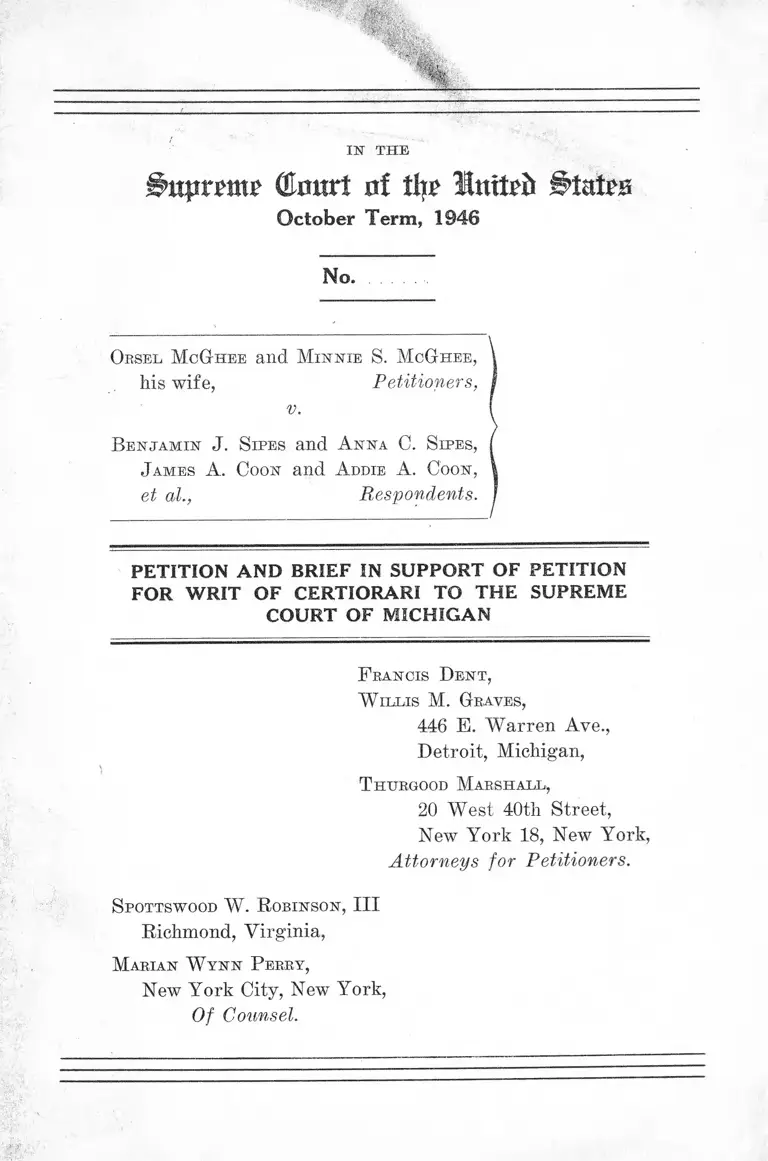

McGhee v. Sipes Petition and Brief in Support of Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1946

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McGhee v. Sipes Petition and Brief in Support of Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1946. 29449296-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e6b7ada2-8098-442c-9131-32447ac1e36d/mcghee-v-sipes-petition-and-brief-in-support-of-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme (tart of % Mnlttb States

October Term, 1946

No.

Orsel M cG hee and M in n ie S. M cG hee ,

Ms wife, Petitioners,

v.

B e n ja m in J. S ipes and A n n a C. S ipes,

J ames A . C oon and A ddie A . Coon ,

et al., Respondents.

PETITION AN D BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION

FOR W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF MICHIGAN

F rancis D e n t ,

W illis M. G raves,

446 E. Warren Ave.,

Detroit, Michigan,

T htjrgood M arshall,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York,

Attorneys for Petitioners.

S pottswood W . R obinson , III

Richmond, Virginia,

M arian W y n n P erry,

New York City, New York,

Of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

Petition for Writ of Certiorari_______________________ 1

A. Jurisdiction _____________________________ r_____ 2

B. Summary Statement of Matter Involved_____ 2

0. Questions Presented__________________________ 4

D. Beasons Belied on for Allowance of W rit______ 5

Conclusion_______________________________________ 7

Brief in Support of Petition__________________ ______ 9

Opinion of Court Below _,_______ ____________ __ 9

Jurisdiction_________________________ .____________ 9

Statement of the C ase_____________ ,_____________ 10

Errors Below Belied IJpon H e re _________________ 10

Summary of Argument ___________ ___'___________ 10

Argument:

I. Judicial Enforcement of the Agreement in Ques

tion Is Violative of the Constitution and Laws

of the United States________________________ 11

A. The Bight of a Citizen to Occupy, Use and

Enjoy His Property Is Guaranteed by the

Constitution and Laws of the United States 11

11

PAGE

B. The State, Through the Courts Below, Has

Been the Effective Agent in Depriving Peti

tioners of Their Property, and the Exercise

of Their Constitutionally Protected Rights

Therein___________________________________ 11

C. Action by a State, Through Its Judiciary,

Prohibiting or Impairing, on Account of

Race or Color, the Right of a Person to Use,

Occupy and Enjoy His Property Is Violative

of the Constitutional Guarantee of Due

Process___________________________________ 13

D. The Agreement in its Inception was Subject

to Constitutional Limitations Upon the

Power of the Courts to Enforce it__________ 17

E. The Issue Here Presented Has Never Been

Decided by This C ourt____________ :_______ 19

II. A Restriction Against the Use of Land by Mem

bers of Racial Minorities Is Contrary to Public

Policy of the United States____________________ 23

A. The Public Policy of the United States____ 23

B. The Demonstrable Consequences of Racial

Zoning by Court Enforcement of Restrictive

Covenants are Gravely Injurious to the Pub

lic Welfare _______________________________ 28

Conclusion 36

Table of Cases and Authorities Cited in Brief.

PAGE

Allen v. Oklahoma City, 175 Okla, 421, 52 F. (2d) 1054 15

American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U. S. 321 16

Bakery Drivers Local v. Wohl, 315 U. S. 769_________ 16

Bowen v. City of Atlanta, 159 Gta. 145, 125 S. E. 199._ 15

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252__________________ 16

Brinkerhoff Faris Co. v. Hill, 281 U. S. 673___________ 17

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 TJ. S. 60______11,13,14,15,17,19

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3_______________________ 14

Cantwell v. Conn., 310 U. S. 296______________________ 16

Chicago B. & 0. B. Co. v. Chicago, 166 U. S. 226_____15,16

City of Bichmond v. Deans, 37 F. (2d) 712, aff’d 281

U. S. 704 ________________________________________ 11

Clinard v. Citv of Winston-Salem, 217 N. C. 119, 6

S. E. (2d) 867 __________________________ ________ 15

Corrigan v. Buckley, 299 Fed. 899, 271 XJ. S. 323_____ 19,

20, 21, 22

Deans v. City of Bichmond, 281 TJ. S. 704____ ______ 14

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 IT. S. 339_____________________ 15

Glover v. City of Atlanta, 148 Ga. 285, 96 S. E. 562__ 15

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485_________________________ 14

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668_____________________ 11,14

Home Building & Loan Asso. v. Blaisdell, 290 U. S. 398 18

In Be Drummond Wren, 4 D. L. B. 674 (1945)________ 25

Irvine v. City of Clifton Forge, 124 Va. 781, 97 S. E.

310 _____________ ________________________________ 15

Jackson v. State, 132 Md. 311, 103 A. 910_______ _____ 15

Mooney v. Holohan, 294 TJ. S. 103____________________ 15

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 TJ. S. 86_______________ ...._____ 17

Norman v. Baltimore & O. B. Co., 294 TJ. S. 240______ 18

IV

PAGE

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45.___________________ 17

Raymond v. Chicago Traction Co., 207 U. S. 20______ 15

Scott v. McNeal, 154 U. S. 34______________________ _____ 17

Slaughter House Cases, 16 Wall 36__________________11, 24

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649_____________________ 23

Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192_________ 28

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303___________ 24

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Firemen and Engineers,

323 IT. S. 210 ____________________________________ 28

Twining v. New Jersey, 211 U. S. 78____ ___ ________ 17

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313_____________________ 15

Ward v. Maryland, 12 Wall 418____________ 11

Authorities

City of Detroit Interracial Committee, Report of

March 17, 1947____________________________ ■______ 30

Detroit Free Press, March 17, 1945__________________ 32

Detroit Housing Commission, Official Report to Mayor,

December 12, 1944 _______________________________ 32

Embree, Brown Americans (1943)__ .________________ 34

Good Neighbors, Architectural Forum, January, 1946 35

Klutznick, Philip, Public Housing Charts Its Course,

Survey Graphic, January, 1945____________________ 33

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944), Vol. 1, p. 625.... 35

Report of the Committee of the President, Conference

on Home Building, Vol. VI, pp. 45, 46 (1932)______ 28

U. S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census

Series CA-3, No. 9, October 1, 1944_______________ 29

Special Survey HO. No. 1, 1943, August 23, 1944.... 29

Population Series, CA-3, No. 9, October 1, 1944____ 30

Woofter, Negro Problem In Cities (1938)____________ 33, 34

IN TH E

Bnptmt GImtrt nf Ih? llnttrii States

October Term, 1946.

No.

Orsel M cG hee and M in n ie S. M cG h ee ,

his wife,

Petitioners,

v.

B e n ja m in J. S ipes and A n n a C. S ipes,

J ames A. C oon and A ddie A. Coon,

et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF MICHIGAN

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

Petitioners respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari

issue to review a judgment of the Supreme Court of the

State of Michigan affirming a final judgment for respon

dents and plaintiffs in the original suit in the Circuit Court

of the County of Wayne in chancery.

2

A

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Section

237 of the Judicial Code, as amended (28 U. S. Code 344

(b )).

The judgment sought to be reviewed was entered by

the Supreme Court of the State of Michigan on the 7th of

January, 1947, (R. 87) and petitioners’ motion for a re

hearing was denied on the 3rd of March, 1947 (R. 118).

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Michigan is reported

at 316 Mich. 614, and is also filed as part of the record

(R. 87).

B

Summary Statement of the Matter Involved

1. Suit and the parties thereto.

This proceeding originated as a suit in equity in the

Circuit Court for the County of Wayne, in chancery, in

the State of Michigan against the petitioners for the pur

pose of obtaining an injunction restraining the petitioners

from using or occupying property which had been pur

chased by them and which they were occupying as their

home (R. 16).

Petitioners were found by lower court to be Negroes

(R. 74). Prior to the present suit, they purchased and

became the occupants of an improved parcel of residential

property in the City of Detroit, County of Wayne, State

of Michigan, more fully described as 4626 Seebaldt Avenue

(R. 16, 19). Petitioners are the owners of record title to

the property in fee simple and occupied it as their home

3

(R. 19). In this action, the respondents sought and ob

tained a decree requiring the petitioners to move from

said property and thereafter restraining them from using

or occupying the premises and, further, restraining peti

tioners from violating a race restrictive covenant upon

such land, set forth, more fully below (R. 74, 75).

2. Theory and factual basis of the suit.

The essential facts are undisputed. On or about the

20th day of June, 1934, John C. Ferguson and his wife,

the then owners of the premises now occupied by peti

tioners, 4626 Seebaldt Avenue, executed a certain agree

ment providing in its essential parts as follows:

“ We, the undersigned, owners of the following de

scribed property:

Lot No. 52 Seebaldts Sub. of Part of Joseph Tire-

man’s Est. 1/4 Sec. 51 & 52 10 000 A T and F r ’l

Sec. 3, T 2 S, R 11 E.

for the purpose of defining, recording, and carrying

out the general plan of developing the subdivision

which has been uniformly recognized and followed,

do hereby agree that the following restriction be im

posed on our property above described, to remain in

force until January 1st, 1960— to run with the land,

and to be binding on our heirs, executors, and as

signs :

‘ This property shall not be used or occupied by any

person or persons except those of the Caucasian race’

“ It is further agreed that this restriction shall not be

effective unless at least eighty percent of the prop

erty fronting on both sides of the street in the block

where our land is located is subjected to this or a

similar restriction” (R. 63).

4

This contract was subsequently recorded at Liber 4505,

page 610, of the Register of the County of Wayne on the

7th day of September, 1935. Similar agreements were exe

cuted on forty-nine lots of property located within the sub

division within which the lot which is the subject of this

suit is located (R. 55, 56). Petitioners purchased said prop

erty on the 30th of November, 1944 from persons holding

under the said Fergusons, who executed the restriction.

Bill of Complaint herein was filed on the 30th of January,

1945.

C

Questions Presented

I

Whether judicial enforcement of a restriction against

the use of land by Negroes constitutes a violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

II

Whether agreements restricting the use of land by mem

bers of racial or religious minorities is against the public

policy of the United States.

The foregoing questions were seasonably and properly

raised in the Wayne County Circuit Court and in the

Supreme Court for the State of Michigan, and were con

sidered and decided adversely to the petitioners herein in

both of said courts. However, the opinion of the Supreme

Court of Michigan was based upon stare decisis, and stated:

“ The unsettling effect of such a determination by

this court without prior legislative action or a specific

Federal mandate would be, in our judgment, im

proper (R. 96).

5

D

Reasons Relied on for A llow ance o f W rit

1. Judicial enforcement of the agreement in question is

violative of the Constitution and laws of the United States.

(a) The right of a citizen to use, occupy and enjoy his

property is guaranteed by the Constitution and laws of the

United States.

United States Constitution, Article IV, Sec. 2,

Fifth Amendment, Fourteenth Amendment;

Ward v. Maryland, 12 Wall. 418;

The Slaughter House Cases, 16 Wall. 36;

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60.

(b) The State, through the courts below, has been the

effective agent in depriving petitioners of their property,

and the exercise of constitutionally protected rights therein.

(c) Action by a state, through its judiciary, prohibiting

or impairing, on account of race or color, the right of a per

son to use, occupy and enjoy his property is violative of the

constitutional guarantee of due process.

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339;

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313;

Chicago, B. <& Q. R. Co. v, Chicago, 166 U. S. 226;

Raymond v. Chicago Traction Co., 207 U. S 20;

6

Mooney v, Holohan, 294 U. S. 103;

American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U. 8.

321.

(d) The agreement in its inception was subject to con

stitutional limitations upon the power of the courts to en

force it.

Norman v. B. & 0. R. Co., 294 U. S. 240;

Home Building & Loan Assoc, v. Blaisdell, 290

IT. S. 398.

(e) The issue here presented has never been decided by

this Court.

Corrigan, v. Buckley, 271 U. S. 323;

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649.

2. A restriction against the use of land by members of

a racial minority is contrary to the public policy of the

United States.

Constitution of the United States, Thirteenth,

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments;

The Slaughter House Cases, supra;

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303;

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Firemen, etc., 323

U. S. 210;

Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192;

In re Drummond Wren, 4 I). L. R. 674;

7

United Nations Charter

Preamble

Articles 55 and 56.

Sociologists, experts in city planning, crime prevention

and race relations have established that limitations upon

the use of land for living space by members of racial or

religious minorities constitute one of the gravest dangers

to democratic society which we face in America, and in the

light of these dangers the courts must consider and weigh

the effects of their use of the injunctive power to extend

such limitations in the face of the resulting damage to the

whole of society.

In support of the foregoing grounds of application, peti

tioners submit herewith the accompanying brief setting

forth in detail the pertinent facts and argument applicable

thereto.

Petitioners further state that this application is filed

in good faith and not for purposes of delay.

W herefore, it is respectfully submitted that this peti

tion for a writ of certiorari to review the judgment of the

Supreme Court of the State of Michigan be granted.

Conclusion

F rancis D en t ,

W illis M. Graves,

446 E. Warren Ave.,

Detroit, Michigan.

S pottswood W. R obinson , III

Richmond Virginia, T htjrgood M arshall .

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York,M arian W y n n P erry,

New York City, New York,

Of Counsel.

Attorneys for Petitioners.

IN' T H E

tour! o! % Infteh g>tate

October Term, 1946.

No.

Orsel M cG hee and M in n ie 8 . M cG h ee ,

his wife,

Petitioners,

v.

B e n ja m in J. S ipes and A n n a C. S ipes,

J ames A. C oon and A ddie A . Coon,

et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR W R IT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF MICHIGAN

Opinion of Court Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of the State of

Michigan is reported at 316 Mich. 614.

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of the Court is invoked under Section

237 of the Judicial Code, as amended, (28 U. S. Code 344

(b)).

The judgment sought to be reviewed was entered by

the Supreme Court of the State of Michigan on the 7th of

January, 1947 (R. 87) and application for rehearing was

denied on the 3rd of March, 1947 (R. 118).

9

10

Statement o f the Case

The statement of the case and a statement of the salient

facts from the record appear in the accompanying petition

for certiorari.

Errors Below Relied Upon Here

I. The Judicial Arm o f the Government has Imposed Racial

Restrictions in V iolation o f the Constitution and Laws o f

the United States.

II. The Restriction Against the Use o f Land by Minorities

Involved in This Case was Held not to Be Contrary to

Public Policy.

Summary of Argument

I. Judicial Enforcem ent o f the Agreem ent in Question is

V iolative o f the Constitution and Laws o f the United

States.

A . The Right o f a Citizen to O ccupy, Use and Enjoy

His Property is Guaranteed by the Constitution and

Laws o f the United States.

B. The State, Through the Courts Below, Has Been

The Effective Agent in Depriving Petitioners o f Their

Property, A nd The Exercise o f Their Constitution

ally Protected Rights Therein.

C. Action by a State, Through Its Judiciary, Prohibiting

or Impairing, Qn A ccount o f Race or Color, The

Right o f a Person to Use, Occupy, and Enjoy His

Property Is Violative o f The Constitutional Guarantee

o f Due Process.

D. The Agreem ent In Its Inception W as Subject To Con

stitutional Limitations Upon The Power o f The Courts

to Enforce It.

E. The Issue Here Presented Has Never Been Decided

By This Court.

II. A Restriction Against the Use o f Land by Members o f

Racial Minorities is Contrary to Public Policy o f the

United States.

11

A R G U M E N T

I

Judicial Enforcement of the Agreement in Ques

tion is Violative of the Constitution and Laws of

United States.

A. The Right of a Citizen to Occupy, Use and Enjoy

His Property is Guaranteed by the Constitution

and Laws of the United States.

Petitioners were and still are the owners in fee simple

of the premises in question. The decree complained of

deprives them of their right to occupy, use and enjoy their

property.

The significant protective bases of the rights thus de

nied these petitioners are Article IV, Section 2, and the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution of

the United States, and Congressional legislation enacted

pursuant thereto.

Whether privileges inherent in state or federal citizen

ship,1 they are guaranteed safety from attack by state

governments.2

B. The State, Through the Courts Below, Has Been

the Effective Agent in Depriving Petitioners of

Their Property, and the Exercise of Their Con

stitutionally Protected Rights Therein.

When, as here, a State court enforces a racial covenant,

it is the action of the State, and not the action of individ

1 See Ward v. Maryland, 12 Wall. 418, 430; The Slaughter House

cases, 16 Wall. 36.

2 Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60; Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S.

668; City of Richmond v. Deans (C. C. A. 4 ), 37 F. (2d) 712, aff’d

281 U. S. 704.

12

uals, which deprives the Negro occupant of his right to

enjoy his property.

The creation, modification and destruction of rights in

property are controlled, not by individual action itself, but

by the legal consequences which the State attaches to it.

I f a Negro is privately persuaded to refrain from occupy

ing or purchasing property by reason of the fact that such

a covenant exists, or if each party to the restrictive agree

ment, by reason of the restriction or otherwise, refuses to

sell to a Negro, it is the action of the parties which effec

tively keeps him out. The same is true as to other private

sanctions which they may be able to apply without resort

to governmental forces.

But when private sanctions are ineffective to compel

obedience to the covenant, and it is necessary to appeal to

the courts for its enforcement, individual action ceases and

governmental action begins. It is obvious that in a situ

ation where, as here, a Negro purchases and enters into the

possession of property upon which there is a racial restric

tion, he has lost nothing and has been deprived of nothing,

by reason merely of the making of the restrictive agree

ment or the private compulsions of the parties thereto;

this is best evidenced by the fact that petitioners are still

in occupancy and that the proponents of the covenant find

it necessary to go into court to oust them. But when the

Court commands him to remove from the premises, an arm

of the State government has effected a deprivation.

The decree has all the force of a statute. It has behind

it the sovereign power. It is not the respondent, but the

sovereignty, speaking through the Court that has issued

a mandate to the petitioners enjoining them from occupy

ing, using or enjoying their property.

13

C. Action by a State, Through Its Judiciary, Pro

hibiting or Impairing, on A ccount o f Race or

Color the Right o f a Person to Use, O ccupy and

Enjoy His Property Is Violative o f the Constitu

tional Guarantee o f Due Process.

In Buchanan v. Warley,3 this Court firmly established

that there is a general right afforded all persons alike by

the constitutional guaranty of due process, to use, occupy

and enjoy real property without restriction by state action

predicated upon race or color. In that case, the Court was

faced with an ordinance of the City of Louisville, Ken

tucky, providing that colored persons could not occupy

houses in blocks where the greater number of houses were

occupied by white persons, and which contained the same

prohibitions as to white persons in blocks where the greater

number of houses were occupied by colored persons. Bu

chanan, the plaintiff, brought an action against Warley, a

Negro, for the specific performance of a contract for the

sale of the former’s lot to the latter. Warley defended

upon a provision in his contract excusing him from per

formance in the event that he should not have, under the

laws of the state and city, the right to occupy the property,

and contended that the ordinance prevented his occupancy

of the subject matter of the contract. It was held, how

ever, that the ordinance was unconstitutional as violative

of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Court said:

“ The concrete question here is: May the occu

pancy, and, necessarily, the purchase and sale of

property of which occupancy is an incident, be in

hibited by the states, or by one of its municipalities,

solely because of the color of the proposed occupant

of the premises ? * * * 4

3 245 U. S. 60.

4 245 U. S. 75.

14

“ Colored persons are citizens of the United

States and have the right to purchase property and

enjoy and use the same without laws discriminating

against them solely on account of color. Hall v.

DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485, 508. These enactments did

not deal with the social rights of men, but with those

fundamental rights in property which it was in

tended to secure upon the same terms to citizens of

every race and color. Civil Eights Cases, 109 U. S.

3, 22. The Fourteenth Amendment and these stat

utes enacted in furtherance of its purpose operate

to qualify and entitle a colored man to acquire prop

erty without state legislation discriminating against

him solely because of color. * * * 5 6 7

“ We think this attempt to prevent the alienation

of the property in question to a person of color was

not a legitimate exercise of the police power of the

state, and is in direct violation of the fundamental

law enacted in the 14th Amendment of the Constitu

tion preventing State interference with property

rights except by due process of law. * * * ” e

In Harm,on v. Tyler,'' this Court was again faced with

an attempt to accomplish substantially the same end by

an ordinance prohibiting the sale or lease of property to

Negroes in any “ community or portion of the city * * *

except on the written consent of a majority of the persons

of the opposite race inhabiting such community or portion

of the city.” This ordinance likewise was held to be in

valid. Still later, legislation effecting a residential segre

gation predicated upon the intermarriage interdiction was

held by this Court to be bad.8 Substantially all of the State

and lower Federal Courts since considering the eonstitu-

5 245 U. S. 78-79.

6 245 U. S. 82.

7 273 U. S. 668.

8 Deans v. City of Richmond, 281 U. S. 704.

15

tional validity of such legislative enactments have reached

the same conclusion.9

For the reasons considered in Buchanan v. Warley, it

would have been beyond the legislative power of the State

to have enacted a law seeking the accomplishment of the

end sought to be attained by the covenant here involved,

or by a law providing that a covenant in the precise terms

of that involved in the present case should be enforceable

in its courts. It is inconceivable that, so long as the legis

lature refrains from passing such a law, a State court may,

by its decree, compel the specific observance of such cove

nants and thus afford governmental sanction to a device

which it was not within the competency of its legislative

branch to authorize. Yet the immediate consequence of

the decree now under consideration is to bring about that

which the legislative and executive branches of the State

are powerless to accomplish.

It is clear that such property rights as are protected

by the constitutional guaranty of due process against im

pairment by the legislature are equally protected against

impairment by the judiciary. It is now established that

the prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment apply to all

conceivable forms of State action, including that by its

courts.10 Such action is found when a court predicates its

9 Irvine v. City of Clifton Forge, 124 Va. 781, 97 S. E. 310;

Glover v. City of Atlanta, 14'8 Ga. 285, 96 S. E. 562; Jackson v. State,

132 Md. 311, 103 A. 910; Bowen v. City of Atlanta, 159 Ga. 145,

125 S. E. 199; Clinard v. City of Winston-Salem, 217 N. C. 119, 6

S. E. 2d 867; Allen v. Oklahoma City, 175 Okla. 421, 52 P. 2d 1054;

and see the cases cited, supra. It will be noted that in the Allen case,

the ordinance was sought to be aided by an exercise of the executive

power.

10 E x Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339; Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S.

313; Chicago, B. & Q. R. Co. v. Chicago, 166 U. S. 226; Raymond

v. Chicago Traction Co., 207 U. S. 20; Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U. S.

103.

16

judgment upon a rule of substantive law developed in the

common law, or judge-made law, of a State. Such a rule,

so made and applied, is as much the product of State action

and is as much subject to the same tests of validity, as if

made by that other form of State action, enactment by the

legislature. This Court has had frequent occasion to apply

this principle. Thus, where a State court grants an injunc

tion against peaceful picketing on the ground that such

conduct is forbidden by the common law of the State, its

action infringes the Fourteenth Amendment to the same

extent as would a statute in similar provision which

abridges the freedom of speech which the Fourteenth

Amendment commands all States to respect.11 Likewise,

where an individual is convicted in the court of a State of

inciting a breach of the peace, a criminal offense under

the judge-made law of the State, its action may be con

demned on the same grounds.12 In similar fashion, the con

stitutional guaranties of free speech may be impinged upon

by a State court judgment inflicting a contempt sentence

under its version of the common law of the State with

respect to punishable contempts of court.13 And, where a

judgment of a State court accomplishes a taking of private

property without just compensation, the State has produced

a result forbidden by the due process clause.14 The large

body of cases holding that the State has acted where its

courts have given effect to a rule of procedure held by it

to be a part of the common law of the State, but in effect

bringing about a denial of constitutional rights, also serves

to emphasize the role of the court as an arm of the State

11 American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U. S. 321; Bakery

Drivers Local v. Wohl, 315 U. S. 769.

12 Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296.

13 Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252.

14 Chicago, B. & Q. R. Co. v. Chicago, 166 U. S. 226.

17

and the consequent production of an unconstitutional re

sult.15

The mere fact that in Buchanan v. Warley, the forbid

den state action was initiated by the legislative department,

while, in the instant case, the action was initially individual

in character, makes no difference once the judicial arm of

the State has acted. There can be no difference between

State action predicated upon prior individual action and

that which is not predicated thereon—the Fourteenth

Amendment prohibits both. When the Court acts, it action

is entirely independent of that of the litigants, and where

private action ceases and court action commences, the per

mission of the one ends and the prohibition of the other

begins.

D. The Agreement in its Inception was Subject to

Constitutional Limitations Upon the Power of the

Courts to Enforce it.

The Supreme Court of Michigan erroneously assumed

that when private individuals enter into a restrictive agree

ment, the Court is obligated to enforce the same. But the

courts cannot avoid responsibility under the Fourteenth

Amendment by the1 ‘ convenient apologetics ’ ’ of an obligation

which they cannot constitutionally discharge. There is no

absolute freedom of contract in the sense that judicial en

forcement of an agreement is automatically forthcoming.

The right to contract is subject to a variety of restrictions,

of which the usury laws, gambling laws, Sunday laws, the

Sherman Anti-Trust Act, peonage sections of the Criminal

Code, the National Labor Relations Act and prevention of

15 Twining v. New Jersey, 211 U. S. 78; Brinkerhoff-Faris Co. v.

Hill, 281 U. S. 673; Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45; Moore v.

Dempsey, 261 U. S. 86; Scott v. McNeal, 154 U. S. 34.

18

unfair competition by the Federal Trade Commission, are

illustrative. It is likewise clear that where, by reason of

constitutional prohibitions, a court is prevented from en

forcing an agreement privately made, there can be no claim

that there has been an unjustified interference with liberty

of contract. In such a case every individually-made contract

from its inception is subject to the infirmity that judicial

enforcement cannot be obtained if, so to enforce it, a vio

lation of constitutionally protected rights will follow.

The right of an individual to make a contract is subject

to the paramount authority vested in government by the

Federal Constitution. Thus, in Norman v. Baltimore & 0.

R. Co.,16 it was held that the joint resolution abrogating the

Gold Clause stipulation in money contract obligations could

be applied to pre-existing private agreements, since all in

dividual agreements are made subject to the exercise of the

Federal power to regulate the value of money.

Again, in Home Building and Loan Association v. Blais-

dell,17 it was held that a state statute might, in spite of the

prohibitions in the Federal Constitution against state im

pairment of the obligations of a contract, be applied in such

manner that the previously made contract would be im

paired, since all contracts made between individuals are

subject to the paramount authority of the State to enact

laws validly within its police power.

It is the duty of the courts to enforce contracts so long

as the court may do so consistently with the supreme law

of the land. If, however, a court lends its aid to the en

forcement of a segregation restriction, with the result that

a Negro is deprived of his constitutional right to occupy

16 294 U. S. 240.

17 290 U. S. 398.

19

property, there is an infringement of the constitutional

guaranties of due process within the holding of this Court

in Buchanan v. Warley.

The contract involved in this case must be understood

as having been made subject to existing constitutional limi

tations upon the authority of the state to enforce it, and al

though the declination of the Court to enforce the agree

ment effectively prevents it from ripening in the manner

desired by the contracting parties, its action could not be

considered as the denial to them of any constitutionally

protected rights.

E. The Issue Here Presented Has Never Been De

cided by This Court.

Judicial enforceability of racial restrictive covenants has

frequently been assumed to follow from the decision of this

Court in the case of Corrigan v. Buckley.18 A reexamina

tion of that case makes it apparent that the issue here pre

sented was neither presented nor decided there.

About 30 white persons, including the plaintiff and

defendant Corrigan, who were the owners of 25 parcels of

land, executed and recorded an indenture in which they

mutually covenanted that no part of the properties covered

would ever be sold to or occupied by Negroes. A year later,

defendant Corrigan entered into a contract to sell to defen

dant Curtis, a Negro, a house and lot situated within the

restricted area. Plaintiff thereupon brought suit to enjoin

the sale to and occupancy by defendant Curtis. Both de

fendants moved to dismiss the bill upon grounds which did

18 55 App. D. C. 30, 299 Fed. 899; appeal denied 271 U. S. 323.

20

not question the constitutional propriety of judicial en

forcement of the covenant.19 The motions were denied and

an appeal to the Court o f Appeals for the District of Co

lumbia 20 taken, where the issue was stated as follows:

“ * * * The sole issue is the power of a number of

landowners to execute and record a covenant running

with the land, by which they bind themselves, their

heirs and assigns, during a period of 21 years, to

prevent any of the land described in the covenant

from being sold, leased to, or occupied by Negroes.”

19 Defendant Corrigan moved to dismiss the bill on the grounds that

the “ indenture or covenant made the basis of said bill” is (1 ) “ void in

that the same is contrary to and in violation of the Constitution of the

United States,” and (2 ) “ is void in that the same is contrary to public

policy.” Defendant Curtis moved to dismiss the bill on the grounds

that it appeared therein that the indenture or covenant “ is void, in

that it attempted to deprive the defendant, the said Helen Curtis, and

others of property, without due process of law ; abridges the privilege

and immunities of citizens of the United States, including the defen

dant, Helen Curtis, and other persons within this jurisdiction (and

denies them) the equal protection of the law, and therefore, is for

bidden by the Constitution of the United States, and especially by the

Fifth, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth Amendments thereof, and the Laws

enacted in aid and under the sanction of the said Thirteenth and Four

teenth Amendments.” From the opinion of the Supreme Court of

the United States, 271 U. S. 328-329.

20 5 5 App. D. C. 30, 299 Fed. 899.

21

Following an affirmance of the decree, an appeal to this

Court21 was taken under the provisions of Section 250 of

the Judicial Code. This Court stated the issue as follows:22

“ Under the pleadings in the present case the

only constitutional question involved was that aris

ing under the assertions in the motions to dismiss

that the indenture or covenant which is the basis of

the bill is ‘void’ in that it is contrary to and for

bidden by the 5th, 13th and 14th Amendments. * * * ”

In dismissing the appeal for want of jurisdiction, this

Court said:23

“ And, while it was further urged in this Court

that the decrees of the courts below in themselves

deprived the defendants of their liberty and prop

erty without due process of law, in violation of the

5th and 14th Amendments, this contention likewise

cannot serve as a jurisdictional basis for the appeal.

Assuming that such a contention, if of a substantial

character, might have constituted ground for an

appeal under paragraph 3 of the Code provision, it

was not raised by the petition for the appeal or by

any assignment of error, either in the Court of Ap

peals or in this Court; and it likewise is lacking in

substance. * * *

“ Hence, without a consideration of these ques

tions, the appeal must be, and is, dismissed for want

of jurisdiction.” (Italics supplied.)

21 271 U. S. 323.

22 271 U. S. 329-330.

23 271 U. S. 331-332.

22

It must be concluded, therefore, that the constitution

ality of judicial enforcement of such an agreement was not

decided in Corrigan v. Buckley.2*

While the Corrigan decision contains an intimation by

way of dictum that no constitutional question is presented

2* Close examination of the opinion reveals that the Court actually

decided only four propositions :

(1 ) That since the Fourteenth Amendment, by its terms, directs

its prohibitions only to state action, it was not violated by the creation

of the covenant. Thus, defendants’ motions to dismiss on this ground

did not raise any constitutional question, and therefore afforded no

basis for an appellate review in the Supreme Court as a matter of right.

(2 ) That Sections 1977 and 1978 (U . S. C., secs. 41 and 42) of

the Revised Statutes neither render the covenant void nor raise any

substantial federal question, but merely give all citizens of the United

States the same right in every state and territory to make and enforce

contracts, to purchase, lease and hold real property, etc., as is enjoyed

by white citizens, and this, only against impairment by state action.

Hence, individual action consisting in entering into a restrictive agree

ment is not forbidden.

(3 ) That the contention that the covenant was against public policy,

and therefore void, is purely a question of local law, and so could not

afford a substantial basis for an appeal to the Supreme Court.

(4 ) That the objection that the entry of the decrees in the lower

courts enforcing the covenant constituted state action in violation of

the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, was not raised in the petition

for appeal or by assignment of error either in the Court of Appeals or

in the Supreme Court, and was therefore not before the Court for

decision.

In recognition of this, the Supreme Court of Michigan in the instant

case considered Corrigan v. Buckley inapplicable, saying:

“ It is argued that the restriction in question violates the 14th

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Appellees

say that this argument was answered in Corrigan v. Buckley, 271

U. S. 323. W e do not so read the Corrigan case, but rather that

the decision there turned on the inapplicability of the equal pro

tection clause of the 14th Amendment to the District of Columbia,

and that the appeal was dismissed for want of jurisdiction. 316

Mich. 614. (The certified copy of the opinion and the opinion as

reported at 25 N. W . (2d) 638, and as filed reads as quoted. In the

Advance Michigan reports, the second sentence reads, ‘W e so read

the Corrigan Case, although that decision partly turned . . . . ’ ) . ”

23

by the facts of that case, it is to be remembered that this

Court was not then committed to the doctrine that common

law determinations of courts can constitute reviewable

violations of the due process clause. But the Court is now

committed to that doctrine.25

This Court has additional reason for reinterpreting its

decision in the Corrigan ease.

“ In constitutional questions, where correction

depends upon amendment and not upon legislative

action this Court throughout its history has freely

exercised its power to re-examine the basis of its

constitutional decisions. This has long been ac

cepted practice, and this practice has continued to

this day. This is particularly true when the decision

believed erroneous is the application of a consti

tutional principle rather than an interpretation of

the Constitution to extract the principle itself.”

(Emphasis supplied.)26

II

A Restriction Against the Use of Land by

Members of Racial Minorities Is Contrary to

Public Policy of the United States.

A. The Public Policy of the United States.

Fundamental national policies expressed in the Consti

tution and laws of the United States are offended by the

restrictive agreement involved in the present case. The

constitutionality of judicial enforcement of such restric

tions is challenged in another section of this brief. But it

is clear that even before the issue of constitutionality is

25 Argument, Part IC.

26 Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649, 665, 666.

24

reached, the constitutional prohibition against legislation

must at least reflect national policy against the abuse of

private power to accomplish the same result.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution was

adopted to abolish slavery and the Fourteenth and F if

teenth Amendments to abolish the badges of servitude

which remained in the treatment of the recently freed slave.

These were the first steps in creating a public policy, and

were so recognized by this Court in 1872 when the memory

of the struggle for the adoption of the amendments was

still alive.

” . . . no one can fail to be impressed with the

one pervading purpose found in them all, lying at

the foundation of each, and without which none of

them would have been even suggested; we mean the

freedom of the slave race, the security and firm

establishment of that freedom, and the protection of

the newly made freeman and citizen from the op

pressions of those who had formeidy exercised un

limited dominion over him.” 27

” . . . The words of the Amendment, it is true,

are prohibitory, but they contain a necessary impli

cation of a positive immunity, or right, most valu

able to the colored race— the right to exemption

from unfriendly legislation against them distinc

tively as colored; exemption from legal discrimina

tions, implying inferiority in civil society, lessening

the security of their enjoyment of the rights which

others enjoy, and discriminations which are steps

toward reducing them to the condition of a subject

race.” 28

At the close of the Second World War, which was so

largely waged for the principles of racial and religious

equality as enunciated in the Atlantic Charter, the United

27 Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. 36, 71.

28 Strauder v. W est Virginia■, 100 U. S. 303, 308.

25

States solemnly dedicated itself, with the other members

of the United Nations, to promote universal respect for

the observance of “ human rights and fundamental free

doms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language

or religion,” (United Nations Charter, Articles 55 and 56.)

The preamble of the Charter of the United Nations con

tains the following statement:

“ We, the people of the United Nations, deter

mined to save succeeding generations from the

scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has

brought untold sorrow to mankind, and to reaffirm

faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity

and worth of the human person, in the equal rights

of men and women and of nations large and small

. . . and for these ends to practice tolerance and

live together in peace with one another as good

neighbors . . . ”

Such a dedication by treaty on the part of the United

States, ratified by the Senate, has deepened and reinforced,

the previous national public policy against racial and re

ligious discrimination at law.

Ample precedent for the adoption of the view here advo

cated is supplied by the recent decision of a Canadian

Court,29 which involved an application of the owner of

certain registered lands to have declared as invalid a re

strictive covenant assumed by him when he purchased these

lands, and which he agreed to exact from his assigns. The

restriction was:

Land shall not be sold to Jews or persons of objec

tionable nationality.

The Court, after considering numerous relevant sources

(including the San Francisco Charter, speeches of Presi- 28

28 In re Drummond Wren (1945), 4 D. L. R. 674.

26

dent Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and General Charles de

Gaulle, and the Constitution of the Union of Soviet Socialist

Republics), held that the restriction was void, saying:

“ How far this is obnoxious to public policy can

only be ascertained by projecting the coverage of the

covenant with respect both to the classes of persons

whom it may adversely affect, and to the lots or sub

divisions of land to which it may be attached. So

considered, the consequences of judicial approbation

of such a covenant are portentous. I f sale of a piece

of land can be prohibited to Jews, it can equally be

prohibited to Protestants, Catholics or other groups

or denominations. If the sale of one piece of land

can be so prohibited, the sale of other pieces of land

can likewise be prohibited. In my opinion, nothing

could be more calculated to create or deepen divisions

between existing religious and ethnic groups in this

province, or in this country, than the sanction of a

method of land transfer which would permit the

segregation and confinement of particular groups to

particular business or residential areas, or con

versely, would exclude particular groups from par

ticular business or residential areas. The unlikeli

hood of such a policy as a legislative measure is evi

dent from the contrary intention of the recently-

enacted Racial Discrimination Act, and the judicial

branch of government must take full cognizance of

such factors.

“ Ontario, and Canada too, may well be termed a

province, and a country, of minorities in regard to

the religious and ethnic groups which live therein.

It appears to me to be a moral duty, at least, to

lend aid to all forces of cohesion, and similarly to

repel all fissiparous tendencies which would imperil

national unity. The common law courts have by their

actions over the years, obviated the need for rigid

constitutional guarantees in our policy by their wise

use of the doctrine of public policy as an active

agent in the promotion of the public weal. While

27

courts and eminent judges have, in view of the powers

of our legislatures, warned against inventing new

heads of public policy, I do not conceive that I would

be breaking new- ground -were I to hold the restrictive

covenant impugned in this proceeding to be void as

against public policy. Rather would I be applying

well-recognized principles of public policy to a set

of facts requiring their invocation in the interest of

the public good.

“ That the restrictive covenant in this case is di

rected in the first place against Jews lends poignancy

to the matter when one considers that anti-semitism

has been a weapon in the hands of our recently-

defeated enemies, and the scourge of the world. But

this feature of the case does not require innovation

in legal principle to strike down the covenant; it

merely makes it more appropriate to apply existing

principles. If the common law of treason encom

passes the stirring up of hatred between different

classes of His Majesty’s subjects, the common law

of public policy is surely adequate to void the restric

tive covenant which is here attacked.

“ My conclusion therefore is that the covenant is

void because offensive to the public policy of this

jurisdiction. This conclusion is reinforced, if rein

forcement is necessary, by the wide official acceptance

of international policies and declarations frowning

on the type of discrimination which the covenant

would seem to perpetuate.”

In their effort to rise from slavery to equality with their

fellow men, colored citizens are everywhere met by the

effort to keep them down, and to deny them that equal

opportunity which the Constitution secures to all. If they

can be forbidden to live on their own land by an instru

mentality of the government, they can be forbidden to work

at their own trade. Yet this Court has most recently ex

tended its protection to Negro workers against use of

28

government power to exclude them from their trade.30

Without protection against such judicial action to imple

ment private agreements, the prejudice, against which the

war amendments were framed to defend the colored people,

triumphs over them, and the amendments themselves be

come dead letters—as do the solemn obligations of the

United Nations Charter.

B. The Demonstrable Consequences o f Racial Zoning

by Court Enforcement o f Restrictive Covenants

are Gravely Injurious to the Public W elfare.

Residential segregation, which is sought to be main

tained by court enforcement of the race restrictive covenant

before this Court, “ has kept the Negro occupied sections

of cities throughout the country fatally unwholesome places,

a menace to the health, morals and general decency of cities,

and plague spots for race exploitation, friction and riots!”

Report of the Committee on Negro Housing of the Presi

dent, Conference on Home Building, Yol. VI, pp. 45, 46

(1932).

The extent of overcrowding resulting from the enforced

segregation of Negro residents is daily increasing. The

United States Census of 1940 examines the characteristics

of 19 million urban dwellings. The census classifies a dwell

ing as overcrowded if it is occupied by more than IV2

persons per room. On this basis 8 percent of the units

occupied by whites in the nation are classified in the 1940

census as overcrowded, while 25 percent of those occupied

by non-whites are so classified. In Baltimore, Maryland,

Negroes comprise 20 percent of the population yet are

30 See Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Firemen and Engineers, 323 U. S.

210, and Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192.

29

constricted in 2 percent of the residential areas. In the

Negro occupied second and third wards of Chicago, the

population density is 90,000 per square mile, exceeding even

the notorious overcrowding of Calcutta.

Census figures show that 8 percent of the non-white

residents of the Detroit-Willow Run Area lived at a density

in excess of 1% persons per room, while only 2.3 percent

of the white residents were classified as overcrowded in the

census of 1940.31

The critical lack of housing facilities in Michigan’s non

white population is emphasized by the following quotation

from another census study of the Detroit Metropolitan

District.

“ Vacancy rates were generally lower in Negro

sections than in white sections. The gross vacancy

rate among dwelling units for Negro occupancy was

0.4 percent and among those for white occupancy 0.8

percent.

“ Habitable vacancies represented about seven

eighths of the unoccupied dwellings intended for

wrhite occupants and one half of those for Negro

occupants.

“ Crowded dwelling units—those housing more

than 1% persons a room—made up 1.3 percent of

the dwellings in white neighborhoods and 7.4 percent

of the dwellings in Negro neighborhoods. These units

[Negro housing] had only one percent of all the

entire area but were occupied by three percent of its

population.” (U. S. Department of Commerce, Bu

reau of Census, Special Survey H. O. No. 143, August

23, 1944.)

31 U. S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of Census, Series C. A . 3, No. 9,

Oct. 1, 1944.

30

The overcrowding of the entire community during the

period from 1940 to 1944 can he emphasized by the growth

of the Detroit Metropolitan District’s population from

2,295,867 in 1940 to 2,455,035 in 1944. During the same

period the non-w7hite population in the Metropolitan area

increased from 171,877 to 250,195 (U. S. Department of

Commerce, Bureau of Census, Population Series C. A. 3

No. 9, October 1, 1944).

According to the Bureau of Census, the non-white popu

lation of Detroit itself increased from 150,790 in 1940 to

213,345 in June of 1944, a percentage increase of 41.5 per

cent.

The City of Detroit Interracial Committee has recently

completed a study of its work for the calendar year 1946,

released on March 17, 1947, based upon which it has issued

a statement of policy from which the following quotation is

taken:

“ Housing

Every informed person in Detroit knows of the

acute housing shortage existing not only locally but

throughout the country. This shortage, which af

fects all people, is felt especially by veterans and the

younger married group. The already serious prob

lem is further complicated for the Negro share of the

population, however, by the existence of certain ob

stacles to suitable housing over and above those en

countered by other citizens. While other minority

groups may have special problems, it is against

Negroes that the principal discriminatory practices

are most prevalent.

“ The City of Detroit Interracial Committee feels

impelled to point out certain of these practices and

to state what it believes to be sound principles in

relation thereto.

31

“ It is a fundamental principle in this country that

all governmental activities and services and all pri

vate business should be conducted without discrim

ination on account of color, national origin or reli

gious belief. The facts are, however, that this prin

ciple is constantly disregarded in the matter of hous

ing by both government and private individuals.

“ The following discriminatory practices in resi

dential housing activities have been employed in De

troit and elsewhere:

1. Covenants restricting occupancy based on race

are imposed on residential property by developers or

groups of owners.

2. In the absence of such covenants, owners or

occupiers of residential property by threats or acts

of violence attempt to prevent occupancy of homes in

their vicinity by persons of another race, creed or

color.

3. Lending agencies reject legitimate loans be

cause the borrower is of a race other than that estab

lished as the pattern of the neighborhood.

4. Real estate dealers, by agreement and a ‘ Code

of Ethics’, attempt to prevent occupancy by persons

because of race, color or creed, and government

agencies approve such practices.

5. In the redevelopment of blighted areas and in

providing public housing, government agencies have

recognized, approved and fortified such discrimina

tory practices.

“ The chief sufferers from those practices are the

Negro people. Housing for Negroes is utterly in

adequate, Negroes are forced to live in overcrowded,

substandard houses, and these conditions foster

disease, delinquency and civic irresponsibility. A

free market in housing and in land for housing does

not exist. The home building industry and the deal

ers in homes seem to assume that the Negro popula-

32

tion can be housed in dwellings abandoned by whites,

which is clearly not the case. They appear to disre

gard the fact that many Negroes are financially able

to pay for much better homes than are generally

available to them and the fact that the ‘ hand-me-

down’ houses of whites are not sufficient in number

to fill the demand for Negro housing. Opportunities

for expansion to vacant land are almost completely

shut off to Negroes. The restrictive practices re

ferred to above apply most effectively to vacant or

thinly developed areas of the City and suburbs.”

The Detroit Housing Commission arrived at the conclu

sion that the situation within the City of Detroit is such that

the only solution for the Negro housing problem is in the

opening of new unrestricted areas.82

The creation and growth of Negro slum areas with re

sulting high mortality, disease, delinquency and other social

evils, have been due in large measure to the existence of re

strictive covenants against Negroes which have prevented

the normal development of Negro community life. As

stated by Mr. James M. Haswell, Staff Writer for the De

troit Free Press on March 17, 1945 in a special feature

article dealing with the Detroit housing situation:

“ No substantial migration possible under pres

ent restriction patterns.

“ Nobody knows how many hundreds of restrictive

covenants and neighborhood agreements there are

in Detroit binding property owners not to permit

Negro occupancy. The number has increased greatly

in response to the Negro search for new residence

areas. There are said to be 150 associations of prop

erty owners promoting these agreements.”

To the same effect is the comment of the Commissioner,

Federal Public Housing Authority, Philip M. Klutznick, in 32

32 Detroit Housing, Official Report to Mayor, December 12, 1944.

33

Ms article, Public Housing Charts Its Course, published in

Survey Graphic for January, 1945:

“ But the minority housing problem is not one of

buildings alone. More than anything else it is a mat

ter of finding space in which to put the buildings.

Large groups of these people are being forced to

live in tight pockets of slum areas where they in

crease at their own peril; they are denied the op

portunity to spread out into new areas in the search

for decent living.

“ The opening of new areas of living to all minor

ity groups is a community problem. And it is one of

national concern. ’ ’

This is not a new situation, but it is becoming more ag

gravated from year to year. One of the most discerning

writers in this field clearly pointed out what was happen

ing and its social dangers:

‘ * Congestion comes about largely from conditions

over which the Negroes have little control. They are

crowded into segregated neighborhoods, are obliged

to go there and nowhere else, and are subjected to

vicious exploitation. Overcrowding saps the vitality

and the moral vigor of those in the dense neighbor

hoods. The environment then, rather than hereditary

traits, is a strong factor in increasing death-rates

and moral disorders. Since the cost of sickness,

death, immorality and crime is in part borne by

municipal appropriations to hospitals, jails and

courts, and in part by employers’ losses through ab

sence of employees, the entire community pays for

conditions from which the exploiters of real estate

profit.” 33

It is also widely recognized that these anti-social cove

nants are not characteristically the spontaneous product of

88 Woofter, Negro Problem In Cities (1938), at page 95.

34

the community will but rather result from the pressures and

calculated action of those who seek to exploit for their own

gain residential segregation and its consequences.

“ The riots of Chicago were preceded by the or

ganization of a number of these associations (neigh

borhood protective associations); and an excellent

report on their workings is to be found in The Negro

in Chicago, the report of the Chicago Race Commis

sion. The endeavor of such organizations is to

pledge the property holders of the neighborhood not

to sell or rent to Negroes, and to use all the possible

pressures of boycott and ostracism in the endeavor

to hold the status of the area. They often endeavor

to bring pressure from banks against loans on Negro

property in the neighborhood, and are sometimes

successful in this.

“ The danger in such associations lies in the tend

ency of unruly members to become inflamed and to

resort to acts of violence. Although they are a usual

phenomenon when neighborhoods are changing from

white to Negro in northern cities, no record was

found in this study where such an association had

been successful in stopping the spread of a Negro

neighborhood. The net results seem to have been a

slight retardation in the rate of spread and the crea

tion of a considerable amount of bitterness in the

community. ’ ,84 Cf. Embree, Brown Americans

(1943) at page 34 reporting 175 such organizations

in Chicago alone.

The same thesis with reference to the City of Detroit

was recently elaborated by Dr. Alfred M. Lee, Professor

of Sociology at Wayne University:

“ Emphasizing overcrowding and poor housing as

one of the major causes of racial disturbances, Lee

declared that in his opinion real estate dealers and

34 Woofter, op. cit., p. 73.

35

agents have been doing more to stir up racial an

tagonisms in Detroit than any other single group.

“ ‘ These men (real estate dealers),’ Lee said,

‘Are the ones who organize, promote and maintain

restrictive covenants and discriminatory organiza

tions. I am convinced that once it is possible to

break the legality of these covenants, a great deal of

our troubles will disappear.’ ” As reported in The

Michigan Ch/ronicle for May 9, 1945.

Other significant analyses of racial conflicts emphasize

the evils of segregation and its contribution to tension and

strife.

“ But they [the Negroes] are isolated from the

main body of whites, and mutual ignorance helps

reinforce segregative attitudes and other forms of

race prejudice.” Myrdal, An American Dilemma,

(1944) vol. 1, page 625.

‘ ‘ The Detroit riots of 1943 supplied dramatic evi

dence: rioting occurred in sections where white and

Negro citizens faced each other across a color line,

but not in sections where the two groups lived side

by side.” Good Neighbors, Architectural Forum,

January 1946.

The dangers to society which are inherent in the restric

tion of members of minority groups to overcrowded slum

areas are so great and are so well recognized that a court

of equity, charged with maintaining the public interest,

should not, through the exercise of the power given to it

by the people, intensify so dangerous a situation. There

fore, in the light of public interest, the court below erred

in granting the plaintiff’s petition and ordering the defen

dants to move from their homes.

36

Conclusion

In considering this question, it is immaterial that the

restrictive covenants sought to be enforced are directed

against Negroes. If valid for excluding Negroes, they would

be equally valid and enforceable by injunction if directed

against Jews, Catholics, Chinese, Mexicans or any other

identifiable group. One might even envisage a similar dis-

crimination against persons belonging to a political party—

Republicans or Democrats—depending upon the prevailing

opinion in the area.

Perhaps perpetual covenants against racial or religious

minorities might not have been oppressive in frontier days,

when there was a surplus of unappropriated land; but

frontier days in America have passed. All the land is

appropriated and owned. White people have the bulk of

the land. Will they try to make provision for the irresisti

ble demands of an expanding population, or will they

blindly permit private individuals whose social vision is no

broader than their personal prejudices to constrict the nat

ural expansion of residential area until we reach the point

where the irresistible force meets the immovable body?

37

For the reasons set forth above, it is respectfully re

quested that this Court issue a writ of certiorari as prayed

for in the accompanying petition.

Respectfully submitted,

F ran cis D e n t ,

W illis M. G raves,

446 E. Warren Ave.,

Detroit, Michigan,

T hitrgood M arshall ,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York,

Attorneys for Petitioners.

S pottswood W . R obinson , III

Richmond, Virginia,

M arian W y n n P erry,

New York City, New York,

Of Counsel.

[5973]

Lawyers P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y . C. 7; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300