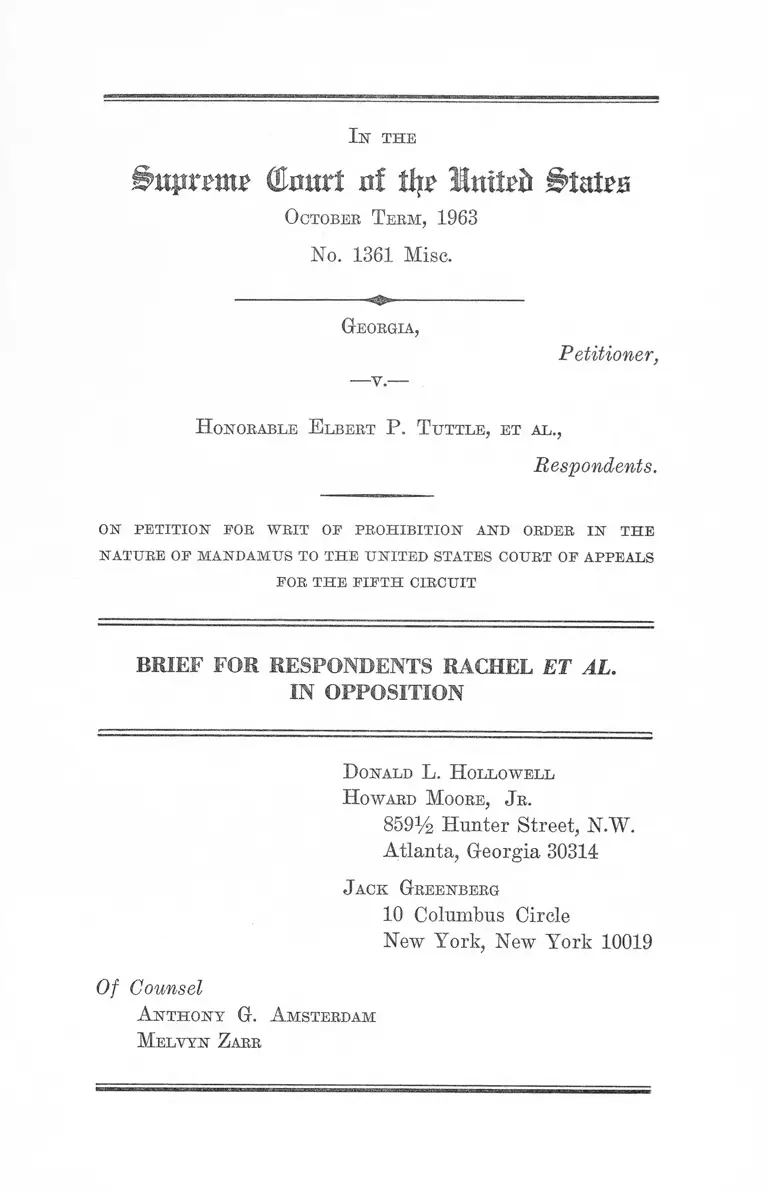

Georgia v. Rachel Brief for Respondents Rachel in Opposition

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Georgia v. Rachel Brief for Respondents Rachel in Opposition, 1965. 0349e22e-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e7e883f8-f31b-447d-9683-428527769999/georgia-v-rachel-brief-for-respondents-rachel-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n T H E

( ta r t nf tlj? Uniteii BtatzB

October Term, 1963

No. 1361 Misc.

Georgia,

—v.—

Petitioner,

H onorable E lbert P. T uttle, et at..,

Respondents.

ON PE T ITIO N EOR W RIT OP PRO H IB ITIO N AND ORDER IN T H E

NATURE OP MANDAMUS TO T H E U N ITE D STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR T H E F IF T H CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS RACHEL ET AL.

IN OPPOSITION

Donald L. H ollo well

H oward Moore, J r.

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Of Counsel

Anthony G. Amsterdam

Melyyn Zarr

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case .................................................. 1

Allegations in Response to the Petition _.................... 4

Statutes and Rules......................................................... 5

Statutory History ........................................... 9

A r g u m e n t

The Relief Sought by the State of Georgia Should

Not Be Granted If (I) the Court of Appeals Argu

ably Has Jurisdiction of the Case Pending Before It,

and (II) the Court of Appeals Could Arguably De

cide the Case in Favor of Respondents ................. 28

I. The Court of Appeals Arguably Has Jurisdic

tion of the Case Pending Before I t ..................... 31

II. The Court of Appeals Arguably Could Decide

the Case in Favor of Respondents..................... 51

Conclusion .................................................................... 59

A ppen dix :

Indictment of Rachel.............................................. 1

Petition for Removal................. 3

Order of Remand ............................ .......... ........... 8

Notice of Appeal ................. 13

Motion for Stay Pending Appeal ..... .................. 15

Motion to Dismiss Appeal ........................ 18

11

Opinion and Order of Conrt of Appeals .......... 22

Order of Superior Court of Fulton County.......... 24

Motion for Further Relief and Amendment There

to ...... .................................................................. 25

Order Enjoining Solicitor General ....................... 34

Opinion and Order Enjoining Sheriff ................. 37

Order of Superior Court of Fulton County of

April 1, 1964 ............... ............ ......................... 42

Order of Superior Court of Fulton County of

April 20, 1964 .................. ................................... 48

Table of Cases

Aetna Casualty & Surety Co. v. Flowers, 330 U. S. 464

(1947) ......................... ............... ................................ 35

Arceneaux v. Louisiana, 84 S. Ct. 777 (1964) .......... 31

Babbitt v. Clark, 103 U. S. 606 (1880) ........................ 33

Baines v. Danville, 321 F. 2d 643 (4th Cir. 1963) ...... 30

Baker v. Grice, 169 U. S. 284 (1898) ............................ 47

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58 (1963) ..29, 53

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 (1961) ................................................................. 5

Carroll v. United States, 354 U. S. 394 (1957) ........ 37

Cleary v. Bolger, 371 U. S. 392 (1963) ......................... 48

Cole v. Garland, 107 Fed. 759 (7th Cir. 1901), writ of

error dism’d, 183 U. S. 693 (1901) ................. 42,43,44

Colorado v. Symes, 286 U. S. 510 (1932) .................... 28

Commissioner v. Estate of Church, 335 U. S. 632

(1949) ......................... ............................................... 52

Congress of Racial Equality v. City of Clinton, Louisi

ana (Fifth Circuit, appeal pending) ........................ 3

Coppedge v. United States, 369 U. S. 438 (1962) ....34,45

PAGE

Deekert v. Independence Shares Corp., 311 U. S. 282

(1940) .................. .................. ..... ............. ................ 28

Dnrfee v. Duke, 375 U. S. 106 (1963) ............................ 40

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963) ...... 5, 29

Employers Reinsurance Corp. v. Bryant, 299 U. S.

374 (1937) ................................... ............... ................. 33

England v. Louisiana State Board of Medical Exam

iners, 375 U. S. 411 (1964) ____ _______ ___ _____ 56

Ex parte Bain, 121 U. S. 1 (1887) .... 46

Ex parte Newman, 14 Wall. 152 (1871) __ 33

Ex parte Royall, 117 U. S. 241 (1886) ........................ 47

Ex parte Siebold, 100 U. S. 371 (1879) ..... ............... 46

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391 (1963) _______11, 40, 46, 48, 49

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 (1961) ................. 5,29

Gay y. Ruff, 292 U. S. 25 (1934) .....................33,35,42,43

German Nat’l Bank v. Speckert, 181 U. S. 405 (1901) .. 43

Girouard v. United States, 328 U. S. 61 (1946) ....... 52

Heflin v. United States, 358 U. S. 415 (1959) ............ 34

Henry v. Rock Hill, 84 S. Ct. 1042 (1964) ........... 29

Hoadley v. San Francisco, 94 IT. S. 4 (1876) ......... 33

In re Hohorst, 150 U. S. 653 (1893) _______ 45

In re Loney, 134 U. S. 372 (1890) .................... 49

In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1 (1890) .... 49

In re Pennsylvania Co., 137 U. S. 451 (1890) ...........34,37

In re Snow, 120 U. S. 274 (1887) _____ 46

Insurance Co. v. Comstock, 16 Wall. 258 (1872) .......... 33

Jones v. Cunningham, 371 U. S. 236 (1963) ................. 45

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906) .............. 51,52,53

Labuy v. Howes Leather Co., 352 U. S. 249 (1957) ..32, 33,45

Local No. 438 v. Curry, 371 U. S. 542 (1963) ..... ........... 52

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 (1963) ...... ...........5, 52

I l l

PAGE

IV

McClellan v. Garland, 217 U. S. 268 (1910) .............. 33

McLaughlin Bros. v. Hallowell, 228 U. S. 278 (1913) .... 44

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 IT. S. 501 (1946) .....................5, 53

Maryland v. Soper, 270 IT. S. 9 (1926) ............ .......... 28, 29

Metropolitan Casualty Ins. Co. v. Stevens, 312 IT. S.

563 (1941) .......................... ...... ............................... .17,44

Missouri Pacific By. Co. v. Fitzgerald, 160 IT. S. 556

(1896) .......................................................................33, 39

Mitchell v. United States, 368 U. S. 439 (1962).............. 34

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961) ........................ 52, 57

Morey v. Lockhart, 123 U. S. 56 (1887) ......................... 39

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ...........29, 53, 54

Nielsen, Petitioner, 131 IT. S. 176 (1889) ..................... 46

New York v. Eno, 155 U. S. 89 (1894) ................. ....... 47

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 84 S. Ct. 710 (1964) 53

Ohio v. Thomas, 173 U. S. 276 (1899) ......................... 49

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 (1963) ................. 5

Platt v. Minnesota Mining & Mfg. Co., 84 S. Ct. 769

(1964) ............................................... 33

Prendergast v. New York Telephone Co., 262 U. S. 43

(1923) .......................................... 28,30

Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U. S. 158 (1944) .............. 53

Bailroad Co. v. Wiswall, 23 Wall. 507 (1874) ............. 33

Beece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 85 (1955) ............. 54

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 (1948) ............. 53

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ____________ 5

Snypp v. Ohio, 70 F. 2d 535 (6th Cir. 1934) ..............38, 42

Speiser v. Bandall, 357 U. S. 513.................................. 55

Stack v. Boyle, 342 U. S. 1 (1951) ................................ 46

Stefanelli v. Minard, 342 U. S. 117 (1951) ..................... 48

PAGE

V

Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S. 257 (1879) ........ ............ 31

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940) ..................... 5

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 (1963) ..................... 40

Turner v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., 106 IT. S. 552

(1882).................................... -.........-............................ 33

United States v. Borden Co., 308 U. S. 188 (1939) .... 42

United States v. Jackson, 302 U. S. 628 (1938) .......... 42

United States v. Morgan, 346 U. S. 502 (1954) .............. 34

United States v. Noce, 268 U. S. 613 (1925) ................. 42

United States v. Rice, 327 U. S. 742 (1946) ...... 33, 37, 39, 42

United States v. Sanges, 144 U. S. 310 (1892) .............. 36

United States v. Smith, 331 U. S. 469 (1947) .............. 33

United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U. S. 258

(1947) ......................................................................... 28

United States Alkali Export Assn. v. United States,

325 U. S. 196 (1945) .................................................. 42

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313 (1879) .....................54,55

Waley v. Johnston, 316 U. S. 101 (1942) ..................... 46

Waugaman v. United States (5th Cir. No. 21077), de

cided April 27, 1964 .................................................. 45

Wildenhus’s Case, 120 U. S. 1 (1887) ......................... — 49

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) ..................... 47

F ederal Statutes and R ules :

28 U. S. C. §1291 (1958) .................................. 5

28 U. S. C. §1443 (1958) ....................... 6

28 U. S. C. §1447(d) (1958) ..................................... 6

28 U. S. C. §1651 (1958) _____ 6

28 U. S. C. §2241 (1958) ...... 7

28 U. S. C. §2254 (1958) ........... .......................... 7

Fed. Rule Civ. Pro. 81(b) ........... ........................ 8

Fed. Rule Crim. Pro. 37 ....................................... 8

PAGE

S t a t e S t a t u t e :

Ga. Code Ann. §26-3005 (1963 Supp.) (Georgia

Laws, 1960, pp. 142-43) __ __________1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Other Authorities :

Bator, Finality in Criminal Law and Federal

Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners, 76 Harv.

L. Rev. 441 (1963) _____________________ _

Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 3d Sess. 538 (1/27/1863)

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 129 (1/5/1866),

184 (1/11/1866), 211 (1/12/1866) ................

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 475 (1/29/1866)

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1759 (4/4/86) ..

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 4150-51

(7/25/1866) ................................ ..... ...... ............ .

95 Cong. Rec. 5020 (81st Cong., 1st Sess. (4/26/

49)) ------ -------------------------------------------- -

95 Cong. Rec. 5827 (81st Cong., 1st Sess.

(5/6/49)) .................. ......27,

Desty, The Removal of Causes From State to

Federal Courts (3d ed. 1893) ...........................

Dillon, Removal of Causes From State Courts to

Federal Courts (5th ed. 1889) ______________

I l l Elliot’s Debates (1836) ...................................

I Farrand, Records of the Federal Convention

(1911) ......................... 9,

The Federalist, No. 80 (Hamilton) (Warner, Phil

adelphia ed. 1818) .... 9,

The Federalist, No. 81 (Hamilton) (Warner, Phil

adelphia ed. 1818) .................................. ............

Frankfurter & Landis, The Business of the Su

preme Court (1928) ..... .................................. .19,

', 8

37

53

57

57

57

48

27

35

38

38

10

53

10

9

37

Vll

PAGE

Hart & Wechsler, The Federal Courts and the

Federal System (1953) ______ ___________9,35

H. E. Eep. No. 352, 81st Cong., 1st Sess. (1949) .... 27

H. R. Eep. No. 1078, 49th Cong., 1st Sess. (1886) 37

McKitrick, Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction

(1960) ____________________ ______ ____ __ 48

1 Morison & Commager, Growth of the American

Republic (4th ed. 1950) ........................ .............. 11

Randall, The Civil War and Reconstruction (1937) 48

Speer, Removal of Causes From the State to Fed

eral Courts (1888) ................................. ........... . 38

Isr t h e

§>ttprm£ (Erntrl nf % Itttteft States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1963

No. 1361 Misc.

G e o r g ia ,

-v.-

Petitioner,

H o n o r a b l e E l b e r t P . T u t t l e , e t a l .,

Respondents.

o n p e t i t i o n e o r w r i t o p p r o h i b i t i o n a n d o r d e r i n t h e

NATURE OP MANDAMUS TO T H E U N ITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR T H E P IP T H CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS RACHEL ET AL.

IN OPPOSITION

Statement of the Case

Respondents1 Rachel et al. attempted, during May and

June of 1963, to obtain desegregated service at segregated

restaurants in Atlanta, Georgia (see verified petition for

removal, (|1) (App. pp. 3-6). When respondents refused to

leave these restaurants after having been requested to do

so, they were arrested and charged with violation of Ga.

Code Ann. §26-3005 (1963 Supp.) (Georgia Laws, 1960, pp.

142-43), p. 8, infra, which makes it a misdemeanor to re

fuse to leave the premises of another upon request.

1 Throughout this brief the term “respondents” refers to the

defendants in the criminal actions sought to be removed, who are

respondents in this Court by reason of the Court’s Rule 31(3).

The term “respondents” is not used to refer to the judges of the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

2

On August 2, 1963, indictments against respondents for

violations of section 26-3005 were returned by the grand

jury of Fulton County (see, e.g., App. pp. 1-2).

On February 17, 1964, respondents herein petitioned the

United States District Court for the Northern District of

Georgia, Atlanta Division, for removal of the prosecutions

from the Superior Court of Fulton County. Respondents

alleged in their verified petition that removal was neces

sary and proper under 28 U. S. C. §1443, because respon

dents could not enforce in the state court their rights under

the First Amendment and the Due Process and Equal Pro

tection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States. Moreover, respondents al

leged they were being prosecuted for acts done under color

of authority of the federal Constitution and laws and for

refusing to do acts inconsistent with the Constitution and

laws (App. pp. 6-7).

The following day, United States District Judge Boyd

Sloan remanded sua sponte, without hearing or argument,

construing section 1443 to be inapplicable “where a party is

deprived of any civil right by reason of discrimination or

illegal acts of individuals or judicial or administrative

officers” (App. p. 11).

Respondents herein filed a notice of appeal from Judge

Sloan’s order on March 5, 1964 (App. p. 13). On March

12, 1964, they filed in the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit a motion for a stay pending appeal, to which was

appended a copy of the petition for removal and the re

mand order. The motion recited that Judge Durwood T.

Pye of the Superior Court of Fulton County had ordered

defendants in companion cases to show cause wdiy their

bonds should not be increased and that respondents here

in stood threatened with the immediate prospect of their

bonds being increased by Judge Pye, who had already in

3

creased the bond of one accused misdemeanant from $500

to $7000. If respondents’ bonds were increased, many of

them would be required to remain in jail because of in

ability to make the increased bond. The motion further

recited that the criminal prosecutions prevented them from

exercising their rights under the federal Constitution and

laws, that if Judge Sloan had granted a hearing respon

dents herein would have shown facts sustaining federal re

moval jurisdiction, and that unless a stay were granted

the substantial issues raised by respondents would become

moot (App. pp. 15-17).

Also on March 12th, the State of Georgia moved to dis

miss the appeal and to deny the stay, arguing that the

Court of Appeals was without jurisdiction of the case

(App. pp. 18-21).

The same day, the Court of Appeals, on the authority

of Congress of Racial Equality v. City of Clinton, Louisiana

(appeal pending in the Fifth Circuit), ordered the remand

order of the district court stayed pending disposition of

the instant appeal or earlier order (App. pp. 22-23).

In the face of the order of the Court of Appeals retaining

federal jurisdiction over the cases, Judge Pye “declined to

surrender jurisdiction,” ordered the Solicitor General, At

lanta Judicial Circuit, to proceed with the prosecutions in

his court, and directed the sheriff of Fulton County to defy

the order of the United States District Court commanding

the sheriff to surrender Prathia Laura Ann Hall, a peti

tioner for removal in a companion case, to the United States

marshal (App. p. 24 (Verified motion, adopted as findings

of fact by Order, App. p. 35)). Respondents, together with

others charged with §26-3005 violations who had filed re

moval petitions, moved the district court to forestall fur

ther action by Judge Pye (App. pp. 25-32).

4

On March 21, 1964, District Judge Sloan enjoined the

Solicitor General from proceeding further in any of the

removed cases until further order (App. pp. 34-36), and on

March 25th, Judge Sloan enjoined the sheriff of Fulton

County or any other person acting under orders of Judge

Pye from taking the respondents herein and others similarly

situated into custody for purposes of these prosecutions

(App. pp. 37-41).

On April 1, 1964, Judge Pye ordered the Solicitor Gen

eral, Atlanta Judicial Circuit, to apply to this Court for

writs of mandamus and prohibition against the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit directing that Court to va

cate its stay order and to proceed no further with the

case (App. pp. 42-47).

On April 20, 1964, Judge Pye struck the instant prosecu

tions from his calendar “until the rule of law shall be re

stored within the territorial limits of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Judicial Circuit” (App.

pp. 48, 51).

Allegations in Response to the Petition

The State of Georgia notes in its petition (Petn., p. 16)

that respondents have not attacked the constitutionality of

Ga. Code Ann. §26-3005 (1963 Supp.), the criminal tres

pass statute under which the prosecutions sought to be

removed are maintained. Respondents made no such specific

challenge to the statute in their removal petition because

the unconstitutionality of the statute is principally a mat

ter for defense on the merits to prosecution of the removed

actions. Had the District Judge permitted hearing or argu

ment before remanding the cases, respondents would have

argued under the First and Fourteenth Amendment claims

of their removal petition (App. pp. 3, 6-7) that the federal

rights which they cannot enforce in the state courts (28

5

U. S. C. §1443(1) (1958)),2 and the rights which they were

exercising under color of federal authority in refusing to

leave the restaurants in obedience to orders which would

have compelled them to act inconsistently with federal law

(28 IT. S. C. §1443(2)), were, inter alia, their rights to

immunity from sanctions imposed for violation of an un

constitutional statute, §26-3005. For purposes of clarifica

tion of their argument in defense to Georgia’s original peti

tion in this Court, respondents therefore allege that Ga.

Code Arm. §26-3005 (1963 Supp.) is unconstitutional on its

face under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, cf.

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946) and Thornhill v.

Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940); Garner v. Louisiana, 368

U. S. 157, 185 (1961) (Mr. Justice Harlan, concurring),

and under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, cf. Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 U. S. 715, 726-730 (1961) (separate opinions of Justices

Stewart, Frankfurter and Harlan), and unconstitutional

as applied under the First and Fourteenth Amendments,

cf. Marsh v. Alabama, supra; Edwards v. South Carolina,

372 U. S. 229 (1963), and under the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, cf. Peterson v. Green

ville, 373 IT. S. 244 (1963); Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S.

267 (1963); Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948).

Statutes and R ules

28 IT. S. C. §1291 (1958):

§1291. Final decisions of district courts.

The courts of appeals shall have jurisdiction of ap

peals from all final decisions of the district courts of

the United States, . . .

2 These rights derive from the First Amendment and the Due

Process and Equal Protection clauses of the Fourteenth. They are

protected by Rev. Stat. §§1977-1981, 42 U. S. C. §§1981-1986

6

28 U. S. C. §1443 (1958):

§1443. Civil rights cases.

Any of the following civil actions or criminal prose

cutions, commenced in a State court may be removed

by the defendant to the district court of the United

States for the district and division embracing the place

wherein it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot en

force in the courts of such State a right under any

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States, or of all persons within the jurisdic

tion thereof;

(2) For any act under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights, or for refus

ing to do any act on the ground that it would be in

consistent with such law.

28 U. S. C. §1447(d) (1958):

§1447. Procedure after removal generally.

(d) An order remanding a case to the State court

from which it was removed is not reviewable on appeal

or otherwise. . . .

28 U. S. C. §1651 (1958):

§1651. Writs.

(a) The Supreme Court and all courts established

by Act of Congress may issue all writs necessary or

appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and

agreeable to the usages and principles of law.

(1958). Throughout this brief the terms “federal rights” or “con

stitutional rights” refer to these rights and invoke both consti

tutional and statutory protection.

7

28 U. S. C. §2241 (1958):

§2241. Power to grant writ.

(a) Writs of habeas corpus may be granted by the

Supreme Court, any justice thereof, the district courts

and any circuit judge within their respective jurisdic

tions. The order of a circuit judge shall be entered in

the records of the district court of the district wherein

the restraint complained of is had.

(b) The Supreme Court, any justice thereof, and any

circuit judge may decline to entertain an application

for a writ of habeas corpus and may transfer the ap

plication for hearing and determination to the district

court having jurisdiction to entertain it.

(c) The writ of habeas corpus shall not extend to

a xmisoner unless—

(3) He is in custody in violation of the Constitu

tion or laws or treaties of the United States; . . .

28 U. S. C. §2254 (1958):

§2254. State custody; remedies in State Courts.

An application for a writ of habeas corpus in behalf

of a person in custody pursuant to the judgment of a

State court shall not be granted unless it appears that

the applicant has exhausted the remedies available in

the courts of the State, or that there is either an ab

sence of available State corrective process or the exist

ence of circumstances rendering such process ineffec

tive to protect the rights of the prisoner.

An applicant shall not be deemed to have exhausted

the remedies available in the courts of the State, within

the meaning of this section, if he has the right under

the law of the State to raise, by any available pro

cedure, the question presented.

8

Fed. Rule Civ. Pro. 81 (b ):

(b) Scire Facias and Mandamus. The writs of scire

facias and mandamus are abolished. Relief heretofore

available by mandamus or scire facias may be obtained

by appropriate action or by appropriate motion under

the practice prescribed in these rules.

Fed. Rule Crim. Pro. 37:

Rule 37.

(a) Taking Appeal to a Court of Appeals.

(1) Notice of Appeal. An appeal permitted by law

from a district court to a court of appeals is taken by

filing with the clerk of the district court a notice of

appeal in duplicate. . . .

(2) Time for Taking Appeal. An appeal by a defen

dant may be taken within 10 days after entry of the

judgment or order appealed from. . . .

Ca. Code Ann. §26-3005 (1963 Supp.):

26-3005. Refusal to leave premises of another when

ordered to do so by owner or person in charge.—It

shall be unlawful for any person, who is on the prem

ises of another, to refuse and fail to leave said prem

ises when requested to do so by the owner or any

person in charge of said premises or the agent or em

ployee of such owner or such person in charge. Any

person violating the provisions of this section shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction thereof

shall be punished as for a misdemeanor. (Acts 1960,

p. 142.)

9

S ta tu to ry H is to ry

Progressively since the inception of the Government, fed

eral removal jurisdiction has been expanded by Congress3

to protect national interests in cases “in which the state

tribunals cannot be supposed to be impartial and un

biassed,” 4 for, as Hamilton wrote in The Federalist, “The

most discerning cannot foresee how far the prevalency of

a local spirit may be found to disqualify the local tribunals

for the jurisdiction of national causes. . . . ” 5 In the fed

eral convention Madison pointed out the need for such

protection, just before he successfully moved the Commit

tee of the Whole to authorize the national legislature to

create inferior federal courts:6

“Mr. [Madison] observed that unless inferior tri

bunals were dispersed throughout the Republic with

final jurisdiction in many cases, appeals would be multi

plied to a most oppressive degree; that besides, an

3 See H art & Wechsler, The F ederal Courts and the F ederal

System 1147-1150 (1953). Before 1887, the requisites for removal

jurisdiction were stated independently of those for original fed

eral jurisdiction; since 1887, the statutory scheme has been to

authorize removal generally of cases over which the lower federal

courts have original jurisdiction and, additionally, to allow removal

in special classes of cases particularly affecting the national inter

est: suits or prosecutions against federal officers, military per

sonnel, persons unable to enforce their equal civil rights in the

state courts, person acting under color of authority derived from

federal law providing for equal rights or refusing to act inconsis

tently with such law, the United States (in foreclosure actions),

etc. 28 U. S. C. §§1441-1444 (1958); see H art & Wechsler supra,

at 1019-1020.

4 The F ederalist, No. 80 (Hamilton) (Warner, Philadelphia ed.

1818), at 429.

5 Id., No. 81, at 439.

61 F arrand, Records of the F ederal Convention 125 (1911).

Mr. Wilson and Mr. Madison moved the matter in pursuance of

a suggestion of Mr. Dickinson.

10

appeal would not in many cases be a remedy. What

was to be done after improper Verdicts in State tri

bunals obtained under the biassed directions of a de

pendent Judge, or the local prejudices of an undirected

jury? To remand the cause for a new trial would an

swer no purpose. To order a new trial at the supreme

bar would oblige the parties to bring up their wit

nesses, tho’ ever so distant from the seat of the Court.

An effective Judiciary establishment commensurate to

the legislative authority, was essential. A Government

without a proper Executive & Judiciary would be the

mere trunk of a body without arms or legs to act or

move.” 7

The Judiciary Act of 1789 allowed removal in specified

classes of cases where it was particularly thought that local

prejudice would impair national concerns,8 and extensions

of the removal jurisdiction were employed in 1815 and 1833

to shield federal customs officials, respectively, against New

England’s resistance to the War of 1812 and South Caro

lina’s resistance to the tariff.'9 The 1815 act allowed re

71 id. 124.

8 The Act of September 24, 1789, ch. 20, §12, 1 Stat. 73, 79-80,

authorized removal in three classes of cases where more than $500

was in dispute: suits by a citizen of the forum state against an out-

stater ; suits between citizens of the same state in which the title

to land was disputed and the removing party set up an outstate

land grant against his opponent’s land grant from the forum state;

suits against an alien. The first two classes were specifically de

scribed by Hamilton as situations “in which the state tribunals

cannot be supposed to be impartial,” The F ederalist, No. 80

(Warner, Philadelphia ed. 1818), at 432; and Madison, speaking

of state courts in the Virginia convention, amply covered the

third: “We well know, sir, that foreigners cannot get justice done

them in these courts. . . . ” I l l E lliot’s Debates 583 (1836).

9 Act of February 4, 1815, ch. 31, §8, 3 Stat. 195, 198. Concern

ing Northern resistance to the War culminating in the Hartford

1 1

moval of “any suit or prosecution” (save prosecutions for

offenses involving corporal punishment) commenced in a

state court against federal officers or other persons acting

under color of the act or as customs officers, 3 Stat, 198;

the 1833 act allowed removal in any case where “suit or

prosecution” was commenced in a state court against any

federal officer or other person acting under color of the

revenue laws, or on account of any authority claimed under

the revenue laws, 4 Stat. 633.

Congress was thus acting within a tradition of enforcing

national policies against resistant localities by use of the

removal jurisdiction when, in 1863, it provided “That if

any suit or prosecution, civil or criminal, has been or shall

be commenced in any state court against any officer, civil

or military, or against any other person, for any arrest or

imprisonment made, or other trespasses or wrongs done

or committed, or any act omitted to be done, at any time

during the present rebellion, by virtue or under color of

any authority derived from or exercised by or under the

President of the United States, or any act of Congress,”

the defendant might remove the proceeding into a circuit

court of the United States. Act of March 3, 1863, eh. 81,

§5, 12 Stat. 755, 756. Certain procedural amendments to

the 1863 act were effected by the Act of May 11, 1866, eh. 80,

14 Stat. 46, which also provided in its fourth section “That

if the State court shall, notwithstanding the performance

Convention of 1814-1815, see 1 Morison & Commager, Growth

of the A merican Republic 426-429 (4th ed. 1950).

Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §3, 4 Stat. 632, 633. Concerning

South Carolina’s resistance to the successive tariffs, culminating

in the nullification ordinance, see 1 Morison & Commager, supra

475-485. The Force Act of March 2, 1833, responded to the South

ern threat not merely by extending the removal jurisdiction of the

federal courts, hut by establishing a new head of habeas corpus

jurisdiction. Section 7, 4 Stat. 632, 634. See Fay v. Noia, 372

U. S. 391, 401 n. 9 (1963).

12

of all tilings required for the removal of the case to the

circuit court . . ., proceed further in said cause or prose

cution [before receipt of a certificate from the circuit court

stating that the removal has not been perfected] . . ., then,

in that case, all such further proceedings shall be void and

of none effect. . . . ”

Earlier in the same 1866 session, Congress passed, over

the presidential veto, the first civil rights act, Act of April

9, 1866, ch. 31, 14 Stat. 27. The first and third sections of

the act, reproduced below, significantly expanded federal

removal jurisdiction within the traditions of the 1815, 1833

and 1863 enforcement legislation:

“Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Repre

sentatives of the United States of America in Congress

assembled, That all persons born in the United States

and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians

not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the

United States; and such citizens, of every race and

color, without regard to any previous condition of

slavery or involuntary servitude, except as a punish

ment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly

convicted, shall have the same right, in every State and

Territory in the United States, to make and enforce

contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to

inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and

personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all

laws and proceedings for the security of person and

property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall

be subject to like punishment, pains, and penalties, and

to none other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation,

or custom, to the contrary notwithstanding.

“Sec. 2. And be it further enacted, That any person

who, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regu

lation, or custom, shall subject, or cause to be subjected,

13

any inhabitant of any State or Territory to the depriva

tion of any right secured or protected by this act, or

to different punishment, pains, or penalties on account

of such person having at any time been held in a condi

tion of slavery or involuntary servitude, except as a

punishment for crime whereof the party shall have

been duly convicted, or by reason of his color or race,

than is prescribed for the punishment of white persons,

shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and, on con

viction, shall be punished by line not exceeding one

thousand dollars, or imprisonment not exceeding one

year, or both, in the discretion of the court.

“Sec. 3. And be it further enacted, That the district

courts of the United States, within their respective

districts, shall have, exclusively of the courts of the

several States, cognizance of all crimes and offences

committed against the provisions of this act, and also,

concurrently with the circuit courts of the United

States, of all causes, civil and criminal affecting per

sons who are denied or cannot enforce in the courts or

judicial tribunals of the State or locality where they

may be any of the rights secured to them by the first

section of this act; and if any suit or prosecution, civil

or criminal, has been or shall be commenced in any

State court, against any such person, for any cause

whatsoever, or against any officer, civil or military, or

other person, for any arrest or imprisonment, tres

passes, or wrongs done or committed by virtue or un

der color of authority derived from this act or the act

establishing a Bureau for the relief of Freedmen and

Refugees, and all acts amendatory thereof, or for re

fusing to do any act upon the ground that it would be

inconsistent with this act, such defendant shall have

the right to remove such cause for trial to the proper

district or circuit court in the manner prescribed by

14

the ‘Act relating to habeas corpus and regulating ju

dicial proceedings in certain cases/ approved March

three, eighteen hundred and sixty-three, and all acts

amendatory thereof. The jurisdiction in civil and crim

inal matters hereby conferred on the district and cir

cuit courts of the United States shall be exercised and

enforced in conformity with the laws of the United

States, so far as such laws are suitable to carry the

same into effect; but in all cases where such laws are

not adapted to the object, or are deficient in the pro

visions necessary to furnish suitable remedies and

punish offences against law, the common law, as modi

fied and changed by the constitution and statutes of

the State wherein the court having jurisdiction of the

cause, civil or criminal, is held, so far as the same is

not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws of the

United States, shall be extended to and govern said

courts in the trial and disposition of such cause, and,

if of a criminal nature, in the infliction of punishment

on the party found guilty.”

The 1866 statute was reenacted by reference in the civil

rights act of 1870,10 and, with stylistic changes, became

Kev. Stat. §641:

10 The Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §§16-18, 16

Stat. 140, 144:

“Sec. 16. And be it further enacted, That all persons with

in the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same

right in every State and Territory in the United States to

make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence,

and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings

for the security of person and property as is enjoyed by white

citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, pen

alties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and none

other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom to

the contrary notwithstanding. No tax or charge shall be im

posed or enforced by any State upon any person immigrating

thereto from a foreign country which is not equally imposed

and enforced upon every person immigrating to such State

15

“Sec. 641. When any civil suit or criminal prose

cution is commenced in any State court, for any cause

whatsoever, against any person who is denied or can

not enforce in the judicial tribunals of the State, or in

the part of the State where such suit or prosecution is

pending, any right secured to him by any law provid

ing for the equal civil rights of citizens of the United

States, or of all persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States, or against any officer, civil or military,

or other person, for any arrest or imprisonment or

other trespasses or wrongs, made or committed by

virtue of or under color of authority derived from any

law providing for equal rights as aforesaid, or for

refusing to do any act on the ground that it would be

inconsistent with such law, such suit or prosecution

may, upon the petition of such defendant, filed in said

State court, at any time before the trial or final hearing

of the cause, stating the facts and verified by oath, be

removed, for trial, into the next circuit court to be

from any other foreign country; and any law of any State in

conflict with this provision is hereby declared null and void.

“Sec. 17. And be it further enacted, That any person who,

under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or

custom, shall subject, or cause to be subjected, any inhabitant

of any State or Territory to the deprivation of any right

secured or protected by the last preceding section of this act,

or to different punishment, pains, or penalties on account of

such person being an alien, or by reason of his color or race,

than is prescribed for the punishment of citizens, shall be

deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and, on conviction, shall be

punished by fine not exceeding one thousand dollars, or im

prisonment not exceeding one year, or both, in the discretion of

the court.

“Sec. 18. And be it further enacted, That the act to pro

tect all persons in the United States in their civil rights, and

furnish the means of their vindication, passed April nine,

eighteen hundred and sixty-six, is hereby re-enacted; and sec

tions sixteen and seventeen hereof shall be enforced according

to the provisions of said act.”

16

held in the district where it is pending. Upon the filing

of such petition all further proceedings in the State

courts shall cease, and shall not be resumed except as

hereinafter provided.. . . ”

In 1911, in the course of abolishing the old Circuit Courts,

Congress technically repealed Eev. Stat. §6411:l but carried

its provisions forward without change (except that removal

jurisdiction was given the district courts in lieu of the cir

cuit courts) as §31 of the Judicial Code.11 12 Section 31

verbatim became 28 U. S. C. §74 (1940),13 and in 1948, with

11 Judicial Code of 1911, §297, 36 Stat. 1087, 1168.

12 Judicial Code of 1911, §31, 36 Stat. 1087, 1096:

“Sec. 31. When any civil suit or criminal prosecution is

commenced in any State court, for any cause whatsoever,

against any person who is denied or cannot enforce in the

judicial tribunals of the State, or in the part of the State where

such suit or prosecution is pending, any right secured to him

by any law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States, or of all persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States, or against any officer, civil or military, or

other person, for any arrest or imprisonment or other tres

passes or wrongs made or committed by virtue of or under

color of authority derived from any law providing for equal

rights as aforesaid, or for refusing to do any act on the ground

that it would be inconsistent with such law, such suit or prose

cution may, upon the petition of such defendant, filed in said

State court at any time before the trial or final hearing of

the cause, stating the facts and verified by oath, be removed

for trial into the next district court to be held in the district

where it is pending. Upon the filing of such petition all fur

ther proceedings in the State courts shall cease, and shall not

be resumed except as hereinafter provided. . . . ”

13 28 U. S. C. §74 (1940) :

Ҥ74. (Judicial Code, section 31.) Same; causes against

persons denied civil rights.

“When any civil suit or criminal prosecution is commenced

in any State court, for any cause whatsoever, against any

person who is denied or cannot enforce in the judicial tri

bunals of the State, or in the part of the State where such

suit or prosecution is pending, any right secured to him by

17

changes in phraseology,14 15 it assumed its present form as

28 U. S. C. §1443 (1958) :16

Ҥ1443. Civil rights cases.

“Any of the following civil actions or criminal pros

ecutions, commenced in a State court may be removed

any law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of the

United States, or of all persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States, or against any officer, civil or military, or other

person, for any arrest or imprisonment or other trespasses or

wrong's made or committed by virtue of or under color of

authority derived from any law providing for equal rights

as aforesaid, or for refusing to do any act on the ground

that it would be inconsistent with such law, such suit or prose

cution may, upon the petition of such defendant, filed in said

State court at any time before the trial or final hearing of

the cause, stating the facts and verified by oath, be removed

for trial into the next district court to be held in the district

where it is pending. Upon the filing of such petition all fur

ther proceedings in the State courts shall cease, and shall not

be resumed except as hereinafter provided. . . . ”

14 Revisor’s Note to 28 U. S. C. §1443 (1958) :

u

“Words ‘or in the part of the State where such suit or

prosecution is pending’ after ‘courts of such States,’ [sic]

were omitted as unnecessary.

“Changes were made in phraseology.”

15 Act of June 25, 1948, ch. 646, §1443, 62 Stat. 869, 938. The

1948 Code made important changes in removal procedure. Prior

to 1948, a party seeking to remove a case or prosecution filed a

removal petition in the state court where the case was pending.

The state court passed upon the propriety of removal and granted

or denied the petition. Its denial was subject to direct review in

the state appellate courts and ultimately this Court, or to col

lateral attack by the filing of the record in the lower federal court

to which removal was authorized by statute. See Metropolitan

Casualty Ins. Co. v. Stevens, 312 U. S. 563 (1941). Under the 1948

Code the removal petition in “any civil action or criminal prose

cution” is filed in the first instance in the federal district court,

28 U. S. C. §1446 (a) (1958), which alone decides whether or not

removal is allowable. Removal petitions in civil actions must be

filed within 20 days following receipt of the initial pleading (or

18

by the defendant to the district court of the United

States for the district and division embracing the

place wherein it is pending:

“ (1) Against any person who is denied or cannot

enforce in the courts of such State a right under any

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States, or of all persons within the juris

diction thereof;

“ (2) For any act under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights, or for refus

ing to do any act on the ground that it would be in

consistent with such law.”

All of the statutes thus far traced from 1815 to the 1948

codification dealt with the removal of civil and criminal

actions against federal officers and others acting under

federal authority; and after 1866 specifically with the re

moval of civil and criminal actions against officers and

persons enforcing, or obedient to, federal civil rights leg

islation or who could not enforce their federal civil rights

in the state courts. In 1875, the fourth and last nineteenth

century civil rights act was enacted, granting to all per

sons within the United States further “equal civil rights”

(Rev. Stat. §641, supra) enforceable under inter alia the

removal provisions of the act of 1866 codified in §641. * 28

the first subsequent pleading stating a removable case, where the

case stated by the initial pleading is not removable), but removal

petitions in criminal prosecutions may be filed at any time before

trial. 28 U. S. C. §1446(b), (c) (1958). Filing of a copy of the

removal petition with the clerk of the state court effects removal

and deprives the state court of jurisdiction to proceed. 28 U. S. C.

§1446(e) (1958). As under earlier practice, the federal court to

which removal is effected may stay subsequent state proceedings,

28 U. S. C. §2283 (1958), and, in criminal prosecutions, takes the

defendant into federal custody by habeas corpus, 28 U. S. C.

§1446(f) (1958).

19

Act of March 1, 1875, ch. 114, 18 Stat. 335. In the same

year, a distinct statutory development extended the removal

jurisdiction in quite different directions and for quite dif

ferent purposes. This was the Judiciary Act of 1875 which,

beginning as a bill to expand the diversity jurisdiction,16

was enacted as a regulation of the general civil (non-

civil-rights) jurisdiction of the circuit courts of the United

States. Act of March 3, 1875, ch. 137, 18 Stat. 470. This

act for the first time17 gave the lower federal courts orig

inal federal-question jurisdiction; its first section gave

the circuit courts jurisdiction “of all suits of a civil nature

at common law or in equity” involving the requisite juris

dictional amount and “arising under” federal law, or be

tween citizens of different states, or citizens of a State and

foreign states or subjects, or between citizens of the same

State claiming under land grants of different States, or

where the United States was plaintiff. 18 Stat. 470. No

original civil-rights jurisdiction was given; this had been

specially created by the civil rights acts and was codified,

in pertinent part, in Rev. Stat. §629, Sixteenth, Seventeenth,

Eighteenth,18 now 28 U. S. C. §1343(1), (2), (3) (1958).19

Section 1 of the 1875 Judiciary Act also gave the circuit

courts exclusive criminal jurisdiction “of all crimes and

offenses cognizable under the authority of the United

States, except as otherwise provided by law, and concur

rent jurisdiction with the district courts of the crimes and

16 F rankfurter & Landis, The Business op the Supreme Court

66-68 (1928).

17 Excepting the short-lived federalist Act of February 13, 1801,

ch. ® , §11, 2 Stat. 89, 92, repealed by the Act of March 8, 1802,

ch. • , 2 Stat. 132.

18 The civil rights jurisdiction of the district courts was sepa

rately codified in Rev. Stat. §563, Eleventh, Twelfth.

19 Original federal jurisdiction in federal question, diversity, and

diversity land grant cases is now provided respectively by 28

U. S. C. §§1331,1332,1354 (1958).

2 0

offenses cognizable therein.” 18 Stat. 470. Sections 2

through 7 of the act dealt with removal jurisdiction. They

authorized removal of “any suit of a civil nature, at law

or in equity” involving the requisite jurisdictional amount

and “arising under” federal law, or between citizens of

different States, or citizens of a State and foreign states

or subjects, or between citizens of the same State claiming

under land grants of different States, or where the United

States was plaintiff. 18 Stat. 470-471. No civil-rights

removal jurisdiction was given, nor any removal jurisdic

tion over criminal cases. Section 5 of the act provided

that, whenever it appeared that jurisdiction of an original

or removed suit was lacking, the circuit court should dis

miss or remand the suit to the state court as justice might

require; “but the order of said circuit court dismissing or

remanding said cause to the State court shall be reviewable

by the Supreme Court on writ of error or appeal, as the

case may be.” 18 Stat. 472.20

The Act of March 3, 1887, ch. 373, 24 Stat. 552, amended

to correct enrollment by the Act of August 13, 1888, ch.

866, 25 Stat. 433, extensively amended the Judiciary Act

of 1875. Although it left the original jurisdiction largely

unaltered (the jurisdictional minimum was raised from

20 “Sec. 5. That if, in any suit commenced in a circuit court or

removed from a State court to a circuit court of the United States,

it shall appear to the satisfaction of said circuit court, at any time

after such suit has been brought or removed thereto, that such

suit does not really and substantially involve a dispute or con

troversy properly within the jurisdiction of said circuit court, or

that the parties to said suit have been improperly or collusively

made or joined, either as plaintiffs or defendants, for the purpose

of creating a case cognizable or removable under this act, the said

circuit court shall proceed no further therein, but shall dismiss

the suit or remand it to the court from which it was removed as

justice may require, and shall make such order as to costs as shall

be ju st; but the order of said circuit court dismissing or remanding

said cause to the State court shall be reviewable by the Supreme

Court on writ of error or appeal, as the case may be.”

21

$500 to $2,000, and creation of diversity jurisdiction by

assignment of a negotiable instrument was precluded), the

Act of 1887 fundamentally rewrote the jurisdictional

grounds for, and the procedure in, civil removal cases.

Section 1, 25 Stat. 434-435, in pertinent part, provided:

“That the second section of said act [of 1875] be,

and the same is hereby, amended so as to read as fol

lows :

“Sec. 2. That any suit of a civil nature, at law or

in equity, arising under the Constitution or laws of

the United States, or treaties made, or which shall be

made, under their authority, of which the circuit courts

of the United States are given original jurisdiction

by the preceding section, which may now be pending,

or which may hereafter be brought, in any State court,

may be removed by the defendant or defendants therein

to the circuit court of the United States for the proper

district. Any other suit of a civil nature, at law or

in equity, of which the circuit courts of the United

States are given jurisdiction by the preceding section,

and which are now pending, or which may hereafter

be brought, in any State court, may be removed into

the circuit court of the United States for the proper

district by the defendant or defendants therein, being

non-residents of that State. And when in any suit

mentioned in this section there shall be a controversy

which is wholly between citizens of different States, and

which can be fully determined as between them, then

either one or more of the defendants actually inter

ested in such controversy may remove said suit into

the circuit court of the United States for the proper

district. And where a suit is now pending, or may be

hereafter brought, in any State court, in which there

is a controversy between a citizen of the State in which

the suit is brought and a citizen of another State, any

2 2

defendant, being such citizen of another State, may

remove such suit into the circuit court of the United

States for the proper district, at any time before the

trial thereof, when it shall be made to appear to said

circuit court that from prejudice or local influence he

will not be able to obtain justice in such State court,

or in any other State court to which the said defendant

may, under the laws of the State, have the right, on

account of such prejudice or local influence, to remove

said cause: Provided, That if it further appear that

said suit can be fully and justly determined as to the

other defendants in the State court, without being

affected by such prejudice or local influence, and that

no party to the suit will be prejudiced by a separation

of the parties, said circuit court may direct the suit

to be remanded, so far as relates to such other defen

dants, to the State court, to be proceeded with therein.

“At any time before the trial of any suit which is

now pending in any circuit court or may hereafter be

entered therein, and which has been removed to said

court from a State court on the affidavit of any party

plaintiff that he had reason to believe and did believe

that, from prejudice or local influence, he wras unable

to obtain justice in said State court, the circuit court

shall, on application of the other party, examine into

the truth of said affidavit and the grounds thereof,

and, unless it shall appear to the satisfaction of said

court that said party will not be able to obtain justice

in such State court, it shall cause the same to be re

manded thereto.

“Whenever any cause shall be removed from any

State court into any circuit court of the United States,

and the circuit court shall decide that the cause was

improperly removed, and order the same to be re

manded to the State court from whence it came, such

23

remand shall be immediately carried into execution,

and no appeal or writ of error from the decision of

the circuit court so remanding such cause shall be

allowed.”

Section 6 of the 1887 act provided: “That the last para

graph of section five of the act [of 1875; this reference is

to the review provision of §5, supra p. 20, n. 20] . . . and

all laws and parts of laws in conflict with the provisions of

this act, be, and the same are hereby repealed. . . . ” 25

Stat. 436-437. But §5 of the 1887 act contained this saving

clause:

“ Sec. 5. That nothing in this act shall be held,

deemed, or construed to repeal or affect any juris

diction or right mentioned either in sections six hun

dred and forty-one, or in six hundred and forty-two, or

in six hundred and forty-three, or in seven hundred and

twenty-two, or in title twenty-four of the Revised Stat

utes of the United States, or mentioned in section eight

of the act of Congress of which this act is an amend

ment, or in the act of Congress approved March first,

eighteen hundred and seventy-five, entitled ‘An act to

protect all citizens in their civil and legal rights.’ ” 21

Like the Act of 1875 which it amended, the Act of 1887 did

not affect federal removal jurisdiction in criminal cases.

21 The provisions to which reference is made are as follows:

§641 is the civil rights (civil and criminal) removal statute set

out supra pp. 15-16; §642 requires the clerk of the circuit court to

issue a writ of habeas corpus cum causa for the body of the defen

dant who has removed any suit or prosecution under §641; §643

authorizes removal of “any civil suit or criminal prosecution”

against a federal revenue officer, or any officer or person acting

under the federal voting laws; §722 describes the law to be applied

in civil rights (civil and criminal) removed cases; title 24 of the

Revised Statutes is the civil rights title; §8 of the Judiciary Act

of 1875 provides for service of process on absent defendants in civil

actions to enforce or remove liens or incumbrances on property

within the court’s jurisdiction; the Act of March 1, 1875, is the

fourth civil rights act, supra pp. 18-19.

24

As indicated above, the Judicial Code of 1911 technically

repealed Rev. Stat. §641, for the purpose of abolishing the

jurisdiction of the circuit courts. It carried forward §641’s

exact provisions as a grant of civil rights (civil and crim

inal) removal jurisdiction to the district courts by virtue

of Judicial Code §31, supra, p. 16, n. 12. The civil (non-

civil-rights) removal provisions of the Judiciary Act of

1887, amending that of 1875, were carried forward virtu

ally unchanged as Judicial Code §§28-30. Section 28, the

principal provision, reenacted inter alia the 1887 prohibi

tion of appellate review of remand orders, supra pp. 22-23.22

22 36 Stat. 1094-1095. Italicized in pertinent part, §28 reads:

Sec. 28. Any suit of a civil nature, at law or in equity,

arising under the Constitution or laws of the United States,

or treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority,

of which the district courts of the United States are given

original jurisdiction by this title, which may now be pending

or which may hereafter be brought, in any State court, may

be removed by the defendant or defendants therein to the

district court of the United States for the proper district.

Any other suit of a civil nature, at law or in equity, of which

the district courts of the United States are given jurisdiction

by this title, and which are now pending or which may here

after be brought, in any State court, may be removed into the

district court of the United States for the proper district by

the defendant or defendants therein, being non-residents of

that State. And when in any suit mentioned in this section

there shall be a controversy which is wholly between citizens

of different States, and which can be fully determined as be

tween them, then either one or more of the defendants actu

ally interested in such controversy may remove said suit into

the district court of the United States for the proper district.

And where a suit is now pending, or may hereafter be brought,

in any State court, in which there is a controversy between

a citizen of the State in which the suit is brought and a citizen

of another State, any defendant, being such citizen of another

State, may remove such suit into the district court of the

United States for the proper district, at any time before the

trial thereof, when it shall be made to appear to said district

court that from prejudice or local influence he will not be able

to obtain justice in such State court, or in any other State court

to which the said defendant may, under the laws of the State,

have the right, on account of such prejudice or local in

fluence, to remove said cause: Provided, That if it further

25

Section 297 of the Code, 36 Stat. 1168, specifically repealed

the Judiciary Act of 1875 and §§1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 of the

Judiciary Act of 1887—that is, every part of the act of 1887

except §5, the civil rights saving clause, supra p. 23. Sec

tion 297 further provided, 36 Stat. 1169:

“Also all other Acts and parts of Acts, in so far as

they are embraced within and superseded by this Act,

are hereby repealed; the remaining portions thereof

to be and remain in force with the same effect and to

the same extent as if this Act had not been passed.” 23

appear that said suit can be fully and justly determined as to

the other defendants in the State court, without being affected

by such prejudice or local influence, and that no party to the

suit will be prejudiced by a separation of the parties, said

district court may direct the suit to be remanded, so far

as relates to such other defendants, to the State court, to be

proceeded with therein. At any time before the trial of

any suit which is now pending in any district court, or

may hereafter be entered therein, and which has been re

moved to said court from a State court on the affidavit of

any party plaintiff that he had reason to believe and did

believe that, from prejudice or local influence, he was

unable to obtain justice in said State court, the district court

shall, on application of the other party, examine into the truth

of said affidavit and the grounds thereof, and, unless it shall

appear to the satisfaction of said court that said party will

not be able to obtain justice in said State court, it shall cause

the same to be remanded thereto. Whenever any cause shall

be removed from any State court into any district court of the

United States, and the district court shall decide that the cause

was improperly removed, and order the same to be remanded

to the State court from whence it came, suck remand shall be

immediately carried into execution, and no appeal or writ

of error from the decision of the district court so remanding

such cause shall be allowed: Provided, That no case arising

under an Act entitled “An Act relating to the liability of

common carriers by railroad to their employees in certain

cases,” approved April twenty-second, nineteen hundred and

eight, or any amendment thereto, and brought in any State

court of competent jurisdiction shall be removed to any court

of the United States.

23 Section 297 of the Judicial Code of 1911 was not affected by

the enactment of Title 28, U. S. C. in 1948. See 62 Stat. 869, 996.

26

Sections 28, 29 and 30 of the Judicial Code appear as 28

U. S. C. §§71, 72 and 73 (1940), respectively. By reason

of the abolition of the writ of error in all cases, civil and

criminal, in 1928,24 the sentence in §28 carrying forward

the 1887 preclusion of review by “appeal or writ of error,”

supra pp. 24-25, n. 22, omits reference to the writ. It reads:

“ . . . Whenever any cause shall be removed from any State

court into any district court of the United States, and the

district court shall decide that the cause was improperly

removed, and order the same to be remanded to the State

court from whence it came, such remand shall be immedi

ately carried into execution, and no appeal from the deci

sion of the district court so remanding such cause shall be

allowed.” 28 U. S. C. §71 (1940). No other significant

change appears.25

The 1948 Code (A) reenacted the civil rights (civil and

criminal) removal jurisdiction without substantive change,

28 U. S. C. §1443 (1958), supra pp. 17-18; (B) significantly

broadened the scope of removal jurisdiction (civil and

criminal) in cases involving federal officers and persons

acting under them, 28 U. S. C. §1442 (1958); (C) substan

tially rewrote the jurisdictional bases of general civil re

moval jurisdiction (descendent from the Judiciary Acts of

1875,1887, the Judicial Code of 1911, §§28-30 and 28 U. S. C.

§§71-73 (1940)), 28 U. S. C. §1441 (1958) ;26 (D) con

24 Act of January 31, 1928, ch. 14, 45 Stat. 54. The enactment

is general and has no special pertinence to removal cases.

25 Apart from the omission of reference to the writ of error, the

1940 sections differ from those of the 1911 Judicial Code only in

that 28 U. S. C. §71 (1940) reflects the Act of January 20, 1914,

eh. 11, 38 Stat. 278, limiting removal in actions brought against

railroads and common carriers for damages for delay, loss of, or

injury to property received for transportation.

26 §1441. Actions removable generally.

(a) Except as otherwise expressly provided by Act of Con

gress, any civil action brought in a State court of which the

2 7

siderably altered the removal procedures for both civil and

criminal actions, 28 U. S. C. §§1446, 1447 (1958), see supra

pp. 17-18, n. 15; and (E) inadvertently omitted the provi

sion of the earlier general civil removal statutes which pro

hibited appellate review of remand orders. The Act of

May 24, 1949, ch. 139, §84(b), 63 Stat. 89, 102, supplied

the latter omission by adding a new subsection (d) to 28

U. S. C. §1447. The 1949 act was an omnibus technical

amendment statute, intending no “enactment of substantive

law, but merely correction of errors, misspellings, and in

accuracies in revision.” 27 The House Report says that the

purpose of the new subsection is “to remove any doubt

that the former law as to the finality of an order of remand

to a State court is continued.” 28 28 U. S. C. §1447(d) reads:

district courts of the United States have original jurisdiction,

may be removed by the defendant or the defendants, to the

district court of the United States for the district and division

embracing the place where such action is pending.

(b) Any civil action of which the district courts have origi

nal jurisdiction founded on a claim or right arising under the

Constitution, treaties or laws of the United States shall be

removable without regard to the citizenship or residence of

the parties. Any other such action shall be removable only if

none of the parties in interest properly joined and served as

defendants is a citizen of the State in which such action is

brought.

(e) Whenever a separate and independent claim or cause

of action, which would be removable if sued upon alone, is

joined with one or more otherwise non-removable claims or

causes of action, the entire case may be removed and the dis

trict court may determine all issues therein, or, in its discre

tion, may remand all matters not otherwise within its original

jurisdiction.

27 Mr. O’Connor in the Senate, 95 Cong. Ree. 5827 (81st Cong.,

1st Sess. 5/6/49). Senator O’Connor reported the bill from the

Senate Committee on the Judiciary. 95 Cong. Rec. 5020 (81st

Cong., 1st Sess. 4/26/49).

28 H. R. Rep. No. 352, 81st Cong., 1st Sess. (1949), 2 U. S. Code

Cong. Serv., 81st Cong., 1st Sess., 1949, 1254, 1268 (1949).

“(d) An order remanding a case to the State court

from which it was removed is not reviewable on appeal

or otherwise.”

A R G U M E N T

T h e R e lie f S ough t by th e S ta te o f G eo rg ia S h o u ld N ot

Be G ra n te d I f ( I ) th e C o u rt o f A ppea ls A rguab ly H as

J u r is d ic t io n o f th e Case P e n d in g B e fo re It, a n d (II) th e

C o u rt o f A ppea ls C ould A rguab ly D ecide th e Case in

F a v o r o f R e sp o n d e n ts .

The stay order of the Court of Appeals which the State

of Georgia seeks to have this Court review by extraordinary

writs is an interim order temporarily staying the District

Court’s remand “pending final disposition of this appeal

on the merits or the earlier order of [the Circuit] . . .

Court” (App. p. 23). Notwithstanding Georgia’s challenge

to the jurisdiction of the Court of Appeals to entertain the

pending proceeding, that court “unquestionably had the

power to issue a restraining order for the purpose of pre

serving existing conditions pending a decision upon its

own jurisdiction.” United States v. United Mine Workers,

330 U. S. 258, 290 (1947) (alternative ground). In the

granting of such interim orders to preserve the subject of

the litigation and protect the parties pending final deter

mination of their rights, the lower federal courts have a

broad discretion reviewable only for abuse. Prendergast

v. New York Telephone Co., 262 U. S. 43, 50-51 (1923);

Deckert v. Independence Shares Corp., 311 U. S. 282, 290

(1940).29

29 Thus, the appropriate scope of review of the Fifth Circuit’s

stay order is considerably narrower than would be the scope of

this Court’s review of a District Court order denying remand.

See, e.g., Maryland v. Soper (No. 1), 270 TJ. S. 9 (1926); Colorado

v. Symes, 286 U. S. 510 (1932). Such an order is final, and once

29

The temporary stay was justified here by a number of

considerations. As Georgia concedes, the underlying prose

cutions of respondents arose from demonstrations (Petn.,

p. 10) in which respondents sought to exercise their consti

tutionally protected rights of free expression, Edwards v.

South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229, 235 (1963); Henry v. Rock

Hill, 84 S. Ct. 1042 (1964), to protest racial discrimination

in places of public accommodation. See Garner v. Louisiana,

368 U. S. 157, 185, 201-202 (1961) (Mr. Justice Harlan,

concurring) and cases cited. “These freedoms are delicate

and vulnerable, as well as supremely precious in our society.

The threat of sanctions may deter their exercise almost as

potently as the actual application of sanctions.” N.A.A.C.P.

v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 433 (1963). See Bantam Books,

Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58 (1963). In their removal

petition, respondents alleged that their arrests were ef

fected for the sole purpose of perpetuating such racial

segregation (App. pp. 6-7) ; that they were indicted and

their cases set for trial under Georgia’s criminal trespass

statute, Ga. Code Ann., §26-3005 (1963 Supp.), supra; that

these prosecutions were for doing acts under color of au

thority derived from the federal Constitution and laws

(App. pp. 6-7); that respondents could not enforce their fed

eral rights in the Georgia courts because, inter alia, Georgia

by statute, custom and usage maintains a policy of racial

discrimination (App. p. 7) ;30 and that removal was sought

the ease goes to trial in the District Court, “a judgment of ac

quittal in that court is final,” Maryland v. Soper, supra, at 30,

irretrievably depriving the State of criminal jurisdiction in the

removed case.

30 Georgia’s assertion in this Court that “the official policy of

the City of Atlanta is one of integration” (Petn. p. 17) has, of

course, no support in the record. As respondents pointed out in

the Court of Appeals, Georgia is seeking to sustain a remand order

which the District Court issued without a hearing at which respon

30

to protect respondents’ rights under the First and Four

teenth Amendments (App. p. 6). In their motion for a stay

pending appeal, respondents further alleged that unless the

remand order was stayed, respondents were in immediate

danger of having their bonds raised by the Fulton Superior

Court (App. p. 16); that many of them would be unable to

make the increased bond and so would be required to re

main in jail by reason of their poverty (App. p. 16); that

they would be tried in the immediate future in the Superior

Court, rendering moot the issues presented by their appeal

to the Fifth Circuit (App. p. 16); and that these Georgia

criminal prosecutions prevented them from exercising their

federal constitutional rights (App. p. 16). Eesponsive to

these allegations, Georgia in its motion to dismiss asserted

no circumstances showing that postponement of the prose

cutions pending disposition of the Fifth Circuit appeal

would work the slightest injury to the State (App. 18-21)

and even in its petition to this Court asserts no circum

stances of exigency save those common to “every prosecu

tion in a State Court resulting from a civil rights ‘sit-in’

or other protest demonstration. . . . ” (Petn., p. 31). Clearly,

on this record, “the balance of injury as between the par

ties” 81 favors issuance of the stay. See Baines v. Danville,

321 F. 2d 643, 644 (4th Cir. 1963). Continued state prose

cution serves no legitimate State interest if the removal is

proper. It does (A) take appellants to trial in courts

where, by their allegations, they cannot enforce their fed

eral rights, (B) subject them to the restraints of the state 31

dents “would have been able to show facts . . . sustaining the alle

gations of their removal petition” (App. p. 16), including the

allegation that Georgia by statute, custom and usage maintains

a policy of racial discrimination.

31 Prendergasl v. New York Telephone Co., 262 U. S. 43, 51

(1923).

31

criminal process, cf. Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S. 257, 263

(1879), during the very period when their rights to federal

removal is being tested, (C) potentially meet the question

of the propriety of the removal, cf. Arceneaux v. Louisi

ana, 84 S. Ct. 777 (1964); and (D) thus punish them for

exercising, and inhibit their exercise of, their federal rights

including rights of free expression and to equal protection

of the laws. See pp. 53-54 infra.

In these circumstances, this Court may appropriately

vacate the Fifth Circuit’s stay order as an abuse of discre

tion only if (A) it is clear beyond reasonable argument that

the Fifth Circuit lacks jurisdiction of the case pending be

fore it, or (B) it is clear beyond reasonable argument that,

although the Fifth Circuit may have jurisdiction of the

case, its only proper exercise of that jurisdiction must be

to affirm the remand order of the District Court.

I.