Smith v Hampton Training School for Nurses Appeal

Public Court Documents

August 20, 1965

34 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Hampton Training School for Nurses Appeal, 1965. 2cc8139d-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e921d233-c8bd-47e6-8235-9ee5320b22d6/smith-v-hampton-training-school-for-nurses-appeal. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

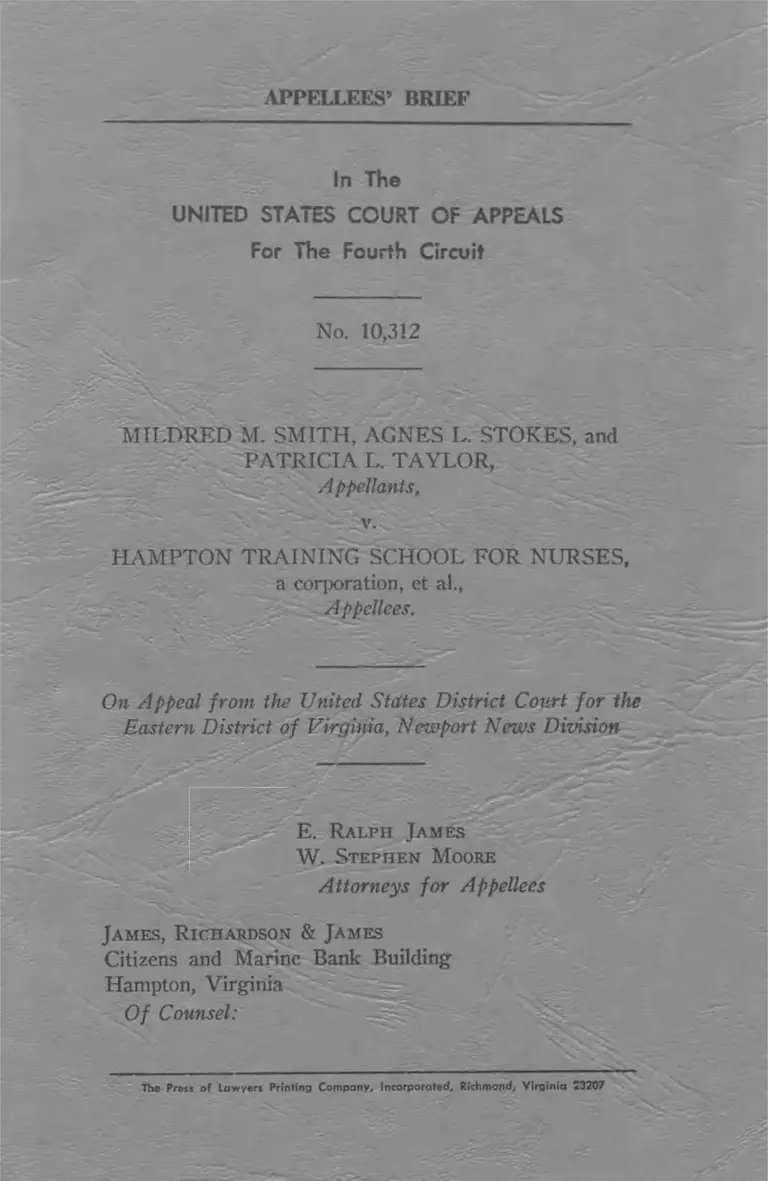

APPELLEES’ BRIEF

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Fourth Circuit

No. 10,312

MILDRED M. SMITH, AGNES L. STOKES, and

PATRICIA L. TAYLOR,

Appellants,

v.

HAM PTON TRAINING SCHOOL FOR NURSES,

a corporation, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, Newport News Division

E. R a l p h J a m e s

W . S t e p h e n M o o r e

Attorneys for Appellees

J a m e s , R i c h a r d s o n & J a m e s

Citizens and Marine Bank Building

Hampton, Virginia

O f Counsel:

The Press of Lowyers Printing Company, Incorporated, Richmond, Virginia S3207

INDEX

Page

Statement of the Case ........ ............................................. 1

Statement of Facts ........................................................... 4

Questions Presented ......... 7

Argument:

I. Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital

changed the law and no right of action was retro

spectively created by that decision............................ 8

A. The law on August 9, 1963, was clear that the

Dixie Hospital was a private entity and that action by

the assistant administrator in enforcing hospital poli

cies was not unlawful “state action” ............................ 9

B. Although Linkletter v. Walker and Flemming

v. South Carolina Electric & Gas Co. are not control

ling on this case, their rationales serve as a guide in

answering the initial question presented...................... 16

II. The nurses are not entitled to reinstatement with

back pay ............................................ 23

. 28Conclusion

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) .......................... 19

Bridges v. Hampton Training School for Nurses, Civil

No. 1001, E.D.Va......................................... ................. 3

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

................................ -................................................9 ,11 ,19

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715 (1961) .................................................. 12, 13, 15, 16

Chicot County Drainage Dist. v. Baxter State Bank,

308 U.S. 371 (1940) .............................................. 18, 19

Eaton v. Board of Managers of James Walker Memorial

Hospital, 261 F.2d 521 (4th Cir. 1958), cert denied

359 U.S. 984 (1958) .................................. 10, 12, 13, 14

Eaton v. Grubbs, 216 F. Supp. 465 (E.D.N.C. 1963),

329 F.2d 710 (4th Cir. 1964) .......................... 14, 15, 20

Flemming v. South Carolina Electric & Gas. Co., 239

F.2d 277 (4th Cir. 1956) ........................................ 16, 18

Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 (1903) 24

Page

Great Northern Ry. v. Sunburst Oil & Refining Co.,

287 U.S. 358 (1932) ................................. ................... 17

Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, 304 F.2d 320 (5th Cir.

1962) ................................................... ........................... 13

Khoury v. Community Memorial Hospital, 203 Va. 236,

123 S.E.2d 533 (1 962 )............................... .............14, 15

Kuhn Fairmont Coal Co., 215 U.S. 349, (1910) ........... 17

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965) .... 16, 17, 18, 21

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961 )................................ 16

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) ...................... 19

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 211 F.

Supp. 628 (M.D.N.C. 1962), 323 F.2d 959 (4th Cir.

1963), cert, denied, 376 U.S. 938 (1964) .... 5, 8, 11, 12,

13, 14, 18, 19, 20, 21 23, 28

Smith v. Hampton Training School for Nurses, 243

F. Supp. 403 (E.D.Va. 1965) ............................ 3, 5, 13, 19

Wood v. Hogan, 215 F. Supp. 53 (W.D.Va. 1963) .. 13, 14

Page

TABLE OF STATUTES AND REGULATIONS

28 U.S.C. §1343 (3) .................................................... 2,

42 U.S.C. §291e(f) ............................................ 5, 12,

42 U.S.C. §291h(b) ........................................................

42 U.S.C. §1981 ..............................................................

42 U.S.C. §1983...........................................................2,

42 C.F.R. §53.112 ...................................................... 5,

TABLE OF OTHER REFERENCES

15 Am. Jur. 2d “Civil Rights” §56-62 (1964) ............

15 Am. Jur. 2d “Civil Rights” §70 (1964) ....................

16 Am. Jur. 2d “Constitutional Law” §178 (1964) ....

35 Am. Jur. Master and Servant §34 (1941) ................

Appellants’ Appendix .......................................................

Appellants’ B rie f .................................................... 4, 11,

Defendants’ Supplementary Brief ..................................

, 8

14

4

23

24

12

25

25

19

23

6

13

8

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Fourth Circuit

No. 10,312

MILDRED M. SMITH, AGNES L. STOKES, and

PATRICIA L. TAYLOR,

Appellants,

v.

HAMPTON TRAINING SCHOOL FOR NURSES,

a corporation, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, Newport News Division

APPELLEES’ BRIEF

STATEM ENT OF TH E CASE

This suit was brought by three Negro nurses on their

own behalf and concerned certain acts which occurred in

August and September, 1963. The suit was brought in the

?

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia on May 25, 1964 under the Civil Rights Act

(prior to its amendment in 1964). Jurisdiction was invoked

under 28 U.S.C. §1343(3) and 42 U.S.C. §1983. The

complaint stated:

“This is a proceeding for a preliminary injunction and

a permanent injunction enjoining defendants and their

agents, employees, successors and all persons in active

concert with them from refusing:

1. To reinstate the plaintiffs, Mildred M. Smith, Pa

tricia L. Taylor and Agnes L. Stokes in their former

positions as nurses at the Dixie Hospital.

2. To provide back pay for the plaintiffs from the

time of their dismissal to the present.”

As defendants the complaint named the administrators of

the Dixie Hospital, the corporate entity, and officers and

directors of the corporation. The defendants’ answer was

duly filed on June 17, 1964.

Interrogatories submitted by the nurses were answered

by the hospital July 24, 1964. On January 18, 1965, the

District Court held an initial pre-trial conference and set

the case for trial July 27, 1965. Also on January 18, the

hospital demanded a jury trial for all the triable issues.

Motion to strike the Dixie Hospital’s demand for a jury

trial was filed by the nurses on February 15, 1964, and

several cases were therein cited to support the motion

to strike.

3

On April 14, 1965, the hospital filed a motion to dismiss

the complaint for failure to state a claim upon which relief

could be granted, and as required by local rules that motion

was accompanied by a brief which contained the reasoning

and legal authority relied upon. The Court agreed to hear

argument on that motion as well as on the motion to strike

the demand for a jury trial on May 25, 1965. On May 2,

1965, the nurses filed a brief in opposition to the motion

to dismiss. On May 6th, the hospital filed a memorandum

containing authorities to support the proposition that it

was entitled to a jury trial in this suit. The motions were

argued by counsel on May 25, 1965, and after hearing

the argument the District Court granted the parties ad

ditional time within which to file supplemental briefs rel

ative to the motions. Both the hospital and the nurses

availed themselves of the opportunity and filed supple

mentary briefs on June 14, 1965. On July 1, 1965, after

consideration of the pleadings and exhibits filed, the briefs,

and the oral argument of counsel, the District Court orally

advised counsel that the motion to dismiss would be treated

as a motion for summary judgment on the pleadings and

would be granted, and at that time the Court stated its

reasons for that decision. The Court’s memorandum was

filed on July 20, 1965, and the final order, dismissing this

action at the cost of the plaintiffs, was filed on August 20,

1965. The opinion is reported, Smith v. Hampton Training

School for Nurses, 243 F. Supp. 403 (E.D. Va. 1965).

It is noted that a companion case, Bridges v. Hampton

Training School for Nurses, Civil No. 1001, E.D. Va., was

filed at the same time as the instant case. As pointed out by

the District Court the companion case repeats many of the

allegations of the present case. The issue involved in the

companion case is whether or not discriminatory practices

4

still exist at the Dixie Hospital which warrant injunctive

relief. The Appellants’ Brief makes numerous allegations

that the Dixie Hospital is at the present time discriminating

on a racial basis and is not in compliance with the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. These allegations are not material to

this case and have been placed in the Appellants’ Brief to

confuse the issues and to prejudice the Court against the

hospital. Although it is recognized that these allegations

must be considered by the Court when it reads the A p

pellants’ Brief, nevertheless, it is hoped that the allega

tions will be disregarded in deciding this case. The issue of

whether or not the Dixie Hospital as in compliance with

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 should be left for the District

Court to decide after a trial of the companion suit with

full presentation of the evidence by both the plaintiffs

and the defendants.

STATEM ENT OF TH E FACTS

On April 14, 1965, the hospital moved the District Court

to dismiss the complaint for failure to state a claim upon

which relief could be granted. For purposes of that motion

the facts alleged in the complaint were admitted. The Dis

trict Court also considered the concessions of counsel in

their briefs and oral arguments. However, the factual and

legal conclusions urged by the nurses were not admitted

for purposes of the motion and were not, of course, binding

on the District Court.

The District Court, and not the appellants, stated the

material facts properly and fairly. It was conceded, and the

District Court found, that the Dixie Hospital had been the

recipient of federal funds under the Hill-Burton Act, 42

U.S.C. §291 h (b ) . On August 9, 1963 when the nurses’

5

alleged causes of action arose the Hill-Burton Act con

tained 42 U.S.C. §291e(f) and the implementing regula

tion 42 C.F.R. §53.112. That portion of the Hill-Burton

Act and the regulation were declared unconstitutional ap

proximately three months later on November 1, 1963 by

this Court in Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hos

pital, 323 F. 2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 376 U.S.

938 (1964).

The District Court found that prior to and on August

9, 1963 the Dixie Hospital maintained a cafeteria which

was reserved for white persons. Negro nurses were per

mitted to pass through the main cafeteria line but were

required to eat their meals in a separate room situated

down the hall from the main cafeteria. On August 8,

1963, the three plaintiffs ate lunch in said cafeteria. The

hospital’s assistant administrator reprimanded the plain

tiffs and advised them that they were violating a policy

of eighty years’ standing. On the following day, August

9, 1963, with full knowledge of the hospital’s policy and

regulation, plaintiffs again ate lunch at said cafeteria.

They were then discharged and, for the purpose of this

proceeding, the sole reason for said discharge was the

failure of the plaintiffs to adhere to the regulations of

the hospital and the orders of the assistant administrator.

On August 26, 1963, the plaintiffs, through their attorney,

requested reinstatement or, in the alternative, to be ad

vised of appellate procedure for reviewing their dismissal.

Bv letter dated September 4, 1963, counsel was advised that

plaintiffs would not be reinstated and that no appellate pro

cedure existed for reviewing dismissal orders. Plaintiffs

concede that the cafeteria was entirely desegregated several

months thereafter (on October 1, 1963). No proceedings

or requests were made by plaintiffs subsequent to the letter

of August 26, 1963. Smith, supra at 404.

6

The facts of this case, when viewed with hindsight in the

light of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which has been passed

in the interim, are not at all favorable to the defendants

by today’s standards. The District Court noted that, “we

are not presently called upon to commend or condemn the

actions of the defendants.” Even on August 8, 1963, when

the nurses were advised that their conduct was in violation

of the rules, regulations and policies of the Dixie Hospital,

which were well known and understood by them, the nurses

were told by the assistant administrator that he was not

discussing the rightness or wrongness, the correctness or

incorrectness of such rules, regulations and policies, but

that he was required to abide by and enforce the same.

But it appears that the facts found by the District Court

were not strong enough for the appellants. In an effort

to overwhelm the District Court the appellants filed a

purported motion attached to which were various docu

ments and affidavits. See Appellants’ Appendix at 54a-81a.

With regard to those “exhibits” the District Court said,

Id. at 84a-85a:

“The defendant’s motion for summary judgment was

fully argued on May 25, 1965, with a court reporter

present. No request was made to present additional

affidavits or exhibits. After receipt of briefs from

counsel the Court, because of the proximity of the

trial date, verbally advised counsel on July 1, 1965,

that the motion for summary judgment would be

sustained and further verbally advised counsel of the

reasons for said action, stating that a memorandum

was in the process of being prepared. No request was

7

made at that time to present additional affidavits or

exhibits. Thereafter, the memorandum granting sum

mary judgment was filed on July 20, 1965.

To now consider the affidavits and exhibits attached

to the ' ‘Motion” would, in effect, require a reopening

of the entire case. If this Court had acted hastily or

summarily, the request to reconsider would perhaps

be justified. But the record shows to the contrary. The

regular and ordinary processes of the Court are ap

plicable to all types of action, and the time to present

counter-affidavits in opposition to a motion for sum

mary judgment is not after the Court has ruled.

Irrespective of the affidavits and exhibits attached to

the “Motion” the fundamental principles guiding the

Court’s decision are not altered.

For purposes of this appeal, the appellants disregarded the

District Court’s findings and based their “Statement of

Facts” and their “Argument” almost entirely on these

“exhibits,” which they did not choose to offer in the regular

and ordinary manner for the District Court’s consideration,

but which they presented after the Court had ruled.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. If Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital

changed the law, were rights of action created retrospec

tively by that decision?

II. Are the nurses entitled to reinstatement with back pay

in this case ?

8

ARGUMENT

I. S IM K IN S v. M O SE S H. CONE M E M O R IA L

H O SP ITA L CHANGED TH E LAW AND NO RIGHT

OF ACTION WAS RETROSPECTIVELY CREATED

BY THAT DECISION.

Although the point was reserved for other courts, the

District Court assumed arguendo that an action against an

otherwise purely private corporation for an alleged wrong

ful discharge could be maintained in the federal courts. It

is submitted that such an action is not maintainable in the

federal courts under 28 U.S.C. § 1343 (3). However, since

the District Court did not deal with this point, it will not be

discussed further in this brief.1

The District Court ruled that the defendants, acting

under what was then determined to be “not state action”

and proceeding under what was assumed to be a valid statute

and regulation, were not liable for back pay and were not

required to reinstate the plaintiffs to their former positions.

For the purposes of this brief the point decided has been

broken down into two parts in order to show the correct

ness of that ruling:

I. Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital changed

the law and no right of action was retrospectively created

by that decision.

1 In the hearing on May 25, 1965, counsel argued that Simkins did not create

jurisdiction retrospectively. The point was also discussed in the supplementary

briefs filed after the hearing. See Defendants’ Supplementary Brief at 2-6 (made

part of the record on appeal but not printed.)

9

II. The nurses are not entitled to reinstatement with

back pay.

A. T H E LAW ON AUGUST 9, 1963, WAS CLEAR

THAT TH E DIXIE HOSPITAL WAS A PRIVATE

ENTITY AND THAT ACTION BY TH E ASSIST

ANT ADMINISTRATOR IN ENFORCING HOS

PITA L POLICIES WAS NOT UNLAW FUL “STATE

ACTION.”

The rules, regulations and policies of the Dixie Hospital

were well known to the three nurses and were understood

by them. Two of the nurses had been trained as student

nurses by the hospital before being employed as practical

nurses. The third nurse, Mildred M. Smith, had been in

termittently employed by the hospital for a number of years

as a registered nurse. The policy and practice of maintaining

segregated eating facilities had existed for a long time prior

to and during the nurses’ years of employment. If this or

any other policy were objectionable to these nurses, they

should have refused the hospital’s offer of employment. But

when they accepted the offer of employment they impliedly

agreed to abide by the rules and policies of the hospital, and

if they violated the rules and policies they knew that the

hospital would have the right to discharge them for cause.

Although there was no dispute over the material facts

in this case, the conclusions drawn from the facts were con

troverted. The nurses alleged that they were summarily dis

missed because they ate lunch in the main cafeteria, which

was reserved for white persons. The nurses disregarded the

fact that on August 8 and 9, 1963, other Negro employees

joined with them in eating in the cafeteria, but the other

10

employees were not discharged. These nurses and the other

employees were advised that they were violating policies

and they were requested not to repeat their action. In spite

of this, the nurses repeated their action and wilfully violated

the hospital s policy. Thereafter, they were discharged by

the assistant administrator for insubordination and for

their wulful and premeditated violation of hospital policies.

Since the other employees did not repeat their action, they

were not discharged and were permitted to return to duty.

The hospital alleged and the District Court found that the

sole reason for the nurses’ discharge was their failure to

adhere to the regulations of the hospital and the orders of

the assistant administrator.

The hospital’s regulations and the assistant adminis

trator s action were lawful acts by a private entity in

August, 1963. The District Court stated at 243 F. Supp

405-06:

‘At the times relating to the discharge of plaintiffs

the judicial decisions seemed to indicate that hospitals

receiving city and county funds were not so impressed

with “state action” as to require injunction under the

Fourteenth Amendment against racially discriminatory

practices. Such was the pronouncement of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in

Eaton v. Board of Managers of James Walker Mem.

Hospital, 4 Cir., 261 F. (2d) 521, cert. den. 359 U.S.

984, 79 S. Ct. 941, 3 L. Ed. (2d) 934, decided by the

Court of Appeals on November 29, 1958.

It was in this setting that the defendants acted on

August 9, 1963, in discharging the plaintiffs. We are

not presently called upon to commend or condemn the

11

actions of the defendants. But it cannot be seriously

contended that the law on the subject was anything

but favorable to the defendants during August and

September, 1963.”

The appellants argue that because of Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), and the decisions decided

under that case, state agencies have been on notice that they

are forbidden to discriminate racially. See Appellants’ Brief

at 11. From this, the appellants conclude, id at 12:

“The only issue was whether the Dixie Hospital was

sufficiently involved with government to be bound by

the Constitution. The Dixie Hospital between 1956

and 1959 accepted more than 1.9 million of the tax

payers’ dollars. Action by the Hospital thereafter

premised on the theory that it was unaccountable to

standards of conduct governing the public was surely

taken at its peril. This is particularly so where the

Hospital had no basis for a claim that it acted in

reliance on a prior precedent in its favor and should

be exempt from the surprise effects of a change of

law.”

The appellants’ basic contention is that Simkins v. Moses

H. Cone Memorial Hospital, supra, applied, rather than re

versed, prior law. The Simkins case, supra, involved Negro

physicians and dentists who were denied staff privileges, and

prospective Negro patients who were denied admittance to

the hospital. The claims of racial discrimination were

found to be clearly established. The case of Simkins v.

Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 211 F. Supp. 628

(M.D.N.C. 1962), was decided on December 5, 1962,

before the commission of the acts which gave rise to the

12

complaints of the three nurses in the present action. That

decision held that the mere receipt of funds under the

federal-state programs did not render a hospital subject to

the restraints of the Fourteenth Amendment against dis

crimination. The district court did not deem it necessary to

pass upon the constitutionality of 42 U.S.C. §291e(f). The

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

reversed Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital,

323 F. 2d 959, by a three to two decision, holding that the

degree of participation by national and state governments

was sufficient to find requisite “state action” and further

concluding that 42 U.S.C. §291e(f) and the implementing

regulation, 42 C.F.R. §53.112, were unconstitutional. The

opinion of the Court of Appeals was filed on November

1, 1963. Certiorari was denied, 376 U.S. 938, on March 2,

1964. In Simkins, this Court expressly relied upon and

applied prior decisions, especially Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715 (1961). The following

language from Burton was quoted with approval in

Simkins:

“It is clear . . . that ‘Individual invasion of individual

rights is not the subject-matter of the admendment,’

. . . and that private conduct abridging individual rights

does no violence to the Equal Protection Clause unless

to some significant extent the State in any of its mani

festations has been found to have become involved in it.

Because the virtue of the right to equal protection of

the laws could lie only in the breadth of its appli

cation, its constitutional assurance was reversed in

terms whose imprecision was necessary if the right

were to be enjoyed in the variety of individual-state

relationships which the Amendment was designed to

13

embrace. For the same reason, to fashion and apply a

precise formula for recognition of state responsibility

under the Equal Protection Clause is an ‘impossible

task’ which This Court has never attempted.’ Citation

omitted. Only by sifting facts and weighing circum

stances can the nonobvious involvemertt of the state in

private conduct be attributed its true significance”

(Emphasis in original.) 323 F. 2d at 966-67.

The appellants argue that Eaton v. Board of Managers,

supra, should have been confined to its own facts and was

erroneously applied by the district courts which dealt with

situations involving Hill-Burton hospitals, and they quote

the language of this Court in Simkins which distinguished

that case. See Simkins, supra at 96S-69. This Court stated

in Simkins, “In light of Burton, doubt is cast upon Eaton’s

continued value as a precedent.” Ibid at 968. Appellants

state that, “The Fifth Circuit had taken the same view of

the first Eaton case as early as May 17, 1962, when it

decided Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320,

323 (5th Cir. 1962). Appellants’ Brief at 15. But see

Simkins, supra at 976 (dissenting opinion). Based on

these considerations, the appellants conclude that the hos

pital has no basis for a claim that it acted in reliance on

prior precedents in its favor and should not be exempt

from the surprise effects of a change of law.

Prior to August, 1963, the issue of whether Hill-Burton

hospitals were instrumentalities of the state had been con

sidered on several occasions. A very recent decision prior

to August, 1963, was Wood v. Hogan, 215 F. Supp. 53

(W.D. Va. 1963), decided on March 12, 1963, which held

that governmental licensing, tax exemptions, and financial

assistance in construction were not sufficient to make a

14

private hospital an agency of the state, and therefore

subject to the Fourteenth Amendment. In that opinion

much of the significant language in Khoury v. Community

Memorial Hospital, 203 Va. 236, 123 S.E.~2d 533 (1962),

was quoted. That opinion also took note of Simkins v.

Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 211 F. Supp. 628

(M.D.N.C. 1962), and Eatton v. Board of Managers,

supra, and relied on those cases as precedents. It would be

purely academic to discuss and to quote the language of

the district court in Wood v. Hogcm. The federal cases,

Simkins, supra, and Eaton, supra, have since been reversed.

The case decided by the Supreme Court of Appeals of Vir

ginia, Khoury, supra, at this time has no value as precedent

for the proposition it supported in Wood. Furthermore,

that portion of the Hill-Burton Act (42 U.S.C. §291e(f))

which sanctioned segregation in hospitals was later de

clared unconstitutional, and the Civil Rights Act, as

amended in 1964, now forbids discrimination in Hill-

Burton hospitals. This decision was well reasoned, com

prehensively reviewed previous cases in point, considered

the language of the Hill-Burton Act, and, properly stated

the law which existed at that time.

On April 9, 1963. the case of Eaton v. Grubbs, 216

F. Supp. 465 (E.D.N.C. 1963), was decided.2 In that case,

it was contended that Burton had changed the standard

2 This case was reversed on April 1, 1964. See Eaton v. Grubbs, 329 F.2d

710 (4th Cir. 1965). Intervening decisions of the United States Supreme Court

and this Court, along with more detailed allegations of state involvement in this

proceeding were held to distinguish this case from the prior one involving the

same hospital.

15

for determining the presence of “state action.” The court

stated, 216 F. Supp. at 467:

“It is clear that Burton does not enunciate a funda

mental change in the law. The same general principles

were recognized, applied and limited to the particular

facts in the Eaton and Burton cases. Each case must

rest on its peculiar facts and no universal principle or

criteria for determining State action has yet been

established.”

The Court dismissed the complaint, finding that the new

facts alleged did not justify a different result than had

been reached in the first Eaton case, and that there had been

no fundamental change in the applicable law so that the

same decision was required in the present case under the

doctrine of stare decisis.

Judge Haynsworth’s vigorous dissent in Simkins, in

which Judge Boreman joined, demonstrates that the

Simkins decision was not an obvious result to be antici

pated after Burton was decided. After discussing and

distinguishing Burton, Judge Haynsworth stated that

other courts “have been unanimous in their conclusion

that the operation of such hospitals is not state action so

as to make applicable to them the provisions of the Four

teenth Amendment.” 323 F. 2d at 977, and he cited Khoury

v. Community Memorial Hospital, supra; Wood v. Hogan,

supra; and Eaton v. Grubbs, supra. In addition, Judge

Haynsworth pointed out, ibid, “On August 7, 1963, the

Senate rejected a proposal that henceforth grants in aid

to hospitals under the Hill-Burton Act be restricted to

hospitals which are desegregated and which practice no

discrimination on account of race.”

16

These considerations refute the appellants’ contention

that Simkins applied existing- law and that the result in

Simkins should have been anticipated by the hospital. On

the contrary, these considerations demonstrate the cor

rectness of the District Court’s conclusion stated at 243

F. Supp. 406:

“There is nothing in Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U.S. 715, decided in 1961, which would

give rise to the belief that the rule in Simkins was

forthcoming. That was a case in which an agency of

the State of Delaware constructed a parking facility

with a restaurant as an integral part thereof. The

entire building was a public structure, owned by a

public authority, and serving a public function. Even

to this date, following Simkins and the enactment of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it has not been said that

hospitals are “public” to the extent that the private

corporations operating same are converted into a public

body . . . it is unquestioned that, at the time these

causes of action now asserted by the plaintiffs arose,

the state and federal law was clear and plaintiffs had

no cause of action.”

B. ALTHOUGH L IN K L E T T E R v. W A L K E R AND

FLEM M ING v. SO U TH CARO LINA ELECTRIC &

G AS CO. ARE NOT CONTROLLING ON TH IS

CASE, TH EIR RATIONALES SERVE AS A GUIDE

IN ANSW ERING T H E IN ITIA L QUESTION PRE

SENTED.

In the recent case of Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618

(1965), the Supreme Court held that the exclusionary prin

ciple stated in Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961), did not

17

apply to state court convictions which had become final be

fore rendition of that opinion. The Supreme Court out

lined the history and theory concerning whether judicial

decisions should always be given retrospective effect. 381

U.S. at 6 . The Supreme Court favored the Austinian view

that judges do more than discover law; when a case is over

ruled, although the earlier decision was wrongly decided,

nevertheless that decision was a juridical fact until over

ruled, and rights which vested under that decision should

not be disturbed.

“The theory was, as Mr. Justice Holmes stated in

Kuhn v. Fairmont Coal Co., 215 U.S. 349, 371, 30

S.Ct. 140, 148 (1910), “that a change of judicial de

cision after a contract has been made on the faith of

an earlier one the other way is a change of the law ”

381 U.S. at 6 .

Justice Cardozo applied the Austinian approach in order to

avoid “injustice and hardship” and he ruled that courts have

the power to say that decisions though later overruled “are

law none the less for intermediate transactions.” See Great

Northern Ry. v. Sunburst Oil & Refining Co., 287 U.S.

358 (1932) at 364. Justice Hughes stated the guidelines

that the Supreme Court applied in Linkletter in the follow

ing language:

“The courts below have proceeded on the theory that

the Act of Congress, having been found to be un

constitutional, was not a law; that it was inoperative,

conferring no rights and imposing no duties, and

hence affording no basis for the challenged decree.

(Citations omitted) It is quite clear, however, that

such broad statements as to the effect of a determina

18

tion of unconstitutionality must be taken with qualifi

cations. The actual existence of a statute, prior to

such a determination, is an operative fact and may

have consequences which cannot justly be ignored.

The past cannot always be erased by a new judicial

declaration. The effect of the subseqent ruling as to

invalidity may have to be considered in various

aspects, with respect to particular relations, individual

and corporate, and particular conduct, private and

official. Questions of rights claimed to have become

vested, of status, of prior determinations deemed to

have finality and acted upon accordingly, of public

policy in the light of the nature both of the statute

and of its previous application, demand examination.

These questions are among the most difficult of those

which have engaged the attention of courts, state and

federal, and it is manifest from numerous decisions

that an all-inclusive statement of a principle of ab

solute retroactive invalidity cannot be justified.” Chicot

County Drainage Dist. v. Baxter State Bank, 308

U.S. 371 (1940) at 374.

The Supreme Court concluded in Linkletter that neither

the Constitution nor any other body of law required or pro

hibited a court from applying a decision retrospectively.

A court must weigh the merits and demerits in each case

by looking to the prior history of the rule in question, its

purpose and effect, and whether retrospective operation

would further or retard its operation, before deciding

whether or not the rule should be applied retrospectively.

In the case of Flemming v. South Carolina Electric &

Gas Co., 239 F. 2d 277 (4th Cir. 1956) at 279, this Court

19

considered a similar problem concerning the retrospective

effect of new judicial interpretations.3 The primary dis

tinction between Flemming and this case is one of form

and not of substance. In Flemming, a bus driver acted to

enforce a state statute; in this case, the assistant adminis

trator acted to enforce a hospital policy. By substituting

the word “policy” for the word “statute” in the text of the

opinion, one might then inquire if Flemming is applicable

to this case. In the language of Flemming the question

in this case becomes whether action taken under a policy

valid under the constitutional doctrine (judicial decisions)

prevailing at the time it was taken is protective from civil

responsibility where the policy is subsequently declared un

constitutional.4 In Flemming, this Court said supra, at

279, “Here the only basis upon which the statute could be

sustained, the separate but equal doctrine, had been re

pudiated by the Supreme Court prior to the commission

of the act constituting the ground of liability.” In Flem

ming, the state statute was plainly unconstitutional at the

time the cause of action arose; in the present case, the

policy under attack was plainly valid under judicial de-

3 That action was for damages for alleged violation of civil rights, and in

volved a bus driver who required a Negro passenger to change her seat in

accordance with the segregation statutes then in force in South Carolina. The

Court, however, decided that at the time of the bus driver’s acts there could

be no doubt that the “separate but equal’’ doctrine of Plcssy v. Ferguson, 163

U .S. 537 (1896), had been generally repudiated by prior opinions of the

Supreme Court in the school cases of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 (1954) ; and Bolling v. Sharpe, 347, U .S. 497 (1954).

4 This case does not involve an act in reliance on a policy, subsequently

declared unconstitutional, which would otherwise subject a person to liability.

See 16 A m. J ur. 2d, “Constitutional Law” §178 (1964). An employer has the

legal right to discharge his employee with or without cause. The employee

would then have a right to sue his employer for breach of the employment

contract. Therefore, the act of the assistant administrator was not one which

would othenvise subject him to liability.

20

cisions in existence at the time the causes of action arose.

In Flemming, the plainly unconstitutional statute acted on

was not a complete defense to liability, but was to be con

sidered by the jury on the issue of damages. The circum

stances in this case are such that the plainly valid policy

acted on should be a complete defense to this action. Based

on the circumstances in this case as applied to the language

in Flemming, this Court should find that there was no

unlawful state action to render the defendants civilly re

sponsible for an act done in reliance on the constitutional

doctrine prevailing at the time.

The initial question in this case is whether the conduct

of the assistant administrator of the Dixie Hospital in

August, 1963, when he discharged the nurses, constituted

unlawful state action which subjects the hospital to li

ability. It is not disputed that similar conduct after No

vember 1, 1963, i.e. after Simkins had been decided, would

constitute the requisite state action to give this Court

jurisdiction to enjoin future acts of unlawful racial dis

crimination and to award damages for violation of civil

rights arising out of such discrimination occurring after

November 1, 1963. In Simkins, and Eaton v. Grubbs, supra,

decided thereafter, the claims of racial discrimination were

found to be clearly established. Such discrimination ap

parently was being practiced at the time of those decisions

and continued until the appropriate injunctions were issued

by the district courts. Therefore, this Court could have

applied its interpretation of what constitutes state action

in a constitutional sense, to the discrimination practiced by

the hospitals on the same day the cases were decided. The

purpose of the Simkins and Eaton decisions was to end

racial discrimination in Hill-Burton hospitals, not to punish

21

past acts of discrimination. The basic result reached in

these decisions was to give prospective effect to the de

cisions by granting injunctive relief which necessarily

looks to the future.5 In other words, this Court said, in

effect, that since this conduct is unlawful state action, the

hospitals may not continue to discriminate on a racial basis

in the future. The purpose of the Simkins and Eaton de

cisions would not be furthered in any way by giving

retrospective effect to the decisions. See Linkletter v.

Walker, supra. Similarly, the Civil Rights Act, as amended

in 1964, was not given retroactive effect. It is submitted

that this Court would not have given retrospective effect to

its decisions, for example, by granting damages or impos

ing a fine for past violations of the plaintiffs’ civil rights

by the hospitals. Such a result would have been harsh and

unwarranted, and such relief would not have been granted

where it appeared that the hospitals acted in good faith

under the judicial decisions and statutes enabling them to

operate as private entities. The action by the assistant ad

ministrator of the Dixie Hospital was lawful in August

of 1963, and it would be unjust to now hold that that

conduct has changed to unlawful state action for which

the hospital is liable. To so hold would be to encourage

civil disobedience of all existing laws, and to discourage

responsible persons from enforcing laws that are supposedly

valid.

The existence of the judicial decisions heretofore cited

as well as the statute and implementing regulation, all of

which demonstrate that Simkins was a change in the law,

5 These rulings were not purely prospective since they were applied to the

parties before the Court. A ruling which is purely prospective does not apply

even to the parties before the Court. See Linkletter v. Walker, supra, at

22

is an operative fact and has consequences which cannot

justly be ignored. See Chicot County Drainage Dist. v.

Baxter State Bank, supra. The fact that numerous Hill-

Burton hospitals conducted themselves as private entities

and in the belief that their acts were not official state action

must be considered. The particular relations involved in this

case should be considered. The Dixie Hospital was a cor

porate entity which performed services in the public in

terests and action taken by the entity was believed to have

been private. The status of the parties in this case, that of

employer-employee, involved a contractual relationship in

which the rights of the parties had vested under the law

which existed at the time the contract was made. It would

be unjust to destroy these rights and change the status of

the parties by a subsequent change in the law. Ibid.

Wherever there was segregation in the past, there was

discrimination which under today’s statutory law and

judicial decisions would be unlawful. Surely this Court

does not intend to create a cause of action for every person

so wronged and to now allow him to bring an action for

damages. Obviously, such a result would retard the ad

ministration of justice by flooding the courts with litigation

over causes of action which arose many years ago. The

past cannot always be erased by a new judicial declaration.

See Linkletter v. Walker, supra.

For the foregoing considerations, the District Court

properly concluded at 243 F. Supp. 406:

“Weighing the merits and demerits in this case and

considering the status of the parties at the time the

alleged cause of action arose, we think that public

policy dictates that, whatever may be the rights of a

23

Negro discharged from employment following the de

cision in Simkins by the Court of Appeals and the

subsequent denial of certiorari, together with the

passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964, no rights

are created which should be accorded retrospective

effect.”

II. TH E NURSES ARE NOT ENTITLED TO RE

INSTATEM ENT W ITH BACK PAY

The appellants were employed as nurses by the Dixie

Hospital and their salaries were fixed on a monthly basis.

A contract for a monthly salary not specifying any definite

term may be terminated by either party at the end of a

month. Even where there is a contract of service for a

definite time, an employer who discharges an employee is

responsible in damages merely for violating the contract;

having the right to discharge, the employer thereby subjects

himself to liability for breach of contract unless good cause

for discharge exists, in which case he incurs no liability as for

breach of contract. See 35 A m . J u r . Master and Servant

§34 (1941).

This suit is allegedly an action to redress the depriva

tion by state action of rights, privileges and immunities

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States and by 42 U.S.C. §1981 which pro

vides for the equal rights of all persons as follows:

“All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit

of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons

24

and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall

be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes,

licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.

R.S. §1977.”

Section 1983 of the same Title states:

“Every person who, under color of any statute, ordi

nance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or

Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any

citizen of the United States or other person within the

jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights,

privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution

and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an

action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceed

ing for redress. R.S. §1979.”

Section 1983 authorizes actions at law, suits in equity, or

other proper proceedings for redress. The Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure govern the procedure in all suits of a

civil nature whether cognizable as cases at law or in

equity. The federal statute making actionable the depriva

tion of civil rights under color of state law (42 U.S.C.

§1983) does not extend the sphere of federal equitable

jurisdiction with respect to what shall be held appropriate

subject matter for that kind of relief; it allows a suit in

equity only when what is the proper proceeding for re

dress, and refers to existing standards for a determination

of what is such a proceeding. See Giles v. Harris, 189

U.S. 475 (1903). In considering the right to injunctive

relief in a suit under 42 U.S.C. §1983, the Court applies

the ordinary principles of equity, determining whether

25

the plaintiff has shown irreparable damage in the absence

of a plain, adequate and complete remedy at law. See 15

A m . J u r . 2d “Civil Rights” §70 (1964).

Civil rights are all those rights which the law gives a

person or which the law will enforce. Civil rights embody

also the right to enjoyment of such guaranties as are

contained in constitutional or statutory law. No such rights

have been denied to these plaintiffs by these defendants.

There is no vested right to employment in public or private

occupations in the absence of special circumstances not

here present. The plaintiffs had the right to bring suit to

determine the validity of the offensive policies of the

hospital either by an action for declaratory judgment

or an injunction. They had the same civil rights as any

white person, but they did not have more or greater rights,

which they would appear to have, if they are granted the

relief sought in this case.

The appellants have been unable to cite any authority

which indicates that employees of a private corporation

which performs a public function in the public interest

have a right to be reinstated after being wrongfully dis

charged. The cases cited by the appellants in their Brief

involve the National Labor Relations Board and either

federal, state or municipal employment. Seen generally 15

A m . J u r . 2d, “Civil Rights” § 56-62 (1964). This case

involves private employment. Each of the cited cases in

volved an unconstitutional condition precedent to the em

ployment contract. When those persons refused to perform

the conditions precedent they were barred from employ

ment or discharged. When these conditions precedent to

the employment contract were declared unconstitutional,

the bar to employment was removed and the wrongfully

26

discharged employees were entitled to reinstatement in

their public avocation. There was no other reason to bar

their employment. In this case the condition precedent to

employment was that employees obey hospital rules and

policies. This implied condition was initially accepted by

the plaintiffs and then breached at a later date. In the

cited cases the prospective employees never accepted or

performed the offensive conditions to employment. They

preferred no employment to employment under the of

fensive conditions existing. Obviously this was not the

situation in this case.

In the complaint in this case a letter from William

Alfred Smith, plaintiffs’ attorney, to William C. Walton,

a defendant in this case, is set forth. The following

pertinent language is found in that letter:

“On August 9, 1963, I am advised, Mrs. Smith, a

registered nurse, Miss Stokes, a licensed practical

nurse, and Miss Taylor were discharged from their

employment with Dixie Hospital solely because they

ate in the staff cafeteria rather than in a converted

classroom which has been set aside as a dining room

for Negro nurses . . . This letter is written to you in

an effort to rectify this matter at this level. I hereby

request that you take prompt action in reinstating the

said three nurses with retroactive pay. In the alter

native, you may advise me of the appellate procedure,

if any, which you have at your institution for the

redress of employer-employee matters of this nature.”

27

The “redress of employer-employee matters of this nature”

is no longer acceptable to the individual plaintiffs. They are

not content to request relief based on well established

theories of contract and master-servant law as other in

dividuals should and would.

There is no right to equitable relief in this action. The

Civil Rights Act has not extended the basic principles of

equitable jurisdiction. The authority cited in support of

granting reinstatement is not in point and there is no

authority to the effect that plaintiffs may be reinstated

with back pay under similar facts and conditions. The

hospital’s receipt of federal funds did not convert an other

wise private employment contract into public employment.

There are sound reasons why such relief has not been

granted in the past and should not be granted in this case.

Many difficult problems would be presented and hardships

imposed. If this Court affords the equitable relief sought

in this case, whom will it order the defendants to discharge

so that these plaintiffs may be reinstated? What will be the

terms of their re-employment contract? Will they be

“privileged characters” who can’t be discharged at the

end of each month at the will of their employer ?

The nurses have not shown irreparable damage in the

absence of a plain, adequate and complete remedy at law and

the District Court correctly decided that the hospital was

not liable for back pay and was not required to reinstate

the nurses to their former positions.

28

CONCLUSION

The District Court properly ruled that Simkins v.

Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, supra, changed the

law. After weighing the merits and demerits in this case

and considering the status of the parties at the time the

alleged cause of action arose, the District Court con

cluded that public policy dictated that no rights were

created by Simkins which should be accorded retrospective

effect, and that therefore the appellants were not entitled

to reinstatement with back pay.

Wherefore, for the foregoing reasons, the appellees

pray that the Court of Appeals will affirm the judgment

below.

Respectfully submitted,

E. R a l p h J a m e s

W. S t e p h e n M o o r e

Attorneys for Appellees

J a m e s , R i c h a r d s o n & J a m e s

Citizens and Marine Bank Building

Hampton, Virginia

Of Counsel: