United States v. Texas Education Agency (Austin Independent School District) Brief for Defendants-Appellees

Public Court Documents

September 21, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Texas Education Agency (Austin Independent School District) Brief for Defendants-Appellees, 1971. 79d20dac-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e634518c-5d64-419e-bcfe-1506a4fd3173/united-states-v-texas-education-agency-austin-independent-school-district-brief-for-defendants-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

L i /

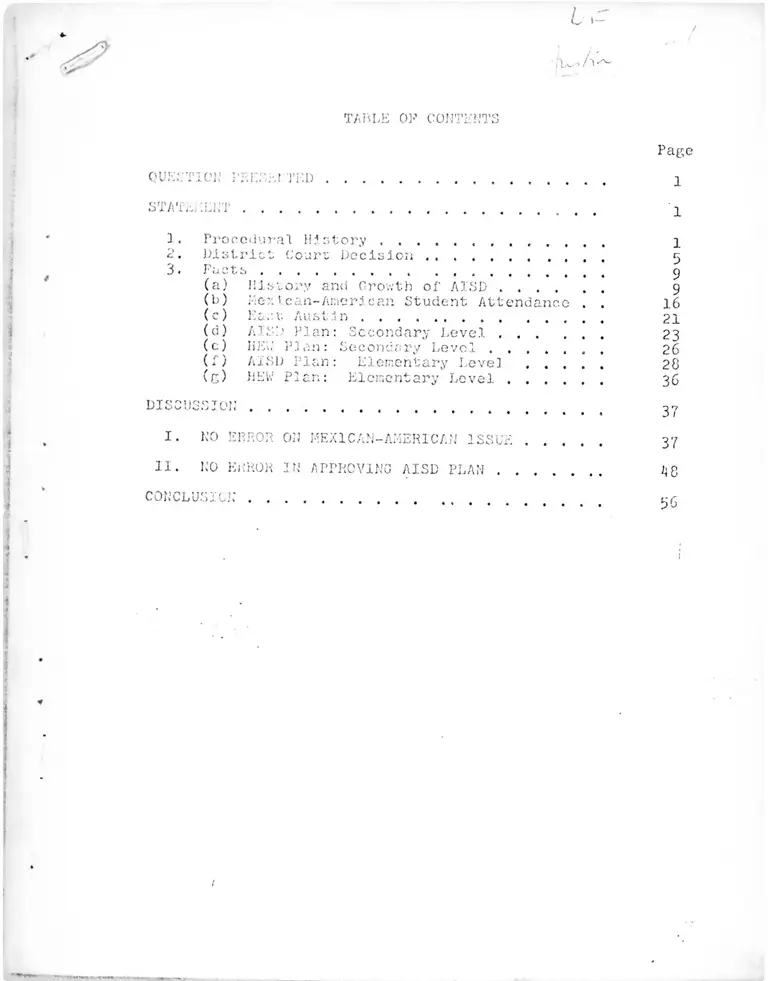

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTION PRESENTED

STATEMENT

Page

.1

1

1 .

2.

3.

Procedural History ............ , ,

District Court Decision ......... . . .

Facts...................................

(a) History and Growth of AISD . . . .

(H) tfexican-American Student Attendance(c) East Austin ................ . . .

(d) AISD Plan: Secondary Level . . .

(c) HEW Plan: Secondary Level ........

(f) AISD Plan: Elementary Level . . .

(g) HEW Plan: Elementary Level . . . .

1

5

9

916

21

2326

28

36

DISCUSSION . .

I. NO ERROR ON

11. no error IN

V\ E X1C A N - A Vi E R1C A N IS S U E

APPROVING AISD PLAN .

37

4 8

4

TABLE OF CITATIONS

V

Page

Alvarado v. El Paso Independent School District,

“"No.” 71-1555 (5th Cir, , decided June id, I9Y-T)...... 47

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953)................ 4 3

Bivins v. Bibb County Board of Education, 424 F.2d

97 (5th Cir. 1970).................................. 54

Cisneros v. Corpus Christ! Independent School

District, 3Ĥ F. Supp. 599 (S .D. Tex., 1970)

(No. 71-2397 on appeal)............. ............... 47

Davis v. School District, City of Pontiac, 309

F. Supp. 73̂ 7, aff'd 44 3 F.2d 573 (6th Cir. 1971).... 38,37,47

Delgado v. Bastrop Independent School District,

C. A. i.'o. 37TB (W.D. Tex. June 15, 1948)

(unreported) Preshall ............................. 37

Gonzales v. Sheely, 96 F. Subp. 1004 (D. Ariz.

19517 .............................................. 47

Green v. New Kent County, 391 U.S. 4 30 (1968)........ 4 8

Hernandez v. Driscoll Consol. Indenendent School

District, TTTTace NeXT ETRT~J29 Or.U7~TexT 1~95T).... 37,4 C

Hernandez v. Texas, 34 7 U.S. 4 75 (1951|).............. 47

Independent School District v. Salvatierra, 33 S.W.

2d 790 (Tex. Civ. App., 1930), cert. den. 284

u.s. 580 (1931)..................................... 37

Mendez v. Westminster School District, 64 F. Suop.

5IT4 (S.D. Cal. 19463, aff'd lFl F.2d 774 (9th Cir.-

1 947) ......................... .................... 47

Romero v. Weakley, 226 F.2d 399 ( 9th Cir. 1955)...... 47

Ŝ ijnr,leion v, ucicKtsoii fuiinlcip̂ l S6p^r&t/6 octiooi

7ystew/'JJIS "Cir"; T (J67)777777........ •?2

i

Spranr.ler and United States v. Pasadena City

Boa'rd~oT" Kduc.itTon, 311 P. Cupp, bl CC.O.

Cal. 1970)'. .V. ................’..................... 37

Sv.’ann v. Board of Education, ;I02 U.S. 1 (1971)...... 48

U.S.v.National Association of Real Estate Bds.,

70 S . c t . 7"11 , 339 ’ll.S. *W5 ......................... 38

Whitus v. Georgia, 383 U.S. 5^5 (1967).............. 43

F. R. Civ. Froc. , Rule 52(a)........................ 38

Page

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 71-2508

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

TEXAS EDUCATION AGENCY, et al.,

(AUSTIN INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT)

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Texas

BRIEF FOR THE AUSTIN INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the district court erred in:

(a) Finding that the Austin Independent School

District had not discriminated against Mexican-

American students in any manner.

(b) Approving the school district's plan of

student assignment for the 1971-72 school year.

STATEMENT

1. Procedura1 History

Oil August 7, 1970, the United States filed this desegrega

tion suit in Federal Court for the Western District of Texas

against the Austin Independent School District (AISD) pursuant

to Section 407 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

2000c-6. The plaintiff alleged that AISD had traditionally

operated and continued to operate a dual school system based

on race by discriminating against both blacks and Mexican-

Americans. On the same day the Court ordered AISD to collab

orate with the Texas Education Agency (TEA) in preparing plans

for immediate conversion to a unitary nondiscriminatory school

system. The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare

(HIV/) was also ordered to assist and aid the TEA in proces

sing and reviewing all such plans developed. The parties

were ordered to attempt to reach an agreement, but if no agree

ment could be reached, they were to file their respective plans

with the Court on August 21, 1970.

On August 27, 1970, a short hearing was held and the Court

orally ordered the implementation of the interim plan offered

by the United States with only a slight modification of the

new Anderson High School zone. Besides the enlargement of

the Anderson zone, the main features of the Order were the

/ - 1 -

implementation of the provisions of Singleton v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School System, 'll9 F 2d 1211 (Fifth Clr.

1969). on September 'l, 1970, the Court entered a written

order restoring the Anderson zone to its original boundaries;

the order of August 27 was otherwise undisturbed. In its

Order the Court also directed HEW to make a comprehensive

study of AISD and prepare and submit a desegregation plan

which would completely disestablish a dual school system;

The Court further ordered the officials of AISD to consult

and fully cooperate with HEW in presenting to the Court a

desegregation plan/ The plan, or the respective plans of

the parties if they could not agree, were to be filed on

1/ See Paragraphs B, c, D, E, F, and G of Appendix A of the District Court's Order of September 4, 1970.

2/ Despite repeated orders by the District Court that the

parties should attempt to work together toward a common de

segregation plan, the evidence reveals and the court so found

that despite AlSD's repeated attempts to communicate with

nn,r a*.??rlod of SGVeral months, nothing was forthcoming from LEV. until approximately 30 days prior to trial." The

Court again repeated that "AISD was not given the benefit of

EW recommendations in drawing its plans, despite repeated

efforts to obtain such recommendations, until*approximately

30 days prior to trial." The Court concluded on this point

by stating that this "case thus appears to depart substan

tially from the usual run of school cases in that here the

uncommunicative, uncooperative and recalcitrant party has not

been the local school board, but the Department of Health,

Education, ar.d Welfare." See Memorandum Opinion and Order of

u y 9, 197x, pg. 3 , 'i . Also see testiinonv of Dr. Davidson. Transcript pg. 832, line 2 0. ' :

-2-

December 15, 1970; however, after several orders extending

the filing date of the plans, the plans were finally submitted

on May 1*1, 1971.3

A pre-trial conference was held on June 11, 1971, at

which time the Court again urged the parties to negotiate a

common plan; the case came to be heard on the merits on June

1*J, lasting for six full days. On June 28, 1971, the Court

handed down a seven page memorandum opinion and order on

only one of the two major issues in the case: the Court

found that the Defendant had not discriminated against

Mexican-Anericans. Rather than implementing a plan at that

time, the Court ordered the parties to renegotiate in light

of this finding, since it was clear that HEW had prepared its

plan under the assumption that the Court would decide in its

favor. On July 15, 1971, the parties reported back to the

3/ There is considerable question, especially in the District

Court's opinion, whether HEW ever filed a comprehensive de

segregation plan: "At this time, HEW filed with this Court

its comments on the desegregation plan formulated by the AISD.

These comments (Letter from Thomas Kendrick, Senior Program

Officer to Dr. Jack Davidson, Superintendent, AISD, dated and

filed May 1*1, 1971) [Hereinafter called HEW recommendations]

as they have been amended at trial, through the Introduction

of Plaintilf's Exhibits 23, 25, and 26, and the Report and

Submission filed with this Court on July 15, 1971, constitute

the only documentary evidence of any desegregation plan devel-

n£,e „̂'Uy "^W# , ^ trial> several further modifications to the “1J" were revualeu fur the first time throughthe oral testimony of Mr. A. T. Miller, the HEW Project Officer.

See District Court Memorandum Opinion of July 19, 1971, pg.3-*<.

/

-3-

Court and informed the Court that it had reached agreement on

the high school plan but could not agree on the junior high

school plan or the elementary school plan. Accordingly, on

July 19, 1971, the Court handed down a second Memorandum

Opinion and Order incorporating its first Opinion and imple

menting the AISD plan with minor modifications.

On August 3, 1971, notice of appeal was filed by the

United States, and in its brief the Government is assigning

error to: (1) The Court's finding that AISD had not dis

criminated against Mexican-American students in any manner;

and (2) The Court's approval of the School District's de

segregation plan for the 1971-72 school year. While it is

difficult to see, the Government's main argument seems to be

that the District Court's finding as to the Mexican-American

issue is clearly erroneous in part; moreover, the District

Court's findings as to this issue are too general, and there

fore it is impossible to tell which Mexican-Americans wore

discriminated against. Accordingly, the Government is now

seeking a remand for more specific findings; while it does

not explicitly say so, the Government implies that its plan

1

will re-drawn according to now, proper, and more specific

findings.̂

2. District Court Decision

In its brief, the Government has leveled several charges

against the District Court's Memorandum Opinion and has argued

that these deficiencies of the Opinion serve as a basis for

reversal. One of the main criticisms of the Government is

that the District Court's findings are too general, or that

the District Court "did not make specific findings of fact

but instead made general recitations mixing findings of

ultimate fact with conclusions of law." (Appellant's Brief,

PE* 38) The Government further complains that "it is often

not possible to tell what legal standards were followed in V

V See Appellant’s Brief, pgs. 90-51: "The HEW Plan, which

was prepared in response to the District Court Order of Sep

tember 4, 1970, to make a comprehensive study and prepare a

plan 'which will completely disestablish a dual school sys

tem' was based on the assumption that de jure discrimination

against both blacks and Mexican-Americans existed system-wide; consequently, it was drawn to eliminate the ethnic and racial

ldentifiabllity of every school in the system....We agree that

the scope of the remedy ordered in cases of this kind ought

to be consistent with the nature of the violation... Since it

now appears that the evidence as to de jure discrimination

against Mexican-Americans does not extend to all Mexican-

Aine-rican schools as assumed by the HEW plan, a remand to the

District Court to consider the extent of the relief warranted in this case appears proper."

-5-

1

assessing the facts or even which alleged facts were accepted

as true and which were rejected as false." (Appellant's Brief,

IG. 39.)

It is difficult indeed to understand exactly v/hat the

Government has in mind in making these statements. It is

clear that upon a reading of the lower court's opinion, it

considered the whole array of evidence, both the oral testi

mony and the lengthy number of exhibits introduced, because

the Court actually recites almost item for item all of the

evidence:

While alleging such de jure segregation, against

Mexlean-Americans, the Plaintiff failed in maintaining its burden of proof.

Texas has never required by law that Mexlcan-

American children be segregated, and the AISD,

unlike some other school systems, has never en

acted regulations to this effect. Since no dis

criminatory rule or regulation has existed,

Plaintiff has sought to demonstrate a history of

discriminatory practices against Mexican-Americans.

All that Plaintiff has succeeded in showing is

that at one time the AISD had overlapping school

zones for Pease and the West Avenue schools, and

for Metz and Zavala. During' this period, prior

to World War II, the West Avenue and Zavala

schools were referred to as "Mexican" schools,

since their enrollment was totally Mexlcan-

American, and since their programs were designed

to meet the needs of a largely migrant population

with a fluctuating attendance pattern. Even dur

ing this period, there were a number of Mexican-

Americans attending the so-called "Anglo" schools.

A pattern of de jure segregation is not estab

lished by the statement of a former student that

Mexican-Americans were encouraged to attend

Zavala rather than Metz in 1936-^1, the testi

mony of an educational expert that concentration

-6-

of Mexican-Americans in certain schools is detri

mental, the opinion of an interested, but non

expert cltisen that segregation continues, and

the implication of a recent student that the

education in one minority school is inferior.

The only other evidence on the issue of Mexican-

American segregation consists of testimony by

certain AISD administrators and former school

board members. Taken as a whole, the testimony

of the witnesses, particularly that of Dr. Wilburn,

Mr. Cunningham, and Dr. Davidson, conclusively

shows that at no time during the existence of the

AISD has there been de jure segregation against

Kexican-Anericans, and this Court so finds.

(Memorandum Opinion, June 28, 1971.)

It is difficult to understand how the Court could use

clearer language stating to the Government that it has con

sidered all the evidence proffered by both parties, and it

lias found that the Government failed to prove that AISD dis

criminated against Mexican-Americans. In addition to the

above, the Court entered the following specific findings in

Footnote 12: 1 2

Specifically, the Court makes the following find

ings of fact, based on the record as a whole:

(a) The Austin Independent School District has

never adopted, published, or promulgated any

written or unwritten rules, regulations, or

policies having as their purpose the discrimina

tion against, or segregation or isolation of

Mexican-Americans.

(b) The Austin Independent School District has

never discriminated against, or attempted to dis-

segrcgate Mexican-criminate against, Isolate >orAmericans in form whatsoever, part: :u. •iy m :

(1) site location of schools

(2) school construction

i -7-

(3) drawing of school attendance zones

(4) student assignments

(5) faculty assignments

(6) staff assignments

(7) faculty and staff employment

(8) extracurricular activities; and

(9) transportation

(c) The Zavala and West Elementary Schools were

not built for the purpose of discriminating against,

isolating or segregating students on the basis of

Kexlcan-American ethnic origin. (Memorandum Opinion,June 28, .1971.)

In addition to the above findings, the Court also made

findings in Its Memorandum Opinion of July 19, 1971, concern

ing the respective plans filed by both parties. For reasons

which will bo discussed later, the Court found the HEW plan

unacceptable and ordered the Austin plan implemented with

minor modifications. Finally, In its Memorandum Opinion of

June 28th, the lower court entered findings that "AISD has

adequately desegregated faculty and staff, transportation,

extracurricular activities, and facilities." Memorandum

Opinion, June 28, 1971.5

5/ See Defendant's Exhibits

appeal the Government is not Court.

Nos. 2'l, 79, and 81. In its

attacking this finding cf the

i

-8-

3. Facts

(a) History and Growth of AISD

There are many factors in this case which prevent an easy

or complete understanding of the facts. First, the record

Itself is very large, the transcript being over 1,200 pages,

and the list of exhibits well over 100; moreover, the exhibits

themselves complicate the case, since many of them are school

district maps with a variety of different and changing zones.

The period of time involved - over 50 years - is long and the

scene - the community of Austin, Texas - is constantly chang

ing due to the enormous growth the community has always en

joyed. The evidence itself is often quite old and stale and

therefore often ambiguous or unclear. Finally, the issues in

this desegregation case are more complex than the usual since

the Government, in addition to alleging discrimination against

blacks, is also alleging that officials of AISD have unoffi

cially discriminated against Mexican-Americans by various

actions.

The record in this case reveals that both the Austin com

munity and its school district have experienced remarkably

substantial and constant growth throughout this century.

Since 1900, the City of Austin has increased from around

22,000 in population to over 25 0,000, an average growth of

over ^0 percent per lU-year period. (Defendants Exhibit No.

59, pg. 6; Defendant's Exhibit No. 91, pg. 2.) The population

-9-

of the Austin school system has naturally reflected this grovth,

increasing from around 3,600 in 1900 to around 55,000 in 1971.

(Plaintiff's Exhibit No. 1, Defendant's Exhibit No. 59, pg. 12.)

It- Is, however, considerably more difficult to describe

from the record the concentration and distribution of both the

general population and student population throughout the years;

it is also quite difficult to describe from the record the

physical characteristics of the City - the commercial a.reas,

public facilities, traffic flow and congestion, etc. This is

especially difficult for the early years before 1950 since

the record is more sparce here. But an attempt- must be made

for it is impossible to formulate a rational school policy

without this Information. It simply will not do, as the

Government does, to merely quote figures, for that is only a

part of the picture.

By examining Defendant's Exhibits Nos. 69 and 13 and

Plaintiff's Exhibit No. 2 , and by relating these exhibits to

any of the various maps in evidence, it is clear that prior

to 1950, especially in the earlier years, the student popula

tion was in or near what is now the center of the City. For

example, Austin High School and the old Allan Junior High

School oite are now in areas that could be considered part

or very close to, the central business area of nn-.v.

The same could be said of the majority of the elementary

1

-10-

schools prior to 1950. Much of what is now the central busi

ness area, the State office complex and The University of

Texas campus, was originally residential in nature.6

Throughout all of the years involved, the City of Austin

experienced rapid population growth, However, after 19 1̂0,

no new schools were built until the early 1950's, primarily

because of World War II. (Defendant’s Exhibit No. 1 3, pg. 2 .)

But since 1950, the AISD has been engaged in almost continuous

construction, resulting in the opening of 36 new elementary

schools, nine new .junior high schools, and seven new high

schools. (Defendant’s Exhibit No. 1 3.)

Before initiating such an ambitious building program, the

Austin School Board engaged the services of a professional

planner, Jac L. Gubbels, in order to obtain advice on the

best location of its new schools. The result was a lengthy

report filed by Mr. Gubbels (Defendant's Exhibit No. 91) m

19^7 in which he stated on Page One of that report that "the

purpose of this survey is to determine the proper location

for the schools of the City of Austin, Travis County, Texas,

for the twenty-year period ending in 1966." (Defendant's

Exhibit No. 91) The report reveals many factors that were

cnt K?rans“ lpfpgs?°?S7™52? the pres-

I -11-

considered in determining site locations, but. several stand

out: first, "tne school sites were selected in areas where

the population will naturally concentrate. For this reason,

the direction of growth was analyzed with care to avoid any

artificial forcing of development."? (pg. 1) Second, "pres

ent and future major thoroughfares must be considered in pro

viding accessibility of the school site to the student popu

lation." (pg. 5) Third, "it would be a grave mistake to

locate a school site which may later prove to be in the mid

dle of a newly developed industrial center." (pg. 5) Finally

other factors includei"density of population per acre, the

number of dwelling units per acre, the distribution of white

and non-white population,^ the occupancy of dwelling units,

whether owner or tenant, the necessary acreage and location

of the acreage for the anticipated population expansion, the

7/ This is extremely Important with regard to the Mexican-

American question since the report explicitly evidences no

intent to draw and isolate Mexicp.n-Americans, which is a

major part of the Government's argument.

8/ At the time the Gubbels Report was written, 19^7, the

AlSD was required by state law to operate a dual school sys

tem based on race. Mexican-Americans were considered white

and Gubbels made no distinction between the Anglo and Mexican-

American population. Evidence that Mr. Gubbels was not mak

ing an attempt to isolate Mexican-American students can be

seen fro:.", the attendance zone he drew for the proposed East

A u stin R 1 erh h O Hn r \ 1 • 1 V ̂no 1 nHo<5 1 ̂y rrti ̂ o p v1 V*» c* f\ rr~] r \------ , .. — o “ —- ■—... — “*• - .... 0 population was present or likely to move into.

i -12

percentage of the population of school age and the distribu

tion of the school age population in the existing and anti

cipated future sections of the city." (pg. 6) In addition

to these general guidelines, more specific factors became

Involved when choosing a site for a particular school, since

there are substantial differences among the senior high,

junior high, and elementary schools,9

The wisdom of the School Board in consulting and follow

ing Mr. Gubbels advice was borne out, for in the 20 years

following 1950, Austin grew rapidly, both in population and

size. Its population almost doubled, going from about 132,500

in 11950 to 252,000 in 1970, while its area more than doubled,

going from about 38 square miles to 8l square miles.-*-0

Equally significant in terms of a sound educational policy

is the change in distribution of the school age population.

Such information is difficult to ferret from the record, but

the record does soundly support the proposition that the cen

ter of the City, starting at the Colorado River and going

north has become Increasingly commercialized, thus displacing

the residential areas. There are primarily three forces at

9/ See Defendant's Exhibit No. 91, pgs. 19, 25, 32-33. Com

pare this for similarity with Mr. Cunningham's testimony con

cerning site location. Transcript, pgs. 381-386, pgs. ^5^-467.

10/ Defendant's Exhibit No. 59, pgs. and 6.

1 -13-

v.’ork to cause such a large displacement: first, the central

business area, which is tending to displace all residential

sites from the Colorado River on the south, 13th Street on

the north, Interregional Highway on the east, and Lamar Blvd.

on the west; second, the State office building complex which

now stretches basically from 11th Street to 19th and from

Interregional Highway* on the east to Lavaca Street on the

west; third, The University of Texas campus, which extends

from 19th to approximately 29th Street and from several

blocks east of Interregional on the cast to Guadalupe on

the west. Furthermore, surrounding this rather large area

is a "proliferation of bachelor housing and young couples,

student housing___for those attending the University."11

A comparison of the student population totals for 1990

to 1970 will show the substantial decrease in student popula

tions that has been occurring in the central areas through

3 2these years:

Y l / See Transcript, pg. M7-^52.

12/ Compare Plaintiff's Exhibits Nos. 3A and 3F.

“ 19*19-50 1970-71

Mathews 1039 826

Pease 67 513 368

Palm 17961 1240

Bryker Woods 714 528

•• Baker 762 395

Lee 891 462

Ridgetop 923 644

. Rosedale 1077 892

Zavala 1333 889lif

In addition to reflecting the decline of student popula-

tion in the center of the City, the exhibits also conversely

show the increase in population away from the City's center

in almost all directions. The consequence of this is that

the schools, especially the elementary schools, have been

located over an increasingly wide area as the Austin School

Board attempts to keep up with the growing and spreading

population. In conclusion, the AISD which was rather small

and compact even as recent as 1950, is now composed of 72

13/ Pease incidentally dropped from 116’J in 1948-49 to 675 in W 9-50. (Plaintiff's Exhibit 3A)

?.h°^ e flsures represent only the white students (Anglo

S V ^ l ^ - C ^ r i c a n ) since the black student was not enumer- ated in the 1949-50 census. In 1970-71, black students were

present In these school zones as follows: Mathews, 132; Pease,

0, Palm, 32; Metz, 4; Bryker Woods, 0; Baker, 0; Leo, 20;Ridgetop, 1; Rosedale, 0; Zavala, $2.

-15-

schools spread over an area 30 miles north and south and about

2b miles east and west, with a total area of 230 square miles.15

(b) Mexican-American Student Attendance

One of tne two major issues in this case relates to alleged

discrimination against Kexican-American students, discrimina

tion not in the form of any official action but rather in the

form of student assignment and school construction. The

Mexican-American student population of AISD is presently

around 20 percent, but this was not always so. (Defendant's

Exhibit 23) In 1920-21, the Latin population was only 5.6

percent of the total white student population, but by 1930

it had almost tripled going up to 1̂ 1.87. Over the next 20

years it gradually reached around 20 percent, where it has

since remained. (Plaintiff's Exhibit No. 1)

• The evidence in this case demonstrates that Mexican-

American students have always attended schools in Austin with

Anglo students, very often in substantial numbers. Defendant's

Exhibit No. 69 reflects that there has never been a year

when Mexican-American children were not present at almost all

schools in the District and on all levels. Despite what one

would assume would be ample evidence if it were true, the

Government failed to produce one single witness who could

15/ There are now seven high, ten junior high, and 55 elemen

tary schools.

-1 6-

testify that he was refused enrollment In any school due to

his ethnic origin as a Mexican-American. In fact, the Govern

ment's own witnesses lent support to the Defendant's case.

Richard Moya, a Mexican-American, testified that in 19^1 he

transferred from Zavala, a predominantly Mexican-American

elementary school, to Metz, a predominantly Anglo elementaryc

school. Dr. Sanchez, an extremely prominent educator who

has been a full professor at The University of Texas since

191)0 and who has had substantial contact with AISD, testified

that he has never heard of a single case of discrimination

against Mcxican-Americans on the secondary level and that

he had knowledge that Mexican-American students attended

schools with Anglos. He also answered that if he had ever

hoard of any discrimination, he would have complained loud

and clear.^ (Transcript, pgs. 130-137)

16/ Other evidence, which is not very clear or well developed

because of the difficulty of working with the large number of

items involved, is the family census card, Form G-9. (See Ex

hibit No. 70, as an example.) This card, which the School Dis

triet began keeping in 193^, serves as a record of a family

during the duration in the school system. Once a family no

longer has children in the school system, its card is removed

to the inactive file. Exhibit No. 70 is a family card of

Alberto Aguirre, obviously of Mexican-American origin, and it

reflects that as the family moved, the child changed schools

from Zavala to Zilker and then from Zilker to Becker. This

would evidence that there Is nothing in the administration of

AISD that would require a Mexican-American family to live in

any part of town on account of his children or to send his

children to a particular school of their national origin.

This evidence was not introduced because it involves hundreds

of thousands of cards dating back to 193^ (Transcript, pg. 525

Tne m xou, no we v or, prGiiereu uiioso aocuments to the Govern

ment to allow an opportunity to determine if Mexican-American

families were required to live only in certain zones due to

allegedly discriminatory practices. The Government, however,

made no such use of this data. (Transcript, pgs. 528-53^)

-17-

Although the records reflect that Mexican-American students

were in all schools throughout the District at all times and.

that no Mexican-American student was ever refused admission

because of his ethnic origin, the records do reflect that

prior to World War II certain schools had an almost complete

Mexican-American enrollment: West Avenue, Comal, and Zavala.

The first two of these three schools were closed many years

age, and only Zavala remains open today. The evidence dis

closes that these schools, especially the Zavala School on

which there is the most evidence, represented a response of

the AISD to meet educationally two very serious and substantial

problems suffered by many of the Mexican-American children

prior to World War II. First, although the exact percentages

are not known, many of these children could not speak English

or had great difficulty with the language. Second, a very

large percentage of these children were from migrant farm

families who consequently started school as late as December

and left as early a3 April, and many of whom were considerably

over-age for their grade level. (TR. , pg. i\2G)

Dr. Sanel^ez himself wrote that many Spanish-speaking children

did not enter school until October, November, or even December,

and that many of them left school a month or two before the

close o: the school year, and that this problem was certainly

acute from 1920 to World War II. (Transcript, pg. 158) Mr.

Cunningham, who actually taught at Zavala when It opened In

1936, testified that at the beginning of the school year the

-18-

school population was around 250, but by the first of February

it would be close to 500; by the last six weeks of the school

year the number of students would drop down to 375 or ^00.

Dr. Lee Wilburn, who also taught at Zavala when It first

opened and served as Assistant Principal, testified that

there was a special arrangement of the curriculum because

they knew that a large percentage of the students would

arrive late in the fall semester and would be withdrawn

early in the spring because they were members of migrant

labor families. (Transcript, pg. 698) Later on Dr. Wilburn

also testified that they had these migrant children for

approximately five months out of the year. (Transcript, pg.

713)

There is also ample testimony, including some from the

Government's own witness (Transcript, pg. 1̂2), that many of

the students who attended these schools could not speak

English or had great difficulty with that language. Mr.

Cunningham testified that "help was being offered for___

children with bilingual situations," (Transcript, pg. 320)

and Dr. Wilburn testified that they had "many children (at

Zavala), particularly those that were there for the first

time, who did not speak any English when they came to school.

anu we communicated with them in Spanish." (Transcript,

70 2 )

PE'

1 -19-

The evidence further reveals that extra attention and

help were given to these children and many new and special

programs were initiated to help overcome the disadvantages

of the background. Zavala was the only elementary school,

for example, that had an industrial arts and homemaking pro

gram (Transcript, pg. 715); it was the first elementary

school to have an open shelf library, giving the students

greater access to the books. (Transcript, pg. 721) The

School also initiated a breakfast program at Zavala, the

first in Austin (Transcript, pg. 707), and it was also one

of the first schools with a hot lunch program (Transcript,

pg. 726). Another special problem was that many of the

children were much older than their grade level and conse

quently special efforts were made at Zavala to help a child

reach his correct grade level (Transcript, pg. 700).

In summary these schools and especially Zavala were

special schools built for the purpose of attempting to help

those Mexican-American children with substantial disadvan

tages; there is even testimony to the effect that the school

was opened at the request of the Mexican-American community

(Dr. Wilburn's testimony, Transcript, pg. 696). The students

responded and their interest and success in completing their

tuuciinuiis xiicieabcu Siiaipay \i.pansci*jLpi/, Pg. 7-*-5) • A read

ing of Dr. Wilburn's testimony clearly reveals that these

-20-

schools, especially Zavala, did not represent an attempt by

AISD to remove the Mexican-American students from the Anglo

population; rather it was a serious attempt to help those

Hexican-American students living in those neighborhoods who

needed and wanted the extra attention and help that was pro

vided at these schools.

(c.) East Austin

The major difficulty in this case stems out of the living

patterns of the population. East Austin, north of Seventh

Street, has traditionally been and still remains the residential

area for the blacks. There are many different reasons which

brought this about, but surely the main reason was an economic

one, since it was probably the one main area in town in which

they could afford to live. Certainly, the presence of the

majority of their schools, including both secondary schools,

surely reinforced this living pattern. South of East Seventh

Street to the Colorado River was originally an Anglo neighbor

hood with a minority of Hexican-American residents. However,

by 1920 this part of East Austin had begun to change to pre

dominantly a Hexican-American neighborhood as greater numbers

of the Hexican-Americans moved into the City. Again, economics

of the area largely caused this pattern. (Plaintiff's Exhibit 1)

The relation of this area of town to other parts of town

has certainly undergone change over the years and this has

complicated the problem. In Austin's earlier days the area

was not remote from the rest of Austin's population, but that

situation has changed considerably over the past 20 years,

which a study of the maps and exhibits will show.

-21-

The boundaries of East Austin are Interregional Highway

31; on the west, 19th Street on the north, the School District

on the east, and the Colorado River on the south. An investi

gation of the areas around East Austin will reveal the problem

of isolation of that area. First, both to the east and south

is undeveloped land, except for a small area south of the

Colorado River known as Montopolis. The western boundary of

this area Is marked by Interregional Highway, the largest and

busiest thoroughfare of the City. Going west from this high

way to Lamar Boulevard and going north from the Colorado River

to approximately Airport Boulevard is an area, discussed pre

viously, that has a declining student population due to an

ever-increasing commercialization of this area. Due north

of East Austin is a small Anglo area known as Maplewood and

adjacent to Maplewood on the east is Municipal Airport. Thus

not only is East Austin a definite and distinct region of the

City, but due to the growth of the City it has been becoming

more remote from the other major residential areas. Fortunately,

there is a major exception to this trend and this is the area

developing east of the airport, where East Austin is beginning

to come into substantial contact with a developing major Anglo

17area. '

17/ The proposed location and attendance zone of the new North

east Senior High and Junior High Schools seeks to take advantage

of this development, resulting In a naturally integrated student

body (Defendant's Exhibits Nos. 31, 32, and 37).

-22-

Another hope/ul sign for the future development of the

City is the migration of the minorities from East Austin.

In 1950-51, 93 percent of the black population lived in East

Austin, whereas in 1970, 86 percent lived there, a decline

of ! percent. The migration of Mexican-Americans from that

area is considerably higher; in 1950-5 1, 89 percent of the

Latins lived in East Austin, whereas in 1970-71, that figure

declined to 64 percent, a drop of 25 percent. (Transcript,

pg. 312-314) Another and equally encouraging aspect of this

movement is that these people are moving into all parts of

Austin and not Into another confined area. (Transcript, pg. 523)

(d) AloD Plan.: Secondary Level

In the last school year (1970-71) there were 2100 black

high school students (14* of total high school population) in

AISD, out of these 916 (432) attended Anderson, an all-black

school, and 619 (29%) attended Johnston High School.1 ̂ On

the junior high school level, there were 1570 black students

(152 of the total junior high population), 739 (462) of which

attended the all-black Keallng Junior High, and another 527

(332) at Allan and Martin.^

W x W f S e h o o l an ethnic makeup as follow No, H3)' ’ •’ nerican. 6% Anslo (Defendant's Exhibl

iffy fh7 A]1an had a student body of *137 (*t2J)blacks u j / O I /»; Lex ican-Ameri canq hr /ii5\ . r v . /uxetews,90 black- ( n o 7no 7 ’ nd ^ ^ ) Anglos; Martin has

-23-

Cf

M

School

nation this year .. ^m-olementata

jpon the ' Davids"’

devised by Dr. JacK

d n a n ’ ulU he substantia

>. these fibres

, „l level, Anderson ui^ h schoo attcndan'

,n the old Anderson

— tn > addition) Opt

nt.s Exhibit ho. 1>

20 as a resul ,

Gh school 7.ono. atte.v

, students «ho «erc

lr'h SC> ° ‘ plus about 281 st ’<J38 at Anderso ^ ^ ^

, *,«. Exhibit ho.ant ̂ -yvrentar/,,n ln which the person

hast Austi of 19-'

cf 6.85 at Travis to

&hiblt K0' 37L hiDh school lev-

°" th° 3 o l .ndthe re-son!’ri1,h School ana

J" ' ,1 U produce results

least Austin ' reenter'

21 The resulting perco

plan.

•------ D e f e n d a n t ' s E x h ib it "pO/ Compare vrr

ndent of

On the

of the

e re-zonei

. 5 (Defen-

/. ustin

,0 black

ast Austin

. .n Defen-

.tside of

..in a low

\Defendant’

r Kealing

vs out of

h school

vs in the

it's Exhibi

cuts the

Defendant’

other Junior high schools will range from a low of 5*1% at

0. Henry to 2C}.2% at Allan. All of the other junior high

schools (except Fulmore at 5.9£ black) will range from 9.2%

to 19.2% black (Defendant's Exhibit No. 37). The number of

students zoned out of East Austin will be approximately 939

(721 at Healing, plus 2*12 zoned out of Allan, minus 47 zoned

into Martin).*^

Anderson and Healing students were zoned into both con

tiguous and non-contiguous areas which will require trans

portation of these students. On the high school level 23

busses will be needed, and the total cost for the year

including operational cost will be $279,885. On the junior

high level 17 busses will be needed, and the total cost here

will be $207,895. The shift in student attendance will re

quire some adjustments in building capacity. On the high

school level the desegregation plan will require the purchase

of an additional 1*) portables plus moving 10 others, for a

cost of $17^,900. On the junior high level eight new port

ables will be needed and four transferred for a total cost

of $63,900. In conclusion the total cost of the senior high

plan will be $*159,785 and for the junior high $207,855; the

22/ These figures are derived from Defendant's Exhibits Nos. 2T and 37.

1 -25-

entire cost for the secondary plans, which provides for no

racially identifiable black school, will be $662,610.^3

(e) HEW I’lan: Secondary Level

It is difficult to determine whether the Government is

appealing the high school plan. In its report of July 15,

1971, the Government stated that it had reached an agreement

with AISd on a high school plan. However, It also stated

that such an agreement does not imply acquiescence in the

Court's findings. Moreover, the Government clearly Implies

in its brief that the Johnston High School site was chosen

to discriminate against Mexican-Americans.

HEW's proposal anticipates closing Anderson as a high

school and utilizing it as a junior high; the Anderson

students would be rezoned to surrounding high schools. The

zone^H for Johnston High School would be rezoned "to remove

its racial identiflability." (Letter of May l k , 1971, from

Thomas Kendrick to Dr. Davidson) HEW was not able to be too

specific concerning this zone and its projected ethnic

makeup, allegedly because up-to-date pupil-locator maps were

23/ All of these figures were derived from Defendant's Exhibi

Ho. 37. This Exhibit also contains the size of the new high

school zones in the "Mileage Chart for 1971 to i973."

2k/ The Government utilized a map in explaining the new zone

Tor Johnston, but failed to introduce it as an exhibit.

!

-26-

not available.̂ The cost of transportation according to

HEW would be $3^2,860. (Plaintiff's Exhibit No. 23)26

While the HEW high school plan projects serious crowding of

several of the high schools, no cost factor has been assigned

to the necessity of providing portables, which naturally re

duces the overall cost of their plan. (Plaintiff's Exhibit

No. 22)27

On the junior high school level HEW anticipates closing

the present healing Junior High and utilizing Anderson as a

junior high school. Pearce would be rezoned to include some

of the former Healing students, and Martin would be rezoned

to remove its racial identif lability. This plan a.lso contem

plates extensive crosstown bussing to remove bla.ck students

25/ If HEW was lacking- my information necessary to formulate c: plan, it was not due to any lack of cooperation on t

of A13D, since HEW always received the information it from AISD. (Transcript, Dg. 550) Part of regard was tlie failure of HEW

as stated-by Jud

July 19, 1971, pgs. 3-5.

he cart

i id requested the problem in this to consult and work with AISD,

e Jack Roberts in his Memorandum Opinion of

26/ The United States has suggested In Exhibit 23 that there

would be reimbursement from the State to the AISD for opera-

the testitri°ny Of Leon R. Graham (Transcript, pga. 103x-on reveals that there are many factors to be con-

sioered before determining the amount of reimbursement,

lhere is no assurance that the school district would be reim

bursed in an amount even close to the Government's estimate.

27/ Thu

Travis

it can

iour nigh senoois or Crockett, Lanier, McCallum, and

would have a combined total of 2725 students more than presently accommodate.

i -27-

to Anglo .schools and to bring in Anglo children from Porter,

Fulmer, Webb and Burnet. The transportation cost including

operational cost for the first year would amount to $240,320

(Plaintiff's Exhibit No. 25); again no cost factor is con

sidered for the overcrowding that would result from the HEW

plan. (Plaintiff's Exhibit No. 24)

(f) AILD Plan: Elementary Level

Desegregation of the elementary schools in a workable

fashion presented the most difficult problems for AISD. A

study of Defendant's Exhibit No. 11 v/ill revea.l part of the

reasons: fifty-four elementary schools with relatively small

zones spread across the entire district.28 The black ele

mentary schools, located in East Austin, cannot physically

be integrated by redrawing the attendance zones, because not

only are these schools remote, but ail of the adjacent schools

already had a substantial amount of integration or were school;

predominantly attended by Mexican-Americans. The approach

ol the AISD then was to attempt some means of desegregating

the black elementary schools, while at the same time pro

viding sound educational programs for Mexican—Americans:

Now with this kind of dilemma, which I guess

is faced by urban school systems all over the country, we began to look at some means of

doing this on an educational basis. And in

£6/ The closing of St. John's Elementary School, the onlv

r ̂ !̂-LclCK bCiluo-L outsnue oi mast Austin, reduces the nu^b®r of elementary schools from 55 in 1970-71 to 54 for 1971-72.

i

-28-

pursul

school

school

Americ

began

all bl

were p

some 1

tion a

all whlookin

emerge

provid

blacks

chilor

ng the questions of how many black

we had, how many Mexican-American

v;hlch were predominantly Hexlcan-

ms ar-» 11r rr. ̂ny Anglo schools, it

to be apparent that we had about 7

ack schools, we had 7 schools which

redominantly Mexican-American, we had

6 schools that had a level of segrega-

nd some 27 schools that were basically

ite at the elementary level. So, in

g at that, the consideration began to

, would there be a possible way to

e some good educational experience for

, for Mexican-Americans and for Anglo

en in a way that could be planned by

educators and could at the same time meet

the requirements of lav?. I hope you will

notice that our primary consideration in this

was some way to make this experience educa

tionally sound. As a matter of fact, in

studying it, we tried to say let's take what

in many communities is a tough kind of problem

and see if there is any possibility of turning

it into an educational advantage. It was on that

basis there that we began to look at approaching

the things from an educational stand point. (Testimony of Dr. Davidson, Transcript pgs.775-

776)

Dr. Davidson's plan, a completely new approach, achieves

substantial integration for all of Austin's school children.

in a manner consistent not only with traditionally sound

educational goals but also with new developing techniques in

education, especially team teaching:

One of the developing techniques in education

today is the utilization of what is termed

(team) J teaching, and as we were working on

some pr*0£\2?cinis !'or* tr.02.m &ncl ^ ^

?9/ On pg. 777 , line 18, the court reporter apparently omitted the word "team" in front of "teaching".

1 -29-

teaching and continuous progress of our

children at our elementary level, the idea

began to emerge that if it is possible to

team teachers together, is it not also

possible to team schools together for multi

cultural activities; and so we looked at the

possibility of taking these seven basically

all black schools, the 7 schools that were

predominantly Mexican-American and the 27 or

so schools that were predominantly white and

establishing some teams of companion schools. (Transcript, pgs. 777-778)

In addition, this plan attempts to stress the different

cultures— black, Mexican-American, and Anglo— of the Austin

community and how they can be maintained and how the different

cultures live together in our society:

it became pretty important to look at ways

that the culture of the blacks, the culture

of the Kexican-Amerlcans, and the culture of

the Anglos could be maintained and stressed

at the same time how these different cultures

live together in our society. (Transcript, pgs. 777-778)

The prominent features then of the Davidson plan are:

(1) the retention of the basic neighborhood school concept

substantially modified; (2) utilisation of new and developing

techniques of education, i.e. team teaching, and application

of this concept so as to team schools; (3) emphasis on the

cultural variety of our three ethnic groups in such a way

that wholesome attitudes are developed and all the students

come to respect anu appreciate the contributions of each

ethnic group.

-30-

/

The plan or educational Integration envisions the estab

lishment or sir teams of "companion schools." Those are com-

postd.or 0ne Virtually 211 black school, one school predominantly

or Mexican-American students, and four schools of predominantly

Anglo enrollment. (See Defendant's Exhibit No. 78.) Within

each team there is established a central coordinating commit

tee consisting of the six principals, six teachers (one from

or), one to three Instructional coordinators from the

central administrations, resource personnel for special areas

of con.erned parents, and staff specialists. This multi-

cultuial commuted, since It consists of representatives from

minority and majority race students, will be called upon regu

larly to assess and review these planned educational programs.

AS a means of providing authentic evaluation from minority

croups, one such committee will be established with a special

F rvlsor, group consisting of a predominantly number of

minority representatives. This w in assure continuing evalua

tion concerning activities for minority students.

The program activities have three basic components:

(1) Planned sequential visits between the

schools of different ethnic backgrounds by

grace levels and by groups of students;

(P) Programmed visitations to establish learn-— ° resource centers with the Cit”

centers will be established in the’areaiTof

-31-

social sciences, fine arts sciences, and

avocational interests. Students will be

transported for these education activities.

(3) Multi-cultural field study trips within

the teams of companion schools.

Specific program activities are planned for these multi

cultural inter-site visitations. The coordinating planning

advisory council for that team of schools would preplan the

educational activities to be pursued by the specific students.

This has been accomplished by one team.for illustration to

the District Court and is continuing at the present time.

Iii the inter-site visitations, a groat number of educational

possibilities exist. One example can be cited in the study

of Texas history. Fourth grade students from each of these •

schools would study the developing history of Texas and the

contributions made by the different ethnic groups in that

history. Stressed particularly would be the contributions

of Mexican-Americans and blacks, as well as Anglo citizens.

The culture of each of the groups would be studied. In the

inter-site visitations of these fourth grade students, this

study would culminate with group discussions on an inter

ethnic basis, musical programs related to their studies, art

forms prepared by the students depicting cultural development

dramatic skits presented in both Spanish and English with

emphasis on the important contributions of each culture and

how these cultures have helped produce the multi-cultural

i

-32-

ethnic society in which we live today. Another possibility

is the study of neighborhood and environmental conditions

in which the various groups live. This provides an oppor

tunity for understanding and appreciation of both the liv

ing conditions and the life styles of other people. Specific

programs in literature, language, communications, history,

sociology, music, art, drama, and practical arts are planned

for these inter-site visitations.

The four learning resource centers, three of which were

to be established in Anderson, Kealing, and Baker, provide

opportunities for larger groups of students to assemble

together than is possible with inter-site visitations. The

science resource center could be established at Baker, the

center for avocational interest at Anderson, and the centers

for fine arts and social sciences of Kealing. In these visits

to the learning centers, students would have planned activities

with large groups of students. These planned activities would

include small group seminars, as well as the large groups.

These centers will be equipped with materials and equipment,

exhibits, displays, and demonstrations, which will emphasize

both the academic areas' of interest and the multi-cultural

involvement. These centers provide tremendous opportunities

for educational enrichment on a multi-cultural basis.

/ -33-

An individual child within a particular classroom in

a specific school could be expected to visit these learning

resource centers approximately 23 times per year. This is

computed on the basis of using the centers approximately

150 out of the 180 school days per year. This would be

equivalent to approximately 13% of the instructional year

to be spent in these learning resource centers for special,

planned educational activities. If inter-school educationally

integrated activities were provided for 150 days of the school

year, each child in each class of each school in the teams of

companion schools could participate approximately 25 times

during the instructional year. This would amount to approxx-

matcly 14? of the instructional year's time. The total of

the inter-school visitations and the sessions at the learning

resource centers would be approximately 2(% of tho year's

scheduled time. When one adds the multi-cultural field study

trips to such things as regional science centers, children's

theatres, symphony orchestra concerts, ot. cct., it can bo

seen that approximately one-third of the student's total

time in school during the year would be spent in these planned

multi-cultural activities.

-34-

1

Special care was taken to make sure that the children

from the various schools in each of the six clusters

would be learning together in an integrated atmosphere;

moreover, measures were taken so that the same children

would be together during the inter-site visits, classes

at the learning resource center, and on field trips. In

structional groups of 28 to 32 students will be composed

of four multi-ethnic student teams consisting of 6, 7 , or

8 students each, depending on the size of the companion

school groups. The students in each instructional group

will normally be in the same grade level and will be balanced

ethnically. This will enable students to interact with the

same group of individuals over a period of a school year,

thus providing an opportunity for greater in-depth learning

and understanding.

As was mentioned earlier, the Davidson plan will still

utilize the neighborhood school concept on the elementary

level. Students will report to their regular schools in the

morning and then be transported as a class under the super

vision of their teachers to one of their planned activities.

At the end of the day, they will be returned to their home

school again as a class under the supervision of their tea

chers. No new busses will be required for transportation

1 -35-

since the same busses used for secondary schools will be

used again for the elementary school plan; operational cost

will amount to about $100,000. (Transcript, pg. 831)3°

(g) HEW Plan: Elementary Level

The HEW Plan for the elementary schools employs a cluster

concept which would involve permanent assignments of students

to schools which on the average would be approximately ten

miles from their home (Defendant's Exhibit 82, Attachment A),

and would require the crosstown bussing of 8,900 students

(Plaintiff's Exhibit 26). The plan, obviously devised with

out any educational planning, is undeveloped and vague; it

fails to explain for example how children are to be grouped

in those schools which have been paired with other schools

(some contiguous and some non-contiguous). And two of their

proposed clusters achieve only minimal Integration; Cluster

ho. 5 has only 1% black and Cluster No. 6 has 2% (Defendant's

Exhibit 82, pg. 5 ). The bussing of the students, of course,

would be unsupervised and not educationally oriented as would

be the case in the Davidson Plan. The number of busses re

quired would, according to HEW's figures, be around 65 and

the estimated cost before any reimbursement would be $717,900.31

a« fullfr and more complete discussion of the Davidson { c.n for tne elementary schools, see Transcript ngs 772-800 and Defendant's Exhibit No. 80 ’ PS t ( i

|1/ All of the cost figures estimated by HEW for its own "Ians

serlous doubt and the lower court itself found

DleLnt oTCStl?ated the number or busses required to im- oni n f f n f y sch001 Plan- According to AI3D, who m v f°nsiderod ,I10r° rellable in its cost estimates, thee -̂ementary proposal would cost $1 ,708,000, and the entire

' Plan ^oula cost $2,910,579. (Defendant's Exhibit No. 82)

-36-

DISCUSSION

I. NO ERROR ON MEXICAN-AMERICAN ISSUE

In its allegations of AISD discrimination against

HexJcan-Amcrican students, the Government admits that no

such discrimination has ever been officially practiced.

The Government v;as forced to admit this because no state

law has ever required segregation of Mexican-American students,

nor had the Austin School Board ever adopted any rule, regula

tion, or policy statement to this effect. And Texas courts

have for years held that those school districts that did prac

tice segregation of Mexican-Amcricans were in violation of the

constitution. Independent School District v. Salvatlcrra,

33 S.W .2d 790 (Tex.Civ.App. 1930), cert. den. 28h U.S. 580

(1931) ; Delgado v. Bastrop Independent School Dlstrlct , C.A.

No. 388 (W.D. Tex. June 15, 19^8)(unreported); Hernandez v,

Driscoll Consolidated Independent School District, 2 Race Rel.

L.R. 329 (S.D. Tex. 1957).

The Government alleged though that AISD practiced dis

crimination against Mexican-American students through its

"actions" and decisions (Transcript, pg. 17) and thus is guilty

of de jure segregation. Spongier and United States v. Pasadena

City Board of Education, 311 F.Supp. 6l (C.D. Calif., 1970).

-37-

1

The most recent and major case on do jure segregation of

this type is Davis v. School District, City of Pontiac,

309 F. Supp. 73*1, 741-42 (E.D. Mich., 1970), aff'd 443 F 2d

973 (6th Cir. 1971). It was the Davis case which the District

Court followed in determining whether some form of de jure

segregation had been practiced against Mexican-Americans:

Where a Board of Education has contributed

and played a major role in the development

and growth of a segregated situation, the

Board is guilty of de ju.rc. segregation.

Davi s , supra, p . 74 2 .

Following the broad principle and applying it to all the

evidence presented at trial, the court found that the Govern

ment failed to sustain its burden of proving AISD discrimina

tion against Mexican-American students. The finding of the

lower court with respect to this issue is similar to any

other finding of fact and should not be set aside unless

clearly erroneous. Rule 92, F.R.Civ.Proc. An appellate

court cannot set aside findings as clearly erroneous merely

because it might give the facts another construction, resolve

the ambiguities differently, or find a more sinister cast to

actions which the district court apparently deemed innocent.

U.S. v. National Association of Real Estate Dds. , App. D.C.

1950, 70 S.Ct. 711. 339 U.S. 485. $4 L.Ed. 1007. It is clear

that the findings of fact entered by the district court

1 -38-

pursuant to the legal principles onnunclated In Davis, supra

are not clearly erroneous, but to the contrary, they are

supported by substantial evidence.

In actuality, the Government has leveled against AISD

two charges of discriminatory actions, unrelated in time and

somewhat in manner. The first charge is aimed at certain

actions of the School Board made from around the 1920's to

the en.a of World War II. This, of course, involves three

elementary schools, West Avenue, Comal, and Zavala, the first

two having closed many years ago, whose student body was pre

dominantly, if not entirely, Mexlcan-American. The Government's

charge in essence is that these schools, together with their

open attendance policy, evidenced an intent upon the part of

the Austin School Board to segregate and isolate Mexlcan-

American students from the majority Anglo population. The

Government has also tried to bolster its case by introducing

evidence from school board minutes between 25 and 50 years old

of isolated remarks in referring to the "Mexican" school, com

plaints from a committee of parents from Winn over their school

having to take all the Mexlcan-American students from the re

cently closed Bickler, certain complaints from Mexlcan-American

parents and the Mexican consul concerning the lack of any Anglo

-39-

The second charge revolves around thestudents at Zavala,

enumerations of "Latin Americans" in the census beginning

around 19;,8, the construction policy of AISD beginning

around 1953, and its method of drawing attendance zones.

The record as a whole reveals not only did the Government

fail to sustain its burden of proof, but also that it put

on a very weak case. If their allegations concerning dis

crimination were true, especially in the years before Zavala

was given its own definite geographic zone in 1953, it would

appear that there would be ample ora], testimony to this effect

Yet the Government failed to introduce even one witness who

could testify that he was refused admission to a nearby

grade school and required to go to a "Mexican" school. Surely

this glaring omission of evidence must have weighed heavily

in the lower court's decision. Moreover, the Government's

only witnesses on this issue supported AISD's position.

Richard Moya, who had attended Zavala for his first three

years, transferred to Metz, a predominantly Anglo grade school

in 19^1 when his family moved. Dr. Sanchez testified he had

never heard of a single case of discrimination against Mexican

American students In the AISD.^

3?/ There should be little doubt t

would have taken action if such a

participated in both the Driscoll

supra. (Transcript, pgs. 92, 116)

hat this prominent educator

situation had arisen; he

case, supra, and Delgado,

Also the "documentary" evidence introduced by the Government,

i.e., the school board minutes, hardly deserve to be labeled

as exhibits. They are extremely old and stale and now prac

tically impossible to clarify. And these minutes badly need

such clarification. For example, the committee of parents

from ttinn, a favorite of the Governments, could easily have

been complaining over the possible overcrowding at their

school resulting from the closing of Bickler. It Is unfair

to infer, as the Government does, that these people wanted

to discriminate against Mexican-Americans. This incident, of

course, will probably never be explained since it occurred

around 23 years ago. The various references to the "Mexican

school" and the complaints of various Mexican-American parents

and a Mexican consul, all occurring from 25 to 50 years ago

are likewise extremely weak documentations of discrimination.

As to the closing of Bickler Elementary School, Mr. Cunningham

testified that that was necessary due to the residential popu

lation being pushed out by commercialization in the vicinity.

(Transcript, pg. 323) Finally, the zone line for Zavala,

over which the Government complains, was originally drawn

next to the school; however, since Zavala and Metz were only

three blocks away, it is rather obvious th i- V-

d is l / l i c ; u u u n u u i . j

-41-

lir .c would necessarily run next to one of the schools. 33

On the other side of this question, the AISD presented

sone very substantial evidence. Defendant's Exhibit No. 69

reveals that in every year in question, Mexican-American

students attended all schools in Austin and on all levels,

with one or two occasional exceptions. Furthermore, the

teftimony of Hr. Cunningham and Dr. Lee Wilburn clearly show

thft the so-called "Mexican" schools were not built for the

purpose of segregating Mexican-American students, but rather

were designed to provide those students who needed them an

opportunity to take advantage of the special programs offered.

There is no question that a large number of Mexican children

could attend school an average of only 9 or 6 months because

they were members of migrant families; it is also clear that

many of the Mexican-American children could speak no English,

or very little; finally, many of these students were over-age

for their grade level. The programs and curriculum at Zavala

were designed to compensate for these deficiencies and offer

the children extra help in their education. The programs were

successful (Transcript, pg. 720), but the children were still

free to attend other schools (Transcript, pg. 723).

• ~ ̂ 4- U ,33/ This ~cno ̂ ^^

changing capacities of the schools.(Transcript,j uui,̂ u i/<ii uÛ ii uhe years due to

Pg. 322)

2-

1

The second charge of discrimination against Mexican-

Amcricans made by the Government against AISD concerns the

following: (1) the enumeration of Latin Americans in the

census beginning around 194 8; (2) the building program after

1993. The Government has attributed some sinister motives

to Mr. Cunningham's tabulating the number of Mexican-Americar.

students beginning in 194 8. The Government has argued that

the use of this Information in connection with the building

program of AISL aided AISD in segregating Mexican-American

students.

As legal support that this type of activity— i.e. enu

merating Latin Americans— is unconstitutional discrimination*

the Government has cited Avery v, Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1553;

and V.1 hit us_v. Georgia* 385 U.S. 595 (1987). The Government's

reliance on these cases is clearly misplaced* for those cases

involve the use of certain information by the State in such a

manner that it raised very strong prime facie case of race

discrimination against blacks in jury selection.

To begin* Mr. Cunningham was not instructed by the school

board to initiate a separate census for Latin-Americans.

(Transcript, pg. 453) Ho began this on his own* as a student

under Dr. Sanches. for a reasearch project. The cross-exam!na

tion of Dr. Sanchez reveals that many of his graduate students

1 -43-

wrote their theses on the education of Mexican-American

children in Austin. After his research project, Mr. Cunning

ham continued on his own to keep this information:

The exhibit indicates the division of three

groups there, your Anglo-American, Latin

American and Negro, and it was kept. I kept

it. I started it as a research project when

I was taking the course under Dr. Sanchez,

and I have kept it ever since then, as long

as we kept the census. It is very interesting

and revealing, and we have had the opportunity

to present the statistics to the administration

and the Curriculum Department for their use in

beefing up the school in the Curriculum Depart

ment. (Transcript, pgs. 327-328)

In its Memorandum Opinion of June 28, 1971, the district

court found that "the evidence adduced at trial, especially

the testimony of Mr. Cunningham, shows that the AISD has

followed a policy of 'racial neutrality' in locating facilitie

The AISD considers neighborhood need, not race, in choosing

school sites". (Pg. 4) There is more than ample evidence in

the record to support the court's finding here.

The Government has based its’ case on this issue of school

construction on four events: the opening of 0. Henry Junior

high School in 199^ and the attendant moving of the west

boundary of Allan from the Colorado River to Lamar Boulevard

(Plaintiff's Exhibit Nos. 10A and 10B); the location of the

new Allan Junior High School in East Austin, after the old

Allan burned In 19‘37 (Plaintiff's Exhibit Nos. 10B and IOC);

the location of Johnston High School in East Austin in I960;

and the location of Martin Junior High School in 1967 after

AISD v/as forced to vacate University Junior High School by

the University of Texas (See Exhibit No. 67).

At no point in the trial has the Government ever suggested

that any of the.- schools were unnecessary, nor is there any

evidence to suggest otherwise. As mentioned earlier, due to

a combination of tremendous growth and the failure to construct

schools during World War II and five years thereafter, there

was a tremendous need for new schools. Furthermore, if the

schools were to be accessible and serve the population, they

would obviously have to be built away from the central area.

The AISD did nothing more than follow the advice of a profes

sional planner and, accordingly, located the schools where

they were logically needed. It is significant that the

Government has also never suggested that the locations were

illogical or poorly planned. Nor have they even seriously

suggested what would be a more logical, convenient, or even

available location. Finally, the Government has not alleged

that the attendance zones for these schools were gerrymandered

or inconsistent with AISD'3 own sound policies in this regard,

except for a small and temporary optional area. (Defendant's

Exhibit No. 8, Optional Zone No. 6)

1 -'15-

As the Gubbe.ls report and Mr. Cunningham's testimony

reveal, the selection of a school site, especially a large

one like a junior or senior high site, involves many con

siderations and factors which seriously narrow the possi

bilities. All of the site selections were consistent with

a sound educational policy, and there is nothing to suggest

that these sites were chosen with a purpose to discriminate.

The Government has tried to suggest that Martin could have

been located at Hancock site, between 3&th and l̂lst Streets

and Peck, and Red River Streets (located at P and 22 on the

map). However, as Mr. Cunningham testified and as the exhibits

show, this site which 'was considered was rejected because of

poor accessibility and because the area immediately south was

diminishing in population. (Transcript, pg. 380) As to

Johnston High School, no alternative site or attendance zone

v llwas suggested by the Government.-^

3Ji/ In its brief, the Government wrote that the Superintendent

recommended a more centrally located site (Plaintiff's Exhibit

No. 11-A). This is another example of the Government's use

of "documentary" evidence and the use of it to raise unjustified

inferences. That particular paragraph reads "Mr. Carruth also

pointed out a site which might be available from the city of

Austin nearer the center of the school population. This site

is near the rive1’ and jn the southwest part of the district".

This is so weak it is evident why the Government failed to

pursue it.

i - i \ G -

There are also several actions which clearly show no

discriminatory intent on the part of ATSD. For example,

A1SD maintained University Junior High for many years while

it was thoroughly integrated, and the only reason it was

abandoned was due to the termination of the agreement with

the University of Texas by the University over the protest

of AISD. (TR. p. 478; Df. Ex. 67 ) Also, the zone that was

drawn for University Junior High in 1957 could have easily

been redrawn sc as to transfer the bottom area of that zone

to Allan and thus lower the percentage of minorities at

University. (Plaintiff's Exhibit No. IOC).

There is no disagreement with the cases cited by the

Government to the effect that Mexican-Americans are an

O f*ethnic g r o u p . N o r is there any -disagreement with Davis,

supra, which the lower court followed. However, all of

35/ Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S.. 4 75 (1954); Alvarado v. El

Paso Independent School District, No. 71-1555"'( 5th Cir. .

decided June T 6, 19717; Nendoz v. Westminister School District, 64 F.Supp. 544 (S.D. Calif. 1 9 ^ T ] aff'd, lbl F2d~

W C9th Cir. 1947); Gonzales v. Sheely, 96 F.Su d d. 1004

(D. Ariz. 1951); Romero v. Weakley, 22d F2d 399 (9th Cir.

1955); Cisneros and United "States v. Corpus Christ! Inde

pendent S c h o o l ' D i s t r i c t F.Supp. 599 Ts7b. Tex. 1970)(No. 71-2307 on appeal).

-47-

1

theso cases hold that a complaining party must show some