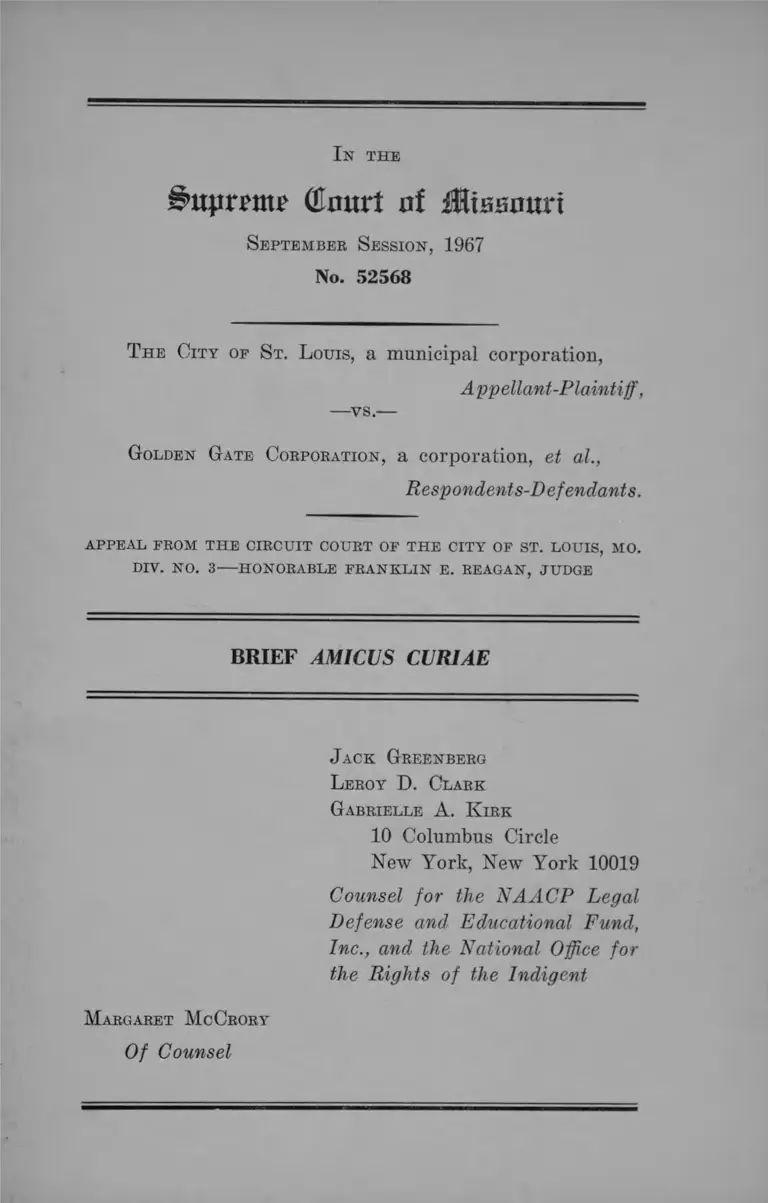

St. Louis City v Golden Gate Corp Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1967

21 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. St. Louis City v Golden Gate Corp Brief Amici Curiae, 1967. 936fd979-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e968ae7f-21b1-4f36-8639-aa429657c8ce/st-louis-city-v-golden-gate-corp-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

^ujirrmr GImtrl uf Missouri

September Session, 1967

No. 52568

T he City oe St. L ouis, a municipal corporation,

—vs.—

Appellant-Plaintiff,

Golden Gate Corporation, a corporation, et al.,

Respondents-Defendants.

APPEAL FROM THE CIRCUIT COURT OE THE CITY OF ST. LOUIS, MO.

DIV. NO. 3---- HONORABLE FRANKLIN E. REAGAN, JUDGE

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

J ack Greenberg

Leroy D. Clark

Gabrielle A. K irk

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and the National Office for

the Rights of the Indigent

Margaret McCrory

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Points and Authorities .................................................... 1

A rg u m e n t—

I. The City of St. Louis Is Not Prohibited by the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution from

Enacting and Enforcing an Ordinance Author

izing the Appointment of a Receivership to

Rehabilitate Residential Property Which Con

stitutes a Danger to Life, Safety, and Health 4

II. Ordinance No. 53995 Is Not an Unconstitu

tional Delegation of Legislative Functions to

the Judiciary ........................................ 11

III. Ordinance No. 53995 Is Not an Unconstitu

tional Delegation of Legislative Function to

Administrative Officers ....................................... 13

IV. Ordinance No. 53995 Is Not Invalid on the

Ground of Inconsistency With State Law or

Preemption of Powers Exercised by and Re

served to the State ............................................ 15

Certificate of Service 18

I n the

^uprrmr (tort of Missouri

September Session, 1967

Action No. 52568

T he City of St. L ouis, a municipal corporation,

Appellant-Plaintiff,

—vs.—

Golden Gate Corporation, a corporation, et al.,

Respondents-Defendants.

APPEAL FROM THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE CITY OF ST. LOUIS, MO.

DIV. NO. 3---- HONORABLE FRANKLIN E. REAGAN, JUDGE

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

Amicus accepts the jurisdictional statement and state

ment of facts as stated in the brief of appellant.

POINTS AND AUTHORITIES

I.

THE CITY OF ST. LOUIS IS NOT PROHIBITED BY

THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITU

TION FROM ENACTING AND ENFORCING AN ORDI

NANCE AUTHORIZING THE APPOINTMENT OF A

RECEIVERSHIP TO REHABILITATE RESIDENTIAL

PROPERTY WHICH CONSTITUTES A DANGER TO

LIFE, SAFETY, AND HEALTH.

Thomas Cusack v. Chicago, 242 U.S. 526, 531;

Queenside Hills Realty Co. v. Saxl, 328 U.S. 80

(1946);

2

Reinman v. Little Rock, 237 U.S. 171;

Euclid v. Ambler Realty Company, 272 U.S. 365

(1926);

8 ampere v. New Orleans, 166 La. 775, 117 So.

827 (1928), affirmed per curiam 279 U.S. 812

(1929);

Rerman v. Parker, 348 U.S. 26 (1954);

In the Matter of the Department of Buildings,

14 N.Y. 2d 291, 200 N.E. 2d 432 (1964);

Central Savings Bank v. New York, 279 N.Y.

266, 18 N.E. 2d 151 (1938).

II.

ORDINANCE NO. 53995 IS NOT AN UNCONSTITU

TIONAL DELEGATION OF LEGISLATIVE FUNCTIONS

TO THE JUDICIARY.

State ex rel. Orr v. Kearns, 264 S.E. 775 (1924).

III.

ORDINANCE NO. 53995 IS NOT AN UNCONSTITU

TIONAL DELEGATION OF LEGISLATIVE FUNCTION

TO ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICERS.

Schecter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295

U.S. 495 (1935);

Panama Refining Co., et al. v. Ryan, 293 U.S.

388 (1934);

International Railway Co. v. Public Service Com

mission, 36 N.Y.S. 2d 125 (1942), aff’d without

opinion, 289 N.Y. 830 (1943);

New York Central Securities Corporation v.

United States, 287 U.S. 12 (1932);

3

State of Oklahoma v. Parham, 412 P.2d 142

(1966);

State of Wisconsin v. Whitman, 220 N.W. 992

(1928);

West Central Producers Co-operative Associa

tion v. Commissioner of Agriculture, 20 S.E.

2d 797 (W. Ya. 1942);

Financial Aid Corporation v. Wallace, 23 N.E.

472 (Ind. 1939);

Dickerson, et al. v. Commonwealth, 181 Va. 313,

24 S.E. 2d 550 (1943).

IV.

ORDINANCE NO. 53995 IS NOT INVALID ON THE

GROUND OF INCONSISTENCY WITH STATE LAW

OR PREEMPTION OF POWERS EXERCISED BY AND

RESERVED TO THE STATE.

Vest y . Kansas City, 194 S.W. 2d 38 (1946);

City of Maryville v. Wood, 216 S.W. 2d 75

(1948);

Passler v. Johnson, 304 S.W. 2d 903 (1957);

Bushman v. Bushman, 279 S.W. 122 (1925).

4

A R G U M E N T

I.

THE CITY OF ST. LOUIS IS NOT PROHIBITED BY

THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITU

TION FROM ENACTING AND ENFORCING AN ORDI-

NANCE AUTHORIZING THE APPOINTMENT OF A

RECEIVERSHIP TO REHABILITATE RESIDENTIAL

PROPERTY WHICH CONSTITUTES A DANGER TO

LIFE, SAFETY, AND HEALTH.

The central question raised by this appeal is whether

the City of St. Louis in utilizing a receivership ordinance,

has unduly invaded the right of the appellee to have un

fettered control over privately-owned residential property

which is alleged to have extensive violations of the Mini

mum Housing Code.

The general rule is that legislation controlling the use

of property is a constitutional exercise of the police power

unless “ it is plain and palpable that it has no real or

substantial relation to the public health, safety, morals or

to the general welfare” . Thomas Cusack v. Chicago, 242

U.S. 526, 531. The reasonableness of the relationship de

pends upon a weighing of the extent of the deprivation of

property against the importance of the governmental in

terest sought to be protected and the degree to which the

challenged legislation is calculated to promote that interest.

Queenside Hills Realty Co. v. Saxl, 328 U.S. 80 (1946);

Reinman v. Little Rock, 237 U.S. 171.

The rapid growth of American cities in the last six

decades has been accompanied by a substantial increase

in the number and size of slums and blighted areas, and

5

by a serious lack of adequate housing. There is also ade

quate proof that these conditions are productive of a dis

proportionate increase in crime, disease, fire, and difficulty

in providing public services.1

A wide range of programs have been sustained as consti

tutional means of abating and averting these slum condi

tions including zoning ordinances Euclid v. Ambler Realty

Company, 272 U.S. 365 (1926); building and housing codes

Sampere v. New Orleans, 166 La. 775, 117 So. 827 (1928),

affirmed per curiam 279 U.S. 812 (1929) and condemnation

under Urban Renewal programs, Berman v. Parker, 348

U.S. 26 (1954). All of these programs involved extensive

control over the private ownership of property but they

were all upheld as proper exercises of the police power

to protect the public health and safety. Receivership of

slum housing has been adopted in six states as a supple

ment to the above programs.2 None of these receivership

statutes have been held unconstitutional. In New York,

one of the states which has had the most extensive use of

receivership, the statute has recently been upheld against

claims that it was unconstitutional. In the Matter of the

Department of Buildings, 14 N.Y. 2d 291, 200 N.E. 2d 432

(1964) .

Appellees’ motion to dismiss asserts that the City of

St. Louis has other adequate remedies at law which bar

the use of the equitable remedy of receivership. This is

also an argument that use of the receivership ordinance

1 See generally, A Sliorr, Slums and Social Insecurity (U.S. Depart

ment of Health, Education and Welfare, Research Report No. 1, 1963);

Johnstone, The Federal Urban Renewal Program, 25 University of

Chicago Law Review 301, 304 (1958).

2 Conn. Gen. Stat. Annot. Sec. 19-3476 (1965); Laws o f Indiana,

Chapter 243 (1967); Annot. Laws of Mass., Chapter 111, Section 127 H

(1965) ; New Jersey Laws 2A:42-80 et seq. (1966); N.Y. Multiple Dwell

ing Law Sec. 309; 111. Rev. Stat. Chapter 24 Sec. 11-21-2 (1965).

6

is an “unreasonable” and unconstitutional deprivation of

property, because there are alternatives which interfere

less with ownership rights. However, it is precisely be

cause the usual legal remedies fail to fully correct aggra

vated housing disrepair, that many municipalities have

had to resort to receivership.

The City of St. Louis has three legal remedies: (1)

quasi-criminal prosecution, (2) condemnation of buildings

unfit for human habitation with an order for all tenants

to vacate, and (3) establishing a special tax to operate as

a lien to recoup the expenditures for repairs made by the

city. Studies have shown that criminal prosecution of land

lords for violations of a Housing Code has generally proved

unfruitful, in part because of judicial reluctance to place

heavy penalties on landlords whose buildings vary little

from the neighborhood norm.3

If a conviction results in a small fine, the landlord treats

it as a cost of doing business which is less expensive than

making the needed repairs. If the fines are large, it pre

cludes compliance because the violator’s available capital

is reduced. In either event, financial resources are being-

taken by the municipality and are not being used to cor

rect the violations. Jailing the violator is likewise an in

efficient way of coercing the landlord, without directly

achieving repair. The second remedy of ordering tenants

to vacate a building, cannot be used regularly in a city

which already has a housing shortage. Also, vacated build

ings are themselves a serious blighting influence—vandals

are attracted thus making repair even more difficult. More

over, in a housing shortage this remedy is usually limited

to buildings that are structurally unsound, where there

is a clear need for emergency evacuation. Receivership on

3 See Lehman, Building Codes, Housing Codes and the Conservation

of Chicago’s Homing Supply, 31 U. Chi. L. Rev. 180 (1963).

7

the other hand was designed to cope with the entirely

different problem of taking structurally sound buildings

and making them habitable by quick repairs.

Repair by the Building Department with city funds and

recoupment through a lien places the burden on the city

initially to have the financial resources to cope with de

terioration created by the refusal of landlords to use in

come from their property to maintain it in a lawful state.

To the extent that its resources are limited, property in

need of immediate repairs will not receive it. Only re

ceivership provides direct access to the income from the

property to correct the Code violation. Such a city-repair

program may involve the Buildings Department too deeply

in real estate management with a limited staff. Under

the receivership program, the court could appoint private

receivers with adequate experience in the management of

property. Thus, neither of the legal remedies available

to the City of St. Louis is adequate to the task of achieving

immediate correction of Housing Code violations.

Receivership is also most appropriate in the instant case

where the city is prepared to prove a pattern of landlord

refusal to correct Code violations. The appellee here has

been fully informed of the violations on the property and

has, for at least a 60-day period thereafter, refused to

correct those violations. The appointment of a receiver

by the court to receive the rents and supervise the repair

is the only adequate response to the actively recalcitrant

landlord.

We have spoken above of the general constitutional au

thority for a municipality to use its police power to deal

with housing conditions which threaten the public safety

and health. There are, however, particular constitutional

problems under due process of law and impairment of

contracts, which are associated with the receivership

8

remedy. The due process problems contain two elements:

notice to all parties who have an interest in the property

and the right to participate in a hearing on the necessity

of the appointment of a receiver and the reasonableness

of the expenditures for rehabilitation. The impairment

of contract issue involves the question of whether the

municipality can constitutionally establish a lien on the

rents which is prior to that of the mortgagee.

The early case of Central Savings Bank v. New York>

279 N.Y. 266, 18 NE 2d 151 (1938) raised all of these

questions and held that the New York law was void be

cause there was no provision for notice of the proceedings

to the mortgagee or for affording him an opportunity to

be heard as to the necessity for repairs or the reasonable

ness of expenses incurred in making them. The court also

found that the subordination of the mortgagee’s lien to

the city’s lien for repairs, was an unconstitutional impair

ment of contract rights because the owner could not have

achieved such a subordination of the mortgagee’s interest

by making the repairs himself.

In the Matter of Department of Buildings of the City,

of New York, supra is the major case on the constitu

tionality of a receivership statute. There the parties as

serting the unconstitutionality of the receivership statute

relied heavily on the Central Savings Bank case and the

court fully responded to all of the constitutional claims

raised in that case. The court held that the receivership

statute which was passed after the Central Savings Bank

case had fully remedied the procedural deficiencies cited

there, since the mortgagee received notice and a right

to participate in the proceedings.4 On the issue of the

impairment of contract rights, the court stated:

4 The St. Louis Receivership ordinance has none o f these procedural

deficiencies, for all parties with any interest in the property are given

notice and participate in the proceedings as co-defendants. Ordinance

No. 53995, Section 2.

9

When weighed against the vital public purposes sought

to be achieved, the interference with the mortgagee’s

rights resulting from the present law may not be said

to be so unreasonable or oppressive as to preclude

the State’s exercise of its police power. It is worth

remarking that if the mortgagee’s lien may not be

subordinated to the extent provided—that is by post

poning his right to collect rents from the property or

to effect a discharge of the receiver until the cost in

curred by the receiver on behalf of the municipality

in removing the dangerous conditions has been repaid

—the result would be that the State must permit slum

conditions to continue unabated or alternatively either

condemn unsafe buildings and thereby aggravate the

acute housing shortage or continue making improve

ments with, however, a lien subordinate to previously

recorded mortgages. To insist upon the last course,

not only would result in a gratuitous addition to the

security of prior encumbrances but would undoubtedly

render the operation financially impossible.

. . . The same public interest which supports the stat

ute when directed against the owner, even though it

impinges on his right to deal freely with his property,

equally justifies the legislation as a reasonable exer

cise of the police power insofar as it affects the right

of the mortgagee.

If the legislation before us is addressed to a legiti

mate end, the measures taken are reasonable and ap

propriate to that end ‘it may not be stricken as un

constitutional even though it may interfere with rights

established by existing’ contracts. Home Bldg. & Loan

Assn. v. Blaisedell, 290 U.S. 398, 438, 54 S. Ct. 231,

240, 78 L. Ed. 413.

10

The court noted that a further justification for the re

ceivership statute lies in the current slum conditions:

It is likewise clear—turning to the second of the con

stitutional defects noted in the earlier statute—that

the Central Savings Bank decision may not be relied

upon to invalidate the 1962 statute on the ground

that it effects an unconstitutional impairment of the

mortgagee’s contractual rights. We assess the pro

priety and reasonableness and by that token, the valid

ity of an exercise of the police power in light of the

conditions confronting the legislature when it acts

and it can hardly be questioned that the situation in

terms of the shortage of safe and adequate dwelling

units, which prompted the 1962 amendment (L. 1962,

ch. 492 §1) presented a far more serious emergency

than that existing in 1937.

The City of St. Louis, like New York City and most

other large cities in the 1960’s, has a severe slum problem:

Out of 262,984 housing units, approximately 20% (46,376)

of them are classified as “deteriorating,” and another 5%

(11,538) are in a more serious state of disrepair being

classified as “dilapidated.” 5 In the face of such a serious

housing blight, the receivership ordinance is clearly a valid

measure to protect tenants from the consequent dangers

to life, health, and safety.

5U.S. Census of Housing: 1960, Table 12, page 27. This report also

indicates that non-whites occupy 36% (16,911) o f the housing classified

as deteriorating and 43% (5,064) o f the housing classified as dilapidated.

Table 38, pages 27-140.

11

II.

ORDINANCE NO. 53995 IS NOT AN UNCONSTITU

TIONAL DELEGATION OF LEGISLATIVE FUNCTIONS

TO THE JUDICIARY.

In point 8 of their motion to dismiss, Golden Gate Cor

poration contends that Ordinance No. 53995 (hereinafter

referred to as No. 53995) is unconstitutional and void in

that it delegates legislative authority and power to the

judiciary without sufficient standards given the court to

determine: “ (1) whether or not a receiver should be ap

pointed; (2) the purpose, if any, other than placing the

property in the custody of the court; (3) the necessity

of the receivership; (4) the powers, rights and duties

of the receiver; (5) the duration of the receivership; (6)

and the ultimate disposition of the property. (See Para

graph IV of Golden Gate’s memorandum in support of its

motion to dismiss.) Amicus submits that this contention

is completely without legal or factual basis.

No. 53995 provides for the appointment of a receiver

upon the application of the building commissioner or the

health commissioner if it appears to either commissioner

that the “safety, health or welfare of persons on, about

or near said premises has been or will be endangered by

the condition thereof.” Such a request is only made if an

owner of a building fails to comply within sixty days with

an order of either commissioner to correct one or more

violations of the Revised Code of the City of St. Louis.

The question of whether or not a receiver should be ap

pointed is properly a judicial determination which will be

made after a finding that endangering conditions exist,

and that the landlord has failed to correct those conditions.

It is clear on the face of No. 53995 that the purpose of

the receivership is “to collect all rents and profits accruing

12

from said property . . . and make any necessary repairs

thereto.” The powers, rights and duties of the receiver

are also made explicit by the statute. Although there is

no specific timetable indicating the duration of the re

ceivership, it is implicit that since the purpose of said

receivership is to correct code violations, the necessity

ceases when the condition is remedied and that in the

exercise of its broad discretion the court could and would

declare that the receivership had terminated.

Since there is no transfer of title involved, the property

is not, in a legal sense, returned to the owner since he

never lost it. However, after the purposes of the receiver

ship have been accomplished, it is obvious that the owner

would again resume complete control over the property.

This ordinance differs from the statute which was in

validated in State ex rel. Orr v. Kearns, 264 S.W. 775

(1924). In that case, the court was empowered to close a

bawdy house found to be a nuisance “for a reasonable

length of time as it seems just and wise to the court.” It

is clear that in that instance the court was without any

standard to guide them in a determination of the length

of time that the bawdy house would be closed. However,

No. 53995 has for its purpose the elimination of code vio

lations which endanger the safety, health or welfare of per

sons, and the appointment of a receiver is one way of ac

complishing this result. When this result is accomplished,

the receivership ceases.

The nature of the legislative process is to make statu

tory declarations as to what is unlawful. It is the province

of the judiciary to determine whether a particular factual

situation comes within the strictures of that declaration.

Certainly, the legislature should not be expected to foresee

all possible circumstances involving code violations that

might endanger the safety, health, or welfare of persons.

13

The judiciary is uniquely equipped to decide whether in a

given factual circumstance (which will often vary) the

existence of code violations, ignored by the owner, makes a

building dangerous to the safety, health, or welfare of

persons, necessitating the appointment of a receiver.

III.

ORDINANCE NO. 53995 IS NOT AN UNCONSTITU-

TIONAL DELEGATION OF LEGISLATIVE FUNCTION

TO ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICERS.

Somewhat analogous to the appellee’s contention re

ferred to in Argument II is point 18 of the motion to dis

miss in which it is contended that No. 53995 is an uncon

stitutional and void delegation of legislative functions to

an administrative officer without setting up sufficient stan

dards for his guidance. Amicus again submits that this

contention is unfounded.

It has long been recognized that administrative officers

or agencies should be invested with control over those

matters for which they have peculiar expertise. When

such control is given by the legislature, admittedly, certain

standards must be provided so that the officers can prop

erly carry out the legislative policy. However, the specific

ity of such standards has been, generally, liberally con

strued. Delegations by Congress have only been held un

constitutional in two cases by the Supreme Court. See

Schecter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495

(1935), and Panama Refining Co., et al. v. Ryan, 293 U.S.

388 (1934).

A number of state courts have refused to invalidate

statutes investing administrative officers or agencies with

authority, notwithstanding the minimal amount of stan

dards provided by the legislature. In International Rail

14

way Co. v. Public Service Commission, 36 N.Y.S. 2d 125

(1942), aff’d without opinion, 289 N.Y. 830 (1943), the

Public Service Commission was authorized to disapprove

contracts entered by utilities if it found that they were

“not in the public interest.” In upholding this authority

invested by the state legislature, the court “conceded that

a criterion of ‘public interest’ standing alone presents a

standard of immense and varied implication.” But when

it “construed [this term] with reference to the general

purposes and the subject matter of the Public Service

Law,” it found that “ ‘public interest’ is directly related

and limited to the general purposes of such law . . . [and]

it is a sufficient guide.” The court cited New York Central

Securities Corporation v. United States, 287 U.S. 12 (1932),

in support of its position. Finally, the court held that

“ the legislature is not required to furnish details but only

to provide a general guide for administrative action.”

In State of Oklahoma v. Parham, 412 P.2d 142 (1966), a

regulation enacted by the Oklahoma Alcoholic Beverage

Control Board which required wholesalers to keep minimum

inventories was upheld. The court stated: “to require

detailed and minute guidelines to the Board would be to

destroy the flexibility and effectiveness required in dealing

with the many and varying factual situations that arise

in carrying out the policy set by the legislature.” State

of Wisconsin v. Whitman, 220 N.W. 992 (1928), is another

example of a court recognizing that the specificity of stan

dards varies because sometimes the “ subject matter does

not admit of the application of any except the most general

standards.” Also, see West Central Producers Co-opera

tive Association v. Commissioner of Agriculture, 20 S.E. 2d

797 (W. Ya. 1942), and Financial Aid Corporation v.

Wallace, 23 N.E. 472 (Ind. 1939), upholding a statute

investing the Department of Financial Institutions with

authority “to classify such small loans in general order

15

according to such system of differentiation as may rea

sonably distinguish such classes of loans for purpose of

regulations.” Finally, in Dickerson, et al. v. Common

wealth, 181 Ya. 313, 24 S.E. 2d 550 (1943), the court up

held a statute giving the Alcoholic Beverage Control Board

authority to adopt regulations concerning transportation

of alcohol to “fit such transportation to legitimate pur

poses. . . .” In commenting upon the term “legitimate” the

court saw nothing indefinite about it and said that it should

be construed in its usual and common acceptance with

reference to Webster’s Dictionary.

IV.

ORDINANCE NO. 53995 IS NOT INVALID ON THE

GROUND OF INCONSISTENCY WITH STATE LAW

OR PREEMPTION OF POWERS EXERCISED BY AND

RESERVED TO THE STATE.

Appellee contends in its memorandum on motion to dis

miss that No. 53995 conflicts with Missouri’s general re

ceivership statute and consequently violates Section 71.010

R.S. Mo. 1959 which provides that “Any municipal corpora

tion in this state, whether under general or special charter,

and having authority to pass ordinances regulating sub

jects, matters and things upon which there is a general

law of the state, unless otherwise prescribed or authorized

by some special provision of its charter, shall confine and

restrict its jurisdiction and the passage of its ordinances

to and in conformity with the state law upon the same

subject.” Section 515.240 R.S. Mo. 1959 provides that

“ [t]he Court, or any judge thereof in vacation, shall have

power to appoint a receiver, whenever such appointment

shall be deemed necessary, whose duty it shall be to keep

and preserve any money or other thing deposited in court,

16

or that may be subject of a tender, and to keep and pre

serve all property and protect any business or business

interest entrusted to him pending any legal or equitable

proceeding concerning the same, subject to the order of

the court.”

The usual rule in Missouri cases involving a possible

conflict between state and city laws is summarized in

Vest v. Kansas City, 194 S.W. 2d 38 (1946): “ The fact

that a state has enacted regulations governing an occupa

tion does not of itself prohibit a municipality from enacting

additional requirements. So long as there is no conflict

between the two both will stand. * * * The fact that an;

ordinance enlarges upon the provisions of a statute by

requiring more than the statute requires creates no con

flict therewith, unless the statute limits the requirement

for all cases to its own prescriptions.” (at 39). Under this

theory courts have held city ordinances valid which require

more frequent physical examinations for barbers than state

statutes require (Vest) and which restrict the sale of

liquor even beyond the requirements of “a comprehensive

scheme for the regulation and control of [its] manufacture,

sale, possession, transportation and distribution” enacted

by the state. (City of Maryville v. Wood, 216 S.W. 2d 75

(1948), at 77.) Also see Passler v. Johnson, 304 S.W. 2d

903 (1957).

The power of a court of equity to appoint a receiver is

inherent, existing independently of statutory sanction.

(Bushman v. Bushman, 279 S.W. 122 (1925).) Section

515.240 must therefore be construed broadly to include

the full scope of the preexisting equity power and not as

limiting all cases to a narrow interpretation of its pre

scriptions. The receivership described in No. 53995—call

ing for the keeping and preserving of dwellings until the

minimum statutory requirements for such dwellings have

17

been met and a legal landlord-tenant relationship thereby

established—is clearly consistent with a broad reading of

Section 515.240 and with the general power of equity courts

to appoint receivers. Indeed, the city of St. Louis has

done no more than describe a particular use of a pre

existing and legislatively sanctioned power, a procedure

which is surely valid under Missouri’s liberal rulings in

the area of preemption.

Appellee has cited City of St. Lotas v. Stenson, 333

S.W. 2d 529 (1960), as an example of an unlawful conflict

between state and city law. This case involved an ordi

nance which set a maximum length for trucks using public

highways which was more restrictive than a state statute

to the same effect. Conflicting requirements as to the con

dition of vehicles permitted to use public highways would

have hampered intercity traffic and violated an interest in

uniformity expressed by the state legislature in Section

304.120 R.S. Mo. 1959 (which stated that city ordinances

contrary to state traffic regulations would be invalid).

No. 53995, on the other hand, is not in conflict with state law

on the subject of receivership and does not involve an area

in which uniformity is a statutory requirement or a prac

tical necessity.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

L eroy D. Clark

Gabrielle A. K irk

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Margaret M cCrory

Of Counsel

18

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that copies of the foregoing Brief

Amicus Curiae was served by depositing same in the

United States mail, air mail, postage prepaid to James J.

Wilson, Assistant City Counselor, City of St. Louis, Room

234, City Hall, St. Louis, Missouri 63103, Attorney for

Plaintiff, and J. E. Sigoloff, Charles Sigoloff and Sidney

Rubin, 722 Chestnut Street, St. Louis, Missouri, Attorneys

for Defendants.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C .«^I£s>219