Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Jeanette Wolfey (Native American Rights Fund)

Correspondence

April 20, 1987

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Jeanette Wolfey (Native American Rights Fund), 1987. ca8fbf8e-ea92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ea012954-eb52-4482-9944-3a3f5df936ee/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-jeanette-wolfey-native-american-rights-fund. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

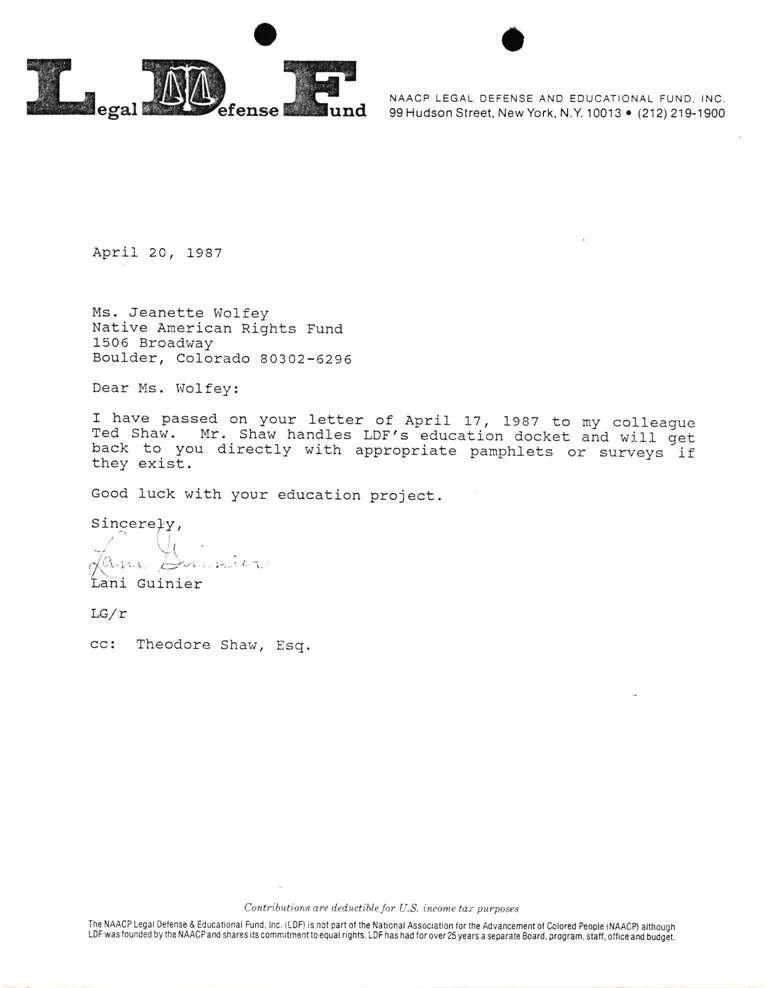

Lesar@renseH. NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. 1001 3 o (212) 219-1900

April 2C, t987

Ms. Jeanette Wolfey

Native Amerj"can Rights Fund

1506 Broadway

Boulder, Colorado 80302-6296

Dear Ms. Wolfey:

r have passed on your letter of Aprir t7, lggT to ny colleagueTed Shaw. Mr. Shaw handles LDF's education docket ana wj_Il 6"tb3ck to. you directly with appropriate pamphlets or surveys ifthey exist.

Good luck with your education project.

Sincerely,

,,,!

!:

\-(

l/f i'it i 3-i-' rr.1( -t-

Lani Guinier

LG/r

cc: Theodore Shaw, Esq.

Contrtbutions are deductible for ti,S. income tar p.urposes

The NAACP Legal Defense. & E-ducational Fund, lnc. (LDfl is not part of the National Association for the Advancement ol Colored People (NAACp) although

LDF was tounded by the NAACPand shares its commitment to equal rights. LDF has had for over 25 years a separate 8oard, program, statl, oflice anO OuOgit.