Negro Teachers Will be Protected - Marshall

Press Release

May 20, 1955

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Negro Teachers Will be Protected - Marshall, 1955. 1e9fe102-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e5e9d3d9-1a8d-4190-8cca-8a77886ec902/negro-teachers-will-be-protected-marshall. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

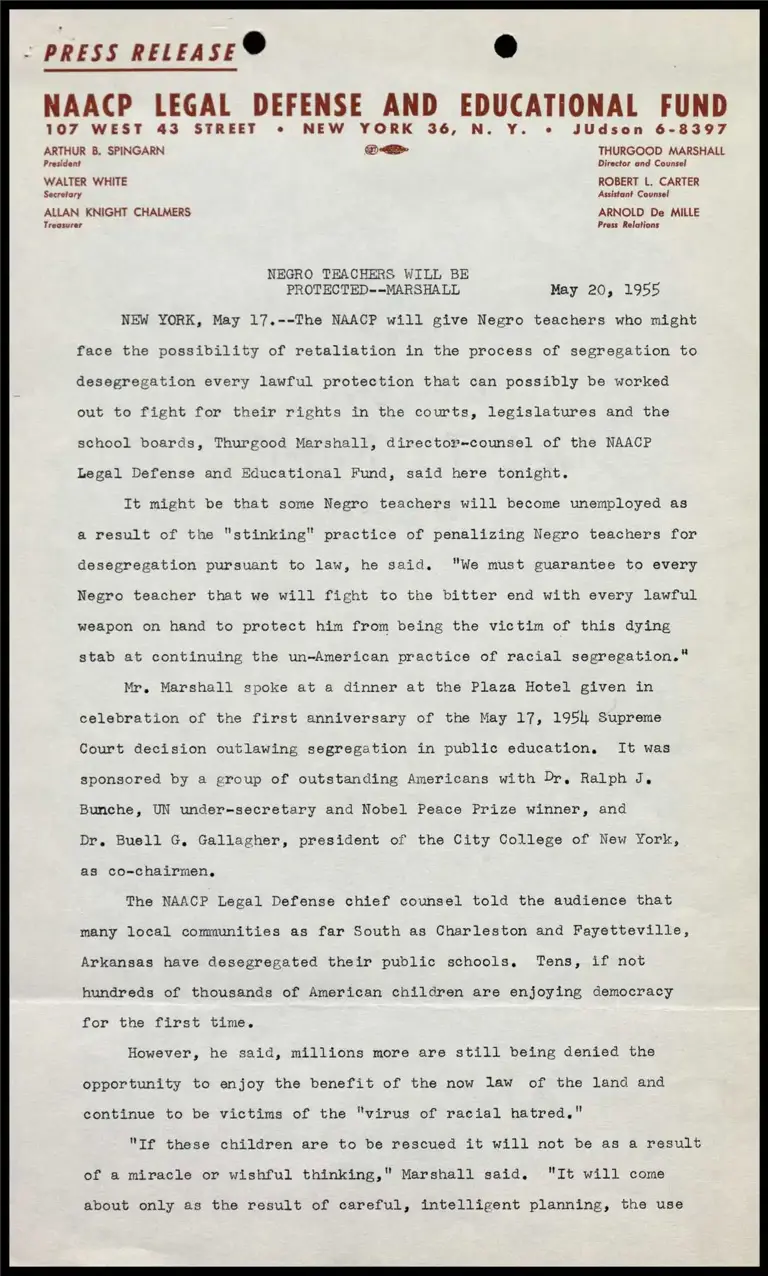

- PRESS RELEASE® e

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

107 WEST 43 STREET *© NEW YORK 36, N. Y. © JUdson 6-8397

ARTHUR B. SPINGARN oS THURGOOD MARSHALL

President Director ond Counsel

WALTER WHITE ROBERT L. CARTER

Secretary Assistant Counsel

ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS ARNOLD De MILLE

Treasurer Pross Relations

NEGRO TEACHERS WILL BE

PROTECTED--MARSHALL May 20, 1955

NEW YORK, May 17.--The NAACP will give Negro teachers who might

face the possibility of retaliation in the process of segregation to

desegregation every lawful protection that can possibly be worked

out to fight for their rights in the courts, legislatures and the

school boards, Thurgood Marshall, director-counsel of the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, said here tonight.

It might be that some Negro teachers will become unemployed as

a result of the "stinking" practice of penalizing Negro teachers for

desegregation pursuant to law, he said. "We must guarantee to every

Negro teacher that we will fight to the bitter end with every lawful

weapon on hand to protect him from being the victim of this dying

stab at continuing the un-American practice of racial segregation."

Mr. Marshall spoke at a dinner at the Plaza Hotel given in

celebration of the first anniversary of the May 17, 195 Supreme

Court decision outlawing segregation in public education. It was

sponsored by a group of outstanding Americans with Dr, Ralph J.

Bunche, UN under-secretary and Nobel Peace Prize winner, and

Dr. Buell G, Gallagher, president of the City College of New York,

as co-chairmen,

The NAACP Legal Defense chief counsel told the audience that

many local communities as far South as Charleston and Fayetteville,

Arkansas have desegregated their public schools, Tens, if not

hundreds of thousands of American children are enjoying democracy

for the first time.

However, he said, millions more are still being denied the

opportunity to enjoy the benefit of the now law of the land and

continue to be victims of the "virus of racial hatred."

"If these children are to be rescued it will not be as a result

of a miracle or wishful thinking," Marshall said. "It will come

about only as the result of careful, intelligent planning, the use

aoe

of all scientific and legal know-how, Above all, we must have the

coordination and use of all available resources in every community."

Marshall advised the gathering that one of the crudest boot-

strap arguments advanced by the Southern politicians is: "Because

we have denied the Negro full equality by enforced segregation we

cannot now allow him to escape segregation because he is not equal!"

"This is much like the story of the man who, when on trial for

the murder of his father and mother, pleaded for mercy because he

was an orphan," he asserted.

Special tribute was paid to Mr. Marshall and his legal staff

for leadership in the battle against segregation and discrimination

in American life. The dinner was attended by 525 persons.

Adlai HE. Stevenson, former governor of Illinois and 1952

Democratic presidential candidate, made a brief appearance on his

way home froma l-week tour of Africa, He lauded the NAACP Legal

Defense lawyers for their continued and successful campaigns against

the un-American practices of which Negroes are victims.

Principal speaker was N, Y, Attorney General Jacob K, Javits

who became a last-minute substitute for Harold E, Stassen, He said

the courts have done their part in vindicating the Constitution as

to equality of opportunity for all Americans regardless of race,

ereed, color or national origin.

"It is the legislatures, national and state, in which the prin-

cipal effort needs now be made," Javits explained, "The twin objec-

tives of the foes of discrimination and segregation in the country

need now to be equality of opportunity in employment and equality of

opportunity in housing."

Dr. Channing H, Tobias, chairman of the NAACP Board, told the

dinner patrons that there is no law that gives to any citizen in a

democracy the right to pass judgment on what is good and what is not

good for any other citizen.

"The only criterion of judgment is what is right and what is

not right according to the law of the land," he said.

Roy Wilkins, newly elected executive secretary of the NAACP,

gave a report of the propress of desegregation across the country.

He paid particular tribute to the parents and children in the

school segregation cases.

Mr, Marshall called upon those who believe in Americanism

based upon a government of law to "reaffirm our determination to

eradicate race, caste and religion as determining factors from

American life."

"There must be no compromise of principal," he concluded,

"We cannot settle for less than our Constitution guarantees."

-30-

TUREAUD-LOUISIANA $

SEGREGATION CASE BACK

) UNIVERSITY

FEDERAL COURT May 20, 1955

NEW ORLEA NS, May 19.--The Louisiana State University segrega-

tion case reached the federal courts again today for the seventh

time as attorneys for NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund seek

an affirmance of an order whereby young Alexander P, Tureaud of New

Orleans would be readmitted to the University Agricultural and

Mechanical College without further delay.

In a brief filed in the U. S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit here today in behalf of young Tureaud, his lawyers ask the

court to uphold a second order of the federal district court admit-

ting the youth to the undergraduate college,

The case was f st taken to the U. S. District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana at New Orleans on August 27, 1953

which issued, on September 11, an order restraining the president

and Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University and A. & M.

College from refusing to admit Tureaud to college. Tureaud was

admitted to the college on September 15, 1953. The University

appealed.

The injunction order was vacated by the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on the ground that the case should

have been heard before a three-judge district court, and remanded

the case to the district court for this purpose.

NAACP attorneys who had argued that a three-judge court was

unnecessary, applied immediately to the U. S, Supreme Court for a

stay of the Circuit Court's ruling pending review by the high court.

However, before the Supreme Court could stay the Circuit Court

action, attorneys for the University officials secured a disolution

of the injunction against them by the district court based on the

Circuit Court's mandate.

e «

ae

Pursuant to this Tureaud was promptly expelled from the college

on November 11, 1953. On November 16, 1953 the U. S. Supreme Court

issued an order staying the circuit court's action pending review by

it.

On May 2, 19:4 the high court vacated the circuit court's orcer

and remanded the case to the latter: court for reconsideration in the

light of the School Segregation Cases, The circuit court then

remanded the case to the district court for reconsideration in the

lirht of the historic. decision of May 17, 1954. This resulted in

the second injunction order.

From this second injunction order, the University officials

againappealed to the Fit’th Circuit where argument on the case will be

heard today. An application for a stay of the district courts

second injunction order pending appeal to the circuit court was

denied by it on April 18, 165, but an early hearing date was set.

In seeking to have Tureaud's readmission sustained, NAACP Legal

Defense attorneys argue that the Circuit Court erred in reversing

the first order since the district court's order was 'tlearly under

the applicable constitutional standards."

"In view of the school segregation cases, a single judge clearly

has authority to enjoin the exclusion of a Negro from a state uni-

versity solely because of his race and color," the lawyers say.

They point out that the U. S. Supreme Court in a sweeping and

clear-cut opinion held that "in the field of public education the

doctrine of separate but equal has no place, Separate educational

facilities are inherently unequal."

There is no lonser any doubt that a state policy maintaining

racially segregated public educational facilities is contrary to the

constitutional mandate of the Fourteenth Amendment, they contend.

In the lipht of these decisions (segregated school cases) no

state policy, which sees to maintain as a part of the state's pub-

lic educational system segregated schools for Negro and white stu-

dents, meets with the requirements of the federal constitution.

The issue in this case--Tureaud'!s right not to be excluded from

the Louisiana State University on the basis of his race--no longer

® *

=e 2

presents a substantial federal questi.on

onvening of a three-judge court, the

The brief was filed in behalf of young

A. P. Tureaud, Sr., U. S. Tate of Jallas, a

New Yor:

30m