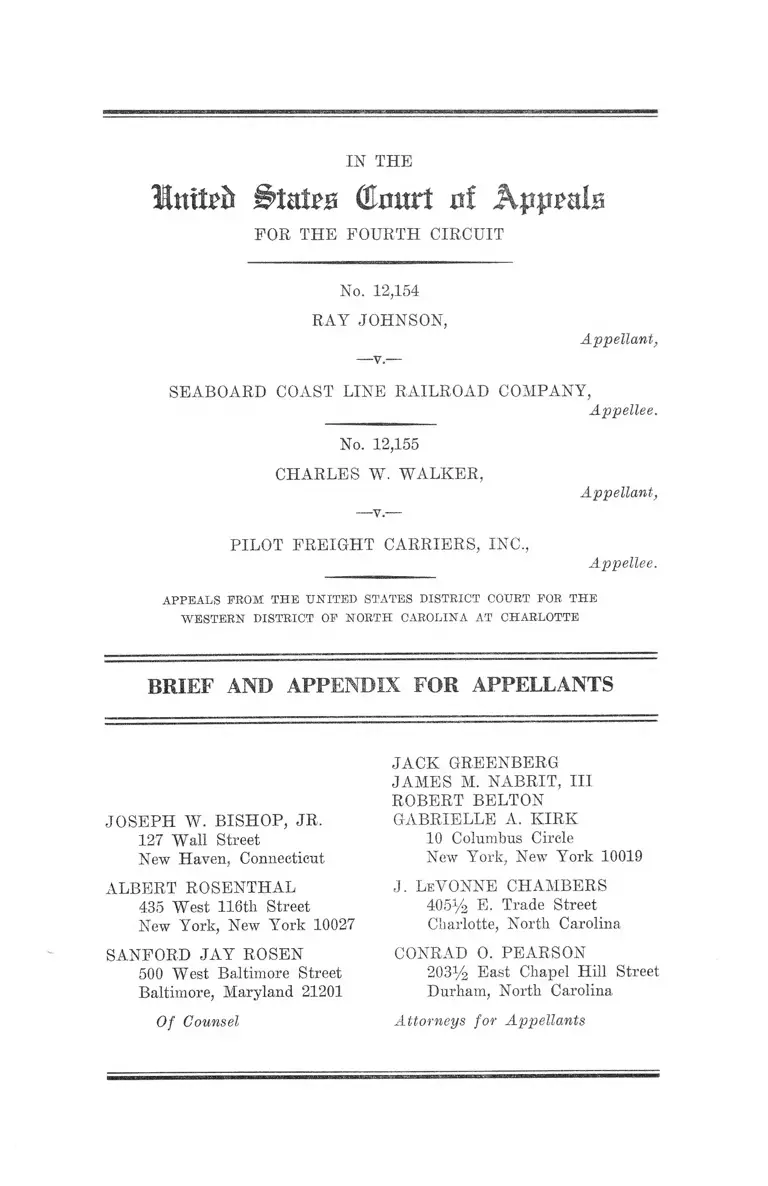

Johnson v. Seaboard Coastline Railroad Company Brief and Appendix for Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 18, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Johnson v. Seaboard Coastline Railroad Company Brief and Appendix for Appellants, 1966. 4868751a-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/eaf775e8-19db-4d5e-b933-987b93a613de/johnson-v-seaboard-coastline-railroad-company-brief-and-appendix-for-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Intteis States Court ni Appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 12,154

RAY JOHNSON,

—v.—

Appellant,

SEABOARD COAST LINE RAILROAD COMPANY,

Appellee.

No. 12,155

CHARLES W. WALKER,

Appellant,

PILOT FREIGHT CARRIERS, INC.,

Appellee.

APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHARLOTTE

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR APPELLANTS

JOSEPH W. BISHOP, JR.

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut.

ALBERT ROSENTHAL

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

SANFORD JAY ROSEN

500 West Baltimore Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21201

Of Counsel

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

ROBERT BELTON

GABRIELLE A. KIRK

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

405% E. Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

CONRAD O. PEARSON

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the Cases .................. ..................... ........ 1

Statement ...................... ................................................ 3

Question Involved ........................................... .......... — 4

Summary of Argument .... ................................ ............ 4

A r g u m en t

I. Nothing in the Language of Title VII of the Civil

Eights Act of 1964 Conditions the Eight of the

Person Aggrieved to File Suit Upon the Commis

sion’s Having Undertaken Efforts to Conciliate .... 6

II. Nothing in the Legislative History of Title VII

Justifies Heading Its Language in Such a Way as

to Make the Commission’s Compliance With the

Direction of Section 706(a) a Jurisdictional Pre

requisite to the Eight of the Person Aggrieved

to File a Civil Action Under Section 706(e) ...... 8

III. It Would Be Unfair and Unreasonable to Construe

the Act in Such a Way as to Make the Eight of

One Who Is Denied the Eights Which It Confers

to Seek Judicial Enforcement of Such Eights Upon

Circumstances Altogether Beyond His Control .... 10

IV. The EEOC’s Contemporaneous Interpretations of

Title VII, Which Are Entitled to Great Weight,

Eequire the Conclusion That the Provisions in the

Statute for “Conference, Conciliation and Persua

sion” by the Commission Are Directory and Do

Not Constitute a Jurisdictional Prerequisite to the

Eight of the Person Aggrieved to Bring Suit .... 13

PAGE

V. With a Single Exception, Courts Considering the

Issue Here Presented Have Beached a Conclusion

Contrary to That of the Court Below ................. 15

C o n c lu sio n ......................................................... ............... ................ 19

A ppe n d ix —

No. 12,154

Letter dated August 8, 1966 from EEOC ............. la

Decision by EEOC ........ *................... ... ................ 3a

Letter dated August 8, 1966 from EEOC ............ 6a

Complaint...... ................. ........... ...................... 7a

Motion to Dismiss .... —-_________...i_________ 13a

Motion to Amend Motion to Dismiss ................... 14a

Order Granting Substitution .......... ....................... 16a

Letter dated November 3, 1967 of Judge Gordon .... 17a

Order Denying Motion to Dismiss in Shirley

Lea, et al. v. Cone Mills Corporation __ __ 22a

Order Denying Motions to Dismiss in Dorothy

P. Robinson, et al. v. P. Lorillard Company,

et al. ........ ............................................... ........ 24a

Order Granting Motion to Dismiss ..... ......... ....... 26a

Memorandum of Decision ....................... ............... 27a

Notice of Appeal ......... .................... ................... . 34a

No. 12,155

Letter dated August 5, 1966 from EEOC_______ 37a

ii

PAGE

I l l

Decision by EEOC.................................................. 39a

Letter dated August 5, 1966 from EEOC............. 42a

Complaint ....................................... 43a

Motion for Preliminary Injunction ...................... 50a

Motion to Dismiss .............. .......... ... ........... ........ 52a

Order Dismissing Action ....................................... 53a

Notice of Appeal..................................................... 54a

Extracts From Statutes ......... 55a

PAGE

T able of C ases

Anthony v. Brooks, 65 L.R.R.M. 3074 (N.D. Ga. 1967) 16

Bowe v. Colgate Palmolive Co., 212 F.Supp. 332 (S.D.

Ind. 1967) ........ 15

Choate v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., 274 F.Supp. 776

(S.D. 111. 1967) .......................................................... 17

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Co., 265 F.

Supp. 56 (N.D. Ala. 1967) .........................................8,15

Ethridge v. Rhodes, 268 F.Supp. 83 (S.D. Ohio, 1967) 12

Evenson v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 278 F.Supp. 29

(E.D. Va. 1967) ..................................................7,10,16

Hall v. Werthan Bag Corporation, 251 F.Supp. 184

(M.D. Tenn. 1966) .......................................... 8,9,10,18

International Chemical Workers Union v. Planters

Mfg. Co., 259 F.Supp. 365 (N.D. Miss. 1966) 13

IV

Lea v. Cone Mills, Civ. No. 2145 (W.D. N.C. June 27,

. (1967) ...................... ................................ .................. 15

Miekel v. South. Carolina State Employment Service,

377 F.2d 239 (4th Cir. 1967) ......................... ......... 1.7

Mondy v. Crown Zeilerbach Corporation, 271 F.Supp.

258 (E.D. La. 1967) ...................... .................. 7,10,11,15

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 271 F.Supp. 26 (E.D.

N.C. 1967) .............. (.......................... ....................... 8

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 271 F.Supp. 842 (E.D.

Va. 1967) ........ .................... .................. .......... ........11,16

Reese v. Atlantic Steel Co., 56 L.C. 119096 (N.D. Ga.

July 21, 1967) __________________ ___ _________ 11

Robinson v. P. Lorillard, Civ. No. C-141-G-66 (M.D.

N.C. Jan. 26, 1967) .......... ............ ............................ 15

Skidmore v. Swift, 323 U.S. 134 (1944) ..................... 13

Stebbins v. Nationwide Mutual Ins. Co., 382 F.2d 267

(4th Cir. 1967) ..... .............. ............................ .......... 17

United States v. American Trucking Associations, 310

U.S. 534 (1940) ........................................................... 13

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff’d oil rehearing en

bane, 380 F.2d 385 (1967) ........ ....................... ......... 13

Ward v. Firestone Tire & Rubber Co., 260 F.Supp. 579

(W.D. Tenn. 1966)

PAGE

1 1

IV

S tatutes

page

42 U.S.C. §2000e, et seq.

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964

Section 706 (a) 42 U.S.C. §2000e -5(a) ....6, 7,10,11

Section 706 (e) 42 U.S.C. §2000e -5(e) ..2, 3, 4, 5, 6,

7, 8,14,15,16

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

29 C.F.R. §1601.25a(b) ................................................. 14

110 Cong. Rec. 14191, June 17, 1964 .... ......... ............. 9

110 Cong. Rec. 14188, June 17, 1964 ............................ 9

88 Congress, 1st Sess.

H.R. Rep. No. 914, Nov. 20, 1963 ........................ 8

H.R. Rep. No. 540, July 22, 1963 ......................... 8, 9

G-.C. Opins. 10/22/65 and 11/1/65 (reprinted in Com

merce Clearing House, Employment Practices

Guide, 1117,252.32) ........... ........... .............................. 14

31 Fed. Reg. 14255 (Nov. 4, 1966) .............................. 14

I n T H E

luifcft States Court of Appeals

F ob t h e F o u r th C ir c u it

No. 12,154

E ay J o h n so n ,

Appellant,

— v .—

S eaboard C oast L in e R ailroad C o m pany ,

Appellee.

No. 12,155

C h arles W . W a lk er ,

Appellant,

P ilot F r eig h t C arriers, I n c .,

Appellee.

appeals from t h e u n it e d states district court for t h e

W E S T E R N D ISTR IC T OF N O R T H CAROLINA AT CH A RLO TTE

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Cases

These are appeals, in two similar eases, from final judg

ments of the United States District Court for the Western

District of North Carolina, dismissing the complaint in

each case.

2

In each, ease the appellant filed a complaint with the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (hereinafter

sometimes referred to as “EEOC” or “the Commission”),

alleging violation of Title VII of the Civil Eights Act of

1964, 42 IT.S.C. §§2000e et seq. In each case the Commis

sion found reasonable cause to believe that the appellee

had violated Title VII by denying the appellant equal

employment opportunities, and so informed the appellee

in writing, stating that a conciliator appointed by the

Commission would contact it in order to discuss means of

correcting the discrimination. The District Court found,

however, that the Commission did not attempt conciliation

in either case prior to the filing of suit. In each case the

Commission sent the appellant a letter informing him that

due to the Commission’s heavy workload it had been im

possible to conclude conciliation efforts in his case and

that he was entitled to bring an action in the Federal Dis

trict Court within thirty days after receipt of the letter.

Appellant Johnson filed his complaint with the Commis

sion on January 14, 1966; was notified by the Commission

on August 9, 1966, that he was entitled to bring suit within

thirty days; and filed his complaint in the present action

on September 7, 1966. Appellant Walker filed his complaint

with the Commission on February 28, 1966, and amended

it on March 15, 1966; he was notified by the Commission

on August 5, 1966, that he was entitled to bring suit within

thirty days, and filed suit on August 23, 1966.

In each case the appellee moved to dismiss the action

for lack of jurisdiction on the ground, inter alia, that the

Commission had not prior to the filing of the action at

tempted to eliminate the alleged violations of the Act by

informal methods of conference, conciliation, and persua

sion. Appellants’ Appendix pages 14a, 52a (hereinafter

cited as “App. p. —”).

3

On January 25, 1968, the District Court entered Orders

dismissing each action, on the sole ground that “resort to

the remedy of conciliation is a jurisdictional prerequisite

to the right to file and maintain a civil action under the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, and that since there was no such

effort made, the motion should be allowed.” Each Order

was based upon a Memorandum of Decision filed in the

Johnson case (App. pp. 26a, 53a).

The question involved in each case is whether one who

has allegedly been denied his rights under Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is barred from instituting

suit under section 706(e) of the Act because of the Com

mission’s failure to attempt to secure voluntary compliance

from the defendant by conciliation.

Statements

Johnson v. Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company

(No. 12,154)

On January 14, 1966, appellant Johnson filed a charge

of employment discrimination with the Commission against

the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company alleging a

violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The

Commission investigated the charge and on July 18, 1966

found “reasonable cause” to believe the charge was true

(App. pp. 3a-5a). By letter dated August 8, 1966, the Com

mission notified Johnson that it had found it “impossible

to undertake or conclude conciliation,” and that he had a

right to institute a civil action within thirty days of re

ceipt of the letter (App. pp. la-2a). Johnson then com

menced an action by filing a complaint in the court below

on September 7, 1966.

4

W alker v. Pilot Freight Carriers, Inc.

(No. 12,155)

Appellant Walker filed a charge of employment dis

crimination with the Commission against Pilot Freight

Carriers on February 28, 1966, and amended it on March

15, 1966 alleging a violation of the Civil Eights Act of 1964.

The Commission investigated the charge and on July 20,

1966, found “reasonable cause” to believe the allegations

made in the charge were true (App. pp. 39a-40a). By letter

dated August 5, 1966, the Commission notified Walker

that it had been “impossible to undertake or conclude con

ciliation,” and that he had a right to institute a civil

action within thirty days of receipt of the letter (App. pp.

37a-38a). Walker commenced this action by filing a com

plaint in the court below on August 23, 1966.

Question Involved

Did the District Court err in holding that conciliation

efforts by the Commission are a jurisdictional prerequisite

to the institution by the person aggrieved of a civil action

under section 706(e) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964!

Summary o f Argument

1. The plain language of the statute does not make con

ciliation by the Commission a jurisdictional prerequisite

to an individual’s right to bring a civil action to enforce

his rights under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Section 706(e) of the Act governs the prerequisites to such

an action, and it requires Only that the aggrieved person

have filed a charge with the Commission; that the Commis

sion have “been unable to obtain voluntary compliance” ;

that it shall so notify the person aggrieved; and that he

5

have filed suit within thirty days of such notification. All

of these requirements wTere met in the instant cases. There

is no warrant for reading into the conditions imposed by

section 706(e) on suit by the person aggrieved the direc

tion of section 706(a) to the Commission to endeavor to

effect compliance by conciliation.

2. The legislative history of the Act does not justify a

construction which makes attempted conciliation by the

Commission a condition precedent to the right of a per

son aggrieved to seek judicial enforcement of his statutory

rights. Most of the statements relied upon by the court

below were made at a time when the bill contemplated

judicial enforcement by the Commission arid are not rele

vant to the question of what Congress intended under the

Act as passed, which places the burden of judicial enforce

ment upon the person aggrieved, who has no control over

(and may have no knowledge of) the Commission’s action

or inaction. They are contradicted by authoritative state

ments made after the bill had been amended to shift the

burden of enforcement from the Commission to the alleged

victim of discrimination.

3. It is highly unlikely that Congress intended the ex

treme unfairness of making the judicial remedy which it

granted to an individual for violation of his rights under

the Act depend upon actions of an administrative agency

which he could neither control nor influence.

4. The administrative construction of the Act which the

court below ascribed to the Commission is inconsistent with

the Commission’s own statements and policies, which fully

support the construction urged by the appellants.

5. With a single exception, every other court which has

decided the question here presented has reached a conelu-

6

sion contrary to that of the court below. That exception,

which was chiefly relied upon by the court below, rests upon

what other courts and the appellants regard as a mis

reading of the Act’s legislative history. Other cases cited

by the court below deal with the totally different question

of the effect of the complainant’s own failure properly to

invoke or exhaust his administrative remedies.

ARGUMENT

I.

Nothing in the Language of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 Conditions the Right of the Person

Aggrieved to File Suit Upon the Commission’s Having

Undertaken Efforts to Conciliate.

Section 706(a) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §2000e—5(a), upon

which the court below chiefly relied, undoubtedly directs

the Commission, if it finds reasonable cause to believe that

a charge of discrimination is true, to ‘‘endeavor to elim

inate any such alleged unlawful employment practice by

informal methods of conference, conciliation and persua

sion.” But the statute as finally passed places the burden

of judicial enforcement not on the Commission but on

the person aggrieved by the alleged violation, and it is

section 706(e) which governs his right to file suit. That

section provides in pertinent part that:

If within thirty days after a charge is filed with the

Commission . . . (except that . . . such period may

be extended to not more than sixty days upon a de

termination by the Commission that further efforts

to secure voluntary compliance are warranted), the

Commission has been unable to secure voluntary com

pliance with this title, the Commission shall so notify

7

the person aggrieved, and a civil action may, within

thirty days thereafter, be brought against the respon

dent named in the charge. . . .

It is apparent that the word “thereafter” refers to the

Commission’s notification to the person aggrieved. Noth

ing in the language of either section 706(a) or section

706(e) requires him to ensure that the Commission has

obeyed the direction of section 706(a), or conditions his

right to bring suit upon any action on the Commission’s

part other than its notifying him of its inability to secure

voluntary compliance within the statutory period. “42

U.S.C. §20Q0e—5 [Sec. 706(a)] does command E.E.O.C.

to attempt conciliation, but it does not prohibit a charg

ing party from filing suit when such an attempt fails to

materialize.” Mondy v. Crown Zellerbach Corporation, 271

F. Supp. 258, 262 (E.D. La. 1967). “Section 2000e [Sec.

706(e)] of the Act expressly gives the aggrieved party

the right to sue if the Commission has been unable to

obtain voluntary compliance with this sub-chapter.” Even-

son v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 278 F. Supp. 29, 32 (E.D.

Va. 1967). In sum, the explicit language of the Act places

only two conditions upon the aggrieved person’s right to

bring suit; that he have filed charges with the Commis

sion in proper form and that he have been notified by the

Commission of its inability (for whatever reason) to ob

tain voluntary compliance.

The statutory scheme of enforcement is entirely consistent

with this plain language. Section 706(e) makes it clear the

Commission’s action or inaction should not postpone for

more than sixty days the right of the person aggrieved to

file suit, even if the Commission should desire additional

time for conciliation, section 706(e) permits it only to re

quest, after the person aggrieved has filed suit, that the

court in its discretion grant a stay of sixty days. Indeed,

8

it appears that not even the Commission’s refusal to find

reasonable cause to believe that his charges are true can

deprive the person aggrieved of his right to bring suit.

See Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 271 F. Supp. 26 (E.D.

N.C. 1967); Hall v. Werthan Bag Corporation, 251 F. Supp.

184, 188 (M.D. Tenn. 1966).

II.

Nothing in the Legislative History of Title VII Jus

tifies Reading Its Language in Such a Way as to Make

the Commission’s Compliance With the Direction of

Section 706(a) a Jurisdictional Prerequisite to the

Right of the Person Aggrieved to File a Civil Action

Under Section 706(e).

The court below bottomed its construction of the statute

largely upon its reading of its legislative history, citing in

support of its views the only other case to reach the same

result, Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Company,

265 F. Supp. 56 (N.D. Ala. 1967). Other courts have found

the legislative history considerably less illuminating. See,

e.g., Mondy v. Crown Zellerbach Corporation, supra, at

271 F. Supp. 262; Hall v. Werthan Bag Corporation, supra,

251 F. Supp. at 186. The legislative remarks quoted in the

memorandum decision of the court below, which undoubt

edly express the view that the Commission would have to

try conciliation before it could seek judicial enforcement,

were made at a time when the bill still provided for judicial

enforcement only at the suit of the Commission. The same

thing is true of most of the other items of legislative history

cited in the Dent case to support its conclusion that efforts

by the Commission to conciliate were a jurisdictional pre

requisite to suit under the Act. E.g., H.R.Rep. No. 540,

88th Cong., 1st Sess., July 22, 1963; H.R.Rep. No. 914, 88th

9

Cong,, 1st Sess., Nov. 20, 1963. “Congressional machinery,

however, turned the enforcement provisions of Title VII

inside out. The Commission was stripped of its authority

to issue orders by the House Judiciary Committee and

stripped of its power to prosecute court actions by the

leadership compromise in the Senate. The emphasis shifted

toward the vindication of individual rights, and the burden

of enforcement shifted from the Commission to the ‘person

aggrieved.’ ” Hall v. Werthan Bag Corporation, supra, at

251 F. Supp. 186. The change made largely irrelevant the

views on jurisdictional prerequisites expressed at a time

when the legislators were discussing a wholly different sys

tem of enforcement. While it was perfectly reasonable and

natural for the legislators to assume that the Commission’s

right to bring suit was conditioned upon its compliance

with the statutory direction to try conciliation first, there

is no warrant for assuming that the Congressmen would

have expressed similar views as to the aggrieved person’s

right to bring suit under the substituted scheme of enforce

ment. After the shift, Senator Javits, a principal sponsor

of the revised bill, expressed his understanding unequivo

cally (110 Cong. Rec. 14191, June 17, 1964):

“In short, the Commission does not hold the key to the

courtroom door. The only thing this title gives the

Commission is time in which to find that there has been

a violation and time in which to seek conciliation . . .

[T]his provision gives the Commission time in which

to find that there exists in the area involved a pattern

or practice, and it also gives the Commission time to

notify the complainant whether it has or has not been

successful in bringing about conciliation.

# # # *

But . . . that is not a condition precedent to the action

of taking a defendant into court. A complainant has an

1 0

At least two district courts have found this statement by

one who was intimately connected with the sponsorship of

the new bill more persuasive than an earlier inconsistent

statement by Senator Ervin (110 Cong. Eec. 14188, June

17, 1964), which Senator Javits apparently intended to

correct. See Hall v. Werthan Bag Corporation, supra, at

251 F. Supp. 188; Mondy v. Crown Zellerbach Corporation,

supra, at 271 F. Supp. 262-263.

III.

It Would Be Unfair and Unreasonable to Construe the

Act in Such a Way as to Make the Right of One Who

Is Denied the Rights Which It Confers to Seek Judicial

Enforcement of Such Rights Upon Circumstances Al

together Beyond His Control.

The fundamental purpose of the Act is to give to the per

sons for whose protection it was enacted rights which they

can enforce by resort to the federal courts. Such persons

are required first to do what lies in their power to enforce

their rights through the Commission’s good offices. These

appellants have done that. They filed complaints in proper

form with the Commission and were notified that it had

been unable to effect voluntary compliance. No further

steps were open to the appellants. “To require more would

be to deny a complainant the right to seek redress in the

courts, resulting wholly from circumstances beyond her con

trol.” Evenson v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 268 F. Supp. 29,

31 (E.D. Va. 1967).

Other district courts have similarly refused to “read the

requirement of §2000e-5(a.) into § 2000e-5(e)” because of

absolute right to go into court, and this provision does

not affect that right at all.”

1 1

the obvious unfairness of such an interpretation. “Surely

Congress could not have intended for an aggrieved party

to be denied his remedy under Title VII because of the

failure of the E.E.O.C. to notify him within 60 days.”

Mondy v. Crown Zellerbach Corporation, 271. F. Supp. 258,

261, 262 (E.D. La. 1967); see Ward v. Firestone Tire &

Rubber Co., 260 F. Supp. 579, 580 (W.D. Tenn. 1966) (“the

result contended for by defendants would be anomalous in

that plaintiff would in a sense be penalized because of the

failure of the Commission to perform its statutory duties

within the time allowed”) ; Reese v. Atlantic Steel Co., 56

L.C. Tf9096 (N.D. G-a. July 21, 1967): (“This Court cannot

escape the conclusion that the plaintiff has done all that

is humanly possible to comply with the statute. His statu

tory rights cannot go unprotected due to the failure of the

Commission”).

In Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 271 F. Supp. 842, 846-7

(E.D. Va. 1967), a case substantially identical with the

present ones, Judge Butzner phrased the argument co

gently:

“It is apparent that Quarles and Briggs did all within

their power to exhaust their administrative remedies.

Complaints were made to the Commission in writing.

Quarles filed suit and Briggs intervened only after they

were advised by the Commission in writing that “con

ciliation efforts of the Commission have not achieved

volntary compliance with Title VII of the Civil Bights

Act of 1964.” . . .

Quarles and Briggs fully complied with 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5. They are not required to prove what efforts,

if any, the Commission made to conciliate. Indeed,

§ 2000e-5(a) severely restricts information concerning

conciliation.

1 2

The plaintiff is not responsible for the acts or omis

sions of the Commission. He, and the members of his

class, should not be denied judicial relief because of

circumstances over which they have no control. The

plaintiff exhausted administrative remedies and satis

fied the requirements of the Act by filing a complaint

with the Commission and awaiting its advice. He is

not required to show that the Commission has endeav

ored to conciliate. To insist that he do so, would re

quire him to pursue an administrative remedy which

may be impossible to achieve. If the Commission makes

no endeavor to conciliate, the remedy is ineffective and

inadequate.

In this circuit the rule is clear. Judge Sobeloff wrote,

in Marsh v. County School Bd. of Roanoke Co., Va.,

305 F.2d 94, 98 (4th Cir. 1962):

“The requirement that a plaintiff shall exhaust his ad

ministrative remedies before applying for judicial re

lief presupposes that the remedy to which he is referred

is an effective one. As we said in McCoy v. Greensboro

City Board of Education, 283 F.2d 667, 670 (4th Cir.

1960), ‘It is well settled that administrative remedies

need not be sought if they are inherently inadequate or

are applied in such a manner as in effect to deny the

petitioners their rights.’ ”

The results of the Orders below is to, at least, postpone

for several months the plaintiffs’ vindication of their rights.

Such postponement would weaken and, perhaps, altogether

frustrate congressional purpose. See Ethridge v. Rhodes,

268 F. Supp. 83, 88 (S.D. Ohio, 1967).

13

IV.

The EEOC’s Contemporaneous Interpretations of Title

VII, Which Are Entitled to Great Weight, Require the

Conclusion That the Provisions in the Statute for “Con

ference, Conciliation and Persuasion” by the Commis

sion Are Directory and Do Not Constitute a Jurisdic

tional Prerequisite to the Right of the Person Aggrieved

to Bring Suit.

The primary responsibility for determining when the

Commission is unable to obtain compliance with Title VII

is imposed upon the Commission itself. When it makes this

determination it sends the person aggrieved a letter so

advising him, and that person has thirty days thereafter in

which to bring an action. The Commission sent such letters

to the appellants in these cases. These letters constitute

administrative findings of inability. This practice consti

tutes a contemporaneous construction of the statute by the

administrative agency empowered to apply it, and there

fore is entitled to great •weight. E.g., Skidmore v. Swift,

323 U.S. 134, 137, 139-40 (1944); United States v. American

Trucking Associations, 310 U.S. 534 (1940); United States

v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836 (5th

Cir. 1966), aff’d on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (1967);

International Chemical Workers Union v. Planters Mfg.

Co., 259 F. Supp. 365, 366-67 (N.D. Miss. 1966) (EEOC’s

construction of Title VII).

At the time the appellants received their notices and

filed suit, the Commission’s practice was as follows:

“Where the Commission is unable to conduct a complete

investigation or issue its findings during the statutory

periods, or where the Commission finds no reasonable

cause to believe that the charge is true, the charging party

14

can nonetheless file a suit pursuant to section 706(e).”

G-.C. Opins. 10/22/65 and 11/1/65 (reprinted in Commerce

Clearing House, Employment Practices Guide, 1)17,252.32)

(Emphasis supplied).

After the appellants received their notices, the Com

mission changed its rule to provide that it “shall not issue

a notice . . . where reasonable cause has been found, prior

to efforts at conciliation with respondent, except that the

charging party or the respondent may upon the expiration

of 60 days after the filing of the charge or at any time

thereafter demand in writing that such notice issue, and

the Commission shall promptly issue such notice to all

parties.” 29 C. F. E. §1601.25a(b) (Emphasis supplied).

This is the “new regulation” upon which the court below

relied.

In promulgating this “new regulation,” the Commissi on

expressed its view “that in general the purposes of Title

YII are better served by delaying the notification under

section 706(e) until the proceedings before the Commis

sion have been completed.” 31 Fed. Eeg. 14255 (Nov. 4,

1966). Nevertheless, it recognized “that there may be cir

cumstances under which either the charging party or the

respondent may desire that the right to bring an action

accrue as promptly as possible upon the expiration of the

60-day period, and where such a desire is clearly mani

fested, we believe it consistent with the statutory scheme

that notification issue irrespective of the status of the case

before the Commission.” 31 Fed. Eeg. 14255 (Nov. 4,

1966). The current rule, and the earlier one, are plainly

more consistent with the purposes and language of Title

VII than an interpretation requiring actual efforts at con

ciliation as a jurisdictional prerequisite to the filing of a

civil action by the person aggrieved.

15

y.

With a Single Exception, Courts Considering the Issue

Here Presented Have Reached a Conclusion Contrary

to That of the Court Below.

There are eight other reported decisions involving the

question here at issue—i.e., whether the Commission’s fail

ure to comply with the directions of section 706(a) respect

ing conciliation is a bar to the filing of a civil action by a

victim of discrimination who has himself met all of the

statutory prerequisites to suit. One, Dent v. St. Louis-San

Francisco Railway Company, 265 F. Supp. 56 (N.D, Ala.

1967), held that it is. That case is now on appeal to the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The district court’s

decision in the Dent case results principally from a reli

ance on the Act’s legislative history prior to the decision

to switch the burden of enforcement from the Commission

to the individual victim of alleged discrimination. (App. p.

31a.) As indicated in Part II of this Argument, supra,

the appellants believe this reliance to be misplaced. Sec

ondarily, the court pointed to what it regarded as the Com

mission’s administrative construction. (App. p. 33a.) For

the reasons given in Part IV of this Argument, the appel

lants believe that the Dent court’s understanding of the

Commission’s construction of the Act is erroneous.

The other seven cases in which the question has been

decided all support the appellants’ position.* Mondy v.

Crown Zellerbach Corp., 271 F.Supp. 258 (E.D. La. 1967);

Rowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 272 F.Supp. 332 (S.D,

Ind. 1967); Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 271 F.Supp.

* Several unreported decisions support appellants’ position also:

Robinson v. P. Lorillard, Civ. No. C-141-G-66 (M.D. N.C. January

26, 1967) (App. pp. 22a-23a); Lea v. Cone Mills, Civ. No. 2145

(W.D. N.C. June 27, 1967) (App. pp. 24a-25a).

16

27 (E.D. N.C. 1967); Evens on v. Northwest Airlines, Inc.,

268 F.Supp. 29 (E.D. Ya. 1967); Quarles v. Philip Morris,

Inc., 271 F.Supp. 842 (E.D. Va. 1967); Reese v. Atlantic

Steel Co., 56 L.C. 119096 (N.D. Da. 1967); Anthony v.

Brooks, 65 L.R.R.M. 3074 (N.D. Ga. 1967). The con

sideration which seemed compelling to these courts was

the unlikelihood that Congress intended such unfairness

as penalizing the persons aggrieved for administrative

action or inaction of the Commission, which was quite

beyond their control.

The court below attempted to distinguish the Quarles,

Evenson and Moody cases on the basis of what it per

ceived to be differences in the wording of the Commis

sion’s notifications to the parties that voluntary com

pliance had not been effected and that they were free

to sue (App. pp. 30a-31a). In fact, however, the wording

of the notifications to the defendants in Quarles and in

Evenson is exactly the same as that received by the de

fendant in the Johnson case. Each defendant was advised

that “since the charges were filed in the early phases of

the administration of Title VII, the Commission had been

unable to conciliate the matter within sixty (60) days”

and therefore was obligated to advise the charging party

of his right to bring a civil action (Quarles, supra at 845;

Evenson, supra at 31). Likewise, the facts in Johnson and

in Moody are indistinguishable. In Moody, as in Johnson,

no attempt at conciliation had been made prior to suit;

moreover, the Commission in Moody had not even com

pleted its investigation of the charge at the time suit was

filed. Additionally, a reading of the opinions in Quarles,

Evenson and Moody makes it obvious that the courts did

not attach any importance to the wording of the notice.

17

The other eases cited by the court below (App. p. 32a)

are not in point, and none is inconsistent with the. appel

lants’ position. In each, suit was dismissed because the

person aggrieved had himself failed properly to invoke

the administrative remedies available to him. In Michel

v. South Carolina State Employment Service, 377 F.2d

239 (4th Cir. 1967), the complainant attempted to sue

an employer whom she had not charged before the Com

mission. This Court affirmed a grant of summary judg

ment for the defendant employer on the explicit ground

“that Exide [the employer] was not ‘named in the charge’

filed with the Commission, and the Commission was not

required to enter into any conciliatory negotiations with

Exide.” 377 F.2d at p. 242. In Stebbins v. Nationwide

Mutual Ins. Co., 382 F.2d 267 (4th Cir. 1967), the com

plainant, after being informed by the Commission that it

could not take jurisdiction until after he had invoked the

aid of the Maryland State Commission, filed suit without

any further effort to invoke EEOC’s aid. This court

reached the same conclusion as in Michel, for the same

reason:

“ . . . The plaintiff could not bypass the federal agency

and apply directly to the courts for relief. Congress

established comprehensive and detailed procedures to

afford the EEOC the opportunity to attempt by ad

ministrative action to conciliate and mediate unlawful

employment practices with a view to obtaining volun

tary compliance. The plaintiff must, therefore, seek

his administrative remedies before instituting court ac

tion against the alleged discriminator.” (Emphasis in

original). Id. at p. 268.

Choate v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., 274 F. Supp. 776 (S.D.

111. 1967), rests on essentially similar grounds: the charges

18

which the plaintiff had filed with the Commission were not

“under oath”, as required by section 706(a), and she had

therefore failed properly to invoke the conciliation proc

esses of the Commission. Hall v. Werthan Bag Corpora

tion, 251 F. Supp. 184 (M.D. Tenn. 1966), describing the

jurisdictional prerequisite as “the requirement that a ‘per

son aggrieved’ exhaust his remedies before the Commis

sion”, held that persons who had not invoked their admin

istrative remedies against an employer could intervene in

a class action brought by one who had exhausted such rem

edies against the same employer, who, the Commission had

found reasonable to cause to believe, was engaged in dis

criminatory employment practices and with whom its ef

forts to conciliate had failed. The case in effect holds that

the Act does not condition the right of a person aggrieved

to seek his judicial remedy upon his resort to a futile ad

ministrative proceeding. A fortiori, the Act does not re

quire the impossible—i.e., that he force the Commission to

do what it says it cannot do.

19

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that the order below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

R obert B elto n

G abrielle A . K ir k

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J . L eV o n n e C ham bers

4051/2 E. Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

C onrad O. P earson

2031/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

J o se ph W . B is h o p , J r .

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut

A lbert R o sen th a l

435 West 116 Street

New York, New York 10027

S anford J ay R osen

500 West Baltimore Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21201

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

la

[ E m b l e m ]

E qual E m pl o y m e n t O ppo r t u n it y C om m issio n

W a sh in g t o n , D.C. 20506

A ug. 8, 1966

Ce r t ifie d M ail

R e t u r n R e c e ipt R equested

In Reply Refer to

File No. 5-12-3850

Respondent:

Seaboard Air Line

Railroad

Riebmond, Virginia

Mr. Ray Johnson

503 Boyte Street

Monroe, North Carolina 28110

Dear Mr. Johnson:

Due to the heavy workload of the Commission, it has been

impossible to undertake or to conclude conciliation efforts

in the above matter as of this date. However, the concilia

tion activities of the Commission will be undertaken and

continued.

Under the provisions of Section 706(e) of Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Commission must notify you

of your right to bring an action in Federal District Court

within a limited time after the filing of a complaint.

This is to advise yon that you may within thirty days of

the receipt of this letter, institute a civil action in the

Letter dated August 8 , 1966 from Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission

2a

appropriate Federal District Court. If you are unable

to retain an attorney, the Federal Court is authorized in

its discretion, to appoint an attorney to represent you and

to authorize the commencement of the suit without payment

of fees, costs or security. If you decide to institute suit

and find you need such assistance, you may take this letter,

along with the enclosed Commission determination of rea

sonable cause to believe Title VII has been violated, to

the Clerk of the Federal District Court nearest to the place

where the alleged discrimination occurred, and to request

that a Federal District Judge appoint counsel to represent

you.

Please feel free to contact the Commission if you have any

questions about this matter.

Very truly yours,

/ s / K e n n e t h F. H olbert

Kenneth F. Holbert

Acting Director of Compliance

Letter dated August 8, 1966 from Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission

Enclosure

3a

[ E m b l e m ]

E qual E m pl o y m e n t O ppo r t u n it y C o m m issio n

W a sh in g t o n , D.C. 20506

Case No. 5-12-3850

Ray Johnson

Charging Party

D ecision by Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission

vs.

Seaboard Air Line Railroad

Richmond, Virginia

Respondent

Date of Filing: January 14, 1966

Date of service of charge: March 3, 1966

D ec isio n

S u m m ary of C harges

The Charging Party, a Negro, alleges discrimination on

the basis of race in that he was discharged for filing com

plaints with various federal agencies protesting the dis

criminatory treatment given him as a porter in the Re

spondent Company’s employ.

S um m a ry oe I nvestigation

The investigation establishes that the Charging Party had

been in the Respondent’s employ as a porter from 1940 to

1965 when he was dismissed by the Respondent allegedly

because of a misdemeanor conviction. The misdemeanor

was probably that of drunk and disorderly conduct, al-

4a

Decision by Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

though the record is not clear on this. It occurred when

the Charging Party was off duty and not on Company

property. The conviction did not occasion any loss of

time by the Charging Party from his job.

The record of investigation shows that prior to being

dismissed, the Charging Party had sent letters of pro

test to the President’s Committee on Equal Employment,

the National Railroad Adjustment Board and the United

States Attorney G-eneral on the issue of racial discrimina

tion by the Respondent against the Negro train porters.

In those letters, he alleged that Negro train porters are

excluded from the collective bargaining unit for brakemen,

that they are required to work longer than their white

counterparts and that they enjoy fewer fringe benefits

than they should.

The reasons for the dismissal given by the officials of the

Respondent Company were that the “best interest of the

Company would be served” thereby. The Respondent fur

ther justified its action to the investigator citing a prior

incident of a similar sort. The record shows that this

prior incident had occurred some 11 years before.

When questioned as to the company practices and regula

tions used to discipline white employees for behavior

similar to that of the Charging Party, the Superintendent

of the Georgia Division of the Respondent firm remained

silent, indicating that such records w’ere kept in the Rich

mond office and were not available for inspection. The

investigator was similarly unable to gain any information

on the ethics or conduct standards used for Seaboard

employees generally. The copy of the collective bargaining

agreement submitted in the Record did not contain any

section pertaining to conduct, either on or off the job.

5a

Decision by Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

D ec isio n

There is reasonable cause to believe that the Respondent

violated Title YII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in dis

missing the Charging Party from its employ.

For the Commission:

/ s / M arie D. W ilso n

Marie D. Wilson

Secretary

July 18, 1966

Date

6a

[ E m b l e m ]

E qual E m plo y m en t O ppo r t u n it y C om m issio n

W a sh in g t o n , D.C. 20506

A ug . 8, 1966

In Reply Refer to

File No. 5-12-3850

Respondent:

Seaboard Air Line Railroad

Richmond, Virginia

Mr. Ray Johnson

503 Boyte Street

Monroe, North Carolina 28110

Dear Mr. Johnson:

The Commission has investigated your charge of employ

ment discrimination and has found reasonable cause to

believe that an unlawful employment practice within the

meaning of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has

been commited. The Commission will attempt to eliminate

this practice by conciliation as provided in Title VII. You

will be kept informed of the progress of conciliation efforts.

Very truly yours,

/ s / K e n n e t h F. H olbert

Kenneth F. Holbert

Acting Director of Compliance

Letter dated August 8 , 1966 from Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission

7a

IN T H E

U n it e d S tates D istr ic t C ourt

for THE

W estern D istr ic t of N o rth Carolina

C h arlotte D iv isio n

Civil Action No. 2171

Filed September 7, 1966

Complaint

R ay J o h n s o n ,

v .

Plaintiff,

S eaboard A ir L in e R ailroad Co m pa n y , a c o rp o ra tio n ,

Defendant.

C o m pla in t

I

This is a proceeding for a permanent injunction restrain

ing the defendant from maintaining a policy, practice,

custom and usage of withholding, denying or attempting

to withhold or deny and depriving or attempting to deprive

or otherwise interfering with the rights of the plaintiff and

others similarly situated to equal employment because of

race or color.

II

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U. S. C. §1343. This is a suit in equity authorized and in

8a

stituted pursuant to Title VII of the Civil Eights Act of

1964, 42 U. S. C. §§2000e et seq. Jurisdiction is invoked to

secure protection of and to redress deprivation of rights

secured by Title VII of the Civil Eights Act of 1964,

42 U. S. C. §2000e, providing for injunctive and other

relief against racial discrimination in employment.

III

Plaintiff brings this action on his own behalf and on

behalf of others similarly situated pursuant to Ernie

23(a)(3) of the Federal Eules of Civil Procedure. There

are common questions of law and fact affecting the rights

of other Negroes seeking equal employment opportunities

without discrimination on the ground of race or color who

are so numerous as to make it impracticable to bring them

all before this Court. A common relief is sought for each

member of the class and the plaintiff adequately represents

the interests of the class.

IV

The plaintiff, Eay Johnson, is a Negro citizen of the

United States and the State of North Carolina, residing in

Union County, North Carolina. The plaintiff is a former

employee of defendant, having worked for the defendant

from July 1940 until he was discriminatorily discharged in

December 1965.

V

The defendant, Seaboard Air Line Eailroad Company,

is a Virginia corporation, domesticated pursuant to the

laws of the State of North Carolina, with power to sue and

to be sued in its corporate name. The defendant is a rail

road company, engaged in the business of transporting

passengers and goods for hire in interstate commerce, in

Complaint

9a

eluding the State of North Carolina and Mecklenburg and

Anson Counties, North Carolina,

VI

The defendant is an employer engaged in an industry

which affects commerce and employs more than one hun

dred (100) employees.

VII

The defendant has discriminated and is presently dis

criminating against plaintiff and other Negro employees

and members of plaintiff’s class with respect to the terms,

wages, conditions, privileges, advantages and benefits of

employment with defendant, to wit:

A. Negro employees are hired primarily for and re

stricted to the job classification of train porter and are

paid lower wages and denied privileges and benefits of

employment given to white employees performing the same

or similar jobs.

B. Defendant maintains spearate lines of seniority for

Negro and white employees and denies Negro employees

the opportunity of advancement to higher paying positions

and conditions of employment, the design, intent, purpose

and effect being to continue and preserve the defendant’s

long standing policy, practice, custom and usage of limiting

the employment and promotional opportunities of Negro

employees of the defendant because of race or color.

C. Defendant maintains separate facilities and condi

tions for its Negro and white employees, the design, pur

pose and effect being to maintain and perpetuate the sep

arate job opportunities, conditions and provileges of the

employees on the basis of race and color.

Complaint

10a

D. Prior to and since the effective date of Title VII of

the Civil Eights Act of 1984, 42 U. S. C. §§2000e et seq.,

the plaintiff has protested the racially discriminatory em

ployment practices of the defendant and sought to obtain

better working conditions and terms of employment for

himself and other Negro employees of the defendant, but

without avail. Because plaintiff had protested defendant’s

discriminatory employment practices and solely to dis

courage plaintiff and other Negro employees from seeking

to exercise their rights under this Act, the defendant dis

charged the plaintiff as an employee, all in violation of

plaintiff’s rights under the Act.

VIII

Defendant’s discrimination against the plaintiff and

others of the class with respect to compensation, terms,

conditions, advantages, privileges and benefits of employ

ment and with respect to plaintiff’s dismissal because he

had opposed defendant’s discriminatory employment prac

tices and sought better conditions and terms of employ

ment were intended to deny and had the effect of denying

the plaintiff and others of the class equal employment op

portunities and to otherwise adversely affect their status

as employees solely because of their race and color.

IX

Neither the State of North Carolina nor any other state,

county or city agency having jurisdiction of the defendant

has a law prohibiting the unlawful practices alleged herein.

On January 14, 1966, the plaintiff filed a complaint with

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission alleging

denial by defendant of his rights under Title VII of the

Complaint

11a

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. §§2000e et seq. On

August 8, 1966, the Commission found reasonable cause

to believe that violations of the Act had occurred by de

fendant and advised the plaintiff that the defendant’s com

pliance with Title VII had not been accomplished within

the maximum period allowed to the Commission by Title

VII and that plaintiff was entitled to maintain civil action

for relief in the United States District Court.

X

Plaintiff has no plain, adequate or complete remedy at

law to redress the wrongs alleged, and this suit for in

junctive relief is his only means of securing adequate relief.

Plaintiff and the class he represents are now suffering and

will continue to suffer irreparable injuries from defendant’s

policy, practice, custom and usage as set forth herein until

and unless enjoined by the Court.

W h e r e fo r e , plaintiff respectfully prays this Court ad

vance this case on the docket, order a speedy hearing at

the earliest practicable date, cause this case to be in every

way expedited, and upon such hearing to:

1. Grant plaintiff and the class he represents injunctive

relief, permanently enjoining defendant, Seaboard Air

Line Railroad Company, its agents, successors, employees,

attorneys, and those acting in concert or participation with

them or at their direction from continuing or maintaining

any policy, practice, custom and usage of denying, abridg

ing, withholding, conditioning, limiting or otherwise inter

fering, with the rights of plaintiff and others of his class

secured to them by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U. S, C. §§2000e et seq.

Complaint

12a

2. Grant plaintiff injunctive relief ordering his rein

statement in employment with defendant and awarding

plaintiff back pay.

3. Allow plaintiff his costs herein, including reasonable

attorney fees and such other additional relief as may appear

to the Court to be equitable and just.

/ s / J. L eV o n n e C h a m bers

C onrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J. L eV o n n e C h a m bers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

J ack Greenberg

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff

Complaint

13a

(Filed October 3, 1966)

Defendant moves the court to dismiss the action because:

1. The complaint fails to state a cause of action upon

which relief can be granted in a class action, in that it is

not a class action within the meaning and requirements of

Rule 23 of the Rules of Civil Procedure.

2. The court lacks jurisdiction over the subject matter

alleged in the complaint, in that it does not set forth a

claim upon which relief can be granted by the court for

that plaintiff’s alleged complaint against defendant is a

matter within the exclusive primary jurisdiction of the

National Railroad Adjustment Board under the Railway

Labor Act, 45 U.S.C. 151 et seq.

3. The court lacks jurisdiction over the subject matter

alleged in the complaint, in that plaintiff did not file timely

his charge as prescribed by 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq., pre

requisite to the institution of this action and jurisdiction

of this court.

Motion to Dismiss

/s / John S. Cansler

J o h n S . Ca n sler

Of counsel for Defendant

910 N.C.N.B. Building

Charlotte, N. C. 28202

/s / Thomas Ashe Locbart

T hom as A s h e L ockhart

Of counsel for Defendant

910 N.C.N.B. Building

Charlotte, N. C. 28202

14a

(Filed September 19, 1967)

Defendant moves the court to amend its Motion to

dismiss the action, filed herein on October 3, 1966, by

adding thereto the following additional and separate

grounds:

4. The complaint is barred for the reason that, as the

provisions of Sections 706(a) and 706(e) of Title VII

of the 1964 Civil Rights Act provide for and require the

exercise of “informal methods of conference, conciliation,

and persuasion” by the Commission with respect to a

charge filed by a person claiming to be aggrieved with

the Commission, which methods and procedures are a

prerequisite and condition precedent to the institution of

a civil action thereunder, no such methods and proce

dures were followed either within the period of time pro

vided therefor or at any time with respect to either the

charge filed by the plaintiff with the Commission or the

subject matter of the complaint in this action.

5. The complaint fails to name and join a necessary

and indispensable party defendant to this action, the

International Association of Railway Employees, here

inafter referred to as the “Union”, in that,

(a) the Union has a substantial interest in the subject

matter of the complaint;

(b) the Union would be directly and vitally affected by

any decree on the merits of this action;

(c) this action could not be completely determined with

out the presence of the Union as a party because

the complaint seeks to annul, hinder, abridge, inter-

Motion to Amend Motion to Dismiss

15a

fere with or affect the contract between this defen

dant and the Union entered into April 1, 1954, which

as thereafter modified and amended is hereto at

tached and made a part hereof as Exhibit “A”,

which contract between the defendant and the Union

was arrived at after collective bargaining with re

spect to matters of the compensation, terms, condi

tions, advantages, privileges and benefits of em

ployment of the plaintiff, a former employee of the

defendant and a member of such Union;

(d) the maintenance of this action without the presence

of the Union would leave the action in such condi

tion that its final determination would be incon

sistent with equity.

/ s / J o h n S . Cansijer,

J o h n S. C a n sler

/ s / T hom as A s h e L ockhart

T h o m a s A s h e L ockhart

/ s / W . T hom as R ay

W . T h o m a s R ay

Attorneys for Defendant

Seaboard Air Line Railroad Company

Motion to Amend Motion to Dismiss

1 6 a

Order Granting Substitution, etc.

This cause coming on to be heard before the undersigned

upon motion of plaintiff for leave to substitute the Sea

board Coast Line Railroad Company as party-defendant

in the above entitled proceeding, pursuant to Rule 25 of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and it appearing to the

Court that there is good cause therefor;

I t is , t h e r e fo r e , Ordered and D ecreed that the Seaboard

Coast Line Railroad Company be substituted as party-

defendant in lieu of the Seaboard Air Line Railroad Com

pany.

I t is f u r t h e r Ordered t h a t a l l p le a d in g s h e r e in be

a m e n d e d to c o n fo rm to th e s u b s t i tu t io n o f th e p a r ty - d e f e n d

a n t.

T his...... day of October, 1967.

Judge, United States District Court

Approved as to form:

Counsel for Defendant

Seaboard Coast Line

Railroad Company

17a

Letter dated November 3 , 1967

November 3, 1967

The Honorable Woodrow Wilson Jones, Judge

United States District Court for the

Western District of North Carolina

Rutherfordton, North Carolina

Re: Lee v. Observer Transportation

Company, Charlotte Division

Civil No. 2145

Johnson v. Seaboard Coast

line Railroad Company

Charlotte Division

Civil No. 2171

Black v. Central Motor Lines

Charlotte Division

Civil No. 2152

Brown v. Gaston Dyeing

Machine Company, Charlotte

Division, Civil No. 2136

Walker v. Charlotte Freight

Carriers, Inc., Charlotte

Division, Civil No. 2167

Dear Judge Jones:

I am enclosing a copy of the recent Orders entered by

Judge Gordon in Robinson v. P. Lorillard and Lea v. Cone

Mills in connection with the pending motions in the above

1 8 a

cases. I am also enclosing a copy of the Court’s letter to

counsel in connection with the two cases.

By copy of this letter I am also sending copies of the

enclosed Orders and letter to opposing counsel.

Sincerely yours,

Letter Dated November 3, 1967

J. LeVonne Chambers

19a

U n ited S tates D istr ic t C ourt

M iddle D ist r ic t of N o rth Carolina

Eugene A. Gordon

U. S. District Judge

Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27102

October 25, 1967

Mr. Thornton H. Brooks, Attorney

440 West Market Street

Greensboro, North Carolina 27402

Mr. Larry Thomas Black, Attorney

Suite 323 Law Building

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Mr. J. LeVonne Chambers, Attorney

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Mr. C. O. Pearson, Attorney

2031/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

Mr. Sammie Chess, Jr., Attorney

622 East Washington Drive

High Point, North Carolina 27260

Be: No. C-141-G-66

Dorothy P. Robinson, et al v. P.

Lorillard Co., et al

Shirley Lea, et al v. Cone Mills

Memorandum o f D ecision

Gentlemen:

For convenience, I am taking the liberty of briefly giv

ing my views on the respective motions to dismiss filed in

20a

the above cases in this Single communication. An inter

vening term of court has prevented earlier consideration

of the motions.

Michel v. South Carolina State Employment Service, 4

Cir., 377 F. 2d 239 (1967) is certainly factually distinguish

able from the subject cases. There the plaintiff had not

filed a charge with the Commission against Eside. Judge

Boreman states:

“ [1] It seems clear from the language of the statute

that a civil action could be brought against the re

spondent named in the charge filed with the Commis

sion only after conciliation efforts had failed, or, in

any event, after opportunity had been afforded the

Commission to make such efforts.”

It seems clear that in the cases before this Court oppor

tunity was afforded the Commission to initiate conciliation

efforts.

Also, there is merit to the contention that actual affirm

ative effort on the part of the Commission to gain compli

ance is not necessary by reason of the language in § 706(e)

as follows: “ , the Commission has been unable to

obtain voluntary compliance with this title.” Apparently,

such was the court’s opinion in Moody v. Albemarle Paper

Company, 271 F. Supp. 27 (1967).

With much respect for the opinions expressed by coun

sel for each party, I must deny the motion to dismiss in

both cases. Counsel for the plaintiffs will accordingly

Memorandum of Decision

2 1 a

forthwith prepare and present to me an order for signa

ture denying the motions to dismiss.

With kindest regards and best wishes, I am

Sincerely yours,

EAG

Eugene A. Gordon

United States District Judge

EAG/nat

Memorandum of Decision

IN' THE

U n it e d S tates D istr ic t C ourt

FOR THE

M iddle D istrict of N o rth Carolina

Greensboro D iv isio n

R E C E I V E D

Nov 2 1967

C iv il A ction

No. C-176-D-66

Order Denying Motion to Dismiss

S h ir l e y L ea, et al.,

v.

Plaintiffs,

C o n e M il l s C orporation ,

a corporation,

Defendant.

ORDER

This cause came on to be heard before the undersigned

upon Motion of defendant to dismiss on the ground that

the Court lacks jurisdiction over the action in that the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission did not en

deavor to settle or eliminate the alleged unlawful employ

ment practices by conference, conciliation and persuasion

prior to plaintiffs’ constitution of this action, and it appear

ing to the Court upon the pleadings, exhibits briefs and

23a

Order Denying Motion to Dismiss

arguments of counsel for both parties that the Motion

should he denied;

I t, is , th e r e fo r e , ordered, adjudged and decreed that the

Motion to dismiss be and the same is hereby denied.

This 1 day of November, 1967.

/s / E u g e n e A. G ordon

Judge, United States District Court

A True Copy

Teste:

Herman Amasa Smith, Clerk

By: A lbert L. V a u g h n

Deputy Clerk

24a

Bf THE

U n ited S tates D istr ic t C ourt

for THE

M iddle D istr ic t of N o rth C arolina

Greensboro D iv isio n

R E C E I V E D

Nov 2 1967

C iv il A ction

No. C-141-G-66

Order Denying Motions to Dismiss

D orothy P. R o bin so n , et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

P. L orillard C o m pa n y , et al.,

Defendants.

ORDER

This cause came on to be heard before the undersigned

upon Motions of defendants, P. Lorillard Company, To

bacco Workers International Union, AFL-CIO and Tobacco

Workers International Union, AFL-CIO, Local No. 317,

to dismiss the action as to alleged discrimination by de

fendants on the basis of sex on the ground that the Court

lacks jurisdiction since the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission did not attempt to settle the matter by con

ferences, conciliation and persuasion prior to the institu-

25a

Order Denying Motions to Dismiss

tion of this action, and it appearing to the Court upon

the pleadings, exhibits, briefs and arguments of counsel

that the Motion should be denied;

I t, is , th er efo r e , ordered, adjudged and decreed that

the Motions to dismiss be and they are hereby denied.

This 1 day of November, 1967.

/ s / E u g en e A. G ordon

Judge, United States District Court

A True Copy

Teste:

Herman Amasa Smith, Clerk

By: A lbert L. V a u g h n

Deputy Clerk

26a

F I L E D

J an 25 1968

ORDER

T h is cause coming on to be heard before the undersigned,

United States District Judge, and being heard upon defen

dant’s Motion to Dismiss the action for lack of jurisdic

tion on the grounds that prior to the institution of the

action there was no attempt or endeavor made by the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to eliminate

any such alleged unlawful employment practice by in

formal methods of conference, conciliation, and persuasion

as required by the Civil Rights Act of 1964; and, after

considering the pleadings, affidavits, admissions, briefs and

oral argument of counsel, the Court is of the opinion that

resort to the remedy of conciliation is a jurisdictional pre

requisite to the right to file and maintain a civil action

under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and that since there

was no such effort made, the Motion should be allowed,

I t is , t h e r e fo r e , ordered t h a t th e a c tio n be a n d th e

sam e is h e re b y d ism isse d .

This the 25th day of January, 1968.

/ s / W oodrow W . J ones

United States District Judge

A True Copy

Teste :

Thos. E. Rhodes, Clerk

By: Gl e n n G am m

Deputy Clerk

Order Granting Motion to Dismiss

27a

(Filed January 25,1968)

The plaintiff brought this action on his own behalf and

on behalf of other negro citizens similarly situated, under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.A. Sec

tion 2000e-5, against the defendant alleging racial discrimi

nation in terms and conditions of employment against him

self and the class which he claims to represent, and charging

that he was discriminatorily discharged from employment.

The defendant has moved to dismiss the action for lack of

jurisdiction on the grounds that prior to the institution of

the action there was no attempt or endeavor made by the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to eliminate

any such alleged unlawful employment practice by informal

methods of conference, conciliation, and persuasion as re

quired by the Act.

The issue before this Court is whether it is a prerequisite

to the institution and maintenance of a civil action under

the Civil Rights Act that there be compliance with the

direction of 42 U.S.C.A. Section 2000e-5(a) which reads in

part as follows:

“Whenever it is charged in writing under oath by a per

son claiming to be aggrieved, . . . that the employer . . . has

engaged in unlawful employment practice, the Commission

shall furnish such employer . . . with a copy of such charge

and shall make an investigation of such charge . . . If the

Commission shall determine after such investigation, that

there is reasonable cause to believe that the charge is true,

the Commission shall endeavor to eliminate any such alleged

unlawful employment practice by informal methods of con

ference, conciliation, and persuasion . . . ”

The facts necessary for this decision are not in dispute

and may be briefly summarized. The plaintiff in this action

Memorandum of D ecision

28a

filed his complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission on January 14, 1966, alleging a violation of the

Act, and by order dated July 18, 1966, the Commission

found “There is reasonable cause to believe that the re

spondent violated Title VII of the Civil Eights Act of 1964

in dismissing the charging party from its employ.” That

by letter dated August 8, 1966, the Commission advised the

defendant in pertinent parts, as follows:

“This will inform you that, after investigation, the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission has determined that

there is reasonable cause to believe that you have engaged

in an unlawful employment practice within the meaning of

Section 703 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. A copy of the

Commission’s decision is enclosed.

“A Conciliator appointed by the Commission will contact

you soon to discuss means of correcting this discrimination

and avoiding it in the future.

“ . . . Since the charges in this case were filed in the early

phases of the administration of Title YII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, the Commission has been unable to conduct a

conciliation during the 60-day period provided in Section

706. The Commission is, accordingly, obligated to advise

the charging party of his right to bring a civil action pur

suant to Section 706(e).

“Nevertheless, we believe it may serve the purposes of

the law and your interests to meet with our Conciliator to

see if a just settlement can be agreed upon and a law suit

avoided.

“We are hopeful that you ean cooperate with us in

achieving the objectives of the Civil Rights Act and that we

will be able to resolve the matter quickly and satisfactorily

to all concerned.”

Memorandum of Decision

That no Conciliator from the Commission called npon

the defendant and no effort at any time has been made by

anyone to conciliate this matter. Upon a hearing on the

Motion, the Court inquired of plaintiff’s counsel whether

the Court could assist in a conciliation of the matter and

was advised that no such assistance was desired.

42 U.S.C.A. Section 2000e-5(e) provides in part as fol

lows:

“If within thirty days after the charge is filed with the

Commission or within thirty days after the expiration of

any period of reference under sub-section (c) of this section

(except that in either case such period may be extended to

not more than sixty days upon a determination by the Com

mission that further efforts to seek voluntary compliance

are warranted), the Commission has been unable to obtain

voluntary compliance with this subchapter, the Commission

shall so notify the person aggrieved and a civil action may

within thirty days thereafter, be brought against the re

spondent named in the charge (1) by the person claiming

to be aggrieved . . .”

Several District Courts have recently reached different

conclusions about jurisdictional prerequisites for institu

tion of an action under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Eights

Act.

The cases of Quarles v< Phillip Morris, Inc., 271 F. Supp.

842, E.D. Va. April 11, 1967; Evenson v. Northwest Air

lines, Inc., 268 F. Supp. 29, E.D. Va., March 17, 1967, and

Moody v. Albermarle Paper Cb-, 271 F. Supp. 27, E.D.N.C.

July 5, 1967, seem to hold that an attempt or endeavor at

conciliation by the Commission is not a prerequisite to the

institution of a civil action by an aggrieved party. How

ever, the factual situation in these cases is somewhat dif

ferent from the case at bar. In the Quarles case the Com

29a

Memorandum of Decision

30a

mission stated it had been unable to undertake “extensive”

conciliation and it would make additional efforts. In the

Evenson case the Commission advised the aggrieved party

that conciliation efforts had failed, and in the Moody case

the Commission reported that voluntary compliance within

sixty days from receipt of the complaint by the Commission

had not been effected. In the case at bar the Commission

reports that no effort, endeavor or attempt was made to

eliminate any such alleged unlawful employment practice

by informal methods of conference, conciliation, and per

suasion.

The words of the statute are clear that “if the Commis

sion shall determine . . . there is reasonable cause to believe

that the charge is true, the Commission shall endeavor to

eliminate any such alleged unlawful employment practice

by informal methods of conference, conciliation, and per

suasion. Is there any doubt the Congress, the legislative

body of our government, charged the Commission which it

created, with the duty to endeavor to eliminate the alleged

wrongful practice by informal methods of conciliation and

persuasion! After this effort is made by the Commission

it then becomes its duty to report its failure to the aggrieved

party who may then institute action in court. The language

of the Act clearly provides that if within sixty days after

the charge is filed, “the Commission has been unable to ob

tain voluntary compliance . . . the Commission shall so

notify the person aggrieved and a civil action may . . . be

brought against the respondent named in the charge . . . bv

the person claiming to be aggrieved . . . ”

The legislative branch of our government in passing this

measure had some purpose in the use of this language.

There is no doubt the Congress intended this procedure be

followed in these cases. Did it mean that the court action

Memorandum of Decision

31a

could not be maintained before this procedure was com

pleted!

This Court has done considerable research on this ques

tion and has had the benefit of exhaustive briefs from the

attorneys on both sides and has reached the conclusion that

Congress intended that an endeavor at conciliation be a

prerequisite to the institution of a civil action under this

Act.