Plaintiff-Appellee's Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

May 10, 2001

15 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Plaintiff-Appellee's Petition for Rehearing, 2001. e0095621-e10e-f011-9989-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e73b20b2-f062-4b22-84f7-7d6ee251385a/plaintiff-appellees-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

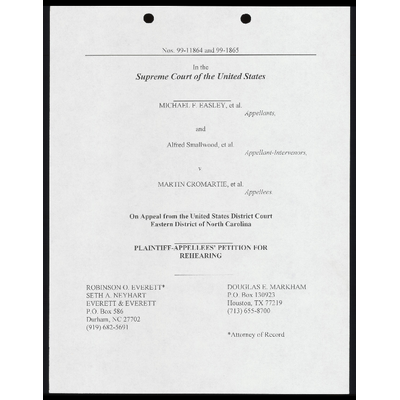

Nos. 99-11864 and 99-1865

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

MICHAEL F. EASLEY, et al.

Appellants,

and

Alfred Smallwood, et al.

Appellant-Intervenors,

V.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

PLAINTIFF-APPELLEES’ PETITION FOR

REHEARING

ROBINSON O. EVERETT* DOUGLAS E. MARKHAM

SETH A. NEYHART P.O. Box 130923

EVERETT & EVERETT Houston, TX 77219

P.O. Box 586 (713) 655-8700

Durham, NC 27702

(919) 682-5691

* Attorney of Record

ia

TABLE OF CON TENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS iinet 200, ih ae

-ji-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996) (O’ Connor, J.,

PLuality OpIOn). oo. . oo SER E a ss hi 8

Easley v. Cromartie, U.S. 121 S.Ct. 1452

@ on

Kelley v. Everglades Drainage Dist., 319 U.S. 415 (1943) . 6

Miller v. Johnson, 515U.S.900 (1995) .............. 4,6

Show v. Hunt, S17US. 899(1996) .. ou iii 8,9

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) ................ 4,10

STATUTES AND RULES

¢: RClv PSA) 5. cb sae, Dh was 1,6

Sup. Coludd on Ee 1

NCOS SI6330 ro, iia 3

NCGS 5163824... ..... .. =. leon 3

NCGS S163 ns. ak 3

1

PETITION FOR REHEARING

Pursuant to Rule 44 of the Rules of the Supreme Court

of the United States, plaintiff-appellees hereby respectfully

petition the Court for a rehearing as to its decision on the merits

in the above captioned cases. In support of their petition, they

show the Court:

INTRODUCTION »

The opinion of the Court involves the factual review o

the findings made by the District Court on remand. The

standard purportedly applied is that prescribed by Federal Rule

of Civil Procedure 52(a), which provides that findings be set

aside only if “clear error” is found and requires the reviewing

court to give weight to the circumstances that the lower court

heard the evidence and determined the credibility of the

witnesses. However, in its “extensive review” of the District

Court’s findings for clear error, Easley v. Cromartie, U.S.

__, 121 S.Ct. 1452, 1459 (2001), the Court overlooked and

discounted the significance of important evidence of the

predominant racial intent behind the formation of the 1997

Plan’s Twelfth District.

Furthermore, the Court created confusion »@)

announcing a new test which is unclear and seems to undercut

some of the Court’s well-established precedents concerning

racial gerrymandering, even while claiming to be faithful

thereto. Indeed, under the most plausible reading of the

majority opinion, no North Carolina congressional district -

past or present - could be successfully challenged.

I. THE COURT IGNORED PERSUASIVE EVIDENCE

In applying Rule 52(a), the key issue is whether

persuasive evidence is present in the record to sustain the

findings of the court below. The opinion of the Court makes

clear that the extensive “voter registration” evidence offered by

the plaintiff-appellees and the expert testimony based thereon

2

were not persuasive in its view. Indeed, the opinion criticizes

the District Court for relying on evidence which “focuses upon

party registration, not upon voting behavior,” and notes that

“registration figures do not accurately predict performance at

the polls.” Easley, U.S.at __ , 1452 S.Ct. at 1460. This

statement, however, is at odds with the Court’s ensuing

reference to the undisputed testimony that in North Carolina

African-Americans “register and vote Democratic between 95%

nd 97% of the time.” Id. If, as in North Carolina, voter

gistration data includes race, then the information that a

registered voter is an African-American does “accurately

predict” that he or she will vote Democratic. Also, in light of

the cohesiveness of blacks in voting for black candidates, Jt.

App. at 589, the registration information as to race does

“accurately predict” that a black Democratic voter will vote for

a black candidate against a white candidate in a Democratic

primary. Thus, voter registration data enables legislators to

form predictable districts that will provide a desired racial

outcome in Democratic party primaries.

From the outset of the trial, plaintiff-appellees presented

their contention that the racial gerrymandering of the Twelfth

District was especially evident in relation to the Democratic

rty primaries in North Carolina.! It was also called to the

ourt’s attention on appeal. Appellees’ Brief at 26-7.

Nonetheless, the Court’s opinion does not mention party

primaries - which are state action subject to equal protection.

'According to plaintiff-appellees’ factual contention 3(c) in the

Final Pre-Trial Order, “[t]he challenged districts are overly safe for

Democratic candidates, but are instead constructed so that blacks

predominate in the Democratic primary electorate, and so that nomination

and election of African-Americans to Congress is assured.” This

contention was repeated by Dr. Weber at trial, see, e.g, Jt. App. at 754 and

thus was adopted by the District Court in its references to Dr. Weber’s

entire testimony. Appellants’ J.S.App. at 26a.

3

Under North Carolina’s closed primary system, a voter

may vote in a party primary only if he or she has registered as

a voter of that party or, in some instances, as an independent.

N.C.G.S. § 163-59. Thus, voter registration data reveals how

many persons may vote in the primary of each major party and

how many of those eligible to vote in a party primary are of a

particular race. N.C.G.S. § 163-82.4. Since African-American

are cohesive in voting for a candidate of their race, t

percentage of registered voters who are black Democrats give

the black Democratic candidate a solid bloc of support.

If the incumbent, Representative Watt, had for some

reason decided not to run for reelection, the district, as created

pursuant to the registration data, would nonetheless have

nominated and elected an African American to Congress.

According to Rep. McMahan speaking on the House floor, the

district “[a]bsolutely without any question” was designed so

that not only Mel Watt but also “anyone else that might choose

as a minority to run in that District should feel very, very

comfortable . . . that they could win.” Jt. App. at 470.

In its opinion, the Court also ignored or brushed aside

other persuasive evidence. For example, the Court did not eve

mention the finding of the District Court that “a motive exist)

to compose a new Twelfth District with just under a majority-

minority in order for it not to present a prima facie racial

gerrymander.” Appellants’ J.S. App. at 28¢. This finding is

solidly based on a number of statements in the record by

Senator Roy Cooper, the chair of the Senate Redistricting

Committee, and other legislators. See Appellees’ Brief at 35-

“North Carolina also provides for second primaries if the leading

candidate receives less than 40% of the vote. N.C.G.S. § 163-111. Thus,

if an African-American is to be nominated it also is important that the

aggregate number of white Democrats and independents in this district be

less than 40% of the total number of registered Democrats and

independents.

4

40. The goal of keeping the population of African-Americans

just below 50% in the Twelfth District in order to avoid the

limitations imposed by Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993), was

clearly race based. As the District Court noted, “using a

computer to achieve a district that is just under 50% minority

is no less a predominant use of race than using it to achieve a

district that is just over 50% minority.” Appellants’ J.S. App.

at 28a.’

® Although the Court acknowledged that the E-mail from

Gerry Cohen to Senator Cooper about moving “the Greensboro

black community” had some weight as evidence,’ it failed to

comment on the fact that by the move referred to in the message

“a significant number” of black voters had been placed within

the Twelfth District. Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900, 916

(1995). Nor did the Court acknowledge that in the 1997 plan

90.2% of the African-American population of its Twelfth

District had also resided in the unconstitutional race-based

Twelfth District of the 1992 plan, but only 48.8% of the white

population had done so. Jt. App. at 78. This statistic suggests

that a “significant number” of persons - in this instance white -

had been moved because of their race, and correspondingly a

“significant number” of African-Americans had been retained

®-. of their race. Cf. Miller, supra. Moreover, these

figures suggest that references in the legislative record to

3At the same time, as evidenced by the E-mail from Gerry Cohen

to Senator Cooper, the General Assembly was seeking to assure that the

First District would be just over 50% African-American; and the District

Court properly found that race was the General Assembly’s predominant

motive in forming that district. Appellants’ J.S .App. at 31a.

“That weight would have been even more apparent had the

majority noted that Cohen, who authored the E-mail, was the draftsman of

the 1991, 1992, 1997, and 1998 congressional redistricting plans for North

Carolina and that Senator Cooper, the addressee, was chair of the Senate

Redistricting Committee. Jt. App. at 372, 588-89.

5

retaining the “core” of the unconstitutional 1992 Twelfth

District meant retaining the “racial core.” See also Jt. App. at

779 (Senator Winner describing how the various black

communities of cities were considered to be the core of the

1992 Twelfth District). The Court also ignored the testimony

of legislators that the Twelfth District was race-based,’ and

disregarded the history that led to the replacement of the 199

plan’s Twelfth District by the 1997 plan’s Twelfth District

then by the 1998 plan’s Twelfth District.

Finally, the Court dismisses the probative force of the

1998 redistricting plan enacted by the North Carolina General

Assembly after the District Court had granted summary

judgment against use of the 1997 plan. In that alternative plan,

instead of severing all six of its counties, the Twelfth District

contained all of Rowan County and divided only four other

counties. As is obvious from the maps filed with the Court, the

1998 plan is far more geographically compact than its 1997

predecessor. Jt. App. at 501-2. Its percentage of African-

Americans is only around 36% - instead of 47% as in the 1997

plan. Moreover, the goals stated by the General Assembly in

drawing this plan were the same as those set forth by the sam

legislators in drawing the 1997 plan. See Ex. 146 10:8

Section 5 Submission). Additionally, the 1998 plan, which did

not include Greensboro in the Twelfth District, is not dissimilar

from some models that the General Assembly had considered

before moving the “Greensboro black community” into the

Twelfth District in February 1997. See Ex. 126-129.

The 1998 plan and others had been relied on by Dr.

These legislators - Horton, Wood, and Weatherly - testified that

the boundaries of the Twelfth District were race-based in the District's

three largest counties - Forsyth, Guilford, and Mecklenburg. Appellants’

J.S. App. at 5a-6a. Another witness, R. O. Everett, described in detail how

Rowan County was divided along racial - rather than political lines. /d. at

6a.

6

Weber, the expert for plaintiff-appellees, in testifying that if the

Twelfth District had not been predominantly race-based, the

General Assembly would have considered favorably such an

alternative plan. The Court, however, brushes aside Dr.

Weber’s well-founded expert testimony and disregards the 1998

plan because the “District Court did not rely upon the existence

of the 1998 plan to support its ultimate conclusion.” Easley,

US. at ___, 121 S.Ct. at 1462 (citing Kelley v. Everglades

@ i: Dist.,319 U.S. 415, 420, 422 (1943)). However, this

comment - used to justify ignoring important evidence -

manifests a unique interpretation of “rely” and of Kelley,

because the district court did “rely” on the testimony of Dr.

Weber, who, in turn, “relied” on - and cited - the alternative,

less race-based 1998 plan. See, e.g, Jt. App. at 108, 157.

More significantly, the Court rejected the 1998 plan,

even though that plan satisfies in many respects the test set

forth in the last paragraph of the Court’s opinion. It fulfilled

the purported political objectives originally announced by the

General Assembly of reelecting a Democrat (sometimes stated

as reelecting the incumbent); it conformed more to traditional

districting principles than did its 1997 predecessor; and - at

ast in one sense - it achieved “significantly greater racial

lance.” By disregarding the 1998 plan, as well as in many

other aspects of its opinion, the Court made clear that it had

usurped the task of the factfinders in determining weight of

evidence and credibility of witnesses; and by so doing it

violated Rule 52(a) and created new law while purporting

merely to apply existing precedents.

II. THE COURT’S OPINION AND THE TEST IT

ANNOUNCES WILL PRODUCE CONFUSION AND

UNINTENDED RESULTS, RATHER THAN PROVIDE

GUIDANCE FOR REDISTRICTING.

The Court’s failure to give weight to the persuasive

evidence offered by plaintiff-appellees and its setting aside of

7

the findings of the court below create confusion because Rule

52(a), when viewed in toe light of the Court’s precedents,

would seem to dictate a different result. Moreover, the Court

announces a test which is inconsistent with and destroys the

guidance provided by its earlier precedents.

In Miller v. Johnson, the Court allowed plaintiffs to

prove their case “either through circumstantial evidence of

district’s shape and demographics or more direct widen)

going to legislative purpose.” 515 U.S. 900, 916 (1995).

However, now the Court states that “where racial identification

correlates highly with political affiliation, the party attacking

the legislatively drawn boundaries must show at the least that

the legislature could have achieved its legitimate political

objectives in alternative ways that are comparably consistent

with traditional districting principles.” Easley, U.S.at

121 S.Ct. at 1466 (2001). Additionally, the plaintiffs must

show that “those districting alternatives would have brought

about significantly greater racial balance.” Id.

This test raises many questions. Does it apply if there

is direct evidence of motive or if the plaintiffs rely on both

direct evidence and circumstantial evidence? What is th

meaning of “racial balance?” That term was used by Senate

Cooper in addressing the North Carolina General Assembly;

and in that context it apparently meant “racial balance” among

the Representatives in Congress. In the Court’s opinion, the

term may have a quite different intent. Moreover, what greater

racial balance would be “significant” is also not specified.

More fundamentally, what are “legitimate political

objectives” in this context, and who defines them? Can those

objectives be defined post hoc or must they be set forth before

or at the time the General Assembly enacts the redistricting

plan? Is it a “legitimate political objective” to assure that the

person elected will be of a particular racial origin or is an

incumbent of a district previously held unconstitutional as a

racial gerrymander? For many activities “diversity” is cited as

8

an objective. The test announced by the Court leaves unclear

whether in the interest of “diversity” the legislature is free to

create districts that, because of their racial composition, are

almost certain to elect a prescribed number of African-

Americans from North Carolina. Finally, if the North Carolina

legislature had announced in 1997 that - without regard to race -

it was pleased with the results reached under the

unconstitutional 1992 Twelfth District and reenacted the

992 Plan verbatim so that the same Representatives would be

elected, would that be a “legitimate political objective?”

Plaintiff-appellees are unaware of any other group in

North Carolina that votes as cohesively as African-Americans.

Thus, creating the “safest” Democratic district necessarily

entails having as many African-Americans as possible in that

district. In short, use of race is the most certain means for

achieving the “political objective” of the “safe” Democratic

district, as well as the “political objective” of a Democratic

district represented by an African-American. The reference in

Bush v. Vera to the use of race as a “proxy” for politics would

seem to preclude this approach. 517 U.S. 952, 968

(1996)(O’Connor, J., plurality opinion). On the other hand, the

opinion of the Court now seems to treat these “political

@ ie as legitimate. Thus, blacks are used to create

certain types of districts in a way that no other group can be.

The manner in which the Court’s opinion deals with the

95% to 97% affiliation of African-Americans in North Carolina

with the Democratic Party is fundamentally different than its

approach in Shaw v. Hunt, where it rejected similar claims of

political objectives for the formation of the 1992 Plan’s Twelfth

District on the basis of direct evidence of racial intent. 517

U.S. 899, 907 (1996). Now, however, assuming the test would

apply to all cases where gerrymandering is attacked, if

defendants in Shaw had claimed that they adopted the 1992

Twelfth District in order to maximize the Democrat strength in

that area of North Carolina, that district could not successfully

9

be challenged, despite the direct evidence of the Justice

Department’s involvement and the District Court’s finding of

a specific racial target. Jd. at 905. Because of the high

correlation between race and party data, the Shaw plaintiffs

could not have come up with any hypothetical alternative

district which “would have better satisfied the legislature’s

other nonracial political goals as well as traditional nonracj

districting principles.” Easley, U.S.at 121 Sol

1462, and their challenge to that district would have failed.® As

a result, no district drawn anywhere in North Carolina, past,

present, or future, including the 1992 North Carolina

Congressional Twelfth District, could be successfully

challenged under the Court’s new test as the Court applies it.

Plaintiff-appellees see no reason for the Court to reject the

arguments of the state defendants in Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S.

899 (1996), only to adopt them wholesale in this case when

their consistent application would have rendered the 1992

Twelfth District immune from challenge. See Appellants’ Brief

at 38-40. Also in the other southern states which have, similar

SThus, if the defendants stated as a defense that they were iol)

the nonracial traditional redistricting goal of having a “super safe” district

with voting performance of over 70% for the Democratic candidate in the

1990 Senate Race, no other district besides one very similar to the 1992

Congressional District would be able to perform this task in the Piedmont

area of North Carolina - which coincedentally would be sure to elect an

African-American. However, if the purported political goal is a “very safe”

district that is confined to the six counties in which the 1997 Twelfth

district is located and has a voting performance of 65% for the Democratic

candidate in the 1990 Senate Race, it is not possible to accomplish this

without a district somewhat similar in shape to the 1997 Plan’s Twelfth

District. But, if the purported political goal is just to have a safe

Democratic district with a voting performance of 60% for the Democratic

candidate in the 1990 Senate race, the 1998 plan would accomplish the task.

Accordingly, the state defendants would be able to justify their desired

racial concentration, 55%, 47%, or 36%, respectively, merely by

proclaiming after the fact the political result they wanted for the district.

10

African-American bloc voting patterns that are more extreme

than any other group, it would be similarly difficult, if not

impossible, to challenge even the most blatantly race based

districts.

The conceptual problem with the Court’s new test is

that it seems to allow the state defendants to dictate after the

fact what its purported goals were and keep raising the bar. Cf

Appellees’ Brief at 16 n.15 (detailing the changing nature of the

@ goals for the Twelfth District as advanced by the

efendant-appellants). Eventually, the state could easily assert

enough criteria, real or fictional, that only one plan could satisfy

all of them, i.e. the plan under assault, no matter what its racial

purpose or result. Thus, in North Carolina, anyway, districts

that are blatant racial gerrymanders and cause the harms

described in Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993), would be

rendered immune from challenge.

CONCLUSION

In determining whether there was factual error in the

district court’s findings, the Court erroneously disregarded

persuasive evidence firmly supporting those findings.

Moreover, the Court’s opinion is at odds with its prior

ecedents and proposes a test that seems designed to preclude

almost any challenge in the federal courts to a racial

gerrymander, including those districts previously found

unconstitutional. North Carolina redistricting has been the

subject of four appeals; and the Court will undoubtedly be

pleased to turn to other matters. However, before doing so, the

Court should assure that a sound result is reached. Therefore,

a rehearing should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

AUS. 0. Lr

Robinson O. Everett, Attorney of Record

11

CERTIFICATE OF GOOD FAITH ARGUMENT:

Pursuant to Rule 44(1) of the Rules of the Supreme

Court of the United States, the undersigned counsel of record

hereby certifies that the above submitted Petition for Rehearing

is presented to the Court in good faith and not for delay or any

improper purpose. ®

This the 10" day of May, 2001.

: i

Robinson O. Everett

Appellees’ Attorney of Record

Everett & Everett

P.O. Box 586

Durham, NC 27702

(919) 682-5691