Rogers v Lodge Brief of Appellees

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1980

58 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rogers v Lodge Brief of Appellees, 1980. 3d07e42a-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e8b2618b-cf2f-48e1-9f09-3756504cea45/rogers-v-lodge-brief-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

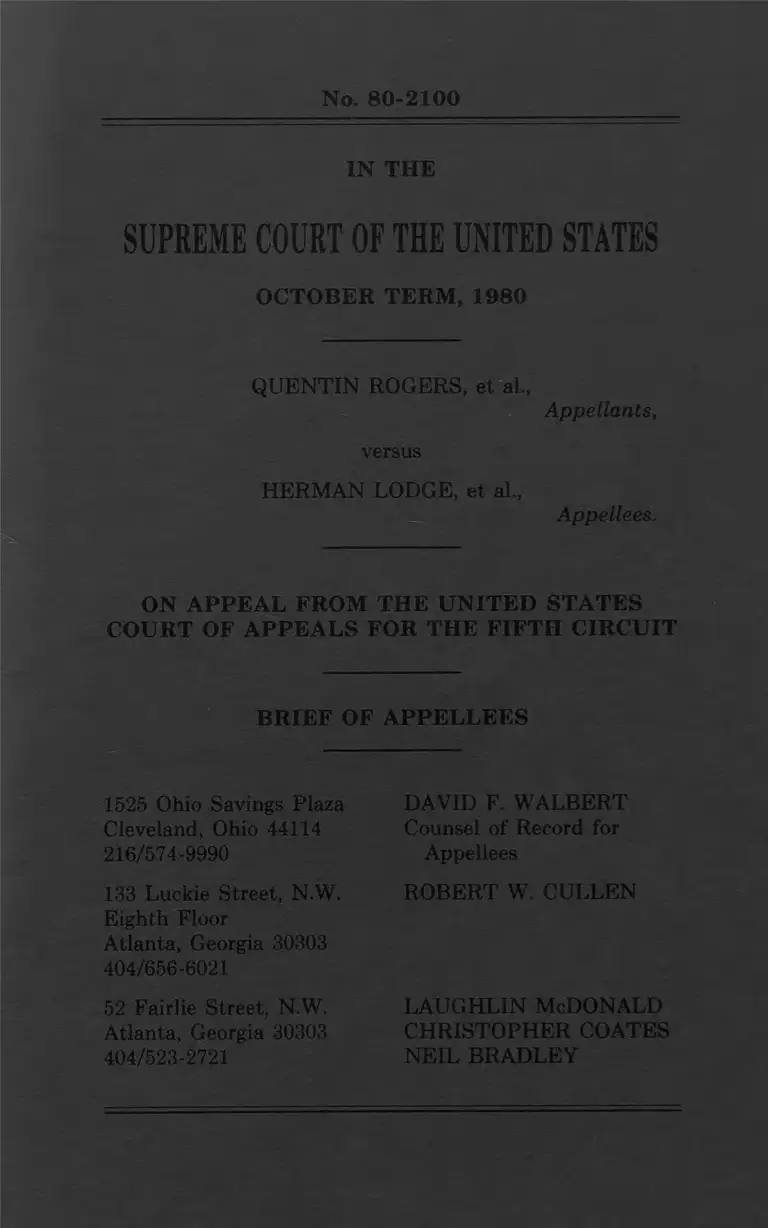

No. 80 -2100

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1980

QUENTIN ROGERS, et al.,

Appellants,

versus

HERMAN LODGE, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

1525 Ohio Savings Plaza

Cleveland, Ohio 44114

216/574-9990

133 Luckie Street, N.W.

Eighth Floor

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

404/656-6021

52 Fairlie Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

404/523-2721

DAVID F. WALBERT

Counsel of Record for

Appellees

ROBERT W. CULLEN

LAUGHLIN McDONALD

CHRISTOPHER COATES

NEIL BRADLEY

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. WHETHER PURPOSEFUL DISCRIMINATION

UNDER THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

WAS PROVED IN THIS CASE

II. WHETHER STATUTORY ELECTION CASES

MAY BE MAINTAINED WITHOUT PROVING

INTENTIONAL DISCRIMINATION

III. WHETHER THE JUDGMENT OF THE LOWER

COURT SHOULD BE AFFIRMED ON THE

BASIS OF THE FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT

IV. WHETHER THE JUDGMENT OF THE LOWER

COURT SHOULD BE AFFIRMED ON THE

BASIS OF THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESEN TED .............................................. i

CITATION OF AUTHORITIES iii

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ........................................ 1

SUMMARY OF A R G U M E N T.......................................... 24

ARGUMENT ........................................................................ 25

I. Purposeful Discrimination Under the Fourteenth

Amendment Was Proved In This C ase.................. 25

A. The Evidence Of Intentional Discrimination

In This Case Entirely Supports the Lower

Courts’ Conclusion That At-Large Elections

Are Maintained In Burke County For The

Purpose Of Discrimination.............................. 25

B. This Case Differs Significantly From The

Facts And Issues Presented In B olden ........ 33

C. The Other Issues Raised By Appellants Have

No M erit.............................................................. 36

II. Statutory Election Cases May Be Maintained

Without Proving Intentional Discrimination........ 41

III. The Judgment Of The Lower Court Should Be

Affirmed On The Basis Of The Fifteenth

Am endm ent.................................................................. 46

IV. The Judgment Of The Lower Court Should Be

Affirmed On The Basis Of The Thirteenth

Am endm ent.................................................................. 48

CONCLUSION...................................................................... 50

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Allen v. State Bd. of Elections, 393 U.S. 544

(1969).......................................................... 41

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing De

velopment Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977). 25

Bolden v. City of Mobile, 423 F. Supp. 384 (S.D.

Ala. 1976) ........................................................... 33

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883)....... 48

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443

U.S. 449 (1979) .................................................. 29

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 443

U.S. 526 (1979) .................................................. 36

Dougherty County Board of Education v.

White, 439 U.S. 32 (1978)....................... 42

FPC v. Florida Power and Light, 404 U.S. 453

(1972)........................................................... 26

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980) . . . 41

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) . . . 40

Graves v. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704 (W.D. Tex.

1972)............................................................. 38

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971)........................................................... 43

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409

(1968)........................................................... 49

Lodge v. Buxton, 639 F.2d 1358 (5th Cir. 1981) passim

McMillan v. Escambia County, 638 F.2d 1239

(5th Cir. 1981) 37

IV

Memphis, City of u. Greene, 101 S.Ct. 1584

(1981).................................................................... 48

Michalic v. Cleveland Tankers, 364 U.S. 325

(I960).................................................................... 26

Mobile, City of v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) 27, 34

Moore v. Brown, 448 U.S. 1335 (1980)................. 35

Personnel Administrator v. Feeney, 442 U.S.

256 (1979)............................................................ 26, 33

Rogers v. Missouri Pac. R. Co., 352 U.S. 500

(1957).................................................................... 26

Rome, City of v. United States, 446 U.S. 156

(1980).................................................................... 41

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301

(1966).................................................................... 3

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971)............ 33

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) .......... 35, 37, 38

Wilkes County v. United States, 439 U.S. 999

(1978).................................................................... 46

United States v. Bd. of Comm’rs. of Sheffield,

435 U.S. 110 (1978)............................................ 44

United States v. Georgia, 436 U.S. 941 (1978) 32

Constitutional Provisions

Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States...................................... 24, 40, 48, 49

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States...................................... 24, 40, 46, 48

Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States........................................ 24, 40, 43-47

Georgia Constitution, Ga. Code §2-403 ............ 32

Statutes

v

42 U.S.C. §1971 (a )(1 ) ............................................ 43

42 U.S.C. §1973 ...................................................... 41

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. §1973, et

s e q ......................................................................... passim

Ga. Code §34-610(a).............................................. 8

Ga. Code §34-702.................................................... 21

Ga. Laws of 1958, pp. 269, 279 ......................... 3

Ga. Laws of 1931, p. 400 ...................................... 11

Ga. Laws of 1911, p. 390 ...................................... 11

Ga. Laws of 1873, p. 226 ...................................... 40

Miscellaneous

111 Cong. Rec. 8295 .............................................. 42

111 Cong. Rec. 8296, 10456, 10453-54, 11402-05,

11744-46 (1965) .................................................. 44

U.S. Code, Cong. & Admin. News (1965) ........ 43

40 Cong. Globe 668 (1869) .................................. 47

38 Cong. Globe 1319 (1864) ................................ 49

S. Rep. No. 162, 89th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1965)............................................................... 44

H.R. Rep. No. 439, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965) 44

H.R. Rep. No. 227, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981) 45

Hearings on S. 1564 before the Com. on the Ju

diciary, United States Senate, 89th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1965)......................................................... 43, 44

Hearings on H.B. 640 before Subcom. No. 5 of

the Com. on the Judiciary, House of Reps.

89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965) ............................ 44

VI

tenBroeck, The Thirteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution, 39 Cal. L. Rev.

171, 180 (1951).................................................... 49

Young, The Negro in Georgia Politics, 1867-

1877, (Unpublished Thesis, Emory University

Library) (1955).................................................... 40

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

PROCEEDINGS BELOW

This action was filed in 1976 challenging the use of at-

large elections for electing county commissioners in Burke

County, Georgia, on the ground that they had both the pur

pose and effect of discriminating against Black voters and

candidates. The complaint was based on the Thirteenth,

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. §1973. (R. 176,

180) Trial occurred in 1978 after discovery was completed.

After reviewing all of the evidence, the District Court

concluded that “ the present scheme of electing county com

missioners, although racially neutral when adopted, is being

maintained for invidious purposes.” (J.S. 71a) The Court

found that Blacks were “ desperate to play a meaningful

role in their local government,” that the commissioners

failed “ to view problems with racial impartiality,” that de

fendants had refused “ to make Blacks a viable part of the

county government,” that the defendants’ insensitivity “ to

the needs of the plaintiff class exists because of invidious

racial motivations,” that “ in the past, as well as in the pre

sent, plaintiffs have been denied equal access to the politi

cal process,” that “ Blacks are shut out of the normal course

of politics in this tightly-knit rural county,” that Blacks

have not had “ meaningful political input,” that the govern

ment has “ retained a system which has minimized the abil

ity of Burke County Blacks to participate in the political

system,” and that Blacks “ unfairly have been denied a role

in the political destiny of Burke County.” (J.S. 78a-96a)

Having concluded that at-large elections were maintained

for the purpose of discrimination, the District Court or

dered elections to be held under a district election plan.

(J.S. 96a-98a) That order was stayed by this Court pending

appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

2

On appeal, the Court of Appeals concluded that the Dis

trict Court “ correctly anticipated how the intent require

ment in [past] cases would be applied to voting dilution

cases . . . . It is clear . . . that Judge Alaimo employed the

constitutionally required standard in his evaluation of the

present case.” (J.S. 41a) After carefully reviewing the re

cord and Judge Alaimo’s opinion, the Fifth Circuit con

cluded that:

[Judge Alaimo’s] order leaves no doubt as to his conclu

sion that the at-large electoral system in Burke County

was maintained for the specific purpose of limiting the

opportunity of the County’s Black residents to meaning

fully participate therein. (J.S. 53a)

The Court of Appeals independently reviewed the evidence

and agreed that purposeful, intentional discrimination had

been proved.

Judge Alaimo’s evaluation of all of the relevant evidence

was thorough and even-handed. His conclusion that the

electoral system was maintained for invidious purposes

was reasonable, and in fact virtually mandated by the

overwhelming proof. (J.S. 53a-54a)

FACTS

Burke County Georgia, like many southern counties, has

a history rooted in slavery, discrimination, and plantation

life. But Burke County is significantly different than many

counties in the South. The resistance to equal rights for

Blacks has been worse there than in virtually all other

Georgia counties (T. 120-21), changes have been slight over

the past fifteen years (T. 746-47), and one finds there:

The fact that politics was perceived [as] a white man’s

game, the assumption on the part [of] white citizens that

black people should be excluded. (T. 551)

3

There has been no instance in the history of Burke

County where the government has voluntarily allowed

Blacks to progress politically or economically. Progress has

occurred only when there has been federal compulsion, and

it has occurred only over the fierce opposition of the entire

White community of Burke County. The resistance to

Black political rights has been especially pronounced. The

voter registration and election processes have been con

trolled to this day to minimize Black voting and political

activity. Before the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965,

Blacks were virtually eliminated from voting. (J.S. 71a-72a)

The voting process then was “ completely arbitrary.” (T.

554) Blacks who went to register were met with the “ nasty”

attitude of the officials (T. 152), others were made to drive

over and over many miles between their residence and the

one registration location in the County (T. 70-73, 93-96),

and they had to apply to register on one occasion and come

back later for a test. (T. 805) If you could not pass the liter

acy test, which was designed to exclude Blacks from the

ballot, South Carolina u. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966),

you would be subjected to Georgia’s infamous “ Question

and Answer” test. A significant number of Blacks tried that

test. (T. 812-13) It was designed to ensure their failure, as is

apparent from reading the questions. (Ga. Laws of 1958, pp.

269, 279) Not everyone had to take these tests or come back

to register, of course. “ Certain people were allowed to regis

ter.” (T. 554) Even some Blacks were allowed to forego the

“ technicalities” of registration, bypass the literacy test com

pletely, and be registered on their first trip, so long as they

had a White man vouch for them. (T. 312-14, 328)

With the passage of the Voting Rights Act, the county

commissioners first tried to eliminate all but one polling

place (PI. Ex. 11, T. 42) since the County’s impoverished

Black residents would then be unable to get to the polls to

vote. (J.S. 86a) Voter registration was limited to one day,

with a short Saturday morning time as well. (PI. Ex. 7, 10,

T. 39, 41) The Saturday registration period was later elimi

4

nated (PI. Ex. 197, T. 200) without approval under Section

5 of the Voting Rights Act. (PI. Ex. 276, T. 662) Although

Black registration increased, no polling place was ever ad

ded to accommodate Blacks. The one polling place change

that has occurred since 1965, moved the location further

from the Black community. (T. 687) Armed White police

and sheriff's men patrol the polling places on election day,

which Blacks see as a “ threat because they have always

been a symbol of injustice to most Blacks.” (T. 689, 736-37)

The county government rarely allows a Black to work as a

poll official, and never in a position of responsibility. (R. 56,

414-22, T. 28-29) Whites tried to stop one Black leader

from voting because his city taxes were allegedly not paid

(T. 741, 758-59), although there is no legal authority for

that in Georgia.

To this day, voter registration has been made as difficult

in Burke County as possible. The effect has been predict

able. Even with the salutary result of the Voting Rights

Act, Blacks are still only 38% of the registered voters in the

County (J.S. 72a), Whites are 62% of the registered voters,

and Whites are registered at a “ rate” 50% higher per capita

based on voting age populations.1 By comparison, defen

dants’ expert witness, Dr. Ira Robinson, testified by deposi

tion that Blacks have been registered at nearly the same

rate as Whites “ in most places in the South” since 1968.

(Robinson Depo. 9, T2 257)

For years, the County allowed voter registration only at

the courthouse, which is a “ symbol of injustice” to Blacks.

1 The preliminary 1980 census report indicates that Blacks are 53.7%

of the County’s population, but many Blacks leave Burke County when

they are adults because it is “ an undesirable place for Blacks” (J.S. 83a

n.18), so the voting age percentage is lower. That exact figure is not yet

available in the 1980 census, but assuming the ratios of older Blacks to

younger Blacks, and older Whites to younger Whites, is about the same

as in the past censuses, Blacks are 47.6% of the total voting age popula

tion. (PI. Ex. 59, T. 66)

5

(T. 676). It is where a black man could be lynched (T. 244),

where no Black has ever worked, other than as maid or

janitor (T. 298-99), where no Black ever held elected office,

and where a Black citizen cannot even expect fair treat

ment from the local courts. (T. 750) The vestiges of segre

gation are literally everywhere in the courthouse. (J.S. 77a-

78a; T. 747-48) Blacks do not feel welcome at the court

house, for obvious reasons. The most educated and outspo

ken Blacks in Burke County still feel anxious when they

have to go there. (T. 676) The District Court commented on

one witness’s testimony:

[If] they keep the courthouse as a central place of regis

tration, that fact alone will discourage blacks attempting

to register because of the history of the courthouse as be

ing a symbol [of] repression. (T. 557)

Rural Blacks are “ most reluctant” to go to the courthouse

to vote, they expect to be “ antagonized” if they go there,

and they are “ in fear.” (T. 152-53).

Aside from the psychological deterrent, the use of a single

registration site in an area as large as Burke County (which

is 832 square miles and about two-thirds the size of Rhode

Island (J.S. 91a)), inevitably excludes Blacks from registra

tion. Defendants’ expert, Dr. Robinson, testified that he

was “ shocked” by the number of families that had no

automobiles. (Robinson Depo. 39) Eighty-two percent of

these families are Black. Id. at 12-13.

By comparison, the City of Waynesboro—which is the

county seat—has three registration sites to conduct its sep

arate voter registration. The sites are more convenient to

Blacks. (T. 757-58) The City covers less than one percent of

the area of the County. It added its two additional sites af

ter a consent judgment finding unconstitutional its at-large

elections. (PI. Ex. 83A, T. 633)

6

Blacks asked for ten years for a registration site in each

of the 15 voting districts. (T. 733-34, PI. Exs. 197, 198) The

County lied to them and said it was illegal to register voters

anywhere but at the courthouse, and Blacks had to ask the

Secretary of State to intervene. (T. 733-34) Two years

before trial, three additional sites were finally approved,

technically. Even this token response was more form than

substance. The sites were opened only for a few days before

the 1976 election. The chief registrar, Metts McNair, stated

“ that will give people four days to register. They can do it

in that length of time if they really want to.” (PI. Ex. 99, T.

639)

In fact, even this nominal announced registration did not

exist for Blacks. A White man by the name of Butler was

named the deputy registrar in Gough, a predominantly

black area of Burke County. When Blacks tried to register

there, Woodrow Harvey testified that Butler told them:

[He] didn’t know anything about the folks that were sup

posed to register. He said he had not been given any cards

and he had not been notified that he was going to register

people at his store. (T. 319-20)

The next day, Mr. Harvey’s wife also went to see Butler.

And she went up to Mr. Butler’s store, he replied to her

that he didn’t know anything about any cards and he had

not been told anything about it. (T. 320)

When Mr. Harvey asked McNair about this, McNair gave

him the run-around. (T. 321)2 At trial, McNair testified

that Butler “ didn’t understand the process” (T. 952), al

2 Mr. Harvey testified:

Q. Did you speak to him about registration?

A. He said if we were going to support a certain candidate, we had to

have a lot more people to support him if we expected to get people

registered in the City of Gough, that we had to have more people

7

though all Butler had to do was sign the card once it was

filled out. McNair also testified, contrary to Butler’s repre

sentations to Blacks, that he did in fact take cards to But

ler. McNair then testified that he took the cards back from

Butler in order to give him some of a different color. Mc

Nair was unable to suggest any excuse for that switch since

the cards were the same, regardless of color. (T. 952)3

In soliciting Butler to serve as a deputy (T. 954), McNair

refused the enthusiastic offers of Blacks to serve as deputy

(T. 724, 955-56), he overlooked a Black store owner in the

area who is civically active (T. 953-54), and he continued

the historic refusal of Burke County to ever appoint a sin

gle Black deputy registrar. (T. 677) The defendants’ wit

nesses could offer no reason other than race, of course, for

that fact. (T. 954-56) Blacks had even volunteered to serve

as deputies without pay since the County first gave them

the excuse that they had no money to pay for deputies, and

since this had been done in other Georgia counties. (T. 724)

By comparison, the County eagerly appropriates funds to

hire additional employees in order to purge voters. (PI. Ex.

257, T. 660, 818-20)

The District Court and Court of Appeals properly found

that the right of Blacks to vote was directly denied in

Burke County, and that this “ overt conduct was taking

get out and vote, that Mr. Butler didn’t understand how to handle

the cards.

Q. Did he say anything else about Mr. Butler’s handling the cards?

A. He didn’t think he was capable o f handling them.

Q. My next question is, then why would he give him the cards, if he

were incapable of handling them? Was there any response to that?

A. He didn’t have any response. (T. 321)

3 McNair testified:

Q. Did you know what the difference was, if any, between the white

card and the blue card or any other color?

A. No, sir, I didn’t. (T. 952)

8

place even at the time the present lawsuit was filed.” (J.S.

44a, 81a)4

The state-wide laws of Georgia are also designed to mini

mize voter registration because they allow registration only

at fixed sites, which precludes mobile or house-to-house

voter registration. Ga. Code §34-610(a). Defendants’ own

witness admitted that there would be no practical problem

in conducting house-to-house registration in Burke County

(T. 815), and the evidence was undisputed that this restric

tion particularly hinders Blacks. (T. 677)

For local elections, Burke County has been a one party

county since Reconstruction, and Democratic nominees in

variably win. (J.S. 87a) Although the Democratic White pri

mary was struck down by this Court 38 years ago, Smith v.

Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944), the Burke County Demo

cratic Party remains the “ party [of] elimination of black

people in any office.” (T. 566) Of the twenty-four members

of the county governing body of the Democratic Party, only

one was Black (J.S. 50a), and he was unable to ever attend

a meeting because they were conducted during business

hours when he worked. (T. 438, 532-33, 914)

The District Court found that the segregated Democratic

Executive Committee plays an important role in local polit

ics. (J.S. 87a) That should be obvious since the party’s

nominees invariably win local elections, the Committee

members are the leading party members in the County, and

4 The slight expansion of voter registration, by the addition of three

sites, occurred only after “ friendly persuasion” by the District Court.

(J.S. 44a-45a n.13) While the appellants now suggest otherwise (Brief of

Appellants at 32), they never challenged this finding as clearly erroneous

below. Their statement of the events ignores the fact that the registra

tion sites were not actually made operative when they claim, they were

only open for several days initially, Blacks were not even allowed to reg

ister at one of the sites, and the sites had not been permanently ap

proved even by 1978. (PI. Ex. 197, 198).

9

elected officials almost always come from that group. Every

elected official who was asked at trial testified that he was a

member or officer of the Burke County Democratic Com

mittee. (T. 437-39, 474, 532, 880, T2 98-99, 137-38)

The Democratic Executive Committee has always oper

ated as a self-perpetuating “ club.” Members are either ap

pointed to vacancies by the other members (T. 437-39),

often taking their fathers’ position (T. 437, T2. 150), or

they are solicited by the members to run for election, inva

riably without opposition. (T. 913) The Democratic Com

mittee is virtually unknown in the Black community. (T.

692) Until recently, the Democratic Party conducted the

primary elections in the County. (T2 99) The Party still

handles the qualifying process for individuals who want to

run for its executive committee posts, and for individuals

who want to run in the primary to seek nomination for pub

lic office. (T. 884, 894-95) The procedure for qualifying to

run in the democratic primary is a virtual secret. As the

party chairman testified, he “ can tell them how it is done”

if anyone asks how to qualify. (T. 889-90) They would

“ have to see the secretary of the Democratic executive com

mittee.” (T. 884) Blacks would have no idea who to ask,

however, since they are excluded from the Democratic

Party, and few have even heard of the Executive Commit

tee. (T. 692) The Committee has published short legal ad

vertisements that announce elections, but they are hardly

designed to give any real public notice of the elections or

qualifying process. They are little formal ads contained

among foreclosure notices and the like, and, as expected,

Blacks have not seen the ads. (T. 737, 894, D. Ex. 16, 17, T2

262) The Committee has ignored state and national party

rules on fair representation, and it received no input from

Blacks when it set up districts for electing its members in

1976, as required by State rules. (J.S. 87a-88a, T. 890-93)

The districts adopted by the Committee all had White vot

ing majorities. (T. 534-42, 891-92)

10

There are other reasons why Blacks are not registered in

Burke County, each rooted in past and present discrimina

tion and racial oppression. Blacks still have a tremendous

amount of fear, both of physical harm and of economic re

taliation, that might be experienced were one to enter the

“ white man’s game” of politics. In the few years before this

case was filed, Black people were shot at in Burke County

for seeking equal rights (T. 113, 125-26, 134, 682-83), they

received bomb threats and harassing phone calls, and they

were the subject of physical harassment. (T. 206-07, 671-73,

684) Appellee Herman Lodge, received “ some very nasty”

phone calls simply because this case was filed. (T. 672-73)

Blacks must operate virtually “ in secret” to avoid the possi

bility of reprisal for political activity. The Burke County

Improvement Association cannot maintain membership

records for fear of reprisals if they were discovered. (T. 670,

709)5 Some Blacks still fear their ballot is not secret be

cause of past practices of White voting officials. (T. 689-91)

Blacks in Burke County suffer a precarious economic ex

istence that is “ in part caused by past discrimination.” (J.S.

83a) Their poverty, the fact that Whites control nearly all

the money and jobs in the County, and the history of severe

oppression leaves many Blacks afraid to simply register to

vote. They fear repercussions they cannot afford.6 Fear has

6 One witness testified:

Well, we did not keep membership records because of the fact that

a lot of people in there would be vulnerable, I guess, to reprisal, and

they were afraid to, you know, to help but, afraid because of certain

positions, that is, the teachers were real vulnerable and in a real vul

nerable position during this period. (T. 670)

6 One witness testified:

There was fear in regard to registration . . . . [T]he black popula

tion, o f course, o f Burke County was a population which had [a] great

degree of dependency which is a political thing throughout the plan

tation society, growing out of the low income, the under-employment

and such phenomenon as that, as well as their vulnerability to white

11

always been pervasive in Burke County, and it remains so

to this day. (T. 115, 120, 126, 134, 136-37, 152-53, 177-78,

551-53, 555, 670-77) Their poverty has formally excluded

them from office since there has been a “ freeholder” re

quirement to serve as county commissioner since 1911. (Ga.

Laws 1911, p. 390; Ga. Laws 1931, p. 400; J.S. 65a n.2, 75a)

Both plaintiffs’ and defendants’ witnesses suggested that

the depressed Black educational levels also contributed to

their under registration, and lack of access to the political

process. (T. 675-77, 912) That is obviously a product of dis

crimination, as the defendants concede. (T. 912)

The at-large election device itself directly minimizes

Black political activity. Since blacks cannot win in a

county-wide election, there is no reason to run, and they are

further alienated from the political process. There is little

reason to vote since the choice among the white candidates

is just a matter of choosing the “ lesser of two evils.” (T.

694)

The county commission controls public affairs in Burke

County by appointing individuals to many boards, authori

ties, committees and other offices, including the elections

board. Blacks are rarely appointed (R. 57, 88-94, T. 30, J.S.

78a), and when they are, federal funds and Title VI of the

employers and what have you. And the apparent acceptance by whites

of the behavior towards blacks o f intimidation by whites towards

blacks . . . .

They would have this feeling of intimidation because of their vulner

ability in terms of jobs as time went on and because of welfare depen

dency. (T. 552)

Another witness testified:

Now, there is fear of economic reprisal from you know, like people

say, well, I’m not going to vote because if I go to register, my welfare

check might be cut off. (T. 675)

12

1964 Civil Rights Act are the cause. (E.g., PI. Ex. 28) Defen

dants admit that there are no particular qualifications for

these positions, that Blacks are as equally qualified to serve

on these boards as Whites, and that there is no objective

reason why Blacks had not been appointed. (T. 399-402,

445, 478) The commissioners solicit Whites for the posts (T.

399-400), but overlook Blacks even when they seek appoint

ment. (T. 184) As one commissioner testified, Blacks are

not appointed because: “ That’s just the way things are.” (T.

296)

The exclusion of Blacks from these boards reflects the

firm refusal of the county commissioners to accord Blacks

any role in the political process. The boards are important

elements of government, they control many public opera

tions, and they make policy recommendations to the county

commissioners. (T. 401) The exclusion of Blacks from these

posts eliminates them from having input into the operation

of much of government. (T. 401-02) Their exclusion also

undercuts the opportunity for Blacks to participate in polit

ics. They are denied the public experience and exposure

that is an integral part of politics, and they are deterred

from political activity. One witness testified:

If it is not by appointment of black people to government

agencies, you remove from the activism of a community

just a special kind of reward. On that, I think it has an

effect upon the motivation to continue. (T. 565a)

The commissioners’ refusal to appoint Blacks tells the

entire community, both Black and White, that white

supremacy remains the policy of Burke County. It is “ a

general signal to the overall community about how their

affairs are to be conducted. . . . ” Id. As the District Court

concluded:

[The] Commissioners’ failure to appoint Blacks to the

committees and boards in sufficient numbers, or a mean

13

ingful fashion, is without doubt an unfair denial of access

of input into the political process. (J.S. 89a)

This evidence is very telling. Since the commissioners do

not feel Blacks are suited to hold these appointed positions,

they would hardly believe that Blacks should serve on the

commission itself.

Much other evidence is also telling about the attitudes

and motivations of the county commissioners. The entire

theory of the defense in this case, in fact, sounded like the

traditional justifications for White supremacy. The defen

dants and other public officials testified that it was not the

at-large election system or other government action that ex

cluded Blacks from the political process, but the fact that

Blacks “ do not take an interest in [politics]” (T2 166), that

they “ just have an interest in other things” (T2 169), that

they “ wouldn’t think that [Blacks] would be interested in

politics” (T. 799), and that Blacks do not register because

of “ indifference, don’t care about politics probably.” (T.

807) As the long-time state legislator from Burke County

stated:

They don’t seem to care about [the] political process, I

think they work hard and they worship and they’re very

interested in their relations and affairs, but they do not

take an interest in the political process. (T2 166)

To casually dismiss the historic elimination of Blacks from

the political process because they are “ indifferent,” is strik

ingly similar to the historic justification for White

supremacy—that Blacks are not political beings, and that

one would not expect them to be holding office or an ap

pointed position with a board. Since Burke’s Whites believe

that Blacks are not political beings, it is easy to rationalize

the exclusion of Blacks from the elective process.

The county commissioners, who are the most powerful

figures in the County politically (T. 215-16), demonstrated

14

their lack of concern for, and outright hostility towards,

Blacks’ civil and political rights in other ways. For example,

while the County employs Blacks only in menial positions

(J.S. 75a, 85a, 94a)— and while those Blacks who are em

ployed are usually hired only where there is federal money

and the compulsion of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act (J.S.

76a)—the county commissioners see no problem with this

situation. Commissioner Buxton testified that it was “ obvi

ously” the custom to rarely employ a Black person in

county government, and “ that that has been the situation

during the last eight years during the time that [he has]

been County Commissioner.” (T. 299) Commissioner

Marchman testified that the County doesn’t “ have any hir

ing policy” (T. 240), that they have never issued any “ pol

icy suggesting that Blacks be hired equally” because they

“ never have realized a problem in that area,” and he didn’t

“ see any problem . . . in terms of black employment . . .

with the County Government.” (T. 241)

Commissioner Marchman publicly stated that he “ could

care less” about having a swimming pool built at the public

park that is used by Blacks, although the White pool in the

County, which is now owned by the Jaycees, was given to

them by local government to avoid desegregation. (T. 232-

33) Two commissioners indicated their present belief in

segregation. (T. 257-59, 264-66, 279) Another testified that

desegregation might conceivably be accepted in Burke

County in another thirty years (T. 378), and another testi

fied that Blacks were referred to as “ niggers” in county

commission meetings. (T. 242-44) Apparently acknowledg

ing the absolute separation of the races in Burke County,

one commissioner testified that “ I can’t speak for them

[Blacks].” (T. 388) Another testified: “ I’m speaking as a

white person, but I don’t know what a black person thinks.”

(T. 309) This same man, when asked if this hindered his

ability to represent Blacks, testified: “ I don’t get you.” (T.

308-09)

15

The chairman of the county commission believes that

Black people inherently trust Whites more than they do

Blacks (T. 389-90), a notion that is part of traditional

White supremacist thinking. In the county courthouse,

which is under the control of the commissioners, the “ nig

ger hook” still hangs in place (J.S. 77a), the “ colored” and

“ white” signs have never been eradicated from the court

house restroom doors (J.S. 78a), the seating in the court

room remains segregated (T. 747-48), and the judicial pro

cess there hands out justice unequally. Crimes against

Blacks are barely punished, while crimes against Whites are

punished most severely. (T. 750) Notwithstanding the ex

ceptionally high degree of segregation and discrimination

that remains in Burke County, the commissioners believe

that nothing should be done about it. (T. 256-57) The com

missioners believe that nothing need be done about racial

discrimination because “ the Federal Government took care

of that.” (T. 299-300)

The commissioners’ adherence to segregation and support

of a status quo which refuses to accord Blacks full civil and

political rights, is naturally a reflection of the White com

munity that elected them. In Burke County, the Whites

have always been “ in tremendous horror of blacks coming

into power there” (T. 115), the changes from the old pat

terns and attitudes of segregation have been slight over the

past fifteen to twenty years (T. 213, 562), and Whites have

vehemently opposed every effort by Blacks to move for

ward. The battle over equal education is typical. Before this

Court’s 1954 desegregation decision, Black education was

dramatically inferior. The per student value of books and

teaching aids in the Black schools was one-tenth that in the

W’hite schools, the per student plant maintenance and oper

ating budget for the White schools was thirty times that in

the Black schools, the per pupil investment in White

schools was ten times that in the Black schools (PI. Ex. 278,

pp. 2, 3, 14, 15, 16, & 17, T. 662), and Blacks attended one-

room schoolhouses that contained grades one through seven

16

in a single room. The facilities were “ vastly different” for

Whites and Blacks. (T. 666) Until the early 1960’s, the

County closed the Black schools down until mid-October to

ensure that Blacks would be available to pick cotton for the

White farmers. (T. 667)

In the 1960’s the Burke County delegation to the State

commission on school desegregation “ presented the most

overwhelming vote [of all the delegations] in favor of . . .

closing public schools” to avoid desegregation (PI. Ex. 126,

T. 643). The county officials were unanimous that Burke

County “ would never integrate” id., the county commis

sioners resolved that there should be a private school to

avoid desegregation (PI. Ex. 31, T. 48), and they called

upon the government to pay tuition “ to the parents who

send their children to Burke Academy, Inc.” (PI. Ex. 32, T.

49). The County received national attention for its vehe

ment response to Brown. (PI. Ex. 128, T. 643) When a

school desegregation suit was filed in 1968, the chairman of

the board of education announced that the schools would

remain segregated at least until some order “ by the Court,”

and the county commissioners announced that they were

“ legally and morally obligated” to pay attorneys’ fees in de

fending the segregated system. (PI. Ex. 89, T. 635)

Because of the extreme racial hostility in Burke County,

freedom of choice was a complete failure there. Not a single

White went to a Black school, and very few Blacks had the

courage to cross over. (PI. Ex. 147, 226-28, T. 647) Of those

that did, one was nearly assassinated when she lay sleeping

in her bed at home. (T. 133, 124-26, 134, 682-83) Only one

White person in the entire County supported desegregation,

and he was shunned and harassed because of it. (T. 206-07)

The school board tried to avoid full desegregation by mak

ing all Black schools vocational schools, all White schools

college prepatory, and tracking the students based on pre-

school-age tests. (PL Ex. 156-57, T. 648)

17

The private Edmund Burke Academy was begun to avoid

desegregation. The local bar association volunteered its ser

vices to the Academy as a “pro bono” project. (PI. Ex. 129,

T. 644) Its list of incorporators included most of the public

officials in the County, including some of the appellants in

this case. (PI. Ex. 131, T. 644, 470-75) The Academy began

operations with a building given it by the County Board of

Education (PI. Ex. 132, 215, T. 645, 56), which still allows

the Academy to use its facilities so long as the federal gov

ernment does not interfere. (PI. Ex. 173, T. 650) The State

provides books (T. 429-30), the county commissioners per

sonally serve on the Board of Directors and send their chil

dren there, and appellant Rogers has given the school six

acres of land for a nominal sum. (T. 266, 375-76, 470-77,

486-87, PI. Ex. 211, T. 655) As the local newspaper editori

alized about the Burke Academy:

[We] are no longer cursing the Supreme Court, we are

now standing to one side and watching them butt their

heads against a stone wall. (PI. Ex. 128, T. 643)

The educational picture has not improved today. Most

Whites who can afford the tuition still attend Burke Acad

emy (T2 88, PI. Ex. 95, T. 637), the school superintendent

still rails about the “ assinine” desegregation decisions of

this Court (PI. Ex. 237, T. 658), many activities are no

longer carried on in the public schools since integration (T.

698-99), and private facilities such as the local White coun

try club are no longer available for the students to use. (T.

697-98) As the District Court found:

[The] unbroken history of an inferior formal education

has had and does now have a strong tendency to preclude

Blacks’ effective participation in the political process.

(J.S. 84a-85a)

The fierce resistance to school integration typifies race re

lations in Burke County. Unlike most counties in the South,

no biracial committee was formed to deal with racial

18

problems (T. 420), Blacks and Whites had never even met

before 1967 to talk about racial problems, (T. 117), and

there was much noncompliance with federal desegregation

laws. In the 1970’s, only one doctor in Burke County had

desegregated waiting rooms, the county hospital was still

segregated, the County Health Department treated Blacks

so badly that some turned down its free services (T. 194-

200, 216-17, PI. Ex. 223), and White doctors refused to cer

tify Black patients as disabled when they sought disability

benefits. (T. 123-24) When the 1964 Civil Rights Act was

passed, the owner of the one downtown lunch counter

closed his business rather than integrate (T. 684), the movie

theater remained segregated a decade after the 1964 Civil

Rights Act, and when Blacks finally did try to leave the bal

cony and sit downstairs, state troopers had to intervene. (T.

685-86, 732-33) There are two laundromats in Burke

County, today, one Black and the other White. The White

one is situated prominently one half block from the County

Courthouse (T. 321-22), and Blacks are allowed there today

only if they go to wash a White person’s clothes. (T. 321-22,

332-33, 740)7 “ Whites only” signs are displayed openly on

houses for rent (T. 334), deeds are sometimes still filed re

flecting whether the property is Black or White (PI. Ex.

212, 655), and poor Whites will not even avail themselves of

7 Just a few days before trial, a black woman entered the white laun

dromat. She testified that:

[The man in charge] stretched his arms out then and said, don’t you

see that sign on the door? I said, yes, I see that it says private. So,

what does that mean? He says, that means if you’re colored, you can’t

use the wash house. There’s one on Eighth Street, one on the other

side of the railroad tracks, why don’t you go over there and use that

one. And I said I prefer to use this one. So then he said, the way you

colored people acted a long time ago, we were able to deal with you,

but now you’re pulling all kinds of things and stuff. So, I said, if I

wash my clothes here what will happen and he said, if you just hang

around here until the boss man gets back, you will see what will hap

pen to you. (T. 333) (emphasis added)

19

government assistance if it means associating with Blacks.

(T. 141-42, 340)

Segregation in Burke County remains remarkably en

trenched. All private organizations are segregated (T. 276-

77, 233-37, 279-83, 296-97, 309-11), there is no cross-race so

cial mixing (T. 238-39), and Blacks do not travel in White

areas even though Burke County is rural and Black and

White neighborhoods are close. (T. 323).

Segregation has a tremendous impact on politics in Burke

County. It nurtures the pattern of racial bloc voting which

ensures that Blacks cannot win at-large elections. (J.S. 46a)

Blacks are entirely foreclosed from participating in the po

litical and social processes which determine who the politi

cal leaders will be, Whites personally know prospective

White candidates, and “ [w]hen this factor is combined with

the virtual segregation of all social, religious, and business

organizations . . . , the result obtains that Blacks are shut

out of the normal course of politics in this tightly-knit rural

county.” (J.S. 88a-89a) As the Court of Appeals concluded:

“ Person-to-person relations, necessary to effective

campaigning in a rural county, [are] virtually impossible on

an interracial basis because of the deep-rooted discrimina

tion by Whites against Blacks.” (J.S. 49a-50a) Burke

County is a “ continuation of the old southern pattern of

keeping Blacks out of politics.” (T. 587)

The District Court found that Blacks are completely ex

cluded from the political process. The Court commented:

It is the Court’s impression that Blacks of Burke County

desire, and desperately need, to play a meaningful role in

their local government; to be able to work within the sys

tem, rather than to be forced to attack it from without.

The Commissioners have been singularly unresponsive to

this need. (J.S. 78a)

20

Blacks have been “ forced to attack [the system] from with

out” by court orders and economic boycotts.8 Blacks were

excluded from the grand juries and trial juries in Burke

County until a federal court order was entered in 1977. (J.S.

75a, PI. Ex. 82A, T. 632-33) Blacks were unconstitutionally

excluded from elections in the City of Waynesboro until the

at-large election system was eliminated by court order in

1977. (Pl. Ex. 83A, T. 633). Excluded from meaningful po

litical input by at-large elections, their sole voice has been

to organize economic boycotts. (T. 668-69).

It is clear that county-wide elections exclude Blacks from

political office. No evidence suggested that a Black could

get elected. The local state legislator, who is also the Secre

tary of the Democratic Committee (T2 137-39), admitted

that a Black could not be elected county-wide. He testified:

Q. . . . [Y]ou knew full well that Burke County would

never elect a black? You knew that, didn’t you?

A. Yes. . . . (T2 168)

There was no substantial evidence that at-large elections

served any other function in Burke County. One of the de

fendants’ witnesses was asked to compare district and at-

large voting in Burke County. The “ only reason” he could

think of to distinguish the two was race and a desire to pre

fer one race over the other.9 (T2 101-02) If the purpose of a

district system would be to give “ an unfair advantage” to

8 “ Blacks have been forced outside the local government for relief.

They went to the courts to seek school and Grand Jury integration

• • • > an<i to the streets to ‘agitate,’ as defendants have said, to get

lighting at the Davis Park Ballfield. Outside pressure had to come to

bear before the county budged.” (J.S. 81a)

9 Q. Do you have any preference yourself as between the present

system of countywide elections and the elections by the voters

only in a district of the county?

A. I would prefer it being like it is.

Q. Why is that?

21

Blacks — by allowing them some participation in the politi

cal process — maintaining at-large elections must certainly

have the purpose of denying Blacks that “ advantage.”

To determine whether there were any practical draw

backs to a district system in Burke County, two of the

county commissioners were asked what problems they

would face if they were drawing up a district election plan.

They saw none. They just testified that the districts would

have to have equal populations. (T. 422-24, 462) Commis

sioner Robert Webster testified that at-large elections

served no purpose in comparison to district elections.10

Some of the defendants’ witnesses attempted to offer one

justification or another for county-wide elections. They

were not convincing. Judson Thompson, a past commis

sioner and Chairman of the Democratic Party, testified that

it was impossible to draw districts with equal populations

in Burke County. (T. 883) Mr. Thompson’s testimony was

an apparent effort to fabricate a pretext for at-large elec

tions. It is easy to draw election plans with equal popula

tion districts, and neither plaintiffs nor defendants had any

difficulty in submitting district plans to the Court. (E.g., PI.

Exs. 300, 301)

Another witness suggested that there might be a problem

in drawing districts because they could cut across the mili

tia lines in the County. But the same witness admitted that

there were no problems where state legislative districts cut

across the militia district lines (T2 114), district election

plans could be drawn that would hardly deviate from the

militia districts (PI. Ex. 301), Georgia law allows for elec

A. Well, the only reason I can think of doing a district would be to

fix the districts at such gerrymandering which would bring

about an unfair advantage to one race. (T2 101-02)

10 Q. It is your testimony, isn’t it, that in the event the county was

divided into districts, it would not make any difference at all?

A. I think I’ve said that, yes. (T. 484)

22

tion districts to be modified so that they do not have to

correspond to militia district lines, Ga. Code §34-702, and

there were any number of other ways of accommodating a

change to districts.

Appellants offered testimony that county-wide voting

might avoid “ political deals and trades” in Burke County,

but these witnesses were not familiar with any of the dis

trict systems in operation in Georgia, and their testimony

was admittedly speculation. (T. 390-91, 451, 909-11) More

over, since Blacks would become part of the political pro

cess under a district system, since they would enjoy full po

litical rights and public office then, and since they would be

able to deal from an equal basis with Whites, there would

in fact be a new breed of “ political deals and trades” in

Burke County. Since Whites “ generally . . . have the same

interests” in Burke County (T2 141), the political dealing

the defendants fear must be solely what would occur be

tween Whites and Blacks. To justify at-large elections be

cause they preclude “ political dealing” in Burke County, is

virtually to admit that their purpose is to exclude Blacks

from the political process, to maintain the status quo of po

litical domination by Whites, and to eliminate any Black

voice in county government.

The District Court concluded that at-large elections were

maintained in Burke County for invidious purposes. Judge

Alaimo found that voter confusion would not be a problem

with district elections, and he concluded that it was so sim

ple to institute district elections that it could be done in a

few weeks time. (J.S. 98a) The Court noted that the Burke

County Democratic Party elected its governing board from

districts, that this district scheme created no problem what

soever, and that other local governments elected by dis

tricts in Georgia appeared to function perfectly well. (J.S.

91a) The Court concluded that “ defendants are heedless of

the needs of the Black community” (J.S. 95a), that Burke

County’s representatives “ have retained a system which has

23

minimized the ability of Burke County Blacks to partici

pate in the political system” (J.S. 90a), that the “ Commis

sioners have been singularly unresponsive to this need” of

Blacks to participate meaningfully in local government (J.S.

78a), that the insensitivity of defendants to the needs of the

plaintiff class “ exists because of invidious racial motiva

tions” (J.S. 82a), and that the at-large election process in

Burke County “ has been subverted to invidious purposes.”

(J.S. 90a) The Court of Appeals affirmed in all regards,

stating that:

Judge Alaimo’s evaluation of all the relevant evidence was

thorough and even-handed. His conclusion that the elec

toral system was maintained for invidious purposes was

reasonable, and in fact, virtually mandated by the over

whelming proof. (J.S. 53a-54a)

The events which transpired after the trial court’s judg

ment dramatically confirm Judge Alaimo’s conclusion. A

special election was ordered for November, 1978, and it in

cluded five districts with two that had a majority of Black

registered voters. One Black qualified to run in each of the

five districts, one White qualified in three of the districts,

and two Whites qualified in the other two. (J.S. 63a, 97a,

Stipulation Filed October 27, 1981) Although this Court

stayed that order before the election occurred, one of the

white candidates dropped out, before the stay, from each of

the two districts where there was another white candidate

running. (Stipulation, supra) This is the only instance in

the history of Burke County where one can see what hap

pens under district elections, as compared to at-large elec

tions. Under districts, Blacks are involved in the political

process and run for office. Under an at-large system, none

are even on the ballot. Even more telling is the manipula

tion by the White candidates to minimize the possibility of

a Black being elected. The obvious explanation for the two

Whites dropping out of the election, is that they did not

want to split the White vote between themselves and the

24

other White candidates, which would have given the Black

candidates a good chance of election. Whites in Burke

County would rather forego public office themselves, than

make it possible for Blacks to get elected.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The District Court and the Court of Appeals concluded

that at-large elections were maintained in Burke County for

the purpose of discriminating against Blacks. That conclu

sion was based on a tremendous amount of evidence from

which the lower courts inferred a discriminatory purpose.

The evidence was mostly circumstantial, and circumstantial

evidence is sufficient to prove motive in a Fourteenth

Amendment case, just as in all other areas of law where mo

tive is relevant. The evidence here is more than sufficient to

support the judgment below, and the findings are surely not

clearly erroneous.

Appellees also rely on Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965 as an alternative basis for affirmance. Section 2 ap

plies in cases where districting schemes are challenged, and

it is not necessary to prove intentional discrimination in a

Section 2 case. It is sufficient, at the very least, to prove

that the challenged system perpetuates the effects of past

discrimination.

Appellees also rely on the Thirteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments. Neither requires proof of a specific intent to

discriminate. The Thirteenth Amendment is broader than

the Fourteenth Amendment in a number of ways, most im

portantly because it reaches purely private conduct. The

Fifteenth Amendment necessarily provides a stronger cause

of action for a plaintiff in a vote dilution case, than does the

Fourteenth Amendment, because the Fifteenth Amendment

applies specifically and exclusively to voting. Any other in

terpretation of the Fifteenth Amendment would render it

meaningless.

25

ARGUMENT

I. Purposeful Discrimination Under the Four

teenth Amendment Was Proved In This Case

A. The Evidence of Intentional Discrimi

nation In This Case Entirely Supports

The Lower Courts’ Conclusion That At-

Large Elections Are Maintained In

Burke County For The Purpose of

Discrimination.

The issue in this case is straight-forward. It is whether

indirect evidence will support a court’s conclusion that an

election procedure is maintained for discriminatory reasons,

or whether direct proof of discriminatory intent is required.

The Court of Appeals held that indirect proof was

sufficient.11

[I] t is unlikely that plaintiffs could ever uncover direct

proof that such system was being maintained for the pur

pose of discrimination . . . . Circumstantial evidence, of

necessity, must suffice, so long as the inference of discrim

inatory intent is clear. (J.S. 8a)

This Court has expressly held that circumstantial evi

dence may be used in the overall inquiry. Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429

11 The Court of Appeals reasoned:

We think it can be stated unequivocally that, assuming an electoral

system is being maintained for the purpose of restricting minority ac

cess thereto, there will be no memorandum between the defendants,

or legislative history, in which it is said, “ W e’ve got a good thing go

ing with this system; let’s keep it this way so those Blacks won’t get to

participate.” Even those who might otherwise be inclined to create

such documentation have become sufficiently sensitive to the opera

tion of our judicial system that they would not do so. Quite simply,

there will be no “ smoking gun.” (J.S. 8a n.8)

26

U.S. 252, 266 (1977). As Justice Powell wrote in Arlington

Heights, it would be an “ extraordinary” case where a legis

lator would take the stand to testify about his intentions.

Circumstantial evidence is therefore necessary, and courts

should focus largely on extrinsic factors, as this Court indi

cated in Personnel Administrator v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256,

279 n.24 (1979).12 In all other areas of the law, evidence of

the sort offered here would be far more than necessary to

support the judgment. The rule on sufficiency of the evi

dence should be no different in this case. Compare FPC v.

Florida Power & Light, 404 U.S. 453, 468-69 (1972);

Michalic v. Cleveland Tankers, 364 U.S. 325, 330 (I960);

Rogers v. Missouri Pac. R. Co., 352 U.S. 500, 508 n.17

(1957).

The District Court here complied fully with this Court’s

purposeful discrimination decisions. After reviewing all of

the evidence, the Court concluded that “ the present scheme

of electing county commissioners, although racially neutral

when adopted, is being maintained for invidious purposes.”

(J.S. 71a) The Court found that Blacks were “ desperate to

play a meaningful role in their local government,” that the

commissioners failed “ to view problems with racial impar

tiality,” that Blacks are given the “ run around” once they

make their needs known, that defendants had refused “ to

make Blacks a viable part of the county government,” that

the defendants’ insensitivity “ to the needs of the plaintiff

class exists because of invidious racial motivations,” that

“ in the past, as well as in the present, plaintiffs have been

denied equal access to the political process,” that “ Blacks

are shut out of the normal course of politics in this tightly-

knit rural county,” that several factors, “ all of which seem

to be related to past discrimination, operate unfairly to ex-

12 “ Proof of discriminatory intent must necessarily usually rely on ob

jective factors . . . . The inquiry is practical. What a legislature or any

official entity is up to may be plain from the results its actions achieve,

or the results they avoid.” 442 U.S. at 279 n.24.

27

elude Blacks from the normal course of personal contact

politics in Burke County,” that Blacks have not had “ mean

ingful political input,” that the government has “ retained a

system which has minimized the ability of Burke County

Blacks to participate in the political system,” and that

Blacks “ unfairly have been denied a role in the political

destiny of Burke County.” (J.S. 78a-96a)13

Although the District Court did not have the benefit of

this Court’s decision in City of Mobile u. Bolden, 446 U.S.

55 (1980), the Court followed the earlier intent decisions.

As the Court of Appeals stated:

A court that correctly anticipated how the intent require

ment in past cases would be applied to voting dilution

cases, as in Bolden, could correctly interpret and apply

the law, without the benefit of [Bolden]. This is precisely

the type of foresight demonstrated by Judge Alaimo in

the present case. . . . It is clear . . . that Judge Alaimo

employed the constitutionally required standard in his

evaluation of the present case. (J.S. 41a)

Judge Alaimo discussed and considered Zimmer kinds of

evidence, as he is authorized to do under Mobile, but he

made findings of intentional discrimination that were based

on the entire record. After carefully reviewing the record

and Judge Alaimo’s opinion, the Fifth Circuit concluded

that:

13 Commenting on the county commissioners’ refusal to allow Blacks

any meaningful participation in the political process, the refusal to ac

knowledge other legitimate interests and needs of Black citizens, and the

commissioners’ dedication to preserving an all-White political structure

with the at-large election system, the Court found: “ The Commissioners’

lack of responsiveness is merely an extension of a culture which could

view the vestiges of slavery with unseeing eyes. Such indifference attests

to the Commissioners’ realization of the Blacks’ political impotence, both

individually and collectively.” (J.S. 95a)

28

[Judge Alaimo’s] order leaves no doubt as to his conclu

sion that the at-large electoral system in Burke County

was maintained for the specific purpose of limiting the

opportunity of the County’s Black residents to meaning

fully participate therein. (J.S. 53a)

The Court of Appeals independently reviewed the evidence

and agreed that purposeful, intentional discrimination had

been proved. The Court characterized the evidence of in

tentional discrimination as “ overwhelming.” (J.S. 54a)

The Fifth Circuit followed Justice Stewart’s opinion and

rejected the Zimmer test as a categorical way of determin

ing the constitutionality of at-large elections. In rejecting

Zimmer, Justice Stewart wrote that the trial court must fo

cus on the ultimate factual issue—what is the purpose that

motivates the adoption or retention of the scheme? The

Court of Appeals plainly recognized this requirement and

the limits of Zimmer evidence.14 (J.S. 35a)

At the same time, the Court of Appeals held that the

Zimmer criteria might have some evidentiary relevance in

determining purpose, as the Mobile plurality recognized,

but that other criteria and evidence must be considered as

well. The Court held that the Zimmer criteria may provide

some evidence of intent, but they were “ not dispositive on

the question of intent.” (J.S. 39a) That is precisely Justice

Stewart’s view in Mobile. 446 U.S. at 73. The Court of Ap

14 The Court o f Appeals held that:

Though four Justices were satisfied with the Zimmer criteria [in

Bolden], five Justices clearly rejected the exclusive use of those crite

ria for inferring purpose or intent. We conclude that they rejected the

use of Zimmer criteria to the extent that [the Fifth Circuit], in

Bolden, presumed the existence of a discriminatory purpose for the

proof of some of those factors. We believe the Court rejected the use

of such a quantitative weighing approach, requiring instead an inde

pendent inquiry into intent. (J.S. 35a)

29

peals also followed the plurality opinion and held that the

Zimmer factors were relevant only insofar as they might

elucidate the basic question of purpose (J.S. 35a), and that

purpose must be decided “ only in light of the totality of the

circumstances.” (J.S. 40a)

In assessing the District Court’s opinion under the intent

test, the Court of Appeals concluded:

[A] careful reading of Judge Alaimo’s order leads us in

escapably to the conclusion that he made the type of in

dependent inquiry into intent that we have said is neces

sary. (J.S. 53a)

Thus, while the appellants’ Brief reads as if the Court of

Appeals willfully disregarded Mobile, appellants ignore the

conscientious effort of the Court to implement the Mobile

ruling. The appellants’ only real complaint here is with the

facts that have been found against them, but as the Court

of Appeals concluded after reviewing the record:

Judge Alaimo’s evaluation of all the relevant evidence was

thorough and even-handed. His conclusion that the elec

toral system was maintained for invidious purposes was

reasonable, and in fact, virtually mandated by the over

whelming proof. (J.S. 53a-54a) (Emphasis added).

As Chief Justice Burger has written, the Justices of this

Court should defer to the trial court when intentional dis

crimination has been found, even if they might “ have seri

ous doubts as to how many of the [defendants’ actions] can

properly be characterized as segregative in intent and ef

fect.” Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S.

449, 468 (1979). That rule is even more appropriate here

than in a school desegregation case, because the “ extremely

unique factual context for decision [puts the trial court] in

a far better position to evaluate the local political, social,

and economic realities.” (J.S. 40a) Such deference is espe

cially warranted in this case since the trial judge had served

30

as a county commissioner in another county, and he was

uniquely qualified to determine the intent issue here.

The appellants’ factual contentions should not be heard

here for another reason. They did not challenge any of the

findings as clearly erroneous in their appeal to the Fifth

Circuit, and they cannot be raised now. Moreover, any chal

lenge on the basis of the clearly erroneous test would be

frivolous. The circumstantial evidence of intent was not

merely substantial, it was overwhelming. (J.S. 54a)

The impact of the at-large system in Burke County is “ an

important starting point” in determining purpose. The im

pact here is “ stark,” so that evidence is particularly rele

vant. 429 U.S. at 266. Defendants admit that Blacks cannot

be elected county-wide (T2 168), and Blacks are deterred

from even running for office because of the impossibility of

winning. There has been an unbroken history of opposition

to political rights for Blacks. Virtually all Blacks were kept

from the ballot until the federal government enacted the

Voting Rights Act in 1965. The county commissioners then

tried to eliminate all of the polling places in the County but

one, voter registration was made inaccessible, county offi

cials lied to Blacks who sought additional registration sites,

courthouse registration alone was allowed until the federal

court pressured the County into adding additional sites,

and Blacks were getting the run around in the voter regis

tration process as recently as 1976. Blacks are not allowed

to serve as deputy registrars, and Blacks are not chosen to

work at polling places. Blacks are excluded from the Demo

cratic Party whose nominees invariably win local elections,

the local Democratic Party has ignored rules on fair repre

sentation, and the process for qualifying to run in the dem

ocratic primary is virtually secret.

Blacks are “ shut out of the normal course of politics” be

cause of the “ deep-rooted discrimination by Whites against

Blacks.” (J.S. 49a-50a, 88a-89a) Blacks fear reprisals should

31

they enter into the “ white man’s game” of politics, the ma

jor Black civic organization in the county cannot even have

a written membership list because of fear of reprisals, and

these cumulative fears are, unfortunately, the rational prod

uct of the very recent history of oppression, discrimination

and outright violence directed at Blacks.

Blacks are discriminated against in all phases of local

government. The county government rarely allows them to

serve on any of the public boards and authorities that oper

ate the government, Blacks were excluded from juries until

a federal court order entered in 1977, and they were uncon

stitutionally denied access to the electoral process in

Waynesboro, the county seat, until a court order entered in

1977. It is assumed in Burke County that Blacks should not

have a role in politics, Whites rationalize the exclusion of

Blacks on the basis that Blacks “ are just not interested” in

politics, and Whites have resisted desegregation in Burke

County as long, hard and successfully as anywhere in the

nation.

In determining purpose, the trial court considered a host

of other discriminatory laws passed by Georgia (J.S. 76a, R.

334-38), many of which are still on the books. The pattern

behind at-large elections is a telling factor in this case be

cause 18 counties in Georgia switched from district elec

tions to at-large elections after enactment of the Voting

Rights Act when Blacks began to vote. (R. 398-99) Con

versely, with the advent of the Black vote, no county volun

tarily switched to a district system. That pattern is cer

tainly some evidence of discrimination in the use of at-large

elections. Similarly, Georgia recently adopted the num-

bered-post and majority-vote requirements, which give the

majority White electorate in Burke County and nearly

every other Georgia county complete control of all commis

sion seats. Those laws were conspicuously adopted precisely

32

when Blacks began to vote in the 1960’s. (J.S. 65a n.2)15

The new 1976 Georgia Constitution readopted literacy and

understanding tests, Ga. Code §2-403, which are inoperative

solely because of the Voting Rights Act.

Much evidence was introduced concerning the racial atti

tudes of the White community and White public officials. It

showed a firm commitment to segregation, a belief that

Blacks were not political beings, and unyielding opposition

to equal rights for Blacks.

While this is only a part of the evidence that was intro

duced, it certainly supports the trial court’s finding that at-

large elections in Burke County are one more in a series of

many, many efforts to limit the civil and political rights of

Blacks. There was virtually no countervailing evidence

presented. The evidence of other purposes was unconvinc

ing, an apparent effort to fabricate a pretext. Moreover, as

this Court held in Arlington Heights, plaintiffs need not

show that the sole motivation was discriminatory, but just

that it be “ a motivating factor.” 429 U.S. at 265-66. The

finding of discriminatory purpose here is not clearly

erroneous.

It is clear in this case that Blacks attain a measure of fair

treatment and equality in Burke County only when the fed

eral government intervenes. That is no less true with the

electoral process than in any other phase of Burke County

life. Unless the federal courts intervene, Blacks will never

be allowed to participate fully in the political process. So

10 The change to majority vote and numbered post were approved

under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act by the Attorney General. How

ever, the United States later filed an action against the State of Georgia

contending that Section 5 approval had been obtained fraudulently be

cause the State had included them in a general recodification of the elec

tion code, and the United States had never been made aware of these

changes when it passed on the general recodification legislation. United

States v. Georgia, 436 U.S. 941 (1978).

33

long as the White politicians of Burke County are allowed

to determine the rules of the “white man’s game,” those

rules will be maintained to ensure that Blacks are excluded.

This Court has held that there is no constitutional viola

tion where a minority group loses elections because of the

normal “ give and take” of the political process. Whitcomb

u. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971). As this Court said in Fee

ney: “ It is presumed that ‘even improvident decisions will

eventually be rectified by the democratic process.’ ” 442

U.S. at 272. But where Blacks are completely excluded from

the political process, and where they are subjected to ongo

ing intentional discrimination in all aspects of public and

private life, then there is no “ give and take,” improvident

decisions cannot be rectified by the democratic process, and

judicial intervention is both necessary and appropriate.

Blacks did not just “ lose out” in politics in Burke County.

They have never been a part of the political process there,

they have no power to assert their interests, and they will

remain impotent absent judicial relief.

B. This Case Differs Significantly From The

Facts And Issues Presented in Bolden

Although plaintiffs satisfied the burden imposed by the