Grant v. United States Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Grant v. United States Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1972. 1293ac08-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e8463e78-e355-43d4-824c-74a5ddba6ecd/grant-v-united-states-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

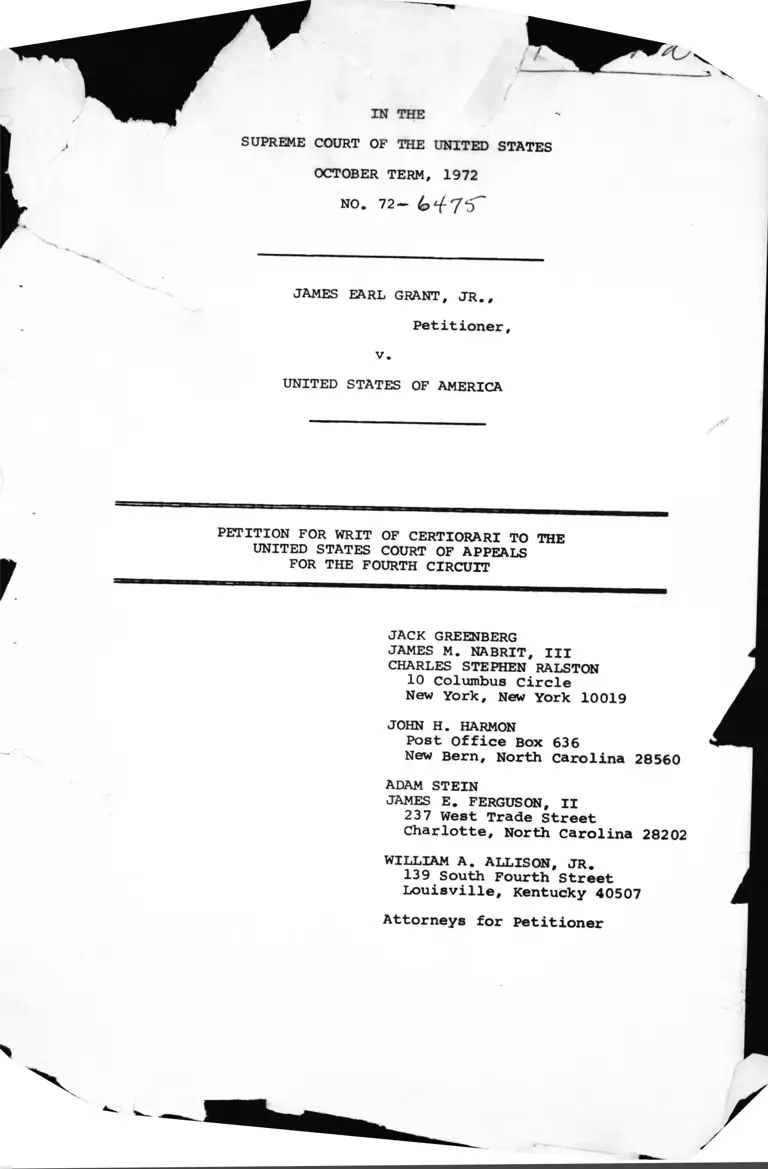

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1972

NO. 72—

JAMES EARL GRANT, JR.,

Petitioner,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN H. HARMON

Post Office Box 636

New Bern, North Carolina 28560

ADAM STEIN

JAMES E. FERGUSON, II

237 West Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

WILLIAM A. ALLISON, JR.139 South Fourth Street

Louisville, Kentucky 40507

Attorneys for Petitioner

Of racially identifiable schools (A. 488). For example, the

completion of Northwest Junior High and Bearden High resulted in

revision of secondary zone structures in the general West

Knoxville area. The irregularly shaped West High School zone

established in 1968 (A. 440; cf. X7) excludes a nearby black

residential area which is entirely zoned into Rule High. The

school district enlarged the West facility at the same time

Bearden High was constructed (A. 442-43) with the result that,

particularly as the zones were drawn, none of the black students

in the Rule area are assigned to the heavily white Bearden or

West High Schools.

Nor did the reexamination of zones in western Knoxville

alter the character of Rule and Beardsley Junior High Schools —

one white and the other black, located next door to one anotherf"

The Beardsley grade structure is still unique, both in this

system and in this state— The Beardsley Junior High zone is

virtually coterminate with the black residential area (A. 385)

but the zones were not redrawn nor the schools paired as

recommended^by^the University of Tennessee Title IV Center

(A. 398.) ~ *

!_/ In 1967 Dr. Bedelle could not A .226a)• explain this phenomenon (18,165

10/ Directory of Public Elementary

Districts, Fall 1968 (OCR-101-70, 0

Department of Health, Education and

and Secondary Schools in Selected

ffice of Civil Rights, u.S.

Welfare) 1379-1410 (1970).

T t t t r 1t?aRulteeandm«LiSHtrr :iVe of the

The district court ordered' theennesB?edra^y(I?r31^tred 387-89>

10

Almost all of Knoxville's portable classrooms are located

at white schools (X18, A.516) despite the availability of excess

capacity at black schools (A. 391-92). The location of these

portable classrooms obviates any need to adjust zone lines between

white and black schools to avoid overcrowding of the permanent

facilities at the schools. For example, the Board operated

the Negro Green Elanentary School at half capacity while using

portable classrooms to contain overcrowding at the predominantly

white Huff Elementary School three miles away (A. 430).

The attitude of this school system toward desegregation is

most graphically revealed by its perpetuation of racially identi

fiable faculties. No teachers have ever been transferrred to

desegregate a school's faculty (A. 467); in 1969-70 twenty-one

schools had no Negro teachers (A. 187-94) and two Negro schools

(Sam Hill and Mountain View) had no white teachers (ibid.),

despite Dr. Bedelle's view that faculty desegregation requires

"substantial" numbers of minority teachers at each school (A. 461).

Significant is the district's selection of faculties at newly opened

schools: Bearden High had no black teachers (A. 192), Central

but one (along with 70 white teachers) (A. 193), and Northwest

Junior High only two (ibid.). Conversely, faculty racial pre

dominance continued to mirror student body population, and thus

to perpetuate racial identifiability: Lonsdale had one Negro

and 17 white teachers, Sam Hill 16 Negro and no white teachers;

Beardsley, 20 black and four white instructors, Rule onekblack

and 58 white teachers (A. 187-94).

11

Similarly, assignments of principals have conformed to

established patterns with no attempts to eliminate racially

identifiable schools. A black principal was not assigned to a

formerly white school until after it had become majority black

(A. 472); when black schools were closed (18,165 A.169a), their

former principals did not get assigned to vacancies at white

schools (A. 473). In 1969-70, no Negro was the principal of

a predominantly white student body school. Three whites were

assigned as principal at predominantly-black schools (A. 187-94);

all of these schools, however, had originally been white schools

(see A . 472-74).

The school district’s explanation for these results was

that it never transferred teachers or principals without their

consent (A. 467) and they considered whether a teacher could

"understand" a particular neighborhood in making assignments (A. 470)

The results of these policies can be summarized as follows;

During the 1969-70 school year, ten years after the initiation

of this lawsuit, the Knoxville school system consisted of 47

elementary, 9 junior high, and 9 high schools (A. 168-77) .

Although black students constitute only 16% of the Knoxville

school population (A. 177), 83% of all black students attended

majority-black schools (A. 309, 520).

The following table illustrates the changing racial

composition of black schools since this suit was commenced:

12

13/ 14/ 15/

1962-163 1966-67 1969-70

School W B W B W B

16/

Austin 0 710 1 432 10 739

Beardsley 0 672 6 471 4 357

Cansler 0 361 0 221 12 206

Eastport 0 592 1 437 0 442

Green 0 677 21 421 5 276

Maynard 0 491 2 452 7 375

Mountain View 0 357 0 325 0 303

Sam Hill 0 488 0 498 4 347

Vine 0 776 1 619 5 628

These schools were all-white in 1962-■63 ;and remained all

in 1969-70: Claxton, Giffin , Lockett, Oakwood , Perkins, South

Knoxville and West View. All-White schoolsi in 1962-63 which

presently enroll ten or fewer black students are McCampbell,

Sequoyah and South. Schools which had ten or fewer black students

in 1962-63 and 1969-70 are Brownlow, Flenniken and McCallie (15,432

A. 105a, A. 138-39).

Faculties reflected student body racial proportions (Compare

A.138-48 with A.188-95). Twenty schools still have no faculty

desegregation (A. 471).

The district court denied all systemwide relief except "to

i

find that the Board should accelerate the integration of faculties"

13/ 15,432 A.105a.

14/ 18,165 A . 42a-47a.

15/ A.138-49.

16/ Austin-East complex.

13

(A.321) . The Court also directed the Board “to revise the zones

in this area for the 1970 school term to eliminate overcrowding

at Rule and to utilize existing capacity at Beardsley" (A. 314)

and “to keep adequate records to show enforcement of its transfer

plan" (A. 317). In all other respects, the Court denied plaintiffs

relief.

14

APPENDIX B

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF § 718

The provision for attorneys’ fees in school desegregation

cases was first introduced in the Senate as § 11 of the Emergency

School Aid and Quality Integrated Education Act of 1971, S. 1557.

The bill was reported to the Senate floor in April of 1971, and

§ 11 was described in the report of the Senate Committee on

Labor and Public Welfare. Sen. Rep. No. 92-61, 92d Cong., 1st

Sess. The report, while not setting out the precise text of

§ 11, describes it fully. its provisions were substantially

the same as those of § 718 as it finally passed, with two

important exceptions.

First, payment of attorneys’ fees in school cases was to

be made by the United States from a special fund established by

the Act. Second, the section provided that "reasonable counsel

fees, and costs not otherwise reimbursed for services rendered,

and costs incurred, after the date of enactment of the Act" were

T 7

to be awarded to a prevailing plaintiff. it should be noted

1/ The description of § 11 in the Senate report is as follows:

This section states that upon the entry of a

final order by a court of the united States against

a local educational agency, a State (or any agency

thereof), or the Department of Health, Education,

and Welfare, for failure to comply with any provision

of the Act or of title I of the Elementary and

Secondary Education Act of 1965, or for discrimination

on the basis of race, color, or national origin in

violation of title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

or of the Fourteenth Article of amendment to the

Constitution of the united States as they pertain to

that the quoted language was omitted from § 718.

On April 21, 1971 Senator Dominick of Colorado introduced

an amendment to delete § 11 in its entirety from the bill. The

basis for the deletion was that it was not proper that the United

States should bear the costs of attorneys' fees but rather that

such costs should be imposed on the school boards responsible

for the maintenance of unconstitutionally segregated school

systems. Senator Dominick's amendment passed. 117 Cong. Rec.

S.5324-31 (daily ed. April 21, 1971).

On the next day. Senator Cook of Kentucky, who was also

opposed to § 11, introduced a new amendment identical to the

present § 718 and after two days of debate that amendment was

passed. 117 Cong. Rec. S.5483-92 (daily ed. April 22, 1971)

and S.5534-39 (daily ed. April 23, 1971). The section as

passed became § 16 of S.1557, and S.1557 as a whole was passed

on April 26, 1971 without any further debate of the attorneys'

fees provision. 117 Cong. Rec. S.5742-47 (daily ed. April 26,

l / cont'd

elementary and secondary education, such court shall,

upon a finding that the proceedings were necessary to

bring about compliance, award, from funds reserved

pursuant to section 3(b)(3), reasonable counsel fees,

and costs not otherwise reimbursed for services

rendered, and costs incurred, after the date of enact

ment of the Act to the party obtaining such order.

In any case in which a party asserts a right to be

awarded fees and costs under section 11, the United

States shall be a party with respect to the appropri

ateness of such award and the reasonableness of counsel

fees. The Commissioner is directed to transfer all

funds reserved pursuant to section 3(b)(3) to the

Administration Office of the United States Courts for

the purpose of making payments of fees awarded pursuant

to section 11.

Senate Report No. 92-61, 92d Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 55-56.

1971).

Subsequently, on August 6, 1971, the Senate passed a re

lated statute, S.659, the Education Amendments of 1971. See,

U.S. Code Congressional and Administrative News, 1971, vol. 6

2/

p. 2333. Both Senate bills were then sent to the House. On

November 5, 1971, the House, in considering a parallel measure,

H.R.7248, amended S.659. The House struck everything after the

enactment clause of the Senate bill and substituted a new text

based substantially on the House bill and in effect combining

provisions of S.1557 and S.659. Ibid. In so amending the Senate

bil1 3/G H°USe OITlitted the attorneys' fees provision (ic[., at

2406) without debate.

The amended Senate bill was then returned to the Senate

with request for a conference, which request was referred to

the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare. However, the

Committee, instead of acceding to the request for a conference,

reported S.659 back to the Senate floor with amendments to the

House substitute. Those amendments re—included the counsel fee

provision of S.1557 in exactly the same form as it had originally

passed the Senate in April. Id. at 2333 and 2406. On March 1,

1972, the Senate passed S.659 as reported to it by the Committee,

and this amended bill was then sent to conference. The Senate-

— Sen. Rep. No. 92-604, 92d Cong., 2nd Sess., Report of the

Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare on the Message of the House on S.659.

2/ Conference Report No. 798, 92d Cong., 2nd Sess.

« #

House conference made further amendments and reported the bill

to both houses with the continued inclusion of the attorneys'

fees provision exactly as passed by the Senate. _id. at 2406.

The provision was now § 718 of the Education Amendments of 1972.

The conference bill was passed with no further debate on § 718

by the Senate on May 24, 1972 and by the House on June 8, 1972

(Id. at 2200), and was signed into law by the President on June

23.

Thus, the only debate concerning § 718 occurred in connec

tion with its original passage by the Senate in April of 1971.

As noted above, there was no debate in the House concerning

its deletion when the House amended S.659 and there was no

further debate in the Senate or the House with regard to the

passage of the conference bill.

Legal Services of New Jersey

78 New Street

New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901

By: ________ _______________

Melville D. Miller, Jr.

Joseph Harris David

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

By: Julius L. Chambers, John C. Boger, and

Jon C. Dubin

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Essex-Newark Legal Services

By: Hugh Heisler and Paul Giordano

8 Park Place

Newark, New Jersey 07102

(201) 624-4500

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and

Education Fund

By: Ruben Franco and Arthur A. Baer

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

Margaret Welch

7 South Street

Newark, New Jersey 07102

(201) 292-6542

Michaelene Loughlin

Seton Hall Law School Clinic

1095 Raymond Blvd

Newark, NJ 07102

(201) 642-8848

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

41