Mills v. Woods Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

October 27, 1950

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mills v. Woods Brief for Appellees, 1950. 529202d0-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/eab7093a-8eb8-433a-8e91-3a4523bf1c98/mills-v-woods-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

Q o /<?•

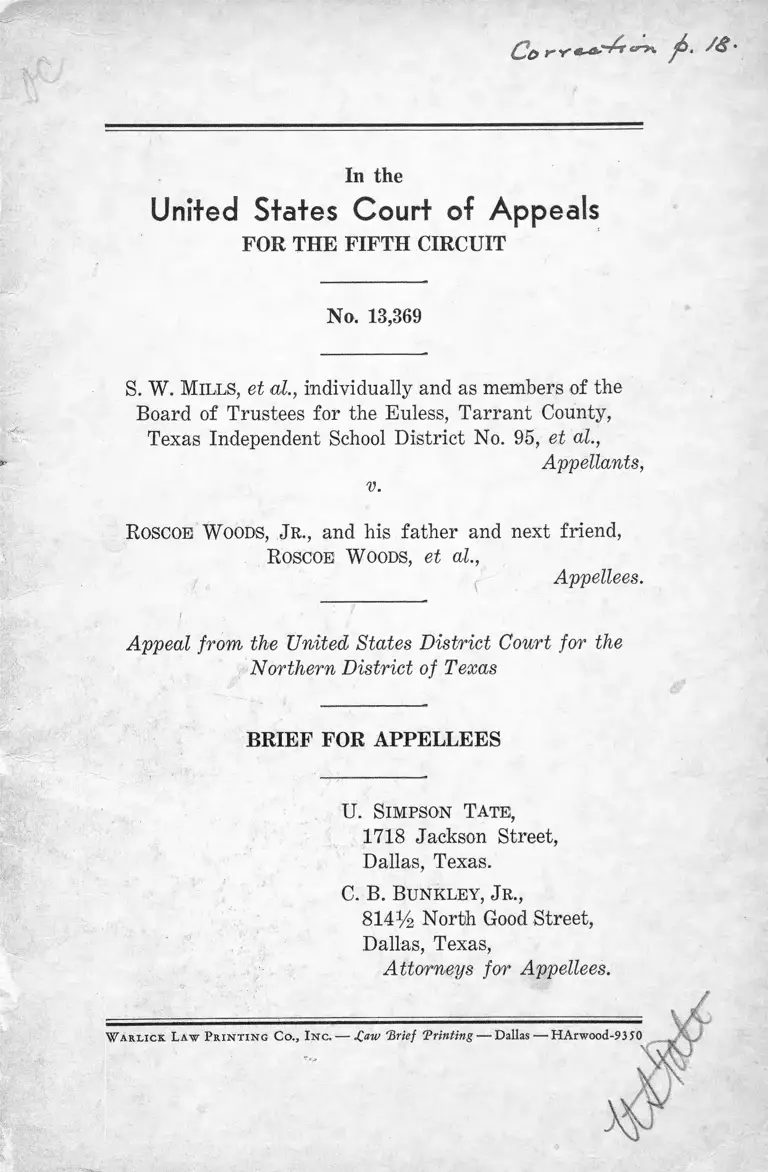

In the

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 13,369

S. W. Mills, et al., individually and as members of the

Board of Trustees for the Euless, Tarrant County,

Texas Independent School District No. 95, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

Roscoe Woods, Jr., and his father and next friend,

Roscoe Woods, et al,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

U. Simpson Tate,

1718 Jackson Street,

Dallas, Texas.

C. B. Bunkley, Jr.,

814% North Good Street,

Dallas, Texas,

Attorneys for Appellees.

I N D E X

Statement of the C ase.................................................... 1

Summary of Argum ent................................................... 5

Argument .......................................................................... 6

Conclusion ........................................................................ 28

Appendix I ........................................................................ 29

Appendix II ................................................................. 32

Appendix III .................................................................... 34

Appendix IV .................................................................... 36

Page

ii Cases Cited

Page

Alston v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 112

P. 2d 992 ...................................................................... 27

American Machine & Metal Co. v. DeBothezat Impel

ler Co., 166 F. 2d 535 ................................................... 21

Amherst College v. Ritch, 151 N. Y. 282, 45 N. E.

876 ................................................................................. 6

Ashley v. School Board of Gloucester County, 82 F.

Supp. 167 ...................................................................... 19

Baltimore & P. Ry. Co. v. The Sixth Presbyterian

Church, 91 U. S. 1 2 7 .................................................. 8

Baskin v. Brown, 174 F. 2d 391 .................................... 25

Bechtel v. U. S., 101 U. S. 597 ..................................... 23

Bottone v. Lindsley, 170 F. 2d 705 ................................ 23

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 38 S. Ct. 16 ....... 25

Butler v. Wilemon, 86 F. Supp. 397 ............................ 26

Canal Bank v. Hudson, 111 U. S. 6 6 ............................ 7

Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, 182 F.

2d 531 ........................................................................... 16, 26

Corbin v. School Board of Pulaski County, 177 F.

2d 924 ............................................................................ 14, 26

Cook v. Wilbanks, 223 Ala. 312, 135 So. 435 ............. 6

Daily v. Fitzgerald, 17 N. M. 137, 125 P. 625 ........... 6

Dameron v. Bayless, 126 P. 273 ..................................... 10

Davis v. Packard, 7 Pet. (U. S.) 276 ............................ 7

Dalandy v. Carter Oil Co., 174 F. 2d 3 1 4 .................... 21

Dewey & Almy v. American Anode, 137 F. 2d 6 9 ....... 21

Dowd v. Hercules Power Co., 66 Colo. 302, 181 P.

767 ................................................................................ 8

Durland v. U. S., 161 U. S. 306, 16 S. Ct. 508 ........... 8

Cases Cited— (Continued) iii

Page

Elgin v. Marshall, 106 U. S. 578, 27 L. Ed. 249 ...... 7

Elmore v. Rice, 165 F. 2d 387 ....................................... 25

Federal Security Co. v. Butler & Son, 51 F. 2d 2 4 ..... 7

Franklin Life Insurance Co. v. Johnson, 157 F. 2d

653 ................................................................................. 21

Genard v. Hasmer, 285 Mass. 259, 186 N. E. 4 6 ....... 7

Gordon v. Garrson, 77 F. Supp. 477 ............................ 23

Greer v. Standard, 85 Mont. 78, 277 Pac. 622 ........... 6

Hahn v. Kelly, 34 Calif. 3 9 1 ........................................... 7

Heck v. Heich, 163 Wis. 171, 157 N. W. 747 ............... 6

Henderson v. U. S., 338 U. S........, 70 S. Ct. 843 ........18, 26

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400, 62 S. Ct. 1159 ............... 18

Hirabayashi v. U. S., 320 U. S. 81, 63 S. Ct. 1375 ..... 18

Hoffman v. Knitting Machines Corp., 123 F. 2d 456 22

Hodges v. Merriweather, 55 F. 2d 29 .......................... 6

Independent School District v. Salvatierra, 33 S. W.

2d 790 .......... 17,27

Johnson v. Board of Trustees of Univ. of Ky., 83 F.

Supp. 707 ...................................................................... 26

Kerney v. Dean, 15 Wall. (U. S.) 5 1 ...... 8

Klaber v. Lakenan, 64 F. 2d 86 ...................... 7

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 59 S. Ct. 872 ............... 19, 25

Lehew v. Brummell, 15 S. W. 765 ................................ 11

Leland v. Morrison, 92 S. C. 501, 75 S. E. 889 . 6

Loring v. Frue, 104 U. S. 223 ................ 7

Love v. City of Dallas, 40 S. W. 2d 2 0 .......................... 13

McCabe v. Atchison T. & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151,

35 S. Ct. 69 .................................................................. 25

McLaurin v. Board of Regents of Oklahoma, 338 U.

S.........., 70 S. Ct. 851 .................................................. 26

Martin v. Marks, 97 U. S. 345 ..................................... 6

Mills v. Board of Education City of Norfolk, 30 F.

Supp. 245 ...................................................................... 24

Mendez v. Westminster School District, 64 F. Supp.

544, Affirmed 161 F. 2d 774 .............................. 17, 23, 27

Mitchell v. U. S., 313 U. S. 80, 61 S. Ct. 873 ............. 25

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 59

S. Ct. 232 ...................................................................... 25

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 47 S. Ct. 446 ......... 25

Parkerson v. Thompson, 164 Ind. 609, 73 N. E. 109 6

Pennsylvania Casualty Co. v. Upchurch, 139 F. 2d

892 ................................................................................ 21

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354, 69 S. Ct. 536 ....... 24

Pound v. Turck, 95 U. S. 459 ......................................... 8

Redfield v. Parks, 130 U. S. 632, 9 S. Ct. 642 ........... 7

Sigal v. Wise, 114 Conn. 297, 158 A. 891 .................... 21

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, Oklahoma, 332 U. S.

631 ................................................................................ 26

State v. Gordon, 32 N. D. 31, 155 N. W. 59 ................ 7

Southern Pipe Line Co. v. Empire Natl. Gas Co., 33

F. 2d 248 ...................................................................... 6

Strauder v. West Virigina, 100 U. S. 303, 25 L. Ed.

664 ................................................................................ 24

Treemond Co. v. Schering, 122 F. 2d 702 ....................... 22

Vistal v. Little Rock, 54 Ark. 321, 15 S. W. 891 ....... 7

U. S. v. Clark, 20 Wall. (U. S.) 9 2 ................................. 6

Wright v. Board of Education City of Topeka, 248 P.

363 ................................................................................ 12

iv Cases Cited— (Continued)

Page

Cases Cited— (Continued) v

Page

Weil v. Federal Life Ins. Co., 264 111. 425, 106 N. E.

426 ................................................................................. 7

Witcomb v. Witcomb, 85 Vt. 76, 81 A. 9 7 .................... 6

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 6 S. Ct. 1064 18

Yu Cong Eng v. Trinidad, 271 U. S. 500, 46 S. Ct.

619 ................................................................................. 18

Zimmerman v. Harding, 227 U. S. 489, 33 S. Ct. 387 8

Bochard, Declaratory Judgments, pp. 422-23 .......... 21

Statutes Cited

Federal Statutes:

Judicial Code, Sections 24(1) and 24(14)

Title 8 of the United States Code, Sections 41 and 43

Title 28 of the United States Code, Sections 41(1)

and 41(14)

State Statutes:

Vernon’s Texas Statutes, 1948:

Article 2681

Article 2695

Article 2696

Article 2697

Article 2698

Article 2699

Article 2922-13

In the

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 13,369

S. W. Mills, et al, individually and as members of the

Board of Trustees for the Euless, Tarrant County,

Texas Independent School District No. 95, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

Roscoe Woods, Jr., and his father and next friend,

Roscoe Woods, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

STATEM ENT OF THE CASE

On October 11, 1949 plaintiffs herein filed their original

complaint against the Superintendent of Schools and the

School Board of the Euless Independent School District,

against 0. H. Stowe, County Superintendent of Schools

of Tarrant County, Texas in which county the Euless In

dependent School District and the Fort Worth School Dis

trict are situated, and against Joe P. Moore, Superintend

2

ent of Schools, and the School Board of the Fort Worth

Independent School District setting out the jurisdiction of

the Court under the Judicial Code, Section 24(1), [28

U. S. Code, Section 41(1 )] and Title 8, Sections 41 and

43 of the U. S. Code.

The plaintiffs below, appellees here, further contend that

the lower court had jurisdiction under Section 24(14) of

the Judicial Code [28 U. S. Code, Section 41(14)], this

being a case of alleged discrimination against the plain

tiffs below, all of whom are admitted to be members of

the Negro race and citizens of the United States, citizens

of the State of Texas and domiciled in Tarrant County,

Texas and within the Euless Independent School District,

because of race and color.

The plaintiffs alleged in their complaint, and it was ad

mitted at trial that all of the parties to this law suit were

subject to the jurisdiction of the court below.

Plaintiffs allege that the defendants named herein, act

ing as officers and agents of the State of Texas had dis

criminated against them by unlawfully closing the school

within the Euless Independent School District which had

formerly been operated for these plaintiffs and others

similarly situated, and transferring them, all of whom are

members of the Negro race, out of their home school dis

trict to the Fort Worth Independent School District, a

distance of 15 or 16 miles away, while continuing to op

erate and maintain public school facilities for resident

white children of the district within the School District.

Plaintiffs prayed for a decree declaring the legal rela

tions to the parties to the cause, for a declaratory judg

ment and a writ of injunction permanently restraining the

defendants from further discriminating against these

plaintiffs and others similarly situated because of race and

color.

On October 31, 1949 defendants filed their original an

swer, to the plaintiffs’ original complaint, denying dis

crimination and declaring that the act of transferring the

plaintiffs out of their home district to an adjacent or con

tiguous district was done by authority of the law of the

State of Texas, and that the said act had been concurred

in by the County Superintendent and the State Superin

tendent of Education, and that certain indispensable par

ties should be joined as necessary parties to this cause.

The other defendants, except one, answered in substan

tially the same tone and adopted the answer of the de

fendant Euless Independent School District.

With the consent of the court, plaintiffs filed their First

Amended Complaint on December 2, 1949 joining other

necessary parties. The original complaint was amended in

no other respect.

Defendants stood on their original answer contending

that their act of transferring plaintiffs and others simi

larly situated was done according to the laws of the

State of Texas. They admit plaintiffs’ allegations that a

public school had been maintained for many years within

the Euless Independent School District; that the school

4

vy

£4/ \

V

for Negroes which had been previously maintained had

been closed and the pupils transferred to the Fort Worth

Independent School District.

Honorable L. A. Woods, State Superintendent of Edu

cation acting upon advice of the Attorney General’s office

filed his motion to be dismissed on the grounds that he

was not a proper party to the cause for the reason that

he had no authority _under thê Constitution of the State of

Texas, or any of the laws thereunder, to grant or accom

plish the relief prayed for by the plaintiffs. And for the

further reason that under the Statutes of the State of

Texas, he had no authority with regard to contracts for

the transfer of the scholastics, such as the one which was

allegedly made between the Euless Independent School

District and the Fort Worth Independent School District.

Argument on this motion was had on March 20, 1950,

and an order was entered by the court on that date dis

missing Dr. Woods as a party, on the ground that the

defendant, Dr. L. A. Woods has no power under the Con

stitution of laws of this State to grant or accomplish any

of the relief prayed for by the plaintiffs, and that the

said defendant has no authority with regard to contracts

for the transfer of scholastics such as the one allegedly

made between the Euless Independent School District and

the Fort Worth Independent School District. (See Ap

pendix III, p. 34.)

The cause came on for trial before Honorable Joseph

B. Dooley, United States District Judge, without jury, on

the 20th day of March, 1950, where upon hearing the testi-

THE W ASH IN G TO N POST,

Wednesday, Hay 30, 1951 *** g

Judges Get

Segregation

Case in S, C. ,

CHARLESTON, S, C.. May 29

<U-R),...Negro leaders asked a fe d

eral court today to end school seg

regation that amounts to "exclu

sion” while South Carolina argued

that the right to separate the

races belongs to the State.

As both sides wound up their

cases in a suit aimed at the

South’s basic segregation pattern,

one of the three special United

States judges said he was "not

much mipdessed” with the state’s

main plea.

Circuit Judge John J. Parker,

Senior jurist on the panel, asked

State Attorney Robert McG. Figg,

what decree he thought the court

should render sonce the State ad

mitted it did not provide equal

school facilities for Negroes in

Clarendon County, where the suit

originated.

Figg then repeated his request

of yesterday that the special court

hold the case within its jurisdic

tion until the State had time to

put into effect a multi-million dol

lar school equalization program.

I’m not much impressed with

that,” said Judge Parker. He added

that he knew of no point of law to

support such a course.

Judge Parker, was hearing the

case with District Judges J. Waties

Waring and George Bell Timmer

man. Waring is the South Carolina

judge who opened the South Caro

lina primary to Negro voters in

1947 and Parker was a member of

the Circuit Court of Appeals in

Charlotte, N. C., that hacked him

up.

The judges took the case under

advisement. No matter which side

wins, a prompt appeal probably

will be taken to the United States

Supreme Court.

Witnesses for the plaintiffs—

parents of 30 Clarendon County

Negro pupils—expanded their con

tention that segregation itself rep

resents unequal education because

it gives the negro a feeling of in

feriority.

TH E W ASH ING TO N POS'I

Wednesday, May 30, 1951

1 0 ___________________ * * *

Pepco Earns

36c a Share

In 4 Months

By S. Oliver Goodman

Potomac Electric Power Co.

yesterday reported net income of

$1,675,000 or 36 cents a share for

the first four months of this year,

compared with $1,628,000 or 42

cents a share in the same 1950

period. A lesser number of com

mon shares was outstanding last

year.

April net income of $373,000

was 2.1 percent, under the like

1.950 period. Effect of the rate

increase, which went into effect

on April 20, is expected to be re

flected in the earnings report for

May.

.. Operating revenues for the four-

month period totaled $13,606,000,

a gain of 8.1 percent , while oper

ating expenses of $11,112,00 in

creased 9.4 percent.

Total plant investment at the

end of April amounted to 181 mil

lion dollars, the company noted,

an increase of 13 million over a

year ago. Gross additions to plant

during the first four months aggre

gated $5,683,000.

INNOVATION: To speed np

the cashing of checks, the Amer

ican Security & Trust Co. will

place in operation on Thurs

day in its main office a new-type

’machine. It will dispense rolls

of currency. Any coin involved

is served in the usual manner.

The Burroughs Adding Machine

Co, has built several experimen

tal models to test customer re-

- action throughout the Nation.

Two machines will he In op

eration at A. S. & T. through

June 5.

; WHO’S NEWS: William A.

Boone, former field supervisor of

Aetna Casualty &

assumed duties as

Surety Co., has

manager of the

firm’s Wa s h -

in g t o n office.

He s u c c e e d s

Guy E. Mann,

who has been

named mana

ger of the com

pany’s Boston

office . . . Carl

ton H. Rose

5

mony given and the argument of counsel, the judgment and

decree appealed from was entered on June 17, 1950.

(R. 38.)

Plaintiffs below, Appellees herein contend that the judg

ment and decree should be sustained.

We shall discuss the issues herein as set out below.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

Appellants’ appeal should be dismissed on the basis of

the record before this court.

II.

The transfer of these Negro scholastics and others whom

they represent from their home school district, while main

taining public school facilities within the home school dis

trict for white scholastics, was made contrary to the laws

of the State of Texas and the laws of the United States.

III.

The plaintiffs below were entitled to a declaratory judg

ment setting out the laws of the State of Texas and of

the United States and declaring the legal relations of the

parties hereto.

w .

This being a case of alleged illegal discrimination against

the Negro plaintiffs herein and those whom they repre

sent, on account of their race and color, by the defendants

herein, while acting as agents of the State of Texas, the

trial court had jurisdiction to try this cause.

6

ARGUM ENT

I— (Restated)

Appellants’ appeal should be dismissed on the basis of

the record before this court.

Where an appellate court is called upon to review a judg

ment rendered in a court of equity or in an action at law

which has been tried before a court without a jury, the

appellate court will indulge in every reasonable presump

tion in favor of the findings made by the lower court upon

which it rendered judgment.

Martin v. Marks, 97 U. S. 34,5;

U. S. v. Clark, 20 Wall. (U. S.) 92;

Hodges v. Merriweather, 55 F. 2d 29;

Southwest Pipe Line Co. v. Empire Natural Gas,. S3

F. 2d 248;

Cooke v. Wilbanks, 223 Ala. 312, 135 So. 435;

Parkerson v. Thompson, 164 Ind. 609, 73 N. E. 109;

Blakenbary v. Comm., 273 Mass. 25, 172 N. E. 209;

Greer v. Standard, 85 Mont. 78, 277 P. 622;

Daily v. Fitzgerald, 17 N. M. 137, 125 P. 625;

Amherst College v. Ritch, 151 N. Y. 282, 45 N. E. 876;

Leland v. Morrison, 92 S. C. 501, 75 S. E. 889;

Whitcomb v. Whitcomb, 85 Vt. 76, 81 A. 97;

Heck v. Hiech, 163 Wis. 171, 157 N. W. 747.

The presumption is that the evidence was sufficient to

support the findings made and to justify the conclusions

reached, especially where the record includes none of the

evidence submitted at trial.

7

Klaber v. Lakenan, 64 F. 2d 86;

Vestal v. Little Rock, 54 Ark. 321, 15 S. W. 891;

Canal Bank v. Hudson, 111 U. S. 66;

Federal Surety Co. v. Butler & Son, 51 F. 2d 21+;

Gernard v. Hasmer, 285 Mass. 259, 186 N. E. 46.

An appellate court can look only to the record to ascer

tain what evidence was submitted to the trial court, and

to determine the validity and reasonableness of the find

ings and conclusions of the court below.

Davis v. Packard, 7 Pet. (U. S.) 276;

State v. Gordon, 32 N. D. 31, 155 N. W. 59.

The right and duty of the appellate court to consider the

cause must be apparent on the face of the record.

Elgin v. Marshall, 106 U. S. 578, 27 L. Ed. 21+9.

The party seeking relief in the appellate court must

show by the record the commission of the errors by the trial

court of which the movant complains.

Redfield v. Parks, 130 U. S. 632, 9 S. Ct. 642.

Where the record is silent the appellate court will pre

sume that what ought have been done by the court below

was done, and that what was done, was rightly done.

Hahn v. Kelley, 34 Calif. 391;

Weil v. Federal Life Insurance Co., 264 HI- 425, 106

N. E. 246;

Loring v. Frue, 104 U. S. 223;

Bechtel v. U. S. 101 U. S. 597;

8

Baltimore & P. Ry. Co. v. Sixth Presbyterian Church,

91 U. S. 127;

Kerney v. Dean, 15 Wall. (U. S.) 51.

This presumption arises when the record does not pur

port to contain the evidence that was before the court below.

Zimmerman v. Harding, 227 U. S. 489, 33 S. Ct. 387;

Durland v. U. S. 161 U. S. 306, 16 S. Ct. 508;

Pound v. Turck, 95 U. S. 459.

The Appellant has the burden of showing to the appel

late court that the evidence produced in court was not suf

ficient to support the judgment of the trial court.

Dowd v. Hercules Power Co., 66 Colo. 302, 181 P.

767.

The premises considered, Appellees respectfully submit

that the Appellants’ appeal should be dismissed on the basis

of the record before the court.

II— (Restated)

The transfer of these Negro scholastics and others whom

they represent from their home school district, while main

taining public school facilities within the home school dis

trict for white scholastics, was made contrary to the laws

of the State of Texas and the laws of the United States.

The record before this Court reveals on its face that the

trial court found as a Finding of Fact, based upon the

testimony given at trial, that the defendant school board

is a duly constituted school district for the purposes of pub

lic education; that in the school year 1948-1949 said school

9

district maintained schools for both white and colored

scholastics and had so maintained such schools for some

years before that time; that during the school year 1948-

1949 there were more than forty Negro scholastics in de

fendant school district (R. 30), and that the defendant

school district closed the Negro school and has not pro

vided any public school facilities within the said district

for Negroes since that time. (R. 31.)

In Paragraph XIV of appellants’ answer, they admit

that they have maintained and are now maintaining pub

lic schools within the said school district for white scho

lastics. (R. 25.)

It was the contention of Appellees that the closing of the

Negro school and the transfer of the Negro Scholastics to

the schools of Fort Worth, Texas, which is outside their

home district, in the manner that the transfer complained

of was made, was contrary to the laws of Texas and of

the United States.

The trial court agreed with Appellees and found as a

Conclusion of Law that the Trustees of the Euless Dis

trict had no legal authority to undertake an involuntary

transfer of only the Negro scholastics from their home

district for the purposes of attending school. In this re

spect the trial court concurred in a ruling of the Attorney

General of Texas on this same question and made the

ruling of the Attorney General a part of the record of this

trial. (R. 36.)

In their answer and at trial, Appellants contended that

the transfer complained of was made according to the laws

10

of Texas. Apparently they have abandoned that contention

in this Court. (R. 27.)

In their brief, Appellants cite three cases, none of which

are Texas cases, to support their proposition that the trans

fer was legal, but no where do they point to any Texas

case or statute to support their proposition.

In each of the cases cited by Appellants, separate or

segregated schools were maintained for white and colored

scholastics. In each instance the transfers made were from

schools which were within the jurisdiction of the school

authorities who made the transfer, to schools within the

jurisdiction of the authorities making the transfer.

In Dameron v. Bayless, 126 P. 273 (Ariz.), 1912, which

is cited by Appellants, the action was by a Negro parent

to enjoin the school board from enforcing compulsory

school attendance laws and thus compelling him to send his

two children to a segregated school which had been pro

vided for Negroes within the school district of Phoenix,

Arizona.

His children had formerly attended the schools for white

children within the said district.

At that time the laws of Arizona provided that when

the number of Negro scholastics within the district ex

ceeded eight, the school board in such district had au

thority to provide separate schools for Negroes.

There were eight or more Negroes within the Phoenix

School District and a separate school for Negroes had been

provided. The trial court found that the facilities of the

Negro school were equal to or superior to those in the

white school, but that the Negro children had to travel

a greater distance to reach their school than white chil

dren had to travel, and enjoined the transfer.

Reversing this the appellate court held that the matter

of nearness of schools to the homes of the pupils had no

place in determining the adequacy and sufficiency of the

school facilities furnished within the school district.

In Lehew v. Brummell, 15 S. W. 765 (Mo.) 1891, ac

tion was by five white parents of District Four of Grundy

County, Missouri, against the school board and the teachers

of the school district to enjoin them from teaching Negro

children in the white schools. Brummell, a Negro parent

was joined in the suit because he had four children of

public school age and he was the only Negro parent in

the school district.

Missouri laws provided at that time for separate or

segregated schools for white and Negro children, provided

that there were fifteen Negro children of school age within

the school district to justify the operation of a Negro school.

It was further provided that when there were less than

fifteen Negro children of public school age within the

school district, the Negro children may attend any school

in any school district within the county where a school for

Negroes was operated.

There was a school for Negroes in an adjoining district

which was three and one-half miles from Brummell’s home.

No white child in the district had to travel more than two

miles to reach school, but the court held that this dif

12

ference in distance was not sufficient grounds to avoid the

laws of the State, and that this greater distance did not

foul the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

In Wright v. Board of Education of the City of Topeka,

28h P. 863 (Kans.) 1930, the action was by a Negro parent

to enjoin the Board of Education from interfering with the

attendance of his daughter at the school for white chil

dren at which she had formerly attended.

Kansas law then provided that in cities of first class

(over 60,000 population), the Board of Education had au

thority to provide separate schools for white and Negro

children of public school age. Topeka was a city of the

first class and under the law, the Board provided separate

schools for the races. There was no equation of the rela

tive equality of the schools for white and Negro children.

But the plaintiff’s child had to travel approximately

twenty city blocks to the Negro school while the school at

which she had previously attended was within a few blocks

of her home. It was under these circumstances that the

court held that the difference in distance was not unreason

able and denied the relief sought.

It is significant that in each of the cases cited by Appel

lants, the transfers complained of where made strictly

according to the laws of the states in which they occurred.

In the instant case, it has been the contention of Appellees

that the transfer complained of was not made according

to Texas law, and the trial court so found as a matter of

law. (R. 35.)

13

Texas Law

Under the prevailing law of Texas the transfer of

scholastics from one school district to another school dis

trict can be made only under the transfer statutes of the

State of Texas.

In Love v. City of Dallas, 40 S. W. 2d 20, Chief Justice

Cureton, speaking for the Supreme Court of Texas said:

“ It is clear, we think, from a consideration of the

various transfer statutes cited above, including the

quoted provision from Article 2681, that scholastics

cannot be transferred, under any circumstances, from

the district in which they reside to another district,

except under the transfer statute.”

The transfer statutes of the State of Texas are set out

in the appendix. (See Appendix, p. 36.)

The new Foundation School Program of Texas, com

monly known as the Gilmer-Akin Bill, which became ef-

fective in June, 1949 provides for transfers by contract

for one year under Article 2922-13:

“ * * * Provided further, that any school district

which is not a dormant school district, * * * subject

to the approval of the boards of trustees of the dis

tricts concerned, the County Superintendent and the

State Commissioner of Education, may contract for

a period of one year to transfer its entire scholastic

enrollment, both white and colored, to a contiguous

district.”

Except as provided above, and in the appendix, no trans

fer of a scholastic or scholastics may be properly made

under the statutes and laws of Texas.

14

This proposition has been ruled upon by an opinion of

the Attorney General of Texas, which ruling has been made

a part of the record of this suit by the trial judge. (R. 36.)

See also ruling by Judge Dixon, District Judge, Dallas

County, Appendix I, p. 29.

The trial court found as a matter of fact that the trans

fer complained of by these Appellees was made by the

Appellants without any request or approval by the parents

of these Appellees and that they did not acquiesce in the

transfer and that almost without exception they objected

to sending their children to the Fort Worth School Dis

trict and in fact refused to send their children to public

school at all during the school year 1949-1950, but sent

them to a private school in the community. (R. 31-32.)

The record shows further that there were more than 20

scholastics in the district (R. 30), the record fails to show

the existence of any emergency, or excessive distance or

that a school was not accessible, or that the Euless Inde

dependent School District is in two or more counties or on a

county line, or that all of the children, white and colored,

were transferred.

It is to be observed that the transfer in the instant case

does not fit into any of the transfer provisions set out

above and Appellants have not pointed to any Article or

statute in the Texas law under which it does fall. Therefore

the appeal should be dismissed on the record.

Distance

Appellants suggested in their brief, and properly so, that

Appellees would regard the case of Corbin v. County

15

School Board of Pulaski County, Virginia, 177 F. 2d 924,

decided by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals as being an

authority for their position.

Appellees contend that the Corbin case is authority for

the holding in this case.

In the Corbin case the court said at page 927:

“ Negro pupils in Pulaski County, wherever they

may live, can attend only the Christianburg In

stitute in Montgomery County. These Negro children

are transported in two busses, each of which, with

many stops, travel around 60 miles per day. Negro

children must thus leave home earlier in the morning,

endure a longer ride and arrive home later than the

white children. No shelters are provided for Negro

children who must assemble at points from which they

board the bus. In inclement weather, this is a real

hardship and inconvenience. The Negro pupils and

their parents, whose social and economic activities

must be arranged accordingly, are amply brought

out in the evidence. Owing to the longer ride, as com

pared with white high school students, Negro children

must forego many healthful activities at school and

have less time for study, recreation and play. The toll

thus imposed on Negro students and their parents is

both real and severe

In that case the court held 60 miles of travel per day

to be unreasonable and that such travel placed a dispropor

tionate burden upon the Negro children and their parents.

It will be observed by the court that those were high school

children. In the case at bar, the children involved are ele

mentary school children, of tender years, ranging from six

to fourteen years of age.

16

It does not seem out of harmony with the Corbin case to

contend that the travel of a daily distance of 32 miles, by

these delicate infants, many of whom were away from the

care of their mothers for the first time, is unreasonable.

In Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, Virginia,

182 F. 2d 531 (Advance Sheet of August 7, 1950), the

court reaffirmed its position in the Corbin case and said:

“ In further defense of the failure to furnish certain

courses to the students at Hoffman-Boston, it is

pointed out that the school authorities of Arlington

County have adopted the policy of sending Negro vo

cational pupils to the Manassas Regional school which

is situated twenty-five miles distant in Prince Wil

liam County, Virginia. Only one Negro student has

availed himself of this opportunity. It does not offer

in our opinion an equivalent advantage for colored

students desiring courses which are given to white

students at Washington-Lee in Arlington County. We

had occasion to consider a similar situation in Corbin

v. School Board of Pulaski County, 177 F. 2d 924,

where the inconvenience and loss of time imposed by

transportation to the regional school were pointed

out.” (Paragraph 1, p. 534.)

Speaking of the various forms of discrimination shown

in the Carter case, the court said further:

“ * * * and it is no defense that they flow in part

from variations in the size of the respective student

bodies or locations of the buildings. The burdens in

herent in segregation must be met by the state which

maintains the practice. Nor can it be said that a

scholar who is deprived of his due must apply to the

administrative authorities and not to the courts for

relief (Page 536).”

17

Arbitrary Discrimination

A school board may not use its powers, prerogatives or

authority to arbitrarily discriminate against particular

scholastics under its supervision and control.

Independent School District v. Salvatierra (Tex.), 33

S. W. 2d 790;

Mendez v. Westminster School District (Calif.), 61

F. Supp. 5U, Affirmed, 161 F. 2d 771.

In the Salvatierra case, the Texas Court of Civil Ap

peals held that:

“ School authorities have no power to arbitrarily

segregate Mexican children, assign them to separate

schools, exclude them from schools maintained for

children of other white races, merely or solely because

they are Mexicans.”

In the Mendez case, the United States Circuit Court of

Appeals, Ninth Circuit, held:

“ * * * We are aware of no authority justifying any

segregation fiat by an administrative or executive

decree as every case cited to us is based upon a

legislative act. The segregation in this case is with

out legislative support and comes into fatal collision

with the legislation of the state.” (p. 780.)

No contention was made at trial, nor could any be made,

that Appellees and those whom they represent would not

have been admitted to the schools maintained within the

Euless Independent School District for white children,

if they had not been Negroes. This being true, it follows

that the unlawful discrimination enforced against Appel

18

lees by transferring them out of their home district to

the Fort Worth, Texas School District was done solely and

only because of their race and color. But for their color,

there was a school within the district to serve them.

t e *

In classifying these Appellswte as the class of children

to be transferred out of the home district to a foreign

school district, the classification was one based solely on

race and color. Such classifications come into fatal col

lision with the Constitution and laws of the United States.

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 856, 6 S. Ct. 1064,;

Yu Cong Eng v. Trinidad, 271 U. S. 500, 46 S. Ct.

619;

Hirabayashi v. U. S., 320 U. S. 81, 63 S. Ct. 1375;

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400, 62 S. Ct. 1159.

In the Hirabayashi case, Mr. Chief Justice Stone said,

at page 1385:

“ Distinctions between citizens solely because of their

ancestry are by their very nature odious to a free

people whose institutions are founded upon the doc

trine of equality. For that reason, legislative classi

fication or discrimination based on race alone has

often been held to be a denial of equal protection.”

Sophisticated Discrimination

The Negro school was in a woeful state of repairs and

of exceedingly low standard, so much so that the state

authorities had threatened to remove the accredited status

from the entire school district because of the low standards

at the Negro school.

It was to avoid this eventuality that the Negro children

were transferred to the Fort Worth Independent School

District.

The trial court found as a matter of fact that the

transfer of the Negro sfucfents resulted in, “ more public

funds to provide a better and improved white school.” (R.

32.) See Amended Finding of Fact, VII, page 46 of the

record.

This is a sophisticated form of discrimination, but one

which was destined to bring the defendant school district

into fatal conflict with the law.

Where the State of Oklahoma resorted to a clever device

to thwart equality in the enjoyment of the right to vote,

the Supreme Court of the United States struck down their

efforts, saying:

“ The Amendment (Fifteenth) nullifies sophisti

cated as well as simple-minded modes of discrimina

tion.”

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U, S. 268, 59 S. Ct. 872.

Lack of funds is no defense against proof of failure to

provide facilities for both races in a segregated school

system.

Ashley v. School Board of Gloucester County, Vir

ginia, 82 F. Supp. 167.

In the Ashley case, Judge Hutcheson, speaking for the

court said:

“ I am aware of the familiar contentions that fi

nancial difficulties facing the counties in the effort

20

to equalize facilities and opportunities for the races

are so great as to raise doubt as to their ability to

do so; and that the greater portion of the tax burden

falls upon the white population. While I am not un

mindful of the practical problem presented, a super

ficial consideration of these suggestions is sufficient

to bring a realization that under the prevailing law

neither has any bearing upon the legal and factual

questions here involved.” (p. 171.)

The premises considered, Appellees submit to the court

that the transfer of these Negro scholastics and those

whom they represent from their home rural Independent

School District while maintaining public school facilities

for white scholastics within the home rural Independent

School District was done contrary to the laws of the

State of Texas and the laws of the United States and the

judgment and decree of the court below should be affirmed.

Ill— (Restated)

The plaintiffs below were entitled to a declaratory judg

ment setting out the laws of the State of Texas and of

the United States and declaring the legal relations of the

parties hereto.

In their complaint filed herein, Appellees prayed for a

declaratory judgment and injunctive relief. Upon the evi

dence presented to the trial court the declaratory judg

ment prayed for was granted. Appellees respectfully sub

mit that the trial court was not in error in granting the

declaratory judgment for which Appellees prayed.

The purpose of declaratory procedure is to remove un

certainty from legal relations and clarify, quiet and stabil

21

ize them before irretrievable acts have been undertaken,

and also to enable an issue of questioned status or fact, on

which a whole complex of rights may depend, to be ex

peditiously determined.

Dalandy v. Carter Oil Co., 174, F. 2d 314, Certiorari

denied, 338 U. S. 824, 70 S. Ct. 71;

American Machine and Metals v. DeBothezat Impel

ler Co., 166 F. 2d 535.

In the American Machine case, it was said that:

“ Where there is an actual controversy over con-

tigent rights, a declaratory judgment may neverthe

less be granted.”

Pennsylvania Casualty Co. v. Upchurch, 139 F. 2d

892;

Franklin Life Insurance Co. v. Johnson, 157 F. 2d

653;

Sigal v. Wise, 114 Conn. 297, 158 A. 891;

Bochard, Declaratory Judgments, pp. 422-23.

In Dewey & Almy Chemical Co. v. American Anode, 137

F. 2d 69, the court said:

“ In providing the remedy of a declaratory judg

ment it was the Congressional intent to avoid accrual

of avoidable damages to one not certain of his rights

and to afford him an early adjudication without wait

ing until his adversary should see fit to begin suit,

after damages had accrued. E. Edelman & Co. v.

Triple-A Specialty Co., 88 F. 2d 852, 854. This Court

has emphasized that the Act should have a liberal

interpretation, bearing in mind its remedial character

and the legislative purpose.”

Hoffman v. Knitting Machines Corp., 123 F. 2d 4.56;

Treemond Co. v. Schering Corp., 122 F. 2d 702.

In the case at bar Appellees’ school had been closed by

the defendants herein without the consent of the Appellees

and their community was entirely devoid o f any school to

which they could attend. They had refused to acquiesce

in such arrangement. They were uncertain of their rights

and of the authority of the defendants to enter into the

arrangement for the transfer.

Appellees respectfully submit that the premises con

sidered and the authorities cited the trial court was not

in error in rendering a judgment declarative of the rights

of the parties and definitive of their legal relations and

the judgment of the trial court should be sustained.

IY— (Restated)

This being a case of alleged illegal discrimination against

the Negro plaintiffs herein and those whom they repre

sent, on account of their race and color, by the defendants

herein, while acting as agents of the State o f Texas, the

trial court had jurisdiction to try this cause.

In their First Amended Complaint filed herein, plain

tiffs below, Appellees here, claimed jurisdiction under

Title 28 of the United States Code, Section 41(14), now

Title 28 U. S. C. Sec. 1343, and further claimed jurisdic

tion under 8 United States Code, Sections 41 and 43, seek

ing to redress the deprivation, under color of law, of rights

and privileges secured to them by the Constitution of the

United States.

23

They contended then, and they now contend, that the

failure and refusal of the defendant Euless Independent

School District, its officers and agents, who were and are

now agents of the State of Texas, to provide and main

tain public school facilities for these Negro Appellees under

their supervision and control, within their home school

district while maintaining and providing such public

school facilities for white scholastics under their super

vision and control was a denial of a civil right and a denial

of equal protection under the law and a denial of rights

and privileges secured to them by the Constitution and laws

of the United States.

In such cases the amount in controversy is not a pre

requisite to an action.

Bottone v. Lindsley, 170 F. 2d 705.

In such cases diversity of citizenship is not a pre

requisite to an action.

Bottone v. Lindsley, supra;

Gordon v. Garrson, 77 F. Supp. 177.

In Westminster School District v. Mendez, 161 F. 2d

771 at page 778, the court said:

“ It is said in Bell v. Hood, 327 U. S. 678, 66 S. Ct.

773, that * * * the court must assume jurisdiction to

decide whether the allegations state a cause of action

on which the court can grant relief as well as deter

mine issues of fact arising in the controversy. There

fore the court was correct in taking jurisdiction.”

The Westminster case was a case of alleged racial dis

crimination by a California school board. Many federal

courts have exercised jurisdiction in similar matters as

the cases set out below will demonstrate.

In Mills v. The Board of Education of Anne Arundel

County (Md.), 30 F. Supp. 245, where the action was by

a Negro public school teacher to enjoin and prohibit the

Board of Education from paying him a lesser salary be

cause of his race and color than was paid by the Board to

white public school teachers with the same training and

experience. In holding that a discrimination as to pay of

teachers in white and colored schools was violative of the

constitutional provision, Judge Chestnut said: “ * * * that

a colored teacher might invoke the poioer of the court to so

declare.”

This is in accord with a long line of cases and decisions

which have condemned discrimination on account of race

or color in the exercise of governmental power by a state

or its agencies.

The exclusion of Negro persons from service on petit

juries was condemned as violative of the constitutional

provision.

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 25 L. Ed.

66V

The exclusion of Negroes from grand juries was con

demned as violative of the federal constitution.

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354, 69 S. Ct. 536.

Discrimination on account of race or color was con

demned as violative of the federal constitution where Ne-

25

groes were denied the right to participate in party

primaries.

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 17 S. Ct. 116;

Baskin v. Brown, 17b F. 2d 391;

Elmore v. Rice, 165 F. 2d 387.

Discrimination on account of race or color was con

demned as violative of the federal constitution where Ne

groes were denied the right to participate in elections.

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 59 S. Ct. 872.

Denial by city ordinance of the right to Negroes to own

and occupy property was condemned as violative of the

federal constitution.

Buchanan v. Warley, 215 U. S. 60, 38 S. Ct. 16.

Discrimination by the state with respect to providing

pullman accommodations for Negroes was condemned as

violative of the federal constitution.

McCabe v. Atchison & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151, 35

S. Ct. 69;

Mitchell v. U. S., 313 U. S. 80, 61 S. Ct. 873.

Discrimination because of race and color in failing to

provide educational facilities within the state was con

demned as violative of the federal constitution.

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 59

S. Ct. 232.

26

Discrimination on the basis of race or color in failing

to provide facilities within the state at the same time

that they were provided for white persons was condemned

as violative of the federal constitution.

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of Oklahoma, 332 U. S.

631.

Discrimination in seating arrangement within the class

room, in the library and in the cafeteria at the University

of Oklahoma on the basis of color and race was condemned

as violative of the federal constitution.

McLaurin v. Board of Regents of Oklahoma, 338 U.

S.........., 70 S.Ct. 851.

Discrimination in the seating arrangement on dining

cars on the basis of race was condemned as violative of the

federal constitution.

Henderson v. U. S., 338 U. S. , 70 S. Ct. 81,3.

Discrimination in providing courses and educational fa

cilities on the basis of race and color was condemned as

violative of the federal constitution.

Corbin v. School Board of Pulaski County, Virginia,

supra;

Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, supra;

Butler v. Wilemon, 86 F. Supp. 397;

Johnson v. Board of Trustees of Univ. of Ky., 83 F.

Supp. 707.

27

Discrimination on account of race and color in assign

ing scholastics to schools was condemned where Mexicans

were segregated unlawful in California and Texas.

Mendez v. Westminster School District, 64 F. Supp.

544, Affirmed 161 F. 2d 774;

Independent School District v. Salvatierra (Tex. Civ.

App.), supra.

Underlying all of these decisions is the principle that

the constitution of the United States, in its present form,

forbids, so far as civil and political rights are concerned,

discrimination by the general government, or by the states,

or by the agencies thereof, against any citizen because of

his race or color.

It is a fundamental tenet of our government that all

citizens are equal before the law.

The protections of life, liberty and property are for all

persons within the jurisdiction of the United States, or of

any state, without discrimination against any because of

race or color.

Those rights and guaranties, when their violation is

properly presented in the regular course of proceedings,

must be enforced in the courts, both of the nation and

of the states, without references to considerations based

upon race.

Alston v. School Board of the City of Nor fork, 112

F. 2d 992.

28

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth herein, Appellees respectfully

submit that the judgment of the court below should be

affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

U. Simpson Tate,

1718 Jackson Street,

Dallas, Texas.

C. B. Bunkley, Jr.,

814% North Good Street,

Dallas, Texas,

Attorneys for Appellees.

A copy of this brief has been delivered to M. Hendricks

Brown, Esq., Attorney for Appellants on this the 27th

day of October, 1950 by mailing one copy postage paid to

his office, 502 Burk Burnett Building, Fort Worth 2,

Texas.

Of Counsel.

29

APPEN D IX I.

IN THE

DISTRICT COURT

IN AND FOR THE 95TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT,

DALLAS COUNTY, TEXAS

No. 39845-D

E. C. BAGSBY, EUGENE ROBINSON

AND EDWARD RADFORD

V.

DISTRICT TRUSTEES OF PLEASANT GROVE IN

DEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT OF

DALLAS COUNTY, TEXAS

JUDGMENT .

On the ....... day of February, A. D. 1950, in the above

entitled and numbered cause, wherein E. C. BAGSBY,

EUGENE ROBINSON and EDWARD RADFORD are

Plaintiffs, and the DISTRICT TRUSTEES OF PLEAS

ANT GROVE INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT OF

DALLAS COUNTY, TEXAS are defendants, came all

parties in person and by their attorneys of record and an

nounced ready for trial; whereupon, a jury being waived,

and the cause having been submitted to the Court, and the

Court having heard the pleadings, the evidence and argu

ment of counsel, is of the opinion and so finds that the

material allegations contained in plaintiffs’ petition are

true; that the District Trustees of Pleasant Grove Inde

pendent School District of Dallas County, Texas are now

providing, within the said Pleasant Grove Independent

School District of Dallas County, Texas, full course ele

mentary and high school education for white children;

that the Kirby school for negro children was closed by

the said District Trustees, and that there is no school for

the education of negro children within the said district.

That the said District Trustees have failed to provide

within the said district, educational opportunities and fa

cilities for the education of negro children, residing within

the said district, equal to those now being provided for the

education of white children; and, that equal and impartial

•provision has not been made for the education alike of

white and colored children. That plaintiffs should be

awarded a writ of MANDAMUS.

The Court further finds that the acts of the said District

Trustees are in violation of the Constitution U. S., the

Constitution of Texas, and the laws governing public edu

cation in the State of Texas; and are a denial of the rights

of negro children to equal educational opportunities and

facilities within the said district.

IT IS THEREFORE ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND

DECREED BY THE COURT, that a WRIT OF MAN

DAMUS issue, directing and commanding the District

Trustees of Pleasant Grove Independent School District

of Dallas County, Texas, defendants herein, to forthwith

proceed with all reasonable dispatch, to provide and main

tain a school, as a full course elementary school for the

education of negro children; and to provide and maintain

within the Pleasant Grove Independent School District of

Dallas County, Texas, educational opportunities and fa

31

cilities for the education of negro children, equal to those

now being provided for white children.

It is further ordered, adjudged and decreed that plain

tiffs recover of defendants all costs expended in this be

half, for which execution may issue.

To which judgment defendants excepted in open Court

and gave notice of appeal to the COURT OF CIVIL AP

PEALS, 5TH SUPREME JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

TEXAS, at Dallas, supersedeas bond set at $500.00.

Signed March 4, 1950.

/ s / Dick Dixon

JUDGE

The State of Texas i

County of Dallas (

I, Bill Shaw, Clerk of the District Courts, in and for the

county of Dallas, and State of Texas, do hereby certify

that the above and foregoing is a true and correct copy of

Judgment in the above numbered and styled cause, as the

same appears of record in Book 34 page 294, of the Minutes

of the 95th Judicial District of Texas, in and for Dallas

County.

WITNESS: my official seal and signature, at office in

the City of Dallas, Dallas County, Texas, on this 17 day

of April 1950.

BILL SHAW

Clerk of the District Courts,

Dallas County,

(Seal) / s / Polly Chamberlain

Deputy

APPENDIX II.

No. 1898 CIVIL

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

FORT WORTH DIVISION

ROSCOE WOODS, JR., ET AL.,

V.

Plaintiffs,

0. H. STOWE, ET AL.,

Defendants.

MOTION OF CERTAIN DEFENDANT TO BE

DROPPED AS PARTIES AND FOR DIS

MISSAL AS TO HIM

Dr. L. A. Woods, Superintendent of Public Instruction of

Texas, defendant in the above cause, moves the Court as

follows:

1. For an order dropping him as party defendant herein

for the following reasons:

a. Such defendant has no power under the con

stitution of the State of Texas, or any of the Laws

thereunder, to grant or accomplish any of the relief

prayed for herein by the plaintiffs.

b. This defendant, by statute, has no authority

with regard to contracts for the transfer of scholas

tics, such as the one which was allegedly made be

tween the Euless Independent School District and the

Fort Worth Independent School District, and which

is the basis of this cause.

2. The defendant named in Paragraph 1 hereof moves

the Court to dismiss the action as to him because the com

plaint fails to state a claim against the said defendant upon

which relief could be granted.

PRICE DANIEL

ATTORNEY GENERAL OF

TEXAS

JOE R. GREENHILL

FIRST ASSISTANT ATTOR

NEY GENERAL

CHESTER E. OLLISON

ASSISTANT ATTORNEY

GENERAL

/&/ E. Jacobson

E. JACOBSON

ASSISTANT ATTORNEY

GENERAL

The foregoing notice has been served on the above-

named attorney for the plaintiffs by mailing the same to

him on this the 31st day of December, 1949.

34

No. 1898— CIVIL

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

FORT WORTH DIVISION

APPENDIX III.

ROSCOE WOODS, JR., ET AL.,

Plaintiffs,

V.

0. H. STOWE, ET AL.,

Defendants.

ORDER TO DROP CERTAIN DEFENDANT AS A

PARTY AND TO DISMISS AS TO HIM

This cause came on to be heard at this term, upon de

fendant’s, Dr. L. A. Woods, motion to he dropped as a

party defendant and for dismissal as to said party of

plaintiffs’ complaint, on the ground that defendant, Dr.

L. A. Woods, has no power under the Constitution or

laws of this State to grant or to accomplish any of the re

lief prayed for by plaintiffs; further, that the said de

fendant has no authority with regard to contracts for the

transfer of scholastics, such as the one allegedly made be

tween the Euless Independent School District and the Fort

Worth Independent School District, the basis of this cause,

and was argued by counsel; and thereupon, upon considera

tion thereof, it was ORDERED, ADJUDGED, and DE-

35

CREED that said motion be sustained and that the defend

ant, Dr. L. A. Woods, recover his costs and that the plain

tiffs be adjudged to pay all costs incurred in this cause

as to said defendant, for which let execution issue.

DATED March 20, 1950

/ s / Jos. B. Dooley

Jos. B, Dooley, District Judge

APPENDIX IV.

VERNON’S TEXAS STATUTES 1948 EDITION

- Title 49— Education— Public

Chapter 11-—Paragraph 2— Superintendent

Article 2681. School districts..— * * * In providing bet

ter schooling for the children and in carrying out the pro

visions of article 2678, the county superintendent shall,

on the recommendation of the county school trustees, trans

fer children of scholastic age from one school district to

another, and the amount of funds to be transferred with

each child of scholastic age shall be the amount to which

the district from which the child is transferred is en

titled to receive.

Article 2695. (2759) Transfers.— Each year after the

scholastic census of the county is completed, the county

superintendent shall, if any district has fewer than twenty

pupils of scholastic age, either white or colored, have au

thority to consolidate said district as to said white or

colored schools with other adjoining districts, and to des

ignate the board of trustees which shall control the white

or colored school of such consolidated district * * *.

Article 2696. (2760) Application to transfer.— Any child

lawfully enrolled in any district or independent district,

may by order of the county superintendent, be transferred

to the enrollment of any other district or independent dis

trict in the same county upon a written application of the

parent or guardian or person having lawful control of

such child, filed with the county superintendent * * *.

37

Article 2697. (2761) Transfer to adjoining county.—

Any child specified in the preceding article, and its por

tion of the school fund, may be transferred to an adjoining

district in another county, in the manner provided in said

article. It must be shown to the county superintendent that

the school in the district in which such child resides, on

account o f distance or some uncontrollable and dangerous

obstacle, is inaccessible to such child.

Article 2698. Emergency transfers.— In case of con

ditions resulting from public calamity in any section of

the State such as serious floods, prolonged drouth, or ex

traordinary border disturbances, resulting after the schol

astic census has been taken, in such sudden change of the

scholastic population of any county as would work a hard

ship in the support of the public free schools of the said

county, the State apportionment of any child of school age

may, on approval of the State Board, be ordered by the

State Superintendent to be transferred to any other county

or Independent School District in any other county; pro

vided, that the facts warranting such transfer shall be

sent to the State Superintendent by the county or district

board of trustees of schools to which transfer is to be made

with a formal request for the said transfer before the

first of August of the year in which such unusual con

ditions occur * * *.

Article 2699. (2762) By agreement of trustees.— Except

as herein provided, no part of the school fund apportioned

to any district or county shall be transferred to any other

district or county; provided that districts lying in two or

38

more counties, and situated on the county line, may be

consolidated for the support of one or more schools in

such consolidated district; and, in such case, the school

funds shall be transferred to the county in which the prin

cipal school building for such consolidated district is lo

cated; and provided, further, that all the children resid

ing in a school district may be transferred to another dis

trict, or to an independent district, upon such terms as

may be agreed upon by the trustees of said districts

interested.