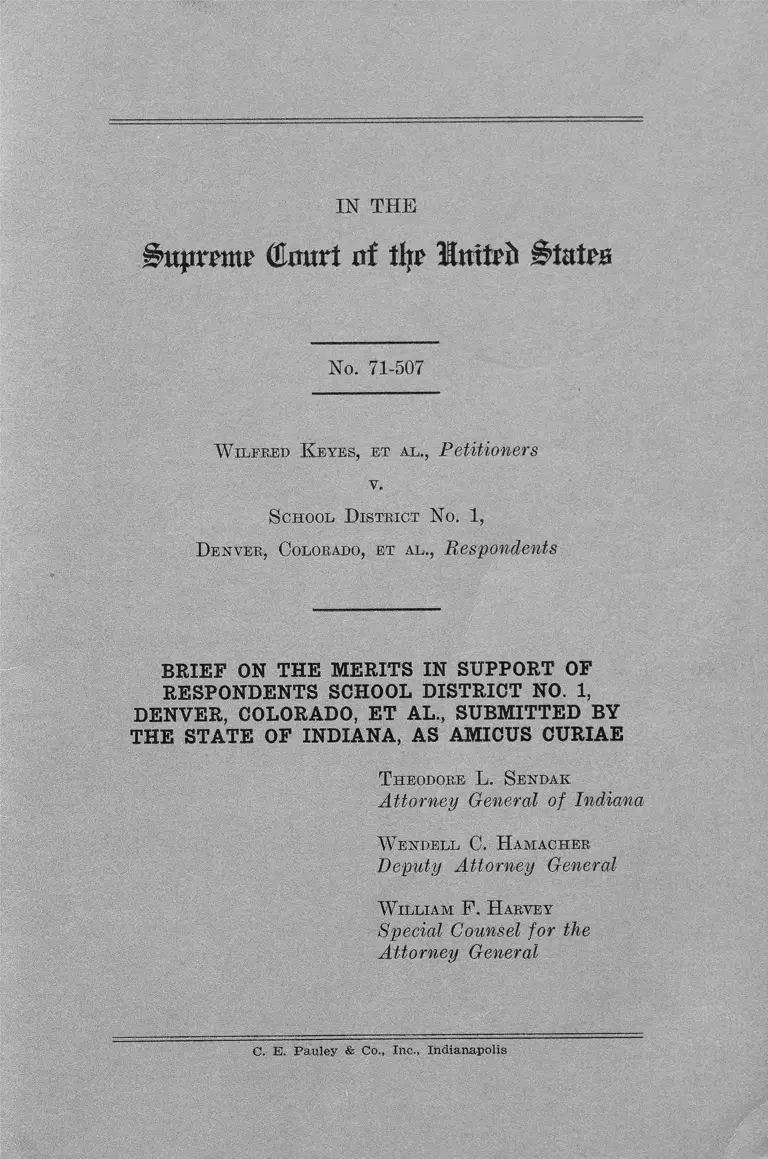

Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

June 30, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1988. 0c9a2fed-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e996fa4d-60fc-4152-a3e7-161886aafce8/keyes-v-school-district-no-1-denver-co-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

^otpronr (Cmrrt of % Unitrft j&tata

No. 71-507

W ilfred K eyes, et al., Petitioners

v.

S chool D istrict N o. 1,

Denver, Colorado, et al., Respondents

BRIEF ON THE MERITS IN SUPPORT OF

RESPONDENTS SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1,

DENVER, COLORADO, ET AL., SUBMITTED BY

THE STATE OF INDIANA, AS AMICUS CURIAE

T heodore L. S endak

Attorney General of Indiana

W endell C. H amacher

Deputy Attorney General

W illiam F . H arvey

Special Counsel for the

Attorney General

C. E . P au ley & Co., Inc., Ind ianapolis

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Interest of Amicus Curiae ............................................ 1

Opinions Below .......................................... .................... 3

Jurisdiction ...... ..................... ........ ........................... . 3

Questions Presented for Review.......... ........................ 3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved...... 5

Statement of tlie Case................................................... 5

Court-Designated Schools, or Core Area Schools 6

A Second Look at The Expert Testimony ............ 10

Summary of Argument.......................................... ....... 12

Argument

I. The Fourteenth Amendment Does Not Mandate

A Specific Intellectual Result Among* Children

In Public Schools Measured By Achievement

Tests. Compensatory Educational Programs,

Designed To Attempt To Improve Perform

ance Require Flexibility For Development.

Empirical Data Do Not Support Their Sub

ordination, Pursuant To The District Court’s

Holdings, To Racial And Economic Integra

tion. Those Holdings Are Disestablished To

Such An Extent That A Constitutional Ruling

Is Improper ................. ....................... .......... 14

A. Introduction ....... 14

B. The Court of Appeals and the Remedy in

the District Court.......... ............... 20

1. On Plaintiffs’ First Cause of Action .... 20

2. On The Plaintiffs’ Second Cause of

Action.......... ....... 20

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

Page

. . 213. On The Remedy

C. The Testimony of Dr. Coleman, Dr. Sulli

van and Dr. O’Reilly ............. .................. 23

II. This Court And The Congress Of The United

States Have Not Interpreted The Fourteenth

Amendment To Require A Specific Educa

tional Performance Among Children Attend

ing Public Schools. There Is No Data To Sup

port Such An Interpretation; It Should Not

Be Given Under The Name Of Racial Or Eco

nomic Desegregation ................................ ...... 27

A. Introduction ...... ........... ..................... ....... 27

B. The Congress Of The United States Has

Interpreted The Equal Protection Clause

As A Constitutional Right To Be Free

From Racial Discrimination In Public

Schools .............. 30

C. Griffin-Douglas; Equitable Remedies; And

Challenged Propositions Of Education .... 32

D. On Experimentation In Education And

The Fourteenth Amendment................. 36

Conclusion ......................... 37

n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Avery v. Midland County, 390 U.S. 474 (1968) ........... 28

Bell v. City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d 209 (7th Cir.),

certiorari denied, 377 U.S. 924 (1963)............. .......... 29

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) ........................ 28

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, Virginia (June

5, 1972, slip opinion, 4th Cir) ............. ............. ....... 38

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) 4,10,13,

15,19, 28, 30

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) .... - 10

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F.2d 820 (4th Cir.

1970) ... ................. ...................................................... 38

Deal v. Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir.

1966) ............................... ...... ......................-............ 29

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963) ..........—....20, 32

Downs v. Board of Education, 366 F.2d 988 (10th

Cir.), certiorari denied, 380 U.S. 914 (1964) .............. 29

Erie Railroad v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938) .......... 11

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1879) ......................... 30

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903(1956) .............. ..... ........ 29

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) .... 15

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) .................... ........20, 32

Haynes v. Washington, 373 U.S. 503 (1963) .......... ....... 10

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321 (1944) .......... ... 32

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879 (1955) ............ 29

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) — ............... - 32

James v. Valtierra, 402 U.S. 137 (1971) ...... ..............20, 32

iii

CASES Page

Johnson v. Louisana, — U.8. —, 92 S. Ct. 1635 (1972) 36

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ....... ......31, 33

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 445

F.2d 990 (10th Cir. 1971) ___________ 2,3,12,17,20,21

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 313

F.Supp. 61 (D.Colo. 1970) ...... ..2, 3, 6, 7,13,17,19, 20, 34

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 313

F.Supp. 90 (D.Colo. 1970) ........... ..............2, 3,10,11,12

Keys v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 303

F.Supp. 279 (D.Colo. 1969) .................... 5

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 303

F.Supp. 289 (D.Colo. 1969) ...... .... .............................5,17

Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905) ..................... 37

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City v. Dawson,

350 U.S. 877 (1955) .... ............ .................................. 29

Maxwell v. Bugbee, 250 U.S. 525 (1919) ...................... 28

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Assn., 347 U.S. 971

(1954) ........ 29

Offerman v. Nitkowski, 378 F.2d 22 (2nd Cir. 1967) .... 29

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948) .......... .... ...... 10

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) .......... ............. 28

Reitman v. Mulky, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) ...... .......... — 17, 20

Sealy v. Dept, of Public Instruction, 252 F.2d 898 (3rd

Cir. 1957), certiorari denied, 356 U.S. 975 (1958) .... 29

Serrano v. Priest, 96 Cal. Rptr. 601, 487 P.2d 1241

(1971) ...................................... ....... ............ .

Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175 (D.C.Cir. 1969)

Spano v. New York, 360 U.S. 315 (1959) ____

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

IV

35

32

10

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d

26 (1st Cir. 1965)____________________________ 29

State Board of Tax Comm, of Indiana v. Jackson, 283

U.S. 527 (1931) ______________________ 28

Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156 (1953)...... ................. 10

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education,

402 U.S. (1971) ------------------------------- 9,13,15,28,32

United States v. Independent School District No. 1,

Tulsa, Oklahoma, 429 F.2d 1253 (10th Cir. 1970)...... 15

Walters v. St. Louis, 347 U.S. 231 (1954) .......... .......... 28

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS,

AND STATUTES

Constitution of the United States, Amendment XIV,

§1 & §5.................................. 5

Constitution of Indiana, Article 8, Section 1 (1851) .... 1

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000c________ __ 5

42 U.S.C. 2000c-6 .................5, 30

42 U.S.C. 2000c-9............5,16,17,

30, 31

Indiana Code, 1971, Titles 20 and 21 ...... ................. . 2

OTHER AUTHORITIES

110 Congressional Record pp. 12714 & 12717 (1964) ....18, 31

Equality of Educational Opportunity (Coleman Re

port) (H.E.W., GhP.O. 1966) .....................6,11, 22, 25, 26

On Equality of Educational Opportunity, Mosteller &

Moynihan (Vintage Ed. 1972) .......... .....11, 34, 35, 36, 37

v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

CASES Page

The Effectiveness of Compensatory Education

(H.E.W., G.P.O. 1972) .......... ............................. 11, 23, 24

2 U.S. Code Cong. & Adm. News p. 2504 (1964) .......... 31

LAW REVIEWS

Kurland, Equal Educational Opportunity: The Limits

of Constitutional Jurisprudence Undefined, 35 U.

ChLL.Rev. 583 (1968) ................................................ 32

Hobson v. Hansen: Judicial Supervision of the Color

Blind School Board, 81 Harv.L.Rev. 1511 (1968)___ 32

Hobson v. Hansen: The De Facto Limits on Judicial

Power, 20 Stanford Law Rev. 1249 (1968) .......... ..... 32

Comment, Civil Rights v. Individual Liberty, 5 Indiana

Legal Forum 368 (1972) ............................................ 32

v i

IN THE

i ’uprattf (Umtrt itf % §tatPH

No. 71-507

W ilfred K eyes, et al., Petitioners

v.

S chool D istrict N o. 1,

Denver, Colorado, et al., Respondents

BRIEF ON THE MERITS IN SUPPORT OF

RESPONDENTS SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1,

DENVER, COLORADO, ET AL., SUBMITTED BY

THE STATE OF INDIANA, AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The State of Indiana, by the Attorney General of Indiana,

respectfully presents this brief amicus curiae in support of

the School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, et al., pur

suant to paragraphs 4 and 5 of Rule 42 of the Rules of the

Supreme Court of the United States.

The State of Indiana, pursuant to its Constitution, Article

8, Section 1 (1851), and statutes duly enacted, has pro

vided for a system of common schools, wherein tuition shall

be without charge, and “ equally open to all.”

An examination of the session laws of the General As

sembly of Indiana, from 1850 forward, demonstrates the

2

State’s commitment to the development of quality educa

tion in Indiana. Those laws speak to myriad items. Some of

them are: teacher training; teacher qualification and certi

fication; curriculum development and inspection; quality

of curriculum; quality and safety of buildings; libraries;

student-teacher ratios; student attendance; and student

educational development. See generally, Indiana Code,

1971, Title 20 and Title 21.

The interest of the amicus is in seeking an interpretation

of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment,

which will permit a continued development, a continued

expansion, and a continued experimentation in educational

programs in Indiana. It is a development and educational

evolution which recognizes the vast complexities in educa

tional programs in an open and pluralistic State, and also

recognizes that within that development and evolution

there shall be an equal educational opportunity for all

students enrolled in public schools.

The amicus asks the Court not to restrain that develop

ment and evolution by a constitutional interpretation which

would impose an interdicting rigidity, in the name of the

Fourteenth Amendment, in educational theory and prac

tice, as well as in established educational programs.

Accordingly, the amicus urges that the opinion and de

cision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth

Circuit, 445 F.2d 990 (1971) (App.Pet.Cert. 122a-160a), be

affirmed but only to the extent that it reversed the opinions

United States District Court, 313 F.Supp. 61 (1970) (App.

Pet.Cert. 44a-98a), 313 F.Supp. 90 (1970) (App.Pet.Cert.

99a-121a).

This brief amicus curiae is limited in its discussion and

presentation to that part of this case which is represented

by the reversal in the Tenth Circuit of the District Court.

3

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court below consists of the opinion

and judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Tenth Circuit, filed June 11, 1971, 445 F.2d 990 (App.

Pet.Cert. 122a-160a). The opinions in the District Court are

found at (App.Pet.Cert. 44a-98a) 313 P.Supp. 61; (App.

Pet.Cert. 99a-121a) 313 F.Supp. 90 (1970).

In its opinion and judgment, the Court of Appeals

ordered that the judgment of the District Court be affirmed

in all respects except that part pertaining to the “ core

area” or “ court designated schools” ; and it particularly

reversed the District Court in its legal determination that

those schools were maintained in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment because of “ unequal educational opportunity

afforded, this issue having been presented by * * * the

Second Cause of Action contained in the complaint.” (App.

Pet.Cert, 160a), 445 F.2d 990,1007.

JURISDICTION

The Supreme Court has jurisdiction to review this case

by writ of certiorari under 28 U.S.C. 1254(1), and has ac

cepted it for such purpose by granting said writ on

January 17,1972 (A. 1988a).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

The schools in Denver, Colorado, which were affected by

the District Court’s decisions (App.Pet.Cert. 44a-98a), 313

F.Supp. 61, (App.Pet.Cert. 99a-121a), 313 F.Supp, 90, were

divided into two categories, towards which the plaintiffs

directed separate claims for relief in separate causes of

action, supported by alleged separate and independent legal

theories. The second category or group of schools, called

hereafter (and in the case throughout), the “ court-desig

nated schools” or the “ core area schools” was the subject

4

of the second claim for relief, in four counts, of which the

third became primary.

The gist of the second claim for relief as developed by

the complaint, evidence, and findings, was that because of

comparatively low average achievement test scores of the

pupils tested in the “ court-designated schools”, (and be

cause of low morale and because of “ segregation” [the

word is used in quotation because the court found that there

was no state or officially imposed segregation] in those

schools) there was a denial of an equal educational oppor

tunity and of equal protection of the law. The following

questions are presented:

1. Shall Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954), and its progeny, be reinterpreted to render

unconstitutional the distinctive achievements among

students in public schools which may be shown by

standard achievement tests whenever they are ad

ministered !

2. Are there adequate data available, either in the record

of this case or information in the public domain, upon

which to develop a rule of constitutional law under the

Fourteenth Amendment, Equal Protection Clause,

concerning standard achievement scores and equal

educational opportunity?

3. When there is admittedly no dual school system pres

ent, and when the District Court finds that there is no

de jure segregation present in the specific schools

about which plaintiffs complained in a separate count,

does the District Court have judicial power to decree

compulsory integration and compensatory educa

tional programs?

4. After a District Court found that there was no de

jure segregation in the court-designated schools, but

5

then concluded that there was a denial of an equal

educational opportunity because of lower achieve

ment levels in standard achievement tests admin

istered in those schools, does the District Court have

power to decree compulsory integration, and com

pensatory educational programs which must be sub

ordinated thereunder ?

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the first and fifth sections of the

Fourteenth Amendment; and the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

§ 401, 42 U.S.C. 2000c; § 407, 42 U.S.C. 2000c-6; and § 410,

42 U.S.C. 2000c-9. These constitutional and statutory pro

visions are printed in the Appendix to this brief.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

In this case the plaintiffs filed a complaint which con

tained two (2) causes of action, each with separate and

distinct legal theories and claims for relief. (A. 2a-57a).

The complaint related to two groups of schools in

Denver, Colorado. The first group of schools, called in the

case and litigation the “ Resolution schools” (because they

were affected by Denver School Board resolutions), was

the subject of the First cause of action. Concerning those

schools, a hearing was held in July, 1969, which resulted

in a preliminary injunction. Defendant was later to pre

sent its evidence, but the District Court found that the

action of the School Board in rescinding and nullifying a

school integration plan, had “ the effect of perpetuating

school segregation * * *” (App.Pet.Cert. 19a and 37a).

303 F.Supp. 279 at 288; 303 F.Supp. 289 at 296-97, in that

the action was taken with knowledge of the consequences,

and had a tort-like wilfullness about it, 303 F.Supp. at 286.

6

Court-Designated Schools, or Core Area Schools

“ The evidentiary as well as the legal approach to the

remaining schools [referred to hereafter as the “ court

designated schools” or the “ core area schools” ] is quite

different from that which has been outlined above.” (App.

Pet.Cert. 57a), 313 F.Supp. 61 at 69 (1970).

Concerning these schools,1 the plaintiffs first complained

that there was de jure segregation (Id), because of

boundary changes and other acts on the part of the School

Board; but the District Court found that there was no de

jure segregation (App.Pet.Cert. 75a), 313 F.Supp. 61 at

77. The court also said, concerning these schools, that it “ is

to be emphasized here that the Board has not refused to

admit any student at any time because of racial or ethnic

origin. It simply requires everyone to go to his neighbor

hood school unless it is necessary to bus him to relieve

overcrowding.” (App.Pet.Cert. 67a), 313 F.Supp. 61 at

73.

In the second count of the second cause of action, the

plaintiffs asserted that the neighborhood school policy was

itself maintained for the purpose of, and with the effect of,

segregating minority pupils,2 to a degree that it was un

1 Eventually the Court said that there were 15 schools involved. The

court said, “we are here primarily concerned with the following schools:

Bryant-Webster, Columbine, Elmwood, Fairmont, Fairview, Greenlee,

Hallett, Harrington, Mitchell, Smith, Stedman and Whittier Elementary

Schools; Baker and Cole Junior High Schools; and Manual High School.”

(App.Pet.Cert. 78a), 313 F.Supp. 61 at 78.

2 The plaintiffs themselves used a racial and minority class grouping

which is of far more than casual interest. I t should be noted because

it is in contrast to the bases of much of their experts’ testimony, namely

the Coleman Report, see footnote 14 infra.

“In some schools there are concentrations of Hispanos as well as

Negroes. Plaintiffs would place them all in one category and utilize the

total number as establishing the segregated character of the school. This

is often an oversimplification * * * [which] * * * plaintiffs have ac

complished * * * by using the name ‘Anglo’ to describe the white com

munity. However, the Hispanos have a wholly different origin, and the

problems applicable to them are often different.” (App.Pet.Cert. 58a),

313 F.Supp. 61 at 69.

7

constitutional. But the district court rejected that claim

too, saying that there was no such policy apparent.

The third count of the second cause of action said, in

part, that the neighborhood school system was uncon

stitutional if it produced segregation in fact in a school

system. In short, regardless of the cause, regardless of the

absence of state or official law or policy, if the result was a

separation or segregation, it was unconstitutional. This too

the District Court rejected under the authority of previous

cases in the Tenth Circuit, which in turn was built on

cases in this Court.

The District Court then approached the heart of plain

tiffs claim in their second cause of action. It was that

the defendants were maintaining the “ court-designated

schools” in such a way as to fail to provide an equal educa

tional opportunity for students attending them.

All of those schools, plaintiffs said, produced low average

scholastic achievement. They also maintained that there

was a high teacher turnover; a higher student dropout

rate; that there were older buildings and smaller building

sites; and that there were less experienced teachers.

The District Court agreed that there was a low achieve

ment level present and significantly lower than in other

schools in the city, as shown by comparative scores on the

1968 Stanford Achievement Test results. The trial court

made findings of fact with regard to teacher experience,

teacher turnover, pupil dropout rates, and building fa

cilities, but there was no finding, as there could not have

been on the evidence presented, that there was a causal

relationship between these factors and student achievement.

(App.Pet.Cert. 78a-89a), 313 F.Supp. 61 at 78-83.

To then seek the judicial declaration of court-ordered

equalized achievement, the plaintiffs presented the testi

mony of several witnesses, chief among them, and on

8

which testimony the district court relied, were Dr. James

Coleman (A. 1516a-1561a); Dr. Neal Sullivan (A. 1562a-

1598a); Dr. Robert O’Reilly (A. 1910a-1968a), and in a

prior hearing, Dr. Dan Dodson (A. 1469a-1513a).

It is clear that some of the plaintiffs’ witnesses sought

society-wide, social reformation, which would simply use

the school system as the instrument of change:

Dr. Dan Dodson;

“ Q. Now, isn’t it also true that in your study you

found that race is not causally related to the

achievement level in these minority schools?

A. That’s right.” (A. 1508a)

# * #

After discussing the socioeconomic structure of some

areas, but not Denver, Colorado, and the effect of a par

ents’ educational background, Dodson continued:

“ Q- In other words, you think, then, that i t ’s the

schools ’ problem ?

A. I certainly do.

Q. And so your opinion is that the school has an

obligation for a social change?

A. That’s right.

Q. For the entire community ?

A. That’s right.

Q. Not for just the—not for the achievement of

academic aspect of the school?

A. That’s right.” (A. 1509a).

# #

“ Q. In other words then, you mean that the board

must cure any racial imbalance created by

housing patterns in their school system?

A. I think that’s right.” (A. 1510a).

9

Another witness, Dr. Neal Sullivan testified, in part:

“ Q. Now, also, even under your own theory that

integration in the schools has to be-—as you

say in the article, a massive educational revo

lution? Right?

A. I like that expression.

Q. Well, that’s yours, isn ’t it ?

A. You bet. I like that language.

Q. You need something more than integration?

A. You bet. Massive reform. (A. 1595a).

And the District Court itself caught the spirit of the thing:

“ The Court: I mean, psychologically, the school

is taking over for the family in many instances.

It has to. I know this is abhorrent to all of you.

You just disregard it all at (sic) paternalism. But

you can’t. I mean, that is the fact of life. The

church has fallen down somewhat. The family has

collapsed, and there is not much left. And a kid

has to relate to something, to an institution, and to

people, doesn’t he? Where is this substitute? So,

you say there is no psychological foundation for

this? [The Court was then, apparently, addressing

Dr. O’Reilly], There is no foundation in experience?

That you can just substitute this competitive at

mosphere? And this impersonal competitive atmos

phere of the integrated school and let him sink or

swim?” (A. 1934a).3

The District Court held that there was no de jure

segregation with regard to the core-city schools, and that

a neighborhood policy was not unconstitutional per se as

de facto segregation.

8 “One vehicle can carry only a limited amount of baggage. I t would

not serve the important objective of Brown I to seek to use school

desegregation cases for purposes beyond their scope, although desegre

gation of schools ultimately will have impact on other forms of dis

crimination.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education, 402

U.S. 1, 22-23 (1971).

10

But against sucli an evidentiary background, the District

Court found an alternative. It held that the “ core-city

schools in question were providing an unequal educational

opportunity to minority groups as evidenced hy low achieve

ment and morale.” (Emphasis added). (App.Pet.Cert.

100a), 313 F.Supp. 90, 91.

From that position the District Court then moved to a

consideration of a remedial plan or plans, consistent with

the Brown 7,4 5 Brown IP dichotomy.

During that proceeding, in May 1970, the District Court

said on opinion, and largely in response to the proposals

which the defendants raised, that the,

“ crucial factual issue considered was whether

compensatory education alone in a segregated set

ting is capable of bringing about the necessary

equalizing effects * * *” (App.Pet.Cert. 106a), 313

F.Supp. 90 at 94.

In an effort to answer that question the District Court

then turned principally to the testimony of Dr. James

Coleman (A. 1516a-1561a); Dr. Neal Sullivan (A. 1562a-

1599a) ; and Dr. Robert O ’Reilly (A. 1910a-1968a); 313

F.Supp. 90 at 94.

A Second Look at The Expert Testimony

The petitioners ask on brief that the Court itself conduct

an independent examination of the record.6 If so, then

4 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

5 Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955).

6 Petitioners’ Brief page 79. The authority cited for this request is

Haynes v. Washington, 373 U.S. 503, 515-517 (1963) ; Spano v. New

York, 360 U.S. 315, 316 (1959); Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156, 181

(1953); and Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633, 636 (1948). But the

petitioners seek here a new constitutional rule: that equal educational

opportunity shall mean equal achievement results, however measured.

They deny this result, of course, see footnote 123, page 103 of Peti

tioners’ Brief. But the district court said: “The final portion of the

11

under the evidentiary standards freely used in this case,7

this Court can consider the relevant surveys, data, and

findings (the “ Coleman Report” 737 pages, for example,

is marked as PX 500) which were used and to which ref

erence was made, as well as other data and information

which this Court can acknowledge and consider. Erie

Railroad v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938).8

The testimony given by these witnesses, when measured

against the data admitted, and subsequent interpretation

and analyses thereof, simply does not support the con

clusions reached or the holding which the petitioners seek

from this Court, as a principle of Constitutional law.

In short, having concluded, primarily on the basis of the

1968 Stanford Achievement Scores, that there was an un

equal educational opportunity, these experts were called

to discuss a remedy.

That testimony and the impact of other data upon it is

discussed in the Argument section of this brief, under

Argument I-C, “The Testimony of Dr. Coleman, Dr. Sul

livan, and Dr. O’Reilly.”

In summary, the results against which the District

Court directed a remedy in regard to the “ court desig

nated” schools were not the product of, or caused by state

action, or official, or school board action, or positive law.

To the extent that these results were established (and the

expert witnesses often testified that they were not referring

to Denver in their testimony), they occurred adventitiously.

plaintiffs’ plan suggest a system of compensatory education programs,

carried out in an integrated environment, designated to equalize achieve

ment.” (App.Pet.Cert. 102a), 313 F.Supp. 90, 91-92. (Emphasis added).

7 Coleman—A. 1526a; Sullivan—A. 1568a., 1583a-1586a; O’Reilly—A.

1915-1928a.

8 “Equality of Educational Opportunity” (H.E.W., G.P.O. 1966)

PX 500 (herein “Coleman Report” ) ; “On Equality of Educational Op

portunity,” Mosteller & Moynihan (Vintage Ed. 1972) (herein “Mosteller

& Moynihan”) : “The Effectiveness of Compensatory Education” (H.E.W.,

Gr.P.O. 1972) (herein, “Effectiveness”) .

12

The District Court thus entered findings and guidelines,

which, generally, provided for a program of “ desegrega

tion” [which word, again, is used in quotation simply to

recall to the reader that there was no state or officially

imposed segregation] and compensatory education as a

solution to low average achievement in the “ court-desig

nated schools.” (App.Pet.Cert. 112a-121a), 313 F.Supp.

90 at 97-100. The preliminary injunction arising from the

first cause of action remained in effect, except as altered

by the orders entered.

This determination was reversed in the United States

Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, which said that

the final decree and judgment of the District Court was

affirmed, “ except that part pertaining to the core area or

court designated schools, and particularly the legal de

termination by the court that such schools were maintained

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment because of

unequal educational opportunity afforded, * * * *” (App.

Pet.Cert. 151a), 445 F.2d 990 at 1007 (1971). Other orders

are well described by the Denver School Board, on brief.

On January 17,1972, this Court granted a writ of certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit.

The brief amicus curiae is limited in its discussion to

that part of this case which is represented by the reversal

in the Court of Appeals.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I

In so far as the “ court-designated” schools are con

cerned, the measure of this case as it reaches the Supreme

Court is found in what this Court is asked to affirm from

the District Court and the consequences it would have on

educational development throughout the United States.

This Court is being asked to affirm the assertion, as a

13

matter of Constitutional law, that compensatory educa

tional programs, as a means to develop and improve a

child’s educational performance and achievement, are un

constitutional unless they are developed in the setting of

subordination to racial and economic integration, as effected

by the remedies which were developed in, and are borrowed

from, the cases decided from Brown I to Swann.

But the empirical data which have become available since

this case was in the District Court show that the bases for

that court’s holdings with regard to both the wrong and

the remedy are disestablished to such an extent that no

constitutional interpretation should be indulged in.

II

The Fourteenth Amendment, as interpreted by this

Court, and as addressed and interpreted by the Congress

of the United States, does not mandate a specific educa

tional performance among children attending a public

school.

The Fourteenth Amendment should not be interpreted

so to mean that equal rights under the law, when one is

confronted by the State, shall mean equality in achievement

when one attends a public school.

Racial segregation was never an educational program;

it was a social-racial policy imposed in an educational

system by the State.

In the name of racial (or economic) desegregation, the

Fourteenth Amendment should not be interpreted to re

quire an educational program which would attempt to

develop but one result: equal achievement among students,

as evidenced by achievement test scores.

14

ARGUMENT

I

The Fourteenth Amendment Does Not Mandate A Specific

Intellectual Result Among Children In Public Schools,

Measured By Achievement Tests. Compensatory Educa

tional Programs, Designed To Attempt To Improve Per

formance Require Flexibility For Development. Empir

ical Data Do Not Support Their Subordination Pursuant

To The District Court’s Holdings, To Racial And Eco

nomic Integration. Those Holdings Are Disestablished

To Such An Extent That A Constitutional Ruling Is

Improper.

A. Introduction

In the District Court, this was a great case. Walter

Lippmann remarked many years ago, in America there is a

distinct prejudice in favor of those who make accusations.

Never was such an observation more appropriate than in

this judicial proceeding.

It was a great case because a great school board, in

Denver, Colorado, was well defended. It was a school

system which had known a tremendous population growth

subsequent to World War II, and it dealt with the re

markably complex educational problems which evolved

from it, very well indeed. It was a school system which in

fact spent over 100 million dollars on new buildings and

installations since World War II. Its effort to manage the

urban sprawd’s impact on education was well underway

long before the Congress and Executive branches of the

Federal Government created the Department of Housing

and Urban Development, or the Department of Transpor

tation, or the Environmental Protection Agency, which is

some testimony to their recognition of the urban problems

confronted by the Denver School Board. But it came long

after that School Board was already making the effort.

15

It was a School Board which never resulted, as the State

of Colorado did not, to the use of a dual school system.

There was in fact, for the School Board in Denver, simply

no factual analogy to the bases of the cases and schools

found in Brown I,9 or Green,10 or Swann11. Nor, for that

matter, was the case factually similar to the Tulsa12 case

in the 10th Circuit.

Those were cases which arose in a dual school system,

or they were cases in which the School Board failed to

deal with the ‘ ‘ vestiges of dualism ’ ’.

But as the growth of Denver was great, so also was its

growth of minority groups. In 1940 the Negro population

was 8,000 persons. In 1966, it was estimated by plaintiffs’

witness Bardwell to be at 45,000. Faced with this growth,

still no dual school system ever developed, or existed in

Denver. No person was ever excluded from any school

because of race, color, or ethnic origin.

At the beginning of the school year 1968-69, there were

116 schools: 92 elementary, 15 junior high schools and 9

senior high schools. In the elementary schools, Negro

students were enrolled in 78, “ Hispano” in 88, “ Anglo”

in 92. Among the 15 junior high schools, there were Negro

students in 14 of the 15, and Hispano in all 15. Anglo were

in all 15. Among the high schools, Anglo and Hispano

students were enrolled in all 9 schools; and Negro students

in 8 of the 9 high schools.

In short, the defendant Board did not refuse to admit

any student at any time because of racial or ethnic origin.

9 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

10 Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

11 Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971).

12 United States v. Independent School District No. 1, Tulsa, Okla

homa, 429 F.2d 1253, 1259 (10th Cir. 1970).

16

It simply required a student, consistent with the Civil

Eights Act of 1964, § 410, 42 TT.S.C. 2000c-9, to attend his

neighborhood school. (App.Pet.Cert. 67a), 313 F.Supp.

61 at 73.

But if, as Lippmann said, there is prejudice in favor of

one who makes an accusation, then the prize will go to he

who makes the greatest accusation.

For the accused, however, the Denver School Board, the

dilemma was enormous. The attack took a bifurcated ap

proach. First, there was the accusation relating to the

usual kind of segregation charge: the location of school

buildings; boundary changes; the formal actions of a

school board, and the like. That attack, as the case left

the District Court, was largely a failure.

Secondly, in the plaintiffs’ second cause of action, there

was an attack for the “ failure” of the School Board to

cause students to achieve at the same level according to

the Stanford Achievement Tests. The District Court found,

“ and concluded that the achievement level in these schools

is markedly lower and dropout rates are high; and that

there has been a concentration of minority and inexperi

enced teachers.” (App.Pet.Cert. 90a), 313 F.Supp. 61 at

84. This presented an opportunity, as the case concluded

in the District Court, for petitioners to strike hard at an

entire school system (as they now do in this Court, on

brief, page 68-92, and their factual assertions, page 1-64,

passim) and more. It was an opportunity to attempt to

bury any further experimentation and development with

compensatory education, a favorite bete noire, unless it is

compelled to march in constitutional lockstep with the

massive movement of children, and massive social reform,

as plaintiffs ’ own witnesses described it, under the banner

of Oreen-Swann.

17

Concerning the first leg of attack, the District Court

gave primary attention to the rescinding of School Board

Resolutions, 1520, 1524, and 1531, and the court concluded

that such an act violated the case law of Reitman v. Mulky,

387 U.S. 369 (1967); 313 F.Supp. at 67-69. The Court of

Appeals did not reach the point, 445 F.2d 990 at 1002, and

the petitioners appear to have abandoned the idea in this

Court, entirely. Then the District Court considered the

charges of boundary changes 313 F.Supp. 61 at 69, but came

to the finding that there was no de jure segregation, 313

F.Supp. 61 at 77.

Dp to this point the primary finding concerned the con

struction of Barrett Elementary School, along with an

incorporation of the preliminary injunction statements,

303 F.Supp. 289, 290-95, which when made did not then

consider defendants’ evidence. Concerning Barrett Ele

mentary School, the trial court said that alternative sites

were available; and both the trial court and the petitioners

on brief made much of the testimony of Superintendent

Oberholtzer, (313 F.Supp. at 73; Petitioners’ Brief, e.g.,

pp. 18 and 20), because he was “ of the opinion that it was

not permissible for him to classify Negroes as such, even

for the purpose of bringing about integration.” (App.

Pet.Cert. 66a), 313 F.Supp. 61 at 73.

The Superintendent, in supporting the neighborhood

school policy of the Denver Schools, and in assuring that

the conduct of the Denver School Board was “ color blind”,

anticipated, insofar as their schools were concerned, the

fact that their policy was to become the policy of the United

States, and so it remains to this day, in the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, § 410, 42 U.S.C. 2000c-9. That section provides:

“ Nothing in this subchapter shall prohibit classi

fication and assignment for reasons other than race,

color, religion or national origin.”

18

Speaking to that section, Senator Humphrey said:

“ Furthermore, a new section 410 would explicitly

declare [it is then set out in full].

Thus, classification along bona fide neighborhood

school lines, or for any other legitimate reason

which local school boards might see fit to adopt,

would not be affected by title IY, so long as such

classification was bona fide.” 110 Cong. Rec. 12714

(June 4,1964).

Again, Senator Humphrey spoke to one of the very

central factual questions in this case, and one which, it

appears, the petitioners’ would attempt to obscure on brief

in their presentation of a factual quagmire: that issue is

the legitimacy of a neighborhood school which was not

designed to cause or perpetuate racial discrimination or

unlawful segregation, or, for that matter, a school district

organized in the same way:

Senator Humphrey:

“ * * * The bill does not attempt to integrate the

schools, but it does attempt to eliminate segregation

in the school systems. [The Senator was speaking of

racial segregation]. The natural factors such as

density of population, and the distance that students

would have to travel are considered legitimate

means to determine the validity of a school district,

if the school districts are not gerrymandered, and in

effect deliberately segregated. The fact that there

is racial imbalance per se is not something which is

unconstitutional.” 110 Cong. Rec. 12717 (June 4,

1964).

In short, § 410 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was

specifically added to permit student classification into

school districts, or neighborhood schools, on bases other

than race, religion, color, or national origin.

It did hardly behoove the District Court, to remark the

“ failure on the part of the Board” to take some action

19

which would have an integrating effect, when to do so

would violate the spirit and broad command of the Congress

of the United States, in structuring a neighborhood school

system; which the District Court itself found not to be in

violation of Broivn I.

Generally, the Court of Appeals affirmed those very

limited findings, and felt restrained by Rule 52 in its review

—although, now, of course, petitioners ask this Court to

review the entire record.

Secondly, an attack came to the Board of a very different

nature. It was that, as the District Court finally evolved the

issue, there was no equal educational opportunity present

with respect to the “ court-designated” schools, even if

there was no de jure discrimination. The District Court held

that there was not. Then the District Court looked at es

sentially one item: the student achievement level as de

termined by the 1968 Stanford Achievement Tests. Other

tilings found their way into this part of the decision:

teacher turnover; pupil dropout rates (one premise for

this consideration is conventional wisdom: “ its better

that he be in school than on the streets,” , or, “ if you are in

school, then stay in school” ) ; building facilities (“ the fact

that the physical plant is old may aggravate the aura of

inferiority which surrounds the school”, the court said,

313 F.Supp. 61 at 81), teacher experience, and the testi

mony of Dr. Dodson. The court did not find that these

conditions caused inferior achievement, and the experts at

the remedy stage did not so testify either.

The District Court did not find here a Brown I type of

violation. Rather it turned to other cases and said: in an

effort to safeguard the poor or minorities “ state action,

even if non-discriminatory on its face” which results in

unequal treatment of “ the poor or a minority group as

a class” [presumably the District Court was referring to

20

racial minorities, although the word, coming after the word

“ poor” could have meant an economic minority] is un

constitutional unless the state provides substantial justi

fication, citing Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956), and

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963). 313 F.Supp.

61 at 82. Contra, James v. Valtierra, 402 U.S. 137 (1971).

B. The Court of Appeals and the Remedy in the District

Court

As the case left the district court on the “ violation”

side, these things had occurred:

1. On Plaintiff’s First Cause of Action:

a) The district court found a Reitman violation;

which was phased out of the case in the Court

of Appeal.

b) With regard to the Resolution Schools, and

especially Barrett Elementary, the District

Court found a kind of Brown I-Reitman vio

lation, which received a Rule 52 affirmance in

the Court of Appeals.

c) With respect to all other claims, all other

schools, there was a finding that no Brown I

violation was present.

2. On The Plaintiff’s Second Cause Of Action:

a) The district court found no Brown I violation.

b) The district court found a Griffin v. Cali

fornia, violation.

On appeal, the Court of Appeals seemed at first to agree

with the District Court in its assertion on equal achieve

ment :

“ The trial court’s opinion * * * leaves little doubt

that the finding of unequal educational opportunity

in the designated schools pivots on the conclusion

that segregated schools, whatever the cause, per se

produce lower achievement and an inferior educa

tional opportunity.” 445 F.2d 990, at 1004.

21

But then the Court of Appeals spoke one of the most

important sentences in its entire proceeding;

“ Thus it is not the proffered objective indicia of

inferiority which causes the sub-standard academic

performance of these children, but a curriculum

which is allegedly not tailored to their educational

and social needs. ’ ’ Id. at 1004.

In short, the Court of Appeals did not accept the bases

of the trial court’s holdings, namely the items to which the

trial court referred as showing a Griffin type of violation13

(and allegedly justifying the remedy which plaintiffs sought

and the trial court imposed) plus inferior achievement, in

the sense that they provided a basis for a Constitutional

Mandate

Implicit in the Court of Appeals holding is the fact that

we really do not know what causes inferior achievement

nor, especially, how to remedy it, sufficiently to form a

rule of Constitutional law, binding on 200 million persons

and all of their school districts and programs.

Even acknowledging the experts presented at the rem

edies hearing by the plaintiffs, educational achievement

development is at the early ether stage of anesthetics. The

most we can do is try, experiment, develop, test, determine,

and try again. That is precisely what the Denver School

Board recognized (as did the Court of Appeals) in its

Resolution 1562, found at 445 F.2d 1009-10.

3. On The Remedy.

The opportunity which was presented to plaintiffs cer

tainly was not lost. It was an opportunity to judicially

subordinate compensatory educational programs to racial

integration remedies, and more. It was an opportunity to

13 Again, those things were in addition to achievement scores, teaching

experience, building facilities, pupil dropout rates, and teacher turnover,

and the testimony of Dr. Dodson. 313 F.Supp. 61 at 78-82.

22

bury, once and for all, one of the most important obser

vations made in tbe Coleman Report:

“ The overall results of this examination of school-

to-school variations in achievement can be summed

up in three statements :

1. For each group,14 by far the largest part of

the variation in student achievement lies with

in the same school, and not between schools.

2. Comparison of school-to-school variations in

achievement at the beginning of grade 1 with

later years indicates that only a small part

of it is the result of school factors, in contrast

to family background differences between

communities.

3. There is indirect evidence that school factors

are more important in affecting the achieve

ment of minority group students; among

Negroes, this appears especially so in the

South. This leads to the notion of differential

sensitivity to school variations, with the low

est achieving minority groups showing high

est sensitivity.”

“Coleman Report” (1966) at page 297.

(Emphasis added).

The plaintiffs did not pass the chance. They proposed a

simple pairing plan, wherein the great distinctions in

student achievement within each school in the Denver

schools would be lost forever. That is, they would exist,

but not be recognizable. The plan would take an average

achievement among the students in a school, and pair the

school with the average achievement among students in

another school. (Pl.Ex.501-A).

To this the District Court gave its constitutional impri

matur.

14 The Report was referring to : Puerto Rican; Indian American;

Mexican-American; Negro, South; Negro, North; Oriental American;

White, South; White, North.

23

C. The Testimony of Dr. Coleman, Dr. Sullivan and Dr.

O’Reilly

The plaintiffs called Dr. Coleman, Dr. Sullivan, and

Dr. O’Reilly to speak about remedies, and there was one

consistency among their remarks: they were not speaking

about Denver, Colorado, and had no previous experience

with the schools there.

The petitioners have summarized Dr. Coleman’s testi

mony in this way: the studies of compensatory programs

“ have not been very encouraging with regard to their

efforts.” (A. 1537a) (Petitioners’ Brief page 58), and

that “ I think” the major problem, with compensatory edu

cational programs has been the fact that the child’s en

vironment has not changed if he speaks with other children

who are homogeneous with his past. Id.

The H.E.W. Report on “Effectiveness of Compensatory

Education” of 1972 states :

‘ ‘ In this connection, it is worth noting two additional

features of the Coleman report:

• As the author has recently pointed out, the

Coleman report should not be used to claim

that physical desegregation is the only edu

cational treatment that can have any positive

achievement effects.

• There is no direct evidence in the Coleman

report for the conclusion, sometimes drawn

from it, that compensatory education does

not work. The Coleman report analyzed the

existing range of school conditions in 1965-

1966 and had nothing to say about situations

in which very substantial additional resources

above normal school expenditures were pro

vided for basic learning programs. The Cole

man report did not analyse any such intensive-

programs. (Emphasis added). “ The Effec

24

tiveness of Com pensatory Education,”

(H.E.W., Gf.P.O. 1972), page 10.

The petitioners also summarized the testimony of Dr.

Sullivan. That is understandable. Dr. Sullivan appeared

as the Secretary of the State Board of Education in the

State of Massachusetts. As such, he spoke on several

things: compensatory programs in Boston, Massachu

setts, and Berkeley, California; inferiority complexes

(A. 1579a); psychology (A. 1579a); sociology (Id.); and

the moral duties of educators. (Id.) But the principal pur

pose of his testimony was to establish that a compensatory

education program with which he was associated in Berke

ley, California, was a failure, that it “ had no effect.”

(A. 1578a).

He explained that Berkeley tried everything: “ lower

class size; “ materials and equipment” ; “ [h]undreds of

thousands of dollars for electronic equipment that most

schools have now” ; the “ addition of paraprofessionals” ;

“ lots and lots of black administrators” ; “ Black principals

in white schools. We felt that was only fair. White princi

pals in black schools. We felt that was good. You name it

and we tried it.” (A. 1577a). Still, he said, it was a failure.

The H.E.W. Report on “Effectiveness of Compensatory

Education” (1972), said this:

“ The important difference between success and non

success appears to depend on whether compensatory

education funds have been channeled into traditional

patterns of expenditure—salary increases, routine

techniques, etc.—or whether they have been used to

develop supplementary, focused, compensatory edu

cation programs. The reason there is so much evi

dence of failure is that resources have more often

been used in the former rather than the latter man

ner.” (Emphasis added). “Effectiveness”, Id at

11.

25

The Report spoke about the situation in California in

this way:

“ The most complete data are those available from

the State of California. * # * Achievement data was

(sic) collected for about 80% of all participants in

compensatory reading programs and analyses were

conducted using data covering about 50% of the

participating children. Only that achievement data

which met specified quality control criteria was (sic)

included. Over the four years covered by the data,

54% to 67% of children receiving compensatory

services showed a rate of reading achievement gain

larger than the usual maximum for disadvantaged

children. Analysis and results for mathematics were

similar and even slightly better. We judge this to he

clear evidence of success. (Emphasis added). “Ef

fectiveness”, Id at 7.

Dr. Sullivan testified that integration in Berkeley eased

such problems as teacher turnover and low teacher ex

perience ; and Dr. 0 ’Reilly questioned the value of compen

satory programs in either an integrated or non-integrated

setting. (A. 1929a-20a). It is small wonder that with this

evidence, the District Court came to its conclusions.

But one of the most important observations in the Cole

man Report, went, it seems, almost unnoticed. It is stated

as follows:

“ This analysis has concentrated on the educational

opportunities offered by the schools in terms of

their student body composition, facilities, curricu-

lums, and teachers. This emphasis, while entirely

appropriate as a response to the legislation calling

for the survey, [§402 of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000c-l] nevertheless neglects im

portant factors in the variability between individual

pupils within the same school; this variability is

roughly four times as large as the variability be

tween schools. For example, a pupil attitude factor,

26

wMch appears to have a stronger relationship to

achievement than do all the ‘school’ factors together,

is the extent to which an individual feels that he has

some control over his own destiny.” “Coleman Re

port” (1966) at page 22-23. (Emphasis added).

Dr. Sullivan spoke about the feelings of inferiority of

the Negro student. He said, “ it was very clear to me that

in their isolation they [Negroes] were completely rejected

and psychologically this came through.” (A. 1579a).

Again, the Coleman Report disturbs a number of as

sumptions and eye-witness certainties, such as that:

“ When asked about whether they wanted to be

good students, a higher proportion of Negroes than

any other group—over half—reported that they

wanted to be one of the best in the class (table

3.13.2).” “Coleman Report” (1966) at 278.

And in speaking about general attitudes toward them

selves and their environment, held by students, the follow

ing is found:

“ Apart from the generally high levels for all groups,

the most striking differences are the especially high

level of motivation, interest, and aspirations report

ed by Negro students. * * * [And speaking about

the child’s concept of himself] In general, the

responses to these questions do not indicate dif

ferences between Negroes and whites, but do indicate

differences between them and the other minority

groups.” “Coleman Report” (1966) at pages 280

and 281.

But with the testimony before it, the District Court was

moved from the comparative to the superlative sense of

approach:

“ We have concluded after hearing the evidence that

only feasible and constitutionally acceptable pro

gram—the only program which furnishes anything

27

approaching substantial equality—is a system of

desegregation and integration which provides com

pensatory education in an integrated environment. ’ ’

(Emphasis added). (App.Pet.Cert. 112a), 313 F.

Supp. 90 at 96.

And the court continued with the same penultimate

language in its findings: “ Thus, the only hope for raising

the level of these students * * * “ The ideal approach,

and that which offers maximum promise * * * * ’’ (Emphasis

added), Id. at 96.

Such comments if spoken by an educator would be re

garded as graduation-day puffing. But the court spoke as a

matter of constitutional law and it subordinated compen

satory education programs, educational experimentation

and research, all, to a kind of warmed-over Swa,nn remedy,

as a solution to low average achievement in the court-des

ignated schools.

The essence of what the petitioners ask in this part of

the case is that this Court do the same thing.

II

This Court And The Congress Of The United States Have

Not Interpreted The Fourteenth Amendment To Require

A Specific Educational Performance Among Children

Attending Public Schools. There Is No Data To Support

Such An Interpretation; It Should Not Be Given Under

The Name Of Racial Or Economic Desegregation.

A. Introduction

The Fourteenth Amendment was certified as a part of

the Constitution on July 28, 1868, and its Equal Protection

Clause forbids a state to “ deny to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Thus, the Equal Protection Clause requires a state to

treat in like manner all persons similarly situated. State

Board of Tax Commissioners of Indiana v. Jackson, 283

U.S. 527 (1931); Maxwell v. Bughee, 250 U.S. 525 (1919).

It is a clause which does not, in law or fact, require identi

ty of treatment. Walters v. St. Louis, 347 U.S. 231 (1954).

And it permits a state to make distinctions between per

sons subject to its jurisdiction if the distinctions are based

on some reasonable classification, and all persons embraced

within the classification are treated alike. It outlaws in

vidious discrimination. Avery v. Midland County, 390 U.S.

474 (1968).

From 1868 to 1954, the Equal Protection Clause was

interpreted to permit a state to impose, as a matter of

state law, racial segregation in its public schools, when

it furnished equal facilities for the education of the children

of each race or races. Compare Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

U.S. 537 (1896), with Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483 (1954), and Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954).

“ Nearly 17 years ago this Court held, in explicit terms,

that state-imposed segregation by race in public schools

denies equal protection of the laws. At no time has the

Court deviated in the slightest degree from that holding

or its constitutional underpinnings.” Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenberg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 11 (1971).

“ This case [Swann] and those argued with it arose in

States having a long history of maintaining two sets of

schools in a single school system deliberately operated to

carry out a governmental policy to separate pupils in

schools solely on the basis of race. That was what Brown v.

Board of Education was all about.” Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenberg Board of Education, supra at 5.

In short, this Court struck down a governmental policy of

racial segregation, which was effected in the public school

system. The Court did not then, and not since that time

has it used the Fourteenth Amendment to develop edu-

29

eational policy. Brown was not a case on educational pro

grams and policies, and racial segregation was not a part

thereof either.

Brown, and its progeny, was a case which struck at a

government developed racial-social policy of segregation

and discrimination in the public schools; such govern

mental policies meant inherent inequality by governmental

order, which was developed and effectuated, in part, by

use of the public school system. Thus this Court said, “ The

target of the cases from Brown I go the present was the

dual school system.” Id. at 22.

But the use of the public school system to develop and

promote a governmental policy of racial segregation was

only a part of the systematic program. It occurred and was

struck down in public parks, Muir v. Louisville Park

Theatrical Assn., 347 U.S. 971 (1954), in and on public

beaches and bathhouses, Mayor and City Council of Balti

more City v. Dawson, 350 U.S. 877 (1955), municipal golf

courses, Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879 (1955),

and on municipal buses, Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903

(1956), all on the authority and the concept of the Brown

decision.

Under these authorities, the cases which hold that for a

Brown violation there must be a state act in creating racial

segregation or separation, rather than adventitious de

velopment, are simply legion. Among them are: Spring-

field School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d 261, 264,

(1st Cir. 1965); Offerman v. Nitkowski, 378 F.2d 22 (2nd

Cir. 1967); Sealy v. Dept, of Public Instruction, 252 F.2d

898 (3rd Cir. 1957), certiorari denied, 356 U.S. 975 (1958);

Deal v. Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1965);

Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d 209 (7th

Cir. 1963), certiorari denied, 377 U.S. 924; Downs v. Board

of Education, 366 F.2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964), certiorari

denied, 380 U.S. 914.

30

B. The Congress Of The United States Has Interpreted

The Equal Protection Clause As A Constitutional

Right To Be Free From Racial Discrimination In

Public Schools

Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides:

“ Section 5. The Congress shall have power to en

force, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of

this article.”

Acting under the Fourteenth Amendment, and in re

sponse to this Court’s decision in Brown 1, and subsequent

decisions, the Congress enacted subchapter IV, of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964. In it, it gave an interpretation to

desegregation (and thus segregation) 42 U.S.C. 2000c; it

defined the power of the Attorney General to initiate a law

suit to seek the desegregation of a school system, when a

person is unable to initiate such an action, 42 U.S.C.

2000c-6; and it spoke specifically to the classification legiti

macy, on bases other than race, color, religion or national

origin, 42 U.S.C. 2000c-9. These interpretations were bind

ing on the Denver School Board, and they were followed

by the School Board. There was no finding of racial dis

crimination in the court-designated schools.

Congress is authorized to enforce the prohibitions by

appropriate legislation under § 5 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 345 (1879), and it

could do so without regard to whether this Court or any

court would hold the act prohibited to be in violation of the

Equal Protection Clause. In seeking to promote the objects

of the Equal Protection Clause the Congress prohibited

racial discrimination in the public schools, it defined de

segregation, and it specifically allowed classification of

students on bases other than race, color, religion or na

tional origin.

31

It was said:

“ In implementing the decision of the Supreme

Court, we urge the Congress to be guided by two

fundamental premises: (1) The American system of

public education—an essential bulwark of a demo

cratic system of government—should be preserved

unimpaired; (2) the constitutional right to be free

from racial discrimination in public education must

be realized (Emphasis added). 2 U.8. Code Cong.

& Adnt. News p. 2504 (1964).

Section 410, 42 IT.S.C. 2000c-9 provides:

“ Nothing in this subchapter shall prohibit classi

fication and assignment for reasons other than race,

color, religion, or national origin.”

In speaking about this provision Senator Humphrey said:

“ Thus, classification along bona fide neighborhood

school lines, or for any other legitimate reason

which local school boards might see fit to adopt,

would not be affected by title IY, so long as such

classification was bona fide.” 110 Cong. Rec. 12714

(June 4,1964).

Again, Senator Humphrey said:

“ * * # The bill does not attempt to integrate the

schools, but it does attempt to eliminate segrega

tion in the school system. The natural factors such

as density of population, and the distance that

students would have to travel are considered legiti

mate means to determine the validity of a school

district, if the school districts are not gerrymand

ered, and in effect deliberately segregated. The fact

that there is racial imbalance per se is not unconsti

tutional. * * *” 110 Cong. Rec. 12717 (June 4, 1964).

The interpretation given to the Equal Protection Clause

by the Congress in subchapter IV of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 is binding here. Katsenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S.

641 (1966).

32

0. Griffin-Douglas; Equitable Remedies; And Challenged

Propositions Of Education.

The petitioners support the trial court’s assertion that

nondiscrimination, if it results in unequal treatment of the

poor or a minority group, is unconstitutional unless the

state shows a substantial interest therein, citing Griffin v.

Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956), and Douglas v. California, 372

U.S. 353 (1963); compare Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385

(1969). Contra, James v. Valtierra, 402 U.S. 137 (1971).

From this position, the petitioners as well as the district

court would sweep on to the full use of a court’s equitable

power under Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321, 329-330

(1944), and Stvann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Edu

cation, 402 U.S. 1, 15, (1971).1151 The result, as in this case, 15

15 But other courts, and authorities, have recognized that there is

much more in the use of equitable judicial power than simply the

recognition of its existence, which the petitioners show in their Brief

on the Merits.

For example, the precise point was made by Chief Justice Burger,

then Circuit Judge, in dissenting in the case of Smuck v. Hobson, 408

F.2d 175 (D.C. Cir. 1969), at page 196, where he said:

“Several commentators have expressed views which undergird

what Judge DANAHER has said as to the need for caution

and restraint by judges when they are asked to enter areas so

far beyond judicial competence as the subject of how to run a

public school system. We have little difficulty taking judicial

notice of the reality that most if not all of the problems dealt

with in the District Court findings and opinion are, and have

long been, much debated among school administrators and edu

cators. There is little agreement on these matters, and events

often lead experts to conclude that views once held have lost

their validity.” (Emphasis added).

And the dissent cited impressive authority where the point is further

discussed. Among them are: Kurland, Equal Educational Opportunity:

The Limits of Constitutional Jurisprudence Undefined, 35 U.Chi.L.Rev.

583, 592, 594, 595 (1968); Hobson v. Hansen, The DeFacto Limits on

Judicial Power, 20 Stan.L.Rev. 1249, 1267 (1968); Hobson v. Hansen:

Judicial Supervision of the Color-Blind School Board, 81 Harv.LRev

1511, 1527, 1525 (1968).

The point that policy commitments are present in asserting equitable

power and decrees was made by Professor Alexander Bickel: “Willy-

nilly, the Supreme Court imposes a choice of educational policy, for the

time being at least * * * and I don’t think we can be sure that the

3 3

is to subordinate, if not bury, innovative compensatory edu

cational programs, unless they march in lockstep to the

Brown 1—Swann remedies.

The substantial interest of the State of Indiana is in

preventing the constitutionalization of education proposi

tions, which, in the context of constitutional law, may be

called “ myths” .

A short time ago, Mr. Justice Harlan reminded us that

“ [djecisions on questions of equal protection and due

process are based not on abstract logic, but on empirical

foundations.” Katsenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 668

(1966) (Emphasis added).

With that thought in mind, the amicus presents to the

Court several “ Propositions of Education” which are im

plicit in this case, and in the District Court’s action:

“Proposition of Education, No. 1”:

The amount of money spent determines the goods

and services bought, which in turn determines the

effectiveness of the school in developing and meet

ing the needs of a child.

This proposition appeared in rough form when it was

asserted by Charles Sumner in 1849 before the Massa

chusetts Supreme Court. He argued that racially segregated

schools in Boston, Massachusetts, provided unequal oppor

tunities for Negroes and whites. The ground for the

argument was that his “ client, a Negro girl, had to walk

2100 feet to her school while a white school was only 800

feet away from her home. He lost the case, but the same

choice is the right one * * * Professor Bickel cannot be read to oppose

school integration; but rather, he opposes Swann because it willy-nilly

decided that the nation’s legal order compels the racial mixing of stu

dents [where there was a dual school system] as a matter of educational

policy.” Comment, Civil Bights v. Individual Liberty, 5 Indiana Legal

Forum 368, 376 (1972).

34

kind of reasoning has pervaded the thinking of educators,

the courts, and the public ever since. Up to 1954, innumer

able attempts were made to prove that the separate educa

tion of Negroes in the South was either equal or not equal

to white education by comparing schools in respect to

their location [“ inferior status of these school (is) the

enforced iso lation imposed * * * (by) neighborhood

schools and housing patterns, 313 F.Supp 61 at 83 (1970)],

the quality of their buildings [“ the fact that the physical

plant is old may aggravate the aura of inferiority which

surrounds the school,” 313 F.Supp. 61 at 81], the adequacy

of facilities, the number of courses in the curriculum, the

length of the school term, the paper credentials of teachers,

and most importantly, the amount of capital outlay and

annual expenditure per pupil.” Mosteller & Moynihari,

“On Equality of Educational Opportunity,” Dyer, pag*e

514, (Vintage Ed. 1972).

Since 1954, and Brown I, the Court has disposed of the

proposition, it too an educational myth, that to separate a

child by government policy from an available school be

cause of his race is somehow to treat him equally under

the law.

The Court is being pressed to create another myth in

its place, and in turn, to reinterpret Brown I. It is, es

sentially, that a minority child cannot be educated and

receive equal educational opportunity unless his separa

tion, from a majority group regardless of cause, is judi

cially destroyed.

“Proposition of Education, No. 2”:

The measure of equal educational opportunity is

found in counting the dollars and cents spent on

one school, or in one school district and comparing

that with another school district, or school.

35

Probably the most extreme form of this assertion is

found in the California case of Serrano v. Priest, 96 Cal.

601, 487 P.2d 1241 (1971). However, Mr. Dyer says this:

“ There is no guarantee that a more expensive in

stallation is inherently better, if only as a piece of

machinery, than a less expensive one. There is also

no guarantee that a more expensive laboratory is

capable of producing more language learning than

a less expensive one, or indeed no language labora

tory at all . # * * (During the period of excitement

over the possibilities for audio-lingual instruction,

many schools bought language labs that are now

gathering dust.)” “ Mosteller & Moynihan, “On

Equality of Educatonal Opportunity,” Dyer, page

514-515. (Vintage Ed. 1972).

“Proposition of Education, No. 3:”

Achievement Test Scores Determine the Education

Received; the Equality Thereof; and Whether There

is an Equal Educational Opportunity.

But a major educational reading does gainsay the state

ment :

“ The tendency is to assume that if on a reading

test the 6th-grade pupils in a slum school average

X points lower than those in a school in white

suburbia, then X is the measure of the difference

between the two schools in the effectiveness of

reading instruction. The case may be quite the op

posite: the slum school may be more effective than

the suburban school in upgrading reading com

petence, especially in light of the deficiencies it has

had to overcome.” “ Mosteller & Moynihan, “On

Equality of Educational Opportunity,” Dyer, page

515. (Vintage Ed. 1972).

36

D. On Experimentation In Education And The Fourteenth

Amendment

Certainly the State of Indiana does not say that there is

no relationship between money spent, excellence of teachers,

quality of facilities, teacher credentials, and the myriad

concepts relating to educational standards and educational

goals, and the product of the school system: the student.

Obviously, there is ; but equally obvious, or it should be, is

the fact that it is not yet determined to an extent that a

rule of Constitutional Law can be declared based upon it.

But if this Court were to approve the fashioning of an

equity decree, based upon, essentially, achievement criteria

and a disparity among them, then there would be a major

obstruction by the Judiciary in the environment and de

velopment of education programs, throughout Indiana and

the United States.16

“ One of the compelling reasons for educational

experiments is the importance for society of every

improvement in the learning process.” Mosteller &

Moynihan, “ On Equality of Educational Oppor

tunity,” Syw, page 377. (Vintage Ed. 1972).

But success is still not a certain thing. For example:

Indeed, after half a century of tightly controlled