New York v. Sullivan Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. New York v. Sullivan Brief for Petitioners, 1990. ce0fdd7c-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ea2527cc-2a35-4ab0-8919-11d0b8c7ab2d/new-york-v-sullivan-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

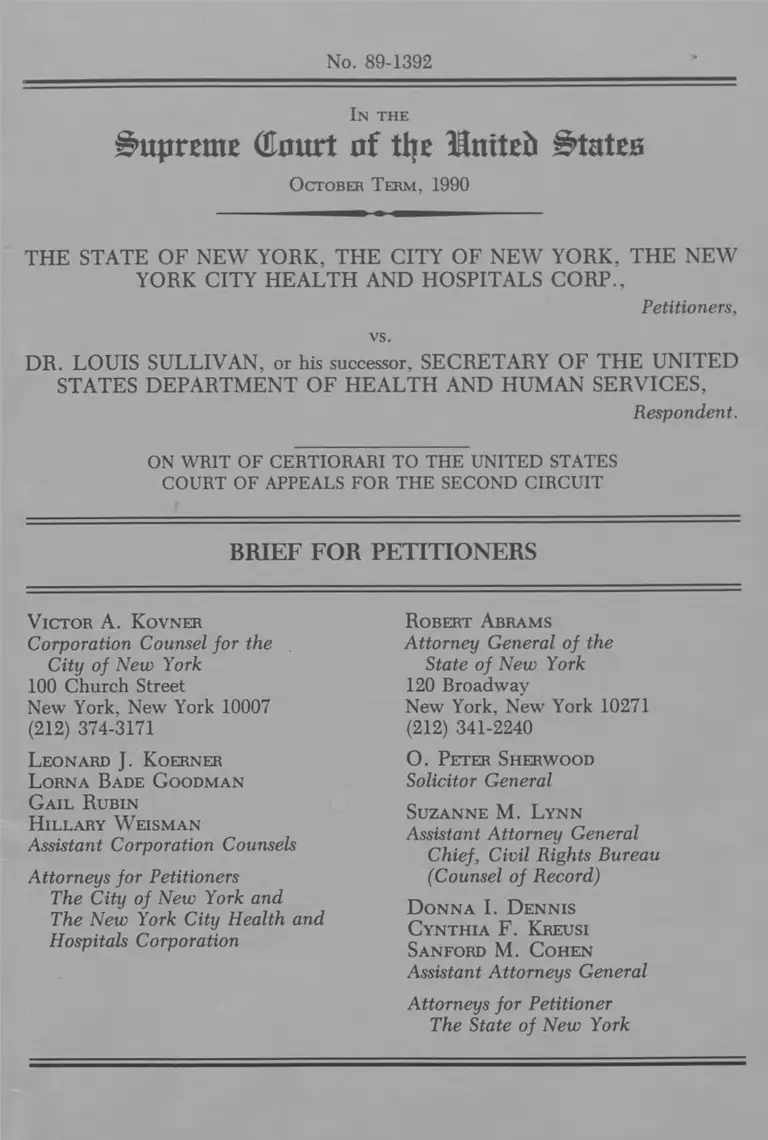

No. 89-1392

I n t h e

Supreme (Enurt of the llniteb States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1990

T H E S T A T E O F N E W Y O R K , T H E C IT Y O F N E W Y O R K , T H E N E W

Y O R K C IT Y H E A L T H AND H O SP IT A L S C O R P .,

Petitioners,

vs.

D R . L O U IS SU L L IV A N , or his successor, S E C R E T A R Y O F T H E U N IT E D

S T A T E S D E P A R T M E N T O F H E A L T H AND HUMAN S E R V IC E S ,

R espondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

V i c t o r A . K o v n e r

C orporation Counsel fo r the

City o f N ew York

100 Church Street

New York, New York 10007

(212) 374-3171

L e o n a r d J . K o e r n e r

L o r n a B a d e G o o d m a n

G a i l R u b i n

H i l l a r y W e i s m a n

Assistant C orporation Counsels

Attorneys fo r Petitioners

T he City o f N ew York and

T he N ew York City H ealth and

H ospitals C orporation

R o b e r t A b r a m s

A ttorney G eneral o f the

State o f N ew York

120 Broadway

New York, New York 10271

(212) 341-2240

O . P e t e r S h e r w o o d

Solicitor G eneral

S u z a n n e M . L y n n

Assistant A ttorney G en eral

C hief, Civil Rights Bureau

(Counsel o f R ecord )

D o n n a I . D e n n i s

C y n t h i a F . K r e u s i

S a n f o r d M . C o h e n

Assistant A ttorneys G en eral

A ttorneys fo r P etitioner

The State o f N ew York

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Do new regulations promulgated by DHHS under Title

X of the Public Health Service Act which prohibit abortion

counseling, referral and advocacy in programs funded under

the Act and require physical separation of Title X-funded

facilities from facilities engaging in abortion-related services,

violate the First Amendment?

2. Does the regulations’ prohibition of abortion counseling

and referral in a Title X-funded program violate the woman’s

constitutionally protected privacy right to make a fully informed

decision on whether or not to continue her pregnancy?

3. Do the regulations’ ban on abortion counseling and refer

ral in Tide X-funded programs and the requirement of physical

separation violate congressional intent underlying Title X?

4. Are the new regulations arbitrary and capricious because

they reverse longstanding agency policy in the absence of any

intervening change in circumstances and because the change

in policy was unquestionably politically motivated?

11

PARTIES

The parties to the proceeding in the United States Court of

Appeals for the Second Circuit are:

1. The State of New York, the City of New York and the New

York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, plaintiffs-

appellants in the court below.

2. Dr. Louis Sullivan, as Secretary of the United States

Department of Health and Human Services, defendant-appellee

in the court below.1

' Pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. Rule 43(c), Dr. Sullivan was substituted for Otis

R. Rowen, who was Secretary of Health and Human Services at the time this

action was filed.

I l l

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Presented for R ev iew .................................. i

P arties.................................................................................... ii

Table of Authorities......................................................... vii

Opinions B elow .................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction........................................................................... 2

Constitutional, Statutory and Regulatory

Provisions Involved............................................................... 2

Statement of the Case ............................................................. 3

Summary of Argument............................................................. 8

A rgum ent..................................................................................... 10

I. THE REGULATIONS EXCEED HHS’

STATUTORY AUTHORITY AND ARE

ARBITRARY AND C A PR IC IO U S............................... 10

A. The Regulations Prohibiting Abortion

Counseling and Referral Are Contrary To

The Intent Of Congress As Well As

Arbitrary And C apricious........................................ 11

1. The Regulations Are Contrary To The

Plain Language Of Section 1008 Of

Title X ................................................................... 11 2

2. The Legislative History of Section

1008 Is Consistent With Its Plain

M eaning ................................................................. 14

a. Contemporaneous H isto ry ...................... 14

b. Subsequent H istory ................................... 16

Page

IV

Page

3. The Regulations Are Entitled To Little

D eference...................................................... 19

4. The Regulations Are Arbitrary And

Capricious .................................................... 23

B. The Requirement Of Physical And

Financial Separation In Section 59.9 Of

The Regulations Is Both Contrary To The

Intent Of Congress And Arbitrary And

C apricious............................................................. 26

1. Congress Did Not Authorize The

Physical Separation Requirem ent......... 26

2. The Physical Separation Requirement

Is U njustified............................................... 30

c. The Regulations Raise Serious

Constitutional Problems For Title X ........... 31

II. THE REGULATIONS ARE

U N CO N STITU TIO N A L......................................... 32

A. The Regulations Violate First Amendment

R ights...................................................................... 32

1. Section 59.8 Contains Content-and

View-Point Based Discriminatory

Restrictions On Speech In Violation

Of The First A m endm ent....................... 32

2. Section 59.10 Is A Viewpoint

Discriminatory Restriction On Speech

That Violates The First Amendment . . 41

3. Section 59.9 Violates The First

Amendment By Burdening Non-Title

X Funded Speech ....................................... 42

V

Page

B. Section 59.8 Violates The Woman’s

Constitutional Privacy Right to Decide

Whether To Continue Her Pregnancy . . . . 47

Conclusion........................................................................... 50

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

A lbem arle Paper Co. v. M oody, 422 U.S. 405

(1 9 7 5 ) ................................................................................ 22

A m erican Council o f the Blind v. Boorstin, 644 F.

Supp. 811 (D .D .C . 1986) ......................................... 39

Andrus v. G lover Constr. C o ., 446 U.S. 608

(1 9 8 0 ) ............................................................................... 11, 12

Arkansas Writers' Project v. Ragland, 481 U.S.

221 (1987) ...................................................................... 38, 40

Austin v. M ichigan C ham ber o f C om m erce, 110

S. Ct. 1391 (1990) ....................................................... 45

B ecker v. Schw artz, 46 N.Y.2d 401, 413 N.Y.S.2d

895, 386 N .E.2d 807 (1978) ..................................... 43

Bethesda H ospital Ass’n v. Bow en, 108 S. Ct.

1255 (1988) .................................................................... 11

Bd. o f Educ. v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1 9 8 2 ).............. 36

Bd. o f Governers o f th e F edera l Reserve System v.

Dim ension Financial C orp ., 474 U.S. 361

(1 9 8 6 ) ................................................................................ 19

Blum v. Yaretsky, 457 U.S. 991 (1 9 8 2 ).................... 37

B ob Jon es Univ. v. United States, 461 U.S. 374

(1 9 8 3 ) ................................................................................ 17

Boos v. Barry, 108 S. Ct. 1157 (1988)....................... 34

Bow en v. A m erican Hosp. Ass'n, 476 U.S. 610

(1 9 8 6 ) ................................................................................ 19, 20,

23, 27

V II

Cases Page

V l l l

Burlington Truck Lines, Inc. v. United States,

371 U.S. 156 (1 9 6 2 ) .................................................... 23

Canterbury v. Spence, 464 F.2d 772 (D.C. Cir.),

cert, den ied , 409 U.S. 1064 (1972) ....................... 32

Carey v. Population Services In t i , 431 U.S. 678

(1 9 7 7 ) ............................................................................... 41

Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. N ational Resources

D efense Council, 467 U.S. 837 (1984).................. 19, 26

Chrysler Corp. v. Brow n, 441 U.S. 281 (1978) . . . 16

City o f Akron v. Akron Center fo r R eproductive

H ealth , 462 U.S. 416 (1 9 8 3 ).................................... passim

C om m odity Futures Trading C om m ’n v. Schor,

478 U.S. 833 (1 9 8 6 ) .................................................... 20

C onsolidated Edison Co. v. Pub. Serv. C om m ’n,

447 U.S. 530 (1 9 8 0 ) .................................................... 34, 38

Consum er Product Safety C om m ’n v. GTE

Sylvania, In c ., 447 U.S. 102 (1980)....................... 12, 16

Cornelius v. NAACP L eg a l D efense and

Education Fund, 473 U.S. 788 (1985).................. 39

Cruzan v. Missouri D ep ’t o f H ealth, 58 U .S.L .W .

4916 (June 25, 1990) .................................................. 32

D eBartolo C orp. v. F lorida G u lf Coast Bldg, and

Constr., 108 S. Ct. 1392 (1 9 8 8 ).............................. 31

D oe v. Bolton , 410 U.S. 179 (1973)........................... 49

D ole v. United States Steelw orkers o f A m erica,

110 S. Ct. 929 (1990).................................................. 11, 19

Page

IX

EEO C v. Associated Dry G oods C orp ., 449 U.S.

590 (1981) ....................................................................... 20

FC C v. L eagu e o f W om en Voters, 468 U.S. 364

(1 9 8 4 ) ................................................................................ 35, 38,

39

FE C v. M assachusetts Citizens fo r L ife , In c ., 479

U.S. 238 (1 9 8 6 ).............................................................. 45

F edera l Energy Regulatory C om m ’n v.

Mississippi, 456 U.S. 742 (1982)............................. 37

G eneral E lec. Co. v. G ilbert, 429 U.S. 125 (1976) 22

G reen v. Bock Laundry M ach. C o ., 109 S. Ct.

1981 (1989) .................................................................... 11

G risw old v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 ( 1 9 6 5 ) . . . . 32

G rove City C ollege v. Bell, 465 U.S. 555 (1 9 8 4 ).. 18

Harris v. M cR ae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980) ..................... 38, 47

H illsborough County v. A utom ated M edical

Laboratories, In c., 471 U.S. 707 (1 9 8 5 ) .............. 27

H obb ie v. U nem ploym ent A ppeals C om m ’n o f

F lorida, 480 U.S. 136 (1987) ..................................... 46

H offson v. O rentreich, 144 Misc. 2d 411 (Sup.

Ct. N.Y. Co. 1989)....................................................... 32

I.N .S. v. C ardoza-Fonseca, 480 U.S. 421 (1987) . . 11, 19

K M art Corp. v. C artier, In c ., 108 S. Ct. 1811

(1 9 8 8 ) ................................................................................ 11

Kleindienst v. M andel, 408 U.S. 753 (1972)............. 36

Page

X

L in dah l v. O ffice o f Personnel M anagem ent, 470

U.S. 768 (1985 )............................................................. 16

L u khard v. R eed , 481 U.S. 368 (1 9 8 7 ) .................... 12

Lyng v. In t i Union, United Auto W orkers, 485

U.S. 360 (1988 )............................................................. 47

M aher v. R oe, 432 U.S. 464 (1 9 7 7 )........................... 37, 38,

47

M assachusetts v. Bow en, 679 F. Supp. 137 (D.

Mass. 1988) .................................................................... 7, 45

M assachusetts v. S ecy o f H ealth and Human

Services, 899 F.2d 53 (1st Cir. 1990).................... passim

M otor V ehicle M anufacturers Ass’n v. State Farm

Mut. Auto. Ins., 463 U.S. 29 (1 9 8 3 ) .................... passim

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1 9 6 3 ) .................. 45

N ational Ass’n o f Greeting Card Publishers v.

United States Postal Services, 462 U.S. 810

(1 9 8 3 ) ............................................................................... 14

N ew York v. Bow en, 690 F. Supp. 1261

(S.D.N.Y. 1988) ........................................................... 1, 7, 42

N ew York v. Sullivan, 889 F.2d 401 (2d Cir.

1 9 89 ).................................................................................. passim

N LRB v. A erospace C o ., 416 U.S. 267 (1974) . . . . 16

N LRB v. Drivers, 362 U.S. 274 (1 9 6 0 ) ......................... 31

N LRB v. United F ood and C om m ercial W orkers

Union, 484 U.S. 112 (1987)....................................... 19, 20

North Haven Bd. o f Educ. v. Bell, 456 U.S. 512

(1 9 8 2 ) ................................................................................ 16

Page

XI

Perry v. Sindermann, 408 U.S. 593 (1972 ).............. 46

Perry Educ. Ass’n v. Perry L oca l E ducators’ Ass’n,

460 U.S. 37 (1 9 8 3 ) ....................................................... 39

Piedm ont ir Northern Ry. v. Com m ission, 286

U.S. 299 (1 9 3 2 )............................................................. 13

Pittson C oal Group v. Sebben , 109 S. Ct. 414

(1 9 8 8 ) ................................................................................ 12

Planned Parenthood Ass’n - C hicago Area v.

K em piners, 531 F. Supp. 320 (N.D. 111. 1981)

vacated and rem anded on other grounds, 700

F.2d 1115 (7th Cir. 1983), on rem and, 568 F.

Supp. 1490 (N.D. 111. 1 9 8 3 ) .................................... 40, 46

Planned Parenthood o f Cent. <b No. Arizona v.

Arizona, 718 F.2d 938 (9th Cir. 1983) appeal

a fter rem and, 789 F.2d 1348 (9th Cir.), a f f ’d

sub nom . B abbitt v. Planned P arenthood, 479

U.S. 925 (1 9 8 6 )............................................................. 46

Planned Parenthood o f Central Missouri v.

D anforth , 428 U.S. 52 (1975 ).................................. 34

Planned P arenthood F e d ’n o f Am. v. Bow en , 680

F. Supp. 1965 (D. Colo. 1988), ap p ea l pending

(10th C i r . ) ....................................................................... 7

Regan v. Taxation w ith R epresentation , 461 U.S.

540 (1983) ....................................................................... 35, 37,

38, 39,

41, 44,

45

R endell-B aker v. K ohn, 457 U.S. 830 (1 9 8 2 ) ........ 37

R oe v. W ade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) ........................... 47, 48

Rust v. Bow en , 690 F. Supp. 1261 (S.D.N.Y.

1 9 8 8 ).................................................................................. 7

Page

XU

S chloendorff v. Society o f New York H ospital, 211

N.Y. 125, 105 N.E. 92 (1914).................................... 32

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963).................. 46

Speiser v. R andall, 357 U.S. 513 (1 9 5 8 ) .................. 46

Sullivan v. Z ebley, 110 S. Ct. 885 (1990)................ 30

Thornburgh v. A m erican C ollege o f Obstetricians

i? Gynecologists, 476 U.S. 747 (1986 ).................. 34, 47,

48

T rafficante v. M etropolitan L ife Ins. C o., 409

U.S. 205 (1 9 7 2 )............................................................. 20

United States v. K okinda, 58 U .S.L .W . 5013

(June 27, 1 9 9 0 ) ............................................................. 39

United States v. R utherford, 442 U.S. 544 (1979) . 17

United States Postal Service v. Council o f

G reenburgh Civic Assn., 453 U.S. 114 (1981) . . 39

Valley Fam ily Planning v. North D akota, 489 F.

Supp. 238 (D.N.D. 1980), a f f ’d on other

grounds, 661 F.2d 99 (8th Cir. 1 9 8 1 ) .................. 14, 46

Village o f H offm an Estates, 455 U.S. 489 (1982) . 45

Virginia State Bd. o f Pharm acy v. Virginia

Citizens Consum er Council, In c ., 425 U.S. 748

(1 9 7 6 ) ................................................................................ 36

W ebster v. R eproductive H ealth Services, 109 S.

Ct. 3040 (1 9 8 9 )............................................................. 38, 39,

47

W halen v. R oe, 429 U.S. 589 (1977 )......................... 47, 49

W ooley v. M aynard, 430 U.S. 705 (1977) ............. 34

Z auderer v. O ffice o f D isciplinary Counsel, 471

U.S. 626 (1 9 8 5 )............................................................. 36

Page

X IU

Federal Statutes, Regulations, Guidelines, and Rules

28 U .S.C . § 1 2 5 4 (1 )......................................................... 2

42 U .S.C . § 3 0 0 (a ) ........................................................... 2, 11, 37

42 U .S.C . § 300a ( a ) ......................................................... 2, 26

42 U .S.C . § 300a-3(a) .................................................... 3

42 U .S.C . § 300a-4(a),(c) .............................................. 3, 4, 8,

42

42 U .S.C . § 300a-6 ........................................................... 2 , 5 , 8 ,

12

42 U .S.C . § 701 ................................................................ 43

42 U.S.C.A . § 300(a) (West 1 9 8 2 ) .............................. 3, 17

42 U.S.C.A . §300z-10 (West 1982) ........................... 13

Pub. L. No. 91-572 §2(1), 84 Stat. 1504 (1970) . . 27

Pub. L. No. 93-45, 87 Stat. 91 (1973)....... 17

Pub. L. No. 94-63, 89 Stat. 304 (1975)..... 17

Pub. L. No. 95-83, 91 Stat. 383 (1977)..... 18

Pub. L. No. 95-613, 92 Stat. 3093 (1978)................ 18

Pub. L. No. 97-35, 95 Stat. 358 (1981)..................... 18

Pub. L . No. 98-512, 98 Stat. 2409 (1984)................ 18

53 Fed. Reg. 2922-44 (Preamble to Regulations)

(1988) ................................................................................ passim

52 Fed. Reg. 33212 §59.8(a) (1987)........................... 25

37 Fed. Reg. 26594 (1972)

Page

21

XIV

36 Fed. Reg. 18465 §§ 59.5 (1 9 7 1 ) ........................... 20, 21

42 C .F .R . §§ 59.2, 59.5, 59.7, 59.8, 59.9, 59.10

(1 9 8 8 ) ............................................................................... passim

U.S. D ep ’t o f H E W Program Guidelines fo r

Project Grants f o r Fam ily Planning Services § §

7.4, 8.0, 8 .6 , 9.4 (1981) ........................................... 4, 5, 6,

22

U.S. D ep ’t o f H E W Program G uidelines fo r

Project Grants fo r Fam ily Planning Services

(1 9 7 6 ) ............................................................................... 22

State Statutes

N.Y.S. Educ. Law §§ 6506-6509 (McKinney 1985) . . 43

N.Y.S. Pub. Health Law § 2800 (McKinney 1985) . . 43

N.Y.S. Pub. Health Law § 2805-d(l) (McKinney

1 9 85).................................................................................. 43

N.Y.S. Pub. Health Law § 2807-b (McKinney

1985).................................................................................. 27

N.Y. Comp. Codes R. & Regs. tit. 8 § 29.2 (1989) . 43

N.Y. Comp. Codes R. & Regs. tit. 10 § § 751.4,

751.9 (1987) .................................................................... 32, 43

Legislative History and Hearings

S. Rep. No. 1004, 91st Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted

in 116 Cong. Rec. 24094 (1970)................................. 14

S. Rep. No. 29, 94th Cong., 1st Sess., reprinted in

1975 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 469 . . . . 17

Page

XV

S. Rep. No. 63, 94th Cong., 1st Sess., reprinted,

in 1975 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 469,

528 .................................................................................... 28

S. Rep. No. 822, 95th Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted

in 124 Cong. Rec. 16454 (1978).............................. 18

H.R. Rep. No. 1472, 91st Cong., 2d Sess.,

reprinted in 1970 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin.

News 5068, 5 0 7 4 ........................................................... 14, 27

H.R. Rep. No. 161, 93d Cong., 2d Sess. (1974) . . 28

H.R. Rep. No. 1161, 93d Cong., 2d Sess. (1974) . 17, 28

H.R. Rep. No. 118, 95th Cong., 1st Sess (1977) . . 28

H.R. Rep. No. 191, 95th Cong., 2d Sess. (1978). . 28

H.R. Rep. No. 159, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. (1985) . 17, 18

H.R. Rep. No. 403, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. (1985) . 19

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 1667, 91st Cong., 2d Sess.,

reprinted in 1970 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin.

News 5081-82 ................................................................ 15, 16

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 1524, 93d Cong., 2d Sess.,

(1 9 7 4 ) ................................................................................ 17, 28

116 Cong. Rec. 37367 (1970) ........................... 15

116 Cong. Rec. 37369 (1 9 7 0 ) ........................... 15

116 Cong. Rec. 37370 (1 9 7 0 ) ........................... 40

116 Cong. Rec. 37375 (1 9 7 0 ) ........................... 16

Page

XVI

116 Cong. Rec. 37379 (1 9 7 0 ) ....................................... 15

116 Cong. Rec. 37381 (1970) ....................................... 4

121 Cong. Rec. 9789-90 (1975).................................... 17

124 Cong. Rec. 31241-44 (1978).................................. 29

124 Cong. Rec. 37046 (1978) ....................................... 28, 29

Administrative Materials

Memorandum from J. Mangel, Deputy Assistant

General Counsel to L. Heilman, M .D ., Deputy

Assistant Secretary for Population Affairs (April

20, 1971) ......................................................................... 21, 29

National Center for Family Planning Services,

Health Services and Mental Health

Administration, Department of Health

Education and Welfare, A Five-Y ear Plan fo r

the D elivery o f Fam ily Planning Services

(October 1971) ............................................................. 13, 21

Memorandum from C. Conrad, Sr. Atty., Pub.

Health D iv., to E. Sullivan, Office for Family

Planning, (April 14, 1978)......................................... 20, 22

Memorandum from C. Conrad, Sr. Atty., Pub.

Health D iv., to E. Sullivan, Office for Family

Planning, (July 15, 1979)............................................. 20, 22

Memorandum from L. Belmonte, Regional

Program Consultant, Office for Family

Planning (May 25, 1 9 7 4 ) ........................................... 22

Memorandum from L. Heilman, Md., Deputy

Assistant Sec’y for Population Affairs to H.

Connor, M .D ., Regional Health Adm’r

(November 19, 1 9 7 6 ) .................................................. 20, 22

Page

XVII

General Accounting Office, Restrictions on

A bortion and L obby in g Activities in Fam ily

Planning Program N eed C larification (1982) . . . passim

Articles

J.D . Forrest, “The Delivery of Family Planning”

Services in the United States”, 20 Fam ily

Planning” Perspectives 88 (1987) ........................... 6

Miscellaneous

W ebster’s Third New International D ictionary

(1 9 7 1 ) ................................................................................ 12

Stedm an ’s M edical D ictionary F ifth U nabridged

L aw y er’s Edition (1987)............................................. 12

The Sloane-D orland Annot. M edical-Legal

D ictionary (1 9 8 7 ) ......................................................... 12

D orlan d ’s Illustrated M edical D ictionary (1981) . . 12

Sutherland Statutory Construction § 64.08 (Sands

4th ed. 1 9 8 6 ).................................................................. 13

Current Opinions o f the Council on E th ical and

Ju d ic ia l A ffairs o f the A m erican M edical

Association, Op. 3.04, 8.07 (1986)......................... 13, 34,

35

Letter from Rep. John D. Dingell to Otis R.

Rowen (October 14, 1987)......................................... 16

Letter from Rep. Christopher H. Smith, et. a l.,

to Donald T. Regan (August 1, 1 9 8 6 ).................. 24, 25

Letter from Secretary Otis R. Rowen to Hon. Vin

Weber (August 19, 1986)........................................... 25

Page

No. 89-1392

In the

Bnprtmt Gtourt af tl|t United States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1 9 9 0

T H E ST A T E O F N E W Y O R K , T H E C IT Y O F N EW

Y O R K , T H E N E W Y O R K C IT Y H E A L T H

AND H O SPIT A L S C O R P .,

Petitioners,

vs.

D R . L O U IS SU LLIV A N , or his successor, SE C R E T A R Y

O F T H E U N IT E D S T A T E S D E P A R T M E N T O F

H E A L T H AND HUMAN S E R V IC E S ,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

OPINIONS BELOW

The decision of the district court is reported as New York v.

Bow en , 690 F. Supp. 1261 (S.D.N.Y. 1988), and is reproduced

in the appendix to the petitions for certiorari at 9-32a. The

opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second

Circuit is reported as N ew York v. Sullivan, 889 F.2d 401 (2d

Cir. 1989), and is reproduced in the appendix to the petitions

for certiorari at 35-67a.

2

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

November 1, 1989, and the petition for certiorari was filed pur

suant to 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) on March 1, 1990. The petition was

granted on May 29, 1990. 110 S. Ct. 2559.

CONSTITUTIONAL, STATUTORY, AND

REGULATORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

United States Constitution, Amendment I:

Congress shall make no law. . . abridging the freedom

of speech. . . .

United States Constitution, Amendment V:

No person shall. . . be deprived of life, liberty, or pro

perty, without due process of law. . . .

Title X of the Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. § 300(a):

The Secretary is authorized to make grants to and

enter into contracts. . . to assist in the establishment

and operation of voluntary family planning projects

which shall offer a broad range of acceptable and ef

fective family planning methods and services. . . .

Title X of the Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. § 300a-6:

None of the funds appropriated under this subchapter

shall be used in programs where abortion is a method

of family planning.

Title X of the Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. § 300a(a):

The Secretary is authorized to make grants, from

allotments made under subsection (b) of this section,

to State health authorities to assist in planning,

establishing, m aintaining, coordinating, and

evaluating family planning services. No grant may be

made to a State health authority under this section

unless such authority has submitted, and had

approved by the Secretary, a State plan for a coor

dinated and comprehensive program of family plan

ning services.

3

Title X of the Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. § 300a-3(a):

The Secretary’ is authorized to make grants to public

or nonprofit private entities and to enter into contracts

with public or private entities and individuals to assist

in developing and making available family planning

and population growth information (including educa

tional materials) to all persons desiring such informa

tion (or materials).

Title X of the Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. § 300a-4:

A grant may be made or contract entered into under

section 300 or 300a of this title for a family planning

service project or program only upon assurances

satisfactory to the Secretary that —

(1) priority will be given in such project or pro

gram to the furnishing of such services to per

sons from low-income families; . . .

Grants for Family Planning Services, 42 C.F.R. §§ 59.2, 59.5,

59.7, 59.8, 59.9, 59.10.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The Title X Program and the C hallenged Regulations

In 1970 Congress enacted Title X of the Public Health Serv

ice Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 300-300a-41 (1982), to provide low-income

women with access to family planning services. Title X is the

largest source of federal support for family planning and repro

ductive health care, funding over 3900 clinics nationwide and

serving nearly 4.5 million low-income women per year. See Mor-

ley U 6 (224-25JA).2 In addition to providing information and

education on “a broad range of acceptable and effective . . .

methods” of spacing children, 42 U.S.C.A. § 300(a) (West 1982),

2 Materials appearing in the Joint Appendix to this brief will be referred to as

(“____ JA”). The Appendix is jointly filed by petitioners the State of New York

et al. and by petitioners Rust et al. Materials appearing in the appendix to the

petition for certiorari will be referred to as (“____ a”). Materials appearing in the

appendix to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals will be referred to as (“------ A”).

4

Title X clinics dispense some general medical care and refer pa

tients for all services not provided by the clinics.3

The program was created in “recognition] of a basic human

right, the right to freely determine the size of one’s family, the

timing of one’s children.” 116 Cong. Rec. 37381 (1970). Through

Title X Congress intended to provide access to family planning

services for low-income women so that they could have the same

range of reproductive choice as women of greater means. 42

U.S.C. § 300a-4(c)(l).

Title X has operated successfully for two decades, and is par

ticularly important to the delivery of health care in New York

State,4 serving precisely those women Congress intended to reach.

The overwhelming majority of patients are poor women, most

of whom have incomes below 150 % of the poverty line, Gesche

1 6 (171JA); Henshaw 1 18 (194JA); Fink 1 3 (160JA), and a

substantial portion are adolescents, Gesche 1 7 (171JA). It is a

population in acute need of medical information and services,

suffering from disproportionately high rates of teenage pregnan

cy, infant mortality and sexually transmitted diseases. See , e.g.,

Joseph 11 7, 8 (199JA); Bennett 1 7 (496A); Coombs 1 10

(142-44JA); Morgan 1 4 (218JA).5 But in February 1988, for

3 See HEW, Program Guidelines for Project Grants for Family Planning Ser

vices (1981) §§ 8.3, 9.1-3, 9.4 (35-36A,39A). See 42 C.F.R. § 59.5(b)(1) (1988).

Congress in fact envisioned the Title X clinics as providing an entry point in

to the general health care system, by identifying undiscovered health problems

and by offering referrals for all treatment needs. See 116 Cong. Rec. 37370

(1970) (Statement of Rep. Bush) (222A).

* There are two direct Title X grantees in New York State: the New York State

Department of Health (NYSDOH) and the Medical and Health Research

Association of New York City (MHRA), petitioner in the companion case to

this one. Gesche 1 4(170JA); Fink 1 3(160JA). Together the NYSDOH and

MHRA subgrant Title X funds in excess of $8 million to 40 delegate agencies,

Gesche 11 4-5(170-171JA); Fink 1 4(160JA), which serve approximately 200,000

women throughout the state Gesche 1 6(171JA).

5 In New York’s urban areas, the percentage of women infected with AIDS is

among the highest in the nation. See Joseph 11 7-8 (199JA); Minkoff 11 5-6

(647A). One of every 60 women giving birth in New York City is HIV positive,

with the rate rising to one in 50 in Manhattan and the Bronx. (Gesche Exh. F)

(NYSDOH, Newborn Seroprevalence Study (1988)) (563A). In New York State, in

1988 alone, 2300 HIV-positive women were expected to give birth, with approxi

mately 1000 of these infants being infected by the virus. Gesche 1 1 7 (175JA).

5

blatantly political reasons, the Secretary of HHS promulgated

new regulations that are entirely at odds with the First Amend

ment, constitutional privacy guarantees, and the letter and spirit

of Title X.

Section 1008 of Title X provides: “[n]one of the funds appro

priated under [Title X] shall be used in programs where abortion

is a method of family planning.” 42 U.S.C. § 300a-6. For 17 years,

HHS had consistently interpreted this to mean that Title X pro

viders may not perform abortions, but may, and indeed must,

provide nondirective counseling to pregnant patients. See, e.g .,

1981 Guidelines § 8.6 (71a). In an abrupt about-face, the Secre

tary has reread this section to mean that family planning pro

grams may no longer whisper the word “abortion” to their

patients. Abortion — a legal alternative to an unwanted

pregnancy — may not be mentioned, even in response to a direct

inquiry, in the context of an intimate conference between physi

cian and patient, and even if medically indicated for the in

dividual involved.

In enacting the new regulations, HHS has chosen to stifle the

speech of private health care professionals and the rights of their

patients to receive unbiased medical information. The new

regulations interfere with and damage the doctor-patient rela

tionship on its most basic level, and, in effect, perpetrate a hoax

on a young and vulnerable population.

The Regulations

Section 59.8(a)(1) prohibits all counseling about and referral

for abortion, regardless of the woman’s medical circumstances.

Sections 59.8(a)(2) and (b)(4) require that every pregnant

woman, even the woman who has decided not to continue her

pregnancy, be provided with a “list of available providers that

promote the welfare of the mother and unborn child.” This refer

ral list must include providers who do not perform abortions

— regardless of their medical qualifications — but may not in

clude providers whose “principal business is the provision of

abortions,” § 59.8(a)(3), (b)(3) and (4). The sole exception to

this mandatory referral for prenatal care is when “emergency

care is required.” § 59.8(a)(2). Finally, if a woman asks about

abortion, the regulations tell the provider to advise her that “the

project does not consider abortion an appropriate method of

6

family planning and therefore does not counsel or refer for abor

tion.” §59.8(b)(5).

Section 59.10 further prohibits activities that HHS deems to

“encourage, promote or advocate abortion”, including lobbying

for legislation to increase the availability of abortion, paying dues

to an organization that advocates abortion, or disseminating

educational materials on abortion. Thus, clinics would be barred

from making appointments for pregnant clients with abortion

clinics, § 59.10(b)(2); offering clients a brochure advertising an

abortion dinic, §59.10(b)(l); or discussing abortion in lectures or

workshops on sex education, family planning or reproductive

health. § 59.10(a)(2).

Section 59.9 requires that clinics attain complete physical and

financial separation between approved Title X-funded and disap

proved non-Title X-funded services. The Secretary had always

previously held that § 1008 had no effect on activities funded by

non-Title X sources. Thus, grantees were permitted to use private

funds for other activities, including the provision of abortions,

without the necessity of any physical separation. Under the new

regulations, the Secretary is to look at various factors such as

the existence of separate treatment, examination and waiting

rooms and separate personnel, to determine on an ad hoc basis

whether programs have achieved “program integrity”.

For many low income women, Title X clinics are the sole

source of reproductive care - and sometimes of any land of health

care, as Congress was aware and as HHS has acknowledged.6

Thus, the net effect of the new regulations is censorship: an at

tempt by HHS to prevent poor women, with limited resources,

from finding out about the existence and availability of a

medically and legally acceptable option.

6 See 1981 Guidelines § 9.4. Title X clinics in New York as throughout the

nation serve as one of the few sources of regular health care for poor women.

See Randolph 1 10, 12 (244-45JA); Drisgula 1 18 (153JA); Potteiger 1 16 (91a);

Tiezzi 5 8(a)(94a); Merrens 5 5 (284JA). A 1988 study by the Alan Guttmacher

Institute found that Title X family planning services often constitute the only

link to the general health care system for thousands of poor and teenage

women. J.D. Forrest, “The Delivery of Family Planning Services in the United

States”, 20 Family Planning Perspectives 88 (1987).

7

History o f the Litigation

In February 1988 the State and City of New York sued in the

district court for the Southern District to enjoin the regulations,

alleging that they were contrary to congressional intent underly

ing Title X, that they were arbitrary and capricious, and that

they violated the constitutional privacy rights of women and the

First Amendment rights of women and their health care providers.

Subsequently, it was consolidated with another action simulta

neously brought by various private health care providers and

patients, see Rust v. Bow en, 690 F. Supp. 1261 (S.D.N.Y. 1988).7

On June 30, 1988 the district court granted summary judgment

in favor of HHS and dismissed plaintiffs’ consolidated

complaints.

On November 1, 1989 a divided panel of the court of appeals

affirmed. New York v. Sullivan, 889 F. 2d 401 (2d Cir. 1989).

While recognizing that the regulations were a departure from

longstanding agency policy, the majority found that they were

consistent with the statutory language and legislative intent. Id.

at 407-10. It did not engage in an analysis of whether the regula

tions were arbitrary and capricious. Id. at 410. It also conclud

ed that the regulations did not impermissibly burden women’s

privacy rights. Id . at 410-12. It conceded that the regulations

“may hamper or impede women in exercising their right of

privacy in seeking abortions”, but determined that “the prac

tical effect of such a denial on the availability of such services

is constitutionally irrelevant”. Id. at 411. Similarly, it held that

the ban on abortion counseling, referral and advocacy did not

violate the First Amendment, as the government may refuse to

subsidize the exercise of fundamental rights, including speech,

and it was not viewpoint discriminatory. Id. at 412-14.

7 Two other actions challenging the regulations were filed at about the same

time as the instant one. See Planned Parenthood Fed’n of Am. c. Bowen, 680

F.Supp. 1465 (D. Colo. 1988) (preliminary injunction), 687 F. Supp. 540 (D.

Colo. 1988) (permanent injunction), appeal pending, No. 88-2251 (10th Cir.);

Massachusetts v. Bowen, 679 F. Supp. 137 (D. Mass. 1988), aff’d, Massachusetts

v. Sec’y of Health and Human Services, 899 F.2d 53 (1st Cir. 1990) (en banc).

Both actions resulted in the regulations being stricken on constitutional and

statutory grounds. The decision of the First Circuit, therefore, directly con

flicts with the decision of the Second Circuit.

8

The concurring judge, while finding the regulations to be per

missible under the statute, expressed two concerns: first, that

the separation requirement of § 59.9 authorizes the Secretary

to deny funding based on the non-Title X activities of Title X-

funded personnel and, second, that the compelled concealing

of information about abortions and inadequate referrals would

harm vulnerable patients. Id. at 414-15.

The dissenting judge found that the counseling and referral ban

was viewpoint discriminatory in that it “require[d] the grantee to

emphasize prenatal care and prohibited] it from identifying any

entity as a provider of abortions”. Id. at 416. Moreover, she found

that the content restriction was “all the more pernicious” in that

it deprived women of their right to choose whether or not to have

an abortion. Id. Finally, she concluded that the regulations were

arbitrary and capricious because the turnaround in policy was

not justified by any facts in the record before the agency, and

because it was blatantly political. Id. at 417-18.

On November 21, 1989, the Second Circuit unanimously en

joined enforcement of the regulations and stayed its mandate

pending disposition of the case by this Court (68-69a). Thus,

petitioners continue to receive grant funds under the terms of

the preexisting regulations.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Secretary of HHS, in a dramatic reversal of agency policy,

promulgated new regulations under Title X of the Public Health

Service Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 300-300a-41, purporting to reinter

pret the statute’s prohibition against funding “programs where

abortion is a method of family planning.” 42 U.S.C. § 300a-6

(§ 1008 of the Act). Where former agency policy allowed, and

in fact required, Title X health professionals to counsel preg

nant women on all options including abortion, new § 59.8 for

bids neutral speech about abortion and mandates speech pro

moting prenatal care in the counseling context, while new § 59.10

prohibits other activities by Title X recipients that are deemed

to “encourage, promote or advocate abortion”. Where former

agency policy required only financial separation of Title X

funded and independently funded abortion-related activities,

new § 59.9 mandates that Tide X programs be physically as well

9

as financially separate from facilities engaging in abortion-

related activities. These regulations contravene congressional in

tent underlying Title X, are arbitrary' and capricious, and violate

free speech guarantees of the First Amendment and privacy

guarantees of the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment.

First, the abortion counseling and referral ban goes far beyond

§ 1008, which only forbids funds for the provision of abortions.

Section 1008, on its face and in the context of the statute as a

whole, does not restrict the provision of neutral information

about abortion, and in fact such a restriction would run counter

to the aims of the program to provide high quality reproduc

tive health care to low-income women. Contemporaneous and

subsequent legislative history confirm that in enacting § 1008,

Congress meant only to guard against abortion being used as

a substitute for contraception, and that medically appropriate

counseling and referral services were to be included as part of

the “comprehensive family planning services” offered under Tide

X. The prior history of administrative enforcement demonstrates,

too, that § 1008 was not intended to prevent the provision of

truthful information about abortion.

The physical separation requirement similarly contravenes

congressional intent. Congress repeatedly expressed its belief that

Title X services were best offered in an integrated health set

ting, i.e., coordinated with providers of other health care ser

vices. Physical separation undermines that intent by requiring

cosdy duplication of resources, or even closings of facilities, thus

reducing clinics’ ability to serve their intended patients.

Second, the regulations are arbitrary and capricious because

they are not the result of any intervening change in cir

cumstances, are not rationally related to the evidence before

the agency, and have been conceded by the Secretary to be

politically motivated.

Third, the regulations are unconstitutional. By suppressing

speech about abortion and mandating speech about prenatal

care in the informed consent dialogue, the Secretary has im

permissibly infringed upon the First Amendment rights of the

physician and the patient. The counseling, referral and advocacy

ban is unquestionably viewpoint-discriminatory, censoring any

1 0

speech about abortion which is neutral or nonpejorative and

compelling pro-childbirth speech. Because the counseling and

referral bans are “aimed at the suppression of dangerous ideas”,

they are not saved by the fact that they are in the guise of a

government funding decision. The separation requirement like

wise violates free speech guarantees by impermissibly burdening

the independently-funded expressive activities of Title X

grantees.

Lastly, the counseling and referral bans impermissibly in

terfere with the woman’s privacy right to make a fully informed

decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy. Speech

restrictions such as these do not merely leave the woman in the

same position as if there were no funded family planning

services, but affirmatively mislead her, and erect obstacles to

the exercise of her constitutional rights.

ARGUMENT

I. THE REGULATIONS EXCEED HHS’ STATUTORY

AUTHORITY AND ARE ARBITRARY AND

CAPRICIOUS

For 17 years following enactment, the Secretary has im

plemented Title X in full recognition of the fact that Congress,

while not intending to fund abortions, expected that women

using Title X funded facilities might receive counseling and refer

ral for abortion, and that Title X funding for family planning

services would be an integral part of programs by states, localities

and private entities to provide such services. The Secretary also

recognized that the limitation on Title X funding of abortion

should in no way limit or interfere with the programs with which

the Title X funded program was to be coordinated, even if the

non-Title X funded programs provided for abortion. The

Secretary has now abandoned these understandings of his

responsibilities under Title X. In promulgating the new regula

tions, he has exceeded his authority and violated virtually every

established principle of statutory construction.

1 1

A. The Regulations Prohibiting Abortion Counseling And

Referral Are Contrary To The Intent Of Congress As Well

As Arbitrary And Capricious

1. The Regulations Are Contrary To The Plain

Language o f Section 1008 o f Title X

The starting point for interpreting a statute is its language.

Because the Court assumes that the ordinary meaning of the words

used expresses the legislative purpose, the language of the statute

is conclusive unless there is clearly expressed legislative intent to

the contrary. I.N.S. v. Cardoza-Fonseca, 480 U.S. 421, 432 (1987).

In discerning the plain meaning of the statute, the Court must

look not only at “the particular statutory language at issue” but

also at “the language and design of the statute as a whole.”

K M art Corp. v. Cartier, Inc., 108 S. Ct. 1811, 1817 (1988); see

also Bethesda Hosp. Ass’n v. Bowen, 485 U.S. 399, 405-06 (1988);

Dole v. United Steelworkers o f America, 110 S.Ct. 929, 935 (1990).8

Considered on its own and in the context of Title X as a whole,

the text of § 1008 provides a fully sufficient basis for deciding

this case. Under Title X, the Secretary is empowered to make

grants and enter into contracts “to assist in the establishment and

operation of voluntary family planning projects which shall offer

a broad range of acceptable and effective family planning m eth

ods and services .” 42 U.S.C. § 300(a). (emphasis added). With

§ 1008, Congress addressed the place of abortion within Title X

8 The court of appeals below failed to heed basic principles of statutory con

struction when it concluded that § 1008 “specifically excludes” counseling and

referral for abortion from the scope of Title X. New York v. Sullivan, 889 F.2d

at 408. Nowhere in § 1008, or in the statute as a whole, is abortion counseling

and referral “specifically excluded”. On the contrary, the only category specifi

cally excluded by § 1008 is the “method” of “abortion” and not talk about abor

tion. Second, the Second Circuit failed to consider the “ordinary usage”, see

Green v. Bock Laundry Mach. Co., 109 S. Ct. 1981, 1994 (1989) (Scalia, J.,

concurring), of the terms “method of family planning” and “abortion.” Third,

the Second Circuit's overly broad reading of § 1008 contravenes the rule that

additional statutory exceptions should not be implied where certain exceptions

have been explicitly enumerated. Andrus v. Glover Constr. Co., 446 U.S. 608,

616-17 (1980). Finally, the Second Circuit failed to construe § 1008 in con

junction with the statute as a whole, see K Mart, 108 S. Ct. at 1817, by not

honoring the statutory distinction between “methods” and “services.”

12

in clear, precise language. As an exception to “the broad range

of acceptable and effective family planning methods and ser

vices” that Title X recipients were required to offer, § 1008 states:

“None of the funds appropriated under this subchapter shall

be used in programs where abortion is a m ethod of family plan

ning.” 42 U.S.C. § 300 a-6 (emphasis added).

Taken alone, the words of § 1008 denote only that Congress

wanted to exclude the abortion procedure from the range of fami

ly planning methods funded under Title X. The word “abortion”

commonly refers in both general and medical usage to the act or

procedure of terminating a pregnancy.9 See Webster's Third New

International Dictionary 5 (1971); Stedm an’s M edical Dictionary

Fifth Unabridged L aw yer’s Edition 3-4 (1987). A “method” is “a

procedure or process for attaining an object.” See W ebster’s 1422-

23. Likewise, in the medical community, the term “method” refers

to a procedure or technique, and in particular to the procedure

of an operation. See The Sloane-D orland A nnotated M edical —

L egal D ictionary 448 (1987) (“method” defined as “the manner

of performing any act or operation; a procedure or technique”);

see also D orland’s Illustrated M edical D ictionary 808 (1981);

Stedm an’s 867. Thus, in their ordinary context, the words of

§ 1008 spell out a restriction on the funding of a particular pro

cedure, that is, abortion. It does not set forth an additional re

striction on the mere provision of information relating to abortion.

Moreover, by requiring Title X programs to provide both fami

ly planning “methods” and “services,” Congress treated the two

as distinct concepts. Section 1008 excludes only a particular fami

ly planning m ethod — abortion — from the Act’s scope Nothing

in the statute authorizes a similar restriction on the range of

comprehensive family planning “services” to be provided. When,

as here, Congress explicitly enumerated certain exceptions, this

Court has often refused to enlarge the list by implication. See,

e.g ., Consum er Product Safety C om m ’n v. G TE Sylvania, Inc.,

447 U.S. 102, 109 (1980); Andrus v. G lover Constr. Co., 446 U.S.

608, 616-17 (1980). Had Congress wished to exclude abortion

• It is appropriate for the Court to consider dictionary definitions of the words

Congress used. See, e.g., Pittson Coal Group v. Sebben, 109 S. Ct. 414, 420

(1988); Lukhard v. Reed, 481 U.S. 368, 374-75 (1987).

13

counseling and referral from its scope, it certainly could have

made its intention known. See, e.g., Adolescent Family Life Act,

42 U.S.C.A. § 300 z-10 (West 1982).

The rule of narrow construction of statutory exceptions is par

ticularly apt in interpreting a remedial statute, Piedmont 6- North

ern Ry. Co. v. Commission, 286 U.S. 299, 311-12 (1932), see also

3 Sutherland Statutory Construction § 64.08 at 217 (Sands 4th

ed. 1986) (grant-in-aid statutes remedial in character), especially

where it has been carefully crafted to effectuate a delicate com

promise. Thus, while the statute expresses a preference for

preventive family planning over abortion, it leaves Title X physi

cians free to provide a full range of acceptable and effective fami

ly planning services. A medically appropriate family planning

program must offer counseling and referral services, including

counseling and referral for abortion. See Current Opinions o f

the Council on Ethical and Judicial A ffairs o f the American

M edical Association Op. 8.07 (1986). Sammons H 3 (261JA).

The regulations conflict with the plain meaning of § 1008 in yet

another way. They interpret “programs where abortion is a meth

od of family planning” to embrace programs where any form of

counseling or referral for abortion takes place. Yet it is clear that

Congress was concerned with the specific possibility of funding

abortions as a substitute for preventive family planning, not with

the possibility of providing information about any and all uses of

abortion.10 In departing from the plain meaning of § 1008, the

Secretary has fundamentally misconstrued congressional intent.0

10 Congressional fears of abortion becoming a method of family planning were

never borne out. There is no evidence that Title X providers have ever counseled

pregnancy termination as a “family planning option” equivalent to diaphragms,

intrauterine devices (IUD’s), or oral contraceptives. Instead, Title X programs,

like all high quality providers of reproductive health services, treat abortion

as a backup to contraceptive or human failure and as an option when pregnan

cy termination is medically indicated. See, e.g., Felton 5 13a (88a); see also

Rust 1 17a (254-55JA); Tiezzi 1 8a (272-73JA).

u Until recently, HHS heeded the words of § 1008 when interpreting that pro

vision. See National Center for Family Planning Services, Health Services and

Mental Health Administration, Dep't of HEW, A Five-Year Plan for the

Delivery of Family Planning Services, (Oct. 1971) (“Within the context of

(Footnote continued)

14

2. The Legislative History o f Section 1008 Is Consist

ent W ith Its Plain M eaning

a. Contem poraneous History

Congress’ intention that the services provided by Title X grantees

be broad in scope permeates the legislative history. For example,

a contemporaneous Senate Report states that the legislation’s

purpose is “to make comprehensive, voluntary family planning

services” available to all persons who desire them. S. Rep. No.

1004, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 3, reprinted in 116 Cong. Rec. 24094

(1970). This Report also emphasizes that “family planning [is

not] merely a euphemism for birth control. It is properly a part

of comprehensive health care and should consist of much more

than the dispensation of contraceptive devices.” Id. at 24095-96.

The legislative sources also reveal that Congress specifically

intended the comprehensive services funded by Title X to include

counseling and referral. Thus, the Senate Report declares that

a “successful family planning program” must offer “[mjedical

services” that include “consultation, examination, prescription,

and continuing supervision, supplies, instruction, and referral to

other m edical services as needed.” S. Rep. No. 1004, 91st Cong.,

2d Sess. 10, reprinted in 116 Cong. Rec. 24094, 24096 (1970) (em

phasis added). Similarly, the House Report accompanying the le

gislation, under the heading “Services,” anticipates: “In all pro

jects, inform ation would be provided on the fu ll range o f fam ily

planning m ethods. . . .” H.R. Rep. No. 1472, 91st Cong., 2d Sess.

10, reprinted in 1970 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 5068,

5074 (emphasis added).

The Conference Report, a legislative source entitled to great

weight, N ational Ass’n o f Greeting Card Publishers v. United

family planning service programs, abortions are not viewed as a method of

fertility control, but as a service that should be available in accordance with

local laws only in the event of a human or contraceptive failure”) (41-42JA);

see also Memorandum from H EW (July 25, 1979) (Attachment A to Amicus

Brief for HHS, Valley Family Planning v. North Dakota, 661 F.2d 99 (8th Cir.

1981) (No. 80-1471). (“Indeed, we think that where such a referral [for abor

tion] is necessary because of medical indications, abortion is not being con

sidered as a method of family planning at all, but rather as a medical treat

ment possibly required by the patient’s condition...”) (73a).

15

States Postal Serv., 462 U.S. 810, 832 n.28 (1983), confirms that

§ 1008 is a narrow prohibition, not intended to interfere with

Title X ’s expansive scope:

It is, and has been, the intent of both Houses that the

funds authorized under this legislation be used only

to support preventive family planning services,

population research, infertility services, and other

related m edical, in form ational, and educational a c

tivities. The conferees have adopted the language con

tained in § 1008, which prohibits the use of such funds

fo r abortion , in order to make clear this intent.

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 1667, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 8-9, reprinted in

1970 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 5081-82 (emphasis added).

Moreover, the floor statement by Representative Dingell, author

of § 1008, establishes that it was directed only at the abortion

procedure. Rep. Dingell explains that he designed § 1008 to prevent

Title X, through operation of the Supremacy Clause, from becoming

the vehicle through which that procedure was legalized nationwide:

The criminal codes of most States sanction abortion

only in certain strict and clearly-circumscribed cases.

Even the broadest interpretation of these laws would

not lead one to the conclusion that they in any way

allow for such a procedure as an accepted method of

family planning. For the Congress o f the United States

to appropriate funds fo r a procedure w hich w ould

violate the criminal law o f a vast majority o f American

jurisdictions would b e to raise constitutional questions

o f a m ost serious n atu re . . . .

116 Cong. Rec. 37369 (1970); See also id. at 37367“

“ Rep. Dingell’s remarks also indicate that he did not offer § 1008 in order

to curtail medically necessary abortions. 116 Cong. Rec. at 37379 n. 64. If

Rep. Dingell viewed medically necessary abortions as outside § 1008’s pro

scription, he surely could not have viewed counseling and referral for medically

necessary abortions as forbidden by the Act.

The Secretary has cited an isolated statement made on the floor by Rep.

Dingell in which he referred to the Committee’s intent that “abortion is not to

(Footnote continued)

1 6

In addition, the Conference Report establishes that § 1008 was

not intended to restrict the use by Title X projects of non-Title

X funds. The Report is emphatic: “[Section 1008] does not and

is not intended to interfere with or limit programs conducted

in accordance with State or local laws and regulations which are

supported by funds other than those authorized under this legisla

tion.” H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 1667, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 8-9, reported

in 1970 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 5082. By defining §

1008 to apply to “all activities conducted by the federally funded

project,” Pr., 53 Fed. Reg. 2922 (317A), whether the activities are

federally or non-federally funded, the regulation barring all abor

tion information contravenes this directive not to burden

separately-funded activities.

b. Subsequent History

Postenactment legislative history, while not accorded the weight

of contemporary legislative history, can provide evidence of

legislative intent in some circumstances. North Haven Bd. o f

Educ. v. Bell, 456 U.S. 512, 530-35 (1982). One of these cir

cumstances is congressional reenactment without change of a

statute that has been the subject of an administrative interpreta

tion. NLRB v. Aerospace Co., 416 U.S. 267, 274-75 (1974). “ ‘Con

gress is presumed to be aware of an administrative or judicial

interpretation of a statute and to adopt that interpretation when

it reenacts a statute without change’ ”. Lindahl v. O ffice o f Per

sonnel Management, 470 U.S. 768, 782 n.15 (1985) (citations omit

ted). An agency is presumed to have correctly discerned legislative

intent when Congress reenacts a statute after the agency’s con

struction has been “fully brought to [its] attention,” North Haven,

456 U.S. at 535; and an agency’s interpretation is entitled to

be encouraged or promoted in any way through this legislation.” 116 Cong.

Rec. 37375 (1970), cited in Pr., 53 Fed. Reg. 2923 (318A). Nothing in Rep.

Dingell’s lengthy statement, however, suggests an intent to prohibit the pro

vision of neutral, objective abortion information and referral services.

Moreover, in comments on the new regulations, he abjured any intent to bar

counseling and referral for abortion, and chastised the Secretary for “misusing]

. . . my floor statement from the debate.” Letter from John D. Dingell to Otis

R. Bowen (Oct. 14, 1987) (137-39JA).

At any rate, even the contemporaneous remarks of a legislator who spon

sors a bill are not controlling in analyzing legislative history. Consumer Prod

uct, 447 U.S. at 118; Chrysler Corp. v. Brown, 441 U.S. 281, 311 (1979).

17

substantial deference especially when it “involves issues of con

siderable public controversy.” United States v. Rutherford, 442 U.S.

544, 554 (1979). Both enhancing factors are present in this case

Few issues have been as closely followed and hotly debated,

in and out of Congress, as abortion. In that sense, this case

resembles Bob Jones Univ. v. United States, 461 U.S. 574, 599-601

(1983), in which this Court viewed Congress’s failure to modify

Internal Revenue Service rulings on racially discriminatory

schools as ratification of the rulings. Consequently, Title X has

been the subject of unusually close scrutiny by members of Con

gress. See, e.g ., 121 Cong. Rec. 9790 (1975) (“The Committee

has also been watching the administration of these programs

very closely.”) (statement of Sen. Cranston). Congress also has

repeatedly been made aware through annual agency reports13

and General Accounting Office (“GAO”) Audits that HHS in

terpreted Title X to allow grants to programs that counsel or

refer for abortion.14 In light of this history, it is sheer fancy to

maintain that Congress was not aware of HHS’ policies on abor

tion counseling and referral in Title X programs.

Congress reauthorized Title X six times without change,15 and

declined to use any of those opportunities to change agency

13 Pursuant to the statute, Congress has received and reviewed reports from

the agency throughout the life of the statute 42 U.S.C.A. 300a-6a. Beginning

in 1974, Congress required the agency to prepare and submit Five Year Plans

to Congress for annual review. Congress has repeatedly reviewed and referred

to these Five Year Plans and in fact has given the agency specific directions

for their improvement. See H.R. Rep. No. 1161, 93d Cong., 2d Sess. 15 (1974)

(261A); H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 1524, 93d Cong., 2d Sess. 59-60 (1974); S. Rep.

No. 29, 94th Cong., 1st Sess, 60-62, reprinted in 1975 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad

min. News 469, 522-25; H.R. Rep. No. 159, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. 7-8 (1985)

(279A); see also 121 Cong. Rec. 9789-90 (1975).

14 A GAO report issued in 1982 expressly noted that the Department had long

taken the position that a Title X grantee could provide information about abor

tion services; provide the name, address, and telephone number of abortion

providers; inspect facilities to determine their suitability to provide abortion

services; and pay dues to organizations that advocate the availability of abor

tion services. GAO, Restrictions on Abortion and Lobbying Activities In Family

Planning Programs Need Clarification 12 (1982) (107JA).

15 Title X was reauthorized in 1973. Pub. L. No. 93-45, 87 Stat. 91 (1973);

again in 1975, Pub. L. No. 94-63, 89 Stat. 304, 306-07 (1975); again in 1977,

(Footnote continued)

18

policy.16 In fact, the committee reports accompanying the

reauthorizations demonstrate that Congress intended abortion

counseling and referral to be among the services offered by T i

tle X clinics. In 1974, the House Report accompanying the ex

tension of Title X emphasized the importance of providing com

plete information about all the available services and of obtain

ing full and informed consent from the individuals served. H.R.

Rep. No. 1161, 93d Cong., 2d Sess. 18-19 (1974). In 1975, the

Senate Committee Report accompanying the reauthorization

of Title X for the following year reiterated that any medical pro

cedure or service funded by Title X required full explanation,

disclosure of alternatives, and an offer to answer inquiries. S.

Rep. No. 29, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 62, reprinted in 1975 U.S. Code

Cong. & Admin. News 469, 524-25.

In 1978, a Senate Report accompanying reauthorization re

quired discussion of the option of abortion as part of the fami

ly planning services funded under Title X. The Senate Report

emphasizes that informed consent to family planning must in

clude discussion of “the risks of various alternatives, such as

voluntary sterilization, abortion, and other options chosen volun

tarily.” S. Rep. No. 822, 95th Cong., 2d Sess. 39, reprinted in

124 Cong. Rec. 16454 (1978).

In 1985, Congress extended Title X ’s funding by continuing

resolution. The House Report accompanying the resolution

adopted HHS’s 1981 Program Guidelines and interpreted § 1008

to permit, and Title X to require, nondirective counseling on

the option of abortion. The House Report explicitly declared that

Pub. L. No. 95-83, 91 Stat. 383 (1977); in 1978, Pub. L. No. 95-613, 92 Stat.

3093 (1978); in 1981, Pub. L. No. 97-35, 95 Stat. 535 (1981); and in 1984, Pub.

L. No. 98-512, 98 Stat. 2409 (1984). See also H.R. Rep. No. 159, 99th Cong.,

1st Sess. 2 (1985) (summarizing history). Since 1985 the Title X program has

been funded through a series of continuing resolutions.

“ Contrary to the contention of the court below, 889 F.2d at 408, reauthoriza

tion without change of a federal grant statute, like any other reenactment,

can imply ratification of an agency construction, and is strongly probative

of legislative intent when Congress was aware of the agency interpretation.

See Grove City College e. Bell, 465 U.S. 555, 568-69 n.19 (1984).

19

[n]o agency shall be considered to be in violation of

the language [of Title X] . . . if a pregnant woman

is offered information and counseling regarding her

pregnancy; those requesting information on options

for the management of an unintended pregnancy are

to be given non-directive counseling on the follow

ing alternative causes of action, and referral upon re

quest: a. prenatal care and delivery; b. infant care,

foster care or adoption; c. pregnancy termination.

H.R. No. 403, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. 6 (1985). It is clear from

this and other committee reports that Congress specifically con

sidered and approved the provision of abortion-related infor

mation services in clinics funded under Title X.

3. The Regulations are Entitled to L ittle D eference

Because the language, structure and history of the statute un

equivocally express Congress’ intention to permit abortion

counseling and referral, this Court should not defer to HHS’

newly hatched interpretation of the statute. See Dole, 110 S. Ct.

at 934-38; see also Board o f Governors o f the Federal Reserve

System v. Dim ension Financial Corp., 474 U.S. 361, 368 (1986)

(“[t]he traditional deference courts pay to agency interpreta

tion is not to be applied to alter the clearly expressed intent of

Congress”); Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources D efense

Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 842 (1984) (“If the intent of Con

gress is clear, that is the end of the matter”).

Even if the Court views congressional intent on the counsel

ing and referral issue as ambiguous, however, it should not ac

cord much weight to the newly devised administrative construc

tion proffered by HHS. It is well-established that regulations

that are neither consistent nor longstanding are entitled to lit

tle deference. See, e .g ., Bow en v. A m erican Hosp. Ass’n, 476

U.S. 610, 646 n.34 (1986); C ardoza-Fonseca, 480 U.S. at 446-47

n.30; N LRB v. United Food It C om m ercial Workers Union, 484

U.S. 112, 124 n.20 (1987).17 The regulations challenged here

17 Chevron, which predates the cited cases, does not alter this principle. In

Chevron, this Court found that an agency’s continuing revision of regulations

governing industrial air pollution was in response to an objective change of

(Footnote continued)

20

reverse a longstanding agency policy that permitted nondirec

tive counseling and referral for abortion. This prior interpreta

tion, and not the newly minted one devised by HHS, provides

persuasive evidence of congressional intent.18

Not once, in the 17 years after the enactment of Title X, did

the Secretary even suggest that § 1008 restricted family plan

ning services so as to bar the provision of information about or

referral for abortion. Departmental interpretations under both

Republican and Democratic administrations were consistently

to the contrary.19

The agency first promulgated regulations to govern the pro

gram in 1971, during President Nixon’s administration. 36 Fed.

conditions within the industry. The change in regulations did not, therefore,

lessen the deference accorded to the agency. This case, however, does not in

volve any objective change of conditions within the field of family planning.

18 First, it was adopted contemporaneously with the passage of the statute.

See NLRB v. United Food, 484 U.S. at 124 n.20; Commodity Futures Trading

Comm'n v. Schor, 478 U.S. 833, 846 (1986). Second, the government agency

charged with administering the law (originally, HEW ) was active in the

legislative process and consequently had special knowledge of what the

legislature intended. See Motor Vehicles Mfrs. Ass’n v. State Farm Mut. Auto.

Ins. Co., 463 U.S. 29, 41-42 (1983). Third, the agency’s contemporaneous con

struction had remained consistent for 17 years. See EEOC v. Associated Dry

Goods Corp, 449 U.S. 590, 600 n.17 (1981); Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life

Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205, 210 (1972); cf. Bowen v. American Hosp. Ass’n, 476

U.S. at 646 n. 34.

" In fact, since 1971, HHS has repeatedly explained why § 1008 does not pro

hibit abortion-related referral and counseling in Tide X projects. First, because

nondirective counseling of pregnant women regarding available options and

“mere referral” for abortion are simply informational, they do not “promote

or encourage” abortion. See Memorandum from C. Conrad, Senior Attorney,

Pub. Health Div., to E . Sullivan, Office for Family Planning (Apr. 14, 1978)

(56JA). Second, referral of clients for abortion when contraception fails or

when abortion is medically indicated does not violate § 1008 because in such

instances abortion is not “a method of family planning.” Memorandum from

C. Conrad, Senior Attorney, Pub. Health Div., to E . Sullivan, Office for Family

Planning (July 25, 1979) (63JA). Third, nondirective counseling is not only

permitted under § 1008 but is required by the Code of Ethics of the AMA.

Memorandum from L. Heilman, M.D., Deputy Assistant Secretary for Popula

tion Affairs, to H. Connor, M.D., Regional Health Adm’r (November 19, 1976)

(74a).

21

Reg. 18465 (1971). Giving shape to the comprehensive nature of

the program, the agency required all Title X grantees to provide

“medical services related to family planning including . . . neces

sary referral to other medical facilities when medically indi

cated,” and “social services related to family planning, including

counseling . . . ” 36 Fed. Reg. 18465,18466 (1971) § 59.5(d). Title

X grantees were also specifically required to make provision for

“coordination and use of referral arrangements with other pro

viders of health care services. . . Id. at 18466 § 59.5(i). These

contemporaneous regulations also acknowledge that the funding

prohibition of § 1008 is limited to the abortion procedure. 37

Fed. Reg. 26594 (1972) § 59.5(a)(9) (“Projects will not provide

abortions as a method of family planning”) (emphasis added).

Until early 1988, these regulations remained virtually unchanged.

Furthermore, the first Five Year Plan that the Secretary sub

mitted to Congress indicated that referrals for abortions would

be appropriate in some circumstances:

Within the context of family planning services pro

grams, abortions are not viewed as a method of fer

tility control but as a service that should be available

in accordance with local laws only in the event of a

human or contraceptive method failure.

HEW National Center for Family Planning Services, Health

Services and Mental Health Administration, A Five Year Plan

f o r Fam ily Planning Services 319 (1971); id. at 318.

Interdepartmental interpretations confirmed that § 1008 was

a narrow prohibition. Only months after Title X was enacted,

the Office of General Counsel wrote that § 1008 prohibited only

the provision of abortions.20 Contrary to the Secretary’s revisionist

view that “requirements for options counseling and abortion

referral were first announced in 1981,” Pr., 53 Fed. Reg. 2923

(318A), the first Program Guidelines issued by HHS under Title

X specifically directed grantees to provide “pregnancy counsel

ing” as appropriate and referral “for any needed services

" See Memorandum from J. Mangel, Deputy Asst. General Counsel, HEW, to

L. Heilman, M.D., Deputy Asst Sec’y for Papulation Affairs (Apr. 20, 1971) (39JA)

(“. . . inasmuch as the collection of data does not itself involve the provision

of abortions, section 1008 would not, from a literal reading appear applicable”).

22

not furnished through the facility.” 'Program Guidelines fo r Project

Grants fo r Family Planning Services 16 (1976) (emphasis added).

There is no exclusion of abortion from these counseling and refer

ral requirements; in fact, the 1976 Guidelines specifically di

rected grantees to discuss abortion with a patient when a preg

nancy was discovered with an IUD in place. Id. at 15.

These requirements were retained and reinforced in the 1981