Aikens v. California Brief Amicus Curiae of the Committee of Psychiatrists for Evaluation of the Death Penalty

Public Court Documents

August 26, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Aikens v. California Brief Amicus Curiae of the Committee of Psychiatrists for Evaluation of the Death Penalty, 1971. 6e8d610e-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/eb36893e-a6b7-4338-a93f-16164ee8ebfa/aikens-v-california-brief-amicus-curiae-of-the-committee-of-psychiatrists-for-evaluation-of-the-death-penalty. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

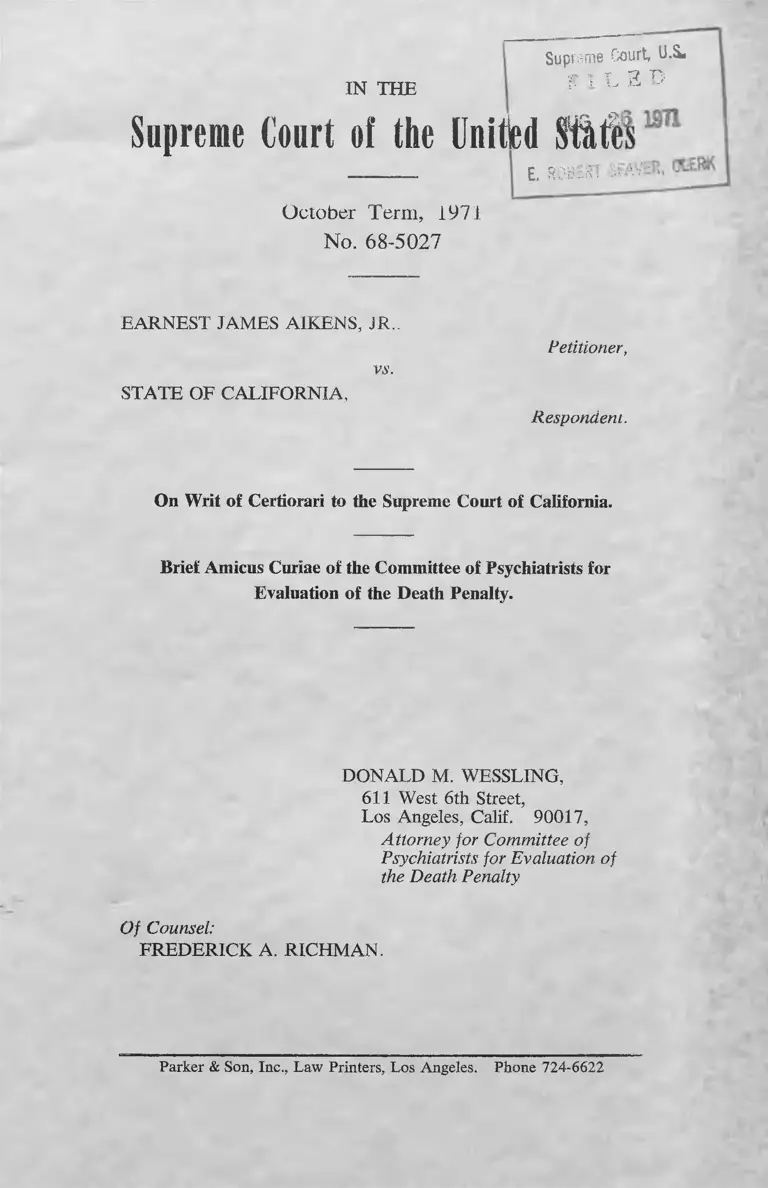

IN THE

Suprem e Court, U.S.

F 3 L E D

Supreme Court of the UnitSed S M

E. ROBERT SEAVL

October Term, 1971

No. 68-5027

EARNEST JAMES ATHENS, JR..

vs.

STATE OF CALIFORNIA,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

On Writ o£ Certiorari to the Supreme Court of California.

Brief Amicus Curiae of the Committee of Psychiatrists for

Evaluation of the Death Penalty.

DONALD M. WESSLING,

611 West 6th Street,

Los Angeles, Calif. 90017,

Attorney for Committee of

Psychiatrists for Evaluation of

the Death Penalty

Of Counsel:

FREDERICK A. RICHMAN,

Parker & Son, Inc., Law Printers, Los Angeles. Phone 724-6622

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

Statement of Interest of the Amici..... ...................... 1

Argument .......................... ................... ......... .......... 2

1.

Capital Punishment Constitutes Cruel and Un

usual Punishment Because of the Psychologi

cal Torture Which It Inflicts ............................ 2

I I .

Capital Punishment Serves No Legitimate State

Purpose Which Could Not Be Achieved by

Other Means .......................... ................. -........ 6

Conclusion ........ ................ ................. ................ .... 8

Appendix. Committee of Psychiatrists for Evalu

ation of the Death Penalty ___ ______ App. p. 1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases Page

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ........... 6

Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 889 (1963) .. 6

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) _____ 6

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960) ........... . 6

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963) ______ 6

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) ............ 2

Miscellaneous

Duffy, C., 88 Men and 2 Women (1962) .......... 3

Duffy, C., The San Quentin Story (1950) .............. 3

Gottlieb, G., Capital Punishment (Center for the

Study of Democratic Institutions 1967) _____ 3

Kron, Dr. Yves J., “The Citizen and Capital Pun

ishment”, statement printed by the New York

Committee to Abolish Capital Punishment __ __ 7

Sellin, Prof. Thorsten, The Death Penalty (1959).. 7

Textbooks

Bedau, H., “The Courts, the Constitution, and Cap

ital Punishment,” 1968 Utah L. Rev. (1968),

pp. 201, 204 .... .......................... ........................ 3

Bedau, H., ed., The Death Penalty in America

(1964), 588-332 ................... .................. -............ 6

Bluestone & McGahee, “Reaction to Extreme

Stress: Impending Death by Execution”, 119 Am.

J. of Psychiatry (Nov. 1962), p. 393 ................ 3

Cohen, “Psychiatrists Look at Capital Punish

ment”, 29 Psychiatric Digest (1968), p. 45 ........ 7

Page

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and

Administration of Justice, Report (The Chal

lenge of Crime in a Free Society) (1967), p.

143 ..... ................... .............................................. 6

United Nations Department of Economic and So

cial Affairs, Capital Punishment (ST/SOA/SD/

9-10) (1968), p. 123 ....................................... 6

West, L. J., “A Psychiatrist Looks at the Death

Penalty”, paper presented at the 122nd Annual

Meeting of the American Psychiatric Associa

tion, May 11, 1966 ___________ ___________ 3

Ziferstein, Center Magazine (Jan. 1968), “Crime

and Punishment,” p. 84 ............................ — ..... 4

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 68-5027

EARNEST JAMES AIKENS, JR.,

Vi.

STATE OF CALIFORNIA,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of California.

Brief Amicus Curiae of the Committee of Psychiatrists for

Evaluation of the Death Penalty.

Statement of Interest of the Amicus.

The Committee of Psychiatrists for Evaluation of the

Death Penalty filing this brief amicus curiae is com

posed of practicing psychiatrists who also have major

responsibility for developing new knowledge about hu

man nature and for educating others in the most ad

vanced degrees of psychiatric thought.1 Many of these

psychiatrists have had direct experience with men sen

tenced to death. Because psychiatrists are regularly

called upon to testify in cases involving the death penalty

and to certify the sanity of men sentenced to death, they

are in a position to bring before this Court some views

of the nature and effect of the death sentence which

might not be stressed by other parties.

Consent of the parties for the filing of this brief

amicus curiae has been sought and obtained. Copies

of the parties’ letters will be submitted to the Clerk with

this brief.

1See Appendix for list of psychiatrists composing the Com

mittee.

— 2— -

A R G U M EN T.

I.

Capital Punishment Constitutes Cruel and Unusual

Punishment Because of the Psychological Torture

Which It Inflicts.

In Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 100-01 (1958), this

Court held that the crux of the Eighth Amendment is its

prohibition of “inhuman treatment” and its incorpora

tion of a maturing society’s “evolving standards of de

cency.” The Court recognized that the protection

of the Amendment extends far beyond primitive

tortures; it prohibits any punishment which violates

“the principle of civilized treatment.” Id. at 99.

In Trop the Court ruled that denationalization was a

cruel and unusual punishment for desertion. In so rul

ing, the Court based its finding of cruelty largely upon

the extreme psychological pain which such a punish

ment inflicted. The plurality opinion of the Chief Jus

tice stated that denationalization was offensive to the

cardinal principles of the Constitution because it “sub

jects the individual to a fate of ever-increasing fear

and distress.” Id. at 102. The concurring opinion of

Mr. Justice Brennan, which was necessary for a ma

jority, stated that “ (t)he uncertainty, and the conse

quent psychological hurt, which must accompany one

who becomes an outcast in his own land must be reck

oned a substantial factor in the ultimate judgment.”

Id. at 111.

In the psychological pain it inflicts upon men waiting

to be executed, capital punishment far exceeds dena

tionalization as inhuman treatment. Indeed, the psy

chological effects of the death sentence are really an

additional punishment that is cruel and inhumane in

itself. It is an important aspect of capital punishment

—3—

that a man sentenced to death does not simply lose

his life. He is also subjected, during his last months or

years, to a psychological punishment perhaps worse

than his execution.

Psychiatrists, wardens and others who have had di

rect contact with condemned men have documented the

brutal mental deterioration of men on death row." Dr.

Louis J. West has noted that

“A good many of these doomed men end up in

the hands of the psychiatrist. The strain of exist

ence on Death Row is very likely to produce be

havioral aberrations ranging from malingering to

acute psychotic breaks.” L. J. West, “A Psychia

trist Looks at the Death Penalty,” paper presented

at the 122nd Annual Meeting of the American

Psychiatric Association, May 11, 1966.

Those prisoners who escape psychosis frequently ex

perience other reactions to the stress of impending

death: insomnia, withdrawal, depression, paranoia,

obsessive rumination, anxiety and delusions.3 The

damage is increased by the steadily lengthening time

which prisoners spend on death row. The average time

spent under death sentence was 16 months as of 1960;

as of 1965 it was nearly four years,4

2For case studies, see C. Duffy, The San Quentin Story

(1950); 88 Men and 2 Women (1962); G. Gottlieb, Capital

Punishment (Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions

1967).

3For a description of actual cases involving these reactions,

see Bluestone and McGahee, “Reaction to Extreme Stress: Im

pending Death by Execution,” 119 Am. J. of Psychiatry 393

(Nov. 1962)

4H. Bedau, “The Courts, the Constitution, and Capital Punish

ment,” 1968 Utah L. Rev. 201, 224. Bedau notes that there

are prisoners who have been on death row for more than 14

(This footnote is continued on next page)

4

This psychological anguish is inherent in the idea of

imprisoning men to await certain death. Hence, it can

not be diminished even though more “efficient” or

“humane” ways of killing are developed. Dr. Isidore

Ziferstein has concluded:

“In less ‘civilized’ societies the slow torture of

the condemned man was an important part of the

execution. Procedures like crucifixion were public,

and they inflicted prolonged torture. They were

rationalized by the magical assumption that the

condemned man’s suffering might purify his soul

and might lead to repentance before he finally

died. These sadistic spectacles were also rational

ized as socially valuable deterrents.

“Modern techniques of execution have aimed at

minimizing the physical pain of dying (although

we do not really know how much pain is ex

perienced in electrocution or execution by gas).

But these modern techniques have retained to the

fullest the exquisite psychological suffering of the

condemned man.” Ziferstein, “Crime and Punish

ment,” Center Magazine 84 (January 1968) (em

phasis added).

The suffering of the condemned man is aggravated

by his knowledge that the death penalty is rarely ap-

years, and concludes: “there is every reason to expect that

during the next decade, unless the death penalty is abolished

or radical procedural reforms are introduced, it will be common

place for persons to spend between five and ten years under

death sentence before final disposition of their cases.” Id. The

possibility that the average length of time on death row may have

been increased in part because of the condemned prisoners’ own

appeals does not justify the increased psychological anguish

involved. It would be strange if a prisoner were held “estopped”

to challenge his punishment as cruel and unusual because he

had exercised fully his rights of review.

- 5 -

plied, that the wealthy and influential are relatively

safe from it, and that many states and nations have

already abolished it. Accidents of circumstance, time,

and geography thus appear, almost frivolously, to

be determinants in the loss of his life. The irrevoca

bility of that punishment means that no subsequent

change in circumstance or law can possibly be of bene

fit to him, so that even the thin sustenance of hope is

lost.

Furthermore, the person awaiting legal execution to

day lives in a time when the sacred quality and value

of human life have been increasingly recognized and

protected by law. The condemned man awaits exter

mination by the state under conditions in which no

individual would be morally or legally justified in taking

a life. Under modern conventions even an enemy soldier

in combat, once captured and subdued, may not be

killed. The moral and legal precept that no man has

the right to kill a helpless captive is now sufficiently

universal that the condemned prisoner suffers the addi

tional anguish of realizing that the state, coldly and

impersonally, will commit against him an act denied to

any individual, regardless of passion or provocation.

These psychological cruelties inherently accompany

the institution of capital punishment. In and of itself,

the taking of life may constitute the “inhuman treat

ment” which the Eighth Amendment prohibits. But

coupled with the extreme psychological suffering which

precedes it, extending over an average of four years,

capital punishment surely violates standards of decency

and civilized treatment.

—6—■

II.

Capital Punishment Serves N o Legitimate State Purpose

Which Could N ot Be Achieved by Other M eans.

Where important consitutional rights are involved,

a state cannot justify their infringement without a show

ing of a compelling state interest. Sherbert v. Verner,

374 U.S. 398 (1963) (freedom or religion); NAACP v.

Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) (freedom of expression);

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) (right to

travel). Such a showing cannot be made where there

are other, less harsh means to achieve the state’s pur

pose. Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960). The

state must employ available, “less drastic means” where

they adequately protect the interest involved. Id. at 488.

The legitimate governmental interests in the punish

ment of criminals are (1) rehabilitation, (2) isolation,

and (3) deterrence. See Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S.

889, 891 (1963) (Goldberg, J. dissenting). Of these

interests, the first is obviously irrelevant to capital pun

ishment and the second is served equally by capital

punishment or life imprisonment. Regarding the third

interest, not only is there no evidence that capital

punishment is an effective deterrent, but there is also a

body of psychological evidence suggesting that capital

punishment is an incentive to violence.

No study has yet shown that capital punishment

deters crime.6 One reason is that crimes are committed

for reasons other than a rational weighing of conse-

r,Scc The Death Penalty in America, 588-332 (H. Bedau,

ed. 1964); United Nations Department of Economic and Social

Affairs, Capital Punishment, (ST/SOA/SD/9-10) 123 (1968);

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration

of Justice, Report (The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society)

143 (1967).

—7

quences. To the extent criminals anticipate the conse

quences of their conduct, they do so in terms of

whether or not they will be caught. They do not com

mit crimes after deciding that, on balance, the punish

ment seems fairly light for the crime contemplated.15

Thus there is not only no statistical support for the

belief that capital punishment deters crime more ef

fectively than life imprisonment, but there is no psycho

logical reason for believing that it would so function.

Even assuming that there is an appreciable difference

to criminals between capital punishment and life im

prisonment, it is not the kind of consideration which

would determine whether a crime of violence would be

committed.

On the other hand, strong psychological reasons exist

for believing that capital punishment serves to legitimize

killing as a solution to human problems and actually to

incite certain warped mentalities to kill. Dr. West and

Professor Thorsten Sellin have described the phenom

enon of attempting suicide by committing a murder:

documented murders which have been committed by

abnormal persons out of a conscious or unconscious

desire to be put to death by society.7

6See the responses of phychiatrists to a survey on capital

punishment reported in Cohen, “Psychiatrists Look at Capital

Punishment,” 29 Psychiatry Digest 45, 49 (Feb. 1968). The

former Chief of Service of the Psychiatric Clinic at Sing Sing

Prison concluded that

“The fallacy here [in the desire for capital punishment] is

that the real murderer, in the act of killing, does not think

of the consequences. The desire for control or reassurance

comes only to the ‘average citizen’— . . .”

Statement by Dr. Yves J. Kron, “The Citizen and Capital Punish

ment” printed by the New York Committee to Abolish Capital

Punishment.

7West, supra, at 3-4; T. Sellin, The Death Penalty (1959).

8—

The existence of capital punishment, moveover, rep

resents an official sanction of violence and revenge that

cannot help but brutalize societal values. Thus, even

if it is rarely exercised, the dealth penalty provides a

model that apparently stimulates more homicides than

it deters. These considerations prompted the Board of

Trustees of the American Psychiatric Association, the

oldest continuing national medical society in the United

States, with a membership of over 17,000 psychiatrists,

to adopt the following resolution on December 12, 1969:

“Resolved that the American Psychiatric Asso

ciation, through its Board of Trustees, opposes the

death penalty and calls for its abolition. The best

available scientific and expert opinion holds it to

be anachronistic, brutalizing, ineffective and con

trary to progress in penology and forensic psychi

atry.”

The American Psychiatric Association went on to file

a brief amicus curiae before this Court in which various

illustrations were given to show how the death penalty,

far from serving as a deterrent, “. . . may actually serve as

an incitement to crime among various types of mentally

unstable potential offenders.” Brief for American Psy

chiatric Association as Amicus Curiae at 6-7, Maxwell

v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262 (1970).

Conclusion.

The extreme psychological suffering inherent in cap

ital punishment renders it cruel and unusual punishment.

The existence of alternative methods to achieve the stated

purposes of capital punishment makes it impossible to

■9—

justify in terms of legitimate governmental interests. In

fact it probably incites more homicides than it deters.

For these reasons, amicus submits that the judgment of

the Supreme Court of California should be reversed.

Dated: August 26, 1971.

Respectfully submitted,

D o n a l d M. W e s s l i n g ,

Attorney for Committee of

Psychiatrists for Evaluation

of the Death Penalty

Of Counsel:

F r e d e r i c k A. R i c h m a n .

APPEN DIX:

Committee of Psychiatrists for Evaluation

of the Death Penalty.

Louis Joylon West, M.D., Chairman

Professor and Head, Department of Psychiatry,

Center for the Health Sciences,

University of California, Los Angeles;

Medical Director,

UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute.

Ransom J. Arthur, M.D.

Captain, USN(MC);

Director, Nava) Neuropsychiatric Research Center, and

Professor of Psychiatry, University of California, San

Diego.

Edward F. Auer, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

St. Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri.

Eugene Bliss, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry

University of Utah School of Medicine

Salt Lake City, Utah.

Sanford L. Cohen, M.D.

Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

Boston University School of Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts.

Gordon H. Deckert, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Oklahoma School of Medicine,

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

Leon Eisenberg, M.D.

Professor and Head, Department of Psychiatry,

Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard

University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts;

Past President, American Orthopsychiatric Association.

Lloyd C. Elam, M.D.

President, Meharry Medical College and

Professor of Psychiatry, Meharry School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee.

Joel Elkes, M.D.

Chairman, Department of Psychiatry and

Behavorial Sciences

Johns Hopkins University Medical School

Baltimore, Maryland.

■2—

Daniel X. Freedman, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Chicago School of Medicine,

Chicago, Illinois.

Herbert S. Gaskill, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Colorado School of Medicine,

Denver, Colorado.

David A. Hamburg, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

Stanford University School of Medicine,

Stanford, California.

Donald W. Hastings, M.D.

Professor of Psychiatry,

University of Minnesota Medical School,

Minneapolis, Minnesota.

William Hausman, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Minnesota Medical School,

Minneapolis, Minnesota.

David R. Hawkins, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Virginia School of Medicine,

Charlottesville, Virginia.

Marc H. Hollender, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine,

Nashville, Tennessee.

Anthony J. Kales, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

Pennsylvania State University School of Medicine,

Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Lawrence C. Kolb, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia

University,

New York, New York.

Alan I. Levenson, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Arizona College of Medicine,

Tucson, Arizona.

William T. Lhamon, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

Cornell University Medical College,

New York, New York.

— 3

Morris A. Lipton, Ph.D,, M.D.

Professor and Head, Department of Psychiatry,

University of North Carolina School of Medicine,

Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Arnold J. Mandell, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

School of Medicine,

University of California at San Diego,

La Jolla, California.

James L. Mathis, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

Medical College of Virginia,

Richmond, Virginia.

R. Layton McCurdy, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

Medical University of South Carolina,

Charleston, South Carolina.

Roy W. Menninger, M.D.

President, The Menninger Foundation,

Topeka, Kansas.

Milton M. Miller, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Wisconsin School of Medicine,

Madison, Wisconsin.

Chester M. Pierce, M.D.

Professor of Education and Psychiatry

Harvard Graduate School of Education

Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Howard P. Rome, M.D.

Professor of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota, and

Head, Psychiatry Section, Mayo Clinic, Rochester,

Minnesota;

Past President, American Psychiatric Association.

Herbert S. Ripley, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Washington School of Medicine,

Seattle, Washington.

Albert J. Silverman, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Michigan School of Medicine,

Ann Arbor, Michigan.

4-

Alexander Simon, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of California Medical Center, San Francisco,

California;

Medical Director, Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric

Institute.

Robert L. Stubblefield, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Texas Southwestern Medical School,

Dallas Texas.

George Tarjan, M.D.

Professor of Psychiatry,

University of California, Los Angeles;

Secretary, The American Psychiatric Association.

James M. A. Weiss, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Missouri School of Medicine,

Columbia, Missouri.

George Winokur, M.D.

Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry,

State University of Iowa School of Medicine,

Iowa City, Iowa.

Service of the within and receipt of

thereof is hereby admitted this..................

of August, A .D . 1971.

a copy

.......day