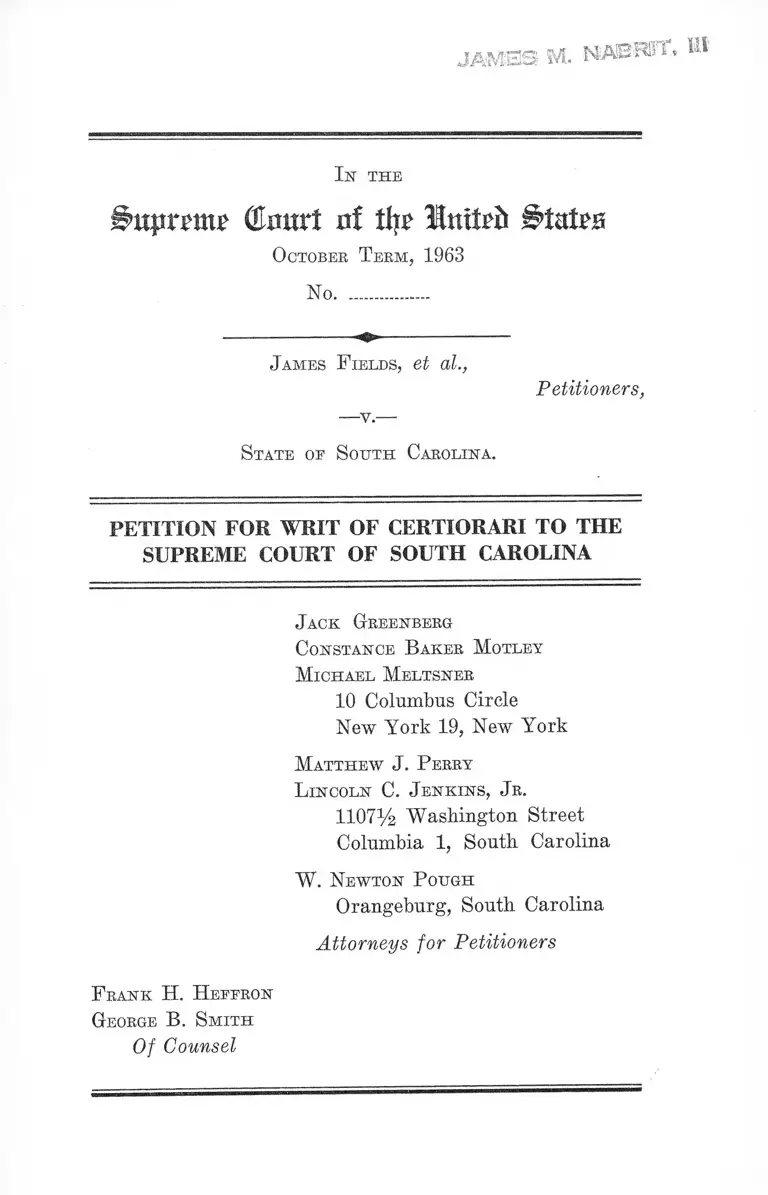

Fields v. South Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Fields v. South Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina, 1963. 5ba73ea8-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e8a279b8-a447-4c92-9ef6-d078be62fe1c/fields-v-south-carolina-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-south-carolina. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

JAMES M. NAEKlinr, HI

I n THE

§>upmnT (Emtrt nf % Itttted States

O ctober T erm , 1963

No..................

J ames F ields, et al.,

Petitioners,

—y.—

S tate of S ou th Carolina .

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

J ack Greenberg

C onstance B aker M otley

M ich ael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

M atth e w J . P erry

L incoln C. J e n k in s , Jr.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia 1, South Carolina

W . N ew ton P ough

Orangeburg, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

F ran k H . H eeeron

G eorge B . S m it h

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below .......................................... 1

Jurisdiction ................... 2

Questions Presented ........................................................... 2

Constitutional Provision Involved .................................- 3

Statement .............................................................................. 3

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below .................................................................................... 10

A rgu m en t ............... 13

I. Conviction of Generalized Common Law Breach

of the Peace for Peaceful and Orderly Speech

and Assembly Opposed to Racial Segregation

Denied Petitioners Due Process of Law Secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment ................ 13

II. Petitioners’ Convictions on Warrants Charging

That Their Conduct “ . . . Caused Fear and

Tending to Incite a Riot or Other Disorderly

Conduct or Cause Serious Trouble” Violate the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment in That the Judgments Rest on No Evi

dence of Guilt ........................................................... 17

C o n c l u s io n .................................... -................................. —- 20

11

T able op C ases

page

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 307 .......................16,17

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ......................................... 16

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 299 ...........2, 3,13,14,

15,16,17,18,19

Feiner v. New York, 300 N. Y. 391, 91 N. E. 2d 319,

affirmed, 340 XL S. 315............................................ 12,13,15

Fields v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 522 ...................1, 3,13

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 II. S. 157.................................17,19

Lombard v. Louisiana,------U. S . ------- , 83 S. C t .------ ,

10 L. ed. 2d 338 .............................................................. 15

Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877 (8th Cir. 1947), cert.

den. 332 U. S. 851 .......... ............... .................................. 16

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ........................... 17

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154................................... 19

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ............................... 16

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 ........................... 19

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 8 8 .......... ........................ 17

Wright v. Georgia, —— IJ. S. ------ , 83 S. Ct. ----- ,

10 L. ed. 2d 349 ............................................................ 16

Ill

I n d e x to A ppendix

page

Order of the Supreme Court of South Carolina on

Remand .............................................................................. la

Order of the Orangeburg County Court, State v. Fields 3a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, State

v. Fields ............................................................................ 6a

Order of the Orangeburg County Court, State v. Gil

christ .................................................................................. 7a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, State

v. Gilchrist ...................................................................... 9a

Order of the Orangeburg County Court, State v.

Graham .... 10a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, State

v. Graham ....................................... 12a

Order of the Orangeburg County Court, State v.

Witherspoon ........................................................ 13a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, State

v. Witherspoon .... ............................................................ 15a

Order of the Orangeburg County Court, State v. Heat-

ley ............................-......................................................... 16a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, State

v. Heatley .......................................................................... 17a

Order of the Orangeburg County Court, State v.

J. Brown ............................................................................ 18a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, State

v. J. Brown ............. 19a

Order of the Orangeburg County Court, State v.

Davenport ........................................................................ 20a

IV

PAGE

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, State

v. Davenport .................................................................... 21a

Order of the Orangeburg County Court, State v.

I. Brown ............................................................................ 22a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, State

v. I. Brown ......................................................... -........... 31a

I n t h e

(flmvt of tin Inttefr BUUs.

O ctober T erm , 1963

No..................

J ames F ields, et al.,

-v.

Petitioners,

S tate of S outh Carolina ,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, en

tered May 14, 1963, in State v. James Fields, et al.; State

v. Bobbie J. Gilchrist, et al.; State v. Marie Graham, et al.;

State v. Eula M. Witherspoon, et al.; State v. Alvin Eeatley,

et al.; State v. Joseph C. Brown, et al.; State v. Frances

E. Davenport, et al.

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina on

remand from this Court is unreported and appears in the

appendix, infra pp. la-2a.

The opinions of the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

constituting final judgments vacated and remanded by this

Court, Fields v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 522, are reported

at 126 S. E. 2d 6, 7, 8, 9 (1962) and appear in the appendix

(Fields 6a; Gilchrist 9a; Graham 12a; Witherspoon 15a;

Heatley 17a; J. Brown 19a; Davenport 21a). The opinions

2

of the Orangeburg County Court are unreported and appear

in the appendix (Fields 3a; Gilchrist 7a; Graham 10a;

Witherspoon 13a; Heatley 16a; J. Brown 18a; Davenport

20a).

The opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina and

the opinion of the Orangeburg County Court in State v.

Irene Brown, et al., 126 S. E. 2d 1 (1962) a companion

case, cited as controlling authority for the judgment in peti

tioners’ cases, appear in the appendix, infra pp. 22a-39a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

of which review is sought was entered May 14, 1963, infra

pp. la-2a.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U. S. C. §1257(3), petitioners having asserted below and

asserting here, deprivation of rights, privileges, and im

munities secured by the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

Whether petitioners were denied due process of law se

cured by the Fourteenth Amendment:

(1) when convicted of generalized, vague common-law

breach of the peace, for having engaged in peaceful and

orderly speech and assembly, which allegedly produced

community tension and minor traffic problems, on records

revealing far less likelihood of public disturbance than

those in Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 IT. S. 229.

(2) when so convicted on warrants charging that their

peaceful and orderly walks which expressed ojoposition to

racial segregation and suppression of speech in Orange-

3

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

March 18, 1963, this Court vacated the judgment of the

Supreme Court of South Carolina in these cases, Fields v.

South Carolina, 372 U. S. 522, and directed “ that this cause

be remanded to the Supreme Court of the State of South

Carolina for consideration in light of Edwards v. South

Carolina, 372 U. S. 229.” May 14, 1963, the Supreme Court

of South Carolina filed an order stating “ . . . we have con

sidered this cause in light of Edwards v. South Carolina

and adhere to and affirm the judgment of this court ren

dered on June 6, 1962 ------ S. C. ------ , 126 S. E. 2d 6, for

the reasons stated in our opinion in State v. Brown, 240

S. C. 357, 126 S. E. 2d 1” , infra p. 2a.

Petitioners, three hundred seventy-three Negro stu

dents, were tried in seven separate trials from March 19,

1960 to May 7, 1960. March 15,1960, petitioners along with

other students from the Orangeburg area, began to walk

in four separate groups toward the downtown area of

Orangeburg, South Carolina to demonstrate dissatisfaction

with racial segregation and “ second-class citizenship” in

the city and state (Heatley 103-04; Gilchrist 73; Fields 127;

Witherspoon 103).* Three hundred eighty-eight students

were arrested and charged with common-law breach of the

peace (Fields 102; Gilchrist 102; Graham 1-2; Witherspoon

* Seven trials resulted in seven separate records. Each record is

designated by the first named defendant.

burg, “ caused fear” , “ tended[ed] to incite a riot or other

disorderly conduct” , and “ cause [d] serious trouble” , on rec

ords barren of such evidence.

4

1-2; Heatley 1-2; J. Brown 1-2; Davenport 1-2). All were

convicted in the Magistrate’s Court of the County of

Orangeburg, sitting without a jury, and sentenced to fines

of fifty ($50.00) dollars or 30 days in prison (Fields 137;

Gilchrist 91; Graham 7; Witherspoon 132; Heatley 123; J.

Brown 6; Davenport 7).

On appeal to the First Judicial Circuit of South Carolina

and later to the Supreme Court of South Carolina, the cases

were consolidated for argument and the convictions af

firmed. Identical constitutional and state law questions

were raised in each case. In a companion case, State v.

Irene Brown, infra pp. 22a-39a, a jury trial in the Magis

trate’s Court resulted in the conviction of fifteen students

for common-law breach of the peace. This conviction was re

versed, however, by the Supreme Court of South Carolina

on the ground that the right to examine prospective jurors

on the voir dire had been denied by the trial court.

It was stipulated below that the records in the cases of

J. Brown, et al., Davenport, et al., and Graham, et al.,

would be the same as the record in Heatley, et al. (J. Brown

5; Davenport 5; Graham 5).

The students were charged on warrants alleging that they

“ did commit breach of the peace by unlawfully and

willfully congregating and marching in the City of

Orangeburg, said County, and did approach what is

known as the business section of the City of Orange

burg, the groups being headed by a number of parties

who refused to stop and return to the colleges upon the

request of Chief of Police Hall and other officers in

the City of Orangeburg, thereby disturbing the peace

and tranquility of the normal traffic on the sidewalks

as well as the streets in the City of Orangeburg, which

caused fear and tending to incite a riot or other dis

5

orderly conduct or cause serious trouble, thereby com

mitting breach of the peace, against the form of the

statute in such case made and provided, and against the

peace and dignity of the State.”

(Fields 1-2; Gilchrist 2; Graham 2; Heatley 2; Wither

spoon 2; J. Brown 2; Davenport 2.)

Four groups of students were arrested. For convenience,

the circumstances of each set of arrests are set forth sepa

rately. Facts in common are set forth, infra p. 9.

The Amelia Street Groups

First Group

About 12 noon, March 15, 1960, seventy-five to one hun

dred Negro students walked in completely orderly fashion

(Witherspoon 8, 18, 21, 119; Fields 58, 62, 63, 64, 105, 115;

Gilchrist 28, 29; Heatley 8) on Amelia Street (Heatley 7),

on the sidewalk, two or three abreast. They intended to

protest racial discrimination in the city and state and to

stimulate public discussion of their grievances at the Pub

lic Square. (Gilchrist 64-65; Heatley 92-93; Witherspoon

116, 123, 127; Fields 116.) Before reaching the Square,

they were stopped by two officers one of whom asked for

the spokesman (Heatley 7). At an officer’s request, the

spokesman asked the group to disperse. WThen no one

moved, the officer asked them himself (Heatley 7). Some

students did not hear this request (Gilchrist 71; Wither

spoon 111-112). When the group still did not move all were

placed under arrest (Heatley 7). The reason for the ar

rest was that they were “ demonstrating without a permit”

(Heatley 7).

Another officer testified that due “ to the tension that

was in town” and “ the tranquility of the normal flow of

6

traffic” it was better that the students not be allowed to

continue to the Public Square (Heatley 65). But neither

he nor the other officers specified any present disorder or

particular threat of disorder as reasons for the arrest.

The police admitted “ everybody” was peaceful and orderly

(Heatley 87). No vehicular traffic was blocked (Fields 64,

115; Gilchrist 29; Witherspoon 21, 90,118,119). Pedestrian

traffic was light (Gilchrist 29) and the “ few” pedestrians

were not inconvenienced (Gilchrist 29; Fields 63, 64;

Witherspoon 119, 120). No crowd appeared and although

a few onlookers appeared in yards adjacent to the opposite

sidewalk the police noticed nothing special about them

(Fields 63, 65,105,106; Gilchrist 29).

Second Group

The second Amelia Street group was proceeding just be

hind the first when stopped by the same two officers. The

second group numbered about fifty to seventy-five students

(Gilchrist 27). The circumstances of their arrest were the

same as the first group’s (Gilchrist 24; Heatley 9-10).

Russell Street Group

The same day, March 15, 1960, two groups of students,

numbering three to four hundred (Gilchrist 9), proceeded

on Russell Street in the direction of the downtown area

(Gilchrist 8). They were stopped by officers and ordered to

disperse (Gilchrist 7). When they refused, fire hoses were

turned on them and tear gas thrown (Heatley 34; Fields

20, 22). Police had summoned the fire truck before they

went to meet the students (Fields 41). Only four of Russell

Street students were arrested (Gilchrist 8, 9).

7

Traffic was tied up (Gilchrist 9) by fire hoses strung

across the street (Fields 43). But no traffic was blocked

before the police stopped the students (Gilchrist 14) and

the fire hoses were strung out (Fields 43, 47).

The students themselves remained on the sidewalks (Gil

christ 14). The Chief of Police testified they used the en

tire sidewalks but he did not see anyone forced to walk

into the street or prevented from using the sidewalk (Fields

45, 47; Gilchrist 13-14). He said that the reason for the

arrests was that the students had been told not to demon

strate. They “ were orderly except for the fact they were

walking in a group toward town” (Fields 47).

John Calhoun Drive and Middleton Street Group

As this group of seventy-five to one hundred proceeded

along John Calhoun Drive (also known as Highway 301 and

Highway 601) they were stopped by a police officer (Heat-

ley 44). When he ordered them to disperse, the students

refused. Asked by a member of their group if they wished

to continue, they replied affirmatively (Heatley 45). The

students continued on down the street, the officer accom

panying them, and turned right on Middleton Street. As

they neared St. John Street, they were stopped by another

officer and told to disperse (Heatley 60). When they refused

they were arrested (Heatley 45).

This group, like the others, was well behaved and quiet

(Fields 92; Gilchrist 39; Witherspoon 79). There was no

evidence of disorder among twelve to fifteen persons

gathered on the side of Middleton Street opposite where

the petitioners walked nor among persons gathered near

All the walkers were orderly and quiet (Fields 42, 49;

Gilchrist 13). Fifteen or twenty persons other than the

students were walking on the sidewalk (Heatley 38-39).

8

No vehicular or pedestrian traffic was blocked on John

Calhoun Drive (Heatley 48-51; Gilchrist 39-40). Some

motorists stopped of their own accord (Fields 82). A

patrolman testified that the students covered the sidewalk

on John Calhoun Drive (Fields 87; Gilchrist 44) but he

also testified that the students walked in pairs (Gilchrist

39) and that no pedestrians were prevented from passing

(Heatley 48-51; Gilchrist 40).

Officer Brant testified that “ Traffic had stopped on the

right side (of Middleton Street) where cars could not go

through” (Witherspoon 57, 71). However, he also testified

that the students themselves blocked no traffic on this street

(Witherspoon 71; Heatley 51). Nor did he, while walking

in the street (Witherspoon 67), stop any cars himself

(Heatley 51). The Middleton Street sidewalk is wide enough

for only two to pass (Gilchrist 35, 41). Brant testified that

pedestrians were unable to use the sidewalks (Fields 83)

but gave no evidence of any actual meeting of pedestrians

and students. The pedestrians he observed were going into

places of business on the street (Gilchrist 35; Heatley 45;

Witherspoon 56).

The arresting officer testified in two trials that the stu

dents, as they proceeded along Middleton Street, were on

the sidewalk (Fields 92; Gilchrist 43). In a third he testi

fied that two students were at the curb edge but not in the

middle of the street, nor did they block traffic (Witherspoon

77). He testified at one point that pedestrians were blocked

from using the sidewalk (Witherspoon 77), but changed

this to say that, as the students were walking toward him,

two abreast, he asked several pedestrians to step aside

(Witherspoon 77, 78). He added that no pedestrians were

blocked by the students (Witherspoon 79). The students

St. John Street. Both groups moved when requested by the

police (Fields 77, 84; Gilchrist 34; Witherspoon 55, 79).

9

supported this view and said they were ready to move into

single file if a pedestrian appeared to allow passage (Fields

126-127).

Facts in Common

All the cases have significant facts in common. Each stu

dent group attempted to walk to a public square in the

center of the city to register its protest against racial

segregation. Each was prevented from reaching this des

tination. Each was orderly and peaceful. The students did

not prevent vehicular traffic from passing; pedestrians were

not inconvenienced. Reasons for the arrests, other than

walking without a permit and failure to disperse, were

that the community was tense (Gilchrist 10, 26; Heatley

60; Witherspoon 74) and that the students had no right to

demonstrate (Heatley 24). There is no evidence that the

police received any information of violence the day of the

arrests. They based their conclusion on three demonstra

tions which had taken place prior to the date of the arrests

and on talks with several persons in the community (Fields

18). February 25th students had picketed the Kress Dime

Store and no disturbance had taken place (Gilchrist 12).

February 26th, more than two weeks before the students

were arrested, a white and a Negro had been arrested for

a brief “ fisticuff” during a sit-in at the same store (Fields

15; Gilchrist 12). This was the only instance of violence

recited to justify the petitioners’ arrest. March 1st, six

hundred to seven hundred Negro students walked through

town peacefully. Two persons were arrested that day “ from

incidents that happened during the parading,” and four

boys also were arrested apparently for having had paper

bags over their heads (Heatley 66).

The Chief of Police talked to between ten and fifteen

persons (Fields 33) who voiced no hostile objections nor

10

did they suggest that they would forcibly stop the demon

strations (Fields 31, 39). The Assistant Chief of the South

Carolina Law Enforcement Division talked to thirty or

forty individuals (Witherspoon 50). Some expressed their

feelings in a “belligerent manner” (Witherspoon 48) but

none threatened violence themselves (Witherspoon 50).

“ They were afraid of what somebody else might do” (With

erspoon 50). Those who feared a disturbance never said

from what source it might come (Heatley 43). Other evi

dences of “ tension” were found in the fact that people

“ would simply want to know what was going on around

there at Kress’ Five and Ten Cents Store” (Witherspoon

29). There were no threats (Witherspoon 29). On the day

of the arrests there was no evidence of violence or threat

ened violence.

There is no evidence that any of the groups of students

blocked traffic or interfered with pedestrians. Whatever

interference with traffic or pedestrians there was seems

to have been a result of curiosity or police conduct (Fields

20, 40, 43, 47, 63, 64, 77, 84; Heatley 34, 48-51; Witherspoon

21, 67, 71, 77, 78; Gilchrist 29). The few pedestrians in

the area of the demonstration seem to have been curious

onlookers rather than persons blocked from reaching some

specific destination (Heatley 45; Witherspoon 55, 56, 77,

78, 79; Gilchrist 34, 35, 40).

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

The petitioners in these seven cases were tried before

the Court of Magistrate, Orangeburg County, in seven

separate trials on the 28th (Fields) and 31st (Gilchrist) of

March, the 5th (Witherspoon), 8th (Heatley), 22nd (J.

Brown), and 28th (Davenport) of April, and the 7th

(Graham) of May, 1960.

11

Prior to entry of their pleas in most cases, petitioners

moved to dismiss on the ground that prosecution for the

offense charged in the circumstances alleged would con

stitute a denial of due process of law under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States (Fields

8; Witherspoon 5; Heatley 5; J. Brown 5; Davenport 4-5;

Graham 5). These were denied (Fields 8; Witherspoon 5;

Heatley 5; J. Brown 5; Davenport 5; Graham 5). In Gil

christ, petitioners objected specifically to denial of their

freedom of expression and peaceful assembly in their pleas

of not guilty (Gilchrist 6). Similar pleas were entered in

other cases (Fields 12-13; Witherspoon 5-6).

Motions to dismiss on similar grounds were made at the

close of the prosecution’s case (Heatley 89; J. Brown 7;

Davenport 6; Graham 6-7) and prior to entry of judgment

(Fields 135; Gilchrist 91; Witherspoon 130, 131; Heatley

122; J. Brown 7; Davenport 6; Graham 6-7).

In all cases, after judgment of guilt and sentence, mo

tions in arrest of judgment or in the alternative for a new

trial were made on the grounds, inter alia, that the evidence

established that, the students were prosecuted only “ for the

purpose of preventing them from engaging in peaceful as

sembly” to protest against racially discriminatory prac

tices of the community, “ contrary to the Due Process and

Equal Protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution” (Witherspoon 132-33;

Heatley 122, 124; J. Brown 7; Davenport 7; Graham 7)

and that the evidence showed conclusively that at the time

of their arrests the students were included in a peaceful

and lawful assemblage of persons (Fields 139; Gilchrist

93; Witherspoon 134). These motions were all denied by

the trial court (Fields 135, 139; Gilchrist 91, 93; Wither

spoon 131, 132, 134; Heatley 89, 123, 124; J. Brown 7;

Davenport 7; Graham 7).

12

Petitioners appealed in all seven cases, as did the defen

dants in the companion case of State v. Irene Brown (22a-

39a), to the Orangeburg County Court, where arguments

on the eight appeals, involving several identical issues,

were heard together. The County Court affirmed all eight

convictions (3a, 7a, 10a, 13a, 16a, 18a, 20a), issuing eight

separate orders. The orders of the County Court in the

seven cases involving petitioners here relied primarily and

directly (5a, 8a, 11a, 14a, 16a, 18a, 20a) on the order ren

dered in State v. Irene Brown (22a) in which the County

Court dealt with the Constitutional issues raised at trial.

On the authority of Feiner v. New York, 300 N. Y. 391, 91

N. E. 2d 319, the County Court held that “ no action was

taken until the police authorities in their considered judg

ment came to the conclusion that the point had been reached

where the action of the Appellants was dangerous to the

peace of the community” (29a).

Before the Supreme Court of South Carolina the eight

cases were consolidated for argument “because all of the

cases involve basically the same issues and facts” (31a).

The Supreme Court affirmed the seven cases here (6a, 9a,

12a, 15a, 17a, 19a, 21a) on the express authority of its opin

ion in State v. Irene Brown (31a), in which the constitu

tional issues were decided adversely to the students, al

though that case was reversed on an issue not presented in

the other cases. In Irene Brown, the Supreme Court of

South Carolina said:

“ The defendants next assert that the State failed to

prove the commission by them of the offense of breach

of peace and that their convictions were obtained in

violation of their rights to freedom of speech and as

sembly and their right to petition for redress of griev

ances, protected by . . . the First and Fourteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution. All of

13

these questions may be resolved by a determination of

whether or not there is any competent evidence to sus

tain the conviction of the defendants for a breach of

the peace” (32a-33a).

Upon the authority of State v. Edwards, ----- S. C. ------ ,

123 S. E. 2d 247, reversed, 372 U. S. 229, which had in turn

relied upon Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315, affirming,

300 N. Y. 391, 91 N. E. 2d 319, the Supreme Court of South

Carolina held in the case of Irene Brown that “ the evidence

amply sustains the conviction of the defendants of the

offense of breach of the peace” (38a).

This Court vacated the judgment of the Supreme Court

of South Carolina and remanded “ for consideration in light

of Edwards v, South Carolina,------ U. S. ——” Fields v.

South Carolina, 372 U. S. 522. Upon consideration in light

of Edwards, supra, the Supreme Court of South Carolina

adhered to its earlier decision affirming petitioners’ con

victions, infra pp. la-2a.

A R G U M E N T

I.

Conviction of Generalized Common Law Breach of the

Peace for Peaceful and Orderly Speech and Assembly

Opposed to Racial Segregation Denied Petitioners Due

Process of Law Secured by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Supreme Court of South Carolina has reconsidered

these cases in light of Edwards v. South Carolina, 372

U. S. 227 and adhered to its prior judgment, infra pp. la-

2a. The application of this Court’s decision in Edwards

to these eases is presented, therefore, for review.

The 187 petitioners in Edwards, supra, were convicted

of the common-law crime of breach of the peace, as were

14

petitioners here. They had assembled on the grounds of the

South Carolina State House “ to submit a protest to the

citizens of South Carolina, along with the legislative Bodies

of South Carolina” regarding their dissatisfaction with

racial discrimination. They walked about the State House

grounds from 30 to 45 minutes carrying placards. During

this time 200 to 300 onlookers gathered. City officials then

ordered the demonstrators to disperse and when they re

fused arrested them. The city officials, including police,

gave as reason for the arrests fear of violence from on

lookers. It was urged also that vehicular and pedestrian

traffic entering the State House grounds and on nearby

streets and sidewalks was obstructed. The Supreme Court

of South Carolina affirmed.

In reversing, this Court emphasized the absence of “ vio

lence or threat of violence” by petitioners or onlookers.

The Court stressed that speech, assembly, and petition for

redress of grievances are supposed to invite dispute and,

perhaps, stir to anger. In Edwards, South Carolina had

not sought to apply a “ precise and narrowly drawn regula

tory statute evincing a legislative judgment that certain

specific conduct be limited or proscribed” but rather a gen

eralized concept of breach of the peace not susceptible of

exact definition. Edwards, 2>12 IT. S. 229, 236.

The facts of these cases fall well within the rule of

Edwards. Indeed, if speech and assembly are to be con

stricted, Edwards would have been a far more likely medium

for that purpose than these cases. In Edwards, 187 Negroes

demonstrated for 30 to 45 minutes. Here, four separate

groups did nothing but walk in peaceful and orderly man

ner for a few city blocks. They were arrested before reach

ing the place where they desired to demonstrate.

In Edwards, 372 U. S. at 231, and in these cases there

were no “ threatening remarks, hostile gestures or offensive

15

language” by onlookers. In Edwards, Ibid., however, 200

to 300 onlookers gathered in one location; the police sought

to justify the arrests on the ground that the crowd might

become disorderly. In contrast, these records fail to re

veal the presence of bystanders or onlookers in substantial

numbers at all.

In Edwards, 372 U. S. at 233, city officials complained of

a “ religious harangue” delivered by a leader of the group

and loud, boisterous, singing. Here, there is no complaint

about noise.

In Edwards, 372 U. S. at 232, police complained that

pedestrians were impeded by onlookers although they moved

on when asked. Here, no pedestrians were blocked.

In Edwards, 372 U. S. at 231, the police permitted the

demonstrating for 30 to 45 minutes; here city officials had

decided not to “ tolerate” the demonstrations before they

began (Witherspoon 34, 64, 65, 83, 129; Fields 59, 76). Cf.

Lombard v. Louisiana,------ IJ. S. --------, 83 S. Ct. ------ , 10

L. ed. 2d 338.

As in Edwards, 372 U. S. at 236, this Court is not asked

to “ review in this case criminal convictions resulting from

the even-handed application of a precise and narrowly

drawn regulatory statute evincing a legislative judgment

that certain specific conduct be limited or prescribed.” Peti

tioners here have been convicted of the same vague and

ambiguous offense.

Here, there was no actual or imminent disorder of any

kind and only general fears that it would occur at some

unspecified time in the future, in that “ there existed in the

Orangeburg area very high tension on the part of Negroes

and Whites . . . ” (37a). This case is therefore, not like

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315, 317, 318 where a “ push

ing, milling and shoving crowd” was “ moving forward” .

16

The Supreme Court of South Carolina agreed that the stu

dents were completely peaceful (35a). Under these circum

stances the opinion below must be read as justifying crimi

nal conviction of those peacefully taking advantage of the

right to free speech and expression because nameless others

may act in a disorderly manner against the speakers. This

conflicts with Edwards. See also Terminiello v. Chicago,

337 U. S. 1; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1. Cf. Sellers v.

Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877 (8th Cir. 1947), cert. den. 332 U. S.

851.

Nor can the police seize upon traffic adjustment as a

basis for suppressing freedom of expression. Edwards,

372 U. S. at 236; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 307, 308.

Moreover, as in Edwards and Cantwell, there has been

no such specific declaration of state policy which “would

weigh heavily in any challenge of the law as infringing con-

stitional limitations.” Cantwell, 310 U. S. at 398. The Su

preme Court of South Carolina noted city officials had

advised that no further marches would be tolerated without

a permit, but petitioners were not convicted under the

specific provisions of a permit or traffic regulation. Itather,

the State chose to employ a general concept of breach of

the peace which South Carolina had never heretofore ap

plied to interference with traffic. State v. Edwards, ------

S. C. —— , 123 So. 2d 247, reversed 372 U. S. 299, in which

the State Supreme Court did so for the first time, was

subsequently reversed by this Court and was decided after

petitioners’ arrests and convictions here.

An all-inclusive breach of the peace provision “when

construed to punish conduct which cannot be constitution

ally punished, is unconstitutionally vague” Wright v.

Georgia,------ U. S . --------, 83 S. C t .------ , 10 L. ed. 2d 349,

17

355-356; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 202 (Mr. Jus

tice Harlan concurring); Edwards, supra; Cantwell, supra.

In the absence of a state statute, narrowly drawn, South

Carolina cannot punish expression which only leads to

minor interference with traffic. Petitioners’ “ communica

tion, considered in the light of the constitutional guarantees,

raised no such clear and present menace to public peace

and order as to render (them) liable to conviction of the

common law offense in question.” Cantwell v. Connecticut,

310 IT. S. 296, 311; Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359,

369; cf. Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 IT. S. 88, 105, 106.

II.

Petitioners’ Convictions on Warrants Charging That

Their Conduct “ . . . Caused Fear and Tending to Incite

A Riot or other Disorderly Conduct or Cause Serious

Trouble” Violate the Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment in That the Judgments Rest on No

Evidence of Guilt.

Petitioners were convicted of common law breach of the

peace upon warrants alleging that they (Fields 1-2; Gil

christ 2; Graham 2; Witherspoon 2; Heatley 2; Daven

port 2)

“ . . . did commit breach of the peace by unlawfully

and wilfully congregating and marching in the City

of Orangeburg, said County, and did approach what is

known as the business section of the City of Orange

burg, the groups being headed by a number of parties

who refused to stop and return to the colleges upon the

request of Chief of Police Hall and other officers in the

City of Orangeburg, thereby disturbing the peace and

tranquility of the normal traffic on the sidewalks as

well as the streets in the City of Orangeburg, which

caused fear and tending to incite a riot or other dis

18

orderly conduct or cause serious trouble, thereby com

mitting breach of the peace . . . ”

There is no evidence in these records that petitioners’

conduct “ caused fear” , tended to “ incite a riot or other dis

orderly conduct” or caused “ serious trouble” of any kind as

alleged in the warrants. The students were at all times

peaceful, orderly, well dressed, and well demeaned (see

supra at pp. 5-10). The records reveal no act or word

which might have caused violence. Absent are signs of dis

order or potential disorder, such as threatening remarks,

hostile gestures, pushing, milling or body contact. There

is a similar absence of evidence of disorder or potential

disorder by any onlookers. Nor is there evidence that a

crowd gathered to observe petitioners. Cf. Edwards v.

South Carolina, 372 U. S. at 231.

The Supreme Court of South Carolina agreed that “ the

record discloses that none of the defendants committed any

act of violence” (35a) but upheld the conviction on the

ground of “ . . . a clear and present danger of riot, dis

order, interference with traffic . . . or other immediate

threat to public peace” (35a). The finding of a clear and

present danger was supported solely by the conclusion that

“ very high tension on the part of Negroes and whites, re

sulting from a series of demonstrations on the part of Negro

students” (37a) existed in Orangeburg.

This “ tension” was found in prior demonstrations against

racial segregation, or “ clashes,” as the Supreme Court of

South Carolina called them. But the records reveal only

that on February 25, 1960 students had picketed the Kress

dime store in Orangeburg and no disturbance had taken

place (Gilchrist 12). On February 26 a white and a Negro

had been arrested for a brief “ fisticuff” during a demonstra

tion at the Kress store (Fields 15; Gilchrist 12). No other

evidence of violence is shown to have taken place in Orange

19

burg. March 1, 1960, six to seven hundred Negro students

walked through town to express disapproval of the City’s

racial policies (Heatley 66). Two persons were arrested

on that day “ from incidents that happened during parad

ing” {Ibid.).

On the ground that these prior demonstrations had

created “ tensions” between the races, the police arrested

petitioners on March 15, 1960. But these facts do not per

mit an inference of violence or threatened violence. All

they may evidence is that the students’ point of view was not

the same that other persons held in Orangeburg. Such “ ten

sion” between the races is a fact of life in the American

South today. Therefore, to find it alone sufficient basis for

abridgment would end freedom of expression in that area

of the country with respect to the race question.

Petitioners cannot be convicted because their expression

may have upset prejudices and preconceptions in the com

munity concerning issues of national importance, for this

result is the purpose of protected expression. Cf. Edwards,

372 U. S. at 237.

Petitioners cannot be convicted on the totally unsub

stantiated opinion of the police that disorder will occur.

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157; Thompson v. Louisville,

362 U. S. 199; Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154.

Nor is there evidence of traffic problems which prove

the crime charged. There is no evidence that traffic prob

lems “ caused fear” or tended to “ inciting a. riot” as charged

in the warrants. Such trivial interference with traffic on the

streets of the city as these records show was caused by ac

tions of the police. The few pedestrians who observed the

demonstration were curious bystanders and were not im

peded by the students. Any slowdown in vehicular traffic

was caused by police action in arresting or dispersing the

students, not by the behavior of the students themselves.

20

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the foregoing reasons, Petitioners pray

that the petition for writ of certiorari be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

F ran k H . H effron

G eorge B. S m it h

Of Counsel

J ack Greenberg

C onstance B aker M otley

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

M atth e w J . P erry

L incoln C. J e n k in s , J r.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia 1, South Carolina

W. N ew ton P otjgh

Orangeburg, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

la

A P P E N D I X

Order of the Supreme Court of South Carolina on

Remand Filed May 14, 1963

T h e S tate ,

Respondent,

J am es F ields, et al.,

Appellants.

T h e S tate ,

Respondent,

B obbie J. G ilch bist , et al.,

Appellants.

T h e S tate ,

—v.—

Respondent,

M arie G r a h a m , et al.,

Appellants.

T h e S tate ,

Respondent,

F ttt.a M. 'W itherspoon , et al.,

Appellants.

T h e S tate ,

— y.—

A lyin H eatley , et al.,

Respondent,

Appellants.

2a

Order of the Supreme Court of South Carolina on Rem,and

Filed May 14, 1963

T h e S tate ,

J oseph C. B ro w n , et al.,

T h e S tate ,

F rances E. D avenport, et al.,

Respondent,

Appellants.

Respondent,

Appellants.

ORDER

The mandate of the United States Supreme Court in this

case vacated the judgment of this Court and further pro

vided “ that this cause he remanded to the Supreme Court

of the State of South Carolina for consideration in light of

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229.”

Pursuant thereto, we have considered this cause in the

light of Edwards v. South Carolina and adhere to and affirm

the judgment of this Court rendered on June 6, 1962,------

S. C. — —, 126 S. E. (2d) 6, for the reasons stated in our

opinion in State v. Brown, 240 S. C. 357, 126 S. E. (2d) 1.

/ S / C. A. T aylor C. J.

N J oseph R. M oss A . J.

/*/ J. W oodrow L ew is A . J.

N T hom as P. B ussey A. J.

M J. M . B railsford A. J.

3a

The State v. James Fields et al.

ORDER

The appeals herein are from convictions in the Court of

Magistrate, Honorable D. Marchant Culler, Orangeburg

County Magistrate, presiding, upon a charge of the com

mon law crime of breach of the peace. The defendants

herein were tried jointly, and the trial was one of eight

such trials, wherein various groups were tried for the

offense stated after certain incidents which arose in the

City of Orangeburg on March 15, 1960. Approximately

350 persons were arrested as a result of the incident

referred to, and, for the sake of convenience, they were

divided into eight groups for trial.

Nearly all of the issues raised in these appeals have

been disposed of by Order handed down this date in the

case of the State v. Irene Brown, et al., and the con

clusions expressed in that Order are applicable to the

questions here presented except as hereinafter detailed.

These appeals by Exception No. 2 allege that the trial

conducted was not a public trial and was therefore in

violation of the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. The

basis for this allegation of error is that “ the room or office

in which the trial was had was so small and narrowly con

fined as to deny attendance at said trial of the relatives,

friends and persons interested in the welfare of the de

fendants” .

There is no merit in this contention. The Courtroom

was admittedly small, being described by the presiding

Magistrate as approximately 15 by 30 feet. The Court

Order of the Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

4a

takes judicial notice of the fact that this was the regu

lar Courtroom of the presiding Magistrate for the hear

ing of all matters, and takes further notice that this is

not an unusually small Courtroom as is customarily pro

vided for Magistrates of South Carolina. Irrespective of

this, the trial was in all respects a public trial and the

allegations of error in this respect are totally without

merit. 48 A. L. R. (2d) 1436. It is particularly noted

that there is no showing that anyone was, in fact, excluded

from attendance upon the trial. Consequently, there was

no predudice to any of the appellants.

Exception No. 8 of the appeals herein alleges error in

declining to “ expunge the testimony of the State’s wit

nesses, such testimony having not identified any of these

defendants as having committed any crime * * * ”

The testimony reveals that the participants in the demon

stration leading to the arrest were taken to the City

Jail, or to the jail yard of the County of Orangeburg,

and thereafter all of the participants were taken to the

County Courthouse and from the latter place to the

Magistrate’s office, where they gave bond. During this

period all of the participants were under the surveillance

and in the custody of police officers. While in custody

they each executed bonds, which bonds were offered in

evidence and admitted without objection, in the course of

the trial. (Tr. pp. 79, 80, 95.) The two defendants who

testified admitted participating as a group in the march.

(Tr. pp. 147, 163.)

It appears clear that the defendants were identified as

participants in the demonstration and this Exception is

therefore overruled.

Order of Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

5a

Order of Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

The Order of this Court in the case of The State v.

Irene Brown, et al., is hereby adopted as conclusive of the

other exceptions raised in these appeals.

All other exceptions of the appellants are overruled

and the convictions and sentences are affirmed.

/ s / J am es B . P eu itt ,

J am es B. P eu itt ,

Presiding Judge,

First Judicial Circuit.

December 5, 1961.

6a

I n th e S uprem e C ourt oe S ou th C arolina

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Filed June 6, 1962

T h e S tate ,

v.

Respondent,

J am es F ields, et al.,

Appellants.

L ew is , A.J. : These defendants, 22 in number, were tried

by the Magistrate at Orangeburg, South Carolina, without

a jury, and found guilty of the offense of breach of the

peace. They have appealed and charge error on the part

of the trial court (1) in refusing to dismiss the warrant

issued against them on the grounds that the information

upon which the warrant was issued failed to fully set forth

the crime charged, and (2) in refusing to sustain their

contention that the State failed to prove the commission by

them of the offense of breach of the peace. Under basically

the same facts, the identical issues were presented in the

case of The State v. Irent Brown, et al. and decided ad

versely to the contentions of these defendants. The decision

in that case, which is being filed simultaneously herewith,

is controlling here and requires affirmance of the judgment

of the lower court.

Affirmed.

T aylor, C.J., Moss, B ussey and Brailseord, JJ., concur.

7a

The State v. Bobbie J. Gilchrist

ORDER

The appeals herein are from convictions in the Court

of Magistrate, Honorable D. Marchant Culler, Orangeburg

County Magistrate, presiding, upon a charge of the common

law crime of breach of the peace. The defendants herein

were tried jointly, and the trial was one of eight such trials,

wherein various groups were tried for the offense stated

after certain incidents which arose in the City of Orange

burg on March 15, 1960. Approximately 350 persons were

arrested as a result of the incident referred to, and, for

the sake of convenience, they were divided into eight groups

for trial.

In these appeals, by Exception No. 1, the defendants

urge that the Court erred in allowing an amendment to

the warrant after the case was called for trial.

The original warrant alleged that the defendants ap

proached Lowman and Russell Streets which enter the

business section of the City of Orangeburg and that the

group was headed by one Daniel Blue. The amended war

rant alleged that the defendants approached what is known

as the business section of the City of Orangeburg, the

groups being headed by a number of parties.

It is manifest that the amendment to the warrant was

of slight significance and cannot in any manner be construed

to have prejudiced the rights of these defendants. Section

43-112 of the 1952 Code of Laws allows an amendment of the

information at any time before trial. See also Town of

Mayesville v. Clamp, 149 S. C. 346, 147 S. E. 455. This

exception is without merit.

Order of the Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

8a

Order of Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5 , 1961

The remaining excejitions are disposed of by the con

clusions expressed in the Orders of the Court in the com

panion cases of The State v. Irene Brown, et al., and The

State v. James Fields, et al., which Orders are incorporated

herewith as a part of this Order.

All exceptions of the appellants are overruled and the

convictions and sentences are affirmed.

s / J ames B . P ru itt ,

Presiding Judge,

First Judicial Circuit.

December 5, 1961.

9a

I n th e S uprem e C ourt op S ou th C arolina

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Filed June 6, 1962

T h e S tate ,

v.

Respondent,

B obbie J. G ilch rist , et al.,

Appellants.

L ew is , A.J. : These defendants, 28 in number, were tried

by the Magistrate at Orangeburg, South Carolina, without

a jury, and found guilty of the offense of breach of the

peace. They have appealed and charge error on the part

of the trial court (1) in refusing to dismiss the warrant

issued against them on the grounds that the information

upon which the warrant was issued failed to fully set forth

the crime charged, and (2) in refusing to sustain their

contention that the State failed to prove the commission by

them of the offense of breach of the peace. Under basically

the same facts, the identical issues were presented in the

case of The State v. Irene Brown, et al. and decided ad

versely to the contentions of these defendants. The decision

in that case, which is being filed simultaneously herewith,

is controlling here and requires affirmance of the judgment

of the lower court.

Affirmed.

T a y lo r , C.J., Moss, B u ssey a n d B ra ilsfo rd , J J co n cu r .

10a

The State v. Marie Graham, et al.

ORDER

The appeals herein are from convictions in the Court of

Magistrate, Honorable D. Marchant Culler, Orangeburg

County Magistrate, presiding, upon a charge of the common

law crime of breach of the peace. The defendants herein

were tried jointly, and the trial was one of eight such trials,

wherein various groups were tried for the offense stated

after certain incidents which arose in the City of Orange

burg on March 15, 1960. Approximately 350 persons were

arrested as a result of the incident referred to, and, for the

sake of convenience, they were divided into eight groups for

trial.

Exception No. 2 alleges error of the Court “ in permitting

the State’s witnesses * * * to testify to ‘clear and present

danger.’ ”

The precise testimony complained of is not detailed. It

appears manifest, however, from a reading of the record

stipulated as controlling in these cases, that the testimony

of the witnesses for the State as to the circumstances which

existed prior to and at the time of the demonstration which

led to the arrests bore directly upon the issue of whether

a breach of the peace was imminent. Such testimony was

therefore clearly relevant as pointedly indicated in People

v. Feiner, 300 N. Y. 391, 91 N. E. (2d) 319, upheld by the

United States Supreme Court, 340 U. S. 315, 95 L. Ed. 295.

An act which is lawful in some circumstances may be unlaw

ful in others and testimony of the State’s witnesses which

tended to establish the tensions and emotions existing in

the community was clearly admissible. The Exception made

Order of the Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

11a

is most general in nature, no specific testimony has been

called to the attention of the Court as objectionable, and

a study of the record by the Court fails to reveal any testi

mony which may come within the scope of this general

exception and the same is overruled.

All other exceptions have been duly considered and found

to be controlled by the Order of this Court in the com

panion cases of State v. Irene Brown, et al., State v. James

Fields, et al., and State v. Bobby J. Gilchrist, et al., which

Orders are hereby incorporated herein.

All exceptions of the appellants are overruled and the

convictions and sentences are affirmed.

s / J ames B . P ru itt ,

Presiding Judge,

First Judicial Circuit.

Order of Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

December 5, 1961.

12a

I n th e S uprem e C ourt oe S o u th Carolina

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Filed June 6, 1962

T h e S tate ,

v.

Respondent,

M arie Grah a m , et al.,

Appellants.

L ew is , A.J. : These defendants, 91 in number, were tried

by the Magistrate at Orangeburg, South Carolina, without

a jury, and found guilty of the offense of breach of the

peace. They have appealed and charge error on the part

of the trial court (1) in refusing to dismiss the warrant

issued against them on the grounds that the information

upon which the warrant was issued failed to fully set forth

the crime charged, and (2) in refusing to sustain their

contention that the State failed to prove the commission by

them of the offense of breach of the peace. Under basically

the same facts, the identical issues were presented in the

case of The State v. Irene Brown, et al. and decided ad

versely to the contentions of these defendant. The decision

in that case, which is being filed simultaneously herewith,

is controlling here and requires affirmance of the judgment

of the lower court.

Affirmed.

T a y lo r , C.J., Moss, B u ssey a n d B railseord , J J con cu r .

13a

The State v. Eula M. Witherspoon, et al.

ORDEE

The appeals herein are from convictions in the Court

of Magistrate, Honorable D. Marchant Culler, Orange

burg County Magistrate, presiding, upon a charge of the

common law crime of breach of the peace. The defendants

herein were tried jointly, and the trial was one of eight such

trials, wherein various groups were tried for the offense

stated after certain incidents which arose in the City of

Orangeburg on March 15, 1960. Approximately 350 persons

were arrested as a result of the incident referred to, and,

for the sake of convenience, they were divided into eight

groups for trial.

Exception No. 4 alleges error in not permitting a State’s

witness to “ be questioned relative to the source of his

authority to stop the peaceful demonstration of the defen

dants and to arrest them.” This has apparent reference

to the testimony of the witness Morrison W. Whetstone,

Captain, Orangeburg City Police Department. On cross

examination Captain Whetstone testified that he had asked

a group of the defendants, who were marching in column,

to stop. He was asked “ * * * what authority were you

acting pursuant to?” The following is taken from the

Transcript of testimony, page 19:

“ A. As my duties as a police officer to preserve peace

and order.

Q. I understand that, but isn’t it a fact, Captain

Whetstone, that most police activity is done pursuant

to some ordinance or statute?

A. That’s correct.

Order of the Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

14a

Q. Then what ordinance or statute were you acting

pursuant to?

A. I believe this is taken from the State statute.

Q. You were not acting pursuant to any Orangeburg

municipal ordinance?

A. No, sir.”

The testimony sought to be elicited was clearly a matter

of law and not within the proper scope of examination. It

had no bearing upon the guilt or innocence of these defen

dants and it is not apparent how in any manner it could

have enlightened the Court thereabout. No showing of

prejudice to any defendant is made. This Exception is

therefore overruled.

All other exceptions have been duly considered and are

hereby overruled. Most, if not all, of the exceptions are

controlled by the Orders of this Court in the parallel cases

of State v. Irene Brown et al.; State v. James Fields et al.;

State v. Bobby J. Gilchrist et al.; and State v. Marie Graham

et al., which Orders are hereby incorporated herein.

All exception s o f the appellants are overru led and the

con v iction s and sentences are affirmed.

s / J ames B . P ru itt ,

Presiding Judge,

First Judicial Circuit.

Order of Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

December 5,1961.

15a

I n th e S uprem e C ourt of S o u th C arolina

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Filed June 6, 1962

T h e S tate ,

v.

Respondent,

E u la M, W itherspoon , et al.,

Appellants.

L ew is , A.J. : These defendants, 50 in number, were tried

by the Magistrate at Orangeburg, South Carolina, without

a jury, and found guilty of the offense of breach of the

peace. They have appealed and charge error on the part

of the trial court (1) in refusing to dismiss the warrant

issued against them on the grounds that the information

upon which the warrant was issued failed to fully set forth

the crime charged, and (2) in refusing to sustain their

contention that the State failed to prove the commission by

them of the offense of breach of the peace. Under basically

the same facts, the identical issues were presented in the

case of The State v. Irene Brown, et al. and decided ad

versely to the contentions of these defendants. The decision

in that case, which is being filed simultaneously herewith,

is controlling here and requires affirmance of the judgment

of the lower court.

Affirmed.

T a y lo r , C.J., Moss, B u ssey and B railsfo rd , JJ., concur.

16a

The State v. Alvin Heatley, et al.

ORDER

The appeals herein are from convictions in the Court

of Magistrate, Honorable D. Marchant Culler, Orangeburg

County Magistrate, presiding, upon a charge of the com

mon law crime of breach of the peace. The defendants

herein were tried jointly, and the trial was one of eight

such trials, wherein various groups were tried for the

offense stated after certain incidents which arose in the

City of Orangeburg on March 15, 1960. Approximately 350

persons were arrested as a result of the incident referred

to, and, for the sake of convenience, they were divided into

eight groups for trial.

All exceptions have been duly considered. The issues

raised have been disposed of by the Orders of this Court

in the cases of State v. Irene Brown, et al., State v. James

Fields, et al., State v. Bobby J. Gilchrist, et al., State v.

Marie Graham, et al., and State v. Eula M. Witherspoon,

et al., which Orders are herewith incorporated as a part of

the Order.

All exceptions of the appellants are over-ruled and the

convictions and sentences are affirmed.

s / J ames B . P bttitt,

Presiding Judge,

First Judicial Circuit.

Order of the Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

December 5, 1961.

17a

I n th e S uprem e C ourt op S o u th C arolina

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Filed June 6, 1962

T h e S tate,

v.

A lvin H eatley, et al.,

Respondent,

Appellants.

L ew is , A.J.: These defendants, 47 in number, were tried

by the Magistrate at Orangeburg, South Carolina, without

a jury, and found guilty of the offense of breach of the

peace. They have appealed and charge error on the part

of the trial court (1) in refusing to dismiss the warrant

issued against them on the grounds that the information

upon which the warrant was issued failed to fully set forth

the crime charged, and (2) in refusing to sustain their

contention that the State failed to prove the commission by

them of the offense of breach of the peace. Under basically

the same facts, the identical issues were presented in the

case of The State v. Irene Brown, et al. and decided ad

versely to the contentions of these defendants. The decision

in that case, which is being filed simultaneously herewith,

is controlling here and requires affirmance of the judgment

of the lower court.

Affirmed.

T a y lo r , C.J., Moss, B u ssey a n d B railsfo rd , J J concur.

18a

The State v. Joseph C. Brown et al.

ORDER

The appeals herein are from convictions in the Court

of Magistrate, Honorable D. Marchant Culler, Orangeburg

County Magistrate, presiding, upon a charge of the com

mon law crime of breach of the peace. The defendants

herein were tried jointly, and the trial was one of eight

such trials, wherein various groups were tried for the

offense stated after certain incidents which arose in the

City of Orangeburg on March 15, 1960. Approximately

350 persons were arrested as a result of the incident re

ferred to, and, for the sake of convenience, they were

divided into eight groups for trial.

All exceptions have been duly considered. The issues

raised have been disposed of by the Orders of this Court

in the cases of State v. Irene Brown, et al., State v. James

Fields, et al., State v. Bobby J. Gilchrist, et al., and State

v. Marie Graham, et al., which Orders are herewith incor

porated as a part of this Order.

All exceptions of the Appellants are overruled and the

convictions and sentences are affirmed.

s / J ames B. P r u it t ,

Presiding Judge,

First Judicial Circuit.

Order of the Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

December 5, 1961.

19a

I n th e S uprem e C ourt of S o u th C arolina

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Filed June 6, 1962

T h e S tate,

Y.

Respondent,

J oseph C. B ro w n , et al.,

Appellants.

L ew is , A.J.: These defendants, 50 in number, were tried

by the Magistrate at Orangeburg, South Carolina, without

a jury, and found guilty of the offense of breach of the

peace. They have appealed and charge error on the part

of the trial court (1) in refusing to dismiss the warrant

issued against them on the grounds that the information

upon which the warrant was issued failed to fully set forth

the crime charged, and (2) in refusing to sustain their

contention that the State failed to prove the commission by

them of the offense of breach of the peace. Under basically

the same facts, the identical issues were presented in the

ease of The State v. Irene Brown, et al. and decided ad

versely to the contentions of these defendants. The decision

in that case, which is being filed simultaneously herewith,

is controlling here and requires affirmance of the judgment

of the lower court.

Affirmed.

T a y lo r , C.J., Moss, B u ssey a n d B railsfo rd , JJ., con cu r .

20a

The State v. Frances E. Davenport, et al.

ORDER

The appeals herein are from convictions in the Court

of Magistrate, Honorable D. Marchant Culler, Orange

burg County Magistrate, presiding, upon a charge of the

common law crime of breach of the peace. The defendants

herein were tried jointly, and the trial was one of eight

such trials, wherein various groups were tried for the

offense stated after certain incidents which arose in the

City of Orangeburg on March 15, 1960. Approximately

350 persons were arrested as a result of the incident re

ferred to, and, for the sake of convenience, they were

divided into eight groups for trial.

All exceptions have been duly considered. The issues

raised have been disposed of by the Orders of this Court

in the eases of State v. Irene Brown, et al., State v. James

Fields, et al., State v. Bobby J. Gilchrist, et al., State v.

Marie Graham, et al., and State v. Eula Witherspoon, et al.,

which Orders are herewith incorporated as a part of this

Order.

All exceptions of the appellants are overruled and the

convictions and sentences are affirmed.

s / J ames B . P k u itt ,

Presiding Judge,

First Judicial Circuit.

Order of the Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

December 5, 1961.

21a

I n th e S uprem e C ourt op S outh C arolina

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Filed June 6, 1962

T h e S tate ,

v.

Respondent,

F rances E. D avenport, et al.,

Appellants.

L e w i s , A.J. : These defendants, 46 in number, were tried

by the Magistrate at Orangeburg, South Carolina, without

a jury, and found guilty of the offense of breach of the

peace. They have appealed and charge error on the part

of the trial court (1) in refusing to dismiss the warrant

issued against them on the grounds that the information

upon which the warrant was issued failed to fully set forth

the crime charged, and (2) in refusing to sustain their

contention that the State failed to prove the commission by

them of the offense of breach of the peace. Under basically

the same facts, the identical issues were presented in the

case of The State v. Irene Brown, et al. and decided ad

versely to the contentions of these defendants. The decision

in that case, which is being filed simultaneously herewith,

is controlling here and requires affirmance of the judgment

of the lower court.

Affirmed.

T a y lo r , C.J., Moss, B u ssey and B railsfo rd , JJ., concur.

22a

The State v. Irene Brown, et al.

ORDER

This is an appeal from conviction by a jury in the

Court of Honorable D. Marchant Culler, Orangeburg

County Magistrate, upon a charge of the common law

crime of breach of the peace. There are fifteen defendants

who were convicted at a trial held in Orangeburg on March

16, 17, 18 and 19, 1960. Upon convictions, they were given

an alternative sentence of $50.00 fine or 30 days imprison

ment. Timely notice of appeal to this Court was given

and arguments were heard by me in open court. Counsel

for the State and for the Defendants have both filed briefs.

Appellants were part of a group of nearly three hundred

students who left the campus of Claflin University in the

City of Orangeburg on March 15, 1960 at approximately

midday to proceed to the main business section of the

city. The announced purpose as developed during the

course of the trial was that these Defendants were pro

ceeding for the purpose of expressing grievances and to

petition officials of the city, county and state governments

for redress of grievances. This purpose is contained in a

so-called plea to the information which the Defendants

made. There was no evidence adduced to show that there

was any official of the State government present in the

City of Orangeburg on that day. No audience had been

sought by any of the Defendants with any official of the

City or County of Orangeburg.

The testimony shows that a large group of these students

appeared on the date stated, going west on East Russell

Street in the City of Orangeburg and were met there by

Order of the Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

23a

Chief of Police Hall and other officers. They were re

quested by these officials to return to their school and they

refused to do so. Testimony is contained in the record

that traffic was blocked, streets were cluttered and a large

crowd of citizens were gathering at this location.

There is further testimony that another large group

appeared going west on East Amelia Street in the direc

tion of the main business district. This group also refused

to turn back when requested to do so. Upon the refusal

of the Defendants to return to their campus, some two

hundred and eighty-eight were arrested, charged with

breach of the peace and confined in the city and county

jails in Orangeburg.

All defendants were released on bond before the day

was over and the fifteen who compose the Appellants

here were called to trial on March 16, 1960 and convicted

by jury as heretofore set forth.

Appellants excepted to the verdict and judgment of con

viction upon eight specifically stated grounds and one

general ground reserving as an exception any error which

might be disclosed by the record. The eight specific grounds

will be considered and disposed of in order.

The first exception relates to the denial of various mo

tions for a continuance made prior to the commencement

of the trial. No showing is made that this denial of a

continuance has injured the Appellants in any way. This

is a misdemeanor charge and there is no showing that

Defendants were prejudiced. Under the well-settled rule

of this State, the granting of a continuance is within the

discretion of the trial judge. I find no abuse of discretion

and, therefore, no error. See State v. Livingston, 223 S. C.

1, 73 S. E. (2d) 850.

Order of Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

24a

The second exception concerns the denial of a motion

for severance and separate trials for the Defendants. It

is again well settled under the law of this State that the

severance of Defendants is a matter for the discretion of

the trial judge. State v. Britt, et al, 237 S. C. 293, 117

S. E. (2d) 371.

The record reveals that previous demonstrations had

caused such a feeling of apprehension on the part of the

police officers of the City of Orangeburg that additional

officers had been procured to prevent and control any out

break of disorder or violence. The record amply substan

tiates the position taken by the officials of the City of

Orangeburg that the appearance of large groups of per

sons marching along the streets would most probably result

in serious disturbances. The apprehension entertained by

these officials was fully justified. Traffic conditions were

impeded to such an extent that one of the officers testified

that persons walking upon the sidewalks were compelled

to take refuge in places of business. In these circumstances,

the action of the police officials in moving quickly to avoid

a clear and present danger to the public order was fully

warranted.

Exception number three is from the denial of a motion

to quash the information and to dismiss the warrant. An

examination of the warrant which is before me shows that

it plainly and substantially sets forth the charge of breach

of the peace. There was no error in the refusal of a motion

to quash and dismiss. Duffle v. Edwards, 185 S. C. 91,

193 S. E. 211.

Exception number four is from a denial of a motion to

request the jurors to submit to a voir dire examination. It

appears from the record that the selection of a jury in this

Order of Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

25a

case was made strictly in accordance with the provisions

of Section 43-116 of the 1952 Code of Laws of South Caro

lina. That section makes no provision for the placing of

Magistrate’s Court jurors on their voir dire examination.

The contention that voir dire examination is a matter of

right in the Magistrate’s Court is a novel one in this State.

It is well settled that the requirements of due process in

Magistrate’s Courts are satisfied by a summary trial held

in a fair and just manner. State v. Randolph, et al., filed

August 23, 1961. Section 38-3 of the 1952 Code of Laws

of South Carolina recites that nothing contained in the

provisions of the Code relating to juries and jurors in

Circuit Courts shall affect the power and duty of Magis

trates “ to summon and empanel jurors when authorized by

code provisions of law.” Since Section 43-116 is an entirely

separate provision and relates only to Magistrate’s Court

and contains no provision for voir dire examination, I am

of the opinion that such examination is not allowable. See

Schnell v. State, 17 S. E. 966, 92 Ga. 459.

Having concluded that there is no such right in the Courts

of Magistrate, I find that it was, therefore, not error to

deny the motion. Moreover, the transcript of the trial

shows that Appellants did not use any of the ten peremp

tory challenges which were allowed them, and made no

complaint that the jury was biased or otherwise disquali

fied in any respect. State v. Gantt, 223 S. C. 431, 75 S. E.

(2d) 674. No showing whatever of any prejudice to the

Appellants has been made.

The fifth exception relates to a challenge to the array

of the jury panel on the grounds that Negroes were system

atically excluded therefrom. This exception is patently

untenable inasmuch as it is undisputed that a Negro was a

member of the trial jury.

Order of Orangeburg County Court

Filed December 5, 1961

26a

The sixth exception relates to the refusal to permit cross

examination of the Chief of Police of Orangeburg with

respect to his personal views as to the efforts of members

of the colored race to obtain service at lunch counters at

which white persons are normally and customarily served.

The question was raised, purportedly, for the purpose of

showing bias and prejudice on the part of the witness.

The issue of whether colored persons and white persons

should be seated and be served at the same time at lunch

counters was not a matter which related in any degree to

the prosecution. At best, such testimony would only re

motely relate to any bias or prejudice on the part of the