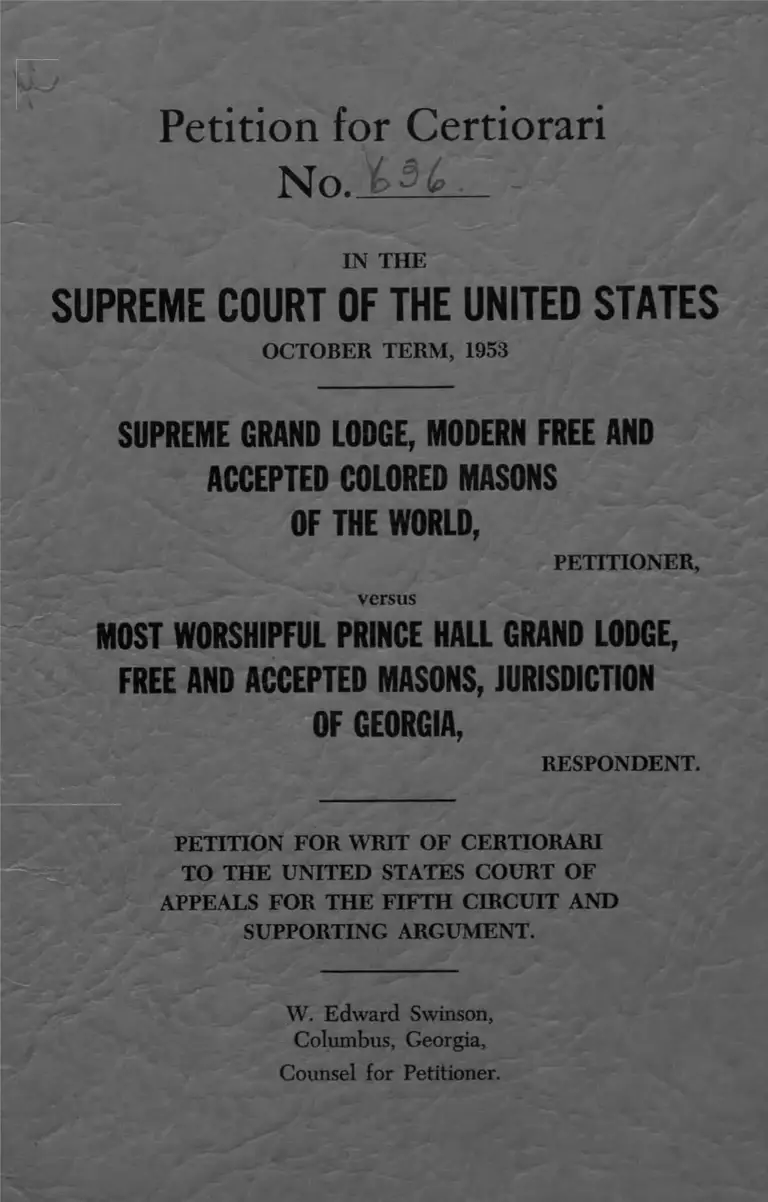

Supreme Grand Lodge, Modern Free and Accepted Colored Masons of the World v. Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Free and Accepted Masons, Jurisdiction of Georgia Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

March 10, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Supreme Grand Lodge, Modern Free and Accepted Colored Masons of the World v. Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Free and Accepted Masons, Jurisdiction of Georgia Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1964. 241c6960-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e8e35c57-e255-452e-8e89-5c685276805c/supreme-grand-lodge-modern-free-and-accepted-colored-masons-of-the-world-v-most-worshipful-prince-hall-grand-lodge-free-and-accepted-masons-jurisdiction-of-georgia-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed July 12, 2025.

Copied!