Hardback 3 Index

Public Court Documents

November 8, 1991 - June 18, 1992

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Hardback 3 Index, 1991. d9a9b53f-a546-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e6b56532-6046-4a0f-a81f-ff3e12007e09/hardback-3-index. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

Date

11/8/91

1/15/92

2/24/92

3/13/92

3/13/92

3/16/92

3/31/92

3/31/92

4/1/92

4/1/92

4/1/92

4/1/92

4/1/92

4/16/92

4/16/92

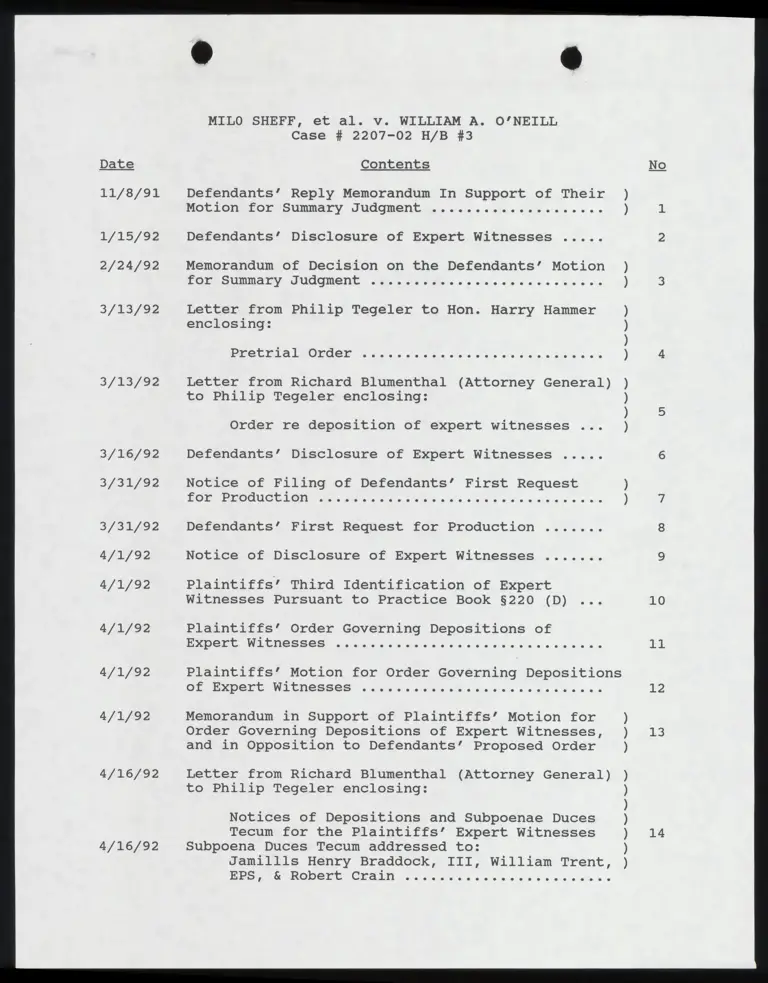

MILO SHEFF, et al. v. WILLIAM A. O'NEILL

Case # 2207-02 H/B #3

Contents

Defendants’ Reply Memorandum In Support of Their )

Motion for Summary Judgment .......... “ois vinivian nie )

Defendants’ Disclosure of Expert Witnesses .....

Memorandum of Decision on the Defendants’ Motion )

for Summary Judgment ..seveosvsves So ninie wma nhiners )

Letter from Philip Tegeler to Hon. Harry Hammer )

enclosing: )

)

) PEE EE a] CFO sass cvs nensnussssoenesvinioee

Letter from Richard Blumenthal (Attorney General) )

to Philip Tegeler enclosing: )

)

) Order re deposition of expert witnesses ...

Defendants’ Disclosure of Expert Witnesses .....

Notice of Filing of Defendants’ First Request )

FOI ProdUCLION ss sss ev sss eessnosncenssnssnennss )

Defendants’ First Request for Production .......

Notice of Disclosure of Expert Witnesses .......

Plaintiffs’ Third Identification of Expert

Witnesses Pursuant to Practice Book §220 (D) ...

Plaintiffs’ Order Governing Depositions of

EXDOrt WIitNOSSOS vies vvvsvenvreccnssnsssonsnsenssnes

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Order Governing Depositions

Of EXpert Witnesses cece cecstsvsecenesonecuionns

Memorandum in Support of Plaintiffs’ Motion for

Order Governing Depositions of Expert Witnesses,

and in Opposition to Defendants’ Proposed Order

a

”

N

a

”

N

a

e

”

Letter from Richard Blumenthal (Attorney General)

to Philip Tegeler enclosing:

Notices of Depositions and Subpoenae Duces

Tecum for the Plaintiffs’ Expert Witnesses

Subpoena Duces Tecum addressed to:

Jamillls Henry Braddock, III, William Trent,

EPS, & RODETL Cralll vue cesseessnennnsossinese

V

a

”

N

s

”

N

t

”

N

a

i

?

w

i

w

t

“

u

s

?

10

1l

12

13

14

MILO SHEFF, et al. v. WILLIAM A. O’NEILL

Case # 2207-02 H/B #3

Date Contents No

4/27/92 Letter from Philip Tegeler to John Whelan (Asst.

Attorney General) re: Depositions of Expert

RitNeSSeS oon vien certo nnrussnsnvesosssnnsssnsoe es 15

4/30/92 Letter from Philip Tegeler to Clerk of Court

(Superior Court) forwarding to Judge Hammer:

Motion for Extension of Time to Respond

to Defendants’ First Request for Production

)

)

) 16

)

)

5/14/92 Motion for Order of COMPliance ..cceeeeececeniss 17

5/15/92 Defendants’ Amended Disclosure of Expert Witnesses 18

5/27/92 Letter from Philip Tegeler to Clerk of Court

(Superior Court) forwarding to Judge Hammer:

Motion for Extension of Time to Respond

to Defendants’ First Request for

Production Q/Q 5/27/92 ceoeveessanensvinessns

N

a

”

N

s

”

N

t

’

N

i

?

s

t

’

“

o

u

s

t

19

6/2/92 Letter from Richard Blumenthal (Attorney General

to Philip Tegeler confirming agreement re the

hourly rates for the depositions of individuals

whose identity has been disclosed to date ...... 20

6/3/92 Order of Hon. Harry Hammer 5/29/92, J. Callaghan

A/C 6/3/92, granting Motion for Extension of

Time to Respond to Defendants’ First Request for

FOr PrOQMCLION 4s s'ssnssnvsenssssevnsevonsoseenons 21

6/4/92 Letter from Marianne E. Lado to Judge Hammer &

Letter to Clerk of the Court (Superior Court)

forwarding:

Plaintiffs’ Response to Defendant’s First

Request FOr ProQuUCEiON. ccs vevvecevsosniens

W

n

”

N

t

”

N

w

s

t

”

o

w

s

w

i

’

22

6/4/92 Notice of Service of Plaintiffs’ Response to )

Defendants’ First Request for Production ...... }:. 23

6/4/92 Stipulation Regarding Procedure for Taking of )

EXDErl DEPOSIT IONS vue essnmonosssaonsssvenesnsnens y. 24

6/ /92

6/10/92

6/12/92

6/15/92

6/18/92

MILO SHEFF, et al. v. WILLIAM A. O’NEILL

Case # 2207-02 H/B #3

Contents

Letter from Richard Blumenthal (Attorney General)

to Hon. Harry Hammer enclosing:

N

a

”

a

”

a

a

un

u

t

Protective Orel & .ceosovavvoconessseneeni

Stipulation Regarding Procedure for Taking

of Expert Depositions ........ sus rivisnunives

Order Governing Depositions of Expert Witnesses

Order approving stipulation: Pleading 174.00 )

Order Governing Depositions of Expert Witnesses )

Plaintiffs’ Memorandum In Opposition to Defendants)

Motion for Order Of COMPLIANCE weeeeeeseveceenes )

Notice of Deposition of:

Robert Brewer, Douglas Rindone

Patricia Downs, Thomas E. Steahr

PAVIA ATTIOL creo vicionsn viansnecnsonsivionsicss son

Findings and Orders of the Court before Hon.

Harry Hammer, JUAGE ses vsvesensssrensvvsnsssonsos

25

26

27

29

30