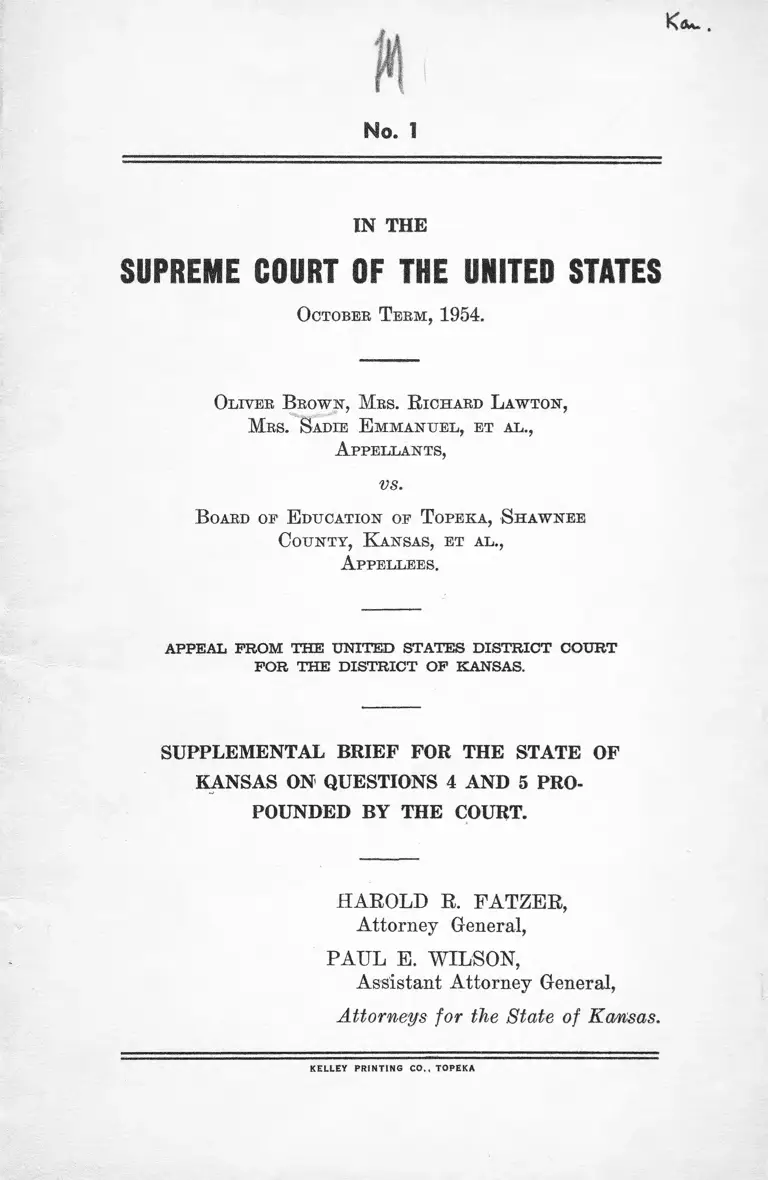

Brown v. Board of Education Supplemental Brief for the State of Kansas on Questions 4 and 5 Propounded by the Court

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Supplemental Brief for the State of Kansas on Questions 4 and 5 Propounded by the Court, 1954. 9e2767cf-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e721866d-207c-4ebc-9e23-fd617d35d61a/brown-v-board-of-education-supplemental-brief-for-the-state-of-kansas-on-questions-4-and-5-propounded-by-the-court. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October T erm , 1954.

Oliver B rown, Mrs. R ichard L awton,

Mrs. Sadie E m m anuel, et al.,

A ppellants,

vs.

B oard op E ducation op T opeka, Shawnee

County, Kansas, et al.,

A ppellees.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE STATE OF

KANSAS ON QUESTIONS 4 AND 5 PRO

POUNDED BY THE COURT.

HAROLD R. FATZER,

Attorney General,

PAUL E. WILSON,

Assistant Attorney General,

Attorneys for the State of Kansas.

KELLEY PRINTING C O ,, TOPEKA

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

Page

STATEMENT ............................... 1

THE QUESTIONS ......................................................... - 2

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS ...................... 3

ARGUMENT ON QUESTIONS PROPOUNDED.. . . 6

CURRENT DE-SEGREGATION TRENDS.......... 13

A tch ison ........................................................................... 14

Lawrence . . . .................................................................... 15

Leavenworth .................................................................. 16

Kansas City ....................*............................................ 19

Parsons . . • •......................................... 21

Salina ............................................................................... 22

Cities Reporting no Action..................................... 22

CONCLUSION ........................• •........... ........ .................. 23

Page

TABLE OF CASES.

Addison v. Holly Hill Co., 322 U. S. 607, 622.............. 9

Alabama Public Service Comm. v. Southern By. Co.,

341 U. S. 341, 351................................................. . 12

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al., 345

U. S. 972................................................................... .. 3

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al., 347

U. S. 483, 4 9 5 . . . . ........................................................... 2

Chapman y. Sheridan-Wyoming Coal Co., Inc., 338

U. S. 621, 630...............'......... ......................................... 8

Eceles v. Peoples Bank, 333 U. S. 426, 431.................. 8

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 3'21 U. S. 321, 329-330.............. 8

Henderson v. United States, 339 IT. S. 816.................. 11

International Salt Co. v. United States, 332 U. S. 392 11

Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, Registrar, 305

U. S. 337............................... ............. ........................ .. 11

Securities Exch. Comm. v. U S R & Impl. Co., 310

U. S. 434, Syl. 7 ............................................................. 9

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 232 U. S. 631...................... 11

United States v. Morgan, 307 IT. S. 183...................... 9

STATUTES CITED.

Section 21-2424, General Statutes of Kansas, 1949..,.. 4

Section 72-1724, General Statutes of Kansas, 1949... .4,13

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITER STATES

O ctober T erm , 1954.

No. 1

Oliver B rown, Mrs. R ichard L awton,

M rs. Sadie E m m anuel, et al.,

A ppellants,

vs.

B oard op E ducation op T opeka, S hawnee

C ounty, K ansas, et al.,

A ppellees.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OP KANSAS.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE STATE OF

KANSAS ON QUESTIONS 4 AND 5 PRO

POUNDED BY THE COURT.

STATEMENT.

On May 17, 1954, this Court announced its opinion that

racial segregation in public education per se is a denial

of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the

2

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States. At the same time the Court sought an expres

sion of the views of the parties relative to the specific

decrees to be entered in this case and other cases now

pending. More particularly, the Court’s request is as

follows:

4‘ In order that we may have the full assistance

of the parties in formulating decrees, the cases will

be restored to the docket and the parties are re

quested to present further argument on Questions

4 and 5 previously propounded by the court for re-

argument this term.” (Brown v. Board of Educa

tion of Topeka, et al., 347 U. S. 483, 495)

The following is respectfully submitted in an effort

to comply with that request.

THE QUESTIONS.

Questions 4 and 5 mentioned above, were set forth in

the Court’s order of June 8, 1953, and are quoted here

after :

“ 4. Assuming it is decided that segregation in

public schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment,

“ (a) would a decree necessarily follow providing

that, within the limits set by normal geographic

school districting, Negro children should forthwith

be admitted to schools of their choice, or

“ (b) may this Court,, in the exercise of its equity

powers, permit an effective gradual adjustment to

be brought about from existing segregation systems

to a system not based on color distinctions?

“ 5. On the assumption on which questions 4(a) and

(b) are based, and assuming further that this Court

3

will exercise its equity powers to the end described

in question 4(b),

“ (a) should this Court formulate detailed decrees

in these cases;

“ (h) if so what specific issues should the decrees

reach;

“ (c) should this Court appoint a special master to

hear evidence with a view to recommending specific

terms for such decrees;

“ (d) should this Court remand to the courts of first

instance with directions to frame decrees in these

cases, and if so, what general directions should the

decrees of this Court include and what procedures

should the courts of first instance follow in arriving

at the specific terms of more detailed decrees?”

(Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al.,

345 IT. S. 972.)

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS.

We pause at the outset of these comments to empha

size that we do not approach the present questions as

an adversary. Heretofore in the arguments of Decem

ber, 1952, and upon reargument in December, 1953, we

presented as fully as we could the arguments in justifica

tion of the statute authorizing certain boards of educa

tion in Kansas to provide for the education of Negro

children in separate schools of equal facility. The argu

ments then advanced appeared consistent with the re

ported decisions of this Court, the Supreme Court of

Kansas, and Appellate Courts elsewhere. However, the

issue in this case has now been determined contra to the

position we then urged. We accept without reservation

4

or equivocation the Court’s declaration that “ in the

field of public education, the doctrine of ‘ separate but

equal’ has no place.” We assure the Court that the

resources of state government will be employed to ef

fectuate the decision in the public schools of Kansas.

Hence, the sole purpose of this brief is to supply such

information as may assist the Court in finally dispos

ing of the Kansas case.

Of the several cases at bar we suspect that the Kan

sas case may be least complex. Several considerations

point to this conclusion. In earlier arguments we have

pointed out that the practice of segregation in public

education has never been widespread among the com

munities of the state. Traditionally, Kansans abhor in

equality. Except in the case of the elementary schools

in cities of the first class, the statutes of Kansas spe

cifically prohibit school authorities from making distinc

tions based on race, color or previous condition of servi

tude. (G. S. 1949, 21-2424) Moreover, we think it is

significant that quite apart from the Courts decision

of May 17, 1954, and through the normal exercise o f

local autonomy, an accelerated adjustment from exist

ing segregated systems to a system, not based on color

distinction has been in progress throughout the state.

Indeed, it might well be argued that the instant case

is moot by reason of the action of the Topeka Board

of Education more fully described in its separate brief

filed herein.

Segregation has never existed in Kansas as a matter of

state policy. Section 72-1724, General Statutes of Kan

5

sas of 1949', which has been declared unconstitutional in

the present litigation, purported to permit rather than to

require segregated elementary schools in the areas to

which it applied. Those segregated systems that have

been maintained, have existed by virtue of action of local

boards of education. Hence we do not contemplate that

the termination of segregation in Kansas will be the oc

casion for any policy adjustment on a state level. No

provision of the Constitution of Kansas is affected by

the Court’s decision of May 17, 1954. There is no oc

casion for state legislation to provide for or implement

the process of de-segregation. The abandonment of seg

regated school systems will not require the alteration of

any policy established by the State Department of Pub

lic Instruction or any other state administrative agency.

Emphatically, de-segregation will produce no cultural

problem nor will it disrupt an established way of life.

In fact, there has been no significant amount of protest

on the part of any group of Kansas citizens to the elimi

nation of separate schools. Indeed, the prevailing atti

tude has been one of approval. Presumably, political

party platforms reflect attitudes accepted by their mem

bers. Note the statement quoted hereafter from the

1954 platform of the Republican Party of Kansas:

“ We hail the recent historic decision of the Su

preme Court of the United States as upholding the

traditional position of the Republican Party that

there can be no second class citizens under our Amer

ican form of government.” (***)

In view of the foregoing, we cannot, in candor, sug

gest that at state level there are any barriers, legal or

6

otherwise, to the immediate termination of such segre

gated public school systems as may exist in Kansas. The

problems incident to the de-segregation process will be

encountered on the local level only, and will be proced

ural rather than substantial, pragmatic rather than es

sential. At the same time, they are problems that ob

viously cannot be resolved forthwith by resolutions of

boards of education or even by decrees of this Court.

Time will be required for deliberation, for decision and

for adjustment. How much time? We do not presume

to say. We suggest only that in those cases where, as

in Kansas, responsible state and local officials are pro

ceeding in diligence and good faith to effect the adjust

ment required by the Court’s opinion herein, such ef

forts should be recognized by this Court and be per

mitted to proceed with a minimum of judicial direction.

ARGUMENT ON QUESTIONS PROPOUNDED.

The briefs submitted by the several parties and amici

curiae prior to the December 1953 arguments, reveal

little significant divergence of view relative to the prin

ciples applicable to Questions 4 and 5. Hence, we dis

cuss the questions somewhat summarily.

“ 4. Assuming it is decided that segregation in pub

lic schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment,

(a) would a decree necessarily follow providing-

that, within the limits, set by normal geopraphic

school districting, Negro children should forthwith

be admitted to schools of their choice, or

(b) may this Court, in the exercise of its equity

powers, permit an effective gradual adjustment to

7

be brought about from existing segregated systems

to a system not based on color distinctions?”

The assumption stated has now become the established

principle of law. The questions go to the power of a

court of equity.

We think that a decree providing that, within the

limits set by normal geographic school districting, Negro

children should forthwith be admitted to schools of their

choice, does not necessarily follow the opinion of May

17. On the other hand, we believe that this Court, in

the exercise of its equity powers, may permit an effec

tive gradual adjudgment from existing segregated sys

tems to a system not based on color distinctions. The

very fact that these questions are now being argued,,

some seven months after the decision that segregation

violates constitutional rights, suggests that the power to

postpone compliance does exist.

The decree must seek to reconcile the personal and

present interest of the Negro citizen, whose constitutional

rights have been violated, with the public interest in

safeguarding the integrity of the school system. To il

lustrate, we call attention specifically to a statement con

tained in the separate brief of the Board of Education

of Topeka submitted prior to the December, 1953, ar

guments :

“ If this Court should enter an order to abolish

segregation in the public schools of Topeka ‘ forth

with’, as suggested in Question 4(a), the Topeka

Board would, of course, do its best to comply with

the order. We believe, however, that it would prob

ably require that the regular classes be suspended,

8

while the many administrative, changes and adjust

ments are being made, and while the necessary trans

fers of and reassignment of students and teachers

are being made. Important decisions would have to

be hurriedly made, without time for careful investi

gation of the facts nor for careful thought and re

flection. Most decisions would have to he made on

a temporary or an emergency basis. We believe the

attendant confusion and interruption of the regular

school program would be against the public interest,

and would be damaging to the children, both negro

and white alike.” (pp. 4-5) (Italics supplied)

We think it cannot be disputed that a court of equity

has power to avoid such a consequence.

The reports abound with authority for the proposition

that it is the duty of a court of equity “ to strike a

proper balance between the needs of the plaintiff and

the consequences of giving the desired relief.” (Eccles v.

Peoples Bank, 33-3 IT. S. 426, 431.)

“ . . . equity will administer such relief as the

exigencies of the case demand at the close of the

trial.” (Chapman v. Sheridan-Wyoming Coal Co.,

Inc., 338 U. S. 621, 630.)

“ The essence of equity jurisdiction has been the

power of the Chancellor to do equity and to mould

each decree to the necessities of the particular case.

Flexibility rather than rigidity has distinguished it.

The qualities of mercy and practicality have made

equity the instrument for nice adjustment and re

conciliation between the public interest and private

needs as well as between competing private claims.”

(Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321, 329-330.)

“ It is familiar doctrine that the extent to which

a court of equity may grant or withhold its aid, and

9

the manner of moulding its remedies,, may be affected

by tbe public interest involved.” (U. S. v. Morgan,

307 U. S. 183.)

“ A court of equity has discretion, in the exercise

of jurisdiction committed to it, to grant or deny re

lief upon performance of conditions which will safe

guard the public interest.” (Securities Exch. Comm,.

v . U S R S Imp. Co., 310 U. S. 434, Syl. 7.)

“ In short, the judicial process is not without the

resources of flexibility in shaping its remedies

. . . ” (Addison v. Holly Hill Co., 322 TJ. S. 607,

622.)

We presume that no principle of equity jurisprudence is

more familiar than that illustrated by the foregoing

statements. It would seem that the authorities cited

would preclude further argument on Question 4. How

ever, this proposition has been discussed at some length

in the supplemental brief for the United States on re

argument filed herein prior to the arguments in Decem

ber, 1953. We call the Court’s attention specifically to

the discussion and authorities contained in that brief on

pages 152 to 167, inclusive, and suggest that we are in

substantial agreement with the views expressed therein.

Question 5 assumes that 4(b) has been answered in

the affirmative. The Court then inquires:

“ (a) should this Court formulate detailed decrees in

these cases;

“ (b) if so what specific issues should the decrees

reach;

“ (c) should this Court appoint a special master to

hear evidence with a view to recommending specific

terms for such decrees;

10

“ (d) should this Court remand to the courts of first

instance with directions to frame decrees in these

cases, and if so, what general directions should the

decrees of this Court include and what procedures

should the courts of first instance follow in arriving

at the specific terms of more detailed decrees!”

This question compels our attention to the inherent

limitations on the judicial power. We doubt that the

Court contemplates the judicial development of a plan

for the de-segregation of the schools of Kansas or any

other state. If such action is contemplated, we doubt

that it is legally or practically feasible. The Court

may determine, as it has determined, that the segregated

school system heretofore maintained in Topeka, Kansas,

violates the Constitution of the United States. It may

determine whether a gradual adjustment to a system

not based on color distinctions is authorized. However,

it cannot tell the Topeka Board of Education what non-

segregated school system, will be substituted for the one

heretofore maintained, nor can it prescribe the course

to be followed in effecting the substitution. These are

determinations that must necessarily be made with refer

ence to local conditions—conditions that were not ger

mane to the question of whether segregation per se is

unconstitutional and hence are not reflected by the rec

ord now before the Court. They are determinations that

must be made by local officials who are familiar with

local conditions and who are responsible for local educa

tional policy and for the general administration of the

school system. We urge that those officials be given the

11

maximum latitude consistent witli the rights of appel

lants.

We emphasize that in the exercise of appellate juris

diction, the Court’s considerations are limited by the

record forwarded from the court of original jurisdiction.

The present questions have appeared in the case since

the trial in the court below. Hence, before any detailed

decree could be framed, additional evidence would prob

ably be required. We suggest that the District Court is

the proper forum to hear evidence and determine facts.

“ The framing of decrees should take place in the

district courts rather than in the appellate courts.”

(International Salt Co. v. United States, 332 U. S.

392.)

A review of the precedents would indicate that this

Court, as a matter of policy, has heretofore refused to

frame detailed decrees in cases involving segregation in

education. In those cases where school facilities have

been held unequal and where administrative action has

been required to secure equality, the Court has not at

tempted to determine precise standards to be observed

by the parties in order to finally dispose of the case.

Rather, the Court has been content to remand the case

to the lower court for further proceedings consistent

with and in conformity with its opinion. (Sipuel v.

Board of Regents, 332 TJ. S. 631; Missouri ex ret. Gaines

v. Canada, Registrar, 305 IJ. S. 337, and Henderson v.

United States, 339 IJ. S. 816.)

Thus, we answer part (a) of Question 5 in the nega

tive. This answer obviously precludes comment on part

12

(b). Similarly, we answer part (c) in the negative. We

believe that the only order necessary in the present case,

indeed, the only one justified by the circumstances, is

one reversing the judgment of District Court, and re

manding the cause to said court with directions to enter

an appropriate decree. We suggest further that the Dis

trict Court be directed to retain jurisdiction of the cause

until such time as the maintenance of segregated schools

by Appellee Board of Education is finally terminated.

Implicit in such an order would be the power of the

District Court upon appropriate motion by any of the

parties to deal with special problems arising during the

transition period.

Finally, we suggest that the decrees of both this Court

and the District Court should provide for a minimum

of judicial control.

“ It is in the public interest that federal courts of

equity should exercise their discretionary power to

grant or withhold relief so as to avoid needless ob

struction of the domestic policy of the states . . . ”

(Alabama Pub. Serv. Comm. v. Southern By. Co.,

341 U. S. 341, 351.)

Wherever responsible state and local officials are pro

ceeding in good faith to make the adjustments required

by the Court’s opinion of May 17, 1954, we suggest that

their efforts be recognized and that they not be hedged

by detailed judicial orders.

13

CURRENT DE-SEGREGATION TRENDS.

In its separate brief, the Topeka Board of Education

has advised the Court o f its action to terminate its seg

regated schools. Hence, we comment on that situation

only briefly. Since September, 1953, Topeka has moved

from universal segregation in its elementary schools,

to a system consisting of 12 integrated schools, two par

tially integrated, five schools maintained exclusively for

white students and four attended only by Negroes. One

hundred and twenty-three Negro students now attend

mixed elementary schools. We deem this significant pro

gress.

In other communities of Kansas, boards of education

not parties to this suit are initiating similar policies.

Since these arguments have apparently come to tran

scend the original parties and issues, we trust it is not

improper to comment on the experience of Kansas in

areas other than Topeka.

Section 72-1724, General Statutes of Kansas, 1949, au

thorizing segregated elementary schools, applied to twelve

cities of the state. One city, Hutchinson, never exercised

the power the statute purported to confer. Two cities,

Wichita and Pittsburg, maintained separate elementary

schools for many years, but for reasons of local policy,

terminated the practice in 1952. The recent action of

Topeka is mentioned above and is detailed in the sepa

rate brief of its Board of Education. Six other cities

of the state have, during the past year, commenced or

completed the process of de-segregating their public

schools.

14

Atchison. Atchison, a city of 13',000 persons, is located

on the boundary between Kansas and Missouri. Its pop

ulation is about 10% Negro. Segregation has been

maintained in the public elementary schools of Atchison

since the establishment of the system. It may be signifi

cant that the city was founded in 1854 by persons of

pro-slavery sympathies and for years the southern tra

dition was manifest in the community. Prior to the pres

ent school year four elementary schools, each serving a

fixed geographical area, have been maintained. exclusively

for white students and one elementary school has been

maintained for Negroes. On September 12, 1953, the

Board of Education adopted the following resolution:

“ That the plan of abolition of segregation in the

public schools of Atchison heretofore established by

the Board of Education and which has been effected

in grades seven through twelve be intensified so as

to complete the plan throughout grades one through

six as soon as practicable.”

Subsequent thereto, on June 9, 1954, the policy was

implemented by the adoption of a further resolution,

the text of which is set forth hereafter:

“ Motion was made by Mr. Thorning that segrega

tion of negro pupils be discontinued as of this date

in all Atchison city school districts with the excep

tion . of the Martin-Lincoln district; thereby eliminat

ing the necessity for operation of the school bus

transporting pupils to Lincoln school; also, that be

ginning with the school term of September 1955, all

segregation be ended in the Martin-Lincoln district

under such a plan as will promote the best interests

of the students in our school system.”

15

At the present time in excess of 25% of the Negro

students of the city are attending mixed schools. The

Board o f Education anticipates that the process of de

segregation will he completed by September 1, 1955. In

addition to the integration of students as above set forth,

a Negro has been employed as an elementary class-room

teacher, teaching predominately white 6th grade classes.

School administrators anticipate that all Negro teachers

presently employed, will be assimilated into the inte

grated system.

Lawrence. Seat of the State University, Lawrence is

a city of 24,000 population. About 7% of the people

are Negro. Segregated schools had been maintained

since prior to 1869. The process of assimilating the

Negroes into white schools was apparently begun about

1916, with the result that during the past few years only

one school had been maintained exclusively for Negroes.

Subsequent to the decision of the Supreme Court of

May 17, 1954, the Lawrence Board of Education ordered

the immediate termination of segregation in all its pub

lic schools. In addition a Negro teacher was employed

in the school system to teach special classes in junior

high school and to teach physical education in the ele

mentary schools, all of which classes are attended by pre

dominately white students. The seriousness with which

this community approaches the problem is indicated by

the following comment of a school official in a communi

cation addressed to the Attorney General of Kansas:

“ We recognize that some Kansas communities

have problems more grave than ours—and we have

some hurdles certainly.

16

“ Does integration mean the mixing of white and

colored pupils only! What is the status of the col

ored teacher! This year we employed one colored

teacher on the basis of qualification for the job—but

we recognize the possibility of unfavorable reaction

when a colored person is employed as a teacher of a

self contained room. Such adaptations must come

slowly but must be achieved if integration is to be

more than a term referring to mixing of colored and

white pupils.”

Leavenworth. Leavenworth, a city in excess of 20,000

inhabitants, has a Negro population of about 10%. The

segregated system of elementary schools was established

in 1858 and has been maintained consistently since that

time. At present two elementary schools are maintained

exclusively for Negro students, whereas nine are attended

only by white. The policy announced by the Leaven

worth Board of Education of August 2, 1954, indicates

the reaction of the people of this community to the de

cision of May 17. The statement of policy is set forth

hereafter:

“ Pupils who enter the kindergarten or the first

grade in the fall of 1954 will be permitted to enroll

in the school of the district in which they reside

regardless of race. Such negro pupils regardless of

residence may continue to attend Lincoln and Sum

ner schools which will be adequately staffed with cap

able Negro teachers. It will be necessary for a time

to establish attendance districts for the Lincoln and

Sumner schools in order to carry out this policy. It

is the belief of the Board of Education that the

negro people in the Leavenworth community may

desire to continue their schools as presently oper

ated for a term of years during the transition period.

17

“ The Board of Education in this statement of

policy believes it to be consistent with the Supreme

Court decision in that it is starting in an orderly

way to move away from compulsory segregation.

“ It is believed that integration, when desired by

the parents, can best be initiated at the lower grade

levels. Those colored pupils who enroll in non-negro-

staffed schools at the kindergarten or first grade

level may continue in the school through subsequent

grades.

“ It is believed that it will be best for the individ

ual if integration begins at the primary level. Also,

the existing school system has been established in

a certain pattern, and because of limited facilities,

the pattern of enrollment cannot be suddenly changed.

The Board of Education is required to provide

school facilities and to frame policies for the welfare

of all pupils.

“ The Board will continue to study the problem

and restate its policies consistent with the expressed

desires of the people within the framework of the

Supreme Court decision.

“ The Board solicits the cooperation of all citi

zens in making an orderly transition from a segre

gated to a non-segregated school system. It looks

to the State Legislature, the State Department of

Public Instruction and the Attorney General for

counsel in the continuous reframing of its policies

consistent with the Supreme Court’s interpretation

regarding the constitutionality of the Kansas statute

under which Leavenworth schools have operated since

1879.

“ The Board will make an effort to follow the sug

gestions and recommendations of the Supreme Court

as promised to be made by that body subsequent to

October, 1954.”

18

The first positive step taken by the Leavenworth school

system consistent with its declared policy has been the

admission during the 1954-55 school year of kindergarten

and first-grade pupils to the school nearest their resi

dence regardless of race. Presumably nest year the

Board intends to extend this policy to the second or

higher grades, although a positive statement to this ef

fect has not been announced. The following comment of

a public school official of Leavenworth suggests one of

the problems incident to de-segregation, and the com

munity’s approach thereto :

“ It is the intention of the Leavenworth Board of

Education to be completely fair in the treatment of

its faithful and competent negro teachers. It has

been in the cities maintaining segregated schools

where the opportunity for employment has existed

for negro teachers. There will be questions raised

as to why we cannot suddenly integrate our teach

ers in these cities, and there will be a few sporadic

cases for publicity purposes to illustrate that negro

teachers can be used indiscriminately. There are

frequent cleavages between teachers and pupils at

best. Some pupils resist authority and for various

reasons have to be disciplined, restrained, or cor

rected. This often puts parents on the defensive

and causes them to question or resist the teacher’s

authority. Now, if that teacher of a white child

should be a negro, the cleavage would be magnified

fifty to a hundredfold. I am sure you are well

aware of this.

“ The Leavenworth Board believes that for a con

siderable length of time, negro teachers will be used

in schools attended almost entirely by negro pupils.

It is perfectly logical to ask, why cannot we inte

grate them in one magnanimous action! What about

19

communities like Hutchin&on who has never had seg-

gregation? Have they ever employed a negro teacher

or are they likely to start employing them now? In

my judgment, the solution will have to be carefully

and slowly introduced. You and I and most board

members will readily agree to the righteousness of

complete integration from the standpoint of our es

tablished principles of decency, Christianity and de

mocracy. However, there is a sufficient number of

biased and prejudiced persons who will make life

miserable for those in authority who attempt to move

in that direction too rapidly. As a consequence,

many of us will be accused of ‘ dragging our feet’

in the matter, not because of our personal feelings

or inclinations, but because in dealing with the pub

lic, its general approval and acceptance is indispens

able. One cannot force it, he can only coax and nur

ture it along.”

Kansas City. Kansas City has a total population of

about 130,000, 20.5 percent of which belong to the Negro

race. It is adjacent to Kansas City, Missouri. It is

perhaps significant that the proportion of Negroes in

Kansas City, Kansas, is1 greater than in such southern

cities as Dallas, Louisville, Saint Louis, Tulsa, Miami

and Oklahoma City, and only slightly less than that of

Baltimore. Kansas City is the only community in Kan

sas where by virtue of law segregated high schools have

been maintained. Prior to the present school year the

City of Kansas City has maintained seven elementary

schools, one junior high-school and one high school ex

clusively for its 6000 Negro students, while twenty-two

schools were attended by more than 23,000 white stu

dents. On August 2, 1954, the following statement of

20

policy was adopted by tbe Board of Education of Kan

sas City:

“ The members of the Board of Education, meet

ing as a committee of the whole, propose the adop

tion of the following statement of policy with refer

ence to the Supreme Court decision on segregation:

“ The Board of Education of the City of Kansas

City of the State of Kansas hereby declares its in

tent to abide by the spirit as well as the letter of

the Supreme Court’s decision on segregation. Spe

cifically, the Board of Education proposes:

“ 1. To begin integration in all the public schools

at the opening of school on September 13, 1954.

“ 2. To complete the integration as rapidly as class

room space can be provided.

“ 3. To accomplish the transition from segregation

to integration in a natural and orderly manner de

signed to protect the interests of all the pupils and

to insure the support of the whole community.

“ 4. To avoid any disruption of the professional

life of career teachers.

“ With these objectives in mind, the Board of Edu

cation directs the Superintendent of Schools within

the framework of this policy declaration to be re

sponsible for developing and applying the plan of

integration. ’ ’

The plan subsequently adopted permitted Negro stu

dents in kindergarten and grades 1, 6, 7, 10, 11 and 12

to enter the school of their choice within normal geo

graphic limitations. Because the bulk of the Negro

population is concentrated in one area of the city, the

termination of compulsory segregation will not elimi

21

nate schools attended exclusively by Negroes, However,

a total of 233' Negro students are now attending mixed

schools, and approximately 1000 more live in areas where

the process of amalgamation is now in progress. A re

port to the Attorney General’s Office, dated October 12,

1954, from a school administrator indicates:

“ The announced program by the Board of Edu

cation was well received by whites and negroes alike

and it is felt that integration in our schools is ac

cepted and will be completed when classroom space

permits. We are now engaged in the completion of

a 6V2 million dollar building program which includes

the immediate problem before us.”

School officials anticipate that subsequent to the com

pletion of the amalgamation program all Negro teachers

presently employed in the system will be retained.

Parsons. Parsons is located in southeastern Kansas

some twenty miles from the Oklahoma border. It is a

city of about 15,000 population, less than 10% of whom

are Negroes. Prior to the current school year four ele

mentary schools were maintained for white students and

one for Negroes. Commencing with the current year,

the Board of Education announced a policy to the effect

that whenever possible and practical, restrictions on

school attendance are to be immediately removed and

segregation eliminated. I11 line with this policy, segre

gation was eliminated in three of four ward elementary

school areas at the beginning of the 1954-55 school year.

The remaining school area is being operated on a segre

gated basis because of crowded conditions. The sepa

rate Negro school is located in this ward. Consequently

22

every child may attend an elementary school in the ward

in which he resides.

It is the present policy of the Board to delay inte

gration of the schools o f the fourth ward until additional

school facilities will be completed. At the present time

twenty-six Negro students in Parsons are attending mixed

elementary schools, while one hundred and forty-three

are required to attend the school maintained exclusively

for Negroes.

Salina. Segregation was terminated in the City of

Salina prior to the opening of the current school term.

In view of the fact that less than 3% of the city’s 27,000

people are Negroes, the problems incident to assimila

tion were slight. Prior to the present school term, one

school was attended by all Negroes of the city. The

present policy of the Board of Education permits all

students to attend the school located nearest their homes.

Cities Reporting no Action. Only two cities, Coffey-

ville and Fort Scott, report that action by their Boards

of Education has been delayed, pending final determina

tion of this case. In these cities an aggregate of about

400 Negro students attend three segregated schools.

Both cities are located in Southern Kansas, and school

officials indicate that there has been no local sentiment

in favor of the termination of the policy of segregation.

In one city, it is reported that the only protest against

the prospect of de-segregation has come from the Negro

citizens. However, in each of these communities local

school officials stand ready to take such action as may be

consistent with the policies to be announced by this Court

and the best interests of their people.

23

CONCLUSION.

We respectfully submit that all considerations ger

mane to the present issues require that the decree of

this Court do no more than reverse the judgment of the

District Court and remand the cause to said court with

directions to enter judgment consistent with the opinion

herein and to retain jurisdiction thereof until said judg

ment be complied with.

HAROLD R. FATZER,

Attorney General,

PAUL E. WILSON,

Assistant Attorney General,

Attorneys for the State of Kansas.