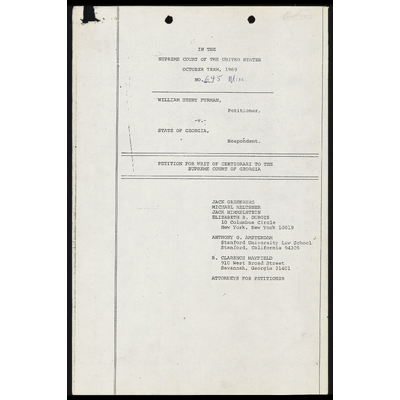

Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

Public Court Documents

1969

31 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Furman v. Georgia Hardbacks. Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia, 1969. 6f7d2a23-b225-f011-8c4e-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ea249574-3fcb-4d09-824d-182698443eb9/petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-georgia. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

w

i

d

e

n

is

L

L

LR

R

E

L

L

W

A

wi

d

Li

k

ms

i

it

al

BR

:

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

v.45 15 Ws se

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN,

Petitioner,

adh VANE

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

JACK GREENBERG

MICHAEL MELTSNER

JACK HIMMELSTEIN

ELIZABETH B. DUBOIS

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

B. CLARENCE MAYFIELD

910 West Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

ATTORNEYS FOR PETITIONER

or

INDEX

Citation to Opinions Below ——————m mmm

TUL LEALCELON =m oem oe eran om cr do ec ee ei ee se er me mt et me me ee

Questions Presented --—-—----- i a pm RE A . hR

‘Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved —-————=-

BBL ITTY ws seers sa 5 se Ge Se cm

How The Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided Below --

Argument

I The Court Below Has Misapplied The Standards

— QE Witherspoon V.~1llinois, -391-U.8..--510

(1968), And Has Thereby Condoned The Denial

To Petitioner Of A Fair Jury Trial On The

Issue Of The Death Sentence. —==—remmmcemmcmcnee—-

A. The Test Of Exclusion Applied By The Court

Below Did Not Meet The Minimum Standards

Required By The Constitution As Announced

“In Witherspoon. =—————cccmmmmrcm——m————— me

_B. The Court Below Erred In Approving Death

Qualification Practices, Whose Consti-

tutionality Raises The Question Expressly

Reserved In Witherspoon. =—-—--—=———ce—eeeceeee——

1 Georgia's Practice Of Allowing Capital Trial

Juries Absolute Discretion To Impose The

Death Penalty, Uncontrolled By Standards

Or Directions Of Any Kind, Violates The Due

Process Clause Of The Fourteenth Amendmzsnt. ----

IIT Petitioner's Death Sentence Constitutes Cruel

And Unusual Punishment In Violation Of The

Eighth And Fourteenth Amendments To The

Constitution Of The United States. ==—=—cemm——ee-

Conclusion ———=— mmm .

12

18

21

25

Ed

Page

Bell v. Patterson, 402 F.2d 394 (10th Cir. 1968) ----- 13

Boulden v. ‘Holman, 394 U.S. 478 (1963) ‘mmr sims ——— 9,12

Campbell v. State, Fla. 8, Ct. No. 35, 622 (6/11/69) ~~ 8

Daniels v. State, 35 S.E.2d 362 (Ga. 1945) ————mmemeem 20

Davis v. State, 440 S.W.2d 244 (Ark. 1969) ————mmmeme—em 8

Hicks v. State, 196 Ga. 671, 27 S.E.2d 307 (1943) —--—-- 20

McBurnett v. State, 206 Ga. 59, 55 S.E.2d 598 (1949)-- 19

Miller v. State, 224 Ga. 627, .163 S.E.2d4,730 (1968) -- 8

People v. Mallett, 244 N.E.2d 129 (111, 1969) =—mmemm- 8

People v. Speck, 41 111.24 177, 242 N.E.24 208

(I11. 1968) =——=—mm mmm em 8

Pittman v. State, 434 S.W.2d 352 (Tex. Cr. App. 1968)- 8,13

Scott v. State, 434 S.W.2d 678 (Tex. 1968) —-=—mm—m—ee- 8

Smith v, State, 437 S.W.2d4 835 (Tex. 1968) —-=—-mmeeee 8

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) —-mmmemeeme eee 16

State v. Aiken, 452 P.2d 232 (Wash. 1969) —-———ceeee- — 8

State v. Crook, 221 50.24 473 (La. 1969) ——~ce—am—mwmm—- 8

State v. Mathis, 52 N.J. 238, 245 A.2d 20 (1968) ---—-—- 8,13

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) —mmmemeeemcmme es ——— 22

Veney v. State, 345 A.2d 568 (Md. 1968) «——=—em=e—ae—a—- 8

Williams v. Dutton, 400 P.24 797 {5th Cir. 1968) === 8

Williams v. State, 46 S.E. 626 (1904) -wceecmcammaana=— . --20

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510

(1968) ——=—mmmm me 2,6,7,8,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17

STATUCTE?=

Federal:

20.8.0. GUIBT LT mene min iss iim so oe Be he ser ried me ein ee £2

ii

State:

Georgia Code Ann, §26+1001: (1953). ~——e=awwwmmwmmen wns 2,21

Georgia Code Ann. §26-1002 (1953) ~—m—memmmm————————— 2,21

deorata Code Ann. §26-1005 (1968 Supp.) '=em=m=—=—==ce- 3,18,21

Georgia Code Ann. §26-~1009 (1953) =wmmmmm—————- re mm 3,18,21

Georgia Code Ann. §27-2302 (1963 SUDD) ~r===mdwmmmimmm 3

Georgia Code Ann. §27-2512 (1953) —=—————mmmm mmm ———— 4

Georgia Code Ann, §$59-806.-(1965) ~—e=s=ammwmmeatne——n- 8

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Bedau, Death Sentences in New Jersey 1907-1960, 19 :

Rutgers L. Rev, 1, 9-11:{1964) —-—ew==mmmams==cen- 23

HARTUNG, TRENDS IN THE USE OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT, 284

ANNALS 8 (1952) =mmmmmm— eee mmm mmm mmm mm 23

MATTICK, "THE UNEXAMINED DEATH (1966)=—===——rm==neecn. 23

PRESIDENT 'S COMMISSION ON LAW ENFORCEMENT AND ADMINI-

STRATION OF JUSTICE, REPORT (The Challenge of Crime

in a Free Society) (1967) 143 w=-=maienmmumm mms mmm 23

Sellin, The Inevitable End of Capital Punishment, in

SELLIN, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT (1967) 239-240 23

U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, National

Prisoner Statistics, No. 42, EXECUTIONS 1930-1967

(June 1968) ——— meme me 23

ZIESEL, SOME DATA ON JUROR ATTITUDES TOWARDS CAPITAL

PUNISHMENT 7-8 (Center for Studies in Criminal Justice,

University of Chicago Law School, 1968) =m==eer=e 15

iii

-

in

R

E

B

R

SO

i

3

Ba

|

{

{

H

i

+

i

sg pee pe wa om

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITLD STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN,

Petitioner,

-.-

STATE OF GEORGIA, : 3

Respondent.

PETITION FOR BRIT OF CERTIORART TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of the State of Georgia entered

on April 24, 1969.

CITATION TO OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of the State of Georgia

is reported at 167 S.E. 2d 628 (1969) and is set out in

Appendix A hereto, pp. la-2a, infra.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Supreme Court of the State of Georgia

was entered on April 24, 1969 and is set out in Appendix B hereto,

P. 3a, infra. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.(.

§1257(3), petitioner having asserted below and asserting here

* deprivation of rights secured by the Constitution of the United

States.

‘ QUESTIONS PRESENTED

l. Whether a prospective juror was improperly excluded

from petitioner's jury in violation of the rule of Witherspoon

v. Xllinois, 391. U.8.-:510 (1968)7

2. Whether Georgia's practice of allowing capital trial

juries absolute disgretion to impose the, death penalty, uncon-

trolled by standards or directions of any kind, violates the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

3. - Whether punishment of death by electrocution pursuant

to provisions of Georgia law for the crime of murder constitutes

cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments?

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

l. This case. involves the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments

to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves the following provisions of

Georgia Code Annotated:

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1001(1953)

26-1001. (59 P.C.) Definition; kinds.-

Homicide is the killing of a human being,

and is of three kinds-murder, manslaughter,

and justifiable homicide. (Cobb, 783)

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1002 (1953)

26-1002. (60 P.C.) Murder defined.-Murder

is the unlawful killing of a human being,

in the peace of the State, by a person of

sound memory and discretion, with malice

aforethought, either express or implied.

® @

Ga.Code Ann. §26-1005(1968 Supp.)

26-1005. (63 P.C.) Punishment for murder:

recommendation by jury.-The punishment for

persons convicted of murder shall be death,

but may be confinement in the penitentiary

for life in the following cases: If the jury

trying the case shall so recommend, or if the

conviction is founded solely on circumstantial

testimony, the presiding judge may sentence to

confinement in the penitentiary for life. In

the former case it is not discretionary with

the judge; in the latter it is. When it is

- shown that a person convicted of murder had

not reached his 17th birthday at the time of- EE

the commission-of the offense, the punishment

of such person shall not be death but shall

~—be imprisonment for life.

Whenever a jury, in a capital case of homicide,

shall find a verdict of guilty, with a recommenda-

tion of mercy, instead of a recommendation of im-.

prisonment for life; in cases where by law the -—

jury may make such recommendation, such verdict-

shall be held to mean imprisonment for life. If,

in any capital case of homicide, the jury shall

make any recommendation, where not authorized

by law to make a recommendation of imprisonment

for life, the verdict shall be construed as if

made without any recommendation. (Cobb, 783.

Acts 1875, p. 106; 1878-9, p. 60; 1963, p. 122.)

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1009(1953)

26-1009. (67 P.C.) Involuntary manslaughter defined.

-Involuntary manslaughter shall consist in the

killing of a human being without any intention to

do so, but in the commission of an unlawful act, .or

a lawful act, which probably might produce such a

consequence, in an unlawful manner: Provided, that

where such involuntary killing shall happen in the

commission of an unlawful act which, in its conse-

quences, naturally tends to destroy the life of =

a human being, or is committed in the prosecution

of a riotous intent, or of a crime punishable by

death or confinement in the penitentiary, the

offense shall be deemed and adjudged to be murder.

{Cobh, 784).

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2302 (1968 Supp.)

27-2302. (1060 P.C.) Recommendation to mery .-

In all capital cases, other than those of homicide,

when the verdict is guilty, with a recommendation

to mercy, it shall be legal and shall mean imprison-

ment for life. When the verdict is guilty without

c

e

ie

bad

i

ROS

{

TO

RR

EY

3

NT

S

T

E

I

R

R

I

P

R

N

N

S

Y

0

OE

P

SP

U

a recommendation to mercy it shall be

legal and shall mean that the convicted

person shall be sentenced to death. However,

when 1t is shown that a person convicted of

a capital offense without a recommendation

to mercy had not reached his 17th birthday

at the time of the commission of the offense

the punishment of such person shall not be

death but shall be imprisonment for life.

{Acts 1875, pp. 106; 1963, Pp+ 122,123.)

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2512(1953)

27-2512. Electrocution substituted for

hanging; place of execution.- All persons

who shall be convicted of a capital crime

and who shall have imposed upon them the

sentence of death, shall suffer such pun-

ishment by electrocution instead of by

hanging. :

In all cases in which the defendant is

sentenced to be electrocuted it shall be

the duty of the trial judge, in passing

sentence, to direct that the defendant

be delivered to the Director of Corrections

for electrocution at such penal institution

as may be designated by said Director. How-

ever, no executions shall be held at the old

prison farm in Baldwin county. (Acts 1924,

Pp. 195,197: Acts ‘1937-38; Extra.Sess., D.

330.)

STATEMENT

This is a petition for writ of certiorari to review the

judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia, entered April 24, 1969,

affirming petitioner's conviction and sentence of death.

Petitioner was tried for the capital crime of murder in

the Superior Couteae Chatham County, Georgia, on September

20, 1968. One of the prospective jurors for petitioner's Luisi;

Mr. Alvin W. Anchors, Sr., was eliminated for cause on the basis

of a brief inquiry regarding his conscientious opposition to cap-

ital punishment (R.289-290).

At the close of petitioner's one day trial the issues of

guilt and punishment were submitted to the jury which was given

no instructions limiting or directing its absolute discretion,

in the event of conviction, to impose a sentence of life or

death.

The jury found petitioner guilty of murder, without

recommendation of life imprisonment (R.10), and he was according-

ly sentenced to death by electrocution (R. 19). He appealed to

the Supreme Court of Georgia which, on April 24, 1969 affirmed

his eonvideion and sentence of death.

on May 3, 1969 the Hon. W. H. Duckworth, Chief Justice of

the Supreme Court of Georgia, stayed execution of the judgment.

for a period of 90 days from April 24, 1969 in order to allow

a petition for writ of certiorari to be filed in this Court.

(R.424).

~ HOW THE FEDERAL QUESTIONS WERE RAISED

AND DECIDED BELOW

At trial petitioner's counsel objected to the exclusion

of juror Anchors because of his opposition to capital silane

and further objected to Anchors' exclusion on the basis of his

answers to the questions he was asked concerning such opposition

(R. 292-293). The telal court found that Anchors was properly

excluded for cause apparently because Anchors had stated that

he thought his opposition to the death Seralty would "affect"

his decision as to guilt (R. 290,294).

Petitioner's Amended Motion for New Trial (R. 37-48) raised

the three federal questions Presented } here, arguing that the

exclusion of juror Anchors violated petitioner's Fourteenth

Amendment rights as defined in Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S.

2/

510 (1968) (R. 42-44); that the grant to the jury of uncontrolled

discretion to choose a life or death sentence violated peti-

tioner's Fourteenth Amendment rights (R. 45) ; and that peti-

tioner's sentence of death constituted cruel and unusual pun-

ishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments

(R. 41-42). This motion was denied by the trial court without

opinion on February 24, 1969 (R. 49).

1l/ Petitioner's counsel also objected to the exclusion of jurors

on the grounds of their opposition to capital punishment in a

written motion, denied without opinion by the Superior Court on

September 20, 1968 (R. 17-18).

2/ Petitioner argued that he was denied a fair trial on the

guilt issue as well as the punishment issue by the exclusion of

a scrupled juror.

4 i

Petitioner's Enumeration of Errors and Brief in the Supreme

Court of Georgia (R. 410-413) again raised, among other claims,

the questions presented to this Court: That petitioner's sentence

bE death violated the United States Constitution in that it con-

stituted cruel and unusual punishment, and had been imposed by

a jury with uncontrolled discretion from which a scrupled juror

had been improperly excluded. The Enumeration of Errors also

alleged that "the Court erred in one and all of the respects set

out in the amended Motion for a New Trial and for the reasons

set forth thereon" (R. 411).

The Supreme Court of Georgia denied petitioner's Witherspoon

claim in the following language:

A juror having been excluded for

cause because he stated that his

opposition to the death penalty

would affect his decision as to

a defendant's guilt, his exclusion

| did not fall within the rule as

laid down in Witherspoon v. Illinois,

; 391'U.8--510 (88 SC 1770, 20. 15-24

776), and the court 4id not err in

excluding him for cause. There is

no merit in the amended motion com-

plaining that the exclusion violated

: : the rule in the Witherspoon case,

4 supra. (R. 414-415).

i

§

q

£

|

i

i

1

4

3

:

i

The Court dismissed petitioner's ‘arguments ‘on uncontrolled jury

discretion and cruel and unusual punishment even more briefly:

The statutes of this State authorizing

capital punishment have repeatedly been

held not to be cruel and unusual punish-

ment in violation of the Constitution.

See Sims v. Balkcom, 220 Ga. 7(2) (136

SE2d 766); Manor v. State, 223 Ga. 594

(18), supra. Hence, there is no merit

in this complaint. (R. 416-417). 3/

3/ Both the cases cited by the Georgia Supreme Court dealt

specifically with both the issues of uncontrolled jury discretion

and cruel and unusual punishment.

o

i

|

i

= NN

|

i

. courts believe that Witherspoon should be implemented. The result

Miller v. State, 224 Ga. 627, 163 S.E. 24 730(1968). See also

The Court concluded that, / "having considered every enumeration

of error argued by counsel in his brief and finding no reversible

error, the judgment is affirmed." (R. 418).

ARGUMENT

THE COURT BELOW HAS MISAPPLIED THE STANDARDS : pit

OF WITHERSPOON V. ILLINOIS, 391 U.S. 510 (1968),

AND HAS THEREBY CONDONED THE DENIAL TO PETITIONER

OF A FAIR JURY TRIAL ON THE ISSUE OF THE DEATH

SENTENCE.

A. The Test of Exclusion Applied - by the Court Below

Did Not Meet the Minimum Standards Required By

The Constitution As Announced in Witherspoon.

The selection of petitioner's jury took place in September

2/

1968 -- after this Court's decision in Witherspoon. It is

therefore of particular significance in indicating how the lower

below is symptomatic of the restrictive and unsympathetic reading

that Witherspoon has been given by virtually every state court

: 4a/

that has considered it, and of the effective stultification of

that decision which presumably will continue until this Court"

clarifies Witherspoon's meaning and insists upon its enforcement.

4/ Prior to Witherspoon, Georgia practice authorized the exclusio¢n

of jurors who stated that they were conscientiously opposed to

capital punishment, pursuant to Georgia Code Ann. §§59-806. This

practice was declared unconstitutional, under Witherspoon in

Williams v. Dutton, 400 F.2& 797(5th Cir..1968).

4a/ See, e.g., Davis v. State, 440 S.W. 2d 244 (Ark. 1969);

Campbell v. State, Florida Supreme Court, No. 35,622 (June 11,

1969) ; People v. Speck, 41-111. 24: 177, 242. N.E.24 208 (111.

1968); People v. Mallett, 244 N.E. 24 129 (Ill. 1969); State wv.

Crock , 221 So. 24 473 (La. 1969); Veney v. State,-245 A. 24568

(Md. 1968); State v. Mathis,52 N.J. 238, 245 A. 24 20 (1968);

Pittman v. State, 434 S.W. 2d 352 (Texas 1968); Scott v. State,

Fn —

434 S.W.24 678 (Tex. 1968): Smith v. State,437 5. W. 24 835{Tex.

1968); State v. Aiken, 452 P. 24 232 (Wash. 1969).

. »

It is essential that the Court act now not merely in the interests

of those who have been and will be condemned to die by unconsti-

tutionally selected juries,but also in the interests of the

. orderly administration of justice. Witherspoon, which this Court

reaffirmed in Boulden v. Holman, 394 U.S. 478 (1969) held that

no sentence of death could constitutionally be imposed by a

jury from which prospective jurors had been excluded for opposi-

tion to the death penalty unless, at the least, the excluded

“jurors had made

i

;

i

i

i

4

i

i

i i

1

. ®

"unmistakably clear (1) that they would

automatically vote against the imposition

of capital punishment without regard to

any evidence that might be developed at

the trial of the case before them, .or (2)

J that their attitude toward the death penalty

would prevent them from making an impartial

decision as to the defendant's guilt. (391

U.s., at 522-23, n. 21). (emphasis in original)

The court below held that juror Anchors was properly ex-

cluded on the basis of his statement that his opposition to the

death penalty wouldraffect his decision as to a defendant's

.5/

guilt. The relevant testimony follows:

MR. BARKER [counsel for the State]:

Do you think that your attitude

toward the death penalty would prevent you

from making an impartial decision as to

the defendant's guilt ?

MR. ANCHORS: (Inaudible)

MR. BARKER: Pardon me, sir?

MR. ANCHORS: I said I am opposed --

MR. BARKER: Would this opposition to the death

penalty affect your decision as to a defendant's

guile?

MR. ANCHORS: I think it would.

MR. BARKER: I would ask that he be stricken for

cause, Sir.

THE COURT: All right; have a seat, Mr. Anchors.

(R. 290)

5/ This was apparently the basis of the trial court's ruling

as well. (R. 290,294).

w LOS

This exchalge cannot justify exclusion for cause under

Witherspoon.

adequately to distinguish the

It is extremely likely that a

and that a statement that his

|

his decision as to guilt would be premised on this false assumptio

Juror Anchors' answer might well have been different if he had

been fairly informed that, under Georgia law, the jury is free, in

a capital trial, to impose a life sentence rather than a death

sentence upon a guilty defendant, for whatever reason it chooses,

or for no reason at all. (See

¢

it is .essential at least that

penalty is not mandatory upon

they have complete discretion

fendant to life or death.

The above inquiry is further inadequate as a basis for con-

stitutional disqualification because juror Anchors' answer was

impermissibly equivocal -- he

thought his opposition to the

decision. Neither the prosecution nor the court pressed him

further on the point, to determine whether, despite his attitude

toward the death penalty, he could do his duty as a juror to

decide impartially between the defendant and the State on the

issue of guilt. In sum, this

that juror Anchors made "unmistakably clear . . .

[his] attitude toward the death penalty would prevent . .

from making an impartial decision -as to the defendant's quire,»

The finding of the

requirements makes

Juror Anchors

capital punishment

punishment in a case regardless of the evidence."

"I believe I would." (R.

on by the court below nor, apparently, by the trial court to

=3] -

In the first place, the form of the inquiry fails

court below that it did satisfy Witherspoon's

a mockery of that decision.

was also asked whether his opposition to

meant that he "would refuse to impose capital

289-90).

gullt issue from the penalty issue.

juror would assume from this inquiry

Yes? os em

upon a finding of guilt,

conscientious opposition might affect

Part II, infra) .Under Witherspoon

jurors be informed that the death -

a finding of guilt and that instead

as to whether to sentence the de-

finally admitted only that he

death penalty would affect his

exchange cannot justify a finding

that. .

[him]

He responded

This exchange was not relied

» »

exclude him. And certainly it cannot justify exclusion under

Witherspoon standards. The question is vague and ambiguous and

could well be interpreted as asking whether the juror might re-,

fuse to impose the death penalty where the evidence showed the

defendant to be guilty, in which case the juror's answer was

perfectly proper. Certainly this question, and Anchors’

sduivoaal response, failed to show that he would never in any

type of case be willing to Surdas the death penalty. (See

Eculden Vv. Holman, 394 U.S. 478 (1969); still less did it make

unmistakably clear" that he "would autdmatically vote against

1 ; the imposition of capital punishment" (Witherspoon v. Illinois,

supra, 391 U.S. at 522-23,n. 21) and would be unwilling even to

consider its imposition regardless of the circumstances of a

| particular case before him.

B. The Court Below Erred in Approving Death Qualification

Practices, Whose Constitutionality Raises The Question

Expressly Reserved in Witherspoon.

S

d

b

m

AR

te

08

Even if the exclusion of juror Anchors were outside the

express condemnation of Witherspoon, the death-qualifying

practice employed to excuse him for cause raises the question

reserved in Witherspoon: Whether by any standard, jurors

| can be excluded in capital cases merely because of the strength

of their opposition to or conscientious scruples against the

death penalty.

Petitioner submits that the logic of this Court's opinion

in Witherspoon makes clear that the Constitution will countenance

no death-qualifying of capital juries, however limited.

-— 13

That this issue be considered now by this Court is crucial,

for not only have the lower state and federal courts often

vastly limited what appeared to be the clear meaning of the |

;

Witherspoon holding, but they have chosen to interpret this

Court's reservation of the question raised by the narrower

form of death-qualifying practices as a constitutional valida-

6/

tion of those practices. They have so read Witherspoon even

though this Court carefully limited the issue before it:

"The issue before us is a narrow

one. It does not involve the right

| of the prosecution to challenge for

‘ : cause those prospective jurors who

state that their reservations about

capital punishment would prevent

them from making an impartial decision

as to the defendant's guilt. Nor does"

it involve the State's assertion of a

right to exclude from the jury in a

capital case those who say that they

could never vote to impose the death

penalty or that they would refuse even

to consider its imposition in the case

before them. (391 U.S., at 513-14)

(emphasis added).

The Court's opinion leaves no doubt that Witherspoon should not

| be read to validate constitutionally those tests and practices

of exclusion that fall outside its specific condemnation.

"We repeat, however, that

nothing we say today bears upon

s the power of a State to execute:

| a defendant sentenced to death by

—- a jury from which the only venire-

men who were in fact excluded for

cause were those who made unmistakably

clear (1) that they would automatically

vote against the imposition of capital

punishment without regard:-to any evi-

dence that might be developed at the

trial of the case before them, or (2) that

their attitude toward the death penalty

would prevent them from making an impartial

decision as to the defendant's guilt."

{¥8., at. 522-23, n. 21.)

6/ B.g., Bell v. Patterson, 402 F.-24 394 (10th Cir. 1968);

State v. Mathis, 52 N.J. 238, 245 A. 24 _20:(1968); Pittman'v.

State, 434 sS.W. 24 352 (Tex.Cr.App. 1968).See also the cases

cited in n. 4a, supra.

SO

And the Court avoided even the acceptance of arguments which

might support the narrower sort of death-qualification practice.

: If the State had excluded only

those prospective jurors who stated

in advance of trial that they would

not even consider returning a verdict

of death, it could argue that the re-

sulting jury was simply "neutral" with

respect to penalty. (Id. , at 520)

(emphasis added).

Not only does Witherspoon not validate the narrow forms

of |death-qualification, but its logic leads directly to the

conclusion that wherever state law leaves the death penalty

to the jury's unfettered discretion, no system of excusing

prospective jurors can be consistent with a defendant's right...

to a representative jury on the determination of the death

sentence.

We say this for several reasons. First, Witherspoon

recognizes that where the jury has broad discretion in choosing

between life and death, its decision is no more than the re-

flection of the conscience of the community,and it must be no

less than a reflection of the conscience of the total community

" A man who opposes the death

penalty, no less than one who favors

it, can make the discretionary judgment

entrusted to him by the State and can

thus obey the oath he takes as a juror.

But a jury from which all. such men have

been excluded cannot perform the task

demanded of it. Guided by neither rule

nor standard, 'free to select or reject

as it [sees] fit, ' a jury- that must choose

between life imprisonment and capital pun-

ishment can do little more =-- and must do

nothing less -- than express the conscience

of the community on the ultimate question

of life or death. Yet, in.a nation less

-ila

{

§

|

i

3

i

|

x

i

1

=

than half of whose people believe

in the death penalty, a jury composed

exclusively of such people cannot speak

for the community. Culled of all who

harbor doubts about the wisdom of

capital punishment -- of all who would

be reluctant to pronounce the extreme

penalty -- such a jury can speak only

for a distinct and dwindling minority."

{391-U.8., at 519-20.)

While the Court needed to have been concerned here only with

those who remain eligible for capital juries after the sort of

L

~brqadside death-qualification condemned in Witherspoon, the same

-can| be said of capital ‘juries from which are excluded those who

would never vote for the death penalty. Of those who would be

excluded under the broader test, it appears that more than

one-half would also be excluded even after more meticulous voir

dire examination designed to eliminate only veniremen who are

unalterably unwilling to vote the death penalty in any case.

Zeisel, Some Data on Juror Attitudes ‘Towards Capital Punishment

7-8 (Center for Studies in Criminal Justice, University of

7/

Chicago Law. School, 1968). It can thus be said of a jury

death-qualified by this narrower, stricter process -- as was

said of the jury in Witherspoon -- that it "can speak only for

a distinct and dwindling minority. {391 U.85., at 520).

7/ Of the persons who,, in a national poll conducted by the

Gallup Organization, answered affirmatively that they had "con-

scientious or religious scruples against the death penalty,"

“Professor Zeisel found that 38% would nonetheless vote. for the

death penalty "reluctantly, if there were no mitigating circum-

stances," or if it were a horrible murder and a most terrible

murderer." Another 3% answered "don't know." And 53% who ad-

mitted to scruples against the death penalty stated that they

would in. no case vote the death penalty. This group, then,

would be struck from the jury even after the more meticulous

and narrow voir dire.

]

;

4

Second, the rationale of Witherspoon suggests that any

death qualification procedure unjustifiably distorts the con-

stitutionally requisite representativeness of the jury that sits

to determine the penalty issue. Although the vice condemned in

Witherspoon is expressed in terms of the jury being "stacked,"

Or -& "hanging Jury," id., at 523, the concern expressed by these

phrases connotes not merely unfairness, but unbalance. A deck

or a jury is "stacked" by over-inclusion, over-representation

of one type, with consequent under-representation of another

or others. And a "hanging jury" is not seen to be so in

absolute but in relative terms -- it is a jury more prone than

most to-kill. We take it that no defendant could complain of

a "hanging jury" chosen by the luck of the draw and fairly

representative of a "hanging community." What Witherspoon

condemns is an unrepresentatively, a disproportionately, death-

prone jury =- one chosen by a process that skews and distorts

the community character of the jurors with regard to the vital

penalty question. |

Witherspoon thus confirms that what is wrong with a rule

excusing for cause a class of veniremen characterized by. their

particular views on the subject of the death penalty is that the

process renders the remaining jurors unrepresentative; and that

such a rule affronts the "established tradition in the uso of

juries as instruments of public justice [which has’ now. become -

a constitutional command] that the jury be a body truly rep=

resentative of the community." Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128,

130 (1240). The point is no less valid if a narrower, rather

than a broader, standard is employed to test the nature of the

venireman's views that work his disqualification. The State's

. 9

justification for a jury selection process which makes the Suvy

unrepresentative is also essentially the same for all forms

and species of death-qualifying procedure: that the disqualified

jurors "cannot be relied upon to vote for [capital punishment]

. « «. even when the laws of the State and the instructions of

the trial judge would make death the proper penalty." Witherspoon,

supra, 391 U.S. 510, at 518-19. But this Court flatly rejected

that supposed justification, and for reasons not limited to the

8/5:

holding in Witherspoon. Illinois' asserted purpose for exclud-

ing scrupled jurors was rejected not alone because the state's

exclusionary practice went beyond the necessities of that pur-

pose, but on the broader constitutional logic that a capital

trial process which gives the jury limitless discretion to

sentence to life or death COmpOrts no sufficient justification

for excusing jurors on the sole ground that they will exercise

that discretion on the grounds of principle. "A man who opposes

the death penalty . . . . [and, we add, one who will never vote

for it], can make the discretionary judgment entrusted to him

by the State and can thus obey the oath he takes as a juror."

321 U.S., at 519. He can follow the law; he is told to exercise

his discretion, and he will do so as well and as surely in

accordance with his conscience as the next man.

(oe

bn

, "But in Illinois, as in other States, the

jury is given broad discretion to decide

whether or not death is 'the proper penalty'"

in a given case, and a juror's general views

about capital punishment play an inevitable

role in any such decigion.™ (391 U.S8., at

519.)

<7 =~

ey

GEORGIA'S PRACTICE OF ALLOWING .

CAPITAL TRIAL JURIES ABSOLUTE :

DISCRETION TO IMPOSE THE DEATH

PENALTY, UNCONTROLLED BY STAN-

DARDS OR DIRECTIONS OF ANY KIND,

VIOLATES THE DUE PROCESS . CLAUSE

OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT.

Georgia law grants the jurors in a murder trial the power

to choose between a sentence of life imprisonment and the death

S/ :

penalty. Neither the statutes nor the cases define any standards

guiding the exercise of this power. Accordingly the court below _

10/

gave the jury no guidance in its charge. Indeed it would

9/ Ga. Code Ann. §26-1005 (1968 Supp.) provides that the penalty

for murder (by persons 17 years of age and older) shall be death

unless the jury recommends life imprisonment in which case it

shall be life. (Similar provisions apply for all other capital

crimes. See Ga. Code Ann.-.§27-2302 (1968 Supp.):; Ga. Code .Ann.

(1953 and 1968 Supp.)§§26-801 (treason); 26-903 (insurrection);

26-1007 (killing in revenge); 26-1009 (felony where death is

natural consequence) ;26-1103 (foeticide) ;26-1302 (rape) ;26-1603

(kidnapping for ransom); 26-1701 (stabbing causing death); 26-2206

(arson causing death); 26-2502 (robbery by force or use of offen-

sive weapon); 26-4007 (false witness causing death); 26-5203 (fight-

ing duel where death results) ;26-5401 (mob violence where death

results); 26-7314 (death caused by wrecking train) .) a=

The judge may alter the jury's decision only when the murder

conviction is founded solely on circumstantial testimony, and

the jury has not recommended life, in which event the judge may

sentence the defendant to life imprisonment. This provision is

significant in indicating a legislative judgment that. circumstan-

tiality of evidence is a factor relevant to the decision whether

death is an appropriate penalty. Yet the jury is not even told

to consider this factor when making its choice as to life or

death.

10/ : I charge you that the punishment for murder is

death by electrocution, but.you, the jury, have

the right in your discretion to recommend him to

the mercy of the Court and fix the punishment for

life, either of which actions by you would be bind-

ing upon the Court. The Jury does not have to give

any reason for its action in fixing the punishment

at life or death. It does not even have to find:

that there were extenuating circumstances. The

punishment is an alternative punishment and may

be one or the other as the jury sees fit. (R.404)

® »

have been improper under Georgia law for the court to have

attempted to instruct the jury regarding the exercise of their

discretion. Juries may, under Georgia law, decide between life

11/ :

and death for any or for no reason. McBurnett v. State, 206

Ga. 59, 55 S.E. 2d 598,599 (1949). The choice is"a matter solely

10/ cont'd.

When the jurors returned to ask whether they could "render a

verdict, leaving it tothe discretion of the cork .... ."

the court interrupted "No, Sir. 1 have given you the forms

of| the verdicts. It's up to the jury to determine." (R. 405).

11/ The record in this case provides an illustration of the

darigers of such untrammelled discretion. The transcript of the

voilr dire in another criminal trial was made part of the record

in petitioner's case. During the voir dire the following ex-

change took place:

Q You know - the law says that all

persons charged with crime are

entitled to equal treatment. By

that it means that it would be your

duty as a juror if you found the

defendant guilty or in determining

whether he's guilty or not, if you

did find him guilty to impose the

same punishment, no more or no less,

if he were a white man under similar

circumstances - do you agree to this?

Ail Yes, Sir.

MR. RYAN [Solicitor General of Chatham

County] : I am going to object to that,

sir, because it's not a proper question.

THE COURT: 1 sustain your objection to it.

MR. RYAN: The law gives the juror the privi-

lege . . in murder cases, for instance --

no-reason at all to disregard the death

penalty and impose life imprisonment. That's

why -I make the objection -- the same set of

circumstances and the jury can do two

different things. (R. 241)

- 19 =

in their discretion, which is not limited or confined in any

.case." Williams v. State, 46 S.E. 626 (1904).

"The jury in determining whether

or not to recommend mercy is not con-

trolled by any rule of law, nor could

the court under any circumstances in-

struct them as to when they should, or

should not, make such a recommendation.

They may do so with or without a reason,

and they may decline to do so with or

without a reason. It is a matter wholly

{ within their discretion." (Hicks v. State,

196. ga. 671, 27 8.2. 24 307,°309:(1943Y.

And| again, in Daniels v. State, 35 S.E. 3d 362, 363 (1945) the

Supreme Court of Georgia upheld a charge. that the jury's choice

could be made "with or without reason, arbitrarily, just as they

might see fit . . ."

Petitioner challenges the Georgia practice described above

of permitting the trial jury absolute discretion, uncontrolled

by standards or directives of any kind, to impose the death

penalty as a violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. This Court has granted review on the identical ques-

tion in Maxwell v. Bishop, Oo. T. 1968, No.. 622. In addition,

a score of petitions for certiorari raising the same

federal constitutional claim involved in this petition have

been filed with this Court and are now pending. E.g., Childs

v. North Carolina, O. T. 1968, No. 1326 Misc.; McCants v. Alabama,

O. T. 1968, No. 937 Misc.:; Johnson v. Virginia, O. T. 1968, No.

307 Misc.:; Forcella v. New Jersey, O. T. 1968, No. 947 Misc.;

Anderson et al., v. California, O. T. 1968, No. 1643 Misc.

EE

et ® @

Petitioner's views on the merits of this question are

fully discussed in the Brief for Petitioner filed in Maxwell

» v. Bishop, supra, at pp. 6-9,11-65, and therefore, rather than -

rehearse those arguments here, we respectfully refer the Court

to that brief. We add only that, should the Court decide the

Maxwell case (and the other cases raising this issue noted

supra) on other grounds, certiorari should be granted here

so that this Court can decide whether a death penalty determina-

tion made by a jury unguided by any legal standards comports

with the Constitution -- a question affecting the lives of

virtually all of the more than 400 condemned men on the death

rows of this Nation.

11x

PETITIONER'S DEATH SENTENCE CONSTITUTES

CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT IN VIOLATION

OF THE EIGHTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS

TO THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES.

: Petitioner challenges the death penalty as administered in

Georgia for the crime of A a violation of the Eighth

and Fourteenth Amendment prohibitions ‘against cruel and unusual

punishment. This Court granted review last term in Boykin v.

Alabama, O0.T. 1968, No. 642, which raised the question of the

application of the cruel and unusual prohibition to the death

penalty for the crime of robbery. Although the case was ulti-

mately decided on other grounds, 89 S.Ct. 1709 (1969), the issue

12/ Under Georgia law there are no degrees of murder -- and all

murder is capital, Ga.Code Ann. §§26-1001(1953), 26-1002 (1953),

26-1005 (1968 Supp.), 26-1009(1953). - The other capital crimes

in Georgia are listed supra at n. 9, p. 18. =

«21%

13/

was fully briefed and argued there. Considerations similar

to those briefed in Boykin govern the application of the Eighth

prohibitions to the death penalt o.. the death pen Y

murder in Georgia. Petitioner respectfully refers the Court to

the arguments made there, which will be briefly summarzed here:

It is petitioner's contention, in sum, that his sentence of death

constitutes a cruel and unusual punishment because it affronts

contemporary standards of decency, universally felt, that would

condemn the use of death as. a penalty for the crime of murder

if| such a penalty were uniformly, regularly and evoihanzedly

2oglied either to all those Sully of murder or to any non-

arbitrarily selected sub-class thereof.

| In the first place, far from being "widely accepted,"

Trop Vv. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 99 (1958), the death penalty today

is with rare public unanimity rejected and repudiated.

13/ See Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the National

Organization for the Rights of the Indigent, as amici curiae,

PP. 24-61.

-i37

All informed observers of the death penalty agree in

describing a world-wide trend toward its disuse hit is *

nothing short of drastic. See UNITED NATIONS 81-82,96-97; SELLIN

(1959) 4-14; MATTICK, THE UNEXAMINED DEATH (1966) [hereafter glted

as MATTICK]5-6; Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment,

284 ANNALS 8 (1952); Sellin, The Inevitable End of Capital Pun-

ishment, in SELLIN, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT (1967) 239-240; Bedau,

Death Sentences in New Jersey 1907-1960, 19 RUTGERS L.REV. 1,

9-11 (1964). In the United States, the «decreasing trend of execu-

tions has been especially dramatic. The National Crime Commission

recently noted that:

"The most salient characteristic of

capital punishment is that it is in-

frequently applied . . .[A]ll available

data indicate that judges, juries and

governors are becoming increasingly

reluctant to impose or authorize the carry-

ing out of a death sentence." (PRESIDENT'S

COMMISSION ON LAW ENFORCEMENT AND ADMIN-

ISTRATION OF JUSTICE, REPORT (THE CHALLENGE

OF CRIME IN A FREE SOCIETY) (1967) 143.)

The extent to which this is true appears upon inspection of the

highly reliable figures on executions maintained by the Federal

Bureau of Prisons since 1930. Its latest cumulative report

shows that 3,859 persons were executed under civil authority

in the United States between 1930 and 1967. UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, BUREAU OF PRISONS, NATIONAL PRISONER

STATISTICS, No. 42, Executions 1930-1967 (June 1968) [hereafter

cliced as NPS(1968)], p. 7. Of these 3,859, only 191 were executed

between 1960 and 1967; only 25 during the years 1964-1967. Ibid.

The trend is shown quite adequately by setting out the figures

for the number of executions during each of the following rep-

resentative years:

i033 o

® ®

Total Number of Executions

in the United States

1930 - 155

| 1935 - 199

1940 os 124

1945 - 117

1950 - 82

1988. > = 76

; 1960 - 56 :

1961 - 42

1962 - 47

1963 — 21

1964 - 15

1965 - 7

1966 -— i

1967 - 2

During the calendar year 1968, and oe far in 1969, there have

been no executions in the United States. There have been no

executions in Georgia since 1964.

Of course, the penalty remains on the statute books, but

we submit, only because of the rarity and arbitrariness with

which it is applied. It is a matter of history that public

acceptability of the death penalty has been maintained only

by allowing discretion in capital sentencing -- discretion

which, as argued in part II, supra, is wholly arbitrary. Further,

the available evidence indicates that the death penalty has in

fact been arbitrarily applied. In the first place arbitrariness

is an almost necessaxy result where the death penalty is imposed

with such extreme rarity. Secondly, the statistics and studies

- 2

- ~ Ls

|

14/

provide persuasive evidence of class and racial discrimination.

.The death penalty is no part of the regular criminal-law machinery

of Georgia or of the nation. It is a freakish aberration, a

rare, extreme act of violence, visibly arbitrary, probably

racially discriminatory =-- a penalty reserved for wholly arbitrary

application because, if it were regularly used it would affront

universally shared standards of public decency. Such a penalty--

not Law, but Terror -- is the instrument of totalitarian govern-

ment. It is a cruel and unusual punishment, forbidden by the

Eighth Amendment.

CONCLUSION

Petitioners pray that the petition for a writ of certiorari

be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

i MICHAEL MELTSNER

i JACK HIMMELSTEIN

1 ] - ELIZABETH B. DUBOIS

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

i

|

|

1

1

4

4

|

§

i i

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

1 Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

B. CLARENCE MAYFIELD

910 West Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

Attorneys for Petitioner

14 / We will not attempt to outline here the available evidence,

but it is interesting to note that over 80% of the people who have

been executed in Georgia since 1930 have been Negro.

I

APPENDIX A

Opinicn Of The Court Below

v re cs tt 3 ni Sn Brn

628 Ga.

William Henry FURMAN

: Ys

The STATE.

No. 25163.

_ | Supreme Court of Georgia.

April 24, 1969.

Defendant was convicted in the Supe-

rior Court, Chatham County, Dunbar Har-

rison, J., of murder and he appealed. The

Supreme Court, Duckworth, C. J., held that

excluding for cause juror who stated that

his opposition to death penalty would af-

fect his decision as to Sefendant’s guilt

_ was not error.

Affirmed

I. Jury ¢=108

Excluding for cause juror who stated

that his opposition to death penalty would

affect his decision as to defendant’s guilt

was not error.

2. Criminal Law €=2412.2(3)

Evidence of defendant’s statements in

regard to crime charged was properly a

mitted where trial court found that detent.

ant’s constitutional rights were adequately

explained to him at time of arrest and that

he thereafter freely and voluntarily and

knowingly made the statements.

3. Criminal Law ¢=339, 394.4(9)

- Extrinsic evidence of fingerprints and

pistol obtained after arrest should not have

been suppressed where defendant had been

adequately apprised of his constitutional

rights.

4. Criminal Law ¢=1213

Statutes authorizing imposition of cap-

ital punishment do not violate constitution-

al proscriptio 3 of cruel and unusiral pun-

ishment. ..

-

aad

167 SOUTH EASTERN REPORT

PE SS AE rt tle. rs St. melt. Po 0 Aine

ER, 2d SERIES

5. Arrest &=70

Detention or imprisonment beyond 48-

hour statutory requirement does not render

jury verdict after indictment illegal or

void. Code, § 27-212,

6. Criminal Law ¢=228 i

Fact that commitment hearing was not

held until four days after arrest did not,

where no secret inquisition or interrogation

was claimed, fender subsequent Bily ver-

dict void. Code, § 27-212.

7. Homicide €&=235

Evidence supported conviction of mur-

der by shooting occurring during burglary.

Code, § 26-1004.

————emt—

B. Clarence Mayfield, Savannah, for ap

pellant.

Andrew J. Ryan, Jr., Dist. Atty., Robert

E. Barker, Savannah, Arthur K.- Bolton,

Atty. Gen., Marion O. Gordon, Asst. Atty.

Gen.,, Larry H. Evans, Atlanta, for appel-

lee. !

Syllabus Opinion by the Court

DUCKWORTH, Chief Justice.

This case involves the crime of murder

by shooting,” occurring during a burglary

after the intruder had been discovered by

the deceased who was then shot through a

closed door. The accused was indicted,

tried and convicted without a recommenda-

tion for mercy. A motion for new trial, as

amended, was filed, heard and overruled,

and the appeal is from the judgment, after

conviction, and sentence with error enu-

merated on the denial of the motion for

new trial, as amended. Held: :

[1] 1. A juror having been excluded

for cause because he stated that his opposi-

tion to the death penalty would affect his’

decision as to a defendant’s guilt, his ex-

clusion did not fall within the rule as laid

down in Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S.

a

t

e

t

C

E

I

G

E

VI

E

S

N

S

T

A

I

0

A

A

T

R

T

R

E

N

PW

NR

A

T

A

A

T

|

H

5

5

A

T

P

or

|

510, 88 S.Ct. 1770, 20 L.Ed.2d 776, and the

court did not err in excluding him for

cause. There is no merit in the amended

motion complaining that the exclusion vio-

lated the rule in the Witherspoon case, su-

pra. &: :

[2] 2. The record showing a defini-

tive determination from a consideration of

‘the evidence by the trial judge, out of the

jury’s presence, that upon his arrest the

accused had his constitutional rights ex-

p'rined to him, including the right to re-

main silent, the right of counsel, and that

anything he said might be used against him

in court, and that he thereafter freely and

voluntarily and knowingly made certain

statements in regard to the crime, the same

was admissible both legally and factually,

“and all the requirements of Miranda v. Ari-

zona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.

"Ed.2d 694; Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S.

“335, 83 S.Ct. 792; 9 L.Ed.2d 799; Escobedo

v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478, 84 S.Ct. 1738, 12

L.Ed2d 977,- and Jackson v. Denno, 378

U.S. 368, 84 S.Ct. 1774, 12 L.Ed.2d 908,

have been complied with fully and com-

pletely. . We_find no merit in the conten-

H

E

ST

S

€ C

AT

PE

A

T

I

WT

S

T

I

P

E

e

r

O

P

T

N

tion of counsel that his constitutional

rights had been violated. _

“133 3. We find no violation of Miran-

da v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602,

supra, as contended by counsel, hence the

extrinsic evidence of fingerprints, admis-

sions, and pistol were properly allowed in.

evidence ‘against him and should not have

been suppressed. Manor v. State, 223 Ga.

594(3), 157 S.E.2d 431; Schimerber v. Cal-

ifornia, 384 U.S. 757, 86 S.Ct. 1826, 16 L.

Ed2d 908; Terry v. Ohio, 392 US. 1, 88

S.Ct. 1868, 20 L.Ed.2d 889.

[4] 4. The statutes of this State au-

thorizing capital punishment have repeat-

edly been held not to be.cruel and unusual

punishment in violation of the Constitution.

FURMAN v. STATE

Cite as 167 S.E.2d 628 . SD;

Ga.” 629

See Sims v. Balkcom, 220 Ga. 7(2), 136 S.

E2d 766; Manor v. State, 223 Ga.

594(18), 157 S.E.2d 431, supra. . Hence,

there is no merit in this complaint.

[5,6] 5. The record discloses that the

accused was arrested on August 11, 1967,

and a commitment hearing held on August

15, 1967. While Code Ann. § 27-212 (Ga.

L.1956, pp. 796, 797) requires a hearing

does not render the verdict of a jury after

indictment illegal or void. It has already

been held above that the evidence of fin-

within 48 hours, nevertheless, a detention

. or imprisonment beyond a reasonable time

gerprints, pistol and admissions which were.

obtained after his arrest could be used

against him, and no secret inquisition or

interrogation is claimed in this case. See

Dukes v. State, 109 Ga.App. 825(1), 137

S.E.2d 532; Pistor v. State, 219 Ga. 161,

132 S.E.24 183. :

[7] 6. The admission in open court by

the accused in his unsworn statement that

during the period in which he was involved

in the commission of a criminal act at the

home of the deceased, he accidentally

tripped over a wire in leaving the premises

causing the gun to go off, together with

other facts and circumstances surrounding

the death of the deceased by violent means,

was sufficient ta support the verdict of

guilty of murder, and the general grounds

of the motion for new trial are not merito-

rious. See Code § 26-1004; Williams wv.

State, 222 Ga. 208, 149 S.E.2d 449; Manor

v. State, 223 Ga. 594, 157 S.E.2d 431, su-

pra. :

7. Having considered every enumera-

tion of error argued by counsel in his brief

and finding no reversible error, the judg-

ment is

Affirmed.

All the Justices concur.

7

4