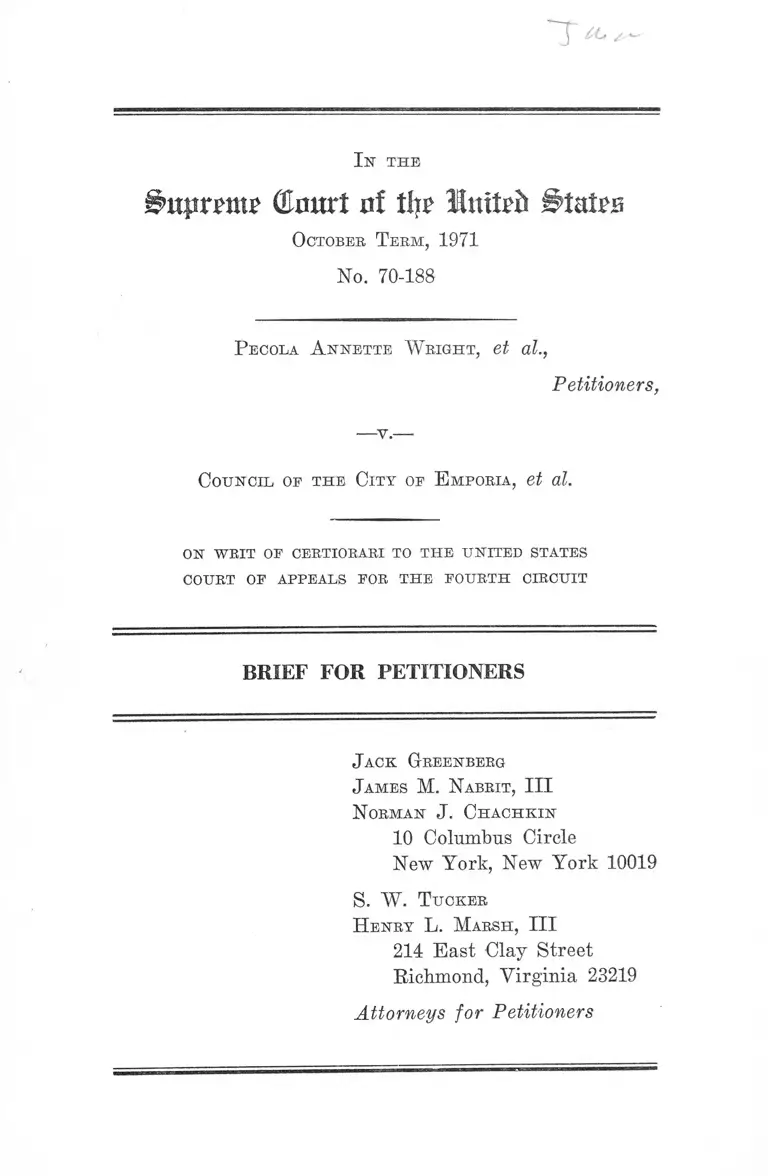

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia Brief for Petitioners, 1971. d68a0e91-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ea1165a8-30db-435e-ad4c-96ed10c3f217/wright-v-council-of-the-city-of-emporia-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

i>uprmp ©Hurt nf % lu it^ States

O ctober T erm , 1971

No. 70-188

P ecola A nnette W righ t , et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

C ouncil oe th e C it y oe E mporia , et al.

ON W R IT OP CERTIORARI TO T H E U N ITED STATES

COURT OE APPEALS FOR T H E F O U R TH CIRCU IT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

S. W. T ucker

H enry L. M arsh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Opinions Below ..... ......................... ............................. 1

Jurisdiction ....... 2

Question Presented .............................. 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved 2

Statement ......... 3

Background of the Litigation ..... ..... ............... 3

Emporia Moves to Operate a Separate System 8

The District Court’s Decision ........................... 18

The Court of Appeals’ Ruling ......... 25

Summary of Argument ....................................... 28

A egxjmen't :—

I. The District Court Properly Ignored

Newly Drawn Political Boundaries in

Framing a Remedial Decree to Disestab

lish School Segregation Which Had Been

Maintained Without Regard to the Same

Political Boundaries .................... 30

II. The “Primary Motive” Standard An

nounced by the Court Below Is 111 Con

ceived and 111 Suited to School Deseg

regation Cases ............................................ 37

PAGE

11

III. Even Were the Court of Appeals’ Stan

dard Acceptable, It Was Misapplied in

PAGE

This Case ...................................................... 46

Conclusion- ............................................................................... 55

B rief A p p e n d ix :'—

Excerpts from Virginia Code, Annotated....... App. 1

T able of A uthorities

Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19

(1969) .............. 39

Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ., 419 F.2d

1211 (5th Cir. 1969) ................ ..................................... 7n

Aytch v. Mitchell, 320 F. Supp. 1372 (E.D. Ark. 1971).... 41

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 325 F. Supp. 828

(E.D. Va. 1971) ......................................... 44n

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, Civ. No. 3353 (E.D.

Va., April 5, 1971) ................. 44n

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ; 349 U.S.

294 (1955) ......................................................................... 31

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F.2d 820 (4th Cir.

1970) ............................................................................... 30,54

Buckner v. County School Bd. of Greene County, 332

F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964) ..... 30n

Burleson v. County Bd. of Election Comm’rs of Jeffer

son County, 308 F. Supp. 352 (E.D. Ark.), aff’d per

curiam, 432 F.2d 1356 (8th Cir. 1970)...........35,36,39,41

City of Richmond v. County Board, 199 Va. 679, 101

S.E.2d 641 (1958) 4n

1X1

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Bock, 426 F.2d 1035

(8th Cir. 1970) ........................... , ....... ............................. 43

Colonial Heights v. Chesterfield County, 196 Ya. 155,

82 S.E.2d 566 (1954) ....................................................4n, 5n

Corbin v. County School Bd. of Pulaski County, 177

F.2d 924 (4th Cir. 1949) ................................................ 30n

Crisp v. County School Bd. of Pulaski County, 5 Race

Bel. L. Rep. 721 (W.D. Va. 1960) .............................. 30n

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) ...........39, 40

Goins v. County School Bd. of Grayson County, 186

F. Supp. 753 (W.D. Va. 1960), stay denied, 282 F.2d

343 (4th Cir. 1960) ........................................................ 30n

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960).......... 25,37,38

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683

(1963) .................. ............................................................ 43

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) ............... ...............................6, 26, 31, 32,42

Griffin v. Board of Supervisors of Prince Edward

County, 203 Va. 321, 124 S.E.2d 227 (1962) ........... . 33

Griffin v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward County,

377 U.S. 218 (1964) ........................................................ 33

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417 F.2d 801 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 904 (1969) ...................... 42

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier County, 410

F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969) ..............................................25,38

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier County, 429

F.2d 364 (8th Cir. 1970) ......... ...................................33, 45n

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th Cir.

1971)

PAGE

44

I V

PAGE

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1969)........... 44

Jenkins v. Township of Morris School D ist.,------ N.J.

------ , ------ A.2 d ------- (1971) ............ .............................. 42

Kennedy Park Homes Ass’n, Inc. v. City of Lacka

wanna, 436 F.2d 108 (2d Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401

U.S. 1010 (1971) ............................................ .......... ...... 43

Keyes v. School Hist. No. 1, Denver, 396 U.S. 1215

(1969) ............................................................................... 48

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., No. 30154 (5th Cir.,

June 29, 1971) ....... ............. ......... ................... 34, 36,40,46

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd., 446 F.2d 911, 444

F.2d 1400 (5th Cir. 1971) .............................................. 7n

Moses v. Washington Parish School Bd., Civ. No.

15973 (E.D. La., August 9, 1971) ............................... 7n

North Carolina State Bd. of Educ. v. Swann, 402 U.S.

43 (1971) ...... 34

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 397 U.S. 232

(1970) ............................................................................... 48

Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217 (1971) ..................... 40

Plaquemines Parish School Bd. v. United States, 415

F.2d 817 (5th Cir. 1969) ............................. 45n

Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S. 443 (1968) 33

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1963) ................... 43

School Bd. v. School Bd., 200 Va. 587, 106 S.E.2d 655

(1959) ............................................................................... 5n

School Bd. of Warren County v. Kilby, 259 F.2d 497

(4th Cir. 1958) ............................................................... 30n

y

Stout v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 403

(5th Cir. 1971) ............................................................. 34,41

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S.

1 (1971) ................................................................... 31,32,33

United States v. Board of Educ. of Lincoln County, 301

F. Supp. 1024 (S.D. Ga. 1969) ...................................... 7n

United States v. Board of Educ. of Webster County,

431 F.2d 59 (5th Cir. 1970) .................. ................. -.... 6n

United States v. Duke, 332 F.2d 759 (5th Cir. 1964)..... 33

United States v. Georgia, Civ. No. 12972 (N.D. Ga.,

Jan. 13, 1971) .................... ....... ...................................... 44n

United States v. Hinds County School Bd., 417 F.2d

852 (5th Cir. 1969) ................................... ....... .............. On

United States v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 395

U.S. 225 (1969) ................. ........................................ .... 33

United States v. Sunflower County School Dist., 430

F.2d 839 (5th Cir. 1970) .............. ......... ..... .................. 7n

United States v. Tunica County School Dist., 421 F.2d

1236 (5th Cir. 1970) ...................................................... 7n

Walker v. County School Bd. of Floyd County, 5 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 714 (W.D. Va. 1960) .............................. 30n

Wright v. County School Bd. of Greensville County,

252 F. Supp. 378 (E.D. Va. 1966) .............................. 4

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. §§2000d-l et seq.................................. 4

Va. Code Ann. §15.1-21 (Repl. 1964) ................ 4n

Va. Code Ann. §§15.1-978 et seq. (Repl. 1964) . 4n

Va. Code Ann. §§15.1-1003, -1004 (Repl. 1964) .. 5n

PAGE

VI

Ya. Code Ann. §15.1-1005 (Repl. 1964) .....................4n, 53

Va. Code Ann. §22-2 (Repl. 1969) ........ 4n

Va. Code Ann. §22-7 (Repl. 1969) .......... 5n

Va. Code Ann. §§22-30, -31, -32, -34, -36 (Repl. 1969) 4n

Va. Code Ann. §22-42 (Repl. 1969) ............................... 3n

Va. Code Ann. §22-43 (Repl. 1969) .......................... 3n, 53

Va. Code Ann. §22-80 (Repl. 1969) .............................. 4n

Va. Code Ann. §22-99 (Repl. 1969) .........................5n, 45n

Va. Code Ann. §§22-100.1, -100.2 (Repl. 1969) ........... 5n

Other Authority:

J. Ely, Legislative and Administrative Motivation in

Constitutional Law, 79 Yale L.J. 1205 (1970).......... 38n

PAGE

In t h e

(Hmtrt at tiĵ MnitTii States

O ctobeb T erm , 1971

No. 70-188

P ecola A nnette W righ t , et al.,

Petitioners,

-------- y . --------

Council oe the Cit y of E mporia, et al.

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E U N ITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR T H E FO U R TH CIRCU IT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

Tlie opinions of tlie courts below are as follows:

1. District Court’s Findings of Fact and Conclusions

of Law of August 8, 1969 and Order of August 8,1969

granting preliminary injunction, unreported (190a-

195a).1

2. District Court’s Opinion of March 2, 1970, reported

at 309 F. Supp. 671 (293-309a).

3. Court of Appeals’ Opinions of March 23, 1971, re

ported at 442 F.2d 570, 588 (311a-347a).

1 Citations are to the Single Appendix filed herein.

2

Earlier proceedings in the same case are reported as

Wright v. County School Bd. of Greensville County, 252

F. Supp. 378 (E.D. Va. 1966) (15a-28a).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

March 23, 1971. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1254(1). The petition for a writ

of certiorari was tiled in this Court on May 20, 1971, and

was granted on October 12, 1971,

Question Presented

Whether the Court of Appeals erred by holding that new

school districts may be operated which divide a unit that is

faced with the duty to desegregate a dual system, where the

changed boundaries result in less desegregation, and where

formerly the absence of such boundaries was instrumental

in promoting segregation.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This matter involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, which pro

vides as follows:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of

the United States and of the State wherein they re

side. No State shall make or enforce any law which

shall abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens

of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due process

3

of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction

the equal protection of the laws.

The following sections of the Virginia Code (statutes

related to the operation of school districts and divisions

within the Commonwealth of Virginia) are set out in an

appendix to this Brief, infra : Va. Code Ann. §§22-7, -30,

-34, -42, -43, -89, -99, -100.1, -100.2 (Repl. 1969).

Statement

Background of the Litigation

This lawsuit began with the filing of a Complaint on

March 15, 1965 seeking the desegregation of the public

schools of Greensville County, Virginia (2a-lla), a rural

county near the center of which was located the town of

Emporia (15a).2 As the district court found, “ [p]rior to

1965, the county operated segregated schools based on a

system of dual attendance areas. The white schools in

Emporia served all ivhite pupils in the county. The four

Negro elementary schools were geographically zoned, and

the Negro high school served all Negro pupils in the county”

(emphasis supplied) (15a). On January 27, 1966 the court

approved, subject to satisfactory amendment so as to pro

vide for faculty desegregation, a freedom-of-choice plan

2 Under Virginia law applicable at the time of the events relevant

hereto, the county was the basic operational school unit, Va. Code

Ann §22-42 (Repl. 1969). In 1965, when Emporia had the status,

under Virginia law, of a “ Town,” the County School Board of

Greensville County operated public schools for children residing

therein as well as in the rest of Greensville County. Although the

Town might have sought designation by the State Board of Educa

tion as a separate school district, either to obtain representation on

the county school board, see Va. Code Ann. §22-42 (Repl. 1969) or

to operate its own school system, Va. Code Ann. §22-43 (Repl.

1969), there is no indication in this record of any attempt to do so

while Emporia was a Town.

4

which the county had adopted in April, 1965 in order to

retain its eligibility for federal funds under Title V I of

the Civil Eights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000d-l et seq.

(16a). Wright v. County School Bd. of Greensville County,

252 F. Supp. 378 (E.D. Va. 1966).

On July 31, 1967, the Town of Emporia became a city of

the second class3 and a school board for the new city was

appointed.4 * On December 7, 1967, the State Board of Edu

cation designated Emporia and Greensville County a single

school division (245a).6 The schools continued to be oper

ated under the freedom-of-choice plan by the county school

hoard for both city and county children while discussions

between officials about ultimate school organization pro

3 See Va. Code Ann. §§15.1-978 et seq. (Repl. 1964). Unlike

towns, cities in Virginia are entities politically independent of the

counties which surround them, see City of Richmond v. County

Board, 199 Va. 679, 684, 101 S.E.2d 641, 644 (1958) ; Colonial

Heights v. Chesterfield County, 196 Va. 155, 82 S.E.2d 566 (1954),

and they may maintain duplicate institutions for the provision of

governmental services except for specified shared services, Va. Code

Ann. §15.1-1005 (Repl. 1964). Cooperative agreements between po

litical subdivisions are authorized, Va. Code Ann §15.1-21 (Reol

1964).

4 Va. Code Ann. §22-89 (Repl. 1969).

6 Virginia law provides that the State Board is ultimately re

sponsible for the administration of public free education in the

Commonwealth, Va. Code Ann. §22-2 (Repl. 1969) ; it was required

(at times pertinent to this case) to divide the State “into appropri

ate school divisions” of at least one county or city, each school

division to be administered by a superintendent of schools meeting

qualifications established by the State Board and exercising such

powers as were conferred by the State Board, Va. Code Ann. §§22-

30, -31, -36 (Repl. 1969). In a school division composed of more

than one political subdivision, the Division Superintendent serves

the school boards of each and, if separate school systems are being

maintained, administers each system (144a, 245a, 267a-269a). The

school boards of the independent political subdivisions constituting

a single school division must meet jointly to select a division super

intendent from the eligible candidates’ list approved by the State

Board of Education, Va. Code Ann. §§22-32, -34 (RepL 1969); see

also, 98a.

5

ceeded.6 Subsequently, on April 10, 1968, the school boards

and governing bodies of the city and county entered into a

four-year contract providing that the County would oper

ate public schools for city children in return for payment

by the City of a specified percentage of the capital and

operating cost (32a-36a).7

6 Virginia law provided that the city and county school hoards

might: subject to the approval of the State Board and local gov

erning bodies, establish joint schools, Va. Code Ann. §22-7 (Repl.

1969); operate separate school systems; establish a single school

board for the school division and operate as a single system, again

subject to the approval of the State Board and local governing

bodies, Va. Code Ann. §§22-100.1, -100.2 (Repl. 1969); or by con

tractual agreement the county might provide educational services

for city children, Va. Code Ann. §22-99 (Repl. 1969).

On November 27, 1967, the Greensville County Board of Super

visors had resolved that it would not approve joint operation (30a) ;

so long as this position was maintained, the city school board’s

remaining options were either an independent school system or

contractual agreement.

7 Because no settlement had yet been reached, the County Board

of Supervisors resolved on March 19, 1968 (31a) to terminate pro

vision to city residents of all but statutorily required services unless

a contractual agreement were accepted by the city by April 30.

Thus, the Mayor of Emporia and the Chairman of its School Board

testified in 1969, the contract was signed only under pressure

(233a) and only because the failure of the boards to agree on a

price for the schools located in the city prevented Emporia from

operating its own school system (119a). However, the city could

have filed suit in 1967, as it did in 1969 (237a, 242a) to establish

its equity in the schools had it desired to operate an independent

system, Va. Code Ann. §§15.1-1003, -1004 (Repl. 1964) ; Colonial

Heights v. Chesterfield County, 196 Va. 155, 82 S.E.2d 566 (1954) ;

School Bd. v. School Bd., 200 Va. 587, 106 S.E.2d 655 (1959).

Instead, it negotiated for preferred contractual terms (see 230a).

Both the Mayor and School Board chairman said they were satis

fied with the education provided city children by the county prior

to the June 25, 1969 district court order (163a, 235a), and, in

fact, the July 7, 1969 letter from the City Council to the County

Supervisors proposing an independent system recites that the city

signed the contract because of its judgment about educational bene

fits of a combined school system:

In 1967-68 when the then Town of Emporia, through its gov

erning body, elected to become a city of the second class, it

6

June 21, 1968, plaintiffs filed a Motion for Further Relief

consistent with this Court’s ruling in Green v. County

School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) (37a).

The district court directed the County School Board to

demonstrate its compliance with Green or to present a plan

to bring it into compliance (la [Docket Entries, p. 2]).

August 8, 1968, the board requested that freedom-of-choice

be continued for another year while a zoning or pairing

plan was developed (294a).* 8 The district court acquiesced

because of the short time remaining before the start of

the school year and because a new division superintendent

had just been hired (50a, 182a; see 98a) but required sub

mission of a new plan by January 20, 1969 (la, 294a).

Again the County School Board responded (38a-45a) by

asking that freedom of choice be continued.9 In the alter

native, the Board proposed: to establish different cur-

was the considered opinion of the Council that the educational

interest of Emporia citizens, their children and those of the

citizens and children of Greensville County, could best be

served by continuing a combined City-County school division,

thus giving students from loth political subdivisions full bene

fits of a larger school system (emphasis supplied) (56a).

8 The district court’s opinion sets forth enrollment statistics for

the 1967-68 school year which show that under freedom of choice,

no white students had elected to attend any of the five all-black

schools, while 96 of 2568 black students had chosen to enroll in

two predominantly white facilities (294a). Faculty desegregation

was minimal {ibid.).

9 The board asked to modify the outstanding decree (29a) as

follows (42a) : (1) Faculty and administrators would be per

mitted to encourage exercise of choices in favor of desegregation,

see United States v. Hinds County School Bd., 417 F.2d 852 (5th

Cir. 1969) ; (2) If substantial desegregation did not occur in this

manner, elementary children would be assigned to special classes

across raeial lines, see, e.g., United States v. Board of Educ. of

Webster County, 431 F.2d 59 (5th. Cir. 1970) ; (3) Course dupli

cation in the two high schools would be eliminated so as to bring

about attendance at both facilities; (4) At least 25% of the faculty

at each school would be of the minority race.

7

rieular programs—academic, vocational-technical, and ter

minal-degree—at each high school and to assign students

according to their curricular choice (43a),10 and to reassign

black elementary students to white elementary schools on

the basis of standardized achievement test scores.11

Following a hearing February 25, 1969, the district court

disapproved the request to continue freedom of choice and

took the board’s alternative proposal under advisement (la )

pending submission of enrollment projections under the

testing plan based on student scores (51a). On March 18,

1969, petitioners filed their own proposal to desegregate

the Greensville County schools by pairing (46a-47a). At

the conclusion of an evidentiary hearing on June 23, 1969,

the district court announced orally (49a-53a) that it would

disapprove the school board’s alternative plan because it

would “ substitute a segregated—one segregated system for

another segregated school system and that is all it is” (51a).

The court directed implementation of the plan proposed

by the plaintiffs:

The Court directs therefore that the proposed plan

of desegregation submitted by the plaintiffs is to be

put in effect and a mandatory injunction directing the

School Board to put that plan in effect commencing

September would be entered.

Now, the Court will consider any amendments to it

so as not to preclude a better plan, but so there is no

further delay and so we don’t come up in August and

10 See Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd., 446 F.2d 911, 444

F.2d 1400 (5th Cir. 1971).

11 See Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ., 419 F.2d 1211

(5th Cir. 1969) ; United States v. Sunflower County School Dist.,

430 F.2d 839 (5th Cir. 1970) ; United States v. Tunica County

School Dist., 421 F.2d 1236 (5th Cir. 1970) ; United States v.

Board of Educ. of Lincoln County, 301 F. Supp. 1024 (S.D. Ga.

1969) ; Moses v. Washington Parish School Bd., Civ. No. 15973

(E.D. La., August 9, 1971).

8

say, “Well, now, we have got a plan but can’t do it

for a year,” the School Board is directed today, now,

to commence their work to do whatever is necessary

to put in effect the plan for desegregation submitted

by the plaintiff. (53a)

June 25, 1969, a written order disapproving the board’s

plan and mandatorily enjoining implementation of the

pairing plan proposed by plaintiffs was entered (54a-55a).12

Emporia Moves to Operate a Separate System

On July 7, 1969—twelve days after entry of the district

court order requiring pairing of schools in Greensville

County—the City Council of Emporia wrote to the Greens

ville County Board of Supervisors and School Board (56a-

60a) formally announcing the City’s intention to operate

a school system separate from Greensville County effective

August 1, 1969 (57a). The Council proposed that the April

10, 1968 contract be terminated by mutual agreement (58a),

that a new contract be drafted to cover shared services

other than public schools, including a procedure to deter

mine the equity of the city and county in their school build

ings (59a-60a), and that pending such determinations, the

title to school buildings located within Emporia be trans

ferred to the City immediately so that its school system

could begin operation (60a). As part of its proposal, the

Emporia Council offered to accept county students on a

tuition basis in its separate school system (ibid.).

12 That order was subsequently modified in accordance with the

comments of the district court quoted next above. On July 23,

1969, the County School Board filed a motion to amend the June

25 judgment by substituting a different plan (76a-79a). A hear

ing was held July 30, 1969 at which yet another version of a

pairing plan was proposed by the County School Board and

adopted by the district court (162a, 174a, 295a).

9

The Council’s letter clearly indicated that the source of

its concern was the desegregation decree, rather than any

longstanding dissatisfaction with the county school system:

In 1967-68 when the Town of Emporia, through its

governing body, elected to become a city of the second

class, it was the considered opinion of the Council that

the educational interest of Emporia Citizens, their

children and those of the citizens and children of

Greensville County, could best be served by continuing

a combined City-County school division, thus giving

students from both political subdivisions full benefits

of a larger school system.

The Council was not totally unaware of a Federal Court

suit against Greensville County existing at that time,

regarding school pupil assignments, pupil attendance,

and etc., but they did not fully anticipate decision by

the court which would seriously jeopardise the scholas

tic standing and general quality of education affecting

City students attending the combined school system.

# # #

The pending Federal Court action, at the time of Em

poria’s transition from a town to a city, was finally

decided by the court on June 23, 1969. The resulting

order REQUIRES massive relocation of school classes,

excessive bussing of students and mixing of students

within grade levels with complete disregard of indi

vidual scholastic accomplishment or ability.

An in-depth study and analysis of the directed school

arrangement reflects a totally unacceptable situation to

the Citizens and City Council of the City of Emporia.

# * #

. . . In these preliminary meetings, the City expressed

a sincere need for an increase in its geographical

10

boundaries through extensive annexation in order to

provide an adequate tax basis to support an indepen

dent school system. The Council is of the opinion

annexation of portions of land beyond the City limits

is most desirable in the interest of the people involved

and the City. A careful preliminary study, including

all facets o f school operation and with particular

attention to objections raised by County Officials, has

been conducted and the facts indicate that it may be

feasible to operate a City School System without imme

diate annexation (emphasis supplied) (56a-58a).

The letter did not request that the County Board propose

any alternative desegregation plan to the district court.

July 9, 1969, a special City Council meeting was held,

which the Mayor announced was for the purpose of “ ‘estab

lishing a City School System’ ” (61a). The minutes reflect

that most of the meeting was held in executive session.

July 14, 1969, the City Council met again in special ses

sion; the minutes (62a-66a) reflect the purpose of the

meeting was “to take action on the establishment of a City

School System, to try and save a school system for the City

of Emporia and Greensville County” (emphasis supplied)

(62a). The Mayor is reported in the minutes to have said,

‘“ it’s ridiculous to move children from one end of the

County to the other end, and one school to another, to

satisfy the whims of a chosen few.’ He said, ‘The City

of Emporia and Greensville County are as one, we could

work together to save our school system ’ ” (emphasis sup

plied) (ibid.).

At the July 14 meeting, the City School Board chairman

reported the racial composition of each school under the

plan approved by the district court. After the Mayor

advised the Council that the County Supervisors had de-

11

dined to transfer school buildings within Emporia to the

city for fear of “placing themselves in contempt of the Fed

eral Court order” (63a), the Council discussed possible

termination of the contract by mutual agreement or annex

ation. The City School Board chairman told the Council

that if the City had title to the three school facilities lo

cated in Emporia, 500 county students could be accommo

dated in addition to city residents (64a~65a) ;1S and finally,

the Council voted unanimously to direct the City Attorney

to take the necessary steps to determine the city’s equity in

county holdings (including schools) (66a).

The County School Board met two days later and

reiterated that while it would appeal the district court’s

order and also seek to change the terms of the order, it

would not transfer facilities to Emporia or assist in the

creation of a separate system because

this Board believes that such action is not in the best

interest of the children of Greensville County. . . .

(67a-69a).

July 17, the Emporia City School Board met to adopt

a resolution requesting designation of Emporia as a

separate school division (70a-72a). Again, the resolution

demonstrates that the source of concern was the desegre

gation decree.13 14 A similar resolution was adopted by the

City Council on July 23, 1969 (73a-75a).

13 There were 728 white students residing in the county area

outside Emporia (304a).

14 W hereas it is the considered opinion of the Board that the

requirements under the decree of the Federal District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia in a suit to which the

County of Greensville is a party will result in a school system

under which the school children of the City of Emporia will

receive a grossly inadequate education; and

W hereas under the decree aforementioned, there will be sub

stantial overloading of certain school buildings and substan-

12

July 30, 1969, the City School Board adopted a plan

to hold registration for the 1969-70 school year August

4-8, 1969 although the State Board had not made any

ruling on the request for separate school division status

(80a-81a). The registration notice invited applications

from nonresidents on a tuition basis (82a).

At the July 30 meeting the city school board also in

structed its acting clerk to investigate the availability of

churches and vacant buildings for use should the City be

unsuccessful in obtaining title to the school buildings in

Emporia (81a).

On August 1, 1969, by leave of the district court (83a),

the petitioners herein filed a Supplemental Complaint

adding as defendants in the pending action, the City

Council of Emporia and the School Board of the City of

Emporia (84a-87a). The Supplemental Complaint alleged

that establishment of a separately operating school system

for the City of Emporia or the withholding by the City of

the monies due Greensville County pursuant to the con

tract would “frustrate the execution of this [District]

Court’s order and the efforts of the County School Board

of Greensville County to implement the above mentioned

plan [approved by the district court on July 30, 1969]

for the operation of the public school system which here

tofore has served children residing in the City of Emporia,”

and sought to restrain the City Council and School Board

from taking any acts which would interfere with execution

of the outstanding district court order (86a). On August 5,

tial underuse of other school buildings at an excessive cost to

both the County and the City, the cost of school transportation

will be exaggerated out of all need in that pupils will be

assigned to schools on a basis other than that of proximity

the City s contribution toward education will be substantially

increased without any additional benefit in education to its

children, . . . . (71a)

13

the Emporia School Board made “ assignments” of grades

1-7 to the Emporia Elementary School and grades 8-12

to the Emporia (Greensville County) High School, con

tingent upon those buildings being made available to the

City School Board for the 1969-70 school year (89a).

The matter came before the district court for hearing

upon petitioners’ prayer for a preliminary injunction on

August 8, 1969 (90a-189a). Various exhibits were in

troduced, including the minutes of the school board’s and

governing bodies’ meetings, and testimony was taken.

The Division Superintendent of Schools, who would be

responsible for administering a separate district unless

the State Board created a new school division, testified

that he had no plans to implement a separate district and

had met with the city school board only once, August 5,

1969 (92a, 98a-99a). He did have statistics showing that

the total student population in the combined system was,

he said, approximately 63% black, while the city students

were approximately 50% black and county students about

70% black (109a).

The Mayor of Emporia stated that the City Council

had not discussed the establishment of a separate city

school system at any of its meetings prior to July, 1969

(118a) nor had the Council or the City School Board

attempted to intervene in this litigation to present their

views (128a). Despite what he referred to as eight years

of antagonism between Emporia and Greensville County

(159a), he said the City had been satisfied with the County’s

school operation prior to the district court’s decree (163a).

The June 25 order precipitated the desire to operate a

city system because of white flight which was anticipated

in response to the decree (121a-122a, 167a). He said he

had doubts about the willingness and ability of the County

14

to make the unitary system work effectively (135a) and

“ that in order to have a well-functioning working unitary

system in the heart of southside Virginia that it will take

the leadership of the city government and of the leading

city members . . (123a). It was the City’s desire, he

said, to afford city students an education superior to that

which they would receive in the county schools operated

pursuant to the desegregation decree (124a) but he was

also aware that the racial composition of the city school

system would be about 50-50 (126a) and as well that the

buildings which the city school board hoped to acquire

from the county were the formerly white schools, still

predominantly white in 1968-69 (116a).15

Edward Lankford, Chairman of the Emporia School

Board, testified that his board met officially only to select

a division superintendent with the Greensville County

Board, but otherwise had “nothing to do with the county

system” even while the contract was in force (140a, 145a).

He said the City Board had been dissatisfied with the

contract from its inception although they had not acted

(147a) until the desegregation decree requiring attendance

at several different schools during the twelve grades of

a child’s education was entered (148a). He agreed with

the Mayor that successful operation of a unitary system

required leadership which in his opinion the city could

provide but the county could not (153a), and he said there

was a “definite possibility” that city residents would be

willing to pay higher taxes to support their own school

system (154a).

16 The 1968-69 enrollment statistics can be found in the district

court’s opinion (298a) 98 of 2510 black students attended two

white schools while again, no white students enrolled in five all

black schools. See n.8 supra.

15

Mr. Lankford was aware that creation of an independent

city system wonld increase the percentage of black stu

dents in the remaining county system and reduce the

percentage of black students to which city students would

be exposed (143a). He discussed the adverse effects of

separate systems:

The Court: And it is going to have a deleterious

effect on the students of Greensville County because

you are going to take some of their superintendents

and he will be responsible to two Boards and take

buildings that they have been using, isn’t that

correct?

The Witness: That is correct

* # #

The Court: As a matter of fact it is going to

change the racial composition of the student popula

tion of Greensville County, which let’s call it what

it is, that is one of the problems in segregating

schools, isn’t it?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

* # *

By Mr. Warriner:

Q. Now, I want to know, sir, what adverse effect,

what adverse effect are you talking about when you

say that there would be an adverse effect on the

county? A. I don’t know that I could answer that.

The question to which I answered that this would be

an adverse effect I would like to have repeated if

possible.

Q. It can be repeated. The Judge asked you whether

it would have an adverse effect or a detrimental effect

and you agreed with him. I want to know what are

the adverse effects? A. Well, as you have pointed

16

out if the county has a surplus of school teachers

and these teachers are willing to terminate their con

tract to come to the city then there would he no

adverse effect insofar as teachers are concerned.

If the county has a surplus of buildings and the

buildings are no longer needed by the county and the

city is willing to assume those buildings, that is no

adverse effect.

Q. Leaving out the ifs, will the county have a sur

plus of teachers and will the county have a surplus

of buildings? A. In my opinion, yes, sir.

Q. All right, sir.

Then you would have no adverse effect on the

county? A. No, sir.

# # #

Q. I want you to, if there is anything that is un-

neighborly to the County of Greensville, I want you to

state it. A. The only adverse effect as ashed by His

Honor, the Judge, would be the racial ratio remain

ing in the county. (149a, 151a-152a) (emphasis sup

plied)

At the conclusion of the hearing, the district judge

announced that he would grant the injunction. The court

noted that although a year passed between the filing of the

motion for further relief and the entry of a decree, the

City Council and School Board made no attempts to com

municate their wishes to the County officials or to the

Division Superintendent (181a-182a). Following its June

25 order, the court noted, the Mayor expressed his dis

approval to the City Council and after being informed

of the expected Negro enrollments at each school under

the court-ordered plan, it was determined to establish an

independent city system. (183a). However, the court found

that creation of a new entity would not only interfere with

17

and disrupt execution of the plan already ordered but

would be unconstitutional (183a) :

Under the New Kent decision this School Board had

an obligation and a duty to take steps to see to it that

a unitary system was entered into. All they have done

up until now, and the Court is satisfied that while

their motives may be pure, and it may be that they

sincerely feel they can give a better education to the

children of Emporia, they also have considered the

racial balance which would be roughly 50-50 which

which reduce the number of white students to, under

the present plan, would attend the schools as presently

being operated.

The Court finds that under Brown v. Board of Educa

tion 349 U.S. 294 that these defendants, all of them,

have an obligation that they are going to abide by.

In short, gentlemen, I might as well say what I think

it is. It is a plan to thwart the integration of schools.

This Court is not going to sit idly by and permit it.

I am going to look at any further action very, very

carefully. I don’t mind telling you that I would be

much more impressed with the motives of these de

fendants had I found out they had been attempting

to meet with the School Board of Greensville County

to discuss the formation of a plan for the past year.

I am not impressed when it doesn’t happen until they

have reported to them the percentage of Negroes that

will be in each school.

■V- 42? 4f.W W W

. . . The Court will be delighted to entertain motions

for amendment of the plan at any time (184a-185a).

The same day the district court entered formal Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law (190a-194a) as well as a

18

temporary injunction restraining “any action which would

interfere in any manner whatsoever with the implementa

tion of the Court’s order heretofore entered in reference

to the operation of public schools for the student popula

tion of Greensville County and the City of Emporia”

(195a).

The District Court's Decision

Respondents declined to appeal from the decision grant

ing a preliminary injunction, seeking instead to make a

more extensive record (187a).

Pursuant to the injunction, schools in Emporia and

Greensville County opened for 1969-70 in accordance with

the district court’s June 30, 1969 order. The State Board

of Education at its August 19-20, 1969 meeting, tabled

Emporia’s request for designation as a separate school

division “ ‘ . . . in light of matters pending in the federal

court’ ” (198a). The minutes of the State Board meeting

note that “ [t]he Greensville County school board has

passed and submitted a resolution opposing the dissolu

tion of the present school division consisting of the county

and the city. . . .” (ibid.).

On December 3, 1969, the Emporia School Board

adopted a proposed 1970-71 budget prepared at its request

by the former Superintendent of Schools of Richmond,

Virginia (200a-201a). The budget is extensive and ex

pensive, proposing numerous supplementary services

(202a-223a). On December 10, 1969, the school board was

informed that the City Council had accepted the budget

(224a), and it proposed a desegregation plan for sub

mission to the district court assigning grades 1-6 to the

former Emporia Elementary School and grades 7-12 to

the former Greensville County High School (225a). The

19

hearing on permanent relief was held December 18, 1969

(226a-292a).

Much of the City’s evidence was repetitive of the earlier

hearing. Mr. Lankford testified again that the city was

dissatisfied with the contractual arrangements because it

had no control over such matters as hiring, salaries or

curriculum (242a). He said he had been satisfied with the

education afforded city students by the county prior to

the pairing order (235a) but that order required additional

transportation expenditures and he feared the County

School Board would be unwilling to raise the additional

revenues (236a).

Emporia’s Mayor also repeated his opinions that the

county would not adequately support a unitary school

system but the city would (289a-290a) and that without

the creation of a separate system the city would lose white

students to private schools during the 1970-71 school year

(291a).

However, armed with the detailed budget developed and

adopted after the district court’s temporary injunction

had been entered, both witnesses stressed that the city

desired to operate an educational system superior to that

which the county would provide. The City also presented

the testimony of a Professor of Education, Dr. Neil Tracey,

in support of this claim.

Dr. Tracey testified that it was his “understanding”

that he was not serving the City in “ any attempt to

resegregate or to avoid desegregation” (269a). He com

pared the educational programs of Greensville County

with those proposed by the Emporia School Board’s 1970-

71 budget without reference to the racial composition

of the two systems because, he said,

20

. . . my basic contention is and has been, that elimina

tion of the effects of segregation must be an educa

tional solution to the problem and that no particular

pattern of mixing has in and of itself, has any desir

able effect. . . . The problem is to permit the Negro

child to integrate into society both in terms of general

social problems and in terms of economic patterns. . . .

(emphasis supplied) (270a).

Dr. Tracey preferred the Emporia budget because, he said,

the county educational program did not include the kind

of supplemental, supportive projects he thought were

required to make integration work. He did not feel the

county’s school budget was high enough, for example

(274a). However, he did recognize problems which might

be created by separation: Emporia could draw the better

county teachers off (281a); the range of exposure afforded

the isolated, rural children in the county would be nar

rowed (284). In fact, Dr. Tracey concluded that if the

county were to support what he considered an adequate

educational program, he would favor continuation of the

consolidated unit (285a).

In a careful opinion issued March 2, 1970 (293a-309a),

the district court weighed the competing claims. The court

noted that petitioners’ supplemental complaint sought

relief in the nature of an injunction against third parties

to protect the court’s decree, and that after issuance of the

temporary injunction the City had answered the Supple

mental Complaint (196a-197a) “denying the allegation that

the plan for separation would frustrate the efforts of the

Greensville County School Board to implement the plan

embraced by the Court’s order” (293a, 299a). Since, ob

viously, the City’s plan to operate a separate school system

for city residents would prevent execution of the plan

21

which had been ordered, the court pointed out that the

issue before it was not solely the plaintiffs’ right to relief

protecting the earlier decree:

. . . at the December 18th hearing [, i]ssues explored

went beyond the question whether the city’s initiation

of its own system would necessarily clash with the

administration of the existing pairing plan; indeed,

there seems to be no real dispute that this is so. The

parties went on to litigate the merits of the city’s

plan, developing the facts in detail with the help of an

expert educator. Counsel for the city stated that “ at

the conclusion of the evidence today, we will ask Your

Honor to approve the assignment plan for the 1970-71

school year and to dissolve the injunction now, against

the city, effective at the end of this school year,”

Tr., Dec. 18, at 11 (298a-299a).

The district court concluded that the respondents had

standing to seek amendment of the July 30 decree (299a-

303a) and proceeded to the merits of the assignment plan

proposed by the City.

The court described the grade assignments, noting that

the City expected enrollments 10% above the number of

city residents enrolled in the combined system during

1969-70 because “ ‘some pupils now attending other schools

would return to a city-operated school system’ ” (206a,

297a).16 The district judge found that the budget for the

city system “clearly contemplates a superior quality educa

tional program” requiring “higher tax payments by city

residents” (297a) ; however, the court also remarked upon

the difficulties which would arise with the establishment

of two separate systems serving Greensville County and

16 The City did not now propose to accept county students on a

tuition basis without approval of the district court (225a).

22

Emporia: a “substantial shift in the racial balance,”' a

city high school of less than optimum size, isolation of rural

county students from exposure to urban society, disrup

tion of teaching staff, and withdrawal of city leadership

from the county’s educational program.17 The district

17 The establishment of separate systems would plainly cause a

substantial shift in the racial balance. The two schools in the

city, formerly all-white schools, would have about a 50-50

racial makeup, while the formerly all-Negro schools located in

the county which, under the city’s plan, would constitute the

county system, would overall have about three Negro students

to each white. As mentioned before, the city anticipates as

well that a number of students would return to city system

from private schools. These may be assumed to be white, and

such returnees would accentuate the shift in proportions.

* * * #

The impact of separation in the county would likewise be

substantial. . . . At each level the proportion of white pupils

falls by about four to seven percent; at the high school level

the drop is much sharper still.

In Dr. Tracey’s opinion the city’s projected budget, including

higher salaries for teachers, a lower pupil-teacher ratio, kinder

garten, ungraded primary schooling, added health services,

and vocational education, will provide a substantially superior

school system. He stated that the smaller city system would

not allow a high school of optimum size, however. Moreover,

the division of the existing system would cut off county pupils

from exposure to a somewhat more urban society. In his opin

ion as an educator, given community support for the pro

grams he envisioned, it would be more desirable to apply them

throughout the existing system than in the city alone.

While the city has represented to the Court that in the opera

tion of any separate school system they would not seek to hire

members of the teaching staff now teaching in the county

schools, the Court does find as a fact that many of the system’s

school teachers live within the geographical boundaries of the

city of Emporia. Any separate school system would undoubt

edly have some effect on the teaching staffs of the present

system.

* # #

The inevitable consequence of the withdrawal of the city from

the existing system would be a substantial increase in the pro-

23

court concluded that it should resolve the matter by ap

proving the plan most likely to bring about the successful

dismantling of the dual school system in Greensville

County and Emporia:

. . . This is not to say that the division of existing

school administrative areas, while under desegregation

decree, is impermissible. But this Court must with

hold approval “ if it cannot be shown that such a

plan will further rather than delay conversion to a

unitary, nonracial, nondiscriminatory school system,”

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, supra, 391 U.S.

459, 88 S.Ct. 1705. As a court of equity charged with

the duty of continuing jurisdiction to the end that there

is achieved a successful dismantling of a legally im

posed dual system, this Court cannot approve the pro

posed change. (308a).* 18

portion of whites in the schools attended by city residents, and

a concomitant decrease in the county schools. The county offi

cials, according to testimony which they have permitted to

stand unrebutted, do not embrace the court-ordered unitary

plan with enthusiasm. If secession occurs now, some 1,888

Negro county residents must look to this system alone for

their education, while it may be anticipated that the propor

tion of whites in county schools may drop off as those who can

register in private academies. This Court is most concerned

about the possible adverse impact of secession on the effort,

under Court direction, to provide a unitary system to the

entire class of plaintiffs (304a-306a, 308a).

18. . . Assuming arguendo, however, that the conclusions afore

mentioned are valid, then it would appear that the Court

ought to be extremely cautious before permitting any steps

to be taken which would make the successful operation of the

unitary plan even more unlikely.

The Court does find as a fact that the desire of the city lead

ers, coupled with their obvious leadership ability, is and will

be an important facet in the successful operation of any court-

ordered plan.

^

24

While the district court discussed the possible motives of

the respondents, it held that the question of motive was

not controlling.19

If Emporia desires to operate a quality school system for city

students, it may still be able to do so if it presents a plan not

having such an impact upon the rest of the area now under

order. The contractual arrangement is ended, or soon will be.

Emporia may be able to arrive at a system of joint schools,

within Virginia law, giving the city more control over the

education its pupils receive. Perhaps, too, a separate system

might be devised which does not so prejudice the prospects

for unitary schools for county as well as city residents. This

Court is not without the power to modify the outstanding

decree, for good cause shown, if its prospective application

seems inequitable (emphasis supplied) (306a, 309a).

19 The motives of the city officials are, of course, mixed. . . .

* * *

Dr. Tracey testified that his studies concerning a possible sep

arate system were conducted on the understanding that it was

not the intent of the city people to “resegregate” or avoid

integration. The Court finds that, in a sense, race was a fac

tor in the city’s decision to secede. . . . Mr. Lankford stated

as well that city officials wanted a system which would attract

residents of Emporia and “hold the people in public school

education, rather than drive them into a private school * * *

Tr. Dec. 18, at 28.

# * #

This Court’s conclusion is buttressed by that of the district

court in Burleson v. County Board of Election Commissioners,

308 P. Supp. 352 (E.D. Ark., Jan. 22, 1970). There, a section

of a school district geographically separate from the main

portion of the district and populated principally by whites

was enjoined from seceding while desegregation was in prog

ress. The Court so ruled not principally because the section’s

withdrawal was unconstitutionally motivated, although the

Court did find that the possibility of a lower Negro popula

tion in the schools was “a powerful selling point,” Burleson

v. County Board of Election Commissioners, supra, 308 F.

Supp. 357. Rather, it held that separation was barred where

the impact on the remaining students’ rights to attend fully

integrated schools would be substantial, both due to the loss

of financial support and the loss of a substantial proportion of

white students. This is such a case (emphasis supplied) (305a-

309a).

25

The district court’s order of March 2 (310a) continued

in effect its injunction against interference with the prior

order and denied the City’s motion to modify the decree.

The Court of Appeals’ Ruling

The majority opinion for the Court of Appeals, reversing

the judgment of the district court (311a-319a) proceeded

from different premises. In the first part of the opinion

(311a-313a), the Court announces a general rule for de

termining* whether division of a school district under court

order to desegregate into two or more new entities is con

stitutionally permissible. The Court of Appeals refers to

this Court’s opinion striking down a racially gerrymandered

legislative district in Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339

(1960) and extracts the principle that the enactment there

was voided because of its discriminatory legislative pur

pose, which this Court inferred from the difference in racial

composition between the old and the new district. This

principle, says the majority, underlies school desegregation

decisions voiding an all-black Arkansas school district cre

ated in 1949, Raney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier

County, 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir, 1969) and prohibiting estab

lishment of a predominantly white “ splinter” school dis

trict in 1970, Burleson v. County Bd. of Election Comm’rs

of Jefferson County, 308 F. Supp. 352 (E.D. Ark.), aff’d per

curiam 432 F.2d 1356 (8th Cir. 1970).

In general, therefore, the Court holds that the permissi

bility of creating new districts from old ones depends upon

whether the “primary purpose . . . is to retain as much of

separation of the races as is possible” (313a). Where the

result justifies an inference of purpose, that is the end of

the matter. Where it does not, the courts are to look to

other evidence in forming their judgment of the “primary

purpose” for establishing new districts.

26

The Court of Appeals applies these principles to Emporia

in the second part of its opinion. It holds (without regard

to the district court’s finding of a “substantial shift, in racial

balance” [emphasis supplied] [304a]) that since “the sep

aration of the Emporia students would create a shift of the

racial balance in the remaining county unit of 6 per cent”

(316a), no inference of primary discriminatory purpose can

be drawn.

The majority notes other evidence that the primary

motive was not racial: the district court’s findings that

Emporia’s motives were mixed (racial and non-racial), Dr.

Tracey’s “understanding,” and Emporia’s “uncontradicted”

testimony (which the appellate court fails to note was re

jected by the district court as unsubstantiated opinion) that

the County would not raise sufficient revenues to properly

operate the system.

Noting the friction between city and county caused by

Virginia’s “unusual” political structure, the majority holds

that federal courts ought not interfere with state or local

determinations of what structures may best be adopted to

fund public education in the absence of “primary motive”

to discriminate (318a); thus, the Court of Appeals intimates

no review of the alternatives available to Emporia in de

ciding that creation of a separate city district is constitu

tional and was improperly enjoined.

Judge Winter dissented from the majority (336a-346a).

His opinion views the case (and its companions) as being

controlled by the principles enunciated in Green v. County

School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) (326a-

338a) placing a “heavy burden” upon state authorities who

seek to implement a desegregation plan “ less effective”

than another before the court. Specifically, Judge Winter

found ample support in the record for characterizing the

separate-district plan as less effective than the prior district

27

court order: the delay -which would have been occasioned

by the adoption of new plans in August, 1969; the substan

tial change of racial proportions (“ the creation of a sub

stantially whiter haven in the midst of a small and heavily

black area” ) ; and the effect on county black students of the

excision from their school system of a significant part of

the white population with whom they would have attended

classes.

Judge Winter would find that the City had failed to meet

its heavy burden to justify this less effective plan since its

evidence at best showed both educational advantages and

disadvantages flowing from the new scheme and revealed

both racial and nonracial motives behind its adoption (341a).

Judge Winter would reject the “primary motive” test and

affirm because of the adverse impact occasioned by creation

of new districts (346a).

Judge Sobeloff did not participate in the Emporia ease

because of illness, but in his dissent from a companion

case, joined by Judge Winter, he rejected the “primary

motive” test.

Judge Sobeloff scored the direction to district courts to

weigh the motives of state officials, noting that

resistant white enclaves will quickly learn how to struc

ture a proper record—shrill with protestations of good

intent, all consideration of racial factors muted beyond

the range of the court’s ears, [footnote omitted] (322a).

He suggested that these cases, like other equal protection

suits in which state action has a racially discernible effect,

were best considered by requiring the State to justify the

racially disparate treatment as being required by a com

pelling state interest (322a-327a). Finally, Judge Sobeloff

predicted the unworkability of the “primary motive” test:

2 8

If, as the majority directs, federal courts in this circuit

are to speculate about the interplay and the relative

influence of divers motives in the molding of separate

school districts out of an existing district, they will be

trapped in a quagmire of litigation. The doctrine

formulated by the court is ill-conceived, and surely will

impede and frustrate prospects for successful desegre

gation. Whites in counties heavily populated by blacks

will he encouraged to set up, under one guise or an

other, independent school districts in areas that are

or can be made predominantly white.

It is simply no answer to a charge of racial discrimina

tion to say that it is designed to achieve “quality edu

cation.” Where the effect of a new school district is

to create a sanctuary for white students, for which no

compelling and overriding justification can be offered,

the courts should perform their constitutional duty and

enjoin the plan, notwithstanding professed benign ob

jectives (335a-336a).

Summary of Argument

I

The district court had before it two alternatives to de

segregate a dual school system which had formerly served

students of both Greensville County and the City of Em

poria : one involving pairing of all the schools, and another

involving separation into a county district and a city district

of differing racial compositions, with the schools paired

within each system. The lower court concluded the racial

shift was “ substantial” and that splitting the unit would

have other adverse impact upon the county system, and

ordered operation as a single unit. This was a proper

remedial choice within the equitable discretion of the dis

trict court which should not have been overturned by the

Court of Appeals.

II

The Court of Appeals presumed that State power to

create new school districts was plenary, even where there

was some interference with federal court desegregation

decrees, unless the “primary motivation” was the preser

vation of segregation. That is the wrong test; it follows

neither from this Court’s school desegregation rulings nor

from other decisions interpreting the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and it is incapable

of rational application in the district courts.

III

Even if the determination of motive is a proper inquiry,

the Court of Appeals should have remanded the ease to

the district court, which had not been concerned with the

issue at the trial. The Court of Appeals’ own determina

tion of the “primary motivation” behind establishment of

a separate city school system cannot be supported by a

full examination of the record.

30

ARGUMENT

I.

The District Court Properly Ignored Newly Drawn

Political Boundaries in Framing a Remedial Decree to

Disestablish School Segregation Which Had Been Main

tained Without Regard to the Same Political Boundaries.

If this were a case involving but one school district,

which operated seven schools, and the district court had

rejected a student assignment plan under which the two

formerly white schools would be 50% white, and the five

formerly black schools would be 70% black, it would not

be before this Court. Compare Brunson v. Board of Trus

tees, 429 F.2d 820 (4th Cir. 1970). Here two school districts

are involved—the Greensville County district and the Em

poria City school district (which has existed only since

1967). From 1967 until 1969 that city school district re

mained a part of the county system for student assignment

purposes, and under the free choice plan white students

throughout the county traversed Emporia’s boundaries

daily to attend the white schools located in the city. We

submit that the district court correctly required that city

and county students continue to traverse those boundary

lines in order to attend classes in a fully integrated school

system.20

20 It is interesting to note that Virginia historically sent black

students across city or county lines in order to preserve segrega

tion. See Buckner v. County School Bd. of Greene County, 332

F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964) ; School Bd. of Warren County v. Kilby,

259 F.2d 497 (4th Cir. 1958) ; Goins v. County School Bd. of

Grayson County, 186 F. Supp. 753 (W.D. Va. 1960), stay denied,

282 F.2d 343 (4th Cir. 1960) ; Crisp v. County School Bd. of

Pulaski County, 5 Race Eel. L. Rep. 721 (W.D. Va. 1960) ; Walker

v. County School Bd. of Floyd County, 5 Race Rel. L, Rep. 714

(W.D. Va. 1960) ; Corbin v. County School Bd. of Pulaski County,

177 F.2d 924 (4th Cir. 1949).

31

Greensville County maintained rigid school segregation

for over a decade after this Court’s rulings in Brown v.

Board of Educ., 347 IT.S. 483 (1954), 349 U.S. 294 (1955).

From 1965 until 1969 the desegregation of its schools was

token, under a freedom of choice plan. After Green v.

County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430

(1968) the county was ordered to develop a plan to

effectively desegregate its schools, but instead it postponed

the disestablishment of the dual school system for yet

another year by repeatedly requesting delays and by

proposing various stratagems to preserve segregation.

Finally, in the summer of 1969 the district court ordered

complete desegregation by pairing.

Only then, and without even so much as notice to the

district court, did Emporia officials seek to separate a city

school system from the rest of the county. Approximately

one month before the scheduled opening of classes, the

district court heard city officials who had no buildings,

no specific plans for school operation, and no teachers

under contract, insist that Emporia students should not

attend classes pursuant to the court’s order. The district

court enjoined interference with the order.

Emporia renewed its efforts toward creation of a city

system the next school year; the district court concluded

that the attendance plan envisioned by the city would

create a substantial racial disproportion between schools

in the city and the county and would otherwise impede the

desegregation process. The court refused to modify its

earlier decree.

The district court’s treatment of city and county as a

combined school unit for purposes of its order was a

conscientious exercise of its equitable discretion in framing

a remedy for unconstitutional school segregation, of the

sort this Court approved in Swann v. Charlotte-MecMen-

32

burg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.8. 1 (1971). While that case had

not been decided at the time, Green v. County School Bd.

of New Kent County, supra, mandated federal district

courts to assess proposed school desegregation plans by

their efficacy, and to select that plan which offers to bring

about the greatest amount of desegregation unless there

were very compelling reasons for preferring another:

Of course, where other, more promising courses of

action are open to the board, that may indicate a lack

of good faith; and at the least it places a heavy burden

upon the board to explain its preference for an ap

parently less effective method.

391 U.S. at 439 (emphasis supplied).

Here the district judge acted in accordance with the

principles of Green by rejecting the city’s scheme to place

a substantially greater percentage of white students in the

former white schools than in the former black schools.

As this Court said, 391 IJ.S. at 435:

The pattern of separate “white” and “Negro” schools

in the New Kent County school system established

under compulsion of state laws is precisely the pattern

of segregation to which Brown I and Brown 11 were

particularly addressed, and which Brown 1 declared

unconstitutionally denied Negro school children equal

protection of the laws, (emphasis supplied in part)

And cf. Swann, supra, 402 IJ.S. at 26: “ [T ]o assure a

school authority’s compliance with its constitutional duty

warrants a presumption against schools that are substan

tially disproportionate in their racial composition” (empha

sis supplied).21

21 The defect of the city school board’s plan was not that it failed

to achieve exact racial balance, Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 24, but

33

This Court has emphasized the breadth of the remedial

equitable discretion accorded district courts in school

desegregation cases. E.g., United States v. Montgomery

County Bd. of Educ., 395 U.S. 225 (1969); Swann v.

CJiarlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., supra. Swann re

jected a limitation of “ reasonableness” placed upon lower

court judges’ discretion by the Fourth Circuit. Here the

limit seems to turn upon the reviewing tribunal’s judgment

of substantiality. In both instances the appellate court

improperly restricted the ability of the district courts to

supervise the desegregation process, see Raney v. Board

of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S. 443, 449 (1968).

In cases involving the enforcement of constitutional

rights, federal courts are not bound to follow state laws

(and hence state law created boundary lines) in effectuat

ing adequate remedies. E.g., Haney v. County Bd. of Educ.

of Sevier County, 429 F.2d 364, 368 (8th Cir. 1970); United

States v. Duke, 332 F.2d 759 (5th Cir. 1964); compare

Griffin v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward County, 377

U.S. 218 (1964) with Griffin v. Board of Supervisors of

Prince Edward County, 203 Va. 321, 124 S.E.2d 227 (1962).

The discretion of the district courts in enforcing the

constitutional rights of Negro schoolchildren must extend

to crossing state political boundary lines, especially where,

as here, the lines are of recent origin and were readily

bridged to maintain segregation. The Fifth and Eighth

Circuits have sustained such power.

that in this small system consisting of seven school buildings

clustered in or near Emporia (see 132a-133a), the traditional ra

cial identities of the schools would be maintained by the pattern

of student assignment; the racial identity of no school is elim

inated.

34

In Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., No. 30154 (5th

Cir., June 29, 1971) (slip op. at pp. 11-12) (S.A. lla-12a) :22

School district lines within a state are matters of

political convenience. It is unnecessary to decide

whether long-established and racially untainted bound

aries may be disregarded in dismantling school

segregation. New boundaries cannot be drawn where

they would result in less desegregation when formerly

the lack of a boundary was instrumental in promoting

segregation. Cf. Henry v. Clarks dale Municipal Sep

arate School District, 5 Cir. 1969, 409 F.2d 683, 688,

n. 10.

Oxford in the past sent its black students to County

Training. It cannot by drawing new boundaries dis

sociate itself from that school or the county system.

The Oxford schools, under the court-adopted plan,

supported by the city, would serve an area beyond the

city limit of Oxford. Thus, the schools of Oxford

would continue to be an integral part of the county

school system. The students and schools of Oxford,

therefore, must be considered for the purpose of this

case as a part of the Calhoun County School system,

(emphasis in original)

Another panel of the Fifth Circuit in Stout v. Jefferson

County Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 403, 404 (5th Cir. 1971) (S.A.

23a-24a), involving a brand new district, quoted this Court’s

decision in North Carolina State Bd. of Educ. v. Swann, 402

U.S. 43, 45 (1971), and held:

22----The decision has not yet been reported but it was reprinted

as an appendix to petitioners’ Supplemental Brief in Support of

Petition for Writ of Certiorari, and citations in the form “S.A.

------ •” are to that document.

35

. . [ I ] f a state-imposed limitation on a school

authority’s discretion operates to inhibit or obstruct

the operation of a unitary school system or impede

the disestablishing of a dual school system, it must

fall; state policy must give way when it operates

to hinder vindication of federal constitutional

guarantees,”

Likewise, where the formulation of splinter school

districts, albeit validity created under state law, have

te effect of thwarting the implementation of a unitary

school system, the district court may not, consistent

with the teachings of Swann v. Charlotte-Meclclenburg,

supra, recognize their creation, [footnotes omitted]

And in Burleson v. County Bd. of Election Comm’rs of

Jefferson County, 308 F. Supp. 352, 357 (E.D. Ark.), aff’d

per curiam 432 F.2d 1356 (8th Cir. 1970), the court held:

The Area residents do not want to move out of the