Ham v. South Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ham v. South Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina, 1971. 1bb92b34-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ea627687-40ed-45fa-8e95-c462bd828395/ham-v-south-carolina-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-south-carolina. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

4*

2 <

rT

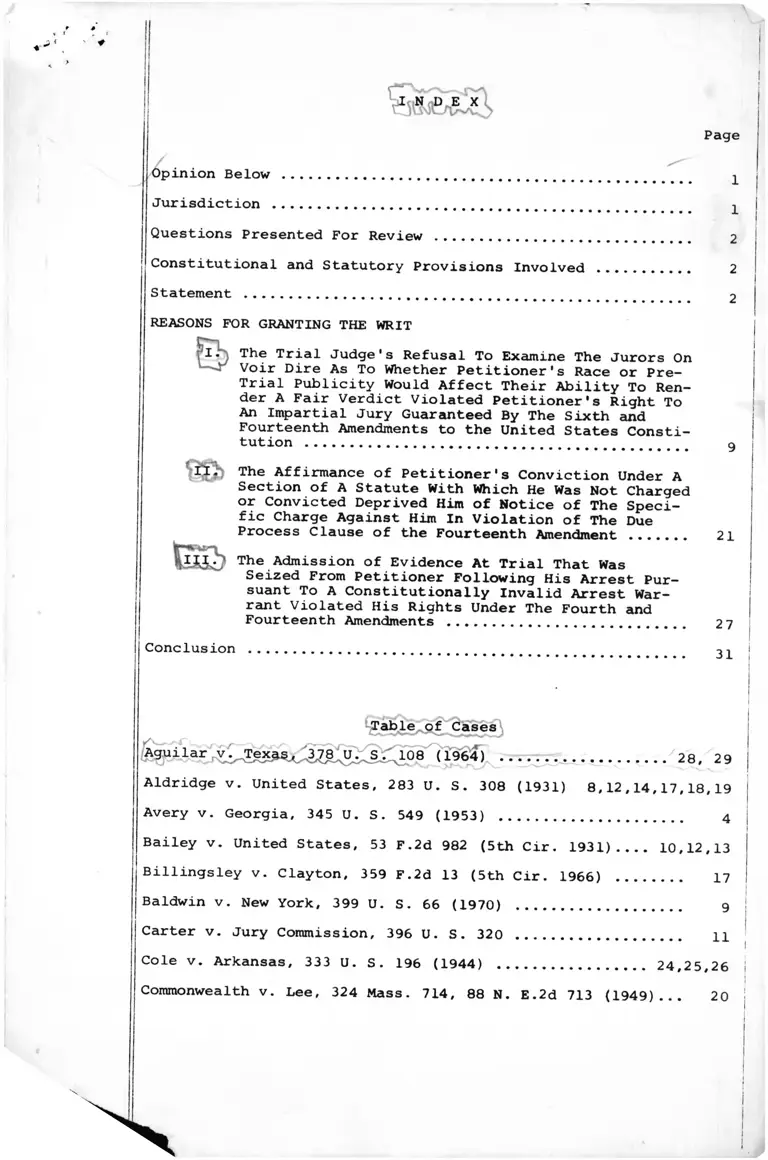

Opinion Below ..............................

Jurisdiction ...............................

Questions Presented For Review ................ .

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

Statement ............

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

E >

tSib

Conclusion

1

1

2

2

2

Page

The Trial Judge's Refusal To Examine The Jurors On

Voir Dire As To Whether Petitioner's Race or Pre-

Trial Publicity Would Affect Their Ability To Ren

der A Fair Verdict Violated Petitioner's Right To An Impartial Jury Guaranteed By The Sixth and

Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution ..................................

The Affirmance of Petitioner's Conviction Under A

Section of A Statute With Which He Was Not Charged

or Convicted Deprived Him of Notice of The Speci

fic Charge Against Him In Violation of The Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment ......

The Admission of Evidence At Trial That Was

Seized From Petitioner Following His Arrest Pur

suant To A Constitutionally Invalid Arrest War

rant Violated His Rights Under The Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments ............

21

27

31

e^pf Cases

Aguilar v ^ T e x i ^ t ^ ^ (1964) .................. 28, 29

Aldridge v. United States, 283 U. S. 308 (1931) 8,12,14,17,18,19

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 549 (1953) .................... 4

Bailey v. United States, 53 F.2d 982 (5th Cir. 1931)___ 10,12,13

Billingsley v. Clayton, 359 F.2d 13 (5th Cir. 1966) ....... 17

Baldwin v. New York, 399 U. S. 66 (1970) .................. 9

Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U. S. 320 .................. 11

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196 (1944) ................ 24,25,26

Commonwealth v. Lee, 324 Mass. 714, 88 N. E.2d 713 (1949)... 20

I

11

Dennis v. United States, 339 U. S. 162 (1950)........... 9,10,16 |

Douglas v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 415 (1965).................. 29,30

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U. S. 145 (1968) ................ 9

Estes v. Texas, 381 U. S. 532 (1965) ..................... 17

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584 (1958) ............. 17

Fraizer v. United States, 267 F.2d 62 (1st Cir. 1959) .... 18

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 (1957) ................ 26

Giles v. State, 229 Md. 370, 183 A.2d 359 (1962) ......... 20

Giordenello v. United States, 357 U. S. 480 (1958)........ 27,28

Gradney v. State, 129 Tex. Crim. 445, 87 S. W.2d 715 (1935) 20

Groppi v. Wisconsin, 27 L.Ed.2d 491 (1971)............. 10,13,18

Hayes v. Missouri, 120 U. S. 68 (1886) 10

Henry v. Mississippi, 379 U. S. 443 (1965) .......... 29,30,31

Hill v. State, 112 Miss. 260, 72 So. 1003 (1916) ......... 20

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U. S. 717 (1961)............... 9,11,12,15,17

Jones v. United States, 362 U. S. 257 (1960) ............. 28

Ker v. California, 374 U. S. 23 (1963) 27

King v. United States, 362 F.2d 968 (D.C. Cir. 1966) 18

Lewis v. United States, 146 U. S. 370 (1892) ............. io

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643 (1961) ....................... 27

Marson v. United States, 203 F.2d 904 (6th Cir. 1953) .... 18

Morford v. United States, 339 U. S. 258 (1950) 10,12

N.A.A.C.P.v. Alabama, 377 U. S. 288 (1964) ............. 31

Parker v. Gladden, 385 U. S. 363 (1966)................ 10,13,17

Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U. S. 454 (1907) 17,19

People v. Decker, 157 N.Y. 186, 51 N.E. 1018 (1898) 19

Pinder v. State, 27 Fla. 370, 8 So. 837 (1891) 20

Pointer v. United States, 151 U. S. 396 (1894) ........... 10,12

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 723 (1963).............. 11,13,17

Ross v. United States, 374 F.2d 97 (8th Cir. 1967) ....... 19

Sheppard v. Maxwell, 394 U. S. 333 (1966) ............

Page '

17

Ill

25

Page

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 376 U. S. 339 (1964)

Silverthorne v. United States, 400 F.2d 627 (9th Cir 1968) ...........................................

Smith v. United States, 262 F.2d 50 (4th Cir, 1958)

Spevack v. Klein, 385 U. S. 511 (1967) ...............

Spinelli v. United States, 393 U. S. 410 (1969)

State v. Higgs, 143 Conn. 138, 120 A.2d 152 (1956) ___

State v. Sanders, 103 S. C. 216, 88 S. E. 10 (1916)

Stilson v. United States, 250 U. S. 583 (1919)

Stirone v. United States, 361 U. S. 212 (I960) .......

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880) ......

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 202 (1965) ...............

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U. S. 346 (1970) ...............

Turner v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 466 (1965) ............

United States v. Dennis, 183 F.2d 201 (4th Cir. 1958)..

United States v. Gore, 435 F.2d 1110 (4th Cir, 1970) ..

United States ex rel. Bloeth v. Denno, 313 F.2d 364 (2d Cir. 1962) ..................................... '

Williams v. Florida, 399 U. S. 78 (1970) .............

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U. S. 510 (1968) ........

Woolfolk v. State, 85 Ga. 69, 11 S.E. 814 (1890)......

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) ..............

Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 1257 (3) .................................

Code of Laws of South Carolxna:

16,18,19

18

26

29

20

19

10

26

17

11,17,18

11

17

18

18

16

11, 13

10

20

31

1

§ 32-1506(d) ..

§ 32-1505(a)(3)

§ 32-1505(b) ..

§ 32-1463 ....

§ 32-1462(12) .

21,24,26

21

24

23

23,24

(

IV

Page

Other Authorities

Community Hostility and the Right to an Impartial Jury,60 Col. L. Rev. 349, 354 (1960) ..................... 11

Standards Relating to Fair Trial and Free Press, American

Bar Association Project on Minimum Standards For Criminal Justice (Tent. Draft, 1966) ........................... 11,13,19

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1971

No.

GENE HAM,

Petitioner,

- v . -

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review |

the judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina entered on

April 7, 1971. Rehearing was denied on April 28, 1971.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina is unof

ficially reported at 180 S. E.2d 628 and is set out in the

Appendix hereto, pp. a - 5a. Petitioner was convicted upon trial

by jury in the General Sessions Court of Florence County, South

Carolina and no opinion exists with respect to that conviction.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina was en

tered on April 7, 1971 and a timely petition for rehearing was

denied on April 28, 1971 (App. 6a) . Jurisdiction of this Court isj

invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1257(3).

Questions Presented For Review

1. Whether the trial judge's refusal to examine the jurors

on voir dire as to whether petitioner's race or pre-trial publici

ty would affect their ability to render a fair verdict violated

petitioner's right to an impartial jury, guaranteed by the Sixth

and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution?

2. Whether the affirmance of petitioner's conviction under

statutory section with which he was not charged or convicted de

prived him of specific notice of the charges against him in viola

tion of his right to due process of law, guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment?

3. Whether the admission of evidence at trial seized from

petitioner following his arrest pursuant to an invalid arrest war

rant violated his rights under the Fourth and Fourteenth Amend

ments?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. The Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution

provides in part:

"In all criminal prosecutions, the accused

shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and

district wherein the crime shall have been

committed. . .and to be informed of the na— ture and cause of the accusation; . . ."

2. Sections 38-202, 32-1462(2), 32-1463, 32-1493, 32-1505,

32-1506 and 32-1510.3 are set out in the Appendix, pp. 7a-13a.

Statement

Petitioner Gene Ham, a black man, was convicted on June 3,

1970 by a jury in the General Sessions Court of Florence, South

Carolina, of the possession of a depressant or stimulant drug in

violation of § 32-1506(d) of the Code of Laws of South Carolina

(Cum. Supp. 1970) and sentenced to eighteen months upon the public

works of the county or in the State penitentiary (R. 141)

Petitioner was arrested on the afternoon of May 15, 1970 by

three police officers while he was walking on the street in Flor- j

ence (R. 72-73). The arresting officers had four warrants for pe- I

titioner1s arrest that had been issued on May 13 and 14 charging

him with the possession of various kinds of illegal drugs (R. 4-7, ;

72, 77). After he was arrested he was frisked on the street,place<j[

m a patrol car and taken to the police station (R.73,114). There

^ References are to pages of the original record on file with the Clerk of the Supreme Court of South Carolina.

-2-

; he was booked and asked to take everything out of his pockets

| (R. 74). According to the police officers, he removed eight pack-

| at?es from his pockets which were opened, examined and found to

contain marijuana (R. 74). An arrest warrant charging him with

the possession of "certain stimulant drugs, to-wit, marijuana" was

then issued (R. 3, 78).

A preliminary hearing was held on May 28th and 29th, and pe- \

tioner was bound over to the grand jury (R. 14). He was indicted 1

on June 1st for "illegal possession of depressants or stimulants" :

in violation of "Section 32-1506, paragraph 2d" (R. 8). On the

following day, the case was called for trial in the General Sess

ions Court. At that time counsel for petitioner sought to with

draw from the case or, in the alternative, to be appointed by the

court to represent petitioner on the ground that he was indigent

(R. 9-11) . The court, however, refused to permit counsel to with-!

draw or to appoint them and directed them to continue to represent!

petitioner (R. 12). Despite the counsel’s statement that they I

were not ready to go to trial and had not had an adequate oppor

tunity to prepare written motions because the indictment had only i

been handed down on the previous day (R. 11-13), the court di

rected that they proceed with the motions orally (R. 13).

|j .Petitioner's motion for a continuance on the ground that

jj counsel had not had sufficient time to prepare for trial and had

not yet even obtained a transcript of the preliminary hearing

that had been held four days earlier was passed over, but peti

tioner was nevertheless required to make the rest of his motions

(R. 14-15). His motion for a change of venue or a continuance on

the ground of prejudicial publicity was overruled (R. 14, 15). A

motion for the dismissal of the indictment because of denial of

counsel was overruled (R. 15-19). And after a hearing, petition

er's motion to strike the petit jury venire on the grounds of

ISsystematic exclusion of Negroes, was denied (R. 19-46). At the

------- :------------ j2/ Petitioner showed that only six (17%) of the thirty-six petit jurors who were available for petitioner's case were black

despite the fact that 8,929 (32%) of the approximately 29,500|

-3-

"4. Did you watch the television show about the

local drug problem a few days ago when a

local policeman appeared for a long time?

Have you heard about that show? Have you

read or heard about recent newspaper arti

cles to the effect that the local drug prob

lem is bad? Would you try this case solely

on the basis of the evidence presented in

this courtroom? Would you be influenced by

the circumstances that the prosecution's wit— ness, a police officer, has publicly spoken on TV about drugs?" (R. 52).

The judge refused to ask all of these proposed questions on the

ground that "[t]hey are not relevant" (R. 52). instead, he asked j

each of the jurors only the following three questions:

"Have you formed or expressed any opinion as to the guilt or innocence of the defendant?

Are you conscious of any bias for or against him?

"Can you give the State and the defendant a fair Itrial" (R. 53-71).

Two jurors were excused by the court because of their answers to

these questions (R. 62-63, 70). No one was challenged for cause

by either the State or petitioner but each side exhausted its five!

peremptory challenges (R. 54, 47, 49, 61, 65, 68, 69).

At trial, one of eight small packages that a police officer

| testlfied had been among petitioner’s personal belongings when he j

was searched at the police station after his arrest was admitted

into evidence over the objection by petitioner that the State had

not sufficiently shown the chain of possession from the time of

seizure to the trial (R. 75-77). After a laboratory technician

testified over petitioner’s objection that he was not shown to be !I

: be qualified, that the seven other packages taken from petitioner !

contained approximately twenty-one grams of marijuana and that

I marijuana is classified as an hallucinogenic drug" (R. 89, 91) thei4/State rested (R. 105).

4/ Although the seven packages that were identified as contain

ing marijuana were marked for identification (R. 86) and

twice offered by the State in evidence (R. 90, 91), the record

does not show that they were ever actually admitted into evi- I

Petitioner moved for a directed verdict on the grounds that

there was no evidence that marijuana had been designated as a

"depressant or stimulant drug" or that petitioner had obtained it

without a prescription, as alleged in the indictment (R. 107).

|The motion was overruled (R. 107).

Petitioner took the stand in his own defense and testified j

that the first time he had seen the eight packages containing mar-

j ijuana was when he removed the contents of his pockets at the po-

lice station after his arrest (R. 115). He stated that he had not

had the packages in his possession at any time before he was ar

rested (R. 115-116), and could only speculate that the police

officers had planted it in his pockets when he was frisked or

later at the police station (R. 116). Petitioner, who is a civil

rights worker for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and

had been appointed by the Mayor to the Bi-racial Committee of the

City of Florence (R. 107, 128), had heard that the local police

were "out to get him" because of his civil rights' activities

(R. Ill).

Petitioner then rested his case (R. 131). After recalling

one of the police officers on rebuttal, the State rested (R. 132).

The judge charged the jury that petitioner was on trial for

the crime of illegally possessing, without a prescription, a de

pressant or stimulant drug which would have a stimulant effect on

the central nervous system (R. 133). He charged them that mari

juana had been classified as such a drug and that possession of it

jj without a prescription constituted prima facie evidence of unlaw-

i| possession (R. 134-136) . Petitioner excepted to the charge|

that marijuana had been found to be a depressant or stimulant drug,j

j and his request that the jury be further charged that if they findjj

that there is no evidence that marijuana had been so classified

they must acquit him was refused (R. 139).

The jury returned a verdict of guilty (R. 140). Petitioner's

! motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict or, in the

-6-

alternative, for a new trial which preserved his rights under all j

of his motions and objections raised during the trial was denied

(R. 140) .

On appeal, petitioner assigned as error the failure of the

trial court to dismiss the indictment and to exclude the evidence

that was seized incident to the illegal arrest, the refusal of thej

court to examine the jurors on voir dire with respect to racial

prejudice or pre-trial publicity, and the court’s refusal to di- j

rect a verdict of acquittal on the ground that he had not been

i

proven guilty of the crime charged (R. 144, 145, 147-148).in his

brief he contended that the arrest warrants had been issued in !

violation of the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments, that the ad- ;

mission of evidence seized incident to the illegal arrest viola

ted his rights under these Amendments, and that this issue had

been adequately^raised in the trial court by his motion to dismiss

the indictment. He argued that the failure of the trial judge to

ask petitioner’s proposed voir dire questions violated his right

to an impartial jury under the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments.-̂

And he argued that there was no evidence to sustain his convictionj

m vlolatlon of his right to due process of law guaranteed by the I

-Z./Fourteenth Amendment. !

In affirming his conviction a majority of the South Carolina

Supreme Court declined to consider whether the evidence seized in-j

cident to petitioner’s arrest had been admitted in violation of pel

titioner's rights on the ground that it had not been properly j

! V Brief of Appellant, pp. 5-9; Reply Brief, pp. 1-2.

6/ Brief of Appellant, p. 15; Reply Brief, pp. 3-7.

!_/ Brief of Appellant, p. 24; Reply Brief, p. 13.

-7-

objected to at trial (App. la). it held that the trial judge hadj

not abused his discretion in refusing to ask additional questions

on voir dire after he had asked the questions required by statute

(App. 2a). Finally, it held that his conviction could be sus

tained under another provision of the statute under which he had

been charged that prohibited the possession of "illegal drugs",

including marijuana (App. 3a-4a). The court concluded that the

"language of the indictment was clearly sufficient to advise [pe

titioner] of the nature of the charge" (App. 5a).

Two of the five Justices dissented on the ground that the re

fusal of the trial judge to inquire of the jurors whether they

had any prejudice because of these particular matters [petition

er's race and appearance] which would prevent them from giving a

fair and impartial verdict" was error because it was in conflict

with this Court's decision in Aldridge v. United States. 283 U. S.

j 308 (1931) (App. 8a).

| . . ! in addition to seeking rehearing on the issues raised in his

main briefs, petitioner claimed that the affirmance of his con

viction on the basis of a section of the statute with which he hadj

not been charged violated his right guaranteed by the Fourteenth

T V J 8/Amendment to be given notice of specific charges against him.

The petition was denied over the dissent of two Justices (App. 6a)L

8/ Petition for Rehearing, pp. 5-6.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I

The Trial Judge's Refusal To Examine The

Jurors On Voir Dire As To Whether Peti

tioner's Race or Pre-Trial Publicity Would

Affect Their Ability To Render A Fair Ver- aict Violated Petitioner1s Right To An Im

partial Jury Guaranteed By The Sixth and

Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.

The issue raised by this case is central to the constitutional

guarantee of a jury trial. Justice Jackson once noted that "[t]he j

right to a fair trial is the right that stands guardian over all

j other rights," Dennis v. United States. 339 U. S. 162 (1950) (con- ''

curring opinion). And the recent decisions of this Court recog

nize the crucial importance of the jury trial in the administration

i

of our system of criminal law. Baldwin v. New York. 399 U. S. 66

(1970); Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U. S. 145 (1968). But the right

to a jury trial alone does not satisfy the Constitution's mandate. I

For as this Court has said:

i" [T]he right to jury trial guarantees

to the accused a fair trial by a panel of impartial 'indifferent' jurors. The

failure to accord an accused a fair

hearing violates even the minimal stand

ards of due process . . . . in the lan

guage of Lord Coke, a juror must be as

'indifferent as he stands unsworne .

. .1 His verdict must be based on evi

dence developed at the trial" (Irvin v.Dowd, 366 U. S. 717, 722 (1961)71

Unless the impartiality of the jury can be assured, the right to a

jury trial and, indeed, the right to a fair trial will be drained

of any substance.

We are concerned here with the means which must be made avail-1

able by a state to a criminal defendant to enable him obtain an

impartial jury. Only last term this Court concluded that "under

the Constitution a defendant must be given an opportunity to show 1

l

-9-

that a change of venue is required in his case," Groppi v.

^ COn51n- 27 L -Ed-2d 491 U ” l). A state statute that barred

a change of venue in any misdemeanor case, therefore, was uncon- |

stitutional and the defendant was entitled to an opportunity to

show that prejudicial pre-trial publicity made it impossible for |

him to obtain an impartial jury in the county in which he was ;

charged. In the present case, petitioner contends that the right

to an impartial jury can only be vouchsafed if a criminal defend

ant is given a meaningful opportunity to exercise his right to

challenge prospective jurors for cause or peremptorily. Petitioner

submits that the refusal of the trial judge to question jurors on i

voir dire with respect to whether they were prejudiced against him)

because of his race or because of pre-trial publicity completely j

frustrated this right and requires the reversal of his conviction

It cannot be doubted that the right of a criminal defendant

to exercise challenges both for cause and peremptory, is encom

passed by the Sixth Amendment's guarantee of an impartial jury,

made applicable to the States through the Due Process Clause of thj

Fourteenth Amendment. Parker v. Gladden. 385 u. s. 363, 364 (196®

see Witherspoon v. Illinois., 391 u. s. 510, 518 (1968). This

Court has said that "the right of challenge comes from the common

law with the trial by jury itself, and has always been held essen

tial to the fairness of trial by jury," Lewis v. United States

i 146 U ' S ' 37°' 376 <1892>- "Preservation of the opportunity to

prove actual bias is a guarantee of a defendant's right to an im

partial jury," Dennis v. United States. 339 U. S. 162, 171-172

(1950); see Morford v. United States. 339 U. S. 258 (1950). And

the right to peremptory challenges, without showing cause," is one

of the most important of the rights secured to the accused."

I2±nter v. United States, 151 u. s. 396. 408 (1894); see Haves v.

Missouri. 120 U. S. 68 (1886,; Bailey V . United States 53 F.2d

984 (5th Cir. 1931); cf. Stilson v. United States.250 u. S. I

-10-

583, 586 (1919). Historically, the right of challenge has been an

integral part of the jury system, see Swain v. Alabama. 380 U. S.

202, 212-13 (1965), and was clearly conceived of as fundamental by

the framers of the Sixth Amendment. See Williams v. Florida. 399

U. S. 78, 94 (1970). Although this Court has never explicity held!

that the right of challenge is a requirement of due process appli-j

cable to the States, the reason probably lies in the fact that it

is guaranteed in one form or another to a criminal defendant in

9/each of the fifty States and the District of Columbia.

The right of challenge is essential to the constitutional

guarantee because it is the principal method available to insure !

an impartial jury. See Note, Community Hostility and the Right toj

an Impartial Jury, 60 Col. L. Rev. 349, 354 (1960). Jury select

ion procedures can at best only provide juries that represent a

"cross-section" of the community, from which particular groups

have not been excluded. See Carter v. Jury Commission. 396 U. S. j

320; Turner v. Fouche, 396 U. S. 346 (1970). Similarly, the right!

to a continuance or to a change of venue only serves to reduce the!

liklihood of prejudice to a defendant which may result from com

munity hostility arising out of a particular case. See Irvin v.

Dowd, supra, Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 723 (1963). Indeed,

these means are often available only after a defendant has beeni

unable to secure an impartial jury through the exercise of his

I• j challenges. Standards Relating to Fair Trial and Free Press.

!! ■rican — ar Association Proiect on Minimum Standards For Criminal!

j — S-̂ ice (Tent* ^aft, 1966), pp. 126-127. it is only through the |

exercise of challenges, therefore, that the defendant can eliminate

individual jurors who for any reason would not be impartial in ren-i

| dering a verdict. Without this right, there would be no way to

- - ,

9/ See Appendix, pp. 14a-16a.

I

guarantee to an accused that the jurors who may actually strip

him of his life or liberty are not infected by the kind of bias

or prejudice that would deprive him of"a fair trial by a panel of i

'indifferent' jurors." Irvin v. Dowd, supra, 366 U. S. at 722.

It follows that an accused must be provided with a reasonable!

opportunity to examine prospective jurors on voir dire. Speaking <

of the right of peremptory challenges, this Court has said:

"Any system for the impaneling of a jury

that prevents or embarrasses the full,

unrestricted exercise by the accused of that right, must be condemned. And,

therefore, he cannot be compelled to make

a peremptory challenge until he has been

brought face to face, in the presence of

the court, with each proposed juror, and

an opportunity given for such inspection

and examination of him as is required for

the due administration of justice" (Pointer

v. United States, supra, 151 U. S. at 409).

It is, of course, equally true that the right to challenge a jIIjuror for cause would be a hollow guarantee unless the accused

were able to ascertain the facts pertaining to a juror's legal

disqualifications or state of mind so that he can intelligently

exercise a challenge. See Morford v. United States. 339 U. S.

258, 259 (1950); Aldridge v. United States. 283 U. S. 308 (1931);

Bailey v. United States, 53 F.2d 982, 984 (5th Cir. 1931); People

v. Boulware, ___ N. Y.2d ___ (No. 115, 1971) (Slip op. p. 3). In '

the absence of a voir dire examination, the only means that a de- !

fendant would have of discovering grounds upon which to exercise aj

challenge would be to investigate the prospective jurors prior to 1

the commencement of the trial. But such a possibility does not

provide a realistic alternative to a voir dire examinationa Even

if it were possible to gather some information upon which to ex—

ercise challenges, such an investigation would be unlikely to dis

close the attitudes that a juror would only reveal when he is put

under oath and examined by the court or counsel. The practical

impossibility, moreover, for a criminal defendant, who may be

II

!

indigent, to conduct an extensive investigation of a trial venire

of forty or fifty jurors in the limited time between the publica

tion of t h e o r y list and the time of trial severely limits its

usefulness. Finally, any procedure which encouraged pre-trial

contact between a defendant and prospective jurors would greatly

impair the jury's detachment and be subject to serious abuses.

See Parker v. Gladden, supra, 385 U. S. at 369 (Harlan J. dis

senting) . The conclusion that the opportunity to examine pros

pective jurors is constitutionally required is buttressed by the j

fact that a voir dire examination is universally provided as part I

of the jury selection process in the fifty States and the District]

of Columbia. Just as a defendant is constitutionally entitled tcj

show that a change of venue is required to insure an impartial jud,

~ ?ppi v * Wisconsin, supra, so too must he be entitled to a mean- j

ingful opportunity to select an impartial jury in the venue in

which he is tried.

The extent of the examination to which an accused is entitled]

is the issue squarely presented by this case. The importance of |

this issue and its implications for our system of criminal justice!

are great. For the rising concern about the elimination of the

prejudicial effects on juries of pre-trial publicity, see Groppj

V* Wisconsin, supra; Rideau v. Louisiana, supra; Standards 1

Relating to Fair Trial and Free Press, supra, is paralleled by an j

increasing need to promote efficiency in the administration of

justice. See Williams v .__Florida, supra, 399 U. S. at 134-35

10/ In the present case, petitioner was indicted on June 2, 1970 i

Junef3rd*” d?Y °f thJ term °f COUrt' and his trial began on June 3rd. in accordance with South Carolina practice, the

S e pe5sons was not selected and summoned un- ;

t ^e5ore<:the beginning of the term of court (R.39- turv Code of Laws of S. C. In other jurisdictions,jury lists are often not made available until the trial com-

mences. See Bailey v. United States. su£>ra. 53 f.2d It 983. I

11/ See Appendix, pp. 17a-18a.

-13-

! !

(Harlan, J. concurring). Thus, in any particular case the right

to a meaningful opportunity to select an impartial jury must be

reconciled with the State's interest in avoiding unnecessary delay:

and expense in bringing criminal defendants to trial.

The resolution of these competing claims must necessarily be '

left largely to the discretion of the trial judge, depending on!

the circumstances of the particular case. But this Court has said

that this discretion is "subject to the essential demands of fair

ness." Aldridge v. United States, supra. 283 U. S. at 310. And

petitioner submits that under the circumstances of the present

I case' the refusal of trial judge to ask the prospective jurors any

questions at all pertaining to racial prejudice or pre-trial pub

licity violated the "essential demands of fairness" and requires

the reversal of his conviction.

Petitioner, as noted by the two dissenting Justices on the

South Carolina Supreme Court, is a "black, bearded civil or human

rights activist" whose role as a SCLC worker had gained him a cer

tain notoriety in Florence County, South Carolina (R. 107, lll-112)j

He was charged with the possession of marijuana, and the State's \

case was based entirely on the testimony of white police officers i

who claimed that they had found the drug in petitioner's possess- j

ion while searching him pursuant to an arrest on an unrelated

charge (R. 74). Petitioner, on the other hand, testified that he j

did not have any marijuana in his possession and that he was being!

framed by the authorities because of his involvement in civil

rights (R. 116). The case was, moreover, of more than usual in

terest because of the recent concern in Florence over the serious

drug problem (R. 52). Indeed, the police officer who was the

State's chief witness had recently appeared on local television on!

I! 'I a program devoted to drug abuse (R. 52).

In order to minimize the possibility that the jury that wouldj

hear his case would be prejudiced against him, petitioner moved to

-14-

sys-quash the trial venire on the grounds that blacks had been

tematically excluded and for a change of venue or a continuance

on the ground of pre-trial publicity. But these motions were

summarily denied (R. 14-15,4Q -Despite the fact that the trial

judge was thus alerted to circumstances showing a very real pos

sibility that prospective jurors might be hostile or prejudiced

towards petitioner, he conducted the most cursory voir dire exam

ination. He asked each juror individually three general ques-

tions, and refused petitioner's request that additional ques

tions be asked on voir dire pertaining to whether the jurors

would be influenced by petitioner’s race, by the use of the term

"black," by the fact that petitioner wore a beard, or by recent

television and newspaper publicity relating to the local drug

problem (R. 52). The jury was impaneled after each side had ex

hausted its peremptory challenges (R. 71).

Petitioner submits that such a limitation on the voir dire

examination frustrated his right to challenge prospective jurors

and thereby violated his right to an impartial jury guaranteed by

the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments. Clearly, the three general

questions thejudge put to the jurors relating to their impartial

ity were inadequate to elicit meaningful responses. It has been

widely recognized that the mere statement by a juror that he can

be impartial, particularly in response to a general query, is en- j

titled to little weight. In Irvin v. Dowd, supra. 366 U. S. at

728, this Court pointed out that at the defendant's trial:

12/ See p. 5, supra. The trial judge apparently asked and receiv-l

ed a negative response to a fourth question as to whether anyi

member of the panel was related to the defendant by blood o r !

marriage which he addressed to the group of prospective jur- I ors collectively (R. 51). J !

-15-

"No doubt each juror was sincere when

he said that he would be fair and im

partial to petitioner, but the psycholog

ical impact of requiring such a declara

tion before one's fellows is often its father."

And one federal court concluded that:

"[Mjerely going through the form of ob

taining jurors' assurances of impar

tiality is insufficient [to test that

impartiality] . . . [Wjhether a jurorcan render a verdict based solely on

evidence adduced in the courtroom

should not be adjudged on that juror's

own assessment of self-righteousness

without something more." (Silverthorne

v. United States, 400 F.2d 627, 638-39

(9th Cir. 1968) (Emphasis in original)).

See also Dennis v. United States, supra. 339 U. S. at 176; United

Sta-tes ex rel. Bloeth v. Denno, 313 F.2d 364 (2d Cir. 1962) (en

j banc). Instead, "the defendant in a criminal case has the 'right

to probe for the hidden prejudices of the jurors'," and calling

for purely subjective responses to general questions is ineffect

ive to test their competency. Silverthorne v. United States.

| supra. 400 F.2d at 640.

l|

We submit that in the present case the trial judge was con

stitutionally required to go beyond such general questioning and

to inquire specifically as to the effects of racial prejudice and

Pre_^r-'-a-*- Publicity. We think that minimal standards for insur

ing impartiality require that an accused who is a member of a

minority group which is the subject of widespread prejudice be

permitted to probe the attitudes of the jurors with respect to

such prejudice and that he also be permitted to elicit objective

facts concerning their contact with pre-trial publicity.

The decisions of this Court have long recognized that racial

prejudice and pre-trial publicity represent the most serious

threats to the integrity of the jury system. As long as 1880 this!

Court held that the "apprehended existence of prejudice" against

a black criminal defendant from a jury from which blacks had been '

systematically excluded required the reversal of his conviction. |

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880). In order to preJ

vent racial prejudice from affecting the impartiality of juries, j

an unbroken line of cases since that time have held that any

racial discrimination in the selection of juries violates an ac

cused s right to due process and to the equal protection of the

law, regardless of any showing of actual prejudice. See Eubanks

v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584, 585 (1958); Billingsley v. Clayton.

359 F.2d 13, 15 (5th Cir. 1966). The right of the accused to a

jury determination of guilt based only upon the evidence

at a trial has also been recognized as one of the fundamental j

guarantees of due process. Patterson v. Colorado. 205 U. S. 454

(1907). And this Court has been sensitive to the potentially

prejudicial affects of publicity and extra-judicial statements

upon this guarantee. Parker v. Gladden. supra; Sheppard v.

Maxwell, 394 U. S. 333 (1966); Estes v. Texas, 381 U. S. 532 (1963

Turner v - Louisiana, 379 U. S. 466 (1965) ; Rideau v. Louisiana.

373 U. S. 723 (1963) ; Irvin v. Dowd, supra.

But both of these essential constitutional protections are

rendered virtually meaningless with respect to the selection of

the jury which will actually try his case unless an accused is

permitted to make inquiries of the nature sought here by petition—j

er. Indeed, in Swain v. Alabama. 380 U. S. 202, 221 (1965) this

Court noted that the influence of race on jurors is widely ex

plored during voir dire and "that the fairness of trial by jury

jj requires no less." In Aldridge v. United States. 283 U. S. 308

(1931), this Court held that it was error for a federal trial

I judge to refuse to ask prospective jurors a "question relative to !

racial prejudice' ' on the voir dire examination in a case where

a black defendant was charged with shooting a white policeman

(283 U. S. at 311). Citing with approval several State cases

which upheld the right of a defendant to ask questions designed

to disclose racial prejudice, the Court noted "the widespread

sentiment that fairness demands that such inquiries be allowed"

(283 U. S. at 313). Although the voir dire inquiry mandated by

Aldridge has never been explicitly held to be binding on lthe

States (but see Swain v. Alabama, supra. 380 U. S. at 221), fed-

ieral courts have consistently held that a criminal defendant has j

a right to examine jurors specifically with respect to racial pre-j

judice. United States v. Gore, 435 F.2d 1110 (4th Cir, 1970);

j King v. United States. 362 F.2d 968 (D.C. Cir. 1966) ; Fraizer v.

United States. 267 F.2d 62 (1st Cir. 1959) ; Smith v. United States^

262 F.2d 50 (4th Cir. 1958); United States v. Dennis, 183 F.2d

201, 227, n. 35, 228 Aff'd 341 U. S. 494 (1951). In Gore, more- j

over, the court rejected the argument that Aldridge should be re-

istricted to cases of interracial violence. The court held that

the refusal to ask questions concerning racial bias could not be ^

|considered harmless error where, as in the present case, the de

fendants were black and the government's witnesses were white, ancj

the outcome depended on weighing credibility. United States v.

Gore, supra, 435 F.2d at 1112. The right to inquire into the ex- !

posure of jurors to pre-trial publicity is implicit in the deci- !

sions of this Court, Groppi v. Wisconsin, supra; Irvin v. Dowd,

supra, and its denial has been held to be reversible error by

federal courts. Silverthorne v. United States, supra; Marson v.

United States. 203 F.2d 904 (6t.h Cir. 1953).

In affirming petitioner's conviction, the South Carolina IISupreme Court held that the trial judge did not abuse his discre- j

tion in refusing to ask the requested questions in view of the

fact that petitioner "failed to carry the burden of showing that

[the] questions should have been asked to assure a fair and im

partial jury" (A. 2a). The court did not indicate, nor is it

|

-18-

obvious, what kind of showing a defendant must make before he can

ask whether race prejudice or pre-trial publicity would affect a

juror's ability to render an impartial verdict. Under the cir

cumstances of this case where a black civil rights worker was

being prosecuted on a drug charge in the midst of rising concern

over a serious local drug problem, it certainly cannot be said

that the possibility of such prejudice is remote. C± . Ross v.

United States, 374 F.2d 97, 104-105 (8th Cir. 1967). And it is

|

clear that an affirmative answer to such questions would have pro-j

vided the ground for a challenge for cause. State v. Sanders,103 j;

S. C. 216, 88 S. E. 10 (1916) ; People v. Decker, 157 N.Y. 186,

51 N. E. 1018 (1898); Patterson v. Colorado. 205 U. S. 454 (1907)J

By requiring an additional showing that there is some need to ask I

questions of this nature, the court undermines the very function !

of the voir dire examination and completely frustrates any op-

13/portunity that an accused has to select an impartial jury.

This holding is squarely in conflict with the decision of

this Court in Aldridge which lays down a broad rule that "an

accused has a right to inquire whether racial prejudice precludes

any juror from reaching a fair and impartial verdict," United

States v. Gore, supra, 435 F.2d at 1110, as well as with the de

cisions of federal courts which permit enough of an inquiry that

the court can "objectively [assess] the impact caused by . . .

pretrial knowledge on the juror's impartiality." Silverthorne !

v - United States, supra. 400 F.2d at 638. See Standards Relating I

to Fair Trial and Free Press, supra. § 34, pp. 130-131. The de

cision of the South Carolina Court also exposes a serious divi

sion between those States which follow the South Carolina rule j

holding that it is within the discretion of the trial judge to

13/ See pp. 12, 13, supra.

-19-

refuse to inquire into matters of racial prejudice, see WooIfoik

v. State, 85 Ga. 69, 11 S. E. 814 (1890) ; Commonwealth v. Lee, 324

Mass. 714, 88 N. E.2d 713 (1949); Gradney v. State. 129 Tex. Crim

445, 87 S. W.2d 715 (1935); Hornsby v. State, 94 Ala. 55, 10 So. I

522 (1891), and those States which recognize that an accused has j

a right to make such an inquiry on the voir dire examination,

Giles v. State, 229 Md. 370, 183 A.2d 359 (1962) ; state v. Higgs. |

143 Conn. 138, 120 A.2d 152 (1956); Pinder v. State. 27 Fla. 370,

8 So. 837 (1891); Hill v. State, 112 Miss. 260, 72 So. 1003 (1916).

This Court should grant certiorari in this case to decide

whether the fundamental constitutional right to an impartial jury

guarantees a criminal defendant a meaningful opportunity to ex

amine and challenge jurors who may be prejudiced against him. Inj

so doing, this Court can resolve the conflict between the decision

of the court below and the decisions of other state and federal

courts, as well as to provide needed constitutional standards wittj

respect to the crucial jury selection process.

I

I

The Affirmance of Petitioner's Conviction Under A Section of A Statute With Which

He Was Not Charged or Convicted Deprived

Him of Notice of The Specific Charge

Against Him In Violation of The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

On May 15, 1970 petitioner was arrested on a warrant charging

j him with the Possession of "certain stimulant drugs, to wit,

marijuana" (R.3). He was indicted on June 1, 1970 for "Illegal

I Possession of Depressants or Stimulants" on the ground that he:

II "did violate Section 32-1506, paragraph 2d,

of the 1962 Code of Laws for the State of

South Carolina, as amended, in that he did

possess a quantity of drugs, without medi

cal prescription and without being prescribed

or administered by medical prescription or

authority, said drugs designated as having a

potential for abuse because of its depressant

or stimulant effect on the central nervous

system or its hallucinogenic effect, namely marijuana" (R.8).

Thus, petitioner was clearly charged with the crime of

possessing a "depressant or stimulant drug" and the indictment

tracks the statutory definition of such a drug found in

§ 32-1505 (a) (3) :I

"Any drug which contains any quantity of a

substance which the State Board of Health

or the appropriate Federal drug authorities

have found to have, and by regulation designated as having a potential for abuse be

cause of its depressant or stimulant effect

on the central nervous system or its hallucinogenic effect."

The possession of such a drug is made illegal by § 32-1506(d)

when, as the indictment charges, it is not obtained from, or on

.. . . 14/the prescription of, a medical practitioner.

14/ The reference to "Section 32-1506, paragraph 2d" in the

indictment is obviously an error since this section deals only with "delivery" of drugs and not with possession.

lii j

|

-21-

I

The State's case in chief consisted solely of the testimony

| °f tWO police officers who stated that they had arrested peti-

I tioner on an unrelated charge and had discovered eight small

I Packages in the course of a search of his personal belongings

whioh were identified as containing approximately 24

i grams (less than one ounce) of marijuana (R.89-90). Petitioner

moved for a directed verdict at the close of the State's case on

the grounds that the State had failed to prove, in the terms of

the indictment, that marijuana had been "designated as having a

potential for abuse because of its depressant or stimulant effect

on the central nervous system or its hallucinogenic effect" or

j that petitioner had possessed the drug "without medical prescrip-

|i tlon and without being prescribed or administered by medical pre

scription or authority", as alleged in the indictment (R.106-107).

This motion was overruled (R.107)

j

| After both sides had rested, the trial judge charged the jury

that petitioner was on trial for the crime of possessing depress

ant or stimulant drugs which have a "stimulant effect on the

central nervous system" without a medical prescription (R.133).

| He defined "depressant or stimulant drug" as any substance:

"which the State Board of Health and the

|j appropriate Federal authorities after in

vestigation found to be, and have by regulation

designated as habit-forming, because of its

stimulant affect on the central nervous system,

or any drug which contains any quantity of

substance which the State Board of Health and

the appropriate Federal drug authorities have

found to be, and by regulation designated as having a potential for abuse because of its

depressant or stimulant effect on the central

nervous system, or its hallucinogenic effect"(R.134) .

! The judge further charged that "[m] arijuana has been labelled as a

| dePressant or stimulant drug having an effect on the central j

nervous system" and that its possession without being in a con

tainer with a prescription label is prima facie evidence that the

possession is unlawful (R.135-136).

Petitioner excepted to the charge that marijuana had been

found to be a depressant or stimulant drug and requested that the

judge further charge the jury that "if there is no evidence of a

i finding or regulation of the State Board of Health and of the

|j Federal Drug Authority concerning the potential for abuse and the !

|| effect on the central nervous system, or the hallucinogenic effect

i! of marijuana, then they must acquit him" (R.139). The request

jj was refused (R.139), and jury returned a verdict of guilty (R.140).

On appeal, petitioner urged that the State had completely

failed to prove the essential elements of the crime with which he

| was charged, i.e., that he had possessed a drug which had been

designated by State and Federal authorities as having a potential

I

j| f o r abuse because of its depressant or stimulant effect on the

j central nervous system or its hallucinogenic effect. He pointed

! out that the statute under which he was charged was clearly not

jj intended to apply to the possession of marijuana which was classi-

j fled as a "narcotic drug" and specifically made unlawful under the

provisions of the Uniform Narcotic Drug Act (§§ 32-1462(12), 32-

1463). The State, on the other hand, argued that the testimony j

of the laboratory technician that marijuana "is classified as an

i

j hallucinogenic drug" (R.91) was sufficient to bring marijuana

within the statutory definition of a depressant or stimulant drug

and that it was common knowledge that marijuana has a "potential

I i§/for abuse."

The South Carolina Supreme Court did not affirm petitioner's

! conviction on the ground that the State had sufficiently proved

that marijuana was a "depressant or stimulant drug." Rather, the

1J>/ Brief of Appellant, pp. 22-24; Reply Brief, pp. 10-13

16/ Brief of Respondent, pp. 17-19.

-23-

court noted that the section of the statute under which petitioner

u yhad ostensibly been charged had been amended on May 1, 1970,

one month before petitioner's indictment, to make illegal the

I "possession of a depressant, stimulant, counterfeit or illegal

i — --2" (emphasis added) . The court pointed out that under §§ 32-

| 1505(b) the definition of "illegal drug" includes "any narcotic

drug" and that § 32-1462(12) of the Uniform Narcotic Drug Act in-

I cludes marijuana within the definition of "narcotic drugs". Thus;

'j even though it was clear that petitioner had been charged, tried

| and convicted for the possession of a "depressant or stimulantI

j d r u < ? the court concluded that the conviction could be sustained

jj because the same statute also penalized the possession of "illegalI

j drugs" which included marijuana. in response to petitioner's

contention that he had been deprived of fair notice of the charge

| against him, the court simply stated:

"The language of the indictment was clearly

sufficient to advise him of the nature of | the charge" (A.4a).

jj Petitioner submits that the affirmance of his conviction

j by the South Carolina Supreme Court on the basis of a section of

j the statute with which he was not charged denied him his right to

| due process of law guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. This

I

ij case is closely analogous to Cole v. Arkansas. 333 U.S. 196 (194,11

it \ / ,

:! where the defendants had been charged and convicted of violating

j!j; § 2 °f a criminal statute but the State Supreme Court affirmed the j

ljj convictions under § 1 of the statute. In reversing the convic-

j tions, this Court held:

!-------------- ----------------------------

^ in?ifi?nent referred to it as "§ 32-1506, paragraph2d and the Supreme Court referred to it as § 32-1506

( )(d)." The correct citation, however, is § 32-1506(d).

I

See

"No principle of procedural due process is

more clearly established than that notice of the specific charge, and a chance to be

heard in a trial of the issue raised by that

charge, if desired, are among the constitutional

rights of every accused in a criminal proceeding in all courts, state or federal . . . If, as

the State Supreme Court held, petitioners were

charged with a violation of § 1, it is doubtful

both that the information fairly informed them

of that charge and that they sought to defend

themselves against such a charge; it is certain

that they were not tried for or found guilty of

it. It is as much a violation of due process

to send an accused to prison following conviction of a charge on which he was never tried

as it would be to convict him upon a charge

that was never made" (333 U.S. at 201).

, 18/ also Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham. 376 U.S. 339 (1964). The

Court further concluded that the defendants' rights had also been

violated in the Arkansas Supreme Court because:

"To conform to due process of law, petitioners were entitled to have the validity of their

convictions appraised on consideration of

the case as it was tried and as the issues

were determined in the trial court" (333 U.S. at 202) .

It is plain that the decision of the court below similarly

deprived petitioner of notice of the specific charge against him

and of an opportunity to have the validity of his conviction

appraised on appeal on the basis of the theory on which the case

was tried in the trial court. Not only was petitioner misled by

the indictment into believing that the State would have to prove

'‘marijuana had been appropriately designated as a "depressant or

|lstimulant drug, but at the time of his trial there was no way in

I

the exercise of ordinary diligence that he could even have found

i|out that the statute under which he had been charged had been

•

18/ In this case this Court summarily reversed, on the authority

of Cole v. Arkansas, supra, a decision by the Alabama Supreme Court (149 So.2d 921 (1962)) affirming a conviction for

interfering with a police officer. The Alabama court had

that even if the defendant could not have been convicted

under the section of the City Code with which he was charged there was no error in his conviction "since he could have been clearly convicted of a simple assault."

-25-

!j amended °ne m<j^h earlier to include "illegal drugs" within its

| prohibitions. Indeed, it is apparent that neither the judge nor

| the Prosecuting attorney were aware of this amendment.-^

In holding that petitioner's conviction can be affirmed

because the evidence adduced at his trial is sufficient to convict

j him of some crime, even though it was not the one charged, the

jSouth Carolina Supreme Court also undermines the fundamental prin

ciple that an accused cannot be deprived of his liberty unless he

| is found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt by a jury of his peers on

the basis of the evidence presented. Garner v. Louisiana. 368 U.S.

157, 164 (1957). This basic requirement of due process is simply

not met when as in the present case, an appellate court substi-

| tutes its judgement for that of the jury. See Stirone v. United

| States. 361 U.S. 212 (1960).

Such a disregard of basic procedural due process can never beI

considered harmless error. These procedural safeguards are de

signed to insure fairness in the administration of criminal justice

and their violation cannot be excused merely because the extent of

prejudice to the defendant cannot be accurately measured. See

jsjDevack v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511, 518 (1967) ; Stirone v. United

^States, supra, 361 U.S. at 217. Consequently, this Court should

ij grant certiorari and reverse petitioner's conviction by the South

jCarolina Supreme Court "upon a charge that was never made." Cole

! v. Arkansas, supra, 333 U.S. at 201.Ii------------------- ---------------- -

19/ In his Petiton for Rehearing in the South Carolina Supreme

Court, petitioner pointed out that it was common for legis- |j lative enactments to go unnoticed by the bar for weeks oreven months before they were officially published.(Petition for Rehearing, p.6).

20/ That the trial judge was unaware of the amendment is demon

strated by the fact that he charged the jury that under the

j statute the possession of a depressant or stimulant drug

without a container bering a prescription label was prima

facie evidence of unlawful possession (R.135-36). The second

sentence of § 32-1506(d) which created this presumption, however, was deleted by the May 1, 1970 amendment. (See §32- 1506(d), Reviser's Note).

-26-

Ill

The Admission of Evidence At Trial That Was

Seized From Petitioner Following His Arrest

Pursuant To A Constitutionally invalid"

Arrest Warrant Violated His Rights UncTer

The Fourth And Fourteenth Amendments

It is clear that none of the four arrest warrants pursuant to

which petitioner was arrested on May 15, 1970 was based on a

sufficient showing of probable cause. Petitioner's arrest,

! therefore, violated the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments and the

jevidence seized incident to the arrest was inadmissible at trial.

Giordenello v. United States. 357 U.S. 480 (1958); Ker v.

California, 374 U.S. 23 (1963 ); Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961)

Each of the warrants had been issued on May 13th or 14th,

1970 on the basis of an affidavit sworn to by E. J. Lessmeister,

chief of detectives of the city of Florence (R. 4-7, 71). Three

of the affidavits alleged only that on a certain date petitioner

had a certain stimulant drug in his possession and sold it to

„ • 21/ one Mike Martin," and one affidavit alleged only possession.

2_1/ The material part of each affidavit is as follows:

". . . on or about the 27 day of April, 1970,

one Gene Ham did have in his possession certain

stimulant drugs, to-wit: Dexamyl #2, and did

sell the same to one Mike Martin." (r . 4)

". . . on or about the 14 day of May 1970,

One Gene Ham did have in his possession

a quantity of stimulant drugs, to-wit.Librium, 5 mg." ( r . 5)

". . . on or about the 19 day of April 1970, one Gene Ham did have in his possession

certain stimulant drugs, to-wit: Dexamyl#1, and did sell the same to one Mike Martin." ( r . 6)

" • - . on or about the 30 day of April 1970, one Gene Ham did have in his possession

certain stimulant drugs, to-wit:

Bithetamine #20, and did sell the same to one Mike Martin." (R. 7)

ll

-27-

No facts or circumstances were set forth indicating the basis

or the source of Officer Lessmeister's conclusion from which a

neutral and detached magistrate could make an independent

determination that petitioner had committed a crime. Aguilar v.

Texas, 378 U.S. 108 (1964); Jones v. United States. 362 U.S.

257 (1960 ).

On the basis of this Court's decision in Giordenello v.

United States, supra, there can be no question but that these

I warrants violated the Fourth Amendment. in that case, this Court

construed Rule 4 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure in

light of the Fourth Amendment's requirement of probable cause

and reversed a conviction based upon evidence seized pursuant

to an arrest on a warrant which had been issued without a suffi

cient showing of probable cause. That warrant, almost identical

to the ones at issue here, alleged only that the defendant received

and concealed a narcotic drug on a particular date with knowledge

of unlawful importation. In language equally applicable to the

:present case, this court said:

"fl]t is clear that [the complaint] does not

pass muster because it does not provide any

basis for the Commissioner’s determination under Rule 4 that probable cause existed.

The complaint contains no affirmative allegation that the affiant spoke with personal

knowledge of the matters contained therein;

it does not indicate any sources for the

complainant's belief; and it does not set

forth any other sufficient basis upon which

a finding of probable cause could be made "(357 U.S. at 486)

As in Giordenello. moreover, the record in this case affirmatively

|showed that the affiant had no personal knowledge of the facts

on which the charge was based ( r . 48-49) Ibid. Finally, even if

-28-

I

it were assumed that the "one Mike Martin" referred to in the

affidavits was the source of Officer Lessmeister's knowledge,

|the affidavits still fall far short of establishing probable

!| cause. S£inelli v. United States. 393 U.S. 410 (1969); Aguilar v

—

Texas, supra.

The South Carolina Supreme Court declined to consider the

constitutionality of the arrest and search of petitioner on the

ground that he had not objected for that reason to the admission

at trial of the evidence seized (App. la ). Petitioner submits,

j however, that his failure to make a contemporaneous objection to

the admission of the marijuana into evidence is not an adequate

state ground which can preclude this Court from reviewing the

federal question presented. See Douglas v. Alabama. 380 U.S.

415, 422 (1965); Henry v. Mississippi. 379 U.S. 443, 447 (1965).

It is settled that "a litigant's procedural defaults in

state proceedings do not prevent vindication of his federal rights

unless the State’s insistence on compliance with its proceduralI

jirule serves a legitimate state interest." Henry v. Mississippi.

sujDrâ 379 U.S. at 477. No such interest was served in the

present case by the enforcement of the contemporaneous objection

rule to bar consideration of petitioner's constitutional challenge

to his conviction in the South Carolina Supreme Court. On the

contrary, petitioner's pre-trial motion to dismiss the indictment

which was "ample and timely to bring the alleged federal error to

the attention of the trial court and enable it to take appropriate

corrective action [was] sufficient to serve legitimate stateI

interests, and therefore sufficient to preserve the claim for

Review here." Doug las v. Alabama, supra, 380 U S at 422

—

In the pre-trial motion, petitioner clearly brought to the

attention of the trial judge his claim that the warrants pursuant

-29-

I

I to which he was arrested were invalid for want of a sufficient

showing of probable cause for their issuance ( r . 48-50). The

corrective action of a dismissal of the indictment which he sought

was, moreover, clearly appropriate in view of the fact that the

indictment was based entirely upon the evidence seized as a

result of his illegal arrest. When the trial court denied this

motion it ruled adversely to petitioner on the same federal claim

which would have provided the basis for his later objection to the

admissibility of the seized evidence. Thus, "fn]o legitimate

interest would have been served by requiring repetition of a

patently futile objection," Douglas v. Alabama, supra. 380 U.S.

at 422, and "giving effect to the contemporaneous-objection rule

for its own sake 'would be to force resort to an arid ritual of

meaningless form.'" Henry v. Mississippi, supra, 379 U.S. at 449.

Petitioner cannot, moreover, be penalized for failing to

clearly spell out the argument that the indictment should be

dismissed because the evidence seized as a result of the illegal

arrest was inadmissible. He was forced to go to trial two days

after the indictment against him had been returned and before his

counsel was even able to obtain a transcript of a preliminary

22/hearing that had been concluded three days before the indictmentT

Indeed, on the day following the indictment his counsel had sought

to withdraw from the case on the ground that petitioner wasI

unable to retain him. When the court refused to permit counsel

to withdraw, petitioner moved for a continuance on the ground that

he had not had an adequate opportunity to prepare for trial. This

motion was denied and petitioner was directed to proceed with any

22/ See p. 3, supra.

-30-

2_3/

motions (R. 13). in the face of such pressure to go to trial,

Pe*-itioner moved orally to dismiss the indictment because of his

illegal arrest. When counsel attempted to explain the basis for

(the motion, the trial judge abruptly interrupted him and overruled

|the motion (R. 50).

Thus, it was only the haste with which he was forced to go

to trial and the conduct of the trial judge that prevented

petitioner from fully elaborating upon his constitutional claim"!

Under these circumstances, the refusal to consider that claim is

essentially arbitrary. Where fundamental constitutional rights

are at stake, the State cannot prevent their vindication by placing

unnecessary and unjustified obstacles in the way of their

assertion. N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 377 u.S. 288 (1964 ); Wright v.

Georgia, 373 U.S. 284 (1963 ). Consequently, this Court should

24/

grant certiorari and reverse petitioner's conviction on the ground

that it was based on evidence seized in violation of his rights

under the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments.

2_3>/ In affirming his conviction, the South Carolina Supreme Court

held that the denial of this motion for a continuance was not an

abuse of discretion in light of the fact that 17 days had elapsed

between the time of petitioner’s arrest and the beginning of the

trial (App. 2a). The Supreme Court, however, failed to take

account of the fact that petitioner had been arrested on May 15,

1970 on five completely separate charges involving possession

and/or sale of different drugs on different occasions. The

^preliminary hearing on May 28 and 29 related to all of the charges ,and the record shows that petitioner was in fact indicted on each

of the charges (R. 50). The charge on which he was convicted

was merely the first that the State chose to call for trial.

Thus, petitioner received notice of the present indictment and

the State's intention to call it for trial only the day before

petitioner was required to make his motions and two days before the trial actually begun (R. 46-47).

24/ It cannot be contended that counsel deliberately bypassed

the assertion of the federal claim. See Henry v. Mississippi,

supra, 379 U.S. at 451. Since the evidence was clearly

inadmissible and its exclusion would have required an acquittal,

there could have been no strategic advantage to be derived from* failing to object.

-31-

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, petitioner prays that his peti

tion for writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina

be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG JAMES M. NABRI-:

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

MORDECAI C. JOHNSON

JOHN GAINES

P. 0. Box 743

Florence, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioner

- 3 2 -

APPENDIX

OPINION OF THE SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

In The Supreme Court

The State,

Gene Ham, .

Respondent,

Appellant.

Appeal From Florence County

G. Badger Baker, Judge

Opinion No. 19197 Filed April 7, 1971

AFFIRMED

Mordecai C. Johnson, of Florence; Frank E.

Cain, Jr., of Bennettsville; John A. Gaines,

of Rock Hill; and Jack Greenberg and Jonathan Shapiro, both of New York, New York, for appellant.

Solicitor T. Kenneth Summerford, of Florence, and Assistant Attorney General Timothy G. Quinn, of Columbia, for respondent.

LITTLEJOHN, A. J.: The defendant. Gene Ham, appeals from hii

conviction of possession of illegal drugs in violation of §32-

1506(d) (1962 Code as amended). We affirm. The facts leading to

his arrest and conviction may be summarized as follows:

On May 15, 1970, the appellant was arrested in Florence on

the basis of four warrants which charged him with possession of

stimulant drugs. Following his arrest he was taken to the city

jail and searched; the search revealed a quantity of an unidenti

fied substance. Thereafter a fifth arrest warrant was issued

charging him with possession of marijuana.

a

On May 28 and 29 a preliminary hearing was held and probable

cause found to bind Ham over to the General Sessions Court. On

June 1, 1970, the grand jury returned true bills and on June 2

the State proceeded to trial on the indictment charging possession

of marijuana. !

At the conclusion of the evidence the matter was submitted to

the jury which returned a guilty verdict. Motions for judgment

N.O.V. and a new trial were denied. Appellant was sentenced to

eighteen months and this appeal follows.

Appellant raises twelve issues for determination by this

court; we deal with them as they were presented in the briefs.

Appellant contends first that his initial arrest was not made

Pursuant to a valid arrest warrant and that the evidence seized

|

after the arrest was therefore inadmissible. We find from an

analysis of the record that no objection to the admission of the

marijuana was made at trial on this ground. At trial appellant

questioned only the competency of the State's witness to identify !

the seized substance as marijuana.

Appellant next contends that mere possession of marijuana

cannot, consistent with due process, be made a crime. He relies

primarily on Stanley v. Georgia, 394 U. S. 557 (1969). Stanley

dealt solely with the possession of allegedly obscene materials

in one's home, and is clearly inapplicable here.

The statute itself, as the trial judge stressed in his jury '

charge, requires more than "mere" possession. The trial judge

correctly set forth the presumption of innocence and reasonable

doubt, along with the requirement of "knowing" possession.

Appellant s third contention, that a change of venue should

have been granted because of prejudicial publicity,is, after an

analysis of the exhibits presented, completely without merit.

The two newspaper clippings and one editorial concerning drug

abuse did not name the defendant or refer in any way to his trialj

i

la

I

The trial judge did not abuse his broad discretion in this case

to determine fairness. State v. Cannon. 248 S . C. 506, 151 S . E

(2d) 752 (1966).

Appellant next contends that denial of his continuance motion

was prejudicial error. He cites Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45

(1932); that case involved the very different factual situation

in which Negroes, accused of raping a white woman, were never

given the effective aid of counsel. State v. Black, 243 S. C. 42,

132 S. E. (2d)5 (1963) relied on by appellant, involved a capital

offense where the death sentence had been imposed on the defendant.

There, the only experienced counsel for the defendant had become

ill and was unable to effectively participate in the trial. in j

the case at bar appellant was continuously and ably represented, j

A continuance is within the broad discretion of the trial judge. |

State v. Harvey, 253 S. C. 328, 170 S. E. (2d) 657 (1969), and !

that discretion was not abused here where seventeen days elapsed j

from the arrest to the beginning of trial.

Appellant next contends that the trial judge erred in refus- j

ing to ask proposed voir dire questions. § 38-202 (1962 Code)

sets forth the basic voir dire questions required by law; that

section also permits a defendant to introduce competent evidence j

m support of any objections to a juror. The basic questions re- j

ferred to in the section were covered. Appellant has failed to

carry the burden of showing that other questions should have been \

asked to assure a fair and impartial jury. Certainly there is no \

showing of an abuse of discretion allowed a trial judge in this j

State. State v. Britt, 273 S. C. 293, 117 S. E. (2d) 379 (1960). |

Appellant’s next contention is that the trial judge abused

his discretion in refusing to allow counsel to withdraw as re

tained attorney for defendant. It is alleged that the judge

I

2a

indigent. He cites State v. Cowart, 251 S. C. 360, 162 S. E.

(2d) 535 (1968) for the rule that when one claims to be indigent

the judge must make an affirmative determination of indigency.

Cowart is inapposite to this case in that the defendants there,

two minors, appeared at the outset with no lawyer and the trial

judge refused to appoint one. Here appellant had counsel for the

preliminary hearing and for pretrial; he appeared with this same i

counsel at trial; the lawyer apparently found that Ham was unable

and/or unwilling to pay and sought to be appointed so that the

State could pay his fee. The prejudice, if any, resulted to the

■

lawyer's purse and not to the appellant; it does not in any way

go to the substance of appellant's conviction.

I

Appellant next contends that the court below committed re

versible error in allowing a laboratory technician to testify as

an expert witness and identify the marijuana. The witness was Lt.

Wilson of the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division. He stated

to the court that he had identified marijuana on numerous occa

sions and had seen it growing in the field. He was qualified to

make the identification. The law in this State does not require

a man to have a professional degree to qualify as an expert. Such

determinations rest in the discretion of the trial judge. Parks iI

v. Morris Homes Corp., 245 S. C. 461, 141 S. E. (2d) 129 (1965)

and also McCormick Evidence § 13 (1954).

Appellant's next two contentions form the substance of this

appeal; we treat them as one. Basically, appellant contends that

the State attempted to prove him guilty of violating the wrong

statute. Appellant contends that his trial should have been under)

that section of the code dealing with "narcotic" drugs rather thah

that dealing with "depressant and stimulant" drugs.

§ 32-1506(2)(d) of the code as amended May 1, 1970, under

which the indictment was brought makes unlawful,

(d) the possession of a depressant, stimulant, counterfeit, or illegal drug by any person, unless such person

should have made a factual determination that the defendant was

I

3a

obtained such drug on the prescription of a prac

titioner, or in accordance with Section 2(a) 2."(Erapiiasis added.)

The 1970 amendment places "illegal" drugs within the class

prohibited by § 32-1506 (2) (d) . Narcotic drugs are illegal drugs

as defined in § 32-1505 (b) , and marijuana is classed as a nar- |

cotic drug in § 32-1462(12) of the 1962 Code as amended.

!This act became law on May 1, 1970, two weeks before appel-

|

lant was arrested. It follows that appellant was indicted on the

correct statute.

Appellant's next contention is that the indictment should

have been quashed because it fails to allege the offense sub

stantially in the language of the statute. Appellant did not

enumerate this ground in his motion to quash, and is precluded

from doing so now. There can be no doubt that the indictment

placed the defendant on notice that he was charged with possession}

of marijuana. The language of the indictment was clearly suffi- j

cient to advise him of the nature of the charge.

Finally, appellant contends that the imposition of an 18

Imonth sentence on a first offender constituted cruel and unusual

punishment. The sentence imposed was less than the statutory max-I

imum and there is no showing of partiality, prejudice or corrupt

motive by the sentencing judge. Thompson v. State, 2 51 S. C. 593,:

164 S.E. (2d) 760 (1968).