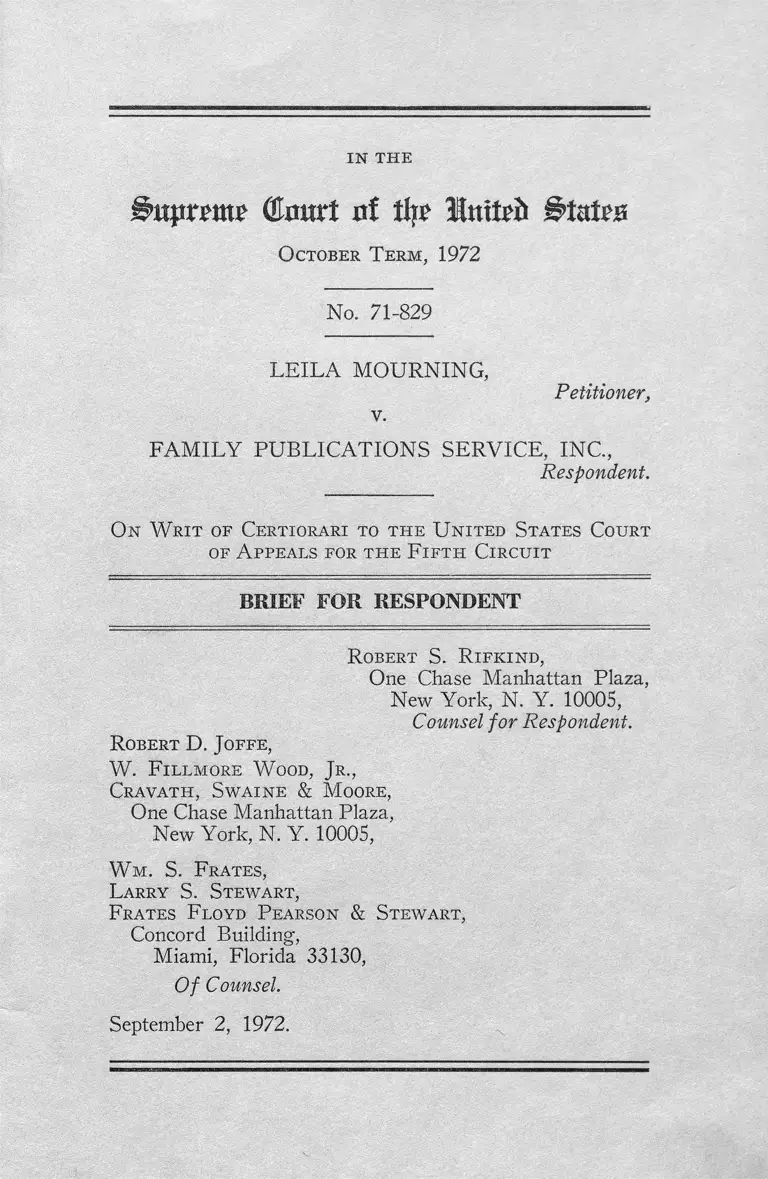

Mourning v. Family Publications Service, Inc. Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

September 2, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mourning v. Family Publications Service, Inc. Brief for Respondent, 1972. 3661ecde-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e5a90417-1a32-43ec-b1ee-dc89d6990539/mourning-v-family-publications-service-inc-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

IN TH E

&txpvm? (tort of % Initrfc

O ctober T e r m , 1972

No. 71-829

LE IL A MOURNING,

v.

Petitioner,

F A M ILY PU BLICATION S SERVICE, INC.,

Respondent.

O n W r it of C ertiorari to t h e U n ited States C ourt

of A ppeals for t h e F if t h C ir c u it

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

R obert S. R if k in d ,

One Chase Manhattan Plaza,

New York, N. Y. 10005,

Counsel fo r Respondent.

R obert D. Joffe ,

W . F illm o re W ood, Jr .,

Cr a v a t h , Sw a in e & M oore,

One Chase Manhattan Plaza,

New York, N. Y. 10005,

W m . S. F rates ,

L arry S. S te w a r t ,

F rates F loyd P earson & Ste w a r t ,

Concord Building,

Miami, Florida 33130,

O f Counsel.

September 2, 1972.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

O p in io n s B elow 1

Ju risd ictio n ...............................................

S tatu tes an d R egu lation s I nvolved

Q uestions P resented ............................

S t a t e m e n t of t h e Ca s e .....................

S u m m a r y of A r g u m e n t ..........................

A rg u m en t .....................................................

2

2

3

7

11

I. T h e C ourt B elow C orrectly H eld T h at

th e F our I n s t a l l m e n t R u le I s I n valid . . . 11

A. The rule is inconsistent with the A c t ........... 12

1. The statutory language............................ 12

2. The legislative h istory ............................ 17

B. The rule does not effectuate the purpose of

the Act nor does it prevent circumvention

or facilitate compliance ................................ 23

C. The four installment rule is an invalid ad

ministrative attempt to extend the Act

beyond its intended bounds.......................... 26

II. T he Ju dgm en t of th e Court of A ppeals

S hould B e Su stain ed on t h e G rounds, N ot

R eached B elo w , T h a t a C iv il P en a lty

U nder t h e A ct M a y N ot B e I mposed in the

A bsence of a F in a n c e C harge an d T h a t

FPS D id N ot E xten d C redit AVit h in th e

M e a n in g of t h e A c t ............................................ 32

A. The civil penalty provision o f the Act is in

applicable in the absence o f a finance charge 33

B. FPS did not extend cred it............................ 36

Co n clu sio n ............................................................................. 44

A p p e n d ix .................................................................................. l a

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Cases :

Addison v. Holly Hill Fruit Products, Inc., 322 U. S.

607 (1944) ................................................................ 29

American Airlines, Inc. v. CAB, 365 F. 2d 939

(D . C. Cir. 1966) ................................................ 19

Bostivick v. Cohen, 319 F. Supp. 875 (N. D. Ohio

1970) ........................................................................... 22

Bowers v. Dr. P. Phillips Co., 100 Fla. 695, 129 So.

850 (1930) ................................................................ 42

Burton v. Bowers, 172 F. 2d 429 ( 4th Cir. 1949) . . 40

Casteneda v. Family Publications Service, 4 CCH

C onsum er Credit G u ide f[ 99,564 (D . Colo.

1971) ................................................... 22

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission v. Con

tinental A ir Lines, Inc., 372 U. S. 714 (1963) . . 33

Commissioner v. Acker, 361 U. S. 87 (1959) 7 ,9,29,

30, 35

Duplex Printing Press Co. v. Deering, 254 U. S

443 (1921) ................................................................ 19

Ebert v. Poston, 266 U. S. 548 (1925) ................ 17

Esposito v. Nayer, Civil No. 11-142 (D. Me., Tune

5 ,1 9 7 2 ) ........................................................................... 22

Evans v. Kroh, 284 S. W. 2d 329 (Ky. Ct. App.

1955) .......................................................................... 40

. Farley Realty Corp. v. Commissioner, 279 F. 2d

701 (2d Cir. 1960) ................................................. 40

Federal Communications Commission v. American

Broadcasting Co., 347 U. S. 284 (1954) 9, 27, 28, 29

Fibreboard Paper Products Corp., v NLRB 379

U. S. 203 (1 9 6 4 ) ................... ................................. 32

Ill

Garland v. Mobil Oil Corp., 4 CCH C onsum er

Credit G u ide jf99,193 (N. D. 111. 1972) . . . .22,43

Gemsco, Inc. v. Walling, 324 U. S. 244 (1945) . . . 32

Gilbert v. Commissioner, 248 F. 2d 399 (2d Cir.

1957) ......................................................................... 39

Gilman v. Commissioner, 53 F. 2d 47 ( 8th Cir.

1931) .......................................................................... 40

Hatfield, Inc. v. Commissioner, 162 F. 2d 628 (3d

Cir. 1947) .................................................................. 35

Helverinq v. Credit Alliance Corp., 316 U. S. 107

(1942) ........................................................................ 30

Helwig v. United States, 188 U. S. 605 (1903) . . . . 35

Jamison v. United States, 297 F. Supp. 221 (N. D.

Cal. 1968), aff’d per curiam, 445 F. 2d 1397 (9th

Cir. 1971) .................................................................. 40

Jaramillo v. McLoy, 263 F. Supp. 870 (D. Colo.

1967) ........................................................................ .. 40

John Kelley Co. v. Commissioner, 326 U. S. 521

(1946) ........................................................................ 41

Keppel v. Tiffin Savings Bank, 197 U. S. 356

(1905) ....................................................................... 29,35

Langnes v. Green, 282 U. S. 531 (1931) . . ........ 9, 33

Le Tulle v. Scofield, 308 U. S. 415 (1 9 4 0 ) ............ . 33

Martinez v. Family Publications Service, Inc., No.

71-169-Civ-TC (S . D. Fla., Oct. 12, 1971) . . . . 22

McGee v. Stocked Heirs at Law, 76 N. W . 2d 145

(N. D. 1956) ........................................................... 40

Metropolitan Water District v. Marquardt, 59 Cal.

2d 159, 379 P. 2d 28, 28 Cal. Rptr.724 (1963) , . 41

Miller v. United States, 294 U. S. 435 (1935) 9, 30, 31

National Broadcasting Co. v. United States, 319

U. S. 190 (1943) .'.................... 32

Nicholas v. Denver & R. G. W. R. R., 195 F. 2d

428 (10th Cir. 1952) ............................................

PAGE

19

IV

North American Co. v. SEC, 327 U. S. 686 (1946 ) 33

Otis v. Cowles Communications, Inc., No. C-71-550

RHS (N. D. Cal., Nov. 3, 1971) ....................... 22

Park & 46th St. Corp. v. State Tax Commission

295 N. Y. 173, 65 N. E. 2d 763 (1 9 4 6 ) ............... 40

Ratner v. Chemical Bank New York Trust Co., 329

F. Supp. 270 (S. D. N. Y. 1971) ....................... 13, 35

Sherzvood Memorial Gardens, Inc. v. Commissioner,

350 F. 2d 225 (7th Cir. 1965) .............................. 39

State v. Smith, 335 Mo. 825, 74 S. W. 2d 367

(1934) ........................................................................ 40

Strompolos v. Premium Readers Service, 326 F.

Supp. 1100 (N. D. 111. 1971), certified under 28

U. S. C. \1292 (b ), settled on appeal............... 22

Sunshine Anthracite Coal Co. v. Adkins, 310 U. S.

381 (1940) ................................................ 27

Thorpe v. Housing Authority, 393 U. S. 268 (1969) 32

United States v. American Railway Express Co.,

265 U. S. 425 (1924) ............................................. 33

United States v. Calamaro, 354 U. S. 351 (1957) . . 30

United States v. Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and

Pacific R .R ., 282 U. S. 311 (1 9 3 1 ) ..................... 27

United States v. Foster, 233 U. S. 515 (1914) . . . . 32

United States v. International Union United Auto-

mobile, Aircraft & Agricultural Implement Work

ers o f America, 352 U. S. 567 (1 9 5 7 ) ................. 19

United States v. New York, New Haven and Hart

ford R. R., 276 F. 2d 525 (2d Cir. 1959), cert.

denied, 362 U. S. 961, 964 (1 9 6 0 ) ....................... 40

United States v. United Mine Workers o f America

330 U. S. 258 (1 9 4 7 ) ........................................... 35

Walla Walla City v. Walla Walla Water Co. 172

U .S .l (1 8 9 8 ) .........................................................40,41

Westfall v. United States, 274 U. S. 256 (1927) . . 33

Zuber v. Allen, 396 U. S. 168 (1 9 6 9 ) ..................... 30

PAGE

V

St a t u t e s :

PAGE

15 U. S. C. § 1601 (1970) .................................. 12,13,16

15 U. S. C. § 1602 (1970) 4, 8, 10,11, 12, 13, 19, 35, 39

15 U. S. C. § 1603 (1970) ................................ 16

15 U .S .C .§ 1604 (1970) ................................,4 ,7 ,9 ,1 6

15 U. S. C. § 1607 (1970) .............................. 34

15 U. S. C. § 1611 (1970) ......................................... 4

15 U .S .C .§ 1612 (1970) ....................................... 25,35

1 5 U .S .C . § 1631 (1970) ........................ 4 ,8 ,11 ,12 ,13

15 U .S .C . § 1638 (1970) ...................................4 ,13 ,17

15 U. S. C. § 1640 (1970) 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13. 25, 33,

34, 35

28 U. S. C. § 1254 (1970) ........................................... 2

Fla. Stat. §§ 672.2-612, 672.2-711, 672.2-717 (1969) 42

R egu lation s :

12 C .F .R .§ 226.2 (1 9 7 2 ) ......................... 4 ,6 ,7 ,1 1 ,1 4

12 C. F. R. §226.4 (1972) ......................................... 43

12 C. F. R. § 226.5 (1972) .............................. 23

12 C. F. R. §226.6 (1972) . .............................. 17

12 C. F. R. § 226.8 (1 9 7 2 ) ........................................ 4, 14

C ongressional M a te r ia l :

C o n f . R e p . N o. 1397, 90th Cong., 2d Sess. (1968) 17

114 Cong . R e p . 14487 (1 9 6 8 ) .................................. 39

Hearings on S. 1740 Before a Subcomm. of the

Senate Comm, on Banking and Currency, 87th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1961) ........................... .......... 19, 20

VI

Hearings on S. 750 Before the Suhcomm. on Pro

duction and Stabilisation of the Senate Comm, on

Banking and Currency, 88th Cong., 1st & 2nd

Sess. (1964) ..................................................... . . .20, 21

Hearings on S. 5 B ef ore the Subcomm. on Financial

Institutions of the Senate Comm, on Banking and

Currency, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. (1 9 6 7 )___ 19. 21, 34

Hearings on H. R. 11601 Before the Subcomm. on

Consumer Affairs o f the House Comm, on Bank

ing and Currency, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. (1967) . . 20

H. R. R e p . N o . 1040, 90th Cong., 1st Sess.

PAGE

(1967) ................... ....................................18,22,35,39

S. 5, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. (1967) ..................... .. 18, 19

S. 652, 92nd Cong., 2d Sess. (1972) ........................ 7

S. R e p . N o. 392, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. (1967). .18, 19,

22, 39

B ooks and M isc e lla n e o u s :

3A A. C orbin , C ontracts §§ 687, 691 (1960) . . 10, 36,

37,42

5 J. Mertens, T he Law of Federal Income Tax

ation § 30.03 n.29 (1969) .................................. 41

4 FRB Letter No. 262, CCFI C on su m er Credit

G u ide jf- 30,516 (1970) ........................................ 10,38

IN TH E

Bnpmiw (tart rrf tljr United l̂ tatr̂

O ctober T erm , 1972

No. 71-829

L e il a M o u r n in g ,

Petitioner,

v.

F a m il y P u b lic a tio n s Service , I n c .,

Respondent.

O n W r it of C ertiorari to t h e U nited S tates C ourt

of A ppeals for th e F if t h C ir c u it

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Florida (App. 32-35) is reported at

4 CCH Consumer Credit Guide 99,632 (1970)

(Mehrtens, J.). The opinion of the United States Court

o f Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (App. 40-54), reversing

the decision of the District Court, is reported at 449 F. 2d

235 (1971).

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered on

September 27, 1971 (App. 54). The petition for a writ of

2

certiorari was filed on December 23, 1971, and granted on

March 20, 19/2 (App. 55, 405 U. S. 987). The jurisdic

tion of the Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. § 1254(1).

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS INVOLVED

The statute to be construed is the Truth in Lending Act,

15 U. S. C. §§ 1601-65 (1970). The regulation in issue

is to be found in Regulation Z, 12 C. F. R. §§ 226.1-.13

(1972), promulgated by the Federal Reserve Board. The

relevant provisions of the Act and o f Regulation Z are

set forth in an Appendix to this brief, infra.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The Truth in Lending Act provides that “ creditors”

who regularly extend credit “ for which the payment of a

finance charge is required” (15 U. S. C. § 160 2 (f)) shall

disclose the amount of the finance charge and other specified

information in transactions which entail a finance charge

(15 U. S. C. § 1631 (a ) ) . For failure to make the statutory

disclosures, the Act imposes civil penalties (15 U. S. C.

§ 1640(a)) upon creditors in an amount equal to “ twice

the amount o f the finance charge in connection with the

transaction, except . . . [not] less than $100 nor greater

than $1,000. . . .” The four installment rule of Regulation

Z promulgated by the Federal Reserve Board provides that

the required disclosures must be made in credit transactions

involving repayment in more than four installments, regard

less of whether a finance charge is entailed (12 C. F. R.

§§ 226.2(k ), (m ) and (bb), 226 .8(a)).

The questions presented by this case are:

1. Whether the court below erred in holding that

the Federal Reserve Board acted in excess of its author

ity under the Truth in Lending Act in promulgating the

four installment rule of Regulation Z.

3

2. Whether a civil penalty may be imposed under

15 U. S. C. § 1640(a) in connection with a transaction

that does not involve a finance charge.

3. Whether transactions in which consumers pre

pay for goods involve an extension of credit within the

meaning of the Truth in Lending Act.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Respondent, Family Publications Service, Inc. ( “ FPS” ),

was engaged in the business o f offering subscriptions to a

large number of magazines on what is commonly known

as a paid-during-service ( “ P-D -S” ) basis.* As is common

under P-D-S plans, FPS’s standard form of contract pro

vides for the delivery of the magazines selected by the cus

tomer over 48 (or 60) months, for which the customer pays

on a monthly basis over the first 24 (or 30) months.**

Under this plan, at every point in time prior to the end of

the contract period, the customer has paid for more issues

than he has received so that the payments are in fact pre

payments by the customer for magazines to be delivered

to the customer in the future (App. 41).

Under the terms of the FPS contract executed by peti

tioner on August 19, 1969, she was to receive Ladies Home

Journal, Holiday, Life, and Travel and Camera for 60

months in return for an initial payment of $3.95 and 30

monthly payments of $3.95 (App. 41). Although she re

ceived the magazines ordered, petitioner defaulted on her

contract and never made any payments beyond the initial

*FPS was engaged in the P-D-S magazine sales business from

the date of its incorporation in 1958 until it terminated selling opera

tions in February 1971.

**In a relatively small number of cases FPS ’s customers elected

to pay the full purchase price at the outset rather than over 24

(or 30) months. Subsequent to the proceedings below we have

discovered that, contrary to representations made below, a small

number of those customers (representing a small fraction of 1%

of FPS’s total customers) may have been charged less than the

aggregate purchase price under FPS’s standard form of contract.

4

$3.95 payment. Consequently, her contract was cancelled

by FPS on April 15, 1970 (App. 41-42).

Petitioner Mourning commenced this action in the

United States District Court for the Southern District of

Florida on April 23, 1970, on her own behalf and on behalf

of a class comprised o f all residents of Dade County,

Florida, who had entered into contracts with FPS since

July 1, 1969 (the effective date of the Truth in Lending

Act). The second amended complaint ( “ the complaint” )

alleged that the FPS standard form contract did not contain

the disclosure o f credit terms required by the Truth in

Lending Act and the regulations promulgated by the

Federal Reserve Board ( “ the Board” ). The com

plaint prayed for a civil penalty of not less than $100 nor

more than $1,000 on behalf of each member of the class,

together with attorneys’ fees and the cost o f the action,

as provided for in 15 U. S. C. § 1640(a) (App. 2-5).

The Act provides that creditors who regularly extend

consumer credit “ for which the payment of a finance charge

is required” (15 U. S. C. § 1602 (f)) shall make specified

disclosures (15 U. S. C. § 1631(a)), including the amount

o f the finance charge and the finance charge expressed as an

annual percentage rate (15 U. S. C. § 1638(a) (6 ) - (7 ) ).

Regulation Z promulgated by the Board provides that

such disclosures must be made in credit transactions

involving repayment in more than four installments, re

gardless of whether a finance charge is involved (12 C. F. R.

§§ 226.2(k ), (m ) and (bb), 226.8(a)). For failure to make

the required disclosures, the Act imposes both criminal (15

U. S. C. § 1611) and civil penalties (15 U. S. C. § 1640(a) ),

as well as administrative sanctions under the Federal Trade

Commission Act (15 U. S. C. § 1607(c ) ). The civil penalty

section of the Act under which petitioner’s claim arises, pro

vides that

“any creditor who fails in connection with any con

sumer credit transaction to disclose to any person

5

any information required under this part to be dis

closed to that person is liable to that person in an

amount equal to the sum of

“ ( 1) twice the amount of the finance charge

in connection with the transaction, except that the

liability under this paragraph shall not be less than

$100 nor greater than $1,000 . . . 15 U. S. C.

§ 1640(a).

On August 28, 1970, both parties moved for summary

judgment. Petitioner contended that her transaction with

FPS was subject to the Act solely by virtue of Regulation Z

because it was a credit transaction payable in more than

four installments and that she was entitled to recover a civil

penalty regardless of whether the transaction entailed a

finance charge. Petitioner asserted that the absence of a

finance charge was irrelevant— since none was required

under the four installment rule. (Plaintiff’s Memorandum

in Opposition to Defendant’s Motion for Summary Judg

ment at 5.) FPS contended that the transaction was not

subject to the disclosure and penalty provisions of the Act

because, inter alia, ( 1) it was not a credit transaction, ( 2)

the disclosure and penalty provisions of the Act do not

apply in the absence of a finance charge, and (3 ) the Regu

lation could not properly extend the scope of the Act. Both

parties concurred in the view that there were no material

issues of fact and that the question to be decided was the

proper reach of the disclosure and penalty provisions of the

Act and the Regulation.

On November 27, 1970, the district court rendered its

final decision ( 1) dismissing the class action allegations in

the complaint, (2 ) denying FPS’s motion for summary

judgment, and (3 ) granting judgment in favor of peti

tioner in the amount of $100, together with $1,500 attor-

6

ney’s fee and costs. The court held that “ the transaction

here in question falls squarely within the scope of the Act

and its Regulations by virtue o f the ‘more than four install

ments’ rule, 12 C. F. R, § 226.2(k). . . (App. 34) (em

phasis added).

On December 11, 1970, FPS filed a notice of appeal

from the district court’s order and from the judgment

entered thereon in so far as the order granted plaintiff’s mo

tion for summary judgment and denied FPS’s motion for

summary judgment.

On September 27, 1971, the court of appeals held the

four installment rule invalid and reversed and remanded

with directions that the complaint be dismissed. The court

found that under the Act “ three essential elements must be

found present together in a transaction” before the duty to

make the specified disclosures arises: (i) a creditor (ii)

who extends consumer credit (iii) in a transaction which

entails a finance charge (App. 49). The court also found,

in accord with the position taken by the United States as

amicus curiae, that under the Board’s Regulation,

“ in order for the disclosure and penalty provisions

of the Truth-in-Lending Act to be applicable, all

that is required is that the transaction involve the

extension of credit which, pursuant to agreement, is

or may be payable in more than four installments.

No showing or finding of the imposition, directly or

indirectly, of a finance charge is necessarily re

quired.” (App. SO.)

The court concluded that “an inconsistency exists be

tween the four installment rule and the Truth-in-Lending

Act” (App. 50) and that, in promulgating the rule, the

Board had “ over-stepped the authority granted to them

7

under 15 U. S. C. § 1604.” (App. 51.) Relying on this

Court’s decisions in Commissioner v. Acker, 361 U. S. 87

(1959), and similar cases, the court o f appeals held that

the Board’s rule constituted an invalid “ administrative en

deavor to amend the law as enacted by the Congress and to

thereby make the Act reach transactions which the Con

gress by its statutory language did not seek or intend to

cover by its enactment.” (App. 51.)*

Having found the Act inapplicable to the transaction in

issue by reason of the invalidity of the four installment rule,

the court o f appeals- did not find it necessary to consider

FPS’s further contentions (1 ) that the civil penalty provi

sion of the Act, providing for a penalty equal to “ twice the

amount of the finance charge” imposed, is inapplicable

where the transaction in question does not involve a finance

charge, and (2 ) that the Act is inapplicable because FPS did

not extend consumer credit but rather was prepaid by its

customers.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

The court of appeals correctly held that the four in

stallment rule o f Regulation Z, 12 C. F. R. § 226.2(k), is an

invalid attempt by the Federal Reserve Board to bring

within the ambit of the Truth in Lending Act, 15 U. S. C.

§§ 1601-65 (1970), transactions which Congress has ex

plicitly put beyond the scope of the Act. The Act imposes

*The court of appeals also held the Board’s four installment rule

invalid as constituting a conclusive presumption violative of the due

process clause of the Fifth Amendment. W e do not believe that it is

necessary to reach this constitutional ground and we do not rely on

it. W e concur in the view expressed by petitioner that Congress

could have enacted the four installment rule without violating the due

process clause. A bill intended to accomplish that result was passed

by the Senate on April 27, 1972, and is currently before the Con

sumer Affairs Subcommittee of the House Banking and Currency

Committee. S. 652, 92nd Cong., 2nd Sess.

8

certain requirements o f disclosure upon creditors. The term

“ creditor” is defined to include “ only [those] creditors who

regularly extend . . . credit for which the payment of a fi

nance charge is required . . . IS U. S. C. § 1602(f)

(emphasis added). Such creditors are required to disclose

specified information relating to the cost of credit “ to each

person . . . upon whom a finance charge is or may be im

posed . . . .” IS U. S. C. § 1631(a). Finally, under Section

1640(a), such creditors are liable for a civil penalty in an

amount equal to “ twice the amount of the finance charge in

connection with the transaction, except . . . [not] less than

$100 nor greater than $1,000 . . . .” 15 U. S. C. § 1640(a).

Notwithstanding the congressional decision to require

the statutory disclosures only in connection with credit

transactions involving a finance charge, Regulation Z pur

ports to require such disclosures in connection with credit

transactions repayable in more than four installments re

gardless of whether a finance charge is imposed. Petitioner’s

claim against FPS is based solely on the four installment

rule, and petitioner concedes that the transaction in issue is

not subject to the substantive provisions of the Act which

require the presence of a finance charge. The four install

ment rule is invalid because it is in conflict with the inten

tion of Congress as manifested by the language of the Act

and the legislative history. The congressional committee re

ports make it particularly clear that Congress intended that

the disclosure requirements of the Act be limited to transac

tions involving finance charges. A bill pending before Con

gress was amended expressly for the purpose of making

clear that the disclosure requirements would not apply to

transactions in which a finance charge is not involved.

Although petitioner and the Government argue that the

four installment rule is necessary to effectuate the purpose

o f the Act and prevent circumvention of the Act, in fact it

does neither. In particular, it does not solve the problem

9

presented by the buried or hard-to-find. finance charge. The

Government’s thesis that creditors subject to the Act may

satisfy their statutory obligations merely by disclosing total

price without separately identifying the cost o f credit is

without warrant in either the Act or the Regulation and is

subversive of the statutory purpose.

The conclusion reached by the court of appeals that the

Board, in promulgating the four installment rule, “ over

stepped the authority granted to them under 15 U. S. C.

§ 1604” (App. 51) is clearly supported by the decisions

of this Court. See, e.g., Commissioner v. Acker, 361 U. S.

87 (1959) ; Federal Communications Commission v. Amer

ican Broadcasting Co., Inc., 347 U. S. 284 (1954) ; Miller

v. United States, 294 U. S. 435 (1935).

II.

The judgment of the court of appeals is sustained by

two independent considerations that were advanced by

FPS below but which the court of appeals did not find it

necessary to reach. See Langnes v. Green, 282 U. S. 531

(1931).

First, whether or not the disclosure requirements and

the administrative enforcement provisions of the Act are

applicable in the absence of a finance charge, the civil lia

bility provision, under which petitioner’s claim arises, is

inapplicable. That section (15 U. S. C. § 1640(a)) spe

cifies liability in an amount equal to “ twice the amount of

the finance charge in connection with the transaction, ex

cept that the liability . . . shall not be less than $100 nor

greater that $1,000 . . . .” The finance charge provides the

initial measure of the award. The minimum and maximum

dollar amounts cannot reasonably be construed as providing

an alternative means of determining the amount of an

award in the absence of a finance charge because the

10

language of Section 1640(a) is not susceptible o f an

“ either/or” interpretation. Indeed, Congress rejected a

bill which provided for liability in the alternative.

Second, the disclosure and civil penalty provisions of

the Truth in Lending Act apply only to credit transactions.

The Act is inapplicable to the transaction in question for

the fundamental reason that the transaction did not involve

the extension of credit by FPS to petitioner. It is the es

sence of a credit transaction that one party parts with value

in reliance on the promise o f another to pay at a later date.

Under the standard FPS contract, however, FPS does not

deliver anything in advance of payment. Quite the con

trary, the customer pays in advance for the subsequent

receipt of magazines. Nor does the fact that the customer

contracts to make periodic payments turn his obligation into

a credit obligation. “ A transaction may be an instalment

contract without being a credit transaction at all.” 3A A.

Co rbin , C ontracts § 687 (1960). The Board has form

ally recognized that an agreement to pay in installments for

goods or services to be rendered in installments does not

involve an extension o f credit within the meaning of the

Act unless the payments lag behind delivery o f the goods

or services. FRB Opinion Letter No. 262 (1970).

The Act adopts the common understanding of a credit

transaction and defines the term “ credit” as “ the right

granted by a creditor to a debtor . . . to incur debt and defer

its payment.” IS U. S. C. § 1602(e). A debt results from

an unconditional agreement to pay and is to be distin

guished from the obligations of a contract under which the

performance of both parties lies in the future. Here, there

is clearly no “ debt” within the meaning of the Act. Peti

tioner s obligation to pay was contingent on performance

by FPS.

11

ARGUMENT

FOUNT I

THE COURT BELOW CORRECTLY HELD TH AT THE

FOUR INSTALLMENT RULE IS INVALID.

Petitioner and the Government urge that the Fifth Cir

cuit erred in holding invalid the four installment rule of

Regulation Z, 12 C. F. R. § 226.2(k ). The court of appeals

held the rule invalid because it purported to bring transac

tions which do not entail a finance charge within the dis

closure and penalty provisions of the Act, whereas the Act

explicitly excludes such transactions from its coverage.

The court of appeals was clearly correct in concluding

that the four installment rule is inconsistent with the Act

and is therefore invalid. As is set forth below, three key

sections in the Act (15 U. S. C. §§ 1602(f), 1631(a) and

1640(a)) as well as the legislative history of the Act make

plain that the Act applies only to transactions that entail a

finance charge. On the other hand, the four installment rule

dispenses with that prerequisite by providing that transac

tions involving payment in more than four installments are

subject to the Act’s disclosure and penalty provisions

whether or not they entail a finance charge.

There is no dispute that the Regulation eliminates the

finance charge requirement imposed by the Act. Petitioner

concedes that “ the transaction [in issue] is not covered by

the substantive provisions of the statute” and that, in the

absence of the Regulation, FPS would not be subject to the

disclosure requirements of the Act. Pet. Br. 11. What is

in dispute is the validity of the Regulation.

Further, contrary to the impression created by the briefs

o f petitioner and amici, we are not concerned here with

whether transactions involving hidden or buried finance

charges are subject to the requirements of the Act. It is not

disputed that such transactions are subject to the Act with-

12

out assistance from the Regulation. Indeed, the fun

damental purpose of the Truth in Lending Act was to re

quire disclosure of concealed finance charges. The question

presented here is whether transactions which the Act does

not reach because they do not entail finance charges may

nonetheless he brought within the Act’s ambit by the

Regulation.

A. The rule is inconsistent with the Act.

1. The statutory language.

The Act is neither silent nor ambiguous with respect

to the scope of its coverage. Three separate sections of the

Act reiterate that the disclosure and penalty provisions

apply only to those creditors who impose a finance charge.

Section 1602(f) provides in applicable part:

“ The term ‘creditor’ refers only to creditors who

regularly extend, or arrange for the extension of,

credit for which the payment of a finance charge

is required (Emphasis added.)

This definition makes it clear that, contrary to the Govern

ment’s view (U. S. Br. 15-17, 20), Congress assumed that

there are creditors who do not impose finance charges as

well as those who do. Consistent with the declared statu

tory purpose to assure “ [t]he informed use of credit

[which] results from an awareness of the cost thereof”

(15 U. S. C. § 1601) (emphasis added), the Act was

directed at those who impose a finance charge.

The point is re-emphasized in the general disclosure

requirement set forth in § 1631(a) which provides:

“ Each creditor [as defined in § 1602(f)] shall

disclose clearly and conspicuously, in accordance

with the regulations of the Board, to each person

to whom consumer credit is extended and upon

13

whom a finance charge is or may be imposed, the

information required under this part.” (Emphasis

added.) *

The required information includes “ the amount o f the fi

nance charge” and “ the finance charge expressed as an an

nual percentage rate” (15 U .S.C . § 1638(a)(6 ) and ( 7 ) ) .

Finally, under § 1640(a), the civil liability for failing to

make the required disclosures is imposed only on “ creditors”

and is stated to be “ twice the amount o f the finance charge

in connection with the transaction” (emphasis added), ex

cept that such liability shall not be less than $100 nor more

than $1,000. In sum, the Act is addressed only to those

creditors who regularly impose a finance charge; such credi

tors are required to disclose the finance charge to each con

sumer upon whom a finance charge is or may be imposed;

and the civil penalty for failing to comply is measured by

the amount of the finance charge in connection with the

transaction. It would be hard to imagine a more explicit

insistence on a limitation o f the Act to situations involving

a finance charge. All o f those limiting phrases would be

inexplicable had Congress intended the Act to apply regard

less of whether a finance charge was involved.

^Contrary to petitioner’s statement that if a creditor “ regularly”

(15 U. S. C. § 1602(f)) imposes a finance charge “ he must make the

required disclosures in all of his credit transactions whether or not

they involve a finance charge” (Pet. Br. 12), a creditor need make

the required disclosures in only those transactions in which a charge

“ is” imposed or “ may be” imposed (15 U. S. C. § 1631(a)), as upon

the happening of a specified event ( e . g the failure to pay. within

30 days). The Act provides that the word “ ‘may’ is used to indicate

that an action either is authorized or is permitted.” 15 U. S. C.

■ § 1601 note at 3439; Pub. L. No. 90-321, § 503 (May 29, 1968). See,

e.g., Rainer v. Chemical Bank New York Trust Co., 329 F. Supp.

270, 273 (S. D. N. Y. 1971). Such transactions are herein referred

to as entailing a finance charge. In any event, it is petitioner’s

contention that FPS is subject to the disclosure provisions of the

Act solely by virtue of the four installment rule— irrespective of

whether its transactions entail a finance charge.

14

Notwithstanding these manifestations o f legislative

purpose, the Board eliminated the Act’s prerequisite o f a

finance charge. Regulation Z specifies the duties of a

“ creditor” (12 C. F. R. § 226 .8 (a )), and defines “ creditor”

as a person who regularly extends “ consumer credit” (12

C. F. R. § 226.2 (m )) . It is the Board’s definition of

“ consumer credit” that establishes the four installment rule:

“ Consumer credit means credit offered or ex

tended to a natural person, in which the money,

property, or service which is the subject o f the

transaction is primarily for personal, family, house

hold, or agricultural purposes and for which either

a finance charge is or may be imposed or which

pursuant to an agreement, is or may be payable in

more than four installments.” 12 C. F. R. § 226.2

(k) (emphasis added).

That the four installment rule seeks to expand the

coverage o f the Act is not disputed. The district court

found FPS’s transactions subject to the disclosure and

civil penalty provisions of the Act solely “by virtue of the

‘more than four installments’ rule” (App. 34-35).* Peti

tioner recognizes that “ the transaction is not covered by

the substantive provisions of the statute” (Pet. Br. 11),

and acknowledges here, as she did below, that the case

against FPS turns on the validity of the four installment

rule. She urges that the Board has “ the power to

reach transactions just outside the literal reach of the

*Petitioner maintained in the district court: “ Defendant has

denied any finance charge and the point is not an issue here.”

Plaintiff’s Memorandum in Opposition to Defendant’s Motion for

Summary Judgment at 5. The court of appeals noted that the

district court had not found a finance charge present and had relied

on the four installment rule for its holding that FPS was subject

to the disclosure and penalty provisions of the Act. (App. 45.)

15

statute” (Pet. 15) and to “go beyond the literal disclosure

requirements of the Act.” (Pet. Br. 8.)

Likewise, the Government recognizes, albeit grudgingly,

that the four installment rule may reach “ credit transactions

that the provisions of the Act themselves might not cover

because there are in fact no finance charges involved

directly or indirectly” (U. S. Br. 9 ) ; it urges that the Board

had authority to promulgate a rule which “embraces some

transactions that the provisions o f the Act might not, on

their face, reach” (U . S. Br. 24).* A variety of arguments

based on policy are advanced in support o f the Board’s

action. W e show below that those supposed policy con

siderations will not bear scrutiny and that the rule is in

fact subversive of the purposes of the Act. First, however,

we turn to petitioner’s contention that the rule is not in con

flict with the Act but merely serves to elaborate upon it.

It is petitioner’s fundamental contention that:

“ The failure of Congress to include the instant

transaction within those substantive provisions does

not demonstrate any congressional intent to exempt

the transaction from disclosures, but only an intent

to leave regulation of the transaction to the Board.”

Pet. Br. 9.

This position is clearly unsound. It was easy enough for

Congress to make the Act applicable to all creditors had it

intended to do so. It did not do so. It specifically limited the

*To be sure, the Government also urges that Congress assumed

that “ whenever credit is extended the costs necessarily incurred by

the creditor are in fact passed on to the consumer” (U. S. Br. 9

n.10). As we have noted above, however, the statutory definition of

creditor as “ only [those] creditors who regularly extend . . . credit

for which the payment of a finance charge is required” is consistent

only with the view that some creditors do not impose a finance

charge. Moreover, as we show below, the legislative history simply

does not bear out the Government’s speculations as to Congress’s

assumptions.

16

scope of the Act to creditors who impose a finance charge

and to transactions involving a finance charge. Futhermore,

the explicit limitation of the requirements of the Act to

finance charge transactions cannot rationally be said to

manifest, “ an intent to leave regulation of [all other trans

actions] to the Board.” Plaintiff’s thesis would lead to the

conclusion that the Board is authorized to regulate every

thing not dealt with by Congress.

Also unsound is petitioner’s contention (Pet. Br. 28)

that transactions not involving a finance charge are not ex

empted by the Act but “ merely omitted from coverage” be

cause they are not among the “ exempted transactions” (,e.g

commercial credit, securities transactions) listed in 15

U. S. C. § 1603. Obviously, there was no need to exempt

transactions not involving a finance charge because they

were not covered in the first place.

In the same vein, petitioner urges (Pet. Br. 20-21)

that, if the Act contained only its declaration o f purpose

(15 U. S. C. § 1601) and the provision authorizing the

Board to issue regulations to carry out that purpose (15

U. S. C. § 1604), the four installment rule would have been

entirely appropriate. Petitioner then goes on to argue, in

substance, that nothing in the remaining 30 sections of

the Act should be deemed to curtail that grant of authority.

Congress, however, did not see fit to pass only a declaration

o f purpose and a grant of rulemaking authority. It did pass

the rest of the Act, and the Board cannot proceed as if

Congress had been silent.

The freewheeling administrative power, advocated by

petitioner, to “ correct any [congressional] oversights or

omissions” (Pet. 13) and to alter the “ lines drawn by the

statute itself” (Pet. Br. 18) is peculiarly inappropriate in

the circumstances of the Truth in Lending Act. Contrary

to petitioner’s assertion, the Act is not a mere “ rough out

line” (Pet. 13) of what Congress had in mind. Congress

17

did not merely state a broad area of concern and direct

the Board to deal with it. Rather, Congress hammered out

a detailed system of regulation, setting forth with preci

sion the matters within its coverage.* “ Such care and par

ticularity in treatment preclude expansion o f the Act in

order to include transactions supposed to be within its

spirit, but which do not fall within any of its provisions.”

Ebert v. Poston, 266 U. S. 548, 554 (1925). To be sure,

the Board was called upon to provide supplementary regu

lations,** but it was not left at liberty to reshape the Act

or to revise congressional decisions.

2. The legislative history.

The legislative history of the Act demonstrates that the

plain statutory language is not the result of legislative in

advertence or oversight but was the result o f an affirmative

congressional decision to restrict the Act’s coverage to trans

actions involving a finance charge. Thus, the Senate-House

conference report states that the Act was designed “ to assist

in the promotion of economic stabilization by requiring the

disclosure of finance charges in connection with extension

of credit. . . .” C o n f . R e p . No. 1397, 90th Cong., 2d Sess.

at 1 (1968) (emphasis added). Further, the Senate Report

states:

“ [Section 1631] . . . is a prefatory section setting

forth the basic requirements to disclose. It is similar

*For example, § 1638(a)(7) provides for the disclosure of

“ The finance charge expressed as an annual percentage

rate except in the case of a finance charge

(A ) which does not exceed $5 and is applicable to an

amount financed not exceeding $75, or

(B ) which does not exceed $7.50 and is applicable to

an amount financed exceeding $75.

A creditor may not divide a consumer credit sale into two or

more sales to avoid the disclosure of an annual percentage rate

pursuant to this paragraph.”

**See, for example, 12 C. F. R. §§ 226.6(d), 226.6(j).

18

to the original S. 5, except that it is made clear that

disclosure need only be made to persons ‘upon whom

a finance charge is or may be imposed’. Thus, the

disclosure requirement would not apply to transac

tions which are not commonly thought of as credit

transactions, including trade credit, open account

credit, 30-, 60-, or 90-day credit, etc., for which a

charge is not made.” S. R e p . N o . 392, 90th Cong.,

1st Sess. 14 (1967). The House Report is substan

tially identical. H. R . R e p . N o . 1040, 90th Cong.,

1st Sess. 25 (1967).

The Senate Report also states that “ [tjhe basic pur

pose of the truth in lending bill is to provide a full dis

closure of credit charges to the American consumer.” S.

R e p . N o . 392, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. at 1 (1967) (emphasis

added). The same intent is reflected in the House Report;

“ Title I is intended to provide the American con

sumer with truth-in-lending and truth-in-credit ad

vertising by providing full disclosure of the terms

and conditions of finance charges both in credit

transactions and in offers to extend credit.” H. R.

R e p . N o . 1040, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. 6-7 (1967)

(emphasis added).

The Government’s brief seeks to undermine the signifi

cance of the committee reports by reference to a variety of

random statements at various hearings with respect, for the

most part, to bills significantly different from the one ulti

mately enacted.* If those statements were in conflict with

*Many of the statements cited by the Government {see, e.g., U. S.

Br. 15 n.13) were made with respect to S.5 or bills similar to it.

The Senate Report specifically says that the Act’s disclosure provision

was altered from S.5 (which required disclosure “ to each person to

whom credit is extended” ) in order to make clear that “ disclosure need

only be made to persons ‘upon whom a finance charge is or may be im-

19

the language of the committee reports, the reports, of course,

would be entitled to precedence as the authentic expression

of the legislative intent. See United States v. International

Union United Automobile, Aircraft & Agricultural Imple

ment Workers o f America, 352 U. S. 567, 585 (1957);

Duplex Printing Press Co. v. Deering, 254 U. S. 443, 474-

75 (1921); American Airlines, Inc. v. CAB, 365 F. 2d

939, 949 (D.C. Cir. 1966); Nicholas v. Denver &

R. G. W. R. R., 195 F. 2d 428, 431 (10th Cir. 1952). More

over, none of the statements cited in the Government’s brief

indicates any expectation that the Act, or the regulations to

be promulgated thereunder, would apply to transactions

that did not involve a finance charge.

The Government calls particular attention to a statement

by Senator Douglas at a Senate subcommittee hearing on

S. 1740 in July 1961 (U. S. Br. 16-17). Senator Douglas’s

remarks were made in response to an argument advanced by

Senator Bennett that two merchants selling identical goods,

both of whom imposed a finance charge, might disclose dif

ferent finance charges as a result of making different alloca

tions between the cash purchase price and cost of credit and

that, therefore, the consumer would have no valid basis for

comparison shopping. In response, Senator Douglas ob

served that the bill would provide the consumer with dis

closure of both the cash price and the finance charges so that

“ the judgment of the consumer can be on the basis o f both

of these factors, not merely on one alone . . . Hearings on

S. 1740 Before a Subcomm. o f the Senate Comm, on Bank

ing and Currency, 87th Cong., 1st Sess. 447-48 (1961).

posed.’ ” s TRep. N o. 392, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. 14 (1967). Moreover,

the definition of “ credit” in S.5 was changed in the Act (§ 1602(e))

so as to exclude from the disclosure requirements those transactions

where it “ would seem impossible to attribute or determine a finance

charge.” Hearings on S.5 Before the Subcomm. on Financial Institu

tions of the Senate Comm, on Banking and Currency, 90th Cong.,1st

Sess. 659-63 (1967).

20

Senator Douglas’s remarks with respect to creditors who

do impose a finance charge does not lend any support to

the notion that Congress intended that disclosures would

be required of those who do not impose a finance charge.

The Government cites (U. S. Br. 16 n.16) other state

ments similar to that of Senator Douglas,* indicating a

congressional concern with the problem of the identification

of finance charges by those creditors who impose such

charges; these statements do not indicate concern about

those situations where a finance charge was not in fact

being imposed. In sum, there is no support for the argu

ment that those creditors who do not impose finance charges

were intended to be reached by the Act despite its clear

wording to the contrary.

On the other hand, the congressional hearings do pro

vide further evidence that the imposition of a finance charge

was understood to be a prerequisite to the Act’s coverage.

Thus, during the 1964 hearings before the Senate Banking

and Currency Committee’s Subcommittee on Production

and Stabilization, a Senator asked the Chairman of the

Federal Trade Commission whether an agreement with his

neighbor’s son under which the son would mow the Sena

tor’s lawn on successive Saturdays and the Senator would

pay him 50 cents “ each time he completes the job” would be

within the purview of the then pending bill. Hearings on

S. 750 Before the Subcomm. on Production and Stabilisa

tion of the Senate Comm, on Banking and Currency, 88th

Cong., 1st and 2nd Sess., pt. 2 at 1298 (1964). The Chair

man of the Federal Trade Commission replied that the lawn

mowing transactions would not be covered. He: explained:

*Hearings on H. R. 11601 Before the Subcomm. on Consumer

Affairs of the House Comm., on Banking and Currency, 90th Cong.,

1st Sess. 590-91, 825-26 (1967) ; Hearings on S. 1740 Before a Sub

comm. of the Senate Comm, on Banking and Currency, 87th Cong.,

1st Sess. 381, 563 (1961).

21

“ First, there must be a transaction involving

‘credit’ as defined in section 3 (2 ). Second, a ‘fi

nance charge’ as defined in section 3 (3 ) must be

imposed in this transaction involving ‘credit’ as de

fined in section 3 (2 ). Third, only a ‘creditor’ as de

fined in section 3 (4 ) is required to make the dis

closure required under this act.

“ . . . In order to determine whether any trans

action which involves credit within the meaning of

section 3 (2) falls within the scope of the bill, it

is necessary to inquire whether a ‘finance charge’ is

imposed; i.e., whether the borrower or credit pur

chaser is required to pay any amount which would

not be incurred in a cash transaction.” Hearings

on S. 750 at 1304.

The Government also urges that during the seven years

of hearings “ everyone assumed that ‘no charge for

credit’ simply meant that the creditor had ‘buried,’ ‘con

cealed’ or ‘packed’ finance charges in the price of the goods

sold.” U. S. Br. 15. As evidence of that assumption the

Government quotes (U. S. Br. 15 n.14) a chief sponsor of

the Act, Senator Proximire. However, moments after Sena

tor Proxmire made the statement quoted in the Govern

ment’s brief, the Senator apparently concluded that some

creditors do not impose finance charges and, indeed, that

the very creditor referred to in the Government’s quotation

did not do so. Senator Proxmire said: “ The fact is that

Foyes is apparently not charging in his merchandise for his

credit.” Hearings on S. 5 Before the Subcomm. on Finan

cial Institutions of the Senate Comm, on Banking and Cur

rency, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. 515 (1967). That conclusion

is consistent with the views expressed in the Senate and

House Reports which were before the Congress that

passed the Act. Those reports specify: “ [Disclosure need

22

only be made to persons ‘upon whom a finance charge is

or may be imposed.’ Thus, the disclosure requirement would

not apply to transactions .. . for which a charge is not made.”

S. R e p . N o . 392, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. 14 (1967); H. R.

R e p . N o . 1040, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. 25 (1967).

Accordingly, it is apparent that the Fifth Circuit’s ob

servation that “ there must be found present a 'finance

charge’ ” before disclosure is required under the Act (App.

49) is correct. Other lower courts have come to the same

conclusion. In Esposito v. Nayer, Civil No. 11-142 (D. Me.,

June 5, 1972), Judge Gignoux, faced with a transaction

identical in all material respects to the one at issue here, held

the four installment rule invalid, saying:

“ Absent a finance charge in the transaction

involved, this Court, like the Mourning Court, finds

the Act itself inapplicable, since neither defendant

is a creditor as defined by the Act. Nor is either

defendant a person required to disclose pursuant to

the requirements of the Act.”

See Garland v. Mobil Oil Corp., 4 CCH Con su m er C redit

Gu ide fl 99,193 at pp. 89, 134-35 (N. D. 111. 1972) (M c

Laren, J . ) ; Otis v. Cowles Communications, Inc., No.

C-71-550 RHS (N. D. Cal., Nov. 3, 1971); Casteneda v.

Family Publications Service, 4 CCH C on su m er C redit

G u ide jf 99,564 (D. Colo. 1971); Bostwick v. Cohen, 319

F. Supp. 875, 878 n.l (N . D. Ohio 1970). See also

Martinez v. Family Publications Service, Inc., No. 71-169-

Civ-TC (S. D. Fla., Oct. 12, 1971). Contra, Strompolos v.

Premium Readers Service, 326 F. Supp. 1100 (N. D. 111.

1971), certified under 28 U. S. C. § 1292(b), settled on

appeal.

23

B. The rule does not effectuate the purpose of the

Act nor does it prevent circumvention or facilitate com

pliance.

In support of the validity of the four installment rule,

it is urged by petitioner and amici curiae that the rule is

needed to solve the problem— supposedly recognized but left

unsolved by Congress— of the “ buried” finance charge. The

problem of the buried finance charge may well be a real

problem, but it is neither presented by this case nor solved

by the four installment rule.

A transaction that entails a finance charge (and meets

the other requirements of the Act) is indubitably subject

to the requirements of the Act— whether or not the finance

charge is buried or otherwise hidden. The plain language

of the Act requires that the specified disclosures be made in

transactions involving finance charges. Neither the Act nor

the Regulation makes any exception for hidden finance

charges.

W e do not doubt that the Board could properly fa

cilitate compliance with the Act by establishing, on any

reasonable basis, guideline formulas for the identification

and quantification of finance charges in difficult cases so that

merchants could make disclosures with confidence that they

had done what was required of them.* Similarly, the Board

*The object of facilitating compliance has been served, inter alia,

by the Board’s regulations with respect to the determination of the

annual percentage rate. Thus, 12 C. F. R. § 226.5(c) provides in

part:

“ Charts and tables. (1 ) The Regulation Z Annual Percentage

Rate Tables produced by the Board may be used to determine

the annual percentage rate, and any such rate determined from

these tables in accordance with instructions contained therein

will comply with the requirements of this section.”

And 12 C. F. R. § 226.5(e) provides in part:

“ In an exceptional instance when circumstances may leave

a creditor with no alternative but to determine an annual

percentage rate applicable to an extension of credit other than

open end credit by a method other than those prescribed in

24

could facilitate private enforcement of the Act by establish

ing rebuttable presumptions as to both the existence and the

amount of finance charges so that private plaintiffs would

not be faced with difficult problems of discovery and ac

countancy. What the Board did, however, is altogether dif

ferent: it simply attempted to eliminate the finance charge

requirement. In doing so, it neither furthered the purposes

of the Act nor facilitated compliance with it. The attempt

to expand the coverage of the Act to embrace transactions

not involving a finance charge cannot solve the practical

problems faced by the merchant who is required to dis

close a finance charge that is hard to identify, nor can it

further the purpose of achieving full and accurate disclo

sure of the cost of credit.

The Government attempts to resolve the problem of

the hard-to-identify finance charge not by reference to the

four installment rule but rather by the more extraordinary

proposition that the merchant may discharge his duties

under the Act by merely disclosing the aggregate pur

chase price without separately identifying the finance

charge. The Government states that “ a creditor might

not be required to disclose finance charges if these were

concealed in increased prices” so long as he discloses “ other

relevant information, such as the cash price and the total

amount to be financed.” (U. S. Br. 16. See also 21 n.26.)

This is simply bizarre. Nothing in the Act justifies that con

clusion, which appears altogether subversive of the con

gressional purpose to require disclosure of the cost of credit.

Had Congress intended what the Government now supposes,

it was a very simple thing to provide (a ) that all creditors

paragraph (b) or (c ) of this section, the creditor may utilize

the constant ratio method of computation provided such use

is limited to the exceptional instance and is not for the pur

pose of circumvention or evasion of the requirements of this

part.”

25

were subject to the Act (rather than only those creditors

who impose a finance charge), and (b) that, in circum

stances to be specified by supplementary regulation, those

creditors who could not segregate the cost of credit from the

total purchase price should disclose the total price and state

that it contained an unspecified finance charge. Congress,

however, did no such thing. It made the Act applicable

only to those creditors who impose a finance charge and

it required that that finance charge be identified.

Under the Government’s thesis, even the merchant who

intentionally “ buries” a finance charge can meet the require

ments of the Act merely by disclosing the aggregate pur

chase price. Moreover, the merchant with no affirma

tive desire to conceal would no longer have any inducement

under the Act to undertake the burden of accurately identi

fying the cost o f credit. In both situations, the consumer

will be denied information as to the cost attributable to

credit. Since, however, neither the Act nor the regulations

afford any warrant whatsoever for the Government’s invi

tation to non-disclosure, we believe that any merchant who

accepts that invitation runs a material risk of criminal

prosecution under 15 U. S. C. § 1612 and of a potentially

staggering civil liability under 15 U. S. C. § 1640(a). In

sum, the four installment rule cannot solve the problem

of the hard-to-identify finance charge to which it was

addressed, and the Government’s non-disclosure rule solves

the problem but only by scuttling one o f the Act’s principal

objectives without any authority from either Congress or

the Board.

Finally, it is apparent that the four installment rule

does not even serve the interests of administrative and ju

dicial economy, as claimed by petitioner and the Govern

ment. (Pet. Br. 16-17; U. S. Br. 25.) If, as the Govern

ment suggests (U. S. Br. 25), “ endless legal disputes-over

bookkeeping practices and other matters” would result in

2 6

the absence of the rule because of the need to establish the

existence o f a finance charge, then similar disputes will

arise, notwithstanding the rule, as to the amount of the

finance charge and the accuracy of the disclosures. Those

who are prompted to sue merchants making no disclosures

would, if the rule were sustained, sue merchants making

allegedly inaccurate disclosures— including merchants who,

rightly or wrongly, would disclose that no finance charges

were entailed in their transactions. So long as the Act pro

vides that a finance charge must be accurately disclosed, the

existence and amount of such charges will be a central ele

ment in litigation under the Act. Whatever the problems

of proof involved, the four installment rule does not obviate

them. On the other hand, in so far as the Board seeks to

expand the coverage of the Act to embrace classes of mer

chants and transactions not covered by Congress, it can only

increase the amount o f litigation engendered by the Act.

C. The four installment rule is an invalid adminis

trative attempt to extend the Act beyond its intended

bounds.

Petitioner ultimately relies on the proposition that the

Board was authorized to promulgate “ legislative” as well

as merely “ interpretive” regulations and, thus, was em

powered to “ correct any oversight or omissions” in the Act,

to “ embrace a penumbra” beyond the objectives of the Act

and to alter “ the lines drawn by the statute itself” (Pet. Br.

18, 22, 32; Pet. 13). The argument proves either too little

or too much. Since, as we have shown above, Congress

explicitly and intentionally limited the coverage of the Act

to transactions involving a finance charge, the exclusion of

transactions not involving a finance charge can hardly be

regarded as a legislative “ oversight or omission” . On the

other hand, there is no warrant in the decisions of this

27

Court for the proposition that an administrative agency,

however well intentioned, may simply overrule a congres

sional decision under the guise of exercising “ legislative

rule making power” (Pet. Br. 22). The legislative power

of the United States is, after all, granted to Congress

(U. S. Const., Art. I, § 1), and while Congress may delegate

legislative power under appropriate guidelines, Sunshine

Anthracite. Coal Co. v. Adkins, 310 U. S. 381, 398 (1940);

United States v. Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific

Railroad Co., 282 U. S. 311, 324 (1931), an intent to

delegate the power to override congressional determinations

is not readily to be presumed, nor can it be inferred from

anything in the Truth in Lending Act.

The court of appeals held that “ the four installment rule

of Regulation Z constituted an administrative endeavor to

amend the law as enacted by the Congress” (App. 51).

The court’s conclusion that the Board, in promulgating the

rule, had “ over-stepped the authority granted to them under

15 U. S. C., § 1604” (App. 51) is clearly supported by the

decisions of this Court.

In Federal Communications Commission v. American

Broadcasting Co., Inc., 347 U. S. 284 (1954), this Court

was faced with an attempt by the Federal Communications

Commission to prevent circumvention and evasion of § 1304

o f the United States Criminal Code (formerly § 316 of

the Communications Act of 1934). The statute prohibits

the broadcasting of “any lottery, gift enterprise, or similar

scheme, offering prizes dependent in whole or in part upon

lot or chance . . . .” Although the statute did not define

“ lottery” , lotteries traditionally had been considered to have

three essential elements: (1 ) the distribution of prizes (2 )

according to chance (3 ) for a consideration. 347 U. S. at

290.

In promulgating rules designed to prevent the broad

casting o f programs prohibited by the statute, the Com-

28

mission was faced with a pervasive pattern o f circumven

tion by lottery promoters. As this Court noted:

“ Enforcing such legislation has long been a diffi

cult task. Law enforcement officers, federal and

state, have been plagued with as many types of

lotteries as the seemingly inexhaustible ingenuity of

their promoters could devise in their efforts to cir

cumvent the law. When their schemes reached the

courts, the decision, of necessity, usually turned on

whether the scheme, on its own peculiar facts, con

stituted a lottery.” 347 U. S. at 292-93.

In particular, the question of what constituted “ considera

tion” was one that had continually troubled the courts, and

promoters had persistently exercised their ingenuity in de

vising new schemes, not previously prohibited. 347 U. S. at

293. The Commission, seeking to prevent continued circum

vention and evasion of the statute and to achieve what it

believed to be a valuable social end, adopted a regulation that

eliminated consideration as a necessary element of a pro

scribed lottery. This Court held that the Commission had

overstepped its authority under the Act. The Court said:

“Unless the ‘give-away’ programs involved here are

illegal under § 1304, the Commission cannot employ

the statute to make them so by agency action. Thus,

reduced to its simplest terms, the issue before us is

whether this type of program constitutes a ‘lottery,

gift enterprise, or similar scheme’ proscribed by

§ 1304.” 347 U. S. at 290.

In commenting on the circumvention argument, the Court

said:

_ “ It is apparent that, these so-called ‘give-away’

programs have long been a matter of concern to the

29

Federal Communications Commission; that it be

lieves these programs to be the old lottery evil under

a new guise, and that they should be struck down as

illegal devices appealing to cupidity and the gambling

spirit. . . . Regardless of the doubts held by the

Commission and others as to the social value of the

programs here under consideration, such adminis

trative expansion of § 1304 does not provide the

remedy.” 347 U. S. at 296-97.

The instant case involves an even clearer example of invalid

legislation-by-regulation since here one need not scrutinize

the intricacies o f the common law to ascertain the bounda

ries of the statutory requirement. The disclosure and pen

alty provisions of the Truth in Lending Act explicity apply

only to transactions involving a finance charge.

It should also be noted that in ABC, as here, the Court

was faced with a civil case arising under a statute that also

provided for criminal penalties. The Court said:

“ It is true, as contended by the Commission, that

these are not criminal cases, but it is a criminal

statute that we must interpret. There cannot be one

construction for the Federal Communications Com

mission and another for the Department of Justice.

If we should give § 1304 the broad construction

urged by the Commission, the same construction

would likewise apply in criminal cases. We do not

believe this construction can be sustained. Not only

does it lack support in the decided cases, judicial and

administrative, but also it would do violence to the

well-established principle that penal statutes are to

be construed strictly.” 347 U. S. at 296.

See Commissioner v. Acker, 361 U. S. 87, 91 (1959);

Keppel v. Tiffin Savings Bank, 197 U. S. 356, 362 (1905).

This Court emphasized the inability o f an administra

tive agency to go beyond its enabling act in Addison v.

30

Holly Hill Fruit Products, Inc., 322 U. S. 607 (1944). The

Addison case arose under Section 13(a) (10) of the Fair

Labor Standards Act, which exempted from the minimum

wage and overtime requirements of the statute persons

employed “ within the area of production (as defined by the

Administrator)” in certain agricultural occupations. Pur

suant to that authority the Administrator defined “ area of

production” to include any person engaged in such an oc

cupation “ where he is employed from farms in the im

mediate locality and the number of employees in such

establishment does not exceed seven” . 29 C. F. R. § 536.2

(b ) (Supp. 1938). Notwithstanding the fact that the

definition of that term was expressly left to the Adminis

trator, this Court held that the Administrator’s power to

define “ area of production” was limited by that statutory

term to the drawing of geographic lines and that his regu

lations, which made discriminations on the basis of the

number o f . employees, were ultra vires. See also Zuber v.

Allen, 396 U. S. 168, 183 (1969) ( “ Congress has spoken

with particularity. . . . In these circumstances an adminis

trator does not have ‘broad dispensing power.’ ” ) ; Com

missioner v. Acker, 361 U. S. 87, 93-94 (1959) ( “ The

questioned regulation must therefore be regarded ‘as no

more than an attempted addition to the statute of some

thing which is not there.’ ” ) ; United States v. Calamaro,

354 U. S. 351, 357 (1957) ( “ Neither we nor the Commis

sioner may rewrite the statute simply because we may feel

that the scheme it creates could be improved upon.” ) ; Hel

vering v. Credit Alliance Corp., 316 U. S. 107, 113 (1942).

Further, the four installment rule is invalid for the

reasons set forth in Miller v. United States, 294 U. S. 435

(1935). In Miller, the plaintiff sought judgment upon a

war risk insurance policy, issued by the United States pur

suant to a statute authorizing protection against the risk o f

death or “ total permanent disability.” The Administrator

31

of Veterans’ Affairs, purporting to act pursuant to au

thority to make such rules and regulations as might be

necessary or appropriate to carry out the purposes of the

act, had provided by regulation that the loss of one hand

and one eye “ shall be deemed to be total permanent disa

bility under yearly renewable term insurance” . That regu

lation the Court held invalid because it converted “ total

permanent disability” from a factual condition to be de

termined in light o f all the relevant circumstances into a

matter to be presumed upon the finding of more limited,

specific facts. The Court observed:

“ It is invalid because not within the authority con

ferred by the statute . . . to make regulations to

carry out the purposes of the act. It is not, in the

sense of the statute, a regulation at all, but legisla

tion. . . . The vice o f the regulation, therefore, is

that it assumes to convert what in the view of the

statute is a question of fact requiring proof into a

conclusive presumption which dispenses with proof

and precludes dispute. This is beyond administrative

power. The only authority conferred, or which

could be conferred, by the statute is to make regula

tions to carry out the purposes of the act— not to

amend it.” Id. at 439-40 (emphasis added).

The same vice is present in the four installment rule. The

rule converts what under the Act is a question of fact re

quiring proof (whether there is a finance charge) into a

conclusive presumption which dispenses with proof.*

*“ In effect, the [four installment] rule establishes a conclusive

presumption that those who extend credit and permit payment in

four or more installments have included within the price which the

consumer pays for their product their cost of extending credit, not

withstanding that they may purport not to levy a finance charge.

In the vast majority of cases, that presumption is in full accordance

with economic reality . . . . While it is possible that there are some

32

The cases cited by petitioner and the Government are

quite simply inapposite and do not support the validity

of the four installment rule. A comparison of the statute

and regulation involved in each of the cases cited fails

to reveal any conflict between the act and the regulation.

Gemsco, Inc., v. Walling, 324 U. S. 244 (1945), Thorpe

v. Housing Authority, 393 U. S. 268 (1969), Fibreboard

Paper Products Corp. v. NLRB, 379 U. S. 203 (1964),

and National Broadcasting Co. v. United States, 319

U. S. 190 (1943), all involved agency regulations or

adjudications which merely constituted particularizations

of the respective statutes as to matters about which

Congress had not spoken with specificity and were not in

any way inconsistent with an act of Congress. (324 U. S.

at 261-63; 393 U. S. at 277-78, 379 U. S. at 215-17, 319

U. S. at 218-20.)* *

POINT II

THE JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF APPEALS SHOULD

BE SUSTAINED ON THE GROUNDS, NOT REACHED

BELOW , THAT A CIVIL PENALTY UNDER THE ACT MAY

NOT BE IMPOSED IN THE ABSENCE OF A FINANCE

CHARGE AND THAT FPS DID NOT EXTEND CREDIT

WITHIN THE MEANING OF THE ACT.

Although the decision of the court of appeals is based

entirely on the invalidity of the four installment rule, the

judgment is sustained by two independent considerations

that were advanced by FPS but which the court o f appeals

creditors who agree to permit payment in four or more installments

without structuring, the cost of extending credit into the price . . .

an administrative agency . . . must be permitted to make rough

accommodations even if its classifications result in some inequity . . . .”

U, S. Br. in the Fifth Circuit at 24-25.

*In United States v. Foster, 233 U. S. 515, 527 (1914), the

Court found the regulation there in issue to be purely administrative

and said it “ executed the.. . . law; [but] adds nothing to it” . That

33

did not reach.* First, we urged that, irrespective o f the

validity of the four installment rule, IS U. S. C. § 1640(a)

provides for civil liability only in cases involving a finance

charge.** Second, we showed that the Truth in Lending

Act is inapplicable here because the transaction in issue

did not involve the extension o f credit.*** For the reasons

set forth below, the judgment of the court o f appeals should

be sustained on both of those grounds, regardless of this

Court’s determination with respect to the validity of the

four installment rule. See, e.g., Le Tulle v. Scofield, 308