Baldwin, and Bul

lock has about 4̂, but both have twice the representation

of Baldwin. Conversely, the voters in Barbour have

four times and voters in Bullock have iy 2 times, the

representation of voters in Baldwin.15

In 1901, Dallas County had 54,657 people and three

representatives, i.e., 18,219 per representative. Etowah

then had 27,361 and two representatives, or one for each

13,681. Mobile County, in 1901, had 62,740 and three

representatives, an average of 20,913 per representative.

And Montgomery County had 72,047 people and four

representatives, an average of 18,012 per representa

tive. As of 1960, Dallas’ population had risen merely

to 56,667 or 18,889 per representative. Etowah and

Mobile Counties’ popidation, however, had soared to

96,980 and 314,301 so that they now have 48,490 and

104,767 people per representative, respectively. Mont

gomery’s population is now 169,210 or 42,303 per rep

resentative. Thus, Dallas has three representatives

14 In our brief in the Maryland case, we mistakenly said that

Barbour County has only 12,350 people.

15 The population figures in this paragraph, as well as most of

those in the remainder of this brief, are taken from the tables in

the record at pp. 35-39.

25

while Etowah has two, although Etowah has over 70

percent more people. Voters in Dallas County have

well over 2 ^ times the representation of those in

Etowah. Similarly, Dallas and Mobile have the same

number of representatives although Mobile has almost

six times as many people. This means that voters in

Dallas County have almost six times the representa

tion of those in Mobile. In addition, Mobile, while

having almost twice the population of Montgomery

County, has one less representative. As a conse

quence, voters in Montgomery County have over 2%

times the representation of those in Mobile (although

less than half the representation of those in Dallas

County). And voters in Bullock County have almost

16 times the representation of those in Mobile.

Finally, the most populous county in the State,

Jefferson County, has grown from 140,420 in 1901 to

634,864. Its seven representatives represent an aver

age of 90,695 today as compared to 20,060 in 1901.

As a result, voters in Jefferson County have less than

Yis the representation of those in Bullock County and

about y5 the representation of those in Dallas County.

These examples could easily be multiplied. It is

sufficient to say that, applying Alabama’s own Con

stitution—which gives one seat to each county and

distributes the rest according to population—15 of the

30 counties with more than one seat16 are overrepre

sented and six are underrepresented; thus, the vice

affects 70 percent. Moreover, the two largest coun

16 The discrimination in favor of counties with one seat is,

at least in part, because of the guarantee of one seat to each

county provided by the Alabama Constitution.

26

ties have been deprived, without justification, of over

half their representation: Jefferson has only 7 seats

instead of the 17 to which it would be entitled by the

formula in the State constitution, and Mobile has only

3 instead of 8. While we are of course not arguing

that the violation of the State constitution constitutes

a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, the State

here offers no explanation for these deviations from

its own standard.

The discrimination is equally egregious in the Sen

ate. Wilcox County, which in 1901 had 35,631 people,

now has only 18,739. Yet, it has a representative all

to itself. Bordering Wilcox County, is a district

composed of Monroe, Baldwin, and Escambia Coun

ties, which is the second most populous multi-county

district in the State.17 Whereas, those three counties

had only 48,180 people in 1901, they now have 104,971.

Consequently, voters in Wilcox County have over 5y2

times the representation of those in the adjoining

district. The arbitrariness of this discrimination is

plain since the two districts could be made substan

tially more equal by either placing Monroe (with 22,-

372 people) in the same district as Wilcox or joining

both Escambia County (with a population of 33,511)

and Monroe with Wilcox.

Wilcox also adjoins Lowndes Comity. That coun

ty, which had 35,651 people in 1901, now has 15,417

and is the least populous senatorial district in the

17 The more populous single-county districts result from the

provisions in the Alabama Constitution limiting a county to only

one senator and not from shifts of population since 1901.

27

State. Bordering both Wilcox and Lowndes Counties

is the district composed of Butler, Conecuh, and Cov

ington Counties which in 1901 had 58,621 people, but

now has 77,953. The people in this district thus have

only Vs the representation of those in Lowndes County.

The transfer of Butler (with a population of 24,560)

to the same district as Wilcox would make the two

districts almost equal in population. Or, if Wilcox

and Lowndes Counties were joined, the result

ing district would still be one of the smallest in the

State. The extra seat could be used, for example, to

give Lee and Russell Counties with a total popula

tion of 96,105 a senator each. The resulting districts

would have 49,754 and 46,351 people, respectively.

To take one last example, Barbour County, which

had 35,152 people in 1901 but has only 24,700 today,

has a senator to itself. The adjoining district, con

sisting of Lee and Russell Counties, now has 96,105

people in comparison to the 58,909 it had in 1901.

Thus, voters in Barbour County have Sy2 times the

voting strength of those in the multi-county district.

This discrepancy could be largely eliminated by a

series of changes which would include joining Bar

bour to a neighboring county.

Much of the discrimination in the Senate results

from the requirement of the Alabama Constitution

which allows a county only one seat. Thus, Jefferson

County with 634,864 people would be discriminated

against even if the provisions in the State constitution

wTere faithfully applied on the basis of present popu

lation. However, the disparities in representation

28

between populous counties like Jefferson and the most

overrepresented counties is in part the result of the

failure of the legislature to reapportion because small

districts like Lowndes should be joined to neighbor

ing districts. As a result, while voters in Lowndes

County now have over 41 times the voting strength of

those in Jefferson, this could be reduced by over half.

Moreover, other slightly less populous comities are the

victims of gross discrimination because they are joined

to other counties. Etowah County has 96,980 people

and yet is joined together with St. Clair, to form a

senatorial district having a population of 122,368. This

district is the most populous multi-county district in

the State; indeed, there are only two other multi

county districts more populous than Etowah County

alone. Such discrimination is utterly without justi

fication.

An apportionment that imposes such capricious

inequalities upon the people m per capita representa

tion in the legislature plainly violates the Fourteenth

Amendment. The equal protection clause safeguards

the right to participate in the processes of self-govern

ment. See our Maryland brief pp. 28-29. “ [I ]t has

been open to the courts since the enactment of the

Fourteenth Amendment to determine, if on the par

ticular facts they must, that a discrimination reflects

no policy, but simply arbitrary and capricious action”

{Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 226).

The inequalities in Alabama’s preexisting appor

tionment are a consequence of legislative inaction.

They have no apparent basis in policy. Appellees

29

suggest none; on the contrary, in the district court

it was virtually agreed “ by all the parties that the

present apportionment of both Houses of the Legis

lature of the State of Alabama constitutes ‘invidious

discrimination’ in violation of the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment” (R. 144).

With sufficient ingenuity and willingness to overlook

rough edges, one might possibly conceive a policy or

combination of policies that would explain the dis

crimination. No such process of rationalization

should be supplied in dealing with the basic demo

cratic right to fair representation, especially where

the inequalities result from failure to comply with

the State’s own constitution. Even in the field of eco

nomic regulation, “ [discriminations are not to be sup

ported by mere fanciful conjecture.” Hartford

Steam Boiler Ins. Co. v. Harrison, 301 U.S. 459, 462;

Borden’s Farm Products Co. v. Baldwin, 293 U.S.

194, 209.

The district court was therefore correct in holding

that the preexisting Alabama apportionment violated

plaintiffs’ constitutional rights. Accord, Baker v.

Carr, 206 P. Supp. 341, 346-348 (M.D. Tenn.);

Toombs v. Fortson, 205 E. Supp. 248, 254-255, 256

(N.D. Ga.) ; Sobel v. Adams, 208 E. Supp. 316, 323-

324 (S.D. Fla.) ; Thigpen v. Meyers, 211 E. Supp. 826,

831 (W.D. Wash.), pending on appeal, No. 381, this

Term; Sincock v. Duffy, 215 E. Supp. 169, 184 (D.

Del.), pending on appeal sub nom. Roman v. Sincock,

No. 307, this Term; Mann v. Davis, 213 E. Supp. 577,

584 (E.D. Ya.), pending on appeal, No. 69, this Term;

30

Moss v. Burkhart, U.S.D.C., W.D. Okla., decided July

17) 1963; Sweeney v. Notte, 183 A. 2d 296, 305 (R.I.

Sup. Ct.).

I I

THE APPORTIONMENT PROVIDED BY THE PROPOSED CON

STITUTIONAL AMENDMENT WOULD VIOLATE THE EQUAL

PROTECTION CLAUSE BY SUBORDINATING POPULAR REP

RESENTATION TO THE REPRESENTATION OF POLITICAL

SUBDIVISIONS TO SUCH A DEGREE AS TO CREATE GROSS

INEQUALITIES AMONG VOTERS AND GIVE CONTROL OF

BOTH HOUSES OF THE LEGISLATURE TO SMALL MINORI

TIES OF THE PEOPLE 18

Alabama s 67 Senator Amendment” is not subject

to attack as creating a crazy-quilt of unequal repre

sentation based upon no intelligible rule. Seats in the

Senate would be apportioned one to each county.

Sixty-seven seats in the House would go one to each

county, but the remaining 37 seats would be distributed

among the counties as nearly as possible in proportion

to population. The apportionment is apparently

based upon a principle of corporate representation

through equal political subdivisions combined, in the

lower chamber, with the principle of direct popular

representation. The “ 67—Senator Amendment” rests

upon the same basis as the Maryland apportionment

involved in No. 29 (disregarding the special provisions

relating to the City of Baltimore).

The reasons for concluding that the court below properly

ruled upon the constitutionality of the “ 67— Senator Amend

ment and the Crawford-Webb Act are discussed in the Intro

duction and Summary, pp. 19-20, supra.

31

Although the Fourteenth Amendment condemns an

apportionment which creates capricious inequalities

in per capita representation without rhyme or reason,

a showing that seats are allocated according to some

intelligible rule is not sufficient per se to satisfy the

guarantee of equal protection. The rule of classifi

cation may not violate another specific constitutional

policy or introduce differentiations that are invidious

or irrelevant to any tolerable purpose of govern

mental organization. More important here is the nec

essity of weighing the degree of inequality against the

policies that the per capita discrimination seeks to

secure. Objectives that might furnish acceptable jus

tification for smaller variations 19 become so relatively

insignificant as to leave the discrimination arbitrary

and capricious where there are grosser inequalities

in representation and a total disregard for the prin

ciple of majority rule. We submit that the “ 67-

Senator Amendment,” like the Maryland apportion

ment at issue in No. 29 where we discuss the appli

cable principles at greater length, violates the equal

protection clause by subordinating popular represen

tation to the representation of political subdivisions

to such a degree as to create gross inequalities and 10

10 Since the instant case, like the three companion cases, can

be decided without ruling upon whether the Fourteenth

Amendment requires substantially equal representation per

capita in both houses of a State legislature, we assume here, as

we have in those cases that there may be permissible objectives

of legislative apportionment that would justify some departure

from equality per capita. The assumption is made arguendo,

reserving further judgment until the issues are presented.

32

give control of the legislature to representatives

elected by small minorities of the people.

The facts of discrimination and resulting minority

control are readily demonstrated. Appendix D to the

opinion of the district court shows the wide varia

tions in population among the 67 counties. Since

each county would have one senator, there would be

equally great inequalities in per capita representa

tion. The disparity between the most overrepresented

district (Coosa Comity) and the most underrepre

sented (Jefferson County) would be more than 59 to

1 . There are five counties with a population in ex

cess of 105,000 and eight with a population of less

than 15,000; between any pair drawn from both classes

the discrimination would be at least 7 to 1. The nine

most populous counties (Jefferson, Mobile, Madison,

Montgomery, Tuscaloosa, Etowah, Calhoun, Talladega

and Dallas) which hold 50.8 percent of the population,

would elect only nine of the 67 senators, or 13.4 per

cent—one-fourth their aliquot share.

In the House the inequalities and resulting minor

ity control would be less objectionable but still gross.

The disparity between the most overrepresented

county (Coosa) and the most underrepresented

(Houston) would be almost 5 to 1. The nine most

populous counties, with 50.8 percent of the popula

tion, would have only 45 out of 106 seats, or 42.4

percent.

The discrimination in both houses runs in favor of

the same relatively unpopulous counties and against

the more populous; thus, the inequality in one house

33

adds to the severity o f the discrimination in the other.

I f one house of a State legislature is apportioned

substantially in accordance with population, there may

be room for variation in the other,20 but surely there

can be no justification for substantial discrimination

against the same people in their per capita represen

tation in both houses. In this respect there is no sig

nificant difference between the Maryland case and the

present aspect of the instant controversy. Having

fully presented our argument there (pp. 29-34, 43-50,

57-90), we content ourselves here with a summary.

The principles of voter equality and majority rule

are too vital a part of our constitutional heritage to

suppose that the Fourteenth Amendment permits the

States to submerge them in the interest of recognizing

equality of political subdivisions, either for its own

sake or because of the collateral consequences. The

founding fathers firmly believed that the State legis

latures should be apportioned according to population.

At the Philadelphia Convention and also in the State

conventions which ratified the Constitution there was

general agreement that any legislature operating di

rectly on the people should, as a matter of funda

mental fairness, be apportioned in both houses accord

ing to population. See Appendix B to our Maryland

brief. Constitutional practice has also favored the

principle, for although a number of State constitu

tions have always called for limiting the principle by

some recognition of political subdivisions or a limita

20 Here, as in the Maryland case, we make this assumption

arguendo because no decision upon the question is required.

34

tion upon the representation of a few densely popu

lated areas, the formal rules did not then create the

grave injustices, gross inequalities and rule by small

minorities that they yield in Maryland and Alabama

today. “ The conception of political equality from the

Declaration of Independence to Lincoln’s Gettysburg

Address to the Fifteenth, Seventeenth and Nineteenth

Amendments can mean only one thing—one person,

one vote” ( Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368, 381). The

meaning cannot be altogether different in legislative

representation.

Altogether the Court has had few cases involving

the right to fair representation, its decisions under

the equal protection clause in other fields make it plain

that strong justification is required for any legislative

classification affecting fundamental rights. For exam

ple, in Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535, 541, the

Court, noting that procreation is “ one of the basic

civil rights of man,” held that “ strict scrutiny of the

classification which a State makes in a sterilization

law is essential, lest unwittingly or otherwise, invidi

ous discriminations are made against groups or types

of individuals in violation of the constitutional guar

anty of just and equal laws.” Earlier, in Yick Wo. v.

Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 370, the Court made clear that

voting “ is regarded as a fundamental political right,

because preservative of all rights.”

The reason for the rule is also applicable. Dis

crimination in legislative representation, as the recent

history of Alabama indicates, prevents effective resort

to the political process which can ordinarily be expect

35

ed to bring about the repeal of unjust legislation.

Cf. United States v. Carotene Products Co., 304 U.S.

144, 152, Note 4.

Appellants in No. 23 suggest (Br. 14) that the “ 67-

Senator Amendment” is constitutional by analogy to

the United States Congress. However, for reasons

argued in our brief in the Maryland case (pp. 7 3 -

82), there is no federal analogy to the State legisla

tures. The Congress reflects the mixed nature of the

federal government; the House of Representatives

reflects its national aspect with the States in a sub

ordinate role, the Senate reflects the continued sov

ereignty and equality of the States. As the framers

recognized, the State governments are no such mix

ture; they operate directly on the people. The coun

ties of Alabama are mere subdivisions of the State,

created by the State to carry out the functions which

the State chooses to assign to them. E.g., Askew v.

Ilale County, 54 Ala. 639, 641; State v. Butler, 225

Ala. 191, 193, 142 So. 531; Moore v. Walker Comity,

236 Ala. 6 88, 690,185 So. 175.

The federal analogy does not apply for an addi

tional reason. The very most the federal analogy could

be supposed to show is that the upper house may deviate

substantially from equality on the basis of population if

the lower house is apportioned fairly. The federal

House of Representatives is, in effect, apportioned by

the Constitution among the States almost exactly in con

formance with population. While each State is guar

anteed at least one representative, only four States

have less than 1435 of the population. Thus, it

36

takes representatives from States with almost 50 per

cent of the population to constitute a majority of the

House.21 In contrast, only 42.4 percent of the people

of Alabama live in counties electing over half the

State House of Representatives. Forty of the 67

counties have less than Vio6 of the State popula

tion. Thus, the federal analogy cannot apply, even

assuming its underlying validity, because Alabama’s

proposed constitutional amendment does not require

that either house be apportioned substantially on the

basis of population.

Appellants in No. 23 also contend (Br. 36-37) that

apportionment of the Senate in the proposed consti

tutional amendment is justified as preventing domina

tion of the legislature by a few populous cities. I f

this means that Alabama simply prefers rural voters

over urban, the preference plainly constitutes in

vidious discrimination against the populous counties

As we discuss fully in our Maryland (pp. 39-46) and

New York (pp. 14-33) briefs, it is as much a denial

of equal protection for a State to give voters who live

in populous counties less representation than other

voters as it would be to prefer or discriminate against

counties with a certain percentage of Protestants,

Catholics, Negroes or businessmen. Appellants’ ar

gument also fails on the facts. As they acknowledge

21 Unfair districting within the States, however, by the State

legislatures, has resulted in having a majority of representa

tives elected from districts having only 42 percent of the popu

lation. Such unfair districting is probably unconstitutional.

See the government’s brief in Western/ v. Sanders, No. 22, this

Term, pp. 30-35.

37

(Br. 52), it takes a minimum of ten counties to make

up 52 percent of the State’s population. Rule by ten

counties scattered over different parts of the State

can hardly be described as domination of the majority

by a few populous cities. Since they are scattered,

there is no reason that their interests would be uni

formly the same. The Court can take judicial notice

that they vary in size and social and economic char

acter as well as location. Indeed, to make up their

majority, appellants have been forced to include cities

with a rather small population—-Oxford, 3,603, Tus-

cambia, 8,944 and Sheffield, 13,499.

Finally, even if some weighting might be acceptable,

the argument wholly fails to justify allocating to a

majority of people only ten out of 67 senators, or less

than 15 percent.

I l l

THE APPORTIONMENT PROVIDED BY THE CRAWFORD-WEBB

ACT WOULD VIOLATE THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE,

FIRST, BY PRESERVING THE CRAZY-QUILT OF REPRESEN

TATION IN THE SENATE AND, SECOND, BY SUBORDI

NATING POPULAR REPRESENTATION IN THE LEGISLATURE

AS A WHOLE TO THE REPRESENTATION OF POLITICAL

SUBDIVISIONS TO SUCH A DEGREE AS TO CREATE GROSS

INEQUALITIES AMONG VOTEKS AND GIVE CONTROL TO

SMALL MINORITIES OF THE PEOPLE

The Crawford-Webb Act modified the preexisting

apportionment of the Alabama legislature in two re

spects. It made a few changes in the existing sena

torial districts, such as putting less populous counties

into multiple county districts and giving at least one

populous county, Etowah, a senator to itself instead of

38

making it part of a multicounty district. The statute

also reapportioned the House by assigning a specific

number of seats to each county without establishing

general criteria. An intelligible basis can be extrap

olated from the figures, however, for the legislature,

after allocating one seat per county, apparently gave

one additional seat to each county with 45,000 to 90,000

people, two additional seats to each county of 90,000 to

150,000 people, three additional seats to each county

with 150,000 to 300,000 people, five additional seats to

counties of 300,000 to 600,000 people and eleven addi

tional seats to counties with over 600,000 people. See

Brief for the Appellants in No. 23, p. 39.22

Under the Crawford-Webb Act, despite the changes,

the apportionment of the Senate would still create

gross inequalities in per capita representation without

rhyme or reason. Since the population of Alabama

is 3,266,740, and the Act provides for 35 senators, the

ratio—the population of an ideal district—is 93,335

(R. 36). That ratio cannot be achieved, however, be

cause the Alabama Constitution, as construed by the

State, prevents any one county from having more

than one senator, so that the seven counties with popu

lations in excess of 93,335 cannot receive equal per

capita representation with the rest of the State unless

22 Appellants in No. 23 also suggest (Br. 38-39) that the

Crawford-Webb Act apportions the House according to popu

lation using the method of smallest divisors. However, they

admit three deviations from the result yielded by that method

which give seats that would have gone to Jefferson and Mobile

Counties to other less populous counties. It seems plain, there

fore, that if the legislature applied any formula it is the for

mula described in the text.

39

the constitutional restriction be held invalid. How

ever, even if its validity be assumed, there are still

28 senators for the remaining counties, with a total

population of 1,729,112, which should yield one sena

tor for every 61,572 people. The apportionment would

be based upon that figure if the legislature had con

formed to the State constitution.

In fact, the Crawford-Webb Act makes no attempt

to conform to any systematic rule.23 For example, the

district with Colbert, Franklin, and Marion Counties

has 90,331 people; if Marion County were detached,

this district would still have a population of 68,494.

The adjoining district of Pickens and Lamar Coun

ties now has a population of only 36,153. Thus,

voters in the latter district have 2;l/2 times the repre

sentation of those in the former. I f Marion County

were added to this district, its population would still

be 57,990.

Similarly, Butler, Conecuh, and Covington Counties

form a district with 77,953 people. The neighboring

district of Wilcox and Monroe Counties has 41,111

people. Thus, voters in the latter district have almost

twice as much representation as those in the former.

On the other hand, if Conecuh were moved to the

district with Wilcox and Monroe, that district would

have 58,873 people and the district, comprising Butler

and Covington would have 60,191.

As one last example, the district of Autauga, Chil

ton, and Shelby Counties has a population of 76,564

23 The Senate districts under the Crawford-Webb Act and the

population of each is set forth at R. 129 and 167.

40

while the adjoining district of Bibb and Perry Coun

ties has 31,715. Thus, the disparity in representation

is approximately 2y2 to 1. I f Autauga County were

moved to the latter district, this district would have

a population of 50,454. Chilton and Shelby Counties

would then form a district with 57,825 people.

The State of Alabama has suggested no justification

for these discrepancies. More of them are based on

the limitation of one Senator to a county. The only

possible explanation is that the legislature appar

ently desired to correct only the worst of the inequali

ties which previously existed (see pp. 11-12, 37-38

above). However, serious inequalities remain and,

since they have no intelligible basis, the apportionment

violates the Fourteenth Amendment under the prin

ciples stated earlier.

2. The apportionment under the Crawford-Webb

Act would also be unconstitutional, we submit, for the

same reason as the “ 67-Senator Amendment”—the

interests advanced by the departure from per capita

equality do not furnish a reasonable basis for the

gross discrimination and utter disregard for the

principle of majority rule.

In the Senate the people of every county, however

populous, are limited to a single representative. Jef

ferson County with 20 percent of the total population

of Alabama chooses only three percent of the Senate.

Mobile County with 10 percent of the total population