Lee v. O'Kelly Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lee v. O'Kelly Court Opinion, 1971. 53545516-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e6646d0d-ec75-4c4f-95c0-a2ecb9a391d5/lee-v-okelly-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

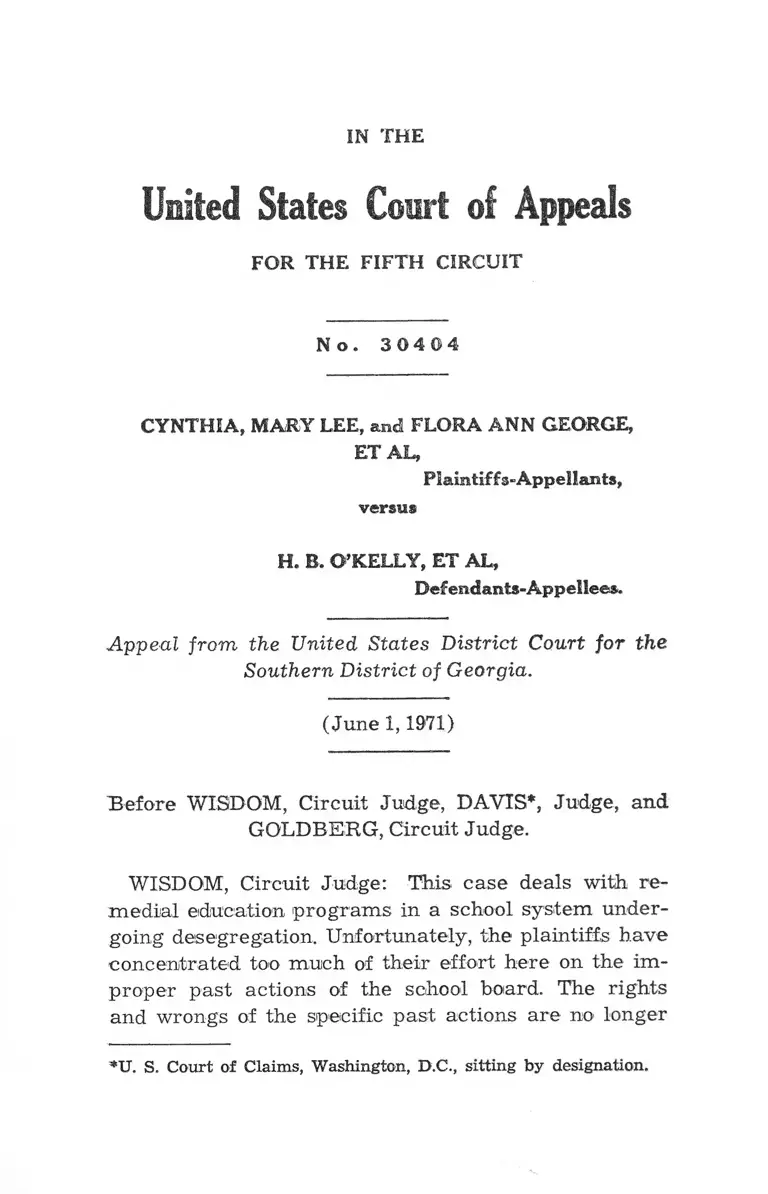

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 3 0 4 0 4

CYNTHIA, MARY LEE, and FLORA ANN GEORGE,

ETAL,

Plain tiffa-Appellants,

versus

H. B. O’KELLY, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees.

A ppeal from the United S ta tes D istrict Court for the

Southern D istrict of Georgia.

(June 1,1971)

B efore WISDOM, C ircuit Judge, DAVIS*, Judge, and

GOLDBERG, C ircuit Judge.

WISDOM, C ircuit Judge: This case deals w ith re

m ed ia l education p ro g ram s in a school system under

going desegregation. U nfortunately, th e plaintiffs have

concen tra ted too m uch of their effort here on the im

proper p a st actions of the school board. The righ ts

and wrongs of the specific p a s t actions a re no longer

*U. S. Court of Claims, Washington, D.C., sitting by designation.

2 GEORGE, ET AL. v. O’KELLY, ET AL.

the sub ject of dispute. There is, however, still a live

issue. T hat is the p resen t and fu ture operation of th e

rem ed ial program . We rem and the case to the d istric t

court for fu rth e r consideration.

The public school system of Oandler County, Georgia,

is 58 percen t white and 42 percen t black. There are

th ree schools in the system . P rio r to the 1970-71 school

y e a r one of the schools was a. tw elve-year all-black

school; one was an overw helm ingly white e lem en tary

school and one ,w asr ,ap overw helm ingly white high

school. D uring the w inter of 1969-70, the school system

was o rdered to d ism antle its seg rega ted p rog ram and

to c luster its th ree schools so; th a t all children in each

grade would be in the gam e school. H aving agreed to

com ply w ith the court order, the school d istric t be

cam e eligible for federa l funds th a t had previously

been cut off for noncom pliance .with the desegregated

guidelines.

i

U nder Title 1 of the E lem en ta ry and Secondary E du

cation Act of 1965, 20 XJ.S.C. §241ia et seq., the school

system was eligible.for g ran ts am ounting to $120,000

for support of p rog ram s to m eet “the special education

al needs of educationally deprived children.” In F eb ru

ary 1970 the county school board decided not to apply

for these funds. At the tim e of the decision the sta tu te

provided that, if the funds w ere not used by the1 county

for a sum m er program , they would be red istribu ted to

other counties in Georgia. The board ’s reasons for de

ciding to pass up the opportunity to use these funds

a re uncertain. The appellants alleged th a t it was sim

ply because, under the board’s incorrec t understanding

GEORGE, ET AL. v. O’KELLY, ET AL. 3

of the federa l guidelines, only black children would

benefit from a Title 1-funded sum m er program .

P a re n ts of b lack children sued in federa l d is tric t

court to requ ire the board to apply for and m ake use

of the funds to conduct a su m m er program . They con

tended th a t the board should be requ ired to do th is for

two reasons: 1) the board ’s m otive in refusing to apply,

for the funds w as unconstitutional; 2) as p a r t of its af

firm ative duty to d ism antle the dual school system , the

board had a duty to m ake use of the funds to provide

rem ed ia l education to p rep are black students for th e ir

f irs t y e a r in an in teg ra ted school system . The plaintiffs

nam ed as defendants the county school superintendent,

the m em bers- of the county school board, and the s ta te

superin tenden t of schools.

The d istric t court for the N orthern D istric t of Georgia,

A tlan ta Division, w here the plaintiffs filed the action,,

tran sfe rred the case to the d is tric t court for the South

e rn D istric t of. Georgia. T hat court held a hearing

June 10, 1970. By the tim e of the hearing, an im portan t

change had occurred in the law. Money not used by

the county for a sum m er p rog ram would no longer

im m ediately be red istribu ted to o ther counties. This

m oney would now be availab le for the school board ’s

use during the regu lar 1970-71 school year.

At the hearing the school superin tenden t explained

the decision n o t to have a sum m er p rog ram with th ree

reasons. F irst, still operating under ia m isim pression

about restric tions on the composition of the sum m er

p rogram , the superin tendent said the board had de

4 GEORGE, ET AL. v. O’KELLY, ET AL.

cided th a t it would be b e tte r to spend the m oney during

th e school y e a r when it could benefit both b lack and

white educationally deprived children th an during th e

su m m er w hen it could be used only fo r b lack children.

Second, he siaid th a t renovations req u ired by th e change

of g rade s tru c tu re in th e school buildings would p re

ven t the use of the buildings for a sum m er program .

Third, he said th a t the person who otherw ise would

run such a p ro g ram would not be availab le during the

sum m er.

The d is tric t court m ade no findings on th e original

m otivation of the board in deciding not to have the sum

m e r progrtam. R ath er he view ed the controversy from

the fac ts availab le a t the time- of the hearing , including

th e change th a t allowed the board to c a rry the funds

over to the reg u la r school year. The judge sta ted th a t

th e problem in the case- w as not w hether to have a r e

m ed ia l p rog ram but only w hen to have it. This, he

held, was an adm in istr ative r a th er th an a constitutional

question. And he found th a t the board ’s adm in istra tive

decision w as not unreasonable, a rb itra ry , or an abuse

of -discretion.

The sum m er of 1970 is beyond our pow er to recall.

Any possible unconstitu tional m otivation for the de

cision not to have a sum m er p ro g ram during 1970’ is

irre lev an t now in determ ining in junctive relief with

resp ec t to a rem ed ial p ro g ram in th e C andler County

schools. According to the- briefs of the- appellees, the

school system has used Title I funds to run a 1970-71

reg u la r y e a r rem ed ia l p rog ram -and p lans to ru n pro

g ram s during the sum m er of 1971 and during the 1971-

GEORGE, ET AL. v. O’KELLY, ET AL. 5

72 school year. W ithin the fac tu al context now before

us the orig inal dispute is moot.

H ow ever we do not dism iss this case. D uring the h e a r

ing below and in argum en t before th is Court, the plain-

tiffs-appellantsi suggested th a t b lack children w ere in

g re a te r need of rem ed ial education because of a long

h istory of inferior education and they ra ised questions

as to w hether the extensive testing conducted by the

school board w ith Title I funds will be used to divide

studen ts into achievem ent track s, which m igh t resu lt

in the reestab lishm ent of segregation w ithin the school.

Cf. Hobson v. Hansen, D.D.C. 1967, 269 F. Supp. 401;

Note, “E quality of Educational Opportunity: A re ‘Com

pensato ry P ro g ram s’ Constitutionally R equired?” 42

So. Calif. L. Rev. 146, 157 (1969). Also in the hearing

below, the plain tiffs’ expert w itness suggested th a t inso

fa r as the school board was spreading the Title I funds

throughout the system ra th e r th an concen trating them

on those students who a re re la tive ly m ore educationally

deprived, the board w as stray ing from the purpose of

Title I.

On rem and, the d istric t court should hold a hearin g

on the operation and planning of the C andler County’s

Title I p rogram . The court should consider w hether

achievem ent grouping or rem ed ial p rog ram s during

the reg u la r school y e a r resu lt in rac ia l segregation

w ithin the school. If so, the court should inquire w hether

th is resu lts from the county’s provision of re la tively

inferior education to the black com m unity in the past.

If this should be the case the court should consider

w ays to achieve the rem edial p rog ram without m ain-

6 GEORGE, ET AL. v. O’KELLY, ET AL.

tam ing seg rega ted classroom s. F o r instance, one w ay

to do this wo-uld be to concen trate rem ed ia l p ro g ram s

during the sum m er. Also, if the court finds th a t b lack

children have a low er educational achievem ent level

because of inferior education to the b lack com m unity in

the past, it should consider w hether the board ’s alloca

tion of Title I funds com ports with, its duty to overcom e

any special educational deprivation of b lack children

due to p a s t discrim ination. See Plaquem ines Parish

School Board v. United States, 5 Cir. 1969, 415 F.2d 817,

831; United S ta tes v. Jef ferson County Board of E duca

tion, 5 Cir. 1966, 372 F.2d 836, . , 893, aff’d en banc,.

1967, 380 F.2d 385, 394. The purpose of Title I of the E le

m en ta ry and Secondary Education Act of 1965 is con

g ruen t w ith the affirm ative duty of the board to! take

appropria te action to overcom e any effects of p a s t r a

cial discrim ination. . ,

The judgm ent of the d is tric t court is VACATED and

th is case is REM ANDED to the d istric t court for p ro

ceedings consistent w ith this opinion. The costs, of ap

peal shall be divided equally betw een the parties.

Adm. Office, U.S. Courts—Scofields’ Quality Printers, Inc., N. O., La..