Jean v. Nelson Slip Opinion

Public Court Documents

June 26, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jean v. Nelson Slip Opinion, 1985. 9da5e722-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e77534e4-c135-4af1-adf3-d05e61f91cf7/jean-v-nelson-slip-opinion. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

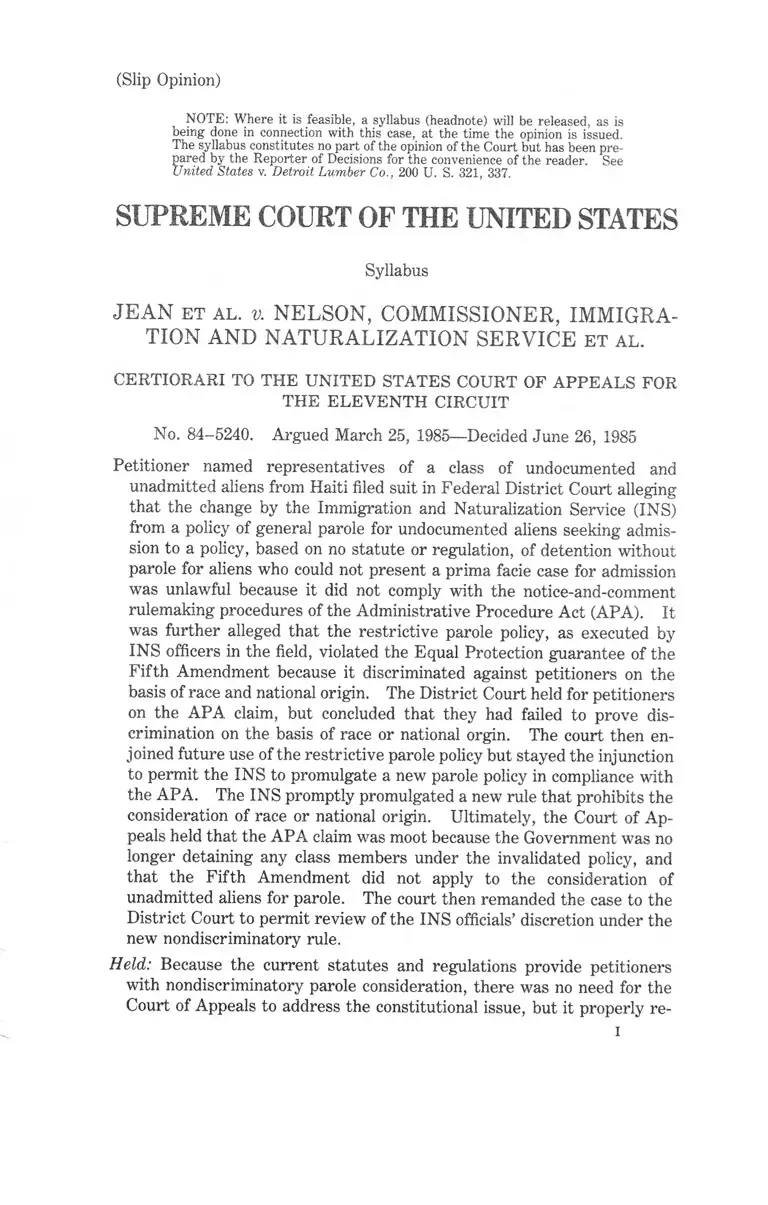

(Slip Opinion)

NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is

being done in connection with this ease, at the time the opinion is issued.

The syllabus const itutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been pre

pared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See

United States v. Detroit Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

JEA N e t a l . v. NELSON, COMMISSIONER, IMMIGRA

TION AND NATURALIZATION SERVICE e t a l .

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-5240. Argued March 25, 1985—Decided June 26, 1985

Petitioner named representatives of a class of undocumented and

unadmitted aliens from Haiti filed suit in Federal District Court alleging

that the change by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)

from a policy of general parole for undocumented aliens seeking admis

sion to a policy, based on no statute or regulation, of detention without

parole for aliens who could not present a prima facie case for admission

was unlawful because it did not comply with the notice-and-comment

rulemaking procedures of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). It

was further alleged that the restrictive parole policy, as executed by

INS officers in the field, violated the Equal Protection guarantee of the

Fifth Amendment because it discriminated against petitioners on the

basis of race and national origin. The District Court held for petitioners

on the APA claim, but concluded that they had failed to prove dis

crimination on the basis of race or national orgin. The court then en

joined future use of the restrictive parole policy but stayed the injunction

to permit the INS to promulgate a new parole policy in compliance with

the APA. The INS promptly promulgated a new rule that prohibits the

consideration of race or national origin. Ultimately, the Court of Ap

peals held that the APA claim was moot because the Government was no

longer detaining any class members under the invalidated policy, and

that the Fifth Amendment did not apply to the consideration of

unadmitted aliens for parole. The court then remanded the case to the

District Court to permit review of the INS officials’ discretion under the

new nondiscriminatory rule.

Held: Because the current statutes and regulations provide petitioners

with nondiscriminatory parole consideration, there was no need for the

Court of Appeals to address the constitutional issue, but it properly re-

I

II JEAN v. NELSON

Syllabus

manded the case to the District Court. On remand, the District Court

must consider (1) whether INS officials exercised their discretion under

the statute to make individualized parole determinations, and (2)

whether they exercised this discretion under the statutes and regula

tions without regard to race or national origin. Such remand protects

the class members from the very conduct they fear, and the fact that the

protection results from a regulation or statute, rather than from a con

stitutional holding, is a necessary consequence of the obligation of all fed

eral courts to avoid constitutional adjudication except where necessary.

Pp. 6-11.

727 F. 2d 957, affirmed.

Rehnquist, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which Burger,

C. J., and White, Blackmun, Stevens, and O’Connor, JJ., joined.

Marshall, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which Brennan, J., joined.

Powell, J., took no part in the decision of the case.

NOTICE: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in the

preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are requested to

notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the United States, Wash

ington, D. C. 20543, of any typographical or other formal errors, in order

that corrections may be made before the preliminary print goes to press.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 84-5240

MARIE LUCIE JEAN, e t a l ., PETITIONERS v. ALAN

NELSON, COMMISSIONER, IMMIGRATION AND

NATURALIZATION SERVICE e t a l .

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

[June 26, 1985]

J u st ic e R e h n q u ist delivered the opinion of the Court.

Petitioners, the named representatives of a class of undoc

umented and unadmitted aliens from Haiti, sued respondent

Commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service

(INS). They alleged, inter alia, that they had been denied

parole by INS officials on the basis of race and national ori

gin. See 711 F. 2d 1455 (CA11 1983) (panel opinion) (Jean

I). The en banc Eleventh Circuit concluded that any such

discrimination concerning parole would not violate the Fifth

Amendment to the United States Constitution because of the

Government’s plenary authority to control the Nation’s bor

ders. That court remanded the case to the District Court for

consideration of petitioners’ claim that their treatment vio

lated INS regulations, which did not authorize consideration

of race or national origin in determining whether or not an

excludable alien should be paroled. 727 F. 2d 957 (1984)

(Jean II). We granted certiorari 469 U. S .----- . We con

clude that the Court of Appeals should not have reached and

decided the parole question on constitutional grounds, but we

affirm its judgment remanding the case to the District Court.

Petitioners arrived in this country sometime after May

1981, and represent a part of the recent influx of undocu

mented excludable aliens who have attempted to migrate

from the Caribbean basin to South Florida. Section 235(b)

2 JEAN v. NELSON

of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, 66 Stat. 199,

8 U. S. C. § 1225(b), provides that “[ejvery alien . . . who

may not appear to the examining immigration officer at the

port of arrival to be clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to

land shall be detained for further inquiry to be conducted by a

special inquiry officer.” Section 212(d)(5)(A) of the Act, 66

Stat. 188, as amended, 8 U. S. C. §§ 1182(d)(5)(A), author

izes the Attorney General “in his discretion” to parole into

the United States any such alien applying for admission

“under such conditions as he may prescribe for emergent rea

sons or for reasons deemed strictly in the public interest.”

The statute further provides that such parole shall not be re

garded as an admission of the alien, and that the alien shall be

returned to custody when in the opinion of the Attorney Gen

eral the purposes of the parole have been served.

For almost 30 years before 1981, the INS had followed a

policy of general parole for undocumented aliens arriving on

our shores seeking admission to this country. In the late

1970’s and early 1980’s, however, large numbers of undocu

mented aliens arrived in South Florida, mostly from Haiti

and Cuba. Concerned about this influx of undocumented

aliens, the Attorney General in the first half of 1981 ordered

the INS to detain without parole any immigrants who could

not present a prima facie case for admission. The aliens

were to remain in detention pending a decision on their ad

mission or exclusion. This new policy of detention rather

than parole was not based on a new statute or regulation.

By July 31, 1981, it was fully in operation in South Florida.

Petitioners, incarcerated and denied parole, filed suit in

June 1981, seeking a writ of habeas corpus under 28 U. S. C.

§2241 and declaratory and injunctive relief. The amended

complaint set forth two claims pertinent here. First, peti

tioners alleged that the INS’ change in policy was unlawfully

effected without observance of the notice-and-comment rule-

making procedures of the Administrative Procedure Act

JEAN v. NELSON 3

(APA), 5 U. S. C. § 553. Petitioners also alleged that the re

strictive parole policy, as executed by INS officers in the

field, violated the equal protection guarantee of the Fifth

Amendment because it discriminated against petitioners on

the basis of race and national origin. Specifically, petition

ers alleged that they were impermissibly denied parole be

cause they were black and Haitian.

The District Court certified the class as “all Haitian aliens

who have arrived in the Southern District of Florida on or

after May 20, 1981, who are applying for entry into the

United States and who are presently in detention pending

exclusion proceedings . . . for whom an order of exclusion has

not been entered. . . .” Louis v. Nelson, 544 F. Supp. 1004,

1005 (SD Fla. 1982). A fter discovery and a 6-week bench

trial the District Court held for petitioners on the APA claim,

but concluded that petitioners had failed to prove by a pre

ponderance of the evidence discrimination on the basis of race

or national origin in the denial of parole. Louis v. Nelson,

544 F. Supp. 973 (1982); see also id., at 1004.

The District Court held that because the new policy of de

tention and restrictive parole was not promulgated in accord

ance with APA rulemaking procedures, the INS policy under

which petitioners were incarcerated was “null and void,” and

the prior policy of general parole was restored to “full force

and effect,” 544 F. Supp. at 1006. The District Court or

dered the release on parole of all incarcerated class members,

about 1,700 in number. See ibid. Additionally, the court

enjoined the INS from enforcing a rule of detaining

unadmitted aliens until the INS complied with the APA rule-

making process, 5 U. S. C. §§552, 553.

Under the District Court’s order, the INS retained the dis

cretion to detain unadmitted aliens who were deemed a secu

rity risk or likely to abscond, or who had serious mental

or physical ailments. The court’s order also subjected the

paroled class members to certain conditions, such as compli

4 JEAN v. NELSON

ance with the law and attendance at required INS proceed

ings. The court retained jurisdiction over any class member

whose parole might be revoked for violating the conditions of

parole.

Although all class members were released on parole forth

with, the District Court imposed a 30-day stay upon its order

enjoining future use of the INS’ policy of incarceration with

out parole policy. The purpose of this stay was to permit the

INS to promulgate a new parole policy in compliance with the

APA. The INS promulgated this new rule promptly. See 8

CFR §212.5 (1985); 47 Fed. Reg. 30045 (July 9, 1982), as

amended, 47 Fed. Reg. 46494 (Oct. 19, 1982). Both petition

ers and respondents agree that this new rule requires even-

handed treatment and prohibits the consideration of race and

national origin in the parole decision. Except for the initial

30-day stay, the District Court’s injunction against the prior

INS policy ended the unwritten INS policy put into place in

the first half of 1981. Some 100 to 400 members of the class

are currently in detention; most of these have violated the

terms of their parole but some may have arrived in this coun

try after the District Court’s judgment.1 It is certain, how

ever, that no class member is being held under the prior INS

policy which the District Court invalidated. See Jean II,

727 F. 2d, at 962.

A fter the District Court entered its judgment respondents

appealed the decision on the APA claim and petitioners cross-

appealed the decision on the discrimination claim. A panel

of the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the Dis

trict Court’s judgment on the APA claim, although on a

1 The record does not inform us of exactly how many class members are

in detention, and whether these are post-judgment arrivals or original

class members who violated the terms of their parole as set by the District

Court. The precise make-up of the class may be addressed on remand.

See Tr. of Oral Arg. 42; Jean II, 727 F. 2d at 962; Order on Mandate, Louis

v. Nelson, No. 81-1260, p. 1, n. 1 (SD Fla. June 8, 1984); Record, Vol. 17,

pp. 4014, 4026, 4035.

JEAN v. NELSON 5

somewhat different rationale than the District Court. Jean

1, 711 F. 2d, at 1455. The panel went on to decide the con

stitutional discrimination issue as well, holding that the Fifth

Amendment’s equal protection guarantee applied to parole of

unadmitted aliens, and the District Court’s finding of no in

vidious discrimination on the basis of race or national origin

was clearly erroneous. The panel ordered, inter alia, con

tinued parole of the class members, an injunction against

discriminatory enforcement of INS parole policies, and any

further relief necessary “to ensure that all aliens, regardless

of their nationality or origin, are accorded equal treatm ent.”

Id., at 1509-1510.

The Eleventh Circuit granted a rehearing en banc, thereby

vacating the panel opinion. See 11th Cir. Ct. Rule 26(k).

A fter hearing argument the en banc court held that the APA

claim was moot, because the Government was no longer de

taining any class members under the stricken incarceration

and parole policy.2 All class members who were incarcer

ated had either violated the terms of their parole or were

postjudgment arrivals detained under the regulations

adopted after the District Court’s order of June 29, 1982.

Jean II, supra, at 962. The en banc court then turned to the

constitutional issue and held that the Fifth Amendment did

not apply to the consideration of unadmitted aliens for parole.

According to the court the grant of discretionary authority to

the Attorney General under 8 U. S. C. § 1182(d)(5)(A) per

mitted the Executive to discriminate on the basis of national

origin in making parole decisions.

Although the court in Jean II rejected petitioners’ con

stitutional claim, it accorded petitioners relief based upon the

current INS parole regulations, see 8 CFR §212.5 (1985),

which are facially neutral and which respondents and peti

tioners admit require parole decisions to be made without re

2 The APA issue is not before us and we express no view on it. The

court in Jean II was presented with other issues, none germane to the

issues we discuss today.

6 JEAN v. NELSON

gard to race or national origin. Because no class members

were being detained under the policy held invalid by the Dis

trict Court, the en banc court ordered a remand to the Dis

trict Court to permit a review of the INS officials’ discretion

under the non-discriminatory regulations which were pro

mulgated in 1982 and are in current effect. The court stated:

“[t]he question that the district court must therefore

consider with regard to the remaining Haitian detainees

is thus not whether high-level executive branch officials

such as the Attorney General have the discretionary

authority under the Immigration and Nationality Act

(INA) to discriminate between classes of aliens, but

whether lower-level INS officials have abused their dis

cretion by discriminating on the basis of national origin

in violation of facially neutral instructions from their

superiors.” Jean II, supra, at 963.

The court stated that the statutes and regulations, as well

as policy statements of the President and the Attorney Gen

eral, required INS officials to consider aliens for parole indi

vidually, without consideration of race or national origin.

Thus on remand the District Court was to ensure that the

INS had exercised its broad discretion in an individualized

and nondiscriminatory manner. See id., at 978-979.

The court noted that the INS’ power to parole or refuse pa

role, as delegated by Congress in the United States Code,

e. g. 8 U. S. C. §§ 1182(d)(5)(A), 1225(b), 1227(a), was quite

broad. 727 F. 2d, at 978-997. The court held that this

power was subject to review only on a deferential abuse of

discretion standard. According to the court “immigration

officials clearly have the authority to deny parole to

unadmitted aliens if they can advance a ‘facially legitimate

and bona fide reason’ for doing so.” Jean II, supra, at 977,

citing Kleindienst v. Mandel, 408 U. S. 753, 770 (1972).

The issue we must resolve is aptly stated by petitioners:

JEAN v. NELSON 7

“This Case does not implicate the authority of Con

gress, the President, or the Attorney General. Rather,

it challenges the power of low-level politically unrespon

sive government officials to act in a manner which is con

trary to federal statutes . . . and the directions of the

President and the Attorney General, both of whom pro

vided for a policy of non-discriminatory enforcement.”

Brief for Petitioners 37.

Petitioners urge that low-level INS officials have invidi

ously discriminated against them, and notwithstanding the

new neutral regulations and the statutes, these low-level

agents will renew a campaign of discrimination against the

class members on parole and those members who are cur

rently detained. Petitioners contend that the only adequate

remedy is “declaratory and injunctive relief” ordered by this

Court, based upon the Fifth Amendment. The limited statu

tory remedy ordered by the court in Jean II, petitioners con

tend, is insufficient. For its part respondents are also eager

to have us reach the Fifth Amendment issue. Respondents

wish us to hold that the equal protection component of the

Fifth Amendment has no bearing on an unadmitted alien’s re

quest for parole.

“Prior to reaching any constitutional questions, federal

courts must consider nonconstitutional ground for decision.”

Gulf Oil v. Bernard, 452 U. S. 89, 99 (1981); Mobile v.

Bolden, 446 U. S. 55, 60 (1980); Kolender v. Lawson, 461

U. S. 352, 361, n. 10 (1983), citing Ashwander v. TV A, 297

U. S. 288, 347 (1936) (Brandeis, J ., concurring). This is a

“fundamental rule of judicial restraint.” Three Affiliated

Tribes of Berthold Reservation v. Wold Engineering, 467

U. S .----- (1984). Of course, the fact that courts should not

decide constitutional issues unnecessarily does not permit a

court to press statutory construction “to the point of

disengenuous evasion” to avoid a constitutional question.

United States v. Locke, ----- U. S. -------(1985), slip op. at

10-11. As the Court stressed in Spector Motor Co. v.

8 JEAN v. NELSON

McLaughlin, 323 U. S. 101, 105 (1944), “[i]f there is one doc

trine more deeply rooted than any other in the process of con

stitutional adjudication, it is that we ought not to pass on

questions of constitutionality . . . unless such adjudication is

unavoidable.” See also United States v. Gerlach Livestock

Co., 339 U. S. 725, 737 (1950); Larson v. Valente, 456 U. S.

228, 257 (1982) (St e v e n s , J ., concurring).

Had the court in Jean II followed this rule, it would have

addressed the issue involving the immigration statutes and

INS regulations first, instead of after its discussion of the

Constitution. Because the current statutes and regulations

provide petitioners with nondiscriminatory parole consider

ation—which is all they seek to obtain by virtue of their

constitutional argument—there was no need to address the

constitutional issue.

Congress has delegated its authority over incoming undoc

umented aliens to the Attorney General through the Immi

gration and Naturalization Act, 8 U. S. C. § 1101, et seq.

The Act provides that any alien “who [upon arrival in the

United States] may not appear to [an INS] examining officer

. . . to be clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to land” is to be

detained for examination by a special inquiry officer or immi

gration judge of the INS. 8 U. S. C. §§ 1225(b), 1226(a)

(1985); see 8 CFR §236.1 (1985). The alien may request pa

role pending the decision on his admission. Under 8

U. S. C. § 1182(d)(5)(A):

“[t]he Attorney General may . . . parole into the United

States temporarily under such conditions as he may pre

scribe for emergent reasons or for reasons deemed

strictly in the public interest any alien applying for

admission to the United States.”

The Attorney General has delegated his parole authority to

his INS District Directors under new regulations promul

gated after the District Court’s order in this case. See 8

CFR § 212.5 (1982). Title 8 CFR §212.5 provides a lengthy

list of neutral criteria which bear on the grant or denial of pa

JEAN v. NELSON 9

role. Respondents concede that the INS’ parole discretion

under the statute and these regulations, while exceedingly

broad, does not extend to considerations of race or national

origin. Respondent’s position can best be seen in this collo

quy from oral argument:

Question: “You are arguing that constitutionally you

would not be inhibited from discriminating against these

people on whatever ground seems appropriate. But as I

understand your regulations, you are also maintaining

that the regulations do not constitute any kind of dis

crimination against these people, and . . . your agents

are already inhibited by your own regulations from doing

what you say the Constitution would permit you to do.”

Solicitor General: “That’s correct.”

Transcript of Oral Argument at 28—29. See also Brief for

Respondents 18-19; 8 U. S. C. § 1182(d)(5)(A); 8 CFR §212.5

(1982); cf., Statement of the President, U. S. Immigration

and Refugee Policy (July 31, 1981). As our dissenting col

leagues point out, ante at 6, the INS has adopted nationality-

based criteria in a number of regulations. These criteria are

noticeably absent from the parole regulations, a fact consist

ent with the position of both respondent and petitioner that

INS parole decisions must be neutral as to race or national

origin.3 * * *

3 We have no quarrel with the dissent’s view7 that the proper reading of

important statutes and regulations may not be always left to the stipulation

of the parties. But when all parties, including the agency which wrote and

enforces the regulations, and the en banc court below, agree that regula

tions neutral on their face must be applied in a neutral manner, we think

that interpretation arrives with some authority in this Court.

The dissent relies upon such cases as Young v. United States, 315 U. S.

257, 259 (1942) and Investment Co. v. Camp, 401 U. S. 617 (1970) even

though those cases have faint resemblance to this one. In Young the gov

ernment confessed error, arguing that the Court of Appeals was wrong in

its affirmance of a conviction under a broad reading of the Harrison Anti-

Narcotics Act. Because of the importance of a consistent interpretation of

criminal statutes, we declined to adopt the Solicitor General’s view, and

10 JEAN v. NELSON

Accordingly, we affirm the en banc court’s judgment inso

far as it remanded to the District Court for a determination

whether the INS officials are observing this limit upon their

broad statutory discretion to deny parole to class members

in detention. On remand the District Court must consider:

(1) whether INS officials exercised their discretion under

§ 1182(d)(5)(A) to make individualized determinations of pa

role, and (2) whether INS officials exercised this broad dis

cretion under the statutes and regulations without regard to

race or national origin.

Petitioners protest, however, that such a nonconstitutional

remedy will permit lower-level INS officials to commence pa

role revocation and discriminatory parole denial against class

members who are currently released on parole. But these

officials, while like all others bound by the provisions of the

Constitution, are just as surely bound by the provisions of

the statute and of the regulations. Respondents concede

that the latter do not authorize discrimination on the basis of

race and national origin. These class members are therefore

protected by the terms of the Court of Appeals’ remand from

the very conduct which they fear. The fact that the protec

tion results from the terms of a regulation or statute, rather

reject the Circuit Court’s interpretation, without ourselves considering

and deciding the merits of the question. See 315 U. S. at 258—259.

Young has little bearing on the interpretation of the INS regulations at

issue today.

In Camp the Solicitor General attempted to defend a banking regulation

promulgated by the Comptroller, which was in apparent conflict with fed

eral banking statutes. We rejected the gloss place upon these statutes by

the Solicitor General on appeal; the Comptroller had offered no pre-litiga

tion administrative interpretation of these statutes and the Solicitor Gener

al’s post-hoc interpretation could not cure the conflict between the chal

lenged regulation and the statutes.

The interpretation of INS regulations we adopt today involves no post-

hoc rationalizations of agency action. Unlike the Court in Camp we do not

view the new INS policy or the interpretation of that policy agreed to by all

parties and the en banc Circuit Court to be merely a litigation stance in

defense of the agency action which precipitated this litigation.

JEAN v. NELSON 11

than from a constitutional holding, is a necessary conse

quence of the obligation of all federal courts to avoid constitu

tional adjudication except where necessary.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals remanding the case

to the District Court for consideration of petitioner’s claims

based on the statute and regulations is

Affirmed.

J u st ic e P o w ell took no part in the decision of this case.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 84-5240

MARIE LUCIE JEAN, ET AL., PETITIONERS v. ALAN

NELSON, COMMISSIONER, IMMIGRATION AND

NATURALIZATION SERVICE, ET AL.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

[June 26, 1985]

J u st ic e Ma r sh a l l , w ith whom J u st ic e B r e n n a n joins,

dissenting.

Petitioners are a class of unadmitted aliens who were

detained at various federal facilities pending the disposition

of their asylum claims. We granted certiorari to decide

whether such aliens may invoke the equal protection guaran

tees of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause to chal

lenge the Government’s failure to release them temporarily

on parole. The Court today refuses to address this question,

invoking the well-accepted proposition that constitutional

issues should be avoided whenever there exist proper non

constitutional grounds for decision. I, of course, have no

quarrel with that proposition. Its application in this case,

however, is more than just problematic; by pressing a regula

tory construction well beyond “the point of disingenuous eva

sion,” United States v. Locke, 471 U. S. ----- , ------(1985)

(slip. op. 10-11), the Court thrusts itself into a domain that is

properly that of the political branches. Purporting to exer

cise restraint, the Court creates out of whole cloth noncon

stitutional constraints on the Attorney General’s discretion to

parole aliens into this country, flagrantly violating the maxim

that “amendment may not be substituted for construction,”

Yu Cong Eng v. Trinidad, 271 U. S. 500, 518 (1926) (Taft,

C. J.). In my mind, there is no principled way to avoid

2 JEAN v. NELSON

reaching the constitutional question presented by the case.

Turning to that question, I would hold that petitioners have

a Fifth Amendment right to parole decisions free from invidi

ous discrimination based on race or national origin. I

respectfully dissent.

I

The Court’s decision rests entirely on the premise that the

parole regulations promulgated during the course of this liti

gation preclude INS officials from considering race and na

tional origin in making parole decisions. Ante, at 5-6, 9.

The Court then reasons that if petitioners can show disparate

treatm ent based on race or national origin, these regulations

would provide them with all the relief that they seek. Thus,

it sees no need to address the independent question whether

such disparate treatment would also violate the Constitution,

and invokes Ashwander v. TV A, 297 U. S. 288, 347 (1936)

(Brandeis, J ., concurring), to avoid deciding that question.

If the initial premise were correct, the Court’s decision would

be sound. But because it is not, the remainder of the Court’s

opinion simply collapses like a house of cards.

In support of its conclusion, the Court points to no author

ity other than arguments in the parties’ briefs, which in turn

cite nothing of relevance. The Court’s failure to rely on any

other authority is not surprising, for an examination of the

regulations themselves, as well as the statutes and adminis

trative practices governing the parole of unadmitted aliens,

indicates that there are no nonconstitutional constraints

on the Executive’s authority to make national-origin

distinctions.1

1 That the analysis would be different for race discrimination in no way

detracts from the force of my argument. Petitioners complain in part

about differential treatment based on national origin. Because neither the

statute nor the regulations prohibit nationality distinctions, the Court errs

in failing to address petitioners’ constitutional arguments, at least insofar

as they pertain to national-origin discrimination.

JEAN v. NELSON 3

A

Congress provided for the temporary parole of unadmitted

aliens in § 212(d)(5) of the Immigration and Nationality Act of

1952, 66 Stat. 188, as amended, 8 U. S. C. § 1182(d)(5)(A),

which states in pertinent part that the Attorney General may

“in his discretion parole into the United States temporarily

under such conditions as he may prescribe for emergent rea

sons or for reasons deemed strictly in the public interest any

alien applying for admission to the United States.” (emphasis

added). Pursuant to this statute, the INS promulgated

regulations in 1958, in which the Attorney General’s dis

cretionary authority was delegated to INS district directors:

“The district director in charge of a port of entry may

. . . parole into the United States temporarily in accord

ance with section 212(d)(5) of the act any alien applicant

for admission . . . as such officer shall deem appropri

a t e . 23 Fed. Reg. 142 (1958); see 8 CFR §212.5 (1959)

(emphasis added).

The quoted portion of the regulations remained unchanged in

1982, at the time of the trial in this case. See 8 CFR §212.5

(1982).

The District Court found that between 1954 and 1981 most

undocumented aliens detained at the border were paroled

into the United States. Louis v. Nelson, 544 F. Supp. 973,

980, n. 18, 990 (SD Fla. 1982); see Brief for Respondents 3.

During that period, physical detention was the exception, not

the rule, and was “generally employed only as to security

risks or those likely to abscond,” Leng May Ma v. Barber,

357 U. S. 185, 190 (1958). See 544 F. Supp., at 990.

As the Court acknowledges, the Government’s parole pol

icy became far more restrictive in 1981. See ante, at 2. In

June 1982, the District Court below enjoined enforcement of

this new policy. Louis v. Nelson, 544 F. Supp. 1004, 1006

(final judgment). The District Court found that the INS had

4 JEAN v. NELSON

not complied with the Administrative Procedure Act (APA),

5 U. S. C. §553, as it had not published notice of the pro

posed change and had not allowed interested persons to com

ment. See 544 F. Supp., at 997. As a result of the District

Court’s judgment, the INS promulgated new regulations in

July 1982. See 47 Fed. Reg. 30044 (1982); 8 CFR §212.5

(1982). According to the Court, these regulations, on which

this case turns, provide a “lengthy list of neutral criteria

which bear on the grant or denial of parole.” Ante, at 8-9.

The new parole regulations track the two statutory stand

ards for the granting of parole: “emergent reasons” and “rea

sons strictly in the public interest.” They first provide that

“[t]he parole of aliens who have serious medical conditions in

which continued detention would not be appropriate would

generally be justified by ‘emergent reasons.’” 8 CFR

§ 212.5(a)(1) (1985). The regulations then define five groups

that would “generally come within the category of aliens for

whom the granting of the parole exception would be ‘strictly

in the public interest’, provided that the aliens present nei

ther a security risk nor a risk of absconding.” §212.5(a)(2).

The first four groups are pregnant women, juveniles, certain

aliens who have close relatives in the United States, and

aliens who will be witnesses in official proceedings in the

United States. §212.5(a)(2)(i)-(iv). The fifth category is

a catchall: “aliens whose continued detention is not in the

public interest as determined by the district director.”

§212.5(a)(2)(v).2

Given the catchall provision, the regulations provide some

what tautologically that it would generally be “strictly in the

public interest” to parole aliens whose continued detention is

not “in the public interest”; the “lengthy list” of criteria on

which the Court relies so heavily is in fact an empty set.3

2 The regulations also provide for the parole of aliens who are subject to

prosecution in the United States. 8 CFR § 212.5(a)(3) (1985).

3 To be sure, a district director cannot parole an alien under 8 CFR

§ 212.5(a)(2) unless he determines that the alien “present[s] neither a seen-

JEAN v. NELSON 5

Certainly the regulations do not provide either exclusive cri

teria to guide the the “public interest” determination or a list

of impermissible criteria. Moreover, they do not, by their

terms, prohibit the consideration of race or national origin.

As Judge Tjoflat aptly noted in his separate opinion below:

“The policy in CFR is not a comprehensive policy . . . .

It merely sets out a few specific categories of aliens . . .

who the district director generally should parole in the

absence of countervailing security risks. It leaves the

weighing necessary to making parole decisions regarding

these categories, as well as all other parole decisions,

purely in the discretion of the district director. Such a

minimal directive is not enough to infer with any cer

tainty that the Attorney General never wants district

directors, in making parole decisions, to consider nation

ality.” 727 F. 2d 957, 985-986 (1984) (concurring in part

and dissenting in part) (emphasis added).

B

Nor is a prohibition on the consideration of national origin

to be found in the parole statute, pronouncements of the At

torney General and the INS, or the Administrative Proce

dure Act (APA), the only other possible nonconstitutional

sources for the constraints the Court believes are imposed

upon INS’s district directors. The first potential constraint,

of course, is 8 U. S. C. § 1182(d)(5)(A), which vests full “dis

cretion” over parole decisions in the Attorney General.

There can be little doubt that at least national-origin distinc

tions are permissible under the parole statute if they are con

sistent with the Constitution. First, the grant of discretion

ary authority to the Attorney General over immigration

rity risk nor a risk of absconding.” This condition, which has been a tradi

tional prerequisite to parole, Leng May Ma v. Barber, 357 U. S. 185, 190

(1958), merely requires the district director to make a threshold deter

mination before he exercises his discretion. It is of no aid to the subse

quent inquiry of defining the “public interest.”

6 JEAN v. NELSON

matters is extremely broad. See 2 K. Davis, Administrative

Law Treatise §8:10 (2d ed. 1979); 2 C. Gordon & H. Rosen-

field, Immigration Law and Procedure § 8.14 (1985). For ex

ample, in Hintopoulos v. Shaughnessy, 353 U.. S. 72 (1957),

this Court held that, where Congress does not specify the

standards that are to guide the Attorney General’s exercise

of discretion in the immigration field, the Attorney General

can rely on any reasonable factors of his own choosing. Id .,

at 78.

Moreover, with respect to other immigration matters in

which Congress has vested similar discretion in the Attorney

General, the INS, acting pursuant to authority delegated by

the Attorney General, has specifically adopted nationality-

based criteria. See, e. g., 8 CFR §101.1 (1985) (presump

tion of lawful admission for certain national groups); §212.1

(documentary requirements for nonimmigrants of particular

nationalities); §231 (arrival-departure manifests for passen

gers from particular countries); § 242.2(e) (nationals of cer

tain countries entitled to special privilege of communication

with diplomatic officers); §252.1 (relaxation of inspection

requirements for certain British and Canadian crewmen).

These regulations indicate that the INS believes that nation

ality-based distinctions are not necessarily inconsistent with

congressional delegation of “discretion” over immigration de

cisions to the Executive. That interpretation of the statutes

is, of course, entitled to deference. See Chevron U. S. A.

Inc. v. NRDC, 467 U. S . ----- , ------(1984).

My conclusion that the parole statute leaves room for na

tionality-based distinctions is consistent with the Govern

ment’s position before the en banc Court of Appeals. The

brief filed by Assistant Attorney General McGrath in that

court explicitly stated that “the Executive is not precluded

from drawing nationality-based distinctions, for Congress

has delegated the full breadth of its parole and detention

authority to the Attorney General.” En Banc Brief of Alan

C. Nelson in No. 82-5772 (CA11 1983), p. 18. In maintain

JEAN v. NELSON 7

ing that the parole statute does not proscribe differential

treatm ent based on national origin, the Government added:

“Congress knows how to prohibit nationality-based dis

tinctions when it wants to do so. In the absence of such

an express prohibition, it should be presumed that the

broad delegation of authority encompasses the power to

make nationality-based distinctions.” En Banc Reply

Brief of Alan C. Nelson in No. 82-5772 (CA11 1983),

p. 11.

The conclusion that Congress did not provide the con

straint identified by the Court does not end the inquiry, as

the Attorney General could have narrowed the discretion

that the regulations vest in the district directors. For exam

ple, he could have published interpretive rules, staff instruc

tions, or policy statements making clear that this discretion

did not extend to race or national-origin distinctions. But

throughout this litigation, the Government has pointed to ab

solutely no evidence that the Attorney General in fact chose

to narrow the discretion of district directors in this manner.

Moreover, neither the INS’s Operations Instructions nor its

Examinations Handbook, which provide guidance to INS offi

cers in the field, indicate that race and national origin cannot

be taken into account in making parole decisions.

The final possible constraint comes from the APA’s re

quirement that administrative action not be arbitrary, capri

cious, or an abuse of discretion, 5 U. S. C. § 706(2)(A). See

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U. S. 402,

411 (1971); Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner, 387 U. S. 136,

140-141 (1967). For better or worse, however, nationality

classifications have played an important role in our immigra

tion policy. There is thus no merit to the argument that it is

arbitrary, capricious, or an abuse of discretion for a district

director to take nationality into account in making parole de

cisions under 8 CFR §212.5 (1985). See also supra, a t -----

(discussing Attorney General’s discretion). In summary,

the Court’s conclusion that, aside from constitutional con

JEAN v. NELSON

straints, the parole regulations prohibit national-origin dis

tinctions draws no support from anything in the regulations

themselves or in the statutory and administrative back

ground to those regulations.

C

The Court’s view that the regulations are neutral with re

spect to race and national origin is based only on the repre

sentations of the Solicitor General and the purported agree

ment of the parties.4 On the first point, the Court states:

“Respondents concede that the INS’ parole discretion under

the statute and these regulations, while exceedingly broad,

does not extend to considerations of race or national origin.”

Ante, at 9. Such reliance on the Solicitor General’s interpre

tation of agency regulations is misplaced.

An agency’s reasonable interpretation of the statute it is

empowered to administer is entitled to deference from the

courts, and will be set aside only if it is inconsistent with

the clear intent of Congress. See Chevron U. S. A. Inc. v.

NRDC, 467 U. S., a t ----- . Similarly, an agency’s interpre

tation of its own regulations is of “controlling weight unless it

is plainly erroneous or inconsistent with the regulation.”

Bowles v. Seminole Rock & Sand Co., 325 U. S. 410, 414

(1945); see Ford Motor Credit Co. v. Milhollin, 444 U. S.

555, 566 (1980); United States v. Larionoff, 431 U. S. 864,

872 (1977). These presumptions do not apply, however, to

representations of appellate counsel. As we stated in

Investment Company Institute v. Camp, 401 U. S. 617

(1971), “Congress has delegated to the administrative official

and not to appellate counsel the responsibility for elaborating

and enforcing statutory commands. It is the administrative

“The Court also appears to share the Court of Appeals’ misconception

that the new regulations somehow changed the substantive standards for

parole. By the INS’s own admission, however, those regulations merely

“sought to codify existing Service practices.” See 47 Fed. Reg. 46494

(1982).

JEAN v. NELSON 9

official and not appellate counsel who possess the expertise

that can enlighten and rationalize the search for the meaning

and intent of Congress.” Id., at 628; see Motor Vehicle

Mfrs. Assn. v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance

Co., 463 U. S. 29, 50 (1983); Burlington Truck Lines Inc. v.

United States, 371 U. S. 156, 168-169 (1962). The same con

siderations apply, of course, to appellate counsel’s interpreta

tion of regulations.

The Solicitor General’s representations to this Court are

not supported by citation to any authoritative statement by

the Attorney General or the INS to the effect that the statute

and regulations prohibit distinctions based on race or national

origin. See Brief for Respondents 18-19. Indeed, “except

for some too-late formulations, apparently coming from the

Solicitor General’s office,” Citizens to Preserve Overton Park

v. Volpe, 401 U. S., at 422 (opinion of Black, J.), we have

been directed to no relevant indication that the adminis

trative practice was to prohibit such distinctions.5 See

supra, at — —. The Solicitor General’s contention to the

contrary is merely an unsupported assertion by counsel for a

litigant; this Court owes it no deference at all.6

5 The Court’s conclusion that the Solicitor General’s statements are not

mere “post-hoc rationalizations for agency action,” ante 9, n. 6, is untena

ble. Before this Court, the Solicitor General argues that the INS is pre

cluded by the statute and regulations from making nationality-based dis

tinctions. At trial, however, the Government argued the opposite,

namely that “nationality may well be a factor that leads to parole.”

Record, Vol. 47, p. 1858. Because the substantive criteria for parole have

not changed during the course of this litigation, see n. 4, supra, the Solici

tor General’s representations are flatly inconsistent with the Government’s

own position at trial; they reflect nothing but a change in the Government’s

litigation strategy. This is precisely the sort of post-hoc rationalization

that is entitled to no weight. See Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Assn. v. State

Farm. Mutual Automobile Insurance Co., 463 U. S. 23, 50 (1983).

6 At trial, one Government witness, Associate Attorney General Giuli

ani, stated that “if the statute is being applied discriminatorily, it is being

applied in violation of the policies of the Attorney General.” Id., Vol. 49,

p. 2343. This witness, however, did not indicate what he meant by “dis

10 JEAN v. NELSON

The Court also relies on the purported agreement between

petitioners and the Solicitor General that the regulations

require parole decisions to be made without regard to race or

national origin. Ante, at 5-6. First, I do not read petition

ers’ arguments as the Court does. In my mind, the main

thrust of the relevant portion of petitioners’ brief is that the

regulations in question set out neutral criteria for parole.

See Brief for Petitioners 7-10, 30, 37, 38. Unless such crite

ria are exclusive, however, they are not necessarily inconsist

ent with distinctions based on race or national origin. Cer

tainly no plausible argument can be made that the criteria of

8 CFR § 212.5(a) (1985) were intended to be exclusive. See

supra, a t ----- .

More importantly, this Court’s judgments are precedents

binding on the lower courts. Thus, the proper interpreta

tion of an important federal statute and regulations, such as

are at issue here, cannot be left merely to the stipulation of

parties. See Young v. United States, 315 U. S. 257, 259

(1942); see also Sibron v. New York, 392 U. S. 40, 59 (1968).

crimination,” and did not point to any specific “policies.” To the extent

that he was referring to distinctions based on national origin, his statement

was inconsistent with the Government’s own theory. See n. 5, supra.

Moreover, the District Court found “inconsistencies between what the

Government witnesses said the policy was and the policy their subordi

nates were carrying out,” as a result of “the absence of guidelines for

detention and parole.” Louis v. Nelson, 544 F. Supp. 973, 981, n. 24

(1982). Similarly, the panel of the Court of Appeals properly found that

Associate Attorney General Giuliani’s testimony contradicted the testi

mony of INS Commissioner Alan C. Nelson, one of the respondents in this

case, as well as statements by former INS Commissioner Doris Meissner.

711 F. 2d 1455, 1471 (1983). The unsupported, uncredited, and contra

dicted assertions of one Government witness are of course insufficient to

establish the existence of an administrative practice. Not surprisingly,

the Government does not direct this Court’s attention to that testimony.

Finally, the Government’s position at trial that it had not in fact treated

Haitians differently from other detained aliens sheds no light on the en

tirely separate question of whether different treatment would have been

inconsistent with the statutes and regulations.

JEAN v. NELSON 11

The Court’s construction of the administrative policy in this

case will have implications far beyond the confines of this

litigation.7

In fact, the Court’s decision casts serious doubt on the va

lidity of numerous immigration policies. As I have already

mentioned, many statutes in the immigration field vest “dis

cretion” in the Attorney General. The Court’s restrictive

view of the Attorney General’s discretionary authority with

respect to parole decisions, adopted in the face of no authori

tative statements limiting such discretion, will presumably

affect the scope of his permissible discretion in areas other

than parole decisions. Moreover, because the Court does

not explain what in the language or policy underlying any rel

evant statute, regulation, or administrative practice, limits

the Attorney General’s discretion only with respect to the

consideration of race and national origin, its opinion can be

read to preclude the Attorney General from making distinc

tions based on other factors as well. Such a result is incon

sistent with well-established precedents of immigration law

and threatens to constrain severely the Executive’s ability to

address our Nation’s pressing immigration problems. This

is indeed a costly way to avoid deciding constitutional issues.

See supra, at 1.

II

Having shown that the Court’s interpretation of the regu

lations is untenable, I turn to consider the constitutional

question presented by this case: May the Government dis

criminate on the basis of race or national origin in its decision

whether to parole unadmitted aliens pending the determina

tion of their admissibility? The en banc Court of Appeals

rejected petitioners’ constitutional claim, holding that

Shaughnessy v. United States ex rel. Mezei, 345 U. S. 206

7 In addition, the Court cites the President’s statement on United States

Immigration and Refugee Policy (17 Weekly Comp, of Pres. Doc. 829

(1981)). Nothing in that statement is relevant to the question whether na

tional-origin distinctions are consistent with the statute and regulations.

12 JEAN v. NELSON

(1953), compels the conclusion that petitioners “cannot claim

equal protection rights under the fifth amendment, even with

regard to challenging the Executive’s exercise of its parole

discretion.” 727 F. 2d, at 970.8 Before this Court, the Gov

ernment takes the same position, arguing that “Mezei is di

rectly on point.” Brief for Respondents 40. I agree that

broad dicta in Mezei might suggest that an undocumented

alien detained at the border does not enjoy any constitutional

protections, and therefore cannot invoke the equal protection

guarantees of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

See also United States ex rel. Knauff v. Shaughnessy, 33S

U. S. 537, 544 (1950); Kwong Hai Chew v. Colding, 344 U. S.

590, 601 (1953). This broad dicta, however, can withstand

neither the weight of logic nor that of principle, and has

never been incorporated into the fabric of our constitutional

jurisprudence. Moreover, when stripped of its dicta, Mezei

stands for a narrow proposition that is inapposite to the case

now before the Court.

A

Ignatz Mezei arrived in New York in 1950 and was tempo

rarily excluded from the United States by an immigration in

spector acting pursuant to the Passport Act. Pending dispo

sition of his application for admission, he was detained at

Ellis Island. A few months after his arrival and initial

detention, the Attorney General entered a permanent order

of exclusion, on the “basis of information of a confidential

8 The Court of Appeals acknowledged that its holding was squarely at

odds with the holding of the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit in

Rodriguez-Femandez v. Wilkinson, 654 F. 2d 1382 (1981). See 727 F. 2d,

at 974-975. Moreover, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit has

suggested that unadmitted aliens can invoke the protections of the Con

stitution. See Augustin v. Sava, 735 F. 2d 32, 37 (1984) (“it appears likely

that some due process protection surrounds the determination of whether

an alien has sufficiently shown that return to a particular country will jeop

ardize his life or freedom”); Yiu Sing Chun v. Sava, 708 F. 2d 869, 877

(1983) (a refugee’s “interest in not being returned may well enjoy some due

process protection”).

JEAN v. NELSON 13

nature, the disclosure of which would be prejudicial to the

public in te res t . . . for security reasons.” 345 U. S., at 208.

Mezei was not told what this information was and was given

no opportunity to present evidence of his own.

Mezei then began a year-long search for a country willing

to accept him. All of his attempts to find a new home failed,

however, as did the State Department’s efforts on his behalf.

As a result, Mezei “sat on Ellis Island because this country

shut him out and others were unwilling to take him in.” Id.,

at 209.

Seeking a w rit of habeas corpus, Mezei argued that the

Government’s refusal to inform him of the reasons for his con

tinued detention violated due process. United States ex rel.

Mezei v. Shaughnessy, 101 F. Supp. 66, 68 (SDNY 1951).

The District Court ordered the Government to disclose those

reasons but gave it the option of doing so in camera. A fter

the Government refused to comply altogether, the District

Court directed Mezei’s conditional parole on bond. A di

vided panel of the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit af

firmed the parole order but, in a 5-4 decision, this Court

reversed.

The Court first distinguished between aliens who have en

tered the United States, whether legally or illegally, and

those who, like Mezei and petitioners here, are detained at

the border as they attempt to enter. The former group, the

Court reasoned, could be expelled “only after proceedings

conforming to traditional standards of fairness encompassed

in due process of law.” 345 U. S., at 212. The Court, how

ever, refused to afford such protections to the latter group.

Citing United States ex rel. Knauff v. Shaughnessy, supra,

the Court stated: ‘“Whatever the procedure authorized by

Congress is, it is due process as far as an alien denied entry is

concerned.’” 345 U. S., at 212 (quoting 338 U. S., at 544).

In Knauff, a 4-3 decision, an alien married to a United

States citizen had sought to enter the United States to be

naturalized. Upon arrival at our border, she was detained

14 JEAN v. NELSON

at Ellis Island. Eventually, and without a hearing, she was

permanently excluded from the United States on the basis of

undisclosed confidential information. The Court refused to

find a constitutional right to a hearing prior to exclusion,

stating that “it is not within the province of any court, unless

expressly authorized by law, to review the determination of

the political branch of the Government to exclude a given

alien.” United States ex rel. Knauff v. Shaughnessy, 338

U. S., at 543. Even though the procedural challenge in

Mezei was not related to an exclusion order, but instead to

the Government’s refusal to temporarily parole an alien who

already had been deemed excludable, the Court in Mezei did

not distinguish between the two situations. Instead, it fol

lowed Knauff as if it were directly on point.

Justices Black, Frankfurter, Douglas, and Jackson dis

sented in Mezei. Focusing on Mezei’s detention on Ellis

Island, Justice Jackson asked: “Because the respondent has

no right of entry, does it follow that he has no rights at all?”

345 U. S., at 226 (Jackson, J ., joined by Frankfurter, J ., dis

senting). He concluded that this detention could be enforced

only through procedures “which meet the test of due process

of law.” Id., at 227. Similarly, Justice Black stated that

“individual liberty is too highly prized in this country to allow

executive officials to imprison and hold people on the basis of

information kept secret from courts.” Id., at 218. (Black,

J ., joined by Douglas, J ., dissenting). He too thought that

“Mezei’s continued imprisonment without a hearing violate[d]

due process of law.” Id., at 217.

The statement in Knauff and Mezei that “[wjhatever the

procedure authorized by Congress is, it is due process as far

as an alien denied entry is concerned,” lies at the heart of the

Government’s argument in this case. This language sug

gests that aliens detained at the border can claim no rights

under the Constitution. Further support for that view

comes from Kwong Hai Chew v. Colding, supra, which was

decided after Knauff but one month before Mezei. The alien

JEAN v. NELSON 15

in Chew was a permanent resident of the United States who

was “excluded” upon his return to this country following a 5-

month trip abroad as a crewman on an American merchant

ship. The Court declined to follow Knauff, which, it stated,

“relates to the rights of an alien entrant and does not deal

with the question of a resident alien’s right to be heard.”

Kwong Hai Chew v. Colding, 344 U. S., at 596. The Court

then stated that a resident alien, unlike an alien entrant, “is a

person within the protection of the Fifth Amendment.”

Ibid. Focusing on Chew’s hybrid status—that of a resident

alien attempting to enter the United States—the Court said:

“While it may be that a resident alien’s ultimate right

to remain in the United States is subject to alteration by

statute or authorized regulation because of a voyage un

dertaken by him to foreign ports, it does not follow that

he is thereby deprived of his constitutional right to pro

cedural due process. His status as a person within the

meaning and protection of the Fifth Amendment cannot

be capriciously taken from him.” Id., at 601 (emphasis

added).

In the Court’s view, because he was a resident alien, Chew

was a “person” for the purposes of the Fifth Amendment.

Also under the Court’s view, however, the Executive’s char

acterization of Chew as a first-time entrant—rather than a

resident alien—was equivalent to taking away his status as a

“person” for the purposes of constitutional coverage.

The broad and ominous nature of the dicta in Knauff,

Chew, and Mezei becomes clear when one realizes that it ap

plies not only to aliens outside our borders, but also to aliens

who are physically within the territory of the United States

and over whom the Executive directly exercises its coercive

power. Moreover, it does not apply only to aliens in deten

tion at modern-day Ellis Islands; it applies also to individuals

who literally live within our midst, as our case law estab

lishes that aliens temporarily paroled into the United States

16 JEAN v. NELSON

have no more rights than those in detention. See Kaplan v.

Tod, 267 U. S. 228 (1925).

B

“It is a maxim, not to be disregarded, that general expres

sions, in every opinion, are to be taken in connection with the

case in which those expressions are used. If they go beyond

the case, they may be respected, but ought not to control the

judgment in a subsequent suit when the very point is pre

sented for decision.” Cohens v. Virginia, 6 Wheat. 264, 399

(1821) (Marshall, C. J.). The narrow question decided in

Knauff and Mezei was that the denial of a hearing in a case in

which the Government raised national security concerns did

not violate due process. See also infra, a t ----- . The ques

tion decided in Chew was that the alien’s due process rights

had been violated. The broad notion that “ ‘excludable’

aliens . . . are not within the protection of the Fifth Amend

ment,” Kwong Hai Chew v. Golding, 344 U. S., at 600, on

which the Government heavily relies in this case, Brief for

Respondents 28-29, is therefore clearly dictum, and as such

it is entitled to no more deference than logic and principle

would accord it. Under this standard, the broad dictum in

question deserves no deference at all.

Our case law makes clear that excludable aliens do, in fact,

enjoy Fifth Amendment protections. First, when an alien

detained at the border is criminally prosecuted in this coun

try, he must enjoy at trial all of the protections that the Con

stitution provides to criminal defendants. As early as Wong

Wing v. United States, 163 U. S. 228 (1896), the Court

stated, albeit in dictum, that while Congress can “forbid

aliens or classes of aliens from coming within [our] borders,”

it cannot punish such aliens without “a judicial trial to estab

lish the guilt of the accused.” Id., at 237. The right of an

unadmitted alien to Fifth Amendment due process protec

tions at trial is universally respected by the lower federal

courts and is acknowledged by the Government. See, e. g.,

JEAN v. NELSON 17

United States v. Henry, 604 F. 2d 908, 912-913 (CA5 1979);

United States v. Casimiro-Benitez, 533 F. 2d 1121 (CA9),

cert, denied, 429 U. S. 926 (1976); Respondents Brief in Op

position 20-21. Surely it would defy logic to say that a pre

condition for the applicability of the Constitution is an allega

tion that an alien committed a crime. There is no basis for

conferring constitutional rights only on those unadmitted

aliens who violate our society’s norms.

Second, in Russian Volunteer Fleet v. United States, 282

U. S. 481 (1931), the Court held that a corporation “duly or

ganized under, and by virtue of, the Laws of Russia,” id., at

487, could invoke the Fifth Amendment to challenge an un

lawful taking by the Federal Government. The corporation

in that case certainly had no more claim to being “within the

United States” than do the aliens detained at Ellis Island.

Nonetheless, the Court broadly stated that “[a]s alien

friends are embraced within the terms of the Fifth Amend

ment, it cannot be said that their property is subject to con

fiscation here because the property of our citizens may be

confiscated in the alien’s country.” Id., at 491-492 (empha

sis added). Under the dicta in the Knauff-Chew-Mezei tril

ogy, however, an alien could not invoke the Constitution to

challenge the conditions of his detention at Ellis Island or at a

similar facility in the United States. It simply is irrational

to maintain that the Constitution protects an alien from

deprivations of “property” but not from deprivations of “life”

or “liberty.” Such a distinction is rightfully foreign to the

Fifth Amendment.

Third, even in the immigration context, the principle that

unadmitted aliens have no constitutionally protected rights

defies rationality. Under this view, the Attorney General,

for example, could invoke legitimate immigration goals to

justify a decision to stop feeding all detained aliens. He

might argue that scarce immigration resources could be bet

te r spent by hiring additional agents to patrol our borders

than by providing food for detainees. Surely we would not

18 JEAN v. NELSON

condone mass starvation. As Justice Jackson stated in his

dissent in Mezei,

“Does the power to exclude mean that exclusion may be

continued or effectuated by any means which happen to

seem appropriate to the authorities? It would effectu

ate [an alien’s] exclusion to eject him bodily into the sea

or to set him adrift in a rowboat. Would not such meas

ures be condemned judicially as a deprivation of life

without due process of law?” Shaughnessy v. United

States ex rel. Mezei, 345 U. S., at 226-227.

Only the most perverse reading of the Constitution would

deny detained aliens the right to bring constitutional chal

lenges to the most basic conditions of their confinement.

Fourth, any limitations on the applicability of the Constitu

tion within our territorial jurisdiction fly in the face of this

Court’s long-held and recently reaffirmed commitment to

apply the Constitution’s due process and equal protection

guarantees to all individuals within the reach of our sover

eignty. “These provisions are universal in their application,

to all persons within the territorial jurisdiction, without re

gard to any differences of race, of color, or of nationality.”

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 369 (1886). Indeed, by

its express terms, the Fourteenth Amendment prescribes

that “[n]o State . . . shall deprive any person of life, liberty,

or property without due process ofiaw; nor deny to any per

son within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

In Plyler v. Doe, 457 U. S. 202 (1982), we made clear that

this principle applies to aliens, for “[wjhatever his status

under the immigration laws, an alien is surely a ‘person’ in

any ordinary sense of that term .” Id., at 210; see also

Mathews v. Diaz, 426 U. S. 67, 77 (1976). Such emphasis on

universal coverage is not surprising, given that the Four-

teentn Amendment was specifically intended to overrule a

legal fiction similar to that undergirding Knauff, Chew, and

Mezei—that freed slaves were not “people of the United

States.” Scott v. Sandford, 19 How. 393, 404 (1857).

JEAN v. NELSON 19

Therefore, it cannot rationally be argued that the Constitu

tion provides no protections to aliens in petitioners’ position.

Both our case law and pure logic compel the rejection of the

sweeping proposition articulated in the Knauff-Chew-Mezei

dicta. To the extent that this Court has relied on Mezei at

all, it has done so only in the narrow area of entry decisions.

See, e. g., Landon v. Plasencia, 459 U. S. 21, 32 (1982);

Kleindienst v. Mandel, 408 U. S. 753, 766 (1972). I t is in

this area that the Government’s interest in protecting our

sovereignty is at its strongest and that individual claims to

constitutional entitlement are the least compelling. But

even with respect to entry decisions, the Court has refused to

characterize the authority of the political branches as wholly

unbridled. Indeed, “[o]ur cases reflect acceptance of a lim

ited judicial responsibility under the Constitution even with

respect to the power of Congress to regulate the admission

and exclusion of aliens.” Fiallo v. Bell, 430 U. S. 787, 793,

n. 5 (1977).9

Regardless of the proper treatm ent of constitutional chal

lenges to entry decisions, unadmitted aliens clearly enjoy

“Even in the 1950’s, Mezei was heavily criticized by academic commen

tators. See, e. g ., Hart, The Power of Congress to Limit the Jurisdiction

of Federal Courts: An Exercise in Dialectic, 66 Harv. L. Rev. 1362, 1392-

1396 (1953) (describing the rationale behind Mezei as “a patently preposter

ous proposition”); 1 K. Davis, Administrative Law Treatise, §7.15, pp.

479-482 (1958); see also 2 K. Davis, Administrative Law Treatise, § 11:5,

p. 358 (2d ed. 1979) (“The holding that a human being may be incarcerated

for life without opportunity to be heard on charges he denies is widely con

sidered to be one of the most shocking decisions the Court has ever ren

dered”); Martin, Due Process and the Treatment of Aliens, 44 U. Pitt. L.

Rev. 165, 176 (1983) (describing Mezei as “a rather scandalous doctrine, de

serving to be distinguished, limited, or ignored”); Schuck, The Transforma

tion of Immigration Law, 84 Colum. L. Rev. 1, 20 (1984) (“[one] of the most

deplorable governmental conduct toward both aliens and American citizens

ever recorded in the annals of the Supreme Court”); Developments in the

Law—Immigration Policy and the Rights of Aliens, 96 Harv. L. Rev. 1286,

1322-1324 (1983); Note, Constitutional Limits on the Power to Exclude

Aliens, 82 Colum. L. Rev. 957 (1982).

20 JEAN v. NELSON

constitutional protections with respect to other exercises of

the Government’s coercive power within our territory. Of

course, this does not mean that the Constitution requires

that the rights of unadmitted aliens be coextensive with

those of citizens. But, “[ gjranting that the requirements of

due process must vary with the circumstances,” the Court is

obliged to determine whether decisions concerning the parole

of unadmitted aliens are consistent with due process, and it

cannot “pass back the buck to an assertedly all-powerful and

unimpeachable Congress.” Hart, The Power of Congress to

Limit the Jurisdiction of Federal Courts: An Exercise in Di

alectic, 66 Harv. L. Rev. 1362, 1394 (1953) (discussing

Knauff and Mezei). The proper constitutional inquiry must

concern the scope of the equal protection and due process

rights at stake, and not whether the Due Process Clause can

be invoked at all.

C

The Government argues, however, that the parole decision

at issue here is no different from an entry decision, and it

maintains that the holding of the Court of Appeals is com

pelled not only by the broad dicta in Mezei but also by Mezei's

actual holding. In support of this position, the Government

seizes on one phrase in Mezei—that to temporarily admit an

alien “nullifies the very purpose of the exclusion proceeding.”

Shaughnessy v. United States ex rel. Mezei, 345 U. S., at

216. It is simply untenable to weave a broad principle out of

the anomalous facts of Mezei.

The most obvious—and controlling—difference between

the two cases is that the alien in Mezei had already been ex

cluded on security grounds when he sought parole. Under

the circumstances, parole would have had the same perni

cious effects that the order of exclusion was designed to pro

tect against. Indeed, to the extent that Mezei’s presence in

this country was a threat to our national security, the threat

flowing from his temporary parole was as serious as that re

sulting from his admission. Activities such as espionage and

JEAN v. NELSON 21

sabotage can accomplish their objectives quickly; it does not

necessarily take years to steal sensitive materials or blow up

strategic buildings. Under the idiosyncratic facts of Mezei,

it was reasonable that the alien’s rights with respect to ad

mission and parole were deemed coextensive.

In contrast, the petitioners in this case have not been ex

cluded from the United States. In fact, the reason that they

are still in this country is that the Government has not yet

performed its statutory duty to evaluate their applications

for admission. More importantly, there is no argument here

that security questions are at stake, and there is no reason to

believe that petitioners’ parole would “nullify the purpose” of

their potential exclusion in some other way. As a m atter of

course, we admit tourists, students, and other short-term

visitors whom we would not want to have permanently in our

midst. Whatever immigration goals might be compromised

by actually admitting petitioners would not necessarily be

compromised similarly by paroling them pending the deter

mination of their admissibility. Here, unlike in Mezei,

parole and admission cannot be evaluated by the same

yardstick.

This case is different from Mezei in other important ways.

One such distinction is well captured in the Government’s

brief in Mezei:

“[I]f the court below is correct in determining that an

alien who can find no country to give him refuge is enti

tled at least to temporary admittance here, it follows

that the more undesirable an alien is, the better are his

chances of admission, since the less likely he is to find

other countries willing to accept him. In fact, if he is

undesirable enough, he may attain what amounts to per

manent residence in this country since no other nation

will ever take him in.” Brief for Petitioner in No. 52-

139, 0. T. 1952, p. 19.

Through parole, Mezei could have gained the same important

substantive immigration rights that he already had been de

22 JEAN v. NELSON

nied when he was excluded. In contrast, petitioners here

could gain no such rights. Their parole could be terminated

at any time at the discretion of the Attorney General and

their admissibility would then be determined at exclusion

proceedings just as if they had never been paroled. See 8

U. S. C. § 1182(d)(5)(A); Leng May Ma v. Barber, 357 U. S.,

at 188; Kaplan v. Tod, 267 U. S., at 230; 1 C. Gordon & H.

Rosenfield, 1 Immigration Law and Procedure, §2.54, at

2-374. Whereas parole will never give petitioners a “foot

hold in the United States,” Kaplan v. Tod, at 230, it might

have made it possible for Mezei to stay here indefinitely.

Moreover, Mezei’s incentives to look for a country willing

to take him would have disappeared had he been released

from Ellis Island and allowed to return to his wife and home

in Buffalo, N. Y. See Shaughnessy v. United States ex rel.

Mezei, 345 U. S., at 217 (Black, J ., dissenting). In this case,

the same incentives are simply not present.

Turning from substance to procedure, I find that the

Court’s refusal to accord Mezei the procedural due process

rights that he sought—namely, to know what information the

Government had relied upon—had less to do with Mezei’s sta

tus as an alien than with the Court’s willingness to defer to

the Executive on national security m atters in the midst of the

Cold War. Indeed, in Jay v. Boyd, 351 U. S. 345 (1956), the

Court upheld the Govenment’s use of similar confidential in

formation in a deportation proceeding. Even though the

Court recognized that “a resident alien in a deportation pro

ceeding has constitutional protections unavailable to a non

resident alien seeking entry into the United States,” id., at

359, it nonetheless relied on Knauff and Mezei to dismiss the

alien’s claim, id., at 358-359. In doing so, it noted that the

constitutionality of the Government’s practice gave it “no dif

ficulty.” Id., at 357, n. 21. In Jay, the Court viewed

Knauff and Mezei as national security cases and not as cases

involving aliens attempting to enter the United States. In

JEAN v. NELSON 23

this case, in contrast, no national security considerations are

said to be at stake.

Finally, whatever Mezei may have held about procedural

due process rights in connection with parole requests is not

applicable to the separate constitutional question whether

the Government may establish a policy of making parole deci

sions on the basis of race or national origin without articulat

ing any justification for its discriminatory conduct. As far

back as Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886), the Court

recognized that even decisions over which the Executive has

broad discretion, and which the Executive may make without

providing notice or a hearing, cannot be made in an invidi

ously discriminatory manner. Under the statute that the