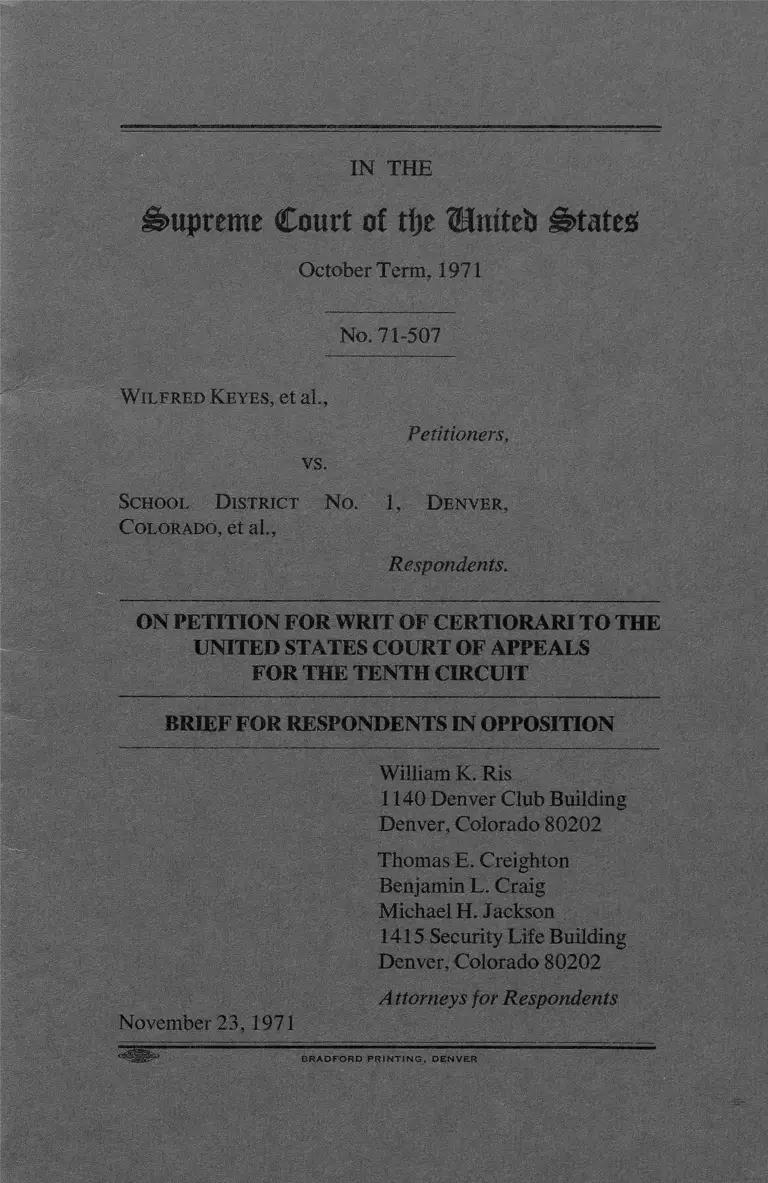

Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Brief for Respondents in Opposition

Public Court Documents

November 23, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Brief for Respondents in Opposition, 1971. 26c63ff3-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e58bc978-8100-419b-be81-8ae83148c01b/keyes-v-school-district-no-1-denver-co-brief-for-respondents-in-opposition. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfje Mmteti States;

October T erm, 1971

No. 71-507

Wilfred Keyes, el al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

School D istrict N o. 1, Denver,

Colorado, et a l ,

Respondents.

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

William K. Ris

1140 Denver Club Building

Denver, Colorado 80202

Thomas E. Creighton

Benjamin L. Craig

Michael H. Jackson

1415 Security Life Building

Denver, Colorado 80202

Attorneys for Respondents

November 23,1971

B R A D F O R D P R I N T I N G , D E N V E R

OPINIONS BELOW ................................................... 1

QUESTION PRESENTED ...... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE................ 2

INTRODUCTION................................................ 2

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS OF THE

DISTRICT COURT..................................... 3

(a ) Demographic Characteristics of Denver’s

Negro Population ............................... 3

(b) Construction of New Schools .................... 4

(c) Changes in School Attendance Areas ........ 4

(d) Other Claims of Segregation ........... 5

(e) Findings Regarding Educational Opportunity 6

ARGUMENT ................................................... 6

I. THERE IS NO CONFLICT IN THE

DECISIONS ....................................... 6

II. THE COURT OF APPEALS DID NOT ERR

IN HOLDING THAT FEDERAL

COURTS HAVE NO POWER TO

REMEDY A SITUATION NOT CAUSED

BY STATE ACTION......................... 9

III. THIS CASE HAS NO SIGNIFICANT

NATIONAL IMPLICATIONS ........ 14

CONCLUSION ............................................................ 15

APPENDIX: MAP

INDEX Page

l

TABLE OF CASES

Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d 209

(7th Cir. 1963), cert. den. 377 U.S. 924 (1964)

11, 12, 15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)....

4, 10, 11, 13

Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac, 443 F.2d

573 (6th Cir. 1971), cert, den____ U.S_____

(1971) .................................................................. 7

Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac, 309

F.Supp. 734 (1970) ..................... ....................... 7

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 419 F.2d

1387 (6th Cir. 1969), cert. den.___ U.S.

----- (1971),............ .................... ....,................... 11,15

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55

(6th Cir. 1966), cert. den. 389 U.S. 847 (1967)

11, 15

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963) .............. 10

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336

F.2d 988 ( 10th Cir. 1964), cert. den. 380 U.S.

914 (1965) ....................................................... 12,15

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ........................................... 12

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) ............................ 10

James v. Valtierra, e ta l ,___ .U .S .___ (1971)........... 14

Monroe v. Bd. of Comm’rs of the City of Jackson,

391 U.S. 450 (1968) ...................................... 12

Page

ii

Page

Raney v. Bd. of Educ. of Gould School District,

391 U.S. 443 (1968) ........................................... 12

Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d

261 (1st Cir. 1965) ............................................. 11

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ...................................... 9, 13

Taylor v. Board of Education of City School District

of New Rochelle, 294F.2d36 (2nd Cir. 1961),

cert. den. 368 U.S. 940 (1961)............................ 7, 15

United States v. School District No. 151, Cook

County, Illinois, 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968),

cert. den. 402 U.S. 943, (1971) ......... ................ 15

TABLE OF OTHER AUTHORITIES

Constitution of Colorado, Art. X X ............................ 3

iii

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfte United States;

October Term, 1971

No. 71-507

Wilfred Keyes, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

School D istrict N o. 1, Denver,

Colorado, et al.,

Respondents.

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinions below are as set forth in the Appendices to

the petition herein and in respondents’ conditional cross pe

tition No. 71-572.

QUESTION PRESENTED

The question stated by petitioners is not stated in

terms of the findings of fact in this case. In addition, peti

tioners have improperly combined the issues of their two

separate causes of action into one question in an attempt to

2

create an issue of unconstitutional deprivation as to the

whole, whereas none exists as to that part of the judgment

petitioners seek to have this Court review.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioners’ statement of this case distorts the actual facts

as found by the district court after preliminary hearing and

a lengthy trial. Petitioners make certain selective references

to evidence offered by them, as the basis for their legal

arguments and theories even though the district court re

solved conflicts as to such evidence in favor of the respon

dents. Hence respondents are obliged to restate the case in

terms of the findings of fact made by the trial court as

gleaned from its several opinions. References are to the

opinions below printed in the appendix to petitioners’

petition.

INTRODUCTION

The complaint contained two separate causes of action.

The first cause of action alleged de jure racial segregation in

certain of the schools in northeast Denver and sought deseg

regation thereof. The district court found de jure racial segre

gation existed as to three elementary schools and one junior

high school and granted the relief sought. The Court of Ap

peals affirmed.

The second cause of action alleged de jure racial segrega

tion and a denial of equal educational opportunity in other

schools in Denver and sought desegregation of all of Den

ver’s schools. The district court found no de jure racial seg

regation but did find a denial of equal educational oppor

tunity in 17 schools which were de facto segregated. The

Court of Appeals affirmed the finding of no de jure racial

segregation and concluded that there was no unconstitu

tional deprivation of equal educational opportunity.

3

The foregoing findings must be considered in light of the

number of schools in the Denver system comprised of 92 el

ementary, 17 junior high and 9 high schools totaling 118

schools.

School District No. 1 was created by Article XX of the

Constitution of Colorado in 1902. It has never maintained

separate educational facilities for different races. Pupils in

the Denver School System are assigned to schools on the

basis of their residence. School attendance areas are estab

lished for each school based upon the so-called neighbor-

hool school policy.

“It is to be emphasized here that the Board has

not refused to admit any student at any time be

cause of racial or ethnic origin. It simply requires

everyone to go to his neighborhood school unless

it is necessary to bus him to relieve overcrowd

ing.” (67a)

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

OF THE DISTRICT COURT

(a) Demographic Characteristics of Denver’s Negro Popu

lation

Prior to 1950, the Negro population in Denver was con

centrated in an area located in the north central part of

Denver (4a, 47a). (See generally map, appendix). No rec

ords of the racial composition of the schools serving this

area were kept. The schools located in this area were

largely, but not entirely, Negro. The Negro population was

relatively small and the concentration in that area had de

veloped over a long period of time. There is no finding that

any acts of the school district caused or contributed to this

situation as it existed in 1950 (4a).

4

Beginning in 1950 the Negro population experienced a

substantial growth and moved eastward very rapidly so that

by 1960 the Negro population was sizable and had ex

panded across Colorado Boulevard into the western portion

of a residential area known as Park Hill. In the 1960’s the

Negro migration continued rapidly eastward across the

northern portion of Park Hill, changing the population of

that area to substantially Negro (4a, 47a).

(b ) Construction of New Schools

Of all the new schools built by the Denver school district

since the end of World War II (Denver spent over 100 mil

lion dollars in school construction during that time), the pe

titioners complain of only two. The first, Barrett Elementary

School, completed in 1960, was treated in their first cause

of action. The district court found that it was created as a

segregated school and this was affirmed by the Court of Ap

peals (49a). It has been desegregated.

The other school, the replacement of Manual High

School in 1953, before Brown I.,1 was treated in the second

cause of action. The new school was built on the old build

ing’s grounds, and served exactly the same attendance area

(59a). The district court affirmatively found that no racial

motivation or segregative effect was present in the replace

ment of this school (61a, 71a). This was affirmed on ap

peal (149a).

(c) Changes in School A ttendance A reas

As to the first cause of action, the district court found

that four minor boundary changes (one in 1962 and three

in 1964) at two Park Hill elementary schools (Stedman and

Hallett) and the use of mobile units at one of them, consti

tuted de jure segregation (50a). This was affirmed by the

1Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

5

Court of Appeals (136a) and the district court has ordered

desegregation. No similar findings were made as to any of

the other 116 schools in the system.

In their second cause of action, petitioners claimed that

boundary changes with respect to two other elementary

schools (Columbine in 1952 and Boulevard in 1962) and

three secondary schools (Manual High and Cole Junior

High in 1956 and Morey Junior High in 1962) also contrib

uted to Negro concentrations in those schools. But the dis

trict court found that there was no racial motivation in the

changes (71a, 72a and 73a), that no racial segregation re

sulted (72a, 73a), and was unable to find, in the case of

Morey Junior High, that the school was ever segregated

(73a). The district court summarized by concluding “. . .

[w]e must reject the plaintiffs’ contentions that they are

entitled to affirmative relief because of the above-mentioned

boundary changes and elimination of optional zones. We

hold that the evidence is insufficient to establish de jure

segregation.” (75a)

The findings of the district court negate the statements in

petitioners’ statement of the case and in their statement of

the question presented that the school district created and

aggravated racial segregation throughout the entire school

system.

(d) Other Claims of Segregation

There were no findings by the district court that either

the “optional zones” or “limited open enrollment” had the

effect of minority-to-majority transfers or any other segrega

tive effect. It should be noted that limited open enrollment

was superseded in 1968 by “Voluntary Open Enrollment”

which authorized transfers with transportation furnished by

the district if the transfer had an integrative effect in both

sending and receiving schools. ( 109a, 118a)

6

(e) Findings Regarding Educational Opportunity

As to some 17 schools located mainly in the central area

of Denver and having the largest concentrations of Negro

(9 schools) or Spanish surnamed (8 schools) pupils (77a,

78a), the district court found that an “equal educational op

portunity” was not being provided, based on the conclusion

that racial or ethnic “isolation or segregation per se” (84a),

“regardless of cause” (86a), was a substantial factor which

produced low median pupil achievement scores. However,

the district court also found that other relevant factors con

stituting major causes of inferior achievement were “home

and community environment, socioeconomic status of the

family, and educational background of the parents” ( 84a).

ARGUMENT

I. THERE IS NO CONFLICT IN THE DECISIONS.

This case does not involve a racially segregated school

system created or aggravated by the defendants. The dis

trict court found it was not. Petitioners’ statements to the

contrary are not correct as has been demonstrated in the

statement of the case.

Racial imbalance in the Denver school system simply was

not caused or brought about by any actions of the school

district, except, under the findings of the district court, as to

3 of 92 elementary schools and, derivatively, one of 17

junior high schools, all of which were located in northeast

Denver and were involved in the first cause of action. The

district court has decreed desegregation of each of such

schools and petitioners do not claim error with respect

thereto (99a-121a, A3-A8 in Appendix to conditional cross

petition). Petitioners themselves elected to treat the schools

of northeast Denver separately in the first cause of action of

the complaint and they achieved the remedy sought there

under.

7

No cases have been cited holding that facts such as those

found by the district court in this case constitutionally re

quire desegregation of the entire district. Therefore, there

can be no conflict in lower court decisions.

As to the second cause of action dealing with schools in

the core area of the city, the district court expressly found

that “there is no comprehensive policy” of segregating pu

pils by race on the part of the Denver school district (74a).

Petitioners incorrectly suggest that this case bears some

resemblance to the Pontiac case (Davis vs. School District

of City of Pontiac, 309 F.Supp. 734), where system-wide

racial balancing was ordered. But in the Pontiac case the

district court, after acknowledging “that a Board of Educa

tion has no affirmative duty to eliminate segregation where

it has done nothing to create it," (emphasis supplied) went

on affirmatively to find, as a fact, that the board of educa

tion intentionally acted to create and perpetuate segregation

throughout the school system and was, therefore, guilty of

de jure segregation as to the entire system (309 F.Supp.

741,2). That court then concluded that the school officials

had an obligation to overcome the effects of such de jure

segregation, and ordered the desegregation of the entire

school system. The Court of Appeals (6th Cir.) reviewed

the findings of fact and concluded that “the findings of pur

poseful segregation by the school district” were supported

by substantial evidence and affirmed (443 F.2d 573). The

Pontiac case thus rested on the same principles applied in

this case, although the Pontiac case differs profoundly in the

facts as found by the respective district courts to the extent

of the de jure segregation found to exist. Indeed, as to the

violation and remedy, the Denver case more closely resem

bles another case cited by petitioners,2 where one school

within the school district was found to have been segregated

2Taylor v. Board of Education of New Rochelle, 294 F.2d 36 (2d cir),

cert, den., 368 U.S. 940 (1961)

8

by school authorities and where the remedy was to desegre

gate that school.

Nor do the district court’s findings as to assignment of

Negro teachers help petitioners. The only specific findings

of disproportionate assignment of Negro teachers were with

respect to two of the four schools found to be de jure segre

gated, namely, Barrett with 52.6% Negro (21a) and Smi

ley with 23 Negro teachers out of 98 (Def. Exh. S, 31a).

This does not constitute segregation of faculty and staff in

the Denver system.

To accept petitioners’ contentions, this Court would have

to extend the district court’s findings of de jure segregation

far beyond the four schools found to be so affected. Thus,

petitioners attack the district court’s findings that there was

no de jure segregative action by the school district with re

spect to five other schools in the north central part of the

city (71a-72a), findings which were sustained by the Court

of Appeals ( 148a-149a). Petitioners do not assert that such

findings of the district court were clearly erroneous, or that

the Court of Appeals erred in sustaining them. Nevertheless,

petitioners complain that the district court “excused segre-

gatory acts” on the grounds of remoteness, intervening

causes, and lack of intent (Petition pp. 18,19). The district

court did not “excuse” any acts of the district, but found no

acts constituting de jure segregation as to such schools

(67a). Such racial imbalance as existed was found by the

district court to have resulted from housing patterns (71a).

There was no finding that such housing patterns resulted

from any public or private discrimination.

Petitioners have not demonstrated a conflict in the deci

sions of the lower courts on facts such as found by the dis

trict court and affirmed by the Court of Appeals. Futher,

the decision of the Court of Appeals is consistent with the

9

recent pronouncements of this Court.3 Therefore, petition

ers have failed to present a ground for review by this Court

on the basis of conflict.

II. THE COURT OF APPEALS DID NOT ERR IN

HOLDING THAT FEDERAL COURTS HAVE NO

POWER TO REMEDY A SITUATION NOT CAUSED

BY STATE ACTION.

In their reason numbered II, petitioners contend that the

Court of Appeals erred in reversing the trial court’s ruling

that the Constitution is violated by a combination of com

paratively low median achievement test scores and racial

imbalance in 17 of Denver’s 118 schools even though it had

expressly found that such conditions were not caused by

state action.

Alleged error is not a sufficient basis to grant certiorari

under Rule 19.1(b) of the rules of this Court and the peti

tion should be denied for this reason alone.

In any event, the decision of the Court of Appeals on this

question is correct and in accord with the decisions of this

Court.

It is clear that the district court relied on so-called de

facto segregation as the major factor contributing to “un

equal educational opportunity”.'4

s“Absent a constitutional violation there would be no basis for

judicially ordering assignment of pupils on a racial basis.” Swann vs.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 27

4Throughout the trial of this case and its appeals, petitioners and the

district court have used the terms “segregation” and “equal educa

tional opportunity” generally and without defining them. Segregation

implies deliberate state action setting persons apart from each other

on the basis of race unless modified by the term “de facto” which

indicates the absence of state action. The term “equal educational

opportunity” was employed by this Court in Brown and in the context

of that case, this Court said at 347 U.S. 483, 492:

“In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably

be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity

10

The district court rejected plaintiffs’ contention that the

neighborhood school system is unconstitutional if it results

in segregation in fact (74a). Yet it concluded that segrega

tion, regardless of its cause, is a major factor in producing

unequal educational opportunity and hence is unconstitu

tional (86a-87a).

This circular reasoning was met squarely by the Court of

Appeals:

“Preliminarily it is necessary to determine

whether a school which is found to be constitu

tionally maintained as a neighborhood school

might violate the Fourteenth Amendment by oth

erwise providing an unequal educational oppor

tunity. The district court concluded that whereas

the Constitution allows separate facilities for

races when their existence is not state imposed,

the Fourteenth Amendment will not tolerate ine

quality within those schools. Although the con

cept is developed through a series of analogized

equal protection cases, e.g., Griffin v. Illinois,

351 U.S. 12 (1956); Douglas v. California, 372

U.S. 353 (1963), it would appear that this is but

a restatement of what Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954) said years ago:

‘Such an opportunity [of education], where the

state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which

of an education. Such an opportunity where the state has

undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made

available to all on equal terms.”

Thus it appears clear that the term “equal educational opportunity” as

used in Brown means that no child should be denied access to the pub

lic schools solely on the basis of his race. In other words the oppor

tunity to get an education must be made available by states to all

equally without regard to race. Respondents are not aware of any

decision of this Court extending the meaning of that term. Yet peti

tioners employ the term as though it means equal educational result.

11

must be made available to all on equal terms.’”

(142a)

❖ ❖ ❖

“The trial court’s opinion, 313 F.Supp. at 81, 82,

83, leaves little doubt that the finding of unequal

educational opportunity in the designated schools

pivots on the conclusion that segregated schools,

whatever the cause, per se produce lower achieve

ment and an inferior educational opportunity.”

(143a)

The Court of Appeals quite correctly observed that fed

eral courts have no power to resolve educational difficulties

arising from circumstances outside the ambit of state action

and held that:

“Before the power of the federal courts may be

invoked, in this kind of case, a constitutional dep

rivation must be shown. Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 U.S. 483, 493-95 (1954) held that

when a state segregates children in public schools

solely on the basis of race, the Fourteenth

Amendment rights of segregated children are vio

lated. We never construed Brown to prohibit ra

cially imbalanced schools provided they are es

tablished and maintained on racially neutral cri

teria, and neither have other circuits considering

the issue. Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education,

369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966); 419 F.2d 1387

(1969); Springfield School Committee v. Barks

dale, 348 F.2d 261 (1st Cir. 1965); Bell v. School

City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d 209 (7th Cir.

1963).” ( 145a-146a)

The Sixth Circuit had occasion recently to consider

whether the law has been changed by the decisions of this

Court5 since Brown:

r,Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 419 F.2d 1387, (6th Cir.

1969), cert, den_____ U.S______(1971)

12

“Appellants petitioned the Supreme Court for

certiorari in the first appeal and it was denied.

Certiorari was also denied in Downs and Bell,

supra. The denial of certiorari in the present case

ought to constitute our opinion in the first appeal

as the law of the case, but appellants contend that

the law has been changed by the recent decisions

of the Supreme Court in Green v. County School

Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968);

Raney v. Bd. of Educ. of Gould School District,

391 U.S. 443 (1968); Monroe v. Bd. of

Comm’rs. of the City of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450

(1968).

“In our opinion, these three decisions did not

change any law applicable to our case and appel

lants’ reliance on them is misplaced. The gist of

the holdings in these cases was that in desegregat

ing a dual school system, a plan utilizing ‘freedom

of choice’ or a variant ‘free transfer’ is not an end

in itself and would be discarded where it did not

bring about the desired result.

“On the other hand, our case involves the opera

tion of a long-established unitary non-racial

school system—just schools where Negro as well

as white children may attend in the district of

their residence. There is not an iota of evidence in

this record where any of the plaintiffs or any of

the class which they represent was denied admis

sion to a school in the district of his residence.”

This is precisely the finding of fact by the district court in

the case at bar:

“It is to be emphasized here that the Board has

not refused to admit any student at any time be

13

cause of racial or ethnic origin. It simply requires

everyone to go to his neighborhood school unless

it is necessary to bus him to relieve overcrowd

ing.” (67a)

This Court has recently considered its Brown decision in

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U.S. 1 (1971):

“We granted certiorari in this case to review im

portant issues as to the duties of school authori

ties and the scope of powers of federal courts

under this Court’s mandates to eliminate racially

separate public schools established and main

tained by state action. Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown l).

“This case and those argued with it arose in states

having a long history of maintaining two sets of

schools in a single school system deliberately op

erated to carry out a governmental policy to sepa

rate pupils in schools solely on the basis of race.

That was what Brown v. Board of Education was

all about.” 402 U.S. 1,5-6.

In defining the scope of the remedial power of federal

courts in such cases, this Court stated in Swann that:

“. . . [J]udicial powers may be exercised only on

the basis of a constitutional violation. Remedial

judicial authority does not put judges automati

cally in the shoes of school authorities whose

powers are plenary.” 402 U.S, 1 at 16.

As an example, this Court stated that school authorities

might well decide that there should be racial balance in

every school in a district as a matter of educational policy

and pointed out that, absent a constitutional violation, such

14

would not be within the authority of a federal court. 402

U.S. 1 at 16.

This review of the basic principles of separation of consti

tutional powers is appropriate here as the district judge in

his zeal to do something about educational problems that

have plagued educators for many years has exceeded his au

thority by acting in an area where no constitutional viola

tion exists. The Court of Appeals recognized this excess of

jurisdiction and corrected it ( 146a).

The holding of the Court of Appeals in this case that the

neighborhood school policy is constitutionally acceptable,

even though it results in racially concentrated schools, pro

vided that the plan is not used as a veil to perpetuate racial

discrimination, is given support by other language in

Swann: “All things being equal, with no history of discrimi

nation, it might well be desirable to assign pupils to schools

nearest their homes.” 402 U.S. 1 at p. 28. Denver has

never maintained a dual school system. Denver’s neighbor

hood school policy was in effect long before there was any

racial imbalance in its schools, (59a), and thus was never

utilized as a tool to perpetuate racial segregation. In sum,

Denver’s neighborhood school policy was and is racially

neutral (66a) and racially neutral policies of local govern

ments do not violate the Constitution6 even if they result, as

in this case, in some racial imbalance.

III. THIS CASE HAS NO SIGNIFICANT NATIONAL

IMPLICATIONS.

Petitioners conclude their reasons for granting certiorari

by stating that on either of the grounds discussed by them,

the decision of the Court of Appeals is wrong and that the

case should be reviewed because of its national implications

without stating what these implications might be. Certainly,

6This Court recently applied this same rule in a case involving alleged

discrimination in low-rent public housing. James v. Valtierra, et al,

____ U.S______(1971).

15

the national implications of federal judicial entry into the

field of determining educational policy would be significant,

but as this case now stands, the Court of Appeals has cor

rected this excess of jurisdiction leaving the problem of op

erating public schools throughout the nation where the Con

stitution intended—in the legislative and executive branches

of government and not in the judicial branch. No significant

national implications resulted when this Court declined to

review other similar holdings.7

These cases have no significant national implications

largely because they turn on their own facts which are vastly

different in different areas of the country and vary from dis

trict to district. No useful purpose would be served by this

Court's reiterating the elementary rule of constitutional law

that absent a violation of the Constitution, federal courts are

powerless to deal with educational problems.

7Taylor v. Board of Education of City School District of New Rochelle,

294 F.2d 36 (2nd Cir. 1961), cert. den. 368 U.S. 940 (1961); Deal

v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert,

den. 389 U.S. 847 (1967); Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education,

419 F.2d 1387 (6th Cir. 1969), cert, den_____ U.S. , 29 L.Ed.

2d 128 (1971); Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F,2d 209

(7th Cir. 1963), cert. den. 377 U.S, 924 (1964); Downs v. Board of

Education of Kansas City, 336 F.2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964), cert. den.

380 U.S. 914 (1965); and United States v. School District No. 151,

Cook County, Illinois, 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968). cert, den

-------U.S---------, 29 L.Ed. 2d 111 (1971).

16

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, respondents respectfully pray

that the petition be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

William K. Ris

1140 Denver Club Building

Denver, Colorado 80202

Thomas E. Creighton

Benjamin L. Craig

Michael H. Jackson

1415 Security Life Building

Denver, Colorado 80202

Attorneys for Respondents

APPENDIX

v ; * ..<. :

f/.: ‘ ■ .,’ ' ■■ >: '

1v?*;- , ’; ■' ‘

» - „ % V . \ s •: '■: .>

■• -■",

WmM

>h

:•

" , , ■ ' 1; ; .