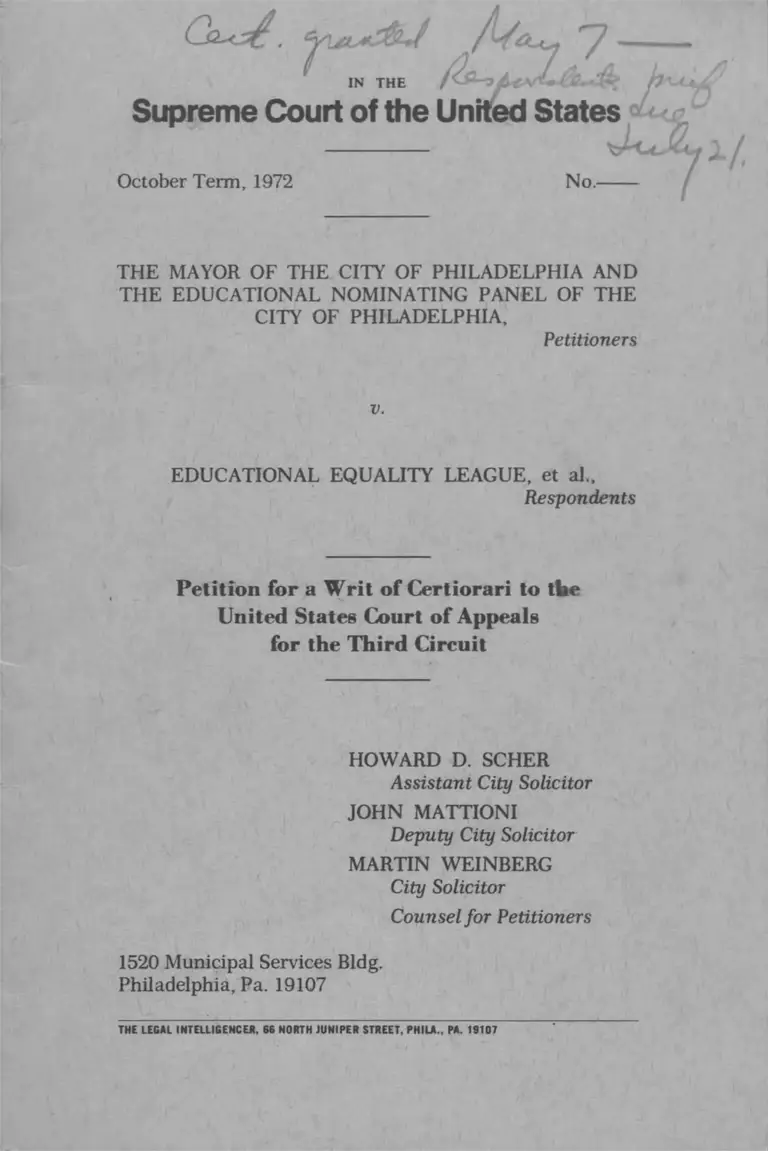

Philadelphia v. Educational Equality League Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Philadelphia v. Educational Equality League Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1972. b51b422c-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e9d4a8b2-f61e-46f6-aeb4-cea5cce3e110/philadelphia-v-educational-equality-league-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

____________ (L

October Term, 1972 No.------

THE MAYOR OF THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA AND

THE EDUCATIONAL NOMINATING PANEL OF THE

CITY OF PHILADELPHIA,

Petitioners

v .

EDUCATIONAL EQUALITY LEAGUE, et al„

Respondents

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Third Circuit

HOWARD D. SCHER

Assistant City Solicitor

JOHN MATTIONI

Deputy City Solicitor

MARTIN WEINBERG

City Solicitor

Counsel for Petitioners

1520 Municipal Services Bldg.

Philadelphia, Pa. 19107

THE LEGAL INTELLIGENCER, G6 NORTH JUNIPER STREET, PHILA., PA. 19107

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinion Below .......................................................... 2

Jurisdiction .............................................................. 2

Questions Presented................................................. 2

Statutory Provisions Involved................................... 3

Statement of the Case............................................... 10

Reasons for Granting the W r it .................................. 15

Conclusion................................................................ 29

Appendix................................................................. 30

Opinion and Judgment of District Court and Court of

Appeals and Order Amending Opinion of Court

of Appeals...................................................... 30, 38

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases:

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972 ................ 22

Commonwealth ex rel. Carroll v. Tate, et al„ 442 Pa.

45 (1971 )...................................... 23,24

Commonwealth ex rel. Specter v. Vignola, 446 Pa. 1

(1971)................ .26,27

Educational Equality League et al. v. Tate et al., 333

F. Supp. 1202 (E.D. Pa. 1971) . . ! .................... 2

Keim v. United States, 177 U.S. 289 (1899)................ 25

Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 135(1803)................ 24, 25

Naef v. Allentown, 424 Pa. 597 (1967)....................... 27

Philadelphia v. Sacks, 418 Pa. 193 (1965).................. 27

Schluraff v. Rzymek, 417 Pa. 144 (1965).................... 27

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970)....................... 22

i

TABLE OF C ITATIO NS— (Continued)

Cases: Page

United States v. Yellow Cab Company, 338 U.S. 338

(1949)...........................................................21,22

Statutes:

Federal Constitutional and Statutory Provisions:

U.S. Const., Art. II, Section 2 .............................3, 24

28 U.S.C. 1254(1)........................................... 2

28 U.S.C. 1343(3)........................................... 10

42 U.S.C. 1983 ................................................... 12

Pennsylvania Statutory Provisions:

First Class City Public Education Home Rule Act

of August 9, 1963, P.L. 643; 53 P.S. §13202 . . 3

Philadelphia Home Rule Charter....................... 3, 4

Philadelphia Home Rule Charter, Educational

Supplement ............................................... 4

Miscellaneous:

5A Moore’s Federal Practice Chapter 5 2 ............... 22

Rule 52(a) F.R.C.P....................................................17, 21

ii

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October T erm ,1972 No .■

THE MAYOR OF THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA AND

THE EDUCATIONAL NOMINATING PANEL OF THE

CITY OF PHILADELPHIA,

Petitioners

v .

EDUCATIONAL EQUALITY LEAGUE, et al„

Respondents

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

For the Third Circuit

The Petitioners,1 the Mayor of the City of Philadelphia

and the Educational Nominating Panel, respectfully pray

that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review the judgment and

opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit entered in this proceeding on January 11, 1973, as

modified on February 21, 1973, reversing the judgment of

the United States District Court for the the Eastern District

of Pennsylvania; finding that the former Mayor of the City

of Philadelphia had discriminated on the basis of race in

appointing to the Educational Nominating Panel; and

requiring the present Mayor of the City of Philadelphia to 1

1. When the cause was adjudicated in the District Court the

Mayor of the City of Philadelphia was the Honorable James H. J.

Tate. However, since the first Monday in January 1972, the Hon

orable Frank L. Rizzo has been Mayor. Mayor Rizzo has never

been made a party to this action.

1

2

submit evidence of his non-discrimination to the District

Court on remand.2

OPINION BELOW

The opinion, as modified, of the Court of Appeals, not

yet reported, appears in the Appendix hereto. The opinion

rendered by the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Pennsylvania is reported at 333 F. Supp. 1202

(E.D. Pa. 1971), and appears in the Appendix hereto.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit was entered on January 11, 1973. A timely petition

for re-hearing and re-hearing en banc was denied on Feb

ruary 22, 1973, and this Petition for Certiorari was filed

within ninety days of that date. The Court’s jurisdiction is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. Section 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Whether the Court of Appeals’ reversal based on a

finding of direct evidence of intent to discriminate on the

basis of race on the part of the former Mayor of the City of

Philadelphia violated the constraint of Rule 52(a) F. R. C. P.,

which limits reversals to clearly erroneous findings.

Whether evidence of statistical under-representation of

black persons combined with an opportunity to discrimi

nate is the appropriate formula to shift the burden of proof

in this case:

2. Respondents, the Educational Equality League, Floyd L.

Logan, W. Wilson Goode, Veronica Kellam, by her mother and next

friend, Elizabeth Kellam, and Michael Green, by his father and next

friend, Coolidge Green on behalf of themselves and all others

similarly situated, moved for the “Declaration of a Class Action”

which the District Court granted stating: “It is clear that a class con

sisting of all blacks in the City of Philadelphia meets all the require

ments of Rule 23(a).”

3

(1) Where the chief elected official’s discretionary

appointment power is being reviewed by the Court;

(2) Where the qualifications for appointment are defi

nite and limiting and have never been subjected to constitu

tional attack;

(3) Where, regardless of the executive’s involvement

and the limiting qualifications, the positions available are

so small in absolute number as to make statistical under

representation inconclusive at best; and

(4) Where the unrebutted evidence discloses that

under former Mayor Tate, minorities made very impressive

advancements in all fields and at all levels of City govern

ment.

Whether the Court of Appeals was justified in fashion

ing its Order prospectively where the foundation of the

holding was based on evidence of practices of former Mayor

James H. J. Tate’s administration and where absolutely no

evidence exists that the present Mayor, not a party to the

action, Frank L. Rizzo, has discriminated.

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

United States Constitution, Article II:

Section 2. The President . . . shall nominate

and, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate,

shall appoint . . . all other officers of the United

States. . . . But the Congress may by law vest the

appointment of such inferior officers, as they think

proper in the President along. . . .

First Class City Public Education Home Rule Act of August

9, 1963, P.L. 643 [53 P.S. §13202 (Pocket Part 1972-73)]:

Article II, Section 2: Cities empowered. Any city

of the first class may frame and adopt charter provi

sions governing the administration of a separate and

independent home rule school district. . . .

Philadelphia Home Rule Charter, Adopted by the Electors

April 17,1951:

4

Section 3-404. All other officers. Except as ex

pressly otherwise provided in this charter, all ap

pointed officers and all members and all officers of

boards and commissions shall serve at the pleasure

of the appointing power. . . .

Philadelphia Home Rule Charter, Educational Supplement,

Adopted by the Electors, May 18,1965:

ARTICLE XII

PUBLIC EDUCATION

CHAPTER 1

THE HOME RULE SCHOOL DISTRICT

Section 12-100. The Home Rule School District.

A separate and independent home rule school district

is hereby established and created to be known as “The

School District of Philadelphia.”

Section 12-101. The New District to Take Over All

Assets and Assume All Liabilities of the Predecessor School

District.

The home rule school district shall

(a) succeed directly the now existing school district

for all purposes, including, but not limited to, receipt of all

grants, gifts, appropriations, subsidies or other payments;

(b) take over from the now existing school district all

assets, property, real and personal, tangible and intangible,

all easements and all evidences of ownership in part or in

whole, and all records, and other evidences pertaining

thereto; and

(c) assume all debt and other contractual obligations

of the now existing school district, any long term debt to

be issued, secured and retired in the manner now provided

by law.

5

CHAPTER 2

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION

Section 12-200. The Board Created; Its Function.

There shall be a Board of Education of the School Dis

trict of Philadelphia which shall be charged with the ad

ministration, management and operation of the home rule

school district.

Section 12-201. Members of the Board; Method of

Selection.

There shall be nine members of the Board of Education

who shall be appointed by the Mayor from lists of names

submitted to him by the Educational Nominating Panel,

or, if enabling legislation is enacted by the General Assem

bly of the Commonwealth, elected on a non-partisan basis

by the qualified voters of the city, all as more fully set forth

in later sections of this Chapter.

Section 12-202. Eligibility for Board Membership.

Members of the Board of Education shall be registered

voters of the City. No person shall be eligible to be ap

pointed or elected to more than two full six-year terms.

Section 12-203. Terms of Board Members.

The terms of members of the Board of Education shall

begin on the first Monday in December and shall be six

years except that (1) of the first members of the Board

appointed and if later there be an elective Board, of the first

members elected, three shall be appointed or elected for

terms of two years, three for terms of four years, and three

for terms of six years, and (2) if the General Assembly

enacts legislation permitting the election of members of

the Board on a non-partisan basis, the terms of all ap

pointed members shall expire on the first Monday of

December immediately following the municipal election

at which the first elective Board is elected.

6

Section 12-204. Removal of Members of the Board.

Members of the Board of Education may be removed

as provided by law.

Section 12-205. Vacancies on the Board.

A vacancy in the office of member of the Board of

Education shall be filled for the balance of the unexpired

term in the same manner in which the member was

selected who died or resigned. If a member of the Board

is removed from office, the resulting vacancy shall be

filled as provided by law.

Section 12-206.EducationalNominatingPanel; Method

of Selection.

(a) The Mayor shall appoint an Educational Nominat

ing Panel consisting of thirteen (13) members. Members

of the Panel shall be registered voters of the City and shall

serve for terms of two years from the dates of their appoint

ment.

(b) Nine members of the Educational Nominating

Panel shall be the highest ranking officers of City-wide

organizations or institutions which are, respectively:

(1) a labor union council or other organization

of unions of workers and employes organized and

operated for the benefit of such workers and employes,

(2) a council, chamber, or other organization

established for the purpose of general improvement

and benefit of commerce and industry,

(3) a public school parent-teachers association,

(4) a community organization of citizens estab

lished for the purpose of improvement of public educa

tion,

(5) a federation, council, or other organization

of non-partisan neighborhood or community associ

ations,

7

(6) a league, association, or other organization

established for the purpose of improvement of human

and inter-group relations,

(7) a non-partisan committee, league, council,

or other organization established for the purpose of

improvement of governmental, political, social, or

economic conditions,

(8) a degree-granting institution of higher educa

tion whose principal educational facilities are located

wihin Philadelphia, and

(9) a council, association, or other organization

dedicated to community planning of health and wel

fare services or of the physical resources and environ

ment of the City.

(c) In order to represent adequately the entire com

munity, the four other members of the Educational Nom

inating Panel shall be appointed by the Mayor from the

citizenry at large.

(d) In the event no organization as described in one

of the clauses (1) through (9) of subsection (b) exists within

the City, or in the event there is no such organization any

one of whose officers is a registered voter of the City, the

Mayor shall appoint the highest ranking officer who is a

registered voter of the City from another organization or

institution which qualifies under another clause of the

subsection.

(e) A vacancy in the office of member of the Educa

tional Nominating Panel shall be filled for the balance of

the unexpired term in the same manner in which the mem

ber was selected who died, resigned, or was removed.

(f) The Educational Nominating Panel shall elect its

own officers and adopt rules of procedure.

Section 12-207. The Educational Nominating Panel;

Duties and Procedure.

(a) The Mayor shall appoint and convene the Educa

tional Nominating Panel (1) not later than May twenty-

8

fifth of every odd-numbered year, and (2) whenever a

vacancy occurs in the membership of the Board of Edu

cation.

(b) The Panel shall within forty (40) days submit to

the Mayor three names of qualified persons for every place

on the Board of Education which is to be filled. If the Mayor

wishes an additional list of names, he shall so notify the

Panel within twenty (20) days. Thereupon the Panel shall

within thirty (30) days send to the Mayor an additional list

of three qualified persons for each place to be filled. The

Mayor shall within twenty (20) days make an appointment

or, as provided in the following subsection, certify a nomi

nation from either list for each place to be filled.

(c) If the General Assembly of the Commonwealth

shall have previously enacted enabling legislation per

mitting members of the Board of Education to be elected

on a non-partisan basis, not later than September fifteenth

of the odd-numbered year in which the legislation was

enacted or the ensuing odd-numbered year, the Mayor shall

select nine names from either one or two lists of 27 names

submitted by the Educational Nominating Panel according

to the procedure set forth in subsection (b) and shall certify

those nine names to the county board of elections as his

nominations for members of the Board of Education. In

certifying the names of his nominees to the county board

of elections the Mayor shall designate three of his nominees

as candidates for terms of two years, three for terms of four

years and three for terms of six years. The ballots or ballot

labels shall not contain any party designation for any of

the candidates nominated by the Mayor, and under each

name there will be a space permitting the voter to write

in the name of any other person. In every instance the

Mayor s candidate will be elected if, but only if, he receives

more votes than any other candidate whose name is written

in. In every subsequent odd-numbered year, three members

of the Board shall be nominated by the Mayor from names

submitted to him by the Educational Nominating Panel

and elected in the same manner provided by this subsection.

9

and whenever a vacancy occurs the procedure for filling

it shall be similar whether the vacancy be filled at a special

election proclaimed by the Mayor or at a municipal election.

(d) The Educational Nominating Panel shall invite

business, civic, professional, labor, and other organizations,

as well as individuals, situated or resident within the City

to submit for consideration by the Panel the names of

persons qualified to serve as members of the Board of

Education.

(e) Nothing herein provided shall preclude the Panel

from recommending and the Mayor from appointing or

nominating persons who have previously served on any

board of public education other than the Board of Educa

tion created by these charter provisions.

10

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The jurisdiction of the District Court was invoked

under 28 U.S.C. Section 1343 (3) alleging violation of 42

U.S.C. Section 1983. Specifically, the Educational Equality

League alleges that the former Mayor of the City of Phila

delphia discriminated on the basis of race in his appoint

ments to the Educational Nominating Panel, in May of

1971.

The method of appointing persons to the Educational

Nominating Panel is established by the Educational Sup

plement to the Philadelphia Home Rule Charter, approved

by the electors on May 18, 1965, pursuant to the Act of

August 9, 1963, P. L. 643, 53 P. S. Sections 13201-13223.

The constitutionality of the Charter has not been ques

tioned.

The Charter provides that during every odd-numbered

year the Mayor shall appoint and convene a panel of 13

qualified persons to be called the Educational Nominating

Panel ( “Panel”). The function of this panel is to nominate

three persons for each vacancy on the Board of Education

of the School District of Philadelphia (“Board”). From the

three persons (or six persons since, if the Mayor desires an

additional three persons for each vacancy, he merely

requests additional names), the Mayor selects and appoints

a person to the vacancy on the Board. The Mayor’s appoint

ments to the Board have not been challenged, nor indeed,

has the quality or dedication of the actual appointees

been questioned.

The qualifications for appointment to the Panel vary.

Four (4) Panel members must be from the “citizenry at

large” “ [i]n order to represent adequately the entire

community. . . .” Charter, 12-206(c).3 The remaining

nine (9) panel members “shall be the highest ranking

3. The Mayor can, i f he chooses on his own initiative,

appoint from additional organizations of his own selection to

fill these four “at large” positions.

11

officers of City-wide organizations or institutions. . .

Charter, 12-206(b). These organizations are described with

particularity as:

(1) a labor union council or other organization

of unions of workers and employes organized and

operated for the benefit of such workers and employes,

(2) a council, chamber, or other organization

established for the purpose of general improvement

and benefit of commerce and industry,

(3) a public school parent-teachers association,

(4) a community organization of citizens es

tablished for the purpose of improvement of public

education,

(5) a federation, council, or other organization

of non-partisan neighborhood or community asso

ciations,

(6) a league, association, or other organization

established for the purpose of improvement of human

and inter-group relations,

(7) a non-partisan committee, league, council,

or other organization established for the purpose of

improvement of governmental, political, social, or

economic conditions,

(8) a degree-granting institution of higher edu

cation whose principal educational facilities are

located within Philadelphia, and

(9) a council, association, or other organization

dedicated to community planning of health and wel

fare services or of the physical resources and environ

ment of the City.

Charter, 12-206(b) (1>(9).

On May 25, 1971, Mayor Tate appointed and con

vened the Panel.

On August 6, 1971 the Educational Equality League

sued Mayor Tate and the Panel alleging the Mayor made

his appointments on racial criteria in violation of the Civil

12

Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. Section 1983 and requesting

a speedy hearing, an injunction against the panel from

acting, a judgment declaring that the Mayor discriminated

on the basis of race and an order directing the Mayor to

appoint a panel “fairly representative of the racial com

position of the school community.” Complaint, p. 8.

After expedited pre-trial discovery was completed a

hearing was held on August 25 and September 7, 1971

before the Honorable Raymond Broderick, Judge of the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Pennsylvania.

At the hearing, the Educational Equality League at

tempted to offer evidence to support two theories: that the

Mayor directly and personally discriminated against black

persons when he appointed the Panel; and that the statisti

cal evidence demonstrating the percentage of blacks in the

general population of Philadelphia and the percentage of

black students in the population of the School District of

Philadelphia as compared with the percentage of blacks

appointed to the thirteen member Panel creates a pre

sumption of discrimination by the Mayor.

The Mayor and Panel offered evidence to support

several theories of defense: that the appointments of the

Mayor are protected from judicial interference by virtue

of the executive’s inherent discretion and the consti

tutionally mandated doctrine of separation of powers; that

the Mayor’s appointments satisfied the qualifications

required by the Charter; that the qualifications required by

the Charter vitiated the applicability of the Educational

Equality League’s statistical theory since more than mere

citizenship and residency are required by the Charter to

qualify for appointment to the Panel; and that the statisti

cal theory is invalid as applied to the Panel since the Panel

is so small that each individual change on the Panel results

in extremely large changes in percentages. Finally, evi

dence established that the Mayor personally championed

the expansion of opportunity for blacks in City employment

as well as in appointed and elective political positions and

13

evidence was offered to contradict any assertion of personal

discrimination as to the Mayor.

On November 8, 1973, the District Court issued its

Findings of Facts, Conclusions of Law and Order, dis

missing the complaint with prejudice. 333 F. Supp. 1202.

The District Court found inapplicable the “percentage

rationale,” i.e., the Educational Equality League’s theory

that a prima facie case or presumption of discrimination

can be proved by comparing the percentage of blacks in

the population of the City of Philadelphia with the per

centage of blacks appointed to the 1971 Panel. 333 F.

Supp. at 1207.

The District Court discussed but refused to find that

the Mayor had discriminated on the basis of race in his

appointments to the 1971 Panel.

The District Court did not reach the questions of

executive discretion and separation of powers, although it

expressed doubts as to its power to interfere with the dis

cretion of an elected executive in his discretionary ap

pointments. 333 F. Supp. at 1206.

The District Court did not reach or discuss the inap

plicability of the percentage rationale in relation to the

qualifications required by the Charter beyond citizenship

and residency.

On November 9, 1971, the Educational Equality

League filed a Notice of Appeal to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Third Circuit.

On December 5, 1972 argument on the briefs was

heard by Judges Van Dusen, Gibbons and Hunter.

On January 11, 1973 the Court of Appeals issued its

judgment vacating the judgment of the District Court

except as to the Educational Nominating Panel, and re

manding the cause to the District Court for further pro

ceedings.

Timely Petitions for Rehearing were filed by each

party, and a Petition for Rehearing En Banc was filed by

the Mayor of the City of Philadelphia. All were denied, the

Educational Equality League’s on February 21, 1973 and

the Mayor’s on February 22, 1973.

14

On February 21, 1973 the Court of Appeals entered

an order amending its order of January 11, 1973. The

Court of Appeals found as a fact that the appointments by

the Mayor to the Panel were not within the executive’s

discretion and that the selection process had a discrimina

tory effect. The Court of Appeals applied the percentage

rationale holding that demonstrating under-representation

and an opportunity for discrimination is all that is neces

sary to establish a prima facie case. Finally, the Court of

Appeals found as a fact that the former Mayor had dis

criminated on the basis of race in his selections to the

Panel and based on this finding, required the present

Mayor to submit the bases for his executive judgments to

the scrutiny of the District Court on remand.

These findings by the Court of Appeals were directly

contrary to those made by the District Court. Furthermore,

it failed to consider the evidence adduced that directly

contradicted the witness relied upon by the Court of

Appeals, and the evidence establishing that Mayor Tate

had personally opened areas of opportunity to minorities

that had previously been denied them.

The Mayor of the City of Philadelphia and the Edu

cational Nominating Panel moved the Court of Appeals for

a Stay of its Mandate pending Petition to the Supreme

Court for a Writ of Certiorari. The Court of Appeals ordered

its mandate stayed for 15 days with “no further extension.

. . .” Order of United States Court of Appeals, March 2,

1973.

15

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Although ostensibly involving only one relatively

insignificant panel appointed by the highest elected official

of the City of Philadelphia, this case involves grave national

consequences. As a direct result, and without precedent, the

present Mayor of the City of Philadelphia, without even

having been accused of racial discrimination, is required to

submit his executive judgment to the District Court for the

Eastern District of Pennsylvania regarding the selection

of members of the Panel. The Mayor of the City of Phila

delphia has the power of appointment to a broad variety

of boards and commissions by virtue of statutes, Home Rule

Charter, and Ordinance. Now, if and when racial per

centage disparities appear, the Mayor will be subjected to

the burden of disproving racial discrimination. Likewise,

both statewide and nationally, the logical progeny of the

holding of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit would require elected officials throughout the nation

to defend and offer positive proof of their nondiscrimination

in their executive appointments, whenever percentage

disparities appear.

Perhaps, the most obvious situation is with the judi

ciary. If we assume a disproportionately small percentage

of blacks in the Federal judiciary as compared to their

proportion of the national population, this case would

require the President of the United States substantiate by

positive proof his nondiscrimination in his judicial appoint

ments and further substantiate his proper consideration

of blacks when making these appointments.

But, beyond the conclusions of law reached by the

Court of Appeals there is one finding of fact of grave per

sonal importance. The United States Court of Appeals for

the Third Circuit found as a fact that the former Mayor of

the City of Philadelphia James H. J. Tate, engaged in

unlawful racial discrimination in his appointments to the

Educational Nominating Panel. It held that his appoint

ments to the Panel were “tainted.” It held that there was

16

direct proof of the former Mayor s personal discrimination

against black people.

Without attempting to portray former Mayor Tate as

anything more than an astute politician, the record which

Mayor Tate established over his decades of public service

evidences a total commitment to the expansion of oppor

tunities to minority groups, including black persons, at all

levels of public service employment as well as in political

appointments. The record in the District Court discloses

an ever-increasing number of black persons employed at

all levels of government service over the decade of former

Mayor Tate’s administration. And yet, as the result of the

Court of Appeals opinion the final but critical and unfair

judgment of Mayor Tate’s Administration is that of dis

crimination against black persons on the basis of their race.

The evidence of non-discriminatory public service was

overwhelming. The evidence to the contrary was unsub

stantial.

This Court should grant the Petition for this reason

if for no other, for it is now the true Court of last resort. A

finding of racial discrimination in the face of over-all

employment of black people exceeding by nearly ten per

cent (10%) their proportion of the population of the City

is hardly justified.

Finally, in terms of relief, the Court of Appeals has

directed the District Court to apply the Appellate Court’s

Finding of Fact that Mayor Tate discriminated to the new

Mayor, Frank L. Rizzo. There is no evidence in the record

concerning the administration of Mayor Rizzo. The Court

of Appeals has, nevertheless, ordered that Mayor Rizzo

submit evidence to substantiate his nondiscrimination in

appointments to the Educational Nominating Panel. Thus,

not only has the Court of Appeals arbitrarily made Findings

of Fact which the District Court could not have made, but

it has now assumed that the finding of racial discrimination

can in some way be transferred to another person who

obviously could not have been a party to its first finding.

Such a decision would, it seems, bind all future Mayors,

17

constituting an unlawful infringement of the constitutional

scheme of government.

Point 1

In direct conflict with Rule 52(a) of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure as well as numerous decisions of this

Court, the Court below made findings of fact not only

without finding clear error by the District Court but

without any support on the record before it.

As has been discussed above, the Court of Appeals

reversed the District Court on two bases.

The Educational Equality League had offered two

theories in support of their cause of action. One involved

indirect proof of discrimination by the so-called “percen

tage rationale.” The other involved direct proof of dis

crimination on the part of the Mayor, the appointing

authority.

In its Opinion and Order of November 8, 1971, the

District Court discussed and reviewed the purported direct

evidence of discrimination offered by the Educational

Equality League. It rejected this testimony.

The Court of Appeals specifically reversed the Order

of the District Court and made findings of fact unsupported

in the record and without establishing clear error. It found

that a number of black oriented organizations met the

specifications of seven of the nine categories of Section

12-206(b) of the Charter (Court of Appeals, Opinion Page 6),

and that one witness, Mr. W. Wilson Goode testified with

out contradiction or objection that the then Mayor had

stated he would appoint no blacks to the Board of Education

in addition to the two already on it (Court of Appeals,

Opinion Page 6). The Court of Appeals found that Deputy

Mayor Zecca was unaware of the existence of black ori

ented organizations which were within the requirements

of Section 12-206(b) of the Charter (Court of Appeals,

Opinion Page 6). Finally, the Court of Appeals found that

the District Court had “overlooked” Goode’s testimony about

18

the Mayor’s statement referred to above (Court of Appeals,

Opinion Page 7).

In fact, there is no evidence of qualifying black organi

zations existing in the categories required by the Charter.

Goode testified but was contradicted by witnesses for the

Mayor of the City of Philadelphia: Clarence Farmer, Chair

man of the Philadelphia Human Relations Commission

and Anthony P. Zecca, Deputy to the then Mayor James

H. J. Tate. Goode testified that there were one or two

organizations which had black leadership which satisfied

the categories of the Charter. However, in his own testi

mony, the deficiencies of these organizations are made

evident. For example, to satisfy the qualifications of Section

12-206(b)(l), Goode offered the United Negro Trade Union.

His testimony was:

Q. What does the United Negro Trade Unions

represent?

A. That represents all of the union officials who

are black and who are in unions in Philadelphia. It is

a kind of council of other officials of other black unions.

(Goode, N.T. 4-5.)

It is apparent that the District Court refused to find

that there were black organizations which qualified under

the Charter because, by definition, an organization which

is limited to black membership is not a City-wide organiza

tion. None of the organizations which are represented on

the Educational Nominating Panel have membership which

is exclusive or exclusionary. With the possible exception

of the Urban League, the organizations referred to by Goode

excluded non-black membership.

On the other hand, Zecca’s testimony disclosed that

the organizations selected satisfied precisely the require

ments of the Charter. The fact that Zecca knew of no other

organizations to qualify under 12-206(b) (1), proves no

thing, other than that there may be no other such organi

zation in the City of Philadelphia of such qualifications.

19

Furthermore, Zecca’s testimony discloses the conscientious

effort made to comply with the specific provisions of the

Charter. In short, there is no evidence to substantiate the

finding made by the Court of Appeals that there exists a

number of black-oriented or black-lead organizations which

meet the specifications of the Charter. The blacks on the

Panel came from organizations that were black-lead, but

which were not discriminatory in their membership.

The Court of Appeals improperly found that: “al

though the District Court made no finding on the subject,

Mr. Goode testified, without contradiction or objection,

that shortly before the 1969 panel was due to be appointed

at a time when there was one vacancy for which the 1967

panel had not yet made its nominations, the Mayor

stated that he would appoint no blacks to the Board of

Education in addition to the two already on it.” (Court of

Appeals, Opinion Page 6).

Even if true, this statement was allegedly made with

reference to the 1969 Panel and not the 1971 Panel. There

is no testimony at all relating to the appointment of the

1971 Panel or Board appointments from its nominations.

This statement by Goode was, furthermore, clearly

and directly contradicted by the testimony of Zecca. Zecca

testified:

Q. Mr. Zecca, we were discussing earlier a state

ment by Mayor Tate in 1969 that he would not ap

point any additional Negroes to the School Board and

you said you didn’t recall that statement.

A. I said I don’t think he made such a statement.

Q. Well all right.

May I show you a very bad copy of the page of the

Philadelphia Inquirer, Saturday, May 3, 1969, and

the article says, “he indicated”, referring to the

Mayor, “he would not appoint another Negro to the

Board because the Negro community has good repre

sentation in the two Negroes now serving on the

Board.”

* * *

20

Do you recall that article?

A. The witness: “I don’t recall the article spe

cifically but it doesn’t say he is not going to name

another member. It said that he indicated that he

wouldn’t name another member; and this is, of course,

the reporter’s version of this, but the quote said the

Negro community has good representation in the two

Negroes now serving on the Board.

They may have asked him whether he was going

to appoint anymore Negroes to the Board and he said

the Negro community has good representation on the

Board as it is; just like it has excellent representation

right in this story.” (Zecca, N.T. 259-261)

In fact, the entire colloquy involves the Mayor’s

intention to appoint persons to the Board, and not the

Panel. As has previously been stated the Educational

Equality League has made no challenge to the appoint

ments to the Board, but has limited its grievance to the

appointments made to the Panel. Therefore, the testimony

offered with regard to the Board is irrelevant. But beyond

its irrelevancy, it is clearly contradicted by the testimony

of Zecca which indicates that the statement may not have

been made and if it was made may have been a misquote.

It was improper for the Court of Appeals to make a

finding which the District Court refused to make based

upon obvious hearsay which was contradicted by other

proper evidence. This type of evidence, involving credibility

and demeanor, is best left to the determination of a district

court.

Also improper was the misstatement by the Court of

Appeals of the District Court’s Finding of Fact No. 17:

The person assigned by the Mayor of Phila

delphia to choose the groups under the enumerated

categories Deputy Mayor Anthony Zecca, at the time

of the hearing in the instant case was unaware of the

existence of many of these black organizations. (Ap

pendix, Page 6a) (Emphasis added.)

21

The Court of Appeals stated that:

The District Court found that Deputy Mayor

Zecca was unaware of the existence of black oriented

organizations which were within the requirements

of Section 12-206(b). (Court of Appeals, Opinion

Page 6.)

The statement by the Court of Appeals is internally

inconsistent in that black orientation is a requirement

which is mutually exclusive of the requirement that

organizations be Citywide in nature.

Rule 52 (a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

prohibits a Court of Appeals from setting aside Findings

of Fact made by a District Court unless those findings are

clearly erroneous.

Findings of Fact shall not be set aside unless

clearly erroneous, and due regard shall be given to

the opportunity of the trial court to judge of the

credibility of the witnesses.

Rule 52 F.R.C.P.

Rule 52 is particularly applicable to the situation in

which the intention of a party is at issue. Here, Goode

testified to the intention of the Mayor. As this Court said

in United States v. Yellow Cab Company:

Finding as to the design, motive and intent with

which men act depend peculiarly upon the credit

given to witnesses by those who see and hear them.

.. . The trial court listened to and observed the officers

who had made the records from which the govern

ment would draw an inference of guilt and concluded

that they bear a different meaning from that for which

the government contends.

It ought to be unnecessary to say that Rule 52

applies to appeals by the government as well as to

those by other litigants. There is no exception which

permits it, even in an anti-trust case, to come to this

22

Court for what virtually amounts to a trial de novo

on the record of such findings as intent, motive and

design. While, of course, it would be our duty to

correct clear error, even in findings of fact, the

government has failed to establish any greater

grievance here than it might have in any case where

the evidence would support a conclusion either way

but where the trial court has decided to weigh more

heavily for the defendants. Such a choice between two

permissible views of the weight of evidence is not

“clearly erroneous.”

United States v. Yellow Cab Company, 338 U.S. 338, 341-

342(1949).

So long as the Finding of Fact or failure to find a fact

is substantiated on the record, the District Court’s finding

or failure to find may not be reversed. See also, 5 A Moore’s

Federal Practice Chapter 52.

The burden of proof remains upon the plaintiff even

in civil rights cases. The conduct of the Court of Appeals

in this case would assume that any statement by a person

that another has discriminated, must be taken as true.

This is not only legally improper, but also contrary to

human experience.

Point 2

The decision below is in direct conflict with both Federal

and Pennsylvania law regarding the appointing

power of elected officials.

The second theory upon which the United States

Court of Appeals based its reversal of the District Court’s

judgment is that of the percentage rationale. Construing

the decisions of this Court in Turner v. Touche, 396 U.S.

346 (1970) and Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625

(1972) the Court of Appeals held that to prevail under the

percentage rationale a

23

plaintiff need not show a deliberate practice of

discrimination; a prima facie case is established by

a demonstration that blacks were under represented

and that there was an opportunity for racial dis

crimination. Opinion of the Court of Appeals, Page 10.

While this theory of proof has been applied to jury

selection cases, voting registration cases and employment

discrimination cases, it has never been applied to situa

tions in which the discretion of a duly elected official in

his appointing power has been in question. Indeed, there

are a variety of reasons for not applying the percentage

rationale to this and similar situations, the most funda

mental of which is that principle of American political

philosophy that requires the three branches of government

to be separate and coequal and that no one branch should

be the repository of ultimate power. This principle requires

that the judicial branch be loath to interfere in areas of

purely legislative or executive concern and likewise in

areas of judicial concern the executive and legislative

branches should not interfere. As the Pennsylvania

Supreme Court recently stated:

The line of separation or demarcation between

the Executive, the Legislative and the Judicial, and

their respective jurisdiction of powers, has never

been definitely and specifically defined, and perhaps

no clear line of distinction can ever be drawn.

Commonwealth ex rel. Carroll v. Tate et al., 442 Pa. 45,

51 (1971).

In Carroll v. Tate, supra, the issue involved a legisla

tive encroachment on the judiciary. This case, of course,

involves a judicial invasion of the executive. Great caution

must be employed in this area, for as the Pennsylvania

Supreme Court continued:

The very genius of our tripartite government is

based upon the proper exercise of their respective

powers together with harmonious cooperation between

24

the three independent branches. Commonwealth ex

rel. Carroll v. Tate, et al., supra 53.

Included in this Court’s consideration of the issues

here, must, therefore, be the constant consideration of the

fundamental principles of American government. The

United States Constitution in Article II, Section 2, places

in the executive branch certain defined powers. These

powers are given generally by and with the advice and

consent of the Senate, however, the Constitution further

provides:

[B]ut the Congress may by law vest the appoint

ment of such inferior officers, as they think proper in

the President alone . . . U.S. Const, art. II, §2.

The landmark decision in Marbury v. Madison, 1

Cranch 135 (1803) presents an analogous situation on the

national level. The importance of the President’s discretion

might be considered far greater than the Mayor’s discretion.

And yet, the difference is only one of quantity and not

quality. For the prerogatives of the executive branch in a

tripartite government are constant, and any court, as the

representative of the judiciary, should not interfere in this

area.

The facts of Marbury are so well known they need only

be summarized here. Plaintiff was an appointee of the

President and while the appointment had been made, it had

not been delivered. Plaintiff sought an Order in Mandamus

commanding the Secretary of State to deliver the appoint

ment. In discussing the correctness of the remedy, the

Court said:

With respect to the officer to whom it would be

directed, the intimate political relation subsisting

between the President of the United States and the

heads of departments, necessarily renders an illegal

investigation of the acts of one of those high officers

peculiarly irksome, as well as delicate; and excites

some hesitation with respect to the propriety of enter

ing into such investigation.

25

Marbury, supra 71.

But more importantly:

Where the head of a department acts in a case

in which executive discretion is to be exercised . . .

it is again repeated, that any application to a Court to

control, in any respect, his conduct would be rejected

without hesitation.

Marbury, supra 71.

The first paragraph quoted above, speaks of the bases

for the doctrine of judicial restraint in political questions,

a policy argument. However, the second paragraph, states

a principle of law which denies judicial interference in the

area of executive discretion. Applied to the present litiga

tion, Marbury stands for the proposition that lawful appoint

ments within the discretion of the Mayor may not be

disturbed except that once an irrevocable appointment is

made a Court may order its ministerial execution. Although

the complaint in the matter at hand does not directly ask

for mandamus, the actual relief granted by the Court of

Appeals requires the dissolution of appointments and new

appointments made. These new appointments must more

adequately represent the black population. This adequate

representation can only be achieved by increasing the

number of blacks on the Panel. Therefore, the present

Mayor of the City of Philadelphia is required to appoint

more blacks than at present to the Panel. The import of this

decision of the Court below requires that the Mayor abandon

his judgment and discretion and perform that purely execu

tive function of appointing in an automatic and ministerial

way. This or any similar limitation on the powers of the

chief executive is totally impermissible and the District

Court properly refused to entertain such an invasion of

executive discretion, although it did not reach the issue. As

this Court said in Kcim v. United States. 177 U.S. 289

(,1899):

26

The appointment to an official position in the

government, even if it be simply a clerical position,

is not a mere ministerial act but one involving the

exercise of judgment. The appointing power must

determine the fitness of the applicant; whether or not

he is the proper one to discharge the duties of the

position. Therefore, it is one of those acts over which

the Courts have no general supervising power.

The particular reasons for the executive’s discretion

in this case are readily discernible in the record and are

in keeping with the theme of the entire Home Rule Charter,

the organic law of the City of Philadelphia. That theme or

theory of government is to place in the hands of the execu

tive the responsibility for his actions. It is obvious that only

if the Mayor has the right to choose will the responsibility

for the choice be his.

The general principle of law mandated by the doctrine

of separation of powers requires that the judiciary not inter

fere in the executive’s discretionary appointments; and the

organic law of the City of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia

Home Rule Charter, and the general law of the Common

wealth of Pennsylvania requires non-interference in such

appointments as well. Subject to those specifically provided

for qualifications, all appointees to boards and commissions

under the Home Rule Charter are appointed and serve at

the pleasure of the Mayor. Section 3-404 of the Home Rule

Charter provides as follows:

All other officers. Except as expressly otherwise

provided in this Charter, all appointed officers and

all members and all officers of boards and commis

sions shall serve at the pleasure of the appointing

power and until their successors are qualified.

The Charter’s statement on the law is consistent with

that of the Commonwealth. In Commonwealth ex rel.

Specter v. Vignola, 446 Pa. 1 (1971) the Supreme Court of

Pennsylvania held that:

27

Appointed public officers are removable from

office at the pleasure of the appointing power. . . .

Commonwealth ex rel. Specter v. Vignola, supra. Accord,

Naef v. Allentown, 424 Pa. 597 (1967); Philadelphia v.

Sacks, 418 Pa. 193 (1965); Schluraff v. Rzymek, 417 Pa.

144(1965).

Absent proof of actual discrimination by the Mayor,

there can be absolutely no justification for the Court of

Appeals’ opinion. The record clearly refutes any discrimina

tion in these specific appointments.

The Petition should, therefore, be granted.

Point 3

The Court below was unjustified in requiring that the pres

ent Mayor, the Honorable Frank L. Rizzo, submit

“evidence that the organizations in the black com

munity which qualify have received proper considera

tion” in making his appointments to the Panel.

The present suit was brought against James H. J. Tate.

At no time was evidence produced regarding the adminis

tration of Frank L. Rizzo, Tate’s successor in office. Mayor

Rizzo had not yet assumed office. In fact the decision of the

District Court was made prior to Mayor Rizzo’s election.

Therefore, there could be no evidence whatsoever regarding

the practices of the present Mayor, Frank L. Rizzo, before

the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit.

And yet, anomalously, the Court of Appeals ordered the staff

of Mayor Rizzo to submit to the District Court evidence of

non-discrimination in appointments to the Panel.

Footnote 21 of the Court of Appeals’ decision suggests

the rationale for this direction to the District Court.

“21. Mayor Tate has been succeeded by the Hon

orable Frank L. Rizzo and the present case has, of

course, involved no showing that Mayor Rizzo has in

any way discriminated against blacks. Nevertheless,

28

on this record, Mr. Zecca continues as a Deputy Mayor

and since this Court finds that plaintifff has shown

on this record discrimination in regard to the present

panel, the Federal Courts must assure that the appoint

ment of the 1973 panel is free from taint. Cf Conover

v. Montemuro,------F. 2 d -------(1972) (3rd Cir. No.

71-1871, filed December 20, at page 13)” (Court of

Appeals, Opinion page 12.) (Emphasis added.)

There is no record to substantiate the assumption that

Mr. Zecca has today any responsibility for appointments

to the Panel. Zecca is Deputy to Mayor Rizzo. Under Mayor

Tate he was alone in this position. However, under the

present Mayor, Philip R. T. Carroll is the Mayor’s immediate

subordinate and it is he who oversees the Mayor’s office.

Zecca, as Deputy to the Mayor, shares this title with

Michael Wallace, Esquire. In addition, there are now three

assistants to the Mayor. Based on the change in personnel,

it would be equally reasonable to assume that the entire

nomination process for membership or appointments to

Boards and Commissions has been considerably altered.

Although there is no evidence bearing on the subject, the

fact is that the procedure for filling such positions has been

completely revised.

Even if Mayor Tate can properly be found to have

practiced personal discrimination, there is no justification

on this record to assume or even suspect, that Mayor Rizzo

would act in a similar manner. Therefore, the direction to

the Court below to enjoin the present Mayor from dis

crimination is both unwarranted and unjustified. The

selection process with respect to the Panel had been chal

lenged only as it involved the then Mayor Tate. While

systematic exclusion remains unlawful, there was and is

no such allegation as to the present administration.

29

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, a Writ of Certiorari should issue to

review the judgment and opinion of the Third Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

HOWARD D. SCHER

Assistant City Solicitor

JOHN MATTIONI

Deputy City Solicitor

MARTIN WEINBERG

City Solicitor

1520 Municipal Services Bldg.

Philadelphia, Pa. 19107

30

APPENDIX

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

Civil Action No. 71-1938

EDUCATIONAL EQUALITY LEAGUE, et al.

v.

HONORABLE JAMES H. J. TATE, et al.

FINDINGS OF FACT

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

Broderick, J. November 8,1971

This class action was brought by the Educational

Equality League and certain named individuals on behalf

of themselves and all other similarly situated in Phila

delphia, seeking injunctive and other relief to prohibit the

defendant, Mayor of Philadelphia, James H. J. Tate, from

continuing his alleged racial discrimination in making

appointments to the Educational Nominating Panel, which

nominates members to the Philadelphia School Board.

After a hearing on the merits on August 25th and

September 7, 1971, and a complete study of the applicable

law and the briefs of the parties, we make the following:

FINDINGS OF FACT

1. It is stipulated that the population ot the uity oi

Philadelphia is 1,948,609, of whom 653,791 are black.

2. In the 1970-1971 school year, the public school

population of the City of Philadelphia was 60.5% black.

3. In the 1970-1971 school year, the public elementary

school population of Philadelphia was 60.2% black.

31

4. In the 1970-1971 school year, the public junior

high school and middle school population of Philadelphia

was 65% black.

5. In the 1970-1971 school year, the public senior

high school population of Philadelphia was 56.2% black.

6. In the 1970-1971 school year, the public vocational

school population of Philadelphia was 59.9%.

7. In 1968-69, 42%, or 116 of the 279 schools in the

public school systems, had enrollments of over 95% black

or over 95% white; in 1970-71, 49%, or 139, of the schools

had over 95% one-race enrollments.

8. In 1968-69, 90,105 black students, 54.1% of said

students, were in schools with over 95% black enrollment;

in 1970-71 the number had increased to 96,014, or 56.7%.

9. The Educational Nominating Panel was set up by

the Educational Supplement to the Home Rule Charter, for

the purpose of screening applications for school board ap

pointments and nominating three individuals for each

vacancy on the School Board for the Mayor s consideration.

10. The Educational Nominating Panel consits of 13

members, 9 of whom are appointed to fulfill certain

classifications set out in the Section 12-206 of the Edu

cational Supplement and four (4) are at-large appoint

ments.

11. In 1965 the first panel was appointed with ten

(10) white and three (3) black members.

12. In 1967 the second panel was appointed with

eleven (11) white and two (2) black members.

13. In 1969 the third panel was appointed with twelve

(12) white and one (1) black members.

14. In 1971 the fourth panel was appointed with

eleven (11) white and two (2) black members.

15. The first list of nominees submitted to the Mayor

in 1971 consisted of five (5) whites and four (4) blacks for

the three (3) vacancies on the school board.

16. There are several organizations reflecting the

views and participation of the black community which

could qualify under subsections 1, 2. 3, 4, 5. 6 and 9 of

Section 12-206(,b). (7 of the 9 enumerated classes.)

32

17. The person assigned by the Mayor of Phila

delphia to choose the groups under the enumerated cate

gories, Deputy Mayor Anthony Zecca, at the time of the

hearing in the instant case was unaware of the existence

of many of these black organizations.

18. Of fifty-six appointments to non-civil service

positions with salaries in excess of $20,000 who are

presently serving, five of these, or 9% of the total, were

black.

19. The Mayor has made three hundred eighty eight

(388) appointments to Boards, Authorities and Commis

sions, who are presently serving, of whom forty-seven (47)

or twelve (12) percent were black.

20. The Board of Education has two (2) blacks of the

total membership of nine (9), or twenty-two (22) percent.

21. Although the Charter provides that the chief

executive of the organizations enumerated in §12-206(b)

of the Educational Supplement be appointed to the panel,

persons other than chief executives have been appointed.

DISCUSSION

Plaintiffs brought this class action under 42 U.S.C.

§1983 seeking declaratory and injunctive relief to end

alleged racial discrimination in the appointment of

members to the Educational Nominating Panel pursuant

to the provisions of the Educational Supplement of the

Philadelphia Home Rule Charter (hereinafter referred to

as the Educational Supplement). More specifically, plain

tiffs allege violations of the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, the Pennsylvania Human Rela

tions Act, and the express provisions and intended purpose

of the Educational Supplement, in that Mayor Tate sys

tematically excluded Negroes from said Educational

Nominating Panel.

Preliminary to reaching the merits of plaintiffs

claim, we must first ascertain whether plaintiffs should be

certified as a class pursuant to Rule 23 of the Federal Rules

33

of Civil Procedure. It is clear that a class consisting of all

blacks in the City of Philadelphia meets all the require

ments of Rule 23(a) in that: “(1) the class is so numerous

that joinder of all members is impracticable” ; (2) there is

a complete identity on all issues of law and facts; (3) the

claims of the representative parties are identical to other

members of the class; and (4) there is competent represen

tation by the parties bringing the suit. Moreover, the class

clearly falls within the purview of Rule 23(b)(2), because

it alleges that defendant has acted on grounds which affect

all members of the class. Therefore, it is clear that the class

must be confirmed.

The Educational Nominating Panel is a thirteen-

member body appointed by the Mayor to screen applicants

for membership on the school board and nominate three

candidates for each current vacancy on the school board

(Section 12-207(b) of the Educational Supplement). Nine

(9) members of said Panel are required by Section 12-206(b)

of the Educational Supplement to be the highest ranking

officer of an enumerated city-wide organization or institu

tion described in detail in that section with the remaining

four (4) appointees chosen by the Mayor from the citizenry

at large to ensure adequate representation of the entire

community (Section 12-206(c)).

In deciding whether, in fact, racial discrimination was

practiced in Mayor Tate’s nominations to the panel plain

tiffs ask us to hold that a prima facie case of discrimination

can be made out by a mere showing that blacks comprise

a substantial portion of the population, that some blacks

are qualified to serve, and that few if any blacks have served

in the past. In urging this result plaintiffs rely on cases such

as Hernandez v. Texas, 374 U.S. 475 (1954), United States

v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School System, 406 F.2d

1086 (5th Cir. 1969), and Alabama v. United States, 304

F.2d 583 (5th Cir.), a ff’d. 371 U.S. 37 (1962). This Court

recognizes that this general rule has been applied in certain

types of cases. As was clearly stated by the Fifth Circuit in

United States r. Jefferson County Board of Education. 372

34

F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966); a ff’d on rehearing en banc, 380

F.2d 383 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied sub nom., Board of

Education of the City of Bessemer v. United States, 389

U.S. 840 (1967):

This Court has frequently relied on percentages

in jury exclusion cases. Where the percentage of

Negroes on the jury and jury venires is dispropor

tionately low, compared with the Negro population

of a county, a prima facie case is made for deliberate

discrimination against Negroes. Percentages have

been used in other civil rights cases. A similar infer

ence may be drawn in school desegregation cases,

when the number of Negroes attending school with

white children is manifestly out of line with the ratio

of Negro school children to white children in public

schools. Id. at 887.

However, this rule has been confined to voting rights,

employment, school desegregation and jury cases. E.g.,

Noiris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) (Juries); Alabama

v. United States, supra (voting); United States v. Green

wood Municipal Separate School District, supra (schools);

United States v. Hayes International Corp., 415 F.2d 1038

(5th Cir. 1969) (employment).1 No case has been called

to our attention in which this rule has been applied to an

elected chief executive in the exercise of his discretionary

1. One case, T u r n e r v . F o u c h e , s u p r a , has applied the per

centage rationale to a school board. However, that case is clearly

distinguishable from the instant case. In T u r n e r the body which

appointed the school board was a grand jury, which should have

been constituted from all eligible members of the community. The

absence of an appropriate number of blacks on the grand jury

raised the presumption of discrimination. Thus, in essence, T u r n e r

was a grand jury case. In the instant case, 9 of the appointments

were limited by law and all citizens are not eligible. Moreover,

unlike the situation in T u r n e r , the Educational Nominating Panel

does not have the authority to appoint Board members but rather

only has the authority to submit names to the Mayor. Thus, T u r n e r

is not controlling in this case.

35

appointive power. We do have reservations as to whether

the Courts have the authority to exercise control over the

chief executive in such circumstances; however, we need

not decide this question since the facts presented in the

instant case render use of this test unfeasible.

It is undisputed that sixty (60) percent of the Phila

delphia Public School population and thirty-three (33)

percent of the Philadelphia population is black. Plaintiffs

contend that the 60% figure should be used in determining

whether there has been discrimination in appointments

to the panel. With this reasoning, we do not concur. The

standard when using a percentage rationale to establish

a prima facie case of discrimination has always been the

number of blacks qualified to fill the jobs in which the

alleged discrimination is taking place. E.g., Turner v.

Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970); Hernandez v. Texas, supra.

In the instant case that figure would depend on the adult

population of Philadelphia, which is approximately 33%.

Mayor Tate’s appointments to the Panel include two

blacks out of the thirteen appointees, or approximately

fifteen point four (15.4) percent of the panel. In its six-year

history, the panel has had from 1 to 3 blacks (8% to 23%).

With only thirteen members on the Educational Nominat

ing Panel, the addition or subtraction of one member of any

ethnic or racial group results in a change of eight (8) percent

in that group’s representation. In this Court’s opinion,

such wide fluctuations based on small numerical changes

in membership on the Panel result from the limited size

of the Panel and render such statistics meaningless as an

indicator of racial discrimination. Furthermore, in the cases

wherein the percentage rationale has been adopted, there

were a large number of blacks within the population

eligible for a large number of positions. This is not the

situation in the instant case where a small board is involved,

and we cannot find that the absence of additional blacks

from a thirteen-member panel proves discrimination.

Plaintiffs rely heavily on the fact that only 8.9%

(5 of 56) of Mayor Tate’s appointments for positions with

36

salaries in excess of $20,000 have been black. Plaintiffs

admit that this fact has no direct bearing on the issues

before us, but state that it is relevant to show a pattern of

discrimination. However, no case has been presented to

us, nor does our research disclose any case, in which a per

centage rationale has been used to prove job discrimina

tion without a finding that those allegedly being excluded

could qualify for those jobs in roughly the same ratio as

they appear in the population. Since no evidence was

presented, we cannot assume the percentage who could

qualify for such positions. Therefore, the aforesaid statistic

is not meaningful, and we do not have to determine

whether it is relevant in making a determination on the

issue of racial discrimination.

Since the facts of the instant case do not lend them

selves to the percentage rationale, plaintiffs must show

discrimination by direct proof. The only direct proof of

fered by the plaintiffs was a newspaper article allegedly

quoting Mayor Tate to the effect that he would not appoint

any more blacks to the Board of Education. However, since

said newspaper article is inadmissible hearsay, there is

[no direct proof of discrimination in this record.]

Further, plaintiffs would have us construe Section

12-206(c) of the Educational Supplement to hold that the

phrase “representative of the community” refers to racial

balance. However, the interpretation of this statute would

more properly be decided by the State courts, and we take

no position thereto. Similarly, while it is clear that the

Mayor has not appointed the chief executive officer of the

various organizations selected for representation on the

Panel as required by the Educational Supplement, such

violations have no bearing on the charges of racial dis

crimination and should also be decided by the State courts.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. This Court has jurisdiction of this case under

28 U.S.C. 1343 (3).

37

2. This action is properly maintainable as a class

action on behalf of black students and parents, on behalf

of black organizations which qualify for membership on the

Educational Nominating Panel, and on behalf of all black

citizens of Philadelphia.

3. The fact that there have been alleged violations of

the Charter in appointments to the Educational Nominat

ing Panel, such as the failure to appoint chief executives

of organizations to the Panel and failing to appoint at-large

members to adequately represent the entire community,

are not relevant in determining whether racial discrim

ination was involved with the appointments and such

issues should be litigated in the State courts.

4. In the context of the facts found by this Court, the

percentage rationale cannot be used to establish a prima

facie case of racial discrimination by defendant in viola

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment in the appointment of

members to the Educational Nominating Panel.

5. The plaintiffs failed to prove that the Educational

Nominating Panel was appointed in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

6. Plaintiffs’ complaint is, therefore, dismissed with

prejudice.

Accordingly, the following Order is entered:

ORDER

AND NOW, to wit, this 8th day of November 1971,

it is hereby ORDERED AND DECREED that the complaint

in the above-captioned matter is dismissed with prejudice.

38

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F o r t h e T h i r d C i r c u i t

No. 71-2042

EDUCATIONAL EQUALITY LEAGUE, FLOYD L. LOGAN,

W. WILSON GOODE, VERONICA KELLAM, by her

mother and next friend, ELIZABETH KELLAM, and

MICHAEL GREEN, by his father and next friend,

COOLIDGE GREEN on behalf of themselves and

all others similarly situated

Appellants

v.

HONORABLE JAMES H. J. TATE, Mayor of the

City of Philadelphia, and

THE EDUCATIONAL NOMINATING PANEL

(D. C. Civil Action No. 71-1938)

A p p e a l F r o m t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s D i s t r i c t C o u r t

F o r t h e E a s t e r n D i s t r i c t o f P e n n s y l v a n ia

Argued December 5, 1972

Before V a n D u s e n , G ib b o n s a n d H u n t e r ,

Circuit Judges

EDWIN D. WOLF, ESQ.

of Lawyers’ Committee

for Civil Rights under Law,

Attorney for Appellants

LEVY ANDERSON, ESQ.

City Solicitor

39

JOHN MATTIONI

Deputy Citv Solicitor

HOWARD D. SCHER

Assistant City Solicitor

Attorneys for Appellees

OPINION OF THE COURT

(Filed January 11, 1973)

V an D usen, Circuit Judge.

Plaintiffs instituted their class action under 42 U.S.C.

§1983 (1970) in August 1971 against the Honorable James

11. J. Tate (“Mayor”), then Mayor of Philadelphia, and the

Educational Nominating Panel (“Panel”).1 They alleged

that the Panel had been appointed in a racially discrimina

tory manner. After considering the stipulated facts and the

testimony and exhibits both sides introduced, the district

court entered an order on November 8, 1971, dismissing

die action.1 2 From that order plaintiffs appeal. This court

has reviewed the applicable law, which now includes two

significant cases decided after the district court order,3

and has concluded that it is compelled to vacate the dis

trict court order and to direct the district court to grant

appropriate relief.4

1. Although defendants did not question the propriety of

suing the Panel under $1983, it would appear that the Panel is not

a “person” under this section and thus not liable to such a suit.

See U n i t e d S ta te s e x ret. G i t t l e m a c k e r v . C o u n t y o f P h i la d e lp h ia ,

413 F.2d 84 (3d Cir. 1969). Consequently, the district court was

correct in dismissing plaintiffs’ complaint as to the Panel.

2. The district court opinion in support of this order is re

ported at 333 F. Supp. 1202 (E.D. Pa. 1971).

3. A l e x a n d e r v. L o u i s i a n a . 405 U.S. 625 (1972); and S m ith

v . Y e a g e r , 465 F.2d 272 (3d Cir. 1972), cer t , d e n i e d s u b n o m . N e w

J e r s e y v. S m i t h , 41 U.S.L.W. 3341 (U.S., Dec. 18, 1972).

4. The dismissal in favor of the Panel, however, will be af

firmed. See note 1, su p ra .

40

The Educational Supplement of the Philadelphia

Home Rule Charter (Educational Supplement) provides

that the mayor appoint the members of the Board of Edu

cation. The function of the Panel is to submit to the mayor

the names of persons best qualified to serve on the Board.

The Panel nominates three persons for each place on the

Board to be filled, and an additional three persons if the

mayor requests such additional names. The mayor must

choose solely from these nominees. See section 12-207(b)

of Educational Supplement. The Panel, which has thirteen

members, is itself chosen by the mayor. Nine members

must be the highest ranking officers of specified types of

city-wide organizations, and four are chosen at large.5

Each Panel serves two years, commencing at or before

May 25 of odd-numbered years.

5. Section 12-206(a)-(b) provides:

“(a) The Mayor shall appoint an Educational Nominating

Panel consisting of thirteen (13) members. Members of the

Panel shall be registered voters of the City and shall serve for

terms of two years from the dates of their appointment.

“(b) Nine members of the Educational Nominating Panel

shall be the highest ranking officers of City-wide organizations

or institutions which are, respectively: