State of South Carolina v. Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. State of South Carolina v. Brief Amici Curiae, 1988. fc1a3111-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e7a8574c-a6e0-4c4b-8373-be41382fd3f6/state-of-south-carolina-v-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

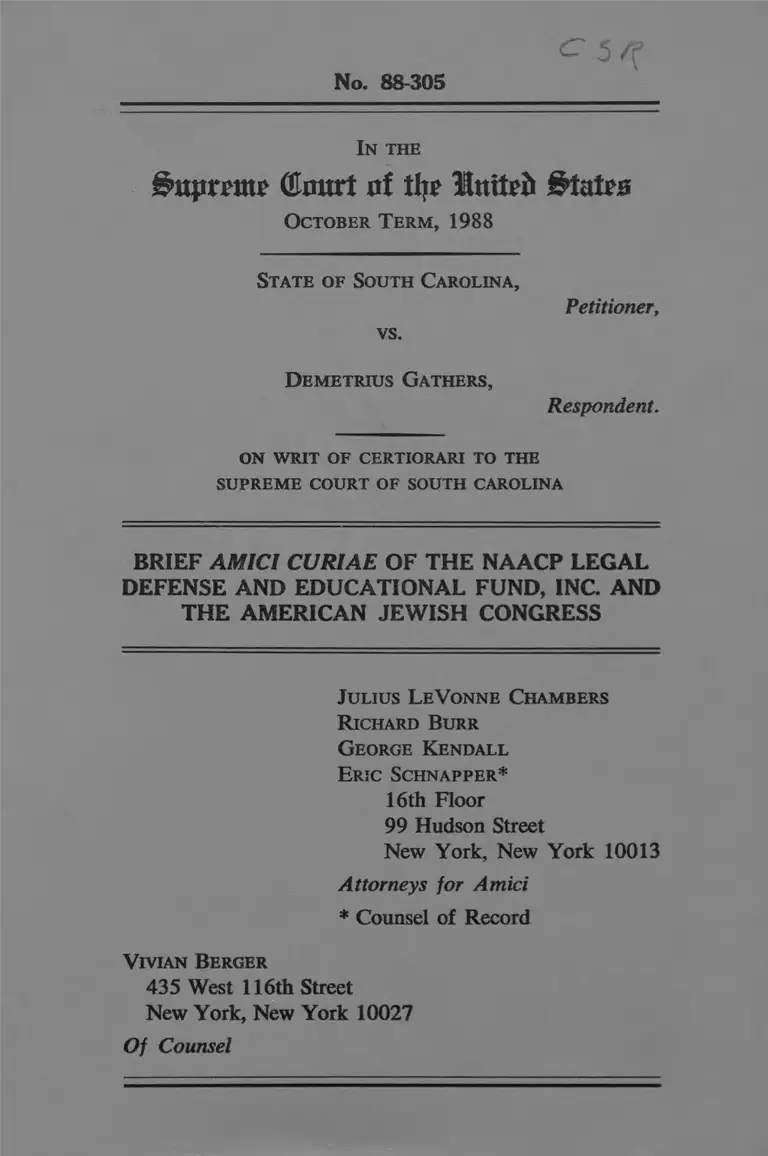

No. 88-305

^ 5 / f '

In the

(Umtrt of tit? #tat?n

O ctober Te r m, 1988

State of South Carolina,

vs.

Petitioner,

D emetrius G athers,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AND

THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS

Julius LeV onne Chambers

Richard Burr

G eorge K endall

Eric Schnapper* *

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

Attorneys for Amici

* Counsel of Record

V ivian Berger

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Of Counsel

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

(1) May the sentence imposed on a

criminal defendant be based

upon an evaluation by a judge

or jury of the moral or

societal worth of the crime

victim?

(2) Did the prosecutor's closing

argument in this case encourage

the jury to base its decision

in favor of capital punishment

on such constitutionally

impermissible considerations?

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

i

Page

Questions Presented

Table of Authorities

Interest of Amici ................. 1

Summary of Argument ............... 2

Argument .......................... 6

I. The Sentence Imposed on

a Criminal Defendant May

Not Be Based on a Juror's

or Judge's Personal

Opinion About the Moral

or Societal Worth of the

Crime Victim............... 6

A. The Imposition of

Differing Sentences

Based on the Perceived

Moral or Societal Worth

of Crime Victims Violates

the Equal Protection

Clause .................. 10

B. The Eighth Amendment

Precludes Basing the

Magnitude of a Sentence

on the Perceived Moral

or Societal Worth of the Victim .................. 3 0

ii

Page

C. The Constitutional Issue

Presented by this Case

Should Be Definitively

Resolved ................ 46

II. The Prosecutor's Closing

Argument Encouraged the

Jury to Base the Sentenc

ing Decision on its

Perception of the Moral

or Societal Worth of the

Crime Victim........... 51

Conclusion ....................... 63

Appendix A: Capital Statutes Con

cerning Public or ■

Quasi-Public Officials. la

Appendix B: Capital Statutes Con

cerning Interference

With Government

Functions ............ 16a

Appendix C: Hearings of the Joint

Committee on Recon

struction ............ 22a

(1) References to

"Protection" ..... 22a

(2) References to

Abuses of Union

Loyalists,

Northerners, and

Other Whites ..... 43a

iii

Page

(3) References to Un

willingness of

States to Protect

Lives, Liberty or

Property ....... 51a

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Batson v. Kentucky,

476 U.S. 79 (1986) ........... 49

Booth v. Maryland, 96 L.Ed.2d 440

(1987) ....................... passim

Brooks v. Kemp, 762 F.2d 1383

(5th Cir. 1985) 52

Caldwell v. Mississippi,

472 U.S. 312 (1980) 57

California v. Ramos,

463 U.S. 992 (1983) 4,30,31,

33,45,46

Donnelly v. DeChristoforo,

416 U.S. 637 (1974) 55

Francis v. Franklin,

471 U.S. 307 (1985) 5,57

Franklin v. Lynaugh,

101 L. Ed. 2d 155 (1988) 52

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238

(1972) 4,35

Godfrey v. Georgia,

446 U.S. 420 (1980) 31,39

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153

(1976) 33,35

McCleskey v. Kemp,

95 L.Ed.2d 262 (1987) 11,31,33,

38,56

V

Page

Mills v. Maryland,

100 L. Ed. 2d 384 (1988) ........ 9

Moore v Kemp, 809 F.2d 702

(11th Cir. 1987) 38,52

Moore v. Zant, 722 F.2d 640,

(11th Cir. 1984) 38

State v. Gathers, 369 S.E.2d

140 (S.C. 1988) 5,47

Swain v. Alabama,

380 U.S. 202 (1969) 49

Thompson v. Oklahoma,

101 L.Ed. 2d 702 (1988) 40

Vela v. Estelle, 708 F.2d 954

(5th Cir. 1983) 38

Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862

(1983) 30,31,

33,35

Statutes:

Del. Code Ann, tit. 11

§ 4209 (e) (q) (1982 Supp.) ...... 27

S.C. Code Ann.

§ 16-3-20(c)(a)(5)-(7)

(1986) 42

S.C. Code Ann.

§ 16-3-20(0) (a) (7) (1986) ..... 43

Wash. Rev. Code Ann.

§ 10.95.020(10) (1981) 45

Other Authorities:

vi

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong.,

1st sess. (1866) .... 4,11-28

W. Blackstone, Commentaries on the

Laws of England (17 65) ........ 63

W. Hawkins, A Treatise of the

Pleas of the Crown (1716) 63

W. Rose, A Documentary History

of Slavery in North America

(1976) 15

J. ten Broek, Egual Under Law

(1951) 13,14

T. Wood, An Institute of the

Laws of England (3rd ed. 1724).. 63

New York Times, Dec. 17, 1988 ...... 10

vii

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. and the

AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS

INTEREST OF AMICI

The NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., is a non-profit

corporation established to assist black

citizens in securing their constitutional

rights. In 19 67 the Fund undertook to

represent indigent death-sentenced

p r i s o n e r s for w h o m a d e q u a t e

representation could not otherwise be

found. The Legal Defense Fund currently

represents several indigent condemned

prisoners whose cases might be affected

by the decision in the instant case.1

The American Jewish Congress is an

organization of 50,000 members formed in

1 Copies of letters from the

parties consenting to the filing of this

brief have been filed with the Clerk.

2

1918 to protect the economic, civil,

religious and political rights of

American Jews. It has a continuing

concern that the constitutional

safeguards of equal protection of the

law, due process and freedom from cruel

and unusual punishment are assured all

Americans. Although it is an

organization which grounds Its public

policy views in a religious and ethical

tradition, it believes that in order to

give effect to these constitutional

guarantees, a sentence may not be imposed

on a criminal defendant based on the

evaluation by a judge or jury of the

moral or societal worth or religiosity of

the crime victim.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case, unlike Booth v. Maryland.

L.Ed.2d 440 (1987), does not concern

whether a sentencing decision may be

3

based in part on the harm suffered by the

family of a murder victim. The question

raised by prosecutor's closing argument

in this case, and by the decision below,

concerns whether a sentencing decision

may turn on a jury's opinions about the

moral worth or value to society of a

victim.

For a judge or jury to impose a

greater or lesser penalty in a criminal

case, according to their opinions about

the moral or societal worth of the

victim, would violate one of the core

meanings of the equal protection clause.

That clause embodies two distinct

principles, the familiar anti-

discrimination doctrine, and an

affirmative obligation on the part of a

state to protect with equal vigilance the

life, liberty and property of every

person within its jurisdiction. While

4

the anti-discrimination doctrine forbids

only certain distinctions, the protection

principle prohibits any distinctions in

the protection afforded by certain

criminal and non-criminal laws. As

Senator Poland insisted, "All the people,

or all the members of a state or

community, are equally entitled to

protection."2

Although the eighth amendment

permits a jury to consider a myriad of

circumstances in making a sentencing

determination, a jury may not utilize

standards likely to reintroduce the

arbitrariness condemned in Furman v.

Georgia. 408 U.S. 238 (1972), or rely on

c o n s t i t u t i o n a l l y i m p e r m i s s i b l e

considerations. California v. Ramos, 463

U.S. 992, 1000 (1983). Permitting jurors

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., sess. 2962 (1866). 1st

5

to base sentencing decisions on their

opinions about the moral or societal

worth of a victim would inevitably lead

to such arbitrariness and improper

considerations. Neither South Carolina

nor any other state authorizes a

sentencing jury to rely on such personal

opinions. Many states do single out

specific government positions for special

protection, but the choice of those

positions is always made by the

legislature itself, and never left to the

whims of particular juries.

The South Carolina Supreme Court,

after reviewing the text of the

prosecutor's argument at the sentencing

hearing, properly concluded that the

"remarks conveyed the suggestion

appellant deserved a death sentence

because the victim was a religious man

and a registered voter." State v.

6

Gathers. 369 S.E. 2d 140, 144 (S.C.

1988). The dispositive issue is not

whether the prosecutor personally

intended to violate the eighth or

fourteenth amendment, but how a

reasonable juror would have understood

the prosecutor's statements. Francis v.

Franklin. 471 U.S. 307, 315-16 (1985).

ARGUMENT

I. THE SENTENCE IMPOSED ON A CRIMINAL

DEFENDANT MAY NOT BE BASED ON A

JUROR'S OR JUDGE'S PERSONAL OPINION

ABOUT MORAL OR SOCIETAL WORTH OF THE

CRIME VICTIM

Two years ago, in a sharply divided

opinion, this Court held that the

sentence in a capital case could not be

based on evidence regarding the harm

which the crime might have caused to the

family of a murder victim. Booth v.

Maryland, 96 L.Ed.2d 440 (1987). This

controversial aspect of Booth is not

involved in the instant case. At the

7

penalty phase of the proceeding below,

the prosecution neither adduced evidence

that there had been injury to the family

of the victim, Richard Haynes, nor

suggested to the jury that a sentence of

death was warranted by any such harm. If

this Court wishes to reconsider the

holding in Booth that a capital sentence

may not be based on such harms to family

members, it must do so in another case

which actually presents that issue.

The instant case turns on a second,

considerably less controversial aspect of

the decision in Booth. The majority

there also held that a capital sentence

could not be based on "the character and

reputation of the victim". 96 L.Ed.2d at

440. The court reasoned that there could

be no

justification for permitting such a

decision to turn on the perception

that the victim was a sterling

member of the community rather than

8

someone of questionable character. .

. . We are troubled by the

implication that defendants whose

victims were assets to their

community were more deserving of

punishment than those whose victims

are perceived to be less worthy. Of

course, our system of justice does

not tolerate such distinctions.

96 L.Ed.2d at 450 and n.8. Booth

addressed this issue because the Victim

Impact Statement in that case contained a

substantial and highly -laudatory

description of the victims. 96 L.Ed.2d

at 453, 456.

But the Booth's rejection of such

character evidence, unlike its

disapproval of evidence regarding family

members, involved no rejection of any

judgment by the state legislature; the

Maryland statute, in a murder case, did

not authorize the inclusion in the VIS of

any personal information about the victim

except his or her identity. 96 L.Ed.2d

at 446. In his brief in this Court, the

9

Maryland Attorney General defended the

capital sentence in Booth solely on the

basis of the evidence of injury to family

members, and carefully avoided any

suggestion that state law authorized, or

that the federal constitution would

permit, the imposition of a death

sentence based on the perceived moral or

societal worth of the victim. On the

c o n t r a r y , the state in Booth

affirmatively insisted that it would

indeed be improper to base a capital

sentence on the "social status" or

"religion" of a victim, and went so far

as to urge that any juror inclined to do

so ought be removed from the venire.3 The

J Brief for Respondent, No. 8 6-

5020, p. 36-37. Similarly, in Mills v.

Maryland. 100 L.Ed.2d 384 (1988), the

state stressed "There was no evidence

suggesting that the community at large

suffered.... There was no evidence

indicating that [the victim] led a life

to be valued by others." Brief of

Respondent, No. 87-5367, p. 33.

10

death sentence in this case was grounded

on precisely the type of criterion which

the state in Booth expressed acknowledged

would indeed be improper.

A. The Imposition of Differing

Sentences Based on the

Perceived Moral or Societal

Worth of Crime Victims Violates

the Equal Protection Clause

A month ago Judge Jack Hampton of the

Texas District Court openly proclaimed

that it was his policy to impose lesser

sentences in murder cases if the victim

was either a prostitute or a homosexual.

The Executive Director of the Texas

Commission on Judicial Conduct, asked to

comment on that sentencing standard,

remarked, "I can't right off think of any

part of the code that might violate."4

Judge Hampton's sentencing practice, like

4 New York Times, Dec. 17, 1988.

11

the closing argument in the instant case,5

violates one of the core meanings of the

equal protection clause.

The debates of the Congress which

approved the fourteenth amendment make

clear that the framers understood the

equal protection clause to embody two

quite distinct but equally important

principles. First, of course', the equal

protection clause was recognized to

prohibit invidious discrimination, an

abuse then referred to as the making of

distinctions on the basis of "class" or

"caste."6 The second agreed upon meaning

This Court held in McCleskev v.

Kemp, 95 L.Ed.2d 262, 278 n. 8 (1987),

that a sentencing decision based on

unconstitutional distinctions among crime

victims violates the rights of the person

so sentenced to equal protection and to

freedom from arbitrary government action.

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st

sess. 537 (Rep. Stevens) (race), 674 (Sen.

Sumner) (race), 704 (Rep. Fessenden)

(caste), 707 (Rep. Fessenden) (caste),

1095 (Rep. Hotchkiss) (class) , 1227 (Sen.

12

was that a state had an affirmative

obligation to protect from attack or

invasion by third parties the lives,

liberty, and property of all persons

within its jurisdiction. Equal protection

in this second sense concerned the

protection accorded by the criminal law

(e.g. prohibitions against murder,

kidnapping and theft) and by certain non

c r i m i n a l laws (e.g., tort and

conversion).7 It required a state to

extend to the life, freedom and property

of every person the same full measure of

legal protection that was afforded to the

lives, freedom and property of others.

Sumner) (caste or color), 2766 (Sen.

Howard) (class), 3035 (Sen. Henderson)

(race), app. 104 (Rep. Yates) (class)

(1866).

In the hearings of the Joint

Committee on Reconstruction, which drafted

the fourteenth amendment, most uses of

the word "protection" are references to

government protection against crimes by

third parties. See Appendix C(l).

13

The anti-discrimination principle applies

to all forms of state action, but forbids

only certain invidious distinctions; the

protection principle applies only to state

actions related to the protection of life,

liberty and property, but forbids a state

to deny full and equal protection on any

basis whatever.

The phrase "equal protection of the

laws" was originally coined by

abolitionists early in the nineteenth

century to refer to the protection

principle; the history of the phrase and

concept are detailed by Professor ten

Broek in Equal Under Law (1951). Slavery

was said to deny "equal protection"

because it permitted some individuals, the

slaveowners, to steal the property,

violate the liberty and take the lives of

others, the slaves. This argument was

reiterated time and again by abolitionists

14

in the decades before the Civil War. In

an 1837 address to the Massachusetts

legislature, for example, Henry B. Stanton

complained that a slave was denied

all the protection of the law as

a man. His labor is coerced

from him.... No bargain is

made, no wage is given....

There is not the shadow of legal

protection for the family state

among slaves ... neither is

there any real protection for

the limbs and lives of

slaves.... [T]he slave should

be protected in life and limb,

in his earnings, his family, and

social relations.... To give

impartial real protection ... to

all ... inhabitants would

annihilate slavery. Give the

slave then, equal protection

with his master, and at its

first approach slavery and the

slavery trade flee in panic, as

does darkness before the full-

orbed sun.8

Although under the slave codes some

attacks on slaves and their property were

forbidden, the law fixed lesser penalties

for a crime against a slave or free black

Quoted in J. Ten Broek, Equal

Under Law. 46-67 (1951).

15

than for the same offense against a

white.9

This doctrinal derivation of the

equal protection clause is reflected in

the first draft of section one debated by

the House of Representatives in 1866; that

proposal would have given Congress

authority to secure "to all persons in the

several States equal protection in their

rights of life, liberty and property."10

Representative Wilson referred to the more

elaborate theory familiar to congressmen

on both sides of the aisle when he

asserted

"the right of being protected in

life, liberty, and estate is due

to all, and cannot be justly

denied to any...." [T]he State

that does not give protections

to the life, liberty, and

See W. Rose, A Documentary

History of Slavery in North America. 193-

94 (1976) (text of Alabama Slave Code).

10 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1stsess. 1034.

16

property of all men violates its

duty, because every person has

this due him for his allegiance

to the Government. . . .11

Even some who opposed the fourteenth

amendment agreed that every state had a

duty to give full and equal protection to

the lives, liberty and property of all;

they objected only that any needed

corrective measures should come from the

states themselves.12

The debates on the fourteenth

amendment, to be sure, reveal as well a

universal understanding that it would

prohibit invidious discrimination. But it

is entirely clear from those debates that

the phrase "equal protection of the laws"

was understood to encompass at least two

distinct doctrines, entitlement to full

and equal protection of life, liberty and

11 Id. at 1225.

12 Id. at 1064 (Rep. Hale) , App.138 (Rep. Rogers).

17

property, and a prohibition against

invidious discrimination. Representative

Eliot, for example, described section one

as including several distinct components,

p r o h i b i t i n g " S t a t e l e g i s l a t i o n

discriminating against classes of citizens

or depriving any persons of life, liberty,

or property without due process of law, or

denying to any persons within the State

the equal protection of the laws."13

Representative Rogers, who evidently

agreed with the protection principle,

nonetheless refused to accept the non

discrimination principle, arguing in favor

of governmental racial discrimination in

other areas, such as marriage and school

segregation.14

Insofar as the protection by a state

13 Id. at 2511.

14 Compare id. at app. 13 4 with id. at app. 138.

18

of life, liberty and property is

concerned, the equal protection clause is

not a provision which tolerate some but

not other distinctions, but a prohibition

against any distinctions whatsoever.

Senator Wilson emphasized that the state's

obligation to provide protection extended

to all men, women and children in the

jurisdiction; "Every human being in the

country, black or white, man or woman, or

little child in the cradle, has a right to

be protected in life, in property, and in

liberty."15 16 Senator Poland insisted "All

the people, or all the members of a State

or community, are equally entitled to

protection."15 Senator Stewart recognized

"the obligation of full protection for all

men."17 The requirement that blacks

15 Id. at 1255.

16 Id. at 2952.

17 Id. at 2964.

19

receive equal protection was merely an

incidental application of the general rule

that all persons were to be so treated:

[W]e do say that all men areequally entitled • • • to theprotection of the law, and thatthe weak need the protection of

the law more than the strong;

and we do say now that the negro

in the south is manumitted . . .

he must be protected....18

Representative Pomeroy stressed that the

degree of protection afforded to life,

liberty and property could not vary in any

way from person to person: "[E]very

person should have the safeguards of law

weighed out in equal and exact

balances."19 Representative Bingham

Id. at 3528 (Sen. Stewart).

id. at 1182; see also id. at

2459 (Rep. Stevens) (Congress must assure

"that the law which operates upon one man

shall operate equally upon all....

Whatever means of redress is afforded to

one shall be afforded to all.") (emphasis

in original), 2539 (Rep. Farnsworth) ("Is

it not the undeniable right of every

subject of the government to receive

'equal protection of the laws' with every

20

called on Congress to guarantee "equal,

exact justice" by assuring "that the

protection given by the laws of the State

shall be equal in respect to life and

liberty and property to all persons."20

When Representative Hale stated that

he understood "the whole intended

practical effect" of the first draft of

section 1 to be "the protection of

'American citizens of African descent'",

Representative Bingham immediately rose to

disagree, explaining that the Joint

Committee on Reconstruction — which

reported both that and the final version

the fourteenth amendment — was equally

concerned to afford protection to the

hundreds of thousands of loyal white

citizens" facing abuse in the south.21

other subject?")

20 Id. at 1094.

21 Id. at 1065.

21

The hearings of the Joint Committee, which

were reprinted for and referred to by

other members of Congress, contained

extensive testimony regarding attacks on

union loyalists in the former rebel

states,22 and concerning the unwillingness

of local officials to protect their lives,

liberty and property.23 The report of the

Joint Committee which accompanied the

final draft of the fourteenth amendment

emphasized the need to deal with this

problem.24 The congressional debates on

the fourteenth amendment contained

frequent references to the mistreatment of

^ See Appendix C(2).

23 See Appendix C(3).

24 Report of the Joint Committee on

Reconstruction, 39th Cong., 1st sess. xvi

(southern loyalists "denounce[d] and

revile[d])," xvii ("without the protection

of United States troops, Union men,

whether of northern or southern origin,

would be obliged to abandon their homes"),

xviii (southern loyalists "bitterly hated

and relentlessly persecuted").

22

and southern hostility towards union

supporters.25 Proponents of the equal

protection clause stressed that it would

protect unionists who had remained in the

south, union sympathizers who had fled

north, former Union soldiers, and

northerners visiting the south.26 No one,

however, described hostility to these

groups as being based on "class" or

"caste" — the terms of that era for

invidious discrimination. Union

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st

sess. 739 (Sen. Lane), 834 (Sen. Clark),

1091-94 (Rep. Bingham), 1182 (Sen.

Pomeroy), 1184 (Sen. Henderson), 1228

(Sen. Sumner) , 2535 (Rep. Eckley) , 2537

(Rep. Beaman), 2542 (Rep. Bingham), 2800 (Sen. Stewart) .

26 Id. at 1066 (Sen. Clark)

(northerners), 1084-85 (Sen. Davis)

(loyalists), 1094 (Rep. Bingham) (union

soldiers), 2536 (Rep. Eckley) (union

refugees), 2537 (Rep. Beaman) (loyalists),

2540 (Rep. Farnsworth) (loyalists), 2798

(Sen. Stewart) (loyalists); also id. at

1090 (Rep. Bingham) (aliens), 1757 (Sen.

Trumbull) (aliens), 2890 (Sen. Howard)

(aliens), 2891 (Sen. Cowan) (aliens).

23

supporters and northerners were to receive

equal protection against attacks on their

lives, liberty and property, not because

of the motives behind those attacks or the

official indifference to them, but because

everyone was entitled to that protection,

regardless of why he or she might need it.

The most detailed and impassioned

explanations of the concept of equal

protection denounced differences based on

the wealth and status of the victim.

Representative Bingham, one of the framers

of section one, argued:

[A]11 men are equal in the

rights of life and liberty

before the majesty of American

law. Representatives, to you I

appeal, that hereafter, by your

act and the approval of the

loyal people of this country,

every man in every state of the

Union, in accordance with the

w r i t t e n w o r d s of your

Constitution, may, by the

national law, be secured in the

equal protection of his personal

rights ... no matter what his

color, no matter beneath what

sky he may have been born, no

matter in what disastrous

conflict or by what tyrannical

hand his liberty may have been

cloven down, no matter how poor,

no matter how friendless, no

matter how ignorant.27

Senator Wilson deplored the social and

legal system of the south as a vestige of

the worst of old world "aristocracies or

oligarchies," which raised or lowered

criminal punishments according to whether

the victim was a "noble" or a "plebian."28

Representative Donnelly asked

Are [the] sacred pledges of

life, liberty and property to

fall to the ground? Shall the

old reign of terror revive in

the South, when no northern

man's life was worth an hour's

purchase. Or shall that great

Constitution be what its

founders meant it to be, a

shield and a protection over the

head of the lowliest and poorest

27 Id. at 1094.

25

citizen in the remotest region of the

nation?29

Senator Howard, observed that the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment,

establishes equality before the

law, and it gives to the

humblest, the poorest, the most

despised of the race the same

rights and the same protection

before the law as it gives the

most powerful, the most wealthy,

the most haughty.30

In demanding protection for freedmen

facing oppression in the former

confederate states, Senator Wilson relied

not on the anti-discrimination principle,

but on the protection doctrine embodied in

the equal protection clause:

[T]he poorest man, be he black

or white, that treads the soil

of this continent, is as much

entitled to the protection of

the law as the richest and

Id. at 586.

Id. at 2 766; see also id. at app. 256 (Rep. Baker).

26

proudest man in the land....

[T]he poor man, whose wife may

be dressed in a cheap calico, is

as much entitled to have her

protected by equal law as is the

rich man to have his jeweled

bride protected by the laws of

the land.... [T]he poor man's

cabin, though it may be the

cabin of a poor freedman in the

depths of the Carolinas, is

entitled to the protection of

the same law that protects the

palace of a Stewart or an

Astor.. . .31

That is the meaning of the words engraved

over the portico of the building in which

this Court sits.

This concept of equal protection is

utterly incompatible with any notion that

a statute, judge or jury might value the

lives of some persons more highly than the

lives of others.32 Representative Baker

Id. at 343.

This aspect of equal protection

does not, of course, preclude special

treatment of murders which not only take a

life but which also, in the judgment of a

legislature, seriously interfere with the

functioning of government, see Appendices

A and B, or are perpetuated against

27

insisted that " [t]rue democracy, like true

religion, recognizes the inherent and

immeasurable value of man, and of all

men."33 Senator Clark acknowledged that

society might be more affected by the

death of one person than by that of

another, but insisted that the law could

not on that account treat the killing of

one person as less blameworthy than the

killing of another:

Was not your Government

founded upon that idea — the

idea of political equality of

all men? Is [a black man] not

entitled to his life as clearly

and fully as the white man?

That life may not be of the same

consequence in the community as

another life, but be it of more

or less value, is not the negro

just as such entitled to it as

any other man can be to his?

particularly vulnerable victims. See Del.

Code Ann. tit. 11, § 4209 (e) (q) (1982

supp.) (aggravating circumstance if "[t]he

victim was severely handicapped or severely disabled.")

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong. 1st

sess. app. 257 (emphasis in original).

28

And has he not a right just as

qood to have it protected by law?34

A sentencing procedure which

effectively required, or even allowed, a

defendant to argue or seek to prove that

his victim was of inferior moral or

societal worth, entitled to only half

hearted protection by the legal system,

would be more than a dangerous diversion

from legitimate considerations, Booth v.

Maryland, 96 L.Ed.2d at 451; to put the

very victim of a crime on trial in this

manner would offend one of the central

guarantees of the fourteenth amendment.

As individuals we mourn with special

sorrow the death of men and women whose

particular gifts and promise we may have

valued most highly. But the Constitution

knows no such distinctions. The

Fourteenth Amendment attaches to the

34 Id. at 833 (emphasis added).

29

lives of those born in the opulence of

Park Avenue, Palm Beach and Beverly Hills

precisely the same immeasurable value that

it recognizes in the lives of those who

sleep on the heating vents on the Mall,

who carry all their worldly possessions in

a shopping cart, or who speak in

unintelligible cadences to voices that

none other hear. In other lands and under

other legal systems, the measure of

redress and punishment may yet be

calibrated to the status and stature of

the interested parties, but in the United

States of America victim and perpetrator

alike are neither rich nor poor, black nor

white, revered nor reviled, believer nor

heretic, but only persons whose greatest

birthright is their equality.

30

B. The Eighth Amendment Precludes Basina

the Magnitude of a Sentence on the

Perceived Moral or Societal Worth of

the Victim

Six years ago this Court held in

California v. Ramos. 463 U.S. 992 (1983),

that the range of factors which might be

considered by a sentencing jury, although

extremely broad, was nonetheless subject

to several specific constitutional

constraints. Ramos recognized that

individualized sentencing decisions would

require a jury "to consider a myriad of

factors to determine whether death is the

appropriate punishment," 463 U.S. at 1008,

and Zant v. Stephens. 462 U.S. 862 (1983),

made clear that a state was not required

to spell out in a statute every

aggravating consideration which a jury

might take into account. 462 U.S. at 875.

On the other hand, Ramos squarely held

that the eighth amendment did impose

31

"substantive limitations on the particular

factors that a capital sentencing jury may

consider." 463 U.S. at 1000. One such

constitutional constraint, Ramos noted,

was that a jury could not utilize a

standard which "might lead to the

arbitrary and capricious sentencing

patterns condemned in Furman [v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1972)]." Id:; see also

Godfrey v. Georgia. 446 U.S. 420, 428

(1980). Zant held that a state could not

"attac[h] the 'aggravating' label to

factors that are constitutionally

impermissible or totally irrelevant to the

sentencing process, such as for example

r a c e , r e l i g i o n , or p o l i t i c a l

affiliation---" 462 U.S. at 885. See

also McCleskev v. Kemp. 95 L.Ed.2d 262,

278 n. 8 (1987); Gregg v. Georgia. 428

U.S. 153, 198 (1976).

32

Petitioner appears to contend that

the constitution permits a capital

sentencing decision to be based on the

personal opinions of individual jurors

regarding the value to society or the

moral worth of a murder victim. That

guestion arises in the instant case

because the prosecution's closing argument

appealed to the jury to base its sentence

on just such opinions. See part II,

infra. The constitutional issue here is

the same as that which would arise if the

judge had expressly instructed each juror

to make a personal evaluation of the

character and societal worth of the

victim, and to consider that opinion in

deciding on the appropriate sentence. We

urge that the use of such personal

opinions to decide whether a capital

defendant will live or die is inconsistent

33

with Ramos, Zant and Gregg. See McCleskev

v . Kemp. 95 L.Ed.2d 262, 278 n. 8 (1987).

If a deliberate attempt were to be

undertaken to reintroduce into the capital

sentencing process all the arbitrariness

and potential for bias that flawed the

pre-Furman capital punishment schemes, it

would be difficult to concoct a more

effective scheme for doing so than

petitioner's proposal that jurors base

sentencing decisions on their personal

opinions about the character or value to

society of a murder victim. This is not a

case in which a legislature has determined

that a specific governmental function,

such as that of a police officer, is of

unusual importance to society, and a jury

has been authorized to make a factual

determination as to whether the victim was

in fact a police officer killed in the

course of his or her duties. Rather, what

34

petitioner proposes is that each

particular jury or other sentencing

authority, choose for itself, from among

the universe of personal characteristics

and societal roles, those which it thinks

are deserving of special protection.

Petitioner asks, not that the jury in this

case be permitted to implement a decision

of the South Carolina legislature to

extend such heightened protection to

certain positions, but that each and every

jury in South Carolina be permitted to

make such legislative decisions for

itself.

The statutes sustained in Gregg and

its progeny were upheld because the

objective standards they contained

substantially reduced the danger that

jurors would ground sentencing decisions

on their personal social, political, or

economic views, opinions often irrelevant

35

to the sentencing process and in many

instances constitutionally impermissible.

But a rule that based a sentencing

decision on the "personal characteristics"

or "value to society" of the victim would

not simply permit, but quite literally

require jurors to use such social,

political, economic beliefs to decide

which defendants would live and die.

There is probably no question about which

Americans are more likely to disagree than

the identity of the individuals, other

than certain critical government

officials, who are of greatest value to

our society, and whose deaths would be a

particularly serious loss. The personal

opinions which Furman. Gregg and Zant

insist ought be irrelevant to the

sentencing process would have to be relied

on by a juror asked to assess the value to

society, for example, of a union shop

36

steward, a venture capitalist, a newspaper

columnist, a television evangelist, a

professional lobbyist, a tobacco company

lawyer, or a gun store owner.

A sentencing process based on such

jury determinations would readily, perhaps

inexorably, be tainted by considerations

that w o u l d be c o n s t i t u t i o n a l l y

impermissible. That problem would

inevitably extend to and taint the jury

selection process; a prosecutor would

naturally select a venue and exercise his

peremptory challenges in order to craft a

jury whose political, economic and social

views would lead them to place particular

value on the contributions of the victim.

Regardless of the prosecutor's actions, a

capital punishment statute would often

have a different meaning in various parts

of a single state depending on local mores

and interests; thus within New York the

37

societal function deemed by local juries

to be of particular value might be apple

farmers in Cortland, oysterman on Long

Island, the ski patrol in the Catskills,

and Transit Authority workers in

Manhattan. At best such a sentencing

scheme would be a lottery, in which the

life or death of a capital defendant would

turn on the particular mix- of social,

economic and political views that chanced

to prevail among the randomly selected

jurors passing on his fate.

A sentencing decision based on the

"personal characteristics" — as distinct

from value to society, to the extent that

such a distinction could be made — would

be even more arbitrary. The personal

characteristics on which a jury or judge

might choose to rely are virtually

38

limitless.35 In the instajst csss® life®

prosecutor focused on the vijusî nm ”̂ s m

religious person and the possessor raff

voter registration card". (ffitef:.., 'M. 3sr̂

49) . The Victim Impact Statement &h Stexdt3b

stressed that the victims iShsetr®1 "Sits®;

worked hard . . . attended ihfee grernfforar

citizens' center and made many dfe®qsSte®3S

friends" 96 L.Ed.2d at 453. dEm W / m n m v/.,,

Kemp, 809 F.2d 702 (11th Cir.- lift®

state emphasized that the vidt&m Braffl f t m e m

"an honor graduate in high school '• sas

about to enter college.36 A piroser;

See McCleskey v„

L. Ed. 2d 262, 295 n. 4 (1987) (("•SSmmsB

studies indicate that . . . of fsatSersi vWhxss'

victims are physically attractive xcBCjedwr

harsher sentences than defsaffcasstss wiifBh, less attractive victims.")

3 6 8 09 F.2d at 7 i 3;- 4% m»31S

(Johnson, J., concurring and da'SsenrtiiHg)),7

see also Moore v. Zant. 722 F«,kd ©a®,, ®5i-

52 (11th Cir. 1984) ; Vela v. EsteJle„ TOD®

F.2d 954 (5th Cir. 1983) (vikcfcim <& stfflrr

athlete and social worker: ?a$s»iistti2ingi

underprivileged children).

39

well find virtually incomprehensible a

request that he or she decide which of

these personal characteristics militated

for or against the death penalty. It is

difficult to imagine how a juror, or a

member of this Court, would go about

deciding whether, and if so to what

degree, a sentence of death would be

supported by evidence that the victim was

pious, diligent, friendly, a registered

voter, a regular participant in senior

citizen activities, or had good grades.

It is equally difficult to imagine how an

appellate court could "rationally

review[]" the correctness of a capital

sentence that turned on a jury's

assessment of the moral or societal value

of the victim. Godfrey v. Georgia. 446

U.S. 420, 428 (1980).

In assessing whether a particular

sentencing system comports with the eighth

40

amendment, this Court refers it®

values reflected in state

Thompson v. Oklahoma. 101 L.EduSHfi WGS2„ TflblD

(Stevens, J.), 739-42 fSa33Bliiaiw

dissenting) (1988). V i e s i s ® ttarf

context, a sentencing scdasme. wimssfe

permitted jurors to rely on t&aaiisr gjsxsGjsafl

opinions about a victim's chmasEssfeKr <amii

value to society would be ® u$mikcpe_:,, awB

virtually unprecedented, 3BSsEEi53aifcilarm.»

Among the 37 states which afflSiksrEEiis?̂: ttfee

imposition of capital punishirceitfc,, ttherte iiis

not a single statute which aiî Hataariî ss sb

sentencing jury or judge to cxamsiidter iites

"personal characteristics" off .the vcictnap,,-

or to assess the victim 's? "*s?asIhsBB ttss

society." The South CarolLiiarra (ÊpiiitailJ

statute does not authorize a jjjiiry it®

attempt to consider such f aethers «

Many states, as Justice White

observed in Booth, 96 L.Ed.2d at 458 n.2.

41

do single out certain primarily

governmental positions, particularly

police officers, for special treatment,

either in defining capital murder or in

the statutory list of aggravating

factors.37 But these statutes share two

characteristics which emphasize the

constitutional defects in petitioner's

proposal. First every one of these

statutes identifies specifically which

government functions may — and by

omission may not — be accorded particular

value in the sentencing process, leaving

the jury or judge no discretion whatever

in the matter. In South Carolina, for

example, the legislature has specified

that the killing of a police officer, a

judge or a prosecutor is an aggravating

factor. S .C . Code Ann. § 16 — 3 —

' We set forth a list of those statutes in Appendix A.

42

20(c) (a) (5) — (7) (1986). If neither these

nor any of the other statutory aggravating

factors is present, a South Carolina jury

cannot impose the death penalty,

regardless of whether it believes the

murder victim — a mayor, for example—

was of great value to society; conversely,

if the victim was a police officer, the

jury must find the presence of an

aggravating factor, even though it may

believe the particular officer involved

was so corrupt or inept that he should

have been dismissed.

Second, all of the state capital

statutes concerning killings of police,

corrections, judicial and prosecution

officials apply only to murders occurring

in the course of, or in connection with,

the victim's duties. Thus in South

Carolina the killing of a police officer

is only an aggravating factor if the

43

officer was murdered "while engaged in the

performance of his official duties". S.C.

Code Ann. § 16-3-20(c)(a)(7).38 These

statutes protect essential government

functions, they do not attach increased

importance to the lives of individuals as

such. No state in the union attaches

greater culpability to the killing of an

adulterer by a jealous spouse', or to the

random killing of a man on a park bench,

solely because the victim was an off duty

police officer.

In his dissent in Booth Justice White

argued that "determinations of appropriate

sentencing considerations are peculiarly

questions of legislative policy". 96

L. Ed. 2d at 458. It is precisely that

38 See Appendix A. A number of

other states address this issue, not by

referring to the killing of certain

officeholders, but by attaching special

significance to any murder committed for

the purpose of interfering with a

governmental activity. See Appendix B.

44

legislative policy that is absent in this

case. The Attorney General of South

Carolina argues that a jury ought treat as

an aggravating factor the "status" of the

victim as "a judge, a policeman, or a

street minister". (Pet. Br. 56). The

simple answer is that the South Carolina

legislature has made a different choice,

to treat as an aggravating factor only the

killing of judges and policemen, but not

the murder of a "street minister," and to

do so, not for every individual who has

that particular "status", but only for

individuals killed during or in connection

with the conduct of their official duties.

Petitioner asks this Court to authorize

jurors in South Carolina to "substitute

their own views for those of the state

legislature as to the particular

substantive factors to be considered in

sentencing a capital defendant."

45

California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992, 1000

(1983) .

We do not suggest that the South

Carolina legislature could not extend such

special protection to additional functions

which it thought of critical value to

society. Other states have constitu

tionally chosen to do so, treating as

aggravating factors the killing, in

connection with their official duties, of

witnesses, jurors, and defense lawyers. A

state legislature might choose to attach

particular value to a non-governmental

function; a Washington statute, for

example, treats as an aggravating factor

the killing of a reporter in order to

hinder an investigation of the killer.

Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 10.95.020(10)

(1981). But the selections of the public

or quasi-public functions deserving such

special protection "are peculiarly

46

questions of legislative policy."

California v. Ramos. 463 U.S. at 1000.

Neither Sought Carolina nor any other

state treats as an aggravating factor the

killing of a minister or registered voter,

and it is entirely inconceivable that any

legislature in the United States would

authorize a jury, in deciding whether to

impose the death penalty, to consider

whether the victim was or was not

religious, or adhered to a particular

religious creed. To uphold a death

sentence based on considerations which no

legislature has authorized or would

approve would be to stand eighth amendment

jurisprudence on its head.

C. THE CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUE

PRESENTED BY THIS CASE SHOULD BE

DEFINITIVELY RESOLVED

Because no statute authorizes a

sentencing decision to be based on a

jury's or judge's personal opinions about

47

what constitutes moral or societal worth,

there are only a handful of reported cases

in which a prosecutor sought to win a

capital sentence on such a basis. The

instant case is particularly unique

because the prosecutor asked the jury to

ground its sentencing decision on the fact

that the victim was "a religious person".

State v. Gathers. 369 S.E.2d 140, 143

(S.C. 1988). Although that argument

raises serious problems under the

Establishment Clause, we believe it would

be inappropriate to resolve this case on

first amendment grounds; to do so would be

to require respondent to run the risk that

on remand the prosecutor would again urge

the jury to impose the death penalty

because the victim in this case was a

registered voter. That argument violated

the eighth and fourteenth amendment when

it was advanced at the original sentencing

48

hearing, and the Court should not leave

the prosecutor free to repeat that

violation.

Equally importantly, the efficient

administration of justice would be ill-

served by a decision in this case which,

rather than addressing the permissi

bility as such of basing a sentencing

decision on the perceived- moral and

societal worth of the victim, dealt only

with the particular personal characteris

tics — piety and voter registration — on

which the prosecutor happened to rely in

this case. A decision by this Court

leaving open the possibility that other

personal-characteristic arguments might be

upheld would inevitably encourage a form

of abuse that has hitherto been com

paratively rare; the capacity of a

constitutional decision to actually

encourage misconduct was well illustrated

49

by experience under Swain v. Alabama. 380

U.S. 202 (1965). See Batson v. Kentucky.

476 U.S. 79 (1986).

In the absence of a definitive

resolution of the constitutionality of

personal characteristic arguments, the

prosecutor on remand in this case, like

prosecutors in literally thousands of

capital cases in years ahead, would be

invited to seize upon some other personal

characteristic of the victim as a basis

for a sentence of death. A decision on

eighth or fourteenth amendment will

pretermit this entire problem, but a

decision addressing only the specific

prosecution arguments in this case would

in all probability launch a major new

branch of constitutional jurisprudence,

requiring the courts to assess on a case

by case basis the constitutionality of

sentences based on every conceivable

50

function valuable to society that a given

victim might have played, and on any

imaginable laudable personal character

trait that a particular victim might have

possessed.

Equally seriously, for this Court to

suggest that the lives of some human

beings may constitutionally be accorded

greater value and protection would

necessarily legitimize and encourage the

view that other lives are entitled to

less. The dangers with which the framers

of the equal protection clause were

concerned remain real, if more complex,

today. The failure of the criminal

justice system to provide protection for

wives from spousal abuse, for example,

remains a widespread problem. Judicial

suggestions that lethal attacks on certain

types of individuals are less deserving of

punishment would inevitably shape the

51

willingness of the police to investigate

such crimes, and would imply to members of

the public that such murders enjoy a

degree of official sanction or tolerance.

II. THE PROSECUTOR'S CLOSING

ARGUMENT ENCOURAGED THE JURY TOBASE THE SENTENCING DECISION ON

ITS PERCEPTION OF THE MORAL ORSOCIETAL WORTH OF THE CRIMEVICTIM

Booth, of course, did not hold that

evidence regarding the personal

characteristics of a victim may never be

introduced or referred to by a prosecu

tion; on the contrary the Court observed

in Booth that in a particular case such

evidence may be relevant to a material

issue regarding either guilt or

sentencing. 96 L.Ed.2d at 451 n.10.

Evidence regarding the religious views of

a victim, or defendant, may in some

instances be relevant to such a legitimate

52

issue.39 Booth admonished, however, that

the courts must assure that the probative

value of evidence regarding the personal

characteristics of a victim outweighs any

prejudicial effect. Id.40 The courts

must also be certain that the purported

relevance of personal-characteristic

In a murder prosecution arising

out of a fight between the* victim and

defendant, for example, it might be of

controlling importance which participant

had initiated the fight and which was

defending himself; in resolving that issue

a jury might well consider whether either

participant adhered to moral views—

whether of a sectarian or secular origin

— which condemned violence other than in

self defense. At a sentencing hearing a

defendant's attitude towards violence

would be material to his future

dangerousness, Franklin v. Lvnaucrh. 101

L.Ed.2d 155, 168 (White, J.) (1988), and

that attitude might be demonstrated by the

moral tenets to which he adhered, whether

they were the principles of his purely

personal philosophy, of the Ethical

Culture Society or of an organized religious group.

Brooks v. Remo. 762 F.2d 1383,

1409 (5th Cir. 1985); Moore v. Kemo. 809

F* 2d 702, 748 (11th Cir. 1987) (Johnson,

J., concurring and dissenting).

53

evidence or argument does not itself turn

on unreliable or class based stereotypes

or assumptions.41

The instant case involves, not the

admissibility of evidence, but the content

and likely impact on the jury of the

prosecutor's argument at the penalty phase

of the trial. A substantial portion of

the prosecutor's closing argument dwelt on

the religious views of the victim. The

South Carolina Supreme Court concluded

that "[t]hese remarks conveyed the

suggestion appellant deserved a death

41 In the instant case, for

example, the South Carolina Attorney

General appears to suggest that detailed

comments about the religious character of

the victim were appropriate because that

evidence indicated that the victim was

less able or inclined to defend himself as

a result of his piety. If religious

belief actually tended to render the pious

incapable of using force against others,

the United States Army would not have a

large corps of chaplains, and words like

"crusade" and "jihad" would not be part of

our vocabulary.

54

sentence because the victim was a

religious man and a registered voter." Id.

Petitioner does not dispute this

description of the unavoidable effect on

the jury of the state's closing argument,

and could not plausibly do so. The

prosecutor's closing remarks are devoid of

any contention that the victim's piety or

voter registration were evidence of some

other legally relevant fact; the

prosecutor baldly dwelt at length on

several aspects of the victim's character,

and admonished the jury to consider them

when deciding on the appropriate sentence.

In the absence of a clear and unequivocal

argument specifically relating a victim's

personal characteristics to some other

factor which a jury might legitimately

consider, any prosecutorial reference to

such characteristics will necessarily

suggest that the characteristics are

55

sufficient by themselves to support a

sentence of death. No juror could have

understood the prosecutor's remarks in the

instant case in any other way.

Petitioner urges, however, that the

validity of the jury's sentencing decision

does not depend on the objective meaning

of the prosecutor's closing remarks, but

turns instead on the subjective intent

with which the prosecutor spoke. (Pet. Br.

45). So long as the prosecutor did not'

actually intend to encourage the jury to

vote for death because of the victim's

piety and voter registration, the state

appears to contend, it simply is not

relevant that the actual remarks made by

the prosecutor had precisely that effect.

Petitioner relies heavily on the decision

in Donnelly v. DeChristoforo. 415 U.S. 637

(1974) , that the courts will not "lightly

infer that a prosecutor intended" to

56

violate the constitutional rights of a

defendant. (Pet. Br. 45).

The bona fides of the prosecutor's

argument in this case, we submit, are not

the controlling issue. It was the jury,

not the prosecuting attorney42, which

fixed the sentence of death, and if there

was a significant danger that the jury

based its decision on a constitutionally

impermissible consideration — as was

surely the case here — it would be of no

significance that the prosecutor harbored

deeply felt but never articulated hope

that the jury would not do so. "The

guestion ... is not what" the prosecutor

intended, "but rather what a reasonable

juror could have understood the [argument]

Of course, if a prosecutor's decision to seek the death penalty were

tainted by a constitutionally imper

missible consideration, that penalty could

not stand. See McCleskev v. Kemp. 95 L.Ed.2d 262 (1987).

57

as meaning." Francis v. Franklin. 471

U.S. 307, 315-16 (1985); see California v.

Brown. 93 L.Ed.2d 934, 940 (1987). This

case, unlike Donnelly. 416 U.S. at 613,

does involve the violation of a specific

substantive constitutional rights, not

merely a general claim of unfairness.,

See Caldwell v, Mississippi. 472 U.S. 320,

339-40 (1980) . We urge that the South

Carolina Supreme Court correctly focused

on the objective meaning of the

prosecutor's closing remarks, and properly

eschewed any inguiry into the prosecutor's

subjective intent.

Our advocacy of this objective

standard, however, should not be

understood to suggest that there is any

possibility that the prosecutor in this

case did indeed act in good faith. On the

contrary, the record reveals a consistent

and extraordinarily persuasive effort to

58

bias the jury's decision — at the guilt

as well as the penalty phase — with

concern for the religious views of the

victim. Although the victim in this case

had no religious training or position, the

prosecutor referred to him as "Reverend"

or "Reverend Minister" Haynes on 4

occasions in his opening statement, 13

times in his closing statement on guilt,

and 16 times during his closing statement

regarding penalty.43 At the beginning of

the trial the prosecutor emphasized to the

jury that the victim was "a very, very

religious person" who "had many, many

43 Tr. 554-55, 1036-56, 1205-11.

The only foundation of these references

was an isolated statement by the victim's

mother that the victim liked to call

himself Reverend Minister. Id. at 563.

Neither the victim's mother nor any other-

witness ever themselves referred to the

victim as Reverend. In colloquy with the

trial judge outside of the presence of the

jury, the prosecutor referred to the

victim simply as "Richard Haynes." id. at

59

religious items — Bibles, rosaries,

statues."44 In his closing argument at

the end of the guilt phase, the prosecutor

urged:

[P]ut in your mind's eye, if you

would, the perspective of

Reverend Minister Rickey Haynes.

What do we know about him? ....

[H]e was a religious person.

You will have his Bibles there.

You will see his rosary beads.

His statues of little angels.45

The critical factual issue at the guilt

phase was whether Gathers was actually the

person who stabbed and sexually assaulted

the victim;46 the Bibles, angels and

rosary beads obviously could not help to

identify the victim's assailant. Even if

the victim's religious views had been

44 Tr. 553; see also id. at 554

("This religious person — who, by the

way, called himself Reverend Minister

Haynes.")

45 Tr. 1051.

46 Tr. 1032-77.

60

relevant to some issue at the penalty

phase — which they clearly were not — no

legitimate purpose was served by the

prosecutor's insistence on reading to the

jury the full text of a prayer that had

been in the victim's possession, or by the

repeated references to the religious

objects in the victim's possession at the

time of the killing. It is not unduly

cynical to suggest that none of this would

have occurred had the victim adhered to

non-orthodox religious views, and had in

his possession not an angel, a bible, and

the Game Guy's Prayer, but a voodoo doll,

a satanic tract, and a blessing written by

the Ayatollah Khomeini.

The state's effort to justify the

prosecutor's conduct is entirely

unavailing. In this Court the state does

not even attempt to provide any

explanation of the reading of the Game

61

Guy's Prayer, the repeated reference to

the victim's bibles, rosary beads, and

angels, or the closing argument about

Haynes' voter registration card. The

Attorney General asserts that some

reference to the victim's religion was

appropriate because "[s]imply put, it was

the state's theory of the case that the

motive and reason that Ricky Haynes was

assaulted and murdered was because he ....

was willing to talk to people all the time

about the Lord from the park bench." (Pet.

Br. 46) . In fact the theory of the case

which the prosecutor actually presented to

the jury was precisely the opposite—

that Haynes was attacked after he refused

to talk to his assailants,47 and that

Gathers was particularly culpable because

he was indifferent to the fact that his

47 Tr. 554, 631, 1053-54.

62

victim happened to be a religious

person.48

The state urges, in the alternative,

that under Booth a prosecutor may indeed

urge a jury to impose the death penalty

based on the personal characteristics of

the victim, so long as the evidence on

which the prosecutor relies was first

introduced for some other reason. (Pet.

Br. 22, 24, 47, 50). Once testimony

regarding Haynes' religious views had been

admitted for another purpose, the state

suggests, the prosecutor was free to argue

that it was a more serious crime to kill a

pious man than to kill an atheist or an

agnostic. Were that the law, a prosecutor

could constitutionally urge a jury to

impose capital punishment because the

Tr. 1208 ("[T]his defendantDemetrius Gathers cared little about the

fact that [Haynes] is a religious person").

63

victim was white, or belonged to the same

religious denomination as the jurors or

supported a particular political party, so

long as the underlying facts had already

been disclosed to the jury for other

reasons.

CONCLUSION

When most of North America was still

an untamed wilderness, Sir Wil-liam Hawkins

wrote that it was equally murder to kill

"any person, whatsoever nation or religion

he be of, or of whatever crime attainted."

A Treatise of the Pleas of the Crown, v.

1, p. 80 (1716).49 Two and a half

4y See also W. Blackstone,

Commentaries on the Laws of England, v.

iv, pp. 197-98 (murder includes the

killing of any person "'under the Kings

peace,' at the time of the killing.

Therefore to kill an alien, a Jew, or an

outlaw, who are all under the King's peace

and protection, is as much murder as to

kill the most regular-born Englishman")

(1765) ; T. Wood, An Institute of the Laws

of England. 352 (murder to kill any

"reasonable creature, man or woman,

subject or alien; whether attainted of

64

centuries of jurisprudence have not

improved upon that formulation. This case

does not call for the invention of any

new, unprecedented legal theory; we ask

only that the Court adhere to principles

of justice that were already of ancient

vintage when they were written into the

Constitution by the framers of the eighth

and fourteenth amendments. The decision

treason or felony, . . . Christian or

heathen. And the reasonable creature must

be born alive.") (3rd ed. 1724).

65

of the South Carolina Supreme Court should

be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

RICHARD H. BURR, III

GEORGE H. KENDALL

ERIC SCHNAPPER*

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

Attorneys for Amici

*Counsel of Record

VIVIAN BERGER

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Of Counsel

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX A

CAPITAL STATUTES CONCERNING

PUBLIC OR QUASI-PUBLIC OFFICIALS

Alabama Code (1982)

§13A—5-40 (a)(5) (law enforcement official

when "on duty or because of some

official or job related act")

§13A-5-40(a)(7)(present or former federal

or state official if murder "stems

from or is related to his official

position act or capacity"*)

Arkansas Code Annotated (1987 Supp.)

§5-10-101(a)(3)(law enforcement or correc

tions officer, firefighter, judge,

court official, parole or probation

officer, or military personnel "when

such person is acting in line of

duty")

§5-10-101(a)(5)(holder of any public

office "filled by election or ap-

la

pointment or a candidate for public

office")

California Penal Code (1987 Supp.)

§190.2(a)(7)(peace officer whom defendants

"knew or should reasonably have

known" was "engaged in the perform

ance of his duties" or who was killed

"in retaliation for the performance

of his official duties")

§190.2(a)(8)(federal or state law enforce

ment officer whom the defendant "knew

or should reasonably have known" was

"engaged in the performance of his

duties" or who was killed "in

retaliation for the performance of

his duties")

§190.29a)(9)(fireman whom defendant "knew

or reasonably should have known . . .

was a fireman engaged in the perform

ance of his duties")

2a

§ 190.2(a) (10) (witness killed to prevent or

in retaliation for testimony)

§ 190.2(a) (11) (prosecutor killed "in reta

liation for or to prevent the per

formance of the victim's official

duties")

§190.2(a)(12) (present or former judge

killed "in retaliation for or to

prevent the performance of the

victim's official duties")

§ 190.2(a) (13) (present or former federal,

state or local official killed "in

retaliation for or to prevent the

performance of the victim's official

duties")

Colorado Revised Statutes (1986)

§ 16-11-103(6) (c) (firefighter, elected

official, state or local peace

officer, present or former federal

law enforcement officer "killed . . .

while such person was engaged in his

3a

official duties, and the defendant

knew or reasonably should have known

that such victim was such a person

engaged in the performance of his

official duties, or the victim was

intentionally killed in retaliation

for the performance of his official

duties.)

§ 16-11-103(6) (k) (witness to a criminal

offense killed to prevent arrest or

prosecution)

Delaware Code Annotated Title 11 (1979)

§636(a)(4)(law enforcement or corrections

officer or fireman "while such

officer is in the lawful performance

of his duties")

§4209(e) (1) (c) (law enforcement or correc

tions officer or fireman "while such

victim was engaged in the perform

ance of his official duties")

4a

§4209(e)(1)(d)(prosecutor, judge or state

investigator "during, or because of,

the exercise of his official duty")

§4209(e)(1)(g)(witness killed to prevent

testimony regarding a crime)

Georgia Code Annotated (1979)

§27-2534.1(b)(5)(present or former judge

or prosecutor "during or because of

the exercise of his official duties")

§27-2534.1 (b) (8) (peace or corrections

officer or fireman "while engaged in

the performance of his official

duties")

Idaho Code (1982)

§ 18-4003(b) (judge, executive officer,

police officer, fireman, prosecutor

or court officer "who was acting in

the lawful discharge of an official

duty, and was known or should have

been known by the perpetrator of the

murder to be an officer so acting")

5a

§19-2515(g)(9)(present or former peace

officer, judge or prosecutor killed

"because of the exercise of official

duty")

§ 19-2515(g) (10) (witness or potential wit

ness in a criminal or civil proceed-

ceeding "because of such proceeding")

Illinois Annotated Statutes. Chapter 38

(1987 Supp.)

§9-1(b)(1)(peace officer or fireman killed

(1987)

"in the course of performing his

official duties" if defendant "knew

or should have known that the

murdered individual was a peace

officer or fireman")

§9-1(b) (2) (corrections official killed "in

the course of his official duties")

§9-1(b)(8)(witness or informant against

defendant in a criminal proceeding)

6a

Indiana Code Annotated (1987 Supp.)

§35-50-2-9(c)(b)(murder of "a corrections

employee, fireman, judge, or law en

forcement officer and either (i) the

victim was acting in the course of

duty or (ii) the murder was motivated

by an act the victim performed while

acting in the course of duty")

Kentucky Revised Statutes Annotated (1981)

§532.030(a) (5) (prison employee killed

while "engaged . . . in the perform

ance of his duties" by an inmate)

§532.030(a)(7)(police officer "engaged at

the time of the act in the lawful

performance of his duties")

Louisiana Revised Statutes (1982)

§14.30(2)(law enforcement corrections,

parole or probation officer, judge or

prosecutor while "engaged in the

performance of his lawful duties")

7a

Art. 27 §413(d)(1)(law enforcement officer

"murdered while in the performance of

his duties")

Missouri Annotated Code (1987 Supp.)

§565.012(2)(5)(present or former judge,

prosecutor or elected official

"during or because of the exercise of

his official duty")

§565.012(2)(8)(peace or corrections offi

cer or fireman "while engaged in the

performance of his official duty")

Montana Code Annotated (1985)

§46-18-303 (6) (peace officer "killed while

performing his duty")

Nebraska Revised Statutes (1985)

§29-2523(1)(g)(any official "having cus

tody of the offender or another")

Nevada Revised Statutes Annotated (1986)

§200.033(7)(peace officer or fireman

"killed while engaged in the perform-

Maryland Code Annotated (1987)

8a

ance of his official duty or because

of an act performed in his official

capacity, and the defendant knew or

reasonably should have known that the

victim was a peace officer or fire

man" )

New Mexico Statutes Annotated (1978)

§31-20A-5(A)(peace officer "acting in the

lawful discharge of an official duty

when he was murdered)

§31-20A-5(D)(corrections official killed

by prison inmate)

§ 31—20A-5(F) (witness to a crime to

prevent, or in retaliation for

testimony)

New Jersey Statutes Annotated (1988 Supp.)

§2C:11-3(c)(4)(b)(certain public servants

killed "while the victim was engaged

in the performance of his official

duties or because of the victim's

status as a public servant")

9a

North Carolina General Statutes (1981

Supp.)

§15A-2000(e)(g)(law enforcement or

corrections official, or present or

former judge, prosecutor, juror or

witness against perpetrator if killed

"while engaged in the performance of

his official duties because of the

exercise of his official duty")

Ohio Revised Code Annotated (1982)

§2929.04(A)(1)(president, president-elect,

vice-president, vice-president-elect,

governor, governor-elect, lieutenant-

governor, lieutenant-governor elect,

or candidate for any of those

offices)

§2929.04(A)(6)("law enforcement officer

whom the offender knew to be such,

and either the victim was engaged in

his duties at the time of the

offense, or it was the offender's

10a

specific purpose to kill a law

enforcement officer")

Oklahoma Statutes (1987)

§701.12(law enforcement or corrections

officer killed "while in performance

of official duty")

Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes Anno

tated (1982)

§9711(d)(1)(law enforcement or corrections

officer or fireman "killed in the

performance of his duties")

§9711(d)(s)(witness to felony committed by

perpetrator, killed to prevent testi

mony)

South Carolina Code Annotated (1986 Supp.)

§16-3-20(a)(5)(judge or prosecutor "during

or because of the exercise of his

official duty")

§16-3-20(a)(7)(law enforcement or correc

tions officer or fireman "while

11a

engaged in the performance of his

official duties")

South Dakota Codified Laws (1988)

§23A-27A-1(4)(present or former judge or

prosecutor while "engaged in the

performance of his official duties or

where a major part of the motivation

for the offense came from the

official actions of" the victim)

§23A-27A-1(7)(law enforcement or correc

tions officer or fireman "while

engaged in the performance of his

official duties")

Tennessee Code Annotated (1982)

2-203 (i) (9) (law enforcement or cor-

rections officer or fireman "who was