State of Louisiana v. Hays Brief Amicus Curiae in Support for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 30, 1995

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. State of Louisiana v. Hays Brief Amicus Curiae in Support for Appellants, 1995. d0d550d4-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e89c338c-8b84-4d08-b727-5c8ca7b99b63/state-of-louisiana-v-hays-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-for-appellants. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

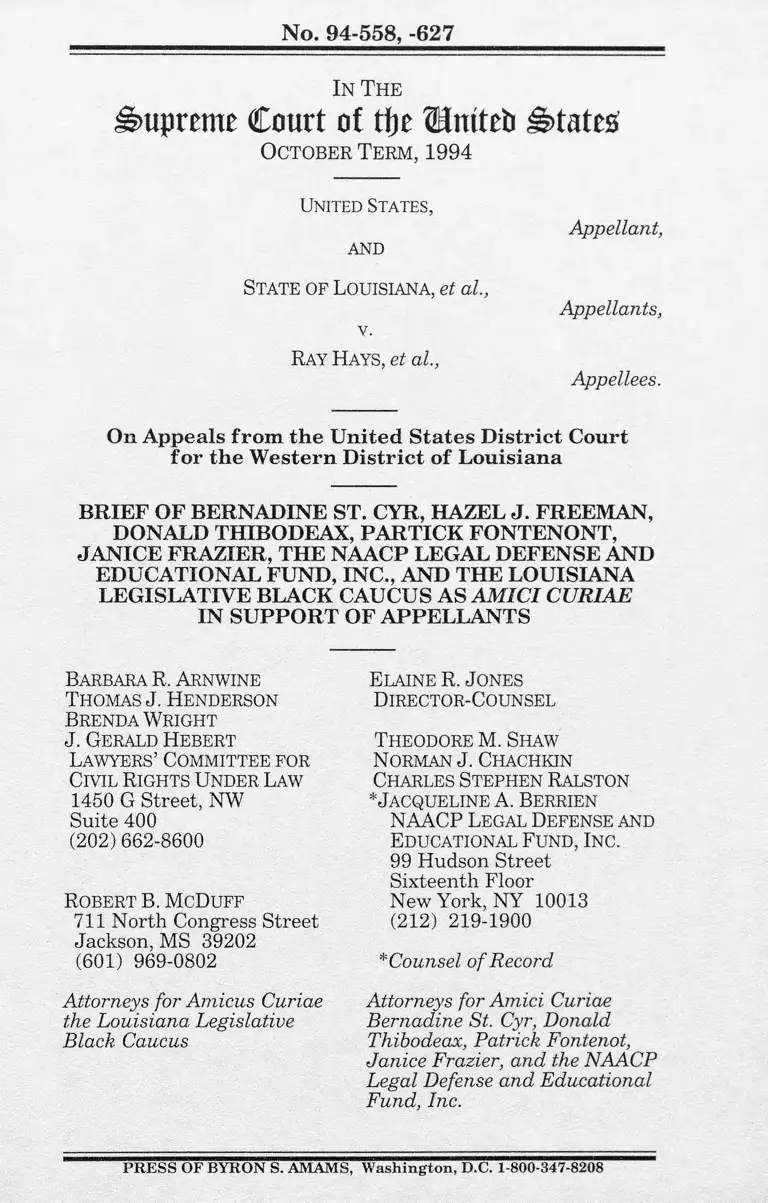

No. 94-558, -627

In T he

Supreme Court of tfje H m teb S>tate£

October Term , 1994

United States,

and

State of Louisiana, et a l,

y.

Ray Hays, et al.,

Appellant,

Appellants,

Appellees.

On Appeals from the United S tates D istrict Court

fo r the W estern D istrict of Louisiana

BRIEF OF BERNADINE ST. CYR, HAZEL J. FREEMAN,

DONALD THIBODEAX, PARTICK FONTENONT,

JANICE FRAZIER, THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AND THE LOUISIANA

LEGISLATIVE BLACK CAUCUS AS AMICI CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS

Barbara R. Arnwine

Thomas J. Henderson

Brenda Wright

J. Gerald Hebert

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1450 G Street, NW

Suite 400

(202) 662-8600

Robert B. McDuff

711 North Congress Street

Jackson, MS 39202

(601) 969-0802

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

the Louisiana Legislative

Black Caucus

Elaine R. J ones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

* J acqueline A. Berrien

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

* Counsel o f Record

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

Bernadine St. Cyr, Donald

Thihodeax, Patrick Fontenot,

Janice Frazier, and the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

PRESS OF BYRON S. AMAMS, Washington, D.C. 1-800-347-8208

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities ....................... ii

Interest of Amici Curiae ..................................... 1

Summary of Argument ................................... 2

ARGUMENT

Introduction ........................................................... 3

T h e U n c o n t r o v e r t ib l e H is t o r y o f

D is c r im in a t io n a g a in s t A f r ic a n

A m e r ic a n s in Lo u is ia n a , t h e

R e p e a t e d D il u t io n o f t h e ir V o t in g

St r e n g t h , a n d t h e P e r s is t e n c e o f

W h it e Bl o c V o t in g , A m p l y J u s t if ie d

t h e C h a l l e n g e d D is t r ic t in g P l a n . . . . . . 5

A. The History of Egregious

Discrimination against

African Americans in

Louisiana .................................................... 6

1. Discrimination in voting.............. 7

2. Discrimination in education

and other areas ................................. 12

3. Continuing impact of this

discrimination......... ~ . 14

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

Page

B. The State’s Consistent Dilution

of African-American Voting

Strength in the Drawing of

D istricts................................................. 16

C. The Persistence of Racially

Polarized V oting..................................... 22

D. The "Totality' of the Circumstances" . . 25

Conclusion......................... ........................................... 28

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964) ....................... 9

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) ...................................................... 9, 13

Bussie v. Governor of Louisiana, 333 F.

Supp. 452 (E.D. La. 1971), affd and

modified, 457 F.2d 796 (5th Cir. 1971),

vacated sub nom. Taylor v. McKeithen,

407 U.S. 191 (1972), on remand, 499

F.2d 893 (5th Cir. 1974) ................ . 16

Ill

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Chisom v. Edwards, 690 F. Supp. 1524 (E.D.

La. 1988), vacated, 853 F.2d 1186

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 488 U.S.

955 (1988) . ............................................... .. 12

Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U .S.__ , 115 L. Ed.

2d 348 (1991) . ..................... .................... .. 2

Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of

Gretna, 636 F. Supp. 1113 (E.D. La.

1986) , affd, 834 F.2d 496 (5th Cir.

1987) , cert, denied, 492 U.S. 905 (1989) . . . . 12

City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488

U.S. 469 (1989) .......................................... . 5, 26

Clark v. Edwards, 725 F. Supp. 285 (M.D. La.

1988) , vacated sub nom. Clark v. Roemer,

750 F. Supp. 200 (M.D. La. 1990), modified,

777 F. Supp. 445 (M.D. La. 1990), vacated,

501 U.S. 1246 (1991), on remand, 777

F. Supp. 471 (M.D. La. 1991), appeal

dismissed, 958 F.2d 614 (5th Cir.

1992) ................... 1 In, 12, 15, 23, 25, 26

Clark v. Roemer, 777 F. Supp. 471 (M.D.

La. 1991), appeal dismissed, 958

F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1992) .............................. 26n

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915)............ 8n

IV

Cases (continued):

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd.,

417 F.2d 801 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

396 U.S. 904 (1969)....... ........................... .. . 13n

Houston Lawyers Association v. Attorney

General of Texas, 501 U.S. , 115

L. Ed. 2d 379 (1991) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

International Bhd. of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) .......................... 24n

Johnson v. DeGrandy,__ U .S.___ , 129 L.

Ed. 2d 775 (1994)..................................... 6n, 25

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939) . . . . . . . . . . . . 4n

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145

(1965) ........................................ 7, 9, 10

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D.

La. 1983) ...................................................passim

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ----- . . . . . . 2

Parnell v. Rapides Parish School Bd.,

425 F. Supp. 399 (W.D. La. 1976),

affd in part, 563 F.2d 180 (5th

Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 438 U.S.

915 (1978) ................ .. ................... .. l ln

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 U.S.

__ , 120 L. Ed. 2d 674 (1992) ..................... .. 29

Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance

Comm’n, 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La.

1967), affd per curiam, 389 U.S. 571

(1968) ................................................... 11-12, 13

Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S.

265 (1978) ................ 26

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U .S .__ , 125 L. Ed. 2d

511 (1993) ......... 29

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) ..................... 9

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)............ 2, 28

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey,

430 U.S. 144 (1977)............................................... 2

United States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp.

353 (E.D. La. 1963), affd, 380

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th

Cir. 1973), affd sub nom. East

Carroll Parish School Bd. v. Marshall,

424 U.S. 636 (1976)..................... .. . . 6n, l ln

VI

Other Authorities:

Richard L. Engstrom, Stanley A. Halpin,

Jr., Jean A. Hill, and Victoria

M. Caridas-Butterworth, Louisiana,

in Quiet Revolution in the South: The

Impact of the Voting Rights Act 1965-

1990 (Chandler Davidson and Bernard

Grofman, eds., 1994) . ............................... lln , 17

Alcee Fortier, History of Louisiana (1904) .............. 8n

Louisiana Act 538 of 1960 .......................................... . 9

Alice Love, David Duke Wants to Run for New

Cajun House Seat, 39 Roll Call. August

4, 1994 ............................................................... 14

1978 Almanac of American Politics ....................... 19n

Nomination of William Bradford Reynolds to

be Associate Attorney General of the

United States; Hearings Before the

Senate Committee on the Judiciary,

99th Cong. 1st Sess. (1985) ..................... 20n

Lawrence N. Powell, Read My Liposuction:

The Makeover o f David Duke, 203 New

Republic 18 (Oct. 15, 1990).......................... 14n

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

vu

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

Hon. George C. Pratt, Symposium, The Supreme

Court and Local Government Law, The

1992 Term, 10 Touro L. Rev. 295 (1994) . . 29n

Bruce A. Ragsdale and Joel D. Treese, Black

Americans in Congress. 1870-1989 (1990) . . . 5n

Nos. 94-558, -627

In T h e

Supreme Court of tfje Um teb £>tate£

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1994

U n it e d St a tes ,

a nd

St a te o f L o u isia n a , et al,

v.

R a y H a ys , et al,

Appellant,

Appellants,

Appellees,

On Appeals from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Louisiana

BRIEF OF BERNADINE ST. CYR, HAZEL J.

FREEMAN, DONALD THIBODEAX, PATRICK

FONTENOT, JANICE FRAZIER, THE LOUISIANA

LEGISLATIVE BLACK CAUCUS, and THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

as AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS

In t e r e st o f A m ic i C u riae1

Bemadine St. Cyr, Hazel J. Freeman, Donald

Thibodeax, Patrick Fontenot, and Janice Frazier are African-

1 Letters consenting to the submission of this brief have been filed

with the Clerk of this Court.

2

American voters residing in the State of Louisiana. The

Louisiana Legislative Black Caucus includes the African-

American members of the Louisiana Legislature, all of

whom are elected representatives and voters of the State of

Louisiana, and many of whom reside in the present Fourth

Congressional District. The Caucus supported the creation

of the current Fourth Congressional District, a position

joined by a majority of Louisiana’s elected legislature,

including both white and African-American legislators.

These individual voters and the Caucus sought to intervene

in the District Court to protect the interest of voters in a

reapportionment plan that complied with the requirements

of the Voting Rights Act and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States, but

that intervention was denied. The NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc. ("the Fund") is a non-profit

corporation that was established for the purpose of assisting

African Americans in securing their constitutional and civil

rights. This Court has noted the Fund’s "reputation for

expertness in presenting and arguing the difficult questions

of law that frequently arise in civil rights litigation." NAACP

v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 422 (1963). The Fund has

participated in many of the significant constitutional and

statutory voting rights cases in this Court. See, e.g., United

Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977); Thornburg

v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986); Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U.S.

__, 115 L. Ed. 2d 348 (1991); Houston Lawyers Association

v. Attorney General of Texas, 501 U.S.__ , 115 L. Ed. 2d 379

(1991).

Su m m a r y o f A r g u m e n t

Contrary to the opinion of the court below, there is

an extensive, indisputable legal and factual basis supporting

the Louisiana Legislature’s conclusion, following the 1990

census, that compliance with the Voting Rights Act of 1965

required it to fashion a Congressional redistricting plan with

3

two African-American-majority districts. Far from being

pretextual (as the court below suggested), this conclusion is

compelled in light of (a) the state’s long history of official

discrimination against its African-American citizens

(including restrictions upon their exercise of the franchise

and neutralization of their voting strength); (b) the repeated

invalidation, by federal courts or as a result of objections

lodged by the Attorney General of the United States

pursuant to Section 5 of the Act, of redistricting plans that

had been adopted by the legislature because those plans

were found to deny Black voters an equal opportunity to

participate in the political process and to elect candidates of

their choice to a variety of offices; and (c) the continued

existence of white bloc voting against African-American

candidates in Louisiana elections.

Argum ent

Introduction

Amici Curiae are African-American voters of the

State of Louisiana, the Louisiana Legislative Black

Caucus, and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., which represents the individual amici here as

well as voters in North Carolina, Texas, and Georgia2

who have intervened in suits that seek to attack majority-

African-American and -Hispanic-American Congressional

districts in those states. In Louisiana, as in each of these

states, the purposeful .creation of majority-minority

districts arises in a specific historical context which the

court below should have, but did not, adequately take into

account in its decision.

2See Shaw v. Hunt, Nos. 94-923, -924; Lawson y. Vera, Nos. 94-

805, -806, -988; and Johnson v. Miller, Nos. 94-631, -797, -929,

respectively.

4

There are two primary aspects to this context.

First, each of these states has a long and shameful history

of denying minority citizens the right to vote through a

wide variety of devices and means, both "sophisticated and

simple-minded."3 Second, in each of these states it is still

true that large numbers of white voters consistently do

not vote for African-American or other minority

candidates. Such white bloc voting has made it virtually

impossible for minority candidates, whatever their

qualifications or merit, to win an election in a district in

which minority voters are not a majority of the electorate.

The creation of majority-minority districts was

necessary to correct these evils and to provide African

Americans and other minority voters with a fair chance to

elect officeholders of their choice to the legislative body

intended by the Constitution to be representative of the

people as a whole. The post-1990 census Congressional

redistricting plans enacted by the Louisiana legislature

and signed by Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards in

1992 and 1994 are directly responsible for dismantling the

barriers to full participation in the election of members of

Congress that have confronted Louisiana’s African-

American population since the end of Reconstruction.4

'Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268, 275 (1939).

4United States Representative William J. Jefferson of New

Orleans, who has represented Louisiana’s Second Congressional

District since 1991, was elected from a majority-Black Congressional

district created following a federal district court’s finding that the

construction of the New Orleans area districts in the state’s post-1980

census Congressional redistricting plan violated Black voters’ rights

to participate equally in the electoral process and to enjoy an equal

opportunity to elect candidates of their choice to Congress. Major v.

Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983) (three-judge court). Before

Jefferson’s election in 1990, the last African-American member of

Congress from Louisiana was Charles Edmund Nash, who was elected

5

The present case, and others that are now pending

and that will surely follow if this Court permits the result

below to stand, have as their purpose the undoing of our

society’s hard-won progress toward democratic electoral

processes open to all citizens. If successful, the inevitable

effect of these cases would be to turn the clock back to a

day when the voices of minority citizens were unheard in

legislative halls, and when the only avenue open to them

was that of protest and demonstration. That would be the

antithesis of the truly color-blind society to which this

Court has repeatedly and consistently committed itself.

The Uncontrovertible History of

Discrimination Against African Americans in

Louisiana, the Repeated Dilution of their

Voting Strength, and the Persistence of

White Bloc Voting, Amply Justified the

Challenged Districting Plan

The district court properly held that "[ajdhering to

federal anti-discrimination laws and remedying past or

continuing discrimination could constitute compelling

governmental interests [for the adoption of Louisiana’s

post-1990 census Congressional redistricting plans] if the

State could ‘demonstrate a strong basis in evidence for its

conclusion that remedial action was necessary.’" Hays v.

Louisiana, US J.S. App. at 7a (quoting City o f Richmond

v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469, 510 (1989)). The district

court erred, however, in finding that the adoption of Act

in 1874 and served one term. Bruce A. Ragsdale and Joel D. Treese,

Black Americans in Congress, 1870-1989 101-02 (1990).

Congressman Cleo Fields of Baton Rouge, United States

Representative for Louisiana’s Fourth Congressional District, which

was invalidated by the court below, was initially elected in 1992.

6

1 was unjustified under these standards. Instead, in

complete disregard of the record before it and in

contravention of this Court’s decisions,5 the district court

characterized the adoption of Act 1 as "[ujsing the disease

as a cure" and struck down Louisiana’s remedial efforts.

Id. at 124-25.

There was ample justification for the Louisiana

Legislature’s decision to enact a Congressional

apportionment plan with two majority-African-American

districts, in light of the historical and current factual

context in which it acted: pervasive discrimination against

African Americans in Louisiana,6 the state’s repeated

practice of drawing electoral districts that diluted African-

American voting strength, and the continued existence of

bloc voting by whites against African-American

candidates.

A. The History of Egregious Discrimination against

African Americans in Louisiana

For centuries, the African-American population of

Louisiana was subjected to the most blatant, pervasive,

5See, e.g., Johnson v. DeGrandy,___U .S.___ , __ , 129 L. Ed. 2d

775, 796 (1994) (”[T]he lesson of Gingles is that society’s racial and

ethnic cleavages sometimes necessitate majority-minority districts to

ensure equal political and electoral opportunity").

6Cf Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. at 351 ("Evidence of ‘past

discrimination’ . . . is relevant insofar as it impacts adversely on a

minority group’s present opportunities to participate in government");

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297, 1306 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc)

( The district court concluded that . . . removal [of impediments to

registration and the elimination of de jure school segregation] vitiated

the significance of the showing of past discrimination. This

conclusion is untenable, however, precisely because the debilitating

effects of these impediments do persist"), affd sub nom. East Carroll

Parish School Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976).

7

and debilitating forms of discrimination, including a

complete denial of voting rights, solely on the basis of

race.7

1. Discrimination in voting

Neither enslaved nor free persons of color were

allowed to vote in Louisiana until after the Civil War.8

Following the Civil War, African Americans in Louisiana

were afforded their first opportunity to participate in the

electoral process. By 1898, "approximately 44% of all the

registered voters in the State were Negroes," Louisiana v.

United States, 380 U.S. 145, 147 (1965). Inclusion of

African Americans in the political process in Louisiana

was only temporary, however, and by the turn of the

century, they were almost completely excluded from

political participation in the state.9 *

7Even before Louisiana became a state in 1812, racially-based

exclusion from the political process was in place. "[T]he Codes Noir,

from the 1724 Code to Act 83 of the Territorial Legislature of 1806,

disfranchised Negroes." United States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353,

363 (E.D. La. 1963) (three-judge court), ajfd, 380 U.S. 145 (1965).

"The Louisiana Constitution of 1868 [adopted during Reconstruction]

for the first time permitted Negroes to vote. La. Const. 1868, Art.

98." Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 148 n.5 (1965).

’’See Article II, Section 8 of Louisiana Constitution of 1812,

restricting right to vote to "free white male" members of the

population. ”[D]uring the era of slavery . . . the franchise was

conferred exclusively upon white males." Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp.

at 340; see United States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. at 363.

’Between 1896 and 1907 the number of Black registered voters in

Louisiana plummeted from approximately 135,000 to fewer than 1,000

statewide. Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. at 340. In an address to the

Legislature following the 1898 Louisiana Constitutional Convention,

Governor Murphy J. Foster stated:

The white supremacy for which we have so long struggled

. . . is now crystallized into the Constitution as a fundamental

8

Without exception, Louisiana employed every

electoral device ultimately condemned by this Court as

violative of African Americans5 right to equal political

participation. These included the "grandfather" clause,10

the white primary,11 and the "interpretation" test.12 * 12

part and parcel of that organic instrument . . . With this

great principle thus firmly imbedded in the Constitution, and

honestly enforced, there need be no longer any fear as to the

honesty and purity of our future elections.

United States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. at 374.

‘“According to a contemporaneous publication, Louisiana’s

"grandfather" clause was adopted "‘to allow many honorable and

intelligent but illiterate white men to retain the right of suffrage, and

the purpose of the educational or property qualifications] was to

disfranchise the ignorant negroes who had been a menace to the

civilization of the State.”’ United States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. at

373 (iquoting 4 Alcee Fortier, History of Louisiana 235 (1904)).

“ Soon after this Court invalidated Oklahoma’s (and, necessarily,

Louisiana’s) "grandfather" clause in Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S.

347 (1915), Louisiana responded to the decision by, inter alia,

authorizing political parties to conduct racially exclusive primary

elections. Louisiana’s white primary, "which functioned to deny

blacks access to the determinative elections . . . persisted until its

condemnation in Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944)." Major v.

Treen, 574 F. Supp. at 340.

12See generally United States v. Louisiana, supra note 7. Circuit

Judge John Minor Wisdom, writing for the majority of the three-

judge court that originally invalidated Louisiana’s "interpretation" test,

wrote:

A wall stands in Louisiana between registered voters and

unregistered, eligible Negro voters. The wall is the State

constitutional requirement that an applicant for registration

‘understand and give a reasonable interpretation of any

section’ of the Constitutions of Louisiana or of the United

States. It is not the only wall of its kind, but since the

Supreme Court’s demolishment of the white primary, the

interpretation test has been the highest, best-guarded, most

9

A series of other "disenfranchisement techniques

implemented by the state," including poll taxes,

registration purges, literacy tests, citizenship tests, and

laws prohibiting "single shot" voting, "suppressed black

political involvement [in Louisiana] until banned by

Congress in 1965," Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. at 340, or

invalidated by federal courts, see, e.g., Anderson v. Martin,

375 U.S. 399 (1964) (invalidating La. Act 538 of 1960,

which required the race of candidates to be included on

ballots).

In Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965),

this Court unanimously affirmed the decision of a

Louisiana federal court invalidating many of the racially

discriminatory barriers to voter registration that had been

erected by the state. There, the Court noted that an

increase in Black voter registration (following the demise

of the white primary after the Smith v. Allwright decision),

coupled with the advent of school desegregation

(following this Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)), prompted the Louisiana

Legislature to create "a committee which became known

as the ‘Segregation Committee.’" 380 U.S. at 149. The

Louisiana Legislature’s Segregation Committee was

responsible for developing and implementing efforts "to

preserve white supremacy." Id. Among the more

effective means of achieving the goal of "preserv[ation of]

white supremacy" in the political process was the

"interpretation" test, United States v. Louisiana, 225 F.

Supp. at 380-81.13

effective barrier to Negro voting in Louisiana." United

States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. at 355.

13The "interpretation" test "required that an applicant for

registration be able to ‘give a reasonable interpretation’ of any clause

10

In the two decades following this Court’s

invalidation of the white primary, the renewed

administration of the "interpretation" test transformed

Louisiana’s voter registration offices into "‘the front line

of the battle’ to retain a segregated society." United States

v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. at 387. Registrars in 21 of

Louisiana’s 64 parishes discriminated against African-

Americans who attempted to register to vote "not as

isolated or accidental or unpredictable acts of unfairness

by particular individuals, but as a matter o f state policy in

a pattern based on the regular, consistent, predictable

unequal application of the [interpretation] test.” Id. at

381 (emphasis supplied).14

After this Court’s affirmance of the decision

invalidating Louisiana’s racially discriminatory

"interpretation" test and other voter registration practices

in Louisiana v. United States,15 and Congress’ adoption

in the Louisiana Constitution or the Constitution of the United

States." Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. at 148.

14Red River, DeSoto and Rapides Parishes, which are wholly or

partially within District 4 of Act 1, were among the parishes where

the interpretation test was used to thwart Black voter registration

efforts; indeed, Red River Parish was specially identified by the three-

judge court as one of the areas where "[t]he evidence of

discriminatory application of the interpretation test [wa]s especially

well documented and supported by testimony," United States v.

Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. at 381 and n.77; see also, id. at 385 (table

listing Black and white voting age population and registration in those

parishes in 1956 and 1960).

“ Louisiana’s "citizenship test," which required applicants for

registration to pass an "‘objective test of citizenship’" and demonstrate

that they were "‘of good character and . . . [aware of] the duties and

obligations of citizenship," was also challenged in United States v.

Louisiana. The court entered a more limited injunction against use

of the citizenship test than the complete statewide prohibition it

imposed against further use of the interpretation test. See 225 F.

Supp. at 392-98.

11

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, increasingly subtle, but

nevertheless effective, mechanisms for diluting African-

American voting strength and counteracting African

Americans’ increasing access to the ballot surfaced

throughout the state. The use of at-large or multimember

district elections,16 the majority-vote requirement,17 and

other election procedures and devices18 combined with

pervasive racially polarized voting throughout Louisiana

to minimize the voting strength of the recently registered

African-American population in the state.

16See, e.g., Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra note 6 (invalidating

multimember election districts in East Carroll Parish); Parnell v.

Rapides Parish School Bd., 425 F. Supp. 399 (W.D. La. 1976), ajfd in

relevant part, 563 F.2d 180 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 438 U.S. 915

(1978) (same for Rapides Parish). See generally, Richard L.

Engstrom, Stanley A. Halpin, Jr., Jean A. Hill, and Victoria M.

Caridas-Butterworth, Louisiana, in Quiet Revolution in the

South: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act 1965-1990 109-17

(Chandler Davidson and Bernard Grofman, eds., 1994)("Engstrom,

et al.”); U. S. Exh. 9, Hays v. Louisiana, at 10-13 (listing court

decisions and numerous Justice Department Section 5 objections to

changes from single-member to multimember election districts in

Louisiana, as well as to racially discriminatory single-member

redistricting plans adopted by Louisiana jurisdictions in the 1970’s).

llSee Zimmer, 485 F.2d at 1306 (noting that the majority-vote

requirement "has been severely criticized as tending to submerge a

political or racial minority," and holding that it in fact had that result

in East Carroll Parish).

lsSee, e.g., Clark v. Edwards, 725 F. Supp. 285, 301 (M.D. La.

1988) (noting that "[t]he requirement that each judicial candidate

qualify to a specific post or division . . . limitjs] the ability of black

voters to select candidates of their choice. . . . [T]he run-by division

requirement in judicial elections is a functional equivalent [to an anti

single shot voting provision]"), vacated on other grounds sub nom.

Clark v. Roemer, 750 F. Supp. 200 (M.D. La. 1990), modified , 111 F.

Supp. 445 (M.D. La. 1990), vacated, 501 U.S. 1246 (1991), on remand,

111 F. Supp. 471 (M.D. La. 1991), appeal dismissed, 958 F.2d 614 (5th

Cir. 1992).

12

Louisiana’s "long history of de jure and de facto

restrictions on the right of black citizens to register, to

vote, and otherwise participate in the democratic process"

is so notorious that within the past decade, Louisiana

federal courts have "taken judicial notice of that history,"

Clark v. Edwards, supra note 18; see also Chisom v.

Edwards, 690 F. Supp. 1524, 1534 (E.D. La. 1988) (same),

vacated on other grounds, 853 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir.), cert,

denied, 488 U.S. 955 (1988); Citizens for a Better Gretna v.

City of Gretna, 636 F. Supp. 1113, 1116 (E.D. La. 1986)

("The historical record of discrimination in the State of

Louisiana and the Parish of Jefferson is undeniably clear,

and the record suggests it has not ended even now"), affd,

834 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987), cert, denied, 492 U.S. 905

(1989).

2. Discrimination in education and other areas

One federal district court observed in a 1983 case

that the discrimination African-American residents of

Louisiana encountered outside the political arena was as

pervasive and severe as that encountered within the

political realm:

Like other southern states, Louisiana enforced a

policy of racial segregation in public education,

transportation and accommodations. Despite the

Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of

Education . . . local school boards refused to

desegregate in the absence of a federal court

order. . . . A dual university was operated by the

state until 1981, when it was dismantled pursuant

to a consent decree. . . . [and pjublic facilities were

not open to members of both races until the late

1960s.

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. at 341 (citation omitted); see

also Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Comm’n,

13

275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967), affd per curiam, 389

U.S. 571 (1968) (detailing widespread resistance to school

desegregation throughout Louisiana for more than a

decade following the Brown decision, largely facilitated by

a series of legislative enactments designed to evade the

effect of that ruling).19

Testimony before the court below underscores the

Major v. Treen panel’s assessment of the pervasiveness of

state-enforced segregation in Louisiana. One of the more

telling examples of this was the testimony of a white state

Senator about the leadership role that African-American

members of the legislature played in the effort to repeal

state laws that required human blood to be identified

according to the race of the donor, and kept segregated.

Armand J. Brinkhaus (a member of the legislature since

1968) testified that Ernest "Dutch" Morial, who was then

the lone African-American member of the entire

Louisiana legislature, "fought a battle on a bill . . . to

mandate a discontinuance of [racial] labeling [of] blood."

June 22, 1994 Tr., Vol. 4, at 24, 25. According to Senator

Brinkhaus, the bill introduced by then-Representative

19As the Poindexter court summarized:

[F]or a hundred years, the Louisiana legislature has not

deviated from its objective of maintaining segregated schools

for white children. . . . Open legislative defiance of

desegregation orders shifted to subtle forms of circumvention

. . . [b]ut the changes in means reflect no change in legislative

ends.

275 F. Supp. at 845 (emphasis supplied). See also Hall v. St. Helena

Parish School Bd., 417 F.2d 801 (5th Cir.) (holding that 37 Louisiana

school boards, including those for the present Fourth Congressional

District parishes of Ascension, Desoto, Natchitoches, Pointe Coupee,

Rapides, St. Landry, St. Martin and West Baton Rouge were required

to eliminate continued school segregation through some means other

than ineffective "freedom of choice” policies), cert, denied, 396 U.S.

904 (1969).

14

Morial was not enacted in 1968 and did not pass until

"the numbers [of African-American legislators] increased,"

id. at 25.20

In the 1993 evidentiary hearing before the court

below on the constitutionality of Louisiana Act 42 (the

first post-1990 census Congressional redistricting plan

invalidated by the court below), Tulane University history

professor Lawrence Powell testified that "Louisiana was

the only state in which Black illiteracy remained above 70

percent throughout the 19th Century . . . [and] from the

late 1880s until the mid-1920s Louisiana was second only

to Mississippi in lynching." Aug. 19, 1993 Tr. at 55.

3. Continuing impact o f this discrimination

While the enactment and enforcement of civil

rights laws has afforded African Americans some relief

from racial discrimination in Louisiana and elsewhere, as

the district court found in the 1983 Major v. Treen

decision, Louisiana’s long-lived discriminatory practices

have had, unfortunately, similarly long-lived effects:

[T]he residual effects of past discrimination still

impede blacks from registering, voting or seeking

elective office. . . . Blacks in contemporary

Louisiana have less education, subsist under poorer

living conditions and in general occupy a lower

socio-economic status than whites. Though

10Cf Lawrence N. Powell, Read My Liposuction: The Makeover of

David Duke, 203 Ne w REPUBLIC 18 (Oct. 15, 1990) (in a 1990 debate

with United States senatorial campaign opponent Ben Bagert, David

Duke "admitted that he still believes that the blood supply should be

racially segregated"). After the court below invalidated Act 1 and

imposed its own districting plan, David Duke announced his intention

to run for the United States Congress from Louisiana. See Alice

Love, David Duke Wants to Run for New Cajun House Seat, 39 Roll

Call, August 4, 1994, at 1.

15

frequently more subtle, employment discrimination

endures. These factors are the legacy of historical

discrimination in the areas of education,

employment and housing. . . . A sense of futility

engendered by the pervasiveness of prior

discrimination, both public and private, is

perceived as discouraging blacks from entering into

the governmental process.

574 F. Supp. at 341. More recently, Chief Judge John V.

Parker of the Middle District of Louisiana reached a

similar conclusion and rejected the state defendants’

argument that official acts of discrimination which

occurred before the enactment of the Voting Rights Act

in 1965 are irrelevant to determining whether a

challenged electoral practice discriminates against

African-American voters. Chief Judge Parker held that

"[t]he entire history of discrimination must be considered

although . . . there have been improvements made by

virtue of the Voting Rights Act of 1965." Clark v.

Edwards, 725 F. Supp. at 296 (emphasis supplied). Judge

Parker found that Louisiana’s "‘history of racial

discrimination, both de jure and de facto, continues to

have an adverse effect of the abilities of its black residents

to participate fully in the electoral process.’" Id. (quoting

Major v. Treen).

The court below concluded that the Louisiana

Legislature lacked any basis for believing that if it failed

to adopt a Congressional districting plan containing two

districts that would afford African Americans an equal

opportunity to elect candidates of their choice, the

Attorney General would interpose a Section 5 objection

or African-American voters would bring a successful

Section 2 suit challenging the plan. The court’s

conclusion is simply untenable in light of the extensive

history and continuing adverse impact of decades of state-

16

sponsored discrimination against the African-American

citizens of the State of Louisiana.

B. The State’s Consistent Dilution of African-American

Voting Strength in the Drawing o f Districts

In every post-census redistricting undertaken by the

Louisiana Legislature since the adoption of the Voting

Rights Act, either the federal courts (acting to enforce the

provisions of the United States Constitution or of the

Voting Rights Act), or the Justice Department (acting

pursuant to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act), have

rejected at least one statewide redistricting plan adopted

by the legislature on the ground that the proposed plan

diluted African-American voting strength.

In 1971, for example, a Louisiana federal court

"whole-heartedly concurred with the findings of the

Attorney General [under Section 5]" that the statewide

legislative redistricting plan adopted by the Louisiana

Legislature was racially discriminatory and held that it

would have invalidated the plan for similar reasons, even

if the Attorney General had not objected to its

implementation. Bussie v. Governor of Louisiana, 333 F.

Supp. 452, 454 (E.D. La. 1971), aff’d and modified, 457

F.2d 796 (5th Cir. 1971) (per curiam), vacated sub nom.

Taylor v. McKeithen, 407 U.S. 191 (1972), on remand, 499

F.2d 893 (5th Cir. 1974). The Bussie court noted that

"[djuring the Twentieth Century only two [Njegroes . . .

sat in the Louisiana Legislature, and even they did not sit

at the same time. One succeeded the other." 333 F.

Supp. at 457; see also Hays 1994 Tr., Vol. 4, at 24-25

(Brinkhaus testimony discussing presence of only one

African-American in state legislature in 1968). Aiter a

decade of elections under the redistricting plan adopted

by the legislature after the Bussie decision, 10 Louisiana

17

House districts and 2 Louisiana Senate districts had

elected African-American candidates. Engstrom, et al., at

111; see also U.S. Exh. 9 at 12-13 11 19.

The state legislative redistricting plan adopted after

the 1980 census reduced the number of Black-majority

House districts from 17 to 14. The plan could not be

implemented because of the Section 5 objection

interposed by the Attorney General to the

implementation of this retrogressive plan. Id. at 14-15, 11

23.

The New Orleans area districts in the

Congressional redistricting plan adopted by the Louisiana

legislature following the 1980 census were successfully

challenged by African-American voters in Major v.

Treen21 and was replaced ultimately by a plan containing

one majority-Black Congressional district. As set forth

fully in the district court opinion in that case, the plan

afforded African Americans less opportunity than whites

to participate in the electoral process and to elect

candidates of their choice, in violation of Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended. In reaching its

conclusion that the construction of the First and Second

Districts in the plan violated Section 2, the court

considered "as . . . one aspect of the totality of

circumstances, the evidence that opposition to the

creation of a majority black district was responsible, to a

significant extent," for the adoption of the plan. 574 F.

Supp. at 355 n.39.22

21Bemadine St. Cyr (amicus herein) was one of the plaintiffs in

the Major v. Treen case.

22The district court found that Governor Treen opposed the

adoption of the plan originally supported by the legislature at least

partially for racial reasons: "He denounced any legislative scheme

which intentionally drew boundary lines so as to consolidate a

18

The Major court also noted the extremely irregular

procedure used to adopt the plan:

Both houses of the Louisiana Legislature . . .

approved reapportionment bills [that provided for

the creation of a majority-Black district in New

Orleans and its environs]. . . . Upon learning of the

action of the legislature, Governor Treen

announced his intention to veto the . . . [plan] if

finally passed. . . . A sufficient number of

legislators changed their position in response to

the threatened veto to assure the demise of the

. . . [plan].

574 F. Supp. at 333. The Legislature then delayed

appointment of a conference committee to consider

alternatives to the abandoned reapportionment bill and

instead, an all-white group of legislators and other

"‘interested’ parties" met privately "in the sub-basement of

the State Capitol" to develop a new redistricting plan. Id.

at 334. The predictable outcome of the legislators’ secret

meeting was the abandonment of the concept of

developing a redistricting plan containing a majority-Black

district, and the substitution of the plan ultimately

majority of one race within a single district. He . . . characterized

[the creation of a majority-Black New Orleans-based district] as an

attempt by the Louisiana Legislature to enact into law the discredited

idea of proportional representation. . . . [However, the Governor’s]

concerns were restricted to the aggregation of blacks within one

district; the coalescence of whites was not regarded as ominous so

long as [the white incumbent congressman’s] chances for re-election

were maximized. . . . [Consequently, an Orleans Parish-based] district

with 55% white population encountered no objection [from the

Governor].” 574 F.Supp. at 333 (emphasis supplied). Cf US J.S.

App. at lOa-lla (objecting to creation of 55%-Black District 4 of Act

1, while adopting court-ordered plan with far more heavily

concentrated white populations in every district except the Major v.

Treen remedial district).

19

adopted by the Louisiana legislature ("Act 20"), which did

not contain a single majority-Black district. Id. at 334-35.

After Governor Treen expressed his approval of Act 20,

an all-white conference committee, consisting of 3 state

Senators (Hudson, Nunez and O’Keefe) and 3 state

Representatives (Alario, Bruneau and Scott) voted 4 to 2

in favor of referring Act 20 to the full legislature for

approval. Id. at 336-37.23 Assessing the procedure

which yielded the adoption of Act 20, the district court

wrote:

[R]ather than utilizing the routine mechanism of

the conference committee following the House’s

withdrawal of its approval of the . . . [original

redistricting] plan, the legislative leaders convened

a private meeting. . . . Because all were aware that

the conflicting objectives of the Governor and

black legislators with respect to a black majority

district could not be harmonized, the latter were

deliberately excluded from the final decision-making

process.

574 F. Supp. at 352 (emphasis supplied).* 24

“ The district court found that Governor Treen’s opposition to the

first legislatively supported plan was "predicated in significant part on

[the plan’s] delineation of a majority black district centered in

Orleans Parish." 574 F. Supp. at 334. See also infra p. 20, text at

n.25.

24While Governor Treen explained his opposition to the creation

of a majority-Black congressional district as the product, inter alia, of

his "concern . . . [about] racial polarization," 574 F. Supp. at 333, and

his belief that African-American voting strength is actually enhanced

in so-called influence districts, rather than in majority-Black districts,

his early political record evinced minimal "concern" about fostering

racial polarization in the electorate or enhancing African-American

voting strength. The 1978 Almanac of American Politics stated

that in 1964 and 1968 campaigns against New Orleans Congressman

20

It is striking that contemporary opposition to Act

1 (and its second majority-African-American

Congressional district) sounded the same themes as in

1980. For example, state Representative Charles

Bruneau, who criticized the creation of Louisiana’s first

majority-Black Congressional district in the 1980’s on the

ground that New Orleans "already ha[d] a nigger mayor,

and [it] d[id]n’t need another nigger bigshot,"25 also

opposed the adoption of Act 1. Apr. 18, 1994 Louisiana

House of Representatives and Governmental Affairs

Committee Hearing Minutes at 37. In response to

Speaker Pro Tern Copelin’s argument that District 4 of

Act 1 essentially replicated the former Eighth

Congressional District, once represented by (white)

Congressman Gillis Long, Representative Bruneau

replied, "Of course, Mr. Copelin, as we say, that was then

and this is now." Id. at 46. Cf. US J.S. App. at 4a

("[VJarious witnesses asserted that District Four was

inspired by ‘the old Eighth’ district thereby satisfying the

concept of ‘traditional’ districting principles. . . . The ‘old

Eighth’ . . . was crafted for the purpose of ensuring the

reelection of Congressman Gillis Long . . . [whereas n]ew

District Four was drafted with the specific intent of

ensuring a second majority-minority Congressional

district").

Hale Boggs, "Treen’s big issue was Civil Rights: in 1964 he charged

that Boggs secretly favored the Civil Rights Act of that year; in 1968

he used Boggs’ support of the Civil Rights Acts of 1965 and 1966 [as

campaign issues]."

25See Nomination of William Bradford Reynolds to be Associate

Attorney General o f the United States; Hearings Before the Senate

Committee on the Judiciary, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. 440 (1985) (reprinting

analysis of Section 5 submission prepared by Robert N. Kwan,

Attorney, Voting Section, Civil Rights Division, United States

Department of Justice).

21

The United States Attorney General objected

under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act to the

implementation of both the Louisiana House and

Louisiana Senate redistricting plans adopted by the

Legislature after the 1990 census, U.S. Exh. 9, at 19, If

29. Also in 1991, shortly before undertaking

Congressional redistricting, the legislature reapportioned

the statewide Board of Elementary and Secondaiy

Education ("BESE") based on the 1990 census. There are

eight elected members of the BESE. The legislature

initially devised a plan which had only one majority-

African-American BESE district, which prompted an

objection under Section 5 by the Attorney General. Id.26

In sum, after this Court affirmed orders striking

down direct and indirect restrictions upon African-

American suffrage in Louisiana, as described in the

preceding section, the Legislature repeatedly acted to

fashion state and national legislative districts that would

eliminate or minimize African-American voting strength.

In a consistent pattern that continued virtually up to the

very moment that the Legislature redrew the state’s

Congressional districts after the 1990 census, those

dilutive plans were struck down by the federal courts or

were denied preclearance under Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act by the Attorney General of the United States.

The Legislature thus had more than enough evidence to

support its conclusion that drawing yet another plan which

diluted minority voting strength would be rejected by the

Justice Department and/or challenged successfully in

court.

26Ultimately, an eight-member redistricting plan for the BESE

which included two Black-majority districts was adopted by the

Louisiana Legislature and precleared under Section 5.

22

The Legislature also knew that in each instance,

the remedy for its dilutive districting had involved the

creation of majority-Black electoral districts to afford

African-Americans the opportunity to elect candidates of

their choice, and that implementation of the remedies had

mitigated the persistent underrepresentation of African

Americans in Louisiana’s state legislative delegations and

on the BESE.

On these facts there is simply no support

whatsoever for the "finding" by the court below that "the

State did not have a basis in law or fact to believe that

the Voting Rights Act required the creation of two

majority-minority districts," US J.S. App. at 9a.

Moreover, the evidence demonstrates that the Legislature

was well aware that a "Red River" Congressional district

markedly similar to the ultimate Fourth District in Act 1

had been maintained through the 1970’s and 1980’s.

Refusal to follow the same districting principles after the

1990 census so as to create a second majority-Black

district would almost certainly have resulted in either a

Section 5 objection or a court challenge by the state’s

African-American voters. For these reasons, the holding

by the court below that reference to the "old eighth"

district was either a "pretext" for the Legislature’s "specific

[and unlawful] intent of ensuring a second majority-

minority Congressional district," US J.S. App. at 5a, or

was irrelevant because "the old eighth district was never

challenged on constitutionality," id. at 18a (Shaw, J.,

concurring), is baseless.

C. The Persistence of Racially Polarized Voting

There is extensive evidence in the record of the

persistent phenomenon of racially polarized voting in

Louisiana elections, and of the degree to which white bloc

23

voting, combined with other features of Louisiana’s

election system, continues to impede African-American

political participation and limit the opportunity for

African Americans to elect candidates of their choice in

the state.

Within the past decade, there have been repeated

judicial findings that racially polarized voting continues to

occur with regularity in Louisiana. For example, in a

recent Section 2 case challenging some of Louisiana’s

judicial election districts, the district court observed that

"[t]he expert witnesses of both sides . . . agreed that there

is widespread racial polarization in voting in Louisiana,"

Clark v. Edwards, 725 F. Supp. at 296 (emphasis

supplied). The Clark court also noted that "the fact that

in 54 [elections analyzed] . . . white voters never voted

even a plurality for the black candidate strongly indicates

racial polarization of white voters." Id. at 297.27 28 As a

result of the compelling evidence of racially polarized

voting, as well as other evidence presented by plaintiffs,

the district court

conclude[d] that across Louisiana . . . there is

consistent racial polarization in voting . . . . [and

the court is] convinced . . . that the white majority

has . . . repeatedly [voted sufficiently as a bloc to

enable it, in the absence of special circumstances,

usually to defeat the minority’s preferred

candidate] in Louisiana judicial elections.

Id. at 298-99.?s

21See also id. at 304 (finding a "state-wide pattern of racially

polarized voting which . . . is ‘pronounced and persistent’") (quoting

plaintiffs’ expert Dr. Richard Engstrom).

28The court also held that "both subtle and overt racial appeals

. . . still do appear in some white-black campaigns." 725 F. Supp. at

299.

24

The State of Louisiana and the United States

proffered similar evidence to the court below in defense

of Louisiana Act 1. In his 1993 testimony before the

lower court, Dr. Richard Engstrom stated: "[Ajcross

Louisiana, voting is racially polarized. . . . [I]t does not

begin at one parish line and end at another parish line.

It’s a pervasive phenomenon within the State." Aug. 19,

1993 Tr. 73. Dr. Engstrom also testified concerning the

many "inexorable zero[es]"29 among the elected branches

of government in Louisiana: "[Tjhere are no Black

statewide elected officials in Louisiana . . . [ejected from

a statewide majority white electorate. . . . There have

been no Blacks elected to Congress from Louisiana in this

century in a district with a majority white voter

registration . . . [and tjhere have been no African

Americans elected to the state legislature in Louisiana

. . . this century from a district. . . in which a majority of

the registered voters were white." Id. at 79-80.

The decision below does not address any of this

evidence and instead fast-forwards to a color-blind society

which unfortunately is far from the present-day reality of

Louisiana.30

29See International Bhd. o f Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324,

342 n.23 (1977).

30For example, the court below wrote: ”[W]e refuse to accept the

explanation [for the configuration of District 4 in Act 1] that citizen

response to issues such as education, crime and health care is driven

by skin pigmentation." US J.S. App. at 10a. The difficulty with this

analysis is that it permits no consideration in the redistricting process

of common political interests which many African Americans share

-- including because they have had the common experience of

suffering from official Louisiana policies of racial discrimination -

even while recognizing that members of numerous other racial,

ethnic, and religious groups may share common interests. Incredibly,

the court suggests, as one basis for its conclusion that Act 1 is

constitutionally deficient, that it breaks down barriers between such

25

D. The "Totality o f the Circumstances"

This Court recently emphasized the importance, in

deciding claims under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

of comprehensively assessing all of the facts. "In

modifying § 2 [in 1982], Congress . . . endorsed our view

in White v. Regester that ‘whether the political processes

are "equally open" [to minority voters] depends upon a

searching practical evaluation of the "past and present

reality,"’" Johnson v. DeGrandy, supra note 5, 129 L. Ed.

2d at 795 (citations omitted). Unlike the thorough

analysis of the proof required by this Court’s previous

decisions and reflected in the Clark decisions, the ruling

below cavalierly dismisses the evidence and misapplies the

decisions of this Court in an effort to avoid careful

consideration of what the record shows. The court below

wrote:

Defendants elicited testimony that the sordid

history of unconstitutional treatment of black

citizens in Louisiana prompted the State to tinker

with district lines in order to ensure minority

control at the polls.. . . What the defense failed to

establish is where the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and

the Voting Rights Act of 1965 have failed to

accomplish what the State now sets out to do.

Without concrete evidence of the lingering effects

of past discrimination or continuing legal prejudice

in voting laws and procedures, coupled with

specific remedies, we cannot agree th a t. . . racially

groups. See US J.S. App. at 17a ("District 4 includes North Louisiana

English-Scotch-Irish, mainline Protestants, South Louisiana French-

Spanish-German Roman Catholics, traditional rural black Protestants

and Creoles. The district encompasses North, Central and South

Louisiana, each of which has its own unique identity, interests,

culture, and history") (Shaw, J., concurring).

26

configured voting districts [are] warranted. Croson

and Bakke dictate this result.

US J.S. App. at 10a. The court below does not explain

how the continued debilitating effects of prior

discrimination that were identified by the Clark court just

four years ago,31 long after passage of the 1964 and 1965

federal laws to which it refers, have been eliminated in a

state whose redistricting efforts immediately prior to the

measure attacked in this litigation prompted objections

from the Attorney General. Nor does it identify any

evidence presented by the appellees indicating that racial

disparities attributable to prior discrimination have

vanished from Louisiana. (There was none.) Contrary to

the suggestion in the opinion below, the decisions of this

Court do not "dictate" the result reached in this case.

Unlike in City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S.

469 (1989) and Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S.

265 (1978), the federal courts have made repeated

findings of racial discrimination, and of its continuing

effects, that fully support the Louisiana legislature’s

action.

Writing just two years before the last decennial

census, Chief Judge Parker observed: "If all of us voted

without regard to race, the problem would be solved and

there would be no claim of a . . . [Voting Rights Act]

violation. That day does not yet seem to have arrived [in

Louisiana]." Clark, 725 F. Supp. at 300. The Louisiana

31,'[H]istorical de jure and de facto restrictions on minority voting

. . . [and] socio-economic factors" which reflected historic

discrimination and the disparate economic and educational status of

Black and white residents of Louisiana "have not been shown to have

dissipated . . . [and] "still operate to discourage more blacks than

whites from full [political] participation." Clark v. Roemer, 111 F.

Supp. 471, 478 (M.D. La. 1991), appeal dismissed, 958 F.2d 614 (5th

Cir. 1992).

27

legislature embarked on the task of developing a

Congressional redistricting plan for the state only a few

years later. It defies common sense and conflicts with the

extensive evidence presented by the State and the United

States below to conclude, as the district court did, that

race has so quickly become an inconsequential factor or

irrelevant matter to Louisiana’s body politic.

Moreover, in light of the repeated violations of the

voting rights of the State’s minority citizens, it is patently

unfair to assign responsibility for the race-consciousness

of the post-1990 census Congressional redistricting to the

state’s very recent efforts to comply with the demands of

the Voting Rights Act by enacting a Congressional

redistricting plan that would fairly recognize African-

American voting strength in the state and would not

operate to minimize or cancel out the votes of nearly one-

third of the population of the state. Finally, as we have

earlier noted, the conclusion of the court below (that the

Louisiana Legislature lacked any basis for believing that

if it failed to adopt a Congressional districting plan

containing two districts that would afford African

Americans an equal opportunity to elect candidates of

their choice, the Attorney General would interpose a

Section 5 objection or African-American voters would

bring a successful Section 2 suit challenging the plan) is

simply untenable in light of the extensive history and

continuing adverse impact of decades of state-sponsored

discrimination against the African-American citizens of

the State of Louisiana.

The decision below is particularly troubling

because, as Dr. Richard Engstrom said to the lower court,

the Louisiana Legislature’s efforts to adopt a

Congressional redistricting plan that complied fully with

the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and to take a prophylactic

approach to congressional redistricting, attempting to

28

accommodate the concerns of the state’s African-

American as well as its white citizens, "was a real

aberration. . . . We have a history of not complying with

the Voting Rights Act until forced to either by the Justice

Department or by federal courts such as in Major versus

Treen." Aug. 19, 1993 Tr. 100. The state of Louisiana

should not be stymied in this earnest and long overdue

overture towards remedying "the sordid history of

unconstitutional treatment of black citizens in Louisiana,"

US J.S. App. at 9a.

C o n c l u s io n

The history of Louisiana is duplicated in most of

the states that have had a background of discrimination in

voting. In redistricting after the 1990 census, public

officials in many instances made good faith efforts to

comply with the interpretations of the statutory and

constitutional requirements for reapportionment

announced by this Court and the lower federal courts. In

jurisdictions with a history of discrimination in voting and

other areas, where minority voters were politically

cohesive, and where there were established patterns of

racially polarized voting that made it almost impossible

for a submerged minority to be represented, officials

shouldered their legal obligation to create districts that

gave minority voters equal access to the political process

and a fair opportunity to elect representatives of their

choice.

The results of this effort were of great benefit not

only to minority communities, but to the body politic as

a whole. For the first time since the end of

Reconstruction the delegations to the United States

House of Representatives (from the affected states) were

indeed representative. Legislative bodies at the local and

29

state levels similarly encompassed the interests of all of

the electorate.

In short, governmental officials and their

constituents relied on the holdings of this Court when

they made the difficult decisions inherent in the

redistricting process. They sought to follow the law as

expressed in those decisions and the innumerable

decisions of the lower courts enforcing them.32

Unfortunately, in a number of instances litigants and

lower federal courts have misread this Court’s decision in

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U .S.__ , 125 L. Ed. 2d 511 (1993) as

somehow undermining or even overruling sub silentio

decisions such as Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)

that have given meaning and substance to the Voting

Rights Act. This Court should make clear that the

obligations of that Act as interpreted by the courts remain

as clear as before. To do otherwise would result in:

. . . serious inequity to those who have relied upon

them [and] significant damage to the stability of

the society governed by [their] rule . . . .

Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 U .S.__ , 120 L. Ed. 2d

674, 700 (1992).

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the court

below should be reversed.

32Cf. Hon. George C. Pratt, Symposium, The Supreme Court and

Local Government Law, The 1992 Term, 10 TOURO L. Rev. 295, 454-

55 (1994) (discussing general acceptance of legal framework in New

York City and New York state redistricting after the 1990 census,

based upon Judge Pratt’s experience on panels hearing such cases).

30

Respectfully submitted,

Ba r b a r a R . A r n w in e

T h o m a s J. H e n d e r so n

B r e n d a W r ig h t

J. G e r a l d H e b e r t

La w y e r s’ C o m m it t e e

f o r C iv il R ig h ts

u n d e r La w

1450 G Street, NW,

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 662-8600

R o b e r t B. M cD u f f

771 North Congress Street

Jackson, MS 39202

(601) 969-0802

Attorneys for Amicus

Curiae the Louisiana

Legislative Black Caucus

E l a in e R . J o n es

D ir e c t o r -C o u n sel

Th e o d o r e M. Sh a w

N o r m a n J. Ch a c h k in

Ch a r l es St e p h e n R a lst o n

"■Ja c q u e l in e A. B e r r ie n

N a a cp L e g a l D e f e n s e a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street,

16th floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

* Counsel of Record

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

Bemadine St. Cyr, Donald

Thibodeax, Patrick Fontenot,

Janice Frazier, and the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

January 30, 1995