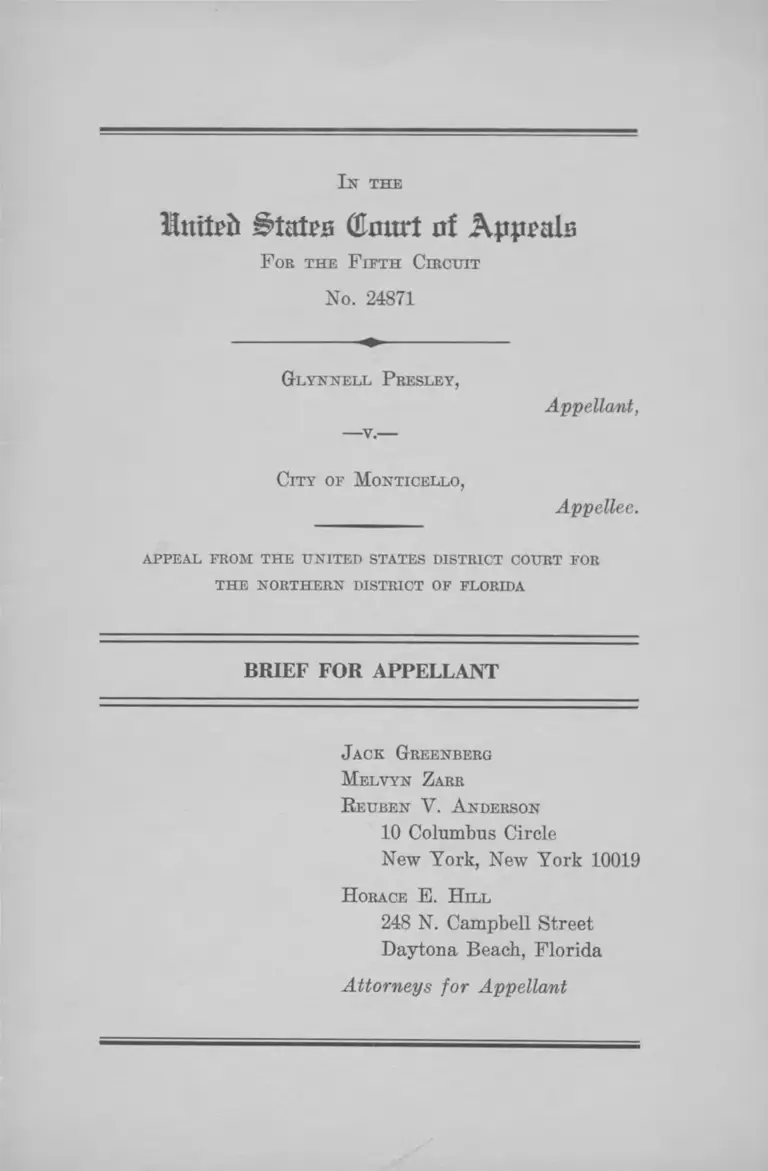

Presley v. City of Monticello Brief of Appellant

Public Court Documents

November 30, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Presley v. City of Monticello Brief of Appellant, 1967. df632c7b-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/eb3bb878-95b4-4e3e-b707-d9240dd5e459/presley-v-city-of-monticello-brief-of-appellant. Accessed March 01, 2026.

Copied!

Httttpit Btntta (Emtrt of Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 24871

In th e

G lyn n e ll P resley,

-v.-

Appellant,

City of M onticello,

Appellee.

appeal from th e united states district court for

THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Jack Greenberg

M elvyn Z arr

R euben V. A nderson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

H orace E. H ill

248 N. Campbell Street

Daytona Beach, Florida

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case............................. _........................ 1

Specifications of Error ................................................... 5

A rgument

Appellant’s Case Is Removable Pursuant to 28

U. S. C. §1443(1) and Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S.

780 (1966)..................................................................... 6

Conclusion .......................................................................................... 9

T able of Cases

City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U. S. 808 (1966) .... 5, 8

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966) ...................... 5, 6, 8

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306 ...................... 7

Wyche v. State of Louisiana, This Court, No. 24165 .... 8

F ederal Statutes

28 U. S. C. §1443(1) ........................................................... 5,6

42 U. S. C. §2000a............................................................. 6, 7

42 U. S. C. §2000a-2(c) ..................................................... 6

In th e

States Qlourt nf Appeals

F or th e F ifth Circuit

No. 24871

Glyn n e ll P resley,

Appellant,

—v.—

City of M onticello,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Florida, re

manding to the Municipal Court of the City of Monticello,

Florida a criminal prosecution punishing appellant’s at

tempt to secure full and equal enjoyment of the services,

facilities and privileges of a gasoline station in Monticello,

Florida.

Appellant, Glynnell Presley, is a Negro citizen of the

United States and of the State of Florida. He is employed

as a football and basketball coach at Richardson High

School in Lake City, Florida (R. 89). On September 24,

2

1966, while driving by car through the City of Monticello,

Florida, appellant stopped at Ed Bailey’s Gulf Service

Station to buy gas and to use the restroom facilities of

the station (R. 88).

While his automobile was being serviced, appellant asked

to use the restroom, and was directed to an unkempt facil

ity. Realizing that this restroom was reserved for Negroes

(R. 88, 107 )* appellant requested the attendant’s permis-

1 Although there was some testimony denying that the restrooms

were segregated, the record viewed as a whole leaves little room for

doubt.

The appellant testified concerning segregated facilities as follows

(R. 93-94):

Q. Are the facilities in that service station segregated? A .

Yes.

Q. In what manner, how can you tell? A . W ell, inasmuch as

this fellow before me, I have forgotten the model, but he car

ried 46-988 tag, was there in the station as I pulled in. He was

a white fellow and had just left the restroom, and the same

restroom I was denied permission to use was the restroom that

he had just left. I assumed I could use it but I was unable to

use it.

Q. He wouldn’t let you ? A . No, he said, “you can’t use it.”

That means that he wouldn’t let me use it.

Q. Did he say why? A . No, he just said, you are not al

lowed to use the restroom. And it is common knowledge in the

City of Monticello that this thing goes on. As a matter of

fact,—

Mr. B ird : I object Your Honor.

The Court: I will have to sustain the objection, counsel.

This is beyond the purview of this hearing.

Mr. Miles, a witness for the appellant, testified as follows (R.

107) :

Q. Did Mr. Presley want to use the bathroom facilities they

had there ? A . That’s right. They had one in the back which

was kept pretty dirty and things.

Q. Isn’t it a fact that they have segregated bathroom facili

ties there? A . Well, there is one, and the other one had

“Manager” or “Private” on it. And the mens had the same

thing on it too.

(footnote continued on next page)

3

sion to use the restrooms used by white patrons, which

were marked “ Manager” and “ Private” (R. 88, 93, 107).

The attendant denied appellant the use of the restroom

reserved for white males. Thereupon appellant told the

attendant that the gasoline would have to be removed from

his automobile if he could not use the restroom facilities

without racial discrimination (R. 88, 92). When the at

tendant informed appellant that he could neither let him

use the white restroom nor remove the gasoline, appellant

asked to see the owner (R. 89). The attendant then went

into the station and made a telephone call to the owner,

Mr. Ed Bailey (R. 89). Mr. Bailey arrived in about five

Q. And Negroes don’t go in the “Manager” or “Private”

one ? A . They go in the one on the back.

Q. But white people go in the “Manager’s” or the “Private”

one? A . That’s right.

Officer Thurmon testified as follows on cross-examination (R. 80-

8 1 ) :

Q. Is it not a fact, officer, that the bathroom facilities in that

station are segregated, the bathroom facilities for white and

colored ?

* * * # # #

A. W ell, I don’t know. I know they have different washrooms

there but how they manage it I don’t know.

Q. One marked for white and one marked for colored? A .

W ell, I don’t know if they are marked or not.

Q. W ell, one is used by colored and one is used by white,

isn’t it? A . I don’t know. I never looked. That is their busi

ness.

Q. W ell, that is the practice and custom and use of it, you

know that to be a fact, don’t you ?

# # * * *

A . W ell, I don’t know if they worked like that all the time I

have seen some go in different washrooms but whether it works

like that all the time I don’t know.

Officer Malloy testified under cross-examination as follows (R.

7 0 ) :

Q. A t that service station don’t they have segregated facili

ties, bath facilities ? A . No.

4

minutes and went directly to the appellant and told him

to pay for the gas (R. 90, 105). Appellant told Mr. Bailey

in a normal tone of voice that if he could not use the rest

room facilities at the station he wanted the gas removed

from his automobile (R. 90). At this point Mr. Bailey

grabbed the appellant by his collar and pushed him against

his car (R. 90, 106). The appellant held Mr. Bailey until

a man from across the street came and separated them

(R. 90, 105, 106). Appellant acted in a restrained and rea

sonable manner at all times (R. 108, 109).

Two city policemen of the City of Monticello and a

Deputy Sheriff of Jefferson County, Florida were parked

about 150 yards away from the service station when this

incident occurred (R. 54, 78). Upon being informed of the

trouble at the station, the two city policemen hurried to

the scene and immediately arrested the appellant on a

charge of disorderly conduct. Although the appellant did

not start the altercation and none of the officers saw what

happened, he was immediately arrested and taken to the

police station, locked up and charged with disorderly con

duct in violation of Section 1314, Code of Ordinance, City

of Monticello (R. 6-7). Appellant was released on a bond

of $50.00 and his trial was set for October 3, 1966 in the

City Court of Monticello, Florida.

On September 30, 1966 appellant filed in the United

States District Court in the Northern District of Florida

his verified petition for removal (R. 1, 5). The removal

petition alleged that his arrest and prosecution punished

him for the exercise of rights secured him by the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 to use without racial discrimination the

restroom facilities of the gas station.

5

On October 24, 1966 appellee’s motion to remand to the

Municipal Court of the City of Monticello, Florida was

filed (R. 6, 15). The motion challenged the sufficiency of

the allegations of the removal petition to establish grounds

for removal (R. 10).

On February 21, 1967 United States District Judge

G. Harrold Carswell held an evidentiary hearing (R. 42,

43). The court limited the hearing to “ testimony with

respect to the reasonableness of the arrest” of appellant

(R. 95, 115).

On February 23, 1967 Judge Carswell entered an order

remanding the case to the Municipal Court of the City of

Monticello, Florida on the ground “ that there was prob

able cause for the arrest of Presley at the time and place

on the charge made against him” (R. 22).

Judge Carswell’s remand order was entered February

23, 1967 (R. 21); timely application for extension of time

to file a notice of appeal was made March 6th (by tele

gram) and March 7th (by telephone). An extension was

granted to March 31, 1967 (R. 25) and appellant’s notice

of appeal was filed March 27, 1967 (R. 27).

Specifications of Error

(1) The Court below erred in remanding appellant’s

prosecution to the Municipal Court of the City of Monti

cello.

(2) The Court below erred in failing to apply to this

case the standard for removal announced in Georgia v.

Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966), and in remanding the case

without making the factual findings recpiired by Rachel.

6

A R G U M E N T

Appellant’s Case Is Removable Pursuant to 28 U. S. C.

§ 1 4 4 3 (1 ) and Georgin v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1 9 6 6 ).

Appellant’s case is one that falls within that class of

cases which the United States Supreme Court in Georgia

v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966), held properly removable

to federal court pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §1443(1). Appel

lant’s prosecution punishes him for attempting to secure

full and equal enjoyment, without racial discrimination,

of the services, facilities and privileges of Ed Bailey’s

Gulf Service Station, a place of public acconunodation as

defined by Section 201 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U. S. C. §2000a. Georgia v. Rachel, supra, established

that a person prosecuted for attempting to exercise rights

or privileges secured by Section 201 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. §2000a, was entitled to remove his

prosecution to federal court pursuant to Section 203(c),

42 U. S. C. §2000a-2(c)2 and 28 U. S. C. §1443(1).3 The

Court in Rachel, made clear that “ [t]he burden of having

to defend prosecutions is itself the denial of a right ex

plicitly conferred by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as con

2 §2000a-2(c) provides, in relevant part: “No person shall . . .

punish or attempt to punish any person for exercising or attempt

ing to exercise any right or privilege secured by Section 2000a or

2000a-l of this title.”

3 Section 1443(1) provides: “Any of the following civil actions

or criminal prosecutions, commenced in a State court may he re

moved by the defendant to the district court of the United States

for the district and division embracing the place wherein it is pend

ing : (1) Against any person who is denied or cannot enforce in the

courts of such State a right under any law providing for the equal

civil rights of citizens of the United States, or of all persons within

the jurisdiction thereof.”

7

strued in Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306” (384

U. S. at 805).

From the facts adduced at the hearing, there can be no

doubt that the conduct for which appellant is prosecuted

is protected by 42 U . S. C . §2000a(b)(2) and §2000a(c) (2).4

Appellant testified that his purpose for stopping at the

station was to buy gas and use the restroom facilities (R.

88). When appellant was denied the nondiscriminatory

use of the restroom facilities, he asked that the gas be

removed from his automobile (R. 88). This request was,

under the circumstances, a reasonable and orderly alterna

tive to supporting racial discrimination; he simply refused

to patronize an establishment which subjected him to seg

regated restroom facilities (R. 90, 105, 106). Appellant’s

protest was neither loud nor obnoxious (R. 92, 10S). The

altercation which resulted—not started by appellant (R.

90, 106)—was simply whether he could refuse to complete

a sale of gas premised upon his assumption that he would

not be subjected to racial discrimination.

The fact that appellant is charged with disorderly con

duct and not trespass does not defeat his right to removal.

The availability of removal does not depend upon the

State’s choice of charges; otherwise the state could defeat

4 §2000a(b) (2) provides that the following establishments are

covered by the A ct: “any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch

counter, soda fountain, or other facility principally engaged in sell

ing food for consumption on the premises, including, but not limited

to, any such facility located on the premises of any retail establish

ment ; or any gasoline station.”

§2000a(c) (2) provides that the operation of an establishment af

fects commerce within the meaning of this title if “ it serves or

otfers to serve interstate travelers or a substantial portion of the

food which it serves, or gasoline or other products which it sells, has

moved in commerce.”

It is beyond dispute that the gasoline in question moved in com

merce.

8

removal merely by charging the defendant with a crime

other than trespass.5

The Court below made no findings of fact as to the ex

istence of the segregated restroom facilities at the service

station, nor did it decide whether appellant’s arrest and

prosecution punished him for his attempted use of the

facilities -without racial discrimination. In failing to do so,

the Court below clearly failed to follow Rachel.6 Reversal

would be justified on this ground alone. However, since

the record makes clear that appellant’s prosecution pun

ishes him for attempting to use the restroom facilities

without racial discrimination, the district court should be

directed to dismiss the charge against appellant.

5 This was made clear in W yche v. State of Louisiana, this Court,

No. 24165, decided October 26, 1967 in which the Court held: “ It

is what the movant was actually doing with respect to the exercise

of his federally protected rights, as determined in a hearing for

remand, not the appellation which is attributed to his attempted

exercise of the rights by a state prosecutor that controls.”

6 The Court below merely stated that “there was probable cause

for the arrest” (R. 22) and based its remand order on City of

Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U. S. 808 (1966). Peacock is clearly

inapposite. In Peacock the United States Supreme Court dis

allowed federal civil rights removal jurisdiction because the defen

dants in that action had not alleged that their conduct was pro

tected by Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

9

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the order of the district

court remanding appellant’s case should he reversed,

with directions to the district court to dismiss appel

lant’s prosecution.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

M elvyn Z arr

R euben V . A nderson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

H orace E. H ill

248 N. Campbell Street

Daytona Beach, Florida

Attorneys for Appellant

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on th e.......day of November 1967,

I served a copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellant upon

T. Buckingham Bird, Esq., P. 0. Box 279, Monticello,

Florida, attorney for appellees, by United States air mail,

postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellant

recount

iorton s t r ic t