Motion to Dismiss or in the Alternative, to Affirm

Public Court Documents

August 26, 1998

49 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Motion to Dismiss or in the Alternative, to Affirm, 1998. f1d2b22c-d90e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e6881c76-95bd-4d3a-ad4b-7f6e06ff56c0/motion-to-dismiss-or-in-the-alternative-to-affirm. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

i

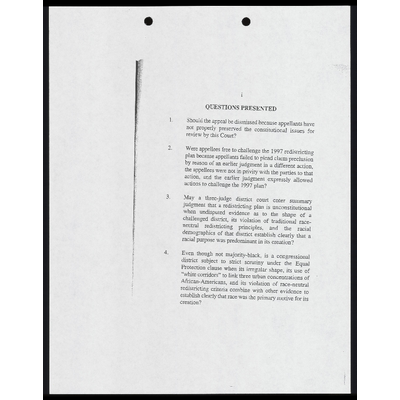

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Should the appeal be dismissed because appellants have

not properly preserved the constitutional 1ssues for

review by this Court?

Were appellees free to challenge the 1997 redistricting

plan because appellants failed to plead claim preclusion

by reason of an earlier judgment in a different action,

the appellees were not in privity with the parties to that

action, and the earlier judgment expressly allowed

actions to challenge the 1997 plan?

May a three-judge district court enter summary

judgment that a redistricting plan is unconstitutional

when undisputed evidence as to the shape of a

challenged district, its violation of traditional race-

neutral redistricting principles, and the racial

demographics of that district establish clearly that a

racial purpose was predominant in its creation?

Even though not majority-black, is a congressional

district subject to strict scrutiny under the Equal

Protection clause when its irregular shape, its use of

“white corridors” to link three urban concentrations of

African-Americans, and its violation of race-neutral

redistricting criteria combine with other evidence to

establish clearly that race was the primary motive for its

creation?

i1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES . Li... ous vis 111

COUNTERSTATEMENTOFTHECASE ............. 2

A. The 1092 Redistricting Plan... .... cao. 2

B. The 1997 Redistricting Plan... ........... 5

Ee] Si The 1998 Redistricting Plan... .......... 7

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ......... x, 8

ABGLIMENT or iad smi oe 0 10

I THE APPEAL SHOULD BE DISMISSED

ASNONJUSTICIABLE ........ 0. ...i0 0. 10

II. APPELLEES WERE NOT PRECLUDED

FROM CHALLENGING THE 1997

REDISTRICTING PLAN co... uu. cabs 14

A. Appellants’ assertion of claim

preclusion is untimely and should be

distegarded Es LIE 14

» B. The Shaw plaintiffs were not privies or

“virtual representatives’ of appellees .... 15

Cc. The district court conducting the

remedial phase of Shaw v. Hunt

specifically provided in its order and

opinion that its decision only applied

to the plaintiffs and claim identified by

the Supreme Court before remand . ...... 18

THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY

GRANTED SUMMARY JUDGMENT ON

THE UNCONSTITUTIONALITY OF

DISTRICHER1Y. rn si eins viii snd 19

111

A. The shape and demographics of

District 12 and its disregard of

traditional redistricting principles

prove the predominantly racial motive ... 21

B. Direct evidence confirms the

predominantly racial motive in

drawine District 12... 2 ii bo 3

IV. DISTRICT 12 IS SUBJECT TO STRICT

SCRUTINY UNDER THE EQUAL

PROTECTIONCLAUSE:. .. iv 29

CONCLUSION =. 2. 0 i rane =n gh 30

1v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES:

Aleyska Pipeline Serv. Co. v. U.S. E.P.A., 856 F.2d 309

DC. Cit 1988) nh ads Si hh 20

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242 (1986) ... 20

@®.... v. United Farm-Workers Union, 442 U.S. 289

(979) oth i Ee i EE 10

Benson and Ford, Inc. v. Wanda Petroleum Co., 833 F.2d

72 Gh CH I987Y. oo. i as amon), 16

Blonder-Tongue Lab., Inc. v. University of Ill., 402 U.S. 313

(I971). Fe. seas 14

Bush v. Vera, 116S5.Ct. 1941 (1996) .......... 26,29. 30

Cromartie v. Hunt, 118 S.Ct. 13101998) ............. 7

“up v. County of Sac, 94 1.8..351 (1876) ........ 15

Crowe v. Cherokee Wonderland, Inc., 379 F.2d 51 (4th Cir.

FOBT) 5. ive cits Ti Bi aie a a Ei 14

Daly v. High, No. 5:97-CV-750-BO (E.D.N.C.) .... 6,7,12

Explosives Corp. of Am. v. Garlam Enters., 817 F.2d 894

(1st Cir. 1987)

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 US.32(1940) ................ 15

Inre Shaw etal. 313 U.8.1045(1996) .... couse... 5

Vv

Jaffree v. Wallace, 837 F.2d 1461 (11th Cir. 1988)... . .. 16

Kern Oil & Ref. Co. v. Tenneco Oil Co., 840 F.2d 730 (9th

Cir.), cert. denied, 488 U.S. 948 (1988) ........ 14

Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 117 S. Ct. 2186

997. sr Ee LEA 24,29

Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp., 475 U.S.

57441086)... 0. i. i i ee 19

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995) ........2.3,29, 30

Nardone v. United States, 308 U.S. 338 (1939) ......... 19

Pope v. Blue, 809 F. Supp. 392 (W.D.N.C. 1992), aff'd, 506

U.S. 301.99). cade i nih a 3

Raines v. Byrd 1178. CL 2312 (1990)... .. ou uivii iain 9

Ross v. Communications Satellite Corp., 759 F.2d 355 (4th

Cir 1088) cats su. nai on a, 20

Royal Ins. Co. of Am. v. Quinn-L Capital Corp., 960 F.2d

1286S Cir, ¥992), «our Sour rh el 16

School Bd. of the City of Richmond v. Baliles, 829 F.2d 1308

(GthCir 1987)... a. a, 19

Shaw v. Barr, 808 F. Supp. 461 (1992), rev'd in part, 509

U.S. 6300199). Lie. 50. uu oe a Es 3

Shaw v. Hunt (E.D.N.C. Sept. 12,1997) .......... passim

Vi

Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 89901996)... J. ..0cus... passim

Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F. Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C. 1994) ........ 4

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 6301993) .............. 3,24, 29

State. Wall, 271 SE24363 (NC. 1967) ...... 0. .., 11

@... v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1

LE 8 TR (WEL GR el ERR Ne 19, 27

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50-51 (1986) ....... 30

Totalpan Corp. of Am. v. Colborne, 14 F.3d 824 (2d Cir.

yt EE BR STR SEE el TL a a 14

Valley Forge Christian College v. Americans United for

Separation of Church and State, Inc., 454 U.S. 464

O82): sa. sir. Ee LE 9

White v. American Airlines, Inc., 915 F.2d 1414 (10th Cir.

19000 ial Nr eg 14

®

Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963) ....... 19

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS:

US. Const, At. TL $2... ove. Jah incon a 8,9

RULES:

Fed. R.Civ. Proc. 42a) .. om uni as vel 18

Fed. R. Civ: Proc. 36K) =. sr ar. ol a va. 19

Fed. B.Civ. ioc. Sle ot. v's ei ay. wh eT 13

Vil

Fed R.Bvid. 200... oan. ooo St Doman 20

STATUTORY PROVISIONS:

1997 N.C. Sest. Laws 1997-11 = a oe 0 11

1997 N.C. Sess. Laws 1998.7 i on 0 ok 10-12

BUS.C 31283 0 oy ah ma a 8

2US.CRI973b vn i es a aE Ly 2

TREATISES:

18 C. Wright, et al., Federal Practice & Procedure § 4405

(Supp. 1908) raids a Rs ae 14

18 James Moore, et al., Moore's Federal Practice

$13140[1)(3ded. 1908)... .... = Lo 15

18 James Moore, et al., Moore’s Federal Practice

$131.50iS1(3ded. 1098) 4... .. yi oi an 14

Wigmore, Evidence §§ 1040, 1060 (1972ed.) ....... 28

No. 98-85

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES

October Term, 1997

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official

capacity as Governor of the

State of North Carolina, et al.,

Appellants,

V.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL

FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

MOTION TO DISMISS OR,

IN THE ALTERNATIVE, TO AFFIRM

Pursuant to Rule 18.6, appellees move to dismiss the

appeal on the ground that appellants have failed to present any

justiciable issue for review by this Court, or, in the alternative,

to affirm the judgment sought to be reviewed because the court

below properly granted summary judgment and appellants have

not raised a substantial question meriting review by this Court.

2

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF THE CASE

To provide the Court a better perspective as to the

issues appellants seek to raise, appellees (plaintiffs below)

submit their Counterstatement. It begins with the racially

gerrymandered 1992 North Carolina redistricting plan, which

this Court held unconstitutional in Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899

(1996) (hereinafter “Shaw IT).

A. The 1992 Redistricting Plan

In response to the 1990 census, which revealed that

North Carolina was entitled to an additional congressional seat,

the General Assembly enacted in 1991 a redistricting plan that

included a single majority-black district. The Department of

Justice, relying upon its erroneous ‘“maximization”

interpretation of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973b, see Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995), denied

preclearance of this redistricting plan because it lacked a

second majority-black district. Soon thereafter, in January

1992, the General Assembly enacted a new plan, which

contained two majority-black districts — the First and the

Twelfth. Each had a “bizarre” shape, as did several other

@:ce The First District was in the northeastern part of

orth Carolina, where the percentage of African-Americans in

the total population is greatest. The Twelfth District wound in

a “serpentine” manner through the Piedmont region, following

generally along highway I-85 from Gastonia to Durham, and

used “white corridors” to connect concentrations of black

citizens in Gastonia, Charlotte, Winston-Salem, Greensboro,

High Point, and Durham. The Department of Justice swiftly

precleared this plan.

Under the auspices of the Republican Party, a

constitutional attack was launched against this plan on the

ground that it was a political gerrymander intended to assist

Democrats. This challenge was promptly rejected by a three-

~

be

judge district court. See Pope v. Blue, 809 F. Supp. 392

(W.D.N.C. 1992), aff'd, 506 U.S. 801 (1992). At this time the

state defendants were asserting that the plan could not be

attacked as a political gerrymander because it actually was

based on race and resulted from preclearance requirements of

the Department of Justice.

Shortly after this challenge had failed, five registered

voters in Durham, North Carolina — a city bisected by the

Twelfth District — filed suit against various federal and state

defendants. They alleged that the 1992 redistricting plan was

motivated by race and was enacted to assure the election of

African-Americans to Congress from the First and Twelfth

districts." As to the state defendants, the action was predicated,

inter alia, on a violation of the plaintiffs’ right to equal

protection under the Fourteenth Amendment — a claim which

this Court later recognized as “analytically distinct.” Shaw v.

Reno, 509 U.S. 630, 652 (1993) (hereinafter “Shaw I"); Miller,

515 U.S. at 911. After the three-judge district court dismissed

the suit as to all the defendants,’ the plaintiffs — one of whom

acted as their attorney — appealed to this Court, which noted

probable jurisdiction. When the appeal was subsequently

argued before the Court, counsel for the state-defendants

readily acknowledged that the redistricting plan was based on

race.’

'Of course, each of these two representatives would be a Democrat

since 95% or more of the African-Americans in North Carolina are

registered as Democrats.

*See Shaw v. Barr, 808 F. Supp. 461 (1992), rev'd in part, 509

U.S. 630 (1992).

’See oral argument in Shaw I, Tr. at 14, 22 (“[ T]he North Carolina

General Assembly intentionally created two majority-minority congressional

districts.” ... “There’s no dispute here over what the state’s purpose is.

There’s a dispute over how to characterize it legally, but we're not in a

disagreement over what the state legislature was trying to do” (H. Jefferson

Powell, on behalf of the state appellees)).

4

After this Court reversed the lower court and remanded

the case for trial, see Shaw I, the state defendants radically

changed their position and claimed that, although considered by

the General Assembly, race had not been a predominant motive

in drawing the two challenged districts. Although these

districts obviously were not “geographically compact,” the

defendants insisted that they were “functionally compact.”

2 the District Court readily concluded that both

stricts were race-based — although a majority of the three-

judge court held that the two districts could survive strict

scrutiny. See Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F. Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C. 1994),

On appeal by the plaintiffs to this Court, the defendants

continued to assert that neither the First nor the Twelfth District

was motivated by race.” However, on June 13, 1996 the Court

held that the creation of the Twelfth District had been

motivated predominantly by race and that, contrary to the lower

court’s decision, this district could not survive strict scrutiny

since it was not “narrowly tailored.” Shaw II. Because none of

the plaintiff-appellants in that case were registered to vote in

the First District, the Court ruled that they lacked standing to

challenge that district and therefore its constitutionality would

ot be decided. See id. at 904. The case was remanded for

rther proceedings.

Shortly thereafter, Martin Cromartie and two other

persons filed suit in the Eastern District of North Carolina to

challenge the First District as an unconstitutional racial

gerrymander. Since all three plaintiffs were registered to vote

in that district, they clearly had standing under Shaw II.

“See Defendant-Appellants’ Appendix at 61a (hereinafter “App.”).

The Justices will probably recall the much larger map of the 1992 plan

which was lodged with the Court and used by counsel for plaintiff-appellants

in the oral argument of each Shaw appeal.

Because the five plaintiffs were white, the state defendants also

contested the ruling of the three-judge district court that they had standing.

—

J

Meanwhile, the successful appellants in Shaw IT were seeking

without success to persuade the General Assembly to enact a

new redistricting plan for the 1996 elections. Those plaintiffs

also were unable to convince the three-judge district court that

it should draw a redistricting plan for the 1996 elections unless

the General Assembly promptly did so.® However, the district

court did rule that unless the Legislature drew a new plan by

April 1, 1997, the court would itself do so. In light of the

developments in the Shaw litigation, Cromartie and his fellow

plaintiffs agreed to a stay of proceedings in their action.

B. The 1997 Redistricting Plan

On March 31, 1997, the General Assembly enacted a

new redistricting plan whereunder Durham County was

removed from the Twelfth District. Since all five Shaw

plaintiffs resided in Durham, they no longer were registered to

vote in the Twelfth District; and so under Shaw II they lacked

standing to challenge that district.” After the Department of

Justice granted preclearance of the 1997 plan, the three-judge

district court entered an order on June 9, 1997 directing the

Shaw plaintiffs to advise the court within ten days “whether

they intend to claim that the plan should not be approved by the

court because it does not cure the constitutional defects in the

former plan and to identify the basis for that claim.” App. at

181a—182a. In their response, the plaintiffs stated their view

that the 1997 plan had continuing constitutional defects, but

forthrightly they pointed out that “due to their lack of standing,

°See Judgment in Shaw v. Hunt (No. 92-202-CIV-5-BR, filed July

31, 1996). Like most of the rulings of that court, it was by divided vote.

Subsequently, the Shaw plaintiffs were unsuccessful in seeking a writ of

mandamus from this Court to require the district court to adopt a remedial

plan for the 1996 elections. In re Shaw et al., 518 U.S. 1045 (1996).

"Moreover, unlike the 1992 plan, Durham County was not divided

and was placed in a geographically compact District 4. See App. at 59a.

6

any attack on the constitutionality of the new redistricting plan

should be undertaken in a separate action maintained by

persons who have standing.” Id. at 186a.

The subsequent memorandum opinion entered by the

district court on September 12, 1997 (id. at 159a-168a)

approved the plan but specifically stated:

[W]e close by noting the limited basis of

» the approval of the plan that we are empowered

to give in the context of this litigation. It is

limited by the dimensions of this civil action as

that is defined by the parties and the claims

properly before us. Here, that means that we

only approve the plan as an adequate remedy

for the specific violation of the individual equal

protection rights of those plaintiffs who

successfully challenged the legislature’s

creation of former District 12. Our approval

thus does not — cannot — run beyond the plan’s

remedial adequacy with respect to those parties

and the equal protection violation found as to

former District 12.

é- at 167a.

In October 1997, the district court dissolved the stay

order entered previously in the Cromartie action; and an

amended complaint was filed, which added plaintiffs from the

Twelfth District and additional plaintiffs from the First District.

The state defendants obtained a short extension of time to

answer and filed a motion in Shaw v. Hunt to consolidate with

it the action that had been filed by Cromartie as well as a

different action, Daly v. High, No. 5:97-CV-750-BO

(ED.N.C.),> which challenged both North Carolina’s

*The case is now captioned Daly v. Leake and will be referred to

hereafter as Daly.

7

redistricting plan and its legislative reapportionment. This

motion was denied by the Shaw three-judge court. See

Plaintiff-Appellees’ Appendix at 1a (hereinafter “P-A App.”).

On January 15, 1998 Cromartie’s action was assigned

to the three-judge district court which was considering the Daly

case.” Thereafter, the court proceeded quickly to hear

conflicting motions for summary judgment filed by the

Cromartie plaintiffs and the State defendants. The court

rendered summary judgment against the defendants and

enjoined use of the 1997 redistricting plan in the 1998

primaries and elections. See App. at 45a. The defendants

unsuccessfully sought a stay order from the district court and

then appealed its denial of a stay to this Court, which also

denied their application for a stay. The defendants

subsequently applied fruitlessly to the district court for leave to

conduct primary elections under the 1997 plan in six

congressional districts in eastern North Carolina that had been

created by that plan.

C. The 1998 Redistricting Plan

The district court had allowed the General Assembly

until May 22, 1998 to submit a redistricting plan for the 1998

elections. On May 21, 1998, a plan was enacted which left the

First District as it had been drawn in 1997, but modified the

Twelfth District. The plaintiffs filed their objections to the

1998 plan within the three day period allotted by the district

court, and the state defendants responded in a like period.

Subsequently, the plan was precleared by the Department of

Justice and then, on June 22, 1998, was approved by the three-

?Until that time the Cromartie action had been pending before

Judge Malcolm Howard, and no three-judge panel had been designated.

The panel for Daly had been designated previously.

'%See Cromartie v. Hunt, 118 S. Ct. 1510 (1998) (Stevens,

Ginsburg, and Breyer, JJ., dissenting).

8

judge district court for the 1998 election. However, the court

noted that as to the First District neither the plaintiffs’ motion

for summary judgment nor that of the defendants had been

granted. Therefore a trial would be necessary. See App. at

179a-80a. Moreover, at trial the plaintiffs could offer further

evidence as to the racial motive for the Twelfth District.!! See

id. Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1253, plaintiffs, who are appellees

in the present appeal, filed notice of appeal from the district

ourt’s denial of their requested injunction.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

The appeal from the decision of the district court should

be dismissed because appellants have not presented to the

Court a justiciable “case or controversy” for decision. See U.S.

Const., Art. II, § 2. The language of the Session Law enacting

the 1998 plan does not suffice to preserve for appellate review

the issue of the constitutionality of the 1997 plan. The

defendant-appellants have estopped themselves from denying

that this issue is moot.

If the appeal is not dismissed for want of a “case or

controversy,” the judgment entered below should be affirmed.

Appellants’ attempt to invoke claim preclusion is barred by

heir failure to plead such a defense in their answer or

otherwise to raise it in a timely manner. Even if appellants had

timely asserted a defense of claim preclusion, their argument

would fail on the merits, for no privity existed between the

present appellees and the parties involved in the earlier

judgment. Indeed, the terms of the original judgment of the

three-judge district court in September 1997 make clear that the

present appellees were not precluded by that judgment. See

App. at 167a.

The unrefuted evidence presented by appellees to the

"In preparation for that trial, a scheduling order has now been

entered which contemplates completion of discovery by December 11, 1998.

0

three-judge district court demonstrates clearly that summary

judgment was properly granted. As this Court has made clear.

circumstantial evidence alone can prove a predominantly racial

motive. Appellees’ unrefuted evidence of lack of compactness,

splitting of counties and towns along racial lines, and use of

predominantly white, narrow “land bridges” to connect

concentrations of African-Americans into a single tortured

district amply established the legislature’s predominantly racial

motive in drawing the Twelfth District. Although appellees’

strong circumstantial evidence, standing alone, proved the

General Assembly’s predominantly racial motive, direct

evidence also supports appellees’ case. When considered in

context, statements made by the legislators who drafted the

1997 redistricting plan constitute implied admissions that race

had predominated in drawing the boundaries of the Twelfth

District. The purported justifications of the plan were

unsuccessful attempts to disguise the legislators’ racial motive

and to preserve the products of the unconstitutional 1992 plan.

In granting summary judgment, the district court did not

lower the threshold for strict scrutiny, and its decision

conformed to the precedents of this Court. Although in

defending the 1997 plan, appellants have emphasized that

District 12 is only 46.67 percent black, rather than majority-

black, this fact provides no excuse for the racial gerrymander.

ARGUMENT

L THE APPEAL SHOULD BE DISMISSED AS

NONIJUSTICIABLE.

The “judicial power” of the United States can be

invoked only if there is a “case or controversy.” See U.S.

Const., Art. ITI, § 2. Indeed, “case” or “controversy” is a

“bedrock requirement.” See Raines v. Byrd, 117 S. Ct. 2312,

2317 (1997) (quoting Valley Forge Christian College v.

Americans United for Separation of Church and State, Inc.,

10

454 U.S. 464,471 (1982)). Admittedly, the difference between

“abstract question and ‘case or controversy’ is one of degree ...

and is not discernible by any precise test.” Babbitt v. United

Farm-Workers Union, 442 U.S. 289, 297 (1979).

Occasionally when a statute is superseded by a later

enactment, issues arising under the former statute become moot

and are nonjusticiable. Perhaps the General Assembly had this

ossibility in mind when it employed this language in enacting

® 1998 redistricting plan:

Section 1, G.S. 163-201 reads as

rewritten:

(a) For the purpose of nominating and

electing members of the House of

Representatives of the Congress of the United

States in 1998 and every two years thereafter,

the State of North Carolina shall be divided into

12 districts as follows:

% * *

Section 1.1: The plan adopted by this

act 1s effective for the elections for the years

1998 and 2000 unless the United States

» Supreme Court reverses the decision holding

unconstitutional G.S. 163-201(a) as it existed

prior to the enactment of this act.

1997 N.C. Sess. Laws 1998-2, enacted May 21, 1998 (emphasis

added). Section 1.1 appears to be unprecedented.'?

In enacting the 1997 redistricting plan, the General

Assembly had included a provision for substitution of a

“In the General Assembly, Section 1.1 was deleted from the House

Bill by the House Redistricting Committee but later was added back before

the bill was passed in the North Carolina House of Representatives and sent

to the Senate.

11

different plan if the 1997 plan were held unconstitutional

because its districts lacked precise numerical equality.” On the

other hand, Section 1.1 of the 1998 plan would substitute a

previous plan for an existing plan that has not been held

unconstitutional. ~~ Moreover, the substitution would be

accomplished without any formal repeal of the more recent

legislation or any specific enactment of the earlier plan."

It is uncertain what event would qualify to make the

1998 plan not “effective for the elections for the years 1998 and

2000." For example, what ruling by this Court would be

deemed to have “reverse[d] the decision holding

unconstitutional G.S. 163-201(a) as it existed prior to the

enactment of this act”? Appellees sought both a preliminary

and a permanent injunction against use of the 1997 plan.

Would a “reversal” have occurred if the Court held that

appellees had not been entitled to summary judgment but were

entitled to a preliminary injunction?'® Furthermore, unless the

Court concluded that the defendants had been entitled to

"The text of that provision is as follows:

In the event that a court of competent jurisdiction holds

that the plan enacted by section 2 of this act is invalid

because the total population range violates the one-

person, one-vote doctrine and that decision is not

reversed, then the plan enacted by section 2 of this act in

G.S. 163-201 is repealed and the following plan enacted

in G.S. 163-201.

1997 N.C. Sess. Laws 1997-11, section 3, effective March 31, 1997.

“Whether the language of Section 1.1 would be sufficient to repeal

Session Law 1998-2 or revive Session Law 1997-11 seems questionable.

If the “reversal” were to occur after the 1998 election and new state

legislators have been elected, applying Section 1.1 might be deemed to

violate the principle that one legislature cannot bind a successor legislature.

See State v. Wall, 271 S.E.2d 363, 369 (N.C. 1967).

“Whether to grant a preliminary injunction is to be determined in

the trial court’s discretion upon weighing likelihood of success against

harms to the parties from granting or denying the injunction.

12

summary judgment as to the First and Twelfth districts under

the 1997 plan, a trial would be necessary as to those districts. '®

If, despite such uncertainty, Section 1.1 were applied,

its application would create great confusion. Under its terms,

Section 1.1 would apply even to the 1998 elections if this Court

“reverses the decision” of the district court prior to the

November 1998 election date. Since that possibility seems

remote, probably the 1998 redistricting plan will govern

election of the next members of Congress from North Carolina.

If, however, this Court subsequently “reverses the decision

holding G.S. 163-201 unconstitutional,” and the 1997 plan

comes into effect, its constitutionality probably would still have

to be determined in a trial. Meanwhile, if the 1998 plan now in

effect were superseded by the less geographically compact,

more racially gerrymandered 1997 plan, the pending trial with

respect to the 1998 plan might be mooted. This potential chaos

that Section 1.1 could produce makes it highly unlikely that the

General Assembly would ever allow it to be applied.

Under these circumstances appellees submit that

Section 1.1 of the 1998 plan does not suffice to make

justiciable the issues which appellants seek to raise in this

appeal. Indeed, in adding Section 1.1 to the 1998 plan, the

General Assembly made a transparent attempt to obtain from

the Court an advisory opinion about the constitutionality of the

superseded 1997 plan.

Moreover, appellants have now estopped themselves

from claiming that the constitutionality of the 1997 plan is a

justiciable issue. On July 22, 1998, appellants submitted to the

three-judge district court a motion to consolidate this action

with the Daly case. In the memorandum attached to the motion

to consolidate, appellants state:

“The district court denied both parties’ motions for summary

judgment as to the First District in the 1997 plan, and presumably trial as to

the First and Twelfth districts in that plan would be necessary.

13

Cromartie includes a challenge to

Congressional District 12 in the State’s 1997

congressional plan, Section 2 of Chapter 11 of

the 1997 Session Laws. However, the

challenge to District 12 has been rendered

moot by the judgment of this Court declaring

District 12 unconstitutional and the permanent

injunction requiring the State to enact a new

congressional plan ... which substantially

modified the boundaries of District ]2.

Mem. at 2, n.2 (P-A App. at 3a) (emphasis added). Having

represented to the lower court in this same action that the

constitutional challenge to District 12 is moot, and appellants

having made this representation after filing their jurisdictional

statement, they are now estopped from pursuing their effort to

obtain an advisory opinion from this Court — which hardly

needs such a time-consuming distraction.

II. APPELLEES WERE NOT PRECLUDED FROM

CHALLENGING THE 1997 REDISTRICTING PLAN.

A. Appellants’ assertion of claim preclusion is

untimely and should be disregarded.

The contention by appellants in their jurisdictional

statement that claim preclusion bars the action brought by

appellees comes much too late. Both the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure and well-settled case law clearly provide that res

Judicata, or claim preclusion, is an affirmative defense which

must ordinarily be raised in the pleadings. See Fed. R. Civ.

"Ms. Tiare Smiley, Special Deputy Attorney General, signed both

the jurisdictional statement and the motion to consolidate.

14

Proc. 8(c)."* The defense of claim preclusion “cannot be raised

for the first time on appeal.” 18 C. Wright, et al., Federal

Practice & Procedure § 4405 (p. 35) (Supp. 1998)."

The rationale behind these procedural limitations is

clear: to provide the opposing party a fair opportunity to meet

the defense, see Blonder-Tongue Lab., Inc. v. University of I1l.,

402 U.S. 313, 350 (1971), and to serve the basic “policy of

pidicial economy that is integral to the preclusion doctrines,

hich] is impeded if not defeated by excessive delay.” 18

James Moore, et al., Moore's Federal Practice § 131.50[5] (3d

ed. 1998). Untimely assertion of a preclusion defense

undercuts this basic policy of judicial economy, since the court

hearing the case and the parties themselves will have already

expended scarce time and resources in arguing the case and

possibly docketing and briefing an appeal.

Appellants rely upon the September 12, 1997 order and

memorandum opinion of the three-judge district court in Shaw

v. Hunt (see App. at 157a, 159a) as a judgment that precludes

the present claims. However, that judgment was entered more

than two months before the appellants filed their answer on

November 27, 1997; and they never sought to amend that

® Moreover, appellants did not assert claim preclusion

“See also Kern Oil & Ref. Co. v. Tenneco Oil Co., 840 F.2d 730,

735 (9th Cir.), cert. denied, 488 U.S. 948 (1988); Crowe v. Cherokee

Wonderland, Inc., 379 F.2d 51, 54 (4th Cir. 1967).

“If a case has progressed past the pleadings and is in the pre-trial

or trial phase when an allegedly preclusive judgment is rendered in another

case, the defense of claim preclusion must be asserted at that time — namely,

as soon as the defense becomes available. See Totalpan Corp. of Am. v.

Colborne, 14 F.3d 824, 832 (2d Cir. 1994); see also White v. American

Airlines, Inc., 915 F.2d 1414, 1424 (10th Cir. 1990) (holding defense

“waived” when it had become available the week before trial but was not

raised until one year after judgment); Explosives Corp. of Am. v. Garlam

Enters., 817 F.2d 894, 900-01 (1st Cir. 1987) (six months’ delay in raising

the defense was “inexcusable™).

15

in their briefs supporting their motion for summary judgment

and in opposing appellees’ motion for preliminary injunction

and summary judgment. Not until they filed their jurisdictional

statement did appellants mention claim preclusion. Even

assuming, contrary to the record, that appellants’ assertion of

claim preclusion were properly grounded in law or fact, their

delay until appeal to raise this defense contradicts the often-

expressed rationale for the doctrine of res judicata and

constitutes waiver.

B. The Shaw plaintiffs were not privies or “virtual

representatives” of appellees.

Even if appellants had asserted the defense at the proper

stage of the proceedings, claim preclusion would not apply.

The judgment relied on by appellants as “preclusive” of the

appellees’ claims is the September 12, 1997 order of the three-

judge district court which conducted the remedial phase of

Shaw v. Hunt (see App. at 159a). As to appellees and their

claims, that judgment fails to satisfy the privity requirement of

claim preclusion and as a result does not bar the claims

presented by appellees.

In order for an earlier judgment to preclude a later

claim, the original judgment must involve the same parties as

the present case, or persons in privity with them.?’ See

Cromwell v. County of Sac, 94 U.S. 351, 352 (1876).

Moreover, the originak-judgment must be a final judgment

rendered on the merits. See id. When a plaintiff in the current

case was not a party to the original judgment, that plaintiff must

be in privity with the original plaintiffs if the original judgment

is to have any preclusive effect. See Hansberry v. Lee, 311

“Privity is generally defined as the existence of an express or

implied legal relationship between two or more parties, such as family

members, members of a class action, employers-employees, administrators,

and executors. See Moore's § 131.40[1].

16

U.S. 32, 41-43 (1940) (describing privity in class actions).

Closely related to the traditional concept of privity is the

somewhat more recent notion of “virtual representation,” which

exists if the original plaintiff’s interests are so closely aligned

as to be identical with those of the present plaintiff. For this

doctrine to apply, however, the parties must have more than a

similarity of interests. Indeed, the Fifth Circuit has adopted a

ivity-like standard for virtual representation — the parties

@. enjoy an express or implied legal relationship to be

“virtual representatives.” See Royal Ins. Co. of Am. v. Quinn-L

Capital Corp., 960 F.2d 1286, 1297 (5th Cir. 1992).?' Other

circuits have abandoned the legal relationship requirement for

a factor-based analysis, identifying as relevant criteria

“participation in the first litigation, apparent consent to be

bound, apparent tactical maneuvering [to avoid preclusion], and

close relationships between the parties and nonparties.” Jaffree

v. Wallace, 837 F.2d 1461, 1467 (11th Cir. 1988) (finding that

original plaintiff was virtual representative of current plaintiffs,

who were his wife and children) (citation omitted).

In the context of the present case, the same-party/privity

requirement is not satisfied. Although the September 1997

proval did constitute a final judgment on the merits for the

aw II plaintiffs, the district court carefully excluded other

parties from the judgment’s effect:

[Wle only approve the plan as an adequate

remedy for the specific violation of the

individual equal protection rights of those

plaintiffs who successfully challenged the

legislature’s creation of former District 12. Our

!'See also Benson and Ford, Inc. v. Wanda Petroleum Co., 833

F.2d 1172, 1175 (5th Cir. 1987) (parties were represented by same attorney

and asserted same claim based upon same facts, but due to absence of

express or implied legal relationship later action was not precluded).

17

approval thus does not — cannot — run beyond

the plan’s remedial adequacy with respect to

those parties and the equal protection violation

found as to former District 12.

Shaw v. Hunt (E.D.N.C. Sept. 12, 1997) (App. at 167a). Thus

the approval of the plan was a final judgment only as to those

Shaw plaintiffs whose standing had been recognized by this

Court in Shaw II. Those plaintiffs were all residents of Durham

County, part of which was included in District 12 under the

1992 plan. The current appellees are residents of Edgecombe

County in District 1 under the 1997 plan and Rowan, Guilford,

and Mecklenburg counties in District 12. They have no express

or implied legal relationship to any of the Durham County

plaintiffs identified in the September 1997 judgment.

Appellants’ assertion that the Shaw plaintiffs were

“virtual representatives” of the current appellees also fails. The

plaintiffs whose claims were resolved by the September 1997

order had successfully challenged the creation of District 12 by

the 1992 redistricting plan. The present appellees, by contrast,

challenged Districts 1 and 12 as drawn in the 1997 redistricting

plan. Appellees may have a similarity of interests with the

Shaw plaintiffs; but they lack the level of identification

necessary for virtual representation.” That which might

constitute virtual representation — e.g., consent to be bound, a

close relationship between the parties, tactical maneuvering to

avoid preclusion — is absent.

C. The district court conducting the remedial phase

of Shaw v. Hunt specifically provided in its

order and opinion that its decision only applied

The fact that the two sets of plaintiffs are represented by the same

attorney is of little relevance. Indeed, it seems odd to suggest that an

attorney experienced in redistricting litigation cannot represent those who

seek his pro bono counsel.

18

to the plaintiffs and claim identified by the

Supreme Court before remand.

In handling the remedial proceedings in Shaw v. Hunt,

the district court’s responsibility was to oversee the fashioning

of a remedy to address the constitutional violations suffered by

the original plaintiffs. Since this Court had dismissed the

claims concerning the constitutionality of the First District, the

istrict court had no authority to consider the 1997 plan’s

adequacy to remedy any constitutional flaw of the First District.

Contrary to appellants’ suggestion, potential constitutional

challenges that might be made to the 1997 plan’s First and

Twelfth Districts by persons who had standing were not

“snuffed out” by the order of September 12, 1997. To the

contrary, in its memorandum opinion accompanying that order,

the three-judge district court expressly noted the limitations on

its approval and made no determination regarding the

challenges to the 1997 plan that might be made by persons who

had standing.”

III. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY GRANTED

SUMMARY JUDGMENT ON THE

» UNCONSTITUTIONALITY OF DISTRICT 12.

Assuming arguendo that appellees bore the burden of

ZFurther evidence of the separate identities of the present action

and the Shaw remedial judgment is the Shaw panel’s denial of the

defendants’ motion to consolidate Shaw, Cromartie and Daly. The Shaw

defendants’ motion, filed in October 1997, requested that the three cases be

consolidated pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. Proc. 42(a) because they presented

common issues of law and fact. Even though the threshold for

consolidation is significantly less demanding than that required to establish

claim preclusion or even to prove that an original plaintiff was a “virtual

representative” of a later plaintiff, the court denied the motion and allowed

the three cases to proceed independently. See P-A App. at 1a.

19

persuasion — which they dispute — appellees nevertheless met

the standard for summary judgment. Summary judgment is

appropriate when there is no genuine issue as to any material

fact and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of

law. See Fed. R. Civ. Proc. 56(c). The moving party is entitled

to summary judgment when a rational trier of fact, after

considering the record as a whole, could not find for the non-

moving party. See Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith Radio

Corp., 475 U.S. 574, 587 (1986). The “mere existence of a

scintilla of evidence” for the non-moving party’s position is

insufficient to defeat a properly supported motion; there must

be enough evidence for a reasonable jury to find for the non-

**To obtain summary judgment, appellees were required by the

district court to establish as an irrefutable fact that the General Assembly

had a predominantly racial motivation in drawing the 1997 plan. Instead,

the burden should have been placed on appellants to show that there was no

racial motive and that there was no “vestige” of the 1992 racially-motivated

plan. Only this approach is consistent with the Court's decisions in other

fields of equal protection law. For example, in the school desegregation

cases, once an equal protection violation had been proved, the local school

authorities and the district courts were required to “eliminate ... all vestiges

of state-imposed segregation.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ.,402 U.S. 1, 15 (1971). Having established that continuing violation,

a plaintiff is “entitled to the presumption that current disparities are causally

related to prior segregation, and the burden of proving otherwise rests on the

defendants.” School Bd. of the City of Richmond v. Baliles, 829 F.2d 1308,

1311 (4th Cir. 1987). Likewise in criminal cases, the state must show that

any “taint” caused by a violation of a defendant's rights has been attenuated

and that there is no “fruit of the poisonous tree.” See Wong Sun v. United

States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963); Nardone v. United States, 308 U.S. 338

(1939). Although a broad scope should be allowed for legislative discretion,

once it has been proved that this discretion has been improperly exercised

the courts have a special responsibility to assure that the unconstitutional

intent has been extinguished when the legislature takes remedial action.

Since the General Assembly had enacted an unconstitutional redistricting

plan in 1992, appellants should have been required to prove that the 1997

plan was not racially motivated.

20

moving party. Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242,

252 (1986).7

To prove an equal protection violation in a redistricting

case, the plaintiff may prove a race-based motive “either

through circumstantial evidence of a district’s shape and

demographics or through more direct evidence going to

legislative purpose.” Shaw II, 517 U.S. at 905 (citations

mitted) (emphasis added). Thus, circumstantial evidence

one may suffice to warrant summary judgment. Here there is

an abundance of circumstantial evidence — much of which

either was provided by appellants or was subject to judicial

notice under Fed. R. Evid. 201. Moreover, upon analysis, the

contradictions and hidden meanings in the statements of

legislators help establish that the Twelfth District was drawn

with a predominantly racial motive.

A. The shape and demographics of District 12 and

its disregard of traditional redistricting

principles prove the predominantly racial

motive.

A visual comparison of the maps makes evident that the

welfth District in the 1997 plan bears an unacceptable

ikeness to its predecessor “I-85" district in the 1992 plan® —

the plan this Court held unconstitutional in 1996 (Shaw II).

®See also Aleyska Pipeline Serv. Co. v. U.S. E.P.A., 856 F.2d 309,

314 (D.C. Cir. 1988) (“a motion for summary judgment adequately

underpinned is not defeated simply by a bare opinion or an unaided claim

that a factual controversy persists”); Ross v. Communications Satellite

Corp., 759 F.2d 355, 365 (4th Cir. 1985) (“[u]nsupported allegations as to

motive do not confer talismanic immunity from Rule 56").

See App. at 59a, 61a. Also, appellees are lodging with the Court

four maps which were before the district court and which make even clearer

that those who drafted the 1997 plan followed the race-based approach used

in the 1992 plan.

24

The district “winds its way from Charlotte to Greensboro along

the Interstate-85 corridor, making detours to pick up heavily

African-American parts of cities such as Statesville, Salisbury,

and Winston-Salem.” See Mem. Op. (App. at 19a). District 12

splits all of its six counties; and it is the only congressional

district in the 1997 plan that does not contain a single whole

county. Significantly, the three largest of the six counties are

divided along racial lines. As Dr. Ron Weber, a redistricting

expert, points out:

[T]he racial makeup of the parts of the six sub-

divided counties assigned to District 12 include

three with parts over 50 percent African-

American .... Almost 75 percent of the total

population in District 12 comes from the three

county parts which are majority African-

American in population ... [and which] are

located at the extremes of the district.

Weber Decl. 18. Mecklenburg, Forsyth, and Guilford

counties — which contain almost 75 percent of District 12's

population — are divided in such a manner that the portion of

each county which contains a majority of African-Americans is *

included in District 12, while the portion containing a greater

concentration of white voters is excluded.” Dr. Weber also

observes that the splitting of political subdivisions to maximize

black population in the Twelftlf District occurred not only for

“Under the 1997 plan, the portion of Mecklenburg County

included in District 12 was 51.9% black and 45.9% white, while the portion

of the county placed in neighboring District 9 was 90.4% white and a mere

7.2% black. The portion of Forsyth County included in the Twelfth was

72.9% black and 26.3% white, while the part of Forsyth included in District

5 was 87.7% white and only 11.1% black. The part of Guilford County

included in District 12 was 51.5% black and 46.5% white, while the portion

assigned to District 6 was 88.2% white and 10.2% black. See Weber Decl.

at Table 2.

22

counties but also for cities and towns. The major cities in the

Twelfth District — Charlotte, Greensboro, Winston-Salem, High

Point and Statesville — are split along racial lines, with the

precincts included in District 12 having a greater population of

black citizens than the precincts left for other districts.® In

addition to the egregious splitting of counties and cities along

racial lines, the plan also employs narrow “land-bridges” to

connect the far-flung communities of African-Americans and

@.. surrounding districts contiguous.”

Appellees have also submitted other uncontroverted

evidence as to the disregard for traditional districting principles

— such as compactness and geographical integrity — in creating

District 12 under the 1997 plan. For example, Professor

Timothy O’Rourke’s evaluation of the compactness of District

12 using recognized statistical methods reveals that of the

United States’ 435 congressional districts, “[i]f the 1992

rankings had remained unchanged, the [1997] version of the

Twelfth would still stand as the 430th least compact district on

the dispersion measure and it would rank 423 on the perimeter

The portion of Charlotte included in District 12 is 59.5% black,

@ the portion left for District 9 is only 8.1% black. The portion of

Greensboro placed in District 12 is 55.6% black, while the part of the city

left for District 6 is only 10.7% black. The portion of Winston-Salem

assigned to District 12 is 77.4% black, while the portion assigned to District

5 is only 16.1% black. The portion of High Point placed in District 12 is

51.4% black, while the portion in District 6 is only 11.7% black. In

Statesville, the portion included in District 12 is 75.4% black, while the

portion included in District 10 is only 18.9% black. See Weber Decl. at

Table 4.

®For example, in District 12 “a narrow land bridge is used to

connect Davidson County with the city of Greensboro in Guilford County.”

(Weber Decl. J 31.) One precinct at the southern tip of District 12 is

divided so that its northern half -- all precinct residents but one -- is in the

Twelfth District, while its southern half -- only one person -- forms a two-

mile wide land bridge connecting the otherwise non-contiguous wings of

District 9. See O'Rourke Aff. J 5(c); see also App. at 59a.

23

measure.” O’Rourke Aff. J 4(d). Indeed, the Twelfth District’s

dispersion and perimeter compactness figures fall below those

of contested districts from four other states: Florida, Georgia,

Illinois, and Texas. See Mem. Op. (App. at 21a).

B. Direct evidence confirms the predominantly

racial motive in drawing District 12.

In submitting the 1997 plan for Section 5 preclearance,

the State represented to the Department of Justice that five

factors were emphasized in locating and shaping the Twelfth

District. See App. at 63a. That representation is misleading in

several respects.* Moreover, although “geographic

compactness’ is mentioned in the Section 5 submission as one

of five factors considered in drawing the plan, the affidavit of

Senator Roy A. Cooper, III, Chair of the Senate Redistricting

Committee, omits it as a factor (App. at 72a), and that of

Representative McMahan, Chairman of the House Redistricting

Committee, makes no specific reference to geographic

compactness as a factor that was considered.®' Id. at 81a, 83a.

**Contrary to the State’s representation, (1) the Twelfth District

split all of its six counties; (2) it has a long “corridor” of predominantly

white precincts to connect concentrations of blacks in Charlotte, Winston-

Salem, and Greensboro -- a corridor only one precinct wide in many places;

(3) it is not geographically compact and, indeed, ranks at the bottom of the

compactness scale for congressital districts in North Carolina and

nationally; (4) it is “functionally compact” only if “function” is equated to

race; (5) it lacks “ease of communication” in any meaningful sense because

the district’s voters are divided between two Metropolitan Statistical Areas

(MSA's) and spread over several media markets.

*'It is typical of the inconsistencies and contradictions on the part

of the state legislators and appellants that Senator Cooper declared in a

committee meeting in March 1997, “We've strived to follow the direction

of the Supreme Court to draw more geographically compact districts.”

State’s Section 5 Submission, 97C-28F-4D(3) at 1. Yet Senator Cooper

failed to acknowledge this effort in his affidavit, and appellants concede now

that “the legislature did not ... select geographical compactness as a criterion

24

The spuriousness of the representations in the Section 5

submission is itself evidence of the effort to disguise the

General Assembly’s racial motive.

The submussion’s reference to “functional compactness”

as a factor in drawing the Twelfth District and the use of the

same term by Senator Cooper in his affidavit (id. at 72a) reveal

another tactic used to mask the legislature’s racial motive.

a the Section 5 submission and Senator Cooper define this

rm to mean “grouping together citizens of like interests and

needs.” Id. However, the separation of predominantly black

precincts in Greensboro, Charlotte, Winston-Salem, and High

Point from neighboring white precincts in those cities can only

be related to that definition of “functional compactness” if it is

assumed that African-Americans in those cities all have “like

interests and needs,” and that the persons in neighboring

predominantly white precincts in those cities have different

“interests and needs.” Obviously, such logic relies on “racial

stereotyping,” which the Court denounced in Shaw I.

The Section 5 submission (see App. at 64a) and the

affidavits of Senator Cooper (see id. at 74a-75a) and

Ww receive independent emphasis in drawing the plan.” J.S. at 22.

*’Citing Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 117 S. Ct. 2186, 2195

(1997), appellants assert that a contested district’s lack of compactness does

not necessarily prove a predominantly racial motive. In that case, however,

the challenged legislative district’s shape did not “stand out as different from

numerous other Florida House and Senate districts.” Id. In North Carolina,

on the other hand, District 12 is significantly less compact than the state’s

other congressional districts.

*Previously, in seeking to justify race-based District 12 under the

1992 plan, the same counsel for the State minimized “geographic

compactness” and relied on “functional compactness.” See State Appellees’

Brief in Shaw II, at 21-22. In their view “to a large extent, compactness is

in the eye of the beholder.” Tr. of Argument at 26. This premise, while

ignoring the statistical measures of “compactness,” provides appellants a

tool for concealing the actual racial motive.

25

Representative McMahan (see id. at 83a) also assert that

maintaining the 6-6 “partisan balance” in the North Carolina

congressional delegation was a primary goal of the General

Assembly. Senator Cooper claims that the Twelfth District’s

boundaries were based not on race but on - partisan

considerations and that the district was designed to be a

“Democratic island in a largely Republican sea,” with precincts

chosen for inclusion in the district on the basis of their

percentages of Democratic voters. See id. at 77a.

The speciousness of this “partisan disguise” becomes

evident when the facts of the 1997 plan and the demographics

of districts neighboring District 12 are closely examined. A

number of the predominantly black precincts in Mecklenburg

County which were placed in the Twelfth District — precincts

which also are predominantly Democratic — are directly

adjacent to precincts that are predominantly white and

Democratic. The predominantly white Democratic precincts,

however, were placed in the neighboring Ninth District. If

District 12 was created as a Democratic district, there is no

reason why these precincts were excluded, especially in light of

their voting performance in the 1990 U.S. Senate election in

North Carolina. Democratic senatorial candidate Harvey Gantt,

an African-American, received the majority of votes in these

predominantly white precincts over incumbent Republican

Senator Jesse Helms. For example, Precinct 10 of

Mecklenburg County is predomfriantly white in population (89

percent), and is 63 percent Democratic. Seventy-three percent

of the votes in Precinct 10 were cast for Gantt in 1990 —

certainly a sound showing of support for an African-American

candidate across racial and party lines. Precinct 21 of

Mecklenburg County is 85 percent white, and 59 percent

Democratic; and 60 percent of its voters chose Mr. Gantt.

Precinct 38 gave 54 percent of its votes to Gantt, and is 52

percent Democratic, yet it too was excluded from District 12 —

and its white population is 85 percent. All three precincts were

26

excluded from District 12 — apparently left to sink in the

“Republican sea.” Similar statistics prove the same situation

exists in Forsyth and Guilford counties under the 1997 plan.

As the district court concluded, “The common thread woven

throughout the districting process is that the border of District

12 meanders to include nearly all of the precincts with African-

American population proportions of over forty percent which

lie between Charlotte and Greensboro, inclusive.” App. at 20a.

» This Court recognized a similarly specious “partisan

disguise” in the recent Texas redistricting litigation. There the

State defendants argued, just as appellants do here, that the

gerrymandered districts were drawn with political, not racial,

motivations. This defense was rejected because “to the extent

that race is used as a proxy for political characteristics, a racial

stereotype requiring strict scrutiny is in operation.” Bush v.

Vera, 116 S. Ct. 1941, 1956 (1996). However, disregarding

Bush, the General Assembly used race to achieve an intended

result of having two African-American members of Congress

— who would inevitably be Democrats.>

*In Forsyth County, Precinct 1408, which is 71% white, is two-

@ Democratic and cast three-fourths of its votes for Gantt in 1990, was

excluded from District 12. Precinct 1422 — two-thirds white and three-

fourths Democratic — cast three-fourths of its votes for Gantt yet was

excluded. In Guilford County, Precinct 11, which is 80% white and 62%

Democratic, gave 67% of its votes to Gantt but was excluded. Precincts 14

and 17, which are respectively 58% and 62% Democratic and 82% and 85%

white, also granted overwhelming victories to Gantt; yet both were excluded

from District 12.

**The circumstance that in North Carolina more than 95 percent of

African-American registered voters are Democrats makes it easier to

disguise the legislature’s racial motivation. However, even appellants’ own

expert concluded that there exists “a substantial correlation between the path

taken by the boundary of the Twelfth District and the racial composition of

the residents of the precincts touching that boundary, the tendency being to

include precincts within the district which have relatively high black

representation.” Peterson Aff. (App. at 87a).

27

Appellants have often claimed that the 1997 plan was

based in part on “incumbency considerations,” which in turn

were closely related to maintaining the existing partisan

balance. Allegedly, the twelve districts were drawn so that no

incumbent from the 1992 election (which took place under an

unconstitutional districting plan) was placed in the same district

as another incumbent. See App. at 74a-75a. Moreover, the

plan was drawn to include select groups of voters within or

without certain districts in order to preserve the electoral

chances of those incumbents.

Protecting an unconstitutionally-elected incumbent is a

questionable method of “correcting the condition which offends

the Constitution,” the purported goal of an equitable remedy.

Swann, 402 U.S. at 16. This is especially true when, as here, it

is apparent that the legislature used the race of voters placed in

Districts 12 and 1 to achieve the intended result of having two

African-American Representatives from North Carolina.

Accepting the rationale of appellants’ argument would permit

the total negation of the Court’s decisions in other cases

involving racial gerrymandering; it signifies that a result

obtained by racial gerrymandering can thereafter be perpetuated

if the legislators recite that they wish to “protect incumbents”

or “maintain partisan balance.” Indeed, under appellants’ logic

the identical plan held unconstitutional in Shaw II could be

reenacted on the grounds that it was no longer racially

(Ve

*In a discussion on the House Floor on March 26, 1997, Rep.

McMahan offered reasons why he believed District 12 would “stand a Court

test.” “1. Not a Majority/Minority District .... 2. Population in 12 has

homogeneous interest — comprised of many citizens living in an urban

setting. 3. Drawn to protect the Democratic incumbent.” State’s Section 5

submussion, 97C-28F-4F(1), at 2. In a committee meeting the previous day,

Rep. McMahan stated that District 12 “recognizes racial fairness and is

friendly to our incumbents which we [Sen. Cooper and Rep. McMahan] both

determined on the front end to be an important consideration in the process.”

97C-28F-4E(4) at 1.

28

motivated but instead was politically motivated.’

Interestingly, in justifying the 1997 plan with its 46.67

percent black Twelfth District, appellants used the same

justification of “partisan balance” and “maintaining

incumbents” that they have used in attempting to justify the

1998 redistricting plan — which has a 35 percent African-

American population, does not split all of its five counties, and

is more geographically compact.®® In short, the legislators now

claim to be able to meet their “partisan objectives” with a

district that is less racially-gerrymandered. This, in itself, is

another indication that the 1997 plan was chosen instead of

some other plan more consistent with traditional race-neutral

districting principles because the 1997 plan gave more certainty

of reaching the desired racial result.

IV. DISTRICT 12 IS SUBJECT TO STRICT

SCRUTINY UNDER THE EQUAL

PROTECTION CLAUSE.

In their jurisdictional statement, appellants state the

“Questions Presented” in a misleading way.>®> Moreover, the

*’As indicated in the Counterstatement, appellants have already

displayed their adroitness in moving from one rationale to another, i.e.,

beginning in 1992 with a defense against the political gerrymandering suit

that the plan was racially gerrymandered, and later seeking to justify the plan

as having a political motivation. The numerous, oft-repeated contradictions

and evasions on the part of appellants serve to impeach their affidavits and

constitute implied admissions of the actual racial-based motive. Cf.

Wigmore, Evidence §§ 1040, 1060 (1972 ed.).

*See Mem. Op. (App. at 178a-79a).

*Contrary to Question 1’s implication, the “shape and racial

demographics” of District 12 were not “standing alone.” Those

circumstances and many others — such as the state’s evasive tactics over a

seven-year period — lead any objective factfinder to the inevitable

conclusion that a racial motive was paramount. Similarly, contrary to

Question 3’s implication, the Twelfth District was more than “slightly

29

jurisdictional statement erroneously intimates that the

pronouncements of Shaw I and Shaw II are irrelevant to the

1997 version of District 12 because the population of that

district was only 46.67 percent black — rather than majority-

black. See, e.g., Question 3, J.S. at I; 27. However, the

opinion of the Court in Miller, 515 U.S. at 916, speaks in terms

of a “significant number” of persons being placed “within or

without” a certain district because of their race. Clearly a

“significant number” of African-Americans in Guilford and

Forsyth counties — over 113,000 — were placed in the Twelfth

District because of their race. Nothing in the Court’s opinion

in Bush, 517 U.S. at 962-63, suggests that strict scrutiny does

not apply when a legislature neglects traditional districting

criteria due to a predominantly racial motive, whether or not a

district is majority-minority. Although appellants rely on

Lawyer, 117 S. Ct. at 2191, 2195, the challenged district in that

case — though not majority-minority — did not “stand out as

different in shape” from other Florida districts, and the

plaintiffs’ circumstantial evidence was insufficient to prove a

predominantly racial motive.

In the present case, the evidence of the legislature’s

disregard of traditional districting principles is overwhelming,

and the district court properly concluded that there was no

irregular,” the concentration of African-Americans was much higher in

District 12 and many of its precincts than in adjoining districts and

precincts, and the district violated many of the race-neutral criteria which —

intermittently — the state purported to be following.

“In drawing the Twelfth District, the legislators also labored under

the false impression that Shaw's indictment of racial gerrymanders applied

only to majority-minority districts. See, e.g., Comments of Rep. McMahan,

supra n.35; see also Comments of Sen. Cooper during Senate Floor Debate

of March 27, 1997 (“[T]he test outlined in Shaw vs. Hunt will not even be

triggered because [District 12] is not a majority minority district and you

won’t even look at the shape of the district in considering whether it is

constitutional”) (97C-28F-4F(2), at 5) (emphasis added).

30

litigable issue as to whether this placement was primarily

motivated by race.’ It inevitably follows under Shaw, Miller,

and Bush that the test of strict scrutiny must be applied.” In

that event, District 12 fails the test and the 1997 plan is

unconstitutional.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, appellees respectfully request

this Court to dismiss the appeal, or, in the alternative, to

summarily affirm the decision of the court below.

Respectfully submitted,

MARTIN MCGEE ROBINSON O. EVERETT*

Williams, Boger, Grady, Everett & Everett

Davis & Tittle, P.A.

Attorneys for the Appellees

August 26, 1998 *Counsel of Record

“'The district court had before it, inter alia, the declarations of Dr.

Ron Weber, Dr. Tim O’Rourke, and other leading experts who explained

why they readily concluded that race was the predominant motive for

District 12. See, e.g., P-A App. at 5a-7a.

“Admittedly, when strict scrutiny is applied, special rules may

apply to a majority-black district, see Thornburg v. Gingles, and a majority-

minority district may be created if there is a “geographically-compact”

majority-minority population. 478 U.S. 30, 50-51 (1986). However, the

appellants’ assertion that strict scrutiny was improperly applied suggests that

appellants have confused the Gingles preconditions with the requirements

of Shaw and its progeny.

APPENDIX

A

E

N

a

A

T

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Shaw v. Hunt, CA 92-202-CIV-5-BR. Order of

United States District Court for the Eastern

District of North Carolina, October 16, 1997 la

Excerpts from Defendants’ Memorandum, July 22, 1998 . 3a

Excerpts from Declaration of Dr. Ronald E. Weber . . .... 5a

la

SHAW y. HUNT, CA 92-202-CIV-5-BR, ORDER OF

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

WESTERN DIVISION

Civil Action No. 92-202-CIV-5-BR

RUTH O. SHAW, et al,

Plaintiffs,

and

JAMES ARTHUR “ART” POPE,

et al., Plaintiff-

Intervenors,

V. ORDER

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., et al.,

Defendants,

and

RALPH GINGLES, et al.,

Defendant-

Intervenors.

bi

i

l

e

a

a

C

T

,

C

R

,

WE

he

T

S

R

h

M

O

N

E

I

he

L

e

i

R

R

Defendants’ motion to consolidate Cromartie v. Hunt

(N0.4:96-CV-104-H) (E.D.N.C.) and Daly v. High (No.5:97-

CV-750-BO) (E.D.N.C.) with the above-captioned matter is

DENIED.

2a

SHAW ORDER OF OCTOBER 16, 1997, CONT'D...

This 16 October 1997.

For the Court: /s/ W. Earl Britt

United States District Judge

3a

DEFENDANTS’ MEMORANDUM, JULY 22, 1998

[Caption omitted in printing]

DEFENDANTS’ MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF

CONSOLIDATION

Defendants have moved the Court pursuant to Federal

Rule of Civil Procedure 42(a), to consolidate for purposes of

trial the case of Daly v. Leake, No. 5:97-CV-750-BO(3), with

the case of Cromartie v. Hunt, No. 4:96-CV-104-BO(3).

Consolidation of these cases is appropriate because the actions

involve common questions of law and fact; in addition,

consolidation will avoid the risk of inconsistent adjudications

and limit the burden on parties, witnesses and available judicial

resources posed by separate trials.

FACTS

The Daly litigation involves an equal protection:

challenge to various North Carolina State House and State

Senate Districts,’ as well as Congressional Districts 1 and 3, as

unconstitutional racial gerrymanders. Similarly, the Cromartie

litigation involves an equal protection challenge to

Congressional District 1 as an unconstitutional racial

gerrymander.> Both of these cases are currently pending

Daly plaintiffs are challenging House Districts 7, 28, 79,

87.97 and 98, and Senate Districts 4, 6, 7, 38, and 39.

-

“

Cromartie includes a challenge to Congressional District

12 in the State’s 1997 congressional plan, Section 2 of Chapter 11 of the

1997 Session Laws. However, the challenge to District 12 has been

rendered moot by the judgment of this Court declaring District 12

unconstitutional and the permanent injunction requiring the State to enact a

new congressional plan, Chapter 2 of the 1998 Sessions Laws [sic] (the

1998 plan), which substantially modified the boundaries of District 12.

Daly also includes challenges to Congressional Districts 5, 6, 9 and 12 in the

1997 congressional plan. These challenges have been rendered moot by the

4a

DEFENDANTS’ MEMORANDUM, JULY 22, 1998,

CONT'D...

before the same three-judge panel.

This the 22nd day of July, 1998.

MICHAEL F. EASLEY

ATTORNEY GENERAL

/s/ Edwin M. Speas, Jr.

Chief Deputy Attorney General

N.C. State Bar No. 4112

/s/ Tiare B. Smiley

Special Deputy Attorney General

N.C. State Bar No. 7119

N.C. Department of Justice

P.O. Box 629

Raleigh, N.C. 27602

(919) 716-6900

enactment of the 1998 congressional plan which substantially modified the

boundaries of these four districts. Neither the Cromartie or Daly plaintiffs

have amended their complaints to challenge District 12 in the 1998 plan.

Because Districts 1 and 3 were re-enacted in the 1998 legislation with no

modifications to their boundaries, these claims by the Cromartie and Daly

plaintiffs are not moot.

—

Ja

DECLARATION OF DR. RONALD E. WEBER

[Caption omitted in printing]

38. To sum up my conclusions about the predominant

use of race and the subordination of race-neutral traditional

districting principles to race by the state of North Carolina in the

creation of the Congressional districts in 1997, I find that a

significant number of persons are assigned to districts in eastern

North Carolina and the Piedmont Region based on race. I

conclude that race was a predominant factor in the construction

of Districts 1, 3, 9, and 12. To a lesser extent race also affected

the drawing of Districts 5, 6, and 10 in that certain counties in

those districts were split on a racial basis. I also conclude that

race-neutral traditional districting principles were subordinated

in the creation of these districts. The state of North Carolina did

not adhere to compactness in creating the districts, more

counties, cities, and towns were split than needed in constructing

the districts, and community of interest regions were not

followed in the design of the districts. I found districts 3, 9, and

12 to be only technically contiguous, and that those three

districts were not functionally contiguous.

OI. NUMEROSITY AND CONCENTRATION OF

AFRICAN-AMERICAN VOTERS

39. I conclude that the African-American voting age

population in no part of North Carolina is sufficiently numerous

or geographically compact enough to be a majority of voters

using traditional districting principles to draw a single-member

Congressional district. An equitably populated Congressional

district in North Carolina needs a total population of about

552,386 persons using 1990 Census of Population data. First, an

examination of maps and statistical data at the county, city, and

precinct levels by race indicates that there are is [sic] only one

6a

DECLARATION OF DR. RONALD E. WEBER,

CONT’D....

potential area where one might locate enough African-American

persons of voting age to create a geographically compact district.

The area is in the northeastern part of the state located primarily

among the counties of the Inner Coastal Plain region.

* * * *

CONCLUSION

46. On the basis of my above analysis, I conclude:

(1) that race was the predominant factor used by the

state of North Carolina to draw the boundaries of the

1997 U.S. Congressional districts;

(2) that the state of North Carolina in creating the 1997

U.S. Congressional districting plan subordinated

traditional race-neutral districting principles, such as

compactness, contiguity, respect for political

subdivisions or communities defined by actual shared

interests, to racial considerations;

(3) that the African-American voting age population in

North Carolina (particularly the northeastern part of the

state) is not sufficiently large nor geographically

concentrated enough to constitute a potential voter

majority using traditional districting principles to draw

a single-member Congressional district;

(4) that the majority-minority U.S. Congressional

Districts 1 and 12 in the 1997 North Carolina plan is

overly safe from the standpoint of giving a candidate of

choice of African-American voters an opportunity to be

elected, thus questioning whether the plan was narrowly

tailored to satisfy a compelling state interest.