Katzenbach v. McClung Supplemental Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Katzenbach v. McClung Supplemental Brief for Appellees, 1964. 7c2903a3-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e7d2769d-0ba0-4157-9372-44dea0967573/katzenbach-v-mcclung-supplemental-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

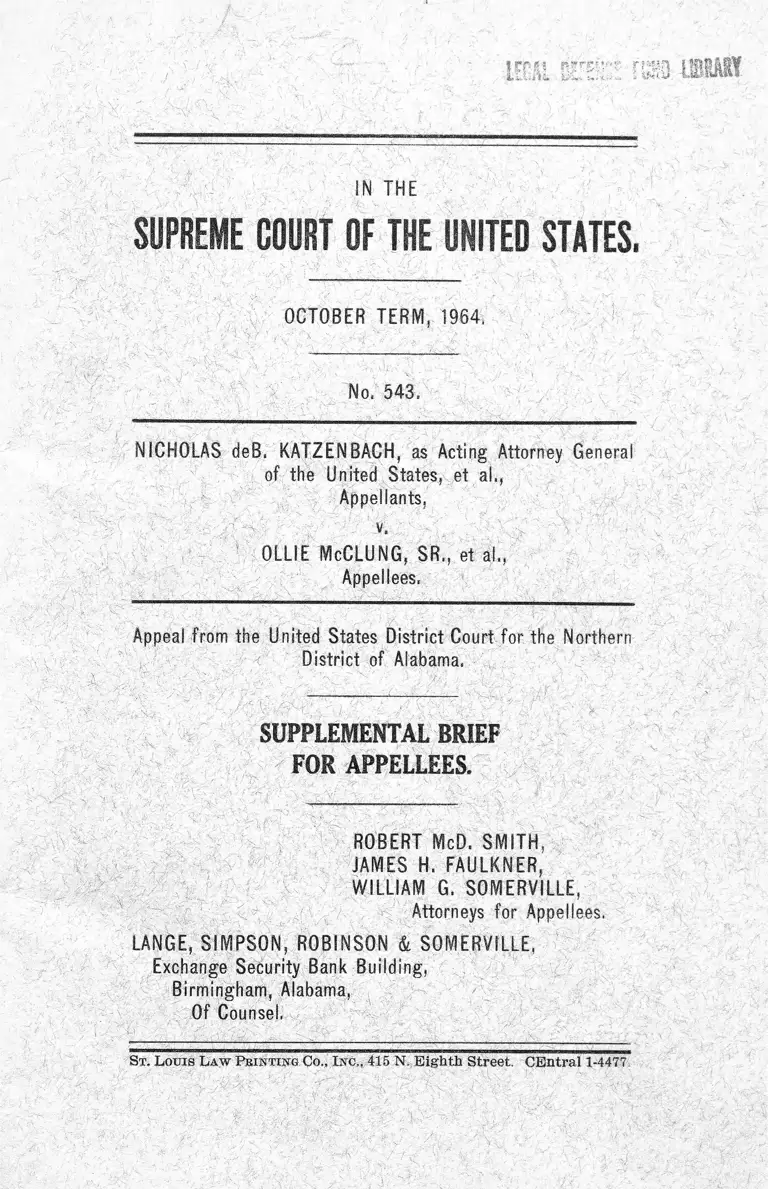

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1964.

No. 543.

NICHOLAS deB, KATZENBAGH, as Acting Attorney General

of the United States, et al,,

Appellants.

v,

OLLIE McCLUNG, SR., et al.,

Appellees,

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Alabama,

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

FOR APPELLEES.

ROBERT McD. SMITH,

JAMES H. FAULKNER,

WILLIAM G. SOM ERVILLE,

Attorneys for Appellees.

LANGE, SIM PSON, ROBINSON & SOM ERVILLE,

Exchange Security Bank Building,

Birmingham, Alabama,

Of Counsel.

St. L ouis Law P rinting Co., I nc,. 415 N.. E igh th Street. C E ntral 1-4477

m fflfM

INDEX

Page

Statement ....................................................................... 1

Argument .................................................................... 2

Introduction ................................................................... 2

I. The Legislative History Shows That Congress

Neither Could Have Nor Did Make the Finding

Claimed by Appellants ...................................... 4

1. There Was Nothing Before Congress to Sup

port the Finding Claimed ........................... 5

2. No Such Finding Was in Fact M ade............. 11

II. Prior Statutes Provide No Precedent for Title II 16

1. Statutes Regulating Goods or Activities “ In

Commerce” ...................................................... 17

(a) Statutes Regulating the Movement of

Goods in Commerce ................................. 17

(b) Statutes Regulating Instrumentalities of

Commerce .................................................. 20

2. Statutes Extending Interstate Regulation to

Commingled Intrastate Activities ................ 21

(a) Statutes Regulating “ Local” Activities

in Association With Control of Inter

state Instrumentalities ............................ 21

(b) Statutes in Which “ Local” Activities

Are Reached in Association with Eco

nomic Regulation of Interstate Commodi

ties ............................................................ 22

(c) Statutes in Which Control of Local Ac

tivities Is Necessary to the Effective

Control of the Interstate Movement of

Harmful Articles ...................................... 27

11

3. Statutes Regulating Local Activities When

Found on an Ad Hoc Basis to Affect Com

merce ............................................................... 30

III. A Mere Hypothetically Rational Basis for the

Exercise of Federal Power Is Not Sufficient . . . 37

Conclusion .................................................... 41

Appendix A ................................................................... 43

Oases Cited.

Apex Hosiery Co. v. Leader, 310 U. S. 469, 485, 498 .. 32

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U. S. at 239........................... 27

Baltimore & 0. R. R. v. I. C. C., 221 IT. S. 612 . . . .22, 34

Board of Trade v. Olsen, 262 U. S. 1 ........................23, 24

Cnrrin v. Wallace, 306 U. S. 1, 10........................... 23,24

Duplex Printing Press Co. v. Deering, 254 U. S. 443 12

Federal Trade Commission v. Mandel Bros., Inc., 359

IT. S. 385, 391 ...........................................................28,35

Heiner v. Donnan, 285 U. S. 312................................... 27

Industrial Ass’n v. United States, 268 U. S. 6 4 ......... 33

J. L. Brandeis & Sons v. N. L. R. B., 142 F. 2d 977,

980 (C. A. 8) ............................................................ 31

Kentucky Whip & Collar Co. v. Illinois Cent. R. R.,

299 U. S. 334, 352-53 ............................................. 18,19

King v. United States, 344 U. S. 254, 267-76 ............. 30

Kinsella v. United States ex rel. Singleton, 361 U. S.

235 .............................................................................. 38

Lorain Journal Co. v. United States, 342 U. S. 143 . . . 33

Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch. 137 ........................... 41

McDermott v. Wisconsin, 228 U. S. 115, 135 .........18,19

Moore v. Mead’s Fine Bread Co., 348 U. S. 115......... 33

Mulford v. Smith, 307 U. S. 38 ...............................23, 24

Ill

N. L. R. B. v. Denver Bldg, and Constr. Trades Conn

ell, 341 U. S. 675, 683-84 ......................................

NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U. S. 1

North Carolina v. United States, 325 U. S. 507, 511 . .

Reid v. Covert, 354 U. S. 1 ..........................................

Roland Elec. Co. v. Walling, 326 U. S. 657, 669.........

Second Employers ’ Liability Cases, 223 U. S. 48 . . . .

Shreveport Rate Case, 234 U. S. 342, 353.............22, 24,

Southern Ry. v. United States, 222 U. S. 20 .............22,

Stafford v. Wallace, 258 U. S. 495 ...........................

Tot v. United States, 319 U. S. 463...............................

Townsend v. Yeomans, 301 U. S. 441 ........................

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U. S. 86 ......................................

United States ex rel. Toth v. Quarles, 350 II. S. 11 . . .

U. S. v. Carolene Products Company, 304 U. S. 144 . ..

United States v. Darby, 312 U. S. 100, 110, 117,

118 .....................................................19,23,25,

United States v. Employing Plasterers Ass’n., 347

U. S. 186 ...................................................................

United States v. Ferger, 250 U. S. 205 ...................... 27,

United States v. Five Gambling Devices, 346 U. S.

411, 446-48, 460 ..................................................17,27,

U. S. v. St. Paul, M. & M. Ry., 247 U. S. 310 .........

U. S. v. Sullivan, 332 U. S. 689, 696............. 19, 27, 28, 29,

United States v. Women’s Sportswear Ass’n, 336

U. S. 460 ...................................................................

United States v. Wrightwood Dairy Co., 315 U. S. 110,

121 .................................................... 23,25,26,

United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 332 U. S. 218 . . . .32,

Virginian Ry. v. System Federation No. 40, 300 U. S.

515, 554-57................................................................22,

Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U. S. I l l ................ 23, 25, 34,

31

40

30

38

19

22

,30

34

24

27

36

39

38

36

40

31

34

34

12

35

32

30

33

35

40

IV

Statutes Cited.

Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, 7 U. S. C.,

§§1281 et seq.............................................................23,26

Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act of 1937, 7

U. S. C., §§ 601, 608 ......................................23, 25, 26, 30

Ashurst-Summers Act, 49 Stat. 494 ............................. 18

Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, 29 U. S. C., §§ 201

et seq......................................................................23,26,35

Food and Drug Act of 1906, 34 Stat. 768 .................. 18

Grain Futures Act of 1922, 42 Stat. 998 .................. 23, 35

Interstate Commerce Act, 49 U. S. C., § 13 (4) ....... 30

National Labor Relations Act, 29 TJ. S. C. 151 et seq. 31

Robinson-Patman Act, 15 U. S. 0., § 13 (a) .............. 33

Sherman Act, 26 Stat. 209, 15 U. S. C., § 1 et seq........ 31

Tobacco Inspection Act, 7 U. S. C., § 511a......... 23,26,35

15U.S. C.,§ 69 ........................................................18,28,35

15 U. S. C., § 70 .............................................................. 18,35

15 U. S. €., § 692 ..................... 19

15 U. S. C., § 1172 ........................................................... 18

15 U. S. c., § 1231 .......... 35

18 u. s. a, § 1201 ............................................................ 18

18 U. S. C., § 1301 ........................................................... 18

18 U. S. C., §§ 2312-2317 ................................................. 18

18 U. S. C., § 2421 ........................................................... 18

21 U. S. C., §§ 61-63 .............. .......................................... 36

21U. S. C., § 331 ..................................................... 18,19, 27

21 U. S. C., § 347a ................................................... 25, 26, 35

29 U. S. C., §§ 206, 207 .................................................. 18,19

45 U. S. C., §§ 1-16 ......................................................... 21,35

45 U. S. C., § 51 .............................................................20,22

45 U. S. G, §§ 61-64 ..................................................... 20-22

45 TJ. S. C., §§ 151 et seq................................................. 22, 35

45U.S. C., §157 ................................................ 20

49 U. S. C., § 1 ............................................................... 20,22

49 U. S. C., § 26 ............................................................... 35

49 U. S. C., §81................................................................... 20

49 TJ. S. C., § 121 ............................................................27,35

V

Miscellaneous Cited.

Cong. Bee. 6237 (March 26, 1964) ............................... 6

Cong. Bee. 6308 (March 30, 1964) ............................... 12

Cong. Bee. 6832 (April 7, 1964) .................................. 13

Senate Beport No. 308, 81st Cong., 2nd Sess., 1950

U. S. Code, Cong. News, at 1973 ............................. 25

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF TIE UNITED STATES,

OCTOBER TERM, 1964,

No, 543,

NICHOLAS deB, KATZENBACH, as Acting Attorney General

of the United States, et a!,,

Appellants,

v,

OLL1E McCLUNG, SR,, et a!,,

Appellees,

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Alabama,

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

FOE APPELLEES.

STATEMENT.

On October 5, 1964, the Court granted the parties’

Joint Motion to Expedite Briefing and Oral Argument

providing inter alia for the filing of supplemental briefs

after oral argument.

This brief is filed pursuant to that order and is sub

mitted for consideration of the Court both in reply to the

opening brief of appellants and in response to certain

questions raised by the Justices during oral argument.

No further statement of the case or of the facts is

deemed necessary.

-—2 —

ARGUMENT.

INTRODUCTION.

In appellant’s brief and again in the Solicitor General’s

oral argument, it was stated that appellant’s major prem

ise is that Congress has the power to regulate intrastate

activities, not themselves a part of interstate commerce,

if they have a close and substantial relation to interstate

commerce. Appellees have repeatedly sought to make

it clear that they have no quarrel with that premise.

Appellant’s minor premise was to the effect that Con

gress “had ample basis upon which to find that racial

discrimination at restaurants which receive from out-of-

state a substantial portion of the food served, does, in

fact, impose commercial burdens of national magnitude

upon interstate commerce”. Brief for Appellants at 26.

It is with appellant’s minor premise as thus stated that

appellees take issue, on two basic grounds:

1. Congress made no such finding as claimed by

appellants.

2. There was no ample basis upon which any such

finding could have been made.

The point from which all argument in this case must

proceed is that the federal government is one of delegated

powers. Every statute enacted by the federal congress

must come within some specific power given under the

Constitution. In Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

Congress purported to exercise power given to it under

both the Interstate Commerce Clause and the 14th Amend

ment. The issues in this case present no question under

the 14th Amendment. If the statute may constitutionally

be applied to appellees, it must necessarily be because,

•— 3 —

as so applied, it comes within the authority given to

Congress under the Interstate Commerce Clause. The

broad principles upon which this issue must be resolved

are not in substantial dispute in this case. Appellants

concede that the activities of the appellees sought to be

regulated by the statute are local and intrastate; that

they are in no sense in, or a part of, interstate commerce.

Appellants further concede that in order for the activities

to be regulated in the manner attempted, there must be a

finding or showing that they bear a close and substantial

relation to interstate commerce. Finally, appellants con

cede that the statute makes no provision for a case-by

case determination of such a relationship (between dis

crimination in an individual restaurant and interstate

commerce) and thus concede one of the principal points

made in appellees’ opening brief. Nor do appellants argue

that the conclusive presumption of an effect on commerce

established under the so-called “food test” is valid. They

state:

We have no need to argue whether the fact that a

restaurant serves food which originated in other

States is a sufficient basis for the regulation. Brief

for Appellants at 36, 37.

They avoid that argument by attributing to Congress

a legislative finding to the effect that racial discrimination

at restaurants serving food, a substantial portion of

which has previously crossed state lines, imposes a com

mercial burden upon commerce. Thus, they undertake to

deny that the food test in Section 201 (c) is intended as

an evidentiary presumption of an actual effect upon com

merce and, instead, insist that it is merely a coverage

provision bringing an individual restaurant within the

scope of a finding claimed by appellants, in their minor

premise, to have been made by Congress.

Appellants present no argument on the first point raised

by appellees, i. e., that no such finding was made. They

are content to rest their case on that point by merely

urging that formal and explicit legislative findings are

not required. This hardly meets the question. Appellants

themselves, in stating their minor premise, necessarily

make the contention that a finding was made.1 Most of

their argument, however, is devoted to the second point

mentioned above, i. e., whether Congress had any basis

upon which such a finding could be based. In doing so,

they rely entirely upon the legislative history of the

statute.

I t is appellees’ contention that the legislative history

is heavily persuasive in their favor on both of these points.

It discredits the contention that any such finding was

made and it is wholly lacking of any support for such a

finding if one can be assumed.

I. The Legislative History Shows That Congress Neither

Could Have Nor Did Make the Finding

Claimed by Appellants.

At the outset, it should be pointed out that appellees

have never in this case relied primarily upon the legislative

history. It is the appellants who have done so. Ap

pellees have taken the position that the structure, arrange

ment and language of the statute itself are amply persua

sive that Congress made no such finding as is contended

by appellants. However, appellees regard their position

as supported by the legislative history. Moreover, they

believe that for reasons that will be shown, there was

nothing before Congress upon which any such finding,

particularly relating to food which has moved in com

merce, could have been based.

— 4 —

1 Appellants state that Congress “had ample basis upon which to

find, that racial discrimination, etc.” Brief for Appellants, at 26.

— 5 —

1. There Was Nothing Before Congress to Support the

Finding Claimed.

It is well to remember that appellants both in their

brief and in oral argument have relied almost entirely

upon certain testimony offered by the proponents of the

legislation before the Senate Committee on Commerce.

Significantly, appellants have at no time pointed to any

testimony before that Committee or any other committee,

or even in either house of Congress, that related to restau

rants serving food which has previously crossed state

lines or the fact that a customer selection practice at any

such restaurant would in any way result in a burden upon

commerce (as is specifically claimed by appellants in their

minor premise).

The history of the legislation that became the Civil

Eights Act of 1964 does not lend itself to a brief, com

prehensive summary. Early in the 88th Congress, a large

number of bills relating to civil rights in various aspects

were introduced in both houses of Congress. President

Kennedy had made recommendations concerning legisla

tion of this type in both February and in June of 1963. It

was clear from the beginning that a majority of the two

houses of Congress favored some kind of civil rights

legislation, but in the earlier stages there was considerable

disagreement as to the scope of the legislation. Public

accommodations provisions were included in many of the

proposed bills, but there was a wide disparity of opinion

as to what constitutional basis, if any, would support such

legislation.

At this juncture an administration-sponsored bill was

sent to the Senate. This was S. 1731. Although S. 1731

covered the general topics included in the House bill

ultimately passed, there were substantial differences in

structure, coverage, language and legislative technique.

Hearings on S. 1731 were conducted before the Senate

Committee on the Judiciary in 1963. In early 1964, the

Senate Committee on Commerce conducted hearings on

S. 1732 which pertained only to public accommodations.

Its provisions were identical with those in Title II of S.

1731. It was during the Senate Committee hearings that

the evidence relied upon by appellants in their brief was

offered. There was much discussion before the two Senate

committees of facts relating to the difficulty with which

Negroes plan trips, as well as to the economic effects of

riots, demonstrations and boycotts. Significantly, these

discussions were not directed at restaurants and at no

time was any consideration given to the movement of food

across state lines, or a possible burden upon that move

ment resulting from racial discrimination in restaurants.

This was not an oversight, for as will be shown, S. 1731

and S. 1732 did not purport to cover restaurants on the

basis of a food test like that now contained in the Civil

Eights Act of 1964. The Senate bills were not passed.

Meanwhile, the House of Representatives was consider

ing H. E. 7152. After hearings, the House Judiciary Com

mittee reported the bill out favorably, but H. E. 7152 as it

reached the House floor was a substitute bill that had not

been considered by that committee in its emerging form.

Senator Dirkson, who favored the legislation, later re

marked in the Senate, “ the bill [H. E. 7152] that is now

before us did not receive even a one-day hearing before

the House Judiciary Committee.” Cong. Eec. 6237 (March

26, 1964). The House of Representatives passed H. E.

7152 as reported from the committee. It then went to the

Senate in February of 1964.

In the Senate, Senator Morse tried desperately to have

the bill submitted to the Senate Committee on the Judiciary

in order that a legislative history for the benefit of the

courts could be made. Senator Morse’s motion to this

effect was defeated and the lengthy debates in the Senate

— 6 —-

7

began. In June of 1964, H. R. 7152 passed the Senate.

Although the Senate amended certain portions of the bill,

none of these is pertinent in any way to the issues raised

in this case. The public accommodations provisions were

not changed except in respects that are not here material.

When the bill was returned to the House, no further

amendment was effected. The bill was passed as it left

the Senate and became the Civil Bights Act of 1964 on

July 2, 1964.

Significantly, then, the Act that is now before the Court,

did not receive, in the words of Senator Dirkson, “ even a

one-day hearing before the House Judiciary Committee”,

and it received no hearing in any Senate Committee.

Since appellants in this case rely upon evidence ad

duced in the hearings before the Senate committees and

since appellees deny that there was any evidence offered

there to support any “ finding” of the type claimed by ap

pellants to have been made, it is appropriate, if not neces

sary, to take a closer look at the Senate bill as it was

written when those hearings were conducted.

S. 1731 and 1732 were alike except that the latter per

tained only to Title II. They were conceived on a dif

ferent basis from H. K. 7152. Sections 201 and 202 of

S. 1731 are attached as an appendix to this brief.2 Sec

tion 201 of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

formerly H. R. 7152, appears as an appendix to appel

lant’s jurisdictional statement.

When the two are laid side by side a number of ma

terial differences are immediately apparent. While a

detailed analysis of these differences would unduly

lengthen this brief and still fail to eliminate the necessity

2 The only difference between § 1732 and Title II of § 1731 was

section numbers. Only § 1731 is copied herein.

for actual comparison, a few general observations as to

the differences may be helpful:

First, S. 1731 contained specific legislative findings in

Section 201. There are no findings in Title II of the Civil

Eights Act of 1964.

Second, the findings in S. 1731 were primarily devoted

to interstate commerce, but also included a finding re

lating to the 14th Amendment. This is in Section 201(h).

Third, none of the findings in Section 201 of S. 1731

related specifically to restaurants. The only reference to

restaurants in the entire section was in Section 201(g)

which was directed at an alleged difficulty encountered

by business organizations in obtaining the services of

skilled workers in the professions. This was in no way

related to the matter of customer selection in a restaurant

using food from out of state or the movement of food

at all.

Fourth, retail establishments were specifically men

tioned in Section 201(e) in connection wfith the movement

of “ goods sold” , but restaurants, obviously treated hi

the bill as something different from a retail establish

ment, were not mentioned in that subsection.

Fifth, the term “ public accommodations” to categorize

the covered establishments was not used in S. 1731 as

was done in the Act finally passed by Congress. Thus

there is no counterpart to Section 201(b) of the Civil

Eights Act of 1964.

Sixth, there is no “ state action” criterion of coverage

in S. 1731, as is the case in the statute itself. Thus, while

power under the 14th Amendment was invoked generally

as evidenced by the findings, S. 1731 did not contemplate

the 14th Amendment as a separate criterion of coverage.

Seventh, S. 1731, unlike the present statute, covered

retail stores and other places “ which keep[s] goods for

9

sale.” Sec. 202(a)(3). This explains the reference in

the findings to retail establishments and the flow of goods

in the interstate market.

Eighth, restaurants are included in Section 202(a)(3),

but in a different generic sense from retail shops, etc.

The latter category is followed by a reference to ‘ ‘ other

public place which keeps goods for sale” , whereas res

taurants, etc., are followed by a reference to “ other pub

lic place engaged in selling food for consumption on the

premises” (Emphasis supplied).

Ninth, in S. 1731 there was no separate interstate com

merce test for restaurants as such. 202(a) (l)(i) of that

bill related to goods, services, etc., “ provided to a sub

stantial degree to interstate travelers.” Thus it was

similar to Section 201(c)(2) of the present statute (al

though not employing the concept of “ offers to serve”

and therefore both far clearer and more restricted).

Section 201(a) (3) (ii) applied where “ a substantial por

tion of any goods held out to the public by any such

place or establishment for sale, use, rent or hire has

moved in interstate commerce.” This subsection made no

reference to the food served by a restaurant but only

to the sale of “ goods” which, as noted above, is treated

separate from “ food” in paragraph 202(a)(3).

Finally and significantly, under Section 202(a) (3) (iii)

(of S. 1731 and S. 1732), there was a provision bringing

an establishment within the Act if “ the activities or

operations of such place or establishment otherwise sub

stantially affect interstate travel or the interstate move

ment of goods in commerce.” This provision necessarily

contemplated the determination of an actual effect upon

interstate commerce in each individual case. This, of

course, might be applicable to a restaurant. In fact,

except for a restaurant serving interstate travelers to a

substantial degree, it would be the only way a restaurant

would be covered under the Senate bills.

From the above (and certainly other differences can

be noted), it is apparent that the Senate committees

considering S. 1731 and S. 1732 were not confronted with

a proposed statute that in any respect relied upon a

restaurant’s mere serving of food that has crossed state

lines to bring it under the statute. Understandably

there was no reason for any such consideration on the

part of the two Senate committees. No evidence on the

point was offered because the proposed legislation simply

was not oriented in that direction.

Under S. 1731 a restaurant would have been covered if

its services, facilities, etc., were provided to a sub

stantial degree to interstate travelers. Certainly there

was evidence before the committees that interstate travel

of persons was impeded by discriminatory practices in

those facilities actually serving interstate travelers. Un

der Section 202(a) (3) (iii), a restaurant might also be

brought within the coverage of the Act if its activities

or operations in fact substantially affected interstate

travel or the interstate movement of goods in commerce

“ otherwise.” But this required an ad hoc determination

of an effect on commerce in each individual case as is the

case under the National Labor Belations Act.

There can be no argument that a particular restaurant

might well have come within that coverage in a given

case upon the authority of some of the National Labor

Belations Board decisions. However, this is quite a dif

ferent thing from saying there was a finding on the part

of Congress that the racial policies of restaurants serving

food which has moved in commerce has a burdensome com

mercial effect on interstate traffic.

The point here is that all of the testimony from Under

Secretary Roosevelt, Attorney General Kennedy and others

before the Senate Committee on Commerce, must be con

sidered in the contest of the proposed legislation before

the Committee. It is an unwarranted distortion of the

— 10 —

11 —

facts to say, as do appellants, that Congress had “ ample

basis upon which to find” that customer selection at res

taurants serving food which has crossed state lines places

a commercial burden upon interstate commerce. In truth,

there was no reason for an inquiry along this line and

the matter was not even before either congressional com

mittee.

2. No Such Finding Was in Fact Made.

Not only does the legislative history show that there

was no “ ample basis” for any such finding, but also that

no such finding was made.

Aside from the fact that no formal findings were in

cluded in H. R. 7152 as was the case in S, 1731,3 neither

the provisions of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

nor the legislative history lends any support to the con

tention of appellants that such a finding was made.

Whether Congress made any such finding is, funda

mentally, a matter of its intention. Appellees have at

all times contended that the statute on its face shows no

such finding and, indeed, persuades strongly to the con

trary. The definition of “ place of public accommodation”

under Section 201 (b) of the Act, uses the language “ if

its operations affect commerce”. These words are not

followed by any such language as “ as hereinafter further

defined” or any other language that indicates that the

words, “ affect commerce” should be given any meaning

other than a normal one. Later, in Section 201 (c), it

is provided, of course, that a restaurant’s operations do

affect commerce if a substantial portion of the food which

it serves has moved in commerce. It is difficult to see

why Congress would have employed the language and

arrangement of the statute if it had intended to base

3 The importance and, in some instances, the necessity for specific

findings, is discussed in a later portion of this brief.

— 12 —

coverage upon a finding of the type urged by appellants.

It would have been far more simple and more direct to

have included an additional line in Section 201 (b) (2)

and eliminate the necessity for Section 201 (c) (2) en

tirely. Certainly the statute on its face discloses no in

tention to make any such determination as is relied upon

by appellants.

In any event, the most that could be said to support

appellants is that the statute itself is not clear insofar as

Congress’ intention in this regard is concerned. Under

these circumstances, it is appropriate to inquire whether

the legislative history throws any light upon the point.

In determining the intention of Congress, this Court

has often recognized that remarks made by individual

congressmen or others, either in committee hearings or

on the floor of Congress, are not reliable guides as to

congressional intent. Nothing said before the Senate

Committee on Commerce could therefore throw any light

upon congressional intent with respect to the particular

point of whether Congress made any determination or

finding as is contended in appellant’s minor premise.

This is, of course, particularly true where the bill before

a committee was an entirely different one from that

finally enacted into law. Committee reports are frequently

looked to by the courts in determining what Congress

intends. Duplex Printing Press Co. v. Deering, 254 U. S.

443. As shown, there was no committee report on this

bill. Under these circumstances, it is appropriate to look

to the statements of the floor managers during congres

sional debate. U. S. v. St. Paul, M. & M. Ry., 247 U. S.

310. Senator Humphrey was the admitted commander

of the forces seeking passage of the bill. He was sup

ported by various other senators characterized as “cap

tains”, each assigned to a separate title of the bill. Senator

Magnuson was a captain to whom Title II was assigned.

Cong. Bee., 6308 (March 30, 1964).

As a part of his formal opening speech in favor of

H. R. 5172, Senator Humphrey offered in support of his

argument on constitutionality of Title II the legal opin

ion of some 22 eminent lawyers from whom he had re

quested an opinion. Since their opinion was relied upon

by Senator Humphrey and since the opinion necessarily

was based upon the writers’ conception of the applica

tion and effect of Title II, what was said in that opinion

may appropriately be examined in discerning a congres

sional intent with respect to the claimed finding. The

opinion was fully adopted and approved by Senator

Humphrey and the other principal managers of the bill

in the Senate.

The opinion dated March 30, 1964, addressed to Sena

tors Humphrey and Kuchel, is signed by Messrs. Harrison

Tweed and Bernard G. Segal and joined in by 20 other

eminent lawyers. It states:

With respect to title II, the congressional authority

for its enactment is expressly stated in the bill to

rest on the commerce clause of the Constitution and

on the 14th amendment. The reliance upon both

these powers to accomplish the stated purpose of title

II is sound. Discriminatory practices, though free

from any State compulsion, support, or encourage

ment, may so burden the channels of interstate com

merce as to justify legally, congressional regulation

under the commerce clause. On the other hand, con

duct having an insufficient bearing on interstate

commerce to warrant action under the commerce

clause may be regulated by the Congress where the

conduct is so attributable to the State as to come

within the concept of State action under the 14th

Amendment. Cong. Rec. 6832 (April 7, 1964). (Em

phasis supplied.)

It is submitted that the above language clearly con

templates that discriminatory practices “ may”, in an in-

— In

dividual case, sufficiently burden commerce to justify con

gressional regulation under the commerce clause but that

on the other hand, it “ may” not. Appellees have pre

viously taken the position that the inclusion of a 14th

Amendment aspect by use of the “ state action” test in and

of itself indicates that no overall congressional finding of

an aggregate commercial effect was made. The above

language confirms this. The ultimate question is what the

Congress intended with respect to any such finding. With

the explanation of the Act made by Senator Humphrey

and the other captains supporting him and with the above

legal opinion before them, it can hardly be stated that the

members of the Senate were even conscious of any finding

of the type imagined by appellants.

Senator Magnuson made a lengthy address on the floor

of the Senate specifically as to Title II. His role as self-

described was to expand inquiry as to the constitutionality,

wisdom, intent and effect of Title II. Cong. Rec. 7169

(April 9, 1964). One of the reasons for doing this, he said,

was to build a legislative history to aid the courts, ibid. At

the beginning of his remarks, he informed the Senate that

the provisions of Title II in H. R. 7152 were “ very sub

stantially like that” considered by the Committee on Com

merce, ibid. So saying, he announced that he would ‘ ‘ draw

upon the facts, convictions and ideas developed in the

course of those hearings in discussing the need for such

legislation, the power of Congress to act in this field, and

the intended application of the terms of this bill.” Ibid.

Thus, he started by equating the “ intended application”

of H. R. 1752 to the Senate bill which, as we have shown,

did not include a food test for restaurants. In his remarks,

he listed what he referred to as “ serious economic bur

dens, resulting from discriminatory practices in establish

ments dealing with the general public.” His enumeration

of “ burdens” was largely patterned on the proposed find-

■— 15 —

ings contained in S. 1731. Again, there was no mention of

a determination that discrimination in restaurants serving

food which has crossed state lines is a burden upon inter

state commerce. The burdens referred to by Senator Mag-

nuson might have supported the interstate traveler test

or the entire application of the statute to motels and hotels,

but it in no way even purported to apply to restaurants on

the basis of a food test, Cong. Rec. 7173 (April 9, 1964).

Finally, in his section-by-section analysis of the present

statute, Senator Magnuson, after noting that Section

201 (b) defines certain establishments as places of public

accommodations “ if their operations affect commerce,”

explained Section 201 (c) as follows:

Section 201 (c) provides the criteria- for determining

whether the operations of an establishment affect com

merce. Cong. Rec. 7175 (April 9, 1964). (Emphasis

supplied.)

Appellees have never contended that Congress did not

intend the serving of food which has crossed state lines

to be a “ criterion” for determining an effect on com

merce. Indeed, they have at all times objected to that

means on the grounds that the criterion thus legislated

was a conclusive presumption of the specific fact that

alone could give Congress power over the particular estab

lishment. Certainly Senator Magnuson’s remarks are not

consistent with a congressional declaration in the terms

of, or even resembling the finding claimed by appellants.

The legislative history of this statute is voluminous.

While we have not counted the pages of the Congressional

Record in 1963 and 1964 which are devoted to the civil

rights proposals that finally emerged as the present stat

ute, it is safe to say that they number in the thousands.

It is indeed strange that throughout those thousands of

pages there is not, so far as appellees can find, a single

word of testimony relating to the specific finding claimed

16

by appellants, i. e., that discrimination in restaurants

serving food which has crossed state lines has a substan

tial and close effect on interstate commerce. On the other

hand, the legislative history is replete with references to

National Labor Relations Board cases where it has been

determined on an ad hoc basis that a specific labor dis

pute would affect commerce. The legislative history in

this instance is not clear on many things, but to appellees

it seems abundantly clear that the members of Congress

intended that, insofar as a restaurant was concerned, there

must be an actual effect upon commerce determined by

the courts. If this be true, then the invalidity of the con

clusive presumption as to the food served renders Title II

unconstitutional as to appellees.

II. Prior Statutes Provide No Precedent for Title II.

The appellants’ brief relies heavily upon prior statutes

and prior decisions of the Court which involve the regula

tion of “ intrastate” or “ local” activities under the com

merce power. Their contention thus appears to be simply

that since it has been done before, it can be done here.

Our reply is twofold. First, merely because a particular

“ local” business may be reached by the federal commerce

power for one purpose plainly does not demonstrate that

even the same business may be reached for other purposes

and in regard to other activities. Secondly, an analysis of

past legislation and decisions involving the commerce

power demonstrates that the present statute, insofar as it

applies to appellees by virtue of the anterior movement of

food through commerce, departs markedly from any prior

statute sustained as an exercise of the commerce power.

It has been said that no commerce-power legislation reg

ulating activities “ local” in nature has been sustained by

this court unless those local activities are in commerce, are

found to affect commerce, or are so commingled with ac

tivities in interstate commerce that their regulation is

— 17 •—

necessary to achieve the regulation of those interstate. See

both the court’s opinion and the dissenting opinion in

United States v. Five Gambling Devices, 346 U. S. 411,

446-48, 460. So far as we are able to determine, this still

holds true. Title II of the present statute, insofar as per

tinent here, is incapable of being regarded as within the

scope of any of the other statutes or decisions. For the

purpose of so showing, and for the subsidiary purpose of

showing the existence of factual determinations of an

“ effect” on commerce by the regulated activity where such

effect was the source of the commerce power, we shall at

tempt to review those prior statutes and decisions.

1. Statutes Regulating Goods or Activities “ In Com

merce.”

Statutes of this sort include, of course, the regulation

of the actual movement of particular articles and persons

between the states as well as the instrumentalities by

which that movement is effectuated. And due to the local

orientation of our society until relatively recent years,

this was the chief area in which the commerce power

needed to be exercised. This, of course, is the most ele

mental use of the commerce power, for it comes within

the express terms of the constitutional grant. And since

it does, there is no need of a finding of the existence of an

effect on commerce or other auxiliary source of power.

(a) Statutes Regulating the Movement of Goods in

Commerce. Statutes of this character regulate the actual

movement of articles and persons across state lines (in

cluding whether they may be moved at all and, corol-

larially, the conditions upon which they may be moved).

In the main, such regulations are directed at specific

articles or specific practices in respect to articles (or

persons) which Congress deems deleterious in and of

themselves. Just as the states for similar reasons may

outlaw them locally, so can Congress deny them the use

18 —

of the channels of interstate commerce through its “ power

to keep the channels of such commerce free from the

transportation of illicit or harmful articles.” McDermott

v. Wisconsin, 228 U. S. 115, 128, (with regard to the Food

& Drug Act of 1906, 34 Stat. 768). Such statutes there

fore purport to regulate personal conduct only insofar

as the conduct relates specifically to an article which

moves or is intended for movement in commerce. Their

application is expressly limited accordingly. Thus, the

act regulating traffic in lottery tickets requires that they

be “ carried in interstate or foreign commerce” (18

U. S. 0., §1301); the Mann Act applies only to one who

“ transports in interstate . . . commerce . . . any woman”

or who “ obtains any ticket” for such transportation (18

U. S. C., §2421); stolen property must be transported in

or be a part of interstate commerce (18 U. S. C., §§2312-

2317); the Gambling Devices Act. requires transportation

of the device “ to any place in a state . . . from any

place outside of such state” (15 U. S. C., §1172); the

Kidnapping Act requires transportation of the person “ in

interstate commerce” (18 U. S. 0., §1201); the Fur Prod

ucts Labeling Act and the Textile Fiber Products Act

apply only to such products introduced or manufactured

for introduction into or sold in commerce between states

(15 IT. S. C., § 69 ; 15 U. S. 0., § 70); the Fair Labor Stand

ards Act applies only to an employee “ who is engaged

in commerce or in the production of goods for commerce”

(29 U. S. C., §§206, 207); the Federal Food, Drug and

Cosmetic Act applies only to such articles as are intro

duced or received in interstate commerce (21 U. S. C.,

§331); and the Ashurst-Summers Act (49 Stat. 494) ap

plied only to prison-made goods to be shipped or trans

ported in interstate . . . commerce,” see Kentucky Whip

& Collar Co. v. Illinois Cent, R. R,, 299 U. S. 334.

True, some of these statutes and others like them reach

“ local” conduct at either extremity of the injurious ar

ticle’s interstate journey. Thus, the Mann Act proscribes

19 —

the purchase of tickets for the prohibited transportation;

the Fur Products Labeling1 Act reaches the manufacture

and sale of the article which will be or has been shipped

interstate (15 U. S. C., § 692); the Food, Drug and Cos

metic Act reaches acts resulting in misbranding of the

articles done subsequent to the interstate movement and

before their sale to the ultimate consumer (21 U. S. C.,

§ 331 (k)); and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 regu

lates the wages and hours of employees engaged in the

manufacture of articles destined for shipment in inter

state commerce (29 U. S. C., §§ 206, 207). But in all such,

cases the regulated activity must be directly related to

the articles which are intended for or have moved in

interstate commerce. Congress having deemed the article

or its movement injurious it can, by virtue of its power

to exclude it altogether, restrict its movement except on

prescribed conditions. The power is over the particular

article, not the “ local” activity itself. Thus, it was said

of the convict-goods act, “ as the Congress could prohibit

the interstate transportation of convict-made goods . . .

the Congress could require packages containing convict-

made goods to be labeled . . . ”4; of the Fair Labor

Standards Act, “ The obvious purpose of the act was not

only to prevent the interstate transportation of the pro

scribed product, but to stop the initial step toward trans

portation, production with the purpose of so transporting

i t” 5; of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, “ Congress

may determine . . . the means necessary to make its

purpose effectual in preventing the shipment in interstate

commerce of articles of a harmful character, and to this

end may provide the means of inspection, examination,

and seizure.” 6

4 Kentucky Whip & Collar Co. v. Illinois Cent. R. R., 299 U. S.

334, 352-53. '

5 United States v. Darby, 312 U. S. 110, 117 (emphasis added),

and see Roland Elec. Co. v. Walling, 326 U. S. 657, 669.

6 McDermott v. Wisconsin, 228 U. S. 115, 135. And see

United States v. Sullivan, 332 U. S. 689, 696.

— 20 —

Contrastingly, Congress has not in Title II sought to

restrict the interstate movement of food; it did not and

could not regard food or its movement injurious; and the

proscribed “ local” activities have no connection, either

logically or on the face of the statute, with the article

which has moved in commerce.

(b) Statutes Regulating Instrumentalities of Commerce.

The other principal area of federal commerce clause regu

lation of acts shown to be in commerce is, that over in

strumentalities of interstate commerce. Like those regu

lating specific articles or their movement, these statutes

in the main are by their terms applicable only to instru

mentalities actually engaged in interstate commerce. Thus,

the Interstate Commerce Act is limited to “ common car

riers engaged in the transportation . . . [of commodities

or persons] from one state . . . to any other state,” (49

U. S. C., § 1); the Railway Labor Act is limited to a

“ carrier” which is “ subject to the Interstate Commerce

Act,” (45 U. S. C., §157, First); the Hours of Service

Act of 1907 regulates “ common carriers, their officers,

agents and employees, engaged in the transportation of

passengers or property . . . from one state . . . to any

other state,” (45 U. S. C., §§61-64); the act regulating-

bills of lading applies to bills of lading “ issued . . . for

the transportation of goods . . . from a place in one

state to a place in another state” (49 U. S. C., § 81); and

the Employers’ Liability Act of 1908 applies only to a

“ common carrier by railroad while engaging in commerce

between any of the several states,” and to injury to an

employee “ while he is employed by such carrier in such

commerce” (45 U. S. C., § 51).

The primary design and purpose of the above statutes

and others like them thus is to embrace chiefly articles

or activities in interstate commerce. Insofar as pertinent

here, Title II in design and purpose embraces purely local

activities only.

— 21 —

2. Statutes Extending Interstate Regulation to Com

mingled Intrastate Activities.

When Congress has undertaken to regulate predom

inantly interstate traffic and activities, as in statutes of

the above sort, it often has been necessary to extend the

reach of a particular regulation to include also “intra

state” activities or commodities. This has been done oidy

where the “local” activities are so intermingled with the

interstate that separation is impractical or impossible, and

their regulation therefore, is necessary to make the inter

state regulation effective. Moreover, in many such in

stances the interrelationship, either physically or eco

nomically, between the “intrastate” and the “interstate”

has been so close that practically and rationally both are

actually “in commerce,” and the decisions have so con

sidered them. This essentially has been the basis for the

extension of interstate regulation to otherwise “local”

activities in three principal types of regulatory statutes:

(1) those regulating instrumentalities of interstate com

merce; (2) those establishing economic regulation of

particular commodities produced for and sold in interstate

commerce; and (3) those prohibiting or regulating inter

state traffic of particular articles having dangerous or

otherwise deleterious propensities. Some examples, not

intended to be exhaustive, of statutes having “local” ap

plication in this context are set out below.

(a) Statutes Regulating “ Local” Activities in Associa

tion With Control of Interstate Instrumentalities. A rail

road or other instrumentality of commerce which is en

gaged in both interstate and intrastate commerce has been

subjected to federal regulation in respect to “ intrastate”

matters when they cannot practically be separated from

interstate activities for purposes of regulation. This was

the basis for applying the Safety Appliance Act, 45

U. S. C., §§ 1-16, to trains moving intrastate over the line

— 22 —

of an interstate carrier, in Southern Ey. v. United States,

222 U. S. 20; the Hours of Service Act, 45 U. S. C., §61,

to employees whose duties included both dealing with

trains moving in interstate and those moving in intra

state commerce, in Baltimore & 0. R. R. v. 1, 0. C., 221

U. S. 612; the Railway Labor Act, 45 U. S. C., §§151

et seq., to an interstate carrier’s “ back shop” employees

wmrking on equipment used in the carrier ’s transportation

service, 97% of which was interstate, in Virginian Ry. v.

System Federation No. 40, 300 U. S. 515, 554-57; the Em

ployers’ Liability Act of 1908, 45 IT. S. C., §51, to an

injury to the interstate employee of an interstate carrier

although the injury is caused by an intrastate employee,

in Second Employers’ Liability Cases, 223 IT. S. 48. The

same consideration was paramount in applying the Inter

state Commerce Act, 49 U. S. C., § 1 et seq., in Shreveport

Rate Case, 234 U. S. 342, 353, to the intrastate rates of an

interstate carrier which discriminated against the car

rier’s interstate traffic and consequently injuriously af

fected interstate commerce, since federal regulation can

be employed to “ prevent the common instrumentalities of

interstate and intrastate commercial intercourse from

being used in their intrastate operation to the injury of

interstate commerce.” In that case, the adverse effect

upon commerce was found judicially. Id., 234 IT. S, at

346. Thus, in each of these statutes “ intrastate” activ

ities were reached only when the carrier was engaged in

interstate commerce and when the intrastate activities

were inextricably bound to those obviously interstate.

(b) Statutes in Which “Local” Activities Are Reached

in Association With Economic Regulation of Interstate

Commodities. Statutes of this sort regulate specific com

modities, or their sale and movement, in interstate com

merce. Therefore, the principal thrust in each is the con

trol of activities purely interstate, and the statutory

language is drawn accordingly to reach primarily those

— 23 —

transactions which are in commerce. Thus, they basically

are economic regulations of activities in interstate com

merce. In their application it is recognized that in order

to achieve the major objective of the statute—control of

the movement of the regulated commodity in interstate

commerce—it sometimes is necessary to extend the control

to goods which themselves do not actually move inter

state. In every instance, however, the extension of regu

lation to the “ local” activities is predicated upon the fact

that those activities are so interwoven either physically or

economically with the interstate flow that to treat them

separately would be impossible practically and would im

pair or destroy the effectiveness of the regulation of

interstate activities. Indeed, in most cases where this has

been done the “ local” activity as a practical matter was

but a part of the interstate flow of the regulated com

modity. In each instance control of “ intrastate” matters

was merely a necessary incident of effective control over

interstate elements to which the statute was primarily

directed.

Statutes and decisions in which “ intrastate” affairs

have been subjected to regulation on this basis include the

Grain Futures Act of 1922, 42 Stat. 998, Board of Trade v.

Olsen, 262 U. S. 1; the Agricultural Marketing Agreement

Act of 1937, 7 U. S. C., § 608c, United States v. Wright-

wood Dairy Co., 315 U. S. 110; the Tobacco Inspection Act,

7 IT. S. CL, § 511a; Currin v. Wallace, 306 IT. S. 1; the Agri

cultural Adjustment Act of 1938, 7 U. S. C., §■§ 1281 et seq.,

Mulford v. Smith, 307 IT. S. 38, Wickard v. Filburn, 307

IT. S. I l l ; and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, 29

IT. S. C., §§ 201 et seq., United States v. Darby, 312 IT. S.

100.

The Grain Futures Act of 1922 regulated transactions

in grain futures at the Chicago Board of Trade, the in

termediary through which grain moving on through bills

of lading from other states through Chicago to destina

— 24 —

tions outside of Illinois was sold; thus, the statute applied

only to transactions in commodities in actual interstate

transit. Not only were the regulated activities “ such an

incident of that [interstate] commerce, and so intermingled

with it,” Board of Trade v. Olsen, 262 U. S. 36, but in

deed, like the activities regulated in the Stockyards &

Packers Act of 1921, and Stafford v. Wallace, 258 IT. S.

495, they “ cannot he separated from the [interstate] move

ment to which they contribute, and necessarily take on

its character.” Id., 262 U. S. at 35. And, although the

regulated activities thus were “ in” commerce, quite de

tailed statutory findings of their effect upon the interstate

movement of the commodity nevertheless were made byi

Congress and relied upon by the court. Id., 262 U. S.

at 4-5, 10-15, 37.

Similarly, the Tobacco Inspection Act of 1935, which

likewise was directed at a single, predominantly inter

state commodity in providing for inspection and grading

of leaf tobacco at auction warehouses, was chiefly the

regulation of “ sales in interstate or foreign commerce . . .

subject to congressional regulation.” Currin v. Wallace,

306 IT. S. at 10. Consequently, the basis for extending

the regulation in respect to some intrastate sales was

simply because “ [t]he fact that intrastate and interstate

sales are commingled on the tobacco market does not frus

trate or restrict the congressional power to protect and

control what is committed to its own care,” citing Shreve

port Rate Case, supra. Id., 306 IT. S. at 11.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, and Mulford

v. Smith, 307 IT. S. 38, presented the same situation, where

the dominant aim and impact of the economically directed

legislation was in respect to commodities moving in inter

state commerce—which “ constitutes interstate commerce” ,

Id., 307 IT. S. at 48—and locally destined tobacco was

subjected to regulation only insofar as it was so inter

— 25

mingled physically with that sold interstate that “ [reg u

lation, to he effective, must, and therefore may constitution

ally, apply to all sales.” Id., 307 U. S. at 47. Similarly,

in Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U. S. I l l , the local disposition

of wheat was so commingled economically with the inter

state movement of the commodity that its regulation too

was necessary to effectuate the major economic purpose of

control over the interstate movement.7 The Agricultural

Marketing Agreement Act of 1937, 7 IT. S. C. § 608c, which

was directed at regulation of the price of milk moving-

in interstate commerce, could regulate also the price of

intrastate milk found to directly affect interstate commerce

in milk since the “ national power to regulate the price

of milk moving interstate . . . extends to such control

over intrastate transaction as is necessary and appropriate

to make the regulation of the interstate commerce effec

tive.” United States v. Wrightwood Dairy Co., 315 U. S.

110, 121. And the Fair Labor Standards Act may be

applied to employees engaged in producing both interstate

and intrastate goods. United States v. Darby, 312 IT. S.

100, 118.8 For the same reason, federal control of interstate

sales of colored oleomargarine was extended by amendment

in 1950 (64 Stat. 20, 21 U. S. C., §347) to intrastate sales

precisely because “ [t]he regulation of the whole is neces

sary in order to provide effective regulation of that part

which originates from outside the state of consumption. ” 9

7 “ [A] factor of such volume and variability as home-consumed

wheat would have a substantial influence on price and market con

ditions . . . [and] if wholly outside the scheme of regulation would

have a substantial effect in defeating and obstructing its purpose to

stimulate trade therein at increased prices.” Wickard v. Filburn

317 U. S. at 138, 139.

8 “ f l ] t would be practically impossible, without disrupting manu

facturing businesses, to restrict the prohibited kind of production

to the particular pieces of lumber, cloth, furniture or the like which

later move in interstate rather than intrastate commerce”. United

States v. Darby, 312 U. S. 100, 118.

9 Senate Report No. 308, 81st Cong., 2nd Sess.; 1950 U. S.

Code, Cong. News, at 1973.

— 26 —

Since in each, of the above statutes the subject of the

regulation was predominantly activities and commodities

actually in interstate commerce, a legislative finding of

its effect on commerce would seem unnecessary. Yet each

contains such a statutory finding.10 And in some, as the

milk price control statute involved in United States v.

Wrighlwood Dairy Go., 315 U. S. 110, it was required addi

tionally that the effect be determined in administrative

proceedings subject to judicial review. Id., 315 IT. S. at 116.

With respect to the Fair Labor Standards Act in its

application to employees not “ engaged” in but producing

goods for commerce, it has been already noted that (1)

it was an exercise of the power to prevent the introduction

of the goods into interstate commerce and applied only to

activities directly connected with the preparation of those

goods for commerce, and (2) it applied to “ local” activi

ties only if there is a physical mingling of work on inter

state and intrastate articles. Unlike Title II, which like

anti-trust and labor legislation is directed at the activities

themselves which might affect the flow of commerce gen

erally, the Fair Labor Standards Act points to the goods

themselves. There, the commerce power was invoked on

and derived from that basis. Accordingly, the volume of

interstate movement and the effect on commerce in general

is not important; an employee might be covered if one or

two per cent of the articles he has worked on move inter

state. Pointing up this distinction further is the fact that

the Fair Labor Standards Act is based upon the future

movement of the particular article worked on; conse

quently, an employee can be covered one week and not the

next.

10 Tobacco Inspection Act, 7 U. S. C., § 511a; Agricultural

Adjustment Act, 7 U. S. C., § 1311, 7 U. S. C., § 1331; Agricultural

Marketing Agreement Act, 7 U. S. C., § 601; Fair Labor Stand

ards Act, 29 U. S. C., § 202; colored oleomargarine act, 21 U. S. C.,

§ 347a.

— 27 —

(c) Statutes in Which Control of Local Activities Is

Necessary to the Effective Control of the Interstate Move

ment of Harmful Articles. The other area in which “ local”

activities have been subjected to regulation is in statutes

in which Congress has undertaken the control or prohibi

tion of movement in interstate commerce of particular ar

ticles of injurious character and it has been necessary to

extend the control to local activities connected with that

particular article’s movement or use in order to make the

interstate control effective. Examples of this type of

“ local” regulation are the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act,

21 U. S. C., § 331 (k), U. S. v. Sullivan, 332 U. S. 689, and

the regulation of interstate bills of lading, 49 U. S. C., § 121,

United States v. Ferger, 250 U. S. 205. See also the dis

senting opinion of Mr. Justice Clark in United States v.

Five Gambling Devices, 346 U. S. 441, 460-463, regarding

the power to require manufacturers of gambling devices

to report both interstate and intrastate sales in order to

effectively control those made interstate.

Thus, in United States v. Ferger, supra, the power to

prohibit fictitious or forged bills of lading under which

no goods actually moved interstate was sustained because

it was necessary to the effective regulation of interstate

bills of lading and therefore in aid of Congress’ primary

power over an instrumentality of commerce.

In United States v. Sullivan, supra, it was held that

Congress’ power to regulate for the ultimate consumer’s

protection the labeling of drugs moving across state lines

could be applied to acts resulting in their mislabeling

done while the drugs were held for sale to the public by

a retail druggist who had purchased them from the in

terstate consignee. Under that statute, the Food, Drug

and Cosmetic Act, 21 U. S. C. § 331, the potentially in

jurious character of the article itself was the subject of

the regulation. Consequently, the effectiveness of Con

gress’ obvious power over its interstate movement would

have been entirely thwarted if the control over its label

ing had not been extended to the ultimate purchaser. The

fact of its movement to the retail druggist was not the

source of any congressional power except in respect to the

labeling of that particular article.11 Those statutes and

decisions therefore afford no analogy to what Title II

attempts to do. Thus, an application of the food-test

concept of commerce power to the facts in the Sullivan

case would achieve the remarkable result that Mr. Sulli

van’s drug store, because of his purchase of several bottles

of sulfathiazole which previously had moved in commerce,

could be regulated in any manner whatever irrespective

of a lack of connection with the injurious quality of the

drug. Congress could prescribe the seating capacity of

his establishment, the magazines he could sell, the min

imum age of customers he could serve. And since the

government’s position is that mere receipt at some point

after movement in commerce in itself was the source of

power in Sullivan, the power to regulate in general the

activities of the ultimate consumer would be established

as well. It may be said that such regulation might not

be reasonable, but appellants have urged Sullivan and

Mandel as authority for the existence of Congress’ power

to regulate, not for the reasonableness of its exercise.

Similarly, in oral argument, the Solicitor General, in

response to a question by the Court, agreed substantially

that Congress could make it a federal offense to hit one’s

wife with a baseball bat because the bat had moved in

commerce. The government necessarily assumed that posi

tion because under Title I I ’s food-movement test the

movement of food is tied not to the proscribed activity

but to the operation generally of restaurants, and even 11

11 See also Federal Trade Commission v. Mandel Bros., Inc., 359

U. S. 385, 391, which on the same grounds held the requirements

of the Fur Products Labeling Act, 15 U. S. C., § 69, could be ap

plied to fur in the hands of a retailer after interstate shipment.

29

the operations of a restaurant might or might not in a

given case actually affect commerce. To bring that illus

tration within the context of the Sullivan decision, as

sume Congress finds that narrow-handled baseball bats

are injurious to the public and, therefore, prescribes a

minimum diameter for bats moving in commerce. To

effectuate this law Congress could prohibit a person from

whittling the handle of a bat which had moved in com

merce. That would be the Sullivan case. But could Con

gress also prohibit this person from hitting his wife with

the bat? Or, more in accord with the food-movement test

of Title II, could the government regulate the recipient

of the bat in conduct which intrinsically is unconnected

with the bat? This underscores the weakness of the ap

pellants’ reliance upon dissimilar prior statutes and deci

sions in which “ local” activities have been reached under

the commerce power; for, the fact that they have been

reached as to some activities plainly does not establish

that they may be similarly reached as to others.

More generally, Title II, insofar as it applies to appel

lees, is unlike any of the statutes in which “ intrastate”

activities have been reached because they are commingled

with those interstate activities or movement to which

the regulation is principally directed. Other than those

regulating instrumentalities engaged in commerce, all of

those statutes significantly were regulations of the inter

state movement of a particular commodity or of particu

lar goods. The articles or commodities themselves were

the subject of regulation. Only those local activities

which were intrinsically a part of the interstate move

ment of the commodity or articles were regulated—not

activities which only affected the interstate flow of goods

in general. Local activities thus were reached only in

association with the broader scheme to regulate activities

actually in commerce, and then only when the control

of the interstate elements would be defeated without

— 30 —

regulation of the local. In each of the statutes establish

ing broad economic regulation of a commodity or articles,

Congress made specific legislative findings of the impact

of the regulated activities upon the interstate movement

of the commodity; and where purely intrastate commodi

ties were expressly made subject to regulation, as was

local milk in the Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act

and United States v. Wrightwood Dairy Go., 315 U. S.

110, provision has been made also for determination in

individual cases of an effect on the interstate movement

of that commodity. Title II, on the other hand, regulates

only local activities which have no intrinsic connection

with interstate commerce other than their possible effect

upon the general flow of goods. The Act is not directed

predominately at interstate activities of which the local

activity is but an incidental aspect; the regulation of the

local activity is the sole object of the statute. The Act

is not an economic regulation of a commodity or the

regulation of deleterious articles, but a regulation of ac

tivities in and of themselves. Consequently, the only

statutes and decisions which bear any similarity to the

Act are those such as the Sherman Act and the National

Labor Relations Act which also reach isolated intrastate

activities but only upon a determination of their effect

upon the general flow of commerce.

3. Statutes Regulating Local Activities When Found on an

Ad Hoc Basis to Affect Commerce.

Although there are other statutes12 in which the power

to regulate local activities is acquired on the basis of an

12 For example, the Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act. 21

U. S. C., § 608C; United States v. Wrightwood Dairy Co., 315 U. S.

110; and the Interstate Commerce Act, 49 U. S. C., § 13 (4) ; North

Carolina v. United States, 325 U. S. 507, 511; King v. United

States, 344 U. S. 254, 267-76; Shreveport Rate Case, 234 U. S.

342, 357-59, in each of which an administrative finding of an effect

on commerce, subject to judicial review, is contemplated.

— 31 —

ad hoc finding of an effect on commerce the primary

ones are the National Labor Relations Act, 29 U. S. C.,

§ 151 et seq., and the anti-trust statutes. In these stat

utes, as in the pertinent part of Title II, the object and

impact of the regulation is in respect to activities which

might have no connection with interstate commerce other

than an effect upon its general flow. Consequently, the

power to regulate such activities always has been made

dependent upon a determination that the particular ac

tivity involved in a particular case will have an effect

on commerce.

In appellees’ initial brief, particularly at pages 14

through 17, the requirement and practice under the Na

tional Labor Relations Act of a case-by-case determina

tion of the effect of a labor dispute or other activity

upon the flow of commerce is discussed. It was noted

that the required effect must be prospective, evidence

of past interstate purchases being only the basis for an

inference that there will be like purchases in the future.

See, e. g., N. L. R. B. v. Denver Bldg, and Constr. Trades

Council, 341 U. S. 675, 683-84; J. L. Brandeis & Sons v.

N. L. R. B., 142 F. 2d 977, 980 (C. A. 8).

The same determination is a requisite of regulation of

“ local” conduct under the Sherman Act, 26 Stat. 209, as

amended, 15 U. S. C., § 1, et. seq. Thus, Section 1 of the

Sherman Act, 15 U. S. C., § 1, proscribes only combina

tions or conspiracies “ in restraint of trade or commerce

among the several states, ’ ’ and Section 2, 15 U. S. C., § 2,

similarly applies only to persons who monopolize “ trade

or commerce among the several states.” A section—one

case, United States v. Employing Plasterers Ass’n., 347

U. S. 186, illustrates how the existence of a “ restraint”

of commerce depends upon a factual inquiry of the effect

of an otherwise “ local” conspiracy upon interstate com

merce in precisely the manner provided in the Labor

— 32

Relations Act. Tlie government’s complaint in that case

alleged that a conspiracy constituting a restraint on 60

per cent of the plastering business in the Chicago area

adversely affected the otherwise continuing flow of plas

tering materials from out-of-state origins to Illinois job

sites. Regarding the averments as charging only a “ local

restraint” not reached by the act, the district court dis

missed the complaint. This Court reversed since the gov

ernment’s allegations of the effect on commerce should

be “ taken into account in deciding whether the govern

ment is entitled to have its case tried,” id., 347 U. S. at

188, and must necessarily be resolved by a factual de

termination. For, as Mr. Justice Black observed, id.,

347 U. S. at 189:

[I] t goes too far to say that the government could

not possibly produce enough evidence to show that

these local restraints caused unreasonable burdens on

the free and uninterrupted flow of plastering mate

rials into Illinois. That wholly local business re

straints can produce the effects condemned by the

Sherman Act is no longer open to question. [Empha

sis added.]

The government’s proof would of course be subject to

rebuttal by the defendants. In every case in which the

unlawful activity is local, a similar determination is re

quired. See, e.g., United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 332

U. S. 218; United States v. Women’s Sportswear Ass’n,

336 U. S. 460.

The reason for requiring such a case-by-case determina

tion is that therein lies the only source of the government’s

power over the activity. As was stated by Mr. Justice

Stone in Apex Hosiery Co. v. Leader, 310 U. S. 469, 485,

498:

[I]n the application of the Sherman Act . . . it is

the nature of the restraint and its effect on interstate

commerce and not the amount of the commerce

which are the tests of violation.

This court has since repeatedly recognized that the

restraints at which the Sherman law is aimed . . .

are only those which, for constitutional reasons, are

confined to transactions in or which affect interstate

commerce [Emphasis added].

It follows that where it is determined that the local

activity neither is in the course of nor has a demonstra

bly substantial effect upon trade or commerce between

the states, it is not subject to the statute. See, e. g., United

States v. Yellow Cab Co., 332 U. S. 218; Industrial Ass’n v.

United States, 268 U. S. 64. Of course, when the pro

scribed activity is actually conducted through the chan

nels of interstate and is therefore “ in” commerce, it is in

no sense a “ local” activity, and can accordingly be regu

lated. See, e. g., Moore v. Mead’s Fine Bread Co., 348 U. S.

115 (Robinson-Patman Act, 15 U. S. C., $ 13(a) and 13a);

Lorain Journal Co. v. United States, 342 IT. S. 143.

Quite apparently, in view of its use only of the word

“ affect” in connection with commerce, the food-movement

basis of power in Title II was patterned after these de

cisions under the Labor Relations Act, the Sherman Act,

and similar statutes. To do so was necessary, in fact,