Sheff v. Oneill Plaintiffs Brief

Public Court Documents

August 1, 1995

77 pages

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sheff v. Oneill Plaintiffs Brief, 1995. 3409e8ec-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/eadcd777-ad39-4a38-8dfc-527c19056bd0/sheff-v-oneill-plaintiffs-brief. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

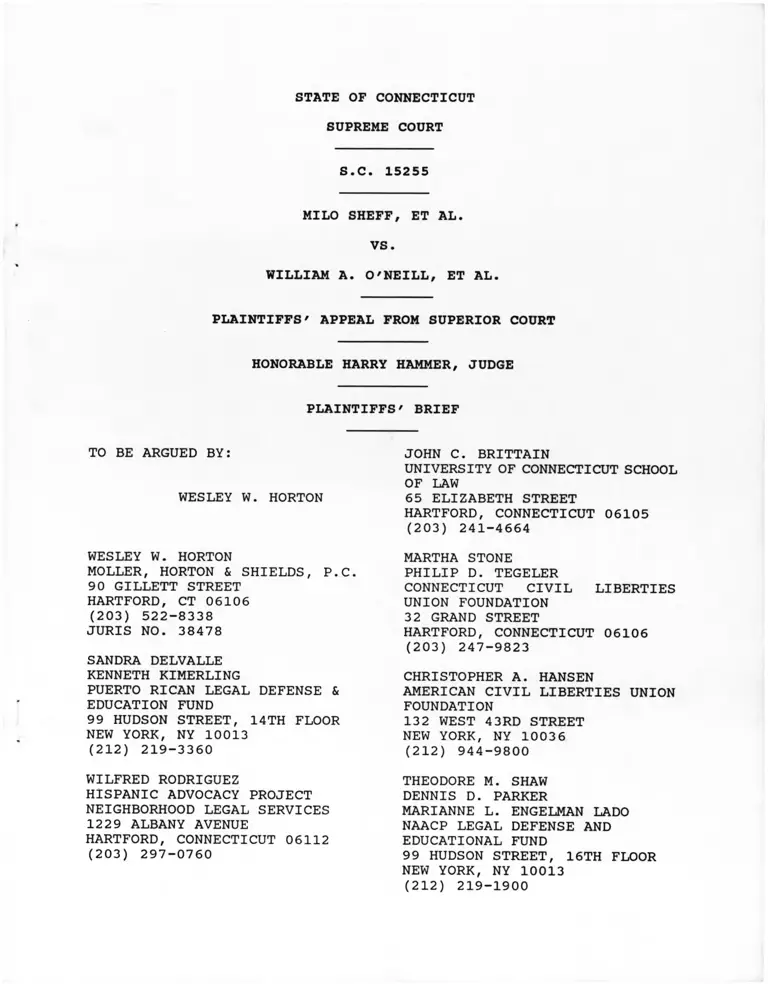

STATE OF CONNECTICUT

SUPREME COURT

S.C. 15255

MILO SHEFF, ET AL.

VS.

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, ET AL.

PLAINTIFFS' APPEAL FROM SUPERIOR COURT

HONORABLE HARRY HAMMER, JUDGE

PLAINTIFFS' BRIEF

TO BE ARGUED BY:

WESLEY W. HORTON

WESLEY W. HORTON

MOLLER, HORTON & SHIELDS, P.C.

90 GILLETT STREET

HARTFORD, CT 06106

(203) 522-8338

JURIS NO. 38478

SANDRA DELVALLE

KENNETH KIMERLING

PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATION FUND

99 HUDSON STREET, 14TH FLOOR

NEW YORK, NY 10013

(212) 219-3360

WILFRED RODRIGUEZ

HISPANIC ADVOCACY PROJECT

NEIGHBORHOOD LEGAL SERVICES

1229 ALBANY AVENUE

HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT 06112

(203) 297-0760

JOHN C. BRITTAIN

UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT SCHOOL

OF LAW

65 ELIZABETH STREET

HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT 06105

(203) 241-4664

MARTHA STONE

PHILIP D. TEGELER

CONNECTICUT CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION FOUNDATION

32 GRAND STREET

HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT 06106

(203) 247-9823

CHRISTOPHER A. HANSEN

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

FOUNDATION

132 WEST 43RD STREET

NEW YORK, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

THEODORE M. SHAW

DENNIS D. PARKER

MARIANNE L. ENGELMAN LADO

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND

99 HUDSON STREET, 16TH FLOOR

NEW YORK, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

Did the trial court err in failing to find state action? (at

II. Did defendants violate Article First, §§ 1 and 20 and

Article Eighth, § 1 of the Connecticut Constitution by failing to

provide public schoolchildren in the Hartford metropolitan area an

equal educational opportunity? (at 36-44)

III. Did defendants violate Article First, §§ l and 20 and

Article Eighth, § 1 of the Connecticut Constitution by providing

education in the Hartford metropolitan area that is segregated on the

basis of race and ethnicity? (at 44-55)

IV. Did defendants violate Article Eighth, § l of the

Connecticut Constitution by failing to provide Hartford schoolchildren

a minimally adequate education? (at 55-62)

V. Did defendants fail to remedy the racial, ethnic and

economic isolation and lack of educational resources despite their

long-standing knowledge of the harmful effects of these conditions’ (at 63-65)

l

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

NATURE OF PROCEEDINGS AND FACTS OF CASE

A. Racial and Ethnic Segregation .............

B. Unequal and Inadequate Education

1. Disparities in Outcomes ...............

2. Educational Resources ...............

(a.) Plants and Facilities .............

(b.) Equipment and Supplies, Textbooks and

Libraries ....................

(c.) Course Offerings and Curriculum

(d.) Teaching and Professional Staff

(e.) Bilingual Education Programs . . . .

(f.) Special Needs Programs .............

3. The Concentration of Poverty and the

Comparative Need for Resources .........

C. State Responsibility ..................

D . Remedy ......................

ARGUMENT .

I . THE TRIAL COURT ERRED AS A MATTER OF LAW IN FAILING TO

FIND STATE ACTION AND FAILING TO FIND THAT DEFENDANTS'

ACTIONS WERE CAUSALLY CONNECTED TO THE PROVISION OF

UNEQUAL EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES, THE CONDITIONS OF

SEGREGATION, AND THE PROVISION OF INADEQUATE EDUCATION

The Court Below Erred in Failing to Recognize the

Existence of State Action in Dismissing Plaintiffs'

Complaints of Unconstitutional Deprivation of a

Fundamental Right to Education

1. Public education is a public function that

necessarily involves state action

2 . Cologne v. Westfarms Associates yields the same

result ....................

The Court Below Failed to Recognize Actions That

Contributed to Existing Segregation in the Public Schools ........................

1. The court below improperly failed to address

proof of state involvement in segregation in

the public schools . . . . . . . .

2. Evidence of affirmative acts by the state to

increase segregation is not required to prove

state liability ..................

1

11

13

15

18

19

20

21

21

24

27

29

29

30

31

32

34

34

35

li

00 ̂

GO

II. DEFENDANTS HAVE VIOLATED ARTICLE FIRST, §§ 1 AND 20 AND

ARTICLE EIGHTH, § 1 OF THE CONNECTICUT CONSTITUTION BY

FAILING TO PROVIDE EQUAL EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES TO

PUBLIC SCHOOLCHILDREN IN THE HARTFORD METROPOLITAN AREA

A. Article First, §§ 1 and 20 and Article Eighth, § l

of the Connecticut Constitution Confer a Right to

Equal Educational Opportunity ...............

B. The Segregated, Economically Isolated and Unequal

Conditions in Hartford Metropolitan Area Public

Schools Violate Plaintiffs' Right to an Equal

Educational Opportunity ....................

III. RACIAL AND ETHNIC SEGREGATION OF THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS IN

THE HARTFORD METROPOLITAN AREA VIOLATE THE

SCHOOLCHILDREN'S RIGHT TO BE FREE FROM THE CONDITIONS OF

SEGREGATION AND DISCRIMINATION UNDER ARTICLE FIRST §§ 1

AND 20 AND ARTICLE EIGHTH, § 1 OF THE CONNECTICUT

CONSTITUTION .............

A.

B .

The Connecticut Constitution Prohibits Segregation

and Discrimination on the Basis of Race or Ethnicitv

in the Public Schools . . . . *

The plain language of the Connecticut

Constitution prohibits segregation .........

The history of the adoption of Article First, §

20 supports plaintiffs' contention that it is

the condition of segregation that is prohibited

by the Connecticut Constitution3 .

4 .

5 .

6 .

P^ior Connecticut appellate decisions

Sibling state precedent .........

Relevant federal precedent

Economic and sociological considerations

The Public Schools in the Hartford Metropolitan Area

Are Racially and Ethnically Segregated

IV. DEFENDANTS' FAILURE TO PROVIDE THE CHILDREN OF HARTFORD

WITH BASIC EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES VIOLATES PLAINTIFFS^

RIGHT TO AN ADEQUATE EDUCATION UNDER ARTICLE EIGHTH 5 i

OF THE CONNECTICUT CONSTITUTION . . ' * 1

A.

B.

^ Eighth, § 1 of the Connecticut Constitution

Establishes a Right to a Minimally Adequate

Education ......................

Defendants Have Failed to Provide the Children of

Hartford with an Adequate Education

37

41

45

45

46

47

50

51

52

53

55

56

56

58

ill

V. DEFENDANTS HAVE FAILED TO REMEDY THE RACIAL, ETHNIC AND

ECONOMIC ISOLATION AND LACK OF EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

DESPITE THEIR LONG-STANDING KNOWLEDGE OF THE HARMFUL

EFFECTS OF SUCH CONDITIONS ..........................

CONCLUSION ......................

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

AFSCME, Council 4, Local 681, AFL-CIO v. City of

West Haven, 234 Conn. 217 (1995) .............

Abbott v. Burke,

119 N.J. 287, 575 A.2d 359 (1990) ...........

Abingdon School District v. Schempp,

374 U.S. 203 (1963) ..........................

Ambach v. Norwick,

441 U.S. 68 (1979) ..........................

Barksdale v. Springfield School Committee,

237 F. Supp. 543 (D. Mass.), vacated, 348

F .2d 261 (1st Cir. 1965) ....................

Bishop v. Kelly,

206 Conn. 608, 539 A.2d 108 (1988)

Blocker v. Board of Education,

226 F. Supp. 208 (E.D.N.Y. 1964) ...............

Booker v. Board of Education,

45 N.J. 161, 212 A.2d 1 (1965) ...............

Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954) ...............

Builders Service Corp. v. Planning & Zoning

Commission, 208 Conn. 267, 545 A.2d 530 (1988)

Campaign for Fiscal Equity, Inc. v. State of New

York, No. 117 (June 15, 1995)

Carrington v. Rash,

380 U.S. 89 (1965) .................

Cologne v. Westfarms Associates,

192 Conn. 48, 469 A.2d 1201 (1984)

Daly v. DelPonte,

225 Conn. 499, 624 A.2d 876 (1993)

Danson v. Casey,

484 Pa. 415, 399 A.2d 360 (1979)

41, 57, 62

. . . 54

. . . 40

54

50

48

50

50

53

. . . . 43

59

36

32, 33, 34

40, 48, 51

. . 57, 58

v

Doe v. State,

216 Conn. 85, 579 A.2d 37 (1990).......................... 46

Dunn v. Blumstein,

405 U.S. 330 (1972) ........................................ 40

Englewood Cliffs v. Englewood,

257 N.J. Super. 413, 608 A.2d 914 (1992), tiff'd

132 N.J. 327, 625 A. 2d 483 (1993), cert, denied, 114 s

Ct. 547 (1993)..................................... '. . 50, 51

Fair Sch. Fin. Council of Oklahoma, Inc. v. State

746 P . 2d 1135 (Okla. 1 9 8 7 ) ..................'.............. 57

Foucha v. Louisiana,

504 U.S. 71 (1992)................................. 36

Griffin v. Illinois,

351 U.S. 12 (1956) ; ..................................... 36

Harper v. Hunt, CV-91-0117R, reprinted at Appendix

to the Opinion of the Justices,

624 So. 2d 107 (Ala. 1 9 9 3 ) ........................ 57

Harper v. Virginia Board of Education,

383 U.S. 663 (1966) ............................... 36

Hornbeck v. Somerset County Bd. of Educ

295 Md. 597, 458 A.2d 758 (1983).................. 57

Horton v. Meskill,

172 Conn. 615, 376 A.2d 359 (1977)...................... passim

Horton v. Meskill,

195 Conn. 24, 486 A.2d 1099 (1985)............... 37, 38, 40

Jenkins v. Township of Morris School District,

58 N.J. 483, 279 A.2d 619 (1971) . . . . . . . . 50

Lockwood v. Killian,

172 Conn. 496, 375 A.2d 998 (1977).................... 32

McDaniel v. Thomas,

248 Ga. 632, 285 S.E.2d 156 (1981) '/............. 57

Mizla v. Depalo,

183 Conn. 59, 438 A.2d 820 (1981) .................. 13 14

Moore v. Ganim,

233 Conn. 557, ___ A.2d ___ (1995)............... 38, 39 46

vi

Murphy v. Berlin Board of Education, 167 Conn.

368, 355 A.2d 265 (1974) ......................

NAACP v. Dearborn,

173 Mich. App. 602, 434 N.W.2d 444 (1988),

appeal denied, 433 Mich. 904,

447 N.W.2d 751 (1989) ........................

Norton v. American Bank and Trust Co., 5 Conn Sup

226 (1937) ...................................

Pauley v. Kelly,

162 W. Va. 672, 255 S.E.2d 859 (1979) .

Plessy v. Ferguson,

163 U.S. 537 (1896) ..........................

Reynolds v. Sims,

377 U.S. 533 (1964) ..........................

Rose v. Council for Better Education, Inc.,

790 S .W .2d 186 (Ky. 1989) ....................

San Antonio School Dist. v. Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 1 (1973) ......................

Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1 v. State,

90 Wash. 2d 476, 585 P.2d 71 (1978)

Shofstall v. Hollins,

110 Ariz. 88, 515 P.2d 590 (1973)

State ex. rel. Huntington v. Huntington School

Committee, 82 Conn. 563, 74 A. 882 (1909)

State National Bank v. Dick,

passim

52

12

57, 58, 59

. . . 51

. . . 36

57, 59

36, 37, 52

57, 58, 59

57, 58

31, 56

164 Conn. 523, 325 A.2d 235 (1973) . . . . 12

State v. Ayala,

222 Conn. 331, 610 A.2d 1162 (1992) . . . 48

State v. Geisler,

222 Conn. 672, 610 A.2d 1225 (1992) . . . 59

State v. Lamme,

216 Conn. 172, 579 A.2d 484 (1990) . . . . 47

State v. Oquendo,

223 Conn. 635, 613 A.2d 1300 (1992) . . .

VI1

40

State v. Rao,

171 Conn. 600, 370 A.2d 1310 (1976)

State v. Ross,

230 Conn. 183, 646 A.2d 1318 (1994)

Stolberg v. Caldwell,

175 Conn. 586, 402 A.2d 763 (1978) ...........

United States v. Yonkers Board of Education,

624 F. Supp. 1276 (S.D.N.Y. 1985), aff’d , 837

F .2d 1181 (2d Cir. 1987) ....................

West Hartford Education Association v. DeCourcy,

162 Conn. 566, 295 A.2d 526 (1972)

CONSTITUTIONAL ARTICLES AND STATUTES

Conn. Const. Article 1 § 1 .............

Conn. Const. Article 1 § 8

Conn. Const. Article 1 § 10

Conn. Const. Article 1 § 20

Conn. Const. Article VIII § l

C.G.S. § 10-4a ......................

C.G.S. §§ 10-184 ......................

C.G.S. §§ 10-220 ....................

C.G.S. §§ 10-240 ....................

C.G.S. §§ 10-241 ......................

C.G.S. §§ 10-264a, et seq...................

C.G.S. §§ 10-282, et s e q . .................

Haw. Const. Article I § 9 ........... , 4.

N.M. Const. Article XII § io

48, 53

. . . 46

41, 42, 43

. . . 32

. . passim

. . 2, 56

. . 2, 56

. . passim

. . passim

. . passim

31, 35

• . - 31

31, 34

• . . 31

• . . 27

• . . 35

• . . 52

• . 52

v m

MISCELLANEOUS

Conn. Agency Regs.

Proceedings of the

§§ 10-226e-l, et seq...............

1965 Constitutional Convention .

IX

NATURE OF PROCEEDINGS AND FACTS OF CASE

Hsirtfoird children attsnd schools that are ths most racially

ethnically, and economically isolated in the state. These schools

have the least educational resources and suffer from the worst

academic performance. The cumulative effects of these inequities

deprive Hartford s children of the preparation necessary to join the

mainstream of society. The central issue before this Court is whether

Milo Sheff and other school children have been deprived of their

constitutional rights to equal educational opportunity and minimally

adequate education.

Plaintiffs, black, Latino and white public schoolchildren in

Hartford and its neighboring suburbs, brought this action for

declaratory and injunctive relief against defendant State Board of

Education and other education officials.1 * III

1The Complaint is in four counts:

first, that because Hartford metropolitan area schools are

segregated on the basis of race, ethnic background, and

socioeconomic status, and because the Hartford schools are

educationally deficient when compared to the suburban

schools, defendants have failed to provide plaintiffs an

equal opportunity to a free public education as required by

Article First, §§ 1 and 20 and Article Eighth, § 1 of the

Connecticut Constitution, (Issue II on appeal);

second, that the sharp segregation on the basis of race and

ethnic background in Hartford metropolitan area public

schools, by itself, violates Article First, §§ l and 20 and

Article Eighth, § 1 of the Connecticut.Constitution ?issSeIII on appeal) ; '

third, that the Hartford

deficient and fail to

schoolchildren with a

measured by the state's

Article First, §§ l and

Issue IV); and

public schools are educationally

provide a majority of Hartford

minimally adequate education

own standards, and this violates

20 and Article Eighth, § i, (now

1

In 1990 the trial court denied defendants' Motion to Strike,

ruling that plaintiffs had stated a claim upon which relief could be

granted, and specifically that the complaint satisfied the

requirements of state action, justiciability, and causation. (R at

82-92). In 1992, the trial court denied defendants' Motion for

Summary Judgment, again concluding, among other things, that the

plaintiffs had shown state action and justiciability. (R. at 97-107)

After a six week trial ending in February 1993, and closing

arguments on December 19, 1993 and November 30, 1994, the trial court

issued an opinion concluding that plaintiffs' constitutional claims

need not be addressed because plaintiffs had "failed to prove that

'state action is a direct and sufficient cause of the conditions'

which are the subject matter of the plaintiffs' complaint." (R. at

179) .

At trial, plaintiffs' constitutional attack focussed on the

layers of inequity in the schools: the harms of racial and ethnic

isolation and the concentration of poor children, the gross

disparities in the quality of education provided by Hartford and its

neighboring school districts, and the inadequacies of the Hartford

public schools. Many of the facts upon which these claims were based

were agreed to by the parties.

fourth that the defendants' failure to provide plaintiffs

and other Hartford schoolchildren the equal educational

opportunities to which they are entitled under Con£ect?c5t

o b l ' i J * r 9C: f S - 5 10"4a' and “hich defendants are obliged to provide, violates the Due Process Clancy Article First, §§ 8 and 10. Clause,

The trial court addressed none of these claims. (R. at 179)

2

A - Racial— and— Ethnic Segregation. it is undisputed that the

Hartford public schools are racially and ethnically segregated.2

African Americans, Puerto Ricans and other Latinos alone constitute

more than 90% (or 23,283 of the 25,716 students) in the Hartford

public schools. (Stip. 26, 27).3 In contrast, in 1991-92 only seven

of the 21 nearby school districts had more than 15% African American

and Latino student populations. (Stip. 38). Thirteen of the school

districts were less than seven percent African American and Latino.

(Stip. 35 (1987-88 data)). The extent of Latino isolation is even

When this lawsuit began in 1989, the available 1987-88 ficmres

for the school population and the percent minority for the 22

districts surrounding and including Hartford were:

Total School Pop. % Minority

Hartford 25,058 90.5Bloomfield 2,555 69.0Avon 2,068 3.8Canton 1,189 3.2East Granby 666 2.3East Hartford 5,905 20.6East Windsor 1,267 8.5Ellington 1,855 2.3Farmington 2,608 7.7Glastonbury 4,463 5.4Granby 1,528 3.5Manchester 7,084 11.1Newington 3,801 6.4Rocky Hill 1,807 5.9Simsbury 4,039 6.5South Windsor 3,648 9 3Suffield 1,772 4.0Vernon 4,457 6.4West Hartford 7,424 15 7Wethersfield 2,997Windsor 4,235

J • J

30.8Windsor Locks 1,642 4.0

(Stip. 35).

3The overall minority enrollment

(Stip. 26). in the Hartford schools is 92%.

3

more dramatic. In 1991 sixteen suburbs had less than 3% Latino

enrollment. (Stip. 32).4

Plaintiffs also demonstrated that the racial segregation of the

Hartford schools continues to increase, and shows no signs of

reversing, (Finding 42; Stip. 58, 60, 61), while the vast majority of

suburban towns remain segregated. (Pis' Ex. 126, 130).5

Significantly, defendants have admitted that "segregation is

educationally, morally and legally wrong." (Defs' Ex. 12 5 at 1)

Defendants have repeatedly acknowledged that racial and ethnic

isolation is detrimental to students, particularly to minority

students, and that integration is beneficial to all children and

continues to have positive effects long after the children have left

the school setting. (Stip. 150, 152; Pis' Ex. 50, 60, 494 at 11-12

(Tirozzi Dep.)).6 The parties agree that "a multicultural

environment is an irreplaceable component of quality education."

(Defs' Ex. 2.29 at 1).

4The extent of segregation can perhaps be understood most readilv

by examining an average Hartford class. In an average class of 23 4

students, 21.6 will be members of minority groups. (Stip. 28)

The effect of this student segregation is aqqravated hv

segregation m the professional and teaching staff. As of I99i-92Y

only two districts, Hartford and Bloomfield, employed more than i

3fif1CaM AJneii;L̂ ns and Latinos on their professional staffs. (Stip°

14 22)M St °f the dlstricts hover in the range of 2%. (Defs' Ex. 14. l-

f V

Both defendants Commissioner Vincent Ferrand-inn anH r ...

Commissioner Gerald Tirozzi acknowledged the tarns of rataa?

segregation (Pis' Ex. 493 at 35, 138-39 (Ferrandino tan.) pi=?

K94v,a^ 11 12 T̂irozzi Dep.)), and Commissioner Tirozzi admitted

effects anf the St1ate B°ard °f Educaci°n had been aware of the hamfta

4

Plaintiffs presented undisputed testimony that racial and ethnic

segregation has long-lasting adverse consequences. The state itself

commissioned a major review which found that integrated education had

a positive impact on achievement, school dropout rates, and college

attendance rates, and also had positive long-term social and economic

consequences. (Defs' Ex. 12.25).7 And in its major 1988 report on

the need for school integration, the State Department of Education

strongly emphasized the importance of preparing students for "living

and working in a multicultural society." (Defs' Ex. 12.5 at 7)

These conclusions were borne out by the testimony of educators

from both urban and suburban schools who described the development of

racial stereotypes due to segregated experiences.8 They were

substantiated further by detailed testimony on the long-term effects

7Janet Ward Schofield, "Review of Research on School

“SlceSI? 8°ni9S88T P a in Secondary School Students"8, 1988) In addition to the broad educational benefits of

integration tor all racial groups, Professor Schofield also found that

the impact of integration on achievement for African American students

was consistently positive. For Latinos and,whites, the results wSrl

positive or neutral. Schofield's review was cited as support for the

reconunendations of the 1989 State Department of Education report

Ex 60K Inte9rated Education: Options for Connect!™?%

8Several Hartford teachers described thp rnnt--i mi-i

isolation that segregation inflicts on children t o S a v 5 ^ °f

Johnson II at 15-17; Dudley at 129-133° Hernandez at 42? 64)'

5

of segregated school experiences by Dr. JoMills Braddock,9 Dr.

William Trent,10 and Dr. Robert Crain.11

Dr. Braddock cited the wealth of evidence showing that early

segregation experiences in school leads to segregation in later life

because of a tendency of individuals from different backgrounds to

avoid interactions with one another unless [there is] prior contact."

(Braddock at 18, 20-21).12 As a result, minority students are often

excluded from the employment networks that are essential for success

*Dr. Braddock, an expert in educational and occupational equity

has been performing and supervising educational research for fifteen

years; He has conducted longitudinal studies to examine the

relationship between segregated educational experiences and

educational and occupational outcomes. (Braddock at 8).

. D r - Trent, an expert in the sociology of education, used two

national longitudinal databases to analyze the relationships amonq

racial and economic isolation, socioeconomic status and various life

outcomes. (Trent at 61, 77-78).

11Dr. Crain an expert in research methods, school desegregation

“ rain rat°331Ci!' hiS StUdy °f j ect 3ConcerS(Crain I at 33, 53, 60-62). Defendants' experts explicitlv aareeri

that Dr Crain's work is of a high order of methodological clarity and

adheres to high methodological standards. (Armor I It 99; Rossell ?l3 L o 2.) .

12A s early as 1967, the United States Civil Riqhts Commission

described the self-perpetuating nature of segregation^ Toting t h S racial isolation m the schools 9 cnac

fosters attitudes and behavior that perpetuate isolation in

other important areas of American life. [Black] adults who

attend racially isolated schools are more “ kily to hate

developed attitudes that alienate them from whites. White

adults with similarly isolated backgrounds tend to resist

desegregation in many areas -- housing, jobs and schools.

(Pis' Ex 11 at 110). Statistical analysis confirms that seqreaatinn

perpetuates itself regardless of a student's racial or ethnic qrouD

or individual socioeconomic status. (Trent at 61 77.00. D1 ?

thitCsrhDDi EE' FF) ‘ .Indeed' defendants' witness David Armor conceded that school segregation has a generational effect. (Armor I at 146)

6

in later employment and other beneficial life outcomes. (Braddcck at

22, 31) .13 Desegregation experiences allow minorities to break down

these systemic barriers to equal opportunity and provide access to

important networks. (Braddock at 22).

The results of a study of Project Concern, a small one-way

interdistrict busing program established in Hartford in 1966, were

entirely consistent with the findings cited by the other witnesses.

The study found that "[African American] students from segregated

schools were going into those kinds of jobs traditionally held by

blacks." (Crain I at 33; see also Pis' Ex. 387 at 26).14 other harmful

long-term results of school segregation include increased likelihood

of dropping out from high school or college and early female

childbearing, and an increased likelihood that African American

students will experience difficulties with their social environment

in college. (Crain I at 53; Pis' Ex. 387 at 26-29) .15

B - Unequal and Inadequate Education. Plaintiffs presented lay and

expert testimony and reams of documentary evidence to prove what any

layman visiting the public schools in Hartford and its surrounding

13For minority students, the perpetuation of early segregation

experiences negatively affects the likelihood of finding well paid

employment in the private sector. (Crain I at 33 ° 147; Pis' Ex. 387 at 13, 34). at 33' 58~60'’ A™ r I at

"Segregation also adversely affects the subsequent occuDaHnn^i

aspirations of African American students and their S)n perc2p?lois Sf their chances for promotion. frra-in t ^ cr\ ons of(Cram I at 60-62; Pis' Ex. 387 at 24-

15 ,

Significantly, the long-term effects of school segreaation

independent of the individual socioeconomic status of f ^ c h n S r e n

(Cram I at 44; see also Armor I at 21-22) . iidren.

7

suburbs can observe -- i.e. the gross disparities in educational

opportunities provided to students in Hartford as compared to the

suburbs and the inadequacies of schooling in Hartford. There was no

dispute over many of the underlying facts.

1 * Disparities in Outcomes. The Connecticut Mastery Test is

a criterion-referenced test that is the state's own measure of the

<3ualiby of education. An important goal of the test, as explicitly

stated by defendant Board of Education, is to improve "assessment of

suitable equal— educational_opportunities . " (Stip. 158 (emphasis

added) ) . It is undisputed that under any of the benchmarks for

achievement, including the state goals,16 the mastery level and the

state remedial standard, (Stip. 170), Hartford performance levels are

uniformly and substantially below that of the average performance

levels of students in all other districts. (Stip. 166, 168, 169, 174-

197) ,17

H .. 16/?t^tewide 9°als represent a particular level of achievement

defined by mastery of a particular number of objectives teJtTdiA

math, reading and writing. (Stip. 171, 172)

■ a couft below erred by dismissing all evidence of disparities

achievement, erroneously finding that mastery test data could not

and^hatto draw conclusions about the quality of education in Hartford

and that the mastery tests were "not designed to be used for purposes

of comparison." (Finding 104, 107). This conclusion is c o E S l v

? L ? dHSt-W1^h Mhe court's finding that the districts can use mastery

improve their programs" and to "correct deficiencies"

? ^ L that the tests provide the basis for the state's disbursement of funds among districts. (Finding 103). uursement of

8

Enormous percentages of Hartford students have failed to meet the

state goals. Hartford students uniformly mastered fewer math

objectives than did the students in the surrounding districts, a

pattern repeated for the reading and writing portions of the test

Hartford ranked at the bottom of all twenty-one districts for all

skills tested, with only one minor exception.19 (Stip. 174-197)

The tragic disparity in achievement becomes more apparent when

examining the remedial scores. Large numbers of Hartford students are

not able to meet even these minimal standards, which are used to

indicate the need for remedial instruction. For example, in

mathematics, 41% of 4th graders, 42% of 6th graders, and 41% of 8th

graders in Hartford failed to perform up to even the state's remedial

standards xn 1991-92. (Stip. 172). In reading, the results are even

more disturbing: a majority of Hartford public schoolchildren did not

meet even the remedial standards -- 64% in 4th grade, 62% in 6th

grade, and 55% in 8th grade. (Stip. 172)

It is also undisputed that the disparities in achievement are

reflected xn other indicators of educational performance. in 1991,

Hartford students took the SAT at a lower rate than students anywhere

else xn the state -- only 56.7% of Hartford students sat for the test,

compared to 71.4% statewide -- and yet this more selective slice of

Hartford students still scored lowest on the SAT when compared to

meet s t a L ^ o S ^ o r H t h e ^ e l x t A grade ^ m a ^ ^ e e t ^ f o r the1^

grade readxng test, and 97% for the writing test'. °stip. 172)

19Hartford tied for the

eighth grade writing test. lowest score with Windsor Locks on

(Stxp. 185; Pis' Ex. 163 at 213). the

9

students taking the test in the surrounding suburbs. (Stip. 198,

199) . In verbal skills, seventy-six points separate the Hartford

average from the next lowest scoring district. (Stip. 2 0 0).20 In

math, fifty-seven points separate the average score of Hartford

graduates from the average score of students in the next lowest

scoring district. Id . Not surprisingly, in 1988 fewer than 30% of

Hartford students attended four year colleges in the October following

graduation, while over 52% of students did statewide. (Stip. 201) 21

Defendants attempted to show that the disparities in test scores

were fully attributable to differences in the individual socioeconomic

status of the children, (Armor I at 30-32, 94-95), advancing a theory

that poor children in Hartford are doing as well as can be expected

given their circumstances, and that schools cannot make a difference.

20Students can score a maximum of200) . 800 points on the SAT. (Stip.

Plaintiffs also demonstrated disparities in scores on the

Metropolitan Achievement Test (MAT) and the Spanish Assessment of

Basic Education (SABE) and in high school drop out rates MAT test

scores show that Hartford students are, in the words of one witness

"falling farther and farther behind grade level" as they progress f?om

second to tenth grade. (Nearine at 136-37; Defs' Ex 13 9 m s "

Ex. 163 at 124-35; Natriello I at 161). By the tenth grade the

average Hartford student performs 2.0 grades below grade level on the

math section of the test. (Defs- Ex. 13.9; Pis' Ex 163 In

language, average Hartford tenth grade students perform 1 7 grades

below, (Defs' Ex. 13.9; Pis' Ex. 163 at 127), and t e n d i n g the

w i ' ai;.H?63fI f 12sTSent Perf0rmS 2'9 Srades below. (Defs' Ex. 913 9?

The SABE is administered to all Hartford student-e? -in

through eight in the Spanish/English bilingual program SABE results

also show extremely poor performance. By the eighth grade stude^c

a f S ? ) thandte3Sti l "° be!ow grade levels (Pis' Ex ^ 6 3

13ninV7 d 3-1 grades below m reading. (Pis' Ex. 163 at 13 8)

, Perhaps most significantly, approximately one-third of the

students m the Hartford high schools drop out (Defs' Ex 12 20 Pis' Ex. 163 at 142-45). V V 5 *X - 12-20;

10

(Armor I at 29-31, 94-95) .22 These assertions were contradicted both

by plaintiffs' evidence, (Orfield I at 138; Slavin at 24-27), and by

defendants themselves. (Pis' Ex. 514 (Ferrandino statement); Pis' Ex.

493 at 50-51 (Ferrandino Dep.) ; Williams at 31, 81-83).23 The

parties also agree that "at-risk" children have the capacity to learn,

(Stip. 142), and that poor and minority children have the potential

to become well educated. (Stip. 153)

2 - Educational— Resources. Books and supplies, curriculum,

facilities, staff and programs are the building blocks of education.

The trial record shows gross disparities and deficiencies in these

crucial areas with no improvement over time. (Natriello I at 131-33-

Natriello II at 60, 62-63) ,24

In fact, from 1980 to 1992, Hartford spent approximately $2,000

less per pupil than the state average on plant operations and

equipment, pupil and instructional services, textbooks and

co^rt accepted this argument, at least in part.

116, 142) . This finding is both clearly erroneous and based

legal error. See infra at 59-62.

(Finding

on clear

. . D r - Robert Crain, an expert in research methods

testified that Dr Armor's data was inadequate to support his

;°??);Uf10nE an,l identified several significant methodological

deficiencies. (Cram II at 73). Ironically, Dr. Armor's conclusions

about the impact of student socioeconomic status (SES) inadvertentlv

measured not only the impact of individual SES but also the

concentration of poverty in the schools.. Dr. Armor attributed

in *chievement to individual SES despite the fact that his method did not distinguish between measures of individual SES and of

the concentration of poor students in a community (Armor I a M 4 9 ̂

154-55, 159-60; Crain II at 60, 67). 7- ( 1 at 142'

In finding that resources were equal in Hartford to surrounri-ino

communities (Finding 143), the trial court simply ignored this ShoJe

body of evidence. The court's conclusion is thus clearly erroneoSj

11

instructional supplies, and library books and periodicals. (Stip.

106) . Moreover, plaintiffs presented unrebutted evidence that, in

category related to important programmatic resources, i.e.

textbooks and instructional supplies, library books and periodicals,

equipment, and plant operation, Hartford's resources were woefully

short compared to the suburbs, and, indeed, were deficient. (Pis' Ex

163 at 79; Natriello II at 12).

A key piece of plaintiffs' evidence at trial was a report by Dr.

Gary Natriello, professor at Columbia University's Teachers College

documenting resource inequalities and inadequacies, which relied

primarily on reports by defendants and official reports of other

governmental bodies. (Pis' Ex. 163 at 13-14; Natriello I at 51-53)

Significantly, only one chart in this entire report was disputed by

defendants. (Forman at 40-42).25 * S

25Documentary evidence not contradicted by the opposition has on

occasion been treated as undisputed by this court. See e g State

National Bank v. D ick, 164 Conn. 523, 525-26, 325 A.2d 235 (1973) Judae

(later Chief Justice) O'Sullivan, in deciding a Workmen's Compensation

appeal, provided perhaps the best explained rationale for such a S e -

If the fact is uncontradicted, especially when it is of

— ch— g nature— that— one— would reasonably expect rtotip

contradictory--testimony to be offered whPre if -î

^Yaii^le, if there is nothing in the record to indicate

that the witness to the fact was not to be credited if

upon the face of the evidence it is credible, and if' the

commissioner has not indicated that he did not credit the

evidence, these with other considerations, furnish a

SKf5iCie^ 9yide to assist one's reaching a conclusion whether the fact was or was not in dispute.

Norton v. American Bank and Trust C o ., 5 Conn. Sup. 226, 229 (1937) (citation

omitted)(emphasis added). M citation

^ ??CUmen5arY„ evidence in this case, including plaintiffs'exhibit 163, meets that test. Dr. Natriello's report compiles and

relies upon public information readily available to the defendantSd

12

■(a •'-- Plants— and Facilities. The contrast between the glass-

strewn asphalt playground at Hartford's Clark School and the 17-acre

outdoor classroom and $40,000 playscape at Glastonbury's Hopewell

School, (Dudley at 124), epitomizes the gross disparity in facilities

between Hartford and its surrounding suburbs.26

In fact, defendants conceded that there are serious deficiencies

in buildings throughout Hartford's public school system. (Pis' Ex

153 at 5-11; Defs' Ex. 2.24, 2.27; Calvert at 83-85). At the time of

trial, eight of Hartford's 31 school buildings required "significant

attention." (Stip. 101).

Hartford's schools are also severely overcrowded. Hartford

elementary schools operate at 133% of preferred capacity, the middle

schools at 106% and the high schools at 107%. (Pis' Ex. 163 at 75)

There are approximately 115 portable classroom units in use in

Hartford. (Senteio at 16; Pis' Ex. 163 at 75),27 * 63

much of which was in fact produced by defendants. The State

Department of Education would surely be in a position to contradict

^ lf Xtu WSre„ Untru e • There was nothing in the record to indicate

that such evidence was not to be credited or that Judge Hammer ever

doubted it. Such documentary evidence should be considered uncontested in deciding this appeal. considered

tl0n' ■ 5hS Plafntiffs proposed numerous findings of fact reiated to disparities and inadequacies that the trial court did not

include in its finding. Some of these proposed findings are based on

evidence from the defendants' own files or were conceded to be true

^riala SUCh pJ°Posed findings are clearly uncontested and should be considered in deciding the appeal. Mizla v. D epalo , 183 Conn 59 6263, 438 A.2d 820 (1981). • y conn. 59, 62-

6See also Griffin at 96-97; Neuman-Johnson at 159-62.

of classrooms have a "terrible impact" upon the deliverveducation program in part because of the "enormous expenditure

at 19T in JUSt p h y s i c a l l y moving." (Negron at 71; see Montanez

13

Throughout the Hartford system, rooms are being used as general-

purpose classrooms that were not intended for such use. (Senteio at

17; Neuman-Johnson I at 160). Hallways have been converted for use

by language, speech, and hearing specialists. Id. One teacher

testified that she spent her first half-year teaching a third grade

class in a hallway due to a shortage of classroom space. (Neuman-

Johnson I at 160).

Many Hartford schools do not have cafeterias, art, or music

classrooms. (Senteio at 17-18; Anderson at 120-21). Some schools

have no outside playground space, (Montanez at 17; Negron I at 70),

or playground equipment. (Cloud at 81, 85, 91) ,28 m several

schools gymnasiums are used for other purposes, or gym classes are

held in classrooms, parking lots outside the building, or, in one

school, in a basement room referred to as the "dungeon." (Cloud at

83; Montanez at 16-17). At Hartford High, an allied health class

meets in a storage room. (Griffin at 88).

Although many of the district's schools are in need of serious

repair, (Senteio at 16; Cloud at 81; Pis' Ex. 153 at 5-11), Hartford

is frequently forced for budgetary reasons to defer major maintenance

28r

qnh_ ; The nearly all concrete playground space at Hartford's Milner

anS ?! £rammed ?lth portable classrooms and teachers' aStomobilSs

a 1 *s any playground equipment. (Cloud at 81-85) . Even worse'

four dumpsters filled with lunchroom garbage attract rats anH i-v.!

smell during warm weather prevents use of part of the playground. Id

14

such as roof repair, until the problem becomes critical. (Senteio at

14-15; LaFontaine at 134).29

---Equipment and Supplies,_Textbooks and Librari pk Gross

disparities in equipment and materials affect the entire curriculum -

- from basic science to music. For example, a fifth grade class in

Glastonbury enjoys an embarrassment of riches in science equipment,

all supplied by a "central science curriculum center," while at least

one inner-city Hartford school has virtually no science equipment.

(Dudley at 122; see also Griffin at 95-96). Similarly, there is a

"glaring" disparity in music equipment: at trial, for example, one

teacher compared the full orchestra at West Hartford's Duffy School

with the total of 12-15 aging instruments at Hartford's McDonough.

(Neuman-Johnson II at 7-8) .30

From 1988-91 Hartford spent an average of $78 per pupil on

textbooks and instructional supplies as compared to the state-wide

29 _

n a . , S°™e °f substandard physical conditions include peeling

paint, leaky roofs, antiquated bathrooms without doors on the stalls9

broken sinks, nasty water, broken windows, and faulty electrical

systems. (Cloud at 81, 103; Montanez at 18). One principal tesMfioa

that the ceilings at the McDonough School have collapsed several

at least one case nearly injuring students. (Carso at 112)

S n ! 11119 V 1 one, teacher' s classroom at the Barnard-Brown Schooi fell down on her class. (Hernandez at 44).

30 In one Glastonbury class, fifth graders enjoy two freouentlv

used computers with the latest in educational software and phone links

° " T T , COmputer networks, while in a class at Hartford's Clark School, there is only one computer with a broken kevhnsrH ana

teacher who has not been adequately trained b k s at

122-123). In fact, defendants' data showed that Hartford spent

$25 per pupil from 1988-91 on acquisitions of equipment such ^

S97^qnpnf and microscopes; representing one-fourth of the average of

oPfnt the twenty-one surrounding districts (Pis' Fy i fi

183-94) . Some districts, such as Glastonbury and West Hartford “ m excess of $100. (Pis' Ex. 163 at 164). Y Hartford, spent

15

average of $148 during the same time period. The twenty-one

surrounding districts spent an average of $159 per pupil, over twice

as much as spent by Hartford. (Pis' Ex. 163 at 164),31

The Hartford schools suffer from serious inadequacies in

educational equipment, including an insufficient number of chairs in

the libraries (Carso at 103-04), a lack of appropriate high school

laboratories, (Davis at 79; Griffin at 89-90), too few computers

(Wilson at 15-16),32 and inadequate art supplies, which are key for

the kindergarten curriculum. (Cloud at 90). The high schools have

insufficient, old, and non-functioning equipment in the life

management, technology education, science, and business departments.

(Griffin at 86-87, 89; Davis at 77).

Lack of resources forced Hartford to reduce textbook

appropriations by 26-27% over the last few years. (Haig at 62)

In addition, while Hartford spent an average of $5 per pupil from

1988-91 on library books, periodicals and newspapers, the twenty-one

surrounding districts spent on average substantially more than three

times as much -- $18 for the three years. (Pis' Ex 163 at 68

Testimony from teachers bore out these dismal ffgures. While the

iibrary at the Duffy School in West Hartford is "rich" in resources

with new titles coming, every, every week," Hartford's McDonouqh

library suffers from lack of space, lack of books, and broken

equipment. (Neuman-Johnson II at 6-7; Griffin at 90, 97; Wilson Jt

There are substantial inadequacies in the availability of

iCo PU whrSi' â Well. aS teacher training in computers. (Wilson at l? 16) . While the school district's goal is to.have eight compSte?s per

classroom the average remains less than one. (Wilson at 15- Haiq at

60). In Hartford's elementary schools (K-6), the ratio of'students

to computer ranges from 27.8 students per computer at the Clark school

to more than 90 students per computer at King (Pis' Ex 163

One Hartford teacher testified that she had received one computer for

6 time thls past year at Betances School but had not received

any disks or software. Ultimately, the unit could n S f be used (Anderson at 120; Griffin at 98). ° used-

16

Inadequacies exist in very basic supplies such as paper and in

the most fundamental educational component, textbooks. (Hernandez at

44; Carso at 101; Noel, at 28; Negron at 73; Marichal at 20-21). in

order to fill the gap, many teachers spend hundreds of dollars of

their own money buying basic instructional supplies and books, (Carso

at 101-02; Anderson at 119, 122; Pitocco at 74; Neuman-Johnson at 8;

Montanez at 20) ,33 and reuse books that were made to be used in one

year and then discarded. (Anderson at 117). In one school there are

entire areas of the curriculum for which there are no textbooks

(Natriello I at 199-200). Many students have to share textbooks,

(Montanez at 19-20) , and some bilingual students use textbooks that

are approximately twenty years old. (Montanez at 19-20)

Hartford students attend schools that are not able to offer

adequate library facilities. (Pis' Ex. 186 at Table 11; Pis' Ex. 163

collections that meet the minimum recommended standard. (Pis' Ex 186

at 69) .34 Only three of Hartford's thirty-one schools have library

In addition to having too few books,

34

and cai

11 ) -

17

the library collections are extremely old. (Cloud at 84,- Pis' Ex. 163

at 69) ,36

.(c. )---Course Offerings and Curriculum. Defendants' own data

showed that Hartford offers fewer hours of instruction than twelve

other districts in the region at the elementary level, fewer hours

than twenty other districts in the region at the middle school level

and the fewest number of hours of any of the districts in the region

at the high school level. (Defs' Ex. 14.1-14.22; Pis' Ex. 163 at 175-

77). Cumulatively, Hartford students are receiving 5-6% less

instruction time in the years before high school than are their

suburban counterparts. (Pis' Ex. 163 at 67).

The curricular inadequacies in Hartford exist in a broad range

of courses and subject areas -- from science to art to foreign

languages.37 At one school, kindergarten children have no art,

music, gym, or library. (Cloud at 104). At another school, some

students have gym class for only twenty minutes per month, (Hernandez

checked out two or three books, the shelves would be emotv

at 21-21; Davis at 75-76). * (Montanez

3 6 rTwenty-three of Hartford's thirty-one schools had librarv

collections in which at least half of the books were over fifteen

years old. (Pis' Ex. 163 at 69; Pis' Ex. 395 at 2).

Moreover, Hartford students are also deprived of access to an

adequate supply of periodicals, computer materials, microform and

microfiche, and non-print media. (Pis' Ex. 163 at 69). Libraries

imP°rtant: media equipment, or the equipment they have is

(Wllson at 11) . Classroom libraries are similarly deficient (Cloud at 90; Hernandez at 44). y aericient .

3 7 tF°r example, Weaver High School is not able to offer laboratorv

in b^ol°^' chemistry, or physics. (Davis at 79) Hartford

High has no advanced placement courses in chemistry, biology or human

physiology (Griffin at 89). Hartford also has substandard foreign

language laboratory facilities. (Natriello II at 19) ^

18

at 45), and students have art class only a portion of the year -- and,

even then, only every other week. (Hernandez at 45).

---Teaching and Professional Staff. Hartford has a lower

proportion of teachers with masters' degrees than the twenty-one

surrounding districts, and also ranks at the bottom when comparing the

numbers of teachers trained as mentors, assessors, and cooperating

teachers. (Defs' Ex. 14.1-14.22; Pis' Ex. 163 at 166-67). The number

first-year teachers is twice the statewide average, (Natriello I

at 106), leaving the most inexperienced group of teachers to confront

"the most challenging groups of students in the Connecticut public

school system." (Natriello I at 107).

Hartford also came up short in comparisons of expenditures for

purchased personnel services that are not part of payroll, such as

teaching assistants, medical doctors, curriculum consultants,

therapists and psychologists. (Natriello II at 18),38

Moreover, because so substantial a portion of its funds must be

devoted to staff for special needs students, there is a chronic

shortage of staff to teach the traditional parts of the educational

program. (Carso at 97; Shea at 131). Thus, Hartford's schools employ

on average more special education teachers and fewer general

elementary teachers and content-specialist teachers than do other

districts. (Stip. 85).39

nl Hlartfl°rd. spient $39 Per pupil in this area for the 1988-91

school years, m contrast to an average of $101 for the twentv on? surrounding suburbs. (Pis' Ex. 163 at 164). twenty-one

In additi°n/ Hartford schools lack an adequate number of

nurses, psychologists, speech therapists, guidance counselors and

social workers to properly treat the many children in the district who

19

— Bilingual Education Programs. Hartford's bilingual program

is plagued by inadequate staffing,40 texts and instructional

materials, training, and remedial programs. (Marichal at 20-21)

Plaintiffs showed that Hartford has insufficient money to

purchase up-to-date and appropriate texts and other instructional

materials, forcing some Hartford bilingual students to use Spanish

basal readers developed in the 1950s. (Marichal at 20-21) 41

Moreover, Hartford has insufficient funds for bilingual teacher

training. (Marichal at 20) . Many principals have no training in

have social problems -- from homelessness to lack of family resources

for food and clothing to emotional problems that interfere with

education. (Dickens at 153-55; Negron I at 67, 71, 81; Noel at 31-32

Cloud at 91-3; LaFontaine I at 129; Griffin at 86; Hernandefa? 46?'

Moreover, the deficiencies of the Hartford school system have

been exacerbated by reduced state funding. (Kennelly at 63 Pis' Pv

423K The impact of recent cuts has been parlrcularly 'severe L

Hartford s reading programs. Hartford lost all 31 readina

consultants, who had been responsible for testing students and

determining their reading level and appropriate reading instruction??

(Sentei° « Haig at 60; Carso at 105; M?nt“ e?at

e loss of paraprofessionals has interfered with teachers' abil-ii-v

to individualize instruction. (shea at 124-lJ?) cuts S

administrative staff have also created difficulties in coordination

and supervision, (Griffin at 89; Haig at 60; Shea at 121 ?2 8? ?^

cutbacks in secretarial reductions have pulled teachers awav ' from

^Sh??1?? 127)^^ ±t: m°re difficult for Parents to contact the school.

“Existing staff shortages in bilingual education have been made

orse by layoffs, including a reduction of six English as a Second

a t ^ f o r S

r e m e d ia t i°n

The bilingual educational program being offered in Hartford'c

"S0marked a significant lack of rlsour??? (MaS L i a

35). A 1987 State task force found that while $947 in state funding

P J ill1 uas to implement state-mandated bilingual programs

the state contribution was approximately $190 per puoil -? nniv m

B -̂rcent of the recommended level. (Marichal at 22; PI?' Ex. If)1.7 °

20

bilingual education, making it difficult to supervise adequately the

bilingual teachers. (Marichal at 33).

Although between 30 and 35% of Hartford's bilingual students are

currently testing at remedial levels, (Marichal at 29), there is

currently no native-language remedial program for elementary school

students, (Marichal at 30), and an insufficient program at the high

school level. (Marichal at 30; Pis' Ex. 439 at 5).

If̂ -1— Special Needs Programs. Plaintiffs also demonstrated that

although effective educational programs have proven successful in

educating special needs students, (Slavin at 14, 22; Senteio at 14;

Haig at 63-64; Negron 81; Wilson at 16-19), and are a critical

component of an adequate education, (Pis' Ex. 474), they are not

currently being provided to the many Hartford students who would

benefit from them. (Slavin at 34). Hartford's few special needs

programs affect only a very small proportion of the total numbers

within the system and have not been expanded despite their success

(Wilson at 18-19). For example, while pre-school programs are

important for preparing poor children to succeed in elementary school,

(Dickens at 150-51), the number of Hartford children who are actually

enrolled in pre-school programs is woefully small compared to the

number who are eligible for them. (Dickens at 151),42

3 ’ The Concentration of Poverty and the Comparative Need for-

Resources. Defendants agree that progress in achieving equal

educational opportunities can be measured by comparing resources

420nly 600 out of 2,300

(Slavin at 36). four year olds receive preschool.

21

available to resources needed. (Pis' Ex. 163 at 233; pis' Ex. 39 .

Natriello II at 41-42) . Students in Hartford need more, not fewer

educational resources because of the concentration of at-risk

children43 in their classrooms.44

Indeed, it is undisputed that Hartford schools are not only

racially and ethnically segregated but also economically isolated.

(Stip. 113, 114, 118, 135, 136). A full 63% of Hartford students

receive federal free and reduced-priced lunches. Participation in the

lunch program is a measure of poverty. (Stip. 113). By comparison,

m fifteen of the twenty-one surrounding districts, fewer than 10% of

the students participate in the program. (Stip. 135). Hartford's

rate of poverty is in fact substantially greater than the rate among

students in any of the twenty-one surrounding districts. (Stip

136) .45

In 1980 and again in 1990, Hartford was ranked last in comparison

to the twenty-one surrounding communities for each of a number of key

43 (Stip. 140, 141).

4 4 ,. Schoolteachers testified that the concentration of at-risk

children m Hartford's classrooms overwhelms the normal teachina

process. (Dudley at 126-27; Anderson at 113; Negron I aT 74; §?iff^

at 86 ). In comparison, the education process can be conducted with

relative ease m non-poverty-concentrated schools. (Pitocco at 65-66-

Dudley at 128; Pis' Ex. 494 at 61-62 (Tirozzi Dep.) ) yVt wheA

regular program expenditures per "need student" of Hartford akd the

surrounding suburbs is compared, Hartford ranks at the bo?tom oi

twenty-two districts. (Pis' Ex. 163 at 161-62; Natriello I? at

16,000 children in the city of Hartford live in

a ■ - „ the sixth highest child poverty rate amnnrrAmerica s 200 largest cities. (Pis' Ex. 456). Y among

alf° demonstrated that the economic gulf between

-SUbUrbS 1S Wldening- (Defs' Ex. 8 .1, 82- Pis' Ex 163 at 152-53; Rmdone at 121) . • , ls Ex.

45More than

poverty, giving

22

s o c i o e c o n o m i c indicators, such as p e r c e n t a g e of n o n - E n g l i s h home

language, p e r c e n t a g e of p a r e n t s w i t h a h i g h school diploma, p e r c e n t a g e

of p a r e n t s wh o are m a n a g e r s or profess i o n a l s , p e r c e n t a g e of s i n g l e

p a r e n t families, and m e d i a n f a m i l y income. (Stip. 1 3 7 ) ,46

While each of these risk factors may increase the cost and

challenge of educating an individual student, what makes the plight

of Hartford's schoolchildren so difficult is the high concentration

of these factors in any given school. Even defendants' main witness

on the effects of individual socioeconomic status, David Armor

conceded the harmful effect of the concentration of poverty in the

schools. (Armor I at 148).47

Dr. Mary Kennedy testified at trial that achievement levels of

both poor and non-poor students are lower in high poverty

. . . In Edition, Hartford students are much more likely to enter

kindergarten delayed one to two years in educational development,

145 ' fitness crime and violence in their neighborhoods

(Morris at 140), arrive at school with high levels of anxiptv'

(Montanez at 12), and suffer from low self-esteem and poor social

skills as a result of poverty and isolation. (Montanez at 13- Morris

at 139; Noel at 25; Davis at 86). in one elemental school, Sere

were three attempted suicides in the last three years. Id Manv

children enter school at five or six years old suffering from severe

Defs^°Exent2 l8S at sPeech delays' (Montanez at 11; Negron I at 66; Dets Ex. 2.18 at 1), and some cannot form a sentence under^tanH

cognitively how to ask a question or describe items, oi articulate

"“ h 1aPPr°prlKat,e p a b u l a r y • (Cloud at 99; Hernandez at 35) Siring

the 1980s, between a fifth and a fourth of all of Hartford"!

kindergarten students were held back. <Defs' Ex. 2 18 at 5) Set

generally Stip. 113-149.

alS° agreed with plaintiffs' expert witnesses that the effect of the concentration of poverty within the schools can be

measureci independently of the effects of individual factors such as

155-Vc ? a S ^ ud®n^g®ocloeconomic status or student race. (Armor I at

23

concentration schools. (Kennedy at 26-28).48 In addition, children

in economically isolated schools fall increasingly behind as they

proceed in their education. (Kennedy at 41) . Moreover, Dr Trent

testified that independent of individual socioeconomic status and

race, the concentration of poor children in a student's school has

negative consequences not only for educational attainment, (Pis' Ex

48U, K, 0; Trent at 50, 56-59, 75-76), but also for occupational

attainment, (Pis' Ex. 481C; Trent at 34, 36, 38, 40, 74) , future

income, (Pis' Ex. 481g; Trent at 45, 75), and for the likelihood of

developing positive co-worker relations across racial lines. (Pis'

Ex. 481v).

While the impact of having a high concentration of poor students

in a school is far-reaching, (Kennedy at 28), reductions in poverty

concentration have been shown to have positive effects on student

achievement. (Kennedy at 28; Orfield I at 59-60) .

c - State Responsibility. Plaintiffs introduced a series of reports

and other documents to establish that the state has been aware at

least since the 1960s that the use of town lines to define school

districts has the effect of segregating students by race and ethnicity

in the public schools. (Pis' Ex. 1-90; Pis' Ex. 16 at 2; Finding 22,

147). These reports also document the state's awareness of the

harmful effects of racial and economic isolation on schoolchildren and

Dr. Kennedy, an expert in educational research methodsegress-* r sHSsS

children. (Kennedy at 6, 9 ). c o n c e n t r a t i o n s of p o o r

24

the inequalities between the educational opportunities provided by

Hartford and its suburbs. (Pis' Ex. 1-90; Finding 45; Defs' Ex. 2.29

12.25, 12.5) . 49

For example, as early as 1965, a report prepared by the Harvard

Graduate School of Education, described the growing problems of both

racial isolation and the concentration of poverty in the Hartford

schools. The Harvard report predicted increasing racial isolation in

Hartford schools in future years if strong steps were not taken to

promote integration. (Pis' Ex. I).50 a year later the Connecticut

Commission on Civil Rights urged defendants to respond to the

increasing segregation in Connecticut's schools.51 See also Pis' Ex

12a-b.52

49n

T h ? historical. s e q u e n c e of reports, studies, and

r e c o m m e n d a t i o n s c r e a t e d or r e c e i v e d b y the s tate is i n c l u d e d in Pis'

Ex. 1-90 and r e p r e s e n t e d g r a p h i c a l l y in Pis' Ex. 488.

5°A 1966 grant proposal submitted by 28 Hartford area

superintendents and transmitted to the state recommended

implementation of the Harvard plan. (Pis' Ex. 4) . The HarvardTepo??

was also relied upon in a December 1969 report of the State Department

al Education entitled "Racial Balance and Regionalization." (Pls^ Ex / / •

[It] is the view of the Commission that the failure t-n

^ 1^inat:e de ?acX° se9.re9ated schools not only condemns Negro children

^ e f ^ UIleqUal educatlon also tends to. perpetuate a segregated society by presenting segregation to all children as an acceptable

American way of life." The Commission also pointed out that "?UherI

^ e X l d ?n SS t ,̂at 1N e g r o c h i l d r e n s how i m p r o v e d a c a d e m i c p e r f o r m a n c e in i n t e g r a t e d school situ a t i o n s . " (Pis' Ex. 7a, 7c)

■ «. ?^nal recommendations of the Conference included a call for

m s " EX S aet 8C)ati0nal ParkS and transportation

25

Recommendations for effective i n te r d i s t r ic t relief, such as

educational parks, died in the legislature in the 1960s. In 1969 the

l^Uislsture passed the Racial Imbalance Act, an intrud istrict

desegregation law. The Connecticut legislature knowingly adopted the

Racial Imbalance Act despite warnings about the futility of

intradistrict approaches for urban school districts. (Pis' Ex. 23 at

218-D (Senator Barrows)).53 Soon after the adoption of the

regulations, the State Department of Education itself reported on the

uselessness of the Act in large urban districts with more than 75%

minority students. (Pis' Ex. 37 at 1-2). In a 1988 report, the

Hartford district stated, "as long as the boundaries of the attendance

district of the Hartford schools [are] coterminous with the boundaries

of the city, no meaningful numerical balance can be achieved, and it

would be an exercise in futility to develop proposals to seek racial

balance." (Pis' Ex. 53 at 1).

In January 1988 defendants released "Report on Racial/Ethnic

Equity and Desegregation in Connecticut's Public Schools," most often

referred to as "Tirozzi I." (Defs' Ex. 12.5).54 in April 1989

defendants issued "Quality and Integrated Education: Options for

53r

_ ■ 3The r̂ } a t i ° n s implementing the Racial Imbalance Act, which

equire each school's racial balance to match the demographics of the

district s overall population within 25%, were not finalized f o r

eleven years. (Conn. Agency Regs. §§ l0-2^6e-l et seq. ■ Gordon II at

49-51). Under the regulations, a 99% minority school could be in

<(P?^1ExCe5;T) 3 49% min°rity enr°Hment would violate the law

54r

d e s e ^ e p S and ^

the TOlU"ta^ cooperation ^ocal

26

Connecticut." (Pis' Ex. 60 ("Tirozzi II")). In December 1990 the

Governor's Commission on Quality and Integrated Education released its

report. (Pis' Ex. 73). Despite each report's acknowledgement of the

harms of segregated and unequal education, sense of urgency, and

detailed proposals, defendants have taken no significant steps to

carry out any of these studies' recommendations.55 (Gordon II at 72-

74, 77; Carter at 29, 41, 558; Williams, at 122-24; Pis' Ex. 494 at

101, 107, 113, 119-120 (Tirozzi Dep.); Pis' Ex. 56, 58, 59, 69, 70 (a

series of additional reports by defendants documenting the harms of

racial and economic isolation and the inequities between urban and

suburban school districts); Pis. Ex. 86).56

D. Remedy. It is clear that the harms demonstrated at trial can be

cured. Indeed, it is undisputed that a remedy in this case could be

The few scattered programs that defendants partially subsidize

such as Project Concern, affect few children. (Carroll at 9- n in'

Williams 94-97, 101, 115-16; Pis' Ex. 368; Stip. 253). ' '

261 rVrnc;ths / eiCne? cf eaSU,rne S ’ ,the state legislature, Public Act 93- 263, C.G.S. §§ 10 264a - 10-264k, An Act for Quality and Divert-i i-v

(Court Ex 1) merely describes a series of planning7 deadlines fo^ a

process that is not binding on the towns. The new law contains no

racial or poverty concentration goals, no guaranteed funding, and no

mandates for local compliance. (Finding 88; Stip. 88).

Among the problems identified in plaintiffs' exhibit 86 a

report released by the State Board of Education concern'ina

Connecticut's Limited English Proficient (LEP) students w e r e i f

almost 2,400 bilingual students (15%) were not even in a program’- 2

there was no special provision in the state statutes to protect'the

rights of LEP students,- 3) there was no state funding? to school

districts for providing language assistance-programs to LEP students-

4) pre-service training was not required for teachers in the bilingual'

programs; 5) there was a failure to require i n - s l u i c e t r a i n S T o r

■ .Work; 6) t?le cultural and linguistic wealth of LEP students was

not being recognized and was infrequently included in district-wide

curricula; 7) LEP students often lacked access to supplemental

°^Pjro9rfms available to English-proficient student- and 8)

the State had failed to conduct required annual evaluations' of thi bilingual program. (Pis' Ex. 86 at 2-3, 12, 14). uacions o l the

27

ordered to address racial and ethnic isolation, the concentration of

poverty, and the inadequacies in Hartford's public schools. Defendant

Ferrandino stated, "We believe that by breaking down [racial]

isolation and by eliminating concentrations of poverty we should see

improved student achievement." (Pis' Ex. 514 (Ferrandino statement);

Williams at 81-82) . Plaintiffs' experts Dr. Gary Orfield and Dr.

William Gordon testified that for more than three decades, communities

have formulated successful school desegregation plans by engaging in

court-ordered and expert-assisted planning processes. (Orfield I at

44-47; Gordon III at 24-29).

Any plan designed to remedy conditions of segregated and unequal

education in the Hartford area must be metropolitan-wide to be

effective. (Orfield at 32, 33; Willie at 41, 42, 49; Gordon II at 14;

Pis' Ex. 82 at 8) . Indeed, defendants agree with the need for a

multi-district solution. (Pis' Ex. 493 at 85, 151, 165 (Ferrandino

Dep.); Pis' Ex. 494 at 144 (Tirozzi Dep.); Pis' Ex. 495 at 25, 32-33

(Mannix Dep. ) ; Pis' Ex. 506 at 60 (Margolin Dep. ) ; Pis' Ex. 73, at 5) .

The parties also agree that reduction of both racial segregation and

the concentration of poor students in the schools are two of the

primary goals to be accomplished in a remedial plan. (Pis' Ex. 493

at 139 (Ferrandino Dep.); Calvert at 62-63).57

racial Pi d e n t ^ f f aShi D r ' G o r d o n t e s t i f i e d that e l i m i n a t i o n ofracial i d e n t i f l a b i l i t y r e q u i r e s not o n l y s t u d e n t a s s i g n m e n t but also

changes in f a c u l t y an d staff assignment, curriculum, t r a n s p o r t a t i o n

e x t r a c u r r i c u l a r a c t i v i t i e s an d school facilities. (Gordon II at L g ) ’

Indeed, plaint i f f s ' w i t n e s s A d n e l l y M a r i c h a l t e s t i f i e d about the nee d

to e n s u r e the c o n t i n u e d p r o v i s i o n of b i l i n g u a l e d u c a t i o n in

d e s e g r e g a t e d schools g i v e n the r e q u i r e m e n t that t h e r e be a critical

mas s of b i l i n g u a l s t u d e n t s for the* c r e a t i o n of a p r o g r a m ( S a r i c h S

28

It is also undisputed that effective schools can make a

difference in the educational outcomes of children regardless of their

socioeconomic background. (Orfield I at 138; Pis' Ex. 493 at 50-51,

131, 148 (Ferrandino Dep.) ; Pis' Ex. 494 at 91 (Tirozzi Dep.);

Williams at 31, 83; Pis' Ex. 506 at 59 (Margolin Dep.); Pis' Ex 73-

Finding 3) . Defendants concur that any remedial plan requires

educational enhancements. (Pis' Ex. 493 at 153 (Ferrandino Dep.);

Pis' Ex. 506 at 63 (Margolin Dep.); see Slavin at 13-14; Gordon II at

113; Orfield I at 51-53; Haig at 66).

ARGUMENT

I. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED AS A MATTER OF LAW IN FAILING TO FIND

STATE ACTION AND FAILING TO FIND THAT DEFENDANTS' ACTIONS

WERE CAUSALLY CONNECTED TO THE PROVISION OF UNEOUAL

EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES, THE CONDITIONS OF SEGREGATION

AND THE PROVISION OF INADEQUATE EDUCATION.

The court misapplied the law dealing with state action in

concluding that judgment should be entered in favor of the defendants

(R. at 166-79). As explained below, the trial court failed to follow

Connecticut precedent under which the question of "state action"

relates solely to determining whether constitutionally challenged

conduct is public or private. Instead, the court improperly conflated

the doctrine of state action with considerations of causation and

liability and standards of proof in discrimination cases. Moreover,

the trial court erred in failing to acknowledge uncontested evidence

that the State of Connecticut not only instituted the state-wide

system of education, which itself is sufficient to establish "state

at 36).

29

action," but also affirmatively contributed to the unconstitutional

conditions of which the plaintiffs complain. The Court further erred

in its misplaced reliance on aspects of federal jurisprudence which

inapplicable to the instant case because of the differences in the

substantive protection afforded by the Connecticut and by the United

States constitutions.

As a result of these errors, the plaintiffs were deprived of the

proper threshold ruling that education is a public function and that

the state is liable for existing constitutional deficiencies in public

education because of its role in creating, operating, and overseeing

the state educational system.

A- The Court Below Erred in Failing to Recognize the

Existence of State Action in Dismissing Plaintiffs'

Complaints of Unconstitutional Deprivation of a

Fundamental Right to Education.

In reaching the conclusion that "the constitutional claims

asserted by the plaintiffs need not be addressed" (R. at 179), the

trial court relied exclusively on a discussion of federal court cases

that dealt with questions of whether specific conduct of states and

local governmental entities violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution. (R. at 64-72) . This reliance is

misplaced not only because it deals with cases which speak to an issue

separate from the one before the Court but because it wholly ignores

Connecticut case law unequivocally supporting the right of plaintiffs

to have their complaints heard and considered by the court

30

Public education is a oubl-ic function chat

necessarily involves state action.

1.

The provision of elementary and secondary education in the state

of Connecticut is undeniably a public rather than private function

that the state has undertaken for most of its history: "Connecticut

has for centuries recognized it as her right and duty to provide for

the proper education of the young. » State ex. rel. Huntington v. Huntington School

Committee, 82 Conn. 563, 566, 74 A. 882 (1909) .

The degree of state control and involvement in the operation of

the public system of education is evidenced in the statutes that

provide the right to an education and delegate the authority to

implement that right: Conn. Const. Article VIII § i (providing for

free public schools); C.G.S. § 10-4a (identifying educational

interests of the state); C.G.S. § 10-220 (defining duties of boards

of education); C.G.S. § 10-240 (providing for town control of public

schools within town limits); C.G.S. § 10-241 (defining powers of

school districts).

The fact that the day-to-day operations of the separate school

districts occur on the local level does not alter the fact that the

ultimate responsibility for providing education is a public function

entrusted to the state.-

The same basic educational system has continued to this

?a5®' ^ *tateL :rJc°9ni2ing that providing for education is

a state duty and function now codified £n the constitution

article eighth, § 1, with the obligation of overseeing

education at the local level delegated to local school

boards which serve as agents of the state.

31

Horton v. M eskill, 172 Conn. 615, 647, 376 A. 2d 359 (1977) (Horton I) (citing

Murphy v. Berlin Board o f Education, 167 Conn. 368, 372, 355 A. 2d 265 (1974));

West Hartford Education Association v. D eCourcy, 162 Conn. 566, 573, 295 A.2d 526

(1972) . See Finding 1 .

The court below has itself recognized that the public nature of

the state's involvement in the state system is sufficient to satisfy

any state action requirement:

Public schools are creatures of the state, and whether the

condition whose constitutionality is being attacked is

®tate—created or state-assisted or merely state-

perpetuated should be irrelevant" to the determination of

the constitutional issue. Educational authorities on the

state and local level are so significantly involved in the

control, maintenance and ongoing supervision of their

school systems as to render existing school segregation

"state action" under a state's constitutional ecrual

protection clause. M

(R. at 99)(citation omitted).

Plaintiffs believe that this earlier decision by the trial court

was correctly decided and that the same factors apply. Accordingly,

any state action requirement has been met.

2 • Cologne v. Westfarms Associates y i e l d s thg, same t-p r u H-

In Cologne v. Westfarms Associates, 192 Conn. 48, 469 A. 2d 1201 (1984)

this Court considered whether a political advocacy group could be

denied access to a common area of a privately owned shopping mall.

In deciding that the owners could not be required to provide access,

the Court held that the Connecticut Constitution was intended to guard

against governmental and not private interference with constitutional

rights. Cologne, 192 Conn, at 61; see also Lockwood v. K illian, 17 2 Conn. 4 96

32

375 A. 2d 998 (1977) (private conduct abridging individual rights does

not violate equal protection clause). The Court found that in the

absence of state action, plaintiffs could not assert their right to

constitutional protection. In the dissenting opinion, Justice Peters

and Judge Sponzo disagreed on the grounds that they believed that

Connecticut law did not require that there be expressly public

involvement or, alternatively, that the nature of shopping malls is

such that they have assumed "a uniquely public character" and thereby

take on governmental characteristics. Cologne, 192 Conn, at 82

(Peters, J., dissenting).

Application of each of the various analyses set forth in Westfarms

to the instant case yields the same result. The facts of this case

fit squarely within the requirements of both the majority and

dissenting opinions in Westfarms because a constitutional right is

implicated and the nature of the interest in public education is such

that it would satisfy both those who believe that only state action

is subject to review by the courts and those who believe that there