State Board of Public Welfare Board of Managers v Coleman Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

32 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. State Board of Public Welfare Board of Managers v Coleman Brief of Appellants, 1960. e6826c1a-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e9197c87-1091-4073-8526-96a2be368068/state-board-of-public-welfare-board-of-managers-v-coleman-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

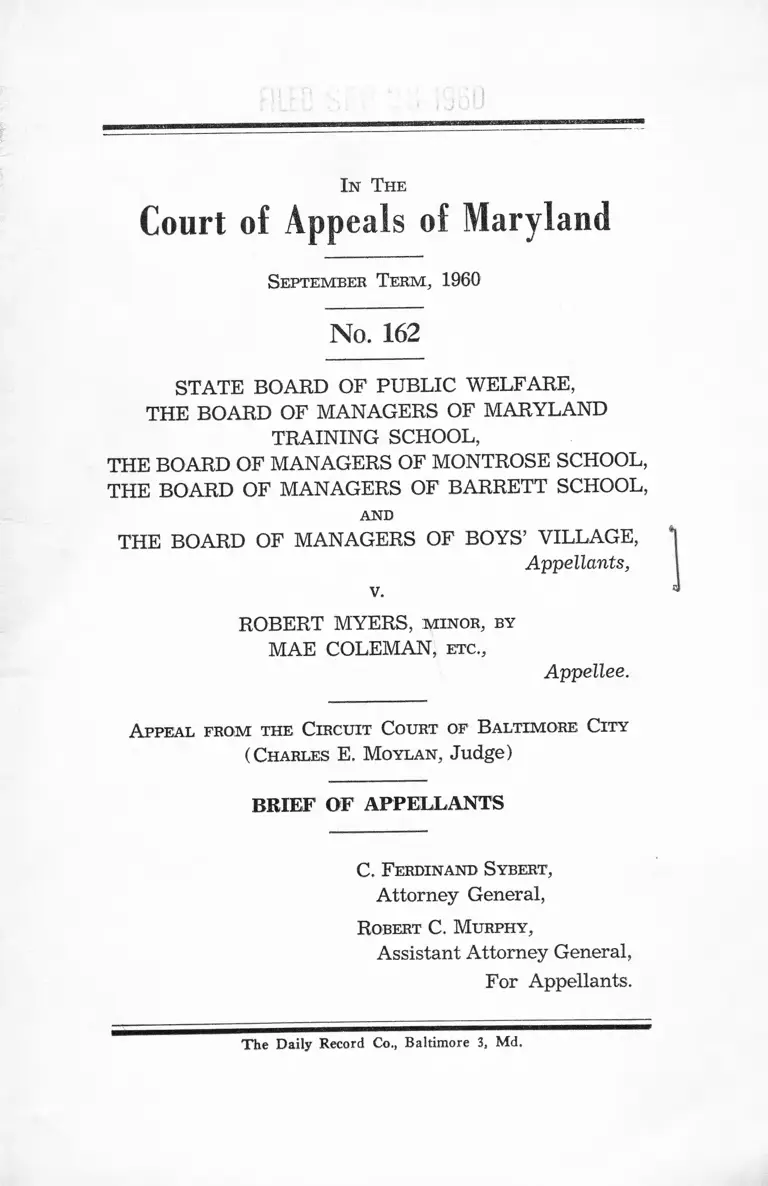

In The

Court of Appeals of Maryland

September Term, 1960

No. 162

STATE BOARD OF PUBLIC WELFARE,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF MARYLAND

TRAINING SCHOOL,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF MONTROSE SCHOOL,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF BARRETT SCHOOL,

AND

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF BOYS’ VILLAGE,

Appellants,

v.

ROBERT MYERS, minor, by

MAE COLEMAN, etc.,

Appellee.

A ppeal from the Circuit Court of Baltimore City

(C harles E. Moylan, Judge)

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

C. Ferdinand Sybert,

Attorney General,

Robert C. Murphy,

Assistant Attorney General,

For Appellants.

The Daily Record Co, Baltimore 3, Md.

I N D E X

Table of Contents

page

Statement of the Case....................................................... 1

Question Presented........................................................... 2

Statement of Facts............................................................. 2

A rgument:

Sections 657 and 659-661 of Article 27 of the

Maryland Code are constitutional..................... 10

Conclusion ............................................................................ 27

Table of Citations

Cases

Allied Stores v. Bowers, 358 U.S. 522......................... 11, 26

Baker v. State, 205 Md. 42............................................ 15,17

Board of Trustees v. Frasier, 350 U.S. 979................. 19

Bolling, et al. v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497......................... 11,14

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 affirmed 352

U.S. 903 .................................................................. 19

Brown, et al. v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 11,12, 21

Clark v. Maryland Institute, 87 Md. 643..................... 12

Davis v. State, 183 Md. 385........................................... 26

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1.......................................... 13

Dawson v. Mayor & City Council of Baltimore, 220

F. 2d 386 affirmed 350 U.S. 877............................. 19, 24

Durkee v. Murphy, 181 Md. 259.................................. 23, 24

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 347 U.S.

971 and 350 U.S. 413................................................. 19

Johnson v. State, 114 A. 2d 1 (N.J.)............................. 16

Jones v. House of Reformation, 176 Md. 43................ 16

Kirkwood v. Provident Savings Bank, 205 Md. 48 26

11

PAGE

Kotch v. River Port Pilot Comm’rs, 330 U.S. 552 11

Leonardo v. Comm’rs, 214 Md. 287............................... 11

Magruder v. Hall of Records Commission, 221 Md. 1 26

McBriety v. Baltimore City, 219 Md. 223 26

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 13

Moquin v. State, 216 Md. 524...................................... 15

Morey v. Doud, 354 U.S. 457 10,11, 20, 26

Nichols v. McGee, 169 F. Supp. 721 appeal dismissed

361 U.S. 6................................................................ 20

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 357 12,13, 23

Price v. Johnson, 334 U.S. 266.................................... 25

Roth v. House of Refuge, 31 Md. 329........................... 16

Shuttleworth v. Board of Education, 162 F. Supp. 372

affirmed 358 U.S. 101.............................................. 13

Siegel v. Ragan, 180 F. 2d 785 21

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535............................. 10

Stebbins v. Riley, 268 U.S. 137 10

Stephenson v. Binford, 287 U.S. 251 26

Taylor v. State, 214 Md. 156 16

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U.S. 312.................................. 11

United States ex rel. Morris v. Radio Station, 200

F. 2d 105.................................................................. 21

Williamson v. Lee Optical, 348 U.S. 483 11, 26

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 10

Statutes

Annotated Code of Maryland (1957 Ed.):

Article 26—-

Secs. 51-71 ....................................................... 3

Secs. 72-90 ....................................................... 15

Sec. 74 .............................................................. 22

Article 27—

Secs. 657 and 659-661 1, 2, 3, 4, 9,10,27

I l l

PAGE

Article 77—

Secs. 1 and 202................................................. 18

Sec. 232 ............................................................. 18

Article 88A—

Sec. 3 3 ............................................................... 3

Baltimore City Charter and Public Local Laws:

Secs. 239-257 ........................................................... 3f 4

Constitution of the United States:

5th Amendment ..................................................... 13

14th Amendment ................2, 4, 5, 9, 10,11,13,19, 23, 24

Miscellaneous

31 Am. Jur., Juvenile Courts and Delinquent, De

pendent and Neglected Children—

Secs. 2 and 19........................................................... 16

78 C.J.S., Schools and School Districts—

Sec. 1,445 ................................................................ 12

Encyclopedia Brittanica—

Vol. 5—

Juvenile Courts, pages 476-479..................... 22

Vol. 13—

Juvenile Delinquency, pages 229, 231 22

In The

Court of Appeals of Maryland

September Term, 1960

No. 162

STATE BOARD OF PUBLIC WELFARE,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF MARYLAND

TRAINING SCHOOL,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF MONTROSE SCHOOL,

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF BARRETT SCHOOL,

AND

THE BOARD OF MANAGERS OF BOYS’ VILLAGE,

Appellants,

v.

ROBERT MYERS, minor, by

MAE COLEMAN, etc.,

Appellee.

A ppeal from the Circuit Court of Baltimore City

(Charles E. Moylan, Judge)

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an appeal from a declaratory decree of the Cir

cuit Court of Baltimore City declaring Sections 657 and

659-661 of Article 27, Annotated Code of Maryland (1957

Ed.), requiring separation of the Negro and white races

in the State’s four correctional training institutions for

2

minors, to be unconstitutional as in violation of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution; and en

joining the Appellants from denying admission of Negro

youths, solely on account of race and color, to any of the

said facilities. The decree appealed from also adjudged

that the courts could not, consistent with the requirements

of the Fourteenth Amendment, select a training school to

which a minor is to be committed solely on the basis of

the minor’s race or color.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Are Sections 657 and 659-661 of Article 27 of the Mary

land Code Constitutional?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The statutes in question, codified in the criminal law

article of the Maryland Code under the designation “Places

of Reformation and Punishment” , relate to the State’s four

correctional training institutions for minors, namely, Boys’

Village, Maryland Training School, Barrett School and

Montrose School. The statutes provide that such institu

tions are public agencies for the care and reformation of

minors committed thereto under the laws of this State, and

further provide that the Maryland Training School shall

be for white male minors, Boys’ Village for colored male

minors, Barrett School for colored female minors, and

Montrose School for white female minors. Specifically, the

statutes read:

Section 657:

“There shall be established in the State an institu

tion to be known as the Boys’ Village of Maryland.

Said institution is hereby declared to be a public

agency of said State for the care and reformation of

colored male minors committed or transferred to its

care under the laws of this State. * *

3

Section 659:

“From and after the acquisition by the State of

Maryland from the Maryland School for Boys, a cor

poration of this State, of the property heretofore held,

conducted and managed by said corporation as a re

formatory institution for the care and training of white

male minors committed thereto under the provisions

of the laws of this State, the same shall continue under

the name of the Maryland Training School for Boys to

be conducted as a public agency of this State for the

care and reformation of white male minors now com

mitted thereto, and who may hereafter be committed

thereto under the laws of this State. * *

Section 660:

“From and after the acquisition by the State of Mary

land of the property of the Maryland Industrial School

for Girls the same shall continue as a reformatory

under the name of the Montrose School for Girls to be

conducted as a public agency of this State for the care

and reformation of white female minors now com

mitted thereto, and who may hereafter be committed

thereto under the laws of this State. * * *.”

Section 661:

“There shall be established in this State, an institu

tion to be known as the Barrett School for Girls. The

said institution is hereby declared to be a public

agency of this State for the care and reformation of

colored female minors committed or transferred to its

care under the laws of this State. * *

By the subtitle preceding Section 33 of Article 88A of

the Maryland Code, these institutions are referred to under

the designation: “Training Schools for Delinquent Chil

dren” . Commitment of delinquent minors to the institu

tions is authorized by the several juvenile court acts in

force in Maryland, principal among which are the so-called

“State-wide Act” (Sections 51-71 of Article 26 of the Code)

and the “Baltimore City Juvenile Court Act” (Sections

4

239-257, as amended, of the Charter and Public Local Laws

of Baltimore City, 1949 ed.).

Appellee herein, a thirteen year-old Negro boy, by his

mother and next friend, filed a bill for a declaratory de

cree in the Circuit Court of Baltimore City on February

26, 1960, in which he challenged the constitutionality of

Maryland’s racially-segregated training institutions, as pro

vided for by said Sections 657 and 659-661 (E. 3-12). He

alleged in his bill that on October 29, 1959, he was adjudged

to be a delinquent child by the Circuit Court of Baltimore

City, Division of Juvenile Causes; that the Juvenile Court

announced its determination at that time to commit him

to a public training school for delinquent minors; that on

Appellee’s behalf a motion was interposed that he be com

mitted to the Maryland Training School for white boys,

rather than to Boys’ Village for colored boys since the

latter, as a racially-segregated training school, could not

provide him with rehabilitation and training equal to that

provided by the Maryland Training School; and that the

Juvenile Court held the motion sub curiae, in the mean

time detaining him over his objection at Boys’ Village.

The bill alleged that racial segregation in the public train

ing schools pursuant to the aforesaid statutory requirement

contravened the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal

Constitution, and that the Order of court detaining him at

Boys’ Village deprived him of his constitutional right to

enjoy non-racially-segregated public training school facil

ities provided by the State of Maryland for delinquent

minors.

Named as Defendants in the bill were the State Board

of Public Welfare and the Boards of Managers of each of

the four training institutions. The bill alleged that De

fendants were authorized by statute (Article 88A of the

Code) to exercise supervision, direction and control over

5

the institutions and to provide for their general manage

ment; and to promulgate rules with respect to the use,

availability and admission of minors thereto; and that the

State Board of Public Welfare was additionally vested with

authority to establish, by rule or regulation, standards of

care, policies of admission, transfer and discharge.

On behalf of the Defendants, a combined demurrer and

answer was filed (E. 13-16). The demurrer, later overruled,

alleged that the challenged statutes represented a valid ex

ercise of the police power of the State and were constitu

tional. The Defendants’ answer to the bill admitted that

the training institutions were operated on a racially-segre

gated basis pursuant to statutory requirement, and further

admitted the statutory authority vested in them over the

operation of the institutions.

At the trial it was stipulated between the parties that

the physical and other tangible factors at the four institu

tions were substantially equal (E. 34). The question thus

raised for determination by the court was simply whether

racial segregation in the State’s correctional training insti

tutions for delinquent minors was, per se, a violation of the

equal protection or due process clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

A statement of the educational program at Maryland

Training School was introduced in evidence as Plaintiff’s

Exhibit No. 3 and stipulated to be representative of the

educational program at the other three institutions (E.

35-42). Also introduced by stipulation of the parties were

two opinions of the Attorney General of Maryland holding

racial segregation in the training schools to be constitu

tional (E. 18-28, 30-33).

Testimony adduced at the trial on behalf of the Appellee

showed that prior to his detention at Boys’ Village, he

#

had attended integrated public schools in Baltimore City

and Baltimore County; that at the time of his adjudication

as a delinquent child by the Juvenile Court, his mother

requested that he be committed to an integrated training

institution for the reason that “I thought if he goes to an

integrated school, he would have a better chance of re

habilitation because he had been going to school with mixed

groups” (E. 43).

Dr. Alvin Thalheimer, Chairman of the State Board of

Public Welfare, testified for Appellee that the training

schools were intended to be rehabilitative rather than

penal institutions, and that school classes were conducted

at the institutions in order that the children might con

tinue their education during the period of their confine

ment (E. 50-51).

Raymond Manella, Chief, Division of Training Schools,

State Department of Public Welfare, testified for the Ap

pellee that the State Department of Education provides

the training schools with a consultant “who carries respon

sibility for professional consultation on educational mat

ters and educational programs” (E. 66). He further testi

fied that it is the responsibility of the training school ad

ministration “to organize and administer and to operate an

educational program for all the youngsters who come into

the State training schools, which is an important part of

the program” (E. 67).

An official document of the State Department of Public

Welfare, entitled “Characteristics of 860 Committed Chil

dren in the Maryland Training Schools on January 1, I960” ,

was received in evidence as Defendants’ Exhibit No. 1 (E.

77-78, 122-124). Table No. 12 of the Exhibit discloses the

type of offense committed by each inmate at each institu

tion. The offenses, as summarized in total, were as follows:

6

t

7

Type of Offense Number

Arson ......................................................... 8

Assault ....................................................... 33

Automobile Theft...................................... 60

Breaking and Entering............................. 126

Disorderly Conduct.................................. 16

Narcotics ................................................... ...

Robbery ..................................................... 23

Sex Offense ............................................... 14

Stealing ..................................................... 184

Vandalism ................................................. 8

Being Ungovernable ................................. 113

Runaway ................................................... 123

Trespassing ................................................ 1

Truancy ..................................................... 85

Violation of Probation ............................. 12

Violation of After Care Supervision...... 2

Other........................................................... 52

Total Offenses.............. 860

The witness Manella, testifying on Defendants’ cross and

direct examination, stated that the training institutions

were obliged to take any and all delinquent minors com

mitted by the courts, but that the purpose of the institu

tions was to bring about the rehabilitation and training of

the child, rather than to punish; that one of the objectives

of the training schools was the protection of the community

and the protection of the child while the rehabilitation

process was being conducted; that all of the children com

mitted to the training schools were maladjusted socially

and that the large majority of the delinquents came from

the lower economic strata (E. 70, 77, 79); that the training

schools were open-custody institutions of the cottage type,

with the inmates being in the cottages approximately two-

thirds of the time, supervision being provided “around the

clock” ; that not much freedom of movement was permitted

8

except for inmates ready for release (E. 79-80, 82); that in

all the training schools there is a combination of dormitory

sleeping accommodations and single rooms; that the in

mates eat all meals within the cottages; that “you won’t be

able to successfully treat children for problems in any

thing approaching a penal or correctional type facility”

(E. 79-80). He further testified that the cottages in which

the inmates are housed are “meant to resemble homes, the

family with the intimate kind of mother or father-child

relationship which you must have in a community if you

are going to produce healthy kids” (E. 80); that super

vision of the inmates was provided at all times by cottage

parents or cottage masters who are symbolic of the in

mates’ own parents (E. 80); that the “hub” of the training

in any cottage type training institution “is in the cottage

and in the cottage program as such, since the youngsters

are exposed to most of their time in the cottage with the

cottage life program and unless this program is properly

managed and unless the activities program is properly ar

ranged, the rehabilitation program will probably fail” (E.

81).

Manella further testified that the training schools at

tempted to establish “a family setting or climate or atmos

phere, that we want a small group atmosphere with a high

degree of relationship so-called between the cottage parent

as such and the youngsters in that particular cottage, which

is a little larger than a realistic family group” (E. 83). He

stated that in the rehabilitation process “I would not place

prime emphasis on the education phase” (E. 81); that the

educational program was not carried on within the cot

tages and that only at Maryland Training School were full

time teachers employed (E. 68, 81).

Manella also testified to having had experience with an

integrated correctional training institution. He was asked:

9

“Q. In the integrated facility with which you have

had experience, is there any air of tension because of

the racial difference? A. I would say initially some

youngsters, depending on their social and cultural form

with reference to the neighborhood and the community

area from which they came and they are brought into

institutions and there is a lot of anxiety in those cases.

ijj iji ^

Q. Doesn’t this tension detract from the basic pur

poses of the institution as you describe it? A. Unless

the institution is properly managed and unless it op

erates with the proper reference to philosophy, it can

very definitely destroy the rehabilitation intention of

the institution, and that has happened” (E. 84).

Elbert Fletcher, Superintendent of the Maryland Train-

in School, testified for Appellants that the “main real ad

justment” of the inmates takes place in the cottages; that

in many cases a boy and father relationship comes about

between the cottage parent and the delinquent boy; and

that within his experience with integrated public training

school facilities in New York racial fights occurred (E.

90-91).

Other testimony at the trial indicated that the inmates

were generally committed to the training institutions on

indeterminate commitments but that the average period

of confinement was actually between eight and nine months.

The trial court declared Sections 657 and 659-661 of

Article 27 to be unconstitutional on the ground that State-

imposed segregation of the races in the training schools

violated both the equal protection and due process clauses

of the 14th Amendment to the Federal Constitution. The

Court based its decision largely on the premise that the

training schools were an integral part of the State’s public

education system and, as such, were within the orbit of

the Supreme Court’s decision in the School Segregation

Cases prohibiting racial segregation in public schools.

10

Pursuant to the Court’s decree entered July 6, 1960, the

'Order of the Juvenile Court detaining Appellee at Boys’

Village was rescinded, and he was committed to the Mary

land Training School where he presently remains under

confinement (E. 121).

ARGUMENT

SECTIONS 657 AND 659-661 OF ARTICLE 27 OF THE

MARYLAND CODE ARE CONSTITUTIONAL.

It is fundamental that the equal protection clause of the

14th Amendment, applicable to State action, secures to all

citizens without distinction of race or color equality of

rights of a civil or political kind. In other words, the

Amendment provides equal protection and security to all

under like circumstances in the enjoyment of their civil

and political rights. The guarantee of equal protection of

the law is thus a pledge of the protection of equal laws,

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356. Manifestly, however,

the equal protection clause does not prohibit the states from

selecting and classifying objects of legislation according to

need, and as dictated or suggested by experience, so long

as the classification rests upon reasonable grounds of dis

tinction. Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535; Stebbins v.

Riley, 268 U.S. 137. In Morey v. Doud, 354 U.S. 457 (1957),

the Supreme Court summarized the operation of the equal

protection guarantee in these words:

“ 1. The equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment does not take from the State the power

to classify in the adoption of police laws, but admits

of the exercise of a wide scope of discretion in that re

gard, and avoids what is done only when it is without

any reasonable basis and therefore is purely arbitrary.

2. A classification having some reasonable basis does

not offend against that clause merely because it is not

made with mathematic nicety or because in practice

it results in some inequality. 3. When the classifica

tion in such a law is called in question, if any state of

11

facts reasonably can be conceived that would sustain

it, the existence of that state of facts at the time the

law was enacted must be assumed. 4. One who assails

the classification in such a law must carry the burden

of showing that it does not rest upon any reasonable

basis, but is essentially arbitrary * * *.”

In the broad sense, all classification by a state involves

some discrimination. It is not, however, discrimination

per se which is proscribed by the 14th Amendment; rather,

the prohibition of the equal protection clause goes no fur

ther than the invidious discrimination. Morey v. Doud,

supra; Williamson v. Lee Optical, 348 U.S. 483 (1955);

Kotch v. River Port Pilot Commissioners, 330 U.S. 552

(1947). A classification, therefore, even though discrimina

tory, is not arbitrary nor violative of the equal protection

clause if any state of facts reasonably can be conceived

that would sustain it. Allied Stores v. Bowers, 358 U.S.

522 (1959). See also Leonardo v. Commissioners, 214 Md.

287.

The due process guarantee of the 14th Amendment de

mands only that the particular law not be unreasonable,

arbitrary or capricious and that the means selected shall

have a real and substantial relation to the object sought

to be attained. This guarantee thus tends to secure equality

of law in the sense that it makes a required minimum of

protection for everyone’s right of life, liberty and property

which the State may not withhold. Truax v. Corrigan, 257

U.S. 312.

Against this background of well-established constitu

tional principles, the Supreme Court in 1954 decided the

School Segregation Cases — Brown, et al. v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483, and Bolling, et al. v. Sharpe, 347

U.S. 497 — involving public elementary and public high

schools, institutions which, broadly speaking, are open and

12

public to all in the locality, with the right to attend such

facilities being a fundamental and positive civil right be

longing to citizens as members of society. See 78 C.J.S.,

Schools and School Districts, Sec. 1, 445; Clark v. Maryland

Institute, 87 Md. 643, at page 661. The question in each

of the School Segregation Cases was essentially the same:

Does segregation of children in public elementary and pub

lic high schools solely on the basis of race, even though

the physical and other tangible facilities may be equal,

deprive children of the minority group of equal educational

opportunities? This question placed squarely in issue the

validity, as applied to public schools, of the “separate but

equal” doctrine laid down in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S.

357 (1896), a case upholding the constitutionality of a

Louisiana statute providing for racially segregated public

transportation facilities, in which the Supreme Court said:

“The object of the (14th) amendment was undoubt

edly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races

before the law, but in the nature of things it could not

have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon

color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from po

litical, equality, or a commingling of the two races

upon terms unsatisfactory to either. Laws permitting,

and even requiring their separation in places where

they are liable to be brought into contact do not neces

sarily imply the inferiority of either race to the other,

and have been generally, if not uniformly recognized

as within the competency of state legislatures in the

exercise of their police power * *

In the Broion case, the Supreme Court held that racially

segregated public schools, though physically equal, had a

detrimental psychological effect on the colored children,

retarding their educational and mental development, and

hence were “ inherently unequal” . This conclusion com

pelled the Court to repudiate, as applied to public schools,

13

the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson,

supra — a doctrine which depended solely for its validity

upon the equality of the separate facilities provided the

minority race. See Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305

U.S. 337. The colored children being thus deprived of equal

educational opportunities by reason of such racially segre

gated public schools — and there being no reasonable basis

to support such a classification — the Court held that the

equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment prohibits

the states from maintaining racially segregated public

schools.

In the Bolling case, the Court held that segregation in

the public schools of the District of Columbia imposed a

burden on the Negro children which constituted an arbi

trary deprivation of their liberty in violation of the due

process clause of the 5th Amendment. In that case, the

Court specifically held that segregation in public education

is not reasonably related to any proper governmental ob

jective. This conclusion was reaffirmed in Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1 (1958), wherein it was held that even though

racial segregation in the public schools may promote the

public peace by preventing race conflicts, this aim could

not be accomplished by laws which denied the fundamental

and positive civil right of the individual to equal educa

tional opportunities in the public schools. Compare, how

ever, Shuttleworth v. Board of Education, 162 F. Supp. 372,

affirmed 358 U.S. 101 (1958), upholding the constitution

ality of the Alabama School Placement Law.

It is now entirely clear that the Supreme Court views

racial segregation in the public elementary and public high

schools to be per se an invidious discrimination, one with

out any reason or support, and, therefore, palpably arbi

trary. It is equally clear, however, that these cases do

14

not purport to proscribe all state-imposed segregation of

the races as being per se in violation of the Federal Con

stitution. On the contrary, the Supreme Court in the

Bolling case said:

“Classifications based solely upon race must be scru

tinized with particular care since they are contrary

to our traditions and hence constitutionally suspect.

* * * >>

In effect, therefore, the Supreme Court said that there are

some classifications based solely on race which are con

stitutionally valid; that one is not merely substituting race

for reasonableness in all cases when racial classifications

are made.

THE STATE’S FOUR CORRECTIONAL TRAINING INSTITUTIONS

FOR DELINQUENT MINORS ARE NOT PUBLIC SCHOOLS, AND

FORM NO PART OF THE STATE’S PUBLIC EDUCATION SYSTEM

IN THE SENSE CONTEMPLATED BY THE SUPREME COURT IN

THE SCHOOL SEGREGATION CASES.

Appellants concede at the outset that the content of the

educational courses offered the inmates at the training in

stitutions reasonably coincides with standards required in

the public schools of the State. In itself, however, this

fact does not transform the correctional training institu

tions for delinquent minors into public schools, or justify

the conclusion that they are an integral part of the State’s

public education system, as held by the court below, any

more than the existence of a library in a penitentiary trans

forms the penitentiary into a reading room; or the pro

vision of recreational facilities at a university transforms

the university into a playground. It is the total institution,

and not its singular parts, which is determinative of its

basic character and purpose.

15

By express legislative declaration, the training institu

tions are for “care and reformation” , primarily of minors

adjudged delinquent by the juvenile courts of this State.1

In Baker v. State, 205 Md. 42, the correctional training

institutions were held to be reformatories, escape from

which is punishable under Maryland’s criminal escape

staute. In accordance with the philosophy underlying

enactment of Maryland’s juvenile court laws, however,

minors committed to these institutions, although there

under total restraint of their liberty for wrongs perpe

trated against the State, are not deemed to be criminals,

nor are the institutions looked upon as being penal in

nature. Instead, as recognized by this Court in Moquin v.

State, 216 Md. 524, these institutions are corrective and

protective facilities dedicated in the main to the rehabili

tation of the State’s erring youth by an enforced institu

tional program intended to check and remedy, rather than

punish, the criminal tendency in its inception. In this

setting the State assumes a parental role, acting under the

1 The State-wide and Baltimore City Juvenile Court Acts, supra,

page 3, define a delinquent child to be a child under the age of

eighteen years, and sixteen years, respectively, who (1 ) violates any

law or ordinance, or who commits any act which, if committed by

an adult, would be a crime not punishable by death or life imprison

ment; (2 ) who is incorrigible or ungovernable or habitually dis

obedient or who is beyond the control of his parents, guardian, cus

todian or other lawful authority; (3 ) who is habitually a truant;

(4 ) who without just cause and without the consent of his parents,

guardian or other custodian, repeatedly deserts his home or place

of abode; (5 ) who is engaged in any occupation which is in violation

of law, or who associates with immoral or vicious persons; or (6 )

who so deports himself as to injure or endanger the morals of him

self or others.

These acts provide that where a delinquent child is in need of

“ care and treatment” , the juvenile judge shall have the right to place

him, not beyond his minority, in the custody of a public or private

institution. See also the Montgomery County Juvenile Court Act,

Section 72, et seq., of Article 26 of the Code, and the special pro

visions for Washington and Allegany Counties.

16

parens patriae doctrine as the protector, the ultimate

guardian of the delinquent minors, so as to make good

citizens of potentially bad ones. See 31 Am. Jur., Juvenile

Courts and Delinquent, Dependent and Neglected Children,

Sections 2 and 19; and Roth v. House of Refuge, 31 Md. 329

(1869), recognizing the training institutions to have ref

ormation as their objective by training the inmates to in

dustry; imbuing their minds with principles of morality

and religion; and, “above all, by separating them from the

corrupting influence of improper associations” . See also

Taylor v. State, 214 Md. 156; and Jones v. House of Ref

ormation, 176 Md. 43.

In Johnson v. State, 114 A. 2d 1 (N.J.) (1955), the Court,

in referring to juvenile proceedings under that State’s

juvenile laws, and particularly to the parens patriae doc

trine, said:

“ * * * Its exercise can be spelled out of the many

statutory provisions relating to the settlement, incar

ceration, care and support of such persons (minors

under disability, such as juvenile delinquents) by the

State. This jurisdiction and duty is called into play

when it is found that such persons could be a danger

to themselves or to the public if they were not taken

and held under the protective custody of the sovereign,

* * *

“The statute, by providing that a person under the

age of 16 is deemed incapable of committing a crime,

does not ignore the offense but merely has the effect

of stating a child under that age cannot commit a

crime, but it does have the effect of placing such a

child under a legal disability and subjects his liberty

to the parens patriae jurisdiction of the State. It is

the fact that the child committed the offense that is

determinative of this restraint of liberty in aid of his

rehabilitation through reformation and education. The

restraint under the parens patriae doctrine is for cura-

17

live rather than punitive purposes. * * *.” (Emphasis

supplied.)

Along similar lines, this Court in Baker v. State, supra,

noted :

“ * * * the statute creating Boys’ Village states that

it is a place for ‘care and reformation’. Indeed, it has

been so described throughout its legislative history.

* * * It has been variously called ‘The House of Ref

ormation and Instruction’, ‘The House of Reformation’,

‘Cheltenham School for Boys’ and ‘Boys’ Village’, but

all along the accent has been on education and training

rather than punishment. Changes in management,

including the recent transfer to the supervision and

control of the Department of Public Welfare, and

changes in the legal concept of Juvenile Causes, have

not changed the fundamental nature of the institu

tion.* * (Emphasis supplied.)

The academic courses conducted within the training in

stitutions, though part of the corrective and rehabilitative

process, do not constitute a prime phase of the total insti

tutional program, as testified by the witness, Manella (E.

81). The lack of institutional requirement that inmates

over sixteen years of age pursue any academic program

at all during their period of confinement clearly substan

tiates this conclusion (E. 35). That prime emphasis is not

placed on the academic phase is wholly logical since it was

not academic deficiency that necessitated confinement in

the first place, nor will it be scholastic achievement, or the

lack of it, that determines suitability for release from con

finement.

The lower court’s opinion referred to two schools within

the Baltimore City public school system that are main

tained exclusively for boys formally adjudged delinquent

18

by the Juvenile Court of Baltimore City, and placed on

probation. The court reasoned, in effect, that these schools,

being part of the Baltimore City public school system, were

no different from the State training institutions, concluding

that if the former were part of the public education system,

so were the latter. While the record does not contain any

mention of these Baltimore City schools, and the court’s

opinion does not cite any reference pursuant to which

they were created, it is believed that they owe their exist

ence directly to the Public Education article of the Mary

land Code, specifically Section 232 of Article 77, which

authorizes Baltimore City to establish parental schools

for habitual truants. In accordance with Sections 1 and

202 of Article 77, these schools are expressly provided for

within the Baltimore City public school system and, as

such, are under the jurisdiction and control of the Depart

ment of Education.

Contrariwise, the State’s four correctional training insti

tutions for delinquent minors are provided for in the

Criminal Law article of the Code under the designation:

“Places of Reformation and Punishment” ; they are not

under the control of the Department of Education, but

rather under the exclusive jurisdiction and control of the

Appellants, exercising powers granted by Article 88A of

the Code. Unlike public schools, the training institutions

are not open and public to all in the locality, and admission

thereto is hardly a matter of right. Merely referring to

the training schools as “schools” , rather than as reforma

tories, does not change the fundamental nature of the in

stitutions. Baker v. State, supra. Clearly, the Legislature

did not intend that the training schools be included as a

part of the State’s general public school or public education

System; and Appellants submit that the constitutionality

of racial segregation in these institutions is not controlled

19

by the Supreme Court’s decision in the school Segregation

cases.

Nor do the decisions in Dawson v. Mayor and City Coun

cil of Baltimore, 220 F. 2d 386, affirmed 350 U.S. 877, or

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707, affirmed 352 U.S. 903,

relied upon by the trial court, control the decision in the

instant case. In the Dawson case, the Fourth Circuit held

that segregation of the races in public recreational facili

ties, even though such facilities were entirely equal, vio

lated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

The Court held, on authority of the School Segregation

Cases, that such segregation could not be justified as a

means to preserve the public peace “merely because the

tangible facilities furnished to one race are equal to those

furnished to the other” . It rejected the “ separate but

equal” doctrine in the field of public recreational facilities;

and further could find no proper governmental objective

to be served by segregating the races in such facilities,

saying:

“ * * * if that power (State’s police power) cannot

be invoked to sustain racial segregation in the schools,

where attendance is compulsory and racial friction

may be apprehended from the enforced commingling

of the races, it cannot be sustained with respect to

public beach and bath house facilities, the use of which

is entirely optional.”

By like reasoning, the court in the Browder case held

segregation of the races in public transportation facilities

to be unconstitutional.

The “separate but equal” doctrine has, therefore, speci

fically been repudiated in the fields of public education2,

public recreation and public transportation, and addition

2 Extended to cover state universities and colleges in Florida ex

rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 347 U.S. 971, and o50 U.S. 413;

and Board of Trustees v. Frasier, 350 U.S. 979.

20

ally, in these particular areas, each involving fundamental

and positive civil rights belonging to citizens as members

of society, it is clear that the courts have considered, but

rejected, the need to preserve the public peace as being

a sufficiently weighty justification upon which to deprive

the individual of his basic constitutional rights.

Apart from these particular areas, however, and in other

areas where “the separate but equal” doctrine has never

been applied as the constitutional test for separating the

races — as in the facilities involved in the present case —

the inquiry must be: Does the racial classification rest

upon some real or substantial difference pertinent to a

valid legislative objective? In other words, the question

in these instances must be whether the racial classification

is justified within the rules laid down by the Supreme

Court in Morey v. Doud, supi’a. In this connection, the

reasonableness of state action separating the races must

take into account the relative weights of the beneficial

consequences which will follow from upholding the classi

fication, as against the price which must be paid therefor

in the form of resulting deprivation, if any, of civil rights.

The point is well illustrated by the case of Nichols v.

McGee, 169 F. Supp. 721, appeal dismissed, 361 U.S. 6

(1959). In that case, the petitioner, an inmate of a state

prison, contended that his constitutional guarantee of equal

protection of the law was denied him in that he was re

quired to join an exclusively Negro line formation when

proceeding to his assigned cellblock for daily lockup and

to the prison dining hall, and that he was required to eat

in a walled-off and exclusively Negro compartment in the

prison dining hall. He contended that such systematic

segregation caused him a loss of self-respect, thereby mak

ing it difficult for him to effect the same degree of rehabili

21

tation possible for unsegregated prisoners of other races.

He relied principally on Brown v. Board of Education,

supra. The Court there held: “By no parity of reasoning

can the rationale of Brown v. Board of Education be ex

tended to state penal institutions where the inmates, and

their control, pose difficulties not found in educational

systems. Federal courts have long been loath to interfere

in the administration of state prisons.” See also United

States ex rel. Morris v. Radio Station, 209 F. 2d 105 (1953 ),

wherein Morris, a Negro inmate of a state penitentiary,

alleged, among other things, that he was discriminated

against and denied equal protection of the laws solely be

cause of his race, in that he was denied the privilege to

audition or act as an announcer of a radio program heard

within the prison, and using prison talent. The Court said:

“Inmates of state penitentiaries should realize that

prison officials are vested with wide discretion in

safeguarding prisoners committed to their custody.

Discipline reasonably maintained in state prison is not

under the supervisory direction of Federal Courts.

* * * A prisoner may not approve of prison rules and

regulations, but under all ordinary circumstances that

is no basis for coming into a Federal Court seeking

relief even though he may claim that the restrictions

placed upon his activities are in violation of his con

stitutional rights.”

To the same effect, see Siegel v. Ragan, 180 F. 2d 785.

Separation of White and Colored Children in the

State’s Four Correctional Training Institutions for

Delinquent Minors I s N ot A n Arbitrary Classification,

But Rests Upon Reasonable Grounds of Distinction,

Conducing to the Attainment of a Proper Governmental

Objective.

Juvenile delinquency in the broad sense is a social prob

lem, primarily rooted in social and psychological causes.

22

From the testimony at the trial, it is manifest that control

and guidance of a parental nature, properly applied within

minimum security facilities, is the first and most important

essential overriding all other considerations in the State’s

effort to successfully rehabilitate its institutionalized juve

nile offenders. Consistent with this end, the State’s cor

rectional training schools are open-custody institutions

of the “cottage type” , the cottages being meant to resemble

homes, and being staffed with “cottage parents” who are

intended to be symbolic of the inmates’ own parents. The

environmental setting thereby created is one as nearly as

possible duplicating the home or family life atmosphere,

and it is under such optimum conditions that the State,

standing in the stead of the inmates’ own parents, under

takes to bring about the requisite social readjustment of

the delinquent offender prior to returning him to society.

The validity of these concepts is well recognized. See

the Encyclopedia Brittanica, Vol. 13, Juvenile Delinquency,

page 229-231, and Vol. 5, Juvenile Courts, page 476-479.

See particularly the Montgomery County Juvenile Court

Act, supra, stating (Section 74):

“The purpose of this subtitle is to secure for each

child under its jurisdiction such care and guidance,

preferably in his own home, as will serve the child’s

welfare and the best interest of the State; to conserve

and strengthen the child’s family ties whenever pos

sible, removing him from the custody of his parents

only when his welfare or the safety and protection of

the public cannot be adequately safeguarded without

such removal; and, when such child is removed from

his own family, to secure for him custody, care, and

discipline as nearly as possible equivalent to that which

should have been given by his parents. * * * ” . (Em

phasis supplied.)

23

The success of the rehabilitation program is thus pri

marily dependent upon, geared to, and revolves around

the cottage life of the inmates. It is here that they spend

approximately two-thirds of their time, living, eating,

sleeping and playing together, and it is under such con

ditions — conditions most closely and realistically approxi

mating the social environment to which the inmates must

return upon release from confinement -—- that the basic

reformation of the delinquents’ antisocial tendencies must

be effected. To mix the racial cultures in this setting would

not only subject each to a social climate as an integral part

of his treatment which neither will experience upon dis

charge from confinement, but it would further competely

nullify the fundamental role played by the cottage parents

in the rehabilitative process — for it is not to be expected

that inmates of either race will look to the other for the

parental attachment and guidance which lies at the very

foundation of the institutional program. As the Supreme

Court said in Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, the object of the

14th Amendment was not to enforce a commingling of the

two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either.

Also to be considered in light of the foregoing is the fact

that the institutional atmosphere — one already charged

with natural tensions normally resulting among individuals

compelled to live together under close restraint of their

liberty — most conduces to attain its desired end when

there is a minimum of extraneously caused friction or

hostility. In Durkee v. Murphy, 181 Md. 259!, 265, this

Court made the following factual observation with refer

ence to segregated recreational facilities:

“ * * * And these provisions must, we conclude, be

construed to vest in the Board the power to assign

the golf courses to the use of the one race and the

other in an effort to avoid any conflict which might

24

arise from racial antipathies, for that is a common

need to be faced in regulation of public facilities in

Maryland, and must be implied in any delegation of

power to control and regulate. There can he no ques

tion that, unreasonable as such antipathies may he,

they are prominent sources of conflict, and are always

to he reckoned with. * * * (Emphasis supplied.)

Although the Durkee case was overruled, as to its legal

conclusions, by the decision in Dawson v. Mayor and City

Council of Baltimore, supra, this Court’s factual observa

tion as to racial antipathy remains a valid one of far

greater application when applied to reformatory institu

tions. Just as overcrowding of too many disturbed chil

dren in cottage limits the possibilities of treatment, and

invites the surrender of staff and program to mere custody,

so would racial friction likely lead to such a result, and

deprive both races of the essential treatment each requires

independent of the other to most profitably effect their

rehabilitation.

In view of the foregoing, to separate the races in the

correctional training institutions for delinquent minors

is not an arbitrary classification, but is one resting upon

reasonable grounds of distinction, clearly serving to the

attainment of a proper governmental objective. The classi

fication under such circumstances is not discriminatory,

much less would it be an invidious discrimination violative

of the equal protection clause. Nor does separation of the

races in these facilities constitute an arbitrary deprivation

of the inmates’ liberty violative of the due process clause

of the 14th Amendment, as held by the lower court.

As heretofore noted, in assessing the reasonableness of

any law, both from the standpoint of the equal protection

and due process guarantees, it is necessary to evaulate

the beneficial consequences which would follow from up

25

holding the law, as against the price which must be paid

therefor in the form of resulting deprivation of the citizens’

constitutionally guaranteed rights. Appellants, though pre

ferring to rest the constitutionality of racial segregation

in the training schools on considerations of positive sub

stance, cannot overlook the fact that unlike the funda

mental, positive and pervasive civil rights of the individual

involved in the public school, public recreation and public

transportation cases, there is no constitutionally guaran

teed right to be incarcerated in the training schools; nor

does the individual enjoy any right, once there, to dictate

to the State the terms under which he will consent to be

rehabilitated. The individual has no civil right under the

circumstances to consort with whom he pleases, when he

wishes, or to be given rights and privileges without regard

to the special and peculiar conditions existing within the

institutions. Basically, the individual is confined in the

training institution against his will for wrongs perpetrated

against the State, and he will remain so confined until

such time as his fledgling criminal and antisocial tendencies

can be remedied by institutional treatment. As observed

by the Supreme Court in Price v. Johnson, 334 U.S. 266:

“ * * * Lawful incarceration brings about the neces

sary withdrawal or limitation of many privileges or

rights, a retraction justified by the considerations

underlying our penal system. * *

The State’s obligation to rehabilitate its offending minors

in such manner, and under such conditions, as it deems

best calculated to assure their return to society as useful

citizens is a responsibility of the highest order. The ex

tent to which the separation of the races in these facilities

conduces to that end, the degree of its efficiency, the close

ness of its relation to the end sought to be accomplished,

are matters addressed to the judgment of the Legislature.

26

It is enough if it can be seen that in any degree, or under

any reasonably conceivable circumstances, there is an ac

tual relation between the means and the end. Allied Stores

v. Bowers, supra; Morey v. Doud, supra; Williamson v.

Lee Optical, supra; Stephenson v. Binford, 287 U.S. 251;

McBriety v. Baltimore City, 219 Md. 223; and Davis v.

State, 183 Md. 385.

This Court has many times stated and restated, empha

sized and reemphasized, that every presumption favors

the constitutionality of a legislative enactment, and a

successful attack upon it must show clearly and affirma

tively that it is arbitrary, capricious, discriminatory or

illegal. The rule, while requiring no elaboration, was re

cently well summarized by this Court in Magruder v. Hall

of Records Commission, 221 Md. 1, as follows:

“ * * * We have held time and time again that there

is a presumption in favor of the validity of a statute,

that it will not be stricken down as invalid unless it

plainly contravenes a provision of the Constitution

and that a reasonable doubt in its favor is enough to

sustain it.”

And in Kirkwood v. Provident Savings Bank, 205 Md. 48,

this Court said:

“ * * * The Court will not denounce a statute as void

on the ground that the lawmaking power has violated

the Constitution, except when such violation is clear

and unmistakable. Consequently the Court will al

ways so construe a statute as to avoid a conflict with

the Constitution and give it full force and effect when

ever reasonably possible * *

27

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, it is respectfully submitted that

Sections 657 and 659-661 of Article 27, Annotated Code of

Maryland (1957 Ed.) are constitutional. The declaratory

decree appealed from should, therefore, be reversed, with

costs awarded to the Appellants.

Respectfully submitted,

C. Ferdinand Sybert,

Attorney General,

Robert C. Murphy,

Assistant Attorney General,

For Appellants.