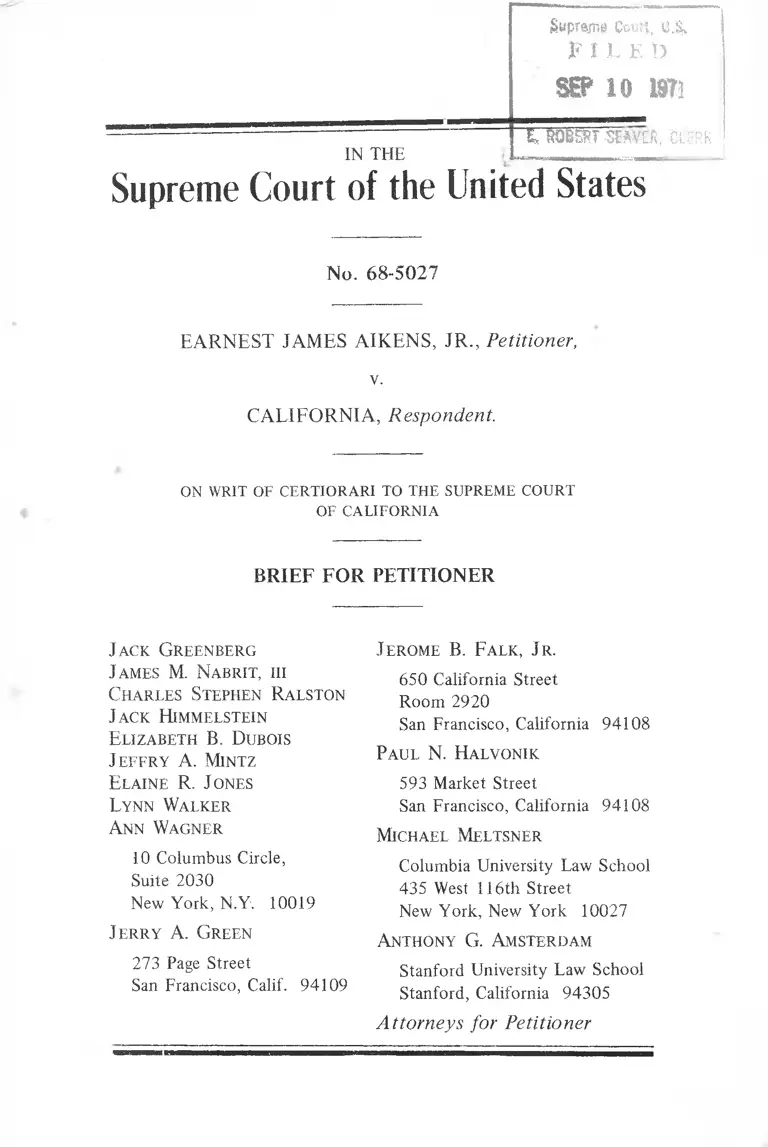

Aikens v. California Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

September 10, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Aikens v. California Brief for Petitioner, 1971. 388d610e-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e5e70f74-7adc-4e59-abf7-c1f9f2ae877a/aikens-v-california-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme c@uri, U&

F I L E 1.)

SEP 10 M ]

IN THE

t PQBSfH ■SEWER, TU Y

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 68-5027

EARNEST JAMES AIKENS, JR., Petitioner,

v.

CALIFORNIA, Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, hi

Charles Stephen Ralston

J ack Himmelstein

Elizabeth B. Dubois

J effry A. Mintz

Elaine R. J ones

Lynn Walker

Ann Wagner

10 Columbus Circle,

Suite 2030

New York, N.Y. 10019

J erry A. Green

273 Page Street

San Francisco, Calif. 94109

J erome B. Falk, J r.

650 California Street

Room 2920

San Francisco, California 94108

Paul N. Halvonik

593 Market Street

San Francisco, California 94108

Michael Meltsner

Columbia University Law School

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Anthony G. Amsterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioner

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

OPINIONS BELOW..................................... 1

JURISDICTION ..................................... .. .................... ................ 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED............................................................ 2

QUESTION PRESENTED ............................................................ 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............................................ 3

HOW THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION

WAS PRESENTED AND DECIDED BELOW ......................... 6

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 6

ARGUMENT:

I. Introduction .......................................................... 7

II. The Relevant Eighth Amendment Standard . ....................... 13

III. The Penalty of Death . ......................... ................................ 27

CONCLUSION .................................. 61

Appendix A: Statutory Provisions Involved .............................. la

Appendix B: Summary of the Evidence Relating to the

Killings of Mrs. Eaton and Mrs. Dodd .............................. lb

A. The Eaton Killing ............................................................... 2b

B. The Dodd Killing ................................................................. 9b

Appendix C: Punishments Authorized by Law

and Usage, 1786-1800 .................................................................... 1c

A. Penal Laws Applicable to Freemen ................. ................ 1c

B. Penal Laws Applicable to Slaves .............................. 16c

C. Infliction of Corporal Punishments at the

End of the Eighteenth Century ...................... 21c

D. Banishment ....................................................... 26c

Appendix D: Synopsis of the Constitutional History

of the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause of the

Eighth Amendment ...................................................................... Id

A. English Antecedents ............................................................ Id

Page

B. Developments in America .................................................. 2d

1. Pre-Revolutionary Times ............................................. 2d

2. State Constitutions, 1776-1790 2d

3. The Federal Constitution ............................................. 4d

Appendix E: Worldwide and National Trends in the

Use of the Death Penalty ............................................................ le

Appendix F: Available Information Relating to the

Proportion of Persons Actually Sentenced to Death

Among Those Convicted of Capital Crimes .............................. If

1. M urder.................................................................................... 3f

2. Rape ..................................................................................... 8f

Appendix G: Provisions of the Criminal Statutes of

the United States and of the Fifty States Providing

for the Punishment of D e a th ....................................................... lg

Appendix H: The Evidence Concerning the Deterrent

Efficacy of the Death Penalty....................................................... lh

A. The Statistical Evidence....................................................... lh

B. Impressions of Law Enforcement O fficers......................... 6h

Appendix I: Descriptions of American Methods

of Execution .............................. .............. ..................... .. li

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Abbate v. United States, 359 U.S. 187 (1959)............ ................ 9

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).................... 15

Collins v. Johnston, 237 U.S. 502 (1 9 1 5 )..................................... 8

Dear Wing Jung v. United States, 312 F.2d 73 (9th Cir.

1962)........................ 11

Ex parte Wilson, 114 U.S. 417 (1 8 8 5 )................................ 15-16, 18

Funicello v. New Jersey, __ U .S .___, 29 L. ed. 2d 859

(1971)..........................................................................................41,63

Furman v. Georgia, O.T. 1971, No. 69-5003 ................. .............. 5

Goss v. Bomar, 337 F.2d 341 (6th Cir. 1 9 6 4 ).............................. 15

In re Anderson, 69 Cal. 2d 613, 447 P.2d 117, 73 Cal. Rptr.

21 (1968) 6

( Hi)

Page

In re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436 (1 8 9 0 )......................... .. 7, 8, 9, 11, 14

Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F.2d 571 (8th Cir. 1968).................... 11, 15

M’Culloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat, 316 (1819) .............................. 15

McElvaine v. Brush, 142 U.S. 1 5 5 (1 8 9 1 )..................................... 8

McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183 (1971) ............... 3, 23, 49, 53

Mackin v. United States, 117 U.S. 348 (1886) ........................... 16

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961) ............................................. 9

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 F.2d 138 (8th Cir. 1968), vacated

on other grounds, 398 U.S. 262 (1 9 7 0 ) ........................... .. 53

O’Neil v. Vermont, 144 U.S. 323 (1892) . ............................ 8, 24-25

Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319 (1937)................................... 14

People v. Robinson, 61 Cal. 2d 820, 457 F.2d 889, 80 Cal.

Rptr. 49 (1 9 6 9 ).......................................................................... 1

People v. Stanworth, 71 Cal. 2d 820, 457 P.2d 889, 80 Cal.

Rptr. 49 (1 9 6 9 ) .......................................................................... 6

Pervear v. Massachusetts, 5 Wall. (72 U.S.) 475 (1 8 6 7 )............... 8

Powell v. Texas, 392 U.S. 514 (1968) ............ ................ 13, 59, 63

Ralph v. Warden, 438 F.2d 786 (4th Cir. 1970)................. 8, 11, 23,

24, 39, 50

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962)............... 13, 14, 15, 18

State v. Cannon, 55 Del. 585, 190 A.2d 514 (1963) ................. 19

State ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 (1947) . . . . . . 8, 9

Trap v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) . . . 8, 9, 11, 14, 15, 18, 19, 20,

24, 26, 31, 39, 54, 57, 61, 63

United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1 9 6 8 ) ........................... 41

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910) . . . . 7, 11, 14, 16, 17,

18, 19, 20, 24, 57

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1 8 7 8 )...................... 8, 9, 11, 14, 25

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1 9 7 0 ) .................................... 9, 13

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1 9 4 9 ) ................................ 9

Williams v. Oklahoma, 358 U.S. 576 (1 9 5 9 ) ................................ 8

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) ................. 39, 41, 43

(iv)

Page

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions:

Fifth Amendment, U.S. Constitution......................................... 18

Eighth Amendment, U.S. Constitution..................................... passim

Fourteenth Amendment, U.S. Constitution.........................2, 6, 7, 8,

3, 14, 53, 54

28 U.S.C. § 1257(3). ........................................................................ 2

Cal. Penal Code § 187 ....................................................................... 2

Cal. Penal Code § 188 ..................................... 2

Cal. Penal Code § 189 ............. 2

Cal. Penal Code § 190 ...................................................................... 2

Cal. Penal Code § 190.1 ............... ................................................... 2, 3

Cal. Penal Code § 1239 ................................................................... 6

Cal. Penal Code § 3604 ................................................................... 2

Cal. Penal Code §3605 ................................................................. 2 ,44

Act of September 24, 1789, Ch. 20, §9; 1 Stat. at L., 77 . . . . 18

I ACTS OF CANADA (16-17 Eliz. II) 145 (1967-1968)___ 33-34

Bill of Rights of 1689 (1 Wm. & Mary, Sess. 2, Ch. 2, Pre

amble, clause 1 0 ) ......................................................... 14

Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act 1965, 2 PUBLIC

GENERAL ACTS, Ch. 71, p. 1577 (Nov. 8, 1965) ............... 32

II REV. STAT. OF CANADA (1970) Ch. C-34 §§ 46, 47,

7 5 ................................................................................................... 34

4 & 5 Will. IV, Ch. 26, §§ 1, 2 ....................................................... 44

Other Authorities:

ANCEL, THE DEATH PENALTY IN EUROPEAN COUN

TRIES (Council of Europe, European Committee on

Crime Problems, 1962) [cited as ANCEL] .................... 28, 30, 35

Appendix to the Amici Curiae Brief of the American

Friends Service Committee, et al., in Witherspoon v. Illi

nois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) [O.T. 1967, No. 1 0 1 5 ] ................. 32

BARNES & TEETERS, NEW HORIZONS IN CRIMINOL

OGY (3d ed. 1959)..................................................................... 44

Barry, Hanged by the Neck U n t i l 2 SYDNEY L. REV.

401 (1958) ............................................................................. 27, 62

(v)

Page

Bedau, A Social Philosopher Looks at the Death Penalty,

123 AM. J. PSYCHIATRY 1361 (1 9 6 7 )...................... .. 52, 59

Bedau, Capital Punishment in Oregon, 1903-1964, 45 ORE.

L. REV. 1 (1 9 6 5 )....... ................................................................ 51

Bedau, Death Sentences in New Jersey 1907-1960, 19

RUTGERS L. REV. 1 (1 9 6 4 ).......... .. .................... 28, 51,52, 59

Bedau, The Courts, The Constitution, and Capital Punish

ment, 1968 UTAH L. REV. 2 0 1 .......................................... 12, 55

BEDAU, THE DEATH PENALTY IN AMERICA (Rev. ed.

1967) [cited as BEDAU] ................. .. 25, 31, 32, 35, 43, 44,

48, 50, 52, 59, 60, 61

Bedau, The Issue o f Capital Punishment, 53 CURRENT

HISTORY (No. 312) 82 (Aug. 1967)........................................ 32

BENTHAM, TO HIS FELLOW CITIZENS OF FRANCE,

ON DEATH PUNISHMENT (1831)..................................... 28, 34

BLOCK, AND MAY GOD HAVE MERCY (1962) .................... 32

BOK, STAR WORMWOOD (1 9 5 9 )......................................... 31, 46

Brief for Petitioner, Jackson v. Georgia, O.T. 1971, No.

69-5030 .......................................................................................... 53

Brief for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and the National Office for the Rights of the

Indigent, as Amici Curiae, in Boykin v. Alabama, 395

U.S. 238 (1969) [O.T. 1968, No. 6 4 2 ] ........................... .. . 51, 57

BYE, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN THE UNITED STATES

(1919)....................................................................................... 32,44

CALVERT, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN THE TWENTIETH

CENTURY (1927) ................................ .......................... 31 ,48 ,59

CALIFORNIA ASSEMBLY, REPORT OF THE SUBCOM

MITTEE OF THE JUDICIARY COMMITTEE ON CAPI

TAL PUNISHMENT (1 9 5 7 )............................................. 42, 60, 61

Camus, Reflections on the Guillotine in CAMUS, RESIST

ANCE, REBELLION AND DEATH (1961) [cited as

CAMUS]......................................................... 31-32, 45, 46-47, 58

CANADA, HOUSE OF COMMONS, IV and V DEBATES,

27th Park, 2d Sess. (16 Eliz. II) (1967) 33-34

(vi)

Page

CANADA, JOINT COMMITTEE OF THE SENATE AND

HOUSE OF COMMONS ON CAPITAL AND CORPORAL

PUNISHMENT AND LOTTERIES, REPORT (1956)............ 60

CARDOZO, THE NATURE OF THE JUDICIAL PROCESS

(1921)............................................................................................ 15

Carter & Smith, Count Down for Death 15 CRIME &

DELINQUENCY 77 (1969) ....................................................... 44

Carter & Smith, The Death Penalty in California: A Statisti

cal and Composite Portrait, 15 CRIME AND DELIN

QUENCY 62 (1 9 6 9 ) ................................................................... 51

CEYLON, SESSIONAL PAPER XIV-1959, REPORT OF

THE COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON CAPITAL PUN

ISHMENT (1 9 5 9 )........................................................................ 60

CLARK, CRIME IN AMERICA (1 9 7 0 )...................... 33, 51, 52, 56

DeMent, A Plea for the Condemned, 29 ALA. LAWYER

440 (1968) ................................................................... 50

Comment, The Death Penalty Cases, 56 CALIF. L. REV.

1268 (1968) ............................................. 12

DiSalle, Comments on Capital Punishment and Clemency,

25 OHIO ST. L. J. 71 (1964)............ ....................................... 51

Di Salle, Trends in the Abolition o f Capital Punishment,

1 U. TOLEDO L. REV. 1 (1969) ................................... 51

DOSTOEVSKY, THE IDIOT (Modern Library, 1 9 3 5 ) ............... 57

DUFFY & HIRSHBERG, 88 MEN AND 2 WOMEN

(1962).......................................................................... 50, 51, 59, 60

3 ELLIOT, DEBATES IN THE SEVERAL STATE CON

VENTIONS ON THE ADOPTION OF THE FEDERAL

CONSTITUTION (2d ed. 1863)................................................. 14

Erskine-, The Polls: Capital Punishment, 34 PUBLIC OPIN

ION QUARTERLY 290 (1970) . . . . . . ....... ........................ 39

FAVREAU, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: MATERIAL RELAT

ING TO ITS PURPOSE AND VALUE (Compiled by

Hon. Guy Favreau, Canadian Minister of Justice) (Queen’s

Printer, Ottawa, 1965) [cited as FAVREAU] ....................... 31, 60

Filler, Movements To Abolish the Death Penalty in the

United States, 284 ANNALS 124 (1 9 5 2 )......................... 32, 44

Page

( vii)

FORSYTH, HISTORY OF TRIAL BY JURY (2d ed.

1878) . .................... .................................................................. 22-23

FRANKFURTER, OF LAW AND MEN (1956) ......................... 61

Garfmkel, Research Note on Inter- and Intra-Racial Homi

cides, 27 SOCIAL FORCES 369 (1949)................................... 52

Goldberg & Dershowitz, Declaring the Death Penalty Uncon

stitutional, 83 HARV. L. REV. 1773 (1960).......... 12, 23, 43, 44

Gottlieb, Capital Punishment, 15 CRIME & DELINQUENCY

1 (1969) ....................................................................................... 49

Gottlieb, Testing the Death Penalty, 34 SO. CALIF. L.

REV. 268 (1 9 6 1 )........................................................................ 12

Granucci, “Nor Cruel and Unusual Punishments Inflicted”:

The Original Meaning, 57 CALIF. L. REV. 839 (1969) . . . 14, 21

GOWERS, A LIFE FOR A LIFE (1956)..................................... 32

268 HANSARD, PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (5th series)

(Lords, 43d Pari., 1st Sess., 1964-1965).................................. 7

306 HANSARD, PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (5th Series)

(Lords, 44th Pari., 4th Sess., 1969-1970)...................... 32, 33-34

709-716 HANSARD, PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (5th

Series) (Commons, 43d Pari., 1st Sess., 1964-1965); 268-

269 id. (Lords, 43d Pari., 1st Sess., 1964-1965) .................... 34

793 HANSARD, PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (5th Series)

(Commons, 44th Pari., 4th Sess., 1969-1970) .................... 32, 34

Hartung, Trends in the Use o f Capital Punishment, 284

ANNALS 8 (1 9 5 2 ).................................................... 28, 44, 50, 52

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Criminal Laws and

Procedures o f the Senate Committee on the Judiciary,

90th Cong., 2nd Sess., on S. 1760, To Abolish the Death

Penalty (March 20-21 and July 2, 1968) (G.P.O. 1970)

[cited as Hearings]................................... 31, 32, 33, 50, 58, 59, 60

Johnson, Selective Factors in Capital Punishment, 36 SOCIAL

FORCES 165 (1957).............................................................. 51, 52

Johnson, The Negro and Crime, 217 ANNALS 93 (1941).......... 52

JOYCE, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: A WORLD VIEW (1961) . . . 28

Kahn, The Death Penalty in South Africa, 18 TYDSKRIF

VIR HEDENDAAGSE ROMEINS-HOLLANDSE REG

108 (1970) [cited as Kahn]............................................... 28, 29, 30

Knowlton, Problems o f Jury Discretion in Capital Cases, 101

U. PA. L. REV. 1099 (1953) .................................................... 50

Koeninger, Capital Punishment in Texas, 1924-1968, 15

CRIME AND DELINQUENCY 132 (1969) . .................. .. 51

KOESTLER, REFLECTIONS ON HANGING (Amer. ed.

1957) [cited as KOESTLER] ............ ..................... 32, 35, 39, 59

KOESTLER & ROLPH, HANGED BY THE NECK (1961) . . . 45

Kuebler, Punishment by Death, 2 EDITORIAL RESEARCH

REPORTS (No. 3) (July 17, 1 9 6 3 ).......................................... 28

LAURENCE, A HISTORY OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

(1932) ....................................................................................... 28, 48

LAWES, LIFE AND DEATH IN SING SING (1928) . . . . 47, 51, 61

LAWES, TWENTY THOUSAND YEARS IN SING SING

(1932)................................................................... 26, 49, 50, 51, 57

MANGUM, THE LEGAL STATUS OF THE NEGRO (1940) . . . 52

MATTICK, THE UNEXAMINED DEATH (1966) [cited as

MATTICK]........................................................................... 27, 52, 59

McGee, Capital Punishment as Seen by a Correctional

Administrator, 28 FEDERAL PROBATION (No. 2) 11

(1964) ......................................................................42, 51, 61

MENNINGER, THE VITAL BALANCE (1963) ......................... 47

2 NATIONAL COMMISSION ON REFORM OF FEDERAL

CRIMINAL LAWS, WORKING PAPERS (G.P.O. 1 9 7 0 )----- 31

National Council on Crime & Delinquency, Board ot Trust

ees, Policy Statement on Capital Punishment, 10 CRIME

AND DELINQUENCY 105 (1 9 6 4 ) .......................................... 60

NEW JERSEY, COMMISSION TO STUDY CAPITAL PUN

ISHMENT, REPORT (1964) .................................................... 60

NEW YORK STATE, TEMPORARY COMMISSION ON

REVISION OF THE PENAL LAW AND CRIMINAL

CODE, SPECIAL REPORT ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

(1965) 60

( ix )

Note, A Study o f the California Penalty Jury in First-Degree

Murder Cases, 21 STAN. L. REV. 1297 (1 9 6 9 )................. 51,

Note, Jury Selection and the Death Penalty: Witherspoon in

the Lower Courts, 37 U. CHI. L. REV. 759 (1 9 7 0 ) ...............

Note, Revival o f the Eighth Amendment: Development o f

Cruel-Punishment Doctrine by the Supreme Court, 16

STAN. L. REV. 996 (1964) .”.......... .......................................IT

Note, The Effectiveness o f the Eighth Amendment: An

Appraisal o f Cruel and Unusual Punishment, 36 N.Y.U.

L. REV. 846 (1 9 6 1 ) ...................................................................

OHIO LEGISLATIVE SERVICE COMMISSION, STAFF

RESEARCH REPORT No. 46, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

(1961) ............................................................................................

Patrick, The Status o f Capital Punishment: A World Perspec

tive, 56 J. CRIM. L„ CRIM. & POL. SCI. 397 (1965) . . . 12,

PENNSYLVANIA, JOINT LEGISLATIVE COMMITTEE ON

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT, REPORT (1 9 6 1 ) ...................... 52,

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, in Anderson et al. v. Cali

fornia, O.T. 1968, No. 1643 Misc. [now O.T. 1971, No.

68-5007] . . . . . . . . ................. . ........................................

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari in Forcella v. New Jersey,

O.T. 1968, No. 947 Misc..............................................................

PHILLIPSON, THREE CRIMINAL LAW REFORMERS

(1923).......................................... .................................................

PLAYFAIR & SINGTON, THE OFFENDERS (1 9 5 7 ).......... 35,

PRESIDENT’S COMMISSION ON LAW ENFORCEMENT

AND ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE, REPORT (THE

CHALLENGE OF CRIME IN A FREE SOCIETY)

(1967).................................................................................. 36, 52,

I RADZINOWICZ, A HISTORY OF ENGLISH CRIMI

NAL LAW AND ITS ADMINISTRATION FROM 1750

(1948)....................................................................................... 29,

Recent Decision, 5 U. RICHMOND L. REV. 392 (1 9 7 1 ) ..........

ROYAL COMMISSION ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT 1949-

1953, REPORT (H.M.S.O. 1953) [Cmd. 8932] [cited as

ROYAL COMMISSION].................................................... 45, 59,

52

41

-12

11

27

29

60

62

62

32

61

60

32

12

60

(x )

Rubin, Disparity and Equality o f Sentences-A Constitu

tional Challenge, 40 F.R.D. 55 (1 9 6 6 )..................................... 53

SCOTT, THE HISTORY OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

(1950)............................................................................................ 28

SELLIN, THE DEATH PENALTY (1959) published as an

appendix to AMERICAN LAW INSTITUTE, MODEL

PENAL CODE, Tent. Draft No. 9 (May 8, 1959) [cited

as SELLIN (1959)]............................................................ 27, 35, 59

SELLIN, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT (1967) [cited as SELLIN

(1 9 6 7 )]................................ 12, 27, 28, 31, 35, 38, 47, 55, 59, 60

2 STORY, COMMENTARIES ON THE CONSTITUTION

OF THE UNITED STATES (4th ed. 1873) ........................... 19

Supplemental Brief in Support of Petitions for Writs of Cer

tiorari, in Mathis v. New Jersey, ----U.S. ----- , 29 L. ed.

2d 885 (1971) [O.T. 1970, No. 5 0 0 6 ] ..................................... 41

Symposium on Capital Punishment, 7 N.Y. L. FORUM 247

(1961).................................................................................. 28, 42, 55

TEETERS & HEDBLOM, HANG BY THE NECK (1967) . . . . 48

The New York Times, May 4, 1 9 7 1 ............................................... 40

The New York Times, December 19, 1969 ................................... 33

The Philadelphia Sunday Bulletin, May 23, 1971 ......................... 40

TUTTLE, THE CRUSADE AGAINST CAPITAL PUNISH

MENT IN GREAT BRITAIN (1961)................................... 32, 44

UNITED NATIONS, DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND

SOCIAL AFFAIRS, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT (ST/SOA/

SD/9-10) (1968) [cited as UNITED NATIONS] ----- 27, 28, 29,

30, 31, 35, 50, 52, 60

UNITED NATIONS, ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL

(Note by the Secretary-General) Capital Punishment

(E/4947) (Feb. 23, 1971)................. ............................... 27, 28, 30

UNITED NATIONS, ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL,

Resolution 1574(L), Capital Punishment, adopted May

20, 1971 (E/RES/1574(L) May 28, 1 9 7 1 ) ............ ................ 31

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, BUREAU

OF PRISONS, NATIONAL PRISONER STATISTICS,

Bulletin No. 45, Capital Punishment 1930-1968 (August

1969 [cited as NPS (1968)] .............................. 25, 36, 37, 38, 52

(x i)

Van Niekerk, The Administration o f Justice, Law Reform

and Jurisprudence (1967) ANNUAL SURVEY OF SOUTH

AFRICAN LAW 444 ................................................................... 30

Vialet, Capital Punishment: Pro and Con Arguments (United

States, Library of Congress, Legislative Reference Service,

Mimeo, August 3, 1966), reprinted in Hearings Before

the Subcommittee on Criminal Laws and Procedures o f

the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 90th Cong.,

2nd Sess., on S. 1760, To Abolish the Death Penalty

(March 20-21 and July 2, 1968) (G.P.O. 1970) [cited as

Hearings] ....................................................................................... 3 1

WEIHOFEN, THE URGE TO PUNISH (1956) [cited as

WEIHOFEN] ............................................... .. ....................... 27, 61

West, Medicine and Capital Punishment, in Hearings Before

the Sub-Committee on Criminal Laws and Procedures

o f the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 90th Cong.,

2nd Sess., on S. 1760, To Abolish the Death Penalty

(March 20-21 and July 2, 1968) (G.P.O. 1970) [cited as

Hearings] ..................................................................... 35, 51, 57, 61

WOLFGANG & COHEN, CRIME AND RACE: CONCEP

TIONS AND MISCONCEPTIONS (1970)................................ 52

Wolfgang, Kelly & Nolde, Comparison o f the Executed and

Commuted Among Admissions to Death Row, 53 J.

CRIM. L., CRIM. & POL. SCI. 301 (1962)...................... 52

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 68-5027

EARNEST JAMES AIKENS, JR., Petitioner,

v.

CALIFORNIA, Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of California affirm

ing petitioner’s conviction of first degree murder and sentence

of death by lethal gas is reported at 70 Cal. 2d 369, 450 P.

2d 258, 74 Cal. Rptr. 882. The oral opinions of the Super

ior Court of Ventura County finding petitioner guilty and

sentencing him to die are unreported, and appear in the

trial transcript at Tr. 3372-3419 and 4980-4992.1

‘Respondent has filed a motion, with petitioner’s acquiescence,

requesting that the Court consider this case upon the original record

and dispense with the printing of an Appendix. Petitioner’s brief is

required to be filed before the motion can be decided. We therefore

refer to the documents as paginated in the original record.

2

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of this Court rests upon 28 U.S.C. § 1257

(3), the petitioner having asserted below and asserting here

a deprivation of rights secured by the Constitution of the

United States.

The judgment of the Supreme Court of California was

entered on February 18, 1969. Pursuant to Rule 22(1) of

this Court, Mr. Justice Douglas extended the time for filing

a petition for certiorari until May 30, 1969; and the peti

tion was filed on May 29, 1969.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the Eighth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States, which provides:

“Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive

fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments

inflicted.”

It involves the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

It further involves Cal. Penal Code §§ 187, 188, 189, 190,

190.1, 3604 and 3605, which are set forth in Appendix A

to this brief [hereafter cited as App. A, pp .____ infra], at

App. A, pp. la-3a infra.2

QUESTION PRESENTED

Does the imposition and carrying out of the death penalty

in this case constitute cruel and unusual punishment in vio

lation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments?

2 Following the date of petitioner’s conviction and sentence, two

provisions of the California murder statutes were amended in partic

ulars not here relevant. The present form of the provisions is also set

forth in the same appendix, App. A, pp. 3a-4a, infra.

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Following a bench trial in the Superior Court of Ventura

County, petitioner Earnest James Aikens, Jr., was convicted

of the first-degree murder of Mrs. Mary Winifred Eaton, on

April 26, 1965, and was sentenced to die for that offense.

In consolidated proceedings, he was at the same time con

victed of the first-degree murder of Mrs. Kathleen Nell Dodd

on April 3, 1962, and sentenced to life imprisonment pur

suant to Cal. Penal Code § 190.1,3 which prohibits the im

position of the death penalty upon any person who was

under the age of eighteen when the murder was committed.

Petitioner was not quite seventeen when Mrs. Dodd was

murdered, and was twenty at the time of the murder of

Mrs. Eaton.

Both of these killings were unmitigated atrocities, com

mitted during robberies and rapes of the victims after the

killer had entered their homes. Although not overwhelm

ing, the circumstantial evidence presented by the prosecu

tion was sufficient to identify petitioner as the killer. In

the penalty trial that followed his conviction of Mrs. Eaton’s

murder,4 the prosecution also showed that petitioner had

committed a third first-degree murder on June 7, 1962 and

a forcible rape on December 25, 1962. The trial court

found that:

“Earnest Aikens has since the age of eleven years

of age, or thereabouts, been involved in an almost

continuous pattern of anti-social and criminal behav

ior of one sort or another. He has graduated from

petty and minor nuisances and offenses through

more serious proceedings that have involved Juvenile

Court wardship and a commitment to Los Prietos

Boys’ School and to more recent commitments at

3App. A, pp. 2a-3a infra.

4 This Court is familiar with the two-stage procedure provided by

California law for the trial of capital cases. See McGautha v. Califor

nia, 402 U.S. 183 (1971).

4

the Preston School of Industry and the Youth Train

ing School, both administered by the California

Youth Authority. In the instances of his parole

from the Authority level, his periods of surcease

from criminal behavior have been of short duration.

Now he stands convicted of two brutal, cold-blooded

and vicious killings, together with the finding that I

have here earlier made of his responsibility for a

third homicide. Interspersed with the foregoing have

been instances of assault, rape and robbery. Such

record, at the very least, demonstrated an indiffer

ent, arrogant and obvious disregard for the dignity

and value of human life and the rights of others.”

(Tr. 4987)

The court credited psychiatric findings that petitioner was

a sociopath (Tr. 4987-4989); found that he had not bene

fited from rehabilitative efforts in the past (Tr. 4988, 4991)

and was not very likely to benefit from them in the future

(Tr. 4988-4989);5 found that his criminal behavior was not

substantially explained or mitigated by his upbringing in a

fatherless and economically deprived family (Tr. 4989-4991),

but was attributable to his failure to use those opportunities

that society had given him for a free education and later

for institutional rehabilitation (Tr. 4990-4991); and, in view

of his “multiple and aggravated crimes . . . against the vic

tims . . . involved and, indeed, against society in general”

(Tr. 4992), concluded that he should be put to death (ibid).

Petitioner’s crimes were indeed aggravated. Mrs. Eaton

was a woman in her sixties, the mother of an acquaintance

of petitioner’s. While she was home alone in the middle of

the day, her house was entered; her money and a sharp

knife from her kitchen were taken; she was led to a bed

room; her arms were tied behind her with two belts; and

she was then raped and killed by several wounds of the

5 Although this last conclusion is expressed in terms of the views

of the psychiatrists, it appears that the court was itself of the same

view.

5

knife that plainly establish a deliberate and intentional

murder.

Mrs. Dodd was twenty-five years old and five months

pregnant when she was killed. Her house was entered in

the late evening, while her husband was away and her two

young children were sleeping. She ran or was taken from

the house to a railroad embankment in the area, where she

was raped. She then ran from the embankment, was over

taken in a neighbor’s driveway, and was killed by numerous

stabs of a knife that had been removed from her kitchen.

Money was also removed from Mrs. Dodd’s house.

A more detailed statement of the evidence relating to the

killings of Mrs. Eaton and Mrs. Dodd is set forth in Appen

dix B to this brief. We do not place it here because it is

lengthy and is not material to our constitutional submission

in this Court. Our submission is that the penalty of death

is a cruel and unusual punishment for the crime of first-

degree murder—or for any other civilian, peacetime crime-

no matter how aggravated. We make no claim that if the

death penalty can constitutionally be inflicted for any such

crime, it cannot be inflicted upon this petitioner.

His were ghastly crimes—as any intentional killing of a

human being is a ghastly crime—and were attended by aggra

vating features that must necessarily arouse the deepest

human instincts of loathing and repugnance. But the issue

before this Court cannot turn upon those features. This is

so because if the state may constitutionally punish peti

tioner’s crimes with death, it may also constitutionally use

death to punish murders unattended by the same features.

California’s statutes and its courts in fact do so; and we can

conceive no Eighth Amendment principle which, allowing

death punishment in the particular circumstances of this

case, could confine it to them. Cf. Furman v. Georgia, O.T.

1971, No. 69-5003.

6

HOW THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION WAS

PRESENTED AND DECIDED BELOW

California’s automatic appeal statute in death penalty

cases (Cal. Penal Code § 1239) imposes upon the California

Supreme Court an obligation to consider all legal errors

appearing in the record of a capital case. E.g., People v.

Stanworth, 71 Cal.2d 820, 457 P.2d 889, 80 Cal. Rptr. 49

(1969); People v. Robinson, 61 Cal.2d 373, 388 n. 14, 392

P.2d 970, 979 n. 14, 38 Cal. Rptr. 890, 899 n. 14 (1964).

Pursuant to that obligation, the Supreme Court here

sustained the constitutionality of the death penalty, 70 Cal.

2d at 380, 450 P.2d, at 265, 74 Cal. Rptr., at 889, under

authority of In re Anderson, 69 Cal.2d 613, 447 P.2d 117,

73 Cal. Rptr. 21 (1968), which had rejected the claim that

it was a cruel and unusual punishment forbidden by the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The penalty of death for first-degree murder is a cruel

and unusual punishment because it affronts the basic stand

ards of decency of contemporary society. Those standards

are manifested by a number of objective indicators which

this Court can properly notice, but principally by the

extreme rarity of actual infliction of the death penalty in

the United States and the world today. Worldwide and

national abandonment of the use of capital punishment

during this century has accelerated dramatically, and has

now become nearly total.

In historical context, this development marks an over

whelming repudiation of the death penalty as an atavistic

barbarism. The penalty remains on the statute books only

to be—and because it is—rarely and unusually inflicted. So

inflicted, it is not a part of the regular machinery of the

state for the control of crime and punishment of criminals.

It is an extreme and mindless act of savagery, practiced

upon an outcast few. This is exactly the evil against which

the Eighth Amendment stands.

7

If the death penalty is declared unconstitutional, “ [t]he

State thereby suffers nothing and loses no power. The pur

pose of punishment is fulfilled, crime is repressed by penalties

of just, not tormenting, severity, its repetition is prevented,

and hope is given for the reformation of the criminal.” 6 In

the debates upon the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty)

Bill of 1965, Lord Chancellor Gardiner made the basic point

of our argument. “When we abolished the punishment for

treason that you should be hanged, and then cut down

while still alive, and then disembowelled while still alive,

and then quartered, we did not abolish that punishment

because we sympathised with traitors, but because we took

the view that it was a punishment no longer consistent with

our self-respect.” 7 Today the death penalty in any form is

inconsistent with the self-respect of a civilized people. It is

therefore prohibited by the Eighth and Fourteenth Amend

ments.

ARGUMENT

I. INTRODUCTION

This case presents the question whether the infliction of

the penalty of death for the crime of murder, in the form

in which the death penalty is administered in California and

throughout the United States in this third quarter of the

twentieth century, is a cruel and unusual punishment for

bidden by the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. That

question is, we think, an open one, uncontrolled by any

prior decision of this Court. For while the Court has several

times assumed, and expressed in dicta, that “the mere extin

guishment of life” 8 is not a constitutionally prohibited

cruel and unusual punishment, it has never focused squarely

6Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 381 (1910).

7268 HANSARD, PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (5th series)

(Lords, 43d Pari., 1st Sess., 1964-1965), 703 (1965).

8In re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436, 447 (1890) (dictum).

8

upon that issue or given it the consideration warranted by

a major question arising under the Bill of Rights, particu

larly a question upon which hundreds of human lives

depend.9

9 Analysis of this Court’s prior decisions relative to capital punish

ment demonstrates the correctness of the conclusion recently reached

by the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, that “ [t]he Court has

never held directly that the death penalty is or is not cruel and unusual

punishment.” Ralph v. Warden, 438 F.2d 786, 789 (4th Cir. 1970).

In Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1879), no constitutional conten

tion was raised on behalf of the condemned man. Id. at 136-137. The

issue presented was whether, in the absence of express statutory pro

vision, execution of a death sentence by the method of shooting was

legally authorized. The Court held that it was; and assuming what was

not questioned by Wilkerson’s counsel—that the death sentence itself

was permissible—the Court expressed the view that shooting was not a

cruel and unusual method of inflicting it. Id. at 134-136.

The cruelty of various methods of inflicting capital punishment was

also the question sought to be raised in In re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436

(1890) (electrocution); McElvaine v. Brush, 142 U.S. 155 (1891) (soli

tary confinement preceding execution; and State ex rel. Francis v.

Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 (1947) (second electrocution after first failed

for mechanical reasons). The Kemmler and McElvaine cases were

decided upon the express ground that the Eighth Amendment did not

restrict the States (136 U.S. at 447-449; 142 U.S. at 158-159), a view

that prevailed in this Court well into the twentieth century. Pervear

v. Massachusetts, 5 Wall. (72 U.S.) 475, 479480 (1867); O ’Neil v.

Vermont, 144 U.S. 323,331-332 (1892) (dictum); Collins v. Johnston,

231 U.S. 502, 510-511 (1915). Mr. Justice Frankfurter’s decisive vote

in Francis was cast on the same grounds. (329 U.S. at 466,469470.)

Thus, the Court’s expressed approval of the death penalty in the first

two cases was dictum; in the third, it was non-dispositive; and in all

three cases it was directed merely at the mode of execution of a death

sentence whose basic constitutionality was neither argued nor atten

tively considered.

We shall return shortly to the approval of the death penalty in Trop

v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 99 (1958) (plurality opinion of Chief Justice

Warren). See pp. 26-27, infra. That too was, of course, dictum, since

no death sentence was at issue in Trop. And the general pronounce

ment that the petitioner in Williams v. Oklahoma, 358 U.S. 576 (1959),

was not denied “due process of law or any other constitutional right”

{id. at 586-587), hardly speaks to the Eighth Amendment, which was

9

We make this point at the outset for two reasons. It is,

of course, important that our Eighth Amendment con

tention against the death penalty does not ask the Court

to “depart from . . . firmly established principle,” Abbate

v. United States, 359 U.S. 187, 195 (1959), or to overturn

any “deliberately decided rule of Constitutional law,” Mapp

v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643, 677 (1961) (Mr. Justice Harlan, dis

senting). To the contrary, the way is perfectly clear for

the Court to hold that the death penalty is a cruel and

unusual punishment consistently with the proper applica

tion of principles of stare decisis in constitutional adjudica

tion. But the matter goes further than that. In a very

practical as well as a jurisprudential sense, the Eighth Amend

ment question raised requires a judgment of first impression

from this Court.

In saying so, we do not naively suggest that the Court’s

prior opinions treat the constitutionality of capital punish

ment as debatable. Obviously, the Court has long and

firmly supposed its constitutionality; and if the question

had been appropriately posed in Wilkerson10 or Kemmler, 11

capital punishment plainly would have been sustained. The

same may be true as late as Francis, 12 or even Trop, 13

although it is difficult to speculate what the Court would

have concluded if a square presentation of the Eighth

Amendment question had directed its attention to the enor

mous and constitutionally significant changes which the

not invoked by Williams. See also Williams v. New York, 337 U.S.

241 (1949). In summary, no discussion of the constitutionality of

capital punishment under the Eighth Amendment has ever been made

by this Court under the circumstances of focused responsibility and

consideration which entitle constitutional decisions to precedential

weight. See, e.g., Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78, 90-92 (1970).

w Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1879), note 9 supra.

11 In re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436 (1890), note 9 supra.

n State ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 (1947), note 9,

supra.

l3Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958), note 9, supra.

10

institution of capital punishment had already undergone

between the late nineteenth century and 1947 or 1958.

Still further changes have occurred since 1958; and the

issue of the constitutionality of capital punishment today

is an altogether different issue than its validity a century

ago. Because the Court has not directly confronted the

issue during this century, it has not had occasion to con

sider the constitutional consequences of the century’s

changes; and it is for this reason that the Eighth Amend

ment question presented in 1971 must fairly be viewed

afresh, unconstrained by assumptions of the death penalty’s

validity which the Court first made in 1879 and continued

to make—without examination—twenty or a dozen years

ago.

What has happened, during the century, is an overwhelm

ing, accelerating, nation-wide and world-wide abandonment

of death as a punishment for civilian crime.14 We shall

shortly discuss the precise constitutional implications of

that evolution;15 but, upon any view, it is relevant to, and

will ultimately be decisive of, the constitutionality of capital

punishment under the Eighth Amendment. Capital punish

ment has largely gone the way of flogging and banishment,

progressively excluded by this Nation and by the civilized

nations of men from the register of legitimate penal sanc

tions. Like flogging and banishment, capital punishment is

condemned by history and will sooner or later be condemned

by this Court under the Constitution. The question is

whether that condemnation should come sooner or later.

It is whether the evolution of civility that is inexorably ren

dering the death penalty intolerable has so far advanced as

to make the Eighth Amendment take hold upon this doomed,

deadly institution; or whether the United States-following

a period of more than four years since June 2, 1967 with

out an execution-must now relapse into killing some or all

14See pp. 27-39, infra.

15See pp. 39-61, infra.

11

of the more than 660 men on its death rows before that

evolution reaches the stage at which their killings are estab

lished to be unconstitutional.

We put the issue in this way not because we enjoy the

presumptuous exercise of predicting history and the future

outcome of this Court’s decisions but because, inescapably,

that is the issue. No one can dispute, we believe, either the

fact of the evolution we describe or the legal consequence

that, at some point in its development, that evolution must

call into play the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause of

the Eighth Amendment. It must, for the same reasons that

a similar evolution has brought flogging16 and banishment17

under the Eighth Amendment’s ban. The questions then

arise: What principles should this Court use to determine

the course of historical development, and the point upon

that course, which mark a progressively repudiated punish

ment as cruel and unusual for Eighth Amendment purposes?

And with regard to capital punishment, has that course

been followed and that point been reached?

These questions are not without difficulty because, as

has frequently been noted, the Eighth Amendment itself is

not without difficulty.18 The Court’s decisions have not

undertaken to define in comprehensive terms the concept

of “cruel and unusual punishments.” 19 Different approaches

16Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F.2d 571 (8th Cir. 1968).

l l Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 102 (1958) (plurality opinion of

Chief Justice Warren); Dear Wing Jung v. United States, 312 F.2d 73,

75-76 (9th Cir. 1962).

18 Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130, 135-136 (1879); In re Kemmler,

136 U.S. 436, 447 (1890); Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349,

370, 375 (1910); Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F.2d 571, 577 (8th Cir. 1968);

Ralph v. Warden, 438 F.2d 786, 789 (4th Cir. 1970).

19Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 368-369 (1910); Trop v.

Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 100 (1958) (plurality opinion of Chief Justice

Warren); Note, The Effectiveness o f the Eighth Amendment: An

Appraisal o f Cruel and Unusual Punishment, 36 N.Y.U.L. REV. 846

(1961); Note, Revival o f the Eighth Amendment: Development o f

12

to that concept are available which would bring the death

penalty within its prohibition. The approach taken in this

brief is narrower than others that have been persuasively

argued.20 Our approach concentrates upon the particular

characteristic of capital punishment that it shares with only

a very few other punishments, notably flogging and banish

ment which have already been constitutionally forbidden.

That characteristic is extreme contemporary rarity result

ing from a demonstrable historical movement which can

only be interpreted fairly as a mounting and today virtually

universal repudiation. Today, “ [d]eath is the rarest of all

punishments for crime.” 21 So far has its repudiation

advanced that, if the United States were in fact to execute

its 660 condemned men in 1971, it would thereby become

uncontestably the greatest killer of human beings by judi

cial process in the world-probably, the killer of more men

than all other non-communist nations of the world com

bined.22 This observation speaks strongly to the question

Cruel-Punishment Doctrine by the Supreme Court, 16 STAN. L. REV.

996 (1964); Recent Decision, 5 U. RICHMOND L. REV. 392, 393

(1971).

20Goldberg & Dershowitz, Declaring the Death Penalty Uncon

stitutional, 83 HARV. L. REV. 1773 (1970); Gottlieb, Testing the

Death Penalty, 34 SO. CALIF. L. REV. 268 (1961); Bedau, The Courts,

The Constitution, and Capital Punishment, [1968] UTAH L. REV.

201; Comment, The Death Penalty Cases, 56 CALIF. L. REV. 1268

(1968).

21Sellin, The Inevitable End o f Capital Punishment, in SELLIN,

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT (1967) [hereafter cited as SELLIN (1967)],

239.

22Virtually no information is available concerning executions in

communist countries. Patrick reports an average of 535.3 executions

per year between 1958 and 1962 in the 89 countries using the death

penalty for which he could obtain data. Patrick, The Status o f Cap

ital Punishment: A World Perspective, 56 J. CRIM. L., CRIM. & POL.

SCI. 397,408 (1965). After subtraction of the 48.6 annual executions

that Patrick reports for the United States during this period (id. at

404), the remaining 88 countries conducted 486.7 executions annually.

They include all of the major death penalty countries of the world

except the communist nations and the following: Burma, Haiti, India,

13

whether death is a cruel and unusual punishment within the

meaning of the Constitution of a Nation which aspires to

be one of the world’s more enlightened peoples.

But our approach to the Eighth Amendment concentrates

primarily upon the evolution of the death penalty in the

United States itself. Properly viewed, that evolution has

brought this country to a stage at which the relevant consti

tutional indicators of a cruel and unusual punishment have

abundantly matured. America has had its time of “experi

mentation” 23 with the killing of men; the experiment has

led to one inexorable conclusion; and further development

can only make more manifest-at a terrible cost-what is

already manifest and manifestly fitting as a basis for judicial

application of the Constitution. To demonstrate why this

is so, we first discuss the nature of the Eighth Amendment’s

concern against cruel and unusual punishments, and then

proceed to test the death penalty in light of that concern.

II. THE RELEVANT EIGHTH AMENDMENT STANDARD

At the heart of the Eighth Amendment24 lurks an extra

ordinary dilemma whose resolution is, we think, the key to

decision of this case. The dilemma arises from the con

frontation of three basic principles.

Iran, Mali, Mexico (29 of whose 32 jurisdictions have legally abolished

the death penalty), Nicaragua, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Sudan and the

Republic of Viet Nam. These latter countries would therefore have

to account for more than a quarter of the executions in the non

communist world in order to bring the non-communist total, exclusive

of the United States, to 660 according to Patrick’s figures. And

Patrick’s figures appear to be unduly high. See note 51, infra.

23See Powell v. Texas, 392 U.S. 514, 536-537 (1968) (plurality

opinion of Mr. Justice Marshall); Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78, 138

(1970) (separate opinion of Mr. Justice Harlan).

24The Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause of the Eighth Amend

ment is made applicable to the States through the Due Process Clause

of the Fourteenth. Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962), so

holds; and there can be little doubt that this Bill of Rights guarantee,

14

First, in the context of American government, the Eighth

Amendment’s proscription of cruel and unusual punishments

forbids the legislative enactment of such punishments as

well as the judicial imposition of them. This has always

been accepted. Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 366,

378-379, 382 (1910); Trap v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 103-104

(1958) (plurality opinion of Chief Justice Warren); Robinson

v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962); and see Wilkerson v.

Utah, 99 U.S. 130, 133, 136-137 (1879) (dictum); In re

Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436, 446-447 (1890) (dictum).

Second, the force of the Amendment is not limited to

the prohibition of those atrocities that would have turned

the stomachs of the Framers in the Eighteenth Century.25

whose “basic concept . . . is nothing less than the dignity of man,”

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86,100 (1958) (plurality opinion of Chief

Justice Warren), satisfies the most restrictive test for adoption as a

measure of due process. Its derivation from times anterior to Magna

Carta (see Granucci, “Nor Cruel and Unusual Punishments Inflicted: ”

The Original Meaning, SI CALIF. L. REV. 839, 845-846 (1969))

through the Bill of Rights of 1689 (1 Wm. & Mary, sess. 2, ch. 2, pre

amble, clause 10) amply establishes that it is a “ ‘principle of justice so

rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people as to be ranked

as fundamental.’ ” Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319; 325 (1937).

The point did not escape Patrick Henry in 1788. “What has distin

guished our ancestors?—That they would not admit of tortures, or

cruel and barbarous punishment.” 3 ELLIOT, DEBATES IN THE

SEVERAL STATE CONVENTIONS ON THE ADOPTION OF THE

FEDERAL CONSTITUTION (1863), 447.

For convenience, we shall speak simply of the Eighth Amendment

throughout this brief, meaning thereby the Cruel and Unusual Punish

ment Clause as it measures the liberty protected by the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

25Certainly the Eighth Amendment does bar those atrocities, but

they mark only the core of minimum content of its prohibition. This

is what was meant in Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130,136 (1879), by

the observation that, although the exact extent of the Cruel and

Unusual Punishment Clause is difficult of definition, “it is safe to

affirm that punishments of torture . . . , and all others in the same line

of unnecessary cruelty, are forbidden.” Wilkerson does not suggest,

as the Weems dissent seems to imply, that torture is the outer limit

of the Amendment. Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 400-401

15

This conclusion is compelled by both authority and reason.

“ [I]t is a constitution we are expounding,” 26 and the Con

stitution “states or ought to state not rules for the passing

hour, but principles for an expanding future.” 27 'Thus,

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958), outlawed the hoary

penalty of banishment with the observations that the scope

of the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause “is not static,”

and that the “Amendment must draw its meaning from the

evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a

maturing society.” (Id., at 101 (plurality opinion of Chief

Justice Warren).) See also Robinson v. California, 370 U.S.

660, 666 (1962) (referring to “the light of contemporary

human knowledge”); Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F.2d 571, 578-

580 (8th Cir. 1968); Goss v. Bomar, 337 F.2d 341,342-343

(6th Cir. 1964) (dictum). Such a conception of evolving

standards is a constitutional commonplace,28 and is firmly

(1910) (Mr. Justice White, dissenting). Nor could the Amendment be

so limited for the reasons stated convincingly by the majority in

Weems:

“. . . [Sjurely [the Framers] . .. intended more than to

register a fear of the forms of abuse that went out of practice

with the Stuarts. Surely, their jealousy of power had a saner

justification than that. They were men of action, practical

and sagacious, not beset with vain imagining, and it must have

come to them that there could be exercises of cruelty by

laws other than those which inflicted bodily pain or mutila

tion. . . . [I] f we are to attribute an intelligent providence

to [the Eighth Amendment’s] . . . advocates we cannot think

that it was intended to prohibit only practices like the Stuarts,

or to prevent only an exact repetition of history. We cannot

think that the possibility of a coercive cruelty being exercised

through other forms of punishment was overlooked.” (Id.

at 372-373.)

26M ’Culloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316, 407 (1819).

27c a r d o z o , t h e n a t u r e o f t h e ju d ic ia l pr o c e ss

(1921), 83.

2SE.g.,Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483,492493 (1954)

(“In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the clock back to 1868

when the [Fourteenth] Amendment was adopted . . . .”); Ex parte Wil

son, 114 U.S. 417, 427-428 (1885) (“What punishments shall be con

sidered as infamous [for purposes of the Fifth Amendment’s indictment

16

entrenched in the jurisprudence of the Eighth Amendment

in particular. The Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause

requirement] may be affected by the changes of public opinion from

one age to another.”) Reference was made to Wilson and to Mackin

v. United States, 117 U.S. 348, 351 (1886), in Weems v. United States,

237 U.S. 349,378 (1910), which canvassed the subject in this frequently

quoted passage:

“Legislation, both statutory and constitutional, is enacted,

it is true, from an experience of evils, but its general language

should not, therefore, be necessarily confined to the form that

evil had theretofore taken. Time works changes, brings into

existence new conditions and purposes. Therefore a principle

to be vital must be capable of wider application than the

mischief which gave it birth. This is peculiarly true of con

stitutions. They are not ephemeral enactments, designed to

meet passing occasions. They are, to use the words of Chief

Justice Marshall, ‘designed to approach immortality as nearly

as human institutions can approach it.’ The future is their

care and provision for events of good and bad tendencies of

which no prophecy can be made. In the application of a

constitution, therefore, our contemplation cannot be only of

what has been but of what may be. Under any other rule a

constitution would indeed be as easy of application as it

would be deficient in efficacy and power. Its general prin

ciples would have little value and be converted by precedent

into impotent and lifeless formulas. Rights declared in words

might be lost in reality. And this has been recognized. The

meaning and vitality of the Constitution have developed

against narrow and restrictive construction. There is an

example of this in Cummings v. State o f Missouri, 4 Wall. 277,

where the prohibition against ex post facto laws was given a

more extensive application than what a minority of this

court thought had been given in Calder v. Bull, 3 Dali. 386.

See also Ex parte Garland, 4 Wall. 333. The construction of

the 14th Amendment is also an example, for it is one of the

limitations of the Constitution. In a not unthoughtful opin

ion Mr. Justice Miller expressed great doubt whether that

Amendment would ever be held as being directed against any

action of a State which did not discriminate ‘against the

negroes as a class, or on account of their race.’ Slaughterhouse

Cases, 16 Wall. 36, 81. To what extent the Amendment has

expanded beyond that limitation need not be instanced.

“There are many illustrations of resistance to narrow con

structions of the grants of power to the National Government.

One only need be noticed, and we select it because it was

made against a power which more than any other is kept

present to our minds in visible and effective action. We mean

17

“may be therefore progressive, and is not fastened to the

obsolete but may acquire meaning as public opinion becomes

enlightened by a humane justice.” Weems v. United States,

217 U.S. 349, 378 (1910).

To deny this dynamic character to the Eighth Amendment

would produce inconceivable results. Appendix C to this

brief sets forth some of the punishments legally in force

and commonly in use in this country during the period

when the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause was written

and adopted. If 1791 is indeed the constitutional bench

mark and if the Constitution does not forbid capital punish

ment today upon the theory that it was widely allowed by

law and practice in 1791, then the Eighth Amendment also

does not forbid today—and will never forbid—the stocks and

the pillory, public flogging, lashing and whipping on the

bare body,29 branding of cheeks and forehead with a hot

the power over interstate commerce. This power was deduced

from the eleven simple words, ‘to regulate commerce with

foreign nations and among the several States.’ The judgment

which established it was pronounced by Chief Justice Marshall

(Gibbons v. Ogden), and reversed a judgment of Chancellor

Kent, justified, as that celebrated jurist supposed, by a legis

lative practice of fourteen years and fortified by the opinions

of men familiar with the discussions which had attended the

adoption of the Constitution. Persuaded by such considera

tions the learned chancellor confidently decided that the

Congressional power related to ‘external, not to internal, com

merce,’ and adjudged that under an act of the State of New

York, Livingston and Fulton had the exclusive right of using

steamboats upon all of the navigable waters of the State. The

strength of the reasoning was not underrated. It was sup

ported, it was said, ‘by great names, by names which have all

the titles to consideration that virtue, intelligence and office

can bestow.’ The narrow construction, however, did not pre

vail, and the propriety of the arguments upon which it was

based was questioned. It was said, in effect, that they sup

ported a construction which ‘ would cripple the government

and render it unequal to the objects for which it was declared

to be instituted, and to which the powers given, as fairly

understood, render it competent’. . . . ” (Id. at 373-375.)

29Whipping was not thought to be a particularly serious punish

ment in the late eighteenth century. “ [B]y the first Judiciary Act of

the United States, whipping was classed with moderate fines and short

18

iron, and the slitting, cropping, nailing and cutting off of

ears. Further discussion of a “static” theory of the Eighth

Amendment seems unnecessary.30

Third, in applying the Eighth Amendment to advancing

and changing times, the courts are to be guided by the

touchstone of “contemporary human knowledge,” 31 “pub

lic opinion . . . enlightened by a humane justice,” 32 and

“the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress

of a maturing society.” 33 What other standards, after all,

could possibly be used? Surely it was not the purpose of

the Eighth Amendment that succeeding generations of

judges should mirror in it their own, individual philosophies

of the criminal sanction. So, if the obsolete and eldritch

customs of 1791 are not to be perpetually controlling,

where else may judges look but to enlightened public opin

ion for conception of the “cruel and unusual punishments”

which the Constitution forbids?

And there stands the dilemma. Quite perceptibly, an

extreme difficulty must attend any process of constitutional

adjudication by which this Court subjects legislation to the

terms of imprisonment in limiting the criminal jurisdiction of the Dis

trict Courts to cases ‘where no other punishment than whipping, not

exceeding thirty stripes, a fine not exceeding one hundred dollars, or

a term of imprisonment not exceeding six months, is to be inflicted.’

Act of September 24,1789, chap. 20, § 9; 1 Stat. at L., 77.” Ex parte

Wilson, 114 U.S. 417, 427-428 (1885).

30The argument has sometimes been advanced that the Eighth

Amendment cannot forbid capital punishment consistently with the

indictment clause of the Fifth, which speaks of (and, so the argument

goes, constitutionalizes) “capital . . . crime.” This reasoning, like the

static theory of the Eighth Amendment generally, proves too much.

For the double jeopardy clause of the constitution also speaks of “jeo

pardy of life or limb.” (Emphasis added.)

31 Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660, 666 (1962).

32Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 378 (1910).

33Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 100 (1958) (plurality opinion of

Chief Justice Warren).

19

test of “enlightened public opinion,” and adjudges the

validity of a legislature’s product according to society’s

“standards of decency.” For, both in constitutional con

templation and in fact, it is the legislature, not the Court,

which responds to public opinion and immediately reflects

the society’s standards of decency. If the question asked

by the Eighth Amendment really be whether our democratic

society can tolerate the existence of any particular penal law

that is on the books, the Eighth Amendment’s answer will

always be that it can—and for the simple reason that the

law is on the books of a democratic society.34 The conclu

sion therefore seems to be required either that the Eighth

Amendment is not a judicially enforceable restriction upon

legislation;35 or that the Weems-Trop test referring to con

temporary public standards of decency is not a usable mea

sure of the Amendment; or else that the question which we

have just posed is not the proper question to which the

Amendment and the Weems-Trop test respond.

As this way of putting the matter suggests, we think that

the question—whether the maintenance of a particular harsh

penalty on the statute books is consistent with prevailing

standards of decency—is the wrong question. We suggest

what we think is the right one below. For we cannot

believe that the Eighth Amendment is not a restriction upon

34Mr. Justice Story therefore wrote that the Eighth Amendment

“would seem to be wholly unnecessary in a free government, since it

is scarcely possible that any department of such a government should

authorize or justify such atrocious conduct” as the Amendment for

bids. 2 STORY, COMMENTARIES ON THE CONSTITUTION OF

THE UNITED STATES (4th ed. 1873), 623. This observation has

undoubted merit with regard to penal laws that are generally and

uniformly enforced, but it is inapplicable to selectively and rarely

enforced punishments. Precisely in regard to such “cruel and unusual

punishments,” the Amendment is most necessary.

35See State v. Cannon, 55 Del. 585,190 A.2d 514 (1963), sustaining

the punishment of whipping in an opinion which effectively denies any

judicial review of legislation under the Cruel and Unusual Punish

ment Clause.

20

cruel and unusual penal legislation rightly enforceable by

this Court. Nor can we believe that the Amendment’s pro

hibition is restricted to live disembowelment and similar

long-gone butcheries—nor, on the other hand, that it inyokes

the unassisted penological impressions of particular Justices.

The Weems-Trop test is, we submit, the proper one. Com

mon standards of decency in our contemporary society do

set the limits of punishment allowable under the Eighth

Amendment. The problem is how those standards are to

be ascertained, and with regard to what specific question.

We begin with the specific question. When a man such

as Earnest Aikens comes before the Court claiming that the

law under which he was sentenced provides for an uncon

stitutional cruel and unusual punishment, the question is

not: will contemporary standards of decency allow the

existence of such a general law on the books? The ques

tion is, rather: will contemporary standards of decency

allow the general application of the law’s penalty in fact?

The distinction which we draw here lies between what

public conscience will allow the law to say and what it will

allow the law to do—between what public decency will per

mit a penal statute to threaten and what it will allow the

law to carry out—between what common revulsion will for

bid a government to put upon its statute books as the

extreme, dire terror of the State (not to be ordinarily, regu

larly or in other than a few rare cases enforced), and what

public revulsion would forbid a government to do to its

citizens if the penalty of the law were generally, even-

handedly, non-arbitrarily enforced in all of the cases to

which it applied.

This last point—regarding general, even-handed, non-

arbitrary application—is critical. For in it lies, we think,

a large part of the need to have a Cruel and Unusual Punish

ment Clause in the Constitution, and of the need to have

courts enforce it. The government envisaged for this coun

try by the Constitution is a democratic one, and in a demo

cracy there is little reason to fear that penal laws will be

placed upon the books which, in their general application,

21

would affront the public conscience. The real danger con

cerning cruel and inhuman laws is that they will be enacted

in a form such that they can be applied sparsely and spottily

to unhappy minorities, whose numbers are so few, whose

plight so invisible, and whose persons so unpopular, that

society can readily bear to see them suffer torments which

would not for a moment be accepted as penalties of general

application to the populace.36

36 A recent detailed analysis of the historical origins of the cruel

and unusual punishment clause of the Eighth Amendment demonstrates

that the provision of the English Bill of Rights of 1689 from which

the Eighth Amendment’s language was taken verbatim was concerned

primarily with the irregular, selective application of harsh (but not

intrinsically barbaric) punishments; and that its cardinal aim was to

forbid the oppressive exercises of a legally unregulated power to mete

out severe punishments arbitrarily. Granucci, “Nor Cruel and Unusual

Punishments Inflicted: ” The Original Meaning, 57 CAL. L. REV. 839,

845-847, 852-860 (1969). To be sure, Granucci also finds that the

American Framers imperfectly understood the English background of

the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause, and that they were them

selves principally concerned with the problem of intrinsically barbaric

penalties. But this does not support a conclusion that the Framers

meant to wholly alter the meaning of the guarantee which they found

in th ■ English traditions, or to reject protections of the citizen long

prescx/ed by their English heritage.

The debates in Congress and in the ratifying conventions concern

ing the Eighth Amendment are set forth in Appendix D to this brief.

Discussion of the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause was notably

brief; and only one or two of those who voted for it spoke. What

they said unquestionably sustains the view that they meant to include

in the guarantee a proscription of inherently barbarous penalties. It

does not sustain the view that they meant to jettison other restrictions

upon punishment which were encompassed by the language that they

took as embodying the basic rights of the citizen evolved through the

course of English history. To the contrary, it is apparent that the

principal motive force behind inclusion of the Eighth Amendment in

the Constitution was the relatively simple and imprecise notion that

its guarantees had always been recognized as restrictions upon English

government, and that the new national government established by the

Constitution and given considerable powers over individuals could not

safely be unleashed from the same safeguards.

22

Herein is found the difference between the judgment

which the legislator makes, responding politically to public

conscience, and the judgment which a court must make

under the obligation that the Eighth Amendment imposes

upon it to respond rationally to public conscience. A legis

lator may not scruple to put a law on the books (still less,

to maintain an old law on the books) whose general, even-

handed, non-arbitrary application the public would abhor—

precisely because both he and the public know that it will

not be enforced generally, even-handedly, non-arbitrarily.

But a court cannot sustain such a law under the Eighth

Amendment. It cannot do so because both the Amendment

itself and our most fundamental principles of due process

and equal protection forbid American governments the

devices of arbitrariness and irregularity, even as a sop to

public conscience.

To put the matter another way, there is nothing in the

political process by which public opinion manifests itself

in legislated laws that protects the isolated individual from

being cruelly treated by the state. Public conscience often

will support laws enabling him to be so mistreated, provided

that arbitrary selection can be made in such a fashion as to

keep his numbers small and the horror of his condition

mute.37 Legislators neither must nor do take account of

37William Forsyth wrote:

“ .. . When in respect of any class of offenses the difficulty

of obtaining convictions is at all general in England, we may

hold it as an axiom, that the law requires amendment. Such

conduct in juries is the silent protest of the people against its

undue severity. This was strongly exemplified in the case of

prosecutions for the forgery of bank-notes, when it was a

capital felony. It was in vain that the charge was proved.

Juries would not condemn men to the gallows for an offense

of which the punishment was out of all proportion to the

crime; and as they could not mitigate the sentence they

brought in verdicts of Not Guilty. The consequence was, that

the law was changed; and when secondary punishments were

substituted for the penalty of death, a forger had no better

chance of an acquittal than any other criminal. Thus it is

that the power which juries possess of refusing to put the law

in force has, in the words of Lord John Russell, ‘been the

23

such individuals.38 But it is the precise business of courts

to take account of them, and to disallow under the Eighth

Amendment the application to them of penalties so harsh