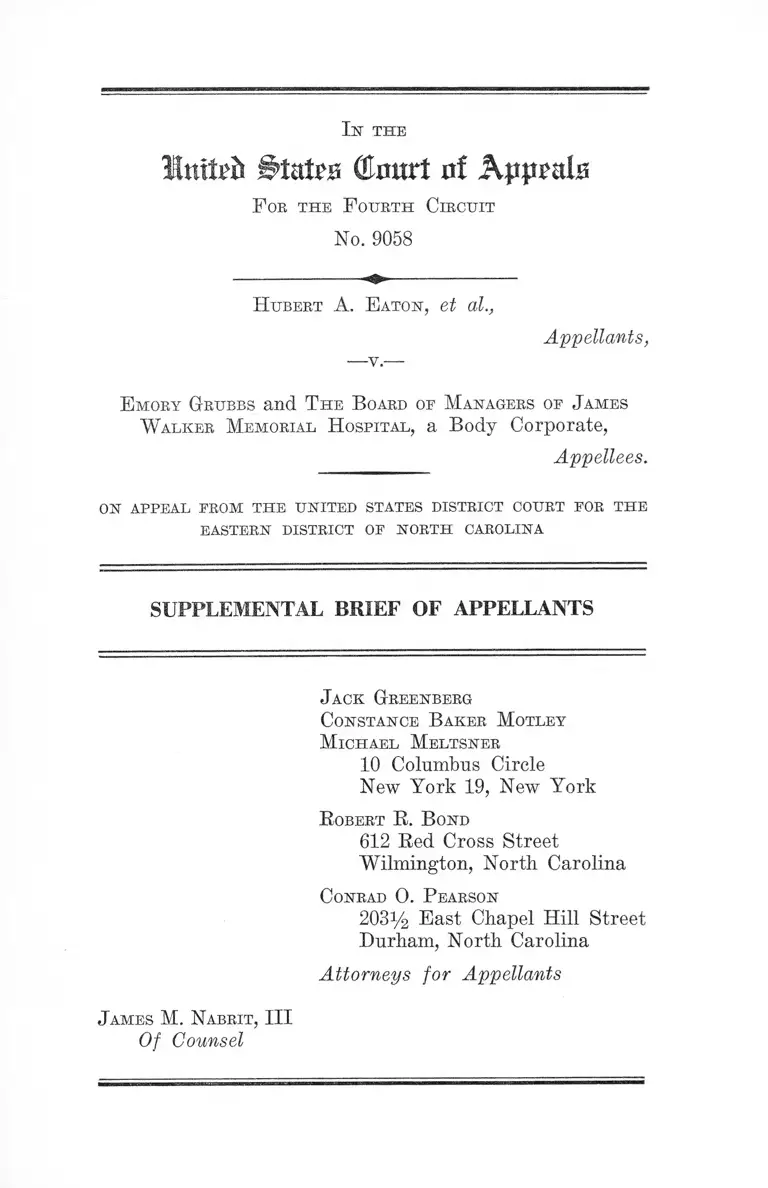

Eaton v. Grubbs Supplemental Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Eaton v. Grubbs Supplemental Brief of Appellants, 1963. 6ec63586-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e8f89469-f5ad-4640-a824-4eae5015d407/eaton-v-grubbs-supplemental-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Mmtvb (tart nf Appmla

F or the F ourth Circuit

No. 9058

In the

H ubert A. E aton, et al.,

Appellants,

E mory Grubbs and T he B oard of M anagers of J ames

W alker M emorial H ospital, a Body Corporate,

Appellees.

on appeal from the united states district court for the

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

Constance B aker M otley

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R obert R. B ond

612 Red Cross Street

Wilmington, North Carolina

Conrad O. P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Of Counsel

In the

In M Court of Appeals

F ob the F ourth Circuit

No. 9058

H ubert A. E aton, et al.,

Appellants,

E mory Grubbs and T he B oard oe M anagers of J ames

W alker Memorial H ospital, a Body Corporate,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Appellants file this Supplemental Brief pursuant to an

order of this Court of November 16, 1963 granting the par

ties leave to file sujjplemental briefs in light of this Court’s

decision of November 1,1963 in No. 8908, G. C. Simkins, Jr.,

et al. v. The Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, et al. 1

1. Appellants urged in their Brief pp. 13-18 that a rever

sionary interest in land in favor of government, restricting

hospital property to use “ as a hospital for the benefit of

the County and City . . . and in case of disuse or abandon

ment to revert to the said County and City” subjects the

hospital to the constitutional prohibition against racial dis

crimination. The decision of this Court in Simkins v. Moses

Cone Hospital (No. 8908, Decided November 1, 1963) ac

cepted and applied this principle. One of the significant

categories of “ state action” cited by the Court in Simkins

was the Hill-Burton Act reverter provision “ that if within

2

20 years after completion of a project a hospital is sold

to anyone who is not qualified to file an application there

under or is not approved by the state agency or if the hos

pital ceases to be ‘non-profit’ the United States can recover

a proportionate share of its grant to the hospital.” The

reverter in this case confers far greater control on govern

ment than the statutory reverter in Simkins. It is, for ex

ample, not limited to 20 years’ duration1 and the reverter is

conditioned on use of the hospital for the benefit of County

and City:1 2

“ To have and to hold in trust for the use of the Hos

pital aforesaid, so long as the same shall be used and

maintained as a hospital for the benefit of the County

and City aforesaid, and in the case of disuse or aban

donment to revert to the said County and City as their

interest respectively appear.”

The Court in Simkins cited with approval Hampton v.

City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320, 323 (5th Cir. 1982)

cert, denied sub nom. Ghioto v. Hampton, 371 U. S. 911

(reversionary interest held by government; racial discrimi

nation prohibited). Even the dissenters in Simkins took the

position that the type of reverter present here (and in

Hampton) was of greater significance than the statutory

reverter present in the Simkins case:

“ That provision [in Simkins], however, creates no in

terest in the facilities. It is not comparable to a right

of reverter retained by a public body. It simply creates

a limited and declining personal right of action against

the recipient of the grant in aid if it deserts the pur

1 City and County have received the benefits of this interest in

the hospital property for over 60 years.

2 See Appellants’ Brief, p. 17.

3

pose it represented it had when it obtained the grant.”

(Emphasis supplied.)

The interest in the hospital retained by the City and

County here is not limited or declining in any manner. The

County and City have the permanent assurance that the

main hospital building and the land on which it stands will

be used for hospital purposes only and “ for the benefit of

the County and City” or else complete ownership devolves

to the County and City. See Appellants’ Brief pp. 16-17.3

2. The Court in Simkins found that “ In light of Burton

[365 U. S. 715] doubt is east upon Eaton’s continued value

as precedent.” This conclusion disposes of appellees’ con

tention (adopted by the Court below) that the first Eaton

case, 261 F. 2d 521 (4th Cir. 1958), decided prior to Burton,

forecloses any consideration of the merits here. As in

Simkins, “ this case is controlled by Burton” where the Su

preme Court found state action to exist because the state

“ to some significant extent” was involved in private con

duct. Burton, supra, 365 U. S. at 722; Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U. S. 1, 4; Smith v. Holiday Inns, 220 F. Supp. 1 (M. D.

Tenn. 1963).

Appraisal of the totality of governmental involvement

here in light of Burton, supra, and Simkins leaves little

doubt that the policy of racial discrimination of this hos

pital facility must be enjoined. In addition to the property

interest in the hospital held by government in the form of

a sharp limitation on use and a trust for the benefit of the

3 In accord with Simkins and Hampton upholding the signifi

cance of a limitation on use in favor of government is Smith v.

Holiday Inns, 220 F. Supp. 1 (M. D. Tenn. 1963), holding that a

motel which is limited to use as a motel by a governmental prop

erty interest in the nature of a reverter cannot racially dis

criminate.

4

public, government has supported and been significantly

involved with the hospital throughout its history. The total

effect of the hospital’s contacts with government are dis

cussed at length in Appellants’ Brief, pp. 18-28 and sum

marized there at pp. 28-30, and that discussion will not be

repeated here. It should be noted, however, that while

public funds received by James Walker Memorial Hospital

were not allocated under the Hill-Burton Act, as in Simkins,

North Carolina’s participation in the Hill-Burton program

has significantly affected James Walker Memorial Hospital.

Specifically, before any North Carolina hospital could re

ceive federal money under Hill-Burton, the state was re

quired to adopt minimum standards for the maintenance

and operation of hospitals which receive federal aid, 42

U. S. C. §§291f (a)(7), 291f (d). When the state, to meet

this requirement, enacted a “ Hospital Licensing Act” in

1947, N. C. Glen. Stat. §§131-126.1 et seq., authorizing the

adoption of detailed regulations governing hospital main

tenance and operation (22a-57a) both the licensing act and

the regulations applied to all hospitals in the state regard

less of whether they were allocated federal assistance under

Hill-Burton. As a consequence, therefore, of North Caro

lina’s participation in the Hill-Burton program, James

Walker Memorial Hospital is licensed and its day to day

operation subject to comprehensive regulation and control

by the state.

This case is, in fact, far closer to Simkins than to the

first Eaton case, 261 F. 2d 521 (4th Cir. 1958). A rever

sionary interest in favor of government, detailed state regu

lation, and governmental financial assistance for capital

construction were all relied upon by the Court in Simkins.

(And this case has elements of governmental involvement

not present in Simkins, including, to name a few, use of the

power of eminent domain for a public purpose, city and

5

county contributions for capital improvement as well as

contributions toward operating revenues, and use of the

hospital to treat the poor.)4 The only arguable distinction

between Simkins and the present ease is that here the Hos

pital, though licensed and regulated because of Hill-Burton,

did not receive its federal funds as part of the Hill-Burton

program but through another federal assistance program,

the Defense Public Works Act 42 U. S. C. §§1531, et seq.

This distinction is, however, more apparent than real.

In order to be eligible, the United States determined the

hospital a “ facility necessary for carrying on community

life substantially expanded by the national defense pro

gram” , 42 U. S. C. §1531, thus (as in Hill-Burton) clearly

recognizing that the hospital was exercising a public func

tion, the fulfilling of which was of more than local concern.

Moreover, the administrators of the Defense Public Works

Act considered the allocation of hospital resources through

out a community in much the same manner as do the ad

ministrators of the Hill-Burton Act. For example, the

Federal Works Agency which administered the Defense

Public Works Act considered that James Walker Hospital

in its application had not stated what proportion of the

new beds, to be financed by the federal grant, would be allo

cated to Negroes, but apparently disregarded the conse

quences of this omission for the reason that an application

for Defense Public Works Act funds was pending from the

4 As stated by the dissent in Simkins: “the cases here [Simkins]

are stronger for the defense [than Eaton] for these hospitals are

not shown to have been the recipients of any contributions toward

operating revenues, and the land of neither is subject to any right

of reverter in favor of any governmental body.” This statement

refers to the first Eaton case, 261 F. 2d 521 (4th Cir. 1958). It

must apply with even more force to the present case where addi

tional elements of state involvement have been alleged which were

not raised, considered or decided in the first Eaton decision.

6

Community Hospital of Wilmington, North Carolina, a

county-owned, all-Negro hospital (See Appendix A at

p. 10—Document on file with Housing and Home Finance

Agency. A certified copy of this Document has been filed

with the Clerk along with this Brief.) This affirmative sanc

tion of “ separate but equal” facilities by the federal govern

ment was condemned by the Court in Simians: “ It is settled

that governmental sanction need not reach the level of com

pulsion to clothe what is otherwise private discrimination

with ‘state action’ ” .

Secondly, the idea that publicly owned and publicly sup

ported hospitals are interchangeable as far as determining

who shall meet the community need for medical facilities

and be entitled to receive federal assistance was carried

over and is central to the Hill-Burton program as recog

nized by the Court in Simians. When government takes

the responsibility of determining the allocation of a com

munity’s medical facilities and supports the creation of

these facilities with public funds, the function of these facili

ties ceases to be a matter of solely private concern. A gov

ernmental function or responsibility is being exercised and,

as held by the Court in Svmkins, it matters not whether the

participating institutions would otherwise be private.

“ Government’s thumb on the scales” (American Common

Ass’n v. Bonds, 339 U. S. 382, 401) has been a constant in

the history of the James Walker Memorial Hospital. The

forms of government support have been as varied as the

needs of the hospital. As appellants state in their Brief,

pp. 29-30:

But for the “power” and “ property” of government

and the “benefits mutually conferred” (Burton, 365

U. 8. at 724, 725) the hospital would be a far different

institution than it is now, poor in physical resources,

and certainly not a facility “ necessary for carrying on

7

community life,” 42 U. S. C. §1531. Support of the

hospital enabled City and County to create an institu

tion able to serve the medical needs of its citizens while

enabling the hospital to fulfill its chartered purpose.

This is as much a relationship of “ benefits mutually

conferred” as found in the Burton case between a

municipal parking authority and a coffee shop. It

would be to divorce this hospital from its history to

hold it may discriminate on the basis of race. For

“ state action” , taking many forms, has always sup

ported the hospital, and the fruits of government sup

port— still clearly in evidence to any patient or physi

cian—have played a crucial role in providing the

hospital with the resources with which it presently

serves the community.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Constance B aker M otley

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R obert R. B ond

612 Red Cross Street

Wilmington, North Carolina

Conrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

APPENDIX A

(Document on File With Housing and Home

Finance Agency)

October 1, 1941

Memorandum

1. Applicant’s present Hospital (James Walker Memorial

Hospital, Wilmington, N. C.) facilities consist of six (6)

buildings, providing f o r :

173 bed hospital, including 58 private rooms, 115 wards

and 35 Negro beds.

36 Basinets

1 Power plant and laundry (to be removed)

2. Applicant proposes three (3) new buildings for N. G.

31-127, two (2) of which are to be constructed upon a new

site (across Gwynn Street) to be acquired, the other (new

power plant and laundry) to be constructed on site now

owned by Applicant and partially occupied by the existing

buildings. The new buildings are intended to provide f o r :

200 bed hospital

125 bed Nurses home

1 Power plant and laundry

and the Applicant can contribute $100,000 cash in hand

toward its estimated cost of $1,316,759.

3. Regional Director recommends a grant of $399,300 on

his revised estimated cost of $499,300, based on a reduction

in scope to provide for:

100 bed hospital

70 bed Nurses Home

including complete plant and equipment.

10

4. DPW Form No. 28-C recommends an allotment in the

amount of $399,440 which together with Applicant’s funds

of $99,860, makes up the estimated cost of $499,300 based

upon a limitation in scope.

Note: It is not stated in the revised scope, what proportion

of the 100 beds will be available for Negroes, however, DPW

Form No. 28-C recommends for Docket No. N. C. 31-132,

The Community Hospital, City of Wilmington, N. C., a

grant of $216,879 to construct an addition to the existing

hospital (for Negroes) to provide for:

(a) 75 bed addition to present 47 bed. hospital

(b) Addition to the present Nurses Home; and,

(c) New Laundry Building

including equipment for (a), (b) and (c).

Pursuant to 28 U. S. C. 1733(b) and the designation at 28

F. E. 2242 (3/7/63), I herebjr certify that this is a true

copy of the document on file in the Office of the Administra

tor, Housing and Home Finance Agency.

(S eal)

/ s / Mary F. Dennis

Attesting Officer

Office of the Administrator

Housing and Home Finance Agency

38