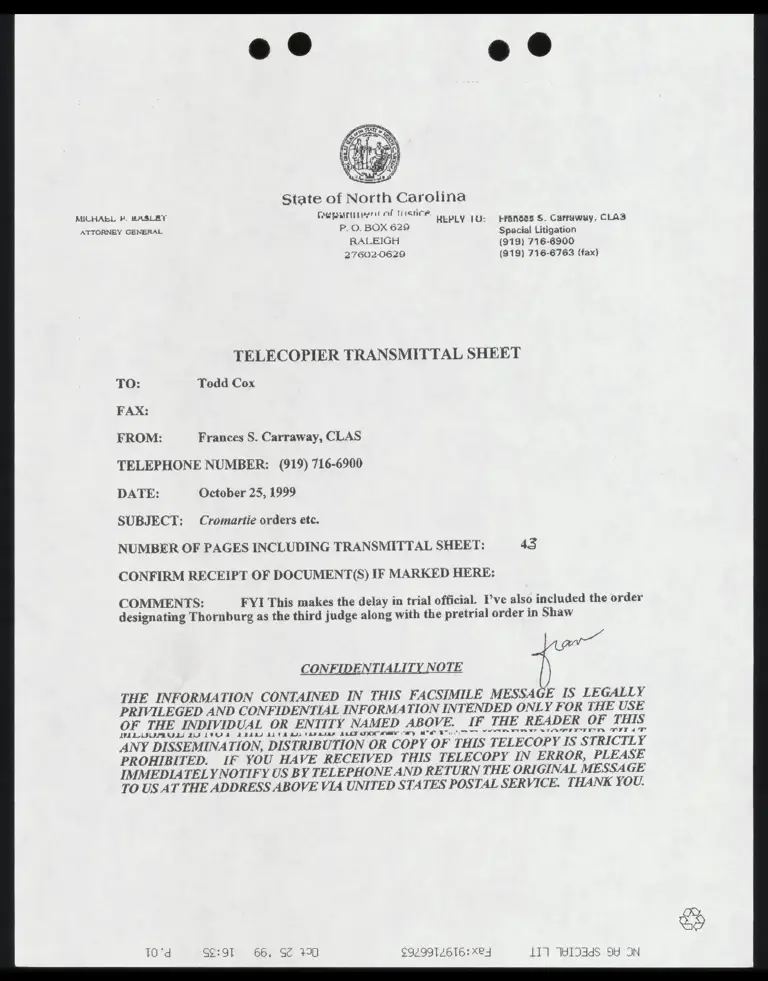

Fax from Carraway RE: Order designating Judge Thornburg as the third judge and the pretrial order in Shaw

Correspondence

October 25, 1999

41 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Fax from Carraway RE: Order designating Judge Thornburg as the third judge and the pretrial order in Shaw, 1999. f97cfb4c-dd0e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e58f7854-a812-4029-9d5a-736d17d7e5f7/fax-from-carraway-re-order-designating-judge-thornburg-as-the-third-judge-and-the-pretrial-order-in-shaw. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

State of North Carolina

MILHAEL H. BASE (WE AT STE A LLAY oly 1GHCE HEPLY 1U- FEARGas S. Carraway, CLAS

ATTORNEY GENERAL P.O. BOX 629 Special Litigation

RALEIGH (919) 716-6900

27602-0629 (919) 716-6763 (fax)

TELECOPIER TRANSMITTAL SHEET

TO: Todd Cox

FAX:

FROM: Frances S. Carraway, CLAS

TELEPHONE NUMBER: (919) 716-6900

DATE: October 23, 1999

SUBJECT: Cromartie orders etc.

NUMBER OF PAGES INCLUDING TRANSMITTAL SHEET: 43

CONFIRM RECEIPT OF DOCUMENT (S) IF MARKED HERE:

COMMENTS: FYI This makes the delay in trial official. I’ve also included the order

designating Thornburg as the third judge along with the pretrial order in Shaw

Pw of

CONFIDENTIALI OTE

THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS FACSIMILE MESSAGE IS LEGALLY

PRIVILEGED AND CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION INTENDED ONLY FOR THE USE

OF THE INDIVIDUAL OR ENTITY NAMED ABOVE. IF THE READER OF THIS

JPL SIMUL) JJ AVI A 2 FAN) ALVA AJA VARIES ALLY ODOC NEN Cary MTC WT 0ST TT VEYITL EIR YT RINT TITTY VT AT

ANY DISSEMINATION, DISTRIBUTION OR COPY OF THIS TELECOPY IS STRICTLY

PROHIBITED. IF YOU HAVE RECEIVED THIS TELECOPY IN ERROR, PLEASE

IMMEDIATELY NOTIFY US BY TELEPHONE AND RETURN THE ORIGINAL MESSAGE

TO US AT THE ADDRESS ABOVE VIA UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE. THANK YOU.

10°d of:91. 66. SC 130 £99914616: XES 117 BI12348 9d I

| AED

oy [ep

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT Cap 5 FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

No. 92-202-CIV-5-BR

RUTH O. SHAW, et al,, )

and

JAMES ARTHUR "ART" POPE,

et 2i.,

Plaintiff - Intervenors,

Vv. PRE-TRIAL QRDER

JAMES B. HUNT. et al..

Defendants,

and

RALPH GINGLES, et al.,

N

a

t

”

N

a

t

N

a

N

a

t

N

a

N

t

?

p

l

N

T

tl

V

n

V

o

g

t

N

a

i

l

e

e

r

N

o

a

V

a

a

l

a

”

N

a

“

m

g

t

“

i

Defendant - Intervenors.

I. STIPULATIONS

As ordered, the stipulations and joint exhibits thereto

have been separately filed with the court.

1x. CONTENTIONS

i. act Contentions

(1) In 1991 and 1993, the Department of Justice

adopted a policy of requiring that redistricting plans enacted

after the 1990 census maximize the number of majority-minority

districts.

" | NNEEINN W BUNNU) UL

maximizing majority-black districts clear to those states which

S0°d 28:91. 66, SZ I) £99912616: XE 111 'WIJ3d4S SY ON

were subject, in whole or in part, to Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act.

(3) This policy guided the General Assembly in its

deliberations and resulted in the adoption of Chapter 601, which

| AT HJen maj inne] NMWENEN) WANORNERI NIONN RESIRESU HA

in the northeastern part of the State.

(4) There are five majority-black counties in NorLh

Carolina, all of which are located in the northeastern part of

disweix Gouroulinuwy The pwiulicuutoldid purl ul LLL Oulu 1v ulpu LULU

area with the largest concentration of the 40 North Carolina

counties subject to preclearance requirements under Section 5.

(5) In developing the Chapter 601 plan, the General

Assembly relied on computer technology; the only data on voters

available on the computer base pertained to age, race, and party;

there was no socioeconomic data available from the 1990 census,

as this data did not become available until January 1993.

(6) After enactment of Chapter 601, the General

Assembly -- with the assistance of staff member, Gerry Cohen, and

retained counsel, Leslie Winner -- presented to the Department of

Justice extensive materials, including transcripts of hearings

and floor debates. These materials were intended to persuade the

Department of Justice to grant preclearance.

(7) On December 17, 1991, at the request of Assistant

Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division, John Dunne, a

meeting took place in his office between State and Federal

officials. At this meeting, Mr. Dunne made ¢lear that, because

90d 82:91 EL: GC WO £9L991LbTb aE 117 Wi133d45 ad IN

~~ over 20% of North Carolina’s population was African-American, it

would be necessary for two of the State’s twelve members of

Congress to be African-Americans.

(8) On Uedenpor 14, iva, JAR LURRS WEIS WW

Ms. Tiare Smiley, of the State Attorney General’s office to

inform the General Assembly that preclearance was denied; and

PURE SUISSAREAN EAE BOUUABLILIAEY UL Jd HULULU LA JULLILYYULAUA

diptrict in the scutheastexn pazt of the State,

(9) Accepting Mr. Dunut’vy bBugyestion would heave

imperilled Congressman Rose and perhap# other Damocratid

incumbents.

(10) Shortly after the letter of December 18, 1591 was

received, several North Carolina Demorraric members of Congress

suggested that the State initiate an action to seek judicial

preclearance trom a three-judge eourt in the District uf Culuwnbia

Circuit pursuant to Section 5.

(11) During this same period John Merritt, an employee

of a congressional committee chaired by Democratic Congressman

Charles Rose, received from State Représenrarive Hardawdy,

black Democrat, a plan proposing two majority-black districts, nf

which one would run through Durham and Greensboro to Charlotte

ail the other would bo in tha nesthara arse.

(12) Tuerealler John Mcrritt rcfinod Cho piaa with the

assistance of computer facilities and software of the National

CumnilLtee for an Bffcctivc Congroos (a Washingten, D.C.

20d 62:91: 66: SZ 10 $£9991616: XE 111 'IBIJ3d4S SY ON

over 20% of North Carolina’s population was African-American, it

would be necessary for two of the State’s twelve members of

Congress to be African-Americans.

(8) On December 18, 1991, John Dunne wrote to

Ms. Tiare Smiley, of the State Attorney General's office to

inform the General Assembly that preclearance was denied; and

Dunne suggested the possibility of a second majority-black

district in the southeastern part of the State.

(9) Accepting Mr. Dunne’s suggestion would have

imperilled Congressman Rose and perhaps other Democratic

incumbents.

(10) Shortly array rne lacrer of Duteubur 18, 1351 was

received, several North Carolina Democratic members of Congress

suggested that the State initiate an action to seek judicial

preCleusuuct from a thicc judge couws dm the Distwiztr ~F Onl nmi a

Circuit pursuant to Section 5.

{11) During this same period John Merritt, an employee

of a congressional committee chaired by Democratic Congressman

Charles Rose, received from State Representative Hardaway, a

black Democrat, a plan proposing two majority-black districts, of

which one would run through Durham and Greensboro to Charlotte

and the nther wonld be in the northern area.

(12) Thereafter John Mexritt refined the plan with the

assistance of computer facilities and software of the National

Committee for an Effective Congress (a Washington, D.C.

20°d Op:91 66 SZ +30 £99914616:XeS 111" WIH4S 9d ON

organization that supports Democratic candidates for Congress);

and then he transmitted the plan to the NAACP in North Carolina.

(13) Subsequently, the Merritt plan was presented at a

public hearing in Raleigh by Mary Peeler on behalf of the NAACP

on January 8, 1992; and, with some modification, it was adopted

as Chapter 7.

(14) In enacting Chapter 7, the General Assembly

proceeded on the assumption that preclearance from the Attorney

General of the United States could not be obtained for a

Congressional redistricting plan that did not contain two

majority-black Congressional districts.

(15) As was reflected in statements at the time, the

General Assembly enacted Chapter 7 wilh Lhe intent to assure the

election of two African-American members of Congress by creating

two majority-black districts.

(16) At the time of the enactment of Chapter 7, the

overriding legislative purpose was racial; and there was no

consideration by the General Assembly of socioeconomic data apart

from race.

(17) In ecomunecLlon wilh Lhe use of computer tcchnology

in redistricting after the 1990 census, the General Assembly had

acquired software from PSA, a vendor of such software. TO

facilitate the creation of a majority-minority districts, this

program was modified to permit the creation of districts that

would be "point contiguous". Becauge of this modification or

otherwise, significant discrepancies have been discovered by

80d Op:91 66: SZ 130 £9/991.616: Xe 4 1171 WIAs ad JN

Plaintiffs in the computer program used for Congressional

redistricting by the General Assembly. As a result, it is not

certain that all of the Congressional distridt are gither

contiguous or equal in population.

(18) The criteria for Congressional redistricting used

by the General Assembly never included compactness, and in the

redistricting compactness was ignored and many political

subdivisions ware split hetwsen mars than one district.

(19) In seeking to justify the bizarre districts which

have been created by Chapter 7, the Defendants have relied on

socioeconomic data that were neither available to the

Legislature, nor considered by it while the redistricting was

unazayway.

(20) The districts that have been created by Chapter 7

cross many media markets; and this circumstance makes it

difficult for voters to obtain information about their

Representatives in Congress or for those Representatives to know

the voters or the various local officials in the district. Also,

this circumstance makes it more difficult for voters to learn

apour cuntlddles fur Cunyrwss ur fur candidates to have adequate

opportunity to inform voters about the candidates.

(21) Until the 1992 redistricting, the First District

had been coastal, but after the redistricting this was no longer

true. Until the 1992 redistricting, the First District had only

been located in the northeastern part of the State; but after

January 1992 this district extended almost to South Carolina.

60d ¥p:91 66. SZ 190 £9/9912616: Xe 4 1171 W1EL4S 95 J

Pan (22) Por the Chapter 7 redistricting plan, the First

District was extended southward in order to create a

majority-black district by including urban black neighborhoods in

Wilmington and in Fayetteville, neither of which cities had

previously been in the First District.

(23) In establishing the Twelfth District, the General

Assembly made no effort to determine that the white residents

would have anything in common other than race; and this also was

true for the Twelfth District.

(24) The population of North Carolina is mobile; and

many whites and African-Americans now resident in North Carolina

were not living in North Carolina when the Voting Rights Act of

1965 was enacted.

(25) During thc dcbatee and hearing on the

Congressional redistricting, no comment was made that any of the

district would conform or correspond in any way to the route of

the North Carolina Railroad or other corridor of the Piedmont

Crescent.

(26) The splitting of precincts and other political

subdivisions by Chapter 7 generated confusion among voters.

(27) As a result Of the rorty percenlL plurality

provision which took effect in 1990, the overwhelming Democratic

registration of African-Americans in North Carolina, and the

closed nature of Democratic primaries, it is unnecessary to

create majority-black Congressional district in order for

African-Americans to be elected to Congress.

Old Zp:91 66: 2 30 £99912616: XE 111 BI23d4S 99 ON

(28) In elections with white and black candidates,

Black voters jin North Carolina have demonstrated less willingness

to vote for white candidates than white voters have demonstrated

to vote for black candidates; and white crossover voting has

Lucredsea,

(28) The number of black elected office holders in

North Carolina is substantial and has greatly increased since

1965,

(30) Racial appeals greatly diminished in North

Carolina over the years.

(31) Black registration levels in Narth Cavolina are

close to those of whites; and in some district exceed the

registration rate for whites.

2, Legal Contentions

7 (1) In view of the overriding race-driven purpose of

the Chapter 7 redistricting plan, that plan constituted a racial

gerrymander.

(2) The Department of Justice greatly exceeded its

authority wnAdesr Qamtrisn & Af tha Vetiayg Righse Acb whon it

insisted that any Congressional plang for North Carolina include

tow majority black districts.

(3) The racial gerrymander created by Chapter 7 served

no compelling state interest and was not narrowly tailored by the

North Carolina General Assembly.

(4) Equal Protection under the Fourteenth Amendment is

denied when, as with Chapter 7, voters are placed in particular

11'd Zp:91 06: SE AI) $£99914b16: XE 117 H1345 9d ON

Congressional districts for the purpose of assuring the election

Ul persuus who arc of & pawsseulax 274

(8) Thea creation of the two North Carolina

majority-black districts not only violated Equal Protection but

also abridged the right-to-vote of the Plaintiffs and all other

North Carolina voters in violation of the Fifteenth Amendment.

(6) The creation of race-driven majority-black

Congressional Districts is contrary to Article I, § 2 of the

Constitution.

(7) The socioeconomic data that only became available

to the General Assembly after Chapter 7 was adopted may not be

relied on by the State to justify the enactment of Chapter 7.

(8) Because the black population of North Carolina is

relatively dispersed, a majority-black district cannot be created

in North Carolina without violating traditional redistricting

principles, such as compactness, contiguity, and recognition of

communities of interest and political subdivisions.

(9) In view of the overriding race-conscious purpose

of the Legislature in enacting Chapter 7, the second plan was

unconstitutional.

(10) All evidence of socioeconomic data is

inadmissible unless the General Assembly considered it prior to

enacting Chapter 7.

(11) Chapter 7 had the intended effect of segregating

the black voters of the First and Twelfth Districts from the

white voters of the other ten districts.

Z1'd ep:01 66: SC 1) £94991.616: XE 117 WI34S 90 Jy

(12) The use of single-member Congressional Districts

required by 2 U.S.C. § 2(C) is inconsistent with a system of

proportional representation.

(13) Under 2 U.S.C. § 2(a), if North Carolina fails to

redistrict in a constitutional manner, then eleven

Representatives must be chosen from the eleven districts that

existed prior to the 1000 census and the radistriqting, and one

Representative would be chosen at large.

(14) All voters of North Carolina, regardless of their

race, have a constitutional right to participate in an electoral

process that is racially neutral and that does not use racial

classifications.

(13) Tul iriyudivmeut by vho Dopartmons ef Jwekkwa Yhns

two majority-black Congressional districts be created did not in

any way create an immunity nor constitute a defense for the

defendants.

(16) Chapter 7 is not a narrowly tailored remedy but

instead ig a racial gerrymander.

(17) B11 of the Plaintiffs have suffered an injury to

rnair CONETITUCIOonal TigHEy oY NdVE dll ullier Nullll Carulliua

voters.

(18) In view of the passage of two years and the

conducting of one election since Plaintitfs sued, the Court

should grant immediate relief and enjoin any congressional

primaries under the present plan.

£1'd Pr:91 66: SZ 30 £929914616: XES 111 BI 345 od IN

B. Plaintiff - Yvenors.

With the exception of legal contention No. 8,

Plaintiff-intervenors’ adopt the contentions of plaintiffs and

also state as follows:

1. Factual Contentijong:

(1) That the overriding purpose behind the

North Carolina General Assembly’s enactment of Chapter

7 of the 1991 Session Laws (Special Bession) was

compliance with the United States Department of

Justice’s demand for two congressional districts with

black voting majorities in a manner that would not

jeopardize the reelection chances of incumbent

Democratic congressman.

(2) That, in creating the two majority black... .

districts contained in Chapter 7, the General REBRDIY

disregarded traditional districting principles such as

geographic compactness, contiguity, and respect for

political subdivisions.

2. Legal Contentions:

(1) That Chapter 7 violates Plaintiff-

intervenors constitutional right to the equal

protection of the laws by segregating them into

separate voting districts because of their race.

(2) That the state’a intentional use

racial classifications in enacting Chapter 7 is

1d PPO] 66. SZ 130 £929914616:XES 117 "HI)34S 9 IM

justified by a compelling state interest nox narrowly

tailored to meet any such interest.

Defendants and Defendant-Intervenors

1. Defendants and Defendants-Intervenors Contend that

Plaintiffs Cannot Prove a Racial Gerrymander.

ntentions a Racial Ger

(1) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

contend that plaintiffs have the initial burden of

proving that they have standing to pursue their

claim by establishing that the alleged racial

gerrymander has caused them to suffer the harm

alleged in their claim. The harm relied on by

plaintiffs to give them standing to pursue their

racial gerrymander claim is (1) that Congressmen

watt and Congresswoman Clayton do not need to

respond and will not respond to the needs of white

voters and (2) that the plan exacerbated racial

block voting. Such forms of harm may not be

presumed and must be established by specific

evidence. See Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109,

131-32 (1986).

(2) Defendants and defendant - intervenors

contend that Federal law imposed a series of

obligAtLANE SN THE UBNErdL AQHEUWLY Ll edacllly

the congressional redistricting plan. First, one-

11

Sl 'd SPr:91 66.SC 330 £949912616: XE 1177 IBIJ34S 99 ON

person, one-vote principles established by the

Supreme Court in Baker v, Carr, 369 U.8. 186

(1962) and its progeny required the General

Assembly to have a new congressional redistricting

plan in place in time for the 1992 elections which

contained 12 districts with equal populations.

Second, Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42

U.S.C, § 1973¢c, forbade the General Assembly from

implementing any plan for 1992 elections without

first obtaining preclearance of that plan from the

Department of Justice or the federal courts.

Third, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42

U.8.C. § 1973, required the General Assembly to

avoid dilution of the voting rights of minority

citizens.

(3) Defendants and defendant-intervenors also

contend that the discretion to determine how to

meet the requirements of federal law, what

additional criteria should be applied in enacting

a plan and what weight Should be given those

additional criteria was the prerogative of the

General Assembly. Growe v. Emison, 113 S. Ct.

1075, 1081 (1992) ("Today we renew our adherence

te the principles . . . which derive from

recognition that the Constitution leaves with the

States primary responsibility for the

12

91 4d op:91.. 66: SC: 10 £929914616: XES 117 BIJ3d4S 99 ON

21d

apportionment of their federal congressional . . .

districts.")

(4) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

contend the plan enacted by the General Assembly

meets one-person, one-vote requirements, was

precleared by the Department of Justice and that

the courts have determined that the plan is not an

unlawful political gerrymander. Pope V. Blue, No.

3:92CV71-P (W.D.N.C. April 16, 1992), aff’d mem. ,

113 S.Ct. 30 (19%2).

(5) Plaintiffs’ only claim is that the plan

is an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. They

have acknowledged that the burden of proof on that

issue rests with them. The parties, however,

disagree about the elements of a racial

gerrymander claim.

(6) Plaintiffs seem to contend that a racial

gerrymander claim has three elements: (a) that

the plan creates oddly shaped districts that 4o

not conform to existing political or natural

boundaries; (b) that the plan disproportionately

groups citizens in districts based on their race;

9r:91

and (c) that race was the cause Or predominate

cause of the shape of the districts.

(7) Defendants and defendant -intervenors

contend that proof of these three elements is not

13

66. SC +30 £929914616: Xe 1171 WIJ3dS Sd On

sufficient to establish a racial gerrymander for

the simple reason that Sections Z apd 5 Or the

Voting Rights Act required the General Assembly to

account for race in drawing the districts and

therefore that accounting for race cannot in and

of itself be unlawful. Stated differently, proof

that the General Assembly accounted for race is

not proof in this context of an unlawful

intention; it is proof of an intention to comply

with federal law.

(8) Defendants and dcfendant-intervennrs thus

contend that proof of a racial gerrymander

requires proof of a fourth element. This element

has two parts: (1) that there is no rational

explanation for the location and shape of the

districts other than race and (2) that the plan

has no rational basis other than race. Defendants

and defendant -intervenors contend that this

element is expressly required by Shaw, 113 S. Ct.

at 2832. ("We conclude that a plaintiff . . . may

state a claim by alleging that the legislation,

though race-neutral on its face, rationally canuot

be understood as anything other than an effort to

segregate voters into different districts on the

basis of race.") See also Marylanders for Fair

Representation v. Schafer, No. 5-92.510 (D-Md4.

14

81 'd P:91 +. 66. 92 330 £99914616: XE 117 HI13345:90 DN

7. January 14, 1994) (three-judge court). Defendants

and defendant-intervenors further contend that

this fourth element is an entirely logical

requirement of a racial gerrymander claim.

Subject to the constraints of federal law,

redistricting rests within the sound discretion of

the states. Accounting for the requirements of

federal law, particularly the requirements of the

Voting Rights Act, in developing a redistricting

plan cannot be unlawful unless there is no

rational explanation for the location and shape of

the digtricts other than race Or unless the plan

has no rational basis other than race.

(8) Defendants and defendant -intervenors

contend that plaintiffs have the purden of proof

on this fourth element of their racial gerrymander

claim, just as they have the puraen uf pruul on

the first three elements. That burden is to prove

that there is no conceivable rational explanation

FOF rhe lovaliun and shapc of tha distriers orher

than race and that there is no rational basis for

the plan other than race. Vance v. Bradley, 440

U.8, 93, 111 (1979). Alternatively, defendants

and defendant-intervenors contend that if

plaintiffs prove the first three elements of their

claimg, they have established a prima facie case

15

bl 'd 2:91 66, SZ) £929914616: XeS 1171 BIJ3d4S 98 ON

DZ °d 8:91

which would require defendants and defendant-

intervenors to articulate the rational explanation

for the location and shape of the districts or

rational basis for the plan. Proof of a prima

facie case, however, would not shift the burden of

proof to defendants and defendant-intervenors; it

would merely impose on defendants and defendant-

intervenors the burden of going forward with the

evidence. The ultimate burden of proving that

there is no rational explanation for the location

and shape of the districts other than race and

that there is no rational pasis for the plan other

than race rests with the plaintiffs. See Rarcher

v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725, 760 (concurring opinion)

("In order to overcome a prima facie case of

invalidity (of a redistricting plan], the State

may adduce ‘legitimate considerations incident to

the affectation of a rational state policy.’ ?; *1f

a state is unable to respond to a plaintiff's.

palma focic 0A66 by showing that it is supported

by adequate neutral criteria, I believe the court

could properly conclude thdl Lhe challecngcd schema

ig either totally irrational or entirely motivated

by a desire to curtail the political strength of

the affected group."). 66. SZ 190 $£99912616: XE 1171 WI33d4S a4: IN

V ti. (10) In sum, defendants and defendant -

intervenors contend that plaintiffs cannot prove a

racial gerrymander unless they establish by a

preponderance of the evidence both:

(a) that the location and shape of the

districts cannot be explained by legitimate

factors than race; and

(b) that the plan has no rational basis

other than race.

b. Factual Contentiong as to Racial GCerrymander

Slam,

(1) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

contend that plaintiffs have failed to prove they

have suffered the harm alleged in their complaint.

(2) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

conLund Ullal there is a rational explanation for

rhe location and shape of the districts other than

rdud,

(a) Prior to the enactment of the 1982

congressional plan, the location and shapes

of congressional district boundaries was the

result of the location and shapes of the

county boundaries themselves since the

General Assembly followed a policy of not

dividing counties. These boundaries were

17

1¢°d 6P:91 66: SZ 130 £949914616: XE 1171 0134S ae ON

established based on historical and political

circumstances going back over 200 years.

(b) In 1982, the U.S. Department of Justice

objected to a 1968 constitutional amendment

adopting a policy of not dividing counties

and it also objected to the State'’s

congressional redistricting plan. The

General Assembly proceeded to enact a

congressional redistricting plan which

divided anme counties, naing precinet and

township boundaries. The boundaries and

shapes of precincts and townships tend to be

irregular. Township boundaries were created

based on individual historical and political

circumstances unique to each locality.

Precinct boundaries are drawn and redrawn by

local County Boards of Elections based on

historical, political and other local

circumstances unique to each county.

(¢) The shapes of the congressional

districts in the enacted plan, Chapter 7,

reflect the shapes of the building blocks

available on the legislative redistricting

database, which include county, township,

municipal and precinct boundaries as well as

prior house, senate and congressional

18

ZZ:'d BP:91 7 66: SZ 330 £949914616: XES 1¥) W1314S 9d IN

~~ pounder lus, uld municipal ond sowashinp

boundaries, and census block boundaries.

Census block boundaries are established by

the U.S. Censug Bureau using only visible

features or township or municipal boundaries.

Prior to the drawing of any districts, some

sapsus plocky were divided by the U.8. conaus

Bureau and the legislative staff to provide

demographic data where precinct boundary

lines and township lines did not coincide

with census blocks. Similarly, census blocks

were also divided by the legislative staff to

provide demograpflf 83ata WiELE Leusus Llu

did not coincide with prior house, senate and

congressional district boundaries. The large

nurber of preexisting jurisdictional and

census block boundary lines available in the

database provide a panoply of building

blocks, each with its own origin, with which

to create congressional districts.

(d) The location and shapes of all

congressional districts were affected by the

strict one-person, one-vote requirements

applied to congressional redistricting. With

the computer tools available population

deviations can be reduced to zero Or one

13

£2 4d 05:91 66:92 130 $£92991.616: XE 117 W135 “al IN

person, and the boundary lines where each

disctricro is "zeroed gut” are irregular.

(2) The location and shapes of districts

were also influenced by the General

Assembly's obligation to comply with §§ 2 and

5 of the Voting Rights Act.

(f) The location and shapes of the districts

were also affected by the General Assembly's

decision to create complimentary urban and

rural districts. In creating a district with

more than 80% of its population in urban

areas, it was necessary to remove areas with

low population density. Similarly, to create

a district in the sparsely populated eastern

i part of the state it was necessary to include

large land masses, and to limit the number of

people from towns with populations of more

than 20,000 in order to maintain a district

in which 80% of the people lived in towns of

less than 20,000 people.

(g) Protection of incumbents was another

major factor influencing the location and

shapes of the districts in the enacted

congressional districting plan. Decisions on

how and where to include and exclude

particular areas in the different districts

20

Cd 05:91 66.5 330 £99914616: Xe 111" WH13345- 9d ON

ald 16:91 6b.

were based on a desire to protect i1ncumbéils.

The shapes and widths of connecting areas and

the direction taken in connecting other areas

were also based on a desire to protect

incumbents.

(h) Specific political interests of

individual State legislators also resulted in

the inclugion or exclusion of specific areas

in different districts and affected the

anapas of rhe congressional diseriviy,

(i) Maintaining the existing partisan

balance in the State’s congressional

delegation was also a major factor

influencing the shape of the congressional

districts.

(3) Thare is ne £adexral srarntary Ar

constitutional requirement that Congressional

districts be compact or contiguous.

(x) There is no North Carolina Statutory OF

constitutional requirement that Congressional

districts be compact or contiguous.

(1) The criteria established by the

redistricting committees of the General

Assembly did not provide that Congressional

digtrinra ha geographically compact.

21

SC 130 £929914616: XEA 117 "BI23d4S Sd ON

(3) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

contend that there is a rational basis for the

districts other than race.

(a) In enacting the plan the General

Assembly emphasized the creation of districts

containing citizens with shared interests and

concerns over geographic compactness. The

General Assembly was "pushed" to deemphasize

geographic compactness because of the

stringent population equality standards

established by Baker and its progeny, because

of Voting Rights Act requirements and because

of a desire tc protect political interests.

It was "pulled" to emphasize communities of

interest because creation of communities of

interest is consistent with the purpose of

redistricting -- to provide fair and

effective representation for voters.

(b) Forming districts in which voters share

common interests and concerns allows a

representative better to know and represent

the needs of his or her constituents and thus

helps provide fair and effective

representation for voters.

(¢) In drawing the districts the General

Assembly also emphasized the creation of a

22

9d 5:97. 66.5% 390 £99914616: XE 111 WIJ34S 9” ON

distinctive urban Piedmont district (the

Twelfth District) and a distinctive rural

eastern district (the First District) over

geographic compactness.

(d) Forming distinctive districts allows for

broader representation of the diverse

interest of the State’s citizens by the

members of the congressional delegation as a

whole and thus helps provide for fair and

effective representation for more citizens.

(e) An analysis of the present day socio-

economic and demographic characteristics of

the citizens in each of the twelve districts

created by the congressional redistricting

plan establishes that the First District is a

distinctive district which groups together

citizens who have common interest and

concerns in that the citizens in the

district, black and white alike, are BOSrer

MAE AEE YWelk-Sovsabed Shan VhbiEsnE ah any

other district. That analysis also

establishes that the Twelfth District is a

distinctive district which groups together

citizens who have common interests and

concerns in that they reside in a district

far more urban than any other district.

23

2%: 4 2691 66. SC: 130 £9/9914616: XE 117 IBIJ34S SY ON

(f) Forming a distinctive digtrict comprised

of poorer and less well-educated citizens is

consistent with providing fair and effective

representation because education and income

influence voting behavior. Similarly,

forming a distinctive district comprised of

urban dwellers is congistent with providing

fair and effective representation because

urban dwellers have common needs and concerns

that influence voting behavior.

(g) A survey of the opinion of voters in the

First and Twelfth Districts establishes that

their common socio-economic interests produce

similar opinions among black and white voters

ZS on issues relevant to the responsibilities ot

members of Congress. This same survey also

establishes that the opinions of voters in

the First and Twelfth Districts on these

issues axe move similar than the opinions

among voters in the Fourth District, even

though the Fourth District is far more

geographically compact.

(h) The distinctive common interests of the

citizens in the First District are a product

of the district’s location within the Coastal

24

8C 'd £5:91 © 66: 5C 190 £949914616: XES 117 Wi133dS ad. ON

Plain where citizens share a common history,

culture and economy.

(i) The distinctive common interests now

possessed by citizens of the First District

will continue at least through this decade.

The area in which the First District is

located is experiencing, and will likely

continue to experience, economic stagnation

and population losses.

(4) The distinctive common interests of the

citizens in the Twelfth District are a

product of the district’s location within the

Piedmont Urban Crescent where citizens share

a common history, culture and economy. The

Twelfth District generally traces the axis of

the Piedmont Urban Crescent which extends in

an arc from Raleigh thru Durham, Greensboro,

Winston-Salem and Charlotte to Gastonia. The

Piedmont Urban Crescent is a recognized place

in North Carolina’s history, geography and

demography and traces its origins to the

construction of the North Carolina Railroad

in the 1800's, later cemented by the

construction of 1-85. Instruction regarding

the Piedmont Urban Crescent is a part of the

public school curriculum.

25

bl 'd £5197» 66; .92 130 £949912616: XE 117 W1034S 9d" IN

(k) The distinctive common interest of

citizens of the Twelfth pPistrxrict will

continue at least through this decade. The

Piedmont Crescent is, and likely will remain,

the center of urbanization and economic

growth in the State.

(3) Defendants and defendant -intervenors

contend that the General Assembly’s focus on

creation of communities of interest, rather than

on geographic compactness, was appropriate. Facts

supporting the contention are summarized below:

(a) There is no known, direct, empirical

relationship between geographic compactness

and providing fair and effective

representation for voters. Geographic

compactness may tend to promote fairer and

more effective representation of voters

because it tends to make travel and

communication easier. Modern transportation

and means of communications, however, make

geographic compactness less important for

providing fair and effective representation

than in earlier times.

(b) Modern transportation and communications

make the First and Twelfth Districts

substantially compact. Large parts of the

26

0g 'd $5:91. 66. SC 1d] £9/9914616: XS 1177 WIJ3dS 99 ON

ETI © TOR ET SAAT VPA

First District are connected by Interstate 40

and 95. The Twelfth District is linked .

together by Interstate 40, 77 and 85. The

average travel time from one end to the other .

of all twelve districts is 2.6 hours. The

travel time from one end of the First

District to another is 4.17 hours. The

travel time from one end of the Twelfth

District to another is 2.9 hours. More than

30,000 citizens commute among the counties in

the First District on a daily basis. More

than 100,000 citizens commute among the 10

counties in the Twelfth District on a daily

basis.

(¢) The average district is served by three

television markets. The voters in the First

District are served by four television

markets. The voters in the Twelfth District

are served by three television markets. The

total daily newspaper circulation in the

First District counties for the three largest

newspapers serving the district is 116,006.

The total daily newspaper circulation in the

Twelfth District counties for the four

largest newspapers serving the district is

337,577.

27

1£°d Ga:91 | 66. SZ 130 £9.9912b16:XeS 1171 BI23d4S 59 ON

(d) Geographic compactness is more important

for districts served by paxt-time legislators

with small budgets and small staffs, like the

members of the General Assembly, than for

districts served by full-time legislators

with larger budgets and staffs, like the

member of Congress.

(2) There is no evidence that the more

geographically compact a district is the more

alike the opinions of voters will be. To the

contrary, the opinions of voters in the First

and Twelfth Districts on issues relating to

the responsibilities of members of congress

appear more alike than the opinions of voters

in the geographically compact 4th district.

(f) Similarly, there is not evidence that

geographically compact districts group

together citizens better than less

geographically compact districts. To the

contrary, an analysis comparing the gocio-

economic and demographic characteristics of

citizens in the twelve districts in the 1932

congressional plan and the socio-economic and

demographic characteristics of citizens in

the eleven district in the 1982 congressional

plan establishes that the 1992 districts,

28

Zed G5:91 66: SZ £9/991.616: Xe 4 111 BIJ3d4S S56 ON

though less geographically compact than the

1982 districts, group citizens with common

interest and concerns better than the 1982

districts. This analysis also establishes

that the 1992 districts are more BOCiO-

economically distinctive than the 1982

districts.

2. Defendants and defendant-intervenors Contend that

Even If Plaintiffs Prove a Racial Gerrymander the

Plan is Narrowly Tailored to Serve Compelling

Interests.

a. Legal Contentiong as £oO Compelling Interests.

(1) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

contend that if plaintiffs prove a racial

gerryilander, Ll Cuuil must then dctormine whather

the plan is narrowly tailored to serve a

compelling interest. Shaw, 113 S.. Cc. .at 2830

("if appellants’ allegations of a racial

gerrymander are not contradicted on remand, the

District Court must determine whether the General

Assembly’s reapportionment plan satisfies strict

scrutiny.)

(2) Defendants and defendant -intervenors

contend that the state had a compelling interest

in creating two majority-minority districts to

comply with the state’s burden under Section 5 of

29

ged 95:91 “66. SZ 10 £929914616: Xe 111 "WI33dS SY ON

the Voting Rights Act, as established by the

Attorney General, to prove that the submitted

change did not have the purposi¢ Of ailuting black

voting strength. Rome v. United States, 446 U.S.

156 (1980); 28 CFR § 51.52.

(3) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

contend that the state had a compelling interest

in creating two majority-minority districts to

comply with its burden under Section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act to establish that the submitted

change aia not violate Sevtluu 2 ul the Voting

Righte Aot. 28 CFR § B1.55(a) (2).

(4) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

contend that plaintiffs are foreclosed from

rr challenging in this Court the Attormey General's

Section 5 objection to Chapter 601 as this Court

has already determined because that conclusion was

left undisturbed by the Supreme Court.

(5) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

contend that the state had a compelling interest

in creating two majority-minority districts on the

basis of its power to eliminate racial

discrimination, to increase electoral opportunity

under Section 4 (f) of the Voting Rights Act, tO

achieve a broadly represeuLdilve cuuyressluual

delegation and to insure substantive

30

Fed 95:91 66: SZ 130 £929914616: XE 1171 BIO3dS 99 ON

representation of an historically submerged

minority.

(6) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

contend that Regents of the University of

California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1970), provides

an appropriate analytical framework for deciding

the compelling interest issues. In Bakke the

Court struck down a medical school admission

policy which made the race of applicants the sole

determinant in admissions decisions, but observed

that an alternative policy under which "race or

ethnic backgréutd 1B SIMPLY UNE HieueuL == LU Ue

weighed fairly against other elements" -- in a

process luleuded Lu aLtain a "diveroo etwudant

body" whéré a "Yopust extldiye ul ideas” would

occur would not violate the Fourteenth Amendment.

As applied in this context, the Bakke analytical

framework would require the Court to determine

whether race was fairly weighed against other

redistricting criteria (e.g., creation of

communities of interest) to produce a

redistricting plan that provided representation

for North Carolina's diverse voters.

(7) Defendants and defendant-intexyvenors

contend that the General Assembly had a compelling

interest in complying with Section 2 of the Voting

31

Sf 'd 25:91 0 66: SZ. 330 £929914616: XE 117 "IBIJ34S 99 ON

JU —— p— Te REE ET RIV LT

Rights Act. A compelling interest tO comply with

Section 2 exists in this czes if thers Ave

reasonable grounds to believe that not creating

two majority-minority district may have violated

Section 2. Proof that failure to create two

majority-minorxity districts is not required.

Voinovich vi Quilter, 113 8. Ct. 1149, 1159

(1993); Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education, 476

U.S, 267, 292 (0'Connor, Jd., concurring) ; Johnson

v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara County, 480

U.Y8. blb, bbz (i1¥Li/) (OU Culler, T., conoux®&ng)

(8) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

contend that whether reasonable grounds existed to

believe that failure to draw two majority-minority

7 districts might have violated Section 2 ig to be

assessed by examining the threshold requirements

for a violation of Section 2 established in

Thornburg v. Gingles, 479 11.S. 30 (1986): (1)

whether the population of African-American

citizens is sufficiently large and geographically

compact to constitute a majority in a single

member district; (2) whether African-Americans are

politically cohesive; and (3) whether white

citizens usually vote as a block to defeat the

candidate of choice of African-American citizens.

Defendants and defendant - incervenors contend that

32

99d 85:91. 66: SC +30 $£9991.616: XES 117 BIJ3dS 99 ON

the Gingles geographic compactness requirement is

to be evaluated on a functional basis.

Marylanders for Fair Representation, supra;

Dillard v. Baldwin County Board of Elections, 686

®W Qupp. 148Q, 14RR-AR (MTN Al=x 1QRRAR)

(9) In the redistricting context, since the

goal of the state’s action is to avoid diluting

the voting strength of the black community, a plan

is narrowly tailored (1) if it creates only as

many majority-black districts as are necessary to

avoid vote dilution: (2) if the districts it

creates do not pack black voters in concentrations

yrealer Lau whal las reasonebly necessary to

provide black voters an equal opportunity to elect

a candidate of choice; and (3) if the plan also

accommodates other important state interests, such

as recognizing communities of interest and the

Protecrion Of incumpenls. Wueller ur aul Lue

districts in the plan are relatively

geographically compact, according to arbitrary

mathematical measures of compactness, is

irralavant +n a detarmination of whether the plan

is narrowly tailored to avoid a violation of § 2

uf the voulnyg Riylls Acl.

(10) Defendants and defendant - intervenors

rontend thar while thev have the burden of

1

8d 85:91 66: SC 30 9.991616: XE S 117 HI134S 99 ON

producing evidence of a compelling interest and

narrow tailoring, the burden of proving the

absence of a compelling interest and narrow

tailoring rests with the plaintiffs. Wygant, 476

U.S. at 283 (O'Connor, J., concurring) (*Itc is

incumbent upon [the plaintiffs] to prove their

case; they continue to bear the ultimate burden of

persuading the court that [the defendants’)

evidence did not support an inference of prior

discrimination and thus a remedial purpose, or

that the plan instituted on the basis of this

evidence was not gufficiently narrowly tailored.")

b. Factual Contentions as to Compelling Interest.

(1) Defendants and defendant-intexvenors

contend that the evidence described above

establishes that race was fairly weighed with

other legitimate redistricting criteria to create

a redistricting plan that provides for fair and

effective representation of North Carolina's

diverse population and thus that a compelling

interest hag heen estahliehad nndar Ralls,

(2) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

contend that there were reasonable grounds for the

General Assembly to believe that the threshold

elements of a Section 2 claim under Gingles could

be established if it had not created two majority-

34

82d 65:91 66, .5C 1] £9.991.616: Xe 4 11371 11 AS Od ON

minority districts. Specifically, defendants and

defendant intervenors contend that plaintiff-

intervenors’ Shaw Plan 2 provides reasonable

grounds to believe that the African-American

population is sufficiently large and

geographically compact to constitute a majority in

a second district. Defendants and defendant-

intervenors further contend that the evidence

prepared by Dr. Richard Engstrom provides

reasonable grounds to believe that African-

Americans are politically cohesive and that

sufficient numbers of white citizens vote as a

block to defeat the candidate of choice of

AfLicausfingr ludny,

> (3) Defendants and defendant-intervenors

further contend that the plan is narrowly tailored

to remedy a possible Section 2 violation in that

the plan will remain in effect only until 2002, in

that the plan only creates two majority-minority

districts, in that the plan rreatas two districts

in which Afrjcan-Americans are only a bare

majAariby, fa yoy dhe plon de wabvhonxidl; buwud vi

legitimate non-racial redistricting criteria, in

that the plan fairly and legitimately balances

numerous competing legitimate criteria and in that

the plan causes no harm to white voters.

35

bt “d 65:91 . 66: SZ 140 £929914616: XES 111 "WIJ34S 99 ON

3. In addition to the foregoing contentions,

defendant -intervenors contend:

a. Each of the three Gingles requirements are

present:

(1) There is compelling evidence that

African-Americans are politically cohesive in

North Carolina.

(2) There is compelling evidence that white

votcro usually vote ap a bloc to defeat ths

candidate of choice of 2frigan-dmaricans.

(3) The population of African-Americans is

sufficiently large and geographically compact CTO

constitute majorities in two congressional

districts as evidenced by districting plans before

the General Assembly and as developed by the

parties in this litigation.

b. In addition to the three Gingles criteria, the

totality of the circumstances justifies the

state’s actions in enacting two majority-minority

districts: indeed such remedial action was

required because:

(1) there has been historic discrimination

in the electoral process in North Carolina,

luvludlyy vuuyLeasiunal Ledistcicring tho offeono

of which persist;

36

ord 00°21 66. SC ¥0 £9.991/616" XP 117 WIo3dsS 9g ON

(2) elections in North Carolina have been

stained by racial appeals, particularly when the

contest is between a white and African-American

candidate, practices which have continued into the

1590s.

(3) African-Americans in North Carolina

continue to exist at a severe socio-economic

disadvantage as compared to whites on every

conceivable measure such as income, housing,

AAT rSkwm; hoallll, ud su Ul. ley 48 Aus

disadvantaged in their ability to participate on

an equal basis in the political process.

(4) Prior to the redistricting which is the

subject of this case, African-Americans have met

or with defeat in every instance that they contested

for a Congressional seat in this century despite

energetic efforts by able, experienced candidates

who mounted serious campaigns. Each was able to

mobilize strong cohesive support in the African-

American community. Bach took his or her campaign

to the white community. And each was met with an

overwhelming white bloc vote which brought defeat.

27

wd 30:41 66..92 330 £9/991.616: Xe S 1171 1813345 93 IN

TIX. EXHIBITS

-- sole mh - ho

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Title

atm ul JU LlUil VilLam

202

203

204

205

208

207

208

208

210

ZF 4d 10:47 66: SC 330

of Stephen

An rrr ares dn mm. a —

Timothy O'Rourke

March 1984

speech to

Political

Scientists

Mary Brodgen

Affidavit

David Stradley

Declaration

John Sanders

Declaration

J. HK. Froelich,

Jr. Declaration

Philip Godwin

Declaration

Walter Jones,

Jr. Declaration

Karen Stewart

Letter

Sandra Grey

Herring Report

38

Objection

Hearsay

Hearsay

Hearsay, :

inadmissible opinion

Hearsay,

inadmissible opinion

Relevance, hearsay

Relevance, hearsay

£99914b16b: XE 1177 BIO3dS 98 ON

Exhibit 211 "White Mischief?" Relevance, hearsay

it The New

Republic,

December 10,

1990, pp. 9-10

B. Plaintiff-Intervenors

Number Title bijection

301 Notebook containing Map 11, 12, 14-16

Plaintiff Authenticity

Intervenarg, Mapa 1 -

23 with attached

explanations and

reports.

302 Large statewide map

of current

congressional

districts.

303 Large statewide map

of Shaw III plan.

304 Large map showiiy

ia outline of current

District 1.

208 Largc map showing

outline of current

District 12.

306 U.S. Geological

Survey maps

showing outline of

current

Distrior 1.

JV) U.S. La8ld8ical

Survey maps

showing outline of

current

District 12.

308 Large map showing

black

population

concentrations

in current District

— 1.

39

ld ZU.24T © 85, 5 390 £9L99TLBT18. AES LIT W113d5C "JN